- 1Department of Psychology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

- 2Graduate College of Social Work, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

The positive outcomes associated with Patient Engagement (PE) have been strongly supported by the recent literature. However, this concept has been marginally addressed in the context of cancer. Limited attention has also received the role of informal caregivers in promoting physical and psychological well-being of patients, as well as the interdependence of dyads. The Cancer Dyads Group Intervention (CDGI) is a couple-based psychosocial intervention developed to promote engagement in management behaviors, positive health outcomes, and the quality of the relationship between cancer patients and their informal caregivers. The article examines the ability of the CDGI to promote adaptive coping behaviors and the perceived level of closeness by comparing cancer patients participating in the intervention and patients receiving psychosocial care at usual. Results indicate that individuals diagnosed with cancer attending the CDGI present significant increases in Fighting Spirit and Avoidance, while reporting also reduced levels of Fatalism and Anxious Preoccupation. Initial indications suggest that the intervention may contribute to strengthening the relationship with the primary support person.

Introduction

Patient engagement (PE) is defined as the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral activation of patients in their care (Graffigna et al., 2013). With increasing demands for a more active role of individuals in their healthcare (Crawford et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2005; Bellardita et al., 2012; Barello et al., 2014a,b; Menichetti et al., 2014; Barello and Graffigna, 2015), this concept is emerging as a key factor to promote healthy behaviors, better outcomes in the context of chronic diseases, as well as greater satisfaction with quality of care (Barello et al., 2012; Graffigna et al., 2013). In contrast with the great attention received elsewhere, PE has been marginally addressed within the context of cancer despite the evidence collected. For example, a recent survey conducted by CancerCare (2016) on 3000 adults highlighted that physical, emotional, financial, and social costs of cancer are not currently met because of the challenges patients report in collecting information about the disease, understanding their diagnosis, and communicating with the healthcare team. Furthermore, while PE has been traditionally promoted by focusing on individual factors, there is increasing attention to the family system (Carman et al., 2013; Donato and Bertoni, 2016). As stated by Carman et al. (2013) “those who engage and are engaged include patients, families, caregivers, and other consumers and citizens” (Carman et al., 2013, p. 224). This view of engagement as inclusive of the patient's tapestry of relationships has essential implications for cancer, since it is now well-established in the literature that cancer is a relational illness (Revenson et al., 2005; Kayser et al., 2007; Manne and Badr, 2008).

Not only the disease can negatively affect the patient's quality of life by reducing physical and psychological well-being (Epplein et al., 2011; Drake, 2012; Poghosyan et al., 2013), but the illness equally affects partners and family members, who often assume the role of informal caregivers (Meeker et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2015). While significant attention has been dedicated to cancer patients' adaptation to diagnosis and treatment, the role of caregivers has been only recently addressed by the literature (Institute of Medicine, 2008). This is in contrast with the caregiving literature, which has confirmed over the years the burden associated with this role (Given et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006). Caregiving is often related to sleep disorders (Hearson and McClement, 2007; Fletcher et al., 2008), difficulties maintaining an occupation (Rossi Ferrario et al., 2003; Stetz and Brown, 2004; Bishop et al., 2007), emotional distress (Hagedoorn et al., 2008; Kim and Given, 2008; Kim et al., 2010), as well as high levels of anxiety and depression (Rhee et al., 2008; Cipolletta et al., 2013).

Similarly, the individual focus registered in the PE literature is antithetic to the literature on couple relationships. The extensive body of knowledge collected in the last 20 years about stress and coping has highlighted that patients' and partners' adjustment to cancer is indeed interdependent, therefore supporting the need to assume a relational perspective when working with dyads (Li and Loke, 2008; Traa et al., 2014; Vellone et al., 2014). Some authors, in fact, have identified how the couple relationship has a crucial role in promoting partners' well-being, healthy behaviors, and this datum has been confirmed across illnesses and even among healthy couples (Revenson et al., 2005; Kayser et al., 2007; Manne and Badr, 2008; Saita and Cigoli, 2009; Bertoni and Bodenmann, 2010; Bertoni et al., 2012; Carpenter et al., 2015; Donato et al., 2015; Pagani et al., 2015). The concept of dyadic coping (Bodenmann, 2005) is of particular relevance in the process to move from an individualistic to a relational view of PE. Since PE represents a dynamic and changing process, the relational context can significantly affect the individual's ability to adjust to the disease (Barello et al., 2012). It therefore follows that to support this process, the attention of the researcher should be on strengthening the coping abilities of the patient and the informal caregiver working with the dyad as a unit.

Donato and Bertoni (2016) have recently proposed a model of individual, interactive, and dyadic engagement organized on two axes: appraisal and actions of care. The authors see patient-partner healthcare patterns as a result of individual vs. shared appraisal of health management, and of an individualistic vs. relational view of the health management strategies. But how is it possible to translate this relational framework in interventions that promote patients and partners' engagement? Surprisingly, a paucity of studies have examined the association of partners' relational processes, exchanges, and engagement. Even less couple-based interventions have been recorded in the literature (Scott and Kayser, 2009; Baik and Adams, 2011; Regan et al., 2012; Badr and Krebs, 2013; see for example Badr et al., 2013). An aspect of limitation is that these experiences have focused mainly on breast, prostate, and gynecological cancers, and that only recently the literature has started to focus on other types of cancer (i.e., lung cancer). Furthermore, despite their relational focus, most contributions concentrated on patients and caregivers' outcomes separately. Hence, a significant gap in the current literature is the limited knowledge available about best practices to promote patients as well as informal caregivers' activation and engagement (Donato and Bertoni, 2016). This evidence supports the need to develop psychosocial interventions dedicated to the patient-caregiver dyad, grounded in a theoretical model that values the role of close relationships and that can be ultimately aimed at increasing the level of patients and caregivers' engagement in behaviors that (a) contribute to more beneficial adaptation to the cancer experience, and (b) support the bond between the individual and the informal caregiver.

The present contribution examines the effectiveness1 of the Cancer Dyads Group Intervention (CDGI); an innovative protocol developed to promote engagement in management behaviors, maximize positive health outcomes, and the quality of the relationship between cancer patients and their informal caregivers. The unique features of this approach can be identified in its theoretical framework, relational focus, and in the fact that the program can be easily translated into routine care in a variety of settings (from hospitals to community-based centers, and private practice). An overview of the program, its theoretical foundation, and techniques is available in Table 1. While participating in the CDGI program, patients, informal caregivers, and healthcare providers engage in an active partnership aimed at ensuring the best quality of care. The article presents the available empirical evidence about the ability of the CDGI to promote adaptive coping behaviors and the quality of the relationship by comparing participants and individuals receiving usual psychosocial care.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 50 cancer patients recruited from two hospitals in the Northern part of Italy. Sixteen patients participated in the CDCI, while the remaining 34 were used as a control group. Cancer patients who did not participate in the group intervention were referred to usual psychosocial care available at the institutions involved in the study (psychologists and psychiatrists), where the most common type of psychosocial support is individual therapy. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University IRB as coordinating center of the study and each participating institution (E. Bassini Hospital, Milano, Policlinico Hospital, Monza). The inclusion criteria for the study required that the participants were: (1) 18 years old or older, (2) free of dementia symptoms and a psychiatric diagnosis, (3), involved in a relationship with a significant other (partner, spouse, family member, friend), (4) Italian-speaking, and (5) had received a diagnosis of cancer in the last 3 months.

The average age of the participants in both groups was 62 years (SD = 8.80 for CDGI, SD = 8.12 for the Control Group). In the CDGI group, the majority of the patients were women (87.5%) diagnosed mostly with breast cancer (68.8%), where only a small number of participants were in treatment for rare cancer (31.3%). Overall, participants in the intervention group were married (56.3%) and were not highly educated (62.6% did not graduate from high school). Subjects in the control group present similar socio-demographic characteristics. Most patients were women (79.4%), and individuals with rare cancer diagnoses represented one third of the group (32.4%). Similar to what reported for the intervention group, 76.5% of cancer patients were married. However, members of the control group were more highly educated, with 32.4% being high school graduates and 8.8% being college graduates. Informal caregivers of individuals in the CDGI group were mostly romantic partners (75%), with a mean age of 65 (mean 64.8, SD = 9.1), low level of education (52% had only completed junior high school), and currently retired (60%).

Procedure

Participants were initially screened by a psychologist to determine their eligibility. After a brief interview about the cancer experience, study participants completed a set of questionnaires measuring closeness with their informal caregiver, and coping strategies at time of recruitment (within 3 months from diagnosis). The same questionnaires were then completed within the 1 month after the end of the intervention, while for individuals in the control group the post-test data collection occurred 6 months after the initial contact.

Measures

Individual Coping. To identify the prevailing coping style used to cope with cancer, the Italian version of the Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale (Mini-MAC) (Watson et al., 1994; Grassi et al., 2005) was selected. The instrument is a 29-item questionnaire which identifies five coping strategies: Fighting Spirit, Hopeless/Helplessness, Anxious Preoccupation, Fatalism and Avoidance. Hopelessness/Helplessness indicates a coping style characterized by the belief of low control on events, which is associated with high levels of anxiety and depression. Individuals with a fatalistic coping behavior show low sense of control, resignation and passive acceptance of fate. Anxious Preoccupation is used to describe a coping modality with high levels of anxiety and worry about the cancer diagnosis, which can impact the quality of life of the individual. The patient is either looking for constant reassurance or is distancing herself/himself from the healthcare environment. Avoidance indicates the tendency to minimize cancer and to refrain from the search of information. Fighting Spirit is characterized by an optimistic attitude toward one's ability to cope with the illness. Next to low levels of anxiety and depression, individuals presenting fighting spirit tend to perceive the illness as a challenge. They implement diverse and flexible cognitive strategies, which contribute to a positive appraisal of the experience. This coping style has been associated with better psychological morbidity, increased sense of control and better prognosis (Pettingale et al., 1985; Burgess et al., 1988; Saita et al., 2015a).

Interpersonal Closeness. Perceived level of closeness with the primary support person was measured by the Inclusion of the Other in the Self (IOS) Scale (Aron et al., 1992). The measure consists of seven pairs of overlapping circles that are drawn to show varying levels of overlap, indicating an increasing degree of closeness in the relationship. A 7-point scale is used to score the degree of closeness. In the present study, we asked the individual to indicate up to five persons who provide support to them and describe each relationship by choosing one of the seven circles. Although the scale is not formally validated in the Italian population, the very easy and intuitive nature of the questionnaire -being a single item pictorial tool- has contributed to its use with Italian subjects, as documented by earlier works of these authors (Saita et al., 2015a), other Italian researchers (ex. De Panfilis et al., 2015), or studies conducted including Italian samples (Karremans et al., 2011).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of cancer patients were obtained for all the variables compiling frequency tables, histograms, and bar graphs. Differences in the coping style behavior for the intervention and control group were examined with Independent Sample t-test, while differences within patients were assessed calculating paired samples t-test. IBM SPSS Statistics 22 was used for data screening and data analysis. Changes in the perceived degree of closeness with the informal caregivers were described comparing who were the sources of support identified by the cancer patients and by calculating the mean scores originating from the position of the IOS Scale used to describe these relationships

Results

Differences between Patients: Examining Changes in Coping Style between the Intervention and Control Group at Pre-test and Post-test

An Independent Samples t-test was used to compare the mean score of each coping strategy of individuals participating in the CDGI intervention and those of the control group at pre and post-test, in order to identify if the two groups were already different in their coping behaviors at pre-test and if a change occurred at the post-test. While results indicate that no statistically significant difference existed at pre-test, at post-test individuals who participated in the CDGI presented significantly higher Fighting Spirit [t(48) = 2.71, p < 0.01] than cancer patients who received usual psychosocial care.

Differences within Patients: Pre-test/Post-test Comparison among the Participants of the Intervention and Control Group

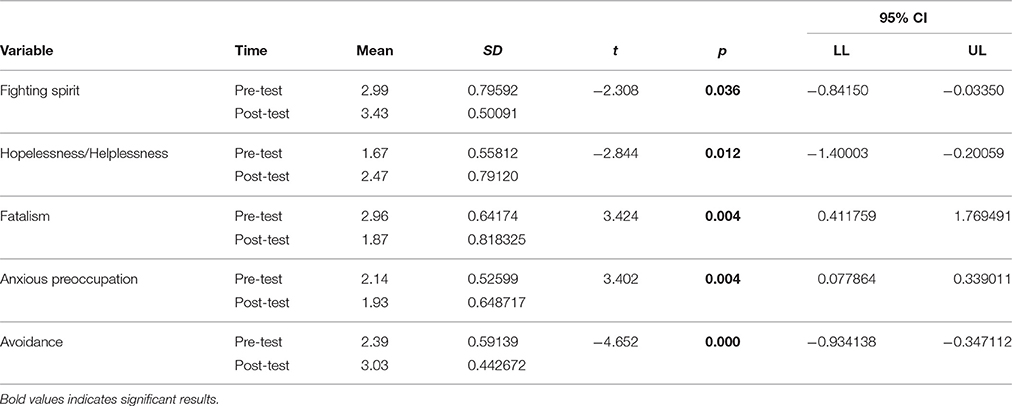

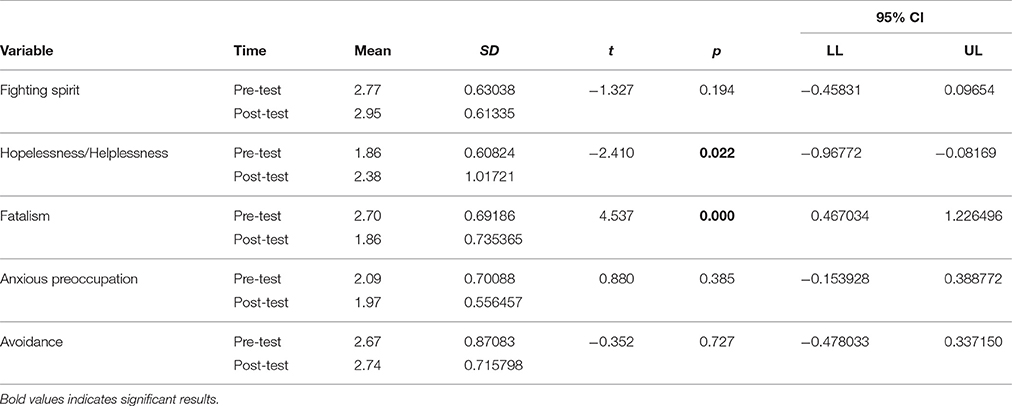

The previous findings were confirmed when a pre-test/post-test comparison was conducted on each group, using Paired Samples t-test. Results indicate that individuals diagnosed with cancer attending the CDGI present significant increase in Fighting Spirit [t(14) = −2.31, p < 0.05] and Avoidance [t(14) = −4.65, p < 0.001], while reporting also reduced mean scores in Fatalism [t(14) = 3.42, p < 0.01] and Anxious Preoccupation [t(14) = 3.40, p < 0.01]. On the contrary, the changes registered in the control group indicate that individuals reported significantly higher scores of Hopelessness/Helplessness [t(32) = −2.41, p < 0.05] next to reduced Fatalism [t(32) = 4.54, p < 0.001] (Tables 2, 3).

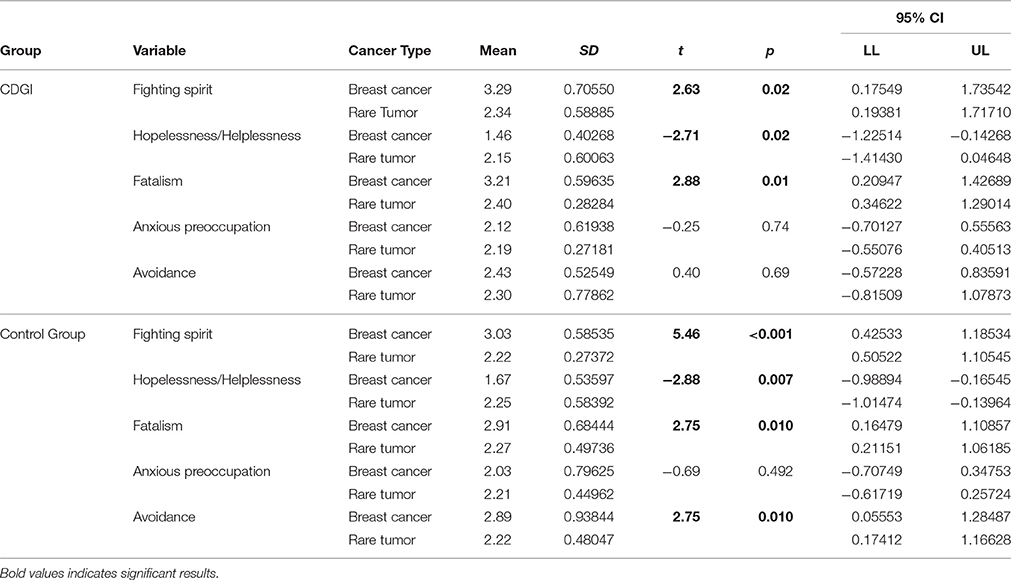

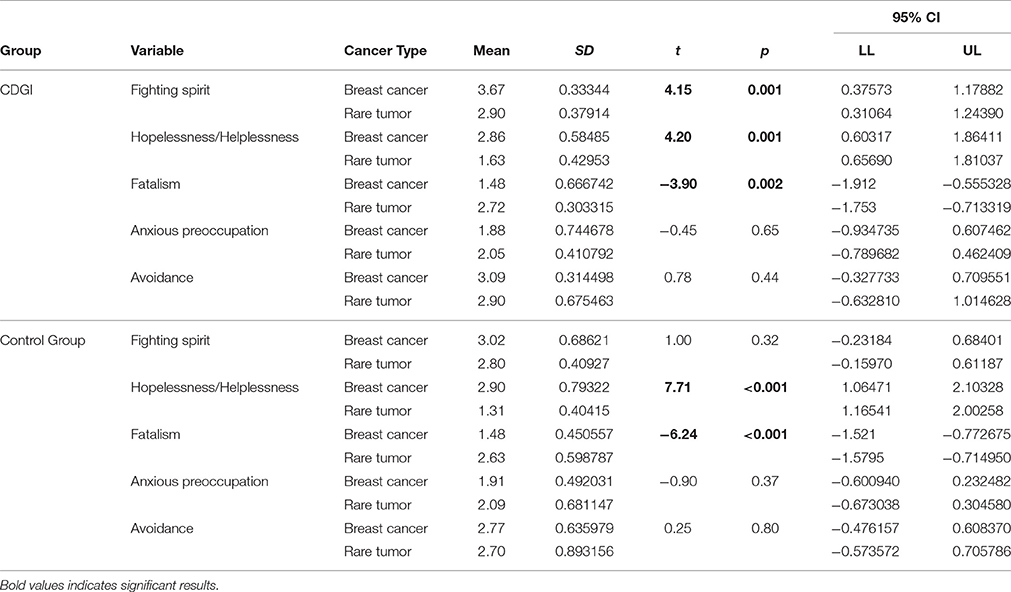

While the results about Hopelessness/Helplessness may be considered in contrast with the overall aim of the intervention, they may be contextualized referring to the types of cancer included in the study. Given the limited number of subjects in the two groups, this analysis is only exploratory in nature. When the mean scores have been compared differentiating between breast and rare cancer patients, results indicate that at pre-test individuals with rare tumors in the CDGI presented significantly higher scores of Hopelessness/Helplessness [t(14) = −2.71, p < 0.05] compared to women with breast cancer, while on the contrary this group scored higher on Fighting Sprit [t(14) = 2.63, p < 0.05] and Fatalism [t(14) = 2.88, p < 0.05]. The same differences were found also in the control group, where breast cancer patients also shown higher Avoidance [t(32) = 2.75, p < 0.05]. At post-test, it clearly emerges how the intervention contributed to reduced Hopelessness in patients with rare tumors [t(14) = 4.19, p < 0.01], while patients with breast cancer presented significantly higher Fighting Spirit [t(14) = 4.15, p < 0.01] and significantly lower Fatalism [t(14) = −3.9, p < 0.01]. In the control group, differences were registered on Fatalism [t(32) = −6.2, p < 0.001] and Hopelessness [t(32) = 7.7, p < 0.001], with individuals with breast cancer presenting higher Hopelessness and lower Fatalism (Tables 4, 5).

Examining Changes in the Perceived Degree of Closeness with the Primary Support Person

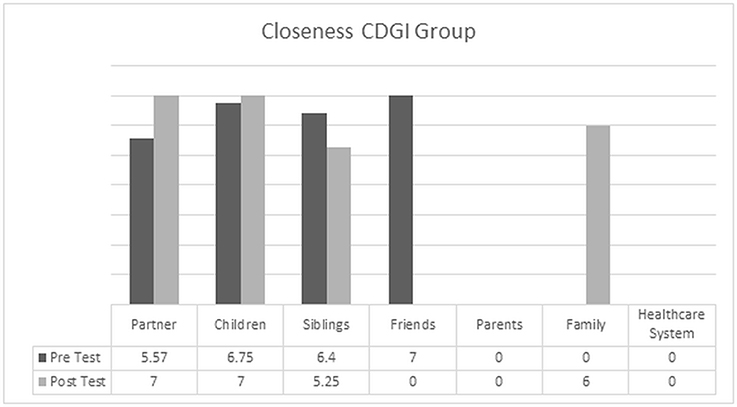

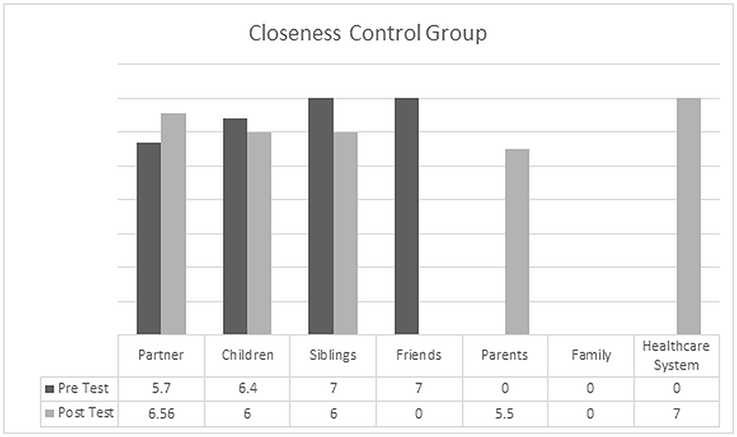

The relational perspective of the intervention determines the need to explore the perceived level of closeness with the informal caregiver. To examine changes in the two groups we first considered which persons were identified as the primary source of support, and then we compared the mean values obtained from the picture selected by the participants as indication of closeness. For individuals in the CDGI, the source of their support is identified in the relationship with partners, children and siblings. This indication is confirmed also at post-test, with these three categories being the most listed by the participants. One patient also indicated that the family as a whole became the source of support. For the control group, while at pre-test the most commonly identified individuals were partners, children, and siblings, 6 months after the initial contact patients started to expand their supportive network and to include parental figures and the healthcare system.

When focusing specifically on the degree of closeness with the primary support person, which are presented in Figures 1, 2, it is possible to notice how members of the CDGI reported elevated levels of closeness with the primary support person; as indicated by higher scores in the relationships with partners, children and siblings. We want also to note that while the perceived closeness with friends was very elevated at pre-test, this relationship was no longer indicated at post-test. On the contrary, friends were substituted by the family as a whole, indicating greater reliance of the patient on the family system.

Figure 2 illustrates the change registered among individuals in the control group. The perceived level of closeness with the partner increased, but for those patients who identified the primary support person with children or siblings, the perceived closeness was reduced at post-test. Furthermore, the relationship with peers lost relevance over time, substituted by a closer connection with the parental figures. It is also important to highlight that for this group the family as a whole did not assume a meaningful role over time, and that external sources of support were searched in the relationships established with healthcare providers, such as physicians, nurses, and mental health professionals.

Discussion

In this paper we have supported the relevance close relationships have in the promotion of PE in the context of cancer. As a result of the need to assume a relational view of this concept, we have illustrated the CDGI as a way to operationalize PE as involving patients and informal caregivers. This program has been developed with the goal to increase patients' engagement in management behaviors, enhance awareness of the emotional dimension associated with the illness, and to promote the quality of the relationship between cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Furthermore, this article aspired to provide further empirical evidence about the effectiveness of the CDGI to activate patients' coping abilities and strengthening the senses of closeness with the primary support person, while previous works have been mostly focused on the process of the intervention (Saita et al., 2014). The analysis conducted in the present contribution focused on the coping strategies and the perceived degree of closeness, by comparing pre-test and post-test scores of patients who participated in the intervention and those of were referred to usual psychosocial care. Three are the most relevant findings to discuss.

First, differences in coping strategies between patients highlight how individuals who participated in the CDGI have developed higher levels of Fighting Spirit at the end of the program, which suggests that participants were able to develop more adaptive behavioral and emotional strategies. They seem to be better equipped to cope with the potentially stressful events and feelings associated with the cancer experience than the individuals who did not. Moreover, the enactment of coping behaviors characterized by Fighting Spirit also reveals the willingness of the individual to face the multiple stressors a cancer diagnosis originates, and the realization of mastering the abilities necessary to face the disease. This aptitude also sustains the hope to foresee a future with no cancer, despite the uncertainty associated with this illness (Coward and Kahn, 2004; Saita et al., 2015b).

This finding is also supported by the pre-test and post-test comparison of the two groups. In our study, the control group reported statistically significant increase in Hopelessness and Fatalism. Individuals receiving usual care showed over time indication of low control on events, resignation, and passive acceptance, which has been associated with negative quality of life outcomes in the literature (Meerwein, 1989; Barraclough, 2001). On the contrary, individuals in the intervention group presented aspects of change in all the coping styles evaluated. While the indication of higher Fighting Spirit and Avoidance, reduced Fatalism, and lower Anxious Preoccupation are in line with the outlined goals, the statistically significant increase in Hopelessness/Helplessness appeared in contrast with our hypotheses. However, these findings may be clarified considering how the two types of cancer in the sample (breast cancer vs. rare tumors) can affect the quality of life of the individual, given the dissimilar treatments, outcomes, and survivorship issues. Although it is necessary to be mindful of the very limited number of individuals with rare tumors included in the study, it is possible that the different level of information and knowledge available about rare types of cancer (including the preparedness of the healthcare team) can contribute to affect the outcome of the intervention. A second consideration then pertains the feelings associated with a cancer diagnosis, which are often unexpected and destabilizing for the individual, whose sense of psychological and physical integrity is suddenly threatened. Despite the differences between facing a well-known and studied pathology vs. a rare disease, the possibility to receive information related to the illness and its treatment contributes to higher adherence (Cousson-Gélie et al., 2008). In this sense, the higher level of Hopelessness/Helplessness registered among patients in the control group can be partially explained by the sense of loneliness and isolation experienced when facing cancer alone. The attendance of the CDGI can, on the contrary, alleviate the feelings of helplessness and lack of control the diagnosis has originated.

Finally, given the theoretical foundation of our work and the role close relationships have for physical and psychological well-being of patients and informal caregivers, we examined patients' closeness. These findings suggest that the CDGI experience represents a setting where the relationship with the primary support person can be nurtured and strengthened. Not only CDGI participants continued to identify as sources of support the relationships established within the family of origin or the partner, but the descriptive analysis about the mean level of closeness indicates that the program contributed to increased degree of proximity and support with the informal caregiver and the family as a whole. Differently, individuals in the control group experienced lower sense of closeness with children and siblings, and some of them showed a tendency over time to rely more on the healthcare system. This movement mirrors “the stress-coping cascade effect” (Bodenmann, 2005), which describes how individual coping strategies are substituted by dyadic approaches (involving partners, relatives, and friends), and ultimately healthcare professionals. Hence, when a coping strategy is no longer functional, the individual continues to search support until he can find an adequate response to his needs. Results of the descriptive analysis of the IOS Scale data are of particular interest because while extensive attention has been given to the development of psychosocial interventions to promote coping, a limited number of studies have investigated the less conscious aspect of the relationship between cancer patient and his/her informal caregiver (Aron and Aron, 1986; Aron et al., 1991).

Given the important clinical implications the intervention has for the current debate about best-practices to promote patients and informal caregivers' engagement to care, it is important to describe how this contribution is affected by several limitations. First, the present work relied on a small sample size, which limits our ability to generalize these findings and also represents a limitation in the selection of the data analysis strategy. While difficulties in the recruitment of dyads in research are extensively reported, this article also represents the result of years of collaboration with hospital settings and illustrates a strategy to move from a qualitative analysis of the intervention (Saita et al., 2014) toward a quantitative approach. Moreover, in this contribution it was not possible to include and analyze data from both members of the dyad. Although this may seem in contrast with the relational perspective that has inspired our work, the need to focus only on patients' data was influenced by the fact that the questionnaires completed by the participating caregivers, although being collected as part of the research protocol, were not fully available at the time of the analysis. It will be therefore important to include data about patients and caregivers' change as part of the participation in the CDGI to provide further empirical evidence to the findings we have published so far. Third, as the intervention promotes dyadic coping strategies to strengthen adaptation and engagement in both partners, a measure of dyadic coping should be included in future works. Similarly, it will be critical to add a measure of PE and to target participants' satisfaction with care; aspects that were not investigated in the current work. Finally, from a methodological perspective, data should be analyzed using a dyadic data approach, in order to account for the interdependence of patients' and partners' scores.

Summarizing, while a relational view of the concept of PE has received increasing attention in the literature, the present work has illustrated how it is possible to develop interventions that support the bond between the individual and his/her informal caregiver. Within these experiences, the CDGI contributes to foster PE as a “process-like and multidimensional experience” (Graffigna et al., 2014, p. 1), by focusing both on health information (working together with providers) and on the affective dimension of the illness. Participants reported significant reduction in coping strategies like Anxious Preoccupation and Fatalism, and higher Fighting Spirit than controls. Furthermore, from this initial analysis it is possible to appreciate how the CDGI represents a setting where it is possible to support the relationship between patient and informal caregiver.

Not only this program is almost unique in the field of PE in the context of cancer, but while previous studies have targeted only individuals outcomes, the intervention described here helps participants to find the resources to cope with the illness indentifying the relationship as the therapeutic tool. Since support within the context of a close relationship leads to better outcomes, we propose that forms of intervention that focus on these dyads would be appropriate and potentially effective in promoting and enhancing engagement and quality of life for both the patient and partner (Kayser and Scott, 2008; Saita et al., 2014). This brings us back to the suggestions identified by Donato and Bertoni (2016) about the development of interventions aimed at promoting patients and partners' enagement. The authors discuss the relevance of a clear theoretical framework, of addressing both patients and partner's needs, and to being able to integrate individual, interactive, and relational levels of intervention. These indications guided our work and were used to support the effectiveness of the intervention, given that the CDGI integrates the Bio-psychosocial Model (Engel, 1977), the Symbolic Relational Model (Cigoli and Scabini, 2006; Scabini and Cigoli, 2012), and the Psycho-Educational Approach (Fawzy and Fawzy, 1998). Similarly, the intervention focuses on the dyad and the relationship between patients and caregiver, therefore integrating excercises and activities with individual, interactive and relational focus. Our study then represents a nice integration of their model, as it introduces also a third dimension to consider when developing interventions to promote PE using a relational perspective. As the appraisal of care and the actions of care define three levels of patient-partner engagement, psychosocial interventions should be placed along a continuum of settings (ranging from individual, couple, and group of patients or caregivers, and groups of dyads) with the goal to offer the most appropriate and effective setting of intervention given the unique characteristics of the participants the equipe is working with.

Author Contributions

Literature Review: CA and SM. Description of Intervention: ES. Data collection and Data analysis: ES and CA. Discussion: All authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Cfr. (Haynes, 1999).

References

Acitelli, L. K., and Badr, H. (2005). “My illness or our illness? Attending to the relationship when one partner is ill,” in Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping, eds T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, and G. Bodenmann (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 121–136.

Aron, A., and Aron, E. N. (1986). Love as the Expansion of Self: Understanding Attraction and Satisfaction. New York, NY: Hemisphere.

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., and Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of the other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 596–612. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., Tudor, M., and Nelson, G. (1991). Close relationship as including other in the self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 241–253. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.241

Badr, H., Camack, C. L., Milbury, K., and Temech, M. (2013). “Psychosocial intervention for couples coping with cancer: A systematic review,” in Psychological Aspects of Cancer, eds B. I. Carr and J. Steel (New York, NY: Springer), 177–198.

Badr, H., and Krebs, P. (2013). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psychooncology 22, 1688–1704. doi: 10.1002/pon.3200

Baik, O. M., and Adams, K. B. (2011). Improving the well-being of couples facing cancer: a review of couples-based psychosocial intervention. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 37, 250–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00217.x

Barello, S., and Graffigna, G. (2015). “Engagement-sensitive decision making: training doctors to sustain patient engagement in medical consultations,” in Patient Engagement: A Consumer-Centered Model to Innovate Healthcare, eds G. Graffigna, S. Barello, and S. Triberti (Berlin: De Gruyter Open), 78–93.

Barello, S., Graffigna, G., Savarese, M., and Bosio, A. C. (2014a). Engaging patients in health management: towards a preliminary theoretical conceptualization. Psicol. Salute 3, 11–33. doi: 10.3280/PDS2014-003002

Barello, S., Graffigna, G., and Vegni, E. (2012). Patient engagement as an emerging challenge for healthcare services: mapping the literature. Nurs. Res. Pract. 1, 17. doi: 10.1155/2012/905934

Barello, S., Graffigna, G., Vegni, E., and Bosio, A. C. (2014b). The challenges of conceptualizing patient engagement in health care: a lexicographic literature review. J. Particip. Med. 6:e9.

Bellardita, L., Graffigna, G., Donegani, S., Villani, D., Villa, S., Tresoldi, V., et al. (2012). Patient's choice of observational strategy for early-stage prostate cancer. Neuropsychol. Trends 12, 107–116. doi: 10.7358/neur-2012-012-bell

Bertoni, A., and Bodenmann, G. (2010). Satisfied and dissatisfied couples: positive and negative dimensions, conflict styles, and relationships with family of origin. Eur. Psychol. 15, 175–184. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000015

Bertoni, A., Parise, M., and Iafrate, R. (2012). “Beyond satisfaction: Generativity as a new outcome of couple functioning,” in Marriage: Psychological Implications, Social Expectations, and Role of Sexuality, eds P. E. Esposito and C. I. Lombardi (New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 115–131.

Bishop, M. M., Beaumont, J. L., Hahn, E. A., Cella, D., Andrykowski, M. A., Brady, M. J., et al. (2007). Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 1403–1411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5705

Bodenmann, G. (2005). “Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning,” in Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping, eds T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, and G. Bodenmann (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 33–50.

Burgess, C., Morris, T., and Pettingale, K. W. (1988). Psychological response to cancer diagnosis II. Evidence for coping styles. J. Psychosom. Res. 20, 795–802.

CancerCare. (2016). 2016 CancerCare Patient Access and Engagement Report. Available online at http://www.cancercare.org/accessengagementreport

Carman, K. L., Dardess, P., Maurer, M., Sofaer, S., Adams, K., Bechtel, C., et al. (2013). Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 32, 223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133

Carpenter, D. M., Elstad, E. A., Sage, A. J., Geryk, L. L., DeVellis, R. F., and Blalock, S. J. (2015). The relationship between partner information-seeking, information-sharing, and patient medication adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 98, 120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.001

Cigoli, V. (2002). “Lo spirito della relazione e la provocazione della malattia,” in Il Medico, la Famiglia e la Comunità. L'approccio Biopsicosociale alla Salute e alla Malattia, eds V. Cigoli and M. Mariotti (Milano: Franco Angeli), 56–76.

Cigoli, V., and Scabini, E. (2000). Il Famigliare. Legami, Simboli e Transizioni. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Cigoli, V., and Scabini, E. (2006). Family Identity. Ties, Symbols, and Transitions. New York, NY: Erlbaum.

Cipolletta, S., Shams, M., Tonello, F., and Pruneddo, A. (2013). Caregivers of patients with cancer: anxiety, depression, and distribution of dependency. Psychooncology 22, 133–139. doi: 10.1002/pon.2081

Cousson-Gélie, F., Vernejoux, J. M., Bazex-Chanteloube, H., Raherison, C., Ozier, A., Girodet, P. O., et al. (2008). Multi-professional lung cancer disclosure to change anxiety and depression: an exploratory study. Thorax 63, 658. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.093922

Coward, D. D., and Kahn, D. L. (2004). Resolution of spiritual disequilibrium by women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 31, E24–E31. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E24-E31

Crawford, M. J., Rutter, D., Manley, C., Weaver, T., Bhui, K., Fulop, N., et al. (2002). Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. Br. Med. J. 325, 1263–1265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1263

Davis, K., Schoenbaum, S. C., and Audet, A. M. (2005). A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 20, 953–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0178.x

De Panfilis, C., Riva, P., Preti, E., Cabrino, C., and Marchesi, C. (2015). When social inclusion is not enough: implicit expectations of extreme inclusion in borderline personality disorder. Personal. Disord. 6, 301–309. doi: 10.1037/per0000132

Donato, S., and Bertoni, A. (2016). “A relational perspective on patient engagement: Suggestions from couple-based research and intervention,” in Transformative Healthcare Practice through Patient Engagement, ed G. Graffigna (IGI Global), 83–106.

Donato, S., Parise, M., Iafrate, R., Bertoni, A., Finkenauer, C., and Bodenmann, G. (2015). Dyadic coping responses and partners' perceptions for relationship satisfaction: an actor-partner longitudinal analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 32, 580–600. doi: 10.1177/0265407514541071

Drake, K. (2012). Quality of life for cancer patients: from diagnosis to treatment and beyond. Nurs. Manage. 43, 20–25. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000410865.48922.18

Engel, G. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196, 129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460

Epplein, M., Zheng, Y., Zheng, W., Chen, Z., Gu, K., Penson, D., et al. (2011). Quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis and survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 406–412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6951

Fawzy, F. I., and Fawzy, N. W. (1998). Group therapy in the cancer setting. J. Psychosom. Res. 45, 191–200. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00015-4

Fletcher, B. S., Paul, S. M., Dodd, M. J., Schumacher, K., West, C., Cooper, B., et al. (2008). Prevalence, severity, and impact of symptoms on female family caregivers of patients at the initiation of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 599–605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2838

Foulkes, S. H. (1973). “The group as a matrix of the individual's mental life,” in Selected Papers, ed E. Foulkes (London: Karnac Books), 223–233.

Given, B., Wyatt, G., Given, C., Gift, A., Sherwood, P., DeVoss, D., et al. (2004). Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 31, 1105–1117. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1105-1117

Graffigna, G., Barello, S., Libreri, C., and Bosio, C. A. (2014). How to engage type-2 diabetic patients in their own health management: implications for clinical practice. BMC Public Health 14:648. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-648

Graffigna, G., Barello, S., and Riva, G. (2013). Technologies for patient engagement. Health Aff. 32, 1172. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0279

Grassi, L., Buda, P., Cavana, L., Annunziata, M. A., Torta, R., and Varetto, A. (2005). Styles of coping with cancer: the Italian version of the mini-mental adjustment to cancer (Mini-MAC) scale. Psychooncology 14, 115–124. doi: 10.1002/pon.826

Hagedoorn, M., Sanderman, R., Bolks, H. N., Tuinstra, J., and Coyne, J. C. (2008). Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effect. Psychol. Bull. 134, 1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1

Haynes, B. (1999). Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? The testing of healthcare interventions is evolving. BMJ 319, 652–653. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.652

Hearson, B., and McClement, S. (2007). Sleep disturbance in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 13, 495–501. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.10.27493

Institute of Medicine (2008). Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Karremans, J. C., Regalia, C., Paleari, F. G., Fincham, F. D., Cui, M., Takada, N., et al. (2011). Maintaining harmony across the globe: the cross-cultural association between closeness and interpersonal forgiveness. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2, 443–451. doi: 10.1177/1948550610396957

Kayser, K., and Scott, J. L. (2008). Helping Couples Cope with Women's Cancers. An Evidence-Based Approach for Practitioners. New York, NY: Springer.

Kayser, K., Watson, L. E., and Andrade, J. T. (2007). Cancer as a “we-desease”: examining the process of coping from a relational perspective. Fam. Syst. Health 25, 404–418. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.25.4.404

Kim, Y., Baker, F., Spillers, R. L., and Wellisch, D. K. (2006). Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psychooncology 15, 795–804. doi: 10.1002/pon.1013

Kim, Y., and Given, B. A. (2008). Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer 112, 2556–2568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23449

Kim, Y., Kashy, D. A., Spillers, R. L., and Evans, T. V. (2010). Needs assessment of family caregivers of cancer survivors: three cohorts comparison. Psychooncology 19, 573–582. doi: 10.1002/pon.1597

Kim, Y., Shaffer, K. M., Carver, C. S., and Cannady, R. S. (2015). Quality of life of family caregivers eight years after a relative's cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psychooncology 25, 266–274. doi: 10.1002/pon.3843

Li, Q., and Loke, A. Y. (2008). A systematic review of spousal couple-based intervention studies for couples coping with cancer: direction for the development of interventions. Psychooncology 23, 731–739. doi: 10.1002/pon.3535

Manne, S., and Badr, H. (2008). Intimacy and relationship processes in couples' psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer 112, 2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., and Shellenberger, S. (1999). Genograms: Assessment and Intervention, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Norton.

Meeker, M. A., Finnell, D., and Othman, A. K. (2011). Family caregivers and cancer pain management: a review. J. Fam. Nurs. 17, 29–60. doi: 10.1177/1074840710396091

Menichetti, J., Libreri, C., Lozza, E., and Graffigna, G. (2014). Giving patients a starring role in their own care:a bibliometric analysis of the on-going literature debate. Health Expect. 19, 516–526. doi: 10.1111/hex.12299

Pagani, A. F., Donato, S., Parise, M., Iafrate, R., Bertoni, A., and Schoebi, D. (2015). When good things happen: the effects of implicit and explicit capitalization attempts on intimate partners' well-being. Fam. Sci. 6, 119–128. doi: 10.1080/19424620.2015.1082013

Pettingale, K. W., Morris, T., Greer, S., and Haybittle, J. L. (1985). Mental attitudes to cancer: an addictional prognostic factor. Lancet 30, 750–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91283-8

Poghosyan, H., Sheldon, L.K., Leveille, S. G., and Cooley, M. E. (2013). Health-related quality of life after surgical treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer 81, 11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.013

Regan, T. W., Lambert, S. D., Girgis, A., Kelly, B., Kayser, K., and Turner, J. (2012). Do couple-based interventions make a difference for couples affected by cancer? A systematic review. BMC Cancer 12:279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-279

Revenson, T. A., Kayser, K., and Bodenmann, G. (eds.) (2005). Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rhee, Y. S., Yun, Y. H., Park, S., Shin, D. O., Lee, K. M., Yoo, H. J., et al. (2008). Depression in family caregivers of cancer patients: the feeling of burden as a predictor of depression. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 5890–5895. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3957

Rossi Ferrario, S., Zotti, A. M., Massara, G., and Nuvolone, G. (2003). A comparative assessment of psychological and psychosocial characteristics of cancer patients and their caregivers. Psychooncology 12, 1–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.626

Saba, G. W. (2002). “L'approccio biopsicosociale: mappe, miti e modelli di salute e malattia,” in Il Medico, la Famiglia e la Comunità. L'approccio Biopsicosociale alla Salute e alla Malattia, eds V. Cigoli, and M. Mariotti (Milano: Franco Angeli), 35–52.

Saita, E., Acquati, C., and Kayser, K. (2015a). Coping with early stage breast cancer: examining the influence of personality traits and interpersonal closeness. Front. Psychol. 6:88. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00088

Saita, E., and Cigoli, V. (2009). “Le relazioni di coppia e le relazioni familiari nella malattia,” in Psico-Oncologia: una Prospettiva Relazionale, ed E. Saita (Milano: Unicopli), 69–88.

Saita, E., De Luca, L., and Acquati, C. (2015b). What is hope for breast cancer patients? A qualitative study. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. III.doi: 10.6092/2282-1619/2015.3.1047

Saita, E., Molgora, S., and Acquati, C. (2014). Development and evaluation of the cancer dyads group intervention: preliminary findings. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 32, 647–664. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2014.955242

Saita, E., Zanini, S., Minetti, E., and Acquati, C. (2016). “Best practices to promote patient and donor engagement to care in living donor transplant,” in Transformative Healthcare Practice through Patient Engagement, ed G. Graffigna (IGI Global), 1–27.

Scabini, E., and Cigoli, V. (2012). Alla Ricerca del Famigliare. Il Modello Relazionale-Simbolico. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Scott, J. L., and Kayser, K. (2009). A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women's sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J. 15, 48–56. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585df

Stetz, K. M., and Brown, M.-A. (2004). Physical and psychosocial health in family caregiving: a comparison of AIDS and cancer caregivers. Public Health Nurs. 21, 533–540. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21605.x

Traa, M. J., De Vries, J., Bodenmann, G., and Den Oudsten, B. L. (2014). Dyadic coping and relationship functioning in couples coping with cancer: a systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 20, 85–114. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12094

Vellone, E., Chung, M. L., Cocchieri, A., Rocco, G., Alvaro, R., and Riegel, B. (2014). Effects of self-care on quality of life in adults with heart failure and their spousal caregivers: testing dyadic dynamics using the actor-partner interdependence model. J. Fam. Nurs. 20, 120–141. doi: 10.1177/1074840713510205

Keywords: engagement, cancer, patient, caregiver, group-based intervention

Citation: Saita E, Acquati C and Molgora S (2016) Promoting Patient and Caregiver Engagement to Care in Cancer. Front. Psychol. 7:1660. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01660

Received: 12 July 2016; Accepted: 11 October 2016;

Published: 25 October 2016.

Edited by:

Elena Vegni, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Michelle Dow Keawphalouk, Harvard University, USAFederica Galli, University of Milan, Italy

Copyright © 2016 Saita, Acquati and Molgora. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emanuela Saita, ZW1hbnVlbGEuc2FpdGFAdW5pY2F0dC5pdA==

Emanuela Saita

Emanuela Saita Chiara Acquati

Chiara Acquati Sara Molgora

Sara Molgora