95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Organ. Psychol. , 20 October 2023

Sec. Employee Well-being and Health

Volume 1 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/forgp.2023.1284650

This study explored approved worker's compensation claims made by public safety personnel (PSP) with work-related psychological injuries to the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) of Ontario's Mental Stress Injury Program (MSIP) between 2017 and 2021. This worker's compensation program provides access to health care coverage, loss of earnings benefits, and return to work support services for psychologically injured workers. In 2016, the Government of Ontario amended legislation to presume that, for this population, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is work-related, potentially expanding access to the program. The aim of this study was to understand the volume and types of claims, return to work rates, and differences between PSP career categories in the first 5 years after the legislative change. Using a quantitative descriptive approach, statistical analysis revealed that claims increased over the 5-year period, with significantly more claims made in 2021 (n = 1,420) compared to 2017 (n = 1,050). Of the 6,674 approved claims, 33.5% were made by police, 28.4% by paramedics, 21.6% by correctional workers, 9.4% by firefighters, and 7.1% by communicators. Analysis of claim type revealed that police, firefighters, and communicators made more cumulative incident claims, while paramedics made more single incident claims. Differences were also observed in return to work rates, with fewer police officers, firefighters, and communicators assigned to a return to work program, and more paramedics successfully completing a return to work program. This study sheds light on differences among PSP in their WSIB Ontario MSIP claims and underscores the importance of continued research to develop a more robust understanding of these differences, to inform policy development for both employers and worker's compensation organizations.

In Canada, “Public Safety Personnel” (PSP), also called first responders, work to ensure the security and safety of the public and include communicators, correctional workers, firefighters, paramedics, and police, among others [Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT), 2019]. PSP are frequently exposed to potentially psychologically traumatic events (PPTE) including severe human suffering, violence, and death (Carleton et al., 2019a). Exposure to PPTE has been associated with increased rates of stress induced mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, and depression (Weathers et al., 2013; Carleton et al., 2019a). These illnesses can profoundly impact an individual's wellbeing, including mood, executive functioning, sleep patterns, and relationships (Lopez, 2011; Aupperle et al., 2012; American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Sareen, 2014).

In Ontario, a worker who has experienced a work-related psychological injury is eligible to apply for support through the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) of Ontario, as established by the Workplace Safety and Insurance Act (WSIA) (Government of Ontario, 1997). WSIB provides health care coverage, loss of earnings benefits, and return to work (RTW) services to injured workers with approved claims. Psychological injuries are managed under WSIB's Mental Stress Injury Program (MSIP), which includes the claim categories of chronic mental stress, traumatic mental stress, and PTSD (WSIB Ontario, 2023a). MSIP claims represent a significant human and financial cost for Ontario's public safety organizations and communities and include costs such as wage replacement while employees are on leave, backfilling vacant positions, and health-related claim costs (Conference Board of Canada, 2021). Between January 1, 2016, to April 30, 2020, WSIB Ontario approved 5,691 mental stress injury claims (MSIP) made by PSP workers (WSIB, 2020). The City of Toronto's WSIB costs increased from $16 million annually in 2010 to $45 million in 2022, with costs rising most notably among Toronto's fire, police, and paramedic services (Kopun, 2022). The number of MSIP claims involving PSP workers taking time off work during the course of their recovery increased from 0.3% in 2002 to 3% in 2020 (WSIB, 2020). Further compounding MSIP claim costs is the lengthy duration of mental health claims (Wilson et al., 2016) with half of the 1,529 WSIB MSIP claims made in Ontario between 2016 and 2020 lasting longer than 2 years in duration (Butler, 2021).

Prior to 2016, PSP were required to prove that their psychological injury was work-related for their WSIB claim to be approved. However, in recent years, both the Canadian government and the provincial government of Ontario made efforts to bolster support for the growing number of psychologically injured PSP. In 2016, the Government of Ontario passed Bill 163, the Supporting Ontario's First Responders Act (PTSD), amending the WSIA (Government of Ontario, 1997) and creating a statutory presumption that PTSD diagnosed in PSP is work-related, unless otherwise specified (Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 2016). Bill 163 provides PSP with simplified access to WSIB benefits and treatment; however, for PSP employers, these legislative changes may represent additional costs due to expanded benefit entitlements.

The goal of the current study was to explore WSIB MSIP claims made by Ontario PSP after the introduction of Bill 163 in 2016. Specifically, this study explored claims made between 2017 and 2021 and sought to answer the following questions: (1) Which PSP are making MSIP claims? (2) What is the nature of these claims? (3) How many PSP are successfully RTW? (4) What differences exist between PSP career categories?

This descriptive quantitative study explored approved WSIB Ontario MSIP claims of psychologically injured PSP between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2021. The claims included all MSIP categories (chronic mental stress, traumatic mental stress, and PTSD). Smaller career categories (managers in social, community, and correctional services, probation officers, fire chiefs and officers, by-law officers, and commissioned police) were combined with larger related career categories (correctional service officers, firefighters, and police officers) before statistical analysis. The data is reported in five PSP career categories: communicators, correctional workers, firefighters, paramedics, and police. Each claim included three categories of variables: (1) claimant specific variables (age, sex, PSP career category), (2) claim specific variables (year of claim, nature of claim, nature of injury), (3) RTW variable (RTW status). See Data Variable Table for further detail (Appendix A, Supplementary material).

All data was accessed through a data sharing agreement between WSIB and the first author. To protect the privacy of the study population, the terms of the data sharing agreement stipulated that summary data, and not individual claim level data, would be provided by the WSIB data analysis team. In the WSIB data summary, continuous variables were provided as means and the categorical variables were provided as counts. This study received ethical review and approval through the Queen's University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (HS-REB).

Data analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel (version 16) and SPSS Statistics (version 28). Chi-Square Tests of Independence and Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Tests were conducted to understand relationships between variables. Adjusted standardized residual Z scores were converted to p-values for post-hoc analysis of Chi-Square Tests of Independence.

Of the 6,674 PSP claimants analyzed, the largest number of claims were made by police (33.5%, n = 2,235), followed by paramedics (28.4%, n = 1,897), correctional workers (21.6%, n =1,441), firefighters (9.4%, n = 626), and communicators (7.1%, n = 475). Overall, claimants were predominantly male (66.8%, n = 4,459), on average 41.4 years of age and had worked as a PSP for an average of 18 years when they submitted an MSIP claim. See Table 1 for demographics of claimants; see Section 4.1 for information on the estimated number of these professionals working in Ontario.

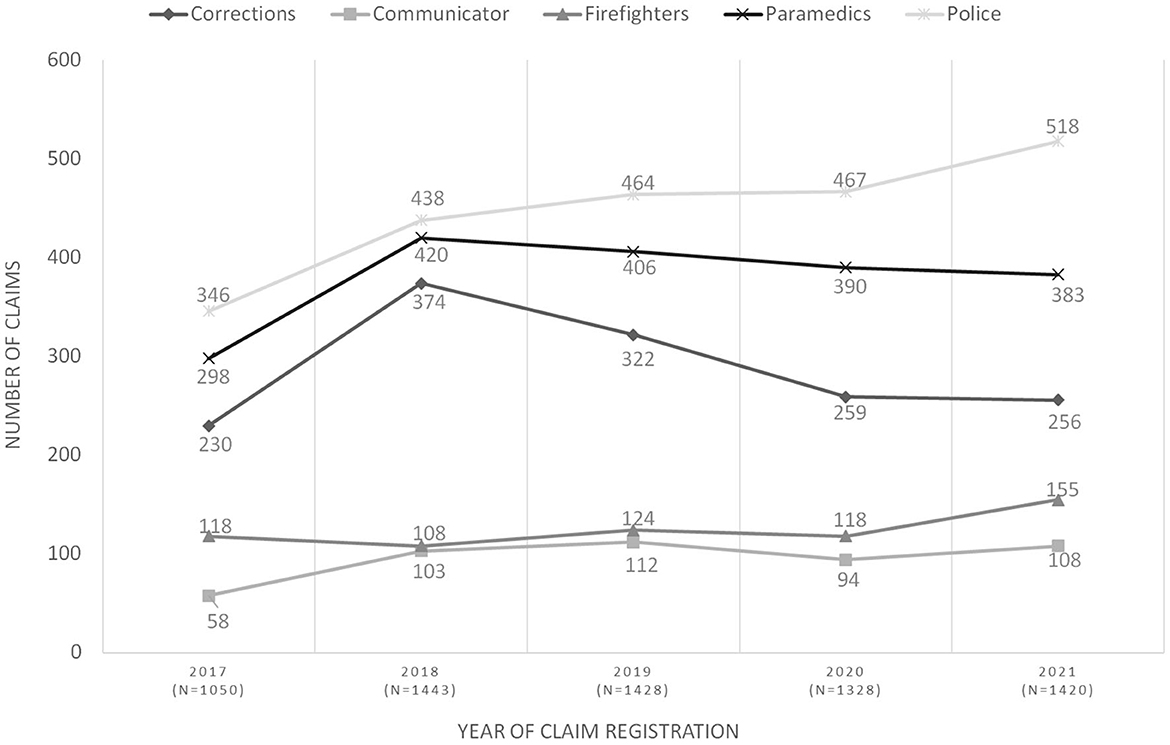

On average, 1,334 claims were made per year between 2017 and 2021; however, the number of claims increased from 2017 to 2021. A Chi-Square Goodness of Fit test performed to determine whether the proportion of claims was equal between 2017 and 2021 revealed that significantly more claims were made in 2021 (n = 1,420) compared to 2017 (n = 1,050), X2(1, N = 2,470) = 55.425, p < 0.001. See Figure 1 for further details on the number of claims per year for each PSP career category.

Figure 1. Number of approved WSIB MSIP claims by PSP career categories between 2017 and 2021. Year of Claim Registration data was missing for 0.07% (n = 5) claimants. Those claimants were not included in this graph. A Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test was performed to determine whether the proportion of claims was equal between 2017 and 2021 and revealed that significantly more claims were made in 2021 (n = 1,420) compared to 2017 (n = 1,050), X2 (1, N = 2,470) = 55.425, p < 0.001.

Injuries leading to MSIP claims were categorized by WSIB as either “single event” injuries or “cumulative event” injuries, with single event injuries defined by WSIB as being caused by a one-time traumatic event, while “cumulative events” were caused by multiple traumatic exposures or substantial work-related stressors. A Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test, performed to determine whether the proportion of single and cumulative event injuries were equal, revealed that most claims were made due to cumulative events (55.9%, n = 3,730), with single event injuries comprising 41.2% (n = 2,748) of claims, X2(1, N = 6,478) = 148.861, p < 0.001.

A Chi-Square Test of Independence revealed a relationship between the cause of injury and PSP career category X2(4, N = 6,478) = 421.743, p < 0.001. Post-hoc analysis showed that police (66.7%, n = 1,451; p < 0.001), firefighters (77.6%, n = 471; p < 0.001), and communicators (64.5%, n = 302; p = 0.05) made a greater number of cumulative events claims, while paramedics (60.1%, n = 1,116; p < 0.001) made a greater number of single events claims. See Table 2 for further detail.

Claims were categorized as: (a) requiring time off work while seeking treatment (“time lost from work”), or b) not requiring time off and continuing to work while seeking treatment (“no time lost from work”; Table 2). A Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test revealed that most claims (91.9%, n = 6,130) involved time off work, X2(1, N = 6,666) = 4694.395, p < 0.001. A Chi-Square Test of Independence revealed differences in claim type and career category, X2(4, N = 6,666) = 86.823, p < 0.001. According to post-hoc analysis, correctional workers made significantly more claims involving lost work time (95%, n = 1,368; p < 0.001), while firefighters made significantly fewer lost work time claims (83.3%; n = 518; p < 0.001). No other differences were observed among the PSP career categories.

The dataset also contained information regarding the average number of days off work for those who lost time from work for each career category. On average, paramedics had the fewest days off work (269.7 days/~9 months), while firefighters had the most days (522.6 days/~17 months). Communicators had an average of 512.1 days off work, while correctional workers had 477.5 days and police 467.4 days. See Table 2 for further detail.

The RTW status of each claim fell into one of three categories. The category “RTW Successful” indicated that the injured worker returned to work successfully, “RTW Unsuccessful” indicated that an injured worker attempted to RTW but was unable to, and “Never Assigned to a RTW Program” included injured workers who did not participate in RTW as they had not been assigned to a RTW program by WSIB. Over half of the claimants had been assigned to a RTW program (54.5%, n = 3,636), while 45.5% (n = 3,038) had never been assigned to RTW program at the time of data collection. Of the claimants who were assigned to a RTW program, 96.7% (n = 3,517) were successful in RTW. It is important to note that there is no specified time limit to a claim's duration; each worker's ability to return to work is individually assessed by WSIB and the worker's healthcare team throughout the claim duration.

For claimants who were assigned to a RTW program, a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test was performed to determine whether the proportion of claims was equal between those who successfully RTW and those who did not, revealing that the majority who attempted to return did so successfully X2(1, N = 3,636) = 3175.579, p < 0.001. Additionally, a Chi-Square Test of Independence exploring the relationship between RTW outcome (RTW Successful, RTW Unsuccessful, and Never Assigned to RTW Program) and career category revealed a significant relationship between the two variables, X2(8, N = 6,674) = 340.699, p < 0.001. Post-hoc analysis showed that more police (53.3%, n = 1,191; p < 0.001) and firefighters (62.3%, n = 390; p < 0.001) did not participate in RTW, while a greater proportion of paramedics (68.6%, n = 1,302) RTW successfully (p < 0.001). Table 3 presents RTW outcomes across PSP career categories.

This study explored approved worker's compensation claims made by psychologically injured PSP to the WSIB of Ontario's Mental Stress Injury Program between 2017 and 2021. The aim of this study was to understand the volume and types of claims, return to work rates, and differences between PSP career categories in the first 5 years after legislative change improved access to worker's compensation benefits for psychologically injured PSP. The study revealed that MSIP claims increased over the 5-year period after the introduction of Bill 163, with significantly more claims made in 2021 compared to 2017. Police made the largest amount of claims, followed by paramedics, correctional workers, firefighters, and communicators. Paramedics differed from other PSP in that they were more likely to make a claim after a single traumatic incident rather than a claim that was attributed to cumulative traumatic events. The study also revealed notable differences in RTW rates, with more paramedics successfully making a return, while fewer police officers, firefighters, and communicators had ever been assigned to a RTW program.

Of the 6,674 MSIP claims made to WSIB by PSP between 2017 and 2021, a third of the claims were made by police (33.5%), 28% by paramedics, 22% by correctional workers, with the fewest claims made by firefighters (9%) and communicators (7%). Although it is difficult to quantify the total number of PSP in the province of Ontario as they work for a variety of employers, some organizations provide estimates. Statistics Canada (2021) estimates there are 37,880 police personnel who work in Ontario, with 26,100 of those personnel working on the front line as police officers. Our study suggests that between 6 and 8% of those workers made a MSIP claim between 2017 and 2021. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (2021) reports that there are 9,997 paramedics working in the province; our findings suggest that approximately 19% of these workers made a MSIP claim between 2017 and 2021. The Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs (2023) estimates that 30,000 firefighters work in Ontario, including 18,000 volunteer firefighters and 12,000 career/full-time firefighters (typically only career firefighters are eligible for WSIB benefits). Our data suggests that about 5% of eligible firefighters made a MSIP claim between 2017 and 2021. Correctional workers in Ontario work both provincially and federally, with the Ontario provincial government reporting 7,200 total correctional workers (including front line and all other staff) (Auditor General of Ontario, 2019). The Correctional Service Canada reports 18,000 total employees in Canada, of which almost 8,000 are front line workers, making it difficult to say definitively how many work in Ontario; however, Ontario is the most populous province in Canada, and has 12 of the country's 43 federal correctional institutions (Correctional Service Canada, 2023). Communicators are more difficult to quantify as they work for a variety of organizations and may be combined across emergency services; however, the Ontario Paramedic Association (2023) reports that there are 1,200 communicators who support paramedic emergency responses, and others may be captured within the Statistics Canada (2021) estimate of total police personnel.

Given that police officers appear to be the most numerous professionals in Ontario, it is not surprising that they have the largest number of claims in the sample. However, with paramedics reported as a smaller proportion of professionals in the province in comparison to police, and a similar proportion to career firefighters, paramedics having 203% more claims than firefighters and only 15% fewer claims than police is notable. Further, 39.5% of paramedic claims came from females, where only 7.8% of firefighter claimants and 24.2% of police claimants were female. Research demonstrates that female PSP may be more likely to be diagnosed with mental health conditions and seek help, which also reflects sex and gender differences in diagnosis and help-seeking similar to the general Canadian population (Carleton et al., 2018). It is also possible that the nature and frequency of trauma exposure differs between paramedics, police, and firefighters. Although all PSP can expect exposure to PPTEs throughout their careers, a recent Canadian study found that paramedics have more PPTE exposures than most other PSP, including above average exposure to severe human suffering (Carleton et al., 2019a). Due to the difficulty quantifying both correctional workers and communicators in the province, it is not possible to comment on the proportionality of their claim volume.

Our study showed that MSIP claim volume increased for PSP between 2017 (n = 1,050) and 2021 (n = 1,420). This increase is consistent with WSIB's 2019 annual report, where it was noted that MSIP claims were increasing at a higher rate than most other claim categories (WSIB Ontario, 2019). Additionally, the City of Toronto, Ontario's largest city, which includes police, paramedics, firefighters, and communicators in their budget, recently reported that claims for mental/emotional illnesses/disorders represent the largest portion of their WSIB costs (City of Toronto, 2023).

Current research shows that many PSP report a large number of PPTE over the course of their careers (Carleton et al., 2019a), consistent with the finding that a higher proportion of overall MSIP claims were due to cumulative trauma vs. singular incidents. Additionally, past research indicates that PSP mental health symptoms increase with years of experience and exposure to more traumatic events (Carleton et al., 2018). This may potentially explain why paramedics, who were younger (mean age 37.8 years old), made more single incident claims (60.1%) than communicators, police, and firefighters, who were older on average (mean age 42.5, 43.2, and 46.6 years old, respectively) and made more cumulative incident claims (64.5, 66.7, and 77.6%, respectively).

In this study, a higher proportion of firefighters remained at work after making a claim, while more correctional worker claims involved lost time from work. This finding is congruent with research by Khan (2022), who explored the intervention perspectives of PSP families. Khan's study noted that stronger social ties within firefighter culture might protect against mental illness. This suggests that the unique culture and support systems within the firefighter community may play a role in encouraging them to remain present in their work roles, reducing lost time from work. Similarly, Isaac and Buchanan (2021) found that in a large fire department in British Columbia, those who reported higher levels of peer support also reported lower levels of occupational stress, highlighting the importance of peer support in reducing stress among firefighters, potentially reducing the lost time from work. In addition, a study by Carleton et al. (2019b) demonstrated that RCMP and correctional workers reported the highest levels of stress, while firefighters reported the lowest levels of stress with respect to organizational stressors. This may help explain why correctional workers registered more claims involving lost time from work, while firefighters registered fewer claims involving lost time.

Our results demonstrated that paramedic claimants were younger on average, had the highest proportion of female claimants, had more claims approved under the single traumatic event category, and were more likely to RTW. As discussed above in the “Injury types” section, longer lengths of service are associated with an accumulation of trauma exposures and their negative impact on mental health (Carleton et al., 2018, 2019a,b). Additionally, paramedics are healthcare providers, who may have enhanced knowledge of mental health. A study by Krakauer et al. (2020) found that among all PSP categories, paramedics had the highest mental health knowledge and the lowest stigma, potentially leading paramedics to seek support earlier and receive treatment after a single event rather than waiting until an accumulation of traumatic events. In addition, fewer police claimants were assigned to a RTW program and returned to employment. Despite a high need for mental health services, treatment-seeking among police has been found to be low due to workplace and organizational barriers, including stigma, working in understaffed conditions, and workplace repercussions such as not receiving a promotion due to disclosure (Rose and Unnithan, 2015; Ricciardelli et al., 2019; Edwards and Kotera, 2020). The literature has also shown that perceptual barriers play a part in reducing help-seeking behaviors for police, who are more likely to confide in spouses and friends, even when the organization strives to make mental health support normative (Reavley et al., 2018; Carleton et al., 2020).

Overall, our study found that the majority of PSP who were assigned to a RTW program and participated in WSIB's RTW process returned to employment successfully. However, 45.5% of PSPs in our sample had not been assigned to a RTW program. Further, the average days lost from work in our sample was 422 days (~14 months), with firefighters losing the most days at 523 days (~17 months). These numbers differ from WSIB claims generally, where WSIB reports that 9 out of 10 injured workers RTW within 12 months of their injury (WSIB Ontario, 2023b). It is possible that MSIP claims are more complex than other WSIB claim types, or that traditional RTW models that are based on physical injuries do not have similar utility with trauma-related claims.

PSP engage in inherently difficult work and their mental health is impacted by a combination of factors including complex operational, organizational, and personal factors; however, to date, the workplace mental health strategies of PSP employers have predominantly focused on resiliency and stress management interventions rather than addressing the impact of organizational factors (Edgelow et al., 2021, 2022). Additionally, a study of Ontario PSP with an approved WSIB claim for a psychological injury recently found that survey respondents were dissatisfied with both the support of WSIB and their employers in the RTW process, and that PSP often had difficulty receiving the accommodations they felt were needed to enable their return to the workplace (Edgelow et al., 2023b). The findings of this current study bring the growing concerns surrounding PSP mental health into sharper focus. With 45.5% of the PSPs in our sample not assigned to a RTW program at the time of data collection, and the majority not returning to work for over a year after having their claims approved, our findings highlight the need for a more coordinated approach to address Ontario PSP's psychological injuries.

The growing number of psychological injuries among PSPs and stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic make this a pressing area of research. Historically, the efforts of the research community have focused on exploring operational, organizational, and personal factors known to impact PSP mental health separately or within a single PSP profession, thus failing to adopt a broader conceptual approach to understanding and supporting PSP mental health. Our findings underscore a need for a new approach to address the mental health needs of PSP, an approach that explores the combined impacts of operational, organizational, and personal factors on PSP mental health (Edgelow et al., 2023a). Given the complexity of the issue at stake and the wide ranging personal and social impacts of not adequately supporting PSP's mental health in an often-overburdened healthcare system, this is an area of grave concern for many communities.

There are indications in Ontario that the numbers of PSP who are struggling with mental health concerns are staggering. The prevalence of mental disorders and symptoms among Ontario-based PSP may be far higher than indicated by the number of WSIB Ontario MSIP claims made by PSP in recent years. A study exploring Canadian PSP mental health found that the prevalence of symptoms of at least one mental health disorder was four times (44.5%) that of the general Canadian population (10.1%) (Pearson et al., 2013; Carleton et al., 2018). Given that not every psychologically injured PSP will make a WSIB claim, and with our data revealing that many accumulate injuries before making a claim, the WSIB claims explored in this study represent only a portion of psychological injuries currently present among PSP in Ontario. Further, the number of Ontario based PSP experiencing mental health challenges is expected to grow. The Ontario provincial government estimates that over 13,000 first responders have PTSD, with the number projected to grow to over 16,000 by 2040 due in part to the exacerbating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (Office of the Premier, Health and Office of the Solicitor General, 2022).

This study found marked differences among PSP professions in trends related to MSIP claims. Paramedics differed in a variety of ways from the broader PSP sample, making claims at a younger age, earlier in their careers, with more single incident claims, and being more likely to return to work. Based on estimates of the number of these professions in Ontario, paramedics also had a higher volume of claims when compared proportionally to police and firefighters. The reasons for these differences are not yet clear, however, one key difference between paramedics and other PSP in this sample is that paramedics interface more directly with the overburdened Ontario healthcare system. Given reports of chronic understaffing of paramedics, growing levels of burnout, and retention issues across provincial paramedic services (Frangou, 2022; Jeffords, 2023; Mercer, 2023), paramedics may be facing immense and unique pressures at work. It is also possible that the nature of paramedic employment, which is more likely to be part-time compared to some PSP groups in Ontario, may necessitate a return to work earlier than police, corrections workers, and career firefighters, who are more often full-time workers and part of provincial and national labor unions, potentially receiving higher wage replacement than paramedics.

The findings of this study should be viewed as a first step toward gaining a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding the pressing mental health needs of workers in Ontario where psychological injuries are costly to all those impacted. WSIB Ontario is solely funded by employer-paid premiums, administration fees, and investment revenue. As of July 2023, WSIB premiums collected for 2023 amounted to $1.75 billion and included 139,000 registered claims (WSIB Ontario, 2023c). One thousand one hundred and seventy-one of these 2023 claims were mental stress related, albeit not all made by PSP (WSIB Ontario, 2023c). With the number of MSIP claims growing annually in Ontario, the costs associated with these claims will continue to increase. Our findings point to a need to re-examine our approach to how workers' mental health needs are addressed in Canada's most populous province, especially among some of the most vulnerable workers serving our communities.

This study had several limitations. The data provided by WSIB to the research team was in summary format, limiting possible statistical tests and the ability to explore claim-level differences in the data. Personal characteristics like marital status, socioeconomic status, and race were not included in the data received from WSIB and thus the impact of these variables was not analyzed. For continuous variables, means were provided by WSIB without the inclusion of standard deviations and median values. Accordingly, statistical analyses on means could not be conducted. Only claims that were active starting in 2017 and up to 2021 were provided by WSIB, limiting the research team's ability to investigate changes to MSIP claims before and after the introduction of Bill 163. Changes in claims since the end of 2021 are also unknown. Future research could address these limitations by seeking individual claim-level data from WSIB to better understand the influence of individual claimant characteristics and sociodemographic variables on claim type, frequency, duration, and RTW outcomes. A longer study timeframe could also be used to explore changes before and after Bill 163 in more detail, as well as potential changes to claims since 2021.

The results of this study indicate that PSPs whose WSIB claims were linked to a single traumatic event, such as paramedics, were more likely to RTW compared to claims that were linked to cumulative traumatic events. This finding suggests that PSPs would benefit from proactive mental health supports to manage the impact of cumulative work-related trauma exposures, as well as prompt approval of worker's compensation claims and access to related healthcare and RTW supports when needed. Research is continuing to evolve in this area, and this study is the first to quantify the number of WSIB Ontario MSIP claims in the first 5 years since presumptive PTSD legislation came into force in Ontario in 2016. Worker's compensation organizations can mitigate the impact of psychological injury claims by ensuring claimants have rapid access to treatment from competent healthcare professionals who can provide work-focused interventions, while employers should review their accommodation and work modification procedures to ensure that workers are returned to work quickly and with necessary workplace supports (Edgelow et al., 2023b). Future research should explore individual claim-level data to better understand the influence of individual claimant characteristics on claim type, frequency, duration, and RTW outcomes. With the number of PSPs with work-related psychological injuries projected to grow in Ontario, it is imperative that research develop further in this area to inform policy development for both employers and worker's compensation organizations.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the original data set used in this study is owned by the Workplace Safety Insurance Board of Ontario and is not publicly available due to privacy guidelines. Data inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZWRnZWxvd21AcXVlZW5zdS5jYQ==.

The studies involving humans were approved by Queen's University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

ME: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft, review, and editing, Formal analysis, Resources. SB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, review, and editing, Conceptualization, Visualization. AF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, review, and editing, Conceptualization, Visualization.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by a 2022 Strategic Priorities Research Grant from the Ontario Society of Occupational Therapists.

Thank you to Renee Perrott for her literature searching to support the Introduction and Discussion sections. Thank you to Matthew Mayer for his support with data access at WSIB Ontario.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/forgp.2023.1284650/full#supplementary-material

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Auditor General of Ontario (2019). Ministry of the Solicitor General: Adult Correctional Institutions. Available online at: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en19/v3_100en19.pdf

Aupperle, R. L., Melrose, A. J., Stein, M. B., and Paulus, M. P. (2012). Executive function and PTSD: disengaging from trauma. Neuropharmacology 62, 686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.008

Butler, C. (2021). Ontario Officers Have Guaranteed PTSD Benefits. Now the Police Brass Wants to Change That. CBC News. Available online at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/ontario-police-ptsd-benefits-oacp-1.6119084

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2021). Health Workforce in Canada: Overview. Available online at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/health-workforce-in-canada-overview

Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT) (2019). Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma (version 2.1). Regina, SK: Author. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10294/9055

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., Krakauer, R., Anderson, G. S., et al. (2019a). Exposures to potentially traumatic events among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 51, 37. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000115

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., Mason, J., Ricciardelli, R., et al. (2019b). Assessing the relative impact of diverse stressors among public safety personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 1234. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041234

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Duranceau, S., LeBouthillier, D. M., et al. (2018). Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 63, 54–64. doi: 10.1177/0706743717723825

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Vaughan, A., Anderson, G. J., et al. (2020). Mental health training, attitudes toward support, and screening positive for mental disorders. Cogn. Behav. Therapy 49, 55–73. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2019.1575900

City of Toronto (2023). Occupational Health and Safety Report: End of Year 2022. Available online at: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2023/gg/bgrd/backgroundfile-237716.pdf

Conference Board of Canada (2021). Assessing the risk: The Occupational Stress Injury Resiliency Tool. Available online at: https://terraform-20180423174453746800000001.s3.amazonaws.com/attachments/cl3k7mbet3u11gnlwfxi6w9u0-assessing-the-risk-the-occupational-stress-injury-resiliency-tool.pdf

Correctional Service Canada (2023). CSC Statistics: Key Facts and Figures. Available online at: https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/publications/005007-3024-en.shtml

Edgelow, M., Fecica, A., Kohlen, C., and Tandal, K. (2023a). Mental health of public safety personnel: developing a model of operational, organizational, and personal factors in public safety organizations. Front. Public Health 11:1140983. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1140983

Edgelow, M., Legassick, K., Novecosky, J., and Fecica, A. (2023b). Return to work experiences of Ontario public safety personnel with work-related psychological injuries. J. Occup. Rehabil. 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10926-023-10114-6

Edgelow, M., Scholefield, E., McPherson, M., Legassick, K., and Novecosky, J. (2022). Organizational factors and their impact on mental health in public safety organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 13993. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192113993

Edgelow, M., Scholefield, E., McPherson, M., Mehta, S., and Ortlieb, A. (2021). A review of workplace mental health interventions and their implementation in public safety organizations. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 95, 645–664. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01772-1

Edwards, A., and Kotera, Y. (2020). Mental health in the UK police force: a qualitative investigation into the stigma with mental illness. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 19, 1116–1134. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00214-x

Frangou, C. (2022). Canadian Paramedics Are in Crisis. Macleans. Available online at: https://macleans.ca/longforms/canadian-paramedics-are-in-crisis/

Government of Ontario (1997). Workplace Safety and Insurance Act. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/97w16

Isaac, G. M., and Buchanan, M. J. (2021). Extinguishing stigma among firefighters: an examination of stress, social support, and help-seeking attitudes. Psychology 12, 349–373. doi: 10.4236/psych.2021.123023

Jeffords, S. (2023). Toronto's Paramedic Service Struggles to Keep Pace Amid Burnout, Competitive Job Market. CBC News. Available online at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-paramedic-retention-challenges-1.6809892

Khan, K. (2022). Intervention perspectives of public safety personnel (PSP) families (Unpublished master's thesis). Calgary, AB: University of Calgary.

Kopun, F. (2022). Toronto's WSIB Costs for First Responders Are Expected to Soar to $45 Million This Year. Toronto Star. Available online at: https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2022/02/08/ptsd-claims-among-torontos-first-responders-fuel-the-citys-soaring-wsib-costs.html

Krakauer, R. L., Stelnicki, A. M., and Carleton, R. N. (2020). Examining mental health knowledge, stigma, and service use intentions among public safety personnel. Front. Psychol. 11, 49. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00949

Legislative Assembly of Ontario (2016). Bill 163, Supporting Ontario's First Responders Act (Posttraumatic Stress Disorder). Available online at: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/parliament-41/session-1/bill-163

Lopez, A. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder and occupational performance: Building resilience and fostering occupational adaptation. Work 38, 33–38. doi: 10.3233/wor-2011-1102

Mercer, S. (2023). Paramedics Pushed ‘To The Max' Hope New Committee Will Help. Canadian Occupational Safety. Available online at: https://www.thesafetymag.com/ca/topics/government-and-public-sector/paramedics-pushed-to-the-max-hope-new-committee-will-help/438404

Office of the Premier, Health and Office of the Solicitor General (2022). Ontario Improving Access to Best-in-Class Mental Health Supports for First Responders. Available online at: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1001690/ontario-improving-access-to-best-in-class-mental-health-supports-for-first-responders

Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs (2023). About the OAFC. Available online at: https://www.oafc.on.ca/about#:~:text=Those%20departments%20are%20comprised%20of,and%20464%20part%2Dtime%20firefighters

Ontario Paramedic Association (2023). Main Page. Available online at: https://www.ontarioparamedic.ca

Pearson, C., Janz, T., and Ali, J. (2013). Health at a Glance: Mental and Substance Use Disorders in Canada. Statistics Canada. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.pdf?st=ZxvLwJH4

Reavley, N. J., Milner, A., Martin, A. J., Too, L. S., Papas, A., Witt, K., et al. (2018). Depression literacy and help-seeking in Australian police. Austral. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 52, 1063–1074. doi: 10.1177/0004867417753550

Ricciardelli, R., Groll, D., Czarnuch, S., Carleton, R. N., and Cramm, H. (2019). Behind the frontlines: exploring the mental health and help-seeking behaviours of public safety personnel who work to support frontline operations. Annu. Rev. Interdiscipl. Justice Res. 8, 315–348. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa007

Rose, T., and Unnithan, P. (2015). In or out of the group? Police subculture and occupational stress. Policing 38, 279–294. doi: 10.1108/pijpsm-10-2014-0111

Sareen, J. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Can. J. Psychiatry 59, 460–467. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900902

Statistics Canada (2021). Police Personnel and Selected Crime Statistics. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3510007601andpickMembers%5B0%5D=1.7andcubeTimeFrame.startYear=2017andcubeTimeFrame.endYear=2021andreferencePeriods=20170101%2C20210101

Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., and Keane, T. M. (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Available online at: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp

Wilson, S. J., Guliani, H., and Boichev, G. (2016). On the economics of post-traumatic stress disorder among first responders in Canada. J. Commun. Saf. Wellbeing 1, 26. doi: 10.35502/jcswb.6

WSIB (2020). By the Numbers: Open Data Downloads 2020. Available online at: https://www.wsib.ca/en/bythenumbers/open-data-downloads

WSIB Ontario (2019). Annual Report. Available online at: https://www.wsib.ca/sites/default/files/2020-08/2019_annual_report.pdf

WSIB Ontario (2023a). Operational Policy Manual. Available online at: https://www.wsib.ca/en/operational-policy-manual/claims/course-and-arising-out

WSIB Ontario (2023b). Return to Work. Available online at: https://www.wsib.ca/en/businesses/return-work/return-work

WSIB Ontario (2023c). Health and Safety Statistics. Available online at: https://safetycheck.onlineservices.wsib.on.ca/safetycheck/explore/provincial/SH_12?lang=en

Keywords: occupational health, public safety, first responders, workers compensation, posttraumatic stress disorder, mental health

Citation: Edgelow M, Brar S and Fecica A (2023) Worker's compensation usage and return to work outcomes for Ontario public safety personnel with mental stress injury claims: 2017–2021. Front. Organ. Psychol. 1:1284650. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2023.1284650

Received: 28 August 2023; Accepted: 29 September 2023;

Published: 20 October 2023.

Edited by:

Anja Baethge, Medical School Hamburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Scott Lawrence Martin, Zayed University, United Arab EmiratesCopyright © 2023 Edgelow, Brar and Fecica. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Megan Edgelow, ZWRnZWxvd21AcXVlZW5zdS5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.