- 1Alive & Thrive, FHI 360, New Delhi, India

- 2Alive & Thrive, FHI 360 Global Nutrition, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 3Jeevika, Bihar State Livelihood Promotion Society, Patna, Bihar, India

- 4Project Concern International, New Delhi, India

- 5Community Nutrition and Health Activity, CARE, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 6Alive & Thrive, FHI 360 Global Nutrition, Manila, Philippines

- 7Alive & Thrive, FHI 360, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 8Alive & Thrive, FHI 360 Global Nutrition, Washington, DC, United States

Introduction: Self-help groups (SHGs) and Support Groups (SGs) are increasingly recognized as effective mechanisms for improving maternal and young child nutrition due to their decentralized, community-based structures. While numerous studies have evaluated the outcomes and impact of SHGs and SGs on nutrition practices, there remains a gap in the literature. To address this, we conducted a literature review to examine the role of SHGs and SGs in improving health and nutrition outcomes, focusing on marginalized women, especially pregnant and lactating women (PLW), in India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, with an emphasis on programs supported by the international non-governmental initiative, Alive & Thrive.

Methods and materials: We conducted a literature review to assess various models, summarizing findings from 34 documents, including research studies, evaluation reports, program materials, strategies, annual reports, work plans, and toolkits. Relevant information from these documents was extracted using predetermined forms.

Results: In India, the models used SHGs with 10–20 women, federated into larger village and district organizations. Bangladesh and Vietnam SGs have similar structures but with local leaders and committees playing key roles. In all three countries, interventions aimed to improve health and nutrition practices through social behavior change (SBC) interventions, including peer-to-peer learning, interpersonal communication, home visits, and community meetings. Outcomes of the interventions showed that SHG members had increased knowledge of breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and improved dietary diversity compared to non-SHG participants. Interventions helped improve infant and young child feeding practices. Common challenges included sustaining the SHGs, ensuring adequate participation, socio-cultural barriers, and logistical difficulties in reaching PLW in remote areas. Limited time for health topics during SHG meetings and the dissolution of older SHGs were also significant issues.

Conclusion: SHG and SG models demonstrate success in improving health and nutrition outcomes but face challenges in scale, sustainability, and participation. Integrating nutrition-focused SBC interventions into SHGs and SGs requires significant capacity building for technical and counseling skills. Ensuring comprehensive coverage and robust quality assessment during community-based rollouts is essential. To sustain these interventions, it is crucial to prevent group dissolution, allow time for maturation, and secure strong stakeholder engagement and political support.

1 Introduction

The intergenerational effects and socio-economic costs of undernutrition are well known (1–5). Undernourished women face higher risks of mortality and conditions like anemia, which negatively impact future generations (6, 7). Poor diets, disease, food insecurity, inadequate care, and socio-cultural factors are key causes of undernutrition (8, 9). Women in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in Asia, often face inadequate dietary diversity and low food consumption (10–13). Their diets, especially in low-income settings, are largely based on starches, lacking in nutrient-rich foods (14, 15).

Undernourished children under five face higher risks of disease, lower cognitive ability, and reduced productivity as adults. Children in LMICs in Asia suffer from poor dietary diversity and suboptimal breastfeeding, leading to growth faltering and stunting (16–21). While breastfeeding rates have improved in Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam, early initiation of breastfeeding remains low (22). Various factors like income, education, gender norms, and exposure to nutrition counseling influence breastfeeding practices and overall diet quality for women and children (8, 23–29).

Household behaviors like food distribution, eating preferences, hygiene, education, lack of safe drinking water and health service uptake also contribute to undernutrition (30–35). Social behavior change (SBC) interventions have shown positive results in addressing these issues by influencing behaviors at household, community, and policy levels (31–35). Governments and partners are focusing on strengthening community outreach and capacity building to address these behavioral causes (36–39).

Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Support Groups (SGs) have emerged as platforms for socio-economic empowerment in low-income communities, especially among women (40–43). There is increasing evidence of their potential to improve health and nutrition outcomes, particularly maternal and infant nutrition (44–49). This paper synthesizes information from models integrating SBC into SHGs and SGs in India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, focusing on the design, platforms, and challenges.

In India, Jeevika, started by the Bihar government with support from the World Bank in 2006, evolved to include health and nutrition interventions. Rajiv Gandhi Mahila Vikas Pariyojana (RGMVP) in Uttar Pradesh, launched in 2012, also integrated nutrition into its women's empowerment program. Both the programs were initially meant to link SHGs with financial institutions and eventually evolved to include SBC interventions on health and nutrition. In Bangladesh, the Livelihood Improvement of Urban Poor Communities Project (LIUPCP), implemented from 2017 to 2022, organized poor urban communities to address climate resilience and livelihoods along with health and nutrition. Vietnam's Infant Young Child Feeding (IYCF) SG model, developed by Alive & Thrive from 2011 to 2014, focused on reaching ethnic communities in remote areas with maternal and child nutrition information.

While numerous studies have evaluated the outcomes and impact of SHGs and SGs on nutrition practices, there is a lack of comprehensive reviews examining their role in improving health and nutrition outcomes for marginalized women in Asia. To fill in the literature gap, we conducted this literature review to examine the role of SHGs and SGs in improving health and nutrition outcomes, focusing on marginalized women, especially pregnant and lactating women (PLW), in India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, with an emphasis on programs supported by a non-governmental initiative, Alive & Thrive.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Selection of models

The criteria for the selection of models for this review included: (a) implemented in South or Southeast Asia; (b) integrated nutrition services with SHGs or SGs; (c) use of SBC interventions targeting improvement in maternal and child nutrition; (d) involvement of Alive & Thrive either as a technical partner, implementor, or supporting the development partners or governments in any capacity. We have not published any review protocol for this study.

2.2 Literature selection

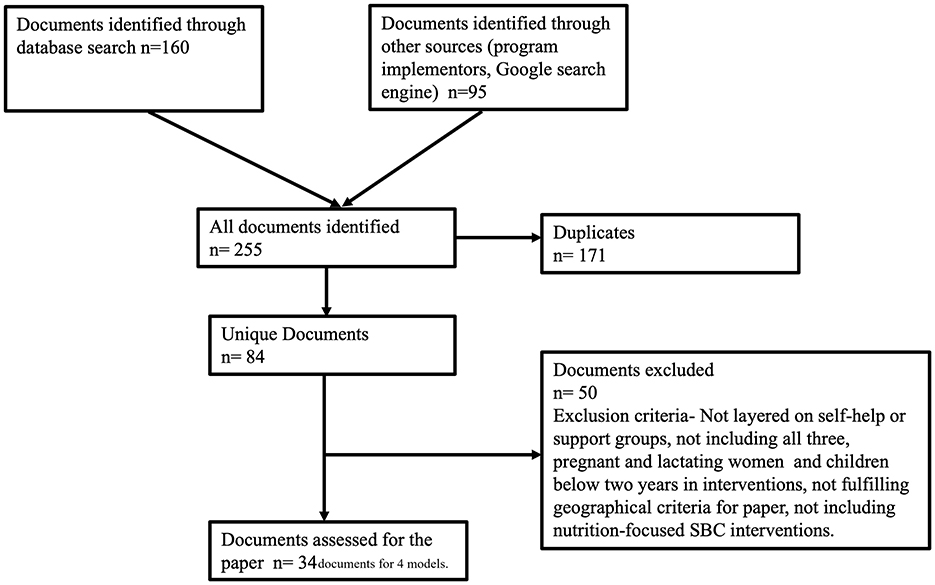

We reviewed the literature to extract information on the selected models and understand how SBC interventions were integrated into the SHGs and SGs. Based on the researchers' language proficiency, we limited our search to English-language documents. The documents included research studies, evaluation reports, program materials, strategies, annual reports, work plans, and toolkits. We placed no restrictions on the publication year. We searched for documents and conducted literature review using three different methods denoted by PRISMA (Figure 1). These included a database search (PUBMED) to select studies on the models using specific key phrases, gathering program materials solicited through program implementors and technical partners, and undertaking a keyword search using Google's search engine to access gray literature and online program materials relevant to the models. We used the same keywords to search through the database and search engine to maintain consistency. We chose the keywords based on the topic, context and models (as defined by the selection criteria). The abstracts obtained through PUBMED were reviewed and selected for further review. The selected literature underwent another round of assessment against the mentioned criteria for a final selection. The documents collected through means other than database search was also assessed for relevance before being admitted for full-length review. The search keywords included following phrases “SHGs in LMICs,” “Health and nutrition integration with SHGs,” Self-Help Groups in India,” “Self-Help Groups in Bangladesh,” “Support Groups in Vietnam,” “Support Groups for IYCF,” “Jeevika,” Rajiv Gandhi Vikas Pariyojana,” “Livelihood improvement for urban poor communities in Bangladesh,” “Support Group Models for Nutrition,” “Nutrition social and behavior change.”

2.3 Data items, charting process and synthesis

The whole team discussed the development of key contents for the information extraction forms. The extraction forms include information on methods, platforms, contents, and stakeholders for the Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBC) interventions; program coverage, targeting, and delivery metrics for the training of facilitators who delivered the interventions; framework for integrated program implementation and support; and intervention outcomes.

The lead author extracted information from the selected materials using the defined checklists. Results from the extraction were summarized in tables. The tables, figures, and results were circulated to all authors for review to ensure completeness and accuracy before finalization.

Synthesis of findings were drafted and finalized based on the discussion among all authors.

3 Results

Starting with 255 identified documents (Figure 1), the lead author reviewed and excluded 171 due to duplication, and an additional 50 because they did not focus on SHGs or SGs, targeted different groups, did not include SBC interventions, or were from regions outside Asia. The list then was circulated to other co-authors to check for completeness. The documents included for synthesis were research studies in peer-reviewed journals and on other platforms (n = 9), evaluations and outcome studies (n = 5), and program materials such as program briefs and outcome documents (n = 5), strategies (n = 4), work plans (n = 2), annual reports (n = 5), and toolkits (n = 4).

3.1 Structure and evolution of SHGs and SGs

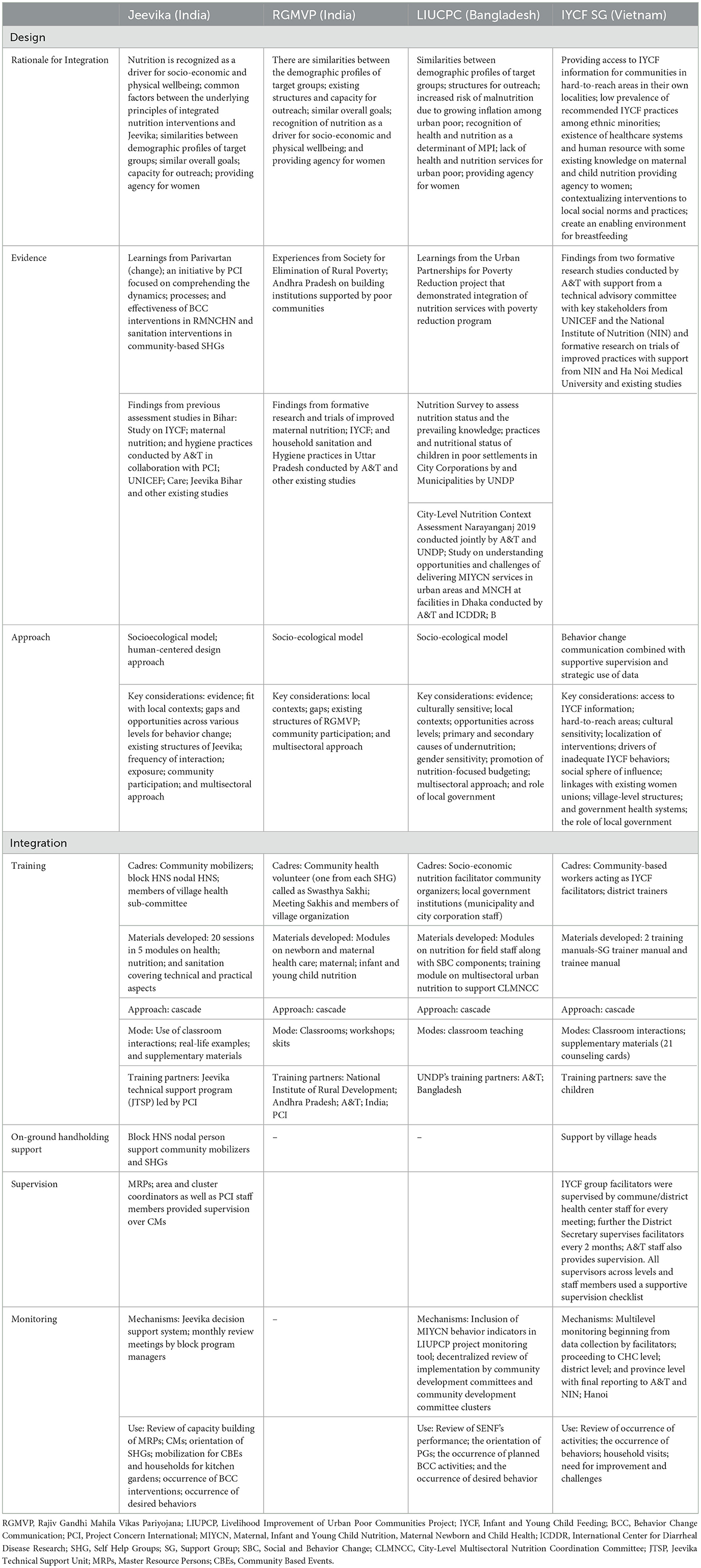

Table 1 shows that Jeevika's structure includes SHGs with 10–12 members from poor, marginalized households, federated into village organizations and larger clusters. SHGs focus on financial savings, intra-group lending, and linking with banks (50). In 2016, Jeevika reached over seven million households, expanding to more than 10 million (51). Health and nutrition interventions were introduced in 2013, supported by community mobilizers who facilitated SHG meetings and health-related activities. Dedicated nutrition resource persons and Master Resource Persons provided capacity building at the village level, with district-level managers overseeing health, nutrition, and sanitation programs (52).

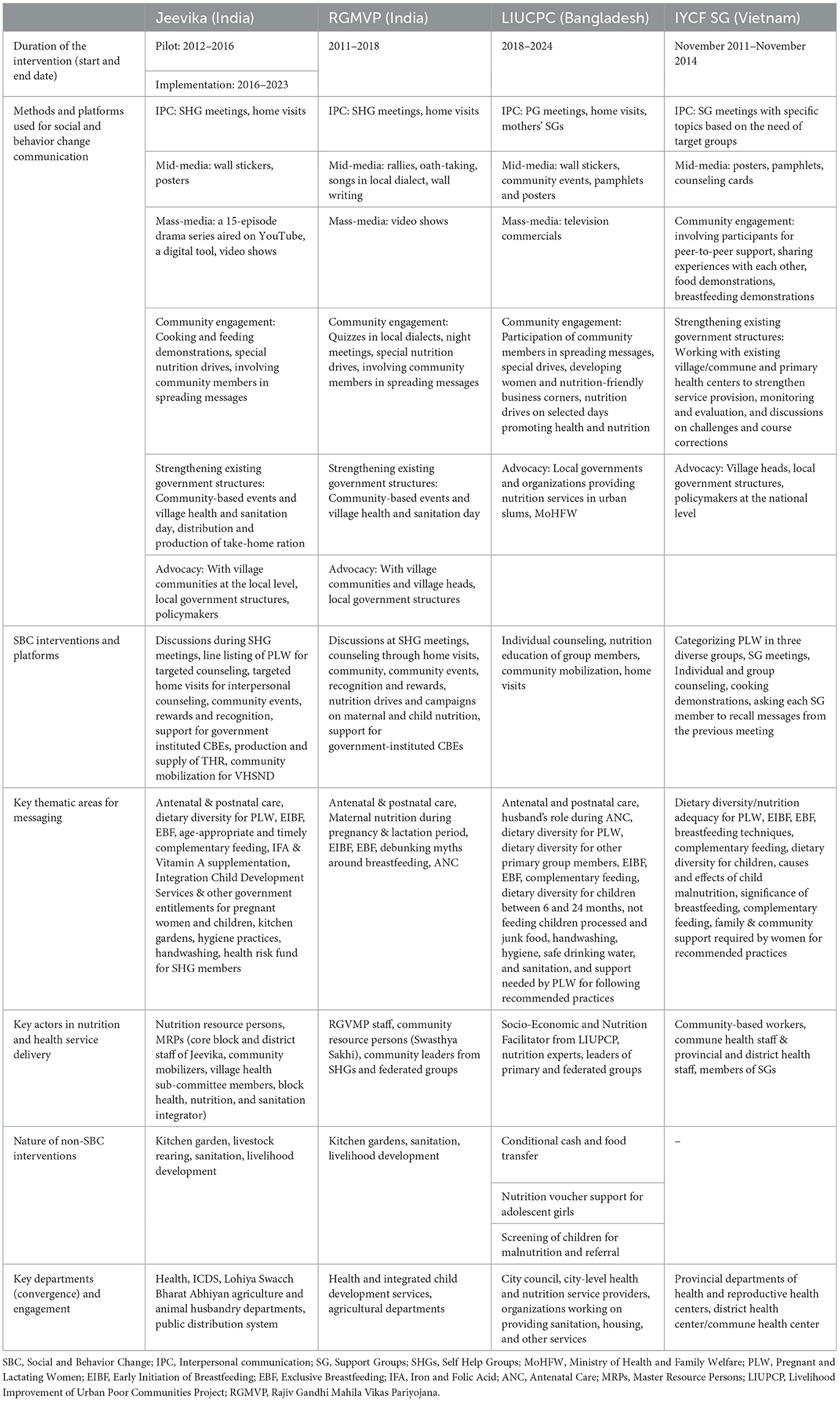

Table 1. Methods and platforms used for social and behavior change communication (SBC) interventions.

RGMVP SHGs also followed a community-centric approach, comprising 10–20 women from marginalized groups. The women were trained for 6 months and then federated into larger organizations. RGMVP focused on socio-economic empowerment through financial inclusion, banking, livelihood, and health services. Nutrition services were introduced through trained mobilizers, with additional focus on maternal and child nutrition (Table 1).

In Bangladesh, the LIUPCP model features three levels of structure. Primary groups of 15–20 members, mostly women, form community development committees, which are further grouped into clusters. These committees focus on nutrition discussions led by designated facilitators (Table 1).

Vietnam's IYCF SG model differs by drawing members from existing village structures. Facilitators, including village health workers and Women's Union members, lead groups focused on breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and community support, targeting pregnant women, mothers, and caregivers in rural areas.

3.2 Design of nutrition and health-specific SBC interventions

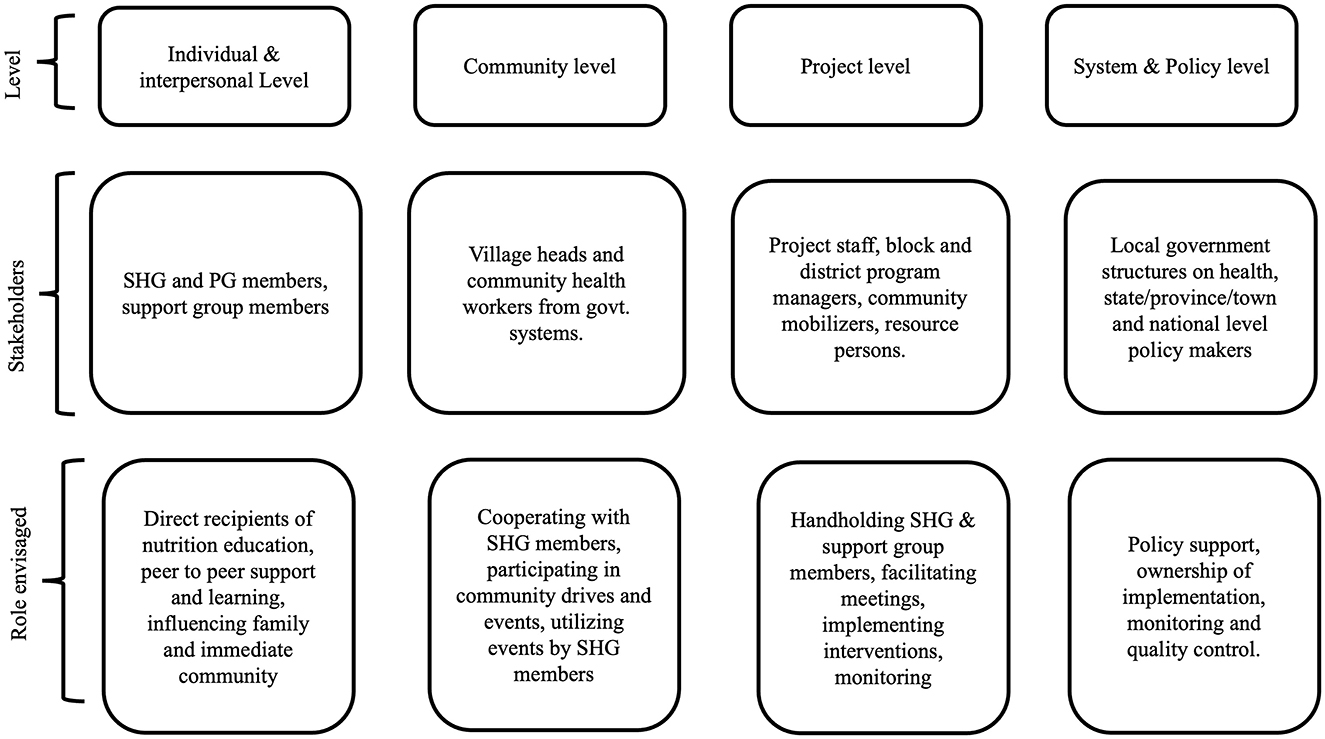

Table 1 also shows that the SBC interventions targeted pregnant women, mothers of children up to 23 months, families, and caregivers. All four models undertook a stakeholder mapping exercise and designed the SBC interventions around the individual, community, program, and policy levels (Figure 2). The three SHG models used a mix of interpersonal communication (IPC), mass media, mid-media, and digital approaches, while the IYCF SG model relied mainly on IPC and on-site demonstrations, using tools like counseling cards and mother-child booklets. SHG contact points included home visits, community events, and nutrition drives, while IYCF SGs focused on village meetings (Table 1).

Coordination with government departments was essential across the SHG and SG models, incorporating SBC, non-SBC nutrition, and nutrition-sensitive interventions. Common methods included storytelling, cooking demonstrations, and peer-to-peer support (Table 1).

Jeevika introduced innovative tools like Samvad Kunji, a digital media tool with QR codes, and food group stickers to monitor dietary diversity. RGMVP used visual maps to help women visualize concerns and plan actions (Table 1). Both programs aimed to shift social norms around maternal nutrition, involving families and communities in the process (53–58).

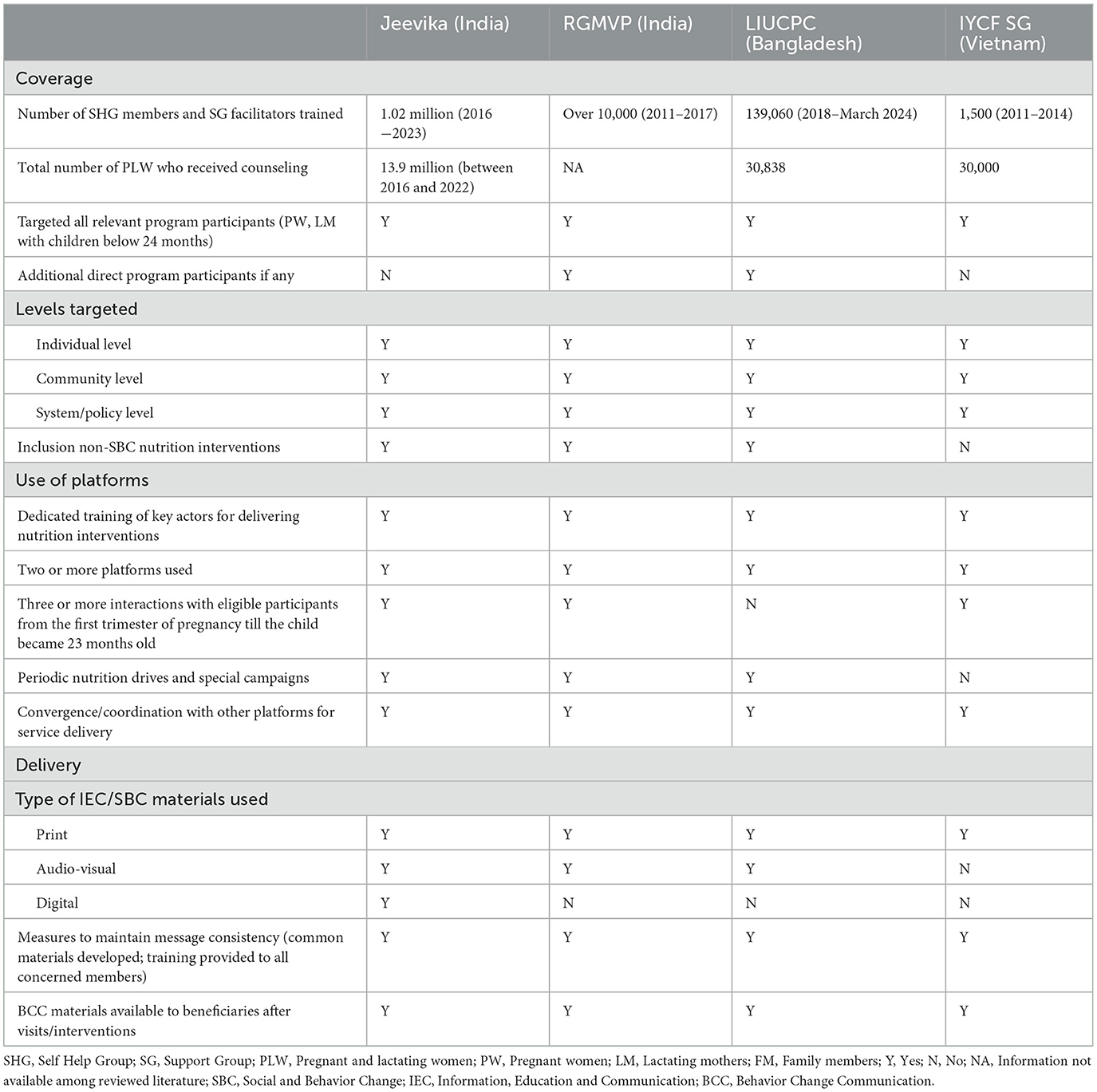

3.3 Coverage and adequacy

Table 2 shows that all models aimed to reach pregnant and lactating women (PLW) and key influencers through SBC interventions. Since not all PLW were SHG members, Jeevika used a two-step approach, identifying PLW within SHG households through members and then reaching them via home visits and community events (53, 54). RGMVP used village maps to track PLW and their needs, combining this with joint home visits. LIUPCP employed similar methods, while the Vietnam IYCF SG model involved village heads to boost community participation and attendance (54, 58, 59).

Table 2. Program coverage, targeting, and delivery metrics for the training of facilitators who delivered the interventions by country.

In 2022, Jeevika targeted 1.82 million mother-child dyads, reaching 45% of PLW in Bihar. LIUPCP in Bangladesh reached over 1.39 million dyads, and Vietnam's IYCF SGs covered 33,000 PLW across nine provinces (53, 54, 58). All models used multiple touchpoints, including weekly and monthly meetings, home visits, and community events to deliver consistent nutrition messages. For example, Jeevika reached each mother 16 times over 6 months, while Vietnam's IYCF model had monthly meetings and occasional community gatherings.

Community mobilization and raising awareness of government nutrition services were central to all models. SHGs played a key role in encouraging participation and promoting nutrition interventions in collaboration with government programs. LIUPCP also organized urban communities to demand services through town federations, while Vietnam's IYCF SG model coordinated efforts with local health systems (61, 62).

3.4 Processes and pathways

Table 3 shows that the models integrated SBC interventions into SHGs and SGs due to their strong outreach and mobilization platforms. SHGs target individuals and households in marginalized communities, making them suitable for health and nutrition-focused SBC efforts. In India, SHGs targeted rural poor populations, while in Bangladesh and Vietnam, urban poor and ethnic minorities in remote areas were reached. Prior evidence, local contexts, and formative studies guided the design of interventions, with models like Jeevika using socio-ecological and human-centered design approaches (Table 3).

Capacity building was key across all four models, employing a cascade training approach (53–58). Jeevika and RGMVP developed detailed training modules for community mobilizers, nutrition resource persons, and master resource persons (MRPs), combining classroom teaching with participatory methods like role plays and group discussions. By 2017, Jeevika trained 1,500 MRPs, 7,000 nutrition resource persons, and 80,000 community mobilizers, while RGMVP trained over 124,000 community resource persons (Table 3). LIUPCP and Vietnam's IYCF SGs also emphasized training facilitators to lead SBC efforts (62–64).

The models differed in support structures, with Jeevika having a clear ongoing support framework, including post-training assistance and monitoring. Supportive supervision was strong in the Vietnam IYCF SG and present in Jeevika and LIUPCP for nutrition components. Monitoring structures for health and nutrition were clearly defined in most models, except for RGMVP, which tracked improvements during IYCF campaigns. Quality assessment in Jeevika included mobile data collection and feedback mechanisms, while RGMVP tracked knowledge retention and practices in nutrition-focused campaigns (Table 3).

3.5 Outcomes, sustainability and scale-up

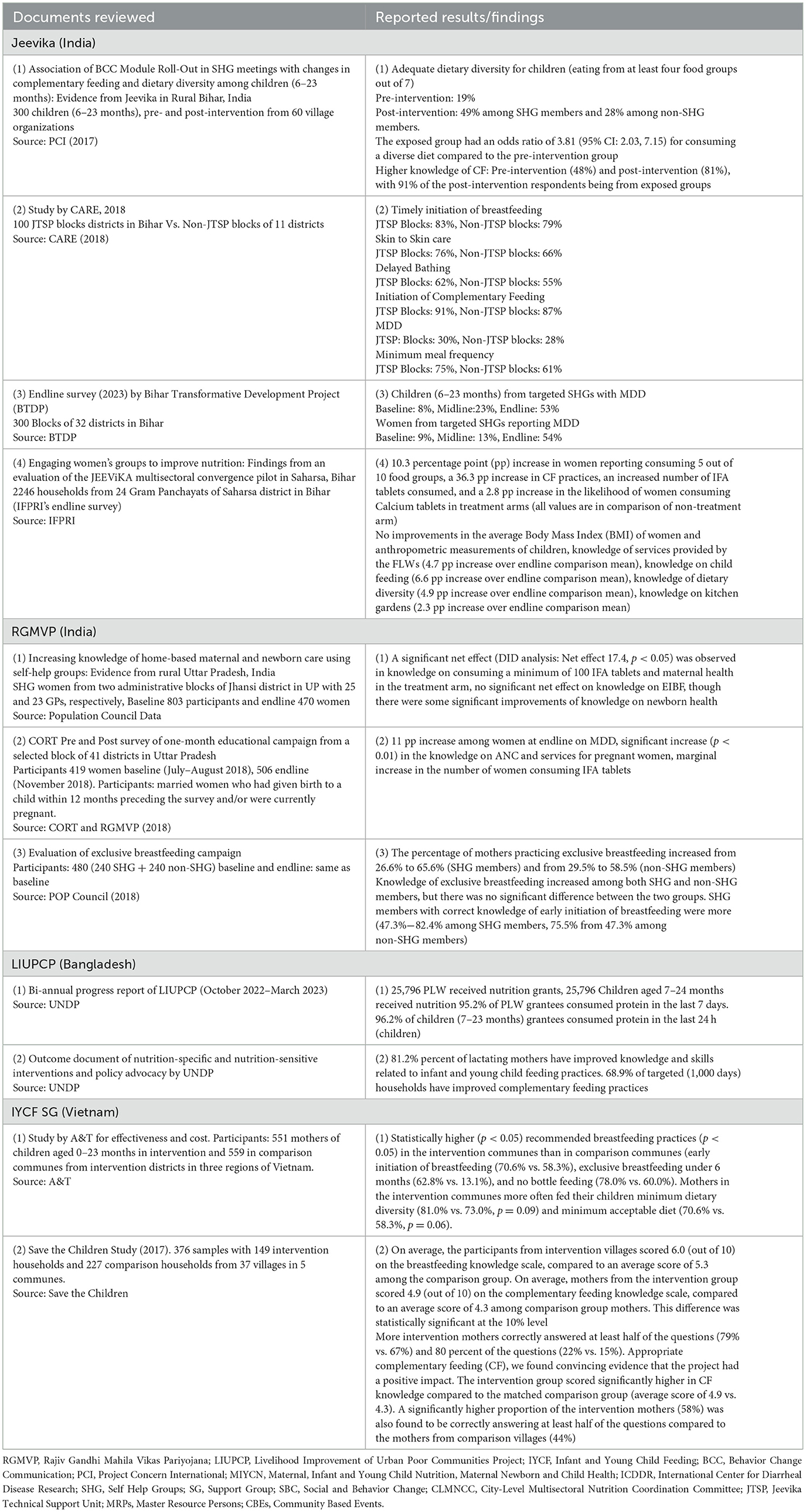

Table 4 shows that the primary goals of SHGs and SGs were to raise awareness of optimal maternal nutrition, IYCF practices, and government schemes, while improving health and nutrition among mother-child dyads. Outcomes showed that SHG members in Jeevika and LIUPCP had higher knowledge of breastfeeding and complementary feeding than non-members. RGMVP's nutrition campaigns also increased awareness, and Vietnam's IYCF SGs had better outcomes on breastfeeding knowledge. SHG families had higher rates of early breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding. Jeevika improved dietary diversity, while RGMVP showed better exclusive breastfeeding rates and increased consumption of Iron Folic Acid (IFA) (60, 64–70).

Sustainability and scale-up showed mixed results. Jeevika expanded from 101 blocks to 300 blocks in Bihar, supported by the state government and the World Bank (70). It contributed to India's National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM), integrating food, nutrition, and health initiatives. RGMVP, active in 49 districts at its peak, saw a decline after donor support ended in 2018, though learnings informed future models (Table 4).

LIUPCP in Bangladesh, ending in 2024, proposed multisectoral coordination for sustained nutrition efforts, with some cities already operating independently. Vietnam's IYCF SG model scaled up successfully, covering 267 villages in nine provinces, supported by local government and partners like Save the Children and World Vision (Table 4). The model adapted to local investments for long-term sustainability (71–73).

3.6 Challenges

SHGs faced critical challenges including adequacy, sustainability, and quality assessment. Jeevika, RGMVP, and LIUPCP, initially focused on livelihood, poverty reduction, and financial inclusion, were not designed for health and nutrition interventions, requiring significant capacity building and new components, increasing the workload for community mobilizers.

SHGs had gaps in time allocation and meeting frequency. Jeevika's groups met weekly for about 30 min on health topics aside from training, while RGMVP had monthly meetings with similar time for health discussions. Meeting frequency varied, especially during harvest season. In Vietnam, IYCF SG meetings occurred monthly for PLW and bimonthly for others, with messages reviewed at subsequent meetings.

Sustaining SHGs proved challenging, with dissolutions reported for Jeevika and RGMVP, impacting HNS component implementation. Low meeting participation also hindered SBC interventions. Most women in Jeevika, RGMVP, and LIUPCP were not of reproductive age, leading to reliance on home visits and community events to reach PLW, which saw low attendance in some cases. Jeevika's assessment revealed some CMs lacked necessary skills, leading to refresher training.

The Vietnam IYCF SG model faces socio-cultural and economic barriers, with traditional practices and limited resources affecting adherence to recommended feeding practices. Remote areas struggle with healthcare access, and post-support from Alive & Thrive, reduced funding led to decreased meeting frequency. While a sustainability plan is in place, not all communities can fund activities beyond national program support.

3.7 Summary of findings

SHGs and SGs are recognized as effective community-based models for improving maternal and child nutrition. This literature review, focusing on India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, explores their role in enhancing health and nutrition outcomes, particularly for PLW from marginalized communities. Drawing from 34 documents, the review highlights that SHGs in these countries use decentralized, peer-driven approaches to deliver social behavior change interventions like peer learning, interpersonal communication, and community events. These interventions have improved knowledge of breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and dietary diversity among SHG members. However, challenges such as sustaining group participation, overcoming socio-cultural barriers, and logistical difficulties remain significant.

Sustainability and fidelity issues arose from low participation, irregular meetings, and capacity gaps. Economic barriers, traditional practices, and reduced support also hindered activity sustainability, despite plans in place.

4 Discussion

Our synthesis shows that while integrating SBC interventions for MIYCN into SHGs and SGs produces encouraging outcomes, key lessons must be learned about designing and implementing these interventions, especially with regard to long-term sustainability and scalability. With the growing focus of global funding bodies and national governments on community-led and localized development, SHGs and SGs gain further significance as platforms embedded within communities (74). Recently, development partners and funding organizations have provided evidence supporting demand-driven capacity building, institutionalizing feedback and accountability within communities, and making monitoring, learning, and evaluation more participatory for successful community-led development (75, 76).

The integration processes must feature intensive capacity building for SHGs, SG meeting facilitators, and community mobilizers. Earlier studies have also highlighted the need for capacity building in community-based interventions to empower communities and place their voices at the center of solving the challenges that affect them (77–79). Our synthesis showed that the models focused on developing training materials that combine technical information with soft skills to maintain consistency in delivering training and orienting key actors to build their knowledge and counseling skills. Implementing agencies collaborated with technical partners, which significantly aided this process.

A significant challenge in implementing MIYCN-focused interventions is that although SHGs provide a suitable platform, their reach is not always direct. While PLW are members of SHG households, they are not necessarily direct members of SHGs themselves. Therefore, identifying ways to reach PLW and their influencers during the design phase is essential. Strategies such as listing identified PLW, conducting home visits, organizing open-to-all community events, and hosting nutrition drives or campaign-like events were some of the pathways used by the reviewed models to ensure coverage of all target groups. A previous systematic review on behavioral change interventions to improve maternal and child nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa also shows positive impacts of interventions based on behavior change theory, counseling, and communication (79). These interventions improved infant and child nutrition outcomes by reducing wasting, underweight, and stunting, and enhancing dietary diversity and total food consumption, as well as maternal psychological outcomes. Additionally, this study shows that interventions incorporating the Behavior Change Wheel functions (incentivization, persuasion, and environmental restructuring) were most effective (79).

Beyond reach, the time allocated for nutrition discussions in SHGs and the frequency of meetings are equally crucial, as SHG members are expected to amplify nutrition messages beyond the group. There are encouraging examples of intensity when we consider the frequency of interactions with PLW. These groups, particularly those that followed a layered approach with multiple interventions, enabled multiple contact points with target groups. Studies from various countries have emphasized the benefits of multiple contact points for improving MIYCN outcomes (79, 80), which was made possible through SHGs. SGs dedicated to PLW do not face this challenge. However, SG models must work with influencers to ensure attendance at meetings and secure buy-in from existing health structures to guarantee the availability of facilitators and government ownership.

Our review also showed that engaging influencers at the policy level is essential to position maternal and child nutrition as critical for both health and economic productivity outcomes and to garner support for community institutions. This finding aligns with previous studies that deem advocacy at the policy level crucial for the success of health and nutrition interventions (81–83). Political will and policy-level support played a significant role in sustaining the Jeevika model. The scale-up and successful adaptation of CLMNCC under the LIUPCP program in Bangladesh, as well as the implementation of the Vietnam IYCF SG, demonstrated the substantial role of policy advocacy in ensuring effective program implementation, monitoring, and review through existing government systems.

This study has limitations. This scoping review focuses on four known Alive &Thrive programs and the processes and outcomes reported in the selected documents. Therefore, this review might not capture information from other programs and interventions, making it an internal organizational review, which could theoretically cause bias toward positive outcomes. Although we were not able to address such biases, to our knowledge, there are no other similar interventions at the project sites, and the majority of documents used for this study were peer-reviewed publications and published reports. A previous study indicates that behavior change communication might not be sufficient (79). Since we are not able to evaluate background information beyond the intervention, the effect could be the result of other interventions in the same community, such as food supplementation, cash transfers, mass communications, or general improvements in socioeconomic status (79). Further research is needed to better understand the influence of different aspects of these models and to identify which attributes are most associated with impact.

Additionally, we acknowledge that this was a scoping review rather than a systematic review, and we could not use search engines other than PubMed. Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus which are subscription-based databases that were not permitted by the donor due to their associated costs. Our search in the Cochrane Library did not yield any relevant literature reviews. Also, due to resource constraints, we could only arrange for one author within our organization to perform article screening and data extraction, and no formal software or tools were used to manage the process or evaluate the quality of documents. Given that the findings were reviewed by authors who have worked with these programs from the beginning, we anticipate that key literature and information have been captured.

In conclusion, SHG-based models have demonstrated success in improving health and nutrition outcomes but face challenges related to scale, sustainability, and participation. To address these challenges, it is essential to strengthen these models by maintaining rigorous and intense implementation, providing high-quality capacity building, conducting regular assessments, securing policy support, and ensuring sustained political commitment. Additionally, SHG models should be closely monitored and documented to bolster advocacy, generate political will, and foster ownership. The findings from this study can be utilized by policymakers, project managers, scholars, health workers, and frontline workers in designing, planning, implementing, and evaluating relevant intervention models in low-resource settings of lower-middle-income countries.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AV: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TN: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AP: Writing – original draft. NP: Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – review & editing. PZ: Writing – review & editing. ZM: Writing – review & editing. SG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – review & editing. TF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number INV-042392) to cover staff time spent working with previously collected data or information generated under a prior project funded by the same donor (grant number OPP-50838). The views and opinions set out in this article represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the donor. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author's Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Taylor, who provided an overview of UNDP's project, PCI and Jeevika for their active cooperation. The authors thank Tina Sanghvi and Mackenzie Green from the Alive & Thrive initiative at FHI 360 Global Nutrition for the comments and suggestions to improve this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Jain S, Ahsan S, Robb Z, Crowley B, Walters D. The cost of inaction: a global tool to inform nutrition policy and investment decisions on global nutrition targets. Health Policy Plan. (2024) 39:819–30. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czae056

2. Caleyachetty R, Kumar NS, Bekele H, Manaseki-Holland S. Socioeconomic and urban-rural inequalities in the population-level double burden of child malnutrition in the East and Southern African Region. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3:e0000397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000397

3. Govindaraj R, Premkumar A, Sivasankar V. Prevalence and assessment of child malnutrition in South Asia. MGM J Med Sci. (2024) 10:685–90. doi: 10.4103/mgmj.mgmj_246_23

4. Haddad L, Cameron L, Barnett I. The double burden of malnutrition in SE Asia and the Pacific: priorities, policies and politics. Health Policy Plan. (2015) 30:1193–206. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu110

5. The World Bank. The World Bank and Nutrition. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/nutrition/overview#1 (accessed September 18, 2024).

6. Shenoy S, Sharma P, Rao A, Aparna N, Adenikinju D, Iloegbu C, et al. Evidence-based interventions to reduce maternal malnutrition in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Front Health Serv. (2023) 3:1155928. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1155928

7. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Undernourished and Overlooked: A Global Nutrition Crisis in Adolescent Girls and Women. UNICEF Child Nutrition Report Series, 2022. New York, NY: UNICEF (2023).

8. Nguyen PH, Kachwaha S, Tran LM, Sanghvi T, Ghosh S, Kulkarni B, et al. Maternal diets in India: gaps, barriers, and opportunities Nutrients. (2021) 13:3534. doi: 10.3390/nu13103534

9. Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals. Geneva: World Health Organization (2009). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK148967/ (accessed January 3, 2024).

10. Islam MH, Nayan MM, Jubayer A, Amin MR. A review of the dietary diversity and micronutrient adequacy among the women of reproductive age in low- and middle-income countries. Food Sci Nutr. (2023) 12:1367–79. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3855

11. Shaun MMA, Nizum MWR, Shuvo MA, Fayeza F, Faruk MO, Alam MF, et al. Determinants of minimum dietary diversity of lactating mothers in the rural northern region of Bangladesh: a community-based cross-sectional study. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e12776. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12776

12. Drummond E, Watson F, Blankenship J. UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Office, Nutrition Section, UNICEF, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, et al. Southeast Asia Regional Report on Maternal Nutrition and Complementary Feeding. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/9466/file/Maternal%20Nutrition%20and%20Complementary%20Feeding%20Regional%20Report.pdf (accessed January 3, 2024).

13. FHI Solutions. Closing the Gender Nutrition Gap: An Action Agenda for women and girls. (2023). Available at: https://gendernutritiongap.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/The-Gender-Nutrition-Gap-an-Action-Agenda-for-women-and-girls.-July-2023.-1.pdf (accessed February 5, 2024).

14. Shumayla S, Irfan EM, Kathuria N, Rathi SK, Srivastava S, Mehra S, et al. Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among lactating mothers in Haryana, India: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. (2022) 22:525. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03588-5

15. TCI (Tata–Cornell Institute). Food, Agriculture, and Nutrition in South Asia. Ithaca, NY: TCI. (2023). Available at: https://tci.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/FAN-South-Asia-2023.pdf (accessed January 5, 2024).

16. Laelago Ersado T. Causes of malnutrition. In:Saeed F, Ahmed A, Afzaal A, , editors. Combating Malnutrition through Sustainable Approaches. London: IntechOpen. (2023). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.104458

17. Mohammad A, Khan A. Child malnutrition and mortality in South Asia: a comparative analysis. Eur Econ Lett. (2024) 14:1008–18. doi: 10.1177/097152310701400110

18. Kurniasih D, Al Zaharo R, Nursamtari R, Januarti M. Stunting prevention in low and middle income countries. In:, , editor. Published Conference Proceedings of International Conference on Scientific Studies. (2023). Jave, Indonesia. Available at: https://scientists.internationaljournallabs.com/index.php/sc/article/view/6/6 (accessed September 8, 2024).

19. Lassi ZS, Irfan O, Hadi R, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. PROTOCOL: effects of interventions for infant and young child feeding (IYCF) promotion on optimal IYCF practices, nutrition, growth, and health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. (2018) 14:1–26. doi: 10.1002/CL2.189

20. Tran LM, Nguyen PH, Young MF, Martorell R, Ramakrishnan U. The relationships between optimal infant feeding practices and child development and attained height at age 2 years and 6-7 years. Matern Child Nutr. (2024) 20:e13631. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13631

21. Gatica-Domínguez G, Neves PAR, Barros AJD, Victora CG. Complementary feeding practices in 80 low- and middle-income countries: prevalence of and socioeconomic inequalities in dietary diversity, meal frequency, and dietary adequacy. J Nutr. (2021) 151:1956–64. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab088

22. Global Breastfeeding Collective. Global Scorecard. [Database] Availabel at: https://www.globalbreastfeedingcollective.org/about-collective (accessed December 15, 2023).

23. Rahman MA, Kundu S, Rashid HO, Tohan MM, Islam MA. Socio-economic inequalities in and factors associated with minimum dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months in South Asia: a decomposition analysis. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e072775. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072775

24. Lakhanpaul M, Roy S, Benton L, Lall M, Khanna R. Vijay VK, et al. Why India is struggling to feed their young children? A qualitative analysis for tribal communities. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e051558. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051558

25. Nguyen TT, Nguyen PH, Hajeebhoy N, Nguyen HV, Frongillo EA. Infant and young child feeding practices differ by ethnicity of Vietnamese mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:214. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0995-8

26. Gokhale D, Rao S. Socio-economic and socio-demographic determinants of diet diversity among rural pregnant women from Pune, India. BMC Nutr. (2022) 8:54. doi: 10.1186/s40795-022-00547-2

27. Nguyen PH, Kachwaha S, Avula R, Young M, Tran LM, Ghosh S, et al. Maternal nutrition practices in Uttar Pradesh, India: role of key influential demand and supply factors. Matern Child Nutr. (2019) 15:e12839. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12839

28. Haque S, Salman M, Hossain MS, Saha SM, Farquhar S, Hoque MN, et al. Factors associated with child and maternal dietary diversity in the urban areas of Bangladesh. Food Sci Nutr. (2023) 12:419–29. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3755

29. Banu B, Haque S, Shammi SA, Hossain MA. Maternal nutrition knowledge and determinants of the child nutritional status in the northern region of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Multidiscip Sci Res. (2023) 7:11–21. doi: 10.46281/bjmsr.v7i1.2018

30. Nguyen PH, Headey D, Frongillo EA, Tran LM, Rawat R, Ruel MT, et al. Changes in underlying determinants explain rapid increases in child linear growth in alive and thrive study areas between 2010 and 2014 in Bangladesh and Vietnam. J Nutr. (2017) 147:462–9. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.243949

31. Simwanza NR, Kalungwe M, Karonga T, Mtambo CMM, Ekpenyong MS, Nyashanu M, et al. Exploring the risk factors of child malnutrition in Sub-Sahara Africa: a scoping review. Nutr Health. (2023) 29:61–9. doi: 10.1177/02601060221090699

32. Chowdhury MRK, Rahman MS, Billah B, Rashid M, Almroth M, Kader M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with severe undernutrition among under-5 children in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal: a comparative study using multilevel analysis. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:10183. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36048-w

33. Workicho A, Biadgilign S, Kershaw M, Gizaw R, Stickland J, Assefa W, et al. Social and behaviour change communication to improve child feeding practices in Ethiopia: Matern Child Nutr. (2021) 17:e13231. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13231

34. Kennedy E, Stickland J, Kershaw M, Biadgilign S. Impact of social and behavior change communication in nutrition specific interventions on selected indicators of nutritional status. J Hum Nutr. (2018) 2:34–46. doi: 10.36959/487/280

35. Sanghvi T, Haque R, Roy S, Afsana K, Seidel R, Islam S, et al. Achieving behaviour change at scale: Alive and Thrive's infant and young child feeding programme in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr. (2016) 12:141–54. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12277

36. Flax VL, Bose S, Escobar-DeMarco J, Frongillo EA. Changing maternal, infant and young child nutrition practices through social and behaviour change interventions implemented at scale: lessons learned from Alive and Thrive. Matern Child Nutr. (2023) e13559. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13559

37. Litvin K, Grandner GW, Phillips E, Sherburne L, Craig HC. Kieu Anh Phan, et al. How do social and behavioral change interventions respond to social norms to improve women's diets in low- and middle-income countries? A scoping review. Curr Dev Nutr. (2024) 8:103772–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cdnut.2024.103772

38. Metcalfe-Hough V, Fenton W, Saez P, Spencer A. The Grand Bargain in 2021: an independent review. HPG commissioned report. London: ODI. (2021). Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/sites/default/files/migrated/2022-06/Grand%20Bargain%20Annual%20Independent%20Report%202022.pdf

39. USAID. Localization at USAID: the vision and approach. (2022). Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/USAIDs_Localization_Vision-508.pdf (accessed March 2, 2024).

40. Ghosh S, Mahapatra MS, Tandon N, Tandon D. Achieving sustainable development goal of women empowerment: a study among self-help groups in India. FIIB Bus Rev. (2024) 13:477–91. doi: 10.1177/23197145231169074

41. WHO. Essential nutrition actions: Improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/84409/9789241505550_eng.pdf?sequence=1World Bank (accessed April 30, 2024).

42. World Bank. World Bank Support to Reducing Child Undernutrition. Independent Evaluation Group. Washington, DC: World Bank (2021).

43. Nichols C. Self-help groups as platforms for development: the role of social capital. World Dev. (2021) 146:105575. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105575

44. Bhanot A, Sethi V, Murira Z, Singh KD, Ghosh S, Forissier T, et al. Right message, right medium, right time: powering counseling to improve maternal, infant, and young child nutrition in South Asia. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1205620. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1205620

45. Desai S, Misra M, Das A, Singh RJ, Sehgal M, Gram L, et al. Community interventions with women's groups to improve women's and children's health in India: a mixed-methods systematic review of effects, enablers and barriers. BMJ Glob Health. (2020) 5:e003304. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003304

46. Saggurti N, Atmavilas Y, Porwal A, Schooley J, Das R, Kande N, et al. Effect of health intervention integration within women's self-help groups on collectivization and healthy practices around reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health in rural India. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0202562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202562

47. Sethi V, Bhanot A, Bhalla S, Bhattacharjee S, Daniel A, Sharma DM, et al. Partnering with women collectives for delivering essential women's nutrition interventions in tribal areas of eastern India: a scoping study. J Health Popul Nutr. (2017) 36:20. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0099-8

48. Scott S, Gupta S, Kumar N, Raghunathan K, Thai G, Quisumbing A, et al. A women's group-based nutrition behavior change intervention in India has limited impacts amidst implementation barriers and a concurrent national behavior change Campaign. Curr Dev Nutr. (2021) 5(Supplement 2):179. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzab035_087

49. Husain Z, Dutta M. Impact of Self Help Group membership on the adoption of child nutritional practices: evidence from JEEViKA's health and nutrition strategy programme in Bihar, India. J Int Dev. (2023) 35:781–99. doi: 10.1002/jid.3703

50. Pradhan MR, Unisa S, Rawat R, Surabhi S, Saraswat A, Reshmi SR, et al. Women empowerment through involvement in community-based health and nutrition interventions: evidence from a qualitative study in India. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0284521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284521

51. UNICEF, ENN, Project Concern International, India. Delivering for Nutrition in South Asia: equity and inclusion (2023). Available at: https://www.ennonline.net/sites/default/files/2024-01/delivering_for_nutrition_in_south_asia_equity_and_inclusion.pdf (accessed March 5, 2024).

52. Hazra A, Das A, Ahmad J, Singh S, Chaudhuri I, Purty A, et al. Matching intent with intensity: implementation research on the intensity of health and nutrition programs with women's self-help groups in India. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2022) 10:e2100383. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00383

53. Hora G, Krishna P, Singh RK, Ranjan A. Lessons from a decade of rural transformation in Bihar. in JEEViKA Learning Note Series. (2019). Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/298391515516507115/122290272_20180012032255/additional/122548-WP-P090764-PUBLIC-India-BRLP-Booklet-p.pdf (accessed December 1, 2023).

54. Mozumdar A, Khan M, Mondal SK, Mohanan P. Increasing knowledge of home based maternal and newborn care using self-help groups: evidence from rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Sex Reprod Healthc. (2018) 18:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.08.003

55. Hazra A, Atmavilas Y, Hay K, Saggurti N, Verma RK, Ahmad J, et al. Effects of health behaviour change intervention through women's self-help groups on maternal and newborn health practices and related inequalities in rural india: a quasi-experimental study. EClinicalMedicine. (2019) 18:100198. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.10.011

56. Jeevika. Transforming Lives: Social and Behavior Change for Child Health and Nutrition in Bihar. New Delhi: PCI (2024).

57. UNDP Bangladesh and Alive & Thrive. Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Strategy for the Livelihoods Improvement of Urban Poor Communities Project (LIUPCP). Dhaka: UNDP Bangladesh [Report] (2021).

58. Alive and Thrive. Overview of the Alive and Thrive Infant and Young Child Feeding Community-based SG model in Viet Nam. (2013). Available at: https://www.aliveandthrive.org/sites/default/files/attachments/IYCF-SG-Four-Pager-English-Sept-2013.pdf (accessed January 12, 2024).

59. Rajiv Gandhi Charitable Trust. Annual Report 2017-2018. (2018). Available at: https://www.rgct.in/pdfs/annual_report_2017_18.pdf (accessed February 5, 2024).

60. National Urban Poverty Reduction Programme (NUPRP). National Urban Poverty Reduction Programme (NUPRP) Bi-Annual Progress Report October 2022-March 2023 [Report] (2024). Available at: https://erc.undp.org/evaluation/documents/download/23704

61. Kabir AFMI Livelihoods Livelihoods Improvement of Urban Poor Communities Project (LIUPCP). Outcome Documentation of Nutrition Sensitive and Specific Interventions, and Policy Advocacy. [Report]. Dhaka (2024).

62. Nguyen TT, Hajeebhoy N, Li J, Do CT, Mathisen R, Frongillo EA, et al. Community support model on breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in remote areas in Vietnam: implementation, cost, and effectiveness. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:121. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01451-0

63. Irani L, Schooley J, Supriya, Chaudhuri I. Layering of a health, nutrition and sanitation programme onto microfinance-oriented self-help groups in rural India: results from a process evaluation. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:2131. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12049-0

64. Mondal S, Joe W, Akhauri S, Thakur P, Kumar A, Pradhan N, et al. Association of BCC module roll-out in SHG meetings with changes in complementary feeding and dietary diversity among children (6-23 months)? Evidence from JEEViKA in Rural Bihar, India. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0279724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279724

65. Noack A-L, Buggineni P, Purty A, Shalini S. Lessons from a Decade of Rural Transformation in Bihar. JEEViKA Learning Note Series, No. 8. (2021) 1–78. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/298391515516507115/122290272_201800120100025/additional/122548-WP-P090764-PUBLIC-India-BRLP-Booklet-p.pdf (accessed February 7, 2024).

66. Project Concern International. Quality Assessment and Support Process and Methodology. Available at: www.projectconcernindia.org (accessed January 14, 2024).

67. Barkat A, Ahamed FM, Rabby MF, Osman A, Bedi A. Human Development Research Centre, and International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University of Rotterdam (ISS-EUR). Report on Annual Outcome Monitoring (AOM) 2022 of National Urban Poverty Reduction Programme [Report]. Dhaka (2022).

68. Rajiv Gandhi Mahila Vikas Pariyojana Centre for Operations Research and Training and Centre for Operations Research and Training (CORT) Vadodara. Maternal Health Campaign in Uttar Pradesh - Key Findings from the Baseline/Endline Survey: An Overview - Draft Report. Vadodara: Centre for Operations Research and Training (CORT) (2019).

70. Ministry Ministry of Rural Development, Govt. of India. Aajeevika. Available at: https://aajeevika.gov.in/what-we-do/social-inclusion-and-social-development (accessed May 10, 2024).

71. Rana MM, Huan NV, Thach NN, Bach TX, Cuong NT. Effectiveness of community-based infant and young child (IYCF) support group model in reducing child undernutrition among ethnic minorities in Vietnam (p. ii). (2017). Available at: https://www.ennonline.net/fex/58/communitysupportgroupvietnam (accessed February 7, 2024).

72. Decision1719/QD-TTg Decision1719/QD-TTg of 2021 approving the National Target Program for socio-economic development in ethnic minority and mountainous areas for the period 2021-2030 phase I: from 2021 to 2025 issued by the Prime Minister. Hanoi.

73. Vietnam News. National target programme on socio-economic development in ethnic minority areas approved. (2021). Available at: https://vietnamnews.vn/society/1059976/national-target-programme-on-socio-economic-development-in-ethnic-minority-areas-approved.html (accessed March 6, 2024).

74. Wubshet, L. Community-led development: perspectives and approaches of four member organizations. London: Qeios.

75. USAID. Committed to change: USAID localization report FY 2023. (2023). Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/localization/progressreport/full-report-fy2023 (accessed October 15, 2024).

76. Ingram, G. Locally driven development: overcoming the obstacles. Brookings Global Working Papers #173. Cantre for Sustainable Development at Brookings. (2022). Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Locally-Driven-Development.pdf (accessed October 15, 2024).

77. Traverso-Yepez M, Maddalena V, Bavington W, Donovan C. Community capacity building for health. SAGE Open. (2012) 2:215824401244699. doi: 10.1177/2158244012446996

78. Buckner L, Carter H, Ahankari A, Banerjee R, Bhar S, Bhat S, et al. Three-year review of a capacity building pilot for a sustainable regional network on food, nutrition and health systems education in India. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. (2021) 4:59–68. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000180

79. Watson D, Mushamiri P, Beeri P, Rouamba T, Jenner S, Proebstl S, et al. Behaviour change interventions improve maternal and child nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3:e0000401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000401

80. Lamstein S, Stillman T, Koniz-Booher P, Aakesson A, Collaiezzi B, Williams T, et al. Evidence of Effective Approaches to Social and Behavior Change Communication for Preventing and Reducing Stunting and Anemia: Report from a Systematic Literature Review. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project (2014).

81. Shahan, Asif M, Jahan F. Opening the policy space: the dynamics of nutrition policy making in Bangladesh. Montpellier: Agropolis International, Global Support Facility for the National Information Platforms for Nutrition initiative (2017).

82. Resnick D, Anigo KM, Anjorin O, Deshpande S. Voice, access, and ownership: enabling environments for nutrition advocacy in India and Nigeria. Food Sec. (2024) 16:637–58. doi: 10.1007/s12571-024-01451-2

Keywords: breastfeeding, community-based interventions, complementary feeding, maternal nutrition, self-help groups, social and behavior change, support groups

Citation: Verma A, Nguyen T, Purty A, Pradhan N, Husan A, Zambrano P, Mahmud Z, Ghosh S, Mathisen R and Forissier T (2024) Changing maternal and child nutrition practices through integrating social and behavior change interventions in community-based self-help and support groups: literature review from Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam. Front. Nutr. 11:1464822. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1464822

Received: 15 July 2024; Accepted: 25 October 2024;

Published: 14 November 2024.

Edited by:

Manisha Nair, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Zahra Hoodbhoy, Aga Khan University, PakistanFentaw Wassie Feleke, Woldia University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2024 Verma, Nguyen, Purty, Pradhan, Husan, Zambrano, Mahmud, Ghosh, Mathisen and Forissier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thomas Forissier, dGZvcmlzc2llckBmaGkzNjAub3Jn

Anumeha Verma1

Anumeha Verma1 Tuan Nguyen

Tuan Nguyen Narottam Pradhan

Narottam Pradhan Alomgir Husan

Alomgir Husan Paul Zambrano

Paul Zambrano Sebanti Ghosh

Sebanti Ghosh Roger Mathisen

Roger Mathisen Thomas Forissier

Thomas Forissier