- 1Department of Childhood and Developmental Medicine, Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, Buzzi Children's Hospital, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

- 3Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome-NESMOS Department, Sant’Andrea University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated enteropathy caused by a permanent sensitivity to gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. In rare cases, CD may occur with a severe potential life-threatening manifestation known as a celiac crisis (CC). This may be a consequence of a delayed diagnosis and expose patients to possible fatal complications. We report the case of a 22-month-old child admitted to our hospital for a CC characterized by weight loss, vomiting, and diarrhea associated with a malnutrition state. Early identification of symptoms of CC is essential to provide a prompt diagnosis and management.

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a systemic and chronic immune-mediated disease that occurs in genetically predisposed individuals after dietary exposure to gluten (1). It is characterized by the presence of celiac-specific autoantibodies and inflammation of the small intestine, associated with a wide spectrum of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, resembling a multisystemic disorder (2).

CD prevalence is around 1% in most populations, with an increasing trend in the last few years due to both a rise in knowledge and increased autoimmunity, as revealed by seroprevalence reports of apparently asymptomatic subjects (3–6). The only effective treatment of CD is a life-long gluten-free diet (GFD) (7). Being a highly prevalent worldwide condition, CD has an important burden on lifestyle, but its evaluation is limited by undiagnosed asymptomatic patients and the lack of pharmacologic treatment (1).

Economic analyses demonstrated high costs, especially at the diagnosis, related to investigations and monitoring of the disease (8, 9). Moreover, the non-economic impact of the diet must be considered due to its relevance to psychological and social well-being (10, 11). The clinical presentation of CD is heterogeneous. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including constipation, bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, and recurrent abdominal pain, are the most frequent symptoms in the pediatric age range; however, extraintestinal or atypical symptoms such as dermatitis, failure to thrive, headache, anemia, delayed puberty, or dental enamel defects may be signs of CD (12–14).

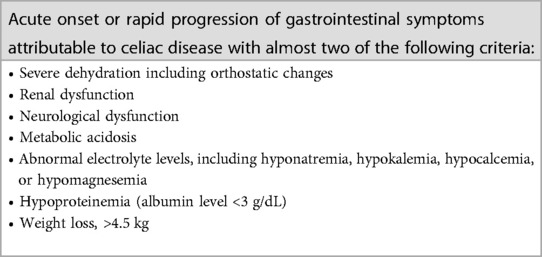

Celiac crisis (CC) is a severe medical emergency characterized by an acute onset or rapid progression of gastrointestinal symptoms requiring hospitalization and/or parenteral nutrition along with profuse diarrhea and consequent severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and hypoalbuminemia associated with neurologic and renal dysfunction.

The diagnostic criteria of CC are shown in detail in Table 1 (15–17).

CC is usually regarded as a complication of previously undetected celiac disease, rarely a consequence of non-compliance with the recommended GFD (16, 17).

We describe a case of a patient admitted to our emergency department for a severe life-threatening celiac crisis as the first manifestation of a previously unknown CD.

Case presentation

A 22-month-old boy was admitted to our emergency department because of episodes of vomiting after meals, associated with appetite loss and watery diarrhea, without fever. Symptoms have been noticed for the last 2 months. Parents also reported significant weight loss over the previous 6 months.

The patient was born at 37 weeks of gestation, had no significant perinatal history, and was breastfed for the first 9 months. No relevant clinical history was reported. All mandatory vaccinations were performed. His family history was unremarkable.

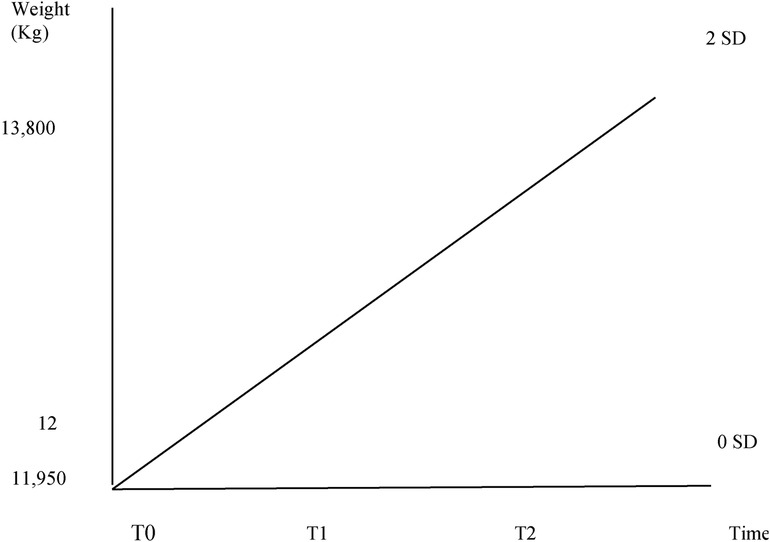

At our first evaluation, physical examination showed a dystrophic appearance with scarce subcutaneous tissues and signs of moderate dehydration (increased capillary refill time, sticky mucous membranes). Abdominal bloating and distension were present without any pain from palpation. The cardiothoracic examination was normal. Vital parameters were within range. His weight was 11.930 kg (0 SD according to WHO charts), while his length was 94 cm (between +2 and +3 SD according to WHO charts), with a body mass index of 13.50 kg/m2 (between −3 and −2 SD according to WHO charts).

The patient was admitted to our pediatric department for adequate investigation and treatment. Laboratory tests revealed normal full blood counts (leucocytes 14,780/MMC: N 44.7%, L 48.2%; Hb 14.7 g/dL, platelets 396,000/MMC) and electrolytes, negative inflammatory markers, and normal coagulation but a state of malnutrition (serum albumin level 2.56 g/dL, serum ferritin 9.6 ng/mL, vitamin D-25-OH 16.1 ng/mL, folate 1.99 ng/mL) and a slight increase of the transaminase levels (AST 73 U/L, ALT 62 U/L). Serology assays for HIV, CMV, HCV, HBV, and HAV were negative. Antinuclear antibodies were negative. The urine test was negative for proteinuria. Stool cultures for Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, Giardia sp., Cryptosporidium sp., Entamoeba histolytica, and fecal antigens for rotavirus and adenovirus were negative. The abdomen ultrasound was normal. Thyroid function analysis revealed hypothyroidism (TSH 7.92 microUI/mL, FT4 0.78 ng/mL); antithyroid peroxidase antibodies were 256.8 IU/mL (vn < 35 UI/mL) with normal value of antithyroglobulin antibody, and thyroid echography showed features of thyroiditis. Specific CD serological tests showed the presence of IgA anti-TG2 328 U/mL (n.v < 7 U/mL); IgA antiendomysial antibodies (EMA) were positive. Genetic testing revealed the presence of HLA DQA1*05,0201 and DQB1*0302.

Considering IgA anti-TG >10 times the normal value and EMA positivity in a second blood sample, the patient was diagnosed with CD according to the recent European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) guidelines, without undergoing esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (7).

An intravenous infusion of albumin (0.5 g/kg) and furosemide (1 mg/kg) was performed to correct hypoalbuminemia. Total parenteral nutrition was started and continued for 11 days. Intravenous methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day), progressively tapered, was administered for 10 days. Contextually, folate, vitamin D, and vitamin B12 were supplemented, and replacement thyroid therapy was started with levotiroxina 25 mg/day. Once clinically stable, a GFD was started.

During hospitalization, clinical conditions, hydration, and nutritional status slowly improved. Abdomen bloating resolved; stools became normal.

He was discharged on day 22 of hospitalization with a weight of 12 kg (0 SD according to WHO charts). Vitamin supplementation and thyroid hormone therapy were continued.

At 1 month's follow-up visit, he showed optimal general conditions and no nutritional deficits. His weight was 13.800 kg (between 0 and +2 SD according to WHO charts) (Figure 1).

Informed consent was received from the parents for the publication of this case report.

Discussion

CC is an urgent and life-threatening complication of CD (2, 18–21). The incidence of CC is not exactly known. Babar et al. reported a 5% incidence of CC (14); however, it has been considered a rarer manifestation of CD in other studies (22, 23). CC was first described by Andersen and Di Sant’agnese in 1953 when he reported the cases of 35 patients with CC, among which three were complicated by fatality (24). The mean age at presentation is generally early childhood, with highly variable ranges depending on the geographic area: in developing countries, CC onset is at a mean age of 5 years, while in high-outcome countries, such as our case report, a higher incidence of CC occurs in the first 2 years of life (25). Nevertheless, its frequency has drastically decreased in the last decades, probably due to a higher rate of early diagnosis. Moreover, vaccination, infection control, management, and availability of gluten-free diet have decreased the risk of CC (17, 25, 26).

CC may be a complication of an unrecognized CD or, less commonly, a consequence of non-compliance with a previously recommended GFD. CC must be differentiated from non-responsive-CD which is a type of CD which does not respond after 6–12 months on a GFD, extremely rare in children (27).

CC is characterized by severe acute onset of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with almost two of the diagnostic criteria reported in Table 1 (16, 17, 26). Without appropriate intervention, clinical conditions may rapidly worsen with electrocardiographic abnormalities, neuromuscular weakness, tetany, seizures, acute kidney injury, and circulatory collapse (28–30). CC may also be associated with other rare symptoms, such as neurological manifestations, including ataxia and myoclonus, and hematological manifestations, such as thrombocytopenia (14, 31).

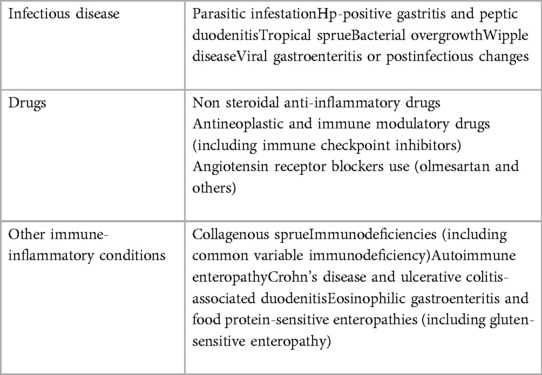

Even if not specific to CD, these symptoms can hint at the diagnosis of CC if a CD is already diagnosed; in the case of previously undetected CD, a differential diagnosis with other conditions could be considered (Table 2).

Due to its severe presentation, the possible alternative diagnosis could be infectious diarrhea. Therefore, a history of potential microbial exposures and laboratory data should be obtained to rule out infectious etiologies. Other conditions to consider that may mimic CC are tropical sprue, AIDS enteropathy, hypersensitivity to dietary proteins, Wipple's disease, intestinal lymphoma, collagenous sprue, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, use of laxatives, and pancreatic insufficiency.

In any case, patients with acute, severe, rapidly progressive gastrointestinal symptoms, if an infection is ruled out, should be tested for CD (15–17).

Therapeutic management of CC mainly consists of dealing with the life-threatening consequences of profuse diarrhea by fluid resuscitation, intravenous correction of the electrolyte imbalance, and albumin correction (27–32). Parenteral nutrition is generally required considering the massive malabsorption syndrome. As soon as clinically possible, starting a GFD represents the only etiologic treatment (33).

Corticosteroid's role in CC is controversial. In the literature, a good response of CC to steroids has been generally reported, as in our case report, since they can reduce intestinal inflammation and restore the brush border enzymes (34–37); however, Gupta and Kapoor reported two cases who deteriorated on steroids and one who improved without steroids: attention should be paid in their use mainly in the case of hypokalemia, which can worsen under steroids' kaliuresis effect, and in the case of probable underlying sepsis (38).

Our patient presented acute gastrointestinal symptoms associated with three of the diagnostic criteria (Table 1). The diagnosis of CD was based on the value of IgA anti-TG (>10 times the normal value) and EMA positivity, according to the recent ESPGHAN guidelines (7).

Moreover, as in our case report, an association between CD and autoimmune thyropathy (AIT) has been described (39). According to prevalence studies, the association between AIT and CD ranges from 2.4% to 40.4%, although their relationship is controversial (40–44). It was supposed that CD and AIT share one or more susceptibility genes, and the prolonged consumption of gluten in patients with undiagnosed CD may damage the intestinal barrier, leading to an alteration of the immune system (40). Other studies, instead, reported that exposure to gluten does not influence the development or the progression of autoimmune diseases (such as AIT, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, Addison disease, and primary Sjogren's syndrome) and GFD does not lessen the progression of autoimmune disease (45, 46). Guariso et al. assessed that GFD seems to have a good impact on autoimmune disease, although it does not have any effect on the progression of the autoimmune process if already started (47).

Conclusion

The present case highlights the possibility of CC as the first manifestation of CD. Although rarely encountered in clinical practice, this abrupt onset of CD requires hospitalization and immediate treatment (i.e., protein replacement, vitamin supplementation, and GFD) to avoid life-threatening complications. Therefore, prompt identification of symptoms has a crucial role in early diagnosis, management, risk stratification, and association with other autoimmune diseases.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Author contributions

AT, CD, FC, and AB drafted the manuscript; AM drafted, supervised and revised the manuscript; GD and LB revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the staff who contributed to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Semrad C, Kelly CP, Lebwohl B. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines update: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2023) 118:59–76. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002075

2. Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367:2419–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113994

3. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. (2021) 160:63–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

4. King JA, Jeong J, Underwood FE, Quan J, Panaccione N, Windsor JW, et al. Incidence of celiac disease is increasing over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. (2020) 115:507–25. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000523

5. Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, Johnson DR, Page W, Erdtmann F, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology. (2009) 137:88–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.059

6. Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, Laurila K, Collin P, Rissanen H, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2007) 26:1217–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03502.x

7. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, Kurppa K, Mearin ML, Ribes-Koninckx C, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2020) 70:141–56. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

8. Mårild K, Söderling J, Bozorg SR, Everhov ÅH, Lebwohl B, Green PHR, et al. Costs and use of health care in patients with celiac disease: a population-based longitudinal study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2020) 115:1253–63. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000652

9. Lee AR, Wolf RL, Lebwohl B, Ciaccio EJ, Green PHR. Persistent economic burden of the gluten free diet. Nutrients. (2019) 11:399. doi: 10.3390/nu11020399

10. Ho WHJ, Atkinson EL, David AL. Examining the psychosocial well-being of children and adolescents with coeliac disease: a systematic review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2023) 76:e1–14. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003652

11. Shah S, Akbari M, Vanga R, Kelly CP, Hansen J, Theethira T, et al. Patient perception of treatment burden is high in celiac disease compared with other common conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. (2014) 109:1304–11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.29

12. Persechino F, Galli G, Persechino S, Valitutti F, Zenzeri L, Mauro A, et al. Skin manifestations and coeliac disease in paediatric population. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3611. doi: 10.3390/nu13103611

13. Balaban DV, Dima A, Jurcut C, Popp A, Jinga M. Celiac crisis, a rare occurrence in adult celiac disease: a systematic review. World J Clin Cases. (2019) 7:311–9. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i3.311

14. Mehta S, Jain J, Mulye S. Celiac crisis presenting with refractory hypokalemia and bleeding diathesis. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). (2014) 12:296–7. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v12i4.13738

15. Babar MI, Ahmad I, Rao MS, Iqbal R, Asghar S, Saleem M. Celiac disease and celiac crisis in children. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. (2011) 21:487–90. PMID: 21798136.21798136

16. Waheed N, Cheema HA, Suleman H, Fayyaz Z, Mushtaq I, Muhammad X, et al. Celiac crisis: a rare or rarely recognized disease. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. (2016) 28:672–5. PMID: 28586591.28586591

17. Alvarez J, Gutiérrez C, Guiraldes E. Celiac crisis: a severe paediatric emergency. Rev Chil Pediatr. (1985) 56:422–7. doi: 10.4067/s0370-41061985000600004

18. Weir DC, Kelly C. Celiac disease. In: Duggan C, Watkins JB, Walker AW, editors. Nutrition in pediatrics. 4th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc (2008). p. 561–8.

19. Garrido I, Santos AL, Pacheco J, Peixoto A, Macedo G. Celiac crisis: a rare and life-threatening condition. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 33:1612–3. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002266

21. Poudyal R, Lohani S, Kimmel WB. A case of celiac disease presenting with celiac crisis: rare and life threatening presentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. (2019) 9:22–4. doi: 10.1080/20009666.2019.1571883

22. Baranwal AK, Singhi SC, Thapa BR, Kakkar N. Celiac crisis. Indian J Pediatr. (2003) 70:433–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02723619

23. Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. (2007) 357:1731–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600

24. Andersen DH, Di Sant’agnese PA. Idiopathic celiac disease. I. Mode of onset and diagnosis. Pediatrics. (1953) 11:207–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.11.3.207

25. Radlovic N, Lekovic Z, Radlovic V, Simic D, Vuletic B, Ducic S, et al. Celiac crisis in children in Serbia. Ital J Pediatr. (2016) 42:25–8. doi: 10.1186/s13052-016-0233-z

26. Mones RL, Atienza KV, Youssef NN, Verga B, Mercer GO, Rosh JR. Celiac crisis in the modern era. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2007) 45:480–3. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318032c8e7

27. Mooney PD, Evans KE, Singh S, Sanders DS. Treatment failure in coeliac disease: a practical guide to investigation and treatment of non-responsive and refractory coeliac disease. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. (2012) 21:197–203. PMID: 22720310.22720310

28. Hijaz NM, Bracken JM, Chandratre SR. Celiac crisis presenting with status epilepticus and encephalopathy. Eur J Pediatr. (2014) 173:1561–4. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2097-1

29. Bhattacharya M, Kapoor S. Quadriplegia due to celiac crisis with hypokalemia as initial presentation of celiac disease: a case report. J Trop Pediatr. (2012) 58:74–6. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr034

30. Kumar P, Badhan A. Hypokalemic paraparesis: presenting feature of previously undiagnosed celiac disease in celiac crisis. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2015) 19:501. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.162478

31. Oba J, Escobar AM, Schvartsman BG, Gherpelli JL. Celiac crisis with ataxia in a child. Clinics (São Paulo). (2011) 66:173–5. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322011000100031

32. Dunn RL, Stettler N, Mascarenhas MR. Refeeding syndrome in hospitalised pediatric patients. Nutr Clin Pract. (2003) 18:327–32. doi: 10.1177/0115426503018004327

33. Guarino M, Gambuti E, Alfano F, Strada A, Ciccocioppo R, Lungaro L, et al. Life-threatening onset of coeliac disease: a case report and literature review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. (2020) 7:e000406. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2020-000406

34. Catassi C. Celiac crisis/refeeding syndrome combination: new mechanism for an old complication. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2012) 54:442–3. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318242fe3a

35. Malamut G, Cording S, Cerf-Bensussan N. Recent advances in celiac disease and refractory celiac disease. F1000Res. (2019) 8:1–12. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18701.1

36. Lindo Ricce M, Rodriguez-Batllori Aran B, Jimenez Gómez M, Gisbert JP, Santander C. Non-responsive coeliac disease: coeliac crisis vs. Refractory coeliac disease with response to corticosteroids. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2017) 40:529–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2016.07.003

37. Lloyd-Still JD, Grand RJ, Khaw KT, Shwachman H. The use of corticosteroids in celiac crisis. J Pediatr. (1972) 81:1074–81. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(72)80234-8

38. Gupta S, Kapoor K. Steroids in celiac crisis: doubtful role! Indian Paediatr. (2014) 51:756–7. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0537-2

39. Minelli R, Gaiani F, Kayali S, Di Mario F, Fornaroli F, Leandro G, et al. Thyroid and celiac disease in paediatric age: a literature review. Acta Biomed. (2018) 89:11–6. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i9-S.7872

40. Meloni A, Mandas C, Jores RD, Congia M. Prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in children with celiac disease and effect of gluten withdrawal. J Pediatr. (2009) 155:51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.013

41. Ventura A, Neri E, Ughi C, Leopaldi A, Città A, Not T. Gluten-dependent diabetes-related and thyroid-related autoantibodies in patients with celiac disease. J Pediatr. (2000) 137:263–5. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107160

42. Kowalska E, Wąsowska-Królikowska K, Toporowska-Kowalska E. Estimation of antithyroid antibodies occurrence in children with coeliac disease. Med Sci Monit. (2000) 6:719–21. PMID: 11208398.11208398

43. Oderda G, Rapa A, Zavallone A, Strigini L, Bona G. Thyroid autoimmunity in childhood celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2002) 35:704–5. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200211000-00023

44. Kalyoncu D, Urganci N. Antithyroid antibodies and thyroid function in paediatric patients with celiac disease. Int J Endocrinol. (2015) 2015:276575. doi: 10.1155/2015/276575

45. Viljamaa M, Kaukinen K, Huhtala H, Kyrönpalo S, Rasmussen M, Collin P. Coeliac disease, autoimmune diseases and gluten exposure. Scand J Gastroenterol. (2005) 40:437–43. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012181

46. Ansaldi N, Palmas T, Corrias A, Barbato M, D'Altiglia MR, Campanozzi A, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease and celiac disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2003) 37:63–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00010

Keywords: celiac crisis, celiac disease, pediatrics, hypoalbuminemia, diarrhea, case report

Citation: Mauro A, Casini F, Talenti A, Di Mari C, Benincaso AR, Di Nardo G and Bernardo L (2023) Celiac crisis as the life-threatening onset of celiac disease in children: a case report. Front. Pediatr. 11:1163765. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1163765

Received: 11 February 2023; Accepted: 17 April 2023;

Published: 12 May 2023.

Edited by:

Simona Sestito, University "Magna Graecia," ItalyReviewed by:

Metin Cetiner, University of Duisburg-Essen, GermanyGianfranco Meloni, University of Sassari, Italy

Carmen Ribes-Koninckx, La Fe Hospital, Spain

© 2023 Mauro, Casini, Talenti, Di Mari, Benincaso, Di Nardo and Bernardo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angela Mauro YW5nZWxhLm1hdXJvODRAZ21haWwuY29t

Angela Mauro

Angela Mauro Francesca Casini2

Francesca Casini2 Giovanni Di Nardo

Giovanni Di Nardo