- 1Department of Health Economics, Wellbeing and Society, National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 2Research Division, Indonesian Breastfeeding Mother Association, Surabaya, Jakarta, Indonesia

Introduction: Donor human milk (DHM) is recommended as the second-best alternative form of supplementation when a mother is unable to breastfeed directly. However, little is known about the experience of mothers and families in the communities regarding accessing and donating expressed breastmilk in Indonesia. This study aimed to identify the experience related to donor human milk in the society in Indonesia.

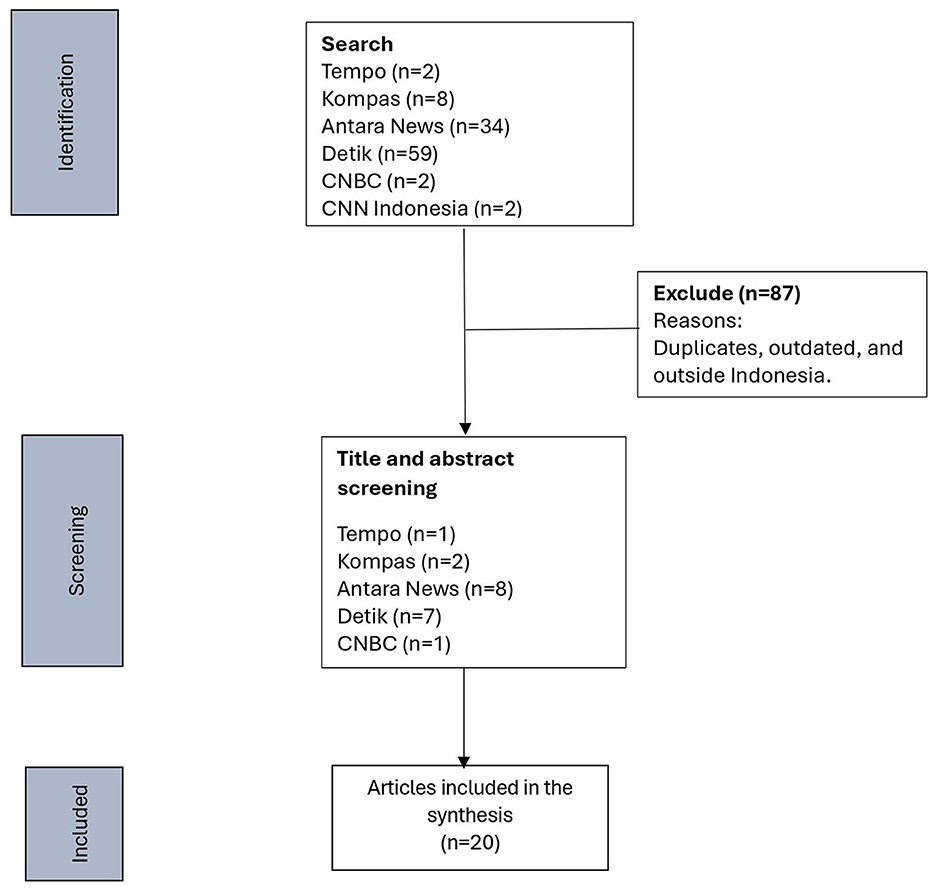

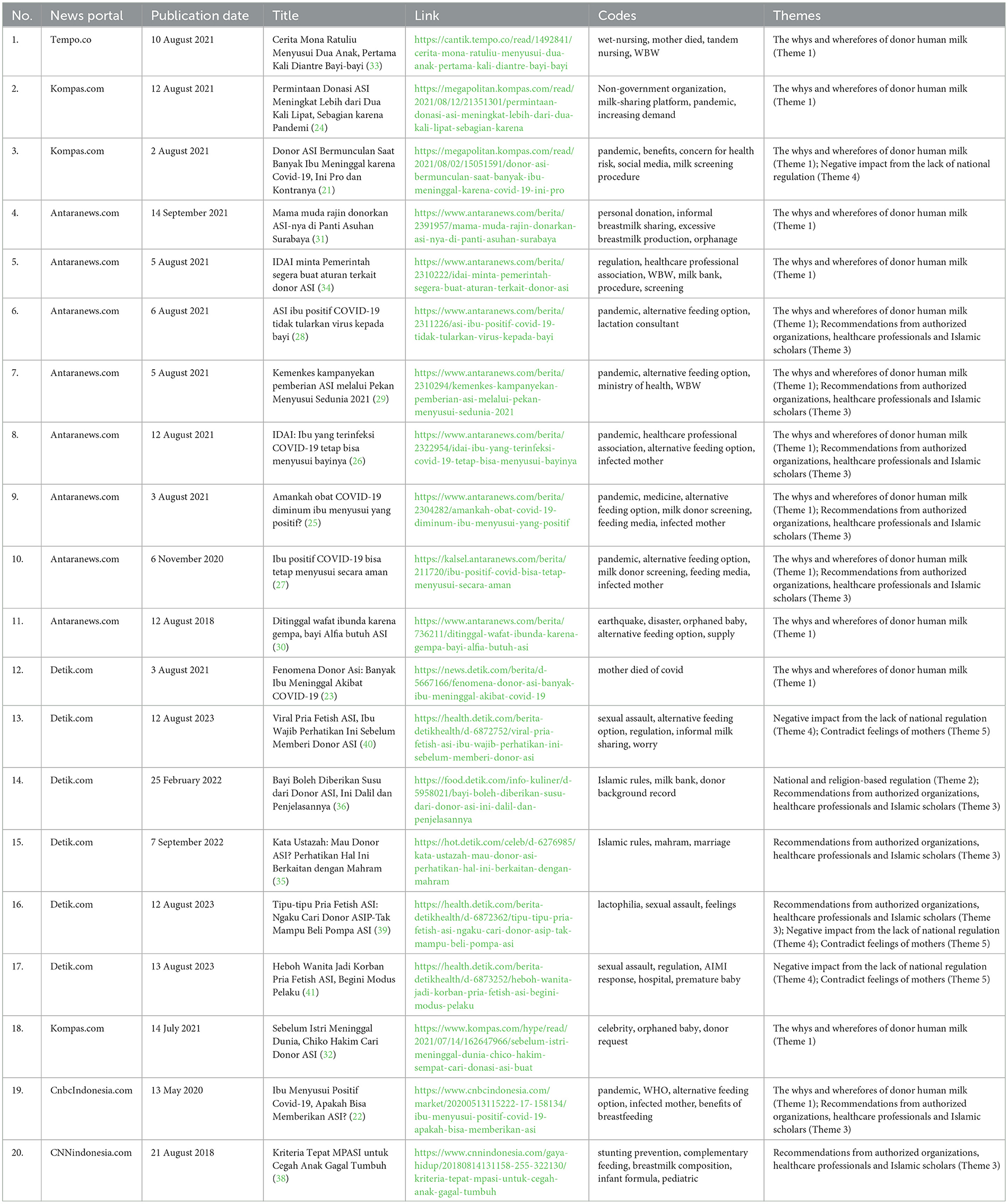

Method: A search was conducted through six main online news portals. The keywords used included “donor human milk,” “expressed breastmilk,” and “wet nursing” in the Indonesian language, Bahasa Indonesia. A total of 107 articles were found, but only 20 articles were included for analysis using a qualitative media content analysis approach.

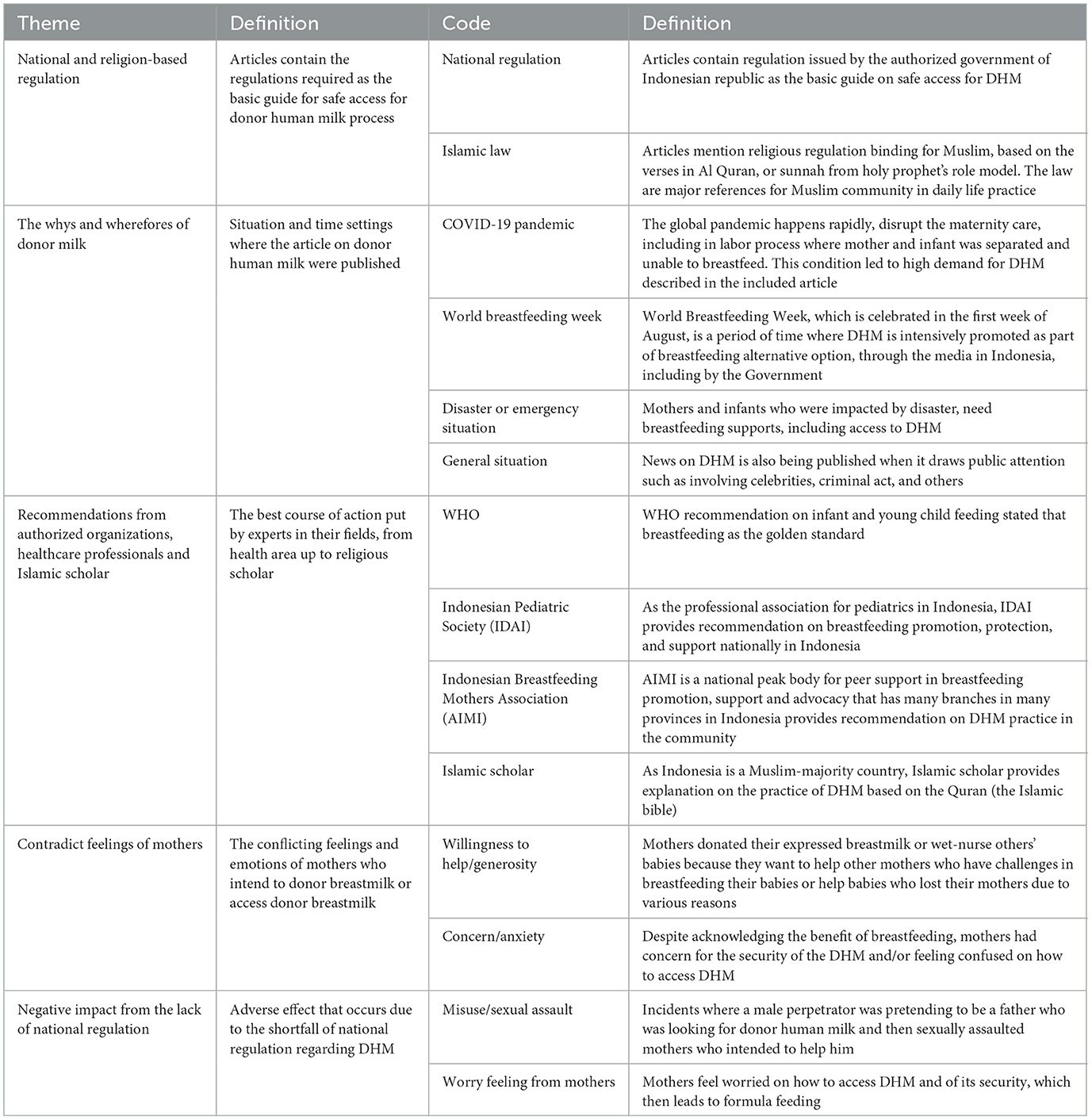

Results: In the study, the following five themes were identified: (1) the whys and wherefores of donor human milk, (2) national and religious-based regulations, (3) recommendations from authorized organizations, healthcare professionals, and Islamic scholars, (4) the negative impact from the lack of national regulations, and (5) contradictory feelings among mothers.

Conclusion: With the lack of detailed information on how to access or donate expressed human milk and the absence of a human milk bank in place, informal human milk sharing is inevitably occurring in the community. This has also raised concerns among authorized organizations, healthcare professionals, and Islamic scholars. Consequently, mothers, both donors and recipients, experienced negative impacts, which included contradictory feelings. Engaging with Islamic scholars and healthcare professionals to develop clear guidelines and regulations to enable mothers' and families' access and/or make contributions to DHM in a safe and accountable way is critical to prevent further problems from occurring in Indonesian society.

1 Introduction

Breastfeeding exclusively for the first 6 months of an infant's life is recommended as the gold standard by the World Health Organization (WHO) as it provides all the nutrients a baby needs (1). Along with complementary nutritious food, breastmilk continues to provide up to half or more of a child's nutritional needs during the second half of the first year and up to one-third of the needs during the second year of life (1). However, when mothers are unable to breastfeed their babies due to medical conditions or when babies and their mothers are separated by sickness, death, or an emergency, the best alternative is to get expressed breastmilk from the infant's own mother (2, 3). If it is not possible, then donor human milk (DHM) or wet nursing is the next recommendation, and a breastmilk substitute fed with a cup is the last resort (2, 3).

Indonesia is a developing country in Southeast Asia, with 277 million citizens and 4.46 million live births estimated in 2023 (4). However, only 37.3% of babies under 6 months old were exclusively breastfed in 2018 (5). The systemic barriers to optimal breastfeeding discussed in the Lancet papers (6–8) are occurring in Indonesia. Although the Indonesian government protects, supports, and promotes breastfeeding and has adopted the 1989 Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (Ten Steps) (9) into its national law (10), the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitute (WHO Code) and the subsequent World Health Assembly (WHA) resolutions (11) have not been fully adopted in the national legal framework. The WHO Code and the relevant WHA resolution are essential to ensure that parents and other caregivers are protected from inappropriate and misleading information (12). Therefore, it is included in the 2018 Ten Steps (9), but it has not been adopted in the Indonesian national regulations. This is one of the key factors why breastfeeding protection is still lacking in Indonesia (13). Violations of the Code by health workers, breastmilk substitute companies, and their representatives were also found in provinces in Indonesia (13, 14).

The marketing of breastmilk substitutes has also been reaching the digital world through social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok (15). Indonesian mothers and families often access information through the Internet (16), which includes seeking information about breastfeeding support and access to donor human milk (DHM). At the time of writing this article, there were no data on the existence of any human milk bank in Indonesia; thus, the practice of informal milk sharing, including through the Internet, inevitably occurs. Little is known about the experience of mothers and families in the communities regarding accessing and donating expressed breastmilk or the practice of wet nursing in Indonesia. This study aimed to identify the experience related to DHM in Indonesian society using media content analysis.

2 Methods

We searched through six main online news portals of Indonesia (Kompas.com, tempo.com, antaranews.com, detik.com, cnbcindonesia.com, and cnnindonesia.com) from 29th to 30th January 2024. The keywords used included “breastmilk donor,” “expressed breastmilk,” and “wet nursing” in the Indonesian language, Bahasa Indonesia. The term donor human milk is defined as expressed breastmilk that is voluntarily donated by a mother directly to babies other than her child, as well as the practice of wet nursing (cross-nursing). Articles published from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2023 were included because this period was considered to represent the situation before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Articles published outside Indonesia were excluded.

A total of 107 articles were found from the six online news portals, but only 20 articles were included for analysis using a qualitative media content analysis approach (17). News media was chosen for its significant impact and effects on public awareness, perceptions, and, sometimes, behavior (17). We employed a qualitative content analysis (18), which, in contrast to quantitative content analysis, is not an automatic process of counting manifest text elements but instead requires an in-depth study. The qualitative content analysis can be either inductive or deductive, and we analyzed the data inductively (19). The full process of the search and selection is described in Figure 1. The collected articles were recorded in an Excel sheet. Both authors read the full articles repeatedly and coded data individually. These articles were discussed, amended, and refined as a team. The potential themes were discussed and then agreed upon (Table 1). The details of the included articles are in Table 2.

The trustworthiness of the content analysis was evaluated using Lincoln and Guba's criteria, which included the following (20): credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was achieved by describing the data analysis process in sufficient detail and through a multidisciplinary investigator collaboration, which involved a hospital-based qualified breastfeeding counselor (AH), an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant, and a university-based researcher (AP). Both authors were Indonesian, were members of the board committee of the Indonesian Breastfeeding Mothers Association (Asosiasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia/hereafter referred to as AIMI), and have a public health background. This study's findings might be transferrable to other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) having similarities to Indonesia; however, it cannot be guaranteed that the results are generalizable. To demonstrate dependability, all the raw data and analysis processes were documented to provide an audit trail. Confirmability was established through multiple team meetings discussing the analysis.

3 Results

We identified the following five themes: (1) The whys and wherefores of donor human milk, (2) national and religion-based regulation, (3) recommendations from authorized organizations, healthcare professionals, and Islamic scholars, (4) the negative impact from the lack of national regulations, and (5) contradictory feelings among mothers.

3.1 Theme 1: the whys and wherefores of donor human milk

Most of the studies were published at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic (21–28). Despite acknowledging the benefits of breastmilk, many people were worried about the possibility of transmitting the SARS-CoV-2 virus by giving breastmilk through direct breastfeeding, by giving expressed breastmilk from own mother, or by giving donated expressed breastmilk. The studies discussed whether consuming donor human milk was safe during the pandemic.

Some studies discussing donor human milk were published during World Breastfeeding Week, which is celebrated every August from the 1st to the 7th (29). Donor human milk was recommended by the Indonesian Pediatric Society as an alternative solution when mothers cannot breastfeed their babies.

One study shared the need for DHM during an emergency, specifically an earthquake (30). It discussed a case where the emergency response team looked for and successfully found donor human milk for an orphaned baby.

Three studies described the experience of two Indonesian celebrities and one social media celebrity (commonly referred to as celebgram) (31–33). One was a male celebrity whose wife died, and he stated his intention to look for donor milk. The other one was a female celebrity who became a wet nurse mother for her nephew, whose mother died after birth. The celebgram's story primarily concerned her experience in donating expressed breastmilk to babies in orphanages.

3.2 Theme 2: national and religion-based regulation

In one study, the Indonesian Pediatric Society (Ikatan Dokter Anak Indonesia—hereafter referred to as IDAI) and AIMI requested the Indonesian government to establish a clear and strong regulation regarding DHM (34). This recommendation is due to the reality of informal human milk sharing in the community, which involves the increasing request for expressed breast milk through social media without a reliable screening process. As the largest breastfeeding support group in Indonesia, AIMI receives information about many mothers and families who require DHM but have no access to it.

In addition, some articles discussed religion-based regulations, namely Islamic law, regarding providing or accessing DHM (35, 36). There are rules regarding DHM, for instance, infants who receive DHM, both directly through wet nursing and from expressed breastmilk for several times until the infant is satiated, are considered the donor's milk daughter or son, and this child's relationships with the donor's biological children become those of milk siblings, which means that marriage is forbidden between them (37).

3.3 Theme 3: recommendations from authorized organizations, healthcare professionals, and Islamic scholars

Many of the studies mentioned recommendations regarding donor human milk from authorized organizations, such as AIMI and IDAI (22, 26–29, 38). They explained the best practices concerning DHM, which included the screening procedure. Furthermore, they also suggested the development of a clear regulation to reduce the health risks of unscreened donor milk.

As a Muslim-majority country, there were also recommendations from Islamic scholars based on the Quran, the holy book of Islam (35, 36). The practice of DHM is also regulated in the Quran, including the implication, such as when the recipient baby and the donor mother and her biological child(ren) become family, then marriage among the children would be considered permanently unlawful (mahram).

3.4 Theme 4: negative impact from the lack of national regulations

In some studies, healthcare professionals, authorized organizations, and Islamic scholars recommended some best practices as they believed that national regulations regarding donor human milk were lacking (34, 39, 40). The lack of national regulations has led to varied informal practices occurring in society, which are unregulated and risky for the mother, such as scams and assaults (39–41).

Furthermore, the IDAI has urged the Indonesian government to issue clear regulations to establish a legal framework for DHM and to ensure that safe and quality DHM is provided based on medical indications.

3.5 Theme 5: contradictory feelings among mothers

Some studies mentioned the motivation and feelings of donor mothers, such as the intention to help other mothers, regardless of not knowing the recipient mothers/babies (31, 33).

Three studies discussed the misuse of donor human milk, reporting incidents where a male perpetrator, pretending to be a father, sexually assaulted mothers who intended to help him (39–41). This incident made headlines in the news for some time and made a lot of mothers feel worried and anxious regarding donating their expressed breastmilk.

4 Discussion

The Indonesian government protects, supports, and promotes breastfeeding and has launched several national regulations in this regard, including Government Regulation No. 33/2012 on Breastfeeding regarding exclusive breastfeeding (10), which has recently been updated to Government Regulation No. 28/2024 (42). This regulation was developed as a guideline for the Law of Health No. 36/2009 (43), which was later revised as the Omnibus Health Law (Law No. 17/2023) (44). This regulation commands every mother to exclusively breastfeed their baby for the first 6 months and to continue until 2 years. Article 11 of the regulation states that when a baby's own mother cannot provide exclusive breastmilk to the baby, it can be provided by a donor mother. However, there are several requirements for donor human milk:

a. Requests must be made by the baby's own mother or family.

b. The identity, religion, and address of the donor mother must be clearly identified by the recipient baby's own mother or her family.

c. Agreement must be obtained from the donor mother after knowing the identity of the recipient baby.

d. The donor mother must be in good health and must not have medical issues, which include being HIV-negative, not having HSV-1 infection in the breast region, not undergoing anti-epileptic or opioid therapy, not having consumed radioactive iodine-131 within 2 months, using numerous topical iodine, such as povidone–iodine, or not receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy.

e. Donor human milk (DHM) must not be for sale.

However, all the regulations mentioning DHM only acknowledge it as an alternative infant feeding method when breastfeeding is not an option. There are no detailed procedures describing how mothers and families can access DHM or how mothers can donate their expressed breast milk. A study mentioned the recommendation from the IDAI that human donor milk should be prioritized for those who are really in need, such as premature or sick babies, or those who are separated from their mothers, rather than for mothers with perceived low supply issues, who possibly need breastfeeding support. Perceived low milk supply is experienced by many mothers and is one of the factors that influence early cessation of breastfeeding (45). The IDAI's recommendation aligns with the Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA)'s policy, which encourages using donor milk that supports rather than replaces breastfeeding (46).

According to the data at the time of writing, Indonesia does not have a human milk bank, and hence, the practice of donor human milk occurs informally in the community. This practice is due to the generosity and willingness of mothers to help other mothers and babies (47, 48). The strong belief that breastfeeding the offspring is mandatory, which is based on the Quran, has influenced most Indonesian women to consider breastfeeding the norm. A majority of Indonesian people are Muslims (87%) (49), and breastfeeding is recommended as the best practice and is mentioned as one of the parents' responsibilities in the Quran. For example, it is the father's responsibility to ensure his baby is getting the best nutrition by being breastfed; therefore, he needs to fulfill the wife's need to be able to breastfeed. If it cannot be achieved, then the father is responsible for finding a wet nurse or DHM. Many Islamic scholars in Indonesia also provide recommendations on how to fulfill the child's right to be breastfed as regulated in the Quran (50).

The development of a human milk bank in Indonesia should consider the Islamic regulation (syariat), in addition to the health regulation. The Fatwa from the Council of Indonesian Ulama regulates kinship for DHM (51) and recommends that the Indonesian Ministry of Health issue a regulation on DHM based on the Fatwa. Singapore successfully established a human milk bank through the engagement of the relevant authorities and open dialogue. Finding common ground may allow vulnerable preterm infants to benefit from DHM in a manner that respects and does not compromise religious beliefs (52). A Malaysian study highlighted that the establishment of a religiously abiding human milk bank is achievable by educating mothers on breastfeeding benefits and addressing their religious concerns (53). Furthermore, the attitude and behavior of healthcare professionals also influenced the development of a human milk bank in one public hospital in Surabaya, Indonesia (54).

As a part of an informal sharing method, recommendations to ensure the safety of DHM should emphasize the importance of medical screening of the donor and safe milk handling practices (55). The IDAI has a guideline regarding DHM for public use to minimize the risk of mishandling donated expressed breastmilk (56). As a series of medical tests that are required is not covered by any health insurance, the medical screening for safety is mostly done by interview alone and is based on trust. This might bring a greater risk of a lack of reliability. As mothers' and families' knowledge of the benefits of breastfeeding is improving, the demand for DHM is also increasing. Therefore, the development of an official human milk bank is becoming more important. Many informal online groups on the Internet and social media have been established to bridge the demand for and supply of DHM. This is understandable as Indonesia has a high percentage of users of social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp (15, 57). Although it was a rare case, the incident where a man pretended to be a father searching for DHM for his child and approached a potential donor to abuse her is an example of the negative impact of the lack of national regulations. Therefore, the IDAI also recommended that the government establish a formal organization or authority to regulate this matter (56, 58).

The use of DHM in emergency situations is already mentioned in the Guideline of Nutrition in Disaster Management published by the Indonesian Ministry of Health (59); however, the guideline only mentions the requirements adopted from the Government Regulation No. 33/2012 (10), which is now updated to the Government Regulation No. 28/2024 (42). The guideline does not describe how and where mothers can access DHM. During disasters in Indonesia, formula donation commonly occurs (60–62). This practice is due to the regulation that was issued by the local government that allows formula donations to take place with the approval from the head of the local health office (63, 64). This practice has been shown to increase the incidence rate of diarrhea among infants and young children who received the donated breastmilk substitute (61). Globally, the challenges in maintaining breastfeeding during an emergency, especially with formula donation, have been shown in many studies (65–69).

Eight out of the 20 articles included in this study were published during the COVID-19 pandemic (21–23, 25–28). Although the WHO stated that COVID-19-infected mothers could continue breastfeeding with a safe protocol (70), many maternity services implemented protocols that disrupted the initiation of breastfeeding (71–77). Furthermore, guidelines published by various authorities and countries were inconsistent (78). However, as the pandemic progressed, many studies showed that breastfeeding both directly and via expressed breastmilk provided significant benefits to the infants (79). As highlighted in the included studies in this study (21–24), many families searched for DHM when the mothers were infected with COVID-19. Noting this, AIMI and IDAI have recommended the development of a human milk bank.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the experience of DHM in Indonesia using a qualitative media content analysis approach. The use of online media is making it possible to capture what is really happening in the community as online media is rapidly growing in Indonesia. This study has limitations, for example, we limited the search to the top six online news portals within the past 5 years. We did not search through other media, such as newspapers and magazines; this may have narrowed the results. Furthermore, after the screening of the title and full text, the total number of articles included was only 20, which might not be considered a large sample. However, the five-year period was considered sufficient for capturing the experience within a society as the regulations and conditions were not much different from the current ones and it represented the period of time before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

5 Conclusion

The Indonesian government protects, supports, and promotes breastfeeding as regulated in Government Regulation Number 33 Year 2012, later updated to Government Regulation Number 28 Year 2024, which includes the use of DHM. However, due to the lack of detailed information on how to access or donate expressed human milk and the absence of a human milk bank in place, informal human milk sharing is inevitably occurring in the community. This also has raised concerns among authorized organizations, healthcare professionals, and Islamic scholars.

Consequently, there are negative impacts experienced by mothers, both the donor and recipient, including contradictory feelings, from the lack of a clear regulation regarding DHM and the lack of development of a human milk bank.

Engaging with Islamic scholars and healthcare professionals to develop clear guidelines and regulations to enable mothers' and families' access or contribution to DHM in a safe and accountable way is critical for preventing the occurrence of further problems in Indonesian society.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. Breastfeeding 2024. Available at: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/child/nutrition/breastfeeding/en/ (accessed November 23, 2023).

2. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #3: Supplementary Feedings in the Healthy Term Breastfed Neonate. (2017).

3. World Health Organization United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization (2003).

4. Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia nomor HK.01.07/MENKES/140/2024 tentang. Indonesian Ministry of Health (2024). Available at: https://p2p.kemkes.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/KMK-HK.01.07-MENKES-140-2024-Perubahan-Sasasran-Program-2021-2025_Pusdatin_Feb-2024.pdf

5. National Institute of Health Research and Development. Hasil Utama Riskesdas 2018 (Main Results of Basic Health Survey 2018). Jakarta (2018).

6. Rollins N, Piwoz E, Baker P, Kingston G, Mabaso KM, McCoy D, et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy. Lancet. (2023) 401:486–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01931-6

7. Pérez-Escamilla R, Tomori C, Hernández-Cordero S, Baker P, Barros AJD, Bégin F, et al. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet. (2023) 401:472–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01932-8

8. Baker P, Smith JP, Garde A, Grummer-Strawn LM, Wood B, Sen G, et al. The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress. Lancet. (2023) 401:503–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01933-X

9. World Health Organization. Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. (2018). Available at: https://www.who.int/activities/promoting-baby-friendly-hospitals/ten-steps-to-successful-breastfeeding (accessed February 27, 2024).

10. Pemberian ASI Eksklusif (Exclusive Breastfeeding). Indonesian Government (2012). Available at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/5245/pp-no-33-tahun-2012

11. World Health Organization. International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. Geneva: World Health Organization (1981).

12. World Health Organization. Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes: National Implementation of the International Code, Status Report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

13. Asosiasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia. Breaking the Code: International code violations on digital platforms and social media in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic (April 2020-April 2021). Jakarta (2021).

14. Hidayana I, Februhartanty J, Parady VA. Violations of the international code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes: Indonesia context. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:165–73. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016001567

15. World Health Organization. Scope and impact of digital marketing strategies for promoting breastmilk substitutes. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

16. Sumaedi S, Sumardjo S. Factors influencing internet usage for health purposes. Int J Health Gov. (2020) 25:205–21. doi: 10.1108/IJHG-01-2020-0002

17. Macnamara J. Media content analysis: its uses, benefits and best practice methodology. Asia-Pac Public Relat J. (2005) 6:1–34.

18. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2019). Available at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/content-analysis-4e (accessed June 13, 2024).

19. Kyngäs H. Inductive Content Analysis. In:Kyngäs H, Mikkonen K, Kääriäinen M, , editors. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2020). p. 13–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6_2

20. Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistric Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage (1985). doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

21. Arbi IA. Donor ASI Bermunculan Saat Banyak Ibu Meninggal karena Covid-19, Ini Pro dan Kontranya. Kompas. (2021). Available at: https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2021/08/02/15051591/donor-asi-bermunculan-saat-banyak-ibu-meninggal-karena-covid-19-ini-pro (accessed August 2, 2021).

22. Astutik Y. Ibu Menyusui Positif Covid-19, Apakah Bisa Memberikan ASI? CNBC Indonesia. (2020). Available at: https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/market/20200513115222-17-158134/ibu-menyusui-positif-covid-19-apakah-bisa-memberikan-asi (accessed May 13, 2020).

23. Fadhila AR. Fenomena Donor ASI: Banyak Ibu Meninggal Akibat COVID-19. Detik. (2021). Available at: https://news.detik.com/berita/d-5667166/fenomena-donor-asi-banyak-ibu-meninggal-akibat-covid-19 (accessed August 3, 2021).

24. Hapsari MA, Carina J. Permintaan Donasi ASI Meningkat Lebih dari Dua Kali Lipat, Sebagian karena Pandemi. Kompas. (2021). Available at: https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2021/08/12/21351301/permintaan-donasi-asi-meningkat-lebih-dari-dua-kali-lipat-sebagian-karena (accessed August 12, 2021).

25. Santosa LW. Amankah obat COVID-19 diminum ibu menyusui yang positif? Antara. (2021). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2304282/amankah-obat-covid-19-diminum-ibu-menyusui-yang-positif (accessed August 3, 2021).

26. Simanjuntak MH. IDAI: Ibu yang terinfeksi COVID-19 tetap bisa menyusui bayinya. Antara. (2021). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2322954/idai-ibu-yang-terinfeksi-covid-19-tetap-bisa-menyusui-bayinya (accessed August 12, 2021).

27. Yuniar N. Ibu positif COVID bisa tetap menyusui secara aman. Antara. (2020). Available at: https://kalsel.antaranews.com/berita/211720/ibu-positif-covid-bisa-tetap-menyusui-secara-aman (accessed August 6, 2020).

28. Yuniar N. ASI ibu positif COVID-19 tidak tularkan virus kepada bayi. Antara. (2021). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2311226/asi-ibu-positif-covid-19-tidak-tularkan-virus-kepada-bayi (accessed August 6, 2021).

29. Shanti HD. Kemenkes kampanyekan pemberian ASI melalui Pekan Menyusui Sedunia 2021. Antara. (2021). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2310294/kemenkes-kampanyekan-pemberian-asi-melalui-pekan-menyusui-sedunia-2021 (accessed August 5, 2020).

30. Santosa LW. Ditinggal wafat ibunda karena gempa, bayi Alfia butuh ASI. Antara. (2018). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/736211/ditinggal-wafat-ibunda-karena-gempa-bayi-alfia-butuh-asi (accessed August 12, 2018).

31. Hakim A. Mama muda rajin donorkan ASI-nya di Panti Asuhan Surabaya. Antara. (2021). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2391957/mama-muda-rajin-donarkan-asi-nya-di-panti-asuhan-surabaya (accessed September 14, 2021).

32. Lova C, Setuningsih N. Sebelum Istri Meninggal Dunia, Chico Hakim Sempat Cari Donasi ASI buat Bayinya. Kompas. (2021). Available at: https://www.kompas.com/hype/read/2021/07/14/162647966/sebelum-istri-meninggal-dunia-chico-hakim-sempat-cari-donasi-asi-buat (accessed July 14, 2021).

33. Novita M. Cerita Mona Ratuliu Menyusui Dua Anak, Pertama Kali Diantre Bayi-bayi. Tempo. (2021). Available at: https://cantik.tempo.co/read/1492841/cerita-mona-ratuliu-menyusui-dua-anak-pertama-kali-diantre-bayi-bayi (accessed August 10, 2021).

34. Shanti HD. IDAI minta Pemerintah segera buat aturan terkait donor ASI. Antara. (2021). Available at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2310222/idai-minta-pemerintah-segera-buat-aturan-terkait-donor-asi (accessed August 5, 2021).

35. Kata Ustazah: Mau Donor ASI? Perhatikan Hal Ini Berkaitan dengan Mahram. Detik. (2022). Available at: https://hot.detik.com/celeb/d-6276985/kata-ustazah-mau-donor-asi-perhatikan-hal-ini-berkaitan-dengan-mahram (accessed September 7, 2022).

36. Setya D. Bayi Boleh Diberikan Susu dari Donor ASI, Ini Dalil dan Penjelasannya. Detik. (2022). Available at: https://food.detik.com/info-kuliner/d-5958021/bayi-boleh-diberikan-susu-dari-donor-asi-ini-dalil-dan-penjelasannya (accessed February 25, 2022).

37. Norsyamlina CAR, Salasiah Hanin H, Latifah AM, Zuliza K, Nurhidayah MH, Rafeah S, et al. A cross-sectional study on the practice of wet nursing among Muslim mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:68. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03551-9

38. Juniman PT. Kriteria Tepat MPASI untuk Cegah Anak Gagal Tumbuh. CNN Indonesia. (2018). Available at: https://www.cnnindonesia.com/gaya-hidup/20180814131158-255-322130/kriteria-tepat-mpasi-untuk-cegah-anak-gagal-tumbuh (accessed August 21, 2018).

39. Azizah KN. Tipu-tipu Pria Fetish ASI: Ngaku Cari Donor ASIP-Tak Mampu Beli Pompa ASI. Detik. (2023). Available at: https://health.detik.com/berita-detikhealth/d-6872362/tipu-tipu-pria-fetish-asi-ngaku-cari-donor-asip-tak-mampu-beli-pompa-asi (accessed August 12, 2023).

40. Azizah KN. Viral Pria Fetish ASI, Ibu Wajib Perhatikan Ini Sebelum Memberi Donor ASI. Detik. (2023). Available at: https://health.detik.com/berita-detikhealth/d-6872752/viral-pria-fetish-asi-ibu-wajib-perhatikan-ini-sebelum-memberi-donor-asi (accessed August 12, 2023).

41. Kautsar A. Heboh Wanita Jadi Korban Pria Fetish ASI, Begini Modus Pelaku. Detik. (2023). Available at: https://health.detik.com/berita-detikhealth/d-6873252/heboh-wanita-jadi-korban-pria-fetish-asi-begini-modus-pelaku (accessed 13, August 2023).

42. Peraturan Pelaksanaan Undang-Undang Nomor 17 tahun 2023 tentang Kesehatan. Indonesian Government (2024). Available at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/294077/pp-no-28-tahun-2024

43. Undang-Undang nomor 36 tahun 2009 tentang Kesehatan. Indonesian Government (2009). Available at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/38778/uu-no-36-tahun-2009

44. Undang-Undang nomor 17 tahun 2023 tentang Kesehatan. Indonesian Government (2023). Available at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/258028/uu-no-17-tahun-2023

45. Huang Y, Liu Y, Yu X-Y, Zeng T-Y. The rates and factors of perceived insufficient milk supply: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13255. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13255

47. Vickers N, Matthews A, Paul G. Factors associated with informal human milk sharing among donors and recipients: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2024) 19:e0299367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299367

48. Li J, Ip HL, Fan Y, Kwok JYY, Fong DYT, Lok KYW, et al. Unveiling the voices: exploring perspectives and experiences of women, donors, recipient mothers and healthcare professionals in human milk donation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Women Birth. (2024) 37:101644. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2024.101644

49. Kementrian Agama Republik Indonesia. Jumlah penduduk menurut agama. (2023). Available at: https://satudata.kemenag.go.id/dataset/detail/jumlah-penduduk-menurut-agama (accessed March 3, 2024).

50. Bensaid B. Breastfeeding as a fundamental islamic human right. J Relig Health. (2021) 60:362–73. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00835-5

51. Majelis Ulama Indonesia. Fatwa Majelis Ulama Indonesia tentang Seputar Masalah Donor Air Susu Ibu (Istirdla'). Jakarta (2013).

52. Jayagobi PA, Ong C, Pang PCC, Wong AA, Wong ST, Chua MC, et al. Addressing milk kinship in milk banking: experience from Singapore's first donor human milk bank. Singapore Med J. (2023) 64:343–5. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2022031

53. Ramachandran K, Dahlui M, Nik Farid ND. Motivators and barriers to the acceptability of a human milk bank among Malaysians. PLoS ONE. (2024) 19:e0299308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299308

54. Adawiah R, Utomo MT. Correlation between knowledge and attitude to the behavior of health workers regarding acceptance of human milk bank in general hospital Dr. Soetomo Surabaya. Int J Res Publication. (2021) 89:237–42. doi: 10.47119/IJRP1008911120212437

55. Sriraman NK Evans AE Lawrence R Noble L The The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Board of Directors. Academy of breastfeeding medicine's 2017 position statement on informal breast milk sharing for the term healthy infant. Breastfeed Med. (2018) 13:2–4. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2017.29064.nks

56. Indonesian Society of Pediatry. Donor ASI. (2014). Available at: https://www.idai.or.id/artikel/klinik/asi/donor-asi (accessed March 14, 2024).

57. Digital Marketing Institute. Social Media: What countries use it most and what are they using? (2022). Available at: https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/social-media-what-countries-use-it-most-and-what-are-they-using (accessed March 26, 2024).

58. Yohmi E, Pambudi W, Dewanto N, Yuliarti K, Partiwi IG, Sacharina A, et al. Konsensus Penggunaan ASI Donor: Indonesian Pediatric Society. (2022). Available at: https://www.idai.or.id/publications/buku-idai/konsensus-penggunaan-asi-donor (accessed March 26, 2024).

59. Indonesian Ministry of Health. Pedoman Kegiatan Gizi dalam Penanggulangan Bencana. Jakarta (2012).

60. Fadjriah RN, Salamah AU, Jafar N, Nur R, Dewi NU, Khairunissa., et al. Practice of exclusive breastfeeding at evacuation site post-earthquake in palu city, indonesia. Medico-legal Update. (2020) 20:423–7. doi: 10.37506/mlu.v20i2.1143

61. Hipgrave DB, Assefa F, Winoto A, Sukotjo S. Donated breast milk substitutes and incidence of diarrhoea among infants and young children after the May 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta and Central Java. Public Health Nutr. (2012) 15:307–15. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003423

62. Assefa F, Sukotjo S, Winoto A, Hipgrave D. Increased diarrhoea following infant formula distribution in 2006 earthquake response in Indonesia: evidence and actions. Available at: https://www.ennonline.net/fex/34/special (accessed March 14, 2024).

63. Policy Policy on Milk Formula Donation for Infant and Children Impacted by Earthquake and Tsunami in Palu-Donggala Central Sulawesi KK.03.01/V/769/2018. Directorate General of Public Health; Indonesian Ministry of Health (2018).

64. Policy on Milk Formula Donation for Infant and Children Impacted by Earthquake 441.8/10839/Kesmas/2022. Cianjur Regional Head of District Health Office (2022).

65. Hwang CH, Iellamo A, Ververs M. Barriers and challenges of infant feeding in disasters in middle- and high-income countries. Int Breastfeed J. (2021) 16:62. doi: 10.1186/s13006-021-00398-w

66. Iellamo A, Wong CM, Bilukha O, Smith JP, Ververs M, Gribble K, et al. “I could not find the strength to resist the pressure of the medical staff, to refuse to give commercial milk formula”: a qualitative study on effects of the war on Ukrainian women's infant feeding. Front Nutr. (2024) 11:1225940. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1225940

67. Smith JP, Iellamo A. Wet nursing and donor human milk sharing in emergencies and disasters: a review. Breastfeed Rev. (2020) 28:7–23.

68. Wise PA. Infant feeding in an emergency: an oversight in United Kingdom emergency planning. J Conting Crisis Manag. (2022). doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12444

69. Azad F, Rifat MA, Manir MZ, Biva NA. Breastfeeding support through wet nursing during nutritional emergency: a cross sectional study from Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0222980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222980

70. World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19: interim guidance, 27 May 2020. Geneva: WHO (2020). doi: 10.15557/PiMR.2020.0004

71. Amatya S, Corr TE, Gandhi CK, Glass KM, Kresch MJ, Mujsce DJ, et al. Management of newborns exposed to mothers with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. J Perinatol. (2020). doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-0695-0

72. Borg B, Gribble K, Courtney-Haag K, Parajuli KR, Mihrshahi S. Association between early initiation of breastfeeding and reduced risk of respiratory infection: implications for nonseparation of infant and mother in the COVID-19 context. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13328. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1071412/v1

73. Giusti A, Chapin EM, Alegiani SS, Marchetti F, Sani S, Prezioni J, et al. Prevalence of breastfeeding and birth practices during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic within the Italian Baby- Friendly Hospital network. What have we learned? Ann Ist Super Sanità. (2022) 58:100–8.doi: 10.1186/s13006-022-00483-8

74. Gribble K, Mathisen R, Ververs M-t, Coutsoudis A. Mistakes from the HIV pandemic should inform the COVID-19 response for maternal and newborn care. Int Breastfeed J. (2020) 15:67. doi: 10.1186/s13006-020-00306-8

75. Kaufman DA, Puopolo KM. Infants born to mothers with COVID-19—making room for rooming-in. JAMA Pediatr. (2020). doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5100

76. Muñoz-Amat B, Pallás-Alonso CR, Hernández-Aguilar M-T. Good practices in perinatal care and breastfeeding protection during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a national situation analysis among BFHI maternity hospitals in Spain. Int Breastfeed J. (2021) 16:66. doi: 10.1186/s13006-021-00407-y

77. Stuebe A. Should infants be separated from mothers with COVID-19? First, do no harm. Breastfeed Med. (2020) 15:351–2. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2020.29153.ams

78. Vu Hoang D, Cashin J, Gribble K, Marinelli K, Mathisen R. Misalignment of global COVID-19 breastfeeding and newborn care guidelines with World Health Organization recommendations. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. (2020) 3:339–50. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000184

Keywords: breastfeeding, donor milk, breastmilk, infant feeding, content analysis

Citation: Pramono A and Hikmawati A (2024) Donor human milk practice in Indonesia: a media content analysis. Front. Nutr. 11:1442864. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1442864

Received: 03 June 2024; Accepted: 21 August 2024;

Published: 18 September 2024.

Edited by:

Alessandro Iellamo, FHI 360, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Pramono and Hikmawati. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andini Pramono, YW5kaW5pLnByYW1vbm9AYW51LmVkdS5hdQ==

Andini Pramono

Andini Pramono Alvia Hikmawati

Alvia Hikmawati