- Department of Psychology, Center for Cognitive Science, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

This paper proposes a historical excursus of studies that have investigated the therapeutic alliance and the relationship between this dimension and outcome in psychotherapy. A summary of how the concept of alliance has evolved over time and the more popular alliance measures used in literature to assess the level of alliance are presented. The proposal of a therapeutic alliance characterized by a variable pattern over the course of treatment is also examined. The emerging picture suggests that the quality of the client–therapist alliance is a reliable predictor of positive clinical outcome independent of the variety of psychotherapy approaches and outcome measures. In our opinion, with regard to the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy, future research should pay special attention to the comparison between patients’ and therapists’ assessments of the therapeutic alliance. This topic, along with a detailed examination of the relationship between the psychological disorder being treated and the therapeutic alliance, will be the subject of future research projects.

Introduction

The main aim of this paper is to propose a historical excursus of the most relevant literature which has investigated the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and outcome in psychotherapy.

A challenge by Eysenck (1952), who claimed that the efficacy of psychotherapy had not been demonstrated and that any improvements were the result of so-called spontaneous remission, stimulated significant developments in the study of outcomes in psychotherapy. Furthermore, research into the relationship between the process and outcome of psychotherapy has frequently attempted to explain the non-specific factors theorized by Strupp and Hadley (1979) which can have a significant impact on the outcome of different treatments. This viewpoint was more recently confirmed by Strupp (2001), who showed that the outcome of a psychotherapeutic process is often influenced by so-called non-specific factors, namely, the personal characteristics of the therapist and the positive feelings that arise in the patient – feelings which can lead to the creation of a positive therapeutic climate from an emotional and interpersonal perspective.

From a different perspective, Orlinsky and Howard (1986), in their review of the research into process and outcome in psychotherapy, seek to respond to the following question: what is effectively therapeutic about psychotherapy? Here, it is important to note that research in the field of psychotherapy is usually classified as outcome research and process research. Outcome research analyses the results of the therapy, whereas process research investigates the various aspects of the therapeutic process, which can also be measured during the course of therapy regardless of outcome. This process is what takes place between, and within, the patient and therapist during the course of their interaction (Orlinsky and Howard, 1986). These two areas of research should not really be considered as separate, but rather as two sides of a coin. Migone (1996) distinguishes three partially overlapping phases in the history of psychotherapy research: a first phase, between the 1950s and 1970s, when research focused on the outcome of psychotherapy and there was a proliferation of meta-analysis; a second phase between the 1960s and 1980s in which there was a growing interest for research into the relationship between process and outcome (the Vanderbilt Project is the most famous example of this); and a third phase from the 1970s onward, in which interest shifted to the therapeutic process and the desire for a greater understanding of the “micro-processes” involved in therapy.

Before examining the most influential instruments designed to measure the therapeutic alliance and their correlations with outcome, we will summarize the concept of alliance as it has evolved over time.

Evolution of the Concept of Therapeutic Alliance

According to Horvath and Luborsky (1993), the concept of therapeutic alliance can be traced back to Freud’s (1913) theorization of transference. Initially regarded as purely negative, Freud, in his later works, adopted a different stance on the issue of transference and considered the possibility of a beneficial attachment actually developing between therapist and patient, and not as a projection. Along the same lines, Zetzel (1956) defines the therapeutic alliance as a non-neurotic and non-transferential relational component established between patient and therapist. It allows the patient to follow the therapist and use his or her interpretations. Similarly, Greenson (1965) defines the working alliance as a reality-based collaboration between patient and therapist. Other authors (Horwitz, 1974; Bowlby, 1988), expanding on the concept of Bibring (1937), considered the attachment between therapist and patient as qualitatively different to that based on childhood experiences. These authors made a distinction between transference and the therapeutic (or working) alliance, and this distinction later extended beyond the analytical framework (Horvath and Luborsky, 1993).

Rogers (1951) defines what he considered to be the active components in the therapeutic relationship: empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard. These were seen as the ideal conditions offered by the therapist but were later shown to be specifically essential for client-centered therapy (Horvath and Greenberg, 1989; Horvath and Luborsky, 1993). While Rogers stressed the therapist’s role in the relationship, other works focused on the theory of the influence of social aspects. The work of Strong (1968) was based on the hypothesis that if the patient is convinced of the therapist’s competence and adherence, this will give the latter the necessary influence to bring about changes in the patient.

Recognition of the fact that different types of psychotherapy often reveal similar results gave rise to the hypotheses regarding the existence of variables common to all forms of therapy, rekindling interest in the alliance as a non-specific variable. Luborsky (1976) proposes a theoretical development of the concept of alliance, suggesting that the variations in the different phases of therapy could be accounted for by virtue of the dynamic nature of the alliance. He distinguished two types of alliance: the first, found in the early phases of therapy, was based on the patient’s perception of the therapist as supportive, and a second type, more typical of later phases in the therapy, represented the collaborative relationship between patient and therapist to overcome the patient’s problems – a sharing of responsibility in working to achieve the goals of the therapy and a sense of communion.

The definition of the therapeutic alliance proposed by Bordin (1979) is applicable to any therapeutic approach and for this reason is defined by Horvath and Luborsky (1993) as the “pan-theoretical concept.” Bordin’s formulation underlines the collaborative relationship between patient and therapist in the common fight to overcome the patient’s suffering and self-destructive behavior. According to the author, the therapeutic alliance consists of three essential elements: agreement on the goals of the treatment, agreement on the tasks, and the development of a personal bond made up of reciprocal positive feelings. In short, the optimal therapeutic alliance is achieved when patient and therapist share beliefs with regard to the goals of the treatment and view the methods used to achieve these as efficacious and relevant. Both actors accept to undertake and follow through their specific tasks. The other two components of the alliance can only develop if there is a personal relationship of confidence and regard, since any agreement on goals and tasks requires the patient to believe in the therapist’s ability to help him/her and the therapist in turn must be confident in the patient’s resources. Bordin also suggests that the alliance will influence outcome, not because it is healing in its own right, but as an ingredient which enables the patient to accept, follow, and believe in the treatment. This definition offers an alternative to the previous dichotomy between the therapeutic process and intervention procedures, considering them interdependent.

Only a few studies have examined the relationship between alliance and outcome in group psychotherapy. One conceptualization of therapeutic alliance in group psychotherapy follows Bordin’s theory, transferring this multifactorial construct from an individual to a group setting. The first difference is that in group psychotherapy we have multiple therapeutic agents: the therapist (usually two co-therapists), the members of the group, and the group as a whole. Thus, we have to consider more than one relational level within the group: member to therapist alliance (the same as individual therapy), member to member alliance, group to therapist alliance, and member to other members as a whole alliance. Under this complexity of adapting the alliance concept to a group context, some authors have found a solution: the systemic model of alliance according to Pinsof (1988) Pinsof and Catherall (1986). These authors have adapted Bordin’s model to multiple interpersonal subsystems. These subsystems involve (a) a self-to-therapist alliance, (b) group-to-therapist alliance, (c) self-to-members alliance, and (d) other-to-therapist alliance. Under this point of view, an alliance can be conceptualized as the totality of the alliances formed (Gillaspy et al., 2002).

In a comparison of therapeutic factors in group and individual treatment processes by Holmes and Kivlighan (2000), relationship components have emerged as being more prominent in group psychotherapy, whereas emotional awareness–insight and problem definition change are more central to the process of individual treatment. As such, we can say that clients in group therapies may attach greater importance to relationship factors.

When defining therapeutic alliance in a group context, it is necessary to take into account the comparison with group cohesion, another central construct that is often confused with alliance. Definitions of cohesion have covered a wide range of features, sometimes overlapping the alliance construct. Yalom (1995) speaks of a sense of support, trust, belonging in the group, and also “the analog of relationship in individual therapy”; Budman et al. (1989) refer to cohesion as working together toward a therapeutic goal and engagement around common themes. They found that alliance and group cohesion were closely related and that both were strongly related to improved self-esteem and reduced symptomatology. Crowe and Grenyer (2008) make a distinction between cohesion and alliance, stating that group cohesion refers to the relationship between all members of the group, including the therapists (Burlingame et al., 2011), while working alliance, by contrast, refers to the relationship between the therapist and group member. Marziali et al. (1997) tested the contribution of therapeutic alliance and group cohesion (both based on self-report) to outcome in group therapies for borderline personality disorder. Cohesion and alliance were correlated significantly and both predicted a successful outcome, although the alliance accounted for more outcome variance.

Measuring the Alliance

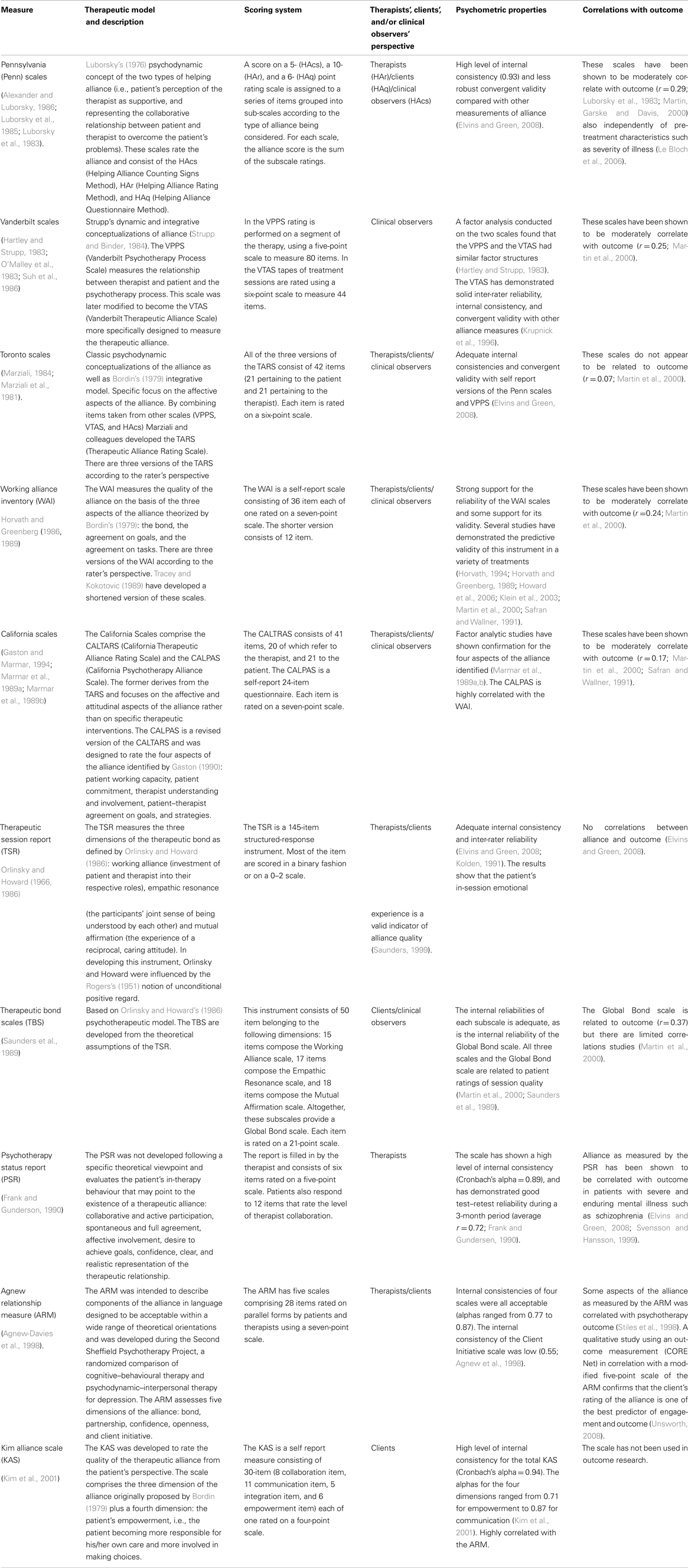

Table 1 shows the alliance measures more frequently used to assess the level of alliance and their correlations with outcome. Most of them are based on the theoretical assumptions previously described.

Any attempt to measure something as complex as therapeutic alliance involves a series of conceptual and methodological shortcomings, which have probably hindered the development of research in this field. Single-case research is one method used to investigate this theoretical construct, but implies some methodological drawbacks regarding the simultaneous treatment of several factors, the need for an adequate number of repeated measurements, and the generalizability of results. Meta-analysis is a possible research strategy that can be used to obtain the combined results of studies on the same topic. However, it is important to remember that meta-analysis is more valid when the effect being investigated is quite specific. According to Migone (1996), another hindrance is the so-called Rashomon effect (named after the 1950 film by Akira Kurosawa): each single aspect of therapeutic alliance may be perceived very differently by the therapist, patient, and clinical observer, which raises the question of objectivity.

Di Nuovo et al. (1998) propose some methodological changes to increase the utility of research findings, namely, omitting the use of methodological “control” techniques with comparisons between groups, re-evaluating single-case research, reconsidering the use of longitudinal studies, and using systematic replication and meta-analysis to guarantee the generalizability of results, even with single cases.

In spite of the difficulties involved in this type of research, Table 1 shows that numerous instruments have been developed to analyses the therapeutic alliance. Though designed by independent research teams, there is often good correlation between the scales used to rate the therapeutic alliance, which reveal that these instruments tend to assess the same underlying process (Martin et al., 2000). Fenton et al. (2001) compared the predictive validity of six instruments (CALPAS, Penn Scale, VTAS, WAI-Observer, WAI-therapist, WAI-Client) and found that all the measurement instruments used by raters (six trained clinicians served as independent raters for this study) were strong predictors of outcome. None of their findings suggest that any one instrument was a stronger predictor of outcome than the others, in relation to the type of therapy being considered.

It is interesting to note that although almost all of these scales were originally designed to examine the perspective of only one member of the patient–therapist–observer triad, they were later extended or modified to rate perspectives that were not previously considered. In short, some scales analyses specific theoretical concepts of the alliance (Penn scales, WAI, CALPAS, TBS), whereas others use a more eclectic construct (VPPS, VTAS, TARS). The number of items included in the scales varies considerably (between 6 and 145 items), as do the dimensions of the alliance investigated (e.g., two in the Penn scales; three in the WAI, TSR, and TBS; four in the CALPAS and KAS; and five in the ARM). According to Martin et al. (2000), the most frequently used scales in individual psychotherapy are the WAI, CALPAS, and Penn scales, followed by the Vanderbilt scales, TARS, and TBS.

Different approaches for the evaluation of alliance coexist in group psychotherapy. One of them is derived from individual psychotherapy. Johnson et al. (2005) used the WAI to refer to relationships with other group members; it was called the Member–Member WAI. The WAI-based scale used to measure relationships with group leaders was called the Member–Leader WAI. The CALPAS Group used by Crowe and Grenyer (2008) consisted of four subscales: patient working capacity, patient commitment, working strategy consensus, and member understanding and involvement.

Although a comparison between different treatment modalities is a topic beyond the scope of this paper, it is worth noting that in the late 1980s, some authors (Marmar et al., 1989a,b) failed to demonstrate significant differences between behavioral, cognitive, and brief psychodynamic therapies in the level of alliance as measured by CALPAS. However, subsequently, Raue et al. (1997), when comparing psychodynamic–interpersonal and cognitive–behavioral therapy sessions, found that observers rated the cognitive–behavioral group significantly higher on the WAI. This latter study compared 57 clients, diagnosed with major depression and receiving either psychodynamic–interpersonal or cognitive–behavioral therapy: the cognitive–behavioral sessions were rated as having better therapeutic alliances than the psychodynamic ones. They argue that these findings could reflect the effort in cognitive–behavioral therapy to give clients positive experiences and to emphasize positive coping strategies. A more recent comparison was suggested by Spinhoven et al. (2007), whose aim was to evaluate the therapeutic alliance in schema-focused therapy (Young et al., 2003; Nadort et al., 2009) and transference-focused psychotherapy (Yeomans et al., 2002). Results obtained by evaluating alliance through WAI-Client and WAI-therapist after 3, 15, and 33 months, showed clear alliance differences between treatments, suggesting that the quality of the alliance was affected by the nature of the treatment. Schema-focused therapy, with its emphasis on a nurturing and supportive attitude of therapist and the aim of developing mutual trust and positive regard, produced a better alliance according to the ratings of both therapists and patients. Ratings by therapists during early treatment, in particular, were predictive of dropout, whereas growth of the therapeutic alliance as experienced by patients during the first part of therapy, was seen to predict subsequent symptom reduction.

Phases of the Alliance during the Therapeutic Process and the Relationship with the Outcome

There is much debate on the role of the therapeutic alliance during the psychotherapeutic process. It may in fact be a simple effect of the temporal progression of the therapy rather than an important causal factor. On the basis of this hypothesis, we would expect a development in the alliance to be characterized by a linear growth pattern over the course of the therapy, and alliance ratings obtained in the early phases to be weaker predictors of outcome than those obtained toward the end of the therapy. However, according to the findings of numerous researchers, this is not the case. Safran et al. (1990) conclude that the positive outcome of therapy was more closely associated with the successful resolution of ruptures in the alliance than with a linear growth pattern as the therapy proceeds. Horvath and Marx (1991) describe the course of the alliance in successful therapies as a sequence of developments, breaches, and repairs. According to Horvath and Symonds (1991), the extent of the relationship between alliance and outcome was not a direct function of time: they find that measurements obtained during the earliest and most advanced counseling sessions were stronger predictors of outcome than those obtained during the middle phase of therapy.

The results of these studies have led researchers to consider the existence of two important phases in the alliance. The first phase coincides with the initial development of the alliance during the first five sessions of short-term therapy and peaks during the third session. During the first phase, adequate levels of collaboration and confidence are fostered, patient and therapist agree upon their goals, and the patient develops a certain degree of confidence in the procedures that constitute the framework of the therapy. In the second phase the therapist begins to challenge the patient’s dysfunctional thoughts, affects, and behavior patterns, with the intent of changing them. The patient may interpret the therapist’s more active intervention as a reduction in support and empathy, which may weaken or rupture the alliance. The deterioration in the relationship must be repaired if the therapy is to be successful.

This model implies that the alliance can be damaged at various times during the course of therapy and for different reasons. The effect on therapy differs, depending on when the difficulty arises. In the early phases, it may create problems in terms of the patient’s commitment to the process of therapy. In this case, the patient may prematurely terminate the therapy contract. In more advanced phases of therapy, an interruption in the alliance may be triggered by a number of therapeutic scenarios, including when patients’ thoughts and emotions have been invalidated in some way. Within a transference-focused psychotherapy framework, the patient’s expectations of the therapist may be unrealistic and idealized, which may therefore hinder their ability to use the therapy to deal with important issues. In situations such as this, the actual therapeutic alliance regularly and repetitively reflects the patient’s unresolved conflicts.

According to Safran and Segal (1990), many therapies are characterized by at least one or more ruptures in the alliance during the course of treatment. Randeau and Wampold (1991) analyses the verbal exchanges between therapist and patient pairs in high and low-level alliance situations and find that, in high-level alliance situations, patients responded to the therapist with sentences that reflected a high level of involvement, while in low-level alliance situations, patients adopted avoidance strategies. Although some studies are based on a very limited number of cases, the results appear consistent: the therapist’s focus on the patient’s conflictual behavior patterns and the patient’s involvement rather than avoidance in responding to these challenges, are factors that contribute to improving the therapeutic alliance. Fluctuations in the alliance, especially in the middle phase, thus appear to reflect the re-emergence of the patient’s dysfunctional avoidant strategies and the task of the therapist is to recognize and resolve these conflicts.

While recent theorists have stressed on the dynamic nature of the therapeutic alliance over time, most researchers have used static measures of alliance. There are currently several therapy models that consider the temporal dimension of the alliance, and these can be divided into two groups: the first comprises those addressing transitional fluctuations in alliance levels, while the second consists of those concerned with the more global dynamics of the development of the alliance.

Few studies have analyzed alliance at different stages in the treatment process. Hartley and Strupp (1983) examined ratings obtained during the first session and then during sessions representing 25, 50, 75, and 100% of the treatment, over the course of short-term therapies. Among patients who completed the therapy successfully, there was an increase in the alliance rating between the first session and the session representing the 25% mark, whereas among unsuccessful patients, the alliance rating declined over the same period. According to the results proposed by Tracey (1989), the more successful the outcome, the more curvilinear the pattern of client and therapist session satisfaction (high–low–high) over the course of treatment. When the outcome was worse, the curvilinear pattern was weaker.

Horvath et al. (1990) posit an initial phase in which the alliance was strong, followed by a period of decline, and a subsequent period of repair. Kivlighan and Shaughnessy (1995) use the hierarchical linear modeling method (an analysis technique for studying the process of change in studies where measurements are repeated) to analyses the development of the alliance in a large number of cases. According to their findings, some dyads presented the high–low–high pattern, others the opposite, and a third set of dyads had no specific pattern, although there appeared to be a generalized fluctuation in the alliance during the course of treatment.

In recent years, researchers have analyzed fluctuations in the alliance, in the quest to define patterns of therapeutic alliance development. Kivlighan and Shaughnessy (2000) distinguish three patterns of therapeutic alliance development: stable alliance, linear alliance growth, and quadratic or “U-shaped pattern” alliance growth. They based their analysis on the first four sessions of short-term therapy and focused their attention on the third pattern, in that this appeared to be correlated with the best therapeutic outcomes.

In further studies of this development pattern, Stiles et al. (2004) analyzed therapeutic alliance growth during the course of short-term treatment of depressed patients, drawn from the Second Sheffield Psychotherapy Project, who received cognitive–behavioral and psychodynamic–interpersonal therapy. Unlike Kivlighan and Shaughnessy, these authors considered therapies consisting of 8 and 16 sessions, using the ARM to rate the therapeutic bond, partnership, and confidence, disclosure, and patient initiative. Cluster analysis yielded four therapeutic alliance development patterns, two of which matched Kivlighan and Shaughnessy’s patterns: stable alliance; linear alliance growth with high variability between sessions; negative growth with high variability between sessions; and positive growth with low variability between sessions. No significant correlation was observed between any of the four patterns and the therapeutic outcome. However, the authors observed a cycle of therapeutic alliance rupture–repair events in all cases: very frequent ruptures followed by rapid resolution processes, that is, V-shaped patterns. On the basis of this characteristic, the authors hypothesize that the V-shaped alliance patterns may be correlated with positive outcomes. In particular, Stiles et al. (2004) provide the first statistical demonstration of the hypothesis previously formulated by Safran and Muran (2000) and Samstag et al. (2004), where the alliance ruptures represented opportunities for clients to learn about their problems relating to others, and repairs represented such opportunities having been taken in the here-and-now of the therapeutic relationship.

The results of the study by De Roten et al. (2004) produced two patterns of alliance development (linear and stable), but no quadratic (U-shaped) or rapid rupture–repair (V-shaped) patterns emerged. The authors provided a possible explanation for these results by attributing them to the type of psychotherapy being investigated (the Brief Psychodynamic Investigation proposed by Gilliéron, 1989, which is a manual on a very brief psychotherapeutic four-session intervention) and the type of sample (psychiatric patients). Moreover, a new rating scale, the HAq, had replaced those that were used previously (WAI and ARM). According to De Roten et al. (2004), these results were in line with Horvath’s view of the alliance as a constructive process, rather than with the views of Gelso and Carter (1994) and Safran and Muran (1996) concerning the rupture and repair of alliances, in which change was a better predictor of stability outcomes. De Roten et al. (2004) suggest that a process characterized by ruptures and repairs was more likely to occur in long-term psychodynamic treatment, particularly during phases of in-depth work.

According to Castonguay et al. (2006), patterns of therapeutic alliance development require further investigation, in order to understand how and whether the various patterns are a cause, effect, or manifestation of improvement. This has supported the idea that therapeutic alliance may be characterized by a variable pattern over the course of treatment, and led to the establishment of a number of research projects to study this phenomenon.

Discussion and Conclusion

According to their meta-analysis based on the results of 24 studies, Horvath and Symonds (1991) demonstrate the existence of a moderate but reliable association between good therapeutic alliance and positive therapeutic outcome. More recent meta-analyses of studies examining the linkage between alliance and outcomes in both adult and youth psychotherapy (Martin et al., 2000; Shirk and Karver, 2003; Karver et al., 2006) have confirmed these results and also indicated that the quality of the alliance was more predictive of positive outcome than the type of intervention (but for slightly different results in youth psychotherapy see McLeod, 2011).

Some theorists have defined the quality of the alliance as the “quintessential integrative variable” of a therapy (Wolfe and Goldfried, 1988), and in the present state, it seems possible to affirm that the quality of the client–therapist alliance is a consistent predictor of positive clinical outcome independent of the variety of psychotherapy approaches and outcome measures (Horvath and Bedi, 2002; Norcross, 2002). Thus, it is not by chance that in their meta-analysis, Horvath and Luborsky (1993) conclude that two main aspects of the alliance were measured by several scales regardless of the theoretical frameworks and the therapeutic models: personal attachments between therapist and patient, and collaboration and desire to invest in the therapeutic process.

In our opinion, regarding the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and the outcome of psychotherapy, future research should pay special attention to the comparison between patients’ and therapists’ assessments of the therapeutic alliance: these have often been found to differ, and evidence suggests that the patient’s assessment is a better predictor of the outcome of psychotherapy (Castonguay et al., 2006). In Horvath’s (2000) opinion, this might be explained by the limitations of assessment procedures, since the rating scales are usually validated on the basis of patient data, whereas the therapist views the relationship through a “theoretical lens,” thus tending to assess the relationship according to what the theory suggests is a good therapeutic relationship or according to the assumptions about the signs that indicate the presence or absence of the desirable relationship qualities. On the other hand, the patients’ assessments tend to be more subjective, atheoretical, and based on their own past experiences in similar situations. This accounts for the difficulties associated with the concept of alliance, which is built interactively, and so any assessment must also consider the mutual influence of the participants. In a helpful contribution, Hentschel (2005) points out that the problematic aspect of empirical studies investigating the alliance is their tendency to view the alliance construct as a treatment strategy and a predictor of therapeutic outcome: if the therapist is instructed, for instance, on methods of increasing the level of alliance, and is then asked to rate the alliance, this can lead to a contamination of the results. The use of neutral observers or the creation of counterintuitive studies is therefore recommended.

From this historical excursus, it is clear that research into the assessment of the psychotherapeutic process is alive and well. The development of a dynamic vision of the concept of therapeutic alliance is also apparent. The work of theorists and researchers has contributed toward enriching the definition of therapeutic alliance, first formulated in 1956. Research aimed at analyzing the components that make up the alliance continues to flourish and develop. Numerous rating scales have been designed to analyses and measure the therapeutic alliance, scales that have enabled us to gain a better understanding of the various aspects of the alliance and observe it from different perspectives: from that of the patient, therapist, and observer. Attention has recently turned toward the role of the therapeutic alliance in the various phases of therapy and the relationship between alliance and outcome.

So far, few studies have regarded long-term psychotherapy involving many counseling sessions. This topic, along with a more detailed examination of the relationship between the psychological disorder being treated and the therapeutic alliance, will be the subject of future research projects. Equally important, in our opinion, will be the findings of studies regarding drop-out and therapeutic alliance ruptures, which must necessarily consider the differences between that perceived by the patient and that perceived by the therapist.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mauro Adenzato for his valuable comments and suggestions to an earlier version of this article. This work was supported by University of Turin (Ricerca scientifica finanziata dall’Università).

References

Agnew-Davies, R., Stiles, W. B., Hardy, G. E., Barkham, M., and Shapiro, D. A. (1998). Alliance structure assessed by the Agnew Relationship Measure (ARM). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 37, 155–172.

Alexander, L. B., and Luborsky, L. (1986). “The Penn helping alliance scales,” in The Psychotherapeutic Process: A Research Handbook, eds L. S. Greenberg and W. M. Pinsoff (New York: Guilford Press), 325–366.

Bibring, E. (1937). On the theory of the results of psychoanalysis. Int. J. Psychoanal. 18, 170–189.

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy (Chic.) 16, 252–260.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Budman, S. H., Soldz, S., Demby, A., Feldstein, M., Springer, T., and Davis, M. S. (1989). Cohesion, alliance and outcome in group psychotherapy. Psychiatry 52, 339–350.

Burlingame, G. M., McClendon, D. T., and Alonso, J. (2011). Cohesion in group therapy. Psychotherapy 48, 34–42.

Castonguay, L. G., Constantino, M. J., and Grosse Holtforth, M. (2006). The working alliance: where are we and where should we go? Psychotherapy (Chic.) 43, 271–279.

Crowe, T. P., and Grenyer, B. F. S. (2008). Is therapist alliance or whole group cohesion more influential in group psychotherapy outcomes? Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 15, 239–246.

De Roten, Y., Fischer, M., Drapeau, M., Beretta, V., Kramer, U., Favre, N., and Despland, J.-N. (2004). Is one assessment enough? Patterns of helping alliance development and outcome. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 11, 324–331.

Di Nuovo, S., Lo Verso, G., Di Blasi, M., and Giannone, F. (1998). Valutare le psicoterapie: La ricerca italiana. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Elvins, R., and Green, J. (2008). The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: an empirical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 1167–1187.

Eysenck, H. J. (1952). The effects of psychotherapy: an evaluation. J. Consult. Psychol. 16, 319–324.

Fenton, L. R., Cecero, J. J., Nich, C., Frankforter, T., and Carroll, K. (2001). Perspective is everything: The predictive validity of six working alliance instruments. J. Psychother. Pract. Res. 10, 262–268.

Frank, A. F., and Gunderson, J. G. (1990). The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia. Relationship to course and outcome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 47, 228–236.

Freud, S. (1913). “On the beginning of treatment: further recommendations on the technique of psychoanalysis,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. J. Strachey (Trans.) (London: Hogarth Press), 122–144.

Gaston, L. (1990). The concept of the alliance and its role in psychotherapy: theoretical and empirical considerations. Psychotherapy (Chic.) 27, 143–153.

Gaston, L., and Marmar, C. R. (1994). “The California psychotherapy alliance scales,” in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research and Practice, eds A. O. Horvath and L. S. Greenberg (New York: John Wiley and Sons), 85–108.

Gelso, C. J., and Carter, J. A. (1994). Components of the psychotherapy relationship: their interaction and unfolding during treatment. J. Couns. Psychol. 41, 296–306.

Gillaspy, J. A., Wright, A. R., Campbell, C., Stokes, S., and Adinoff, B. (2002). Group alliance and cohesion as predictors of drug and alcohol abuse treatment outcomes. Psychother. Res. 12, 213–229.

Gilliéron, E. (1989). Short psychotherapy interventions (four sessions). Psychother. Psychosom. 51, 32–37.

Greenson, R. R. (1965). The working alliance and the transference neurosis. Psychoanal. Q. 34, 155–179.

Hartley, D. E., and Strupp, H. H. (1983). “The therapeutic alliance: its relationship to outcome in brief psychotherapy,” in Empirical Studies in Analytic Theories, ed. J. Masling (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 1–38.

Hentschel, U. (2005). Therapeutic alliance: the best synthesizer of social influences on the therapeutic situation? On links to other constructs, determinants of its effectiveness, and its role for research in psychotherapy in general. Psychother. Res. 15, 9–23.

Holmes, S. E., and Kivlighan, D. M. (2000). Comparison of therapeutic factors in group and individual treatment processes. J. Couns. Psychol. 47, 478–484.

Horvath, A. O. (1994). “Empirical validation of Bordin’s pantheoretical model of the alliance: the working alliance inventory perspective,” in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, eds A. O. Horvath and L. S. Greenberg (New York: Wiley), 109–128.

Horvath, A. O. (2000). The therapeutic relationship: from transference to alliance. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 163–173.

Horvath, A. O., and Bedi, R. P. (2002). “The alliance,” in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients, ed. J. C. Norcross (New York: Oxford University Press), 37–69.

Horvath, A. O., and Greenberg, L. S. (1986). “The development of the working alliance inventory,” in The Psychotherapeutic Process: A Research Handbook, eds L. S. Greenberg and W. M. Pinsof (New York: Guilford Press), 529–556.

Horvath, A. O., and Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. J. Couns. Psychol. 36, 223–233.

Horvath, A. O., and Luborsky, L. (1993). The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 61, 561–573.

Horvath, A. O., and Marx, R. W. (1991). The development and decay of the working alliance during time-limited counseling. Can. J. Couns. 24, 240–259.

Horvath, A. O., Marx, R. W., and Kamann, A. M. (1990). Thinking about thinking in therapy: an examination of clients’ understanding of their therapists’ intentions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 58, 614–621.

Horvath, A. O., and Symonds, B. D. (1991). Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 38, 139–149.

Howard, I., Turner, R., Olkin, R., and Mohr, D. C. (2006). Therapeutic alliance mediates the relationship between interpersonal problems and depression outcome in a cohort of multiple sclerosis patients. J. Clin. Psychol. 62, 1197–1204.

Johnson, J. E., Burlingame, G. M., Olsen, J. A., Davies, D. R., and Gleave, R. L. (2005). Group climate, cohesion, alliance, and empathy in group psychotherapy: multilevel structural equation models. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 310–321.

Karver, M. S., Handelsman, J. B., Fields, S., and Bickman, L. (2006). Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: the evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 26, 50–65.

Kim, S. C., Boren, D., and Solem, S. L. (2001). The Kim alliance scale: development and preliminary testing. Clin. Nurs. Res. 10, 314–331.

Kivlighan, D. M., and Shaughnessy, P. (1995). Analysis of the development of the working alliance using hierarchical linear modeling. J. Couns. Psychol. 42, 338–349.

Kivlighan, D. M., and Shaughnessy, P. (2000). Patterns of working alliance development: a typology of client’s working alliance ratings. J. Couns. Psychol. 47, 362–371.

Klein, D. N., Schwartz, J. E., Santiago, N. J., Vivian, D., Vocisano, C., Castonguay, L. G., Arnow, B., Blalock, J. A., Manber, R., Markowitz, J. C., Riso, L. P., Rothbaum, B., McCullough, J. P., Thase, M. E., Borian, F. E., Miller, I. W., and Keller, M. B. (2003). Therapeutic alliance in depression treatment: controlling for prior change and patient characteristics. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 71, 997–1006.

Kolden, G. G. (1991). The generic model of psychotherapy: An empirical investigation of patterns of process and outcome relationships. Psychother. Res. 1, 62–73.

Krupnick, J. L., Sotsky, S. M., Simmons, S., Moyer, J., Elkin, L., and Watkins, J. T. (1996). The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome: findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Programme. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 64, 532–539.

Le Bloch, Y., De Roten, Y., Drapeau, M., and Despland, J. N. (2006). New but improved? Comparison between first and revised version of the helping alliance questionnaire. Schweiz. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatr. 157, 23–28.

Luborsky, L. (1976). “Helping alliances in psychotherapy: the groundwork for a study of their relationship to its outcome,” in Successful Psychotherapy, ed. J. L. Cleghorn (New York: Brunner/Mazel), 92–116.

Luborsky, L., Crits-Cristoph, P., Alexander, L., Margolis, M., and Cohen, M. (1983). Two helping alliance methods for predicting outcomes of psychotherapy: a counting signs vs. a global rating method. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 171, 480–491.

Luborsky, L., McLellan, A. T., Woody, G. E., O’Brien, C. P., and Auerbach, A. (1985). Therapist success and its determinants. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 42, 602–611.

Marmar, C. R., Gaston, L., Gallagher, D., and Thompson, L. W. (1989a). Alliance and outcome in late-life depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 177, 464–472.

Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D., and Gaston, L. (1989b). Towards the validation of the California therapeutic alliance rating system. Psychol. Assess. 1, 46–52.

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., and Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 438–450.

Marziali, E. (1984). Three viewpoints on the therapeutic alliance scales similarities, differences and associations with psychotherapy outcome. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 172, 417–423.

Marziali, E., Marmar, C. R., and Krupnick, J. (1981). Therapeutic alliance scales: development and relationship to psychotherapy outcome. Am. J. Psychiatry 138, 361–364.

Marziali, E., Munroe-Blum, H., and McCleary, L. (1997). The contribution of group cohesion and group alliance to the outcome of group psychotherapy. Int. J. Group Psychother. 47, 475–497.

McLeod, B. D. (2011). Relation of the alliance with outcomes in youth psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 603–616.

Migone, P. (1996). La ricerca in psicoterapia: storia, principali gruppi di lavoro, stato attuale degli studi sul risultato e sul processo. Riv. Sper. Freniatr. Med. Leg. Alien. Ment. 120, 182–238.

Nadort, M., Arntz, A., Smit, J. H., Giesen-Bloo, J., Eikelenboom, M., Spinhoven, P., van Asselt, T., Wensing, M., and van Dyck, R. (2009). Implementation of outpatient schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: study design. BMC Psychiatry 9, 64. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-64

Norcross, J. C. (2002). Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Malley, S. S., Suh, C. S., and Strupp, H. H. (1983). The Vanderbilt psychotherapy process scale: a report on the scale development and a process-outcome study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 51, 581–586.

Orlinsky, D. E., and Howard, K. I. (1966). Psychotherapy Session Report, Form P and form T. Chicago: Institute of Juvenile Research.

Orlinsky, D. E., and Howard, K. I. (1986). “Process and outcome in psychotherapy,” in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behaviour Change: An Empirical Analysis, 3rd Edn, eds S. L. Garfield and A. E. Bergin (New York: Wiley), 311–385.

Pinsof, W. M. (1988). The therapist-client relationship: an integrative system perspective. J. Integr. Eclect. Psychother. 7, 303–313.

Pinsof, W. M., and Catherall, D. R. (1986). The integrative psychotherapy alliance: family, couple and individual therapy scales. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 12, 137–151.

Randeau, S. G., and Wampold, B. E. (1991). Relationship of power and involvement to working alliance: a multiple-case sequential-analysis of brief therapy. J. Couns. Psychol. 38, 107–114.

Raue, P., Goldfried, M., and Barkham, M. (1997). The therapeutic alliance in psychodynamic-interpersonal and cognitive-behavioral therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 65, 582–587.

Safran, J. D., Crocker, P., McMain, S., and Murray, P. (1990). Therapeutic alliances rupture as a therapy event for empirical investigation. Psychotherapy (Chic.) 27, 154–165.

Safran, J. D., and Muran, J. C. (1996). The resolution of ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 64, 477–458.

Safran, J. D., and Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the Therapeutic Alliance: A Relational Treatment Guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Safran, J. D., and Segal, Z. (1990). Interpersonal Process in Cognitive Therapy. New York: Basic Books.

Safran, J. D., and Wallner, L. K. (1991). The relative predictive validity of two therapeutic alliance measures in cognitive therapy. Psychol. Assess. 3, 188–195.

Samstag, L. W., Muran, J. C., and Safran, J. D. (2004). “Defining and identify alliance ruptures,” in Core Processes in Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Advancing Effective Practice, ed. D. P. Charman (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 87–214.

Saunders, S. M. (1999). Clients’ assessment of the affective environment of the psychotherapy session: relationship to session quality and treatment effectiveness. J. Clin. Psychol. 55, 597–605.

Saunders, S. M., Howard, K. I., and Orlinsky, D. E. (1989). The therapeutic bond scales: psychometric characteristics and relationship to treatment outcome. Psychol. Assess. 1, 323–330.

Shirk, S. R., and Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: a meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 71, 452–464.

Spinhoven, P., Giesen-Bloo, J., van Dyck, R., Kooiman, K., and Arntz, A. (2007). The therapeutic alliance in schema-focused therapy and transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75, 104–115.

Stiles, W. B., Agnew-Davies, R., Hardy, G. E., Barkham, M., and Shapiro, D. A. (1998). Relations of the alliance with psychotherapy outcome: findings in the Second Sheffield Psychotherapy Project. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 66, 791–802.

Stiles, W. B., Glick, M. J., Osatuke, K., Hardy, G. E., Shapiro, D. A., Agnew-Davies, R., Rees, A., and Barkham, M. (2004). Patterns of alliance development and the rupture-repair hypothesis: are productive relationships U-shaped or V-shaped? J. Couns. Psychol. 51, 81–92.

Strong, S. R. (1968). Counseling: an interpersonal influence process. J. Couns. Psychol. 15, 215–224.

Strupp, H. H. (2001). Implications of the empirically supported treatment movement for psychoanalysis. Psychoanal. Dialogues 11, 605–619.

Strupp, H. H., and Binder, J. L. (1984). Psychotherapy in a New Key: A Guide to Time-Limited Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Strupp, H. H., and Hadley, S. W. (1979). Specific versus non specific factors in psychotherapy: a controlled study of outcome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 36, 1125–1136.

Suh, C. S., Strupp, H. H., and O’Malley, S. S. (1986). “The Vanderbilt process measures: the psychotherapy process scale (VPPS) and the negative indicators scale (VNIS),” in The Psychotherapeutic Process: A Research Handbook, eds L. S. Greenberg and W. M. Pinsof (New York: Guilford Press), 285–323.

Svensson, B., and Hansson, L. (1999). Rehabilitation of schizophrenic and other long-term mentally ill patients: results from a prospective study of a comprehensive inpatient treatment program based on cognitive therapy. Eur. Psychiatry 14, 325–332.

Tracey, T. J. (1989). Client and therapist session satisfaction over the course of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chic.) 26, 177–182.

Tracey, T. J., and Kokotovic, A. M. (1989). Factor structure of the working alliance inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1, 207–210.

Wolfe, B. E., and Goldfried, M. R. (1988). Research on psychotherapy integration: recommendations and conclusions from an NIMH workshop. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56, 448–451.

Yeomans, F. E., Clarkin, J. F., and Kernberg, O. F. (2002). A Primer for Transference Focused Psychotherapy for the Borderline Patient. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Young, J. E., Klosko, J., and Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford.

Keywords: alliance measures, evaluation of psychotherapeutic process, outcome of psychotherapy, therapist/patient relationship, therapeutic alliance, working alliance

Citation: Ardito RB and Rabellino D (2011) Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Front. Psychology 2:270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270

Received: 29 June 2011;

Accepted: 28 September 2011;

Published online: 18 October 2011.

Edited by:

Susan G. Simpson, University of South Australia, AustraliaReviewed by:

Susan G. Simpson, University of South Australia, AustraliaMichiel V. Vreeswijk, Psychiatric Hospital, Netherlands

Copyright: © 2011 Ardito and Rabellino. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Rita B. Ardito, Department of Psychology, University of Turin, via Po, 14 – 10123 Turin, Italy. e-mail:cml0YS5hcmRpdG9AdW5pdG8uaXQ=