94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

TECHNOLOGY REPORT article

Front. Psychol., 11 July 2014

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 5 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00721

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Flourishing World of Gaming?View all 9 articles

This technical report describes an interactive game environment designed to bring mothers and their adolescent daughters together to discuss three issues that have previously been shown in the literature to be of concern to families, as young girls transition from middle childhood to the adolescent years. The game is called Knowing you, Knowing me or KYKM, and is used to help mothers and daughters discuss the following three topics: positive communication skills, relationship building, and managing risky behaviors in the social environment. As the game remains untested, its limitations and future implications of its utility are discussed.

The aim of this project is to provide a positive communication game via the medium of web-based cartoon characters and “sms” messaging to inform mothers and daughters about positive communication, relationship building, and minimization of risky behaviors. The Knowing you, Knowing me, or the KYKM project has been developed as a multimedia gaming and mobile resource to increase the positive communication skills of adolescent females and their mothers during this time of developmental transition.

Much of the focus of mother-daughter relationships in the literature has been on strategies to manage and deal with negative adolescent behavior such as identity and attachment issues (Benson et al., 1992), conflict (Steinberg, 1987), violence (Caprara et al., 2002), parental satisfaction (Erel and Burman, 1995), divorce and remarriage (Orbuch et al., 2000), and antisocial behavior (Loeber et al., 1998). This deficit-based approach has been replaced in recent times by the strengths-based approach of positive psychology (Katsikitis et al., 2013a) and is the focus of this paper.

There is a substantial body of evidence endorsing the mother-daughter relationship and the influence that a positive, stable bond has on females throughout their lives (Boyd, 1989; Herman, 1989). The research evidence also suggests that it is the quality of the relationship and interactions between mother and daughter and positive parenting practices that contribute to the psychosocial adjustment of the adolescent girl (Barber et al., 2001). The KYKM project addresses these issues using an innovative, game-based design, which brings mothers and daughters together, builds communication and relationship skills, and uses positive parenting practices to mitigate risk taking behaviors in this young population.

Successful intervention programs meet the needs of parents as well as their children with the best impact being for mothers and daughters in programs that facilitate interaction between dyads to raise communication and conflict resolution skills and support positive longer term relationships (Schinke et al., 2009; Velleman, 2009). Early intervention that involves both groups provides the best results (Koning et al., 2009).

New communication technologies such as KYKM, are now being used to support these programs (Newton et al., 2009a,b; Schinke et al., 2009). They are attractive to adolescents and in the case of KYKM, are out-of-school activities, therefore they provide a cost effective way to deliver alternative experiences and information to adolescents. They also provide a new opportunity to design supportive, attractive and nurturing experiences that meet the developmental needs of both groups and lead to better outcomes for participants. Research suggests that web-based programs can build social capital in terms of hope, resilience, optimism and efficacy (Luthens et al., 2008). Finally, the revolution in communication technologies has been driven by the fact that these technologies are used to meet real needs. New forms of networked technologies and the underpinning networked relationships now offer new ways for people to manage the emotional risks of negotiating boundaries, privacy and shared intimacy (De Vulpian, 2005).

Multimedia gaming resource interventions offer a portable mode of delivery that is appealing to young people. Text messaging by phone or online chat is an effective method to communicate about emotionally charged issues or to coordinate shared activities effectively (Fukkink and Hermas, 2009). Similarly, motion cartoon characters and home-made short videos (Schinke et al., 2009) have been used successfully by mothers and their daughters to amplify the emotional content and risks of situations in ways that can be accepted, discussed, thought about and learned from.

The KYKM project is a gender specific program that has been developed to meet the needs of adolescent females and their mothers and allow them to engage in shared activities. In addition, this form of delivery advocates for a consistent approach to ensuring all recipients receive the same messages. One of the advantages in the delivery of this project is that it does not rely on the school system and its overcrowded curricula or a funded community program, for its implementation. The limitations of available time of teachers, training required, and availability of facilitators and youth workers to deliver prevention programs, are often barriers for dissemination to the wider community.

Knowing you, Knowing me is an online, social media environment, built with a similar style and functionality to Facebook, but automated so that the mother and daughter interact with a virtual character, called Rose, who leads them through the intervention. In KYKM, Rose is a fairy and is presented as a “talk show” host using animated webisodes (short video episodes ranging from 2.6 to 6 min, depending on the level). The decision to use an ethereal character such as a fairy to facilitate the game capitalizes on the engagement that adolescent girls have with magical characters in television shows and cinema (e.g., Twilight, Harry Potter, Once Upon a Time, etc). As a fairy, Rose isn't a human adult authority figure and can provide advice to both the mother and daughter. This is a distinct point of difference between KYKM and other such games (Schinke et al., 2009).

From Figure 1, it can be seen that Rose is joined by a mother and her daughter, Claire and Lucy respectively, who discuss key themes of the game and provide both mother and daughter perspectives.

Figure 1. Webisode from the Knowing you, Knowing me, talk show with Rose (right), and daughter, Lucy (left) and mother, Claire (middle).

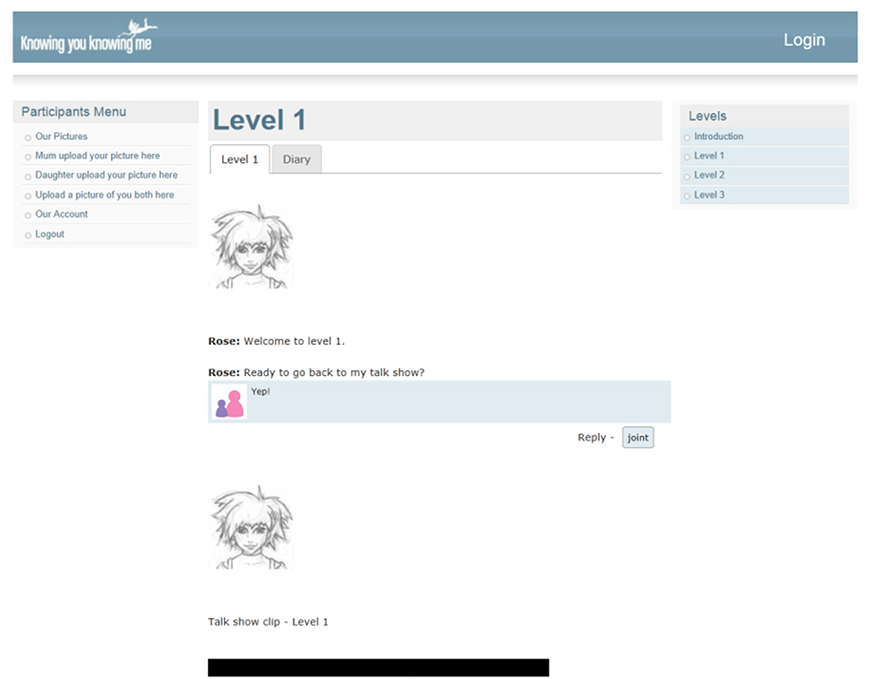

Through the KYKM Facebook-styled wall, Rose asks the participating mother and daughter to post to her (respective) wall to reflect on webisodes and to also plan activities together to practice skills (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Screenshot of Rose's Knowing you, Knowing me, social media wall, with posts from mother and daughter participants.

Mothers and Daughters can upload images of themselves, individually and together, which are displayed alongside their posts, and can also share images in a gallery. They complete the levels together at one screen, but can also return and converse online through the program.

Participants engage in games and activities in Knowing you, Knowing me designed to integrate the educational content into their relationships. Importance is placed on the mother and the daughter listening to one another, spending time together, understanding each other's point of view, negotiating through conflict toward mutually agreeable outcomes and giving one another encouragement, support, compliments and personal favors.

The three levels (modules) in the game are:

(1) Participate in effective communication,

(2) Develop healthy relationships, and

(3) Manage risky behavior in the social environment.

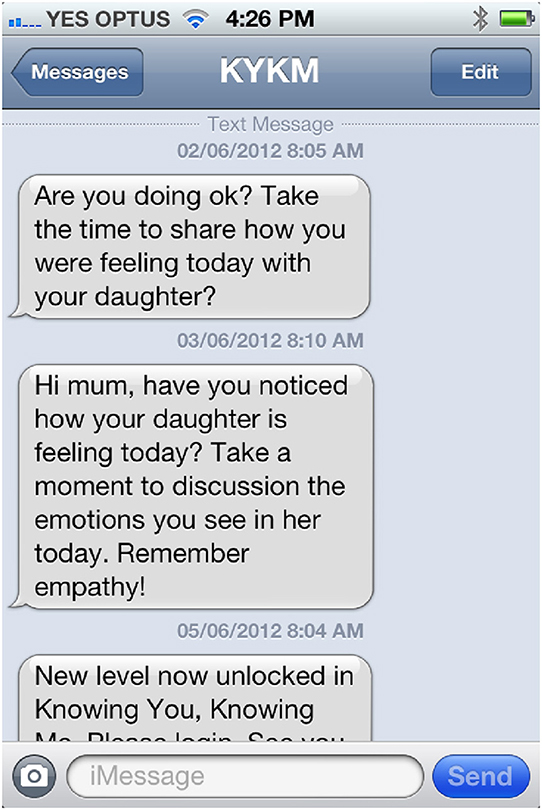

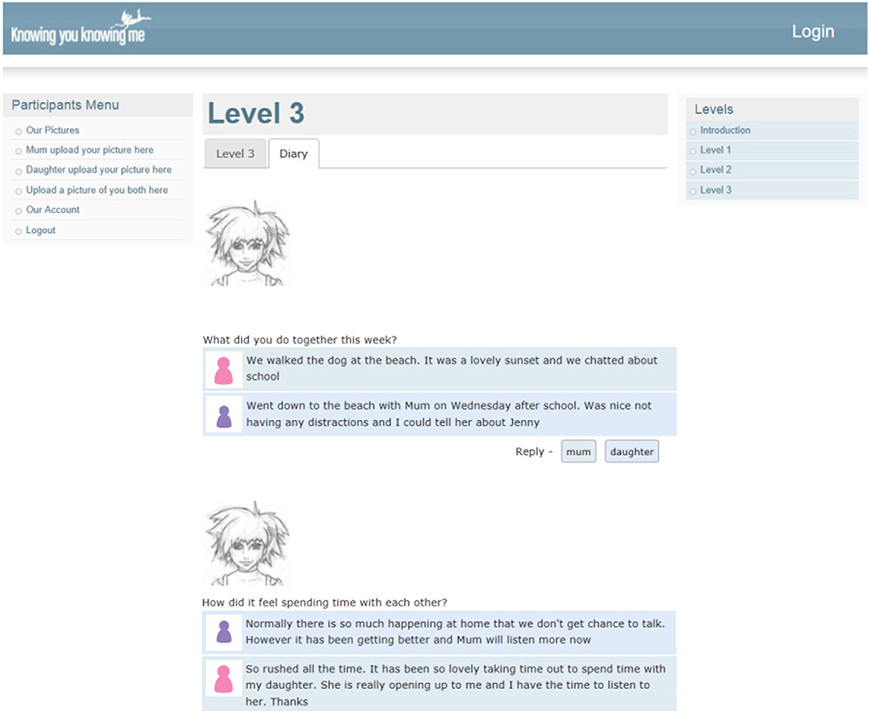

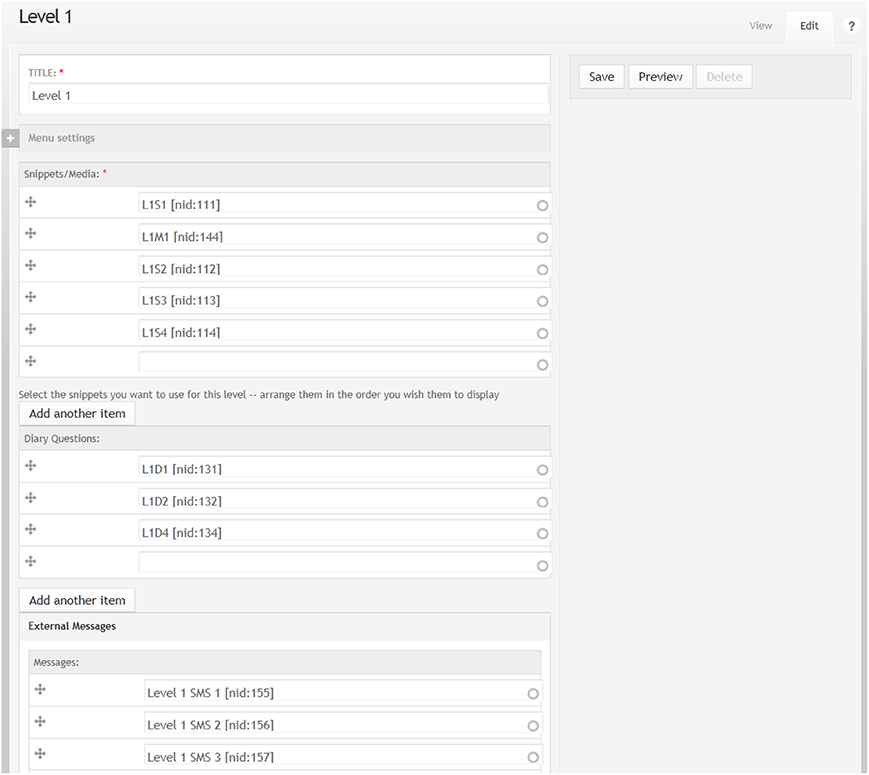

The administration environment allows the research team to directly modify what, when, and how Rose discusses with the mother and daughter participants, including automatically triggering of conversations, SMS messages (see Figure 3), questions, weblinks, webisodes, diaries (see Figure 4) and unlocking of levels (see Figure 5), and new levels and content can be easily added without rebuilding the system.

Figure 3. Screenshot of mother's mobile phone showing two SMS messages and new level unlocked message.

Figure 4. Knowing you, Knowing me diary page with posting from mother and daughter reflecting on their experience during the week.

Figure 5. Administrator content management system with snippets (text), media (images and videos), diary questions and SMS messages.

The Knowing you, Knowing me game contains information to develop healthy interpersonal communication, respect, trust, negotiation setting limits, values, and analyzing situations. The game provides opportunities to personalize information by having mothers and daughters identify their own strengths in themselves and their relationship and identify their personal values. Additionally, there are opportunities to recognize social pressures and influences by having mothers and daughters examine images and messages used to define gender identity, mother-daughter relationships, female alcohol use and demonstrate how to be resilient to these pressures. The game provides consistent reinforcement of positive norms through the use of process praise rather than personal praise, and opportunities to learn and practice skills including refusal skills and delaying skills.

The information and activity contained in the game offers mothers and daughters a “toolbox” for handling a variety of domestic situations, from the most basic communication skills (such as listening and responding in a timely manner) to the more difficult and complex communication tasks of conflict resolution and negotiation within the scope of the problem.

A major limitation of this report is that KYKM is untested in the community of mothers and daughters that it has been developed to assist. The authors are trialing the game in Australia and would welcome collaborative approaches locally and globally. The game is available now and freely accessible to interested researchers. This report is the first step in achieving this aim and in widening the scope of the game's application.

One strength of the game design is that KYKM has the capacity to grow into many different areas beyond communication skills and alcohol use in adolescence. In a separate study using focus groups of mothers and daughters (Katsikitis et al., 2013b), valuable information was shared with the investigators with regard to future topics for Claire, Lucy and Rose to tackle (e.g., bullying, body image, friendships etc.). In addition, young adolescent boys and the relationship they have with their fathers (and/or their mothers) is also worthy of consideration. The authors recommend that this game be used as a positive psychology “intervention” in future studies so as to evaluate its properties and utility beyond the gaming circles, and investigate the possibility that KYKM may be useful in health promotion. It is anticipated that with further research in this area, KYKM has the potential to be a valid, meaningful and purposeful game into the future.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding support for this project from Queensland Health, DRUG-ARM Australasia, auDA Foundation, Drink Safe Coalition, Sunshine Coast Youth Partnership and Project support from the following organizations: Various Artists and Virtual Obsession.

Barber, J. G., Bolitho, F., and Bertrand, L. (2001). Parent-child synchrony and adolescent adjustment. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 18, 51–69. doi: 10.1023/A:1026673203176

Benson, M. J., Harris, P. B., and Rogers, C. S. (1992). Identity consequences of attachment to mothers and fathers among late adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2, 187–204. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0203_1

Boyd, C. J. (1989). Mothers and daughters: a discussion theory and research. J. Marriage Fam. 51, 291–301. doi: 10.2307/352493

Caprara, G. V., Regallia, C., and Bandura, A. (2002). Longitudinal impact of perceived self-regulatory efficacy on violent conduct. Eur. Psychol. 7, 63–69. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.7.1.63

De Vulpian, A. (2005). “Listening to ordinary people,” in Paper Presented at the International Conference for Organizational Learning (Vienna).

Erel, O., and Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 118, 108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108

Fukkink, R., and Hermas, J. (2009). Counselling children on a help line chatting or calling. J. Community Psychol. 37, 939–948. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20340

Katsikitis, M., Bignell, K., Rooskov, N., Elms, L., and Davidson, G. (2013a). The family strengthening programme: influences on parental mood, parental sense of competence and family functioning. Adv. Mental Health 11, 143–151. doi: 10.5172/jamh.2013.11.2.143

Katsikitis, M., Jones, C., and Muscat, M. (2013b). “Knowing you, knowing me: a game tyo mitigate risk-taking in adolescent girls,” in Presentation at the International Association for Women's Mental Health (Lima).

Koning, I. M., Vollebergh, W. A. M., Smit, F., Verdurmen, J. E. E., Van Den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Ter Bogt, T. F. M., et al. (2009). Preventing heavy alcohol use in adolescents (PAS): cluster randomised trial of parent and student intervention offered separately and simultaneously. Addiction 104, 1669–1678. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02677.x

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., and Van Kammen, W. B. (1998). Antisocial Behaviour and Mental Health Problems: Explanatory Factors in Childhood and Adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Luthens, F., Avy, J., and Patera, J. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 7, 209–221. doi: 10.5465/AMLE.2008.32712618

Newton, N. C., Andrews, G., Teeson, M., and Vogl, L. (2009b). Delivering prevention for alcohol and cannabis using the internet: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prevent. Med. 48, 579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.009

Newton, N. C., Vogl, L. E., Teeson, M., and Andrews, G. (2009a). CLIMATE schools: alcohol module: cross validation of a school-based prevention programme for alcohol misuse. Aust. N.Z. J. Psychiatry 43, 201–207. doi: 10.1080/00048670802653364

Orbuch, T. L., Thornton, A., and Cancia, J. (2000). The impact of marital quality, divorce, and remarriage on the relationships between parents and their children. Marriage Family Rev. 29, 221–246. doi: 10.1300/J002v29n04_01

Schinke, S., Cole, K., and Fang, L. (2009). Gender specific intervention to reduce underage drinking among early adolescent girls: a test of a computer-mediated program. Alcohol Drugs 70, 70–77.

Keywords: gaming, communication, relationships, positive psychology

Citation: Katsikitis M, Jones C, Muscat M and Crawford K (2014) Knowing You, Knowing Me (KYKM): an interactive game to address positive mother-daughter communication and relationships. Front. Psychol. 5:721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00721

Received: 29 November 2013; Accepted: 23 June 2014;

Published online: 11 July 2014.

Edited by:

Natasha Kirkham, Birkbeck College, UKReviewed by:

Graham Schafer, University of Reading, UKCopyright © 2014 Katsikitis, Jones, Muscat and Crawford. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mary Katsikitis, Psychology Department, ML32, University of the Sunshine Coast, Locked Bag 4, Maroochydore DC, QLD 4558, Australia e-mail:bWthdHNpa2lAdXNjLmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.