- Institute of Cognitive Science, University of Osnabrück, Germany

Working in multidisciplinary teams has become a common feature of modern research processes. This situation inevitably leads to the question of how to decide on who to acknowledge as authors of a multi-authored publication. The question is gaining pertinence, since individual scientists’ publication records are playing an increasingly important role in their professional success. At worst, discussions about authorship allocation might lead to a serious conflict among coworkers that could even endanger the successful completion of a whole research project. Surprisingly, there does not seem to be any discussion on the issue of ethical standards for authorship is the field of Cognitive Science at the moment. In this short review I address the problem by characterizing modern challenges to a fair system for allocating authorship. I also offer a list of best practice principles and recommendations for determining authors in multi-authored publications on the basis of a review of existing standards.

Introduction

Science without publication of it is no science (Horner and Minifie, 2011a). Being a scientist requires publishing original research as an author of scientific publications. Proper authorship then has two vital functions (cf. Strange, 2008):

1. Authorship conveys professional benefit in that it allocates credit for scientific advances.

2. Authorship conveys responsibility in that it implies the endorsement of the quality and integrity of the work performed.

Proper authorship rewards those who contribute to the development of new knowledge and determines who is held accountable for reported research. Because the entire research and publication process relies on truthfulness and trust, authorship that does not honor this connection between credit and accountability jeopardizes the scientific project as a whole (Pimple, 2002; Wager, 2009; Horner and Minifie, 2011c).

If authorship should stay the main currency of science, it is necessary that the scientific community agree upon and establish rules for fair authorship allocation. I will now first identify problems of current authorship practices and then present a systematic compilation of existing standards in the form of best practice principles and recommendations for deciding on authorship.

Limits of Traditional Ways of Allocating Authorship and Current Problems

The concept of authorship developed when there was only one individual responsible for the reported research (Rennie et al., 1997). Traditional authorship practices assume that every author of a publication is involved in and knowledgeable about all aspects of the reported research (Rennie et al., 1997). However, with the evolution of scientific endeavor, this straightforward approach toward determining authorship has become problematic: with an ever-increasing specialization within and between scientific disciplines, collaborations between different institutions, departments, or laboratories have become necessary (Cronin et al., 2003), not to mention the need for consulting technicians or statisticians for expert advice (cf., e.g., Altman et al., 2002). This is why today, a co-author of a multi-authored article is not necessarily knowledgeable about all parts of the research he is involved in and therefore is also no longer able to take responsibility for each facet of the research in question. In this situation, it is difficult to assign appropriate credit and accountability operating with the traditional understanding of “author” (Smith and Williams-Jones, 2011).

The core problem of the traditional system of authorship attribution is its non-transparency. In a multidisciplinary research project, and with several authors listed in the byline, it is no longer sufficient to provide information about what the tasks were of those persons mentioned in the Acknowledgments. To be able to assign appropriate credit and accountability, readers and editors alike must know who among the authors was designing, carrying out, analyzing, and interpreting the reported research (Rennie, 2001). To overcome the limitations of traditional authorship practices, Rennie and colleagues introduced the concept of “contributorship” (Rennie et al., 1997; Frazzetto, 2004):

For [authorship practices] to be able to identify accountability, there must be disclosure to the reader of every participant’s contribution to the work and to the manuscript. (p. 582)

In other words, participants in a research project should be responsible for the contributions that they make, and these contributions should be disclosed (Rennie, 2001).

Fourteen years after it was proposed to replace authorship with contributorship, there is a wide range of different institutions that provide guidelines on ethical authorship, e.g., the American Psychological Association, the Office of Research Integrity, the Society for Neuroscience, The National Academic Press, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, the Council of Science Editors, the Committee on Publication Ethics, or the American Educational Research Association. Additionally, a number of journals and universities issue own guidelines on authorship, e.g., Nature journals’ Authorship Policy, Science’s General Information for Authors, PLoS ONE Guidelines for Authors, or the Publication and Authorship guidelines of the University of Oxford. These guidelines make reference to the idea of contributorship to varying degrees. However, they are not widely known or even ignored (Rennie et al., 2000; Afifi, 2004; Marusic et al., 2004; Grieger, 2005; Dhaliwal et al., 2006; Madiba and Dhai, 2006). Surveys suggest that knowledge of formal authorship criteria is highly variable and the majority of scientists are not familiar with existing criteria at all or do not consider formal criteria necessary (Bhopal et al., 1997). A recent empirical study demonstrated that there are very different attitudes toward granting authorship (Seeman and House, 2010a), and House and Seeman (2010) found that the majority of scientists give credit according to what “seems to be the right thing [to do].”

The ignorance of formal standards for authorship has led to the situation that many authors of scientific publications do not fulfill the requirements for proper authorship today (Goodman, 1994; Hoen et al., 1998; Mowatt et al., 2002; Claxton, 2005b; Pignatelli et al., 2005). At the same time, disputes over authorship issues are a major concern in the day-to-day work of many scientists (Wilcox, 1998; Rennie et al., 2000; Claxton, 2005a). In 2005, Benos and colleagues investigated ethical issues related to the publication process in journals of the American Physiological Society (Benos et al., 2005). They found that between 1996 and 2004 authorship disputes were the fourth most common ethical issue related to the publication process. Equally alarming is the finding that a large part of the scientific community reports that they have experienced not receiving appropriate credit for contributions they had made to published projects (Seeman and House, 2010b). Rennie et al. (1997) pinpointed the overall problem:

“(…) [V]agueness in the byline opens the door to unfair attribution. (…) [and] results in egregious behavior being left unexamined because roles and expectations are undefined and undisclosed. (…) This may explain why disputes about authorship are increasingly common, so wasteful of time, and so poorly resolved.” (p. 580)

This problem may become especially prominent in the field of Cognitive Science. Cognitive Science is dedicated to multidisciplinary research and thereby promotes collaborations between multiple coworkers, that is, multiple potential co-authors. In issue 1 of Cognitive Science (January/February, 2011), for example, there were overall 8 articles with on average 3.1 authors per article with in total 16 different affiliations. However, it is difficult to find guidelines for the allocation of authorship in the field. A database search on PubMed (performed on 10 April, 2011) searching for “Authorship” in titles in Cognitive Science, Frontiers in Cognitive Science, Topics in Cognitive Science and Trends in Cognitive Sciences revealed no single article. Of the major journals of the field mentioned, only Trends in Cognitive Sciences provides an orientation on authorship ethics in stating that a paper should “properly credit the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers” (Cell Press, 2011).

The Best Practices

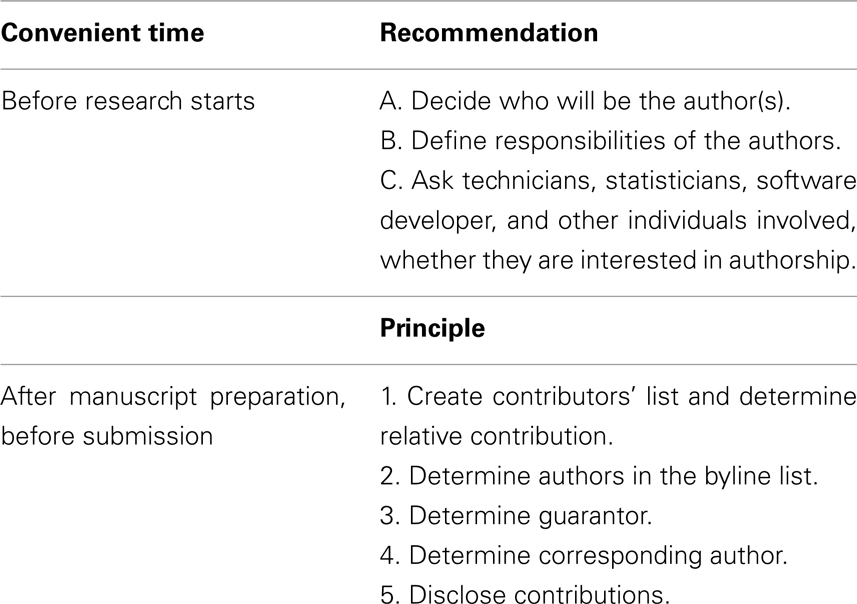

The following principles and recommendations are the result of a systematic review of the literature conducted chiefly within the biomedical literature via PubMed. Table 1 summarizes the best practice principles and recommendations for fairly allocating authorship.

Principle 1

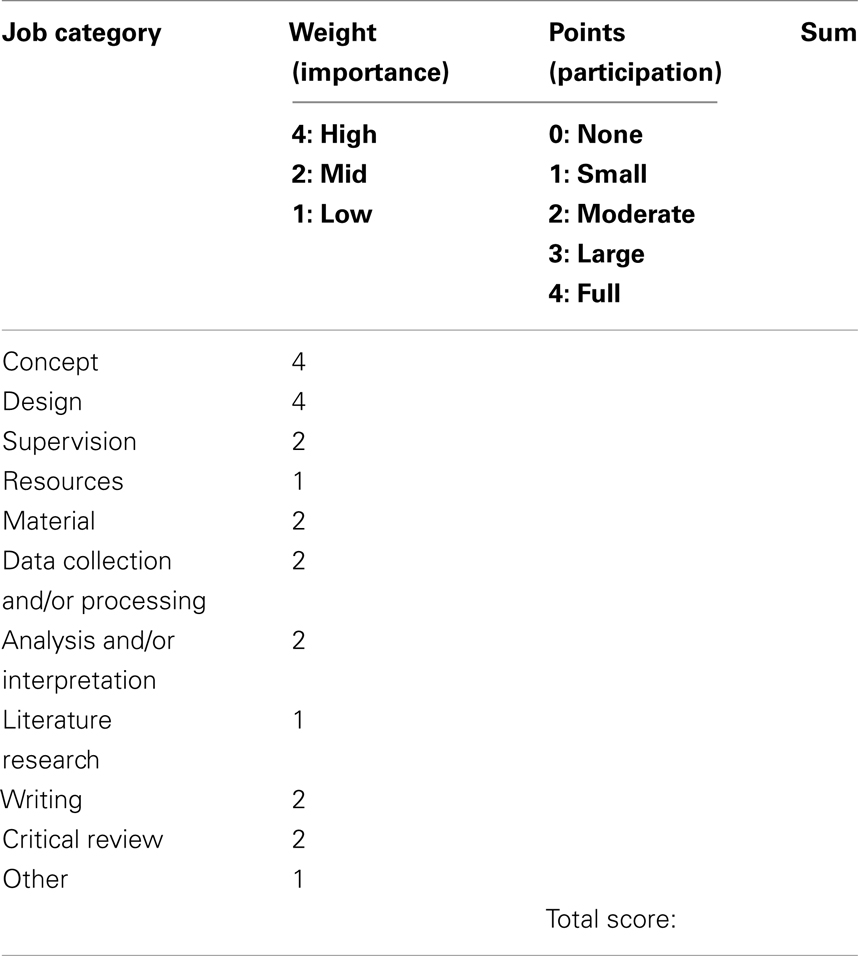

On finishing the manuscript, all individuals are identified who contributed to the research project in a contributors’ list. Subsequently, all contributors meet, discuss, and decide on their respective contribution. For this purpose, researchers use job categories that have previously been agreed upon, e.g., as those defined by the Council of Science Editors (Friedman, 2011; please cf. Table 2) or empirically revealed (cf. Yank and Rennie, 1999). Next, researchers negotiate and determine by consensus each researcher’s relative contribution to the project. This is probably the most difficult task in the whole process of allocating authorship. However, this procedure is the only way to be fair in allocating credit and accountability. Verhagen et al. (2003) suggested in Nature that each contributor should claim his percentage share of the total credit in each of the categories the research team have previously defined, which will then result in a numerical representation of the way in which the work was divided among the researchers involved. Contributors should then be listed in the contributors’ list by descending order of total contributorship across all categories.

Ahmed et al. (1997) suggested a similar method for deciding on relative contributorship by assigning points to each job category in proportion to the extent to which an individual researcher was active in that category. The total sum of points over all categories then determines the order of contributors in the contributors’ list. This method avoids the problem of deciding on the exact proportion of an individual’s contribution. If desirable, researchers could additionally decide to weight the job categories beforehand with a simple scoring system that reflects the relative importance of each category (Parker and Berman, 1998). The individual points would then be multiplied by the according weight to get the total sum in each category (please see Table 2). Ivanis et al. (2008) empirically demonstrated that such a rating scale is a feasible tool for determining the appropriateness for authorship of individual contributions (see also Bates et al., 2004).

Principle 2

Upon completing the contributors’ list, investigators determine who will be mentioned in the article’s byline as an author. The Council of Science Editors states that a contribution to only one job category, even if this contribution is substantial, does not suffice for authorship; rather it requires contributions to two or three categories (Friedman, 2011). The guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2011) are more specific in this respect and many institutions, as for example the Office of Research Integrity (Steneck, 2007), closely follow these guidelines. According to these guidelines a contributor is also an author if he contributed…

1. … to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data,

AND

2. … to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content,

AND

3. … to final approval of the version to be published.

When job categories are organized into groups according to these criteria (cf., e.g., American Medical Association, 2011), a minimum level of points can be specified that must be obtained for each criterion for a contributor to be considered as an author (e.g., using the contribution form presented in Table 2, 20 points for each of the three criteria would be necessary to be granted authorship). As an author, the former contributor now takes responsibility for at least one component of the work, must be able to identify who is responsible for each of the other components, and ideally is confident in the co-authors’ ability and integrity (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, 2011). The authors determined in this way are listed in accordance to their position in the sorted contributors’ list in the byline list of the publication.

Principle 3

Despite the accountability of each author for his specific contribution, Rennie et al. (1997) demand naming one author “who also [has] made added efforts to ensure the integrity of the entire project” (p. 582). The guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2011) also require researchers to decide who will be the “guarantor” of the publication, that is, the person, who will take public responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from “inception to published article”. Although the American Psychological Association (2011) suggests that the first author should assume responsibility for the whole publication (American Psychological Association), it is of key importance that there is at least one author who takes responsibility for the whole project, independent of his position in the byline.

Principle 4

Additionally, coworkers decide on who will be the corresponding author. Getting chosen as corresponding author indicates, as Coats (2009), editor of the International Journal of Cardiology puts it, that the person in question “has the approval of all other listed authors for the submission and publication of all versions of the manuscript” (p. 149). It is also the responsibility of the corresponding author to get the written permission of all persons that should be acknowledged. The guidelines of the American Psychological Association (2011) describe the responsibility of the corresponding author as “making sure that (…) all authors have given their approval to the final draft, and [handling] responses to inquiries after the manuscript is published.”

Principle 5

Finally, as Rennie et al. (1997) suggested in their initial proposal, the complete contributors’ list should be disclosed in the publication. Here, the job categories that have been used may be explained in a more descriptive manner to give the reader a better understanding of what exactly the participating researchers did. Unless otherwise specified by the target journal, the information is included in a contributorship statement at the end of the paper or in a separate byline, as proposed by Weltzin et al., 2006; please see Appendix 1 of Devine et al., (2005 for an example of a contributorship statement). Similarly, to avoid an inappropriate attribution of credit and responsibility, it is very important to indicate explicitly, which of the authors is the guarantor, who is the corresponding author and which method was used for author sequencing (cf. Riesenberg and Lundberg, 1990; Tscharntke et al., 2007).

Recommendations

Recommendation A

Before the planned research actually starts, all participating scientists should come together and discuss openly who will be author of publications resulting from the research (cf. Erlen et al., 1997; Welsh et al., 2008). This is a major recommendation of the Committee on Publication Ethics (Albert and Wager, 2003). Strange (2008) emphasizes this recommendation in his extensive treatment of ethical authorship: “Every effort should be made to avoid authorship problems from the outset. Authorships should be negotiated and defined in writing at the beginning of an investigation. Frequent communication between all co-authors should occur while investigations are ongoing. Authorship should be discussed regularly and redefined in writing if necessary” (p. 572). As Strange (2008) states, the initial decision on who should be an author will most probably change during the progress of the project and will have to be reevaluated from time to time.

Recommendation B

Strange (2008) highlights the importance of defining the authors’ responsibilities. Together with the decision of who will be an author, all participating researchers should also discuss and agree upon the corresponding responsibilities of the designated authors. Wager (2009) arrives at the same conclusion in a recent paper for Maturitas: “Disputes could be reduced if authorship criteria were agreed, in writing, among all contributors at the start of a research project” (p. 109). For this purpose, institutional authorship policies or the “Instructions to authors” of eligible journals are considered. The minimal requirement, however, should be the principles described above.

Recommendation C

If technicians, statisticians, software developers, or other experts are involved in the current research, they should be asked whether they want to be become authors of corresponding publications. It is also of the utmost importance that it is clearly stated which contributions will allow them to become authors. Written standards as suggested by Strange (2008) and Wager 2009) will assure that authorship allocation is completely transparent for all experts involved.

Conclusion and Outlook

The aim of the present study was to contribute to the debate about authorship ethics in the field of Cognitive Science. By means of compiling best practice principles, I provide a reference tool that will hopefully help researchers in the field when deciding on how to fairly assign credit and responsibility in scientific publishing. The examples given demonstrate how the contributions to a research project can be determined. The system of determining authorship described here avoids the possibility that a person who was solely responsible for the acquisition of funding, collection of data, or general supervision of the research group will be author of a respective scientific publication. Furthermore, this system guarantees that all persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify are listed. Similarly, this system ensures that each author participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content (cf. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, 2011).

Who is benefiting the most from a transparent and fair system of allocating authorship is an open question. Some authors suggested that journal editors, and in particular readers of scientific articles will be the persons who will mostly use and therefore also mostly benefit from the disclosure of individual contributions to scientific publications. The rationale of this current study, however, is the view that clear principles may help to reduce authorship disputes and therefore authors would benefit the most. In a case study done in 2005 (Devine et al., 2005), authorship was determined in close resemblance to the system proposed here. Scientists reported that the contributorship approach is a convincing and promising way to “arrive at an equitable assignment of authorship” (p. 455). The authors concluded: “Post-study feedback, informally gathered from the investigators, revealed [the concept of contributorship] worked well. All agreed it clarified the order of the byline and averted potential disagreements concerning authorship” (p. 458).

Empirical studies clearly indicate that transparent standards of authorship, like the principles compiled in the present study, significantly improve the validity of authorship (cf., e.g., Marusic et al., 2006). Therefore, the systematic education of young, but also of senior scientists, with respect to ethical publication standards is crucially important (Heitman and Litewka, 2011). Furthermore, senior researchers and especially supervisors and mentors should actively promote authorship policies so that young researchers are not left guessing when it comes to determining authorship and are empowered to react appropriately when being confronted with unacceptable behavior displayed by colleagues (cf. Wagena, 2005). Moreover, active involvement from research institutions, universities, editors, and publishers in making ethical publication standards better known is recommended (Horner and Minifie, 2011a,b,c). Finally, it is believed that heightened awareness of the problem may already help reduce deviations from appropriate conduct.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Debbie Coetzee-Lachmann and Christopher Schuller for their help with the language editing and the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Funding/Support

This research was funded by a Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg stipend of the Ministry for Science and Culture of Lower Saxony, Germany.

References

Ahmed, S. M., Maurana, C. A., Engle, J. A., Uddin, D. E., and Glaus, K. D. (1997). A method for assigning authorship in multiauthored publications. Fam. Med. 29, 42–44.

Albert, T., and Wager, E. (2003). How to Handle Authorship Disputes: A Guide For New Researchers. The COPE Report 2003 (July 1). Available at: http://www.publicationethics.org/resources/guidelines

Altman, D. G., Goodman, S. N., and Schroter, S. (2002). How statistical expertise is used in medical research. JAMA 287, 2817–2820.

American Medical Association. (2011). JAMA Authorship Responsibility, Conflicts of Interest and Funding, and Copyright Transfer/Publishing Agreement. Available at: http://jam a.ama-assn.org/site/misc/ifora.xhtml#AuthorshipCriteriaandContribu tionsandAuthorshipForm [accessed July 30, 2011].

American Psychological Association. (2011). Publication Practices and Responsible Authorship. Available at: http://www.apa.org/research/responsible/publication/index.aspx [accessed July 1, 2011].

Bates, T., Anic, A., Marusic, M., and Marusic, A. (2004). Authorship criteria and disclosure of contributions: comparison of 3 general medical journals with different author contribution forms. JAMA 292, 86–88.

Benos, D. J., Fabres, J., Farmer, J., Gutierrez, J. P., Hennessy, K., Kosek, D., Lee, J. H., Olteanu, D., Russell, T., Shaikh, F., and Wang, K. (2005). Ethics and scientific publication. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 29, 59–74.

Bhopal, R., Rankin, J., McColl, E., Thomas, L., Kaner, E., Stacy, R., Pearson, P., Vernon, B., and Rodgers, H. (1997). The vexed question of authorship: views of researchers in a British medical faculty. BMJ 314, 1009–1012.

Cell Press. (2011). Research Focus Author Guidelines. Available at: http://www.cell.com/cellpress/trecogsci [accessed June 30, 2011].

Claxton, L. D. (2005a). Scientific authorship. Part 1. A window into scientific fraud? Mutat. Res. 589, 17–30.

Claxton, L. D. (2005b). Scientific authorship. Part 2. History, recurring issues, practices, and guidelines. Mutat. Res. 589, 31–45.

Cronin, B., Debora, S., and La Barre, K. (2003). A cast of thousands: coauthorship and subauthorship collaboration in the 20th century as manifested in the scholarly journal literature of psychology and philosophy. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 54, 855–871.

Devine, E. B., Beney, J., and Bero, L. A. (2005). Equity, accountability, transparency: implementation of the contributorship concept in a multi-site study. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 69, 455–459.

Dhaliwal, U., Singh, N., and Bhatia, A. (2006). Awareness of authorship criteria and conflict: survey in a medical institution in India. MedGenMed 8, 52.

Erlen, J. A., Siminoff, L. A., Sereika, S. M., and Sutton, L. B. (1997). Multiple authorship: issues and recommendations. J. Prof. Nurs. 13, 262–270.

Frazzetto, G. (2004). Who did what? Uneasiness with the current authorship is prompting the scientific community to seek alternatives. EMBO Rep. 5, 446–448.

Friedman, P. J. (2011). A new standard for authorship. Council of Science Editors. Available at: http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid [accessed July 1, 2011].

Goodman, N. W. (1994). Survey of fulfillment of criteria for authorship in published medical research. BMJ 309, 1482.

Heitman, E., and Litewka, S. (2011). International perspectives on plagiarism and considerations for teaching international trainees. Urol. Oncol. 29, 104–108.

Hoen, W. P., Walvoort, H. C., and Overbeke, A. J. (1998). What are the factors determining authorship and the order of the authors’ names? A study among authors of the Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (Dutch Journal of Medicine). JAMA 280, 217–218.

Horner, J., and Minifie, F. D. (2011a). Research ethics I: responsible conduct of research (RCR)–historical and contemporary issues pertaining to human and animal experimentation. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, S303–S329.

Horner, J., and Minifie, F. D. (2011b). Research ethics II: mentoring, collaboration, peer review, and data management and ownership. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, S330–S345.

Horner, J., and Minifie, F. D. (2011c). Research ethics III: publication practices and authorship, conflicts of interest, and research misconduct. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, S346–S362.

House, M. C., and Seeman, J. I. (2010). Credit and authorship practices: educational and environmental influences. Account. Res. 17, 223–256.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (2011). Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Ethical Considerations in the Conduct and Reporting of Research: Authorship and Contributorship. Available at: http://www.icmje.org/ethical_1 author.html [accessed April 14, 2011].

Ivanis, A., Hren, D. D., Sambunjak, D., Marusic, M., and Marusic, A. (2008). Quantification of authors’ contributions and eligibility for authorship: randomized study in a general medical journal. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 1303–1310.

Marusic, A., Bates, T., Anic, A., and Marusic, M. (2006). How the structure of contribution disclosure statements affects validity of authorship: a randomized study in a general medical journal. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 22, 1035–1044.

Marusic, M., Bozikov, J., Katavic, V., Hren, D., Kljakovic-Gaspic, M., and Marusic, A. (2004). Authorship in a small medical journal: a study of contributorship statements by corresponding authors. Sci. Eng. Ethics 10, 493–502.

Mowatt, G., Shirran, L., Grimshaw, J. M., Rennie, D., Flanagin, A., Yank, V., MacLennan, G., Gotzsche, P. C., and Bero, L. A. (2002). Prevalence of honorary and ghost authorship in Cochrane reviews. JAMA 287, 2769–2771.

Parker, R. A., and Berman, N. G. (1998). Criteria for authorship for statisticians in medical papers. Stat. Med. 17, 2289–2299.

Pignatelli, B., Maisonneuve, H., and Chapuis, F. (2005). Authorship ignorance: views of researchers in French clinical settings. J. Med. Ethics 31, 578–581.

Pimple, K. D. (2002). Six domains of research ethics. A heuristic framework for the responsible conduct of research. Sci. Eng. Ethics 8, 191–205.

Rennie, D., Yank, V., and Emanuel, L. (1997). When authorship fails. A proposal to make contributors accountable. JAMA 278, 579–585.

Riesenberg, D., and Lundberg, G. D. (1990). The order of authorship: who’s on first? JAMA 264, 1857.

Seeman, J. I., and House, M. C. (2010a). Influences on authorship issues: an evaluation of giving credit. Account. Res. 17, 146–169.

Seeman, J. I., and House, M. C. (2010b). Influences on authorship issues: an evaluation of receiving, not receiving, and rejecting credit. Account. Res. 17, 176–197.

Smith, E., and Williams-Jones, B. (2011). Authorship and responsibility in health sciences research: a review of procedures for fairly allocating authorship in multi-author studies. Sci. Eng. Ethics. PMID: 21312000. [Epub ahead of print].

Steneck, N. H. (2007). Introduction to the Responsible Conduct of Research, Washington, DC: Office of Research Integrity.

Strange, K. (2008). Authorship: why not just toss a coin? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C567–C575.

Tscharntke, T., Hochberg, M. E., Rand, T. A., Resh, V. H., and Krauss, J. (2007). Author sequence and credit for contributions in multiauthored publications. PLoS Biol. 5, e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050018

Verhagen, J. V., Wallace, K. J., Collins, S. C., and Scott, T. R. (2003). QUAD system offers fair shares to all authors. Nature 426, 602.

Wager, E. (2009). Recognition, reward and responsibility: why the authorship of scientific papers matters. Maturitas 62, 109–112.

Welsh, R. K., Lareau, C. R., Clevenger, J. K., and Reger, M. A. (2008). Ethical and legal considerations regarding disputed authorship with the use of shared data. Account. Res. 15, 105–131.

Weltzin, J. F., Belote, R. T., Williams, L. T., Keller, J. K., and Cayenne Engel, E. (2006). Authorship in ecology: attribution, accountability, and responsibility. Front. Ecol. Environ. 4, 435–441.

Wilcox, L. J. (1998). Authorship: the coin of the realm, the source of complaints. JAMA 280, 216–217.

Keywords: authorship, contributorship, scientific publishing, responsible conduct of research

Citation: Eggert LD (2011) Best practices for allocating appropriate credit and responsibility to authors of multi-authored articles. Front. Psychology 2:196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00196

Received: 17 May 2011; Accepted: 04 August 2011;

Published online: 01 September 2011.

Edited by:

Colin Davis, Royal Holloway University of London, UKCopyright: © 2011 Eggert. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Lucas D. Eggert, Institute of Cognitive Science, University of Osnabrück, Albrechtstrasse 28, 49076 Osnabrück, Germany. e-mail: leggert@uos.de