94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 27 February 2018

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00239

Marco Innamorati1*

Marco Innamorati1* Laura Parolin2

Laura Parolin2 Angela Tagini2

Angela Tagini2 Alessandra Santona2

Alessandra Santona2 Andrea Bosco3

Andrea Bosco3 Pietro De Carli2,4

Pietro De Carli2,4 Giovanni L. Palmisano3

Giovanni L. Palmisano3 Filippo Pergola1

Filippo Pergola1 Diego Sarracino2

Diego Sarracino2In this study, bullying is examined in light of the “prosocial security hypothesis”— i.e., the hypothesis that insecure attachment, with temperamental dispositions such as sensation seeking, may foster individualistic, competitive value orientations and problem behaviors. A group of 375 Italian students (53% female; Mean age = 12.58, SD = 1.08) completed anonymous questionnaires regarding attachment security, social values, sensation seeking, and bullying behaviors. Path analysis showed that attachment to mother was negatively associated with bullying of others, both directly and through the mediating role of conservative socially oriented values, while attachment to father was directly associated with victimization. Sensation seeking predicted bullying of others and victimization both directly and through the mediating role of conservative socially oriented values. Adolescents’ gender affected how attachment moderated the relationship between sensation seeking and problem behavior.

A “uniform definition” of bullying suggested by the U S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Gladden et al., 2014) is any undesirable, repetitive aggressive behavior(s) by youth(s) who are not siblings or current dating partners, involving an observed or perceived power imbalance. The result may often involve distress at physical, social and psychological levels. This definition builds conceptually on the extensive work by Olweus (1978, 1993,2009), and implies two parties: bullying of others and being victimized. Individuals may bully and be victims of this behavior at the same time, even though individuals tend to play only one of the two roles (Cook et al., 2010).

Bullying seems to be a widespread phenomenon in teens who differ in gender, age, ethnicity, education, and socioeconomic status (Boulton et al., 2002; Scheithauer et al., 2006; Olweus, 2009; Troop-Gordon, 2017). Involvement in bullying is observed ubiquitously across continents and cultures, ranging from 7% to more than 70% both for boys girls (Carney and Merrell, 2001; Kanetsuna and Smith, 2002; Eslea et al., 2004; Kyriakides et al., 2006; Cook et al., 2010; Williams and Veeh, 2012). The significant differences are explainable with the different definitions of bullying or being exposed to bullying given by the various observers: a rough estimate of 29–46% of children involved in bullying can be considered to be reliable. Long-term consequences of being bullied seem to include serious mental disturbances (Arseneault, 2017; Evans-Lacko et al., 2017).

Theories that attribute bullying to being raised either in difficult environments or in certain types of families do not sufficiently explain this behavior. On the contrary, as many studies indicated, bullying is a complex phenomenon which depends on the interaction between temperamental factors, family environment, and social value orientation (Espelage et al., 2001; Stevens et al., 2002; Cook et al., 2010; Holt et al., 2017; Troop-Gordon, 2017). Some authors also consider community factors (Randall, 1996), peer factors (O’Connell et al., 1999), and other individual factors like temperamental, social-cognitive and emotional factors (Matthiesen and Einarsen (2004).

Only temperamental factors, on the whole, can influence conducts “before” attachment experience. Temperament can be considered the innate tendency, which should be genetically given, to react in a certain way to environmental stimuli and specifically to intensity, frequency and threshold of affective responses (Kernberg, 2005). Among temperamental factors, sensation seeking was chosen to be taken into consideration for several reasons. Hoyle et al. (2002) define it as a need for varied, novel, and complex sensations and experiences and the willingness to take physical and social risks. Several studies show that sensation seeking may be an effective predictor of a wide range of problem behaviors in adolescence (Zuckerman, 1994, 2007; Hoyle et al., 2002; Sarracino et al., 2011) and, specifically, of the likelihood of engaging in bullying and of being victims of bullying (Lovegrove et al., 2012).

Regarding family environment, previous studies have connected bullying with limited parental involvement (Flouri and Buchanan, 2003), and absence of family cohesion in boys engaged in bullying behavior (Bowers et al., 1992). A large meta-analysis by Lereya et al. (2013), conducted on studies from 1970 to 2012, shows that both victims and bully/victims are more likely to have been exposed to negative parenting behavior. The effects are generally more significant for bully/victims than for victims. Positive parenting behavior is on the contrary to be considered protective against victimization from peers. The protective effects were generally small to moderate so negative parenting behavior is related to the risk of becoming a bully/victim or victim of bullying at school.

Attachment theory constitutes a potential framework for explaining the association between relationships with parents and problematic relationships with peers. A link between insecure attachment style and problem behavior like bullying seems to be particularly noteworthy during adolescence, which is a period characterized by the reorganization of the relationship with parents, and by the gradual transfer of some attachment functions to peers (Allen and Tan, 2016). A study on 1,921 adolescents, aged 10–18 years old (Kõiv, 2012), found that adolescent victims of bullying were less securely attached than adolescents who engage in bullying and peers not involved in bullying. In the same study, bullying adolescents had higher levels on avoidant attachment scales than adolescents who were bullied and their peers not involved in bullying. Unsecure attachment can be related to the social behavior of bullying people, characterized by high aggression and poor social skills (Marini et al., 2006; Gradinger et al., 2009). Anxious and avoidant attachment were found by some authors to be typical of the victims of bullying (Ireland and Power, 2004). Anxious and avoidant maternal attachment were also positively related to interpersonal aggression in a college student sample (Cummings-Robeau et al., 2009). On the whole, it seems that individuals with secure attachments are less likely to bully others or be bullied by others (Murphy et al., 2017).

Although many studies indicated a relation between attachment insecurity and bullying, there are few studies on how attachment might affect bullying behaviors and being victims of bullying. Is the link between attachment and bullying direct or mediated by other factors? A fascinating hypothesis in the literature is that the experience of growing up in a nurturing and responsive family environment, and consequently attachment security, may facilitate a prosocial value orientation—i.e., relatively stable individual preferences or desirable goals that reflect socialization and that serve as guiding principles during people’s lives (Schwartz, 1992; Bilsky and Schwartz, 1994; Knafo and Schwartz, 2003). According to this prosocial-security hypothesis, the internalization of a secure internal model of self and others may facilitate the development of “conservative social-oriented values”—i.e., being benevolent toward others, preferring security, being tied to traditions, behaving similarly to people considered to be friends and peers. These values can be measured on specific rating scales: universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security (van Lange et al., 1997). Individuals who scored higher on these values, in particular on benevolence, remembered warmer and less aggressive parents (Aluja et al., 2005). The choice of conservative social-oriented values, in turn, may protect teens from problem behaviors, and more specifically from externalizing behaviors (Barnea et al., 1992). Moreover, high levels of benevolence were related to socialized behaviors (Aluja-Fabregat et al., 1999). On the contrary, insecure adolescents may have learned to perceive interpersonal relationships as threatening, and this may increase “dynamic self-oriented values” (including power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction), as shown by van Lange et al. (1997; see also Sarracino et al., 2011; Sarracino and Innamorati, 2012). People who prefer these values, especially power, remember more neglecting and less warm parents (Meesters et al., 1995). Consequently, competitive and aggressive behaviors may be favored (Aluja-Fabregat and Torrubia-Beltri, 1998) and transmitted across generations (De Carli et al., 2016, 2017a,b; Wang et al., 2017).

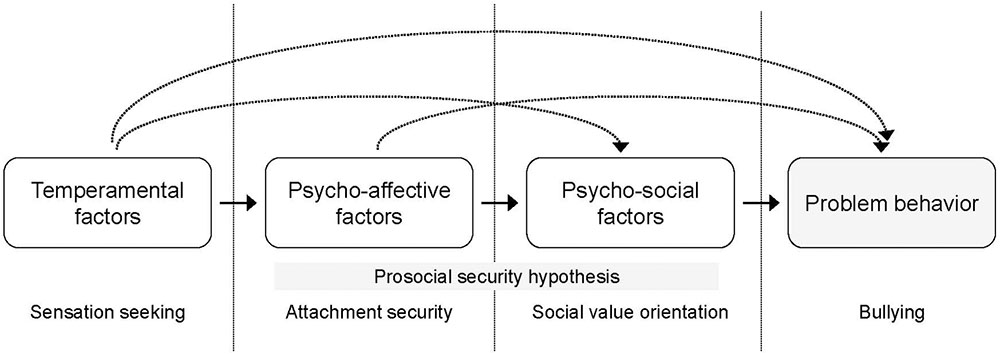

A number of studies empirically supported the prosocial-security hypothesis through different phases of adolescence and early adulthood, showing a significant association between attachment security and prosocial values (van Lange et al., 1997; Mikulincer et al., 2003; Sarracino et al., 2011; Sarracino and Innamorati, 2012). Although we are far from having a comprehensive view, a plausible model of the relations among temperamental factors, attachment, social value orientation, and problem behaviors in adolescence can be suggested (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. A unifying view of the relationships between temperamental, psycho-affective and psycho-social factor affecting problem behavior in adolescence.

Bullying concerns both males and females. Although recent studies indicate that girls are more physically aggressive than in the past (see for example, Jamal et al., 2015), the psychological repercussions on girls and boys may differ (Besag, 2006). In fact, girls are usually involved in more indirect and relational forms of bullying than boys (Crick and Grotpeter, 1995; Caravita et al., 2009; Jimerson et al., 2009). These differences are in line with evidence that boys are more likely to have externalizing behaviors than girls—with the exception of hedonistic habits like smoking and drinking (for a meta-analysis, see Byrnes et al., 1999). Moreover, boys prioritize dynamic self-oriented values (i.e., achievement and power), while girls tend to favor conservative social-oriented values (i.e., benevolence and universalism). Thus, boys are believed to be more likely to experience problematic behaviors than girls, due to their attempts to achieve social power and authority with respect to their peers (see also Wilson and Daly, 1985; Liu et al., 2007). In these studies, boys also scored higher in sensation seeking than girls.

Moreover, several studies found gender differences in adolescents’ attachment. Adolescent girls report greater attachment security with their mothers than to their fathers; conversely, while boys experience greater attachment security with their fathers (Verschueren and Marcoen, 2005; Diener et al., 2008; Del Giudice, 2009; Sarracino et al., 2011). Williams and Kennedy (2012) observed that girls were more likely to be involved in bullying when they had higher levels of attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety with their mothers, and higher levels of attachment anxiety with their fathers. On the other hand, boys were more likely to bully when they experienced higher levels of attachment anxiety with their fathers. In light of these findings, Sarracino et al. (2011) hypothesized that gender not only has a direct effect on the single variables such as attachment, social value orientation, sensation seeking and bullying, but may influence the prosocial-security model. In other words, gender may affect the way attachment mediates the relationship between sensation seeking and problem behavior.

While the different studies focused on specific aspects of the problem, to date few models consider and integrate the links between temperamental, psychological and psychosocial variables, which may be involved in adolescent bullying. The contribution of the present study consists in the attempt to extend the prosocial-security hypothesis to the study of bullying. We have included sensation seeking in this model because, in a previous study, two of the authors of this paper found sensation seeking to be strongly tied to at risk behavior in pre-adolescence through the mediation of attachment (Sarracino et al., 2011), and decided to verify if the same factor is a predictor of bullying.

Specifically, our study explored the relationships between sensation seeking (as a temperamental predisposition to risk-taking), attachment security (related to family environment and parenting style), and social value orientation (connected to family and the socio-cultural context), and how this network of innate and cultural-driven influences can affect bullying-related behaviors (bullying or being bullied) in early adolescence. In this regard, we explored the possibility that a social value orientation can mediate the relationship between attachment security and both bullying and being victimized by bullying. In line with Sarracino et al.’s (2011) findings, we expected that more secure adolescents would have more “conservative social-oriented values,” less sensation seeking, and fewer bullying-related behaviors. Conversely, we hypothesized that insecure attachment, dynamic self-oriented values, and sensation seeking would be associated with more bullying-related behaviors.

Another aim of the study was to explore the role of gender in our model. Specifically, we expected different patterns for boys and girls, in which attachment moderates the relationship between sensation seeking and bullying.

Research assistants recruited 375 Italian early adolescents from two middle schools in Northern Italy. Average ages of participants ranged from 11 to 16 years (M = 12.58, SD = 1.08). Forty-seven percent of participants were 11–12 years old, 49% were 13–14 years old, and 4% were 15–16 years old. Fifty-three percent of participants were female. Seventy-six percent of participants reported being born in Northern Italy, 7% in Central or Southern Italy, 4% in other European countries, and 13% in non-European countries. With regard to parent nationality, 77% of parents were both Italians, 19% were both foreigners, and 4% were mixed. Eighty-one percent of participants reported living with both parents, 15% with mothers only, 2% only with their fathers, 1% with other relatives, and 1% lived in welfare structures. Twelve percent of participants reported living in a family with a low or medium-low income, 53% reported belonging to a family with a medium income, and 35% declared a medium-high or high income. Non-native Italian participants spoke and understood Italian adequately as attested by their teachers, and thus the school or parents deemed no help was necessary.

The present study is part of a multidisciplinary research project concerning the role of psychodynamic factors in problem behaviors in different stages of life (Innamorati et al., 2010; Dellantonio et al., 2012; Lo Verde et al., 2012; Sarracino et al., 2014; Sassaroli et al., 2015). The review board of the University of Rome “Tor Vergata” approved the study protocol, in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. After the school principals’ approval of the study, research assistants described it to the classes, answered questions, and provided them with the informed consent form to be signed by parents, along with a letter, signed by the study authors and the school principals, explaining the importance of collaboration between schools and the universities. Participation rate was unexpectedly high (98%), which may be explained by the fact that data collection occurred during school hours, replacing the usual lessons. At a given date, research assistants administered during class information forms (containing questions on gender, age, birthplace, parents’ nationality, family situation, and income), and a set of pencil-and-paper questionnaires. The questionnaire took approximately 1 h to complete. A research assistant informed participants that the questionnaire was anonymous and that they would not be judged by their answers. Subsequently, she explained the aims of the study and answered any further questions.

Attachment security during early adolescence to each parent was assessed by means of the Security Scale (SS; Kerns et al., 1996). The SS is a 15-item questionnaire for children and early adolescents. Several studies showed a good validity of the Security Scale as a measure of perceived attachment security for adolescents (e.g., Kerns et al., 1996; Van Ryzin and Leve, 2012).

The Italian version of the SS (Sarracino et al., 2011) has a 4-point Likert format. An example item is: “Some kids find it easy to trust their mom.” We calculated the mean of the scores in order to obtain a single score. Reliability coefficients for the mother and father versions were α = 0.77 and α = 0.80 respectively, in line with findings reported by Kerns et al. (1996) and Sarracino et al. (2011).

Social value orientation was measured using the Portraits Values Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz et al., 2001). This inventory consists of 40-item in terms of short verbal descriptions, which refer to ten values: Power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security. Each item describes a third person that points to the importance of a value (e.g., “It is very important to him/her to help people around him/her. He/she wants to care for their well-being” as an example of the “self-transcendence” item). The 10-value items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me). Previous factor analyses (Hinz et al., 2005; Sarracino et al., 2011) suggested a two-factor structure, the first of which indicated a “dynamic self-orientation” (including power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction), and the second describing a “conservative social orientation” (including universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security). Several studies used the PVQ to assess value constructs of early adolescents across a wide range of cultures (Schwartz et al., 2001; Hinz et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2007; Sarracino et al., 2011). For the Italian version of the PVQ used in the present study, α coefficients were 0.71 for dynamic self-orientation and 0.73 for conservative social orientation. PVQ indexes were adequate and demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity in the multitrait-multimethod (MTMM) analysis and exhibited good construct validity (Schwartz et al., 2001).

The dispositional risk for various problem behaviors related to sensation seeking was assessed using the Brief Sensation-Seeking Scale (BSSS-8; Hoyle et al., 2002; Stephenson et al., 2007), which consists of 5-point scales, ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree” (e.g., “I like to do frightening things”). The brief version of the scale consisted of eight items, and was back translated into Italian by two professional translators. Its internal reliability was satisfactory (α = 0.77), and in line with findings from previous studies on adolescents (Hoyle et al., 2002; Sarracino et al., 2011). In order to validate the Italian version of the Sensation Seeking Scale we performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The hypothesized one factor solution (Hoyle et al., 2002) showed an adequate fit (χ2 = 33.98, p = 0.02, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.046, p = 0.57, 95% CI [0.02, 0.07], SRMR = 0.05). Therefore the subsequent analysis were performed using a composite score computed as the mean of the items.

In order to assess participant self-reports of bullying behaviors, we used the Bully/Victim Questionnaire (BVQ; Olweus, 1996, 2002). The BVQ is widely used throughout the world and has satisfactory psychometric properties in terms of construct validity and reliability (e.g., Kyriakides et al., 2006). For the purposes of the present study, we selected 16 items of the questionnaire: items 5–12 for BV (i.e., the act of bullying against the child who is responding to the instrument) and items 25–32 for BO (i.e., bullying behavior manifested by the respondent; Table 1). For each item, adolescents indicated how often they have been bullied or how often they bullied others during the past couple of months: never or hardly ever, sometimes, or frequently. Internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s α coefficient, was 0.79 for the “Being Victimized” (BV) scale and 0.78 for the “Bullying Others” (BO) scale.

We performed all the analyses with R software, using the package for structural equation modeling “lavaan” (Rosseel, 2012). In order to handle missing values (89.6% of the respondents had no missing values, with a maximum of 2.9% per variable), we imputed data using the EM algorithm (Schafer and Graham, 2002). Then we adopted a more conservative approach, and repeated all the analyses performing multiple imputations with the “Amelia” package (Honaker et al., 2011). We reported only single imputation analyses since results did not differ for multiple imputed data.

Table 2 presents the descriptive analyses of the variables of the study divided by gender. Boys showed higher scores for sensation seeking, dynamic self-oriented values (PVQ), and bullying behaviors. Girls had higher scores on conservative social-oriented values.

In order to test the prosocial security hypothesis, we performed a path analysis, which estimated the effects of sensation seeking, attachment security, and social value orientation on the bully/victim behaviors. The developmental onset of the predictors determined the direction of the effects of the path models. Thus, since sensation seeking is a personality trait (e.g., Zuckerman, 2007), we hypothesized that it affects attachment security, which depends on environmental factors and develops later in childhood (e.g., Pasco Fearon et al., 2006). In a similar way, our path model relied on the assumption that attachment security matures prior to social value orientation and therefore influences the latter. Finally, we assumed that attachment security, social value orientation and sensation seeking affect bullying at a behavioral level. We allowed for the two attachment security factors to co-vary with each other, as well as the two social value orientation factors and the two bullying outcome variables (bullying and victim of bullying).

We used the following indices to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model: The chi-square statistic, which should be non-significant; the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), which should approach 0.95 to indicate optimal fit (Brown, 2015); the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) and the root mean square residual (SRMR), which should approach 0.05 and 0.08, respectively, to indicate a good fit (Kline, 2015); non-significant probability values associated with the Cfit of RMSEA. The sample size seems adequate for the requirements of structural equation models presented by Kline (2015).

Figure 2 illustrates the path analysis of the hypothesized model. The overall fit measures indicated that the fit of the model was adequate (χ2 = 5.20, p = 0.07, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06, p = 0.26, 95% CI [0.00, 0.14], SRMR = 0.005). Significant paths showed the effect of sensation seeking in predicting BO and BV both directly and, only for BO, through the mediating role of conservative social-oriented values (mediated path: b = 0.04 [β = 0.11], p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.019, 0.059], total effect: b = 0.09 [β = 0.25], p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.053, 0.120]). The results also showed direct significant paths from attachment to the outcome variables.

In order to test the mediation effect of social orientation in the association between attachment to mother and bullying, we computed the indirect effect. Results show a significant mediation effect (b = -0.029, [β = -0.05], z = -2.93, p = 0.003, 95% CI [-0.048, -0.010]) and a significant total effect (b = -0.128, [β = -0.22], z = -3.88, p < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.192, -0.063].

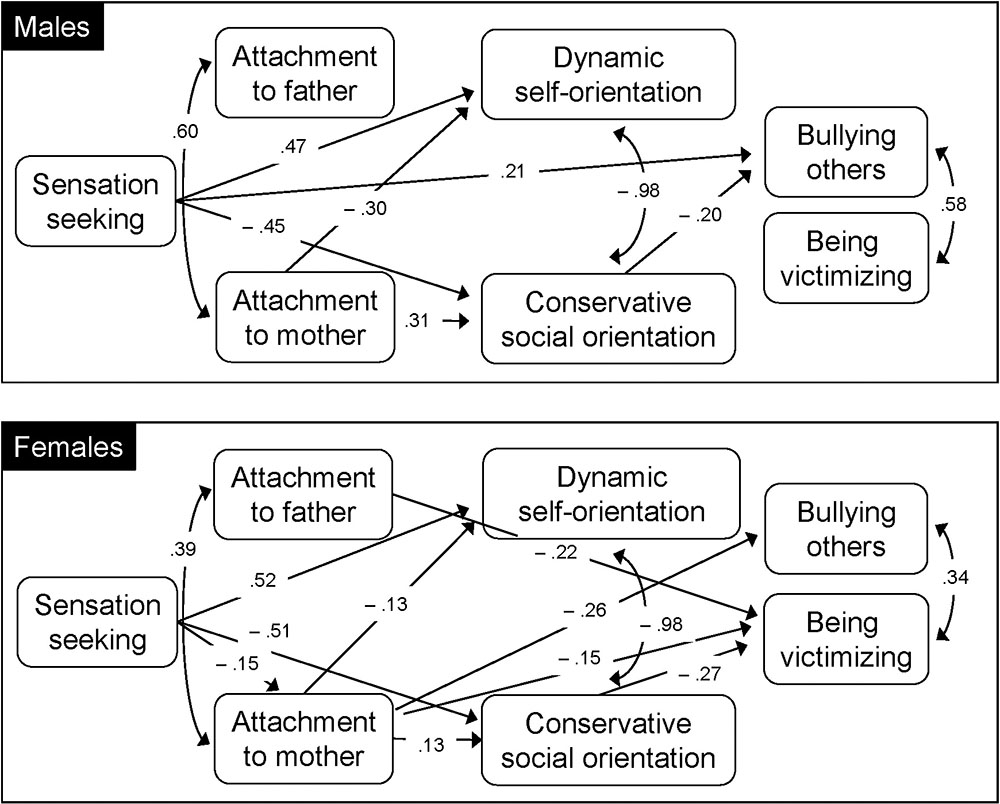

In order to study whether the same pattern of associations was found both in males and females, we tested the previous model in a multiple group analysis. The sample size can support only an exploratory approach, so the findings have to be considered only preliminary and needs further replications. The fit indices can be considered adequate (χ2 = 7.06, p = 0.13, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06, p = 0.31, 95% CI [0.00, 0.14], SRMR = 0.005). The significant paths are presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3. Gender effect on attachment to mother’s role as a moderator between sensation seeking and bullying of others.

We also repeated the test of the indirect effect of social orientation in the association between attachment to mother and bullying to explore whether it is present both for males and females. Results show a significant mediation effect of social orientation in males (b = -0.045, [β = -0.06], z = -2.07, p = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.09, -0.002]) but not in females (b = -0.01, [β = -0.04], z = -1.71, p = 0.09, 95% CI [-0.03, 0.002]).

The relationship we found between attachment security and bullying/victim behavior is consistent with prior evidence, indicating that secure adolescents tend to have higher levels of emotional and social adjustment, relationships that are more positive with both family and peers, and are less likely to engage in problem behaviors with parents and peers (Kerns et al., 1996). With respect to the “prosocial-security hypothesis” (e.g., van Lange et al., 1997; Mikulincer et al., 2003), our findings support this view as a plausible explanation of the link observed between attachment security and bullying. The path that emerged from our data suggests that attachment security is negatively related to bullying, both directly and by promoting prosocial values that become guiding principles. Secure individuals may have learned to recognize contexts and partners as safe and secure, and these grounding experiences may encourage more benevolent attitudes toward others.

Notably, our study seems to indicate that in adolescence, insecure attachment to a particular parent may be related to a specific bullying behavior. In particular, bullying was associated with insecure attachment to mothers, while being victims of bullying was associated with insecure attachment to fathers. This latter finding is in line with previous studies indicating that, in the case of peer-victimized adolescents, more emotional support from fathers was associated with lower levels of emotional and behavioral problems concurrently and across time (Yeung and Leadbearer, 2010). More research is needed to better understand the relationship of attachment to fathers with specific forms of bullying and other problem behaviors, in light of the results of other studies (e.g., Sarracino et al., 2011; Williams and Kennedy, 2012).

In contrast to the direct effect of attachment to fathers on being victimized by bullies, the effect of attachment to mothers was both direct and mediated by a more conservative social orientation. This is more in line with the prosocial security hypothesis, indicating that the “mediational” role of social value orientation may be particularly important in the transition from attachment to mother to relationships with peers. Mothers are usually the main caregiving figures and have a fundamental role in the formation of adolescents’ internal representations of self and others. This not only influences the quality of the relationships with peers, but it is also likely to be associated with how adolescents process social relationships with “others”—that is, their social value orientation and the sense of belonging to a community (Mikulincer et al., 2003; Sarracino and Innamorati, 2012). Further studies are needed to investigate how the general, abstract adolescent internal model of “others” (i.e., their social value orientation) interacts with the internal model of their parents and peers (i.e., their attachment to significant figures).

Further, our study indicates that sensation seeking is an important temperamental variable during adolescence, which may be related to bullying/victim behaviors both directly and through the mediating role of conservative social-oriented values. This is consistent with previous results found by Sarracino et al. (2011), and suggests that sensation seeking should be included in the original prosocial-hypothesis model in predicting problem behavior in adolescence. In light of previous literature, it is not surprising that we found a positive association between sensation seeking and dynamic self-oriented values. Interventions to reduce problem behaviors among adolescents should consider this relation to a greater extent. In fact, a previous study found individual differences in value priorities to be related to prosocial, antisocial, and offending/delinquent behaviors (Bardi and Schwartz, 2003). Schwartz et al. (2001) suggested that when a value has a higher priority, individuals tend to overly pursue it. Furthermore, Liu et al. (2007) showed a relation between value orientation and actual behavior among early adolescents. Our results are also in line with previous findings showing a strong association between stimulation-related/hedonistic values and externalizing behavioral problems, like substance abuse, deviant and at-risk sexual behaviors (Zuckerman, 1994; Goff and Goddard, 1999; Hoyle et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2007). It is possible that individuals who seek self-enhancement tend to very strongly pursue success and dominate others. This behavioral pattern may be strengthened by perceiving interpersonal situations as potentially risky and perilous (i.e., insecure attachment working models), thus further reinforcing their “dynamic self-orientation.”

Regarding gender, in our study we found significant differences in bullying behaviors. As expected, boys scored higher than girls, in line with the greater tendency for direct aggressiveness in boys (Byrnes et al., 1999). These gender differences for bullying should only be considered in light of the other variables examined in this study. Gender also seems to play a significant role in relation to attachment to mother and father (Del Giudice, 2009), as well as preferences for specific social values. Our study is also in line with previous findings across a wide range of cultures (e.g., Schwartz and Rubel, 2005; Liu et al., 2007; Sarracino et al., 2011), which indicated that boys prioritize dynamic self-oriented values (i.e., achievement and power), while girls tend to favor conservative social-oriented values (i.e., benevolence and universalism). Thus, boys are believed to be more likely to experience problematic behaviors than girls, due to their attempts to achieve social power and authority with respect to their peers (see also Liu et al., 2007; Wilson and Daly, 1985). Boys also scored higher in sensation seeking than girls, and this may explain why they seem to be generally more exposed to problem behaviors like bullying.

Gender also affected the way in which attachment mediated the relationship between sensation seeking and bullying. Most notably, results showed a significant mediation effect of social orientation in males but not in females. This finding is both in line with the gender socialization theory, according to which it is easier for same-gender parent–child dyads to establish synchronous interactions from infancy onward (e.g., Feldman, 2003), and with previous studies, indicating that, over time, adolescent girls report feeling more distant, uncomfortable, and withdrawn from their fathers (Youniss and Smollar, 1985).

Overall, our findings confirm that gender represents a key factor in the transition from middle childhood to adolescence, and that gender differences should be expected for many aspects of adolescents’ attachment and psychosocial functioning.

Our study has a number of limitations. Firstly, the study only employed self-report measures. The reliance on a single informant may have caused shared-method variance (i.e., the relation between variables may be in part due to similar measurement methods). Furthermore, self-report measures may cause systematic distortions when investigating problem behavior in adolescents. In fact, even though we assured anonymity to participants, their answers may not be entirely reliable, since we asked them to report if they had participated in deviant and illegal activities at times. Therefore, future research should integrate reports from caregivers and/or observational data relative to caregiver–adolescent interactions.

Second, this study has to be considered as explorative and thus causal interpretations should be made with caution since our data are cross-sectional, and the variables of the study have not been extensively researched in the early adolescence age-group. Longitudinal studies are therefore required in order to explore the direction of effects, and to understand how attachment security and other social experiences interact, and influence children’s social development in general, and bullying more specifically.

Third, our sample was somewhat homogenous concerning social class, family structure, and ethnicity. Therefore, future research should be extended to adolescents from other ethnic backgrounds, family structures (e.g., both single and dual-earners), social contexts (e.g., at-risk populations), and different nationalities.

Despite its limits, this study contributes to the exploration of how early adolescents’ value orientations and bullying behaviors may be related to attachment patterns. Our findings underscore the role of attachment to parents, its association with social values and the dispositional inclinations of early adolescents. Our results further support the general hypothesis that secure attachment relationships, and the resulting emotional connectedness and support, facilitate the development of solid value structures.

Our findings also have repercussions for interventions that aim to reduce bullying and prevent short and long-term effects on mental health as well as the psychosocial adaptation of adolescents involved in bullying. Implementing psycho-educational interventions aimed at promoting secure parental relationships (e.g., Wright and Edginton, 2016) and prosocial values may prove to be an effective method for decreasing bullying, particularly during the “sensitive period” for change which characterizes early adolescence.

MI: original idea of the work, bibliographic research, introduction, and final revision. DS: first draft of the text after introduction, general supervision, design of figures, original idea of the research on attachment, and social value orientation. Other authors: data collecting and statistics.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling Editor declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration with several of the authors LP, AT, AS, PDC, and DS.

Allen, J. P., and Tan, J. S. (2016). “The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence,” in Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 3th Edn, eds J. Cassidy and P. R. Shaver (New York, NY: Guilford), 399–415.

Aluja, A., del Barrio, V., and Garcia, L. F. (2005). Relationships between adolescents’ memory of parental rearing styles, social values and socialization behavior traits. Pers. Individ. Dif. 39, 903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.028

Aluja-Fabregat, A., Ballesté-Almacellas, J., and Torrubia-Beltri, R. (1999). Self-reported personality and school achievement as predictors of teachers perceptions of their students. Pers. Individ. Dif. 27, 743–753. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00276-1

Aluja-Fabregat, A., and Torrubia-Beltri, R. (1998). Viewing of mass media violence, perception of violence, personality and academic achievement. Pers. Individ. Dif. 25, 973–989. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00122-6

Arseneault, L. (2017). The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry 16, 27–28. doi: 10.1002/wps.20399

Bardi, A., and Schwartz, S. (2003). Values and behaviour: strength and structure of relations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 29, 1207–1220. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254602

Barnea, Z., Teichman, M., and Rahav, G. (1992). Personality, cognitive, and interpersonal factors in adolescent substance use: a longitudinal test of an integrative model. J. Youth Adolesc. 21, 187–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01537336

Besag, V. (2006). Understanding Girls’ Friendships, Fights and Feuds: A Practical Approach to Girls’ Bullying. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Bilsky, W., and Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Values and personality. Eur. J. Pers. 8, 163–181. doi: 10.1002/per.2410080303

Boulton, M. J., Trueman, M., and Flemington, I. (2002). Associations between secondary school pupils’ definitions of bullying, attitudes towards bullying, and tendencies to engage in bullying: age and sex differences. Educ. Stud. 28, 353–370. doi: 10.1080/0305569022000042390

Bowers, L., Smith, P. K., and Binney, V. (1992). Cohesion and power in the families of children involved in bully/victim problems at school. J. Fam. Ther. 14, 371–387. doi: 10.1046/j..1992.00467.x

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., and Schafer, W. D. (1999). Sex differences in risk taking: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 125, 367–383. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367

Caravita, S., Di Blasio, P., and Salmivalli, C. (2009). Unique and interactive effects of empathy and social status on involvement in bullying. Soc. Dev. 18, 140–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00465.x

Carney, A. G., and Merrell, K. W. (2001). Bullying in schools: perspectives on understanding and preventing an international problem. Sch. Psychol. Int. 22, 364–382. doi: 10.1177/0143034301223011

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., and Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic investigation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 25, 65–83. doi: 10.1037/a0020149

Crick, N. R., and Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 66, 710–722. doi: 10.2307/1131945

Cummings-Robeau, T. L., Lopez, F. G., and Rice, K. G. (2009). Attachment-related predictors of college students’ problems with interpersonal sensitivity and aggression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 28, 364–391. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.3.364

De Carli, P., Riem, M. M. E., and Parolin, L. (2017a). Approach-avoidance responses to infant facial expressions in nulliparous women: associations with early experience and mood induction. Infant Behav. Dev. 49, 104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.08.005

De Carli, P., Tagini, A., Sarracino, D., Santona, A., Bonalda, V., Cesari, P. E., et al. (2017b). Like grandparents, like parents: empirical evidence and psychoanalytic thinking on the transmission of parenting styles. Bull. Menninger Clin. doi: 10.1521/bumc_2017_81_11 [Epub ahead of print].

De Carli, P., Tagini, A., Sarracino, D., Santona, A., and Parolin, L. (2016). Implicit attitude toward caregiving: the moderating role of adult attachment styles. Front. Psychol. 6:1906. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01906

Dellantonio, S., Innamorati, M., and Pastore, L. (2012). Sensing aliveness: an hypothesis on the constitution of the categories ‘animate’ and ‘inanimate’. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 46, 172–195. doi: 10.1007/s12124-011-9186-3

Del Giudice, M. (2009). Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies. Behav. Brain Sci. 32, 1–21. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X09000016

Diener, M. L., Isabella, R. A., Behunin, M. G., and Wong, M. S. (2008). Attachment to mothers and fathers during middle childhood: associations with child gender, grade, and competence. Soc. Dev. 17, 84–101.

Eslea, M., Menesini, E., Morita, Y., O’Moore, M., Mora-Merchan, J. A., Pereira, B., et al. (2004). Friendship and loneliness among bullies and victims: data from seven countries. Aggress. Behav. 30, 71–83. doi: 10.1002/ab.20006

Espelage, D. L., Bosworth, K., and Simon, T. S. (2001). Short-term stability and change of bullying in middle school students: an examination of demographic, psychosocial, and environmental correlates. Violence Vict. 16, 411–426.

Evans-Lacko, S., Takizawa, R., Brimblecombe, N., King, D., Knapp, M., Maughan, B., et al. (2017). Childhood bullying victimization is associated with use of mental health services over five decades: a longitudinal nationally representative cohort study. Psychol. Med. 47, 127–135. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001719

Feldman, R. (2003). Infant–mother and infant–father synchrony: the coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Ment. Health J. 24, 1–23. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10041

Flouri, E., and Buchanan, A. (2003). The role of mother involvement and father involvement in adolescent bullying behavior. J. Interpers. Violence 18, 634–644. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251129

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., and Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying Surveillance Among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Goff, B. G., and Goddard, H. W. (1999). Terminal core values associated with adolescent problem behaviours. Adolescence 34, 47–60.

Gradinger, P., Strohmeier, D., and Spiel, C. (2009). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying: identification of risk groups for adjustment problems. J. Psychol. 217, 205–213. doi: 10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.205

Hinz, A., Brähler, E., Schmidt, P., and Albani, C. (2005). Investigating the circumplex structure of the portrait values questionnaire (PVQ). J. Individ. Dif. 26, 185–193. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001.26.4.185

Holt, M. K., Green, J. G., Tsay-Vogel, M., Davidson, J., and Brown, C. (2017). Multidisciplinary approaches to research on bullying in adolescence. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40894-016-0041-0

Honaker, J., King, G., and Blackwell, M. (2011). Amelia II: a program for missing data. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–47. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1448

Hoyle, R. H., Stephenson, M. T., Palmgreen, P., Pugzles Lorch, E., and Donohew, R. L. E. (2002). Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers. Individ. Dif. 32, 401–414. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00032-0

Innamorati, M., Sarracino, D., and Dazzi, N. (2010). Motherhood constellation and representational change in pregnancy. Infant Ment. Health J. 31, 379–396. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20261

Ireland, J. L., and Power, C. L. (2004). Attachment, emotional loneliness, and bullying behaviour: a study of adult and young offenders. Aggress. Behav. 30, 298–312. doi: 10.1002/ab.20035

Jamal, F., Bonell, C., Harden, A., and Lorenz, T. (2015). The social ecology of girls’ bullying practices: exploratory research in two London schools. Soc. Health Illn. 37, 731–744. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12231

Jimerson, S. R., Swearer, S. M., and Espelage, D. L. (2009). Handbook of Bullying in School: An International Perspective. London: Routledge.

Kanetsuna, T., and Smith, P. K. (2002). Pupil insights into bullying, and coping with bullying: a bi-national study in Japan and England. J. Sch. Violence? 1, 29–35. doi: 10.1300/J202v01n03_02

Kernberg, O. F. (2005). “Object relations theories and technique,” in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychoanalysis, eds E. S. Person, A. M. Cooper, and G. O. Gabbard (Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.), 57–75.

Kerns, K. A., Klepac, L., and Cole, A. K. (1996). Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child-mother relationship. Dev. Psychol. 32, 457–466. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.457

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Knafo, A., and Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Parenting and adolescents’ accuracy in perceiving parental values. Child Dev. 74, 595–611. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402018

Kõiv, K. (2012). Attachment styles among bullies, victims and uninvolved adolescents. Psychol. Res. 2, 160–165.

Kyriakides, L., Kaloyirou, C., and Lindsay, G. (2006). An analysis of the revised olweus bully/victim questionnaire using the rasch measurement model. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 781–801. doi: 10.1348/000709905X53499

Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., and Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: a meta-analysis study. Child Abuse Negl. 37, 1091–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001

Liu, H., Yu, S., Cottrell, L., Lunn, S., Deveaux, L., Brathwaite, N. V., et al. (2007). Personal values and involvement in problem behaviours among Bahamian early adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 7:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-135

Lovegrove, P. J., Henry, K. L., and Slater, M. D. (2012). Examination of the predictors of latent class typologies of bullying involvement among middle school students. J. Sch. Violence 11, 75–93. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2011.631447

Lo Verde, R., Sarracino, D., and Vigorelli, M. (2012). Therapeutic cycles and referential activity in the analysis of the therapeutic process. Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. 15, 22–31. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2012.99

Marini, Z. A., Dane, A. V., Bosacki, S. L., and Cura, Y. L. C. (2006). Direct and indirect bully-victims: differential psychosocial risk factors associated with adolescents involved in bullying and victimization. Aggress. Behav. 32, 551–569. doi: 10.1002/ab.20155

Matthiesen, S. B., and Einarsen, S. (2004). Psychiatric distress and symptoms of PTSD among victims of bullying at work. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 32, 335–356. doi: 10.1080/03069880410001723558

Meesters, C., Muris, P., and Esselink, T. (1995). Hostility and perceived parental rearing behaviour. Pers. Individ. Dif. 18, 567–570. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)00181-Q

Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., Sapir-Lavid, Y., Yaakobi, E., Arias, K., Tal-Aloni, L., et al. (2003). Attachment theory and concern for others’ welfare: evidence that activation of the sense of secure base promotes endorsement of self-transcendence values. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 299–312. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2504_4

Murphy, T. P., Laible, D., and Augustine, M. (2017). The influences of parent and peer attachment on bullying. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 1388–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.06.003

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., and Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: insights and challenges for intervention. J. Adolesc. 22, 437–452. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0238

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Press.

Olweus, D. (2002). General information about the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, PC Program and Teacher Handbook. Bergen: Mimeo, 1–12.

Olweus, D. (2009). “Understanding and researching bullying: some critical issues,” in The International Handbook of School Bullying, eds S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, and D. L. Espelage (London: Routledge), 9–34.

Pasco Fearon, R. M., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Fonagy, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Schuengel, C., and Bokhorst, C. L. (2006). In search of shared and nonshared environmental factors in security of attachment: a behavior-genetic study of the association between sensitivity and attachment security. Dev. Psychol. 42, 1026–1040. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1026

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01521

Sarracino, D., Garavaglia, A., Gritti, E. S., Parolin, L., and Innamorati, M. (2014). Dropout from cognitive behavioural treatment in a case of bulimia nervosa: the role of the therapeutic alliance. Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. 16, 71–84. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2013.138

Sarracino, D., and Innamorati, M. (2012). “Attachment, social value orientation and at-risk behavior in early adolescence,” in Adolescent Behavior, ed. C. Bassani (New York, NY: Nova), 96–116.

Sarracino, D., Presaghi, F., Degni, S., and Innamorati, M. (2011). Sex-specific relationships among attachment security, social values, and sensation seeking in early adolescence: implications for adolescents’ externalizing problem behaviour. J. Adolesc. 34, 541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.013

Sassaroli, S., Centorame, F., Caselli, G., Favaretto, E., Fiore, F., Gallucci, M., et al. (2015). Anxiety control and metacognitive beliefs mediate the relationship between inflated responsibility and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 228, 560–564. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.053

Schafer, J. L., and Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Methods 7, 147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147

Scheithauer, H., Hayer, T., Petermann, F., and Jugert, G. (2006). Physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying among German students: age trends, gender differences, and correlates. Aggress. Behav. 32, 261–275. doi: 10.1002/ab.20128

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). “Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 25, ed. M. P. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 1–65.

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., and Owens, V. E. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. J. Cross Cultur. Psychol. 32, 519–542. doi: 10.1177/0022022101032005001

Schwartz, S. H., and Rubel, T. (2005). Sex differences in value priorities: cross-cultural and multi-method studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 89, 1010–1028. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.1010

Stephenson, M. T., Velez, L. F., Chalela, P., Ramirez, A., and Hoyle, R. H. (2007). The reliability and validity of the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS-8) with young adult Latino workers: implications for tobacco and alcohol disparity research. Addiction 102, 79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01958.x

Stevens, V., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., and Van Oost, P. (2002). Relationship of the family environment to children’s involvement in bully/victim problems at school. J. Youth Adolesc. 31, 419–428. doi: 10.1023/A:1020207003027

Troop-Gordon, W. (2017). Peer victimization in adolescence: the nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. J. Adolesc. 55, 116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.012

van Lange, P. A. M., Otten, W., De Bruin, E. M. N., and Joireman, J. A. (1997). Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: theory and preliminary evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 733–746. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.733

Van Ryzin, M. J., and Leve, L. D. (2012). Validity evidence for the security scale as a measure of perceived attachment security in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 35, 425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.014

Verschueren, K., and Marcoen, A. (2005). “Perceived security of attachment to mother and father: developmental differences and relations to self-worth and peer relationships at school,” in Attachment in Middle Childhood, eds K. A. Kerns and R. A. Richardson (New York, NY: Guilford), 212–230.

Wang, C., Ryoo, J. H., Swearer, S. M., Turner, R., and Goldberg, T. S. (2017). Longitudinal relationships between bullying and moral disengagement among adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 1304–1317. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0577-0

Williams, J. H., and Veeh, C. A. (2012). Continued knowledge development for understanding bullying and school victimization. J. Adolesc. Health 51, 3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.003

Williams, K., and Kennedy, J. (2012). Bullying behaviors and attachment styles. N. Am. J. Psychol. 14, 321–338.

Wilson, M., and Daly, M. (1985). Competitiveness, risk-taking and violence: the young male syndrome. Ethol. Sociobiol. 6, 59–73. doi: 10.1016/0162-3095(85)90041-X

Wright, B., and Edginton, E. (2016). Evidence-based parenting interventions to promote secure attachment: findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Pediatr. Health 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2333794X16661888

Yeung, R., and Leadbearer, B. (2010). Adults make a difference: the protective effects of parent and teacher emotional support on emotional and behavioral problems of peer-victimized adolescents. J. Commun. Psychol. 38, 80–98. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20353

Youniss, J., and Smollar, J. (1985). Adolescent Relations with Mothers, Fathers, and Friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioural Expressions and Biosocial Bases of Sensation Seeking. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: attachment, social value orientation, sensation seeking, bullying, early adolescence

Citation: Innamorati M, Parolin L, Tagini A, Santona A, Bosco A, De Carli P, Palmisano GL, Pergola F and Sarracino D (2018) Attachment, Social Value Orientation, Sensation Seeking, and Bullying in Early Adolescence. Front. Psychol. 9:239. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00239

Received: 20 July 2017; Accepted: 12 February 2018;

Published: 27 February 2018.

Edited by:

Ilaria Grazzani, Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, ItalyReviewed by:

Annalaura Nocentini, Università degli Studi di Firenze, ItalyCopyright © 2018 Innamorati, Parolin, Tagini, Santona, Bosco, De Carli, Palmisano, Pergola and Sarracino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marco Innamorati, aW5uYW1vcmF0aUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.