95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Nutr. , 01 February 2024

Sec. Clinical Nutrition

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1270048

This article is part of the Research Topic Nutritional Counseling for Lifestyle Modification View all 9 articles

Lenycia de Cassya Lopes Neri1,2

Lenycia de Cassya Lopes Neri1,2 Monica Guglielmetti1,2

Monica Guglielmetti1,2 Simona Fiorini1,2*

Simona Fiorini1,2* Federica Quintiero1,2

Federica Quintiero1,2 Anna Tagliabue2

Anna Tagliabue2 Cinzia Ferraris1,2

Cinzia Ferraris1,2Healthy eating habits are the basis for good health status, especially for children and adolescents, when growth and development are still ongoing. Nutrition educational programs are essential to prevent and treat chronic diseases. Nutritional counseling (NC), as a collaborative process between the counselor and the client process, could help to achieve better outcomes. This review aims to collect information about the utilization of NC during childhood and adolescence and to highlight its possible impact on adherence/compliance rates, nutrition knowledge, status and dietary intake. The methods applied in this systematic review followed the instruction of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The search in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, LILACS, and Science Direct included observational or randomized studies. RoB 2.0 and Robins-I tools was used for the risk of bias assessment in randomized and non-randomized studies, respectively. The quality of evidence was checked by the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool system. A total of 21 articles were selected, computing 4,345 individuals. 11 achieved at least 4 stars quality level. The highest risk of bias for randomized studies was related to the randomization process. 42.9% of non-randomized studies had some concerns of bias, mainly because of a lack of control of all confounding factors. Different strategies of NC were used in children and adolescents with positive results for health or diseases. NC strategies can be effectively used in children and adolescents. In general, NC showed benefits in pediatrics age for anthropometric or body composition parameters, dietary intake, nutrition knowledge and physical activity improvement. Performing NC in pediatrics is challenging due to the counseling strategies that must be adapted in their contents to the cognitive ability of each age. More structured research must be done focused on this population. Investments in healthy eating behaviors in pediatrics can lead to better health outcomes in the future population with substantial benefits to society.

Systematic review registration: [https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#recordDetails], identifier [CRD42022374177].

According to a recent publication from United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank Group malnutrition is spread among children worldwide. In particular, 144 million children under 5 years-old were classified as stunting, 47 million as wasted and 38.3 million were overweight (1). In 2017, the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and WHO expert committee on food additives reported that less than half of pediatric rural communities worldwide meet the dietary requirements for any food group (2). Thus, globally, children are not achieving the dietary recommendations.

The dietary patterns and eating behavior have important implications, especially for preventing chronic diseases or syndromes, such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers and chronic respiratory diseases (3).

Eating habits are considered modifiable behavioral risk factors for chronic diseases. A good eating habit, as part of a lifestyle, is among the multiple interacting factors of an overall good health status. The two main contributing factors are (i) biological (internal influence, for example, genetic predisposition) and (ii) psychosocial aspects (external or environmental influence) (2). These factors must be considered when choosing an intervention for delivering nutritional care (4). Special attention must be given during childhood and adolescence, when nutritional intervention could favor a voluntary adoption of healthier eating habits and behaviors, leading to good health and quality of life (5). In these phases, the importance of studying good instruments of intervention increases, in order to face the challenges experienced during childhood (parental habits, family adherence) and adolescence (emotional and psychological changes during this phase).

Appropriate care and optimal feeding practices during the pregnancy and first 2 years of life, considered the first 1,000 days, can also prevent undernutrition and reduce morbidity and mortality during childhood worldwide. Nutrition interventions in this phase could be considered a great opportunity to construct health benefits even during adulthood (6). Adolescence is also a particular life phase marked by physical and social changes and the development of individuality and identity (7). There are some nutritional difficulties such as delivering a healthy diet and the eminence of the burden of obesity or eating disorders. Optimal nutrition is also essential to improve outcomes in children with diseases, in order to establish and maintain good health. It is essential to deliver nutritional information in a way to change lifestyles and produce health outcomes in the long term (8).

Nutritional counseling (NC) is a process of collaboration between the counselor (i.e., the healthcare professional) and the client (i.e., the patient) to establish priorities, goals, and action plans in nutrition and physical activity (4). Only a few articles included a whole perspective of applying the theory or model of NC (such as Cognitive Behavioral Theory, Transtheoretical Model, Social Cognitive Theory) directly for the pediatric population. These theories support several strategies, for example, self-monitoring, problem solving, motivational interviewing, goal setting and others (4).

Recent reviews supported the use of NC (9) in healthy athletes (10) or in cases of diseases, such as cancer (11) or other chronic conditions (4). To the best of our knowledge, no publications reviewed the use of NC in the pediatric age group.

This review aims to collect information about the utilization of NC during childhood and adolescence and to highlight its possible impact on adherence/compliance rates, nutrition knowledge, status and dietary intake.

The methods applied in this systematic review followed the instruction of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, LILACS, and Science Direct were used to carry out the articles search. The languages allowed were English, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish, according to the capability of comprehension of the authors. No time limit was considered since no reviews had been made with this approach before.

Interventional trials, observational studies, case reports, and case series were included, independently of whether they were controlled, randomized or not. Exclusion criteria were: full text unavailable, manuscripts without the outcomes of interest; reviews, opinion articles, guidelines, letters, editorials, comments, news, conference abstracts, theses, dissertations, and in vitro or animal studies. Articles regarding the children’s health in which the addressees of the NC were adults or elderly were also excluded.

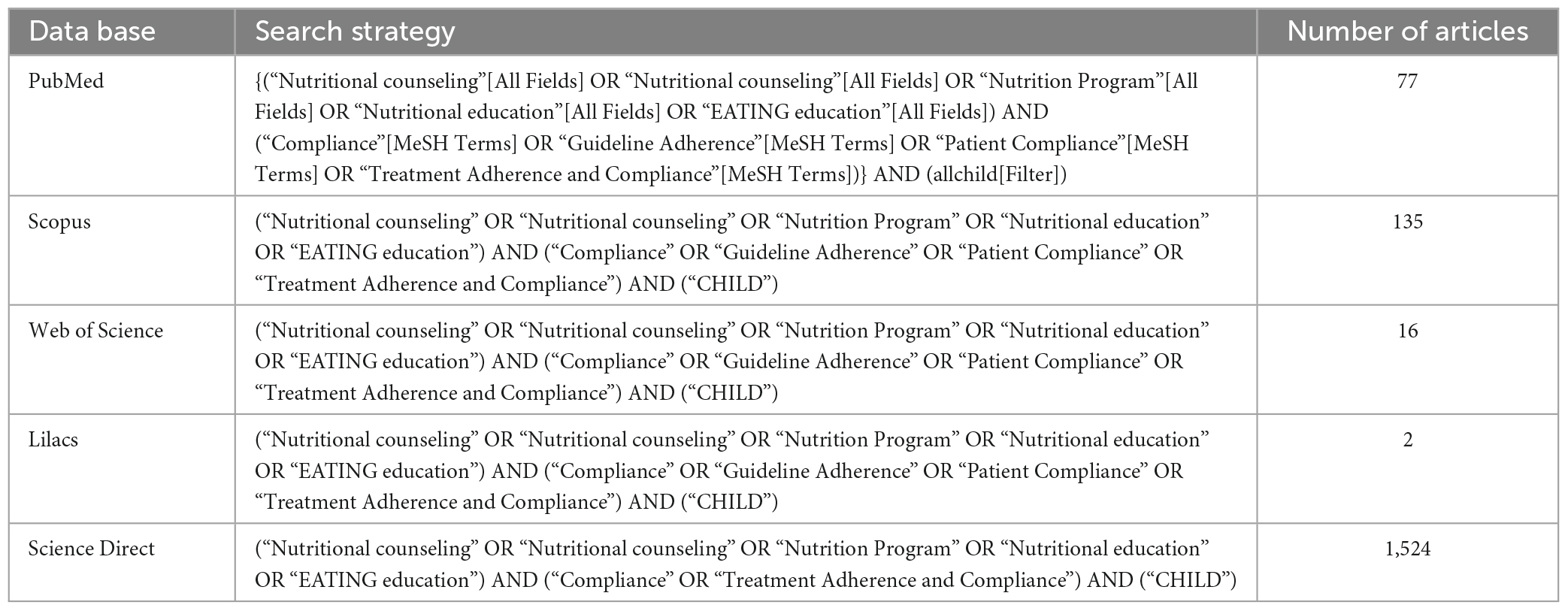

The terms used for the electronic search were “Nutritional counseling” OR “Nutritional counseling” OR “Nutritional and eating education” OR “Nutritional program,” combined with the terms “Compliance,” “Guideline Adherence,” “Patient Compliance,” OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance.” The final search was built as shown in Table 1. In case of recommendation from experts, gray literature was searched using Google Scholar and the articles were manually included. The population involved in this review was restricted to pediatric age (0–18 years old) and the comparison was any traditional dietary advice strategy. Detailed criteria for inclusion and exclusion are described in Table 2.

Table 1. Search strategy according to the database and numeric initial results in number of articles.

The discrimination of the included or excluded articles was independently carried out by two authors (LN and SF). The process of study selection was carried out using the Rayyan software (12), following three steps: 1–reading the titles and abstracts; 2–evaluation of the full text articles selected and 3–if relevant, inclusion of other studies present in the references of the selected articles. The study selection process was based on the PICOS strategy [Population (P): children and adolescents, Intervention (I): nutritional counseling strategies, Control (C): standard dietary treatment, Outcome (O): adherence/compliance rates/nutrition knowledge, Study type (S): randomized controlled trials; uncontrolled observational studies; case reports and case series]. These were considered the inclusion criteria to select titles and abstracts. All the potentially relevant abstracts were obtained in full-text version in order to verify the inclusion. In case of disagreement between the two authors during the blind process of selection, a third author analyzed the full-text articles for the final decision (CF). Subsequently, some articles were added manually, as they were relevant to the search. The selected studies were included in the qualitative analysis.

The risk of bias of each selected article was evaluated by two authors independently (LN and FQ) using the RoB 2.0 Cochrane tool for randomized studies (13). Five domains were analyzed: (1) randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported result(s). The Robins-I tool (14) was used for non-randomized studies, checking 7 domains at pre-intervention (bias due to confounding, or in the selection of participants into the study), intervention (bias in classification of interventions) and post-intervention (biases due to: deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result). Funding was analyzed in order to detect possible bias in publication (Supplementary Material 1).

Beyond the risk of bias evaluation, the quality of evidence was also checked by two authors independently (LN and FQ) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMTA) system (version 2018) (15). The decision of discrepancies was made by a third author (SF). Data about studies’ samples characteristics, design, intervention, results, and quality were extracted and presented in tables.

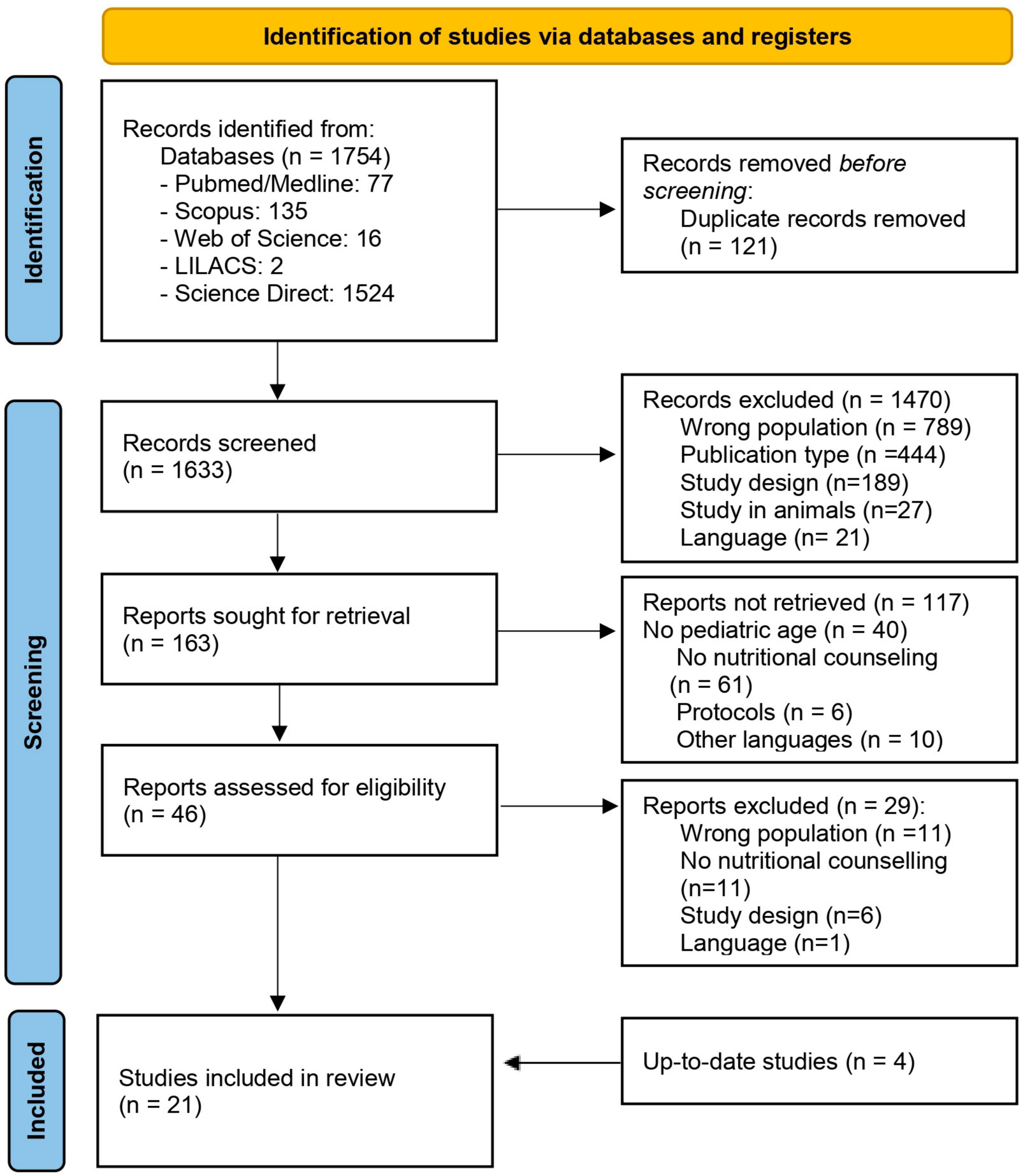

The search strings were applied to various databases, obtaining 1,754 results. The selection process and the number of articles retained at each stage are described in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). Following this process, 21 articles were selected, including a total of 4,345 pediatric patients (sample size ranged from 7 to 1,159). Studies in which NC was not directed to children or adolescents (16–20) or the intervention was not truly NC (21–26) were excluded. Further details for each of the chosen articles are outlined in Table 3, in which the studies are grouped according to the absence (27–33) or presence of randomization (27–46). Two articles (32, 46) were classified as randomized trials because there is randomization mentioned in methods, despite these being classified as non-randomized trials in the registration into the clinical trials platform.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the selection process for identified records from databases. From: Page et al. (59).

All studies were published between 1990 and 2022 in different countries: United States of America (n = 10) (27, 29–31, 34–36, 39, 42, 47), China (n = 2) (43, 45), Korea (n = 2) (32, 46), Netherlands (n = 1) (37), Brazil (n = 1) (38), Switzerland (n = 1) (28), Mexico (n = 1) (33), Italy (n = 1) (40). One study was conducted in the United Kingdom and Canada (44) and one study in the USA and Canada (41).

The duration of interventions ranged from 6 weeks up to 1 year. Most of the selected studies (47.6%) focused mainly on the overweight or obese population (28–30, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41, 44, 46). Some of the articles (23.8%) evaluated individuals with chronic diseases [hypertension (35), cystic fibrosis (34, 47), dyslipidemia (27), or risk for diabetes type 2 (30)]. Seven articles (33.3%) were focused on students (31, 33, 38, 40, 42, 43, 45). The interventions were conducted by different figures: multidisciplinary team (n = 6) (30, 32–34, 37, 47), nutrition professional (dietitian, nutritionist) (n = 5) (35, 38, 41, 44, 46), nutrition professional with another health professional (physician, nurse, exercise therapist or social worker) (n = 3) (28, 29, 39), and other figures (n = 4) (31, 36, 40, 42). In 3 studies the counselor was not specified (27, 43, 45).

The majority of the studies did not mention any theory to embase the NC (n = 10, 47.6%) (28, 29, 32, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 46, 47). In the remaining studies, NC interventions were mainly based on: Social Cognitive Theory (n = 7, 33.3%) (27, 30, 33, 36, 42, 43, 45), Self Determination Theory (n = 3, 14.3%) (30, 42, 44) and Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (n = 2, 9.5%) (31, 39).

The outcomes also varied between studies, some of them reporting several outcomes. Ten studies (47.6%) described anthropometric or body composition changes (28–30, 32, 34, 37, 44–47), six studies (28.6%) investigated dietary intake (31, 35, 38, 40, 41, 46) three studies (14.3%) evaluated nutrition knowledge (36, 39, 43) or physical activity changes, reporting positive (30, 31) or negative results (42). Other outcomes studied were self-efficacy or coping skills (27, 30) and efficacy of a program planners tool to design interventions (33).

Most of the studies (n = 12, 57.1%) (28, 30–32, 34–36, 39, 40, 42, 43, 46) did not show adherence or compliance rates for the interventions, while two publications reported lack of adherence (41) or no changes in the adherence or behavioral compliance scale (47). Two articles cited improved compliance as a result of behavioral treatment, but without mentioning the rates (34, 46) mentioned significant results in compliance rates, using low-density lipoprotein cholesterol changes (27) or frequency of food consumption (38). High adherence rates, varying from 59.2 to 100%, were found in 4 studies (33, 37, 44, 45).

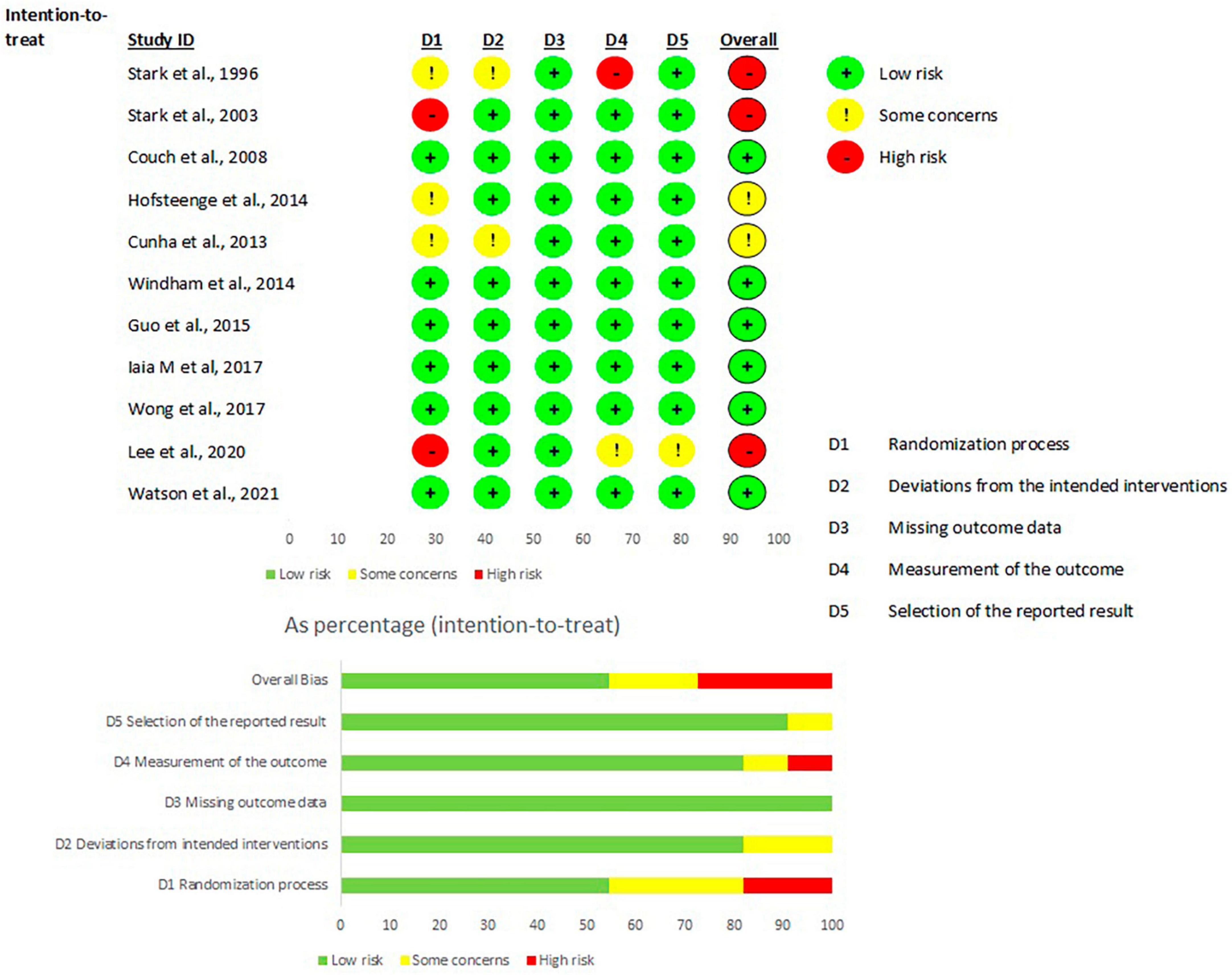

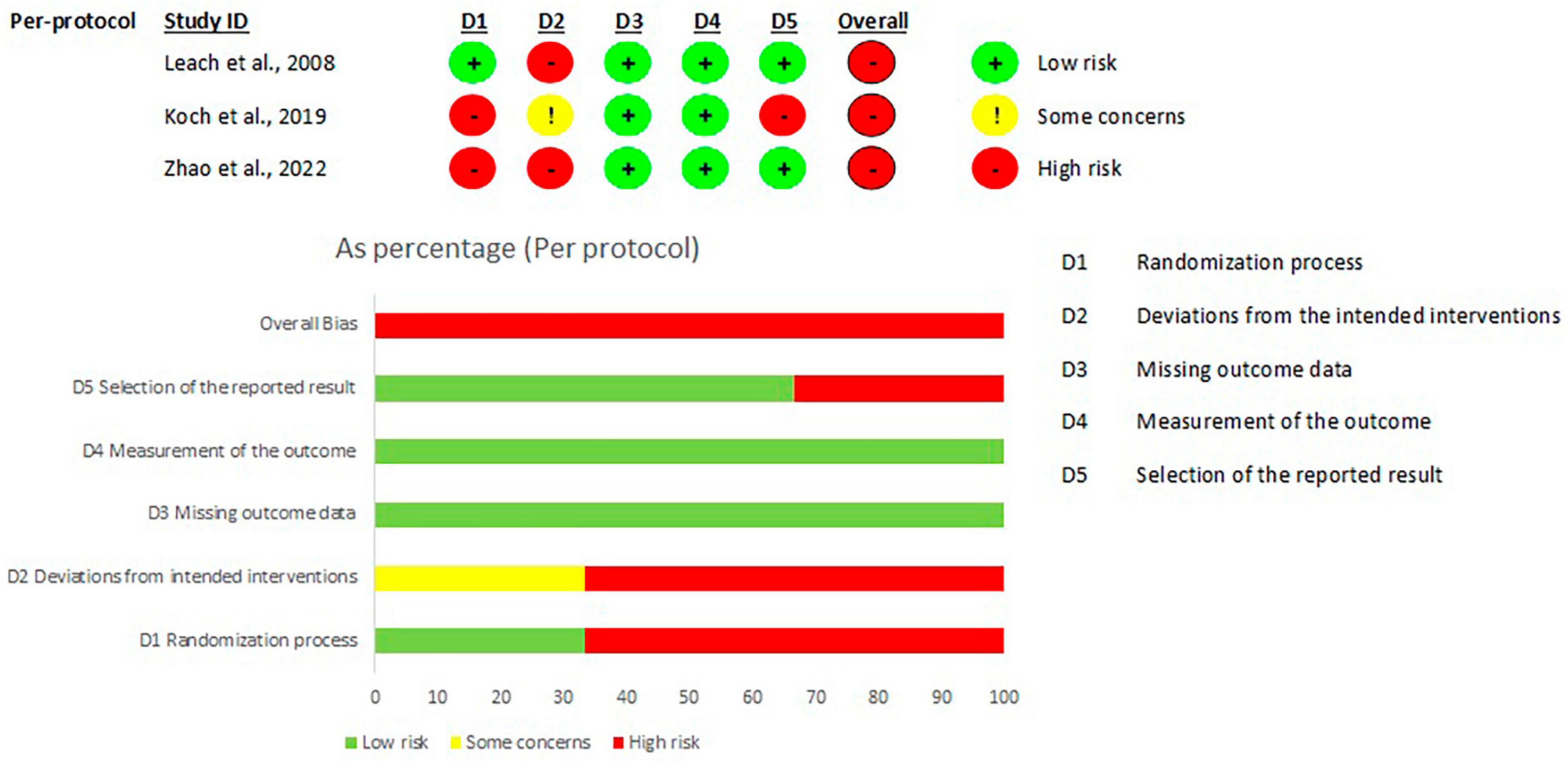

The randomized trials were divided according to the type of study analysis: 11 intention-to-treat (Figure 2) studies and 3 per-protocol articles (Figure 3). The highest risk of bias for both analyses was in domain 1 (D1), which is related to the randomization process. Conversely, the lowest risk of bias for all studies was in domain 3 (missing outcome data). In domain 4 (i.e., measurement of the outcome), one study presented a high risk of bias (34) and in domain 5 (selection of the reported result) another study (42) presented a high risk of bias. Of the 11 studies included in the intention-to-treat analysis, 6 articles had a low risk of bias, while all the 3 per protocol studies had a high risk of bias. The analysis of the risk of bias for the non-randomized studies (shown in Figure 4) showed that 5 studies had some concerns, mainly because of: (i) a lack of control of all confounding factors (domain 1), (ii) selection of participants (domain 3) and (iii) missing data (domain 5). Only one study presented a low risk of bias (28) and only one (31) was classified with a high risk of bias due to possible bias in the selection of the sample.

Figure 2. Risk of bias per articles intention-to-treat analysis, according to Rob2 tool. From: Sterne et al. (13).

Figure 3. Risk of bias per articles per protocol analysis, according to Rob2 tool. From: Sterne et al. (13).

Figure 4. Risk of bias per non-randomized studies, according to Robins tool. From: Created by authors based on Sterne et al. (14).

The results of the quality of evidence tested by MMAT (15) are reported in Table 3. Ten studies reached three stars (28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36, 42–44, 46), nine studies (27, 29, 32, 35, 37, 38, 40, 45, 47) were evaluated with four stars, and two studies reached the maximum level of five stars (39, 41).

No bias was detected in analyzing the funding sources from selected articles ((Supplementary Material 1).

Although few articles (n = 9) referred to general adherence or compliance rates, some articles reported significant (38), good (29) or great (33) compliance. Adherence and compliance rates ranged from 59% (37) to 100% (33). Otherwise, some studies reported similar compliance rates between intervention and control groups (34, 44, 45) or even lack of adherence (41). Hanna et al. (27) noted that adolescents were able to cope with temptations and better adhere to diet plans.

Data regarding nutritional status and body composition were reported in 16 studies (76.2%). Watson et al. (44) described improvements in body composition, while Knöpfli et al. (28) and Stark et al. (34, 47) illustrated a reduction or increase in body weight in patients with cystic fibrosis, respectively. Improvements in BMI were noted in some articles (29, 30, 37, 45, 46), but others did not point out the same benefits (32, 36, 38–40, 42).

Energy intake increased in patients with cystic fibrosis (34, 47). Improvements of dietary habits (31) and quality of diet (46) were reported in selected studies. The main improvements were: (i) increased fruit consumption (35, 38, 40), (ii) decreased total fat and/or increase in low fat dairy products consumption (35), (iii) reduced sugared beverages or foods consumption (38, 42) and (iv) water intake increment (41).

Improvements in nutrition knowledge were reported in some articles (36, 43). Windham et al. (39), described a better comprehension of obesity-related morbidities by parents, while Pierce et al. (31) noted an enhancement in self-efficacy, knowledge and skills in the intervention group.

This systematic review gathered current evidence on the use of NC in childhood and adolescents and emphasized the potential benefits on adherence and compliance, nutrition knowledge, nutritional status and food intake.

Previous reviews about NC in the adult population showed the benefits of this approach. Positive changes in nutrition knowledge and dietary consumption were brought about by NC treatments, which in turn supported individual performance in adult athletes (10). In patients with diseases, such as cancer, NC has been demonstrated to increase protein intake and energy levels (11).

Adolescents are a particular population due to their changing surroundings. A recent scoping review that mapped the heterogeneous literature on NC approach for adolescents found that the effective NC is constructed by multiple NC methods: connecting to the client motivation, providing recurrent feedback, using integrated support tools, showing empathy, including clients preferences, and developing the dietitian’s own professionalism (9).

Our systematic review showed that the overall quality of publications is good, however, improvements still could be made in controlling the confounding factors (non-randomized articles) or during the randomization process (randomized clinical trials), since those are the most common risk of bias found in the selected articles.

The concept of adherence is a topic of continuous discussion in the scientific literature. Terms like compliance and concordance are used interchangeably, despite some evidence supporting their differentiation (48).

The patient-centered techniques associated with NC strategies may theoretically lead to improved adherence; however, this finding was not fully documented in the studies that were included in the analysis. Few studies reported adherence or compliance with heterogeneous methodologies (27, 33, 37, 38, 41, 44, 47). In order to increase the results of an intervention, adherence is a crucial component, and future research should focus more on this area.

In this present review, there are three articles about cystic fibrosis patients. For these patients, some guidelines indicate behavioral intervention strategies associated with nutrition education being more effective when compared to nutritional advice alone. The efficacy of NC was measured by increasing BMI or weight of patients. Currently, NC has been already linked to an improvement in quality of life and wellbeing in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis (49–52).

Other articles presented the anthropometric parameters improvement in overweight or obese patients by decreasing weight or changing body composition (i.e., reduced body fat% and increased lean body mass). The US Preventive Services Task Force (53) published recommendations for overweight and obese children and adolescents. An extensive and intensive behavioral intervention to promote improvements in weight status was classified as a grade B recommendation. The intensity of the interventions is measured by contact hours. When 26 or more contact hours were used in interventions the results showed an adequate weight status for up to 12 months. The intervention involves multiple components, focused on both the parent and child (separately, together, or both): individual sessions (offered for both family and group); information about healthy eating, safe exercising, and reading food labels. Other strategies like encouraging the use of stimulus control (e.g., limiting access to tempting foods and screen time), goal setting, self-monitoring, contingent rewards, and problem solving; and supervised physical activity sessions were also used (53).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (54) also recently published the clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. These guidelines support the positive effect of health behavior and lifestyle treatment, based on a child-focused, family-centered approach. The organization recognizes the importance of an intensive intervention focused on health behavior and lifestyle and highlights some of the aspects associated with successful outcomes, some of them also cited as one strategy of NC, such as motivational interviewing (54).

Although one article presented physical activity change in an undesired direction, two studies underlined the importance of NC for developing an active lifestyle. Another systematic review (55), centered on general behavioral strategies, not only necessarily NC, indicated that adding behavioral modifications to the nutritional and physical activity interventions might have an impact on anthropometric outcomes, such as BMI, skinfold thickness, and BMI z scores. This article also stated that family-based therapy, with active parents and children engagement in making healthier choices, is one of the strongest interventions for childhood obesity. If this approach is complemented with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy could be even more beneficial, because the individuals are encouraged to change attitudes and behaviors that support an actual behavior (55).

Nutritional counseling (NC) treatment improved dietary quality in the studied articles, such as increasing fruits and vegetables consumption (35, 38, 40), water intake (41) or reducing total fat (35) or high-calorie, low-nutrient food intake (38, 46).

Nutrition knowledge can directly affect food choices, and consequently health. Childhood is a crucial period to invest in early-behavioral treatments in order to prevent later adult diseases because this first life stage is a particularly susceptible phase for development (56). Even the parent’s nutrition knowledge can influence dietary habits of children (57). In the present review NC has proven to be a good option to supply nutrition knowledge to children, adolescents and their parents (36, 39, 43).

Nutritional counseling (NC) has been used for children and adolescence since 1990 (27), nonetheless it is not yet a standardized terminology. In fact, one limitation of this study is that the search engine did not recognize the term “NC” as a patient-centered behavioral approach, but sometimes the term is misunderstood as simply giving nutritional advice for patients or clients. This limitation can underestimate the number of publications and the results of strings in databases. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of the publications, some interventions for specific diseases, others made in schools, and completely different sample sizes among the included papers. These limitations did not allow to perform a meta-analysis. This paper focuses only on studies with NC direct to the pediatric population. It was not our goal to have NC with parents or schools, nevertheless some studies involved students (31, 33, 38, 42, 43, 45) or done in childcare centers (40), the focus of intervention was the child or adolescent. For that reason, some studies were excluded in the final phase of analysis (16, 17, 20, 58).

There is a burden for pediatric interventions including multi-disciplinary behavioral strategies from NC, since it is important to consider a patient-centered model to change outcomes for the future of generations, independently of the presence of associated diseases. Families, schools, governmental or non-governmental institutions and communities have the duty of providing to all children the access to high-quality, low-cost foods and beverages that are in consonance with life-long healthful eating (8).

In practice, performing NC in pediatrics is challenging. The counseling strategies must focus on adequate content according to the cognitive ability of each age. It is important to emphasize the multidisciplinary of this intervention which must involve pediatricians and also other pediatric healthcare providers [such as registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs), psychologists, nurses, exercise specialists, and social workers], families, schools, communities, health policy (54). Furthermore, the studies encompassed various diseases, including cystic fibrosis, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, which necessitate a comprehensive approach to knowledge dissemination and health enhancement. NC is a non-invasive therapeutic approach that ought to be implemented early for nutrition intervention in some disease scenarios (11).

Future studies ought to concentrate on the NC tactics that can be most effective for each age range. In general, effective counseling procedures are described in scientific papers, as opposed to less successful and ineffectual strategies (9). Understanding both successful and unsuccessful tactics may help to enhance interventions and, as a result, produce better health results.

Nutritional counseling strategies can be effectively used in children and adolescents. Nevertheless, more structured research must be done focused on this population. To invest in good strategies favoring healthy eating behaviors in pediatrics can lead to better health outcomes in the future population with substantial benefits to society.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/(Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

LN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MG: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FQ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AT: Writing – review & editing. CF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1270048/full#supplementary-material

1. UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

2. Dike IC, Ebizie EN, Chukwuone CA, Ejiofor NJ, Anowai CC, Ogbonnaya EK, et al. Effect of community-based nutritional counseling intervention on children’s eating habits. Medicine (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e26563. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026563

3. Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V, Parazzini F, Brambilla P, Agostoni C. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients. (2018) 10:706. doi: 10.3390/nu10060706

4. Spahn JM, Reeves RS, Keim KS, Laquatra I, Kellogg M, Jortberg B, et al. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. (2010) 110:879–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.021

5. Murimi MW, Kanyi M, Mupfudze T, Amin M, Mbogori T, Aldubayan K. Factors influencing efficacy of nutrition education interventions: a systematic review. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2017) 49:142–65.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.09.003

6. Nikièma L, Huybregts L, Martin-Prevel Y, Donnen P, Lanou H, Grosemans J, et al. Effectiveness of facility-based personalized maternal nutrition counseling in improving child growth and morbidity up to 18 months: a cluster-randomized controlled trial in rural Burkina Faso. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0177839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177839

7. Stok FM, Renner B, Clarys P, Lien N, Lakerveld J, Deliens T. Understanding eating behavior during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: a literature review and perspective on future research directions. Nutrients. (2018) 10:667. doi: 10.3390/nu10060667

8. Ogata BN, Hayes D. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: nutrition guidance for healthy children ages 2 to 11 years. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2014) 114:1257–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.06.001

9. Barkmeijer A, Molder HT, Janssen M, Jager-Wittenaar H. Towards effective dietary counseling: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. (2022) 105:1801–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.12.011

10. Fiorini S, Neri LdCL, Guglielmetti M, Pedrolini E, Tagliabue A, Quatromoni PA, et al. Nutritional counseling in athletes: a systematic review. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1250567. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1250567

11. Ueshima J, Nagano A, Maeda K, Enomoto Y, Kumagai K, Tsutsumi R, et al. Nutritional counseling for patients with incurable cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. (2023) 42:227–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.12.013

12. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

13. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

14. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. (2016) 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

15. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inform. (2018) 34:285–91. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

16. Holmberg Fagerlund B, Helseth S, Glavin K. Parental experience of counselling about food and feeding practices at the child health centre: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. (2019) 28:1653–63. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14771

17. Cunningham K, Suresh S, Kjeldsberg C, Sapkota F, Shakya N, Manandhar S. From didactic to personalized health and nutrition counselling: a mixed-methods review of the GALIDRAA approach in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. (2019) 15:e12681. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12681

18. Becquet R, Bequet L, Ekouevi DK, Viho I, Sakarovitch C, Fassinou P, et al. Two-year morbidity-mortality and alternatives to prolonged breast-feeding among children born to HIV-infected mothers in Côte d’Ivoire. PLoS Med. (2007) 4:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040017

19. Resnicow K, McMaster F, Bocian A, Harris D, Zhou Y, Snetselaar L, et al. Motivational interviewing and dietary counseling for obesity in primary care: an RCT. Pediatrics. (2015) 135:649–57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1880

20. Kubik MY, Story M, Davey C, Dudovitz B, Zuehlke EU. Providing obesity prevention counseling to children during a primary care clinic visit: results from a pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc. (2008) 108:1902–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.017

21. Adde FV, Rodrigues JC, Cardoso AL. Nutritional follow-up of cystic fibrosis patients: the role of nutrition education. J Pediatr (Rio J). (2004) 80:475–82.

22. Dave JM, Liu Y, Chen T, Thompson DI, Cullen KW. Does the kids café program’s nutrition education improve children’s dietary intake? A pilot evaluation study. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2018) 50:275–82.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.11.003

23. El-Koofy N, El-Mahdy M, Fathy M, El Falaki M, El Dine Hamed D. Nutritional rehabilitation for children with cystic fibrosis: single center study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2020) 35:201–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.09.001

24. Grady A, Barnes C, Lum M, Jones J, Yoong SL. Impact of nudge strategies on nutrition education participation in child care: randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2021) 53:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2020.11.017

25. Kuehl KS, Cockerham JT, Hitchings M, Slater D, Nixon G, Rifai N. Effective control of hypercholesterolemia in children with dietary interventions based in pediatric practice. Prev Med. (1993) 22:154–66. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1013

26. Ojeda-Rodríguez A, Zazpe I, Morell-Azanza L, Chueca MJ, Azcona-Sanjulian MC, Marti A. Improved diet quality and nutrient adequacy in children and adolescents with abdominal obesity after a lifestyle intervention. Nutrients. (2018) 10: 1500. doi: 10.3390/nu10101500

27. Hanna KJ, Ewart CK, Kwiterovich PO. Child problem solving competence, behavioral adjustment and adherence to lipid-lowering diet. Patient Educ Couns. (1990) 16:119–31. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(90)90086-z

28. Knöpfli BH, Radtke T, Lehmann M, Schätzle B, Eisenblätter J, Gachnang A, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary inpatient intervention on body composition, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in severely obese girls and boys. J Adolesc Health. (2008) 42:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.015

29. Savoye M, Berry D, Dziura J, Shaw M, Serrecchia JB, Barbetta G, et al. Anthropometric and psychosocial changes in obese adolescents enrolled in a Weight Management Program. J Am Diet Assoc. (2005) 105:364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.12.009

30. Smith A, Annesi JJ, Walsh AM, Lennon V, Bell RA. Association of changes in self-efficacy, voluntary physical activity, and risk factors for type 2 diabetes in a behavioral treatment for obese preadolescents: a pilot study. J Pediatr Nurs. (2010) 25:393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2009.09.003

31. Pierce B, Bowden B, McCullagh M, Diehl A, Chissell Z, Rodriguez R, et al. A summer health program for African-American high school students in Baltimore, Maryland: community partnership for integrative health. Explore (NY). (2017) 13:186–97. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2017.02.002

32. Seo Y, Lim H, Kim Y, Ju Y, Lee H, Jang HB, et al. The effect of a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention on obesity status, body composition, physical fitness, and cardiometabolic risk markers in children and adolescents with obesity. Nutrients. (2019) 11: 137. doi: 10.3390/nu11010137

33. Amaya-Castellanos C, Shamah-Levy T, Escalante-Izeta E, Morales-Ruán MD, Jiménez-Aguilar A, Salazar-Coronel A, et al. Development of an educational intervention to promote healthy eating and physical activity in Mexican school-age children. Eval Program Plann. (2015) 52:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.05.002

34. Stark LJ, Mulvihill MM, Powers SW, Jelalian E, Keating K, Creveling S, et al. Behavioral intervention to improve calorie intake of children with cystic fibrosis: treatment versus wait list control. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (1996) 22:240–53. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199604000-00005

35. Couch SC, Saelens BE, Levin L, Dart K, Falciglia G, Daniels SR. The efficacy of a clinic-based behavioral nutrition intervention emphasizing a DASH-type diet for adolescents with elevated blood pressure. J Pediatr. (2008) 152:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.022

36. Leach RA, Yates JM. Nutrition and youth soccer for childhood overweight: a pilot novel chiropractic health education intervention. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. (2008) 31:434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.06.003

37. Hofsteenge GH, Chinapaw MJ, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Weijs PJ. Long-term effect of the Go4it group treatment for obese adolescents: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr. (2014) 33:385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.06.002

38. Cunha DB, de Souza Bda SN, Pereira RA, Sichieri R. Effectiveness of a randomized school-based intervention involving families and teachers to prevent excessive weight gain among adolescents in Brazil. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e57498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057498

39. Windham ME, Hastings ES, Anding R, Hergenroeder AC, Escobar-Chaves SL, Wiemann CM. “Teens talk healthy weight”: the impact of a motivational digital video disc on parental knowledge of obesity-related diseases in an adolescent clinic. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2014) 114:1611–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.04.014

40. Iaia M, Pasini M, Burnazzi A, Vitali P, Allara E, Farneti M. An educational intervention to promote healthy lifestyles in preschool children: a cluster-RCT. Int J Obes (Lond). (2017) 41:582–90. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.239

41. Wong JM, Ebbeling CB, Robinson L, Feldman HA, Ludwig DS. Effects of advice to drink 8 cups of water per day in adolescents with overweight or obesity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. (2017) 171:e170012. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0012

42. Koch PA, Contento IR, Gray HL, Burgermaster M, Bandelli L, Abrams E, et al. Food, health, & choices: curriculum and wellness interventions to decrease childhood obesity in fifth-graders. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2019) 51:440–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2018.12.001

43. Zhao C, Ma L, Gao L, Wu Y, Yan Y, Peng W, et al. Effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention for the improvement of nutritional status and nutrition knowledge of children in poverty-stricken areas in Shaanxi Province, China. Global Health J. (2022) 6:156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2022.07.009

44. Watson PM, McKinnon A, Santino N, Bassett-Gunter RL, Calleja M, Josse AR. Integrating needs-supportive delivery into a laboratory-based randomised controlled trial for adolescent girls with overweight and obesity: theoretical underpinning and 12-week psychological outcomes. J Sports Sci. (2021) 39:2434–43. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2021.1939948

45. Guo H, Zeng X, Zhuang Q, Zheng Y, Chen S. Intervention of childhood and adolescents obesity in Shantou city. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2015) 9:357–64. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.11.006

46. Lee SY, Kim J, Oh S, Kim Y, Woo S, Jang HB, et al. A 24-week intervention based on nutrition care process improves diet quality, body mass index, and motivation in children and adolescents with obesity. Nutr Res. (2020) 84:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.09.005

47. Stark LJ, Opipari LC, Spieth LE, Jelalian E, Quittner AL, Higgins L, et al. Contribution of behavior therapy to dietary treatment in cystic fibrosis: a randomized controlled study with 2-year follow-up. Behav Ther. (2003) 34:237–58. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80015-1

48. Lopes Neri LC, Guglielmetti M, De Giorgis V, Pasca L, Zanaboni MP, Trentani C, et al. Validation of an Italian questionnaire of adherence to the ketogenic dietary therapies: iKetoCheck. Foods. (2023) 12: 3214. doi: 10.3390/foods12173214

49. Neri LC, Simon MI, Ambrósio VL, Barbosa E, Garcia MF, Mauri JF, et al. Brazilian guidelines for nutrition in cystic fibrosis. Einstein (Sao Paulo). (2022) 20:eRW5686. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2022RW5686

50. Leonard A, Bailey J, Bruce A, Jia S, Stein A, Fulton J, et al. Nutritional considerations for a new era: a CF foundation position paper. J Cyst Fibros. (2023) 22:788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.05.010

51. Gonzalez NA, Dayo SM, Fatima U, Sheikh A, Puvvada CS, Soomro FH, et al. Systematic review of cystic fibrosis in children: can non-medical therapy options lead to a better mental health outcome? Cureus. (2023) 15:e37218. doi: 10.7759/cureus.37218

52. Saxby N, Painter C, Kench A, O’Neill P, van der Haak N, King S, et al. The Australian and New Zealand Cystic Fibrosis Nutrition Guideline Authorship Group. In Full Guideline: Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis in Australia and New Zealand. (2018). Bell, S. C., editor. Sydney: Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand.

53. Us Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. (2017) 317:2417–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6803

54. Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics. (2023) 151:e2022060640. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-060640

55. Salam RA, Padhani ZA, Das JK, Shaikh AY, Hoodbhoy Z, Jeelani SM, et al. Effects of lifestyle modification interventions to prevent and manage child and adolescent obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2208. doi: 10.3390/nu12082208

56. Nader JL, López-Vicente M, Julvez J, Guxens M, Cadman T, Elhakeem A, et al. Measures of early-life behavior and later psychopathology in the LifeCycle project - EU child cohort network: a cohort description. J Epidemiol. (2023) 33:321–31. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20210241

57. Wang L, Zhuang J, Zhang H, Lu W. Association between dietary knowledge and overweight/obesity in Chinese children and adolescents aged 8-18 years: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. (2022) 22:558. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03618-2

58. Bertuzzi F, Stefani I, Rivolta B, Pintaudi B, Meneghini E, Luzi L, et al. Teleconsultation in type 1 diabetes mellitus (TELEDIABE). Acta Diabetol. (2018) 55:185–92. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-1084-9

Keywords: nutritional counseling, children, adolescents, nutritional strategies, systematic review

Citation: Neri LdCL, Guglielmetti M, Fiorini S, Quintiero F, Tagliabue A and Ferraris C (2024) Nutritional counseling in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Front. Nutr. 11:1270048. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1270048

Received: 31 July 2023; Accepted: 15 January 2024;

Published: 01 February 2024.

Edited by:

Mauro Fisberg, Federal University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Artur Mazur, University of Rzeszow, PolandCopyright © 2024 Neri, Guglielmetti, Fiorini, Quintiero, Tagliabue and Ferraris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simona Fiorini, c2ltb25hLmZpb3JpbmlAdW5pcHYuaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.