- Department of Psychoanalysis and Clinical Consulting, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

In the 1950s Jacques Lacan developed a set-up with a concave mirror and a plane mirror, based on which he described the nature of human identification. He also formulated ideas on how psychoanalysis, qua clinical practice, responds to identification. In this paper Lacan’s schema of the two mirrors is described in detail and the theoretical line of reasoning he aimed to articulate with aid of this spatial model is discussed. It is argued that Lacan developed his double-mirror device to clarify the relationship between the drive, the ego, the ideal ego, the ego-ideal, the other, and the Other. This model helped Lacan describe the dynamics of identification and explain how psychoanalytic treatment works. He argued that by working with free association, psychoanalysis aims to articulate unconscious desire, and bypass the tendency of the ego for misrecognition. The reasons why Lacan stressed the limits of his double-mirror model and no longer considered it useful from the early 1960s onward are examined. It is argued that his concept of the gaze, which he qualifies as a so-called “object a,” prompted Lacan move away from his double-mirror set-up. In those years Lacan gradually began to study the tension between drive and signifier. The schema of the two mirrors, by contrast, focused on the tension between image and signifier, and missed the point Lacan aimed to address in this new era of his work.

Introduction

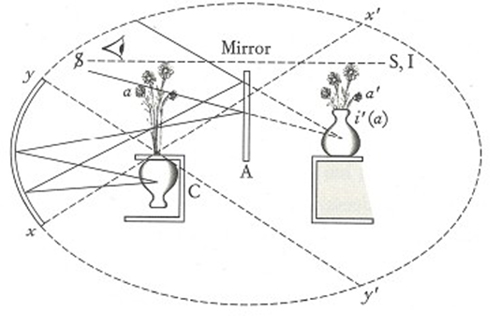

In the 1950s Jacques Lacan developed a device with a concave mirror and a plane mirror (Figure 1) in order to discuss the nature of human identification and formulate ideas on how psychoanalysis, qua clinical practice, responds to identification. In this paper I first examine Lacan’s double-mirror device, also called “the optical model of the ideals of the person” (Lacan, 1966, p. 859), and describe the theoretical line of reasoning he aimed to articulate with aid of this spatial model. Lacan developed this device to clarify the relationship between the ego, the drive, the other, and the Other, with the aim of understanding the role of ideals and identification therein. Next, I discuss the reasons why, from the early 1960s on, Lacan (1964, 2004b, 2006e) stressed the limits of his double-mirror model and no longer considered it useful. Indeed, as he introduced his concept of the “object a,” and discussed the role played by the gaze in relation to subjectivity, Lacan no longer believed that the schema of the two mirrors grasped what is really at stake in psychoanalysis. For this reason he switched to different models of subjectivity in which the tension between image and signifier no longer stands to the fore, but the relationship between signifier and drive/jouissance is emphasized.

Figure 1. Lacan’s double-mirror device (Lacan, 2006e). Reprinted from ECRITS by Jacques Lacan, translated by Bruce Fink. English translation copyright © 2006, 2002 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

On the Antecedent of the Double-Mirror Set-Up: The Mirror Stage

Lacan discussed and constructed his double-mirror apparatus (Figure 1) during his first seminar (Lacan, 1988a). Over numerous sessions he argued that, mediated by language, identification consists of adopting images that serve the purpose of drive-regulation. However, the idea that identification follows a mirror-like logic can be found in his earlier work. For example, in his doctoral thesis where paranoia is discussed and psychoanalysis is only mentioned as one theoretical framework next to many others, Lacan (1932) made use of mirror imagery to characterize identification (Vanheule, 2011). In this thesis Lacan discussed the case of a paranoid patient, Aimée, suggesting that she is overwhelmed and captivated by her close relationships with certain others. For example, in terms of her relationship with a colleague, Lacan states that her actions “contrast with those of our subject ‘like an object to its mirror image”’ (Lacan, 1932, p. 226).

The first systematic theory of the role images and mirror processes play in identification can be found in “The Mirror Stage as formative of the function of the I as revealed in psychoanalytic experience” (Lacan, 2006b). This text is the revised version of a paper Lacan presented in 1936 at the 14th IPA conference. At that time, Lacan’s text was not included in the conference proceedings, possibly because he was annoyed by Ernest Jones’s interruption of his speech due of time constraints (Roudinesco, 1994). The text was published 13 years later, and later slightly revised for a lecture at the British Psycho-Analytical Society (Lacan, 1953).

A crucial thesis in the 1949 version of the paper is that the cognitive capacity of recognizing one’s own image in a mirror, which develops between the age of 6 and 18 months, produces an experience of satisfaction and makes up the basis of a broader tendency to approach the world in terms of (self-) recognition1. The developmental period during which this self-recognition first takes place is called “the mirror stage.” In Lacan’s line of reasoning the “I” is then “precipitated in a primordial form” (Lacan, 2006b, p. 76), meaning that by qualifying an external image as a reflection of oneself, and by identifying with it, the ego is constituted. In this line of reasoning the ego is above all based on a specular image; on the perception of the body as a Gestalt in an external reflective surface. In fact, what is typical of the mirror stage is that the child shifts from a fragmented experience of the body to the perception of the body as a unity. Lacan (2006b) believed that this experience of the body as a unity makes up the basis of any self-experience, and stressed that it installs an generalized search for unity in the world, which actually distorts the experience of reality. Indeed, in his discussion of the mirror stage Lacan does not simply synthesize research of his contemporaries in developmental psychology, like Köhler and Baldwin, but stresses that any identification with a self-image serves a defensive aim: by focusing on the image of who one is and what one is capable of, an individual actually denies his own incapacity and internal chaos, and thus installs a tendency toward misrecognition. An example Lacan uses to illustrate this idea is that of the infant who cannot yet walk or stand without a prop, but becomes excited by the brief moments it can abandon the prop. The child sees itself as standing upright, as having overcome its own inability, while in reality it is not yet mastering its own movement. By anticipating what he will later master and seeing himself as if he were already mastering the developmental task he is confronted with, the child misrecognizes his actual inability. Such anticipation offers a feeling of competency and clearly serves a developmental focus (Lacan, 2006a), but also installs a tendency to more broadly misrecognize inconsistency and failure (Lacan, 2006b). Indeed, in Lacan’s (2006b, p. 78) view, the body image the child creates provides “an ‘orthopedic’ form of its totality,” and more broadly produces the experience of constancy together with the repression of inconsistency.

What this first theory on mirror processes states is that the ego, and consistency at the level of self-experience, take shape by recognizing one’s self-image in the outside world, and by identifying with it. This theory is largely inspired by early twentieth-century Gestalt psychology and stresses both the formative and defensive role of images, apart from the influences of language and socio-cultural structures. Contrary to his later writings, Lacan (2006b, p. 76) situates the effect of images in a phase that precedes the impact of language: “the I is precipitated in a primordial form, prior to being objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject.” Hence his frequent reference to ethological research, including studies which prove that female pigeons’ gonads only mature if a congener has been seen (Lacan, 2006b, p. 77) and thus the effect of Gestalts and mental imprinting is studied apart from the impact of culture.

The Building Blocks of the Double-Mirror Device

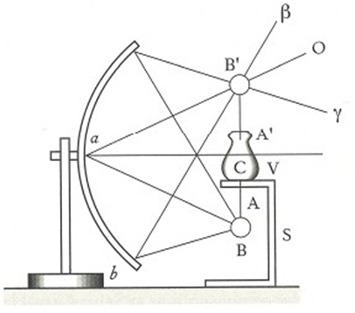

Whereas Lacan’s double-mirror apparatus is primarily used in an allegorical way to illustrate his concept of identification2, it in fact builds on an optical experiment by French physician Bouasse (1947; Figure 2). Bouasse’s model illustrates the function of the concave mirror by pointing out that a hidden flower (AB) can be projected onto an empty vase (C) if an observer (0) looks into the mirror from a certain angle (βB′Γ). What is thus created is the illusion that there is a flower (B′A′) in the vase (C). This projection is symmetrical and reversed. In optics, such a projected image (the flower) is known as a “real image”; real because it can be projected onto a screen.

Figure 2. Mirror set-up in Bouasse’s experiment. Reprinted from ECRITS by Jacques Lacan, translated by Bruce Fink. English translation copyright © 2006, 2002 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

The schema of the two mirrors is a model derived from Bouasse’s experiment. In developing his own spatial arrangement, Lacan adds a number of things to Bouasse’s arrangement: he swaps the vase and the flowers around (left of Figure 1); he adds a plane mirror (A) to the middle, and onto this the image created in the concave mirror is projected (in optics this image on the plane mirror is a virtual image, reproduced on the right side of the arrangement); he introduces an observing ego (the eye as observer) at the level of the divided subject ( ). The eye can see the image of the vase with flowers in the plane mirror, provided it looks from the angle it is actually at in Figure 1. As can been derived from Figures 3 and 4, Lacan’s description of the mirror set-up is optically correct, in that by watching the plane mirror from the angle of the observing eye, the virtual image of a vase projected around flowers can indeed be seen.

). The eye can see the image of the vase with flowers in the plane mirror, provided it looks from the angle it is actually at in Figure 1. As can been derived from Figures 3 and 4, Lacan’s description of the mirror set-up is optically correct, in that by watching the plane mirror from the angle of the observing eye, the virtual image of a vase projected around flowers can indeed be seen.

What Lacan Aimed to Express with the Double-Mirror Device

In Lacan’s reasoning, each element of the arrangement represents a psychoanalytic concept. The arrangement itself consists of two symmetrical components, with each side of the plane mirror depicting a different aspect. The plane mirror (A) symbolizes the Other (“Autre” in French). Crucial to the arrangement is the distinction between the symbolic Other and the imaginary other. The imaginary other is the image or picture of the other-equal in which the ego recognizes itself. The symbolic Other, by contrast, refers to language and discourse. Lacan’s (2006e) point, which is novel compared to his ideas concerning the mirror stage, is that the Other structures and determines any relation humans can have to reality and others qua interpersonal figure: “It would be a mistake to think that the Other (with a capital O) of discourse can be absent from any distance that the subject achieves in his relationship with the other, (with a lower case o) of the imaginary dyad” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 568). Indeed, by presenting the Other as the plane mirror in which the observing ego can see an image of itself, Lacan, from the mid-1950s on, stresses the centrality of language for the self-image humans can acquire. Thus considered language use, and not the visual perception of Gestalts, mediates the acquisition of images. This implies that in Lacan’s double-mirror set-up, “image” refers to the representations and meanings people construct by using words, rather than impressions the visual system processes; language3 determines the mental representations people discern and the relations they have with others. Lacan (2006e, p. 568) emphasizes that this mediation via the Other of discourse is already present in the mirror stage as a moment in development4. Indeed, reconsidered from Lacan’s work in the mid-1950 and 1960s, it could be argued that in the mirror stage the Other is present in the figure of the adult who is seen by the child as a witness the moment the small child recognizes himself. The child will typically make an appeal to the adult, who is asked to verify the mirror image and approve it.

The left side of the arrangement situates the concepts that represent the divided and non-integrated being of the subject: the flowers (a) refer here to the partial drives. In Lacan’s (1988a) view drives, like the oral and the anal drive, are partial in that they do not make up one tendency in people’s functioning and there is no completely satisfying object connected to them. Rather, they confront the individual with “turbulent movements” in his own organism and give rise to a fragmented experience of the body (Lacan, 1988b, 2006b, p. 76).

A set-up in which only the flowers are visible would represent the phase prior to the mirror stage, when the libidinous function has not yet been normalized or structured. Lacan links the Freudian concept of auto-eroticism to this prior stage where the ego has not yet been formed (see Lacan, 2004b, p. 57, 140). The drive gratification in this stage gives rise to an “autistic jouissance5” (Lacan, 2004b, p. 57), which is to say gratification without the image, without a detour via the Other. As regards the status of the flowers, Lacan employs a dichotomy both in his text on the mirror stage and in his construction of the double mirror (e.g., Lacan, 2006e, p. 675). On the one hand, on the side of the child he emphasizes “the turbulent movements with which the subject feels he is animated” (Lacan, 2006b, p. 95), which we interpret as real tension, a component of the drive by which the primitive subject is characterized. On the other hand, he emphasizes the lack of motor coordination in the young child that ties in with the structurally premature birth, which, according to a somewhat evolutionarily reasoning, Lacan says is peculiar to man6. Both aspects lead to a fragmented body image and to a reaction of helplessness, or what Freud called “Hilflosigkeit” (see Lacan, 2004b, p. 75, 162).

Back to the left side of Lacan’s schema, in which the divided subject ( ) symbolizes the speaking being whose identity is connoted, but never denoted exactly by language. Indeed, the subject’s place is to be found “in the elision of a signifier” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 567) and in the experience of the “want-to-be” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 549), or desire, that language use produces. The hidden vase, in its turn, represents the body qua volume or container, in which the partial drives, as flowers, will be situated. The real image i(a) of the vase projected in the concave mirror represents the image of the “reality of the body” (Lacan, 1966, p. 860). It is an image that is mentally created, but that is “inaccessible to the subject’s perception” (Lacan, 1966, p. 860). The concave mirror represents the cerebral cortex Lacan (1988a, 2006e), which Lacan (2006b, p. 78) assumed functions as “an intra-organic mirror.”

) symbolizes the speaking being whose identity is connoted, but never denoted exactly by language. Indeed, the subject’s place is to be found “in the elision of a signifier” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 567) and in the experience of the “want-to-be” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 549), or desire, that language use produces. The hidden vase, in its turn, represents the body qua volume or container, in which the partial drives, as flowers, will be situated. The real image i(a) of the vase projected in the concave mirror represents the image of the “reality of the body” (Lacan, 1966, p. 860). It is an image that is mentally created, but that is “inaccessible to the subject’s perception” (Lacan, 1966, p. 860). The concave mirror represents the cerebral cortex Lacan (1988a, 2006e), which Lacan (2006b, p. 78) assumed functions as “an intra-organic mirror.”

The right side of the arrangement designates a field of ideality as observed by the ego (eye) via the Other (A). It is the field where the ego-ideal (I) and the ideal ego (symbolized by i′(a), which points to the vase with flowers) are situated, and where the subject seems to have overcome its own deficiency and division (symbolized by S at the right upper side: the virtual subject that is no longer divided). In short, the arrangement illustrates both the integration of partial drives via and in the body image and the attempt of the speaking subject to overcome his own “want-to-be,” meaning its lack of experienced inner consistency, by trying to resemble an idealized version of itself. The arrangement illustrates that this imaginary process is activated parallel to the articulation of the subject ( ) via the symbolic system of language. Lacan (1988b, p. 54) describes this as follows: “the subject is no one. It is decomposed, in pieces. And it is jammed, sucked in by the image, the deceiving, and realized image, of the other, or equally by its own specular image.”

) via the symbolic system of language. Lacan (1988b, p. 54) describes this as follows: “the subject is no one. It is decomposed, in pieces. And it is jammed, sucked in by the image, the deceiving, and realized image, of the other, or equally by its own specular image.”

This line of reasoning partially retains Lacan’s idea from the mirror stage: an ego takes shape via recognition of and identification with an external image that acts as ideal for the ego, and reflects a unified picture. This experience allows one to also see oneself as an entity or image in an anticipatory movement, which creates an idea of what the ego could be, virtually and ideally. In this process the ego implicitly assumes that it could become a consistent entity by being aligned with the ideal ego. Lacan (1988a,b) indicates that this identification is accompanied by a jubilant mood given that mastery has been achieved, but also that we are dealing here with a misrecognition: the division of the subject and the conflicting representations it is made up by are covered by the imaginary identification.

By stating that this process is essentially mediated via the Other qua discourse, however, Lacan adds a new element to the reasoning from the mirror stage. By means of the double mirror, Lacan demonstrates that identification includes more than aligning the ego to an image that is adopted via other-equals. It is a process that is mediated symbolically: symbolic elements determine the acceptance of an image. Lacan calls the privileged symbolic elements that perform an orienting function ego-ideals (I): “The ego-ideal governs the interplay of relations on which all relations with others depend. And on this relation to others depends the more or less satisfying character of the imaginary structuration” (Lacan, 1988a, p. 141). In the terminology of the arrangement, these ideals “orient” the plane mirror, which means to say that the ego-ideals place and hold the mirror of language in its vertical position, such that an ideal image of oneself (i′a) can be seen: the ego-ideals make it possible for an ideal ego to be perceived. The ego-ideal is thus linked to the ideal ego in an important way. Lacan (1964, p. 268) states that the ego-ideal represents the point where the subject sees himself as he is seen by others, and from where the Other sees the subject as the subject wants to be seen. Indeed, in his further discussion of the ego-ideals Lacan indicates that these actually fulfill a dual purpose. On the one hand, they serve to reap recognition by the Other to thus create a place in the desire of the Other. Lacan characterizes the ego-ideal as a “privileged signifier” by which the subject “will feel himself both satisfactory and loved” (Lacan, 1964, p. 257). By means of the ego-ideal the subject wants to ensure himself of appreciation by the Other. On the other hand, ego-ideals act as props with which the subject can satisfy his own lack. In the arrangement, this is expressed by the symmetrical position between  and I, and by the fact that the virtual subject (S) is no longer divided. Ego-ideals are “based on the ego’s unconscious coordinates” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 567), meaning on the signifiers that were used to articulate the identity of the subject. Ego-ideals also aim to compensate for the missing signifier the subject is essentially marked by.

and I, and by the fact that the virtual subject (S) is no longer divided. Ego-ideals are “based on the ego’s unconscious coordinates” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 567), meaning on the signifiers that were used to articulate the identity of the subject. Ego-ideals also aim to compensate for the missing signifier the subject is essentially marked by.

Psychoanalytic Treatment in Relation to the Double-Mirror Device

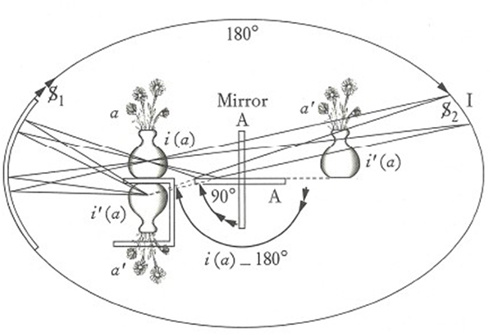

What is important about Lacan’s double-mirror model, and his earlier theory on the mirror stage, is that he aimed to formulate guidelines for psychoanalytic treatment. The underlying idea was that treatment should not focus on reinforcing the ego, but that the ego’s tendency toward misrecognition should be taken into account; the analyst should concentrate on the divided subject as it comes to the fore via free association. The rotated double-mirror set-up (Figure 5) expresses this schematically. Here, the plane mirror A now gives the position of the analyst. In psychoanalytic treatment, the analyst does not lend himself as an other-equal, as an empathetic mirror or as an ideal ego within the field of the imaginary, which is expressed, inter alia, in the a-scopic positioning of the analyst behind the sofa. Nor does the analyst position himself as a knowing Other who tells the subject how he must behave in relation to the desire of the Other; he does not incarnate the knowledge that is ascribed to him by means of the transference. At both points, the analysis creates an absence. This is expressed in the rotation of the plane mirror by 90°, making A horizontal. Note that this position expresses the fact that the analyst is still the one operating through discourse A, but what is left to one side is its identificational function. This places the discourse of the unconscious in a central position. Via a so-called “translation movement” (the 180° movement between  1 and

1 and  2) the subject – understood as the effect of free association – now appears in the place of I. In place of the hypostasized contrast

2) the subject – understood as the effect of free association – now appears in the place of I. In place of the hypostasized contrast  and I from the classic double mirror we get a dialectic between

and I from the classic double mirror we get a dialectic between  1 and

1 and  2. Lacan points out that taking this path between

2. Lacan points out that taking this path between  1 and

1 and  2 can result in experiences of depersonalization. This is because the mirrors do not reflect a unitary image on the moving subject. According to Lacan, this depersonalization must be understood as a sign that a step forward has been taken. They are “signs… of a breakthrough” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 569).

2 can result in experiences of depersonalization. This is because the mirrors do not reflect a unitary image on the moving subject. According to Lacan, this depersonalization must be understood as a sign that a step forward has been taken. They are “signs… of a breakthrough” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 569).

Figure 5. Rotated mirror set-up. Reprinted from ECRITS by Jacques Lacan, translated by Bruce Fink. English translation copyright © 2006, 2002 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Once the position of  2 has been reached, the effect on the imaginary will be double. If the subject looks toward the concave mirror from

2 has been reached, the effect on the imaginary will be double. If the subject looks toward the concave mirror from  2, on the one hand he will see how the virtual image of the flowers in the vase that was seen from position

2, on the one hand he will see how the virtual image of the flowers in the vase that was seen from position  1 comes into being. The subject that looks from

1 comes into being. The subject that looks from  2 is looking from the position adopted by the observer in Bouasse’s experiment, and sees through the illusory nature of the perceived vase. In other words: through the translation movement, the illusory nature of the ego becomes clear, as well as the misleading stability that the ideal ego gave to it. On the other hand, the subject

2 is looking from the position adopted by the observer in Bouasse’s experiment, and sees through the illusory nature of the perceived vase. In other words: through the translation movement, the illusory nature of the ego becomes clear, as well as the misleading stability that the ideal ego gave to it. On the other hand, the subject  2, if he looks into the horizontally rotated plane mirror, will still be able to see a virtual image of the flowers in the vase. This time, however, the virtual image is perceived in all its virtuality, just like the reflection in the water of a tree growing by the water’s edge is immediately perceived as a reflection.

2, if he looks into the horizontally rotated plane mirror, will still be able to see a virtual image of the flowers in the vase. This time, however, the virtual image is perceived in all its virtuality, just like the reflection in the water of a tree growing by the water’s edge is immediately perceived as a reflection.

Thus considered the aim of psychoanalytic practice principally consists of bringing about free association on the issues an individual is troubled by, such that via the conflicting lines of speech that come to the fore he obtains a different understanding of his problems and desires, and new choices can be made: “analysis is based on what the subject gains from assuming (assumer) his unconscious discourse as his own” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 569). In guiding this process the psychoanalyst plays a crucial role. The analyst refrains from focusing on the ego, and positions him/herself as the one who safeguards the unconscious (Lacan, 2006d). Indeed, the principal role of the psychoanalyst consists of validating signifiers and ideas in the analysant’s speech that are unexpected, or troublesome from the perspective of the analysant’s ego. Along this way aspects of desire that were first denied, can be recognized and accepted as belonging to oneself. The setting the psychoanalyst creates means to provide a safe space and a time-frame for articulating such discourse, and for assuming one’s own desire.

Lacan’s Deconstruction of the Double-Mirror Set-Up

However, as time progressed Lacan gradually distanced himself from his double-mirror set-up by highlighting its flaws. This begins in his commentary on Daniel Lagache (Lacan, 2006e), in which he points out that the set-up dates from a time when he focused too much on the mere contrast between the imaginary and the symbolic (Vanheule, 2011): “my model dates back to a preliminary stage of my teaching at which I needed to clear away the imaginary which was overvalued in analytic technique. We are no longer at that stage” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 571). Indeed the early 1960s Lacan’s theoretical framework for studying questions on psychoanalysis changes. Whereas in earlier writings he focused on desire as articulated inside speech, and contrasted unconscious aspects of desire with the ego’s tendency to misrecognize internal division, attention was henceforth directed to the question of what it is that engenders desire, and to the question of why the mirror image plays such an important role in people’s mental functioning.

To frame these questions, it is worth first looking at the short story Lacan tells at the beginning of Seminar X (1962–1963, p. 14), a similar tale to which he referred in the previous year in Seminar IX (unpublished, lesson 4/4/1962). Imagine, he says, that I am in a room with a giant female praying mantis 3 m tall; and that I myself am wearing the mask of an animal. The mask is one like that of the magician from the Paleolithic cave of the “Trois Frères,” which looks like a horned being, half-man, half-animal, and I do not know exactly what animal I am. It is not hard to imagine, he continues, that I would not feel entirely at ease in such a situation, because there is a chance of the female mantis misconstruing my identity. With a certain amount of imagination it is in fact possible to notice a similarity between the mask of the magician from the engraving and the pointed head and antennae of a praying mantis7.

The crucial question that Lacan raises with this Jan Fabre-esque fable is that of the relationship between the desire of the Other and the identity of the subject. The uncertainty regarding the behavior of the female mantis touched on by Lacan – imagine she sees him as prey, or as an enemy… or worse still: as a male mantis, whose head is always eaten during copulation – reflects the structural uncertainty he, as subject, endures in relation to the enigmatic intentions of the other being with which he finds himself confronted. Here, the female praying mantis has “a voracious desire, to which no common factor links me”; it is an Other who is “radically Other” (Lacan, 2004b, p. 376). In an allusion to Jacques Cazotte’s novel The Devil in Love, Lacan says that the female mantis is radically Other because the question: “Che-vuoi?,” meaning “What do you want?,” cannot be answered (Lacan, 2004b, p. 14). The fact that he does not know precisely who or what he is has a disquieting effect here. That Lacan does not know who or what he is in relation to the voracious female praying mantis, is given by the situation; after all, he is wearing a mask and does not know what this mask looks like. The compound eyes of his adversary, which, in contrast to the eyes of vertebrates do not allow him to glimpse at his reflection, perpetuate the uncertainty.

The fable illustrates nicely that the enigma of the desire of the Other is alarming, and that uncertainty about one’s own identity increases this disquiet. We can infer from this that in Lacan’s view the construction of a self-image has a function as an anxiety inhibitor. This is because by using such an image, a person tries to see which position he/she has in the desire of the Other, with the aim of positioning himself in relation to this. This story tells us something about the asymmetrical contact between a giant mantis and a masked man who does not know what mask he is wearing, but also allows us to learn something about the symmetry with which the neurotic approaches others: the neurotic tends to misrecognize the Otherness of the Other, focusing on his capacity as other-equal. Within this logic, anxiety arises to the extent that the other cannot be positioned on the basis of one’s own image and the activity of reflection is no longer sufficient to localize the other.

Lacan’s main problem with the schema of the two mirrors is that it cannot accurately express the factor that engenders both desire and anxiety in a subject. What it fails to grasp is what he called, from the late 1950s onward, the “object a” (Lacan, 1964, 2004b, 2006e): “my models fails to shed light on object a. In depicting a play of images, it cannot describe the function this object receives from the symbolic” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 571). In Seminar X Lacan deconstructs his arrangement. Step by step, he de-composes the specular level and also takes steps in the construction of a separate position for the object a; a position as residual object that remains elusive for the signifier and for the image (Miller, 2004). By introducing this object a it also becomes clear that his previous ideas on mirroring processes failed to appreciate the structurally alien nature of the object a.

Indeed, in Seminar X Lacan (2004b) actually effects a transition, whereby the schema of the two mirrors is no longer seen as adequate. The main reason for this is that the processes that govern desire are then reconceptualized. Whereas before Seminar X Lacan (2006e) criticized his double-mirror set-up as it failed to indicate what desire is directed toward, he henceforth takes a distance from it because it radically neglects what desire is about. What is crucial about Seminar X is that the object a is no longer the object of desire (“objet du désir”), but the object that is the cause of desire (“objet cause du désir”; Miller, 2004). Before Seminar X Lacan described the object a as the mysterious dimension to which desire is directed. An iconic example he used to explain the element that desire anticipates is Plato’s Symposium, and more particularly Alcibiades’s fascination for Socrates: despite the man’s ugliness, Alcibiades is fascinated by and attracted to Socrates (Lacan, 2001). A mystifying dimension in Socrates, something that Alcibiades cannot explain and can only tentatively call “the agalma,” makes Socrates attractive. In terms of the processes that govern desire, the agalma is then described as the object a toward which desire is directed. In Seminar X, by contrast, the object a is the dimension that sets desire in motion. Henceforth, the object a denotes the element in mental life that fuels desire.

The neurotic focus on objects of desire, and the belief that a dimension of the drive, as indicated by the flowers in the double-mirror model, could be expressed in signifiers is thereby qualified as illusionary. The imaginary illusion that governs neurosis – and which is confirmed in the classic double-mirror set-up – is that the vase projected at the level of the mirror image i′(a) is capable of containing the flowers as a’ in the virtual space: “He imagines that this vase may contain the object of his desire” (Lacan, 2004a, p. 236). What Lacan demonstrates in Seminar X is that the object a is resistant to this assumption, that it should not be introduced into the game of sexual seduction; conversely it appears on an imaginary level as an absence.

Lacan emphasizes that there is a difference between the objects a, which are now represented in the arrangement by the real bouquet of flowers (Lacan, 2004b, p. 139) or simply as a, and the elements that logically correspond to them. What now appears in the virtual space as a corresponding element is not a projection of a. What appears instead is an element asymmetrical to this, first denoted as −Φ, and later simply as X, both pointing to a lack; to an element that cannot be imagined. This asymmetrical reciprocal positioning of both elements also results in Lacan distancing himself from the essentially symmetrical reflection in the mirror. The asymmetry is no longer understood in a mirror logic. Hence he makes the transition to the topological figures such as the cross-cap, which actually allow the relationship between two asymmetrical elements to be considered.

What Lacan appears to be illustrating with this asymmetry is a reasoning on the status of the body for a subject (Miller, 2004). The classic view of the mirror stage taught us that the subject primarily acquires a bodily representation through mirror processes, which is also directly understood as a characteristic of the ego. At this level, we are dealing with the body as tangible Gestalt, as form. The double-mirror set-up altered this view, suggesting that above all the body is a signified entity to which humans only have access thanks to language. This is opposed by the body as organism, as lifelike substance. The new position from Seminar X is that the organic aspect of the body is not entirely enveloped by the mirror image: aspects of corporeality cannot be grasped and mastered by means of the symbolic or by means of the imaginary. This residual component that is not mirrored, and lies radically outside the field of the Other, is henceforth called the object a: “the a is what remains irreducible in this total operation of the advent of the subject to the locus of the Other, and it is from there that it is going to take on its function” (Lacan, 2004b, p. 189).

According to Miller (2004), the residue that thus remains must be understood as a remainder of Triebregung. What is of particular interest here is that Lacan (2004a, p. 22) understands this Freudian Regung as an unruly force: “Regung is stimulation, the call to disorder, even to a riot.” The object a thus appears as a resistant corporeal element that re-vitalizes the deathliness of everything that is characterized by the orderliness of the signifier. The object a is an element that does not follow the phallic logic of the signifier (hence the characterization as negativized phallus −Φ).

The lack of reflectability of the object a, represented by −Φ and X as its asymmetrical opposites, is combined with a typical form of fear, which Lacan (2004b, p. 58) labels castration fear. Thus considered, castration fear is the consequence of an event in which the empowering mirror image that radiates omnipotence is violated, thereby suggesting that there are aspects of the drive that elude imaginary projection. An example in which Lacan recognizes the subject’s powerlessness in relation to corporeality is the shrinking of the male sex organ after orgasm (detumescence). This loss of erection is a structural fact that shows how the body remains resistant to the possible further sexual intentions of the subject, which triggers fear.

One Step Beyond the Double-Mirror Set-Up

In Seminar XI Lacan further elaborated his ideas on the object a. On the one hand he characterizes this object in abstract terms as a remainder of jouissance that cannot be signified, and as “an accomplice of the drive” that fuels desire (Lacan, 1964, p. 69). On the other hand Seminar XI is also of key significance, in that he also attempts to define the object a in operational terms, saying that in the dimension of “the gaze” the object a is manifested. Whereas in Seminar X Lacan is somewhat vague about the exact phenomena in which the object a is manifested, and, for example, still defines the phallic register as one of the domains in which the object a takes shape, hence his example of detumescence, in Seminar XI he discerns four objects a: the gaze, the voice, taking in nothing, and giving nothing. In these phenomena, which he situates in the scopic, invocative, oral, and anal drive registers respectively, Lacan recognizes how the drive qua non-signified dimension takes shape (Lacan, 1964; Vanheule, 2011). In the context of this paper we solely focus on the gaze, which expresses how the scopic drive takes shape in relation to signifier-based subjectivity.

A characteristic in which Lacan (1964, p. 84) situates or detects the gaze is the neurotic’s tendency to behave as if he/she is looked at by others: “The gaze I encounter … is not a seen gaze, but a gaze imagined by me in the field of the Other.” The gaze determines neurotic desire to the extent that an individual looks at him/herself from a virtual point that is situated outside8. Questions like “what would people think of me?” and “what if someone could see this,” or just the idea of another person looking at oneself, make up a continuous monitoring force that guides the neurotic in daily life. It is a factor which brings the neurotic to ask questions about who he actually is, how he is perceived, and how he should be perceived by others. Indeed, the gaze is the reflective dimension from which an individual is driven to create images of his own identity in relation to others, and from which ego-ideals are adopted. Thus considered the gaze has nothing to do with the eyes qua visual organs, but concerns the figurative lens that engenders the “Che-vuoi”-question Lacan situates at the basis of the neurotic’s relation to the Other. What is important in this line of reasoning is that the gaze can be considered as constituent of the self-image and of the ideals a person lives up to. The gaze qua perspective-taking activity “causes” or determines the selection of signifiers at the level of O. This implies that the mirror of the symbolic, where the image is constructed, is not a neutral communicative code where components for articulating the subject can be selected, but a set of selectively perceived elements. Moreover, the object a is not simply a side product of linguistic articulation, an idea endorsed in Seminar X (Lacan, 2004b), but the basic urge for signifying articulation itself.

Interestingly Lacan also emphasizes that in contrast to ideals, the object a is typically marked by lack and discord: “the object a is most evanescent in its function of symbolizing the central lack of desire, which I have always indicated in a univocal way by the algorithm (−Φ)” (Lacan, 1964, p. 105). Concerning the gaze this implies that it is not a virtual point from which harmony in relation to the other can be articulated. Rather, it functions as the point from which disparity comes to the fore: “When, in love, I solicit a look, what is profoundly unsatisfying and always missing is that – You never look at me from the place from which I see you” (Lacan, 1964, p. 103). The image the subject can actually convey, and the perspective from which the other reacts, never correspond to the gaze the subject relates to at the level of fantasy. Indeed, in this seminar Lacan characterizes the gaze as “a strange contingency” (Lacan, 1964, p. 72) that is indicative of the impossibility to completely articulate an individual’s being in terms of the Other’s signifiers, and therefore bears witness of castration. It represents a deadlock in the tension between drive and signifier.

In terms of drive-related processes, Lacan (1964, p. 195) more broadly indicates that the gaze is central to scopic drive gratification, and that its main activity consists of “making oneself seen” (“se faire voire” in French). On a continuum between hiding away and exhibiting oneself in relation to actual or virtual onlookers the gaze takes shape. On the one hand the gaze determines signifying articulation, but on the other hand also produces a drive gratification that cannot be understood in terms of signifiers alone. It is precisely this last dimension that cannot be grasped in terms of the double mirror, which is why Lacan leaves this schema behind.

Parallel to the discontent he expressed toward his own schema of the two mirrors, from the mid-1960s Lacan also began to reformulate his ideas on the goal and finality of psychoanalytic practice. He proposed that psychoanalytic treatment should not merely focus on reading unconscious desire, such that the analysant can assume the desire his speech bears witness of. The more crucial question is what it is that makes up a person’s desirous position. But rather than focusing on desire as such, the question shifts to the analysant’s relation to the desire of the Other and the object a. Indeed, from Seminar XI onward Lacan aims to define psychoanalytic treatment as a process in which the relation between a subject and its objects a needs to be reworked: “the object a … is presented precisely, in the field of the mirage of the narcissistic function of desire, as the object that cannot be swallowed, as it were, which remains stuck in the gullet of the signifier. It is at this point of lack that the subject has to recognize himself” (Lacan, 1964, p. 270). Recognizing oneself in one’s relation to objects a, and changing aspects of this relation, is a challenge for psychoanalytic treatment he henceforth places next to deciphering the unconscious and articulating desire.

The main clinical concepts Lacan uses to address this challenge are “fantasy” and “traversing the fantasy.” While this concept can already be found in the work of Freud and Klein, Lacan’s interpretation of “fantasy” is specific (Fink, 1996; Žižek, 1998; Miller, 2002). In his view, fantasy is the neurotic’s answer to the riddle of the Other’s desire, and a way of constituting a place for the subject in relation to the object a. Traversing the fantasy, in its turn, means that through ongoing free association, the positions the analysant has been occupying in relation to the object a are mapped with the aim of enabling different positions toward the Other’s desire and toward the object a. The fantasy is traversed with the aim of breaking the repetitive cycle of incarnating the same position in relation to the Other and to the object a. It was precisely in conceptualizing the idea of traversing the fantasy that Lacan moved away from his schema of the two mirrors in favor of topological figures.

Conclusion

In this paper I discussed Lacan’s double-mirror set-up. Situating its basis in his preceding theory on the mirror stage, and in an optical experiment by Henri Bouasse, I argued that in the 1950s Lacan developed this device with the aim of formulating a theory on identification and of articulating principles on how the ego’s tendency for misrecognition should be addressed in psychoanalytic practice. However, from the early 1960s onward, as his inquiries shift toward understanding what fuels desire rather than describing how desire is articulated in signifiers, Lacan left this scheme behind. Arguing that a crucial aspect of drive-related functioning cannot be understood in terms of signifiers, but should be studied in terms of a dialectical tension between drive and signifier, he then focused on so-called objects a, of which the gaze is one example. To graphically represent his line of reasoning on the relationship between subject and object a, Lacan shifts to topological models, like the interior eight and the Möbius strip (Lacan, 1964, unpublished). He is particularly interested in such geometrical figures because of the ambiguous and non-symmetrical relations between inside and outside, or underside and top they imply.

Focusing on the status of the double mirror in Lacan’s work, many other questions remain unaddressed in the present paper. Similarities and differences between Lacan’s use of mirror terminology and other psychoanalysts’ use of such concepts, and the relevance of the double mirror for exploring clinical problems have not been addressed here (for examples see Vanheule and Verhaeghe, 2005, 2009). Also, the relevance of Lacan’s model for developmental psychology (Verhaeghe, 2004), issues on the phenomenology of perception (Kusnierek, 2008), or neuropsychological problems (Morin et al., 2003), has not been discussed. Most importantly I believe that the relevance and the limits of Lacan’s double-mirror set-up for organizing and understanding the process of psychoanalytic treatment, and the transition it produces, needs to be studied further. Case studies could thereby be of key significance.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Abe Geldhof for the assistance in making the pictures of the double-mirror set-up.

Footnotes

- ^For excellent discussions of Lacan’s text on the mirror stage see Muller (1985, 2000) and Nobus (1998).

- ^Other discussions of Lacan’s schema of the two mirrors can be found in Depelsenaire (1986), Lew (1987), Malengreau (1985) and Pepeli (2003).

- ^This idea is embedded in a broader theory on the centrality of language. In his works from the mid-1950s Lacan (2006c) more broadly stressed the determining and structuring effect of speech on the subjective experience of reality (see Lacan, 2006c).

- ^Nobus (1998) correctly indicates that Lacan gradually began to reconsider the mirror stage as a symbolically determined event. In his text on the mirror stage Lacan (2006b) already referred to the structuring effects of language, discussing, for example, Lévi-Strauss’ work on the effect of symbols (see Dunand, 1996). Nevertheless, he maintained that the ego takes shape before language exerts its power (Lacan, 2006b, p. 76). Later on this idea changed somewhat, as he emphasized that language mediates all imaginary phenomena: “This gradual reconsideration of the mirror stage as a symbolically mediated event, an experience for which the presence of a symbolic Other is also a necessary condition, coincides with the introduction and elaboration of the ‘schema of the two mirrors.”’ (Nobus, 1998, p. 113)

- ^As Lacan (1970, p. 194) indicates, the French term jouissance cannot be easily translated into English, which is why it is usually left in its original form. “Enjoyment” would be its literal translation, but this term is inadequate because of the connotation of pleasure it entails. For Lacan jouissance denotes a mode of satisfaction or drive gratification beyond pleasure. Because it primarily plays at the level of our corporeal experience, Lacan places jouissance in dialectical opposition to language.

- ^“A primordial Discord betrayed by the signs of malaise and motor uncoordination of the neonatal months” (Lacan, 2006b, p. 78); “… a discordance in neurological development.” (Lacan, 2006e, p. 565)

- ^In Seminar IX the story is rather different; there Lacan presents himself as a male mantis of around 1.75 m, and thus assumes an identity that he himself recognizes. Another clear point of difference is that he assumes that he can see himself in the compound eyes of the insect, while in Seminar X he (correctly) states that the surface of a compound eye has no reflective effect.

- ^Lacan suggests that in psychosis the object a has a different position in that it does not function as an external element, but as a dimension that hunts the subject from within (see Vanheule, 2011).

References

Dunand, A. (1996). “Lacan and Lévi-Strauss,” in Reading seminars I and II – Lacan’s Return to Freud, eds R. Feldstein, B. Fnk and M. Jaanus (Albany: State University of New York Press), 98–109.

Fink, B. (1996). “The subject and the other’s desire,” in Reading seminars I and II – Lacan’s Return to Freud, eds R. Feldstein, B. Fnk and M. Jaanus (Albany: State University of New York Press), 76–97.

Lacan, J. (1964). The Seminar 1964, Book XI, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis [1973]. New York: Karnac.

Lacan, J. (1966). “Commentary on the graphs,” in Écrits, eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 858–963.

Lacan, J. (1970). “Of structure as an immixing of an otherness prerequisite to any subject whatever,” in The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man: The Structuralist Controversy, eds R. Macksey and E. Donato (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press), 186–200.

Lacan, J. (1988a). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book I: Freud’s Papers on Technique [1953–1954]. New York: W.W. Norton.

Lacan, J. (1988b). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book II, The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis [1954–1955]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lacan, J. (2004a). “Les complexes familiaux dans la formation de l’individu,” in Écrits [1938], eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 23–84.

Lacan, J. (2006a). “Beyond the ‘reality principle’,” in Écrits [1936], eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 58–74.

Lacan, J. (2006b). “The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I,” in Écrits [1949], eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 75–81.

Lacan, J. (2006c). “The instance of the letter in the unconscious or reason since freud,” in Écrits [1957], eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 412–442.

Lacan, J. (2006d). “The direction of treatment and the principles of its power,” in Écrits [1961], eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 489–542.

Lacan, J. (2006e). “Remarks on Daniel Lagache’s presentation: ‘psychoanalysis and personality structure’,” in Écrits [1961], eds J. Lacan and J. A. Miller (New York: W. W. Norton), 543–574.

Miller, J. A. (2002). Pure psychoanalysis, applied psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Lacanian Ink 20, 4–43.

Miller, J. A. (2004). Introduction to reading Jacques Lacan’s seminar on anxiety. Lacanian Ink 26, 6–67.

Morin, C., Pradat-Diehl, P., Robain, G., Bensalah, Y., and Perrigot, M. (2003). Stroke hemiplegia and specular image: lessons from self-portraits. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 56, 1–41.

Muller, J. (2000). “The origins and self-serving functions of the ego,” in The Subject of Lacan – a Lacanian Reader for Psychologists, eds K. R. Malone and S. Friedlander (Albany: State University of New York Press), 41–62.

Nobus, D. (1998). “Life and death in the glass: a new look at the mirror stage,” in Key Concepts of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, ed. D. Nobus (London:Rebus Press), 101–138.

Pepeli, H. (2003). Psychoanalysis: a treatment, a cure…or much more than that? J. Centre Freudian Anal. Res. 13. [Available at: http://www.jcfar.org/past_papers/Psychoanalysis,%20a%20treatment,%20a%20cure,%20or%20much%20more%20than%20that%20-%20Hara%20Pepeli.pdf].

Vanheule, S., and Verhaeghe, P. (2005). Professional burnout in the mirror: a qualitative study from a Lacanian perspective. Psychoanal. Psychol. 22, 285–305.

Keywords: mirroring, identity, psychodynamic theory, ego-psychology, jouissance

Citation: Vanheule S (2011) Lacan’s construction and deconstruction of the double-mirror device. Front. Psychology 2:209. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00209

Received: 07 June 2011; Paper pending published: 07 July 2011;

Accepted: 14 August 2011; Published online: 13 September 2011.

Edited by:

Pierre-Henri Castel, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, FranceCopyright: © 2011 Vanheule. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Stijn Vanheule, Department of Psychoanalysis and Clinical Consulting, Ghent University, H. Dunantlaan 2, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium. e-mail: stijn.vanheule @ugent.be