95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Nutr. , 20 December 2024

Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1474995

This article is part of the Research Topic Sustainable Diets with Sociocultural and Economic Considerations View all 18 articles

Sileshi Mulatu1*

Sileshi Mulatu1* Lemessa Jira Ejigu2

Lemessa Jira Ejigu2 Habtamu Dinku3

Habtamu Dinku3 Fikir Tadesse1

Fikir Tadesse1 Azeb Gedif1

Azeb Gedif1 Fekiahmed Salah4

Fekiahmed Salah4 Hailemariam Mekonnen Workie1

Hailemariam Mekonnen Workie1Background: Inadequate dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months remains a public problem in Ethiopia. Adequate dietary diversity is crucial for children to meet their nutritional demands and promote healthy growth and development in infancy and young childhood.

Objective: The study aimed to assess dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Awi Zone, Ethiopia, 2023.

Methods: The study was conducted among children aged 6–23 months in Awi Zone, Amhara, Ethiopia, from August to September 2023. A community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted. A simple random sampling approach followed by face-to-face interview data collection techniques was used. To ascertain minimum dietary diversity, a 24 h food recall method comprising eight food item questionnaires was used. A statistical association was found between dependent and independent variables using the adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals and a p-value of ≤0.05.

Result: This study found that only 192 (47.6%) children aged 6–23-month old had adequate dietary diversity. In this study, variables such as maternal education [AOR 2.36, 95% CI (1.297, 3.957)], birth interval [AOR 2.85, 95% CI (1.45, 4.25)], and food insecurity [AOR = 2.23, 95% CI (1.626, 3.1)] were strongly significant variables for the minimum dietary diversity of the child.

Conclusion and recommendations: The proportion of the minimum dietary diversity was relatively low. Mother’s educational status, low birth intervals, and food insecurity were significant predictors of minimum dietary diversity. The stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health, regional health offices, and agricultural sectors, prioritize enhancing child nutrition through targeted food-based approaches. Developing and implementing comprehensive intervention programs to improve children’s minimum dietary diversity (MDD) should be a central focus. Professionals should strengthen nutrition education to promote optimal MDD practices.

Dietary diversity refers to a variety of food types that are frequently used to gauge the variety and nutrient sufficiency of diets (1). Increasing the variety of foods and food groups for a child can ensure the adequacy of essential nutrients (2, 3). Food categories from various diets are crucial for child-feeding techniques that meet their nutritional demands and promote healthy growth and development in infancy (4, 5). For a child to experience the best possible growth and development, proper feeding methods for infants and young children are essential (6). In addition, a lack of diversified foods puts children at a greater risk of not achieving their potential growth and development, dropping out of school, and failing classes, which has a significant negative impact on communities, families, and educational institutions (7, 8).

The first 2 years of a child’s life are crucial for their growth and development, making proper infant and young child-feeding (IYCF) practices essential (9–11). Inappropriate feeding during this period is linked to over half of the under-five child mortality cases (12). Adequate nutrition in these early years is vital not only for physical growth but also for mental development and long-term health (13).

To improve IYCF practice and address these critical needs, the WHO-UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group on Nutrition Monitoring (TEAM) has recommended revising the minimum dietary diversity (MDD) indicator (14, 15). They have developed a set of core indicators to better assess feeding practices for children aged 6–23 months, emphasizing both breastfeeding and complementary feeding. These indicators aim to ensure that children receive the necessary nutrients to reduce morbidity, mortality, and the risk of chronic diseases (16–19).

Minimum dietary diversity (MDD) measures the variety of foods or food groups ingested during a 24 h period (17). The WHO-UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group identified eight food groups that provide the necessary amount of macro- and micro-nutrients for children aged 6–23 months: breast milk, grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products; flesh foods (meats, fish, and poultry); eggs; vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables. Children aged 6 to 23 months are advised to eat at least five different food groups every day (4, 20).

Globally, only 28.2% of children aged 6–23 months achieve the recommended level of dietary diversity (21). This issue is exacerbated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in regions such as South Asia and parts of Africa (22). Despite efforts to improve dietary diversity, Ethiopia still reports the lowest level of adequate dietary diversity among East African countries (23, 24). In addition, stunting, underweight, and chronic diseases in children are closely linked to adequate dietary diversity (25). Children who are stunted, underweight, or with chronic diseases are less likely to meet dietary diversity requirements and are more susceptible to infections and illnesses (26). Evidence-based nutritional information, by providing scientifically proven guidelines and recommendations specifically targeted to the needs of various age groups, plays a critical role in enhancing infant and young child-feeding (IYCF) practices and reducing childhood malnutrition (27, 28). With this knowledge, common nutritional deficiencies can be correctly identified and addressed, feeding techniques can be suggested, and a varied, nutrient-rich diet can be encouraged (29, 30). It guarantees the knowledge of healthcare providers and caregivers, helps in the monitoring and assessment of nutrition treatments, and supports the creation of focused public health policies and programs (31). Evidence-based knowledge improves the efficacy of initiatives to address under-nutrition, over-nutrition, and associated health problems by firmly establishing nutrition recommendations in scientific research, eventually improving children’s health outcomes (32). The Ethiopian government has launched a multifaceted strategy to boost dietary diversity and improve child nutrition, centered on the National Nutrition Program (NNP), which promotes diverse food consumption and behavior change communication (33).

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of dietary diversity feeding practices and their determinants among children aged 6–23 months in the Awi Zone. The findings will inform nutritional education and counseling for mothers and caregivers about the importance of IYCF practice. In addition, this finding will provide insights for governmental and non-governmental intervention to address under-nutrition and mitigate its long-term impact.

The institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Awi Zone, Amhara Regional State, from two public hospitals from 1 August to 28 September 2023.

Awi Zone is one of the 11 zones in the Amhara Region. This zone includes three town administrations and nine rural woredas.

It is 439.4 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city, and 114 km away from Bahir Dar city, the capital city of the region, which is a well-productive and comfortable zone for agriculture. According to the information from the Zone Health Office, there are three public hospitals and many governmental and private health centers that provide health services for the community. The study was carried out in two selected public hospitals in the Awi Zone (Injibara and Dangila Hospitals), which serve the majority of the population in the Awi Zone.

Children aged 6–23 months paired with mothers/caregivers in the Awi Zone.

Children aged 6–23 months paired with mothers/caregivers who received health services in the selected hospital.

Children aged 6–23 months paired with mothers/caregivers who received health services during the data collection period in the selected study area.

Children aged 6–23 months paired with mothers/caregivers who were critically ill and unable to feed or children who were on tube feeding in the last 24 h.

The sample size was calculated by using the single population proportion formula. The proportion of dietary diversity practice was estimated to be 59.9% in a study conducted in Addis Ababa (34). Therefore, the sample size was determined using the following assumptions: proportion (p) 59.9%, margin of error (d) 5%, and Zα/21.96 with 95% CI.

By adding 10% non-response, which is 37, the final sample size was 406.

To contact study participants, a multistage sampling methodology that combined simple random and systematic random sampling methods was used. The sampling frame for the initial phase included all hospitals in the Awi Zone. A lottery method was used to choose Enjbara and Dangila hospitals. After that, the proportional allocation was used to divide the 406 people in the sample size evenly across the two hospitals that were chosen. All the study participants received comprehensive information regarding the goals and methods of the study. All participants gave their informed consent prior to involvement, confirming that they were aware of their rights, that their participation was voluntary, and that they may leave at any moment without incurring any fees; this procedure followed ethical guidelines.

Data were collected from mothers or caregivers who had children aged 6–23 months from each household by direct interviewing. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by a trained team using a structured guide and standardized procedures, with rigorous monitoring and supervision to ensure consistency and reliability. A per-tested, interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from child mothers/caregivers who had children aged 6–23 months of age. For this study, a validated dietary assessment tool was used to ensure the accurate and reliable measurement of dietary diversity. The tool was developed by the WHO-UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group on Nutrition Monitoring (TEAM) (19). Minimum dietary diversity/recommended dietary diversity was defined as consuming five or more food types or groups in the preceding day/24 h/ of the survey out of the eight standard food groups that were recommended by the WHO (35). The questionnaire was prepared in English, and for fieldwork purposes, the questionnaires were translated into the Amharic version and then translated back into the English version. The questionnaire contains four parts: socio-demographic characteristics, child and maternal health services utilization, household food security, and dietary diversity assessment tools. The MDDs were assessed by asking the child’s mother/caregiver whether the child consumed the WHO-recommended food group on the previous day of the survey. The data were collected by eight trained nurses and supervised by two supervisors.

The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated to the local language (Amharic version). Interviewers were trained on the aim of the research, the content of the questionnaire, and how to conduct interviews to increase their performance in field activities before data collection, and a pretest was conducted on 5% of child mothers/caregivers before actual data collection outside the selected rural kebeles. Two-day training was given for the data collectors, and the collected data were checked every day by the principal investigator.

After the completion of the data, the data were cleaned, coded, and entered into EpiData version 7, and then transformed to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Data analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software where adjusted odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated, and additional tests such as chi-square tests were conducted to assess the associations and ensure the robustness of the findings.

Multi-collinearity was assessed to check whether independent variables in a regression model are highly correlated with each other, and an effort was made to incorporate different models to cross-check.

The results of the study are presented in text, tables, and graphs. Frequency and cross-tabulation were calculated to describe the study population about relevant variables. A binary logistic regression was performed to select the variables for a multivariate analysis. A multi-variable logistic regression analysis was performed on the variables with a p-value <0.25. Before adjusting in the multi-variable analysis, the variable candidates for the multi-variable analysis were checked for multi-collinearity using the variance inflation factor, and the VIF was less than 10, which was acceptable. A multi-variable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the independent predictors of the minimum dietary diversity. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess the model’s fitness [0.124]. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval was used to measure the degree of association.

Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who receive five food groups from eight food groups during the previous days of data collection. The eight food groups used for tabulation of this indicator were grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese); flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meats); eggs; vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables. Children who consumed less than five food groups were considered to have inadequate dietary diversity.

Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who receive four and less than four food groups from eight food groups during the previous days of data collection.

Child’s dietary diversity.

Socio-demographic characteristics: child age, child sex, mother’s education, father’s education, mother’s occupation, father’s occupation, mother’s age, birth order, marital status, religion, income/wealth, food security, and parity.

Child characteristics: gender, birth order, gestational age at birth, feeding problem, duration of Breast Feeding, frequency of feeding, and duration of exclusive BF. Health-related factors: starting date of complementary feeding, birth interval, antenatal care, postnatal care, education on how to feed children, place of delivery, and education on how to feed children.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Science. Then, a permission letter was acquired from the College of Health Research Management Directorate for the Awi Zone Health Office, and the office wrote the letter for the selected public hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants. The participant’s strict confidentiality was ensured and their identity was not shown; there was no dissemination of the information without the respondent’s permission. The data given by the participants were used only for research purposes.

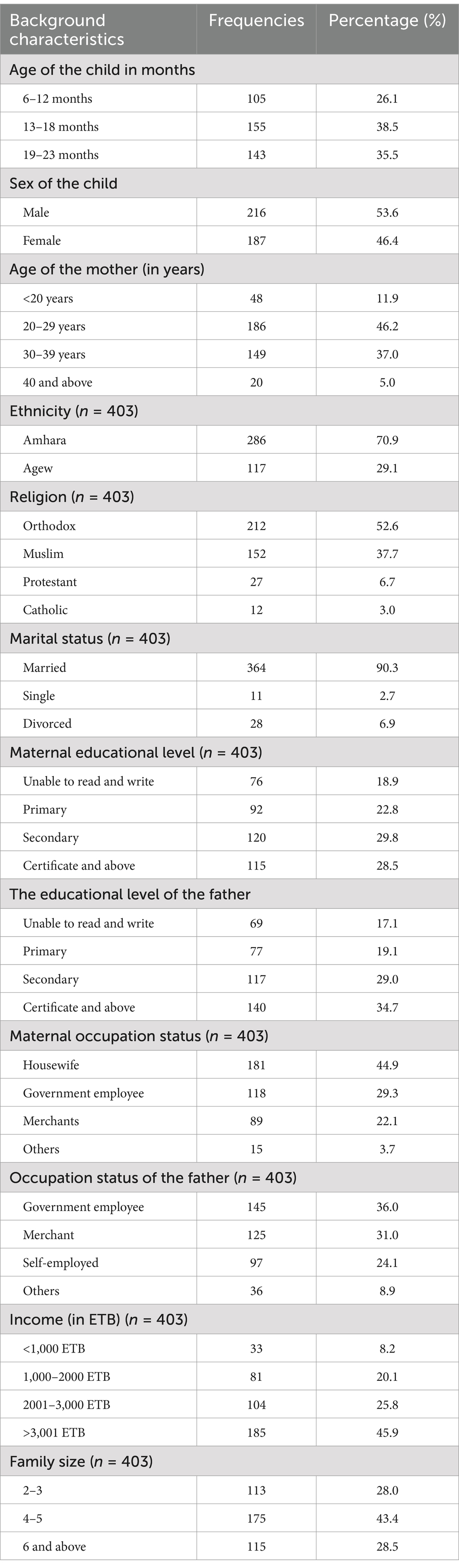

A total of 403 mothers with children aged 6–23 months were interviewed, achieving a response rate of 99.26% because recruitment efforts involved clear communication about the study’s purpose, ensuring informed consent, and adhering to rigorous standards to avoid conflicts of interest. Among the participants, 38.5% had children aged 13–18 months, and more than half (53.6%) of the children were male individuals. Regarding religious affiliation, 212 participants (52.6%) were Orthodox.

Educationally, 115 mothers (28.5%) had attained a certificate or higher, while 181 participants (44.9%) were housewives. In addition, 175 participants (43.4%) had families with 4–5 members, and 185 participants (45.9%) reported a monthly income greater than 3,001 ETB (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of children aged 6–23 months in Awi Zone, Ethiopia, 2023 (N = 403).

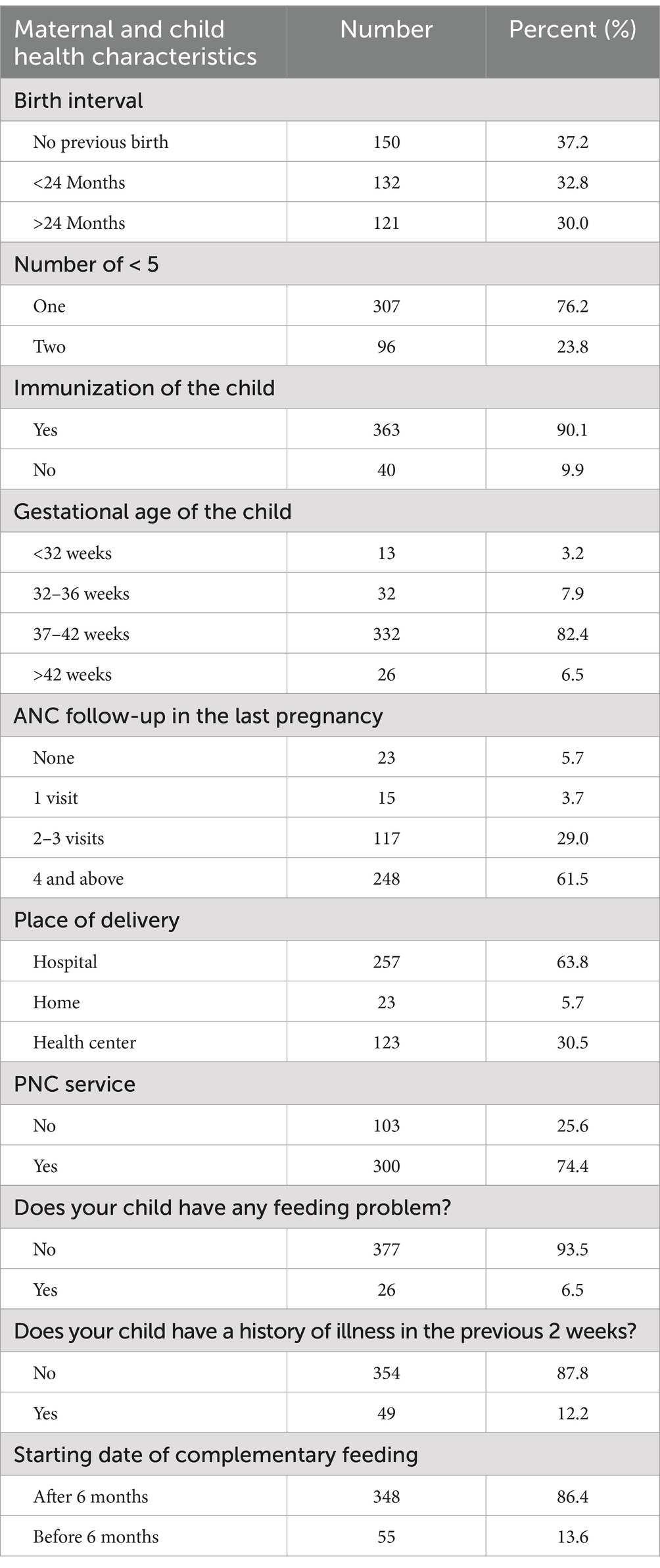

Of the total study participants, 121 (30%) had a birth interval greater than 24 months, and 96 (23.6%) lived in households with two children under 5 years. Of the total, 363 (90.1%) of children were fully immunized, and the majority (82.4%) of the children were full-term babies. Nearly two-thirds (61.5%) of the mothers had fourth visit antenatal care (ANC) follow-up, and almost all (94.3%) of mothers gave birth at the health facility. Three hundred (74.4%) mothers had postnatal care (PNC) follow-up. A small number (6.5%) of the children had a feeding problem, and only 49 (12.2%) children had a history of illness in the previous 2 weeks. The majority (86.4%) of the children started receiving complementary feeding after the age of 6 months (Table 2).

Table 2. Maternal and child health characteristics of children aged 6–23 months in Awi Zone, Ethiopia, 2023 (N = 403).

Of the total, 324 (80.4%) mothers breastfed their children. In addition, more than three-fourths of the mothers, 314 (77.9%), reported consuming dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese) in the previous 24 h. More than two-thirds of the children consumed grains, roots, and tubers, as well as eggs, within the same time frame. Similarly, two-thirds of the children consumed flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, liver, or other organs), while only one-third consumed legumes and nuts. Over three-quarters and two-thirds of the children did not consume vitamin A-rich foods (fruits and vegetables) and other fruits and vegetables, respectively, in the previous 24 h. Based on these categories, 197 (42.6%) children exhibited adequate dietary diversity (DD), defined as consuming five or more food groups, while the remaining 52.4% fell into the low DD category, consuming fewer than five food groups (Table 3).

As shown in Table 4, the food security status of households emerged as a crucial factor influencing the dietary diversity of children aged 6–23 months. Among the nine Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) items, a significant majority of households, 331 (82.1%), expressed concerns about running out of food. In addition, 322 (79.9%) households reported being unable to consume their preferred foods. Furthermore, 343 (85.1%) households were found to have a limited variety of food choices. More than half of the households resorted to eating food they did not prefer, and over a quarter skipped meals within the past 24 h. The overall prevalence of food insecurity was notable, with 334 (41.4%) households classified as food insecure (Table 4).

Table 5 shows bi-variable and multi-variable analysis of factors associated with MDDs of a child aged 6–23 months. In the binary logistic regression, only ten variables had a p-value less than 0.25, and multi-variable logistic regression was run for all these ten variables. In the multi-variable logistic analysis, only three variables (maternal education, birth interval, and food security) had scientifically significant factors for the outcome variables. In terms of maternal education status, mothers with a secondary education and above were 2.36 times [AOR 2.36, 95% CI (1.30, 3.96)] more likely to have adequate dietary diversity than those who were unable to read and write. On the other hand, birth interval was one significant variable that affected the minimum dietary diversity of the child. Mothers with birth intervals greater than 24 months were 2.85 times [AOR 2.85, 95% CI (1.45, 4.25)] more likely to practice adequate dietary diversity than those with birth intervals less than 24 months. Finally, food insecurity is also one scientifically significant factor that affects the minimum dietary diversity of the children. Food-secure households were 2.23 times more likely to practice adequate dietary diversity than households with food insecurity [AOR = 2.23, 95% CI (1.63, 3.10)] times more likely to feed diversified food to their children than their counterparts (Table 5).

The aim of this study was to assess the dietary diversity of children aged 6–23 months and identify associated factors that influence dietary diversity. Adequate dietary diversity for children aged 6–23 months is crucial for maintaining optimal health and promoting normal growth and development. Various factors influence the DDs of children, and this causes health problems and affects the growth and development of the child. According to the essential nutrition action (ENA), existing studies recommended that adequate dietary diversity during this age group was very crucial for normal growth and development (36).

In this finding, 192 (47.6%) children aged 6–23 had adequate dietary diversity, which is higher than that observed in a study conducted in Northwest Ethiopia (18.2%), the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016 (12.09%), Southern Ethiopia (10.6%), Chelia District, Ethiopia (17.32%), Gedeo Zone, Ethiopia (29.9%), East Africa (10.47%), and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (25.1%) (2, 6, 37–40). Several factors may contribute to this variation in findings.

The potential cause might be variations in sample size, and the study design can influence the results; for example, larger sample sizes or different methodologies might yield different outcomes.

The approach to measuring dietary diversity, including the accuracy of self-reported data and recall periods, agricultural practices, such as local crop availability and farming techniques, environmental factors, including regional climate and economic conditions, cultural dietary practices, and socio-economic conditions, plays a role in determining dietary patterns. Understanding these factors can provide context for the observed differences and underscore the importance of considering local conditions when interpreting dietary diversity in the 24 h during the survey.

Similarly, this discrepancy may be attributed to differences in measurement of DDs, the category of food group, and the study setting, i.e., some studies use seven food groups, and if four food groups were consumed from the seven, they classified as adequate dietary diversity; however in our study, we used eight food groups, and we classified them as adequate dietary diversity if they consumed five from eight food groups.

The results of this finding are almost consistent with the those of a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (34), Southern Ethiopia (41), Bale Zone, Southern Ethiopia (42), Haramaya, Ethiopia (43), Northwest Ethiopia (44), and Bangladesh (34). The similarity of the findings across the studies may be attributed to the fact that the majority of these studies were conducted in Ethiopia. This shared geographical and cultural context likely results in similar socio-demographic, socio-economic, and seasonal variations, which can influence dietary diversity in comparable ways.

The common socio-economic conditions, agricultural practices, and seasonal availability of food in Ethiopia contribute to the observed similarities in dietary diversity rates.

On the other hand, the finding of this study is lower as compared with another study that is done in Indonesia (Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey) (53·1%) in 2007, (51·7%) in 2012, and (53·7%) in 2017 (45). This might be explained by the difference in the study period, which can result in food security status change, as well as socio-demographic, socio-cultural, and geographical variations.

The study results might vary due to differences in self-reported measurement and recalling food given in the 24 h before the survey. In addition, information accessible area, time of the study, and related socio-economic characteristics could also affect the estimated minimum dietary diversity score.

In our study, the mother’s educational status was one significant variable for the MDDs of the child. Mothers with a secondary education and above were two times more likely to have good dietary diversity for their children as compared to those with less than secondary education.

Similarly, the study in Chelia District, Ethiopia (6), the study in Gorche District, Southern Ethiopia (46), the study in Indonesia (45), the study in East Africa (40), and the study in Wolaita Sodo, Southern Ethiopia, showed that illiterate mothers were less likely to feed their children to fulfill the minimum requirement of dietary diversity of food for their children. This might be a lack of understanding and knowledge of the importance of MDDs for the normal health and both growth and development of the child.

In this finding, birth interval is one pertinent and significant predictor of normal MDDs of a child aged 6–23 months. Mothers with birth intervals greater than 24 months were three times more likely to practice good dietary diversity than those mothers with birth intervals less than 24 months{{Mekonnen et al. (47) #8}Sema et al. (20) #7{Anane et al. (48) #4}}.

In general, the optimal breastfeeding is 2 years, and if there is a birth of fewer than 2 years, then the first baby does not get adequate parental care including MDDs; in this age group, the parent will give their attention to the new baby. In addition, the mothers have no time to give adequate care for their two little children (49), and that may challenge their economy as well as they may have fewer chances of meeting nutrient requirements for the child for feeding the child based on the recommendations (20, 50). Mothers who had food insecurity were 2.23 times more likely to have adequate dietary diversity for their children as compared to their counterparts. Similarly, in a study in Mali, Gorche District, Southern Ethiopia, EDHS, 2016, and Debub Bench Zone, women from extremely food-insecure households were less likely to practice good MDDs for their children (46, 51–54). When women have food security, they become more concerned with adequate dietary diversity (MDDs) and immediately can put them into practice. This is supported by a study conducted in Boston; food insecurity may worsen diet quality and diversity (45, 54, 55).

The study revealed that nearly half of the participants fail to meet the minimum dietary diversity (MDD) standards recommended by the WHO-UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group. This underscores the urgent need for intervention to address the prevalent issue of inadequate MDDs among children. Factors such as maternal educational level, short birth intervals, and household food insecurity emerged as significant predictors of insufficient MDDs in this research. The findings can inform public health policy and practice by guiding targeted local interventions, shaping national regulations, adjusting funding priorities, and updating evidence-based guidelines, thus enhancing both immediate and long-term health outcomes.

We recommended that stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health, regional health offices, and agricultural sectors, prioritize the enhancement of child nutrition through targeted food-based approaches. Developing and implementing comprehensive intervention programs to improve children’s minimum dietary diversity (MDD) should be a central focus. Health professionals should strengthen nutritional education to promote adequate dietary diversity (MDD) practices. This effort should not rest solely on government bodies but must involve collaboration across all relevant sectors, including the Ministry of Education, healthcare providers, community organizations, and every household. Such a multi-faceted approach is essential to effectively improving nutritional outcomes for children aged 6–23 months. In addition, health personnel should be actively engaged in family planning and educating families on the importance of MDD for child health.

The strength of the study was the use of standardized and validated measurement tools, which enhanced the accuracy and reliability of the DD data. In addition, the provision of training to the data collectors ensures that data collection is consistent and high-quality. Despite having a representative sample, the cross-sectional design limits the study’s ability to establish causality or track changes over time. Furthermore, recall bias may affect the accuracy of reported dietary practices and predictors as participants may not always accurately remember or report their dietary behaviors.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics approval and consent to participate the formal letter was obtained from the Ethical committee of the College of Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University with the protocol number 280/2023. Official letters at different levels including Awi zone administrative office and selected Households were communicated through formal letters. We apply written informed consent for the participants about the purpose and objective of the study. Respondents were also being told the right not to respond to the questions if they do not want to respond or to terminate the interview at any time and verbal consent was obtained from each study participant. Confidentiality of the information was assured and privacy was also maintained. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LE: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. HD: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FT: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. AG: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FS: Writing – review & editing. HW: Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ruel, MT. Operationalizing dietary diversity: a review of measurement issues and research priorities. J Nutr. (2003) 133:3911S–26S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3911S

2. Aboagye, RG, Seidu, A-A, Ahinkorah, BO, Arthur-Holmes, F, Cadri, A, Dadzie, LK, et al. Dietary diversity and undernutrition in children aged 6–23 months in sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3431. doi: 10.3390/nu13103431

3. Steyn, NP, Nel, JH, Nantel, G, Kennedy, G, and Labadarios, D. Food variety and dietary diversity scores in children: are they good indicators of dietary adequacy? Public Health Nutr. (2006) 9:644–50. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005912

4. Arimond, M, and Ruel, MT. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. J Nutr. (2004) 134:2579–85. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2579

5. Taghizade Moghaddam, H, Khodaee, GH, Ajilian Abbasi, M, and Saeidi, M. Infant and young child feeding: a key area to improve child health. Int J Pediatr. (2015) 3:1083–92.

6. Keno, S, Bikila, H, Shibiru, T, and Etafa, W. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6 to 23 months in Chelia District, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. (2021) 21:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-03040-0

7. Hyde, KA, and Kabiru, MN. Early childhood development as an important strategy to improve learning outcomes ADEA (2006). Association for the Development of Education in Africa.

8. Tontisirin, K, Nantel, G, and Bhattacharjee, L. Food-based strategies to meet the challenges of micronutrient malnutrition in the developing world. Proc Nutr Soc. (2002) 61:243–50. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002155

9. Yonas, F, Asnakew, M, Wondafrash, M, and Abdulahi, M. Infant and young child feeding practice status and associated factors among mothers of under 24-month-old children in Shashemene Woreda, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Open Access Libr J. (2015) 2:1–15. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1101635

10. Roba, KT, O’Connor, TP, Belachew, T, and O’Brien, NM. Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices among mothers of children aged 6–23 months in two agro-ecological zones of rural Ethiopia. Int J Nutr Food Sci. (2016) 5:185–94. doi: 10.11648/j.ijnfs.20160503.16

11. Franz, MJ, Bantle, JP, Beebe, CA, Brunzell, JD, Chiasson, J-L, Garg, A, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. (2002) 25:148–98. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.148

12. Picciano, MF, Smiciklas-Wright, H, Birch, LL, Mitchell, DC, Murray-Kolb, L, and McConahy, KL. Nutritional guidance is needed during dietary transition in early childhood. Pediatrics. (2000) 106:109–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.109

13. World Health Organization. Guiding principles for feeding non-breastfed children 6-24 months of age. World Health Organization (2005).

14. Black, RE, Victora, CG, Walker, SP, Bhutta, ZA, Christian, P, De Onis, M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. (2013) 382:427–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X

15. Roy, A, Hossain, MM, Hanif, AAM, Khan, MSA, Hasan, M, Hossaine, M, et al. Prevalence of infant and young child feeding practices and differences in estimates of minimum dietary diversity using 2008 and 2021 definitions: evidence from Bangladesh. Curr Dev Nutr. (2022) 6:nzac026. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac026

16. World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: part 2: measurement. World Health Organization (2010).

17. Nti, CA. Dietary diversity is associated with nutrient intakes and nutritional status of children in Ghana. Asian J Med Sci. (2011) 2:105–9. doi: 10.3126/ajms.v2i2.4179

18. World Health Organization. Methodology for monitoring progress towards the global nutrition targets for 2025: technical report. World Health Organization (2017).

19. World Health Organization. Report of the technical consultation on measuring healthy diets: concepts, methods and metrics Virtual Meeting World Health Organization (2021).

20. Sema, A, Belay, Y, Solomon, Y, Desalew, A, Misganaw, A, Menberu, T, et al. Minimum dietary diversity practice and associated factors among children aged 6 to 23 months in Dire Dawa City, eastern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Glob Pediatr Health. (2021) 8:2333794X21996630. doi: 10.1177/2333794X21996630

21. Maundu, J. Assessment of feeding practices and the nutritional status of children aged 0–36 months in Yatta division. Kitui district: University of Nairobi (2007).

22. Islam, MH, Nayan, MM, Jubayer, A, and Amin, MR. A review of the dietary diversity and micronutrient adequacy among the women of reproductive age in low-and middle-income countries. Food Sci Nutr. (2024) 12:1367–79. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3855

23. Anin, SK, Saaka, M, Fischer, F, and Kraemer, A. Association between infant and young child feeding (IYCF) indicators and the nutritional status of children (6–23 months) in northern Ghana. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2565. doi: 10.3390/nu12092565

24. Isabirye, N, Bukenya, JN, Nakafeero, M, Ssekamatte, T, Guwatudde, D, and Fawzi, W. Dietary diversity and associated factors among adolescents in eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08669-7

25. Gassara, G, and Chen, J. Household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and stunting in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4401. doi: 10.3390/nu13124401

26. Harper, A, Goudge, J, Chirwa, E, Rothberg, A, Sambu, W, and Mall, S. Dietary diversity, food insecurity and the double burden of malnutrition among children, adolescents and adults in South Africa: findings from a national survey. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:948090. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.948090

27. Bhutta, ZA, Das, JK, Rizvi, A, Gaffey, MF, Walker, N, Horton, S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. (2013) 382:452–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4

28. American Diabetes Association. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. (2002) 25:s50–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2007.S50

29. Graham, RD, Welch, RM, and Bouis, HE. Addressing micronutrient malnutrition through enhancing the nutritional quality of staple foods: principles, perspectives and knowledge gaps. (2001).

30. Bruins, MJ, Bird, JK, Aebischer, CP, and Eggersdorfer, M. Considerations for secondary prevention of nutritional deficiencies in high-risk groups in high-income countries. Nutrients. (2018) 10:47. doi: 10.3390/nu10010047

31. Pelletier, D, Corsi, A, Hoey, L, Faillace, S, and Houston, R. The program assessment guide: an approach for structuring contextual knowledge and experience to improve the design, delivery, and effectiveness of nutrition interventions. J Nutr. (2011) 141:2084–91. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.134916

32. Disha, A, Rawat, R, Subandoro, A, and Menon, P. Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices in Ethiopia and Zambia and their association with child nutrition: analysis of demographic and health survey data. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. (2012) 12:5895–914. doi: 10.18697/ajfand.50.11320

33. Teshale, G, Debie, A, Dellie, E, and Gebremedhin, T. Evaluation of the outpatient therapeutic program for severe acute malnourished children aged 6–59 months implementation in Dehana District, northern Ethiopia: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMC Pediatr. (2022) 22:374. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03417-9

34. Solomon, D, Aderaw, Z, and Tegegne, TK. Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0680-1

35. Sirasa, F, Mitchell, L, and Harris, N. Dietary diversity and food intake of urban preschool children in North-Western Sri Lanka. Matern Child Nutr. (2020) 16:e13006. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13006

36. Gonete, KA, Tariku, A, Wami, SD, and Akalu, TY. Dietary diversity practice and associated factors among adolescent girls in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017. Public Health Rev. (2020) 41:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00137-2

37. Assefa, D, and Belachew, T. Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6-23 months in Enebsie Sar Midir Woreda, east Gojjam, north West Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. (2022) 8:149. doi: 10.1186/s40795-022-00644-2

38. Sisay, BG, Afework, T, Jima, BR, Gebru, NW, Zebene, A, and Hassen, HY. Dietary diversity and its determinants among children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2016 demographic and health survey. J Nutr Sci. (2022) 11:e88. doi: 10.1017/jns.2022.87

39. Molla, W, Adem, DA, Tilahun, R, Shumye, S, Kabthymer, RH, Kebede, D, et al. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children (6–23 months) in Gedeo zone, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Ital J Pediatr. (2021) 47:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13052-021-01181-7

40. Raru, TB, Merga, BT, Mulatu, G, Deressa, A, Birhanu, A, Negash, B, et al. Minimum dietary diversity among children aged 6–59 months in East Africa countries: a multilevel analysis. Int J Public Health. (2023) 68:1605807. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605807

41. Gari, T, Loha, E, Deressa, W, Solomon, T, and Lindtjørn, B. Malaria increased the risk of stunting and wasting among young children in Ethiopia: results of a cohort study. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0190983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190983

42. Yuliastini, S, Sudiarti, T, and Sartika, RAD. Factors related to stunting among children age 6–59 months in babakan Madang sub-district, West Java, Indonesia. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. (2020) 8:454–61. doi: 10.12944/CRNFSJ.8.2.10

43. Liben, ML, Abuhay, T, and Haile, Y. The role of colostrum feeding on the nutritional status of preschool children in Afambo District, Northeast Ethiopia: descriptive cross sectional study. Eur J Clin Biomed Sci. (2016) 2:87–91. doi: 10.11648/j.ejcbs.20160206.15

44. Batiro, B, Demissie, T, Halala, Y, and Anjulo, AA. Determinants of stunting among children aged 6–59 months at Kindo Didaye woreda, Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia: unmatched case control study. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0189106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189106

45. Paramashanti, BA, Huda, TM, Alam, A, and Dibley, MJ. Trends and determinants of minimum dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months: a pooled analysis of Indonesia demographic and health surveys from 2007 to 2017. Public Health Nutr. (2022) 25:1956–67. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021004559

46. Dangura, D, and Gebremedhin, S. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children 6–23 months of age in Gorche district, southern Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. (2017) 17:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0764-x

47. Mekonnen, TC, Workie, SB, Yimer, TM, and Mersha, WF. Meal frequency and dietary diversity feeding practices among children 6–23 months of age in Wolaita Sodo town, southern Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. (2017) 36:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0097-x

48. Anane, I, Nie, F, and Huang, J. Socioeconomic and geographic pattern of food consumption and dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months old in Ghana. Nutrients. (2021) 13:603. doi: 10.3390/nu13020603

49. Cruise, S, and O’Reilly, D. The influence of parents, older siblings, and non-parental care on infant development at nine months of age. Infant Behav Dev. (2014) 37:546–55. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.06.005

50. Woldegebriel, AG, Desta, AA, Gebreegziabiher, G, Berhe, AA, Ajemu, KF, and Woldearegay, TW. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6-59 months in Ethiopia: analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016 (EDHS 2016). Int J Pediatr. (2020) 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2020/3040845

51. Adubra, L, Savy, M, Fortin, S, Kameli, Y, Kodjo, NE, Fainke, K, et al. The minimum dietary diversity for women of reproductive age (MDD-W) indicator is related to household food insecurity and farm production diversity: evidence from rural Mali. Curr Dev Nutr. (2019) 3:nzz002. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz002

52. Beyene, M, Worku, AG, and Wassie, MM. Dietary diversity, meal frequency and associated factors among infant and young children in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2333-x

53. Kabir, I, Khanam, M, Agho, KE, Mihrshahi, S, Dibley, MJ, and Roy, SK. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in infant and young children in Bangladesh: secondary data analysis of demographic health survey 2007. Matern Child Nutr. (2012) 8:11–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00379.x

54. Eshete, T, Kumera, G, Bazezew, Y, Mihretie, A, and Marie, T. Determinants of inadequate minimum dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia: secondary data analysis from Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016. Agric Food Secur. (2018) 7:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40066-018-0219-8

55. Hoddinott, J, and Yohannes, Y. Dietary diversity as a food security indicator. Washington, D.C (2002).

Keywords: children, dietary diversity, dietary practice, minimum dietary diversity, Ethiopia

Citation: Mulatu S, Ejigu LJ, Dinku H, Tadesse F, Gedif A, Salah F and Workie HM (2024) Dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months attending a public health hospital in Awi zone, Ethiopia, 2023. Front. Nutr. 11:1474995. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1474995

Received: 02 August 2024; Accepted: 02 December 2024;

Published: 20 December 2024.

Edited by:

Lemma Getacher, Debre Berhan University, EthiopiaReviewed by:

Gael Janine Mearns, Auckland University of Technology, New ZealandCopyright © 2024 Mulatu, Ejigu, Dinku, Tadesse, Gedif, Salah and Workie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sileshi Mulatu, c2lsc2hpbXVsYXR1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; U2lsZXNoLm11bGF0dUBiZHUuZWR1LmV0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.