- 1School of Art and Design, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China

- 2Cognition and Human Behavior Key Laboratory of Hunan Province, Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

- 3School of Education, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

- 4School of Administrative Law, Northwest University of Political Science and Law, Xi'an, China

- 5Continuing Education College, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

This study examines the underlying mechanism that connects career social support with employability through a survey of 392 Chinese college students. The results showed that career social support had a positive effect on career adaptation and employability of college students, and career adaptation mediated the association between career social support and employability. Furthermore, proactive personality was found to play a moderating role in linking career adaptation and employability. More specifically, higher levels of a proactive personality strengthen the enhancing effect of career adaptation on the employability of college students. Therefore, there was a moderated mediation effect between career social support and employability of college students.

Introduction

The employment of college students is now a persistent hot topic in China. Since the expanded enrollment in 1999, the number of Chinese college graduates has increased sharply during recent years. According to a survey conducted by China’s Ministry of Education (Mycos Research Institute, 2019), the number of college graduates in China reached over 8.3 million in 2019, which was a historical high. The employment rate of college graduates was 91.5% in 2018, and it was lower than that in 2014 (92.6%), indicating that the employment rate in China was on a gentle, but steady, downward slide. Among the factors influencing successful employment, employers usually regard the candidates’ employability as a fundamental determinant of recruitment (Guilbert et al., 2016). Mcardle et al. (2007) propose that the lack of employability is the primary cause of employment difficulty for college students. Therefore, it is worthwhile to identify the influential factors that underpin undergraduates’ employability, which will be beneficial to improve the employability of college students and alleviate the social problems of unemployment.

Employability is conceptualized as a set of human capital, social capital, personal characteristics, and personal behaviors that makes graduates more likely to gain employment (Clarke, 2018). From the inputs point, employability associates with factors, such as competency, which increase the likelihood of getting and maintaining a job (De Cuyper et al., 2012). Yu et al. (2014) proposed that employability consisted of eight factors: interpersonal relationships, team cooperation, learning ability, resolving problems, social support, network difference, an optimistic and open personality, and career identification. The interpersonal relationships, team cooperation, learning ability, and resolving problems factors were competencies related to coping with interpersonal relationship and problem solving. Social support and network difference reflected the social capital, and an optimistic and open personality reflected positive personality characteristics.

Fugate et al. (2004) define employability as a person-centered, psycho-social construct, and propose that people with well-developed social and human capital often utilize formal (e.g., parents) and informal support systems (e.g., friend of a friend) to devote to the job search behaviors. According to Resource Conservation Theory (Hobfoll et al., 2003), individuals will always strive to maintain and utilize resources that contribute to their successful employment, and the more social psychological resources (e.g., support from parents and friends, and power) can result in a greater chance of their successful employment. As an important social network and capital resource, career social support may be highly influential in determining the success of college students’ employment.

Career social support is considered to be a significant and successful way into the labor market, and it also affects the resources available to individuals when considering, choosing and pursuing career choices (Chronister and Mcwhirter, 2004). Different to general social support, career social support is a domain-specific social support related to career-relevant tasks or issues. More specifically, it includes information and advice about career planning, financial support for job search behavior, comfort and encouragement after unsuccessful interviews, and other resources that individuals can obtain from their social networks such as parents, siblings, teachers, friends, and relatives (Hou et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2017). Numerous empirical findings have shown that social support has significant positive impacts on college students’ employability (Michailidis et al., 2017), career self-efficacy (Wang and Fu, 2015), career maturity (Cho and Choi, 2007), and career preparation (Hirschi et al., 2011).

According to Resource Conservation Theory, people with more resources are less likely to suffer from resource loss attacks. Instead, they are more likely to gain resources (Hobfoll, 2001). Career social support and employability are both important personal resources and, according to the Career Construction Theory (CCT), career adaptability is a social psychological resource to cope with working tasks (Savickas, 1997). Individuals with more career social support are likely to improve their career adaptability, and then career adaptability and proactivity, which are regarded as a self-regulating resource together, influence the individual’s employability. Therefore, this study comprehensively investigates how these factors affect the employability of college students in the Chinese context.

The Mediating Role of Career Adaptability

The term “Career adaptability” is considered a fundamental psychological resource enabling people to deal with present and anticipated tasks, transitions, and traumas in their occupational roles that change their social integration (Savickas, 1997), while concern, control, curiosity, and confidence constitute career adaptability resources (Savickas, 2005). Concern for the future enables individuals to think ahead and prepare for what might happen. Control enables a person to be more responsible for shaping themselves as well as the surroundings to meet future needs by adopting self-discipline and persistence. Curiosity facilitates a person to recognize themselves in different situations and roles. Confidence prompts the person to implement their life design (Savickas and Porfeli, 2012).

Considering the rapid change of the global market, it is important that people gain the competence to adapt to the requirements of career development and employment (Hou et al., 2012b). Career Construction Theory (Savickas, 2002) suggests that social support is an important contextual determinant of career adaptability. Previous research demonstrated a strong and consistent association between social support and career adaptability (Wang and Fu, 2015; Fawehinmi, 2016; Ghosh and Fouad, 2017). For example, in a sample of graduating seniors, Ghosh and Fouad (2017) indicated that social support can significantly predict the concern resource. In line with the statement of Ghosh and Fouad (2017), Wang and Fu (2015) recruited 879 Chinese college graduates as the sample and documented that career adaptability can be enhanced by social support.

According to Career Construction Theory, the adaption results are produced by adaptive readiness, adaptability resources, and adapting responses (Savickas and Porfeli, 2012). People who are willing (adaptive) and able (adaptability) to adjust behaviors according to changing conditions (adapting) were expected to have higher levels of adaptation (outcome). As a core component in career development, previous research suggested that career adaptability was a significant predictor for job satisfaction (Han and Rojewski, 2015), turnover intention (Chan and Mai, 2015), job performance (Ohme and Zacher, 2015), and employability (Mcardle et al., 2007; Dumulescu et al., 2015; Veld et al., 2016). Consequently, the first hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Career adaptability will play a mediating role between career social support and employability.

The Moderating Role of Proactive Personality

Recent research has called attention to the joint contribution of social psychological capital and individual attributes to employability (Van der Heijden and Spurk, 2019). According to Resource Conservation Theory, a proactive personality can not only alleviate the adverse effect of resource scarcity, but also gain favorable effects when resources are sufficient. Accordingly, we explored whether the mediating role of career adaptability was moderated by a proactive personality. Proactive personality is deemed as a tendency to take personal initiative in a wide spectrum of activities and situations (Crant, 2000). High initiative individuals tend to create conditions for themselves, take the initiative to obtain relevant professional support, formulate their career planning, and pursue career goals they have set (Bateman and Crant, 1993). Previous studies have shown that these proactive career behaviors are beneficial to enhance individuals’ employability (De Vos and Soens, 2008; Chughtai, 2019).

A proactive personality may reinforce the effect of career adaptability on employability. On the one hand, a proactive personality facilitates promotion of career adaptability and personal growth. Individuals with proactivity are likely to be future-oriented, pay more attention to their career concerns, and obtain high self-efficacy in the world of work (Seibert et al., 1999; Tolentino et al., 2014). On the other hand, during difficult situations, proactive individuals often employ goal management strategies rather than risk management strategies. For instance, proactive individuals will choose a constructive way for further employability enhancement, and they often seek proactive information about occupations and their requirements (Brown et al., 2006), and they tend to take concrete measures to search for employment, commit to skill development, and thus get a job (Mcardle et al., 2007). In addition, for the employees with a proactive personality, they are more likely to develop and maintain high-quality relationships with their superiors and strengthen their employability (Li et al., 2010). Consequently, the second hypothesis is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 2: A proactive personality will play a moderating role in the mediation effect of career adaptability between career social support and employability. Specifically, a proactive personality will moderate the second half path of the mediating link (i.e., the relationship between career adaptability and employability).

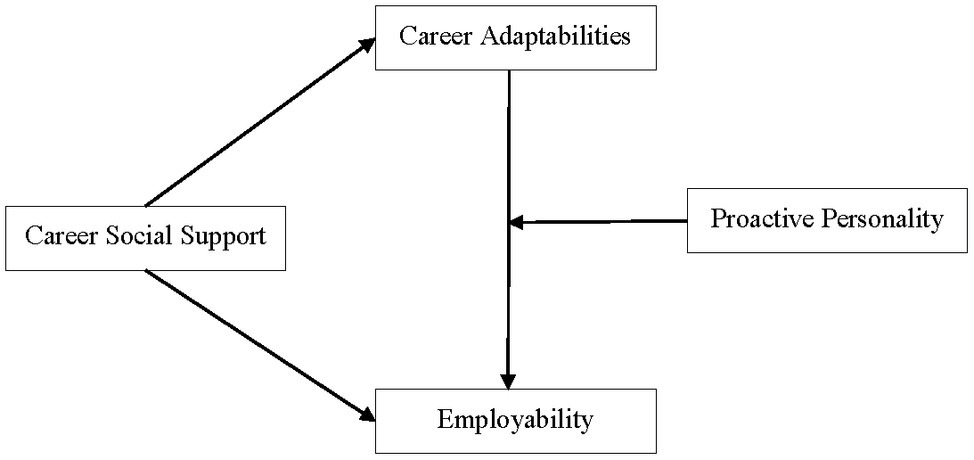

In brief, we established a moderated mediation model (see Figure 1), and the purpose of this paper was twofold: (1) to explore whether career adaptability mediated the relationship between career social support and employability; (2) to test whether a proactive personality moderated the mediation effect of career adaptability. The moderated mediation model not only replies to the question of how career social support affects employability, but also provides a response when the enhancing effect is stronger or weaker.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 392 college students (Mage = 21.12 years, SDage = 2.13, range = 19–24) recruited from two universities in China. Among the sample, 50.5% of these participants were sophomores, 40.6% were juniors, and 8.9% were seniors. Furthermore, 78.6% of these participants were female, 75.3% had one or more siblings, and 65.3% reported their place of residence as urban.

Measures

Career social support was measured using the Career Social Support Inventory (CSSI) for Chinese College Students designed by Hou et al. (2010). The CSSI is composed of five subscales, namely parents’ support, siblings’ support, teachers’ support, friends’ support, and relatives’ support. Each subscale consists of 20 items measuring the following four types of support: information support (seven items), advice support (six items), emotional support (four items), and material support (three items). Sample items include, “tell me some information about college life in advance” (information support), “provide me with some advice about future employment and development” (advice support), “care about how I feel” (emotional support), and “provide me with tuition” (material support). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very much). The psychometric characteristics of the CSSI have been assessed in previous studies (e.g., Hou et al., 2012a). In this study, Cronbach’ α was 0.96.

Career adaptability was measured by means of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS; Savickas and Porfeli, 2012), which assessed four dimensions including concern (e.g., “Preparing for the future”), control (e.g., “Taking responsibility for my actions”), curiosity (e.g., “Becoming curious about new opportunities”), and confidence (e.g., “Working up to my ability”). Each subscale consisted of six items, and all items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not strong”, 5 = “strongest”). The CAAS has been previously validated in Chinese samples (e.g., Hou et al., 2012b; Hui et al., 2018). In the present study, Cronbach’ α was 0.91.

Employability was assessed using the University Student’s Employability Questionnaire (USEQ; Yu et al., 2014). This measure consisted of 36 items assessing eight dimensions covering interpersonal relationships (five items; Sample item: “I like to get along with others”), team cooperation (three items; Sample item: “I am willing to share information resources with team members”), learning ability (four items; Sample item: “I always want to learn new knowledge”), resolving problems (five items; Sample item: “I am able to properly handle multiple complex tasks”), social support (four items; Sample item: “My relatives can provide resources for my job hunting and career development”), network difference (three items; Sample item: “The people I interact with have very different hobbies and specialties”), an optimistic and open personality (six items; Sample item: “I will not be discouraged by failure”), and career identification (six items; Sample item: “I have clear employment goals”). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The USEQ has shown good reliability and validity in previous research (e.g., Ye et al., 2017). In this study, Cronbach’ α was 0.90.

Proactive personality was assessed by the means of the Proactive Personality scale (Bateman and Crant, 1993), which consisted of 10 items. Respondents were asked to rate each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is “I often find new ways to improve my life”. The psychometric characteristics of this scale have been previously validated in Chinese samples (e.g., Kim et al., 2009). Cronbach’ α was 0.83 in the present study.

Data Analysis

First, descriptive statistics and correlations were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0. Second, we used the PROCESS macro (Model 4; Hayes, 2013) of SPSS software to examine the indirect effect of career adaptability in linking career social support and employability. The bias-corrected bootstrapping method based on 2000 samples was used to test the significance of the indirect effect.

Third, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using PROCESS (Model 14) to determine whether the indirect path was moderated by a proactive personality. Finally, we calculated conditional indirect effects so as to further test whether the indirect effect varied under the condition of different values of the moderating variable.

Results

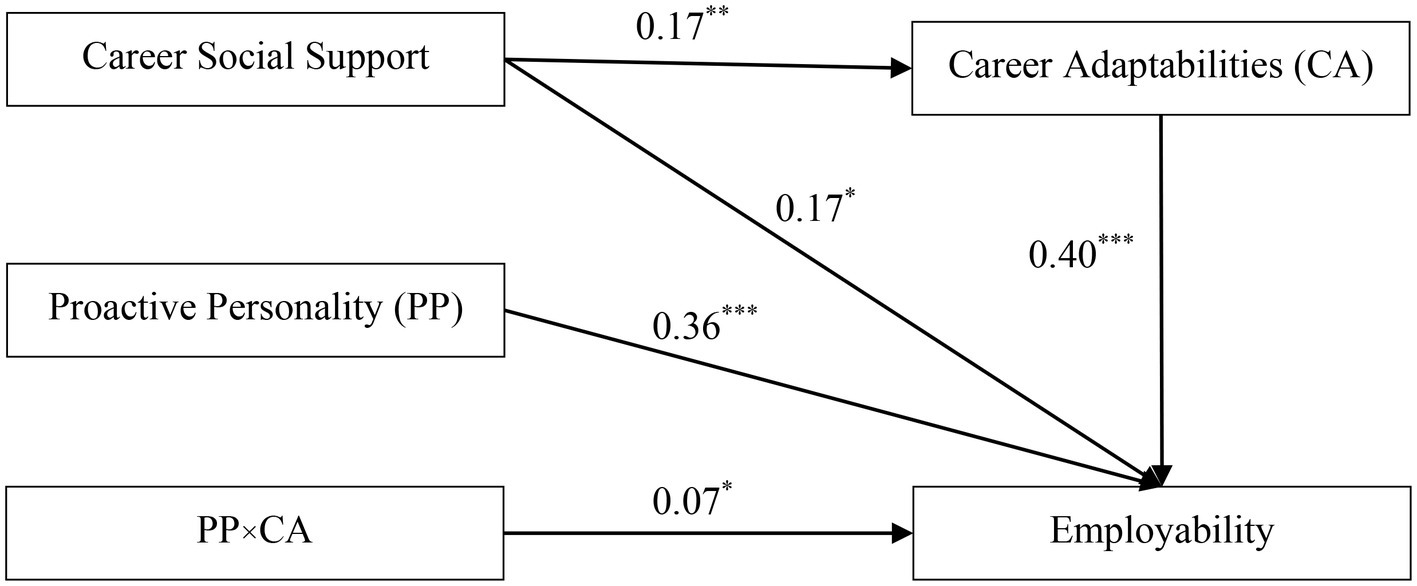

Descriptive Statistics

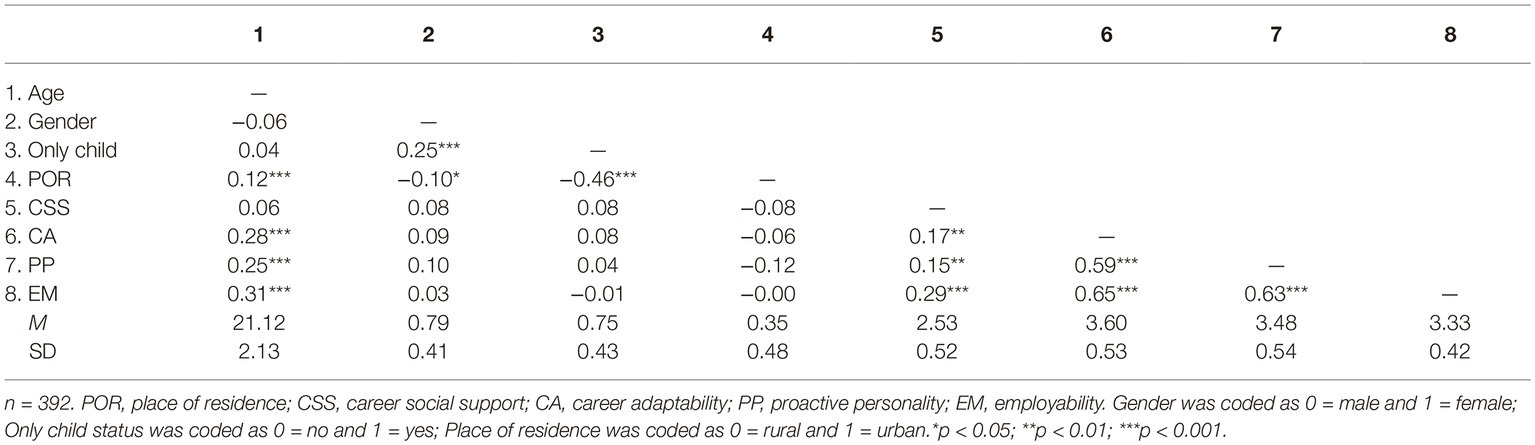

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and correlations for all study indicators. As expected, career social support, career adaptability, and employability were positively correlated with each other, and proactive personality showed a positive relation to employability. Moreover, age significantly correlated with proactive personality, career adaptability, and employability. To avoid possible spurious effects, age was included as a control variable in the models.

Testing for Mediation Effect

Next, we tested whether career adaptability mediated the relationship between career social support and employability. As seen in Figure 2, career social support significantly predicted employability [b = 0.29, SE = 0.05, 95%CI = (0.20, 0.39)] and career adaptability [b = 0.17, SE = 0.05, 95%CI = (0.07, 0.27)]. Furthermore, when career social support [b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = (0.11, 0.27)] and career adaptability [b = 0.61, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = (0.54, 0.69)] were entered as predictors, they both showed significant effects on employability. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method revealed significant indirect effect [indirect effect = 0.10, SE = 0.03, 95%CI = (0.04, 0.16)] and direct effect [direct effect = 0.19, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = (0.11, 0.27)]. The mediation effect accounted for 36.0% of the total effect. Thus, career adaptability played a partially mediating role in the relationship of career social support with employability, and both Hypotheses 1 and 2 were verified.

Figure 2. The mediating effect of career adaptability in the association between career social support and employability. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Testing for Moderated Mediation Effect

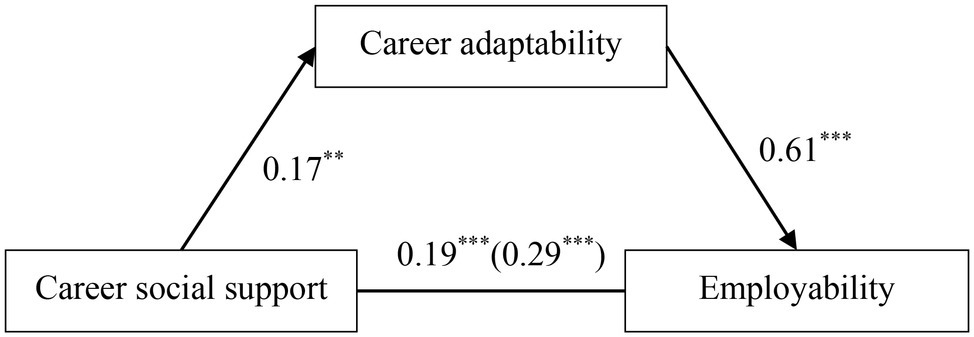

We examined whether a proactive personality moderated the mediating effect of career adaptability. Results from Figure 3 indicated that (1) career social support significantly predicted career adaptability [b = 0.17, SE = 0.05, 95%CI = (0.07, 0.27)], and (2) both career adaptability [b = 0.40, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = (0.32, 0.49)] and the interaction effect of career adaptability and a proactive personality [b = 0.07, SE = 0.03, 95%CI = (0.01, 0.13)] significantly affected employability. The findings suggested that the indirect effect between career social support and employability was moderated by a proactive personality. More specifically, a proactive personality moderated the second half path of the mediating effect. Thus, Hypotheses 3 was supported.

Figure 3. The moderating effect of proactive personality on the second stage of the indirect association. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

For clearly demonstrating the moderating role of proactive personality, this study conducted simple slope tests. The results revealed that higher career adaptability was strongly related to higher employability (bsimple = 0.47, t = 10.42, p < 0.001) under the condition of a high proactive personality (i.e., one SD above the mean). The relation between adaptability and employability was much weaker (bsimple = 0.33, t = 7.47, p < 0.001), however, in the condition of a low proactive personality (i.e., one SD below the mean).

Finally, the test of conditional indirect effects showed that the total indirect effect was more noteworthy for college students with high levels of a proactive personality [indirect effect = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95%CI = (0.03, 0.14)], than for those with low levels of proactive personality [indirect effect = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95%CI = (0.02, 0.10)]. Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015) was 0.011 [SE = 0.008, 95%CI = (0.001, 0.030)], indicating that proactive personality strengthened the mediating effect of career adaptability.

Discussion

With a steady increase in the number of university graduates, the employment of college students has become a common concern of higher education and even society as a whole in China. This study extended previous research by establishing a moderated mediation model, which systematically tested the synergistic impacts of individuals (i.e., career adaptability and proactive personality) and contextual (i.e., career social support) factors on college students’ employability.

First, in accordance with Resource Conservation Theory (Hobfoll et al., 2003) and previous empirical findings (European Training Foundation, 2002; Fabio and Kenny, 2015), the current study verified the positive function of career social support in cultivating college students’ employability. The Resource Conservation Theory emphasizes the links between individuals’ conditional resources (e.g., social support obtained from important others) and the chance of their successful employment (i.e., employability). Meanwhile, our results verify the view that the more powerful an individual’s social support network, the stronger his or her employability (Michailidis et al., 2017).

Second, this study identified that career adaptability mediated the association between career social support and employability, indicating that establishing a good social support system is conducive to the cultivation of career adaptability of college students (Creed et al., 2009), which in turn improves their employability (Koen et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2016). Thus, career adaptability could serve as a “bridge” linking career social support and employability, and career adaptability should be considered as a valuable psychosocial asset which may be fostered by providing diverse aspects of social support (e.g., information support, advice support, emotional support, and financial support).

Third, this study indicated that college students with high levels of a proactive personality were more likely to approach powerful employability. More importantly, we found that a proactive personality strengthened the salutary effect of career adaptability on employability. This implies that college students with higher proactivity may still take advantage of all the opportunities to actively seek employment information related to their career development, take the initiative to seize practical training, and further improve their employability, when they have stable career adaptability. Conversely, for those with lower proactivity, even if they have enough confidence in facing various challenges, they could not find and make use of beneficial opportunities in a timely manner. Thus, it is impossible to further identify what professional skills they need to improve, which in turn reduces the increase in employability (Fawehinmi, 2016).

The moderating role of proactive personality may be explained in two ways. First, Social Cognitive Theory suggests the individuals’ behavior depends on their self-efficacy, and high levels of proactivity is likely to enhance individuals’ career confidence and make them spend more energy on career exploration, and thus improve their employability (Cai et al., 2015). Second, Self-regulation Theory believes that individuals can adjust their views, emotions, and behaviors based on the outcomes of their action, and that individuals with high levels of proactivity are more likely to adjust their career concerns and control their career behavior based on the outcomes, and thus contribute to career success (Merino-Tejedor et al., 2016). These findings indicate that college students should improve their career adaptability and proactivity simultaneously so as to gain powerful employability.

Despite the importance of the findings, some limitations deserve to be mentioned. First of all, the study relied on a convenience sample of Chinese college students, and the mean age of the sample was only 21.12 years, which limited the generalizability of results. As such, further research should be designed to replicate the current study to samples consisting of other cultures and age groups. Second, the data we collected was at a single point in time. Long-term and continuous studies should be conducted to examine the causal links among career social support, career adaptability, and employability. Finally, the current study used college students self-report to collect data, and further studies would benefit from assessing the constructs using multiple informants.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, this research has several practical implications. To begin with, the present study corroborates the importance of career social support. Supports from family, teachers, and friends may help college students to gain more valuable employment information and financial assistance, which is beneficial for college students’ successful employment. Therefore, career social support should become a focus for future employability intervention plans. Besides the external support, college students should grow awareness of developing their own career adaptability persistently. On the other hand, this study offers preliminary evidence that a proactive personality enhances the significant influence of career adaptability on employability. Accordingly, we should not overlook the protective roles of personality trait resources (e.g., proactive personality).

In conclusion, this research deepens the understanding of how and when good career social support increases college students’ employability through considering individual (career adaptability and proactive personality) and contextual (career social support) variables simultaneously. Overall, good career social support can promote college students’ career adaptability, which in turn facilitates employability. Moreover, the beneficial role of career adaptability is strengthened by high levels of a proactive personality.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Hunan Normal University Research Ethnics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent.

Author Contributions

HG and YH designed the study. HG, QZ, and YC collected data, developed, and performed the statistical analysis in conjunction. TX and HG wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the National Social Science Foundation of China (18BYY089), the Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (16YJC190022), the Scientific Research Foundation of Hunan Provincial Education Department (19C1148), the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Henan Province (2018CJY036), the 13th Five-Year Plan for Science of Education Project in Henan Province ([2018]-JKGHYB-0191), Experience Design Integrated Innovation Research Team of Guangdong Province (2016WCXTD013), Social Science Research Base of Guangdong Province Center for Design Science and Art, the Philosophy and Social Sciences 13th Five-Year Planning Co-construction Project of Guangdong Province (GD16XYS16) and the 13th Five-Year Planning for Philosophy and Social Science of Guangzhou City (2018GZQN31).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bateman, T. S., and Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: a measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 14, 103–118. doi: 10.1002/job.4030140202

Brown, D. J., Cober, R. T., Kane, K., Levy, P. E., and Shalhoop, J. (2006). Proactive personality and the successful job search: a field investigation with college graduates. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 717–726. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.717

Cai, Z., Guan, Y., Li, H., Shi, W., Guo, K., Liu, Y., et al. (2015). Self-esteem and proactive personality as predictors of future work self and career adaptability: an examination of mediating and moderating processes. J. Vocat. Behav. 86, 86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.004

Chan, S. H. J., and Mai, X. (2015). The relation of career adaptability to satisfaction and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 89, 130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.05.005

Cho, M.-S., and Choi, K.-S. (2007). A model testing on ego-identity, social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, career maturity, and career preparation behavior in late adolescence. Korea J. Couns. 8, 1085–1099. doi: 10.15703/kjc.8.3.200709.1085

Chronister, K. M., and Mcwhirter, E. H. (2004). Ethnic differences in career supports and barriers for battered women: a pilot study. J. Career Assess. 12, 169–187. doi: 10.1177/1069072703257754

Chughtai, A. (2019). Servant leadership and perceived employability: proactive career behaviours as mediators. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 40, 213–229. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0281

Clarke, M. (2018). Rethinking graduate employability: the role of capital, individual attributes and context. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 1923–1937. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152

Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 26, 435–462. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00044-1

Creed, P. A., Fallon, T., and Hood, M. (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. J. Vocat. Behav. 74, 219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.004

De Cuyper, N., Raeder, S., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., and Wittekind, A. (2012). The association between workers' employability and burnout in a reorganization context: longitudinal evidence building upon the conservation of resources theory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 17, 162–174. doi: 10.1037/a0027348

De Vos, A., and Soens, N. (2008). Protean attitude and career success: the mediating role of self-management. J. Vocat. Behav. 73, 449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.08.007

Dumulescu, D., Balazsi, R., and Opre, A. (2015). Calling and career competencies among Romanian students: the mediating role of career adaptability. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 209, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.223

European Training Foundation (2002). Supporting the unemployed and job-seekers in Kosovo: Enhancing employability: A strategy for vocational training. Turin: European Training Foundation.

Fabio, A. D., and Kenny, M. E. (2015). The contributions of emotional intelligence and social support for adaptive career progress among Italian youth. J. Career Dev. 42, 48–59. doi: 10.1177/0894845314533420

Fawehinmi, O. O. (2016). The relationship between self-esteem, proactive personality and social support on career adaptability among undergraduate students. Masters thesis. Universiti Utara Malaysia.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., and Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: a psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

Ghosh, A., and Fouad, N. A. (2017). Career adaptability and social support among graduating college seniors. Career Dev. Q. 65, 278–283. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12098

Guilbert, L., Bernaud, J. L., Gouvernet, B., and Rossier, J. (2016). Employability: review and research prospects. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 16, 69–89. doi: 10.1007/s10775-015-9288-4

Han, H., and Rojewski, J. W. (2015). Gender-specific models of work-bound Korean adolescents’ social supports and career adaptability on subsequent job satisfaction. J. Career Dev. 42, 149–164. doi: 10.1177/0894845314545786

Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 50, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Hirschi, A., Niles, S. G., and Akos, P. (2011). Engagement in adolescent career preparation: social support, personality and the development of choice decidedness and congruence. J. Adolesc. 34, 173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.009

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., and Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 632–643. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632

Hou, Z. J., Bai, R., and Yao, Y. Y. (2010). Development of career social support inventory for Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 18, 439–442. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.019

Hou, Z. J., Chen, S. F., Zhou, S. L., and Li, X. (2012a). Development of parental career expectations scale for college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 20, 593–596. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2012.05.002

Hou, Z. J., Leung, S. A., Li, X., Li, X., and Xu, H. (2012b). Career adaptabilities scale—China form: construction and initial validation. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.006

Hui, T., Yuen, M., and Chen, G. (2018). Career adaptability, self-esteem, and social support among Hong Kong university students. Career Dev. Q. 66, 94–106. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12118

Jiang, Z., Wang, Z., Jing, X., Wallace, R., Jiang, X., and Kim, D. S. (2017). Core self-evaluation: linking career social support to life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 112, 128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.070

Kang, H., Jung, J., and Lee, J. (2016). The effects of career adaptability on job search efficacy and a quality of employment among hospitality and tourism management college senior students. Tourism Manage. Res. Org. 20, 17–42. doi: 10.18604/tmro.2016.20.4.2

Kim, T. Y., Hon, A. H. Y., and Crant, J. M. (2009). Proactive personality, employee creativity, and newcomer outcomes: a longitudinal study. J. Bus. Psychol. 24, 93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9094-4

Koen, J., Klehe, U. C., and Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2012). Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. J. Vocat. Behav. 81, 395–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.10.003

Li, N., Liang, J., and Crant, J. M. (2010). The role of proactive personality in job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: a relational perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 95, 395–404. doi: 10.1037/a0018079

Mcardle, S., Waters, L., Briscoe, J. P., and Hall, D. T. (2007). Employability during unemployment: adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. J. Vocat. Behav. 71, 247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.003

Merino-Tejedor, E., Hontangas, P. M., and Boada-Grau, J. (2016). Career adaptability and its relation to self-regulation, career construction, and academic engagement among Spanish university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 93, 92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.01.005

Michailidis, M. P., Gantzias, G. K., and Michailidis, E. (2017). Unemployed: training and development, employability and social support. Int. J. Sustainable Agric. Manage. Inf. 1, 247–258. doi: 10.1504/IJSAMI.2015.074611

Mycos Research Institute (2019). Chinese 4-year college graduates’ employment annual report (2019). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Ohme, M., and Zacher, H. (2015). Job performance ratings: the relative importance of mental ability, conscientiousness, and career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 87, 161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.01.003

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: an integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Dev. Q. 45, 247–259. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

Savickas, M. L. (2002). “Career construction: a developmental theory of vocational behavior” in Career choice and development. 4th Edn. eds. D. BrownAssociates (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 149–205.

Savickas, M. L. (2005). “Career construction theory and practice” in Career development and counselling: Putting theory and research into work. 2nd Edn. eds. R. W. Lent and S. D. Brown (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 42–70.

Savickas, M. L., and Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., and Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 416–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416

Tolentino, L. R., Garcia, P. R. J. M., Lu, V. N., Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., and Plewa, C. (2014). Career adaptation: the relation of adaptability to goal orientation, proactive personality, and career optimism. J. Vocat. Behav. 84, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.11.004

Van der Heijden, B., and Spurk, D. (2019). Moderating role of LMX and proactive coping in the relationship between learning value of the job and employability enhancement among academic staff employees. Career Dev. Int. 24, 163–186. doi: 10.1108/CDI-09-2018-0246

Veld, M., Semeijn, J. H., and van Vuuren, T. (2016). Career control, career dialogue and managerial position: how do these matter for perceived employability? Career Dev. Int. 21, 697–712. doi: 10.1108/CDI-04-2016-0047

Wang, Z., and Fu, Y. (2015). Social support, social comparison, and career adaptability: a moderated mediation model. Soc. Behav. Pers. 43, 649–660. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.4.649

Ye, B. J., Zheng, Q., Dong, S. H., Fang, X. T., and Liu, L. L. (2017). The effect of calling on employability of college students: the mediating role of job searching clarity and job searching self-efficacy. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 33, 37–44. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.01.05

Keywords: career social support, career adaptation, proactive personality, moderated mediation, employability

Citation: Xia T, Gu H, Huang Y, Zhu Q and Cheng Y (2020) The Relationship Between Career Social Support and Employability of College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 11:28. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00028

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Tomika W. Greer, University of Houston, United StatesMelinde Coetzee, University of South Africa, South Africa

Copyright © 2020 Xia, Gu, Huang, Zhu and Cheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Honglei Gu, R0hMQGh1bm51LmVkdS5jbg==

Tiansheng Xia

Tiansheng Xia Honglei Gu

Honglei Gu Yamei Huang3

Yamei Huang3