- 1Laboratory of Metabolic Manipulation of Herbivorous Animal Nutrition, College of Animal Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China

- 2College of Veterinary Medicine, Albutana University, Rufaa, Sudan

- 3State Key Laboratory of Sheep Genetic Improvement and Healthy Production, Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural Reclamation Sciences, Shihezi, China

Moringa oleifera (M. oleifera) is a natural plant that has excellent nutritional and medicinal potential. M. oleifera leaves (MOL) contain several bioactive compounds. The aim of this study was to evaluate the potential effect of MOL polysaccharide (MOLP) on intestinal flora in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis (UC) mice. DSS-induced colitis was deemed to be a well-characterized experimental colitis model for investigating the protective effect of drugs on UC. In this study, we stimulated the experimental mice with DSS 4% for 7 days and prepared the high dose of MOLP (MOLP-H) in order to evaluate its effect on intestinal flora in DSS-induced UC mice, comparing three experimental groups, including the control, DSS model, and DSS + MOLP-H (100 mg/kg/day). At the end of the experiment, feces were collected, and the changes in intestinal flora in DSS-induced mice were analyzed based on 16S rDNA high throughput sequencing technology. The results showed that the Shannon, Simpson, and observed species indices of abundance decreased in the DSS group compared with the control group. However, the indices mentioned above were increased in the MOLP-H group. According to beta diversity analysis, the DSS group showed low bacterial diversity and the distance between the control and MOLP-H groups, respectively. In addition, compared with the control group, the relative abundance of Firmicutes in the DSS group decreased and the abundance of Helicobacter increased, while MOLP-H treatment improves intestinal health by enhancing the number of beneficial organisms, including Firmicutes, while reducing the number of pathogenic organisms, such as Helicobacter. In conclusion, these findings suggest that MOLP-H may be a viable prebiotic with health-promoting properties.

Introduction

The gut is the largest immunological organ and a crucial site for digestion and absorption. Animal intestines contain billions of intestinal bacteria (1). These microbes serve crucial roles in nutritional digestion, absorption, and the body’s immune system, among other physiological and biochemical processes (2). Intestinal flora disruption not only causes pathological alterations in the intestinal tissue, but it can also cause chronic inflammation and the formation of carcinogenic compounds, endangering the host’s health (3).

Ulcerative colitis (UC), a frequent complication of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is a chronic, recurring intestinal condition characterized by pain in the abdomen, weight loss, and bloody stools (4). Over the past few years, anti-inflammatory medications (sulfasalazine or mesalazine), conventional immunosuppressive substances (glucocorticoids, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclosporine A), and biological substances (infliximab and adalimumab) have been demonstrated to help improve UC symptoms (5, 6). However, these treatments have limitations due to potential side effects or significant complications, such as steroid dependence and subsequent infection (7). Therefore, establishing effective alternative methods for preventing and managing UC is important.

Recently, various studies have demonstrated the significance of gut microbiota for human health (8–10). Numerous chronic conditions and their symptoms, including type 2 diabetes, gout, and diseases of the cardiovascular system, have been shown to be strongly associated with the composition and function of the gut microbiota (11–13). In addition to insisting on appropriate long-term medicine for the treatment of various chronic diseases, good dietary practices should be implemented to enhance the balance of nutritional intake. Numerous studies have demonstrated that dietary prebiotics, including plant fiber, polyphenols, and polysaccharides or oligosaccharides, can specifically stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria (14, 15).

M. oleifera (MO) is prevalent in tropical and subtropical Asia and Africa (16). Because it is highly nutrient-dense, the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted MOL as a substitute for imported food supplies in the treatment of malnutrition (17). The leaves can be eaten fresh or cooked as a vegetable. In India, it has been incorporated in various herbal formulations, such as ortho herb and Septilin, for the treatment of various diseases (18). There is expanding interest in the potential use of medicinal plants to treat various disorders due to the advantages of their being cheaper, less toxic, and having fewer side effects (19). It has been reported that the crude aqueous extract of MO leaves (MOL) can reliably reduce the blood glucose level in alloxan-induced diabetic mice (20). Recently, polysaccharides have garnered a significant amount of interest due to their distinct chemical structures and bioactivities. Numerous polysaccharides have reportedly been found to possess a range of beneficial bioactivities, including anti-aging, antioxidant, anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, hypolipidemic, and hypoglycemic characteristics (21, 22).

Polysaccharides have gained interest recently due to their function in weight reduction. They are macromolecular polymers composed of at least 10 monosaccharides connected together via glycosidic linkages (23). Being commonly present in the cells of mammals, plants, algae, and microorganisms, they are natural macromolecular active molecules (24). In this study, we examine the potential regulating effect of MOL polysaccharide (MOLP) on intestinal flora in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced UC mice in order to determine its possible prebiotic benefits.

Materials and methods

Plant material

As described in our previous study (25), the fresh green leaves of M. oleifera were obtained from Yunnan Ruziniu Biotechnology (Yunnan, China). The leaves were cleaned properly by washing and drying under shade at room temperature for 4 days. The dried leaves were processed to make powder and then stored in airtight containers for further use.

Polysaccharide extraction

Polysaccharide was extracted from MOL powder, namely MOLP, using the methods reported in previous studies (25, 26). Briefly, MOLP was extracted three times using 1:10 (w/v) deionized water at 70°C for 90 min, and then centrifuged for 20 min at 4,000 rpm. Using a rotary evaporator, the collected supernatants are mixed and evaporated. After an overnight incubation at 4°C, the concentrations were precipitated by adding dehydrated ethanol to a final concentration of 80% (v/v). Following centrifugation, the precipitates were rinsed with 95% ethanol dissolved in deionized water. The dialysate solution was freeze-dried before being deproteinated using the savage technique (27) (2 g of freeze-dried crude MOLP was dissolved in 100 mL distilled water with Sevage reagent (V chloroform: V n-butanol = 4:1) was used). Then, 1:4 polysaccharide solutions were added and mixed for 1 h before centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Repeat the above procedure with the supernatant until there is no visible, translucent white precipitate between the organic layer and the water layer. The obtained filter residue was washed twice with absolute ethanol, petroleum ether, and absolute ethanol, respectively; and the obtained powdery precipitation was re-dissolved and then freeze-dried to produce MOLP.

Animals and experimental design

Male BALB/c mice (6 to 7 weeks old), weighing 20 ± 2 g, were obtained from Yangzhou University Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Yangzhou, China). Forty-five mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions (12 h light-dark cycle, 25 ± 2°C and 60–80% relative humidity), and fed standard laboratory chow and sterile, distilled water ad libitum in the animal room. All animal experiments were conducted under the Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University, as described in our previous study (25). Briefly, the mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 15) after one week of acclimation. All experimental groups were administered distilled water for the first 3 days; the control group was administered 0.9% (0.2 mL) sodium chloride (NaCl) from day 4 to day 10. The DSS group was administered 4% (w/v) DSS from day 4 to day 10, and the DSS + MOLP-H group was given oral administration with MOLP (100 mg/kg/day) along with the oral administration of 4% (w/v) DSS from day 4 to day 10 for 7 days.

Fecal samples collection

At the end of the experiment, all mice were injected with 0.1% (50 mg/kg, i.p.) pentobarbital sodium and sacrificed after a 10-day experimental period. Feces were collected from each individual mouse and kept at −80°C. Then samples were sent to Panomix Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China) under dry ice conditions.

Extraction of genome DNA

Total genome DNA from samples was extracted using the CTAB/SDS method. DNA concentration and purity were monitored on 1% agarose gels. According to the concentration, DNA was diluted to 1 ng/μL using sterile water.

PCR product quantification and qualification

Mix the same volume of 1X loading buffer (containing SYB green) with PCR products and perform electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel for detection. PCR products were mixed in equidensity ratios. Then, mixture PCR products were purified with the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany).

Library preparation and sequencing

Sequencing libraries was generated using the TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, and index codes were added. The library quality was assessed on the Qubit@ 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. At last, the library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform, and 250 bp paired-end reads were generated.

Microbial analysis

16S rRNA/18SrRNA/ITS genes of separate sections (16S V4/16S V3/16S V3–V4/16S V4–V5, 18S V4/18S V9, ITS1/ITS2, Arc V4) were amplified using particular primers (e.g., 16S V4: 515F-806R, 18S V4: 528F-706R, 18S V9: 1380F-1510R, et al.). All PCR reactions were conducted using 15 μL of Phusion® high-fidelity PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs); 0.2 μM of forward and reverse primers, and approximately 10 ng of template DNA. Sequence analysis was performed by the UPARSE software package using (Uparse v7.0.1001, http://drive5.com/uparse/) (28). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were allocated to sequences with ≥97% similarity. For each OTU, representative sequences were screened for further annotation. Relative abundances of representative bacteria were calculated at the phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels. QIIME (Version 1.7.0) and presented using R software (Version 2.15.3) were used to calculate the Alpha diversity index, including Shannon, Simpson, and observed species. To evaluate variations in species variety between samples, the QIIME software was used to calculate beta diversity on both weighted and unweighted unifrac. Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) analysis was presented using R software’s WGCNA program, stat packages, and ggplot2 platform (Version 2.15.3). Furthermore, the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) method was used to investigate alterations in the microflora community. The LDA threshold was set at >3.0 (29). The Venn diagrams were analyzed using the R package “Venn Diagram.” The bubble diagram was made using the R package “ggplot2.” The functional prediction was investigated using Tax4Fun.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS Statistics 22.0 software, and the diagrams were created using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0). Data sets with more than two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple range tests. p-values of <0.05, <0.01, or <0.001 indicate statistical significance.

Results

Structural characterization of MOLP

Our previous study described the molecular weight (Mw), monosaccharide composition, and characteristic analysis of MOLP.

Effects of MOLP on the diversity and abundance of gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice

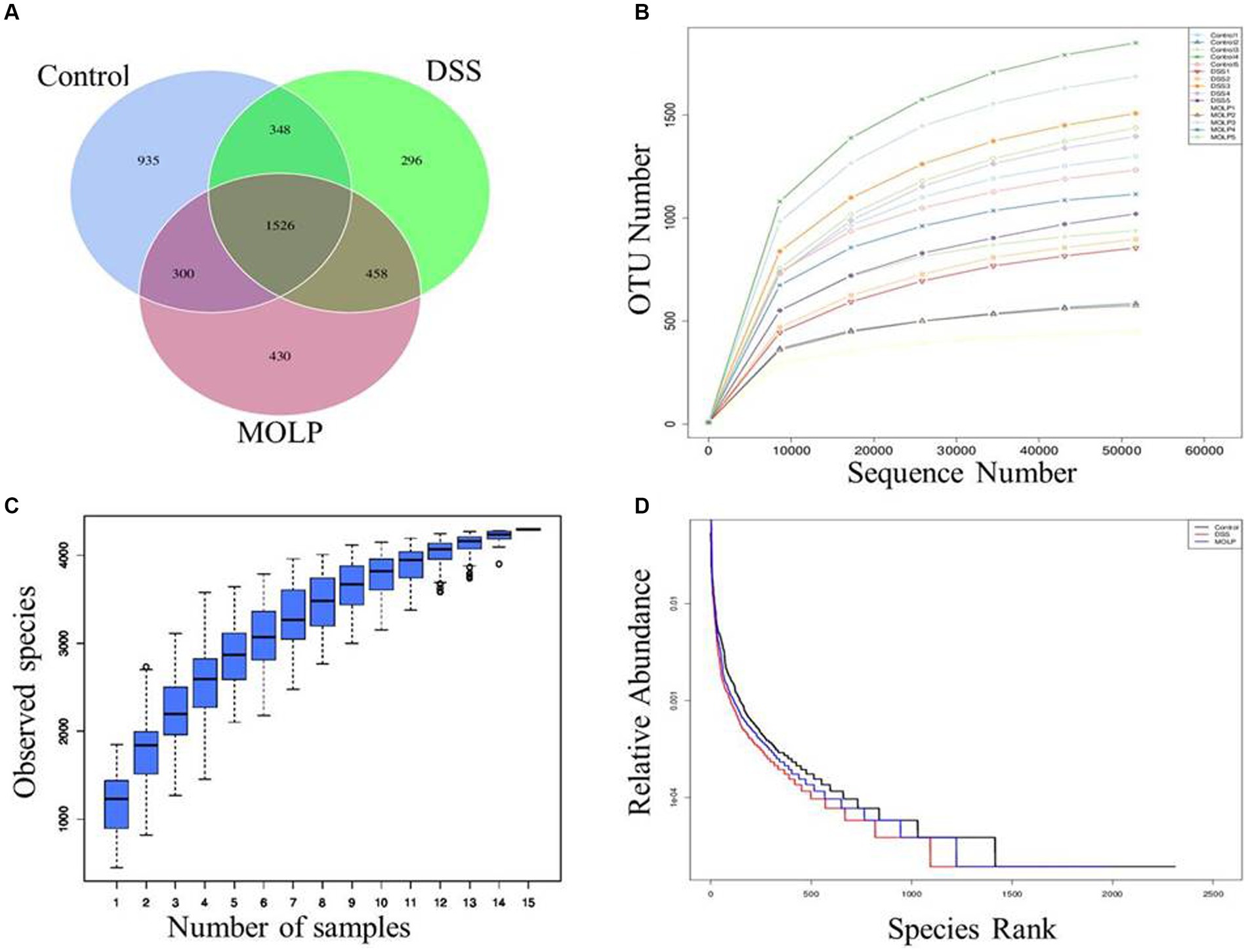

According to the Venn diagram (Figure 1A), the control, DSS, and MOLP-H groups had a total of 4,293 OTUs, with 935, 296, and 430 unique OTUs, respectively.

Figure 1. Effects of MOLP on the gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice. Venn diagram of OTUs (A), rarefaction curve (B), species accumulation curve (C) and hierarchical clustering curve (D).

The species accumulation curve progressively stabilized as sample sizes increased (Figures 1B–D); suggesting that the test samples in this study were adequate and the sequencing results were dependable.

Alpha diversity

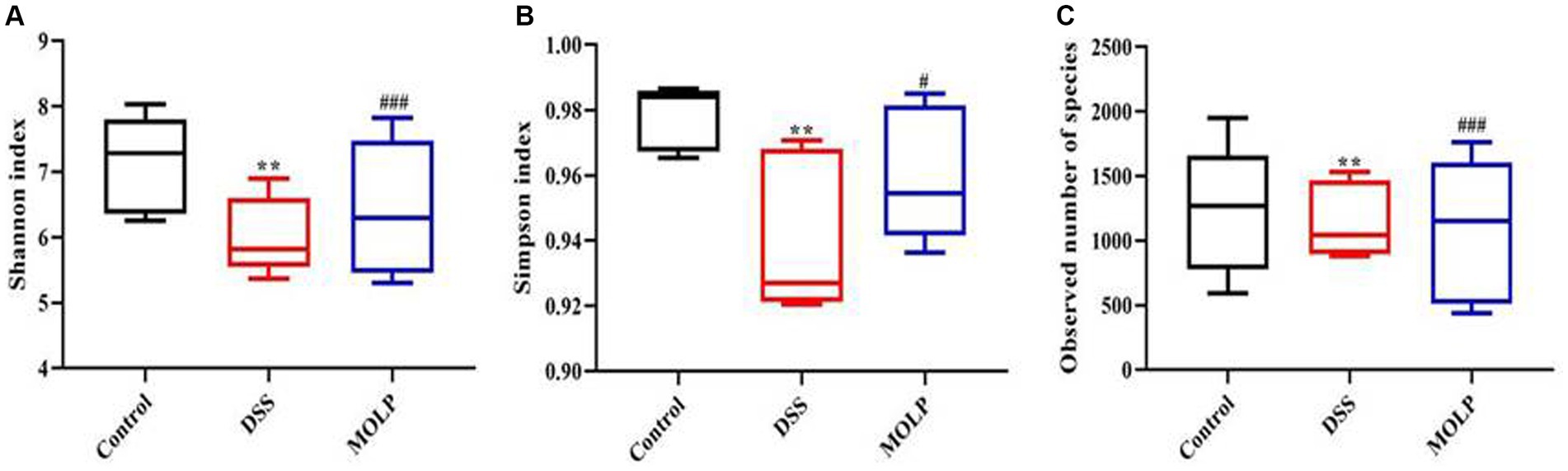

In the DSS group, the Shannon, Simpson, and observed species community richness indices were significantly lower (p < 0.01) compared with the control group. However, these indices mentioned above were increased (p < 0.05, p < 0.001) in the MOLP-H group, compared with the DSS group (Figures 2A–C). These findings demonstrated that MOLP had significant regulatory influences and that colonic mucosal flora abundance and constancy were significantly reduced in UC mice.

Figure 2. Effects of MOLP on the gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice. Shannon index (A), Simpson index (B), and observed species (C), (n = 5). **p < 0.01, DSS vs. Control; #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001, MOLP-H vs. DSS.

Beta diversity

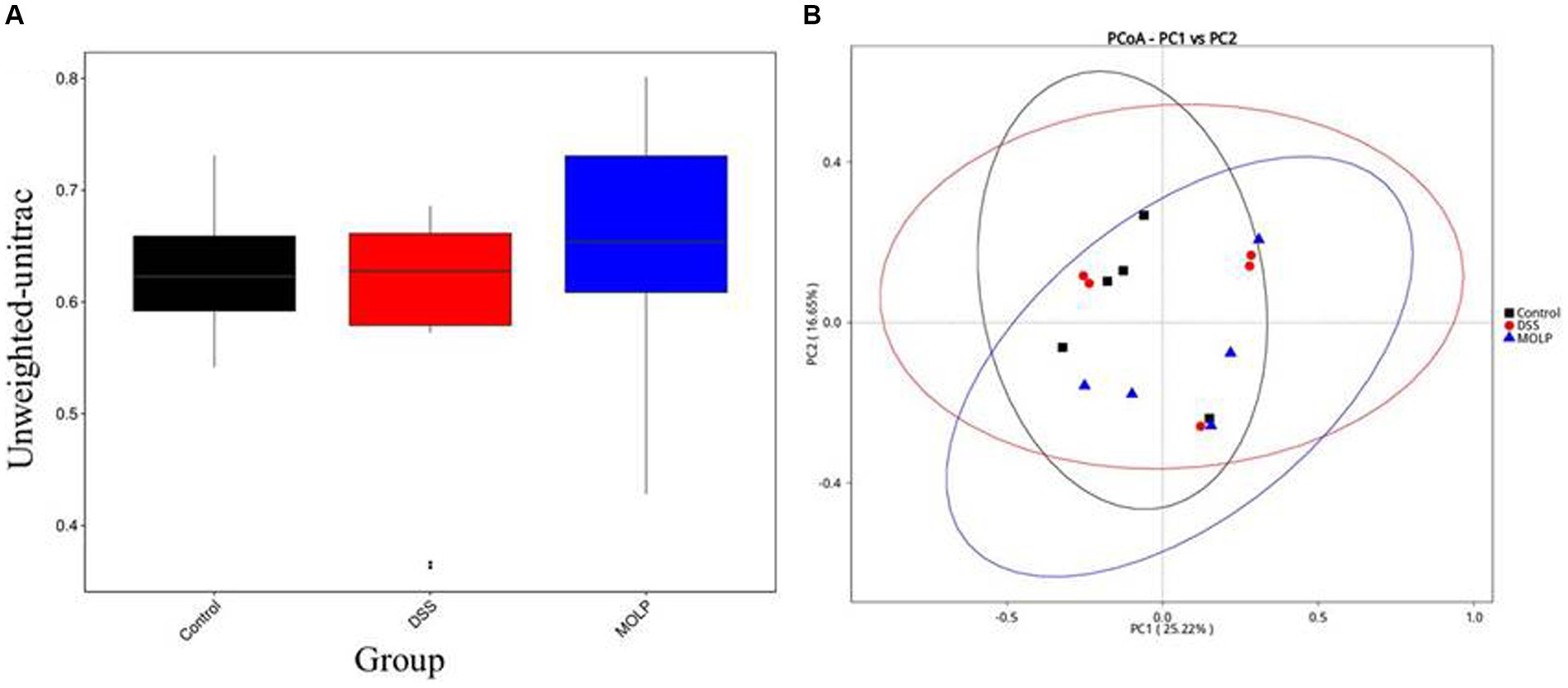

The influence of MOLP-H on the community and composition of gut microbiota was investigated using beta diversity (Figure 3A). Furthermore, PCoA demonstrated an obvious difference between the control and DSS groups, and MOLP-H treatment caused the DSS group’s intestinal microbiota to resemble that of the control group (Figure 3B). Overall, MOLP-H administration significantly altered the structural microbial diversity of the intestine in DSS-treated mice.

Figure 3. Effect of MOLP on the gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice. Beta diversity index (A), PCoA (B), (n = 5).

UPGMA

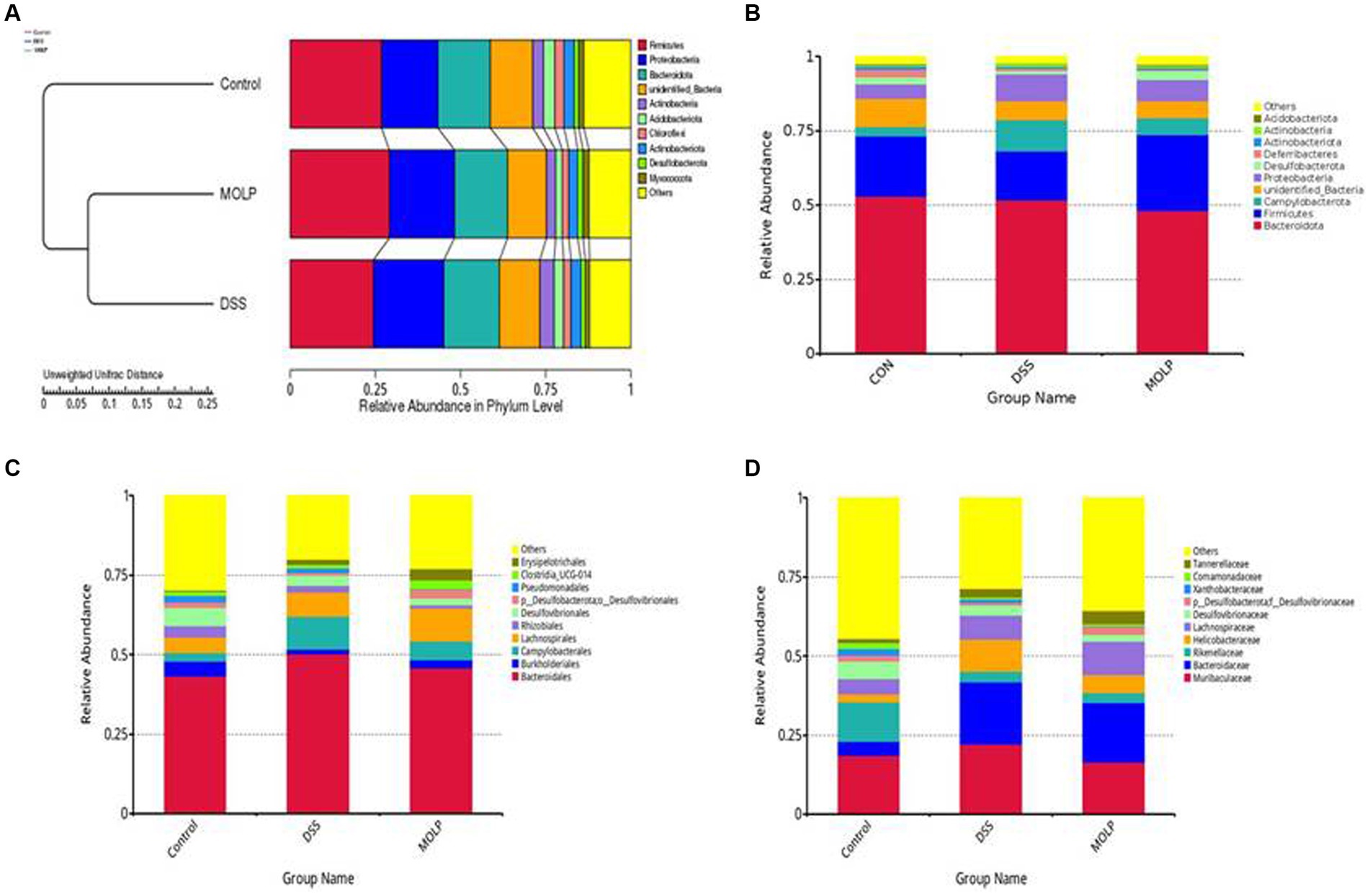

UPGMA confirmed the division of the control and DSS groups, whereas MOLP-H intervention showed a shift from the DSS to the control group (Figures 4A–D). At the phylum level, similarity analysis revealed an obvious variation between both the control and DSS groups. In contrast, there was no variation between the DSS and MOLP-H groups. These results suggest that MOLP-H can modulate but not completely restore the DSS-induced disturbance of the intestinal microbiome.

Figure 4. Effect of MOLP on the gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice. UPGMA (A), relative species richness at the phylum level (B), and relative species richness at the order level (C), and relative species richness at the family level (D), (n = 5).

MOLP enhances the beneficial bacteria in DSS-treated mice

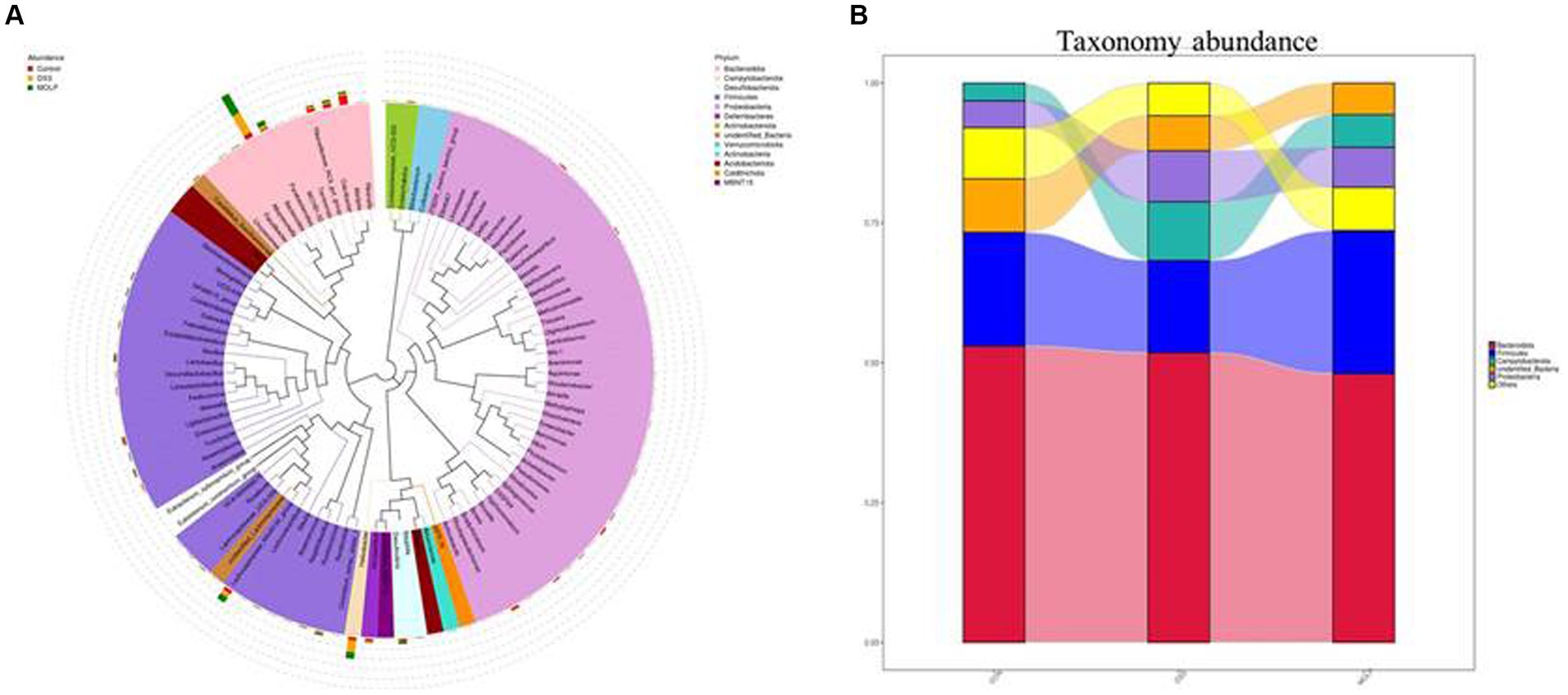

To demonstrate the existence of a link between the top 100 genera and their abundances in various groups, a phylogenetic tree has been created (Figure 5A). It was revealed that the Bacteroides, Alloprevotella, and Parabacteroides groups of Bacteroidetes, and the Lactobacillus group of Firmicutes were the dominant genera in the intestine, and their proportions can play significant roles in the symbiotic connection between the host and the gut microbiota.

Figure 5. Effect of MOLP on the gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice. Phylogenetic tree based on top 100 genera (A) and the taxonomy abundances of each group (B), (n = 5).

According to a taxonomic investigation, Firmicutes dramatically decreased in the DSS group, whereas Helicobacter increased. However, MOLP-H treatment increased Firmicutes and reduced Helicobacter in DSS-treated mice. Furthermore, DSS treatment increased Bacteroidetes, whereas MOLP-H treatment had no obvious effect on Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in DSS-treated mice (Figure 5B). These results suggested that MOLP-H may enhance the beneficial bacteria in DSS-induced UC mice.

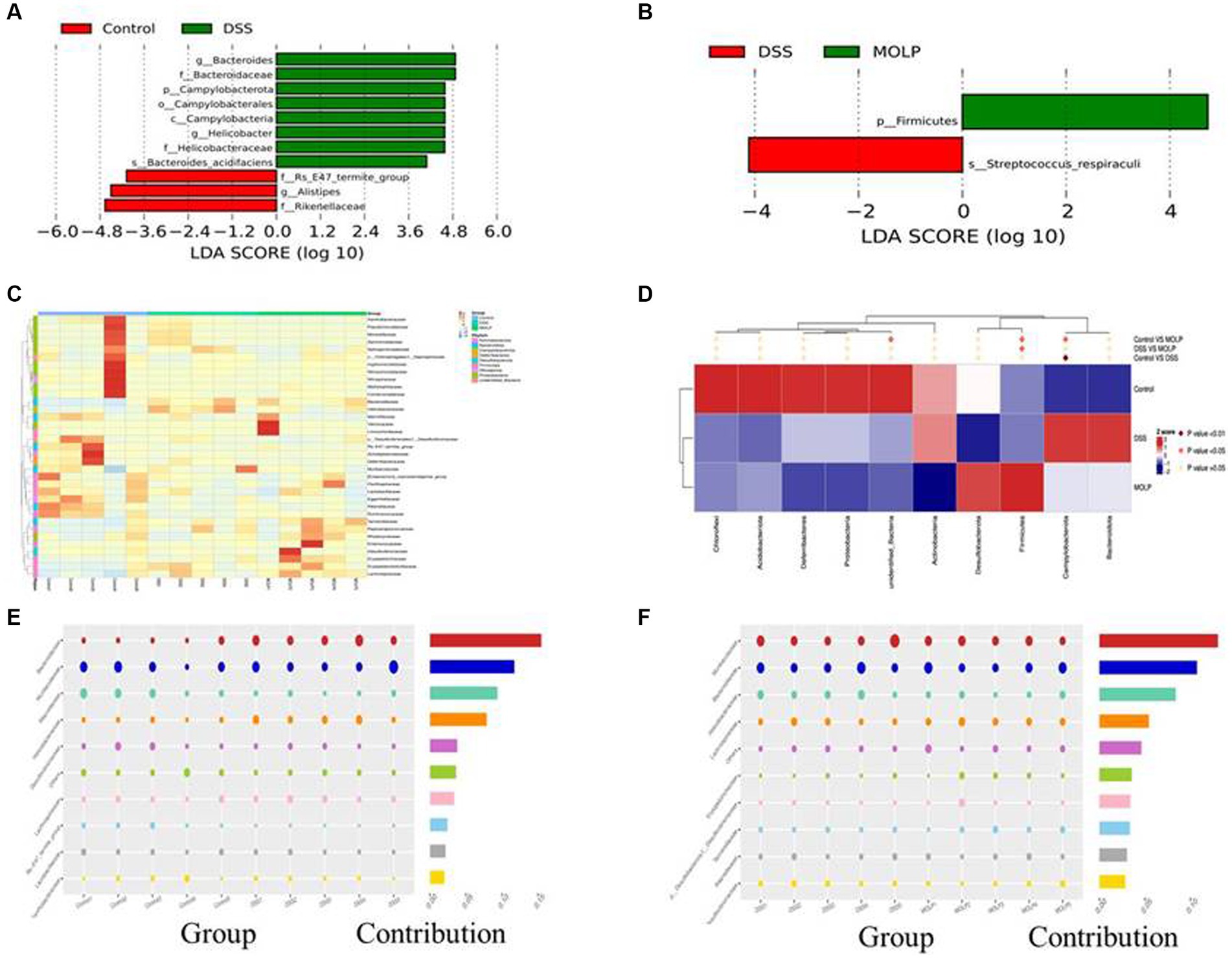

Effect of MOLP on the composition of the gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice

LEfSe demonstrated that the control and DSS groups had dominant communities of three and eight bacterial taxa, respectively. However, there was only one bacterial taxon found in the MOLP-H treatment group, indicating that an obvious variation occurred between the control, DSS, and MOLP-H groups. Bacteroides, Bacteroidaceae, Campylobacterota, Campylobacterales, Campylobacteria, Helicobacter, Helicobacteraceae, and Bacteroides-acidifaciens were dominant in the DSS group, and Rs-E47-termite-group, Alistipes, and Rikellaceae were dominant in the control group. Firmicutes was dominant in the MOLP-H group, respectively (Figures 6A,B).

Figure 6. LEfSe (score >3) was performed to determine statistically signature genera in control and DSS groups (A), MOLP and DSS groups (B). LDA score at the log10 scale is shown at the bottom. Heat map at phylum level of differential OTUs (C). Relative abundances of the top 10 bacteria at the family level (D); and bubble chart of bacterial composition at the family level of control and DSS groups (E), DSS and MOLP groups (F), (n = 5).

Effect of MOLP on the bacterial community in UC mice

The heat map graphically showed that the dominant bacterial community at phylum levels 20, 4, and 11 OTUs were obtained in the control, DSS, and MOLP-H groups, respectively. In addition, 12 and 23 differential OTUs were increased and decreased, respectively, and the result of cluster analysis shows that there were variations between the DSS and MOLP-H groups (Figure 6C). Furthermore, Helicobacter have positive correlations with UC symptoms, which markedly increased in DSS-treated mice and even decreased in the MOLP-H group (Figure 6D).

In comparison to the control group, the DSS group had lower levels of Rickenellaceae, Rs-E47-termite-group, Muribaculaceae, and Lactobacillceae and higher levels of Helicobacteraceae, and Lacnhospiraceae at the family level (Figure 6E). In contrast, MOLP-H treatment increased Muribaculaceae and Rickenellaceae levels while decreasing Helicobacteraceae levels in DSS-treated mice (Figure 6F).

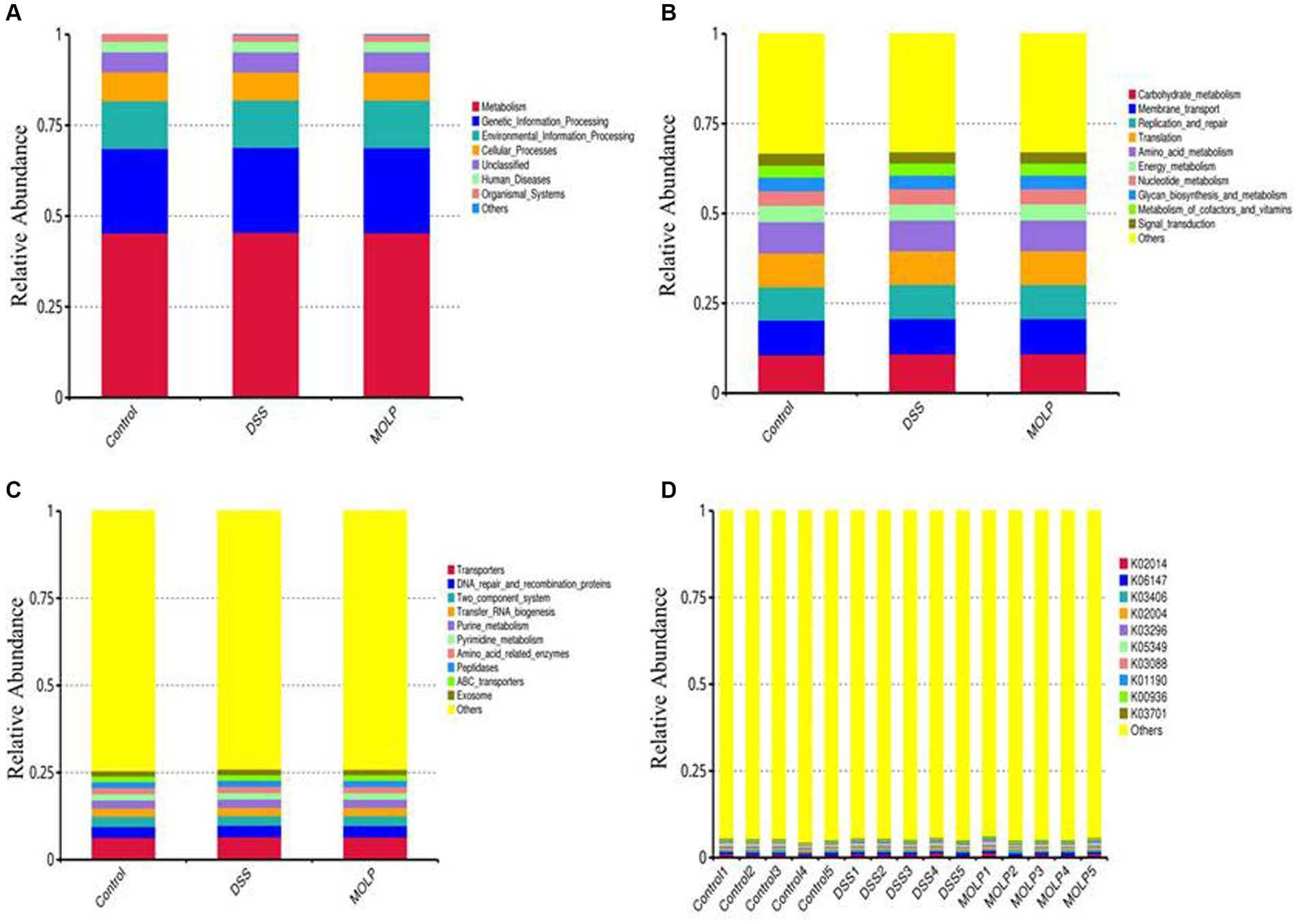

Effect of MOLP on the functional prediction of gut microbiota in DSS-treated mice

Tax4Fun performed the functional prediction of the intestinal microbiota. At the first level, metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, unclassified human diseases, and organismal systems were evaluated (Figure 7A). Carbohydrate metabolism, membrane transport, translation, replication, and repair; amino acid metabolism, energy metabolism; nucleotide metabolism; glycan biosynthesis and metabolism; metabolism of cofactors and vitamins; and signal transduction were the top 10 pathways at the second level (Figure 7B). The top 10 pathways at the third level included transporters, DNA repair and recombination proteins, two-component systems, transfer RNA biogenesis, purine metabolism, amino acid-related enzymes, peptidases, ABC transporters, and the exosome (Figure 7C). The top 10 KEGG orthologs at level K were K02014, K06147, K03406, K02004, K03296, K05349, K03088, K01190, K00936, and K03701 (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Effect of MOLP on the function prediction on colonic microbiota. First level (A), second level (B), third level (C) and KEGG orthologues level (D), (n = 5).

Discussion

The pathogenesis of UC is significantly affected by the intestinal microbiota (30, 31), and potential medicinal microbiota alterations, such as antibiotics, nutrients, food supplements, and microbiota implantation, have been demonstrated to be beneficial (32–35). Several herbal products, particularly plant foods and phytochemicals, have been shown to be useful in weight management by modifying the intestinal flora (35, 36). Our study investigated the influence of MOLP-H on the gut microbiota of mice with DSS-induced UC.

Microbial alpha diversity is regarded as a key indicator of gut health, and a high bacterial diversity indicates that the gut ecosystem is stable and resilient (37). IBD has been associated with a reduction in alpha diversity (38, 39). Our results showed that the high dose of MOLP increased the diversity indices of gut microbiota, including Shannon, Simpson, and observed species. This is in agreement with Li et al. (29) showing that crude polysaccharide extracted from MOL prevents obesity by modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed mice. Furthermore, PCoA and UPGMA showed that the intestinal microbiota in the DSS group was unique from that of the control group. However, administration of MOLP-H altered the microbiota modifications in UC mice.

The intestinal microbiota of healthy organisms is mainly composed of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. The relative abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in intestinal microorganisms can reach more than 90% (40). In addition, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the prevalent bacterial types in the digestive system, and the ratio of these two bacteria indicates the integrity and health of the intestinal lumen (41). Furthermore, Bacteroides is a significant genus in the microbiota of humans that may utilize an extensive variety of dietary polysaccharides (41, 42). IBD can cause an increase in Bacteroides as reported previously (43). According to the reports mentioned above, MOLP-H treatment can reduce the pathogenicity of IBD by decreasing the amount of Bacteroidetes in the digestive system. This is similar to a previous study that found Firmicutes was 40% more prevalent than Bacteroidetes in mice fed a high-fat diet (44). Further investigation revealed that some Bacteroidetes and a few Firmicutes species, including Bacteroides and Lactobacillus, were associated with modifications in physiological conditions in DSS-treated mice. Miranda et al. (45) reported that a reduction in Lactobacillus was correlated with an increase in UC induced by DSS. Thus, Lactobacillus is a beneficial bacterium in the gut (46), is crucial for preserving intestinal health, and stimulates the production of digestive enzymes. Its metabolites can prevent harmful bacteria from proliferating in the intestines, preserve the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier, and enhance the body’s immunity by activating the intestinal autoimmune system. Our study indicated that MOLP-H treatment increased the levels of Lactobacillus. Similar to the previous study, MO enhanced Lactobacillus levels associated with obesity following high-fat diet feeding (46). A positive correlation exists between Desulfovibrionaceae and endotoxin, which promotes inflammation (47) and may cause intestinal epithelial inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor alfa (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) to be released (48). Furthermore, Muribaculaceae is associated with natural killer cells and the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway (49). A pathogenic bacterium called Helicobacter has been linked to stomach issues, and higher levels of Helicobacter can make IBD more severe (50). Proteobacteria are strongly linked with intestinal inflammation, as evidenced by some IBD patients (51). Further immunological description reveals colitis induction with certain microbial communities or Helicobacter infection (52–54). Our study showed that MOLP treatment decreased the level of Helicobacter in DSS-treated mice. It has been suggested that the effect of MOLP on the gut microbiota may be extremely focused on some specific microbes at higher taxonomic levels.

Generally, MOLP-H treatment improves intestinal health by enhancing the number of beneficial organisms, including Firmicutes and Lactobacillus, reducing the number of pathogenic organisms, such as Helicobacter and Proteobacteria. The above findings indicated that MOLP-H can reduce the invasion of UC by inhibiting the colonization of intestinal bacteria, while modulating the abundance of Firmicutes, and suppressing the abundance of Helicobacter. This may be the reason why MOLP inhibits the pathogenicity of UC in mice.

Conclusion

Our study indicated that MOLP-H administration promoted intestinal health in DSS-induced UC mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiome. Notably, MOLP-H treatment reduced the number of pathogenic bacteria such as Helicobacter, which had increased in response to the DSS challenge and correlated positively with the symptoms of colitis. This study provides scientific evidence that MOLP is extremely useful in the field of functional foods and dietary supplements.

Data availability statement

The original data presented in this study are included in the Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted under the Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

HH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. SR: Writing – review & editing. ZD: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MW: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National 14th Five-Year Plan Key Research and Development Program (2023YFD1301705 and 2021YFD1600702), Bintuan Agricultural Innovation Project (NCG202232).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Min, L, Chi, Y, and Dong, S. Gut microbiota health closely associates with PCB153-derived risk of host diseases. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2020) 203:111041. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111041

2. Lu, D, Huang, Y, Kong, Y, Tao, T, and Zhu, X. Gut microecology: why our microbes could be key to our health. Biomed Pharmacother. (2020) 131:110784. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110784

3. Zhang, L, Gui, S, Wang, J, Chen, QR, Zeng, JL, Liu, A, et al. Oral administration of green tea polyphenols (TP) improves ileal injury and intestinal flora disorder in mice with Salmonella typhimurium infection via resisting inflammation, enhancing antioxidant action and preserving tight junction. J Funct Foods. (2020) 64:103654. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103654

4. Niu, W, Chen, X, Xu, R, Dong, H, Yang, F, Wang, Y, et al. Polysaccharides from natural resources exhibit great potential in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a review. Carbohydr Polym. (2021) 254:117189. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117189

5. Bernstein, CN . Treatment of IBD: where we are and where we are going. Am J Gastroenterol. (2015) 110:114–26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.357

6. Alex, PNC, Zachos, T, Nguyen, L, Gonzales, TE, Chen, LS, Conklin, M, et al. Distinct cytokine patterns identified from multiplex profiles of murine DSS and TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2009) 15:341–52. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20753

7. Pithadia, AB, and Jain, S. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Pharmacol Rep. (2011) 63:629–42. doi: 10.1016/S1734-1140(11)70575-8

8. Zhang, N, Ju, Z, and Zuo, T. Time for food: the impact of diet on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrition. (2018) 51–52:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.12.005

9. Xu, X, Yang, J, Ning, Z, and Zhang, X. Lentinula edodes-derived polysaccharide rejuvenates mice in terms of immune responses and gut microbiota. Food Funct. (2015) 6:2653–63. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00689a

10. Richardson, JB, Dancy, BCR, Horton, CL, Lee, YS, Madejczyk, MS, Xu, ZZ, et al. Exposure to toxic metals triggers unique responses from the rat gut microbiota. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:6578. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24931-w

11. Vieira, AT, Macia, L, Galvão, I, Martins, FS, Canesso, MC, Amaral, FA, et al. A role for gut microbiota and the metabolite-sensing receptor GPR43 in a murine model of gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2015) 67:1646–56. doi: 10.1002/art.39107

12. Harsch, IA, and Konturek, PC. The role of gut microbiota in obesity and type 2 and type 1 diabetes mellitus: new insights into “old” diseases. Med Sci. (2018) 6:32. doi: 10.3390/medsci6020032

13. Chen, X, Zheng, L, Zheng, YQ, Yang, QG, Lin, Y, Ni, FH, et al. The cardiovascular macrophage: a missing link between gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2018) 22:1860–72. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201803_14607

14. Ohshima, T, Kojima, Y, Seneviratne, CJ, and Maeda, N. Therapeutic application of synbiotics, a fusion of probiotics and prebiotics, and biogenics as a new concept for oral candida infections: a mini review. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00010

15. Pandey, KR, Naik, SR, and Vakil, BV. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics—a review. J Food Sci Technol. (2015) 52:7577–87. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1921-1

16. Adisakwattana, S, and Chanathong, B. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity and lipid-lowering mechanisms of Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2011) 15:803–8.

17. Yassa, HD, and Tohamy, AF. Extract of Moringa oleifera leaves ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus in adult rats. Acta Histochem. (2014) 116:844–54. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2014.02.002

18. Jaiswal, D, Kumar Rai, P, Kumar, A, Mehta, S, and Watal, G. Effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. leaves aqueous extract therapy on hyperglycemic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. (2009) 123:392–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.036

19. Liao, N, Zhong, J, Ye, X, Lu, S, Wang, W, Zhang, R, et al. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction of polysaccharide from Corbicula fluminea: characterization and antioxidant activity. Food Sci Technol. (2015) 60:1113–21. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2014.10.009

20. Nardos, A, Makonnen, E, and Debella, A. Effects of crude extracts and fractions of Moringa stenopetala (Baker f) Cufodontis leaves in normoglycemic and alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Afr J Pharm. (2011) 5:2220–5. doi: 10.5897/AJPP11.318

21. Liu, CJ, and Lin, JY. Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of strawberry and mulberry fruit polysaccharides on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages through modulating pro-/anti-inflammatory cytokines secretion and Bcl-2/Bak protein ratio. Food Chem Toxicol. (2012) 50:3032–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.06.016

22. Tian, CY, Bo, HM, and Li, JA. Influence of Mori fructus polysaccharide on blood glucose and serum lipoprotein in rats with experimental type 2 diabetes. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae. (2011) 10:049.

23. Tan, M, Chang, S, Liu, J, Li, H, Xu, P, Wang, P, et al. Physicochemical properties, antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of polysaccharides from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) seeds. Molecules. (2020) 25:3840. doi: 10.3390/molecules25173840

24. Zhang, ZP, Shen, CC, Gao, FL, Wei, H, Ren, DF, and Lu, J. Isolation, purification and structural characterization of two novel water-soluble polysaccharides from Anredera cordifolia. Molecules. (2017) 22:1276. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081276

25. Mohamed, HH, Peng, W, Su, H, Zhou, R, Tao, Y, Huang, J, et al. Moringa oleifera leaf polysaccharide alleviates experimental colitis by inhibiting inflammation and maintaining intestinal barrier. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:1055791. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1055791

26. Ji, XL, Guo, JH, Tian, JY, Ma, K, and Liu, Y. Research progress on degradation methods and product properties of plant polysaccharides. J Light Ind. (2023) 38:55–62. doi: 10.12187/2023.03.007

27. Zhang, YJ, Zhang, LX, Yang, JF, and Liang, ZY. Structure analysis of water-soluble polysaccharide CPPS3 isolated from Codonopsis pilosula. Fitoterapia. (2010) 81:157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.08.011

28. Edgar, RC . UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. (2013) 10:996–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

29. Li, L, Ma, L, Wen, Y, Xie, J, Yan, L, Ji, A, et al. Crude polysaccharide extracted from Moringa oleifera leaves prevents obesity in association with modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed mice. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:861588. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.861588

30. Hold, GL, Smith, M, Grange, C, Watt, ER, El-Omar, EM, and Mukhopadhya, I. Role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: what have we learnt in the past 10 years. World J Gastroenterol. (2014) 20:1192–210. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1192

31. Tremaroli, V, and Bäckhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. (2012) 489:242–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11552

32. Gionchetti, P, Rizzello, F, Venturi, A, Brigidi, P, Matteuzzi, D, Bazzocchi, G, et al. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. (2000) 119:305–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9370

33. Grimm, V, and Riedel, CU. Manipulation of the microbiota using probiotics. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2016) 902:109–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31248-4_8

34. Haifer, C, Leong, RW, and Paramsothy, S. The role of faecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. (2020) 55:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2020.08.009

35. Wang, P, Cai, M, Yang, K, Sun, P, Xu, J, Li, Z, et al. Phenolics from Dendrobium officinale leaf ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced chronic colitis by regulating gut microbiota and intestinal barrier. J Agric Food Chem. (2023) 71:16630–46. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c05339

36. Weng, G, Duan, Y, Zhong, Y, Song, B, Zheng, J, Zhang, S, et al. Plant extracts in obesity: a role of gut microbiota. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:727951. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.727951

37. Lloyd-Price, J, Abu-Ali, G, and Huttenhower, C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. (2016) 8:51. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y

38. Franzosa, EA, Sirota-Madi, A, Avila-Pacheco, J, Fornelos, N, Haiser, HJ, Reinker, S, et al. Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. (2019) 4:293–305. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0306-4

39. Huttenhower, C, Kostic, AD, and Xavier, RJ. Inflammatory bowel disease as a model for translating the microbiome. Immunity. (2014) 40:843–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.013

40. Arumugam, M, Raes, J, Pelletier, E, Le Paslier, D, Yamada, T, Mende, DR, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. (2011) 473:174–80. doi: 10.1038/nature09944

41. Ji, XL, Chun, YH, Yong, GG, Yu, QX, Yi, ZY, and Xu, DG. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota modulatory effects of jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) polysaccharides in a colorectal cancer mouse model. Food Funct. (2020) 11:163–73. doi: 10.1039/c9fo02171j

42. Sang, T, Guo, C, Guo, D, Wu, J, Wang, Y, Wang, Y, et al. Suppression of obesity and inflammation by polysaccharide from sporoderm-broken spore of Ganoderma lucidum via gut microbiota regulation. Carbohydr Polym. (2021) 256:117594. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117594

43. Guo, C, Wang, Y, Zhang, S, Zhang, X, Du, Z, Li, M, et al. Crataegus pinnatifida polysaccharide alleviates colitis via modulation of gut microbiota and SCFAs metabolism. Int J Biol Macromol. (2021) 181:357–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.03.137

44. Do, MH, Lee, HB, Oh, MJ, Jhun, H, Choi, SY, and Park, HY. Polysaccharide fraction from greens of Raphanus sativus alleviates high fat diet-induced obesity. Food Chem. (2021) 343:128395. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128395

45. Miranda, PM, De Palma, G, Serkis, V, Lu, J, Louis-Auguste, MP, McCarville, JL, et al. High salt diet exacerbates colitis in mice by decreasing Lactobacillus levels and butyrate production. Microbiome. (2018) 6:57. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0433-4

46. Elabd, EMY, Morsy, SM, and Elmalt, HA. Investigating of Moringa oleifera role on gut microbiota composition and inflammation associated with obesity following high fat diet feeding. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. (2018) 6:1359–64. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.313

47. Nakamura, S, Kuda, T, Midorikawa, Y, Takahashi, H, and Kimura, B. Typical gut indigenous bacteria in ICR mice fed a soy protein-based normal or low-protein diet. Curr Res Food Sci. (2021) 4:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2021.04.001

48. Liu, Y, Ma, Y, Chen, Z, Zou, C, Liu, W, Yang, L, et al. Depolymerized sulfated galactans from Eucheuma serra ameliorate allergic response and intestinal flora in food allergic mouse model. Int J Biol Macromol. (2021) 166:977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.254

49. Huang, K, Yan, Y, Chen, D, Zhao, Y, Dong, W, Zeng, X, et al. Ascorbic acid derivative 2-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-l-ascorbic acid from the fruit of Lycium barbarum modulates microbiota in the small intestine and colon and exerts an immunomodulatory effect on cyclophosphamide-treated BALB/c mice. J Agric Food Chem. (2020) 68:11128–43. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04253

50. Li, P, Xiao, N, Zeng, L, Xiao, J, Huang, J, Xu, Y, et al. Structural characteristics of a mannoglucan isolated from Chinese yam and its treatment effects against gut microbiota dysbiosis and DSS-induced colitis in mice. Carbohydr Polym. (2020) 250:116958. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116958

51. He, X, Liu, J, Long, G, Xia, XH, and Liu, M. 2,3,5,4'-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-D-glucoside, a major bioactive component from Polygoni multiflori Radix (Heshouwu) suppresses DSS induced acute colitis in BALb/c mice by modulating gut microbiota. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 137:111420. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111420

52. Roy, U, Gálvez, EJC, Iljazovic, A, Lesker, TR, Błażejewski, AJ, Pils, MC, et al. Distinct microbial communities trigger colitis development upon intestinal barrier damage via innate or adaptive immune cells. Cell Rep. (2017) 21:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.097

53. Kullberg, MC, Ward, JM, Gorelick, PL, Caspar, P, Hieny, S, Cheever, A, et al. Helicobacter hepaticus triggers colitis in specific-pathogen-free interleukin-10 (IL-10)-deficient mice through an IL-12- and gamma interferon-dependent mechanism. Infect Immun. (1998) 66:5157–66. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.11.5157-5166.1998

Keywords: Moringa oleifera leaf, polysaccharide, DSS, ulcerative colitis, intestinal microbiota

Citation: Husien HM, Rehman SU, Duan Z and Wang M (2024) Effect of Moringa oleifera leaf polysaccharide on the composition of intestinal microbiota in mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis. Front. Nutr. 11:1409026. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1409026

Edited by:

Xiaolong Ji, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, ChinaReviewed by:

Weidong Deng, Yunnan Agricultural University, ChinaChen Zheng, Gansu Agricultural University, China

Weiguo Zhao, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2024 Husien, Rehman, Duan and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenyu Duan, MTA4Njg5MDA5QHFxLmNvbQ==; Mengzhi Wang, bWVuZ3poaXdhbmd5ekAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Hosameldeen Mohamed Husien

Hosameldeen Mohamed Husien Shahab Ur Rehman

Shahab Ur Rehman Zhenyu Duan3*

Zhenyu Duan3* Mengzhi Wang

Mengzhi Wang