- 1Center for Social Psychological Answers to Real-World Questions (SPARQ), Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

U.S. Americans repeatedly invoke the role of “culture” today as they struggle to make sense of their increasingly diverse and divided worlds. Given the demographic changes, cultural interactions and hybridizations, and shifting power dynamics that many U.S. Americans confront every day, we ask how psychological scientists can leverage insights from cultural psychology to shed light on these issues. We propose that the culture cycle—a tool that represents culture as a multilayered, interacting, dynamic system of ideas, institutions, interactions, and individuals—can be useful to researchers and practitioners by: (1) revealing and explaining the psychological dynamics that underlie today’s significant culture clashes and (2) identifying ways to change or improve cultural practices and institutions to foster a more inclusive, equal, and effective multicultural society.

U.S. Americans are calling out the role of “culture” today as they struggle to make sense of their increasingly diverse and divided worlds. To say “It’s cultural,” or “It’s a culture clash,” or “We need a culture change” is becoming idiomatic. People invoke culture as they confront pressing issues in business, government, law enforcement, entertainment, education, and more, and as they grapple with power and inequality in the institutions and practices of these domains (e.g., racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, imperialism). Headlines and social media feeds are populated daily with news of culture clashes or cultural divides that take place both within organizations and across society. From gender clashes between men and women in the workplace, to race clashes between the police and communities of color in American suburbs and cities, to political clashes between conservatives and liberals around the nation, cultural differences and cultural misunderstandings are consistently in the spotlight (Armacost, 2016; Vance, 2016; Chang, 2018).

At the heart of these culture clashes are questions about the meaning and nature of social group differences, as well as the ways in which these differences are more often than not constructed as forms of inequality and marginalization (Markus, 2008; Markus and Moya, 2010; Salter and Adams, 2013; Adams et al., 2015; Omi and Winant, 2015; Adler and Aycan, 2018). Given the demographic changes, cultural interactions and hybridizations, and shifting power dynamics that many U.S. Americans confront every day, we ask how psychological scientists can leverage insights from cultural psychology to shed light on these issues. We propose that the culture cycle—a schematic or tool that represents culture as a multilayered, interacting, dynamic system of ideas, institutions, interactions, and individuals—can be useful to researchers and practitioners by: (1) revealing and explaining the psychological dynamics that underlie today’s significant culture clashes and (2) identifying ways to change or improve cultural practices and institutions to foster a more inclusive, equal, and effective multicultural society.

The Culture Cycle

When psychological scientists theorize about the role of culture, the focus is often on how psychological processes are implicitly and explicitly shaped by features of the sociocultural contexts or worlds that people inhabit, as well as how these psychological processes in turn reflect and reproduce those sociocultural contexts or worlds (Markus and Conner, 2014; Gelfand and Kashima, 2016; Cohen and Kitayama, 2019). Psychologists Morris et al. (2015), for example, define culture as “a loosely integrated system of ideas, practices, and social institutions that enable coordination of behavior in a population” (p. 632). Other scholars (e.g., Shweder, 1991, 2003; Adams and Markus, 2004), drawing on the insights of anthropologists Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952), expand on this idea and also highlight the dynamic, ongoing processes by which “the cultural” and “the psychological” necessarily and mutually depend upon as well as co-construct one another:

Culture consists of explicit and implicit patterns of historically-derived and selected ideas and their embodiment in institutions, practices, and artifacts; cultural patterns may, on one hand, be considered as products of action, and on the other as conditioning elements of further action. (as summarized by Adams and Markus, 2004, p. 341)

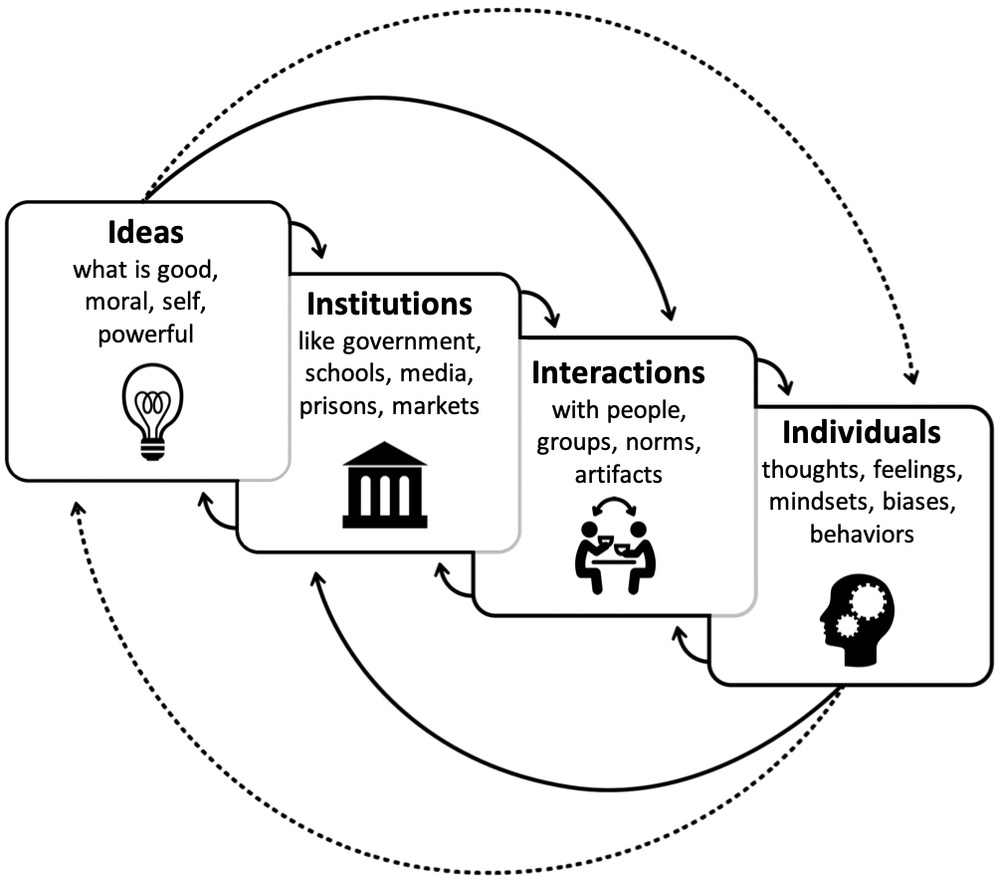

This definition conceptualizes culture as a system or a cycle. In this cycle, sociocultural patterns shape or guide people’s actions, while people’s actions, in turn, can either reinforce and reflect or contest and change these sociocultural patterns. To visually and conceptually represent the dynamic processes through which the cultural and the psychological interact and mutually constitute one another, we use a tool that we call the “culture cycle” (Figure 1). This schematic depicts culture as a system of four, dynamically interacting and interdependent layers (Fiske et al., 1998; Markus and Kitayama, 2010; Markus and Conner, 2014). Here, culture is made up of the ideas, institutions, and interactions that guide and reflect individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and actions (Markus and Conner, 2014).

Figure 1. The culture cycle. Adapted from Fiske et al. (1998), Markus and Conner (2014), and Markus and Kitayama (2010).

Analytically, the culture cycle starts from either the left-hand or the right-hand side. From the left, the ideas, institutions, and interactions of an individual’s mix of cultures shape the self, so that a person thinks, feels, and acts in ways that reflect and perpetuate these cultures. From the right, individuals participate in and create (i.e., reinforce, resist, and/or change) cultures to which other people, both in the present and throughout time, adapt. Psychologists typically focus on the individuals level, which includes identities, self-concepts, thoughts, feelings, mindsets, biases, and behaviors. These psychological processes can be culturally shaped as well as feed back into the cycle to shape culture (e.g., Markus and Kitayama, 2010; Varnum et al., 2010; Boiger and Mesquita, 2012).

The next layer of the culture cycle is the interactions level. As people interact with other people and with human-made products (i.e., cultural artifacts), their ways of life manifest in everyday situations that follow seldom-spoken norms about the right ways to behave at home, school, work, worship, and play. Guiding these practices are the everyday cultural products—the stories, songs, advertisements, social media, and tools (e.g., phones, laptops, tablets)—that make some ways to think, feel, and act easier, more fluid, or better supported by the particular worlds a person inhabits (e.g., Tsai et al., 2007; Morling and Lamoreaux, 2008; Lamoreaux and Morling, 2012).

The next layer of culture is made up of the institutions level, within which everyday interactions take place. Institutions spell out and formalize the rules for a society and include government, religious, legal, economic, educational, and scientific institutions. For the most part, people may be unaware of all the institutions, laws, and policies at play in their cultures. Yet they exert a formidable force by providing incentives that foster certain practices, interactions, and behaviors while inhibiting others (e.g., Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010, 2014; Tankard and Paluck, 2017).

The last layer of the culture cycle is the ideas level, and it is made up of the pervasive, often invisible, historically derived and collectively held ideologies, beliefs, and values about what is good, right, moral, natural, powerful, real, and necessary that inform institutions, interactions, and ultimately, individuals (e.g., Hamedani et al., 2013; Leavitt et al., 2015; Master et al., 2016). Because of them, cultures can appear to have overarching themes or patterns that persist, to some extent, across time. To be sure, cultures have multiple exceptions to their own foundational rules and values. But they also contain general patterns that can be detected, studied, and changed.

A few clarifying notes on the culture cycle. First, all four interacting layers of the culture cycle are important and mutually depend upon one another; none is assumed to be more influential, theoretically prior to, or separable from the others. Second, cultures are always dynamic, never static, and can change or evolve over time. As such, all levels continually influence each other and a change at any one level can produce changes in other levels. Third, the culture cycle includes structures and structural dynamics and does not separate the concept of “culture” from “structure.” And finally, culture cycles are embedded within larger natural and ecological systems that can interact with and exert influence on a given culture.

Many different kinds of cultures can be mapped and analyzed using the culture cycle (Cohen, 2014; Markus and Conner, 2014; Gelfand and Kashima, 2016; Cohen and Kitayama, 2019). Culture can be geographically based and focus on familiar distinctions—such as the East versus the West or the Global North versus the Global South—but it also encompasses other distinctions like social class or socioeconomic status; race, ethnicity, or tribe; gender and sexuality; region of the country, state, or city; religion; profession, workplace, or organization; generation; or immigration status. “Culture” or “cultural context” can serve as a label for any significant (i.e., socially meaningful) category associated with a set of shared ideas, practices, and products that structure and organize behavior. Since the cultural and the psychological make each other up, one way to change minds and behaviors is to change cultures, just as one way to change cultures is to change minds and behaviors.1

Using the Culture Cycle to Understand Culture Clashes and Catalyze Change

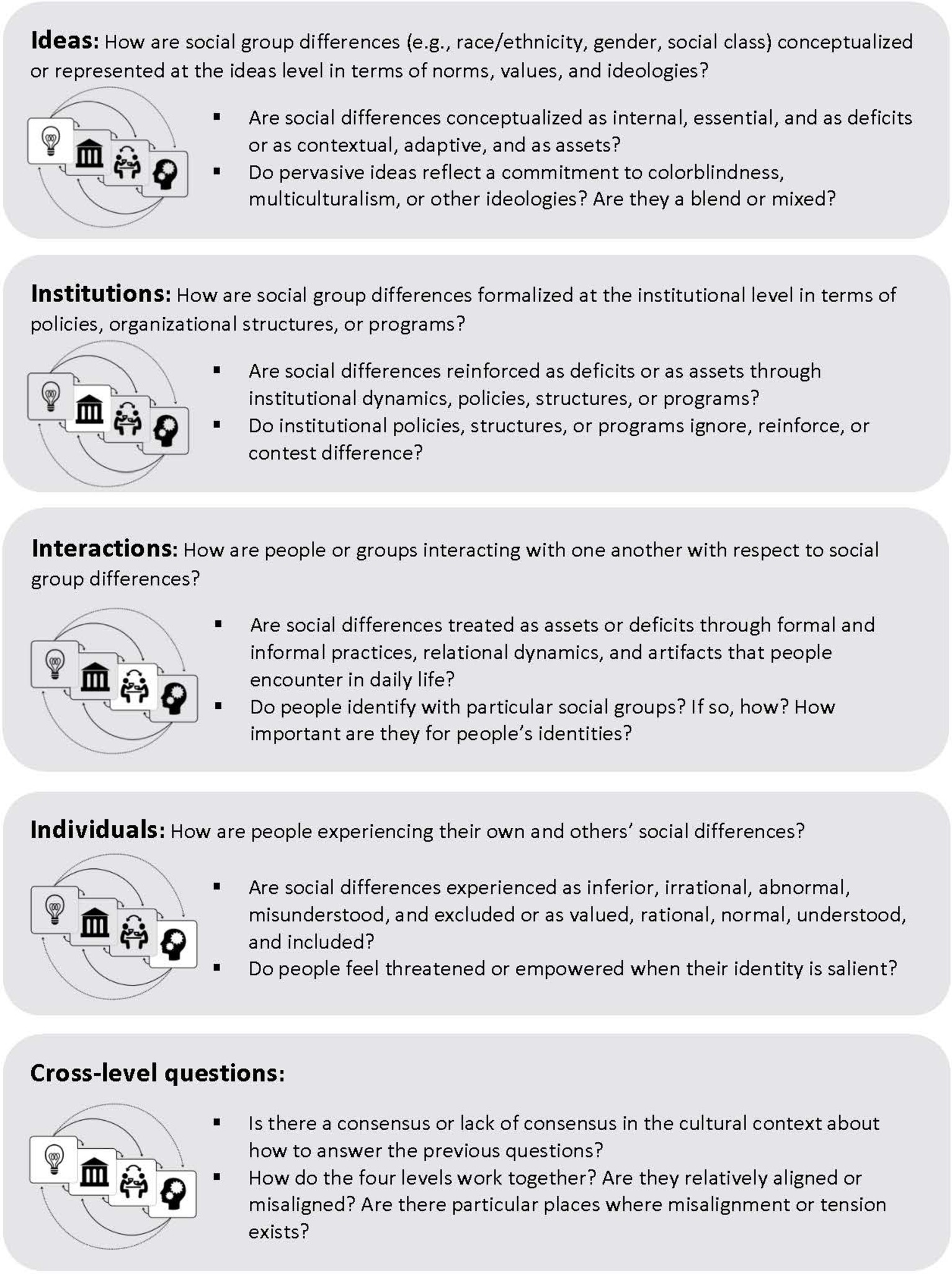

We propose that addressing current culture clashes and divides through more inclusive, equal, and effective institutions and practices will require changing how people encounter and experience the meaning and nature of social group differences themselves (Markus, 2008; Markus and Moya, 2010; Plaut, 2010). At the heart of today’s most timely culture clashes and divides is a pervasive process of devaluing the less powerful or non-dominant group in contrast with the more powerful or dominant group. In the process, differences are cast as the result of so-called negative and inherent shared behavioral characteristics or tendencies rather than as a matter of divergent life experiences or differential access to resources, power, and/or status—e.g., women = incompetent (versus men = competent), black = criminal (versus white = lawful), and liberals = weak (versus conservatives = strong; e.g., Prentice and Carranza, 2002; Eberhardt et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2012). To analyze how cultural differences are constructed and understood in a given setting, we recommend starting with the following set of orienting questions (Figure 2). These questions are designed to help prospective culture changers map how social differences are constructed within a given culture cycle (e.g., as assets versus deficits, through colorblind versus multicultural ideologies), identify where inequalities exist (e.g., at the ideas, institutions, interactions, and/or individuals levels), and locate places within the culture cycle to intervene. To provide an example, we apply this method to unpack the cultural and psychological dynamics that underlie one culture clash prevalent on U.S. American college campuses today—the clash between underrepresented students (e.g., low-income students and/or students of color) and the mainstream (e.g., middle- to upper-class and White) culture of higher education (Wong, 2015; Wong and Green, 2016).

Figure 2. Using the culture cycle to understand culture clashes and catalyze change: Mapping social group differences. Adapted from Markus and Hamedani (2019).

The culture of American higher education, especially at elite colleges and universities, reflects and promotes assumptions about what it means to be “smart,” “educated,” and “successful.” These assumptions are not neutral, but are instead powerfully shaped by White, middle- to upper-class beliefs, norms, and values that privilege independence and innate intelligence (Fryberg et al., 2013; Quaye and Harper, 2014; Canning et al., 2019). As a result, students of color and students from low-income or working-class backgrounds often feel excluded in these educational settings due to threats to their social identities (e.g., stereotypes about race and intelligence) or mismatches with their interdependent norms and values (e.g., achieving for one’s family or community instead of oneself; Ostrove and Long, 2007; Walton and Cohen, 2007; Stephens et al., 2012; Covarrubias and Fryberg, 2015). These experiences of exclusion can lead students to question whether they fit or belong in college. Students from low-income or working-class backgrounds can also be unfamiliar with the “rules of the game” needed to succeed in higher education, which can undermine their sense of empowerment and efficacy (Housel and Harvey, 2010; Reay et al., 2009). These psychological challenges work alongside disparities in resources and pre-college preparation to fuel a persistent achievement gap between these students and their advantaged peers (Astin and Oseguera, 2004; Bowen et al., 2005; Sirin, 2005; Goudeau and Croizet, 2017). As such, the culture clash that results from participating in mainstream college environments can systematically disadvantage underrepresented students (Stephens et al., 2012; Brannon et al., 2015; Covarrubias et al., 2016).

What kinds of culture clashes do underrepresented students experience at each level of a college or university’s culture cycle? Where might practitioners intervene to make a college or university’s values, policies, and practices more inclusive and equitable? Using the orienting questions in Figure 2, we can map this culture clash as well as corresponding interventions at each layer or level of the cycle. Starting with the individuals level (Figure 2: How are people experiencing their own or others’ social differences?), research shows that underrepresented students often feel like they do not fit or belong on college and university campuses, which can be due to repeated everyday experiences like microaggressions that take place at the interactions level (Figure 2: How are people or groups interacting with one another with respect to social group differences?) during intergroup encounters in classrooms or in the dorms (Yosso et al., 2009; Sue, 2010). These factors can lead students to experience the college environment as threatening to their social identities and to view their social differences as deficits or as something that puts them at a disadvantage.

At the institutions level (Figure 2: How are social group differences formalized at the institutional level in terms of policies, organizational structures, or programs?), these threats to fit or belonging can be reinforced in multiple ways, including a lack of representation in the college curriculum (e.g., not seeing people with your background reflected in lecture examples, readings, and research), and in positions of authority throughout the university (e.g., as faculty and administrators; Brannon et al., 2015; Quaye and Harper, 2014). Further, at the ideas level [Figure 2: How are social group differences (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, social class) conceptualized or represented at the ideas level in terms of norms, values, and ideologies?], while many college and universities today claim to value diversity, they rarely do so in ways that include and affirm underrepresented students’ backgrounds and experiences—that challenge prevailing assumptions about what it means to be a smart, educated, or successful student (i.e., an independent and innately intelligent student; Chang, 2002; Stephens et al., 2012). Underrepresented students’ backgrounds and ways of being, therefore, are frequently devalued or seen as deficits in mainstream colleges and universities rather than valued and seen as assets or resources, which undermines such commitments to diversity, equity, and inclusion and reinforces color- or identity-blindness.

To change their cultures, colleges and universities need to do more to challenge how students’ social differences are experienced and constructed at each layer of the culture cycle. Research suggests several evidence-based strategies to catalyze culture change and make higher education more inclusive and equitable. To help underrepresented students feel more included and empowered at the individuals level, for instance, colleges and universities can do more to value and promote diversity, equity, and inclusion as crucial components of a high-quality education for a twenty-first century workforce in their missions and institutional strategies at the ideas level (Hurtado, 2007; Gurin et al., 2013). Next, at the institutions level, colleges and universities can integrate intergroup dialogue classes and other learning experiences about diversity, equity, and inclusion into the college curriculum for all students and across all courses of study, as well as implement hiring and promotion policies that foster the diversification of faculty and administrators (Hurtado, 2005; Gurin et al., 2013; Brannon, 2018; Stephens et al., 2019). At the interactions level, colleges and universities can better support students by providing opportunities for them to expand their networks and connect with mentors and alumni that share their backgrounds and have found pathways to success (Girves et al., 2005; Harper, 2008). While some of these strategies focus on transforming the norms of higher education itself, others involve better supporting students on their journeys through institutions that still have much work to do. None of these changes alone are a panacea, and may fail to support long-term and sustainable change if they are not built into and fostered by the larger college culture as well as lived out and reinforced through the everyday actions of the people in that culture.

Ideally, culture change is most likely to progress and have the greatest impact when there is change at each level of the culture cycle and these changes work together to support one another. As noted previously, all four levels of the culture cycle are equally influential. When it comes to culture change, however, culture changers need to consider whether the levels are working together to reinforce or buttress one another, or whether they might be working against one another, causing spots of tension and misalignment in a culture (Porras and Silvers, 1991; Morgan, 2006; Kotter, 2012; Gibbons, 2015; Coyle, 2018; see the Figure 2 “cross-level” questions). For example, if colleges and universities express a commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion at the ideas level, but fail to take a hard look at how their current policies, programs, and practices are impacting underrepresented students at the institutions and interactions levels, diversity efforts are likely to be seen as disingenuous by student communities and culture change efforts are likely to have a limited influence on the institution as a whole.

Prospective culture changers also need to consider whether people within a given cultural context have consensus or a shared understanding of what is taking place and why in a given setting (see also the Figure 2 “cross-level” questions). For example, students from underrepresented groups and administrators at colleges and universities (many of whom are from majority groups) may have divergent perspectives on how to make change in their institutions with respect to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Students may favor more bottom-up, transformative efforts that are instigated by their peers, while administrators might favor more top-down, incremental changes brought about from long-term institutional study. While both groups might have valid perspectives, they might buy into and trust different culture change strategies. Culture change efforts that ignore the ideas and strategies of the lower status or low power side of the clash, however, are likely to be less effective than those that incorporate them.

Concluding Comments

The phrase “It’s cultural” underscores the frustration that people feel when a problem is big, messy, and seems intractable. Sometimes people use it as a way to say that a problem is systemic, but they also often use it as a way to evade responsibility and say that a significant societal problem is not really their problem. We do not deny that culture change is difficult work and may have unintended consequences. Culture changers need to keep in mind how the interconnected, shifting dynamics that make up the culture cycle afford certain ways of being while constraining or downwardly constituting others, and that these dynamics can change or rebalance when intervening in the cycle. Culture changers also need to recognize that to foster more inclusive, equal, and effective institutions and practices, the deeper work will involve changing how cultures construct the meaning and nature of social group differences themselves.

Given that psychologists are typically trained to focus on the individual and sometimes the interactional levels, they tend to zero in on changing people’s mindsets or construals without fully considering how these micro- or meso-level changes might be blocked rather than supported by the larger institutional and social forces at play. On the other hand, practitioners and policymakers often focus on macro-level social and institutional factors and, in turn, do not pay close enough attention to whether the changes have resonance and carry over to the interactional and individual levels. Both psychologists and practitioners alike can also overlook the power individuals have to change their cultures in bottom-up ways through their actions, by instead focusing on how cultures shape people rather than how people also shape their cultures. With these considerations in mind, a culture cycle approach can be useful to scholars and practitioners alike to help them anticipate areas of misalignment and tension, forecast unanticipated consequences, and foster more holistic, dynamic, and multidirectional approaches to culture change.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the theory, conceptualization, and writing of the paper. MH had primary responsibility for writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. The kind of intentional or strategic culture change that we discuss here differs from other significant work in the field on cultural evolution or long-term social change, which is primarily concerned with demonstrating and documenting how cultures or societies shift, change, or evolve across time (e.g., Twenge et al., 2012; Greenfield, 2013; Varnum and Grossmann, 2017).

References

Adams, G., Dobles, I., Gómez, L. H., Kurtiş, T., and Molina, L. E. (2015). Decolonizing psychological science: introduction to the special thematic section. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 3, 213–238. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v3i1.564

Adams, G., and Markus, H. R. (2004). “Toward a conception of culture suitable for a social psychology of culture” in The psychological foundations of culture. eds. M. Schaller and C. S. Crandall (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 335–360.

Adler, N. J., and Aycan, Z. (2018). Cross-cultural interaction: what we know and what we need to know. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 5, 307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104528

Armacost, B. (2016, August 19). The organizational reasons police departments don’t change. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2016/08/the-organizational-reasons-police-departments-dont-change

Astin, A. W., and Oseguera, L. (2004). The declining “equity” of American higher education. Rev. High. Educ. 27, 321–341. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2004.0001

Boiger, M., and Mesquita, B. (2012). The construction of emotion in interactions, relationships, and cultures. Emot. Rev. 4, 221–229. doi: 10.1177/1754073912439765

Bowen, W. G., Kurzweil, M. A., and Tobin, E. M. (2005). From bastions of privilege to engines of opportunity. Chron. High. Educ. 51:B18.

Brannon, T. N. (2018). Reaffirming King’s vision: the power of participation in inclusive diversity efforts to benefit intergroup outcomes. J. Soc. Issues 74, 355–376. doi: 10.1111/josi.12273

Brannon, T. N., Markus, H. R., and Taylor, V. J. (2015). “Two souls, two thoughts,” two self-schemas: double consciousness can have positive academic consequences for African Americans. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 586–609. doi: 10.1037/a0038992

Canning, E. A., Muenks, K., Green, D. J., and Murphy, M. C. (2019). STEM faculty who believe ability is fixed have larger racial achievement gaps and inspire less student motivation in their classes. Sci. Adv. 5:eaau4734. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau4734

Chang, E. (2018). Brotopia: Breaking up the boys’ club of silicon valley. (New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin).

Chang, M. J. (2002). Perservation or transformation: where’s the real educational discourse on diversity? Rev. High. Educ. 25, 125–140. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2002.0003

A. B. Cohen (Ed.) (2014). Culture reexamined: Broadening our understanding of social and evolutionary influences. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association).

Cohen, D., and Kitayama, S. (2019). Handbook of cultural psychology, 2nd edn. (New York, NY: Guilford Press).

Covarrubias, R., and Fryberg, S. A. (2015). Movin’ on up (to college): first-generation college students’ experiences with family achievement guilt. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 21, 420–429. doi: 10.1037/a0037844

Covarrubias, R., Herrmann, S. D., and Fryberg, S. A. (2016). Affirming the interdependent self: implications for Latino student performance. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 38, 47–57. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2015.1129609

Coyle, D. (2018). The culture code: The secrets of highly successful groups. (New York, NY: Bantam Books).

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., and Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing black: race, crime, and visual processing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 876–893. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.876

Fiske, A., Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., and Nisbett, R. E. (1998). “The cultural matrix of social psychology” in The handbook of social psychology, Vol. 2, 4th edn. eds. D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (San Francisco: McGraw-Hill), 915–981.

Fryberg, S. A., Covarrubias, R., and Burack, J. A. (2013). Cultural models of education and academic performance for Native American and European American students. Sch. Psychol. Int. 34, 439–452. doi: 10.1177/0143034312446892

Gelfand, M. J., and Kashima, Y. (2016). Culture: advances in the science of culture and psychology [special issue]. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 8. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/current-opinion-in-psychology/vol/8

Gibbons, P. (2015). The science of successful organizational change: How leaders set strategy, change behavior, and create an agile culture. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Financial Times Press).

Girves, J. E., Zepeda, Y., and Gwathmey, J. K. (2005). Mentoring in a post-affirmative action world. J. Soc. Issues 61, 449–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00416.x

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., and Haidt, J. (2012). The moral stereotypes of liberals and conservatives: exaggeration of differences across the political spectrum. PLoS One 7:e50092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050092

Greenfield, P. M. (2013). The changing psychology of culture from 1800 through 2000. Psychol. Sci. 24, 1722–1731. doi: 10.1177/0956797613479387

Goudeau, S., and Croizet, J. C. (2017). Hidden advantages and disadvantages of social class: how classroom settings reproduce social inequality by staging unfair comparison. Psychol. Sci. 28, 162–170. doi: 10.1177/0956797616676600

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., and Zúñiga, X. (2013). Dialogue across difference: Practice, theory, and research on intergroup dialogue. (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation).

Hamedani, M. G., Markus, H. R., and Fu, A. S. (2013). In the land of the free, interdependent action undermines motivation. Psychol. Sci. 24, 189–196. doi: 10.1177/0956797612452864

Harper, S. R. (2008). Creating inclusive campus environments for cross-cultural learning and student engagement. (Washington, DC: NASPA, Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education).

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Bellatorre, A., Lee, Y., Finch, B. K., Muennig, P., and Fiscella, K. (2014). Structural stigma and all-cause mortality in sexual minority populations. Soc. Sci. Med. 103, 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.005

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., McLaughlin, K. A., Keyes, K. M., and Hasin, D. S. (2010). The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. Am. J. Public Health 100, 452–459. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.168815

T. H. Housel and V. L. Harvey (Eds.) (2010). The invisibility factor: Administrators and faculty reach out to first-generation college students. (Boca Raton, FL: Brown Walker Press).

Hurtado, S. (2005). The next generation of diversity and intergroup relations research. J. Soc. Issues 61, 595–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00422.x

Hurtado, S. (2007). Linking diversity with the educational and civic missions of higher education. Rev. High. Educ. 30, 185–196. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2006.0070

Kroeber, A. L., and Kluckhohn, C. K. M. (1952). Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions (Papers of the Peabody Museum, Vol. 47, No. 1). (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Lamoreaux, M., and Morling, B. (2012). Outside the head and outside individualism–collectivism: further meta-analyses of cultural products. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 43, 299–327. doi: 10.1177/0022022110385234

Leavitt, P. A., Covarrubias, R., Perez, Y. A., and Fryberg, S. A. (2015). “Frozen in time”: the impact of Native American media representations on identity and self-understanding. J. Soc. Issues 71, 39–53. doi: 10.1111/josi.12095

Markus, H. (2008). Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity. Am. Psychol. 63, 651–670. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.63.8.651

Markus, H. R., and Conner, A. C. (2014). Clash!: How to thrive in a multicultural world. (New York, NY: Penguin (Hudson Street Press)).

Markus, H. R., and Hamedani, M. G. (2019). “People are culturally shaped shapers: the psychological science of culture and culture change” in Handbook of cultural psychology, 2nd edn. eds. D. Cohen and S. Kitayama (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 11–52.

Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. (2010). Cultures and selves: a cycle of mutual constitution. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 420–430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557

Markus, H. R., and Moya, P. (2010). Doing race: 21 essays for the 21st century. (New York, NY: W. W. Norton).

Master, A., Cheryan, S., and Meltzoff, A. N. (2016). Computing whether she belongs: stereotypes undermine girls’ interest and sense of belonging in computer science. J. Educ. Psychol. 108, 424–437. doi: 10.1037/edu0000061

Morling, B., and Lamoreaux, M. (2008). Measuring culture outside the head: a meta-analysis of individualism—collectivism in cultural products. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 199–221. doi: 10.1177/1088868308318260

Morris, M. W., Chiu, C. Y., and Liu, Z. (2015). Polycultural psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 631–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015001

Omi, M., and Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States. 3rd edn. (New York, NY: Routledge). (Original work published 1986).

Ostrove, J. M., and Long, S. M. (2007). Social class and belonging: implications for college adjustment. Rev. High. Educ. 30, 363–389. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2007.0028

Plaut, V. C. (2010). Diversity science: why and how difference makes a difference. Psychol. Inq. 21, 77–99. doi: 10.1080/10478401003676501

Porras, J. I., and Silvers, R. C. (1991). Organization development and transformation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 42, 51–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.000411

Prentice, D. A., and Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: the contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychol. Women Q. 26, 269–281. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Quaye, J., and Harper, S. R. (2014). Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations. 2nd edn. (New York, NY: Routledge).

Reay, D., Crozier, G., and Clayton, J. (2009). “Strangers in paradise”?: working-class students in elite universities. Sociology 43, 1103–1121. doi: 10.1177/0038038509345700

Salter, P., and Adams, G. (2013). Toward a critical race psychology. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 7, 781–793. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12068

Shweder, R. A. (1991). Thinking through cultures: Expeditions in cultural psychology. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Shweder, R. A. (2003). Why do men barbeque?: Recipes for cultural psychology. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 75, 417–453. doi: 10.3102/00346543075003417

Stephens, N. M., Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Johnson, C. S., and Covarrubias, R. (2012). Unseen disadvantage: how American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1178–1197. doi: 10.1037/a0027143

Stephens, N. M., Hamedani, M. G., and Townsend, S. S. M. (2019). Difference matters: teaching students a contextual theory of difference can help them succeed. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 156–174. doi: 10.1177/1745691618797957

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons).

Tankard, M. E., and Paluck, E. L. (2017). The effect of a Supreme Court decision regarding gay marriage on social norms and personal attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1334–1344. doi: 10.1177/0956797617709594

Tsai, J. L., Louie, J. Y., Chen, E. E., and Uchida, Y. (2007). Learning what feelings to desire: socialization of ideal affect through children’s storybooks. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 17–30. doi: 10.1177/0146167206292749

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., and Gentile, B. (2012). Increases in individualistic words and phrases in American books, 1960–2008. PLoS One 7:e40181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040181

Varnum, M. E., and Grossmann, I. (2017). Cultural change: the how and the why. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 956–972. doi: 10.1177/1745691617699971

Varnum, M. E., Grossmann, I., Kitayama, S., and Nisbett, R. E. (2010). The origin of cultural differences in cognition: the social orientation hypothesis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 19, 9–13. doi: 10.1177/0963721409359301

Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: race, social fit, and achievement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 82–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Wong, A. (2015, May 21). The renaissance of student activism. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: www.theatlantic.com

Wong, A., and Green, A. (2016, April 4). Campus politics: A cheat sheet. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: www.theatlantic.com

Keywords: culture, multiculturalism, inequality, culture change, cultural divides, identity and conflict

Citation: Hamedani MYG and Markus HR (2019) Understanding Culture Clashes and Catalyzing Change: A Culture Cycle Approach. Front. Psychol. 10:700. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00700

Edited by:

Glenn Adams, University of Kansas, United StatesReviewed by:

Phia S. Salter, Texas A&M University, United StatesJozefien De Leersnyder, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2019 Hamedani and Markus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mar Yam G. Hamedani, bWFyeWFtaEBzdGFuZm9yZC5lZHU=

Mar Yam G. Hamedani

Mar Yam G. Hamedani Hazel Rose Markus

Hazel Rose Markus