- Nutrition and Clinical Services Division, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Introduction: Undernourishment is disproportionately spread within Bangladesh, making some regions like Sylhet more vulnerable than the rest of the country. We aimed to assess the trend of diverse associated factors related to childhood stunting, wasting, and being underweight. Furthermore, we have compared the estimated factors between Sylhet, the most vulnerable region, and other parts of Bangladesh.

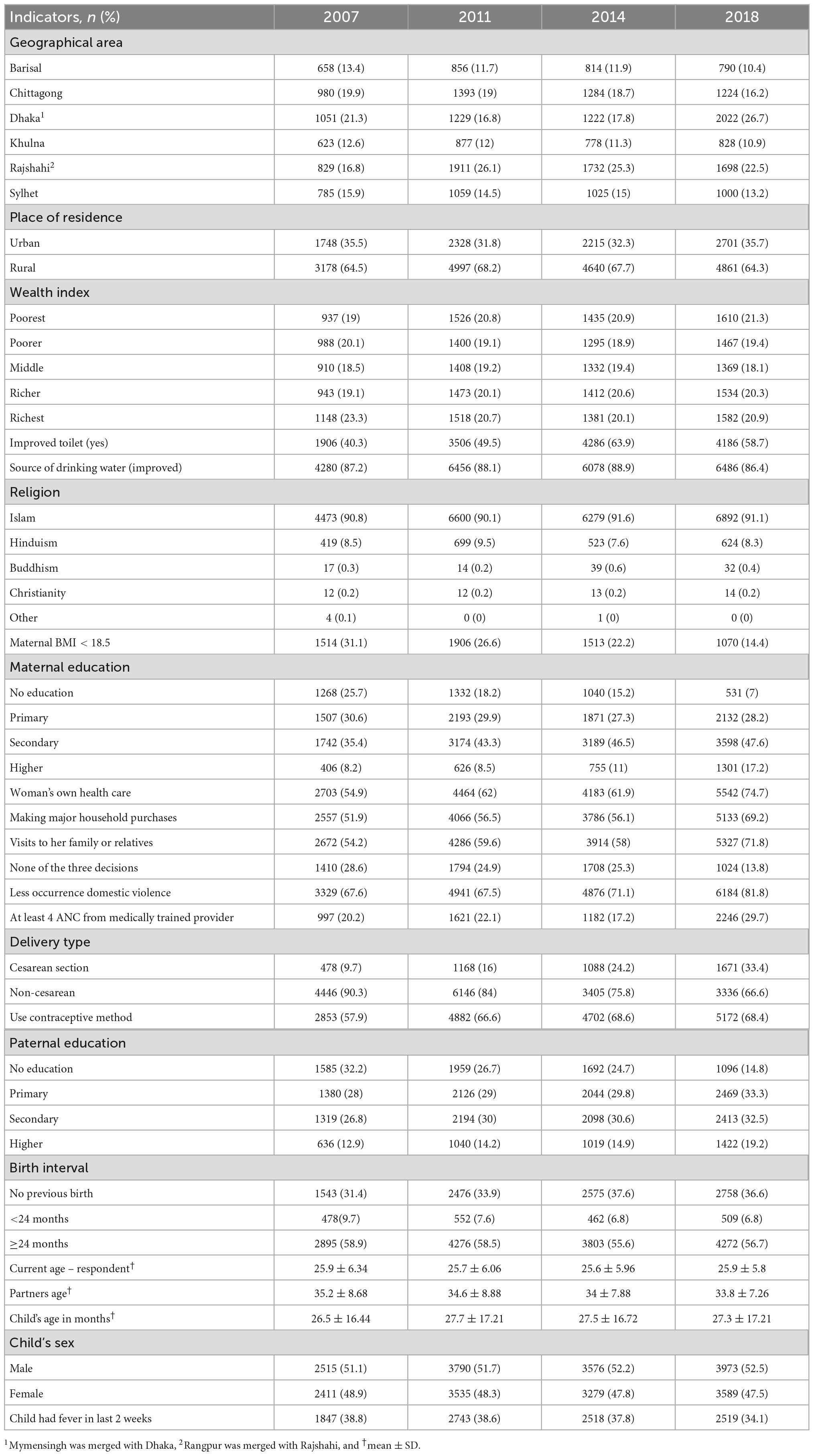

Methods: We performed a secondary data analysis where data were derived from the nationally representative cross-sectional surveys: Bangladesh demographic and health survey (BDHS) 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2017–18 rounds. The outcome variables were childhood undernutrition, including stunting, wasting, and being underweight. Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and proportion were used to summarize the data. All variables were summarized by BDHS survey time points. We used multiple logistic regression models to measure the associated factors with childhood stunting, wasting, and being underweight.

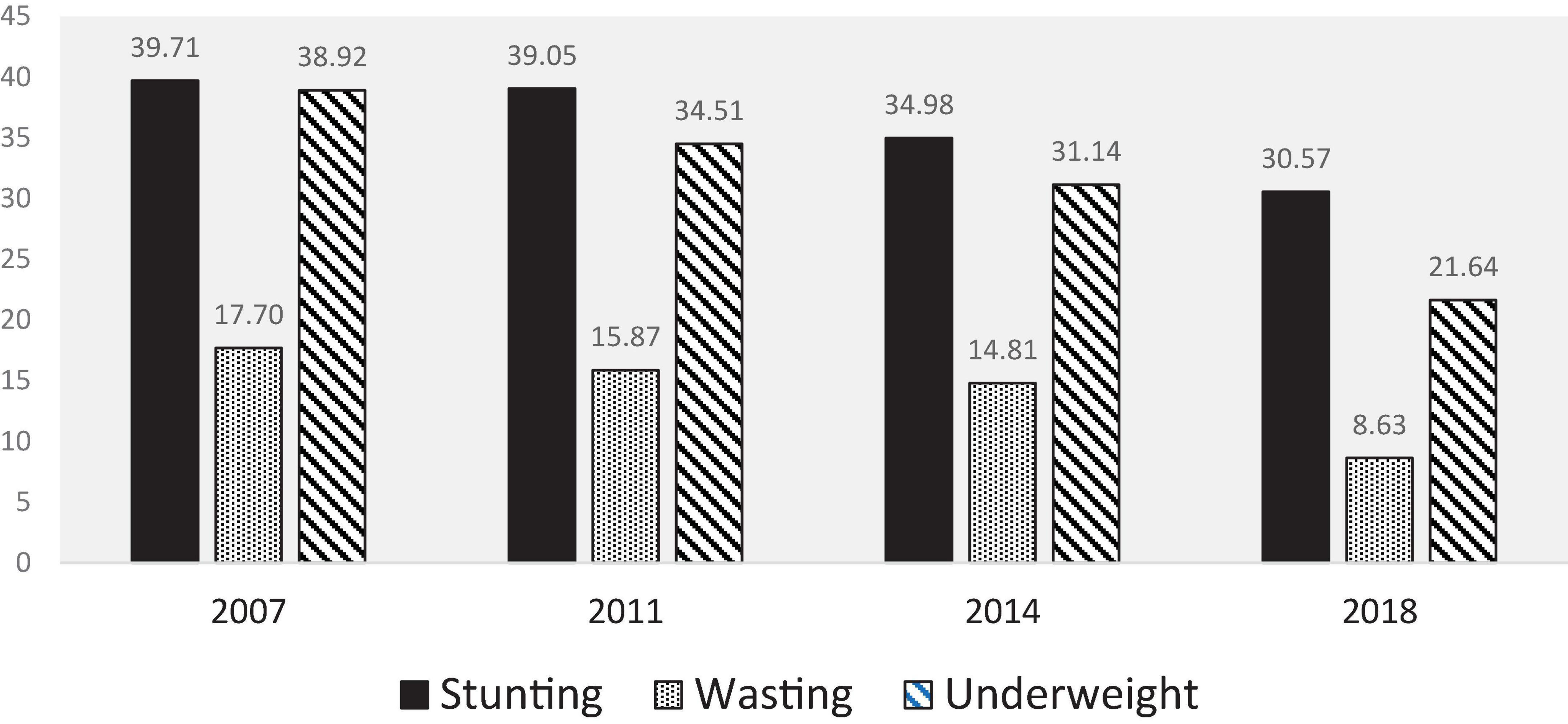

Results: The percentage of children under the age of 5 years who were stunted declined from 40% in 2007 to 31% in 2018. Similar trends are observed in the decrease in the percentage of underweight children, dropping from 39% in 2007 to 22% in 2018. Wasting dropped to 8% in 2018 after years of critically high levels (17%). According to the results of the regression analyses, urban residence, child’s age and gender, morbidity, maternal BMI, maternal and paternal education, decision-making ability, use of contraceptives, the occurrence of domestic violence, antenatal care, c-section, and birth interval, as well as geographic region, were all linked to childhood malnutrition.

Conclusion: The Sylhet division falls short in several critical associated indicators, including parental education, maternal BMI, obtaining at least four ANC, women empowerment, and usage of contraceptives. Policymakers must concentrate on region-specific planning and proper intervention to achieve a more uniform improvement across the country.

Background

Undernutrition includes wasting (low weight-for-height), stunting (low height-for-age), and underweight (low weight-for-age). Low weight-for-height is known as wasting, indicating acute and severe weight loss. Low height-for-age or stunting is a consequence of chronic undernutrition. Underweight or low-weight-for-age children are a combination of the above two outcomes and can be stunted, wasted, or both (1, 2). Undernourished children face greater vulnerability to disease and subsequent death as nearly 45% of deaths among children under 5 years of age could be directly related to this (3). A significant portion of these children come from low- and middle-income countries. However, the prevalence of undernourished children greatly varies within the same country. This is well evident that undernutrition is an adverse outcome modulated by multidimensional components (4). These encompass direct factors such as poor dietary habits and illness (5); lack of food security and inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene commodities (6); insufficient access to health services (7) and overarching social factors like poverty with economic and demographic disadvantages (8). All these elements vary between and within countries, which requires context-specific research to develop interventions supported by evidence (9).

Bangladesh has achieved impressive social and economic development growth over the past three decades. Yet, a hefty proportion of its population (43%) lives under the poverty line of 1.25 dollars per day (10). Such a vast population unable to afford nutritious food or access improved healthcare facilities, makes the goal of reducing the country’s prevalence of undernourished children extremely challenging. Furthermore, undernourishment is disproportionately spread within the country, making some regions even more vulnerable than others (11, 12). Although the poverty rate is lower in the eastern part of Bangladesh, surprisingly, the undernutrition rate is much more prevalent in this region compared to the north-western part (12, 13). The Sylhet region is considered ecologically susceptible due to being a remote area, wetland ecosystems, and social dogmatism (7, 13). Such unique regional factors may create non-income obstacles, hindering the nutritional status of children (12). However, the change in these factors in Bangladesh over time has yet to be explored. Through our analysis, we aimed to assess the trend of childhood stunting, wasting, and underweight and explore the factors influencing these metrics. The second objective was to compare the estimated factors between Sylhet, the most vulnerable region, and other regions of Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

Data sources

For this paper, we used secondary data derived from the nationally representative cross-sectional surveys of the BDHS 2007 (14), 2011 (15), 2014 (16), and 2018 (17), undertaken by the authority of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s National Institute for Population Research and Training (NIPORT). The BDHS follows a similar study design that has been described in the published reports. Briefly, the BDHS sample was stratified and selected in two stages. Administratively, Bangladesh was divided into several divisions, and each division was further stratified into urban and rural areas. The whole list of enumeration areas (EAs) spanning the entire nation, created by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh population census, served as the sample frame for the BDHS.

To draw the sample, required EAs as a cluster were selected with a probability proportional to the EA in the first stage. Household listing was done based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and prepared the sampling frame. In the second stage of selection, a fixed number of required households per cluster were selected using a systematic sampling procedure from the newly created sampling frame. We used Children’s Record (KR) data for this analysis. Data for a total of 12,860 youngest children were used from four consecutive BDHS (2007–2011); of those 4,926 were from 2007, 7,325 samples from 2011, 6,855 samples from 2014, and the rest of the 7,562 were extracted from the 2017-18 BDHS.

Variable under study

The outcome variables of this paper focus on childhood undernutrition including stunting, wasting, and being underweight. These variables were derived from child’s age and sex-specific composite indicators such as length/height-for-age z score (LAZ/HAZ), weight-for-length/height z score (WLZ/WHZ) and weight-for-age z score where the z score was defined as “(observe anthropometry value – average value of reference population)/standard deviation of reference population.” Children were defined as stunted if LAZ/HAZ < −2, wasted if WLZ/WHZ < −2 and underweight if WAZ < −2 [2]. In the database, cases were treated as missing if LAZ/HAZ > 6 or LAZ/HAZ < −6, WLZ/WHZ > 5 or WLZ/WHZ < −5, and WAZ > 5 or WAZ < −6.

Based on the literature review as well as the bi-variate relationship with childhood nutritional status, several independent variables were selected such as geographical area, place of residence, wealth index, improved toilet, source of drinking water, religion, maternal BMI < 18.5, maternal education, empowerment, attitude toward domestic violence, receiving at least four ANC from a medically trained provider, delivery type, use of a contraceptive method, paternal education, birth interval, current age – respondent, partners age, child’s age in months, child’s sex, and having fever in last 2 weeks. The mother’s empowerment was defined as the ability to make decisions about her own health care, major household purchases, and visits to family or relatives.

Statistical analyses

We performed analyses using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Firstly, to visualize the outcome indicators, statistical plot like bar diagram was used. Several descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and proportion were used to summarize the data. All variables were summarized by BDHS survey time points. Due to binary outcomes, simple logistic regression was used to assess the bi-variate association between outcome variables and all independent variables. We used multiple logistic regression models to assess the associated factors with childhood stunting, wasting, and being underweight. The independent variables were included in the model based on the literature review as well as the bi-variate association. “svyset” option was used to allow for adjustments for the cluster sampling design, weights and the calculation of standard errors. Again, logistic regression was used to assess the status of wealth index, birth interval, cesarean delivery, ANC visit, attitude toward domestic violence, contraceptive methods, empowerment, paternal and maternal education, maternal underweight, and child’s morbidity in the Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, and Rajshahi regions compared with the Sylhet region. We selected the Sylhet region as the reference as several health indicators are performing poorly here. The odds ratios with 95% CIs were calculated as inferential statistics and P < 0.05 were considered as a significance level.

Results

Over 60% of the data was collected from rural areas, and the rest of the data was collected from urban areas over time. The background characteristics of the surveyed children from 0 to 59 months old in 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2018 BDHS are shown in Table 1. Our findings show the nutritional status of children has improved steadily over the past decade (Figure 1). The percentage of children under age of 5 years who were stunted declined from 40% in 2007 to 31% in 2018. The decline in the percentage of children who are underweight followed a similar pattern, falling from 39% in 2007 to 22% in 2018. After years at critically high levels (17%), wasting decreased to 8% in 2018.

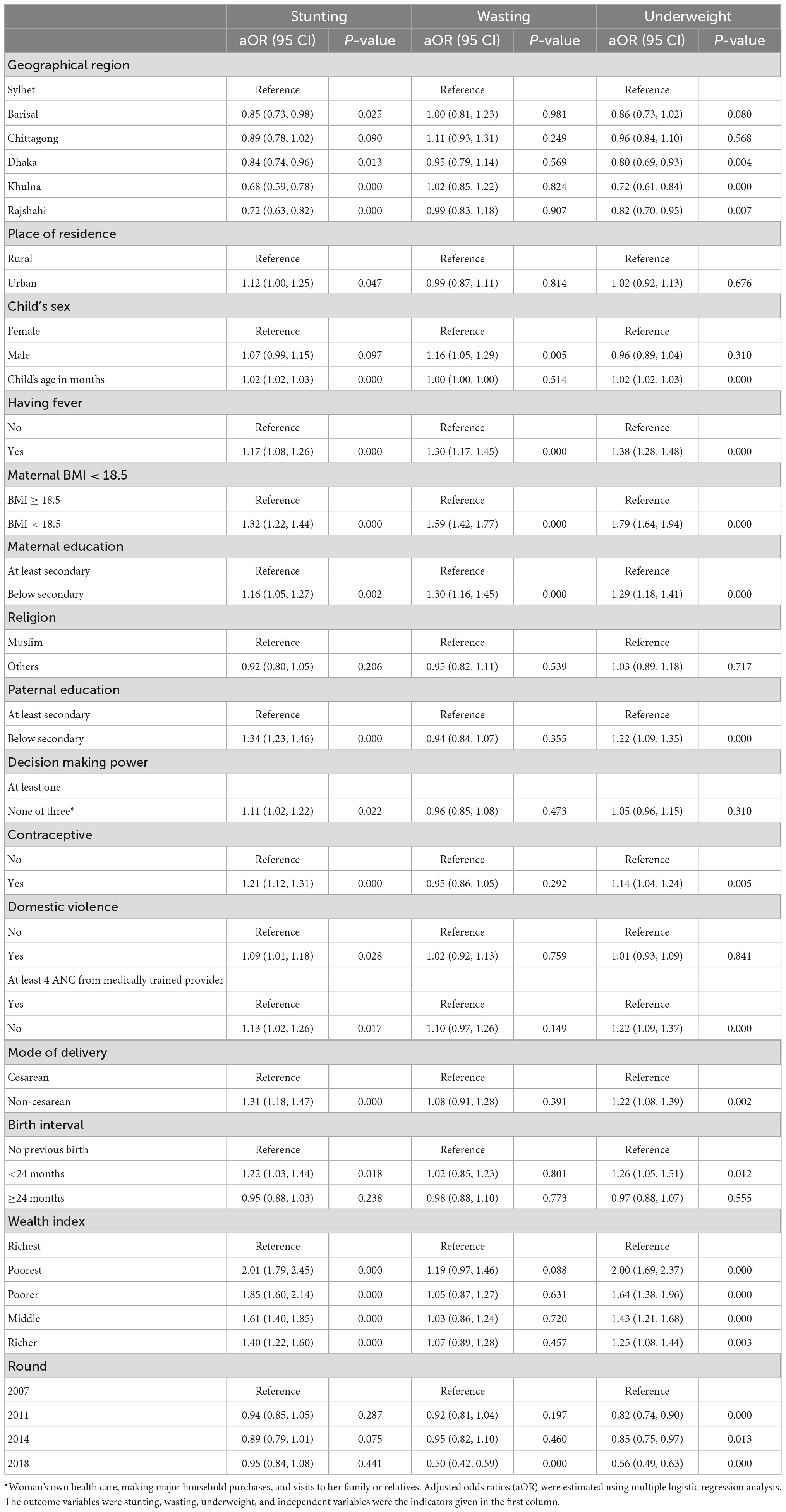

Table 2 presents the factors associated with childhood stunting, wasting and being underweight. Childhood stunting was associated with urban residence [aOR: 1.12 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.25); p-value = 0.047], having a fever in the last 2 weeks [aOR: 1.17 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.26); p-value < 0.001], maternal BMI < 18.5 [aOR: 1.32 (95% CI: 1.22, 1.44); p-value < 0.001], maternal education below secondary [aOR: 1.16 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.27); p-value = 0.002], paternal education below secondary [aOR: 1.34 (95% CI: 1.23, 1.46); p-value < 0.001], not having decision-making power [aOR: 1.11 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.22); p-value = 0.022], using contraceptive [aOR: 1.21 (95% CI: 1.12, 1.31); p-value < 0.001], the occurrence of domestic violence [aOR: 1.09 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.18); p-value = 0.028], not receiving at least four ANC [aOR: 1.13 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.26); p-value = 0.017], non-cesarean delivery [aOR: 1.31 (95% CI: 1.18, 1.47); p-value < 0.001], and birth interval < 24 months [aOR: 1.22 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.44); p-value = 0.018].

Childhood wasting was associated with the male sex [aOR: 1.16 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.29); p-value = 0.005], having a fever in the last 2 weeks [aOR: 1.30 (95% CI: 1.17, 1.45); p-value < 0.001], maternal BMI < 18.5 [aOR: 1.59 (95% CI: 1.42, 1.77); p-value < 0.001], and maternal education below secondary [aOR: 1.30 (95% CI: 1.16, 1.45); p-value < 0.001].

Childhood underweight was associated with having fever in the last 2 weeks [aOR: 1.38 (95% CI: 1.28, 1.48); p-value < 0.001], maternal BMI < 18.5 [aOR: 1.79 (95% CI: 1.64, 1.94); p-value < 0.001], maternal education below secondary [aOR: 1.29 (95% CI: 1.18, 1.41); p-value < 0.001], paternal education below secondary [aOR: 1.22 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.35); p-value < 0.001], using contraceptive [aOR: 1.14 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.24); p-value = 0.005], not receiving at least four ANC [aOR: 1.22 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.37); p-value < 0.001], non-cesarean delivery [aOR: 1.22 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.39); p-value = 0.002], and birth interval < 24 months [aOR: 1.26 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.51); p-value = 0.012]. Geographical region and child’s age were associated with both stunting and underweight. On the other hand, low socio-economic status had high prevalence of childhood stunting and being underweight.

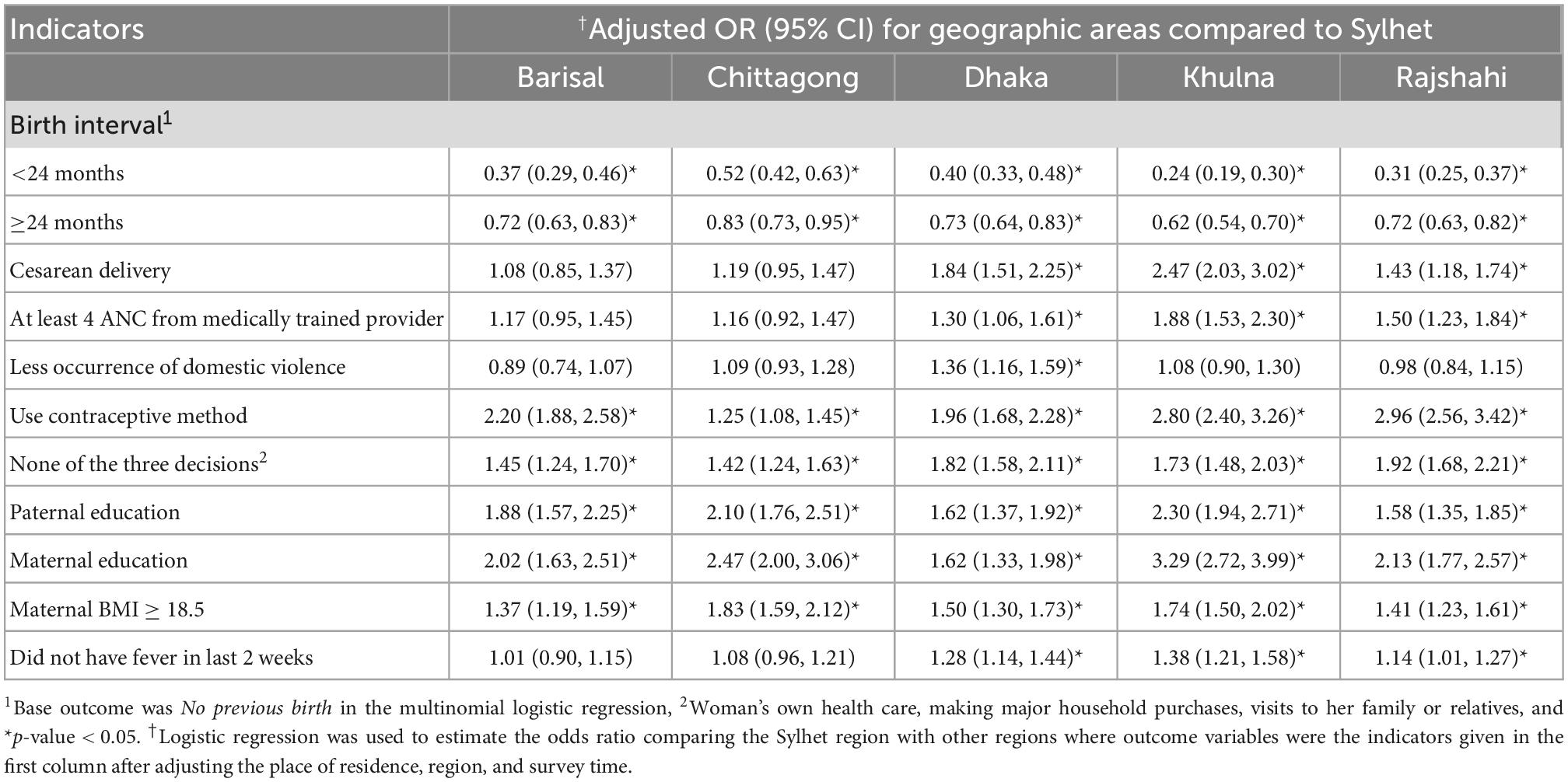

We have compared the common predictors of undernutrition in Table 3 across the geographical regions. We found that status of cesarean delivery, receiving at least 4 ANC from a medically trained provider, use of contraceptive methods, empowerment, paternal education, maternal education, maternal BMI > 18.5, and not reporting fever in the last 2 weeks were better in those regions compared with the Sylhet region.

Discussion

With remarkable accomplishments in several health indicators, Bangladesh is yet to achieve the goal of reducing undernutrition among children under the age of 5 years, particularly in the Sylhet region. Through this analysis, we aimed to explore the factors influencing childhood undernutrition and compare the factors between Sylhet, the most vulnerable region, and other regions of Bangladesh.

We found that overall, child reporting fever in recent days, maternal BMI, type of birth, mother’s education, father’s education, household wealth, and geographical region were the common significant associated factors for childhood undernutrition. Having a fever in the 2 weeks leading up to the survey appears to be a significant determinant in childhood undernutrition. This has been established in previous studies in resource-poor settings (18, 19). Infections cause decreased food intake, nutritional losses due to poor digestion, and metabolic disturbances, all leading to undernutrition (19).

Our results show that children of women with no or only primary education are more likely to be affected by any kind of undernutrition. However, we also found a trend in the reduction of low educational qualifications among the surveyed mothers with increased percentages of mothers having secondary or higher secondary education over the decades. Other Bangladeshi studies have reported comparable results, showing that children of mothers with less educational qualification were significantly at greater risk of being undernourished (20, 21). Education enables a mother to receive and process information more effectively (22), empowering a mother to make informed decisions regarding health and nutrition. Also, it might increase their utilization of child health services (23).

Household wealth (the two measures of SES) appeared to be a strong predictor of child malnutrition outcomes. In Bangladesh and other underdeveloped nations, socio-economic indicators are protective factors for child health (12). Children residing in higher-income households are more likely to belong to comparatively food-secure families, have parents with relatively higher education and live in a better area with better access to health facilities (11, 24, 25). All these factors in combination possibly modulate the risk of undernutrition among the children residing in higher wealth index households.

One of our key objectives was to explore if there is any geographical variation in the established common associated factors of undernutrition. We found that the Sylhet division lags in several key risk indicators, namely parental education, maternal BMI, receiving at least four ANC from the medically trained provider, women empowerment, and use of contraceptive methods compared to other regions. UN reports (26), as well as several local studies (11, 13, 27–30), have confirmed the poor performance of the Sylhet division despite having the lowest poverty rate in the country. This has been well documented that along with the highest rates of chronic childhood undernutrition that is stunting, Sylhet also has the lowest female literacy rates, the worst school attendance rates for adolescent girls, the highest gender inequality scores, the worst performance against women’s empowerment indicators, and overall the lowest proportion of empowered women in the nation (31), concurring with our findings. Such a result is very startling as Sylhet is considered a rich region as a vast number of its population lives abroad and sends remittances. However, this is a unique regional characteristic that potentially poses a barrier in several distinctive ways. Geographically, over a fourth of all arable land in Sylhet Division remains uncultivated, and only a single crop is produced on half of the remaining land, making the greater Sylhet region less productive. Furthermore, Haor (wetland) and tea estates are two significantly diverse geographical locations in the Sylhet region where a large portion of the marginalized population resides. It has been reported that about 54% of farmers in greater Sylhet are either marginal landholders or not at all. Affluent non-residents own a major portion of cultivable lands, keeping Sylhet’s farming potential vastly underutilized (32, 33). Related to this, there is a notable temptation among the locals to migrate to a foreign country for a better livelihood. Hence, many poor families lack the willingness to send their children to schools, increasing the high incidence of child labor, paid or unpaid, until they grab any opportunity to go abroad (34, 35).

Limitations

Our analysis incorporates limitations, similar to other cross-sectional surveys. Due to the study design and cross-sectional data collection in the primary phase, our findings do not allow us to conclude any causal association between the factors and child undernutrition outcomes. Furthermore, the primary data did not include important indicators like child birthweight. We were unable to account for other regional factors such as community-level poverty, physical and financial barriers to health facilities, that may have influenced the associations.

Conclusion

We conclude that several common indicators play a critical role in regulating different aspects of the nutritional status of the under-five children in Bangladesh. Furthermore, some of the indicators are showing a trend of improvement, but significant regional variation still exists. To achieve a more homogenous improvement across the country, the policymakers must focus on region-specific planning and appropriate intervention.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://dhsprogram.com/Data/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey received ethical approval from the Inner City Fund (ICF) Macro Institutional Review Board, Maryland, USA and the National Research Ethics Committee of Bangladesh Medical Research Council (BMRC), Dhaka, Bangladesh. Each participant gave informed consent before participating in the survey. The de-identified data for this study were obtained from the DHS online. Institutional ethical approval was not necessary as the study was conducted on anonymous public-use data, which had no identifiable information on the survey respondents. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KS, MH, and MK: conceptualization. KS and MH: data curation. MH: formal analysis. KS and MK: software and writing – original draft. KS, MK, MH, RR, and TA: writing – review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program to give us permission to access the data used in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. De Onis M, Blössner M. The World Health Organization global database on child growth and malnutrition: methodology and applications. Int J Epidemiol. (2003) 32:518–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg099

2. De Onis M, Borghi E, Arimond M, Webb P, Croft T, Saha K, et al. Prevalence thresholds for wasting, overweight and stunting in children under 5 years. Public Health Nutr. (2019) 22:175–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018002434

3. Clark H, Coll-Seck A, Banerjee A, Peterson S, Dalglish S, Ameratunga S, et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet. (2020) 395:605–58.

4. Keeley B, Little C, Zuehlke E. The State of the World’s Children 2019: Children, Food and Nutrition–Growing Well in a Changing World. New York, NY: UNICEF (2019).

5. Onyango A, Jean-Baptiste J, Samburu B, Mahlangu T. Regional overview on the double burden of malnutrition and examples of program and policy responses: African region. Ann Nutr Metab. (2019) 75:127–30. doi: 10.1159/000503671

6. Mohsena M, Mascie-Taylor C, Goto R. Association between socio-economic status and childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh; a comparison of possession score and poverty index. Public Health Nutr. (2010) 13:1498–504. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001758

7. Pulok M, Uddin J, Enemark U, Hossin M. Socioeconomic inequality in maternal healthcare: an analysis of regional variation in Bangladesh. Health Place. (2018) 52:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.06.004

8. Horton S, Shekar M, McDonald C, Mahal A, Brooks J. Scaling up Nutrition: What will it Cost?. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications (2009). doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-8077-2

9. Ahamada H, Sunguya B. The burden of undernutrition and its associated factors among children below 5 years of age in bambao region, Comoros. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:885002. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.885002

10. Devkota S, Panda B. Socioeconomic gradients in early childhood health: evidence from Bangladesh and Nepal. Int J Equity Health. (2016) 15:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0364-2

11. Chowdhury T, Chakrabarty S, Rakib M, Saltmarsh S, Davis K. Socio-economic risk factors for early childhood underweight in Bangladesh. Glob Health. (2018) 14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0372-7

12. Hasan M, Uddin J, Pulok M, Zaman N, Hajizadeh M. Socioeconomic inequalities in child malnutrition in Bangladesh: do they differ by region? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1079. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17031079

13. Sen B, Ahmed M, Yunus M, Ali Z. Regional Inequality in Bangladesh in the 2000s: Re-visiting the East-West divide debate. Dhaka: Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies Dhaka (2014).

14. National Institute of Population Research and Training – NIPORT/Bangladesh, Mitra and Associates/Bangladesh, Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Dhaka: NIPORT (2009).

15. National Institute of Population Research and Training – NIPORT/Bangladesh, Mitra and Associates/Bangladesh, ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Dhaka: NIPORT (2013).

16. National Institute of Population Research and Training – NIPORT/Bangladesh, Mitra and Associates, ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Dhaka: NIPORT (2016).

17. National Institute of Population Research and Training [NIPORT], Mitra and Associates, ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Dhaka: NIPORT (2017).

18. Akram R, Sultana M, Ali N, Sheikh N, Sarker A. Prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children and its urban–rural disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. (2018) 39:521–35. doi: 10.1177/0379572118794770

19. Ntenda P, Chuang Y. Analysis of individual-level and community-level effects on childhood undernutrition in Malawi. Pediatr Neonatol. (2018) 59:380–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2017.11.019

20. Rahman A, Chowdhury S. Determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children in Bangladesh. J Biosoc Sci. (2007) 39:161–73. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001295

21. Chisti M, Hossain M, Malek M, Faruque A, Ahmed T, Salam M. Characteristics of severely malnourished under-five children hospitalized with diarrhoea, and their policy implications. Acta Paediatr. (2007) 96:693–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00192.x

22. Glewwe P. Why does mother’s schooling raise child health in developing countries? Evidence from Morocco. J Hum Resour. (1999) 34:124–59. doi: 10.2307/146305

23. Le K, Nguyen M. Shedding light on maternal education and child health in developing countries. World Dev. (2020) 133:105005. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105005

24. Sultan S, Faysal M, Alam M. Social Gradients of Childhood Morbidity and Malnutrition in Bangladesh: Evidence from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019. J Popul Dev. (2020) 2:51–67.

25. Islam M, Rahman M, Rahman M, Nomura S, De Silva A, Lanerolle P, et al. Reducing childhood malnutrition in Bangladesh: the importance of addressing socio-economic inequalities. Public Health Nutr. (2020) 23:72–82. doi: 10.1017/S136898001900140X

26. UNICEF. Analysis of the Situation of Children and Women in Bangladesh 2015. Dhaka: UNICEF (2015).

27. Rabbani A, Khan A, Yusuf S, Adams A. Trends and determinants of inequities in childhood stunting in Bangladesh from 1996/7 to 2014. Int J Equity Health. (2016) 15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0477-7

28. Mohsena M, Goto R, Mascie-Taylor C. Regional variation in maternal and childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh: evidence from demographic and health surveys. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. (2015) 4:139–49. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.206683

29. Saha U, Chattapadhayay A, Richardus J. Trends, prevalence and determinants of childhood chronic undernutrition in regional divisions of Bangladesh: Evidence from demographic health surveys, 2011 and 2014. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0220062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229677

30. Das S, Baffour B, Richardson A. Prevalence of child undernutrition measures and their spatio-demographic inequalities in Bangladesh: an application of multilevel Bayesian modelling. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1008. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13170-4

31. Save the Children UK. A Cost of the Diet Analysis in Sylhet & Moulvibazar District in North-East Bangladesh, December 2018. London: Save the Children UK (2019).

32. Nasrin M, Uddin M. Land tenure system and agricultural productivity in a selected area of Bangladesh. Progress Agric. (2011) 22:181–92. doi: 10.3329/pa.v22i1-2.16479

34. Nath S, Kabir M, Ahmed K, Roy G, Hossain A, Alam S, et al. Exploring Low Performance in Education: The Case of Sylhet Division. Dhaka: Campaign for Popular Education (2011).

Keywords: undernutrition, stunting, wasting, underweight, Sylhet region, Bangladesh, trend

Citation: Sanin KI, Khanam M, Rita RS, Haque MA and Ahmed T (2023) Common factors influencing childhood undernutrition and their comparison between Sylhet, the most vulnerable region, and other parts of Bangladesh: Evidence from BDHS 2007–18 rounds. Front. Nutr. 9:999520. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.999520

Received: 21 July 2022; Accepted: 21 December 2022;

Published: 09 January 2023.

Edited by:

Alfredo Martínez, Centro de Investigación Biomédica de La Rioja, SpainReviewed by:

Kulnipa Kittisakmontri, Chiang Mai University, ThailandPrema Ramachandran, Nutrition Foundation of India, India

Copyright © 2023 Sanin, Khanam, Rita, Haque and Ahmed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kazi Istiaque Sanin,  c2FuaW5AaWNkZHJiLm9yZw==

c2FuaW5AaWNkZHJiLm9yZw==

Kazi Istiaque Sanin

Kazi Istiaque Sanin Mansura Khanam

Mansura Khanam Razia Sultana Rita

Razia Sultana Rita Md. Ahshanul Haque

Md. Ahshanul Haque Tahmeed Ahmed

Tahmeed Ahmed