94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 31 May 2019

Sec. Movement Science

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01294

In recent years, extreme sport-related pursuits including climbing have emerged not only as recreational activities but as competitive sports. Today, sport climbing is a rapidly developing, competitive sport included in the 2020 Olympic Games official program. Given recent developments, the understanding of which factors may influence actual climbing performance becomes critical. The present study aimed at identifying key performance parameters as perceived by experts in predicting actual lead sport climbing performance. Ten male (Mage = 28, SD = 6.6 years) expert climbers (7a+ to 8b on-sight French Rating Scale of Difficulty), who were also registered as climbing coaches, participated in semi-structured interviews. Participants’ responses were subjected to inductive-deductive content analysis. Several performance parameters were identified: passing cruxes, strength and conditioning aspects, interaction with the environment, possessing a good climbing movement repertoire, risk management, route management, mental balance, peer communication, and route preview. Route previewing emerged as critical when it comes to preparing and planning ascents, both cognitively and physically. That is, when optimizing decision making in relation to progressing on the route (ascent strategy forecasting) and when enhancing strategic management in relation to the effort exerted on the route (ascent effort forecasting). Participants described how such planning for the ascent allows them to: select an accurate and comprehensive movement repertoire relative to the specific demands of the route and reject ineffective movements; optimize effective movements; and link different movements upward. As the sport of climbing continues to develop, our findings provide a basis for further research that shall examine further how, each of these performance parameters identified, can most effectively be enhanced and optimized to influence performance positively. In addition, the present study provides a comprehensive view of parameters to consider when planning, designing and delivering holistic and coherent training programs aimed at enhancing climbing performance.

In recent years, extreme sport-related pursuits such as climbing not only have emerged as recreational activities but have evolved into competitive mainstream sporting disciplines (Mittelstaedt, 1997; Hoibian, 2017). Next to growing practice of sport climbing as a leisure activity, competition environments and practices have been developing internationally since the first World Championships held in Germany in 1991. Today, the sport of climbing is a discipline included in the 2020 Olympic Games official program in Tokyo, and it is proposed for inclusion in the 2024 Olympic Games official program in Paris. Despite the systematic and intensified training of athletes, the identification and understanding of key factors that may influence actual sport climbing performance is warranted. Therefore, the present study aimed at identifying key performance parameters as perceived by experts in predicting actual lead sport climbing performance.

Sport climbing takes place indoors as well as outdoors, and utilizes a belayed dynamic rope, which is attached to the climber. The belayed rope is connected to pre-fixed anchor points during the ascent by the climber and the system acts to protect the climber in the event of a fall. From a sporting point of view (see Stiehl and Ramsey, 2005), climbing is unique because of the different vertical practice environments. Climbers are routinely required to ascend and/or descend and/or traverse a given surface to complete the route. Sport lead climbing in particular may be performed indoor or outdoor; indoor on an artificial surface using artificial holds and outdoor on a variety of natural rock types and surfaces. The range of different types of climbing behavior that exist and the number of permutations of such behaviors makes categorizing individual climbing activity challenging [see taxonomy and further discussion in Jones and Johnson (2016)].

The emergence of climbing as a competitive discipline has generated research interest. Studies have mainly examined motivational and risk-taking profiles (e.g., Martha et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2017), physiological aspects (e.g., Espanña-Romero et al., 2012), biomechanical properties (e.g., Vigouroux et al., 2011), and injuries (e.g., Jones et al., 2018). Notwithstanding previous work, researchers frequently discuss that variables of a psychological nature such as problem-solving ability, movement sequence recall, route finding skills, anxiety levels and stress management may be better predictors of optimal physical climbing performance than physiological or biomechanical variables (e.g., Sheel, 2004; Watts, 2004; Giles et al., 2006; MacLeod et al., 2007; Morrison and Schöffl, 2007; Jones and Sanchez, 2017).

However, psychology-based research has rather utilized climbing, typically, as a task to fulfill its experimental designs and reach its research goals by adapting climbing rules and adjusting climbing routes (e.g., Smyth and Waller, 1998; Boschker et al., 2002; Pijpers et al., 2005). In sport climbing in general and in climbing competition in particular most of these modifications, if not all, are not permitted. In addition, whilst previous studies within other areas of sport sciences had recruited elite/expert climbers as well as novices, most psychology-based research had basically recruited inexperienced/novice participants only. The main objective of the present study was to identify sport climbing performance predictors so that future research can, ultimately, influence both practice and performance.

In the sport of climbing, the consequence of a fall whilst leading is complex and largely determined by the ability of the belayer to arrest the fall, the length of fall, non-failure of the protective equipment and whether impact is made with the climbing surface during or at the termination of the fall. Climbers may elect to pre-practice a route prior to leading. Pre-practice allows climbers to rehearse movement sequences, evaluate potential risks and the likelihood of success in relative safety. It is common for individuals preparing to lead outdoor routes of the highest standards to pre-practice the ascent thereby increasing the chance of success and reduce the chance of failure due to a fall. Ascending a climbing route without conducting pre-practice is considered in the arena to be the personification of climbing performance. Critically, physical pre-practice is not permitted in competition – performances are what are labeled as “on-sight” – but a standardized time to visually preview the route prior to ascent by participants is allowed (i.e., route previewing). Little research has examined the psychological requirements of rock climbing although they are thought to be “a key element in accomplished climbers” (Morrison and Schöffl, 2007, p. 852).

Route previewing is one of such variables suggested by sport scientists as a determinant to successful climbing performance (e.g., MacLeod et al., 2007; Sanchez et al., 2012; Seifert et al., 2017). In the same line, sport psychology researchers have suggested that route previewing mistakes are “a major reason for falling during climbing” (Boschker et al., 2002, p. 25) and elite climbing competitors have reported that a lack of climbing route knowledge is a handicap prior to performing in competition (Ferrand et al., 2006). In climbing, when performing on-sight, mistakes are not allowed: falling off the wall is not only the end of that given ascent; it also means for the climber that the given route will have never been performed on-sight, ever. Therefore, a second objective of the present study was to describe the role and function of route previewing, understood as the pre-ascent visual inspection of the climbing route, which past research had suggested as a climbing-specific, psychological-in-nature variable for successful performance (Ferrand et al., 2006; MacLeod et al., 2007; Sanchez et al., 2012; Seifert et al., 2017).

Given the current limited understanding of the factors that influence climbing performance, in the present study we adopted Bishop’s (2008) first stage of his sport sciences applied research model for sport sciences (ARMSS). Precisely, ARMSS is a three-phase, eight-stage model, originally proposed for injury prevention and health research (Finch, 2006; Sussman et al., 2006), which provides a framework of particular interest to such new sporting disciplines for which performance predictors are still to be identified. These three phases evolve from description to experimentation and implementation with the following different stages being proposed within (see Bishop, 2008, for full details). Bishop’s (2008) ARMSS first stage highlights the need for discussion with athletes and coaches to gain a thorough understanding of the sport and its performance-related issues before proceeding to the following stages of the model. Therefore, we applied a qualitative analytic approach (Patton, 2002) to gain a comprehensive understanding of the key performance parameters as perceived by experts in predicting actual sport lead-climbing performance.

A purposive sample was adopted (Berg, 2001; Patton, 2002) to represent expert climbers with coaching climbing badges; inclusion criteria included (a) domain-specific indicators of personal climbing performance and (b) officially regulated awards that indicated coaching education in sport climbing. On the one side, interviewees were required to possess an advanced to elite current climbing ability level superior to an on-sight 7a French Rating Scale of Difficulty [F-RSD; see Draper et al. (2016) for comparative amongst climbing rating systems]. Current ability rather than climbing experience was gathered as a measure of expertise since an individual’s climbing standard can vary throughout a single year. Research has categorized climbers possessing an ability superior to 7a F-RSD as advanced performers (Draper et al., 2016), as individuals require excellent skills, strength and time commitment to maintain such a standard ability level (Cox and Fulsaas, 2003). On the other side, interviewees were also required to hold, at least, a national officially recognized coaching qualification in sport climbing. Given the purpose of the study, it was deemed significant to interview climbers who, in addition to being experts in the practice of climbing would also possess an officially recognized education in teaching and coaching climbing, and thus who would be used to provide feedback, incorporate prompts, correct and reinstruct, use questioning and clarifying, and engage in instruction (Douge and Hastie, 1993).

The final sample interviewed in the present study comprised 10 male climbers (Mage = 28, SD = 6.6 years, range 21–40) with an on-sight climbing ability ranging from 7a+ to 8b F-RSD (advanced to elite) and a climbing experience ranging from 8 to 22 years of practice (Mexp = 14, SD = 6.2 years). In addition, four participants were in possession of the Royal Belgian Alpinism Federation (Royale Club Alpin Belge) qualification whereas the other six possessed the Belgian Physical Education and Sport (ADministration de l’Education Physique et du Sport) qualification. Amongst the ten participants, six also held a Higher Education taught degree in physical education. Participants practiced in a wide range of other sports including ice-climbing, sky-diving, paragliding, swimming, gymnastics, and cycling.

Two psychologists were first involved in the construction of the semi-structured interview guide. The open-ended questions were generated based on existing climbing-specific literature (Deweze and Le Menestrel, 1987; Salomon and Vigier, 1989; Glowacz and Pohl, 1992; Lemare and Morrot, 1995; Sheel, 2004; Watts, 2004; Giles et al., 2006). As per previous research (e.g., Holt and Morley, 2004; Wolfenden and Holt, 2005), the main topics of the interview guide were predetermined (deductive process) but the different questions were open-ended to elicit a range of responses pertinent to, and generated by, each participant (inductive process).

Pilot interviews were conducted with two participants matching the pre-established study participation criteria. These two climber-coaches were interviewed individually and were not included in the final sample. A second researcher, who acted as a passive observer, was present during the interviews. After each pilot interview, the two researchers and the interviewee discussed the interview with a view to (a) enhance interviewing procedures and interviewer skills and (b) refine the phraseology and technical jargon employed by the interviewer.

The final interview guide consisted of four main sections. The first section gathered general demographic information such as age, occupation, educational and coaching backgrounds, and sports practice. Also, specific sport climbing information such as reasons, frequency and types of practice were gathered. In the second and third sections, questions revolved specifically around the participants’ experience of “on-sight” (section “The Interview Guide”) and “pre-practiced” (section “The Interview Guide”) climbing modalities in lead sport climbing. An “on-sight” ascent is characterized by time-constraint visual examination of the route before climbing without previous physical rehearsal, and then ascent without a single fall. One may attempt an on-sight climb and fail the challenge. Subsequent successful attempts on that same route are considered “pre-practiced” ascents (a climb on a physically pre-rehearsed route). Examples of questions in these two sections were: “what do you do to prepare for an on-sight/pre-practiced climb and how do you do it?”; “what do you focus on when climbing on-sight/pre-practiced?”; “do you train with a view to climb on-sight/pre-practiced?”; “how do you prepare/work for particularly difficult parts of the route (e.g., cruxes)?” Discussion with the participants in these sections revolved around the factors that they believed influence climbing performance. The last section of the interview guide (section 4) focused particularly on route previewing in sport climbing. Participants were first asked to define, in their own words, the concept of “route preview/previewing” and then were asked to discuss its role and functions, both when climbing on-sight and pre-practiced. The complete interview guide is available from the corresponding author.

Climbers were individually approached at five different indoor climbing facilities across the French-speaking part of Belgium and invited to take part in this qualitative study investigating climbing performance. Note that contact with these facilities was regular during a period of time within the scope of a wider project that examined psychological aspects of sport climbing in a series of different studies (Sanchez and Dauby, 2009; Sanchez et al., 2010, 2012). All participants received written and verbal information about the study and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Confidentiality was assured by giving each interviewee a participant number, which was used as the only identification code (e.g., P1). The investigators ensured that the participants understood the overall purpose of the present qualitative study.

The interviews were carried out by the first investigator, who had both experience working with international elite athletes and coaches as a psychologist, and had experience of indoor sport climbing. All these aspects facilitated communication with the participants during the meetings and ensured rigor from the investigator during the course of the research. All interviews were conducted face-to-face, individually, either in a meeting room at the participant’s climbing club or in a laboratory at the interviewer’s university. All interviews were recorded using a dictaphone and their duration ranged from 65 to 110 min.

Each interview began by reminding the participants the nature and purpose of the study. Then, the different sections of the interview guide were followed in the pre-established order. Although the same questions were asked to all participants in a similar manner, the order of the questions within each section was allowed to vary according to the flow of the interaction between the interviewer and the interviewee. The interviewer allowed the participants to express themselves freely, to enhance the richness of the information (Patton, 2002).

In addition, consistent with the semi-structured interview format and use of open-ended questions (Patton, 2002), probes were asked throughout the interview, “to elicit more information about whatever the respondent has already said in response to a question” (Berg, 2001, p. 76). This encouraged the climbers to expand on their answers (elaboration) and allowed a more thorough understanding of their responses (clarification) (Rubin and Rubin, 2005). This knowledge elicitation took place using Spradley’s (1979) three types of questions for interviewing: (1) “descriptive questions” to identify precisely what was being discussed (e.g., “Can you describe what you do to prepare yourself for an on-sight climb? Can you tell me which are, in your opinion, the key aspects for success when climbing pre-practiced?”); (2) “structural questions” to obtain as much information as possible about the different aspects mentioned (e.g., “You mentioned that resting points and cruxes are crucial parts of a route. Why are they so important? What do you do to find them? What do you do to optimally face/utilize them?”); and (3) “contrast questions” to clarify and distinguish what the informant meant by the various terms and situations used (e.g., “Which are the differences between climbing a route on-sight or pre-practiced? Does it change to face a crux at the beginning of the route compared to facing it at the end of that route?”). These data collection procedures were adopted to elicit relevant knowledge from the sample interviewed. The same approach was used for each interview.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, yielding 130 pages of single-spaced typed text. All participants were given the opportunity to check their own interview transcript for content accuracy and validity. Most participants (6 out of 10) checked and returned their interview transcript; no significant changes to the transcripts were noted. The transcriptions of the interviews, which were defined as a hermeneutic unit, were content analyzed using ATLAS/ti qualitative data analysis software package (Muhr, 1997). ATLAS/ti is a flexible tool for constructing networks, particularly suited for approaches of theory building (see Kelle, 1995 for an overview on qualitative methodology and computer software).

A hierarchical content analysis was carried out by the first and second authors on the textual information to classify and reduce the data to more relevant and manageable units (Sparkes and Smith, 2014). The analysis of the transcripts, which departed from raw data, kept as a reference the interview guide and alternated an inductive category development -bottom-up or data-driven- with a deductive category application -top-down or theory-driven (Patton, 2002). Inter-rater reliability amongst two first authors aimed at ensuring that all units of meaning, themes and categories emerging from the information provided by the climbers were appropriately created, grouped and categorized (Sparkes and Smith, 2014). Member checking took place for trustworthiness (Smith and McGannon, 2018); findings were verified by the participants who agreed to do so (n = 6) once analysis procedures were finalized.

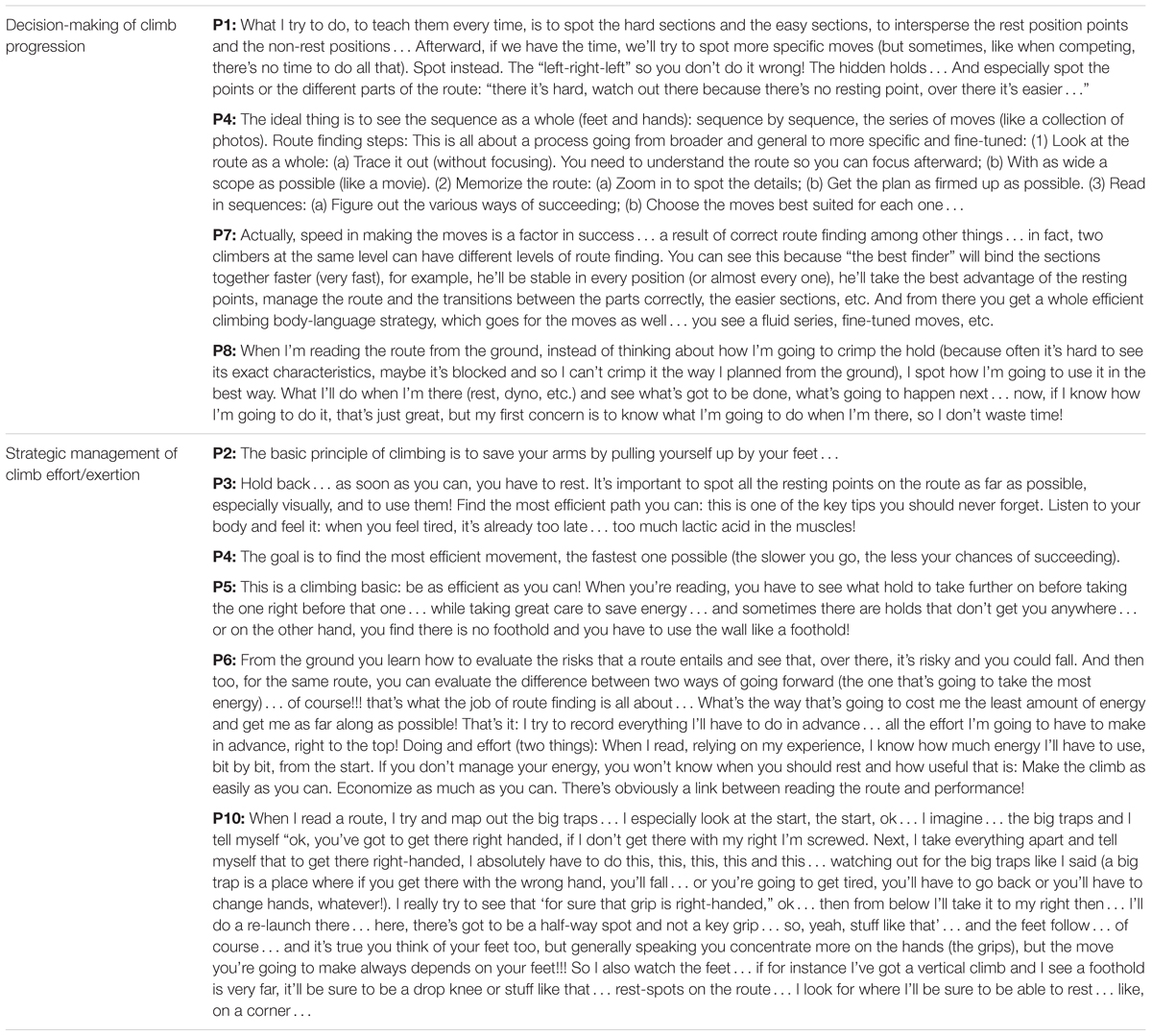

From the content analysis, several performance parameters perceived by the climbers as most influential emerged: passing cruxes, strength and conditioning aspects, interaction with the environment, possessing a good climbing movement repertoire, risk management, route management, mental balance, peer communication, and route preview. Route previewing emerged as critical when it comes to preparing and planning ascents, both cognitively and physically. That is, when optimizing decision making in relation to progressing on the route (ascent strategy forecasting) and when enhancing strategic management in relation to the effort exerted on the route (ascent effort forecasting). Table 1 provides their frequencies, per participant and overall. A sample of participants’ quotes for each climbing performance predictor is provided in Table 2.

Moreover, participants described how such planning for the ascent allows them to: select an accurate and comprehensive movement repertoire relative to the specific demands of the route and reject ineffective movements; optimize effective movements; and link different movements upward. Our sample of expert and advanced climbers believed that these two aspects, that is path strategy planning (ascent strategy forecasting) and ascent effort management were inter-related (see Figure 1).

More precisely, route previewing would help climbers to acquire an accurate and comprehensive movement repertoire, to eliminate ineffective movements and optimize the effective ones, and to determine how to link these movements upward, over the entire route. Our sample considered route finding necessary for both the mental preparation of a route never climbed before (on-sight performance, competition) and the actual practice of cruxes in training sessions (training, learning). Climbers noted that performance outputs were, ultimately, determined by both the factors contributing to the climber’s profile (e.g., anthropometric characteristics) and the route itself (e.g., traverse, overhanging). Table 3 provides their frequencies, per participant and overall. A sample of participants’ quotes for the perceived role and functions of route previewing is provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Participants’ quotes sample for the perceived role and function of route previewing in sport climbing performance.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first qualitative investigation of performance parameters as perceived by experts in predicting lead sport climbing performance. Precisely, the primary aim of the present study was to identify sport climbing performance predictors perceived as most influential in lead sport climbing and, secondly, to describe the role and function of route previewing in climbing performance. Our analysis revealed a wide-range of psychological, physiological, biomechanical and sociological climbing performance parameters that include passing cruxes, strength and conditioning aspects, interaction with the environment, possessing a good climbing movement repertoire, risk management (referring mainly to the risk of failing rather than the risk of injury), route management, mental balance, peer communication, and route preview. Route previewing emerged as the critical parameter that influenced cognitive and physical preparedness prior to ascent.

Participants in our study emphasized that performance output and success were, ultimately, determined by the interaction between different parameters that contributed to the configuration of the profile of the climber, ranging from individual such as anthropometrics profiles (Watts et al., 2003) to more external such as characteristics of the route (de Geus et al., 2006). Most technical decisions made by climbers on high grade climbing routes are automatically processed. Possessing a good climbing repertoire developed through training and “stress-tested” on increasingly more difficult standards of climbing routes would appear fundamental. Inherent in gaining a sound climbing repertoire would be the development of a high level of strength and conditioning.

In addition to the parameters more common to most competitive sporting disciplines in general, such as mental balance and risk management, participants in our study highlighted other more climbing-specific parameters such as peer communication and those related to route previewing (see further discussion below for the latter). Indeed, our participants reported that peer communication influenced climbers’ behaviors; it is still very common to see competitors route previewing together, and trying to find the best solutions to reach the top of a given route together despite being, actually, opponents. This, whilst today is considered to be a healthy form of rivalry, may well disappear in future once climbing reaches the standard competitive level more common to other more traditional competitive environments.

When it comes to route previewing, the views of the sample interviewed were that even if climbers were of equal biological (e.g., height) and physical capabilities (e.g., strength), route preview would make the difference between succeeding and failing on an ascent. Elite climbers are lean, muscular and likely able to climbing routes of a comparable standard. Therefore, given they are similar in that respect, route preview is likely the key parameter. Our participants declared that route preview allows individuals to mentally rehearse expected movement sequences in advance, identify and plan for crux sections thereby preserving energy and reducing the risk of non-completion due to a fall. Thus, route preview would allow the individual to reciprocally process the demands of the climbing route in regard of the key parameters highlighted to accurately appraise the challenges faced, and plan the best course of action required.

There is limited research on the role of psychological processing of climbing route information on climbing performance. Despite authorship teams suggesting that the ability to correctly visualize and interpret climbing route information prior to an ascent as an essential climbing skill (Boschker et al., 2002; MacLeod et al., 2007), and elite climbing competitors reporting a lack of climbing route knowledge as a handicap prior to performing in competition (Ferrand et al., 2006), the efficacy of route preview had not been tested experimentally until Sanchez et al. (2012). When examining the efficacy of pre-ascent climbing route visual inspection on indoor sport climbers, they found that expert climbers benefited most from route preview by making fewer stops and stops of a shorter duration during their ascent (Sanchez et al., 2012). Their findings went in line with intervention studies that have shown that techniques such as imagery and video-modeling do influence climbing performance positively (e.g., Sanchez and Dauby, 2009).

In fact, route previewing likely plays a significant role in climbing performance. Whereas competitors in other sports might see their opponents performing (e.g., in gymnastics, figure skating, trampoline) and practice on the itinerary where competition will take place (e.g., a rally driving route, a cycling circuit, a golf course), in sport climbing none of this is permitted. Thus, if a climber misjudges a sequence of holds that s/he has never done before (nor has ever seen anyone doing), s/he will likely fail/fall. In sports where environmental constraints change across competitions, specific preparation has been suggested as critical to successful performance (Eccles et al., 2009). Findings from the present study provide further qualitative information on how accurate route previewing is believed to function, optimizing the planning for the ascent in two distinct manners. Advanced and expert climbers conferred central value to route previewing, in line with recent work from Seifert et al. (2017), who suggested that this activity may help climbers to pick up functional information about reachable, graspable and usable holds to chain movements and find the way up on the wall. Such ability to correctly view and interpret climbing route information prior to an ascent was confirmed as an essential skill when it comes to prepare and plan ascents, both cognitively and physically. That is, the climber would estimate how the ascent is likely to be best achieved in relation to planning strategically the progression on the route (ascent strategy forecasting) and enhancing strategic management in relation to the effort exerted on the route (ascent effort forecasting). Our participants described how such planning for an ascent allows them to: select an accurate and comprehensive movement repertoire relative to the specific demands of the route and reject ineffective movement; optimize effective movements; and link different movements upward the entire route.

The present study provides a comprehensive view of parameters to consider when planning, designing and delivering holistic and coherent training programs aimed at enhancing climbing performance. In climbing, when performing on-sight, a mistake may result in failure to complete the route at that time point, or result in later failure due to increased fatigue in recovering from the original mistake. Despite a mistake the climber may still complete the ascent but at an increased physical cost (i.e., energy expenditure), which may have short-term implications for additional planned ascents, especially in competition. Additionally, in competition, a sport lead climbing mistake may also result in non-completion due to being timed out. Failing to complete an ascent also means for the climber that the given route will not be performed on-sight. If programs and training regimes are to be developed for climbers, the specific characteristics of the different climbing modalities (e.g., on-sight vs. pre-practiced) and the specific interacting parameters that influence performance need further consideration. For instance, and probably due to the consequence of a fall in competitive climbing, a clear distinction was made between on-sight and pre-practiced modalities.

When it comes to competition, previous research has shown that pre-performance psychological states influence subsequent performance (Sanchez et al., 2010). Other physiological and attentional changes due to a heightened stress have been shown in climbing populations. For instance, Pijpers et al. (2003) investigated anxiety and performance relationships in climbing and found anxiety was exhibited at three levels; subjective, physiological and behavioral, and that increased anxiety resulted in greater uncertainty in movement sequence and hold selection. In a later study, Pijpers et al. (2006) investigated anxiety in perceiving and realizing affordances and found anxiety narrowed the visual field and that the climber’s perception of the actions necessary to progress were altered by their emotional state. In both studies, Pijpers et al. (2003, 2006) show that controlled and fluid movements are vital for success in climbing. Studies that examine the relation between route previewing, emotions and actual climbing performance is warranted to gain further knowledge and understanding on how to prepare climbers best when seeking optimal climbing performance.

Overall, findings from the present study indicate that the combination of the abovementioned parameters is necessary to progress up the route in general, and to overcome particularly difficult sections (cruxes). However, to elucidate these parameters further, it is necessary to consider their inter-relatedness and frame these within the environmental context of elite sport climbing performance. As the sport of climbing continues to develop, our findings provide a basis for further research that shall examine further how, each of these performance parameters identified, can most effectively be enhanced and optimized to influence performance positively.

The sport of climbing is rapidly developing whilst our understanding of the factors that influence performance is limited, and programs to enhance performance lack a robust ecologically valid evidence base. Our findings provide tentative for the design and delivery of training programs aimed at enhancing indoor sport climbing performance. In the present study, a comprehensive range of climbing performance parameters implicated in facilitating climbing performance achievement were identified. The importance of route previewing, which had been identified in previous studies, was confirmed. Current programs are typically developed on an ad hoc basis and, as a result, key performance parameters may be neglected. Even small differences in performance can be critical during elite competitions (conf. Sanchez et al., 2010), so a more holistic and coherent approach to training can be adopted now that a comprehensive range of predictors have been identified.

As the sport continues to develop, these new insights will also provide a basis for further investigation to establish how these key performance-related parameters can be most effectively enhanced. Taken together, findings from the present study provide a preliminary conceptual model with which to understand optimal lead-climbing performance on artificial climbing structures. Nevertheless, findings shall be taken with caution when it comes to generalize to the other two disciplines included in the Olympic program as they are very different in nature when compared to that of lead-climbing, even though competitors are requested to combine the three disciplines.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Université catholique de Louvain, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Post-Graduate Committee, Department of Emotion, Cognition and Health.

XS conceived and designed the study, carried out and transcribed the interviews, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XS and MT organized the database and performed the qualitative analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript developing and writing until manuscript was submitted in its final version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 4th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bishop, D. (2008). An applied research model for the sport sciences. Sports Med. 38, 253–263. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838030-00005

Boschker, M. S. J., Bakker, F. C., and Michaels, C. F. (2002). Memory for the functional characteristics of climbing walls: perceiving affordances. J. Motor Behav. 34, 25–36. doi: 10.1080/00222890209601928

Cox, S. M., and Fulsaas, K. (2003). Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, 7th Edn. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers Books.

de Geus, B., Villanueva, O., Discoll, S., and Meeusen, R. (2006). Influence of climbing style on physiological responses during indoor rock climbing on routes with the same difficulty. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 98, 489–496. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0287-5

Deweze, S., and Le Menestrel, M. (1987). Escalade Libre: Technique, Tactique, Entraînement. Paris: Robert Laffont.

Draper, N., Giles, D., Schöffl, V., Fuss, F. K., Watss, P., Wolf, P., et al. (2016). Comparative grading scales, statistical analyses, climber descriptors and ability grouping: international rock climbing research association position statement. Sports Technol. 8, 88–94. doi: 10.1080/19346182.2015.1107081

Eccles, D. W., Ward, P., and Woodman, T. (2009). Competition-specific preparation and expert performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 10, 96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.01.006

Espanña-Romero, V., Jensen, R. L., Sanchez, X., Ostrowski, M. L., Szekely, J. E., and Watts, P. B. (2012). Physiological responses in rock climbing with repeated ascents over a 10-week period. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 112, 821–828. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2022-0

Ferrand, C., Tetard, S., and Fontayne, P. (2006). Self-handicapping in rock climbing: a qualitative approach. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 18, 271–280. doi: 10.1080/10413200600830331

Finch, C. (2006). A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J. Sci. Med. Sport 9, 3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009

Giles, L. V., Rhodes, E. C., and Taunton, J. E. (2006). The physiology of rock climbing. Sports Med. 36, 529–545. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636060-00006

Hoibian, O. (2017). “A cultural history of mountaineering and climbing,” in Science of Climbing and Mountaineering, eds L. Seifert, A. Schweizer, and P. Wolf (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis), 1–16.

Holt, N. L., and Morley, D. (2004). Gender differences in psychosocial factors associated with athletic success during childhood. Sport Psychol. 18, 138–153. doi: 10.1123/tsp.18.2.138

Jones, G., and Johnson, M. I. (2016). A critical review of the incidence and risk factors for finger injuries in rock climbing. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 15, 400–409. doi: 10.1249/jsr.0000000000000304

Jones, G., Milligan, J., Llewellyn, D., Gledhill, A., and Johnson, M. I. (2017). Motivational orientation and risk taking in elite winter climbers: a qualitative study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 15, 25–40. doi: 10.1080/1612197x.2015.1069876

Jones, G., and Sanchez, X. (2017). “Psychological processes in the sport of climbing,” in Science of Climbing and Mountaineering, eds L. Seifert, A. Schweizer, and P. Wolf (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis), 244–256.

Jones, G., Schöffl, V., and Johnson, M. I. (2018). Incidence, diagnosis and management of injury in sport climbing and bouldering: a critical review. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 17, 396–401. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000534

Kelle, U. (1995). Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods and Practice. London: SAGE Publications.

Lemare, A., and Morrot, J. P. (1995). L’escalade: La Structure à la Portée de Tous. Paris: Editions Amphora.

MacLeod, D., Sutherland, D. L., Buntin, L., Whitaker, A., Aitchison, T., Watt, I., et al. (2007). Physiological determinants of climbing-specific finger endurance and sport rock climbing performance. J. Sports Sci. 25, 1433–1443. doi: 10.1080/02640410600944550

Martha, C., Sanchez, X., and Goma-i-Freixanet, M. (2009). Risk perception as a function of risk exposure amongst rock climbers. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 10, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.07.004

Mittelstaedt, R. (1997). Indoor climbing wall: the sport of the nineties. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 68, 26–29. doi: 10.1080/07303084.1997.10605024

Morrison, A. B., and Schöffl, V. R. (2007). Review of the physiological responses to rock climbing in young climbers. Br. J. Sports Med. 41, 852–861. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.034827

Muhr, T. (1997). The Knowledge Workbench. Short User’s Manual (Version 4.1). London: Sage Publication Software.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 3rd Edn. London: Sage Publications.

Pijpers, J. R., Oudejans, R. R. D., and Bakker, F. C. (2005). Anxiety-induced changes in movement behaviour during the execution of a complex whole-body task. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 58A, 428–445.

Pijpers, J. R., Oudejans, R. R. D., Bakker, F. C., and Beek, P. J. (2006). The role of anxiety in perceiving and realizing affordances. Ecol. Psychol. 18, 131–161. doi: 10.1207/s15326969eco1803_1

Pijpers, J. R., Oudejans, R. R. D., Holsheimer, F., and Bakker, F. C. (2003). Anxiety–performance relationships in climbing: a process-oriented approach. Psychol. Sport Exer. 4, 283–304. doi: 10.1016/s1469-0292(02)00010-9

Rubin, H. J., and Rubin, I. S. (2005). Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Sanchez, X., Boschker, M. S. J., and Llewellyn, D. J. (2010). Pre-performance psychological states and performance in an elite climbing competition. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20, 356–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00904.x

Sanchez, X., and Dauby, N. (2009). Imagery and video-modelling in sport climbing. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 41, 93–101.

Sanchez, X., Lambert, P. H., Jones, G., and Llewellyn, D. J. (2012). Efficacy of pre-ascent climbing route visual inspection in indoor sport climbing. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 22, 67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01151.x

Seifert, L., Cordier, R., Orth, D., Courtine, Y., and Croft, J. L. (2017). Role of route previewing strategies on climbing fluency and exploratory movements. PLoS One 12:e0176306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176306

Sheel, A. W. (2004). Physiology of sport rock climbing. Br. J. Sports Med. 38, 355–359. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.008169

Smith, B., and McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 11, 101–121. doi: 10.1080/1750984x.2017.1317357

Smyth, M. M., and Waller, A. (1998). Movement imagery in rock climbing: patterns of interference from visual, spatial and kinaesthetic secondary tasks. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 12, 145–157. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199804)12:2<145::aid-acp505>3.0.co;2-z

Sparkes, A. C., and Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health. Abingdon: Routledge.

Spradley, J. (1979). The Ethnographic Interview. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Sussman, S., Valente, T. W., and Rohrbach, L. A. (2006). Translation in the health professions: converting science into action. Eval. Health Prof. 2, 7–32. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284441

Vigouroux, L., Domalain, M., and Berton, E. (2011). Effect of object width on muscle and joint forces during thumb/index fingers grasping. J. Appl. Biomech. 27, 173–180. doi: 10.1123/jab.27.3.173

Watts, P. B. (2004). Physiology of difficult rock climbing. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 91, 361–372. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-1036-7

Watts, P. B., Joubert, L. M., Lish, A. K., Mast, J. D., and Wilkins, B. (2003). Anthropometry of young competitive sport rock climbers. Br. J. Sport Med. 37, 420–424. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.420

Keywords: climbing, extreme sports, lead-climbing, performance parameters, qualitative analysis, route finding, route previewing

Citation: Sanchez X, Torregrossa M, Woodman T, Jones G and Llewellyn DJ (2019) Identification of Parameters That Predict Sport Climbing Performance. Front. Psychol. 10:1294. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01294

Received: 15 December 2018; Accepted: 16 May 2019;

Published: 31 May 2019.

Edited by:

Maurizio Bertollo, Università degli Studi G. d’Annunzio Chieti e Pescara, ItalyReviewed by:

Ludovic Seifert, Université de Rouen, FranceCopyright © 2019 Sanchez, Torregrossa, Woodman, Jones and Llewellyn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xavier Sanchez, eGF2aWVyLnNhbmNoZXpAaGguc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.