94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 19 March 2019

Sec. Cognition

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00346

The emergence of enduring antisocial personality changes in previously normal individuals, or “acquired sociopathy,” has consistently been reported in patients with bilateral injuries of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Over the past three decades, cases of acquired sociopathy with (a) bilateral or (b) unilateral sparing of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex have been reported. These cases indicate that at least in a few individuals (a') neural structures beyond the ventromedial prefrontal cortex are also critical for normal social behavior, and (b') the neural underpinnings of social cognition may be lateralized to one cerebral hemisphere. Moreover, researchers have presented evidence that lesion laterality and gender may interact in the production of acquired sociopathy. In the present review, we carried out a comprehensive literature survey seeking possible interactions between gender and hemispheric asymmetry in acquired sociopathy. We found 85 cases of acquired sociopathy due to bilateral (N = 48) and unilateral (N = 37) hemispheric injuries. A significant association between acquired sociopathy and right hemisphere damage was found in men, whereas lesions were bilateral in most women with acquired sociopathy. The present survey shows that: (i) the number of well-documented single-cases of acquired sociopathy is surprisingly small given the length of the historical record; (ii) acquired sociopathy was significantly more frequent in men after an injury of the right or of both cerebral hemispheres; and (iii) in most women who developed acquired sociopathy the injuries affected both cerebral hemispheres. These findings may be especially valuable to neuroscientists and to functional neurosurgeons in particular for the planning of tumor resections as well as for the choice of the best targets for therapeutic neuromodulation.

Eslinger and Damasio coined the expression “acquired sociopathy” to describe the changes in personality of EVR, a comptroller in a home-building firm who underwent a lasting change in personality following the surgical removal of an olfactory groove meningioma. EVR'S normal cognitive performance contrasted with his severe loss of social tact and comportment, which culminated in bankruptcy and abandonment by his wife and friends. In contrast to individuals with developmental psychopathy, who “never learn socially acceptable patterns of behavior” (Eslinger and Damasio, 1985, p. 1737), EVR had learned and engaged in such patterns for most of his life; however, after his brain damage he failed to behave accordingly in real-life situations. The report by Eslinger and Damasio gave breath to the study of the neural underpinnings of human social behavior and its drastic changes following damage to the vmPFC (Barrash et al., 2000).

Pari passu with the renewed interest in the antisocial changes of personality due to vmPFC damage, investigators have documented the emergence of acquired sociopathy in lesions outside the vmPFC, more specifically, in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Eslinger et al., 1999; Eslinger and Biddle, 2000), rostrobasal forebrain (Poeck and Pilleri, 1965; Gorman and Cummings, 1992), ventromedial hypothalamus (Flynn et al., 1988), anterior temporal lobes (Relkin et al., 1996; Miller et al., 1999), anterior cingulate (Tow and Whitty, 1953; Angelini et al., 1980), medial thalamus (Sandson et al., 1991), basal ganglia (Richfield et al., 1987; Mendez et al., 1989), and rostral brainstem (Omar et al., 2007). In most cases, the behavioral changes were enmeshed in a fabric of more elementary symptoms, such as somnolence and hyperphagia, which usually reflect damage to functionally heterogeneous neural systems (Alpers, 1937). Conversely, sociopathy was surprisingly absent in patients with even extensive bilateral prefrontal (PF) damage (Penfield and Evans, 1935; Rylander, 1939; Hebb and Penfield, 1940; Nichols and Hunt, 1940; Ghosh et al., 2014; Plaza et al., 2014); still in others the brain damage had little if any impact on socio-occupational status (Tranel et al., 2005), exerting even a paradoxically beneficial effect in some (e.g., Labbate et al., 1997; cases OF and EB, Storey, 1970; King et al., 2017). These discrepancies raise the possibility that in at least some cases the laterality of the hemispheric lesion may be decisive for the development of sociopathy; in other words, damage to one cerebral hemisphere might be sufficient to produce sociopathy in at least a few previously normal individuals. A reliable prediction of whom these individuals are might bear important theoretical and practical implications.

Despite the aforementioned clues on a possible asymmetric representation of acquired sociopathy in the cerebral hemispheres, few researchers have pursued this line of inquiry. The most consistent studies on lesion laterality and acquired sociopathy have been carried out by Tranel and colleagues, who additionally investigated a possible interaction between lesion laterality and gender. In four thoroughly matched cases, they found that acquired sociopathy in one man resulted from damage to the right vmPFC, while in one woman it was caused by damage to the left vmPFC; the reverse match was not attended by changes in personality (Tranel et al., 2005). These findings were later extended to four patients suffering from pharmacoresistant epilepsy who underwent unilateral ablation of the right or the left anterior temporal lobe. The anterior temporal lobes encompass a collection of neural structures which sustain profuse bidirectional connections with the ventromedial, orbitofrontal and insular cortices as well as with the amygdala (Pascalau et al., 2018). As in the vmPFC cases, sociopathy was associated with left lobectomy in one woman and with right lobectomy in one man (Tranel and Hyman, 1990). Thus, besides lesion laterality, the Tranel et al. studies imply that gender should likewise be considered critical for the production of acquired sociopathy (Tranel and Bechara, 2010).

Gender asymmetry has been supported by studies which have consistently found higher rates of antisocial behavior among men relative to women. This “gender gap,” which is already noticeable at an early age, remains stable from childhood to adulthood (with the exception of a discrete period limited to adolescence), and has been documented in different cultures (Choy et al., 2017). Although the male-to-female ratio of lifelong antisocial conduct is 10:1, research has also shown that boys and girls with persistent antisocial behavior are identical in terms of poor discipline, family adversity, pattern of cognitive deficits, undercontrolled temperament, hyperactivity, and rejection by peers; the relaxation of diagnostic criteria of conduct disorder for girls did not substantially change these conclusions (Moffitt et al., 2004). Therefore, the weight of the evidence indicates that men are referred more often than women to psychiatric treatment and to the justice system because of differences that are intrinsic to gender, the cultural milieu playing an adjunctive role by either enhancing or curbing the overt expression of antisocial acts.

A growing body of neuroscientific research has otherwise shown that the aforementioned differences largely reflect the aspects of the cerebral organization that underpin differences in men and women (Cahill, 2006). A representative instance of the interplay between gender biology and culture was provided by Fumagalli et al. (2010), who studied the performance of 100 right-handed adults (50 men and 50 women) on a moral judgment task; volunteers were further sorted into Catholics and non-Catholics according to their stated religious belief systems. They found that only gender predicted the kind of moral judgements by men and women, men producing a significantly higher proportion of utilitarian responses than women; religious belief and education played no role in differentiating the styles of moral decisions of men and women. The authors concluded that cultural factors exerted little, if any, influence on moral judgments, suggesting that the significant factor was gender-specific differences in neural organization. Functional neuroimaging studies concur with this view. For example, in a study on the cerebral correlates of judgments of procedural justice, the overall volume of cerebral activations in women were asymmetrical (total volume of activations = 7,449 mm3) with a leftward preponderance (left hemisphere activations exceeding right hemisphere activations = 1,698 mm3); activations in men were also asymmetric (total volume of activations = 10,082 mm3), but with a clear rightward preponderance (right hemisphere activations exceeding left hemisphere activations = 5,334 mm3); qualitatively similar results were obtained for judgments of distributive justice (Dulebohn et al., 2016). Recently, the ingenious application of neuroimaging methods to criminal cases with focal brain damage collected from the literature has been done with remarkable success (Darby et al., 2018). In this study, Darby et al. did not investigate if the neural networks that they found to underpin criminal behavior differed between men and women or between the cerebral hemispheres.

To test the gender/laterality interaction in acquired sociopathy we searched the literature for clinically-defined cases in which an enduring antisocial change in personality had been caused by a circumscribed, non-degenerative, brain lesion. Our main goals were to investigate (i) whether unilateral hemispheric lesions are sufficient to cause acquired sociopathy, and (ii) whether gender and lesion laterality interact to modulate the final emergence of acquired sociopathy.

An extensive literature search was conducted using the electronic databases PubMed, ISI Web of Science, and PsycInfo to identify articles published until April 2018. We used the following search terms in title, abstract or keywords: (“sociopath*” or “psychopathy” or “acquired” or “frontal lobe” or “damag*” or “injur*”) and (“imaging” or “magnetic resonance imaging” or “computed tomography” or “positron emission tomography” or “brain”). Additional papers were retrieved by checking the literature cited in the articles identified by the electronic database search as well as from the authors' personal archives. We retained all single cases or case series of previously normal children, adolescents or adults who developed a persistent antisocial change in personality following an injury of the frontal lobes with or without extension into the insula, temporal pole, and neighboring subcortical regions. The reason for extending the anatomical boundaries beyond the frontal lobes is the fact that patients with sole or predominantly temporopolar injury may also present severe antisocial personality changes (Miller et al., 1999). Note that the cases included in the present survey were selected solely on the basis of the behavioral criterion of persistent antisocial changes in personality, not on anatomical criteria such as lesion location or type. By definition, cases of developmental psychopathy fell outside the scope of the present review.

For the purposes of the present study, sociopathy was operationally defined as (a) a chronic, recurrent and pervasive pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), which (b) broadly overlaps Factor 2, but not necessarily Factor 1, of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist (Hart et al., 1995). As extensively discussed elsewhere, virtually all individuals with a diagnosis of psychopathy meet a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, or sociopathy, but the converse is not necessarily true (Lykken, 2018). However, no attempt was made in this review to differentiate sociopathy from psychopathy sensu stricto because only recently have researchers begun to differentiate acquired from developmental psychopathy (Moll et al., 2003; Mitchell et al., 2006a). With a few notable exceptions (Karpman, 1947), the earlier authors used the terms sociopathy and psychopathy interchangeably, thus overlooking the essential personality traits that distinguish psychopathy from the sociopathic behavior of other neuropsychiatric disorders (Koenigs and Tranel, 2006). We were also careful to exclude patients with antisocial changes in personality secondary to a mood disorder (Thorneloe and Crews, 1981; Bakchine et al., 1989; Tyrer and Brittlebank, 1993) and dementia (Mendez et al., 2011). In the absence of formal measures of intelligence, evidence that overt dementia or mental retardation were not part of the clinical picture were obtained from the report, otherwise the case was excluded from further analysis. A history of seizures or loss of consciousness were not a reason for exclusion, but patients with delusions, hallucinations, or both (Malloy and Richardson, 1994; Harrington et al., 1997) as well as cases with solely deep subcortical (e.g., Richfield et al., 1987; Mendez et al., 1989), or brainstem (e.g., Omar et al., 2007) lesions were excluded. Cases of sociopathy following psychosurgery were allowed in if they met the preceding criteria. Only cases in which a causal nexus between the cerebral damage and acquired sociopathy could be inferred were selected. A causal nexus was primarily provided by evidence of (i) a normal premorbid personality, and (ii) a temporal relationship between the cerebral injury and the advent of the antisocial personality change (Vann, 1972). For our purposes, “normal” was operationally defined as the capacity to be productive in the chief domains of social and interpersonal life, especially in those niches represented by family, parental/marital, school/work, and extrafamilial life (Endicott et al., 1976). Due to the considerable interindividual variation in cytoarchitectonics (Zilles and Amunts, 2012) and the less than optimal neuroanatomical accuracy of several reports prior to the 1980's, no attempt was made at this time to chart the lesions on standard cytoarchitectonic maps; for similar reasons, we did not attempt to infer the topography of the cerebral lesions based on cranial landmarks as was usual before the advent of modern neuroimaging (e.g., Jarvie, 1954). In view of the fragmentary and heterogeneous nature of the available material, no attempt was made either to sort the personality changes into subordinate domains (Barrash et al., 2018) or to perform a formal meta-analysis. Finally, we accepted as valid four cases of vmPFC dysplasia (Table 1: cases U-8 and U-10; Table 2: cases B-32 and B-47) and one case of orbital pachygyria (Table 2: case B-15). Although not strictly “acquired”, we retained these cases because the lesions in each were circumscribed to frontotemporal regions known to produce acquired sociopathy in typical cases. A similar line of reasoning has been followed by other authors (Trebuchon et al., 2013).

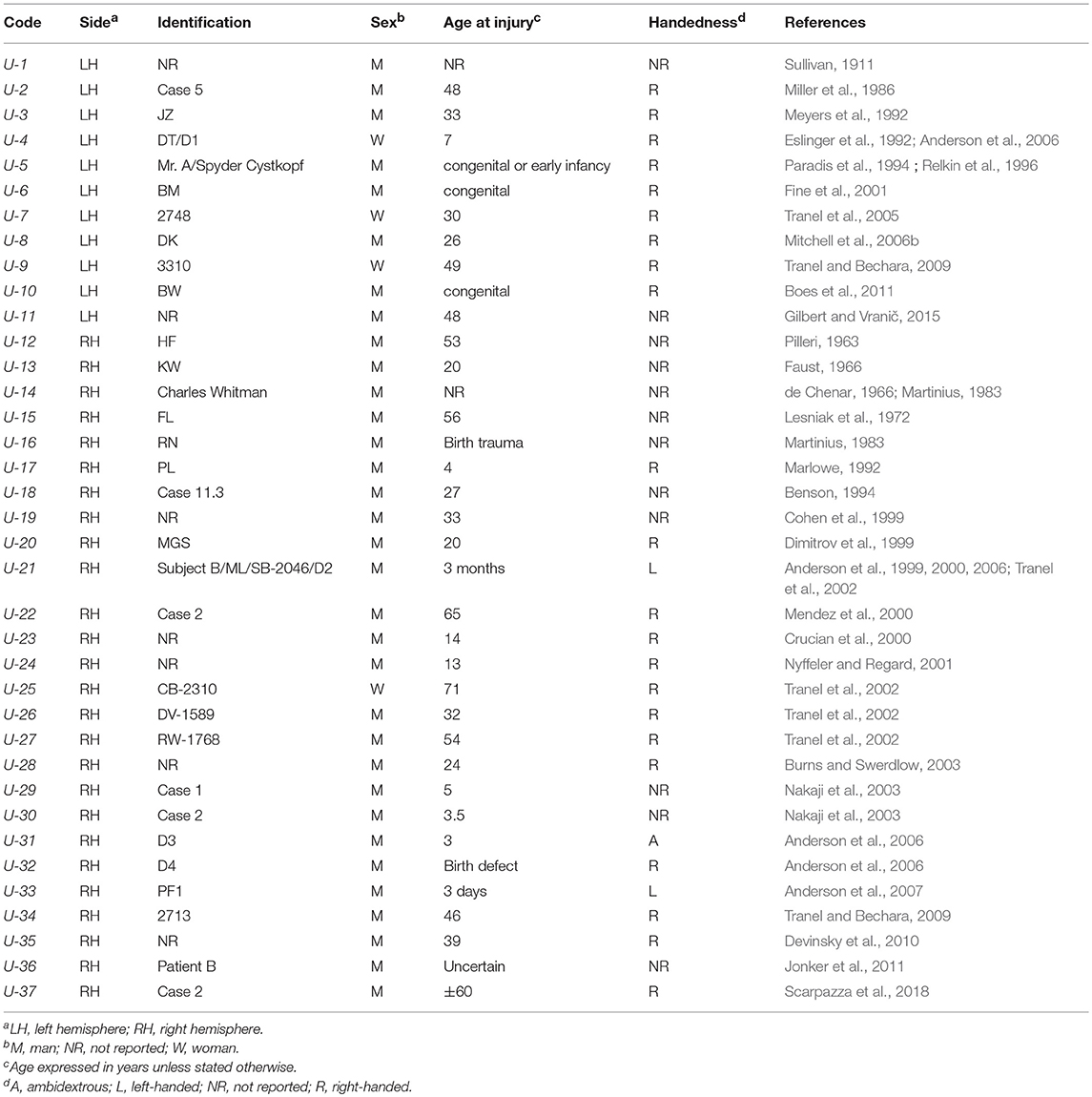

Table 1. Acquired sociopathy due to Unilateral (U) hemispheric damage (mania, mental retardation, and dementia excluded).

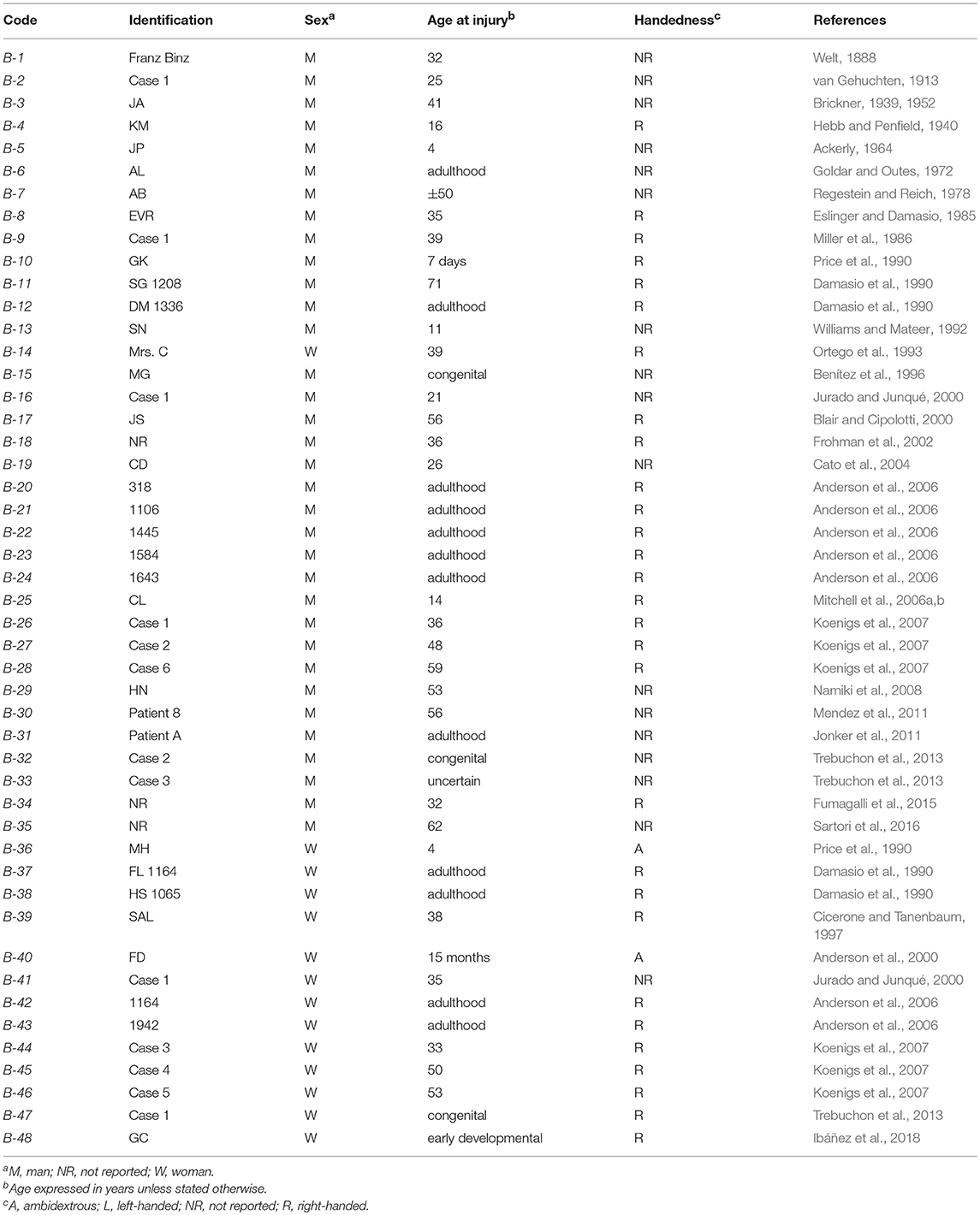

Table 2. Acquired sociopathy due to Bilateral (B) hemispheric damage (mania, mental retardation, and dementia excluded).

Because most variables of interest were categorical, they were analyzed with the χ2 and related statistics. A significance threshold of 0.05, two-tailed, was set for all tests. Statistical power and effect sizes were computed with Cramér's V and classified as small (0.10), medium (0.30) or large (0.50) following Cohen's guidelines (Cohen, 1992).

Tables 1–4 present the main results of the literature survey. Duplicate cases are also indicated in the tables. The main features leading to a diagnosis of acquired sociopathy in each case are presented in Tables 3 and 4 for the unilateral and bilateral cases, respectively. Readers may thus judge for themselves the appropriateness of the present analysis.

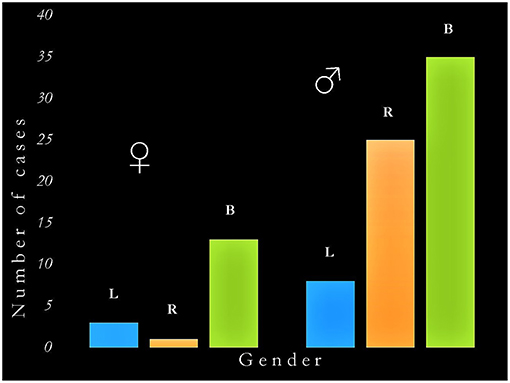

The main findings of this survey are presented in Table 5 and in Figure 1. There were 37 cases of acquired sociopathy due to unilateral hemispheric damage and 48 cases due to bilateral hemispheric damage; therefore, unilateral lesions leading to sociopathy were almost as frequent as bilateral lesions (binomial test: p = 0.27). There were more men than women in both the uni and the bilateral groups (binomial tests: p < 0.0001), as there were more cases with unilateral right hemisphere damage in the uni and the bilateral groups (binomial tests: p < 0.02). Information on handedness was available for 55 cases, 51 of which were right-handed, two were left-handed, and two were ambidextrous. The age of patients at the time of injury ranged from birth to 71 years (x = 28.8 ± 21.7 years), no statistically significant difference on age at injury being noted between men and women in either the uni or the bilateral groups (Mann-Whitney: U = 505, p > 0.37).

Figure 1. Graphic representation of the interaction between gender and hemispheric side of damage in acquired sociopathy. The critical determinants of acquired sociopathy are (a) being male, and (b) damage to the right hemisphere (either unilateral or as part of bilateral lesions). B, bilateral damage; L, left hemisphere damage; R, right hemisphere damage; ♂, men; ♀, women.

There was a significant correlation between gender and the uni/bilaterality of brain damage (χ2 = 6.1, df = 1, p < 0.04; Cramér's V = 0.23) as well as between gender and unilateral lesions (χ2 = 4.4, df = 1, p < 0.04) corresponding to medium effect sizes (Cramér's V = 0.35). When only men were considered, the number of cases with uni (N = 37) and bilateral (N = 34) damage did not significantly differ (χ2 = 0.13, df = 1, p > 0.72); however, the number of men with a left hemisphere injury (N = 8) was significantly lower than those with an injury of the right (N = 25) or of both (N = 34) hemispheres (χ2 = 16.4, df = 2, p < 0.0001). When only women were considered, the number of cases with bilateral damage (N = 14) was significantly higher than those with a unilateral (N = 4) lesion (χ2 = 5.6, df = 1, p < 0.02); moreover, there were more cases with bilateral than either with unilateral right (N = 1) or left (N = 3) damage (χ2 = 16.3, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Ordinal regression revealed a significant association between acquired sociopathy and right hemisphere damage in men (OR = 10.3, p < 0.02). No equivalent associations were seen for women regardless of the laterality or bilaterality of damage (OR = 1.1, p > 0.90). The inclusion of handedness and age at which the brain injury was acquired in the regression model did not qualitatively change these results.

Finally, it may seem surprising not to find the case of Phineas Gage in the Tables. The reason for this is the dispute regarding the bilaterality (Damasio et al., 1994) or the unilaterality (Ratiu and Talos, 2004) of Gage's injury, which remains speculative because no postmortem exam was performed on Gage's brain. In addition, the details of Gage's case have often been embellished, distorted, or inferred beyond what is justified by the first-hand reports by Harlow and Bigelow (Macmillan, 2008).

The present survey came to some intriguing and unexpected results which may be thus summarized: (i) unilateral lesions are almost as frequent as bilateral lesions leading to acquired sociopathy; (ii) there are relatively few well-documented cases of acquired sociopathy in the medical literature, especially when we consider the length of the historical record; (iii) acquired sociopathy was significantly more common in men after an injury of the right or of both cerebral hemispheres; (iv) in most women who developed acquired sociopathy the lesions affected both cerebral hemispheres; and (v) men outnumbered women in both the unilateral and bilateral groups.

As stated in the Material and Methods section, the point of departure of the present analyses was clinical, not anatomical. The logical next step is to follow the reverse course of case selection beginning with the collection of cases with lesions of the right and the left frontotemporoinsular cortices, and investigate their clinical manifestations according to gender and lesion laterality. These two approaches are not comparable, and the anatomical approach may lead to quite different conclusions.

Owing to the limitations of the material herein surveyed, the present review should be considered cautiously. These limitations have to do with missing data in several reports, including the handedness of participants, the age at which the brain damage occurred, and when the manifestations of sociopathy were first noted; however, the most important gap is the fact that the anatomical descriptions are often too vague to allow in-depth clinicoanatomical deductions.

Besides the aforementioned gaps in knowledge, the present survey reveals that the number of well-documented cases of acquired sociopathy is surprisingly small, especially in view of the popularity that it has long enjoyed both among scholars and in the lay media (de Oliveira-Souza and Moll, 2019). This partly unfounded popularity has given breadth to the assumption that we know more about the cerebral underpinnings of acquired sociopathy than we actually do. Indeed, one of the main purposes of the present work was to gather these gaps in knowledge in a single communication. There is a pressing need to revive the clinicoanatomical tradition of studying single cases or case series with modern behavioral and neuroimaging methods. Despite its limitations, the postmortem exam remains the gold standard for increasing our knowledge of neural structures and pathways (Goetz, 2010). This assertion is bolstered by the exemplary studies that make up the body of the present survey (e.g., Dimitrov et al., 1999; Cato et al., 2004; Eslinger et al., 2004; Anderson et al., 2007).

Acquired sociopathy was significantly more common in men after an injury of the right or of both cerebral hemispheres. A corollary of this finding is that the left hemisphere in men who develop acquired sociopathy due to bi-hemispheric injuries probably plays a minor, if any, role in the genesis of the antisocial personality changes, a finding that is in line with Tranel et al. observations (see Introduction). In most women with acquired sociopathy, in contrast, injuries of both hemispheres were significantly more common than lesions of either hemisphere alone, a finding that is partially in line with Tranel et al. observations.

Despite the wealth of research on cerebral asymmetries and on the differences between the brains of men and women (Cahill, 2006), the neural underpinnings of the interactions between asymmetry and gender have been less studied. The gender and lateral asymmetries in acquired sociopathy revealed by the present survey provide converging evidence that the neural organization of sociomoral conduct in women has a more symmetrical organization in the cerebral hemispheres than in men, in whom the right hemisphere seems to play a dominant role. This conclusion, however provisional, is supported by the broader issue of gender differences in sociopathy (Moffitt et al., 2004) and by the cerebral organization of moral cognition and behavior in men and women (Dulebohn et al., 2016).

In most of the cases herein reviewed, the lesions were in a position to either directly destroy or impinge upon the uncinate fascicle (UF), the ventral amygdalofugal pathway, and the medial forebrain bundle. The UF is a hook-shaped association tract that interconnects the anterior temporal lobe, the insula, and the orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortices (Ebeling and von Cramon, 1992). It is composed of five smaller, partially overlapping, fascicles with different origins, trajectories, and terminations (Hau et al., 2017); a remarkable rightward asymmetry of the UF, both in volume and number of fibers, has consistently been noted by researchers (Highley et al., 2002). The UF integrates a collection of cortical areas which play an essential role in the regulation of higher-order social behavior, as shown in extreme form by the human Klüver-Bucy syndrome (Hayman et al., 1998). This functional unity is also profusely interconnected with the amygdala and the basal forebrain bidirectional fiber systems that are responsible for the basic drives and the regulation of the internal milieu of the organism (Livingston and Escobar, 1971), thus allowing the reciprocal interaction between complex social and fundamental organic behaviors (Mogenson and Yang, 1991). For the most part, the frontotemporoinsular cortices fall within the projection fields of the UF, the ventral amygdalofugal pathway (Kamali et al., 2016), the stria terminalis (Baydin et al., 2017), and the inferomedial leaflet of the medial forebrain bundle (Edlow et al., 2016). These tracts funnel through the temporal stem toward the temporal pole and amygdala, a critical region of the white matter in which relatively small injuries may produce major disturbances in moral conduct and social behavior (Kling et al., 1993). The right UF has been shown to be reduced in individuals with psychopathy (Sobhani et al., 2015), but the integrity of other white matter pathways may be disrupted as well (Waller et al., 2017). Thus, there are good reasons to suppose that the UF and neighboring tracts also play a critical role in the manifestations of acquired sociopathy (van Horn et al., 2012).

When we began this project, we had no a priori expectations regarding the relative prevalence of men to women in acquired sociopathy. Neither do we now have a definitive explanation for the higher male-to-female preponderance either in the unilateral (7.2:1) or bilateral (2.3:1) groups. The most parsimonious explanation is provided by epidemiological studies, which indicate that the male preponderance of the present survey is a particular instance of a general phenomenon shared by common neurological illnesses such as stroke, head injury, and epilepsy (Braun et al., 2002). For example, men are three times more likely to suffer a traumatic brain injury than women (Gardner and Zafonte, 2018). The unequal proportion of genders in the literature should not divert us from the possibility that, as far as can be judged from the available cases, the occurrence of acquired sociopathy in injuries of the cerebral hemispheres seems to be strongly modulated by gender and lesion laterality. This hypothesis concurs with a growing body of evidence indicating that gender differences in various aspects of normal social and antisocial behavior mainly reflect neurobiological mechanisms rather than cultural modeling.

Over a century ago, van Gehuchten (1913) and Agostini (1914) entertained the possibility that the laterality of a lesion in the frontal lobes played a critical role in the determination of acquired sociopathy. At that time, and for the ensuing seven decades, the means to test this possibility relied on postmortem exams, which usually reflect the final stages of the pathological process and often lay distant in time from the clinical and behavioral manifestations of interest. Such drawbacks can now be circumvented by the use of current neuroimaging techniques in the assessment of social cognition (Duclos et al., 2018). The differential neural underpinnings of social cognition between men and women should systematically be considered in the design of experiments on social cognition and behavior. They may be especially valuable to neurosurgeons, and to functional neurosurgeons in particular, in the planning of interventions for tumor resections as well as the choice of the best targets for therapeutic neuromodulation (Darby and Pascual-Leone, 2017). A more precise understanding of the neurobiology of acquired and developmental sociopathy may be closer than ever before.

RdO-S, TP, JG, and JM contributed to the conception and design of the study. RdO-S and TP collected and organized the database. RdO-S performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

RdO-S is indebted to Professor Omar da Rosa Santos (Gaffrée e Guinle University Hospital) for his unwavering institutional support, and to Mr. José Ricardo Pinheiro and Mr. Jorge Baçal (in memoriam) of the Library of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, Rio de Janeiro, for the retrieval of the rare books and articles.

Ackerly, S. S. (1964). “A case of paranatal bilateral frontal lobe defect observed for thirty years,” in The Frontal Granular Cortex and Behavior, eds J. M. Warren and K. Akert (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill), 192–218.

Agostini, C. (1914). Tumori dei lobi frontali e criminalità. Archivio di Antropologia Criminale Psichiatria Medicina Legale e Scienze Affini 35, 544–558.

Alpers, B. J. (1937). Relation of the hypothalamus to disorders of personality: a case report. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 38, 291–303. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1937.02260200063005

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edn., Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, S. W., Aksan, N., Kochanska, G., Damasio, H., Wisnowski, J., and Afifi, A. (2007). The earliest behavioral expression of focal damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cortex 43, 806–816. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70508-2

Anderson, S. W., Barrash, J., Bechara, A., and Tranel, D. (2006). Impairments of emotion and real-world complex behavior following childhood- or adult-onset damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 12, 224–235. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060346

Anderson, S. W., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., and Damasio, A. R. (1999). Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 1032–1037.

Anderson, S. W., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., and Damasio, A. R. (2000). Long-term sequelae of prefrontal cortex damage acquired in early childhood. Dev. Neuropsychol. 18, 281–296. doi: 10.1207/S1532694202Anderson

Angelini, L., Mazzucchi, A., Picciotto, F., Nardocci, N., and Broggi, G. (1980). Focal lesion of the right cingulum: a case report in a child. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 43, 355–357.

Bakchine, S., Lacomblez, L., Benoit, N., Parisot, D, Chain, F., and Lhermitte, F. (1989). Manic-like state after bilateral orbitofrontal and right temporoparietal injury efficacy of clonidine. Neurology 39, 777–891. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.6.777

Barrash, J., Stuss, D. T., Aksan, N., Anderson, S. W., Jones, R. D., Manzel, K., et al. (2018). “Frontal lobe syndrome”? Subtypes of acquired personality disturbances in patients with focal brain damage. Cortex 106, 65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2018.05.007

Barrash, J., Tranel, D., and Anderson, S. W. (2000). Acquired personality disturbances associated with bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal region. Dev. Neuropsychol. 18, 355–381. doi: 10.1207/S1532694205Barrash

Baydin, S., Gungor, A., Tanriover, N., Baran, O., Middlebrooks, E. H., and Rhoton, A. L. (2017). Fiber tracts of the medial and inferior surfaces of the cerebrum. World Neurosurg. 98, 34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.05.016

Benítez, I., Montero, L. O., and Affanni, J. M. (1996). Alteraciones de la corteza orbitaria anterior en un sujeto con grave comportamiento antisocial. Alcmeon 5: 117.

Blair, R. J. R., and Cipolotti, L. (2000). Impaired social response reversal: a case of “acquired sociopathy. Brain 123, 1122–1141. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1122

Boes, A. D., Grafft, A. H., Joshi, C., Chuang, N. A., Nopoulos, P., and Anderson, S. W. (2011). Behavioral effects of congenital ventromedial prefrontal cortex malformation. BMC Neurol. 11:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-151

Braun, C. M. J., Montour-Proulx, I., Daigneault, S., Rouleau, I., Kuehn, I., Piskopos, M., et al. (2002). Prevalence, and intellectual outcome of unilateral focal cortical brain damage as a function of age, gender and etiology. Behav. Neurol. 12, 1–12.

Brickner, R. M. (1939). Bilateral frontal lobectomy: Follow-up report of a case. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 41, 580–583. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1939.02270150154014

Brickner, R. M. (1952). Brain of patient “A” after bilateral frontal lobectomy; status of frontal lobe problem. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 68, 293–313.

Burns, J. M., and Swerdlow, R. H. (2003). Right orbitofrontal tumor with pedophilia and constructional apraxia sign. Arch. Neurol. 60, 437–440. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.437

Cahill, L. (2006). Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 477–484. doi: 10.1038/nrn1909

Cato, M. A., Delis, D. C., Abildskov, T. J., and Bigler, E. (2004). Assessing the elusive cognitive deficits associated with ventromedial prefrontal damage: a case of a modern-day Phineas Gage. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 10, 453–465. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704103123

Choy, O., Raine, A., Venables, P. H., and Farrington, D. P. (2017). Explaining the gender gap in crime: the role of heart rate. Criminology 55, 465–487. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12138

Cicerone, K. D., and Tanenbaum, L. N. (1997). Disturbance of social cognition after traumatic orbitofrontal brain injury. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 12, 173–188. doi: 10.1093/arclin/12.2.173

Cohen, L., Angladette, L., Benoit, N., and Pierrot-Deseilligny, C. (1999). A man who borrowed cars. Lancet 353, 34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09047-3

Crucian, G. P., Fennell, E. B., Maria, B. L., and Quisling, R. G. (2000). Neuropsychological sequelæ of a pituitary germinoma: a case study. Neurocase 6, 65–72. doi: 10.1080/13554790008402759

Damasio, A. R., Tranel, D., and Damasio, H. (1990). Individuals with sociopathic behavior caused by frontal damage fail to respond autonomically to social stimuli. Behav. Brain Res. 41, 81–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90144-4

Damasio, H., Grabowski, T., Frank, R., Galaburda, A. M., and Damasio, A. R. (1994). The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science 264, 1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.8178168

Darby, R. R., Horn, A., Cushman, F., and Fox, M. D. (2018). Lesion network localization of criminal behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 601–606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706587115

Darby, R. R., and Pascual-Leone, A. (2017). Moral enhancement using non-invasive brain stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11:77. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00077

de Chenar, C. (1966). Report to the Governor. Medical aspects. Charles Joseph Whitman catastrophe. Austin, TX.

de Oliveira-Souza, R., and Moll, J. (2019). “Moral conduct and social behavior,” in Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Third Series: The Frontal Lobes, eds M. D'Esposito and J. Grafman (New York, NY: Elsevier).

Devinsky, J., Sacks, O., and Devisnky, O. (2010). Klüver-Bucy syndrome, hypersexuality and the law. Neurocase 16, 140–145. doi: 10.1080/13554790903329182

Dimitrov, M., Phipps, M., Zahn, T. P., and Grafman, J. (1999). A thoroughly modern Gage. Neurocase 5, 345–354. doi: 10.1080/13554799908411987

Duclos, H., Desgranges, B., Eustache, F., and Laisney, M. (2018). Impairment of social cognition in neurological diseases. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 174, 190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2018.03.003

Dulebohn, J. H., Davison, R. B., Lee, S. A., Conlon, D. E., McNamara, G., and Sarinopoulos, I. C. (2016). Gender differences in justice evaluations: evidence from fMRI. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 151–170. doi: 10.1037/apl0000048

Ebeling, U., and von Cramon, D. (1992). Topography of the uncinate fascicle and adjacent temporal fiber tracts. Acta Neurochir. Wien, 115, 143–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01406373

Edlow, B. L., McNab, J. A., Witzel, T., and Kinney, H. C. (2016). The structural connectome of the human central homeostatic network. Brain Connect. 6, 187–200. doi: 10.1089/brain.2015.0378

Endicott, J., Spitzer, R. L., Fleiss, J. L., and Cohen, J. (1976). The global assessment scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbances. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 33, 766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012

Eslinger, P. J., and Biddle, K. R. (2000). Adolescent neuropsychological development after early right prefrontal cortex damage. Dev. Neuropsychol. 18, 297–329. doi: 10.1207/S1532694203Eslinger

Eslinger, P. J., Biddle, K. R., Pennington, B., and Page, R. B. (1999). Cognitive and behavioral development up to 4 years after early right frontal lobe lesion. Dev. Neuropsychol. 75, 157–191. doi: 10.1080/87565649909540744

Eslinger, P. J., and Damasio, A. R. (1985). Severe disturbance of higher cognition after bilateral frontal lobe ablation: patient, E. V. R. Neurology 35, 1731–1741. doi: 10.1212/WNL.35.12.1731

Eslinger, P. J., Flaherty-Craig, C. V., and Benton, A. L. (2004). Developmental outcomes after early prefrontal cortex damage. Brain Cogn. 55, 84–103 doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00281-1

Eslinger, P. J., Grattan, L. M., Damasio, H., and Damasio, A. R. (1992). Developmental consequences of childhood frontal lobe damage. Arch. Neurol. 49, 764–769. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530310112021

Faust, C. I. (1966). Different psychological consequences due to superior frontal and orbito-basal lesions. Int. J. Neurol. 5, 410–421.

Fine, C., Lumsden, J., and Blair, R. J. R. (2001). Dissociation between ‘theory of mind' and executive functions in a patient with early left amygdala damage. Brain 124, 287–298. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.287

Flynn, F., Cummings, J. L., and Tomiyasu, U. (1988). Altered behavior associated with damage to the ventromedial hypothalamus: a distinctive syndrome. Behav. Neurol. 1, 49–58. doi: 10.1155/1988/291847

Frohman, E. M., Frohman, T. C., and Moreault, A. M. (2002). Acquired sexual paraphilia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 59, 1006–1010. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.6.1006

Fumagalli, M., Ferrucci, R., Mameli, F., Marceglia, S., Mrakic-Sposta, S., Zago, S., et al. (2010). Gender-related differences in moral judgments. Cogn. Process. 11, 219–226. doi: 10.1007/s10339-009-0335-2

Fumagalli, M., Pravettoni, G., and Priori, A. (2015). Pedophilia 30 years after a traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Sci. 36, 481–482. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1915-1

Gardner, A. J., and Zafonte, R. (2018). “Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury,” in Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 138 third series: Neuroepidemiology, eds C. Rosano, M. A. Ikram, and M. Ganguli (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 207–223.

Ghosh, V. E., Moscovitch, M., Colella, B. M., and Gilboa, A. (2014). Schema representation in patients with ventromedial PFC lesions. J. Neurosci. 34, 12057–12070. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0740-14.2014

Gilbert, F., and Vranič, A. (2015). Paedophilia, invasive brain surgery, and punishment. Bioeth. Inq. 12, 521–526. doi: 10.1007/s11673-015-9647-3

Goetz, C. G. (2010). “Jean-Martin Charcot and the anatomo-clinical method of neurology,” in: Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 96 (third series): History of Neurology, eds S. Finger, F. Boller, and K. L. Tyler (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 203–212.

Goldar, J. C., and Outes, D. L. (1972). Fisiopatología de la desinhibición instintiva. Acta Psiq. Psicol. Amer. Lat. 18, 177–185.

Gorman, D. G., and Cummings, J. L. (1992). Hypersexuality following septal injury. Arch. Neurol. 49, 308–310. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530270128029

Harrington, C., Salloway, S., and Malloy, P. (1997). Dramatic neurobehavioral disorder in two cases following bilateral anteromedial frontal lobe injury: delayed psychosis and marked change in personality. Neurocase 3, 137–149. doi: 10.1080/13554799708404047

Hart, S. D., Cox, D. N., and Hare, R. D. (1995). The Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems.

Hau, J., Sarubbo, S., Houde, J. C., Corsini, F., Girard, G., Deledalle, C., et al. (2017). Revisiting the human uncinate fasciculus, its subcomponents and asymmetries with stem-based tractography and microdissection validation. Brain Struct. Funct. 222, 1645–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1298-6

Hayman, L. A., Rexer, J. L., Pavol, M. A., Strite, D., and Meyers, C. A. (1998). Klüver-Bucy syndrome after bilateral selective damage of amygdala and its cortical connections. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 10, 354–358. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.3.354

Hebb, D. O., and Penfield, W. (1940). Human behavior after extensive bilateral removal from the frontal lobes. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 44, 421–428. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1940.02280080181011

Highley, J. R., Walker, M. A., Esiri, M. M., Crow, T. J., and Harrison, P. J. (2002). Asymmetry of the uncinate fasciculus: a post-mortem study of normal subjects and patients with schizophrenia. Cereb. Cortex 12, 1218–1224. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.11.1218

Ibáñez, A., Zimerman, M., Sedeño, L., Lori, N., Rapacioli, M., Cardona, J. F., et al. (2018). Early bilateral and massive compromise of the frontal lobes. Neuroimage Clin. 18, 543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.02.026

Jarvie, H. F. (1954). Frontal lobe wounds causing disinhibition. A study of six cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 17, 14–32. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.17.1.14

Jonker, C., Matthaei, I., Schouws, S. N. T. M., and Sickens, E. P. K. (2011). Twee verdachten met hersenletsel en crimineel gedrag. De bijdrage van de neuroloog aan forensisch psychiatrische diagnostiek. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 53, 181–187.

Jurado, M. A., and Junqué, C. (2000). Conducta delictiva tras lesiones prefrontales orbitales. Estúdio de dos casos. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 28, 337–341.

Kamali, A., Sair, H. I., Blitz, A. M., Riascos, R. F., Mirbagheri, S., Keser, Z., et al. (2016). Revealing the ventral amygdalofugal pathway of the human limbic system using high spatial resolution diffusion tensor tractography. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 3561–3569. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1119-3

Karpman, B. (1947). Moral agenesis. Towards the delimitation of the problem of psychopathic states. Psychiatr. Q. 21, 361–398. doi: 10.1007/BF01562009

King, M. L., Manzel, K., Bruss, J., and Tranel, D. (2017). Neural correlates of improvements in personality and behavior following a neurological event. Neuropsychologia. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.11.023

Kling, A. S., Tachiki, K., and Lloyd, R. (1993). Neurochemical correlates of the Klüver-Bucy syndrome by in vivo microdialysis in monkey. Behav. Brain Res. 56, 161–170. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90034-N

Koenigs, M., and Tranel, D. (2006). “Pseudopsychopathy: a perspective from cognitive neuroscience,” in The Orbitofrontal Cortex, eds D. H. Zald and S. L. Rauch (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 597–619.

Koenigs, M., Young, L., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Cushman, F., Hauser, M., et al. (2007). Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements. Nature 446, 908–911. doi: 10.1038/nature05631

Labbate, L. A., Warden, D., and Murray, G. B. (1997). Salutary change after frontal brain trauma. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 9, 27–30. doi: 10.3109/10401239709147771

Lesniak, R., Szymusik, A., and Chrzanowski, R. (1972). Multidirectional disorders of sexual drive in a case of brain tumour. Forensic Sci. 1, 333–338. doi: 10.1016/0300-9432(72)90031-3

Livingston, K. E., and Escobar, A. (1971). Anatomical bias of the limbic system concept. A proposed reorientation. Arch. Neurol. 24, 17–21. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1971.00480310045003

Lykken, D. T. (2018). “Psychopathy, sociopathy, and antisocial personality disorder. in Handbook of Psychopathy, 2nd. Edn., ed C. J. Patrick (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 22–32.

Malloy, P. F., and Richardson, E. D. (1994). The frontal lobes and content-specific delusions. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 6, 455–466. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.455

Marlowe, W. B. (1992). The impact of a right prefrontal lesion in the developing brain. Brain Cogn. 20, 205–213. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(92)90070-3

Martinius, J. (1983). Homicide of an aggressive adolescent boy with right temporal lesion: a case report. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 7, 419–422. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(83)90048-9

Mendez, M. F., Adams, N. L., and Lewandowski, K. S. (1989). Neurobehavioral changes associated with caudate lesions. Neurology 39, 349–354. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.3.349

Mendez, M. F., Chow, T., Ringman, J., Twitchell, G., and Hinkin, C. H. (2000). Pedophilia and temporal lobe disturbances. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 12, 71–76. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.1.71

Mendez, M. F., Shapira, J. S., and Saul, R. E. (2011). The spectrum of sociopathy in dementia. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 23, 132–140. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp132

Meyers, C. A., Berman, A. S., Scheibel, R. S., and Hayman, A. (1992). Acquired antisocial personality disorder associated with unilateral left orbital frontal lobe damage. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 17, 121–125.

Miller, B. L., Cummings, J. L., Mclntyre, H., Ebers, G., and Grode, M. (1986). Hypersexuality or altered sexual preference following brain injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 49, 867–873. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.8.867

Miller, B. L., Hou, C., Goldberg, M., and Mena, I. (1999). “Anterior temporal lobes: social brain,” in The Human Frontal Lobes. Functions and Disorders. eds B. L. Miller and J. L. Cummings (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 557–567.

Mitchell, D. G. V., Avny, S. B., and Blair, R. J. R. (2006a). Divergent patterns of aggressive and neurocognitive characteristics in acquired versus developmental psychopathy. Neurocase 12, 164–178. doi: 10.1080/13554790600611288

Mitchell, D. G. V., Fine, C., Richell, R. A., Newman, C., Lumsden, J., Blair, K. S., et al. (2006b). Instrumental learning and relearning in individuals with psychopathy and in patients with lesions involving the amygdala or orbitofrontal cortex. Neuropsychology 20, 280–289. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.3.280

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Rutter, N., and Silva, P. A. (2004). Sex Differences in Antisocial Behavior. Conduct Disorder, Delinquency, and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mogenson, G. J., and Yang, C. R. (1991). The contribution of basal forebrain to limbic-motor integration and the mediation of motivation to action. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 295, 267–290. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0145-6_14

Moll, J., de Oliveira-Souza, R., and Eslinger, P. J. (2003). Morals and the human brain: a working model. NeuroReport 14, 299–305. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200303030-00001

Nakaji, P., Meltzer, H. S., Singel, S. A., and Alksne, J. F. (2003). Improvement of aggressive and antisocial behavior after resection of temporal lobe tumors. Pediatrics 112, e430–e433. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e430

Namiki, C., Yamada, M., Yoshida, H., Hanakawa, T., Fukuyama, H., and Murai, T. (2008). Small orbitofrontal traumatic lesions detected by high resolution MRI in a patient with major behavioural changes. Neurocase 14, 474–479. doi: 10.1080/13554790802459494

Nichols, I. C., and Hunt, J. M. (1940). A case of partial bilateral frontal lobectomy. A psychopathological study. Am. J. Psychiatry 96, 1063–1087. doi: 10.1176/ajp.96.5.1063

Nyffeler, T., and Regard, M. (2001). Kleptomania in a patient with a right frontolimbic lesion. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. Behav. Neurol. 14, 73–76.

Omar, R., Warren, J. D., Ron, M. A., Lees, A. J., Rossor, M. N., and Kartsounis, L. D. (2007). The neuro-behavioural syndrome of brainstem disease. Neurocase 13, 452–465. doi: 10.1080/13554790802001403

Ortego, N., Miller, B. L., Itabashi, H., and Cummings, J. L. (1993). Altered sexual behavior with multiple sclerosis: a case report. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. Behav. Neurol. 6, 260–264.

Paradis, C. M., Horn, L., Lazar, R. M., and Schwartz, D. W. (1994). Brain dysfunction and violent behavior in a man with a congenital subarachnoid cyst. Hospital Commun. Psychiatry 45, 714–716. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.7.714

Pascalau, R., Stănilă, R. P., Sfrângeu, S., and Szabo, B. (2018). Anatomy of the limbic white matter tracts as revealed by fiber dissection and tractography. World Neurosurg. 113, e672–e689. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.121

Penfield, W., and Evans, J. (1935). The frontal lobes of man: a clinical study of maximum removals. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 58, 115–133. doi: 10.1093/brain/58.1.115

Pilleri, G. (1963). Über einen fall von psychopathischer persönlichkeit mit cholesteatom der orbitalgegend. Arch. Psychiatr. Nervenkr. Z. gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 204, 349–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00341606

Plaza, M., du Boullay, V., Perrault, A., Chaby, L., and Capelle, L. (2014). A case of bilateral frontal tumors without “frontal syndrome”. Neurocase 20, 671–683. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2013.826696

Poeck, K., and Pilleri, G. (1965). Release of hypersexual behavior due to lesion in the limbic system. Acta Neurol. Scand. 41, 233–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1965.tb04295.x

Price, B. H., Daffner, K. R., Stowe, R. M., and Mesulam, M-M. (1990). The comportmental learning disabilities of early frontal lobe damage. Brain 113, 1383–1393. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.5.1383

Ratiu, P., and Talos, I-F. (2004). The tale of phineas gage, digitally remastered. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:e21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm031024

Regestein, Q. R., and Reich, P. (1978). Pedophilia occurring after onset of cognitive impairment. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 166, 794–798.

Relkin, N., Plum, F., Mattis, S., Eidelberg, D., and Tranel, D. (1996). Impulsive homicide associated with an arachnoid cyst and unilateral frontotemporal cerebral dysfunction. Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 1, 172–183.

Richfield, E. K., Twyman, R., and Berent, S. (1987). Neurological syndrome following bilateral damage to the head of the caudate nuclei. Ann. Neurol. 22, 768–771. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220615

Rylander, G. (1939). Personality changes after operations on the frontal lobes. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 14 (Suppl. 20), 7–327.

Sandson, T. A., Daffner, K. R., Carvalho, P. A., and Mesulam, M. M. (1991). Frontal lobe dysfunction following infarction of the left-sided medial thalamus. Arch. Neurol. 48, 1300–1303. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530240106031

Sartori, G., Scarpazza, C., Codognotto, S., and Pietrini, P. (2016). An unusual case of acquired pedophilic behavior following compression of orbitofrontal cortex and hypothalamus by a clivus chordoma. J. Neurol. 263, 1454–1455. doi: 10.1007/s004150168143-y

Scarpazza, C., Pennati, A., and Sartori, G. (2018). Mental insanity assessment of -pedophilia: the importance of the trans-disciplinary approach. Reflections on two cases. Front. Neurosci. 12:335. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00335

Sobhani, M., Baker, L., Martins, B., Tuvblad, C., and Aziz-Zadeh, L. (2015). Psychopathic traits modulate microstructural integrity of right uncinate fasciculus in a community population. Neuroimage 8, 32–38 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.03.012

Storey, P. B. (1970). Brain damage and personality change after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br. J. Psychiatry 117, 129–142. doi: 10.1192/S0007125000192815

Sullivan, W. C. (1911). Note on two cases of tumour of prefrontal lobe in criminals; with remarks on disorders of social conduct in cases of cerebral tumour. Lancet 178, 1004–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)69483-2

Thorneloe, W. F., and Crews, E. L. (1981). Manic depressive illness concomitant with antisocial personality disorder: six case reports and review of the literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 42, 5–9.

Tow, P. M., and Whitty, C. W. M. (1953). Personality changes after operations on the cingulate gyrus in man. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 16, 186–193. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.16.3.186

Tranel, D., and Bechara, A. (2009). Sex-related functional asymmetry of the amygdala: preliminary evidence using a case-matched lesion approach. Neurocase 15, 217–234. doi: 10.1080/13554790902775492

Tranel, D., and Bechara, A. (2010). Sex-related functional asymmetry in the limbic brain. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rev. 35, 340–341. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.122

Tranel, D., Bechara, A., and Denburg, N. L. (2002). Asymmetric functional roles of right and left ventromedial prefrontal cortices in social conduct, decision-making, and emotional processing. Cortex 38, 589–612. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70024-8

Tranel, D., Damasio, H., Denburg, N. L., and Bechara, A. (2005). Does gender play a role in functional asymmetry of ventromedial prefrontal cortex? Brain 128, 2872–2881. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh643

Tranel, D., and Hyman, B. T. (1990). Neuropsychological correlates of bilateral amyg dala damage. Arch. Neurol. 47, 349–355. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530030131029

Trebuchon, A., Bartolomei, F., McGonigal, A., Laguitton, V., and Chauvel, P. (2013). Reversible antisocial behavior in ventromedial prefrontal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 29, 367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.08.007

Tyrer, S. P., and Brittlebank, A. D. (1993). Misdiagnosis of bipolar affective disorder as personality disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 38, 587–589. doi: 10.1177/070674379303800903

van Gehuchten, A. (1913). Deux cas de lésion grave du lobe frontal: Tumeurs volumineuse du lobe frontal droit et abcès volumineux du lobe frontal gauche par anomalie des sinus. Bull. l'Acad. R. Méd. Belgique 27, 536–544.

van Horn, J. D., Irimia, A., Torgerson, C. M., Chambers, M. C., Kikinis, R., and Toga, A. W. (2012). Mapping connectivity damage in the case of Phineas Gage. PLoS ONE 7:e37454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037454

Vann, D. (1972). Interval between sustaining brain damage and development of personality change. Med. J. Aust. 2, 1507–1508.

Waller, R., Hailey, L, Dotterer, H. K., Murray, L., Maxwell, A. M., and Hyde, L. W. (2017). White-matter tract abnormalities and antisocial behavior: a systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies across development. Neuroimage 14, 201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.014

Welt, L. (1888). Ueber charakterveränderungen des menschen infolge von läsionen des stirnhirns. Deutsch. Arch. Klin. Med. 42, 339–390.

Keywords: acquired sociopathy, frontal lobe syndromes, hemispheric asymmetry, morality, orbitofrontal syndrome, psychopathy, ventromedial prefrontal cortex

Citation: de Oliveira-Souza R, Paranhos T, Moll J and Grafman J (2019) Gender and Hemispheric Asymmetries in Acquired Sociopathy. Front. Psychol. 10:346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00346

Received: 09 July 2018; Accepted: 04 February 2019;

Published: 19 March 2019.

Edited by:

Mattie Tops, VU University Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Nicola Canessa, Istituto Universitario di Studi Superiori di Pavia (IUSS), ItalyCopyright © 2019 de Oliveira-Souza, Paranhos, Moll and Grafman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ricardo de Oliveira-Souza, cmRlb2xpdmVpcmFAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.