- 1Department of Psychology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

- 2Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine Research Group, School of Psychology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

- 3Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Introduction

The lack of replication of key effects in psychology has highlighted some fundamental problems with reporting of research findings and methods used (Asendorpf et al., 2013; Open Science Collaboration, 2015). Problems with replication have been attributed to sources of bias such as questionable research practices like HARK-ing (Kerr, 1998) or p-hacking (Simmons et al., 2011). Another potential source of bias is lack of precision in the conduct and methods used in psychological research, which likely introduces systematic error into data collected with the potential to affect results. A related issue is lack of accuracy in reporting study methods and findings. There is, therefore, increased recognition in the importance of transparency when reporting study outcomes to enable the scientific community to make fair, unbiased appraisals of the implications and worthiness of study findings. Lack of transparency hinders scientific progress as it may lead to erroneous conclusions regarding the implications of research findings, and may impede comparison and synthesis of findings across studies. As a result, researchers have become interested in research quality and the need for comprehensive, transparent reporting of findings (Asendorpf et al., 2013). This has resulted in calls for appropriate reporting standards and means to assess study quality (Cooper, 2011; Greenhalgh and Brown, 2017). In the present article we review the issue of study quality in psychology, and argue for valid and reliable means to assess study quality in psychology. Specifically, we contend that appropriate assessment checklists be developed for survey studies, given the prominence of surveys as a research method in the field.

Importance of Assessing Study Quality

Study quality is the degree to which researchers conducting the study have taken appropriate steps to maximize the validity of, and, minimize bias in, their findings (Khan et al., 2011). Studies of lower quality are more likely to have limitations and deficits which introduce error variance to data that can bias results and their interpretation. Studies of higher quality are less likely to include these errors, or more likely to provide clear and transparent reporting of errors and limitations, resulting in greater precision and validity of findings and their interpretation (Oxman and Guyatt, 1991; Moher et al., 1998). Study quality assessment came to prominence from the evidence-based medicine approach, which focussed on identifying, appraising, and synthesizing medical research (Guyatt et al., 1992). The ideas have since been applied to other disciplines, including the behavioral and social sciences (Michie et al., 2005; APA, 2006b). Assessment of study quality has several advantages, such as identifying the strengths and weaknesses in evidence, providing recommendations for interventions, policy, and practice, and improving research and publication standards (Greenhalgh, 2014; Greenhalgh and Brown, 2017). Moreover, in the context of evidence syntheses, study quality can be used to screen studies for inclusion, identify sources of bias in the results, and measure the impact of study quality on the results through subgroup and sensitivity analyses (Johnson et al., 2014).

Study quality assessment is typically performed with the use of a checklist or “tool,” containing a series of quality-related items. Recent reviews have identified a large number of tools (N = 193) used to assess study quality in the health and social sciences (Katrak et al., 2004). Tools have been adopted to appraise the quality of studies with specific designs such as experimental (e.g., Jadad et al., 1996), systematic reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., Oxman and Guyatt, 1991), and qualitative (e.g., Long and Godfrey, 2004) research. Generic tools, purported to be applicable to multiple study designs and across multiple disciplines, also exist (e.g., Glynn, 2006). However, most quality assessment tools have not been developed with sufficient attention to validity and reliability (Katrak et al., 2004; Moyer and Finney, 2005; Crowe and Sheppard, 2011; Johnson et al., 2014), and no quality assessment tool has been universally endorsed as fully sufficient to assess study quality (Alderson et al., 2003). Prominent criticisms of existing tools refer to the absence of validity and reliability checks in their development, as well as the absence of clear guidance on assessment procedures and scoring (Moyer and Finney, 2005; Crowe and Sheppard, 2011). Despite these limitations, quality assessment tools have been applied extensively across health and social sciences, especially in evidence syntheses.

In psychology, study quality assessment was not recognized as an integral component of the research process until relatively recently. Formal recommendations for conducting quality appraisal in meta-analyses in psychology initially appeared in the Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS) and the American Psychological Association publication manual (APA, 2006a; Appelbaum et al., 2018). Since the publication of these guidelines, awareness and application of quality appraisal has expanded rapidly, and, while still not fully accepted as standard practice, quality appraisal is frequently viewed as an essential component of evidence syntheses in psychology.

Quality Assessment in Psychology Survey Research

Many studies in psychology adopt survey methods. Surveys are used extensively across psychology disciplines to examine relations among psychological constructs measured through psychometric scaling, and to test hypotheses with respect to relations among constructs (Check and Schutt, 2012; Ponto, 2015). However, despite the increasing demand for quality appraisal and the pervasiveness of survey designs in psychology, there are no quality assessment tools developed specifically for survey research in psychology. Given the centrality of survey methods (Ponto, 2015), development of a dedicated, fit-for-purpose quality tool should be considered a priority.

The lack of tools to appraise study quality in survey research has led researchers to adapt tools from other disciplines, or to identify relevant quality criteria from scratch and develop their own tool. To illustrate, in their meta-analysis linking job satisfaction to health outcomes, Faragher et al. (2005) stated that “…a thorough search failed to identify criteria suitable for correlational studies. A measure of methodological rigor was thus developed specifically for this meta-analysis” (p. 107). More recently, Hoffmann et al. (2017) in a meta-analysis of cognitive mechanisms and travel mode choice stated: “No suitable quality assessment tool was found to assess such survey studies. We therefore applied three criteria that were highlighted across six previous studies recommending bias assessment in correlational studies” (p. 635). In the absence of quality appraisal tools, some meta-analyses, especially those including intervention studies, have implemented universal reporting guidelines as proxies for study quality appraisal (Begg et al., 1996; Jarlais et al., 2004; Von Elm et al., 2007; Moher et al., 2009). Although these universal reporting guidelines are well-accepted, they are not, strictly speaking, quality appraisal tools, and it is unclear if they are suitable for assessing study quality in psychology, including research adopting survey methods.

The application of different tools, or individual criteria, to assess research quality, has a number of drawbacks. First, applying different tools to the same body of evidence can produce different conclusions about the quality of the evidence. This would have serious implications within the context of a meta-analysis, as the effect size may vary as a function of the quality appraisal tool used. For example, Armijo-Olivo et al. (2012) compared the performance of two frequently-used quality appraisal tools, the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (CCRBT; Higgins and Altman, 2008) and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP; Jackson and Waters, 2005) in a systematic review of the effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions to improve the management of cancer pain, and found that both tools performed differently. Similarly, Jüni et al. (1999) applied 25 quality appraisal scales to the results of a meta-analysis comparing low-molecular-weight heparin with standard heparin for clot prevention in general surgery, and found that different quality scales produced different conclusions regarding the relative benefits of heparin treatments. For studies classed as high quality on some tools, there was little difference in outcome for two types of heparin, whereas for studies classed as high quality on others, one was found to be superior. Moreover, the overall effect size was positively associated with scores on some quality tools but inversely associated with scores on others. Second, the adapted quality assessment tools used by psychologists were not developed to evaluate research in psychology, and may consequently lack validity, and incompletely cover important study quality components.

Problems Arising from Quality Assessment Methods: An Illustration

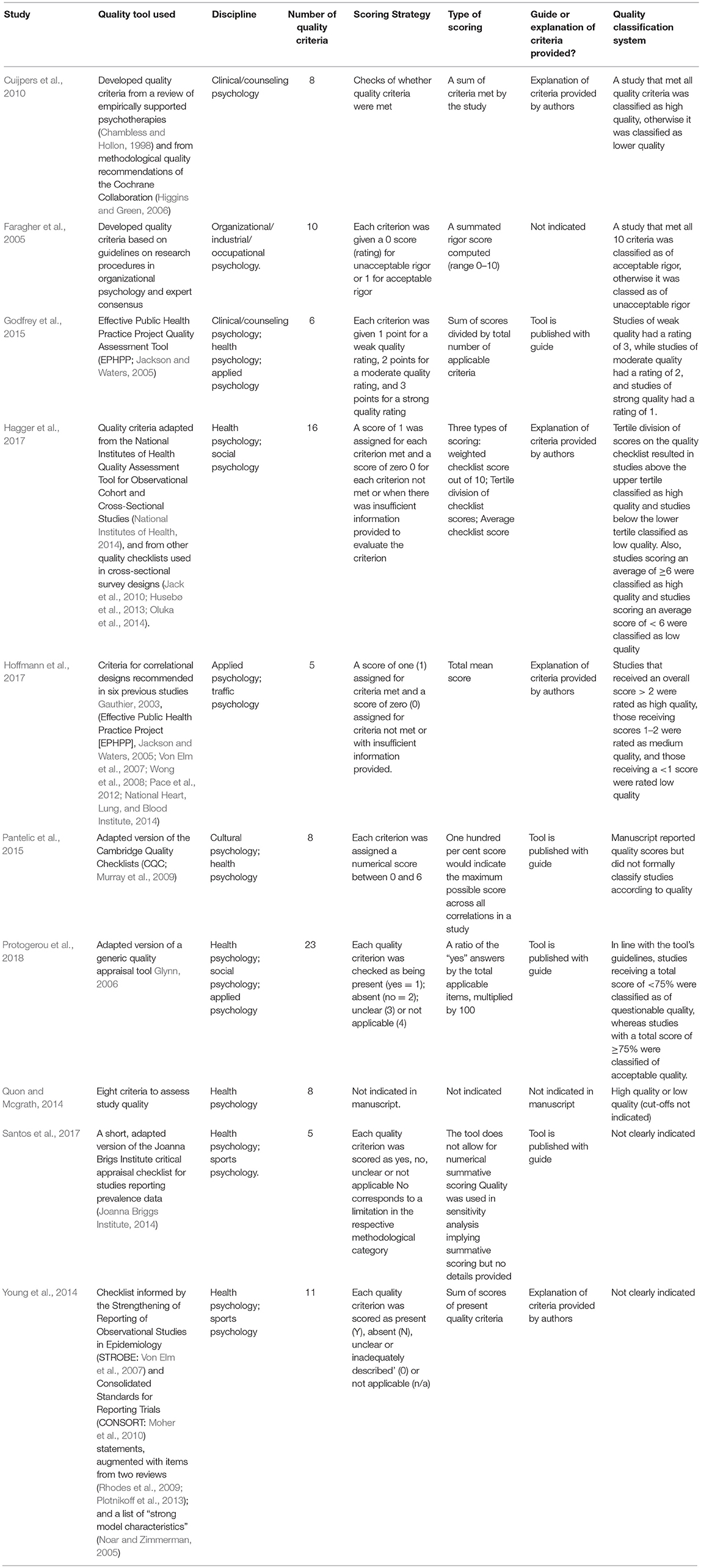

To illustrate the longstanding problems resulting from the absence of a fit-for-purpose tool and the application of a variety of quality appraisal strategies, we provide examples from a brief summary of quality assessments from meta-analyses of psychological survey research (Table 1)1 We identified two prominent limitations of the tools: the quality criteria adopted and the scoring strategies employed.

Quality Criteria

The number of assessed quality criteria ranged between 5 and 23 across the meta-analyses. Also, the type and origin of quality criteria was highly variable. For instance, two meta-analyses (Faragher et al., 2005; Cuijpers et al., 2010) developed quality criteria specifically for their research, while seven meta-analyses (Young et al., 2014; Godfrey et al., 2015; Pantelic et al., 2015; Hagger et al., 2017; Hoffmann et al., 2017; Santos et al., 2017) applied adapted criteria from existing quality tools, reporting guidelines, and literature searches. One study indicated quality criteria without explaining how those were developed or chosen (Quon and Mcgrath, 2014). Although most studies appraised sampling and recruitment procedures, there was variability in the criteria adopted. For example, Hoffmann et al. (2017) appraised whether or not the sample size was sufficient to analyze data using structural equation modeling, while (Quon and Mcgrath, 2014) adopted an absolute total sample size (N = 1000) as their criterion for quality. Similarly, most studies assessed the “appropriateness” of statistical analyses, without clarifying what was considered “appropriate”.

Assessment and Scoring

There was substantive variability in the scoring strategies used to assess study quality across the meta-analyses. Some meta-analyses adopted numerical scoring systems calculating overall percentages, summary scores, and mean scores for the quality criteria adopted (e.g., Protogerou et al., 2018), while other studies did not employ numerical or overall scoring (e.g., Santos et al., 2017). In relation to this, most studies classified studies in terms of high (or “acceptable”) quality vs. low (or “questionable”) quality, while others did not categorize studies in terms of quality. Some studies indicated that quality assessment was informed by published manuals or guidelines on quality criteria, while other studies provided no information on the guidelines or definitions of criteria adopted.

Given the disparate quality appraisal strategies adopted by the meta-analyses, we contend, in line with Armijo-Olivo et al. (2012) and Jüni et al. (1999), that quality assessment outcomes are dependent on the specific tool applied, and that different tools might lead to different conclusions on quality. Moreover, it would be difficult to replicate the quality assessment procedures adopted in most of these meta-analyses, given the limited information provided. We also note that quality criteria relevant to psychological survey studies were missed in the quality assessment on some meta-analyses. For example, ethical requirements, such as consent and debriefing procedures, and response and attrition rates were not checked consistently.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Assessment of study quality is an important practice to promote greater precision, transparency, and evaluation of research in psychology. Assessing the quality of studies may permit researchers to draw effective conclusions and broader inferences with respect to results from primary studies, and when synthesizing research across studies, provide the opportunity to evaluate the general quality of research in a particular area. Given the prominence of survey research in psychology, the development of appropriate means to assess the quality of survey research would yield considerable benefits to researchers conducting, and data analysts evaluating, survey research. We argue that a fit-for-purpose quality appraisal tool for survey studies in psychology is needed. We would expect the development of such a tool to be guided by discipline-specific research standards and recommendations (BPS, 2004; APA, 2006b; Asendorpf et al., 2013). We would also expect the tool to be developed through established methods, such as expert consensus, to ensure satisfactory validity and reliability of the resulting tool (for examples and discussion of these strategies see Jones and Hunter, 1995; Jadad et al., 1996; Crowe and Sheppard, 2011; Jarde et al., 2013; Waggoner et al., 2016).

Author Contributions

CP and MH conceived the ideas presented in the manuscript and drafted the manuscript.

Funding

MH contribution was supported by a Finland Distinguished Professor (FiDiPro) award (Dnro 1801/31/2105) from Business Finland.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^A comprehensive version of Table 1 with full details of study quality criteria is provided online: https://osf.io/wbj5z/?view_only=ffbb265cf43f498999ab69bc57c60eb5

References

Alderson, P., Green, S., and Higgins, J. P. T. (2003). Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook. Available Online at: http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/hbook.htm (Accessed October 1, 2018).

APA (2006a). American Psychological Association Publication Manual. Washington, DC: American Psychological Society.

APA (2006b). Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am. Psychol. 61, 271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., and Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: the APA publications and communications board task force report. Am. Psychol. 73, 3–25. doi: 10.1037/amp0000191

Armijo-Olivo, S., Stiles, C. R., Hagen, N. A., Biondo, P. D., and Cummings, G. G. (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 18, 12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

Asendorpf, J. B., Conner, M., De Fruyt, F., De Houwer, J., Denissen, J. J. A., Fiedler, K., et al. (2013). Recommendations for increasing replicability in psychology. Eur. J. Pers. 27, 108–119. doi: 10.1002/per.1919

Begg, C., Cho, M., and Eastwood, S. (1996). Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORTstatement. JAMA 276, 637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540080059030

BPS (2004). Guidelines for Minimum Standards of Ethical Approval in Psychological Research. Leicester: British Psychological Society. Available online at: http://www.bps.org.uk/ (Accessed October 1, 2018).

Chambless, D. L., and Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 66, 7–18.

Check, J., and Schutt, R. K. (2012). “Survey research,” in Research Methods in Education, eds J. Check and R.K. Schutt (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 159–185.

Cooper, H. (2011). Reporting Research in Psychology: How to Meet Journal Article Reporting Standards. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Crowe, M., and Sheppard, L. (2011). A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008

Cuijpers, P., Van Straten, A., Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D., and Andersson, G. (2010). The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol. Med. 40, 211–223. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006114

Faragher, E. B., Cass, M., and Cooper, C. L. (2005). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 62, 105–112. doi: 10.1136/oem.2002.006734

Gauthier, B. (2003). Assessing Survey Research: A Principled Approach. Available online at http://www.circum.qc.ca/textes/assessing_survey_research.pdf (Accessed January 27, 2017).

Glynn, L. (2006). A critical appraisal tool for library and information research. Library Hi Tech 24, 387–399. doi: 10.1108/07378830610692154

Godfrey, K. M., Gallo, L. C., and Afari, N. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Med. 38, 348–362. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5

Greenhalgh, J., and Brown, T. (2017). “Quality assessment: Where do I begin?,” in Doing a Systematic Review: A Student's Guide, eds A. Boland, M. G. Cherry and R. Dickson (London: Sage), 61–83.

Greenhalgh, T. (2014). How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine. London, UK: Wiley.

Guyatt, G., Cairns, J., and Churchill, D. (1992). Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 268, 2420–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032

Hagger, M. S., Koch, S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., and Orbell, S. (2017). The common-sense model of self-regulation: meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychol. Bull. 143, 1117–1154. doi: 10.1037/bul0000118

Higgins, J. P. T., and Altman, D. G. (2008). “Assessing risk of bias in included studies,” in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, eds J. P. T. Higgins and S. Green (Chichester: Wiley), 187–241.

Higgins, J. P. T., and Green, S. (2006). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Hoffmann, C., Abraham, C., White, M. P., Ball, S., and Skippon, S. M. (2017). What cognitive mechanisms predict travel mode choice? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Transport Rev. 37, 631–652. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2017.1285819

Husebø, A. M. L., Dyrstad, S. M., Søreide, J. A., and Bru, E. (2013). Predicting exercise adherence in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational and behavioural factors. J. Clin. Nurs. 22, 4–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04322.x

Jack, K., McLean, S. M., Moffett, J. K., and Gardiner, E. (2010). Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Manual Ther. 15, 220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.12.004

Jackson, N., and Waters, E. (2005). Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot. Int. 20, 367–374. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai022

Jadad, A. R., Moore, R. A., Carroll, D., Jenkinson, C., Reynolds, D. J. M., Gavaghan, D. J., et al. (1996). Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control. Clin. Trials 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/01972456(95)00134-4

Jarde, A., Losilla, J. M., Vives, J., and Rodrigo, M. F. (2013). Q-Coh: a tool to screen the methodological quality of cohort studies in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 13, 138–146. doi: 10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70017-6

Jarlais, D. C. D., Lyles, C., Crepaz, N., and Group, T. T. (2004). Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am. J. Public Health 94, 361–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361

Joanna Briggs Institute (2014). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual: 2014 Edition. The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Johnson, B. T., Low, R. E., and Macdonald, H. V. (2014). Panning for the gold in health research: Incorporating studies' methodological quality in meta-analysis. Psychol. Health 30, 135–152. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.953533

Jones, J., and Hunter, D. (1995). Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 311, 376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376

Jüni, P., Witschi, A., Bloch, R., and Egger, M. (1999). The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 282, 1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054

Katrak, P., Bialocerkowski, A. E., Massy-Westropp, N., Kumar, V. S., and Grimmer, K. A. (2004). A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 4:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-22

Kerr, N. L. (1998). HARKing: hypothesizing after the results are known. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2, 196–217. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0203_4

Khan, K., Kunz, R., Kleijnen, J., and Antes, G. (2011). Systematic Reviews to Support Evidence-Based Medicine. London: Hodder Arnold.

Long, A. F., and Godfrey, M. (2004). An evaluation tool to assess the quality of qualitative research studies. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 7, 181–196. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000045302

Michie, S., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Lawton, R., Parker, D., and Walker, A. (2005). Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual. Safety Health Care 14, 26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

Moher, D., Hopewell, S., Schulz, K. F., Montori, V., Gøtzsche, P. C., Devereaux, P. J., et al. (2010). CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and The Prisma Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moher, D., Pham, B., Jones, A., Cook, D. J., Jadad, A. R., Moher, M., et al. (1998). Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 352, 609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X

Moyer, A., and Finney, J. W. (2005). Rating methodological quality: toward improved assessment and investigation. Account. Res. 12, 299–313. doi: 10.1080/08989620500440287

Murray, J., Farrington, D. P., and Eisner, M. P. (2009). Drawing conclusions about causes from systematic reviews of risk factors: The Cambridge Quality Checklists. J. Exp. Criminol. 5, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11292-008-9066-0

National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (2014). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health (2014). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (Accessed November 14, 2016).

Noar, S. M., and Zimmerman, R. S. (2005). Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ. Res. 20, 275–290. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg113

Oluka, O. C., Nie, S., and Sun, Y. (2014). Quality assessment of TPB-based questionnaires: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 9:e94419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094419

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349:aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716

Oxman, A. D., and Guyatt, G. H. (1991). Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 44, 1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90160-B

Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., et al. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 49, 47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Pantelic, M., Shenderovich, Y., Cluver, L., and Boyes, M. (2015). Predictors of internalised HIV-related stigma: a systematic review of studies in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Psychol. Rev. 9, 469–490. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.996243

Plotnikoff, R. C., Costigan, S. A., Karunamuni, N., and Lubans, D. R. (2013). Social cognitive theories used to explain physical activity behavior in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prevent. Med. 56, 245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.01.013

Protogerou, C., Johnson, B. T., and Hagger, M. S. (2018). An integrated model of condom use in sub-Saharan African youth: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 37, 586–602. doi: 10.1037/hea0000604

Quon, E. C., and Mcgrath, J. J. (2014). Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 33, 433–447. doi: 10.1037/a0033716

Rhodes, R. E., Fiala, B., and Conner, M. (2009). A review and meta-analysis of affective judgments and physical activity in adult populations. Ann. Behav. Med. 38, 180–204. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9147-y

Santos, I., Sniehotta, F. F., Marques, M. M., Carraça, E. V., and Teixeira, P. J. (2017). Prevalence of personal weight control attempts in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. 18, 32–50. doi: 10.1111/obr.12466

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., and Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1359–1366. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417632

Von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., and Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prevent. Med. 45, 247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.012

Waggoner, J., Carline, J. D., and Durning, S. J. (2016). Is there a consensus on consensus methodology? Descriptions and recommendations for future consensus research. Acad. Med. 91, 663–668. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000001092

Wong, W. C., Cheung, C. S., and Hart, G. J. (2008). Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 5, 1–23. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-23

Keywords: study quality appraisal, psychology, correlational studies, survey studies, evidence syntheses, transparency

Citation: Protogerou C and Hagger MS (2019) A Case For a Study Quality Appraisal in Survey Studies in Psychology. Front. Psychol. 9:2788. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02788

Received: 26 October 2018; Accepted: 31 December 2018;

Published: 24 January 2019.

Edited by:

Edgar Erdfelder, Universität Mannheim, GermanyReviewed by:

Timo Gnambs, Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LG), GermanyCopyright © 2019 Protogerou and Hagger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cleo Protogerou, Y2xlby5wcm90b2dlcm91QHVjdC5hYy56YQ==

Cleo Protogerou

Cleo Protogerou Martin S. Hagger

Martin S. Hagger