- 1Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, United States

- 2Cannon-Bowers Consulting, Orlando, FL, United States

- 3Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory, Groton, CT, United States

Resilience has been recognized as an important phenomenon for understanding how individuals overcome difficult situations. However, it is not only individuals who face difficulties; it is not uncommon for teams to experience adversity. When they do, they must be able to overcome these challenges without performance decrements.This manuscript represents a theoretical model that might be helpful in conceptualizing this important construct. Specifically, it describes team resilience as a second-order emergent state. We also include research propositions that follow from the model.

Introduction

In 1914, Sir Ernest Shackleton and his team set out from Plymouth, England on a quest to walk across the Antarctic continent. The goal was to be the first person to successfully cross the 1,500 miles of frozen tundra. Upon stopping at a whaling station as they set out on their quest, the team found itself stuck on ice. They spent nearly 11 months by the ice-bound ship, until the ice crushed it, eventually causing it to sink. After spending a week rowing in lifeboats, the team arrived at Elephant Island. The small island offered no protection or resources. Shackelton strategized, and devised a small subset of his team members to travel 800 miles back to the whaling station they previously left in order to seek help. After rowing for 17 days, they arrived, only to realize they were on the wrong side of the island. Approximately 22 miles of ice and mountains stood them and the whaling station. However, they managed to make it to their destination in 36 h. Given the ice and storms, it took Shackleton nearly 3 months to rescue the remaining men on Elephant Island. More than 2 years after leaving Plymouth port, all of the men had finally returned. The story of Shackleton story is so compelling due to the resilience he and his team members displayed. While it took more than 2 years, everyone returned home safely due to the resilience displayed by Shackleton and his team.

Why Is Team Resilience Important?

Resilience has been recognized as an important phenomenon for understanding how individuals overcome difficult situations (Masten and Osofsky, 2010). However, it is not only individuals who face difficulties; it is not uncommon for teams to experience adversity. When they do, they must be able to overcome these challenges without performance decrements. Indeed, research has identified a multitude of stressors that teams often face, including: poor interaction quality, poor communication channels, lack of back-up behavior, and negative organizational culture. While these stressors have been identified, the exploration of how teams can utilize their collective resources to overcome them has been largely overlooked. However, focus on resilience has recently grown, as researchers attempt to identify how teams and groups positively adapt to adversity (West et al., 2009; Bennett et al., 2010; Morgan et al., 2013, 2015; Alliger et al., 2015). It appears as though team resilience is a critical team level capacity that facilitates the rebound of teams after an adverse event. In light of this definition of resilience as a capacity, resilience can be seen as a buildable capacity. Teams that thrive, rebound, or positively adapt to adversity are more unlikely to experience the deleterious effects of challenging situations.

Definitions of Resilience

The term resilience comes from the Latin word “resiliere,” which means to “bounce back”; it typically refers to the ability to recover or rebound after a setback (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012). Indeed, the concept of resilience has been deemed an important phenomenon for understanding how successful adaptation occurs following an unanticipated—often negative—event (Wright and Masten, 2015). Interest in studying resilience as a coping or adaptation mechanism has increased rapidly over the last 20 years, and is considered across a variety of contexts, such as communities (Brennan, 2008), teams (Pollock et al., 2003), education (Gu and Day, 2007), organizations (Riolli and Savicki, 2003), military (Palmer, 2008), and athletic performance (Galli and Vealey, 2008).

As interest in resilience rises, a number of definitions and conceptualizations have been put forth in the literature. Not surprisingly, one of the primary shortcomings of previous resilience research is the wide discrepancy regarding its definition and conceptualization (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012). More specifically, resilience has been referred to sometimes as a trait, other times as a process, and yet other times as an outcome. Davydov et al. (2010) assert that these discrepancies and definitional confusion have hindered the evaluation and validity of resilience research findings. To complicate matters further, resilience has been studied at different levels of analysis. Traditionally, resilience has been used to refer to individuals, but more recently has been applied to teams and organizations. The sections that follow define resilience as it has been used at these various levels.

Resilience as a Process

Resilience researchers have shifted to examining resilience as a dynamic process, rather than an enduring trait. As a fluid process, some have proposed that resilience gradually develops over time, through interactions between the individual and the environment (Egeland et al., 1993). Most scholars agree that within the process, there is a complex interaction of multiple factors that determines whether resilience is demonstrated.

In line with the notion of resilience as a process, Galli and Vealey (2008) found that a significant facet is agitation, a process in which unpleasant emotions or mental struggles are countered through various coping strategies. Notably, positive adaptation occurs gradually, and requires frequent shifts of thought. These findings can be nested within the context of contemporary stress and emotion theory, which suggests that individuals construe relational meanings based on their interactions in a given environment (Lazarus, 1998). Similarly, a recent theoretical model offering insight into resilience is the “Meta-Model of Stress, Emotions, and Performance” (Richardson, 2002). The model suggests that suggests that stressors are created in the environment, become mediated by perception, appraisal, attribution, and coping, and finally, result in adaptive or maladaptive stress responses. The relationship between these processes and responses are further moderated by situational and individual level characteristics, including self-esteem, positive affect, and self-efficacy (Schaubroeck et al., 1992; Ganster and Schaubroeck, 1995; Schaubroeck and Merritt, 1997). These characteristics affect stress processes at several points, including stressor appraisal, meta-cognition in response to affect, and coping strategy selection.

Other researchers have also emphasized the role of stressors in the development of team resilience. For example, Meneghel et al. (2016) emphasize the role of job demands in the development of team resilience. However, their data indicate that there is a more complex relationship between job demands, resources, resilience, and performance than one might expect. More specifically, job demands may induce stress and thereby hamper positive emotions, thereby decreasing team resilience. However, when job demands do not place too much workload on team members, this may lead to a sense of accomplishment, thereby inducing positive emotion and the facilitation of resilience.

In his work, Richardson (2002) defines resilience as “the process of coping with stressors, adversity, change or opportunity in a manner that results in the identification, fortification, and enrichment of resilient qualities or protective factors” (p. 308). According to the theory, the process of resilience begins at the state of “biopsychospiritual homeostasis” (i.e., a comfort zone), in which an individual is physically, mentally, and spiritually in balance. This state is disrupted if an individual does not have sufficient protective factors to buffer strains, stresses, or adverse events. Over time, an individual will adjust and begin the process of reintegration. The reintegration process results in one of four outcomes: (1) resilient reintegration (additional protective factors are attained or strengthened, and homeostasis is once again achieved) (2) homeostatic reintegration (an individual remains in homeostasis, just “getting past” the situation), (3) reintegration with loss (protective factors are lost, and a lower level of homeostasis is achieved), or (4) dysfunctional reintegration (individuals resort to destructive behaviors) (Richardson, 2002).

Morgan and his colleagues point out that team resilience also has elements of a developmental process (Morgan et al., 2015). They conducted a narrative analysis of world-class rugby players. The results of this analysis suggest that team resilience might be developed during different phases of the team's development. For example, early development of resilience might be characterized by behaviors designed to increase collective efficacy. However, more mature teams focused on dealing with failures.

As previously noted, the notion of resilience as a process has also been well-developed at the organizational level. According to this body of work, resilient organizations treat deviations from boundary conditions indicators of overall system health. Resilient organizations behave as high reliability organizations (HROs). These organizations overcome adversity with few to no errors due to their “intelligent wariness” (Reason, 2000) and a “preoccupation with failure” (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2006). Resilient organizations intentionally test their risk assumptions and assumptions regarding overall system health (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2006). Furthermore, highly resilient organizations empower their employees to speak up to report errors or conditions that could foster errors. These organizations recognize that speaking up is critical, even if production is halted to mitigate a foreseeable potential error. Moreover, resilient organizations believe they have the capability to cope with a plethora of stressors, and continuously strive to strengthen their resources to do so. Therefore, resilient organizations acknowledge that they are imperfect, but believe they can grow by learning from near events and actual events (Woods, 2006). While this work has been conducted at the organizational (rather than team) level, given that this is the most well-developed area of resilience research, we believe this work can be translated into lessons for building team resilience. For example, given that resilient organizations encourage speaking up to report errors and are capable of handling high amounts of stress, incorporating techniques to encourage communication and cope with stress into team training may be key to facilitating resilience at the team level.

Resilience also requires practices that facilitate competence, and encourage growth to buffer against jolts and strains (Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007). Such capabilities facilitate resilience by expanding informational inputs, creating flexibility, and reconfiguring resources. Teams have the ability to continuously grow and refine their capabilities, which in turns allow them to have greater predictive abilities, remain flexible, and buffer the detrimental effects typically associated with unexpected or negative events.

The resilience mechanisms outlined above result from and encourage a unique way of “seeing.” Organizations that are resilient are more likely to be composed of teams that are capable of elucidating weak signals through the monitoring of current operations. As such, these teams are better equipped to identify weak signals because of their highly developed response capabilities, which allow them to respond more adaptively to a great array of events. Moreover, given their superior information processing systems and management, disruptive or negative events are treated as opportunities as opposed to threats (Jackson and Dutton, 1988; Barnett and Pratt, 2000). For example, teams in HROs use “near misses” to assess the overall functioning of the system and view them as opportunities for learning (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2006).

Moreover, teams in resilient organization tend to engage in mindful organizing (Weick et al., 2008). This entails the ongoing development and refinement of a shared understanding of problems faced by the organization and the resources and capabilities available to maintain safe performance. Vogus and Sutcliffe (2012) suggest that mindful organizing is the result of five processes: (1) assessment of possible and extant system risks, (2) questioning of previous assumptions, (3) discussion of individual, team, and organizational resources and abilities, (4) collective learning following an adverse event, and (5) deference to expertise. When employees engage in these processes, organizations are better equipped to identify errors in a timely manner, thereby minimizing detrimental outcomes.

Conceptualizing resilience as a dynamic process allows scientists to create hypotheses about the conditions and behaviors that lead to resilience. Viewing resilience as a process may be useful, as process theories “often deal with the evolution of relationships between individuals or team members, or with the cognitions and emotions of individuals as they interpret and react to events” (Langley, 1999, p. 693). As such, process theories often involve a plethora of quantitative and qualitative information. Although this can make interpretation and analysis quite difficult and complex (Langley, 1999), taking a process view allows us to more precisely parse out the components, events, and relationships underlying resilience.

Team Resilience as an Emergent State

Many team researchers have tended to focus on the construct of adaptability—in particular task adaptability (i.e., the ability to shift strategies in response to changing situational or task demands)—but these treatments may not capture the essence of resilience. Recently however, the notion that resilience is best considered an emergent state has been proposed (Maynard and Kennedy, 2016). The term emergent state was proposed by Marks et al. (2001) to describe certain types of team phenomena that were not actual processes (although they had been treated as such in prior work). According to Marks et al. (2001), “Emergent states describe cognitive, motivational, and affective states of teams, as opposed to the nature of their member interaction. Although researchers have not typically classified them as such, emergent states can be considered both team inputs and proximal outcomes. For example, teams with low cohesion (an emergent state) may be less willing to manage existing conflict (the process), which, in turn, may create additional conflict that lowers cohesion levels even further” (p. 357). The authors go on to clarify that emergent states are not actual team actions or interactions; rather, they should be viewed as an outcome of team experiences, including team processes.

Maynard and Kennedy (2016) view team resilience as an emergent state, given the idea that resilience is dynamic (Luthar et al., 2000) and is impacted by adaptation (among other team processes) (Moran and Tame, 2012). Reich et al. (2010) purport that resilience is the result of adaptation to difficulty, which is in line with the notion of team resilience as an emergent state. Similarly, conceptualizing resilience as an emergent state is in line with work that has defined it as “a team's belief that it can absorb and cope with strain, as well as a team's capacity to cope, recover and adjust positively to difficulties” (Carmeli et al., 2013, p. 149).

The manner by which various states emerge has been well-articulated in the context of team learning by Kozlowski and Bell (2008). Kozlowski and Bell (2008) suggest three central tenets of team learning. First, it is unquestionable that learning occurs within individuals. Next, while learning can occur at the individual-level, team learning occurs in a task and social context that shapes how learning occurs and what is learned. Finally, team learning is a dynamic process, occurring over repeated interactions over time, resulting in emergent outcomes suggesting that learning has taken place.

The value of the emergent state construct has been demonstrated empirically in recent team research. For example, Jehn and colleagues recently demonstrated that certain emergent states mediated the relationship between conflict and team performance (Jehn et al., 2008). Similar results were obtained by Bradley et al. (2012).

Employing Marks et al.'s (2001) definition, Maynard and Kennedy (2016) incorporated the concept of team resilience as an emergent state in a model of team adaptation. According to these authors, “the construct of resilience (at both the individual and team-level of analysis) has been viewed as a trait, a process, and as an outcome” (p. 8). They concluded, however, that team resilience is best thought of as an emergent state in the manner described by Marks et al. (2001). Team resilience as an emergent state suggests underlying dynamic properties that may shift as a result of team-level inputs, context, processes, and outcomes.

A similar position has been articulated by Sharma and Sharma (2016). These researchers sought to develop a measure of team resilience. A result of their scale development work was a model in which team resilience is a consequent of various latent variables comprised by more specific behaviors. While they did not invoke the construct of emergent states, their resulting model implies a multi-level process in the development of team resilience.

Our conclusion is similar: resilience is the result of a dynamic process that effects and is affected by other salient team variables. In fact, we argue that team resilience may be a “second-order”emergent state; that is an emergent state that is actually the result of other emergent states in the team. Indeed, team resilience may mediate the relationship between other team emergent states and outcomes during times of stress.

Individual Resilience

In regard to inputs at the individual level, there is growing research regarding how individual member qualities influence team adaptability (LePine, 2003, 2005). As an example, LePine (2005) revealed an interaction between the difficulty of a goal, and learning orientation. Teams that had difficult goals that consisted of team members with a learning orientation had higher rates of adaptation. As suggested by Maynard and Kennedy (2016) “We can envision more work at the team-level of analysis leveraging such individual-level work by either aggregating such individual-level constructs or by examining upward influence-type models (e.g., Mathieu and Taylor, 2007)” (p. 22).

Despite increased interest in resilience, there remains definitional debate regarding what exactly it means to be a resilient individual. More specifically, it is yet unclear whether resilient individuals thrive (i.e., grow beyond baseline functioning) or more simply adapt and return to baseline functioning after facing a setback. In line with the latter idea, Masten et al. (1990) define resilience as “The process of, capacity for, or outcome of adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances” (p. 426). Similarly, Lee and Cranford (2008) define resilience as “The capacity of individuals to cope successfully with significant change, adversity, or risk” (p. 213). However, other authors purport that resilience goes beyond adaptation to adversity. For example, Leipold and Greve (2009) define resilience as “An individual's stability or quick recovery (or even growth) under significant adverse conditions” (p. 41). Moreover, Connor and Davidson (2003) suggest that resilience is “The personal qualities that enables one to thrive in the face of adversity” (p. 76).

Despite this uncertainty, Fletcher and Sarkar (2013) pointed out that definitions of resilience are typically founded upon two fundamental notions: adversity and positive adaptation. In fact, researchers generally agree that positive adaption to adversity must be evident in order for resilience to be demonstrated. Luthar and Cicchetti (2000) asserted further that adversity “typically encompasses negative circumstances that are known to be statistically associated with adjustment difficulties” (p. 858). In addition, according to Davydov et al. (2010), the mechanisms underlying resilience vary, ranging from mild adversity (e.g., stress at work) to strong adversity (e.g., bereavement). Regarding the second underlying concept, positive adaptation “may be likened to a springboard that propels the survivor to a higher level of functioning than that which they held previously” (Linley and Joseph, 2004, p. 602). In line with this definition, positive adaptation therefore represents a gain following the adverse event, as opposed to recovery from the loss or homeostatic return to baseline.

Others (e.g., Luthar et al., 2000) suggest that positive adaptation simply refers to the ability to meet the demands faced during adversity. Furthermore, others assert that positive adaptation may be a combination of the previous definitions; Leipold and Greve (2009) suggest that positive adaptation refers to “An individual's stability or quick recovery (or even growth) under significant adverse conditions” (p. 41). Thus, the definitional debate in the resilience literature seems to surround the second core process of adaptation. Luthar and colleagues (Luthar et al., 2000; Luthar, 2006) suggest that positive adaptation may be a function of the severity of the adverse event, and what constitutes positive adaptation might be context specific.

Alongside definitional confusion, there has been considerable debate about the basic conceptualization of resilience. Although all people possess some degree of resilience, not everyone is equal in this regard. While some people have difficulty overcoming commonplace hassles, others react positively in the face of even the most challenging situations (Bonanno, 2004). In search of an explanation for this variance, early resilience researchers sought to identify factors that protect individuals from experiencing adverse effects after a setback. In this regard, resilience can be conceptualized as an amalgamation of protective factors, or traits, that “influence, modify, ameliorate, or alter a person's response to some environmental hazard that predisposes to a maladaptive outcome” (Rutter, 1985, p. 600). This conception was originally suggested by Block and Block (1980), using the term “ego resilience” to reflect traits such as resourcefulness, character, and flexibility. Those high on ego resilience were found to be energetic, optimistic, and had the ability to detach in order to problem solve (Block and Block, 1980). Since the origination of this work, there seems to be general agreement that the construct of resilience implies a protection against future stressors (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016).

Several specific protective factors have been examined by resilience researchers, including: positive emotions (Tugade and Fredrickson, 2004), hardiness (Bonanno, 2004), self-efficacy (Gu and Day, 2007), extraversion (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006), self-esteem (Kidd and Shahar, 2008), positive affect (Zautra et al., 2005), and spirituality (Bogar and Hulse-Killacky, 2006).

Team Resilience

Given the growth of teamwork within organizations, resilience researchers have recently shifted their focus from the individual and community levels to the team level (Norris et al., 2008; Alliger et al., 2015). As recently suggested by Brodsky et al. (2011), “a focus on the individual is not enough” (p. 233). In line with Alliger et al. (2015), we purport that individual and team resilience while related, are distinct constructs. A team comprised of resilient members does not necessarily make the team resilient. At the team level, resilience has been characterized by variables including collective efficacy, creativity, cohesion, social support, and trust (Gittell et al., 2006; Norris et al., 2008; Blatt, 2009). Moreover, teams that encompass a broader perspective in the face of adversity have a greater likelihood of positive adaption (Bennett et al., 2010). In support of the notion that team resilience research is critical, Bennett et al. (2010) purports that, “resilience may be viewed as much a social factor existing in teams as an individual trait” (p. 225). This would suggest that teams have the capacity for positive adaptation through collective interactions, rather than as isolated individuals. As stated by West et al. (2009), “Team resilience may prove to be an important positive team level capacity that aids in the repair and rebound of teams when facing potentially stressful situations. Teams which display the ability to either thrive under high liability situations, improvise and adapt to significant change or stress, or simply recover from a negative experience are less likely to experience the potentially damaging effects of threatening situations” (p. 254).

Organizational Resilience

As noted by Maynard and Kennedy (2016), research is lacking on the effect of organizational-level inputs on team resilience. Work by Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) have suggested organizational context to be a pre-cursor to team ambidexterity. More specifically, the more supportive the context, the greater the ambidexterity. Team ambidexterity “allows teams to reconcile the tensions between alignment and adaptability” (Maynard and Kennedy, 2016, p. 12). Moreover, Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) found that ambidexterity is a mediator between context and unit performance. Thus, the contextual inputs at the organizational level seem to facilitate unit adaptation.

As defined by Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007), resilience at the organizational level refers to the ability to maintain positive adjustment to difficult situations, such that the result is a stronger and more resourceful organization. Since organizations that are resilient as a whole have greater resources, this may allow their individual teams to also be more resilient as they have access to a greater repertoire of resources when faced with a difficult situation. “Difficult situations” include crises, unexpected events, deviations from boundary conditions (i.e., deviations from normal functioning), strains, and emerging risks. It is important to note that the amalgamation of small stresses, deviations, or interruptions can pose a significant risk to system functioning just as readily as a more catastrophic event (Rudolph and Repenning, 2002). Adjustment to adversity at the organizational level has been said to strengthen individual teams through “a hierarchical integration of behavioral systems whereby earlier structures are incorporated into later structures in increasingly complex forms” (Egeland et al., 1993, p. 518). Alternatively stated, resiling from difficult conditions necessitates the activation of latent resources. Therefore, resilience encompasses more than a specific adaption. Competence in the face of one adversity implies a greater likelihood of competence in the face of the next adversity. In order to be resilient, a team must be prepared for hardship, which requires an “improvement in overall capability, i.e., a generalized capacity to investigate, to learn, and to act, without knowing in advance what one will be called to act upon” (Wildavsky, 1991, p. 70). In this light, resilience greatly depends on learning from previous experiences and adversities which facilitates future learning. However, because resilience is independent of learning activities, it represents a greater repertoire of capabilities.

Several resilience processes at the organization level have been identified by Brodsky et al. (2011), which include: a sense of community, positive team culture, reframing of stressors, striving to achieve the organization's mission, shared values, and malleable team structures (Fletcher and Wagstaff, 2009; Wagstaff et al., 2012). This supports the contention of Chan (1998), who suggested that although constructs may fall under the same domain, they manifest differently at different levels (i.e., individual or team). A similar position has been advocated more recently by Morgan et al. (2013).

An Input-Mediator-Outcome (IMO) Model of Team Resilience

What follows is our attempt to synthesize past work to create a model of team resilience by employing a modified Input-Process-Outcome (I-P-O) framework advocated by Ilgen et al. (2005): the Input-Mediator-Output-Input (I-M-O-I) framework. According to Ilgen et al. traditional I-P-O models failed to account for the dynamic complexity that characterizes team behavior. Using Marks et al.'s (2001) notion of emergent state described above, they substitute the term “mediator” for “process” in the original I-P-O framework. In doing so, these authors contend that it “reflects the broader range of variables that are important mediational influences with explanatory power for explaining variability in team performance and viability,” (Ilgen et al., 2005, p. 520). The following sections first summarize past work into the inputs, processes and mediators, and outcomes associated with resilience as the individual, team, and organizational levels. We included the individual levels in our review because they are part of the dynamic system that effects team resilience. Our contention is that it is essential to maintain this multi-level view in order to understand the full complexity of team performance and outcomes. Based on this review, we conclude by offering a comprehensive model of those things that contribute to development of resilience and outcomes that can be expected as a result of achieving resilience. We hope this model will stimulate further thinking and research.

Beginning with the End: Defining Outcomes of Resilience

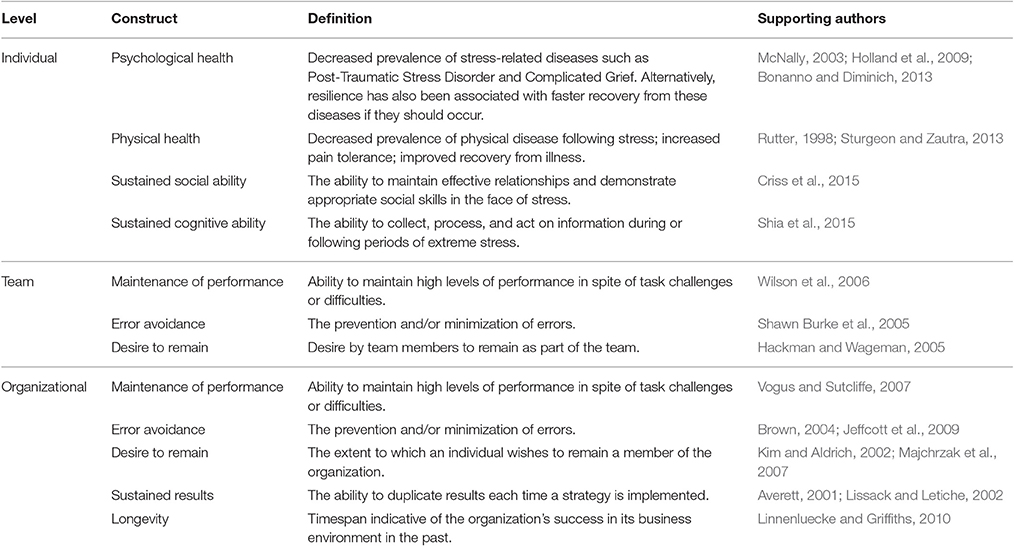

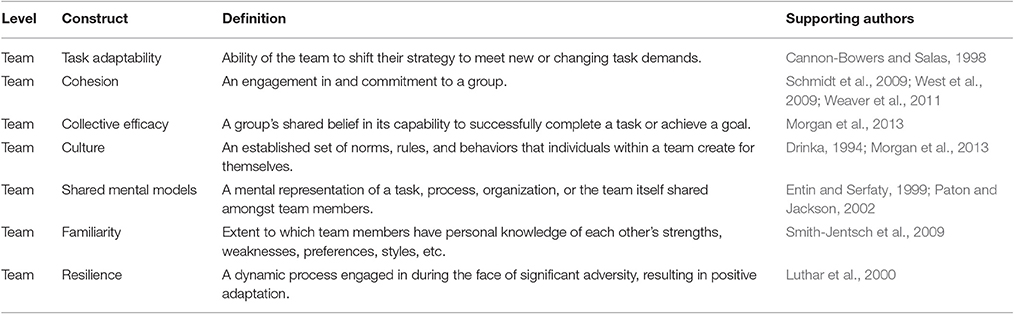

To begin specification of an I-M-O model of resilience, we reviewed literature summarizing the outcomes that are expected to result from resilient behavior. Our goal here is to synthesize what has been theorized about the expected outcomes of resilience at the individual, team and organizational levels (see Table 1). Implicit in all of these outcomes is that they must occur during a period of stress that is sufficient to interrupt performance.

Defining Inputs of Resilience

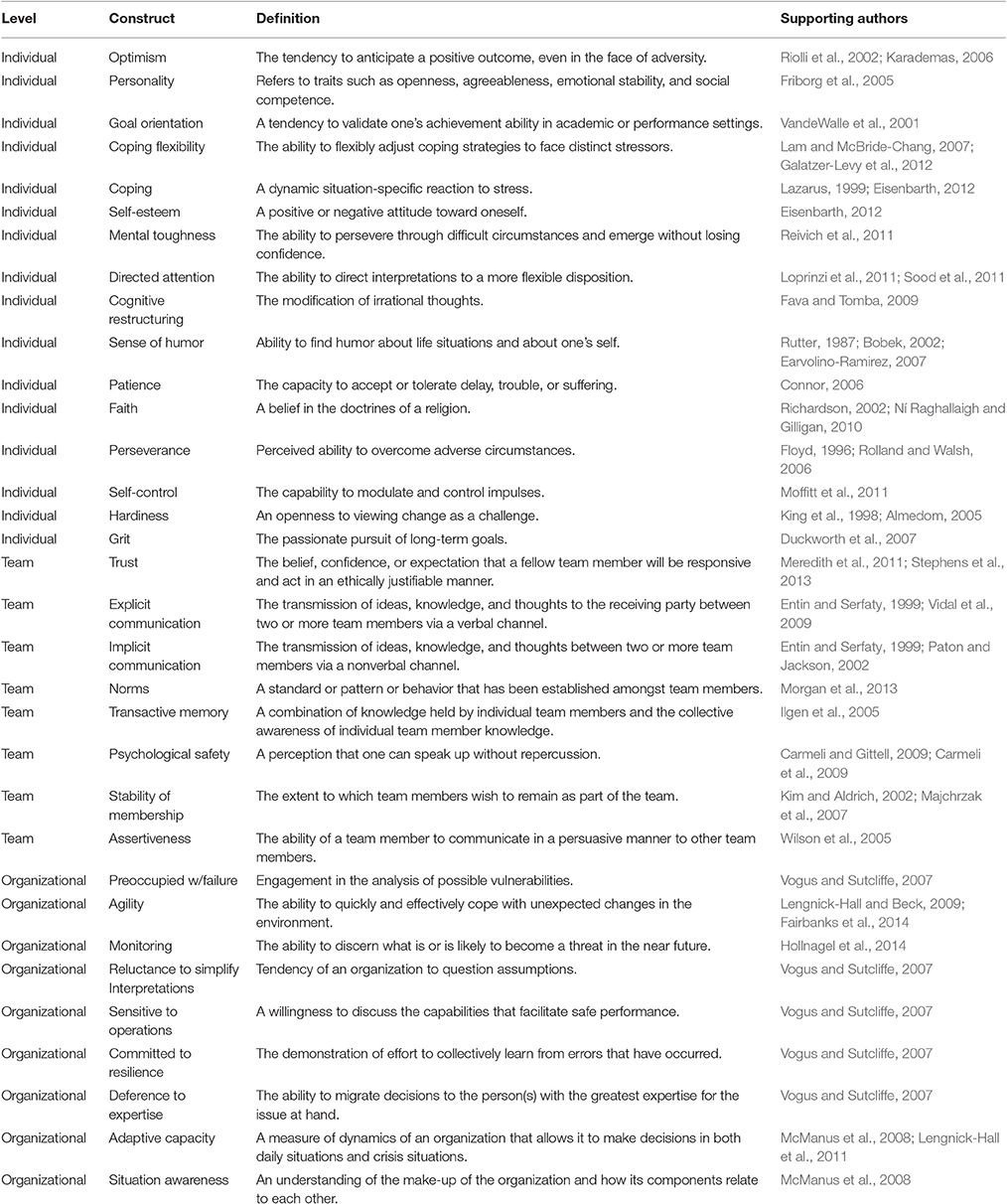

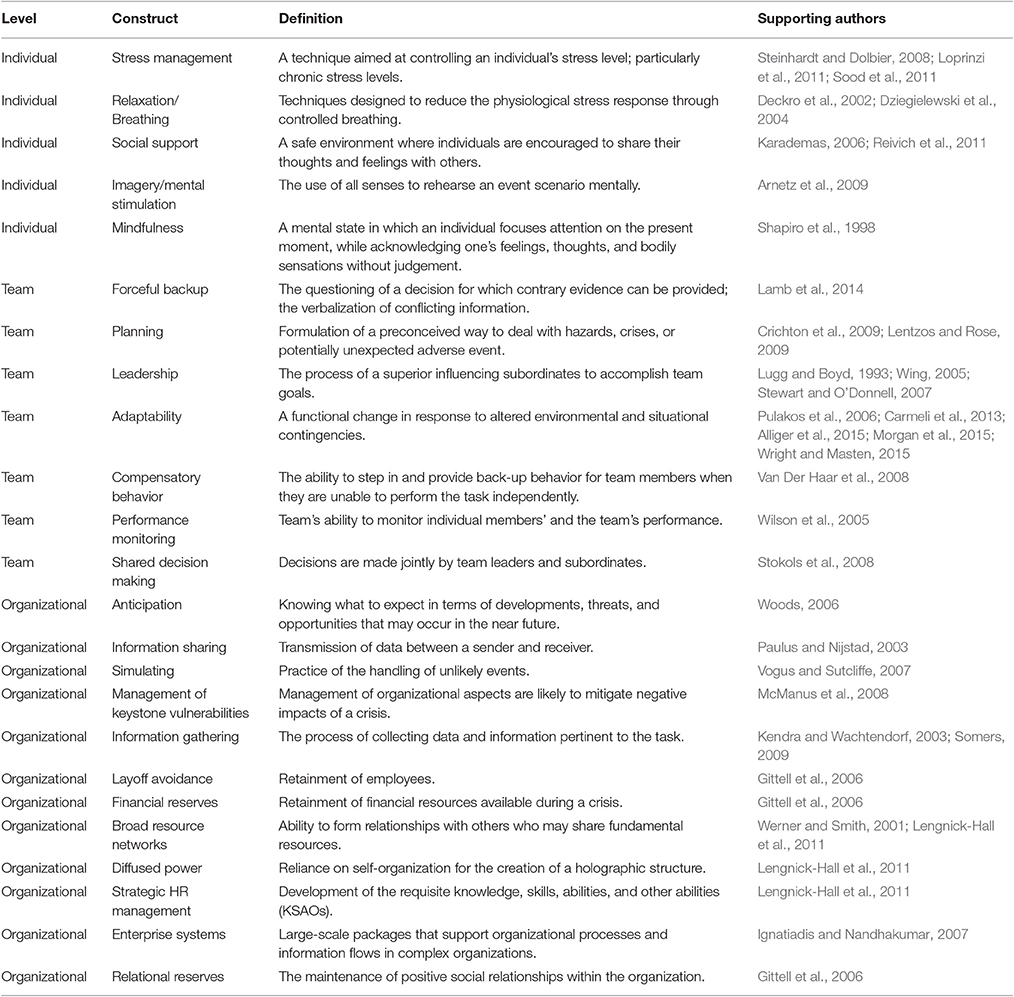

The inputs to resilience vary greatly depending on the level at which it is being considered. Table 2 summarizes the major inputs that enable resilience, again ordered by whether they occur at the individual, team, or organizational level. At the individual level, inputs to resilient behavior are most often considered to be individual traits. These traits serve to buffer individuals to the effects of a stressor and/or allow him or her to bounce back quickly. At the team level, inputs to resilience are not traits, rather they are factors that exist at the team level. However, they operate in a similar manner to individual inputs in that they can have a buffering effect on the team's experience of stress and/or equip them to cope with the stress. Finally, at the organizational level, input factors are similar to team-level inputs in that they exist at the organizational level and serve to set the stage for coping behaviors by the organization.

Processes Associated with Resilience

Similar to input factors, the processes associated with resilience behavior vary greatly depending on the level being considered. At the individual level, resilient processes are most often conceived of as adaptive behaviors. At the team and organizational levels, resilient processes are more closely associated with collective behavior by team members. Table 3 summarizes our review of the literature regarding processes associated with resilience.

A Comprehensive Model of Team Resilience

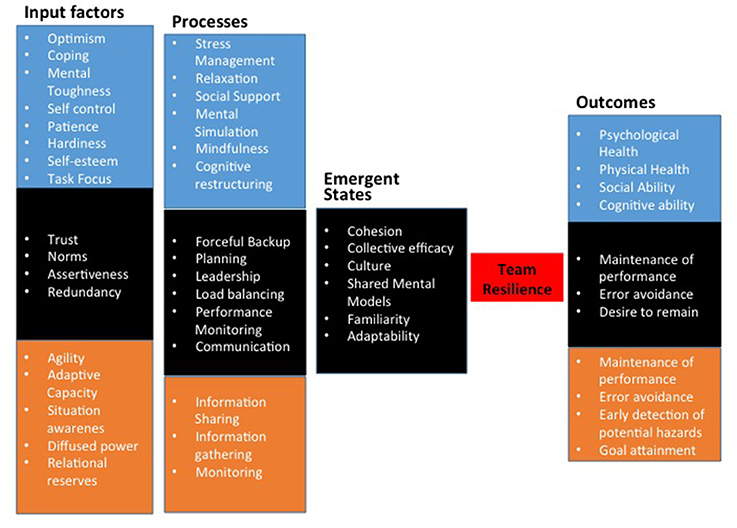

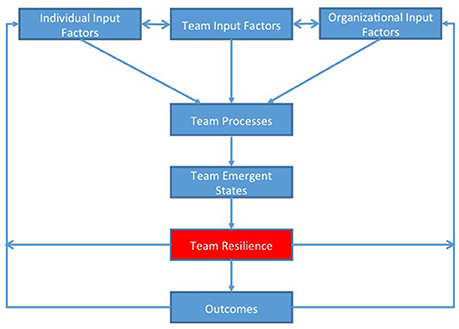

Figure 1 displays a summary of the variables included in the tables above. As noted previously, we conceptualize team resilience as a second order mediator. That is, team resilience is best thought of as enabled by a combination of other team emergent states including cohesion, collective efficacy, culture, shared mental models, familiarity, and adaptability (see Table 4). Our conclusion is based on the notion that resilience is the result of these other states and it enables the team to achieve either positive or negative outcomes. It is this quality of resilience that is unique in that it can act as a buffer for negative outcomes and also as an enabler of positive ones.

Inspection of the model in Figure 2 reflects what we have discussed above. According to this model, team resilience is a second order emergent state that is situated between other team emergent states (see Figure 1) and outcomes (see Figure 1). Team emergent states are the result of various team processes (see Figure 1) and those, in turn, are driven by input factors at the individual, team, and organizational level. We believe that this conceptualization is reflective of the complex, multi-level, dynamic relationship among variables at the team level.

Research Directions

The construct of emergent states allows researchers to propose hypotheses that better represent the dynamic, evolving nature of team processes and performance. However, given that this is a relatively new approach, empirical research to identify key emergent states is in its infancy. As this theoretical position is articulated, and as we develop new statistical tools to allow us to validate these models, we are learning more about the complex nature of team processes and the psychological states that result from team interactions.

In this paper, we have suggested a “second-order” emergent state of team resilience which might help us to understand how certain teams are able to cope with extreme stressors and to maintain their performance. More specifically, as an emergent state, this suggests that resilience may be the result of a number of team actions or processes, rather than a process in it of itself. Additionally, given the process vs. state debate in the literature, the nature of the construct of team resilience is certainly unclear. Thus, a new conceptualization of team resilience is warranted. As articulated throughout the present work, viewing team resilience as an emergent state may offer insight into the nature of team resilience that prior conceptualizations have failed to achieve. Ultimately, this is a hypothesis that will need to be validated using modeling approaches. However, it is important to articulate specific relationships that will be the foundation of these models. To that end, we propose the following first-order emergent states that we hypothesize will be related to the second-order emergent state of team resilience.

1. Collective Efficacy: Collective efficacy is typically defined as the team shared belief that it possesses the capability to achieve its goal. The relationship between collective efficacy and team performance has been demonstrated several times (see Gully et al., 2002, for a review). Collective efficacy is thought to work by influencing the amount of effort that team members are willing to invest and the degree of frustration they are willing to tolerate in pursuing team goals (Gully et al., 2002). These mechanisms are likely to be particularly important during times of high stress (Jex and Gudanowski, 1992). Therefore, we hypothesize that the emergence of collective efficacy will be positively related to team resilience. This position is supported by the results of Sharma and Sharma (2016) who included collective efficacy as a latent factor in their measurement model of team resilience. Similar support was reported by Morgan et al. (2013).

2. Team Cohesion: Similar to collective efficacy, team cohesion is an attitudinal state that is related to the degree to which team members value being in the team and their commitment to remaining in the team. Although, team cohesion is thought to also exert its influence through motivation, research has indicated that it is likely a different construct than collective efficacy (Paskevich et al., 1999). Specifically, team cohesion may influence performance through elements of mutual trust and the acceptance of, and adherence to, group norms (Carron et al., 2002). Adherence to group norms is an element that is thought to be a critical element in maintaining team performance under periods of high stress (Stevens et al., 2015). Cohesion is often included in theories of team resilience (Hind et al., 1996; Meredith et al., 2011). For example, Morgan et al. (2013) describe it as an element of collective efficacy. However, we might argue that it is better included in their construct of group identity. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to suggest that cohesion is related to the emergence of resilience.

3. Shared Mental Models: Shared mental models have been defined as a collective representation of a task, process, organization, or team (Entin and Serfaty, 1999). Shared mental models have been linked to team performance under stress because they allow team members to coordinate their activities with the cognitive load of overt communication (Rouse et al., 1992). Several empirical studies have indicated the importance of shared mental models in allowing teams to maintain their performance when confronted with stress (e.g., Bolstad and Endsley, 1999; Stout et al., 1999; Mathieu et al., 2000). Interestingly, the emergence of shared mental models is rarely considered in theories of team resilience. However, the empirical data suggest that they may be a critical first-order emergent state.

4. Team Adaptability: Team adaptability refers to the ability of the team to recognize that a given strategy is not working and to adapt their strategy to meet the new demands (Cannon-Bowers and Salas, 1998). Team adaptability encompasses a number of behaviors and abilities that involve monitoring, problem-solving, and so forth. In fact, team adaptability is frequently used interchangeably with resilience in the lay literature. While similar, there are a few notable differences. First, we argue that adaptability is an emergent state that allows team members to perform in the short-term, whereas resilience allows them to grow and develop to facilitate performance in the longer term. Secondly, adaptive expertise has been defined as the ability to invent new procedures and make novel predictions based on extant knowledge (Hatano and Inagaki, 1986). Adaptation is considered to be evidenced when the individual responds successfully to changes in the task (Smith et al., 1997). However, resilience is typically demonstrated in response to adverse (rather than simply novel) events. It is a complex process comprised of processes whereby team members use their individual and collective resources to protect the group from stressors and positively respond when faced with adversity. As such, because resilience is independent of learning activities, it represents a greater repertoire of capabilities than adaptability alone. Finally, unlike the work on adaptability by Kozlowski and colleagues (e.g., Kozlowski et al., 1999, 2009) which places critical importance on the team leader, resilience also focuses on team development without emphasizing any particular team member. Instead, resilience work tends to place equal importance across all team members. In contrast, work by Kozlowski and colleagues places emphasis on how team leaders must build team capabilities. In particular, they note that planning and organizing, monitoring and acting are “executive leadership functions.” In the realm of resilience work, these tasks are also critical but equally distributed across team members. That said, there is no question that adaptability is a critical emergent state for the development of team resilience.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alliger, G. M., Cerasoli, C. P., Tannenbaum, S. I., and Vessey, W. B. (2015). Team resilience. Organ. Dyn. 44, 176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.05.003

Almedom, A. M. (2005). Resilience, hardiness, sense of coherence, and posttraumatic growth: all paths leading to “light at the end of the tunnel”? J. Loss Trauma 10, 253–265. doi: 10.1080/15325020590928216

Arnetz, B. B., Nevedal, D. C., Lumley, M. A., Backman, L., and Lublin, A. (2009). Trauma resilience training for police: psychophysiological and performance effects. J. Police Crimin. Psychol. 24, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11896-008-9030-y

Barnett, C. K., and Pratt, M. G. (2000). From threat-rigidity to flexibility-Toward a learning model of autogenic crisis in organizations. J. Organ. Change Manage. 13, 74–88. doi: 10.1108/09534810010310258

Bennett, J. B., Aden, C. A., Broome, K., Mitchell, K., and Rigdon, W. D. (2010). Team resilience for young restaurant workers: research-to-practice adaptation and assessment. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 15:223. doi: 10.1037/a0019379

Blatt, R. (2009). Resilience in entrepreneurial teams: developing the capacity to pull through. Front. Entrepreneurship Res. 29, 1–14.

Block, J. H., and Block, J. (1980). “The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior,” in Development of Cognition, Affect, and Social Relations: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology, Vol. 13 (Minneapolis), 39–101.

Bobek, B. L. (2002). Teacher resiliency: a key to career longevity. Clear. House 75, 202–205. doi: 10.1080/00098650209604932

Bogar, C. B., and Hulse-Killacky, D. (2006). Resiliency determinants and resiliency processes among female adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J. Counsel. Dev. 84, 318–327. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00411.x

Bolstad, C. A., and Endsley, M. R. (1999). “Shared mental models and shared displays: An empirical evaluation of team performance,” in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Vol. 43 (Sage, CA; Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications), 213–217.

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 59, 20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Bonanno, G. A., and Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual Research Review: positive adjustment to adversity–trajectories of minimal–impact resilience and emergent resilience. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 54, 378–401. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12021

Bradley, B. H., Postlethwaite, B. E., Klotz, A. C., Hamdani, M. R., and Brown, K. G. (2012). Reaping the benefits of task conflict in teams: the critical role of team psychological safety climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 97:151. doi: 10.1037/a0024200

Brennan, M. A. (2008). Conceptualizing resiliency: an interactional perspective for community and youth development. Child Care Pract. 14, 55–64. doi: 10.1080/13575270701733732

Brodsky, A. E., Welsh, E., Carrillo, A., Talwar, G., Scheibler, J., and Butler, T. (2011). Between synergy and conflict: balancing the processes of organizational and individual resilience in an Afghan women's community. Am. J. Community Psychol. 47, 217–235. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9399-5

Brown, A. B. (2004). Oops! coping with human error in it systems. Queue 2, 34–41. doi: 10.1145/1036474.1036497

Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., and Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001

Cannon-Bowers, J. A., and Salas, E. (1998). Team performance and training in complex environments: recent findings from applied research. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 7, 83–87. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10773005

Carmeli, A., and Gittell, J. H. (2009). High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 30, 709–729. doi: 10.1002/job.565

Carmeli, A., Brueller, D., and Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: the role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 26, 81–98. doi: 10.1002/sres.932

Carmeli, A., Friedman, Y., and Tishler, A. (2013). Cultivating a resilient top management team: the importance of relational connections and strategic decision comprehensiveness. Saf. Sci. 51, 148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2012.06.002

Carron, A. V., Bray, S. R., and Eys, M. A. (2002). Team cohesion and team success in sport. J. Sports Sci. 20, 119–126. doi: 10.1080/026404102317200828

Chan, D. (1998). Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: a typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol. 83:234. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.234

Connor, K. M. (2006). Assessment of resilience in the aftermath of trauma. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 46–49.

Connor, K. M., and Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 18, 76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

Crichton, M. T., Ramsay, C. G., and Kelly, T. (2009). Enhancing organizational resilience through emergency planning: learnings from cross-sectoral lessons. J. Contingencies Crisis Manage. 17, 24–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00556.x

Criss, M. M., Henry, C. S., Harrist, A. W., and Larzelere, R. E. (2015). Interdisciplinary and innovative approaches to strengthening family and individual resilience: an introduction to the special issue. Fam. Relat. 64, 1–4. doi: 10.1111/fare.12109

Davydov, D. M., Stewart, R., Ritchie, K., and Chaudieu, I. (2010). Resilience and mental health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 479–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003

Deckro, G. R., Ballinger, K. M., Hoyt, M., Wilcher, M., Dusek, J., Myers, P., et al. (2002). The evaluation of a mind/body intervention to reduce psychological distress and perceived stress in college students. J. Am. College Health 50, 281–287. doi: 10.1080/07448480209603446

Drinka, T. J. (1994). Interdisciplinary geriatric teams: approaches to conflict as indicators of potential to model teamwork. Educ. Gerontol. 20, 87–103. doi: 10.1080/0360127940200107

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., and Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 1087–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Dziegielewski, S. F., Turnage, B., and Roest-Marti, S. (2004). Addressing stress with social work students: a controlled evaluation. J. Soc. Work Educ. 40, 105–119.

Earvolino-Ramirez, M. (2007). Resilience: a concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 42, 73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2007.00070.x

Egeland, B., Carlson, E., and Sroufe, L. A. (1993). Resilience as process. Dev. Psychopathol. 5, 517–528. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006131

Eisenbarth, C. (2012). Coping profiles and psychological distress: a cluster analysis. N. Am. J. Psychol. 14, 485–496.

Entin, E. E., and Serfaty, D. (1999). Adaptive team coordination. Hum. Factors 41, 312–325. doi: 10.1518/001872099779591196

Fairbanks, R. J., Wears, R. L., Woods, D. D., Hollnagel, E., Plsek, P., and Cook, R. I. (2014). Resilience and resilience engineering in health care. Joint Commiss. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 40, 376–383. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(14)40049-7

Fava, G. A., and Tomba, E. (2009). Increasing psychological well-being and resilience by psychotherapeutic methods. J. Pers. 77, 1903–1934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00604.x

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 13, 669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.007

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience. A review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. Eur. Psychol. 18, 12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: an evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. J. Sport Psychol. Act. 7, 135–157. doi: 10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

Fletcher, D., and Wagstaff, C. R. (2009). Organizational psychology in elite sport: its emergence, application and future. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 10, 427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.03.009

Floyd, C. (1996). Achieving despite the odds: a study of resilience among a group of african american high school seniors. J. Negro Educ. 65, 181–189. doi: 10.2307/2967312

Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., and Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 14, 29–42. doi: 10.1002/mpr.15

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Burton, C. L., and Bonanno, G. A. (2012). Coping flexibility, potentially traumatic life events, and resilience: a prospective study of college student adjustment. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 31, 542–567. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2012.31.6.542

Galli, N., and Vealey, R. S. (2008). Bouncing back” from adversity: athletes' experiences of resilience. Sport Psychol. 22, 316–335. doi: 10.1123/tsp.22.3.316

Ganster, D., and Schaubroeck, J. (1995). “The moderating effects of self-esteem on the work stress-employee health relationship,” in Occupational Stress: A Handbook, eds R. Crandall and P. Perrewe (Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis), 167–177.

Gibson, C. B., and Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Acad. Manage. J. 47, 209–226. doi: 10.2307/20159573

Gittell, J. H., Cameron, K., Lim, S., and Rivas, V. (2006). Relationships, layoffs, and organizational resilience airline industry responses to September 11. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 42, 300–329. doi: 10.1177/0021886306286466

Gu, Q., and Day, C. (2007). Teachers resilience: a necessary condition for effectiveness. Teach. Teacher Educ. 23, 1302–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.006

Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., and Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 87:819. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.819

Hackman, J. R., and Wageman, R. (2005). A theory of team coaching. Acad. Manage. Rev. 30, 269–287. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2005.16387885

Hatano, G., and Inagaki, K. (1986). “Two courses of expertise,” in Child Development and Education in Japan, eds H. W. Stevenson and H. Azuma (New York, NY: W.H. Freeman Co), 262–272.

Hind, P., Frost, M., and Rowley, S. (1996). The resilience audit and the psychological contract. J. Manager. Psychol. 11, 18–29. doi: 10.1108/02683949610148838

Holland, J. M., Neimeyer, R. A., Boelen, P. A., and Prigerson, H. G. (2009). The underlying structure of grief: a taxometric investigation of prolonged and normal reactions to loss. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 31, 190–201. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9113-1

Hollnagel, E., Fairbanks, R. J., Wears, R., Woods, D. D., Plsek, P., and Cook, R. (2014). Resilience and resilience engineering in health care. Joint Commiss. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 40, 376–383. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(14)40049-7

Ignatiadis, I., and Nandhakumar, J. (2007). The impact of enterprise systems on organizational resilience. J. Inform. Technol. 22, 36–43. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000087

Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., and Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: from input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 517–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070250

Jackson, S. E., and Dutton, J. E. (1988). Discerning threats and opportunities. Adm. Sci. Q. 370–387. doi: 10.2307/2392714

Jeffcott, S. A., Ibrahim, J. E., and Cameron, P. A. (2009). Resilience in healthcare and clinical handover. Qual. Saf. Health Care 18, 256–260. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.030163

Jehn, K. A., Greer, L., Levine, S., and Szulanski, G. (2008). The effects of conflict types, dimensions, and emergent states on group outcomes. Group Decis. Negotiat. 17, 465–495. doi: 10.1007/s10726-008-9107-0

Jex, S. M., and Gudanowski, D. M. (1992). Efficacy beliefs and work stress: an exploratory study. J. Organ. Behav. 13, 509–517. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130506

Karademas, E. C. (2006). Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: the mediating role of optimism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 40, 1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.019

Kendra, J. M., and Wachtendorf, T. (2003). Elements of resilience after the world trade center disaster: reconstituting New York City's Emergency Operations Centre. Disasters 27, 37–53. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00218

Kidd, S., and Shahar, G. (2008). Resilience in homeless youth: the key role of self-esteem. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 78, 163–172. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.2.163

Kim, P. H., and Aldrich, H. E. (2002). “Teams that work together, stay together: Resiliency of entrepreneurial teams,” in Babson College, Babson Kauffman Entrepreneurship Research Conference, Vol. 2006 (Wellesley, MA: BKERC), 1–5.

King, L. A., King, D. W., Fairbank, J. A., Keane, T. M., and Adams, G. A. (1998). Resilience–recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 420–434. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.420

Kozlowski, S. W. J., and Bell, B. S. (2008). “Team learning, development, and adaptation,” in Work Group Learning, eds V. I. Sessa and M. London (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 15–44.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., Nason, E. R., and Smith, E. M. (1999). “Developing adaptive teams: A theory of compilation and performance across levels and time,” in The Changing Nature of Work Performance: Implications for Staffing, Personnel Actions, and Development, eds D. R. Ilgen and E. D. Pulakos (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 240–292.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Watola, D., Jensen, J. M., Kim, B., and Botero, I. (2009). “Developing adaptive teams: A theory of dynamic team leadership,” in Team Effectiveness in Complex Organizations: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives and Approaches, eds E. Salas, G. F. Goodwin, and C. S. Burke (New York, NY: Routledge Academic), 109–146.

Lam, C. B., and McBride-Chang, C. A. (2007). Resilience in young adulthood: the moderating influences of gender-related personality traits and coping flexibility. Sex Roles 56, 159–172. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9159-z

Lamb, C., Lamb, J., Stevens, R., and Caras, A. (2014). “Team behaviors and cognitive cohesion in complex situations.,” in Foundations of Augmented Cognition. Advancing Human Performance and Decision-Making through Adaptive Systems, eds D. D. Schmorrow and C. M. Fidopiastis (Crete: Springer International Publishing), 136–147.

Lazarus, R. S. (1998). From psychological stress to the emotions: a history of changing outlooks. Personality 4, 179–201.

Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Hope: an emotion and a vital coping resource against despair. Soc. Res. 66, 653–678.

Lee, H. H., and Cranford, J. A. (2008). Does resilience moderate the associations between parental problem drinking and adolescents' internalizing and externalizing behaviors?: a study of Korean adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 96, 213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.007

Leipold, B., and Greve, W. (2009). Resilience: a conceptual bridge between coping and development. Eur. Psychol. 14, 40–50. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.40

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., and Beck, T. E. (2009). Resilience Capacity and Strategic Agility: Prerequisites for Thriving in a Dynamic Environment. UTSA, College of Business.

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., and Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 21, 243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001

Lentzos, F., and Rose, N. (2009). Governing insecurity: contingency planning, protection, resilience. Econ. Soc. 38, 230–254. doi: 10.1080/03085140902786611

LePine, J. A. (2003). Team adaptation and postchange performance: effects of team composition in terms of members' cognitive ability and personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 88:27. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.27

LePine, J. A. (2005). Adaptation of teams in response to unforeseen change: effects of goal difficulty and team composition in terms of cognitive ability and goal orientation. J. Appl. Psychol. 90:1153. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1153

Linley, P. A., and Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J. Trauma. Stress 17, 11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

Linnenluecke, M. K., and Griffiths, A. (2010). Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 45, 357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2009.08.006

Lissack, M. R., and Letiche, H. (2002). Complexity, emergence, resilience, and coherence: gaining perspective on organizations and their study. Emerg. A J. Complex. Issues Organ. Manage. 4, 72–94. doi: 10.1207/S15327000EM0403-06

Loprinzi, C. E., Prasad, K., Schroeder, D. R., and Sood, A. (2011). Stress Management and Resilience Training (SMART) program to decrease stress and enhance resilience among breast cancer survivors: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin. Breast Cancer 11, 364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.06.008

Lugg, C. A., and Boyd, W. L. (1993). Leadership for collaboration: reducing risk and fostering resilience. Phi Delta Kappan 75, 253–258.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). “Resilience in development: a synthesis of research across five decades,” in Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, eds D. Cicchetti and D. J. Cohen (New York: Wiley), 739–795.

Luthar, S. S., and Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 12, 857–885. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004156

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., and Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 71, 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

Majchrzak, A., Jarvenpaa, S. L., and Hollingshead, A. B. (2007). Coordinating expertise among emergent groups responding to disasters. Organ. Sci. 18, 147–161. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0228

Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., and Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Acad. Manage. Rev. 26, 356–376. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2001.4845785

Masten, A. S., and Osofsky, J. D. (2010). Disasters and their impact on child development: introduction to the special section. Child Dev. 81, 1029–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01452.x

Masten, A. S., Best, K. M., and Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Dev. Psychopathol. 2, 425–444. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005812

Mathieu, J. E., and Taylor, S. R. (2007). A framework for testing meso-mediational relationships in Organizational Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 28, 141–172. doi: 10.1002/job.436

Mathieu, J. E., Heffner, T. S., Goodwin, G. F., Salas, E., and Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2000). The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 85:273. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.2.273

Maynard, M. T., and Kennedy, D. M. (2016). Team Adaptation and Resilience: What Do We Know and What Can be Applied to Long-Duration Isolated, Confined, and Extreme Contexts. Houston, TX: National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

McManus, S., Seville, E., Vargo, J., and Brunsdon, D. (2008). Facilitated process for improving organizational resilience. Nat. Haz. Rev. 9, 81–90. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2008)9:2(81)

McNally, R. J. (2003). Progress and controversy in the study of posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 54, 229–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145112

Meneghel, I., Martínez, I. M., and Salanova, M. (2016). Job-related antecedents of team resilience and improved team performance. Pers. Rev. 45, 505–522. doi: 10.1108/PR-04-2014-0094

Meredith, L. S., Sherbourne, C. D., Gaillot, S. J., Hansell, L., Ritschard, H. V., Parker, A. M., et al. (2011). Promoting psychological resilience in the US military. Rand Health Q. 1:2.

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Moran, B., and Tame, P. (2012). Organizational resilience: uniting leadership and enhancing sustainability. Sustainability 5, 233–237. doi: 10.1089/SUS.2012.9945

Morgan, P. B., Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2013). Defining and characterizing team resilience in elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 14, 549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.01.004

Morgan, P. B., Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2015). Understanding team resilience in the world's best athletes: a case study of a rugby union World Cup winning team. Psychol. Sport Exerc, 16, 91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.007

Ní Raghallaigh, M., and Gilligan, R. (2010). Active survival in the lives of unaccompanied minors: coping strategies, resilience, and the relevance of religion. Child and Fam. Soc. Work 15, 226–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00663.x

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., and Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Palmer, C. (2008). A theory of risk and resilience factors in military families. Milit. Psychol. 20:205. doi: 10.1080/08995600802118858

Paskevich, D. M., Brawley, L. R., Dorsch, K. D., and Widmeyer, W. N. (1999). Relationship between collective efficacy and team cohesion: conceptual and measurement issues. Group Dyn. 3:210. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.3.3.210

Paton, D., and Jackson, D. (2002). Developing disaster management capability: an assessment centre approach. Disaster Prev. Manage. 11, 115–122. doi: 10.1108/09653560210426795

Paulus, P. B., and Nijstad, B. A. (eds.). (2003). Group Creativity: Innovation through Collaboration. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Pollock, C., Paton, D., Smith, L. M., and Violanti, J. M. (2003). “Team resilience,” in Promoting Capabilities to Manage Posttraumatic Stress: Perspectives on Resilience, eds D. Paton, J. M. Violanti, and L. M. Smith (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas), 74–88.

Pulakos, E. D., Dorsey, D. W., and White, S. S. (2006). Adaptability in the workplace: selecting an adaptive workforce. Adv. Hum. Perform. Cogn. Eng. Res. 6, 41–47. doi: 10.1016/S1479-3601(05)06002-9

Reason, J. (2000). Human error: models and management. West. J. Med. 320, 768–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

Reich, J. W., Zautra, A. J., and Hall, J. S. (eds.) (2010). Handbook of Adult Resilience. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Reivich, K. J., Seligman, M. E., and McBride, S. (2011). Master resilience training in the US Army. Am. Psychol. 66, 25–34. doi: 10.1037/a0021897

Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 58, 307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020

Riolli, L., and Savicki, V. (2003). Information system organizational resilience. Omega 31, 227–233. doi: 10.1016/S0305-0483(03)00023-9

Riolli, L., Savicki, V., and Cepani, A. (2002). Resilience in the face of catastrophe: optimism, personality, and coping in the Kosovo crisis. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 1604–1627. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb02765.x

Rolland, J. S., and Walsh, F. (2006). Facilitating family resilience with childhood illness and disability. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18, 527–538. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245354.83454.68

Rouse, W. B., Cannon-Bowers, J. A., and Salas, E. (1992). The role of mental models in team performance in complex systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 22, 1296–1308. doi: 10.1109/21.199457

Rudolph, J. W., and Repenning, N. P. (2002). Disaster dynamics: understanding the role of quantity in organizational collapse. Adm. Sci. Q. 47, 1–30. doi: 10.2307/3094889

Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 147, 598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 57, 316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x

Rutter, M. (1998). Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following adoption after severe global early privation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry, 39, 465–476. doi: 10.1017/S0021963098002236

Schaubroeck, J., and Merritt, D. E. (1997). Divergent effects of job control on coping with work stressors: the key role of self-efficacy. Acad. Manage. J. 40, 738–754. doi: 10.2307/257061

Schaubroeck, J., Ganster, D. C., and Fox, M. L. (1992). Dispositional affect and work-related stress. J. Appl. Psychol. 77, 322–335. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.3.322

Schmidt, L. L., Keeton, K., Slack, K. J., Leveton, L. B., and Shea, C. (2009). Risk of Performance Errors Due to Poor Team Cohesion and Performance, Inadequate Selection/Team Composition, Inadequate Training, and Poor Psychosocial Adaptation. Human Health and Performance Risks of Space Exploration Missions: Evidence Reviewed by the NASA Human Research Program (Washington, DC), 45–84.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., and Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. J. Behav. Med. 21, 581–599. doi: 10.1023/A:1018700829825

Sharma, S., and Sharma, S. K. (2016). Team resilience: scale development and validation. Vision 20, 37–53. doi: 10.1177/0972262916628952

Shawn Burke, C., Wilson, K. A., and Salas, E. (2005). The use of a team-based strategy for organizational transformation: guidance for moving toward a high reliability organization. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 6, 509–530. doi: 10.1080/24639220500078682

Shia, R. M., Hagen, J. A., McIntire, L. K., Goodyear, C. D., Dykstra, L. N., and Narayanan, L. (2015). Individual differences in biophysiological toughness: sustaining working memory during physical exhaustion. Mil. Med. 180, 230–236. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00363

Smith, E. M., Ford, J. K., and Kozlowski, S. W. J. (1997). “Building adaptive expertise: Implications for training design,” in Training for a Rapidly Changing Workplace: Applications of Psychological Research, eds M. A. Quinones and A. Ehrenstein (Washington, DC: APA Books), 89–118.

Smith-Jentsch, K. A., Kraiger, K., Cannon-Bowers, J. A., and Salas, E. (2009). Do familiar teammates request and accept more backup? Transactive memory in air traffic control. Hum. Factors 51, 181–192. doi: 10.1177/0018720809335367

Somers, S. (2009). Measuring resilience potential: an adaptive strategy for organizational crisis planning. J. Contingencies Crisis Manage. 17, 12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00558.x

Sood, A., Prasad, K., Schroeder, D., and Varkey, P. (2011). Stress management and resilience training among Department of Medicine faculty: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 858–861. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1640-x

Steinhardt, M., and Dolbier, C. (2008). Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J. Am. College Health 56, 445–453. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454

Stephens, J. P., Heaphy, E. D., Carmeli, A., Spreitzer, G. M., and Dutton, J. E. (2013). Relationship quality and virtuousness: emotional carrying capacity as a source of individual and team resilience. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 18, 1–29. doi: 10.1177/0021886312471193

Stevens, R., Galloway, T., Lamb, J., Steed, R., and Lamb, C. (2015). Proceedings from International Conference on Augmented Cognition: Team Resilience: A Neurodynamic Perspective. New York, NY: Springer.

Stewart, J., and O'Donnell, M. (2007). Implementing change in a public agency: leadership, learning and organisational resilience. Int. J. Public Sector Manage. 20, 239–251. doi: 10.1108/09513550710740634

Stokols, D., Misra, S., Moser, R. P., Hall, K. L., and Taylor, B. K. (2008). The ecology of team science: understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35, 96–115. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003

Stout, R. J., Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Salas, E., and Milanovich, D. M. (1999). Planning, shared mental models, and coordinated performance: an empirical link is established. Hum. Factors 41, 61–71. doi: 10.1518/001872099779577273

Sturgeon, J. A., and Zautra, A. J. (2013). Psychological resilience, pain catastrophizing, and positive emotions: perspectives on comprehensive modeling of individual pain adaptation. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 17, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0317-4

Tugade, M. M., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86, 320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320

Van Der Haar, S., Jehn, K. A., and Segers, M. (2008). Towards a model for team learning in multidisciplinary crisis management teams. Int. J. Emerg. Manage. 5, 195–208. doi: 10.1504/IJEM.2008.025091

VandeWalle, D., Cron, W. L., and Slocum, J. W. Jr. (2001). The role of goal orientation following performance feedback. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 629–640. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.629

Vidal, M. C., Carvalho, P. V., Santos, M. S., and dos Santos, I. J. (2009). Collective work and resilience of complex systems. J. Loss Prev. Process Indus. 22, 516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jlp.2009.04.005

Vogus, T. J., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). “Organizational resilience: towards a theory and research agenda,” in Paper Presented at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Systems, Man and Cybernetics International Conference (Montreal, QC: Canada), 3418–3422.

Vogus, T. J., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2012). Organizational mindfulness and mindful organizing: a reconciliation and path forward. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 11, 722–735. doi: 10.5465/amle.2011.0002C

Wagstaff, C., Fletcher, D., and Hanton, S. (2012). Positive organizational psychology in sport: an ethnography of organizational functioning in a national sport organization. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 24, 26–47. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2011.589423

Weaver, S. J., Bedwell, W. L., and Salas, E. (2011). “Team training as an instructional mechanism to enhance reliability and manage errors,” in Errors in Organizations, eds D. Hofmann and M. Frese (New York, NY: Routledge), 143–176.

Weick, K. E., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2006). Mindfulness and the quality of organizational attention. Organ. Sci. 17, 514–524. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0196

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., and Obstfeld, D. (2008). Organizing for high reliability: processes of collective mindfulness. Crisis Manag 3, 81–123.

Werner, E., and Smith, R. (2001). Journeys from Childhood to the Midlife: Risk, Resilience, and Recovery. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press.

West, B. J., Patera, J. L., and Carsten, M. K. (2009). Team level positivity: investigating positive psychological capacities and team level outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 30, 249–267. doi: 10.1002/job.593

Wilson, K. A., Burke, C. S., Priest, H. A., and Salas, E. (2005). Promoting health care safety through training high reliability teams. Qual. Saf. Health Care 14, 303–309. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010090

Wilson, K. A., Guthrie, J. W., Salas, E., and Howse, W. R. (2006). “Team processes,” in Handbook of Aviation Human Factors, eds J. A. Wise, V. D. Hopkin, and D. J. Garland (Hillsdale, NJ: CRC Press), 9.1–9.22.

Wing, L. S. (2005). Leadership in high-performance teams: a model for superior team performance. Team Perform. Manage. Int. J. 11, 4–11. doi: 10.1108/13527590510584285

Wright, M. O. D., and Masten, A. S. (2015). “Pathways to resilience in context,” in Youth Resilience and Culture (Springer), 3–22.

Keywords: team performance, resilience (psychology), stress, psychological, team processes, team training

Citation: Bowers C, Kreutzer C, Cannon-Bowers J and Lamb J (2017) Team Resilience as a Second-Order Emergent State: A Theoretical Model and Research Directions. Front. Psychol. 8:1360. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01360

Received: 21 February 2017; Accepted: 25 July 2017;

Published: 17 August 2017.

Edited by:

Silvan Steiner, University of Bern, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

John Paul Stephens, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesPaul Morgan, Buckinghamshire New University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2017 Bowers, Kreutzer, Cannon-Bowers and Lamb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Clint Bowers, Y2xpbnQuYm93ZXJzQHVjZi5lZHU=

Clint Bowers

Clint Bowers Christine Kreutzer1

Christine Kreutzer1 Jerry Lamb

Jerry Lamb