- 1Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, World Health Organization, Cairo, Egypt

- 2Department of Nutrition, School of Health Sciences, Modern University for Business and Sciences, Beirut, Lebanon

Marketing of food items high in added saturated and/or trans-fat, sugar, or sodium (HFSS) negatively affect consumption patterns of young children. The World Health Organization (WHO) advised countries to regulate the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to young populations. The aim of this manuscript is to provide a situational analysis of the regulatory framework of food marketing policies targeting children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR). A semi structured questionnaire was shared with the focal points of EMR member states inquiring about the reforms and monitoring initiatives in place. Electronic databases were searched for relevant publications between 2005 and 2021. Results revealed that even though 68% of countries discussed the recommendations, progress toward the WHO set goals has been slow with only 14% of countries implementing any kind of restrictions and none executing a comprehensive approach. Reforms have focused on local television and radio marketing and left out several loopholes related to marketing on the internet, mobile applications, and cross border marketing. Recent monitoring initiatives revealed a slight improvement in the content of advertised material. Yet, unhealthy products are the most promoted in the region. This review identified the need to intensify the efforts to legislate comprehensive food marketing policies within and across EMR countries.

Introduction

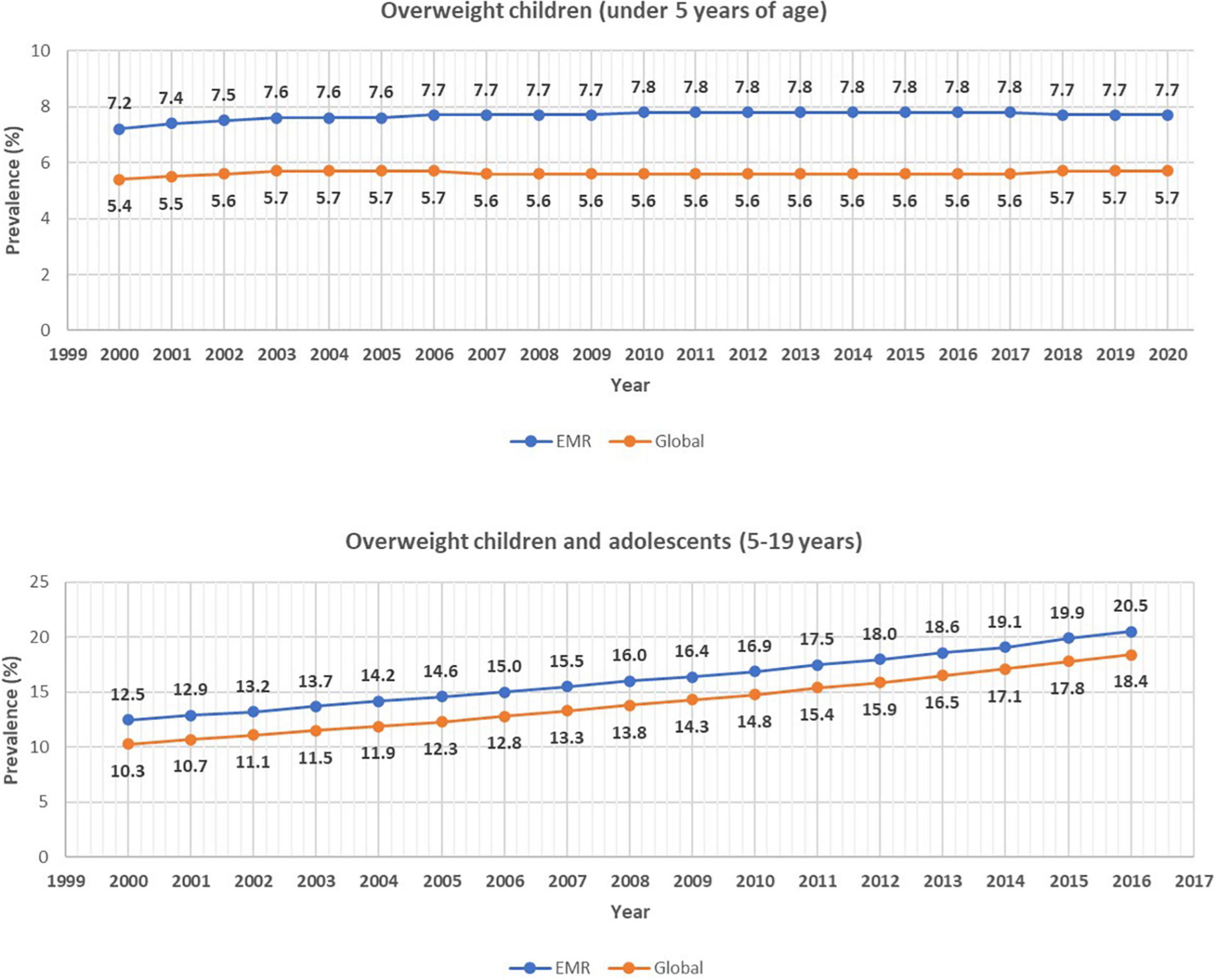

The Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) has been facing many health challenges due to unhealthy lifestyle patterns, political instability, and fragile health systems (1, 2). As a result, chronic diseases have increased from 6% in 1980 to 14% in 2014 and the burden of obesity on Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) grew from 4% in 1990 to 8% in 2013 (3, 4). Obesity has been weighing heavily on children in the region. Compared to 5.7% of children under five around the world, 7.7% of EMR children were overweight or obese in 2020 (5, 6) (Figure 1). Similarly, the prevalence rate of overweight and obesity for children and adolescents aged 5-19 years in 2016 was 20.5% in the EMR compared to 18.4% worldwide (5) (Figure 1). The EMR has five [Kuwait, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Qatar, Oman, Libya] and two (Oman and Iran) out of the ten countries in the world with the highest prevalence and relative change in overweight children aged 2–4, respectively (7). Malnutrition manifestations differ based on the countries’ Human Development Index, progress in nutrition transition, political stability, environmental status, mean population age, etc. (3, 8). Low- and middle-income countries have been struggling with the “double burden” of malnutrition with co-existence of wasting and obesity within the same population (9, 10).

Figure 1. Prevalence of overweight children under five years (top panel) and aged 5–19 years (bottom panel) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) and globally. Overweight was defined as % weight for height 2 standard deviations above median for children under 5 years of age and as 1 standard deviation above median body mass index for age for children and adolescents aged 5–19 years. Source: Numbers have been extracted from the Global Health Observatory [5, 6].

Children, starting from a young age, are exposed to food marketing at home, nurseries, schools, and in public spaces, most of which are for products high in added saturated and/or trans fatty acids, sugar and sodium (HFSS) (11, 12). Marketing of food and beverages influences children’ knowledge of products, preferences, acquisitions, and dietary patterns (13–16). In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) called on the private sector to adopt a responsible marketing approach toward children (17). Beyond corporate social responsibility, the need for legal reforms to enhance dietary patterns has been highlighted recurrently (18, 19). In 2010, the World Health Assembly (WHA) adopted the WHO Set of Recommendations on Marketing of Foods and Non-alcoholic Beverages to Children (WHO Recommendations) and called on all countries to integrate policies to regulate the marketing of unhealthy foods to young populations (20). Best practice policies to protect children up to 18 years from the harmful impact of food marketing include legislation of all relevant foods, cover all forms of marketing and are robustly monitored and enforced with meaningful sanctions (21). A WHO report assessed the implementation of marketing restriction in the EMR up to 2018 and found a limited integration of reforms in the legal framework of the EMR region (22). This project is timely in view of the scarcity of scholarly articles assessing the progress of the EMR countries in implementing the WHO Recommendations. The aim of this paper is to provide an updated situational analysis of the progress of EMR countries in integrating a regulatory framework of food marketing policies targeting children.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources: Questionnaire and Search Strategy

A semi-structured questionnaire evaluating countries’ progress toward the WHA recommendations was administered on all EMR country representatives (selected from the countries ministries of health and/or the WHO country offices). The questionnaire was shared by email via the WHO EMR office in December 2021 in Arabic and English languages (English version available in Supplementary Material). It inquired from country representatives if restrictions on marketing of unhealthy food and beverage items to children (up to 18 years old) have been discussed and/or implemented, on the presence of voluntary pledges by the food industry, on the stakeholders involved in the relevant discussions and legislations, and on the monitoring initiatives undertaken by governmental and/or non-governmental bodies. The extent of the implementation of a recommendation/discussion/legislation across the region was calculated by dividing the number of countries which implemented a recommendation by the total number of member states in the EMR region (n = 22). Results were rounded to the nearest integer. Moreover, a systematic literature search was implemented on the following databases: Medline, PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Google Scholar, Al Manhal, Arab World Research Source, E-Marefa, and Iraqi Academic Scientific Journals. The last four databases were chosen as they provide data sources that are specific to the region, since Arabic is the language most spoken in EMR countries. Manual search was conducted on the websites of the WHO and Food and Agriculture Organization. Inclusion criteria included manuscripts, governmental documents, reforms, and policy briefs in countries of the EMR. The following terms were used: “Eastern Mediterranean Region” countries OR “Middle East” OR each state alone AND “Children” OR “Child” OR “Toddler” AND “Diet” OR “Diet Therapy” OR “Nutrient” OR “Consumption” OR “Saturated Fat” OR “Trans Fat” OR “Sodium” OR “Salt” OR “Sugar” OR “Juice” OR “Sugar Sweetened Beverages” OR “Soft Drinks” OR “Obesity” OR “Overweight” AND “Marketing” OR “Promotion” OR “Advertisements” OR “Policy” OR “Reform” OR “Pledge.” The literature search was restricted to the Arabic, English and French languages and to publications between January 1, 2005, until November 7, 2021. Individual EMR countries included in the search were selected based on the WHO country categorization: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Jordan, KSA, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Morocco, Oman, Occupied lands of Palestine, Pakistan, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen (23).

Food Marketing Regulatory Framework: Defining Concepts

In order to understand this situational analysis, we define in this section a few concepts relevant to the food marketing regulatory framework. The effectiveness of marketing is a function of two elements: the exposure of children to the marketing message and the power of the communication. The WHO defines power in marketing as the “content, design and creative strategies used to target and persuade” (20). Marketing is not limited to advertisements. It incorporates promotion on several media such as television, radio, billboard, magazine, packaging design, point of sale, and digital media, including mobile applications, “advergames” and blogs.

The industry and the government are the main regulatory actors that design and implement food marketing restrictions. Regulation can be done in a voluntary approach when the industry initiates and monitors the restrictions or in a mandatory manner when governmental entities design the policies and implement judiciary actions (24). Comprehensive and stepwise approaches are two commonly employed methods for integrating legal reforms. While the former method is more inclusive, the latter may be more practical to stakeholders as it progresses in phases by gradually incorporating additional outlets, food and beverage items, marketing mediums and/or settings (25). The WHO favors the comprehensive approach as the stepwise method may leave loopholes in the regulatory framework that the food industry can benefit from (26). Yet, if the comprehensive approach is not deemed feasible, the initiation of a stepwise approach is favored over the absence of any implementation (26).

Nutrient profiling is the practice of classifying a product as “healthy” or “unhealthy” based on its salt, fat and sugar content (27). Profiling facilitates the identification of products that need prohibition by legal reforms by laying a common framework for policy makers (28). The WHO office in the EMR adopted the European nutrient profiling model that assesses 18 food categories and identifies products with elevated HFSS (27).

Health Reforms in the Eastern Mediterranean Region

Legal Reforms

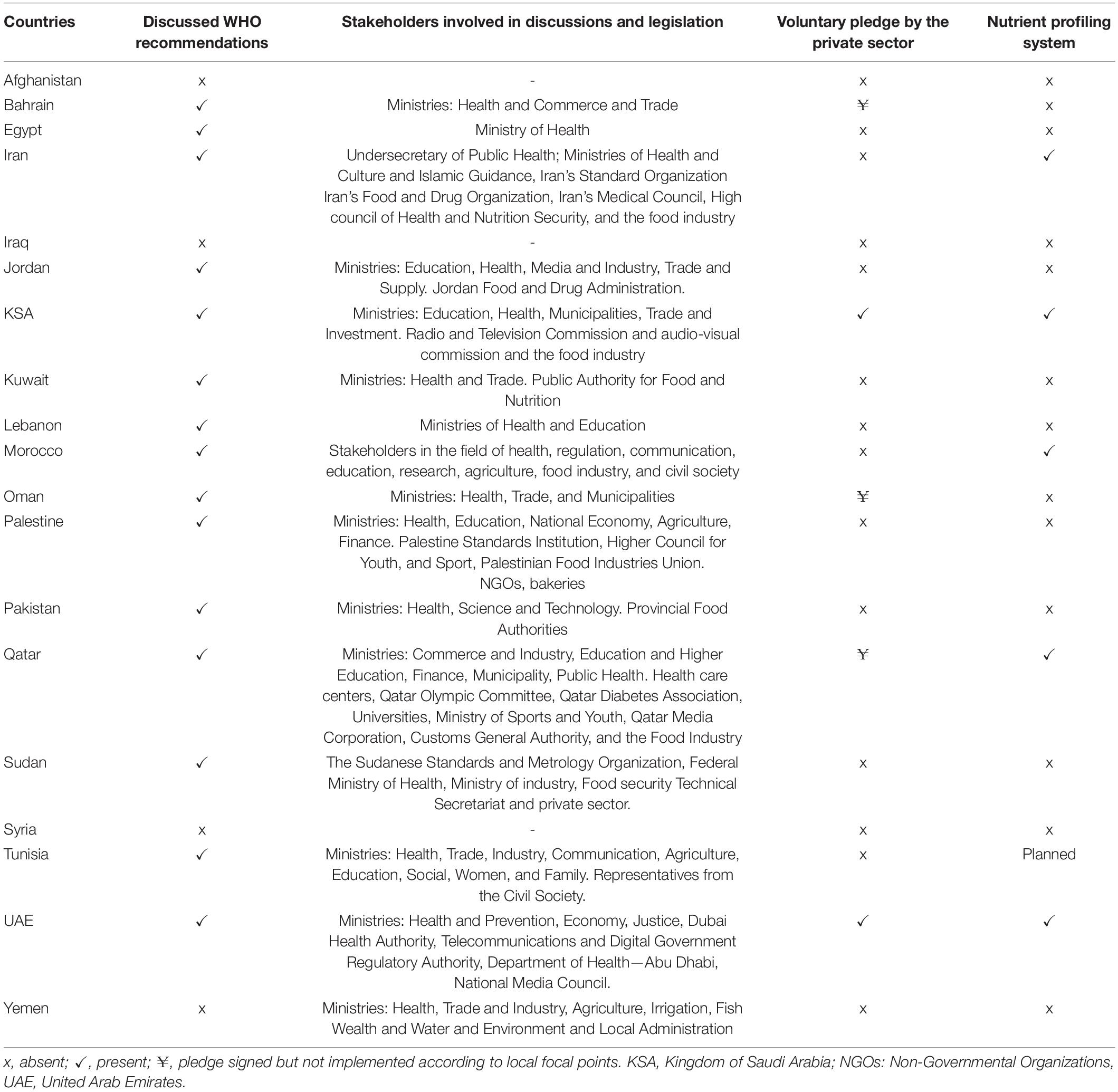

Table 1 provides an overview of the actions taken by EMR member states to prepare for the endorsement of the WHO Recommendations on marketing restrictions of unhealthy foods to children based on the questionnaire collected from country representatives. No information could be collected from the following countries: Djibouti, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, and Somalia. Most countries (68%) discussed the WHO Recommendations on regulating marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages (Table 1). Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen reported not having discussed the Recommendations. Most countries that discussed the marketing restrictions did so after 2016. Ministries of health were the common stakeholder in the discussions and legal reforms. Other stakeholders included ministries of education, of trade and commerce, and municipalities and radio and television commissions. Voluntary pledges by the food industries were implemented in the KSA and UAE and less than a quarter of EMR countries (23%) adopted a nutrient profiling system (Table 1) (22).

Table 1. Summary of the actions taken by EMR countries to prepare and complement the implementation of legal reforms of marketing restrictions of unhealthy foods and beverages to children.

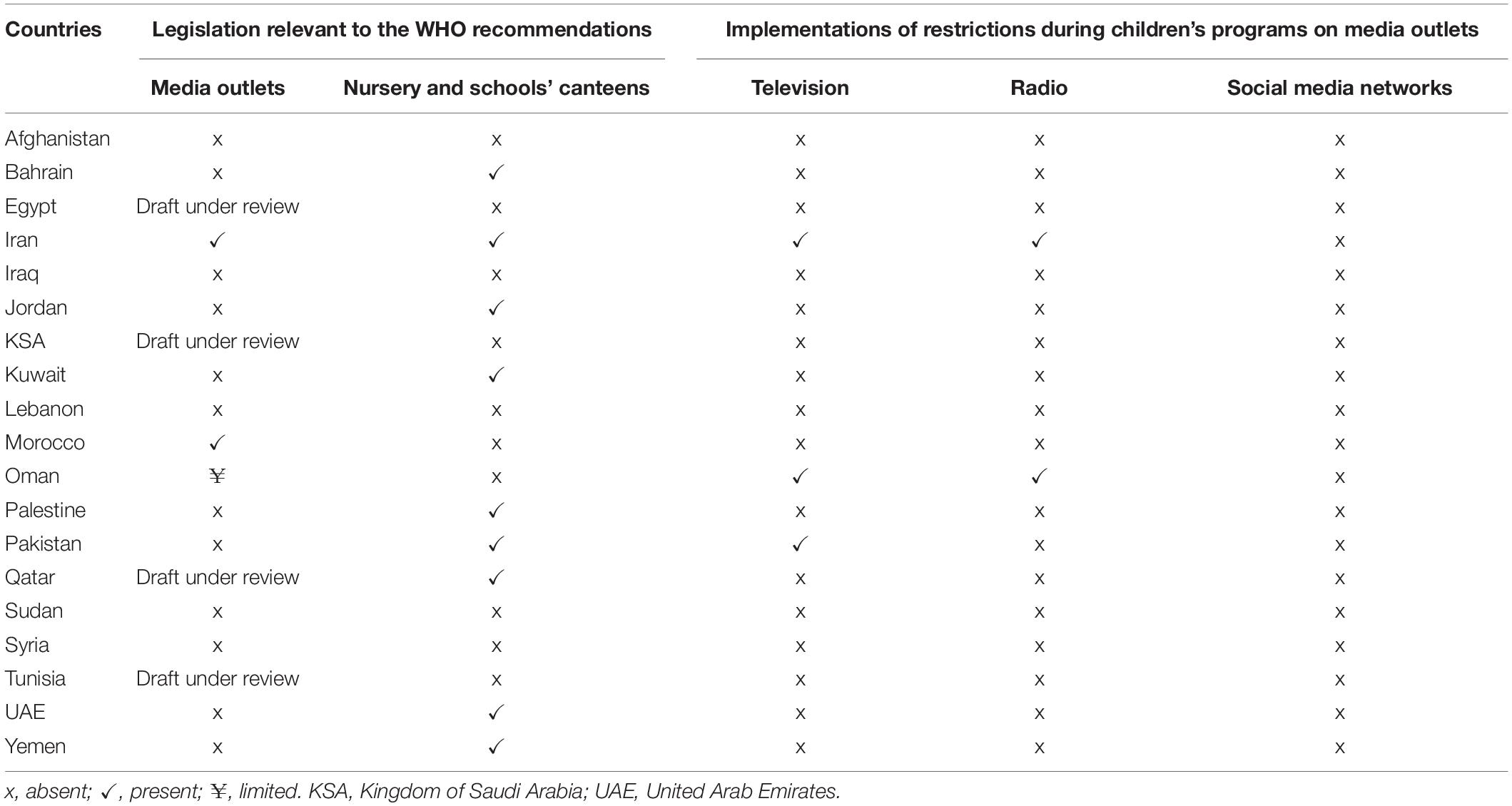

Table 2 presents an overview of the legislation and implementation of restrictions relevant to the WHO Recommendations. While 14% had legislation for media outlets, 41% of countries had restrictions in nurseries and schools’ canteens (Table 2). The mapping exercise revealed that no country implemented a comprehensive regulatory approach to limit marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children on media outlets. Iran, KSA, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Tunisia, and the UAE started planning and/or implementing some levels of reforms. Iran adopted the widest level of reforms compared to other counties. The decision to ban all advertisements from kindergartens, schools, and public places where children are present was ruled in 1978 and reinforced in 2010. In 2009, it was prohibited to include children in advertisements. In 2016, a decision to ban promotion of food products during children’s TV and radio programs and to avoid featuring obese children in advertisements was taken. In 2020, a legislation targeting the general public identified 19 HFSS food products as unhealthy items that should not be marketed (22, 29, 30). Reforms included nutrient profiling and involved several governmental bodies such as the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Industry, National Standards Organization, and The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (22, 29). Yet, disrespect of these reforms has not been linked to any judiciary action. In Pakistan, provincial food authorities banned sale of soft drinks in and around teaching institutions. Following this decision, local media outlets took the initiative to stop advertising for unhealthy food and beverage items during children television programs. No relevant legislation has been passed in the country. In Oman, in compliance with the “Child Law,” the Ministry of Information passed legislation banning the promotion of food products during children’s programs on television and radio stations and prohibiting advertisement of printed material related to medical and pharmaceutical products without the approval of the Ministry of Health. Reforms in Pakistan and Oman have major loopholes, neither do they incorporate a step for nutrient profiling, nor do they include components of marketing on social media networks, roads, supermarkets, and restaurants. Moreover, the definitions of unhealthy food items in Pakistan differed based on the provinces with some limiting unhealthy items to “sugary foods and drinks” while others employed wider definitions that incorporated sodium rich snacks as well. Some countries like Morocco and UAE adopted nutrient profiling and legislated regulatory actions for marketing of unhealthy items to children but have not implemented relevant reforms yet. The UAE legislation provides general guidelines on the need to prohibit marketing of unhealthy foods to children but does not incorporate any implementation mechanism. Legislation was hence not considered present at this point (Table 2). Egypt, the KSA, Qatar and Tunisia have policy briefs currently under revision by their respective governments (Table 2). Whereas KSA and Qatar adopted nutrient profiling systems, Tunisia prepared one but has not adopted it yet and Egypt neither adopted nor implemented any system (Table 1) (31). Qatar’s proposed legislation involves a ban of children’s toy incentives in fast food restaurants, prohibition of advertising of unhealthy foods to children, regulation of the promotions of unhealthy foods in or around schools. Tunisia’s National Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology drafted a policy brief for restriction of marketing of food and beverages on television, on the internet and during sports and cultural festivities (22). Yet, the proposed policy does not impose restrictions on product packaging and on displaying cartoon characters on products, which may reduce its effectiveness.

Table 2. Summary of the legislation and restrictions implemented in canteens of educational facilities and on media outlets.

Weak multisectoral collaboration is a challenge identified in the implementation of policies across the region. A recent scoping review revealed that regulation of marketing of food is weakly implemented in Iran due to weak scientific criteria in the legal reforms, lack of judiciary actions linked to violations, poor collaboration across sectors, and inadequate monitoring (30). Qualitative studies among stakeholders of childhood obesity in Iran criticized the weak coordination between stakeholders and the top-down approach in policy making. On the field stakeholders are poorly consulted, leading to weak implementation of these reforms (32, 33). In Pakistan, a content analysis of infant and children feeding policies identified the lack of clarity of the responsibilities of collaborators and poor stakeholders’ collaboration as the areas that need to be strengthened (34).

Monitoring Initiatives

Governmental and academic bodies assessed the nature and quality of food marketing on media outlets in the EMR countries. A content analysis of the advertisements mostly viewed by a sample of 7–12-year-old children on local television channels in Egypt in 2015–2016 revealed that 74% of commercials were for unhealthy products such as sweets, chips and soft drinks (35). In Oman, a review of Pan-Arab TV stations popular among children and local radio and print media in 2015–2016 showed that print media advertisements rarely promoted unhealthy snacks but 71% of television and 44% of radio advertisements promoted HFSS items (36), with the majority of promotions being between children’s programs. Sweetened beverages were the most commonly sold products to students in stores around schools. These stores included promotions on HFSS products and featured cartoon characters for products at the point of sale (36). In Lebanon, an assessment of marketing on local television channels conducted in 2016–2017 revealed that 100 and 85% of commercials advertised during children’s programs and general audience programs were for unhealthy products, respectively. Moreover, around 80% of the commercials that included a health claim were for unhealthy food and beverages (37). An analysis of Iranian television commercials in 2016 revealed that the length of food and beverage advertisements was significantly shorter compared to previous years. Yet, 60% of television commercials remained food related, promoted items elevated in sugar and sodium, and favored sweetened fruit products over natural fruits (38). In KSA the Saudi Food and Drug Authority identified the YouTube channels that are most viewed by children in the country between years 2016 and 2021. A review of videos on these channels revealed that HFSS food items are commonly promoted through commercials, promotion codes, video characters consuming them prior to a competition, etc. (39). Moreover, a content analysis of printed and social media coverage of childhood obesity in the UAE revealed that excess weight among children was commonly presented as the result of bad parents’ choices. The influence of structural elements related to policies and the role of the food and beverage industry was found to be minimized in the media (40).

Self-Regulation of the Food Industry

Prior to the governments’ policy changes, the food industry had responded to a call by the WHO in 2004 to regulate food marketing. Eight global food and beverage companies in countries of the Gulf Country Cooperation signed the Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing to Children Pledge in 2010 (41). Through this pledge, companies committed to market products deemed healthy to children under 12 years of age and to stop sales of unhealthy products in primary schools. This pledge was further strengthened in 2016 with companies harmonizing the evaluation criteria employed (42). In 2020, the International Food and Beverage Alliance’s (IFBA) compliance monitoring report to the pledge in the KSA and UAE revealed a 100% adherence rate with food marketing on television, printed material and the internet (43). Yet, these pledges and monitoring initiatives have been criticized for leaving major loopholes (22). While the IFBA pledges cover radio, television, company owned websites, cinemas, and mobile marketing, they exclude points of sale marketing, sponsorship of pediatric activities and are limited to children’s programs (22). Since children tend to watch programs that are not specifically for their age group, to access websites other than those owned by companies’ websites, and to attend to public spaces that do not have marketing restrictions, the latter monitoring studies can underestimate the rate of children exposure to the marketing of unhealthy products (22, 44). Moreover, the IFBA pledge limits its scope to children under 12 years of age and leaves out the age group of 12–18 years who is also much affected by marketing of HFSS (45).

Discussion

Marketing of Unhealthy Food and Beverages in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Where Do We Stand Today?

This review showed legislative action to regulate food marketing to children is very limited in the EMR. In the absence of comprehensive marketing legislation approaches, a few countries started implementing legislative actions through a stepwise approach and a few others have started planning for the change.

This report highlighted how the few legal reforms implemented have been mainly limited to local television and radio outlets. This finding identifies several challenges. First, despite the rise in the adoption of digital media and the displacement of legacy media, mobile applications and online outlets and products’ packaging have been frequently omitted from legal reforms (46). Yet, online platforms have been found to incorporate food and beverage advertisements of non-core food more than other marketing outlets (47). Digital media can be even more dangerous than television and radio outlets as it employs personal data collected on children’s behavioral patterns, interest, geolocation, etc. (48). It can hence exploit children using identified vulnerabilities. The limited focus on online outlets devices, print and packaging in legal reforms is not limited to the EMR; it’s a common gap identified worldwide (49). Second, limiting legislative measures and monitoring to local or national media channels creates a loophole that the food industry can take advantage of. As many EMR countries speak the same languages, advertisements on regional channels can influence the behavior of children across states’ borders, a phenomenon defined as cross-border marketing. Moreover, in the EMR, regional televisions have greater funding and influence than most national channels (22). At a WHO regional virtual meeting on childhood obesity in the EMR, stakeholders identified digital marketing as a challenging medium to target and cross-country collaboration as an important component to drive progress in reaching the WHO goals on marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children (50). Participants saw that the difficulty of integrating legal reforms on digital media should not stop them from initiating legal reforms on traditional forms of marketing—such as television, radio and print advertising and marketing in or around schools. Country representatives identified mapping of digital marketing in the region and receiving training on monitoring methodology on food marketing as pre-requisites to reaching regional goals (50).

The WHO EMR office assessed the adoption of nutrient profiling in years 2013, 2015, and 2017 (27). This study revealed a marked improvement in the adoption of nutrient profiling with 23% of states implementing them as a pre-requisite for marketing regulations. Moreover, adoption of reforms is likely to be associated with the countries’ political stability, Gross Domestic Product, and the level of government commitment. Indeed, countries in political instability like Djibouti, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen have not adopted any kind of restrictions. Food authorities are likely addressing the urgent crises in their territories. Countries that have taken actions toward regulating marketing of non-nutritious products are mainly middle- or high-income countries. This reflects the abundance of resources that these countries can allocate to combat childhood obesity compared to low-income states.

We learn from other countries around the globe that reliance on the industry’s self-regulation has yielded limited success. Even though the food industry funded reports suggest an impressive level of compliance with voluntary pledges, there exists a great deal of discrepancy with the results of scholarly articles and evaluations (51). Companies take advantage of loopholes to attract children to their products, implement lenient restrictions and assess compliance “mercifully” (52). An evaluation of products marketed to children in Canada revealed that 73% of unhealthy products were for companies which have committed to pledges on responsible marketing (53). Even though reliance on the industry’s self-regulation is not recommended, experts agree on the importance of collaboration with the private sector for the success of any change. Involvement of the industry and governmental entities in the regulatory design has been promoted by the theory of Responsive Regulation and has proven successful in nutritional legal reforms (54–57). As the risk of conflict of interest from engagement with the food industry is elevated, the WHO recommends implementation of safeguards to prevent and manage conflicts of interest in the area of nutrition, and this is important to protect against any involvement that may undermine governments’ efforts to protect children from marketing (58).

Recommendations

The lack of overall progress to date, and the finding that no country in the EMR has implemented a comprehensive approach, suggest that the recommendations of the WHO 2018 report on implementation of marketing restrictions in the region remain largely relevant (22). EMR countries are urged to develop as comprehensive approach as possible on unhealthy food marketing to children, tackling both exposure and power. Countries are called on to form multisectoral working groups to develop regulation and to build legal capacity so that those responsible for drawing up the draft legislation can withstand potential legal challenges. Countries should include monitoring and evaluation processes to regularly assess if the implemented reforms are efficient in reaching desired goals. The WHO has encouraged countries to adopt an evidence-based nutrient profiling system to identify items covered by the marketing ban. If a comprehensive approach is not feasible, countries were advised not to delay their intervention and to implement a stepwise policy, focusing on the most popular media where children are exposed to marketing, until a comprehensive approach becomes feasible. Finally, regional collaboration and cooperation are vital to safeguard youngsters from cross-border marketing (22).

Limitations and Strengths

This study provides an overview from governmental and academic bodies on the status of EMR countries in reaching goals for marketing legal reforms. Its strength is in filling an important literature gap and in employing a solid methodology. A systematic search on major databases and governmental websites was applied to yield a comprehensive overview on the subject. For completeness and since such legal reforms may not be found in scientific databases, the search was coupled with a survey of country representatives. The study has several limitations as well. Even though we employed a systematic search strategy, articles were not screened in duplicates. Moreover, data was missing from some countries due to lack of policy digitization and the lack of monitoring studies in these nations. Lastly, many countries lacked data on the extent of implementation of the legal reforms.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first scholarly article that analyzes the regulatory framework of food marketing restrictions toward children in the EMR. Reinforcing the results of the 2018 WHO report (21), this study revealed that the road toward achieving the WHO recommendations for marketing of unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children has been rarely traveled in the EMR. The majority of countries only discussed the WHO Recommendations and have not taken any legal action. Countries adopting legal reforms are doing so in a stepwise approach. Implemented reforms have been limited to the traditional media, leaving out the more influential media outlets. An analysis of the marketing media children in EMR countries are exposed to showed that most commercials are for unhealthy products even in countries where legislation is present. EMR states should coordinate among stakeholders within their countries and across the region to legislate food marketing policies in view of the heavy burden of childhood obesity and the impact of marketing on children’s dietary patterns.

Author Contributions

AA-J and JJ: conceptualization, methodology, and writing—review and editing. JJ: investigation and writing—original draft preparation. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Author Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the World Health Organization or the other institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge representatives from the Ministries of Health and WHO country offices without whom this publication could not have been possible. Country representatives listed in alphabetical order: Ms. Amira Ali, Dr. Khawaja Masuood Ahmed, Dr. Buthaina Ajlan, Mr. Mousa AL-Halaika, Ms. Tagreed Mohammad Alfuraih, Dr. Salima Al Maamari, Dr. Nawal Alqaoud, Ms. Afra Salah AlSammach, Ms. Hend Ali Al-Tamimi, Dr. Laila El Ammari, Dr. Jalila El Ati, Mr. Hsan Ben Jemaa, Dr. Mahmoud Boza, Dr. Gihan Fouad, Dr. Huda Kambal, Dr. Hind Khalid, Ms. Marwa Khammassi, Ms. Yasmin Rihawi, Ms. Sonia Sassi, Dr. Mohammad Qasem Shams, Mr. Mohammed Shroh, Ms. Edwina Zoghbi. Ms. Karen McColl for her valuable review of the manuscript and Dr. Marwa Abbas for her support in the figures’ preparation. Ms. Noor Hamoui for her creative design of the graphical scientific abstract of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.868937/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Moradi-Lakeh M, El Bcheraoui C, Charara R, Khalil I, Afshin A, et al. Burden of cardiovascular diseases in the eastern Mediterranean region, 1990–2015: findings from the global burden of disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health. (2018) 63:137–49. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-1012-3

2. Mandil A, Chaaya M, Saab D. Health status, epidemiological profile and prospects: Eastern Mediterranean region. Int J Epidemiol. (2013) 42:616–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt026

3. Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, El Bcheraoui C, Moradi-Lakeh M, Khalil I, et al. Health in times of uncertainty in the eastern Mediterranean region, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet Glob Health. (2016) 4:e704–13. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30168-1

4. Alwan A, McColl K, Al-Jawaldeh A, James P. World Health Organization, Proposed policy priorities for preventing obesity and diabetes in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017).

5. World Health Organization. Body mass index – BMI. in: TGH Observatory, editor. Nutrition. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

6. World Health Organization. Children Aged <5 Years Overweight. Data by Country. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

7. O.W.I. Data, Prevalence of Overweight in Children Aged 2-4 (%) – PAST – Unscaled. Oxford: U.O.O. Oxford Martin School (2021).

8. Nasreddine L, Ayoub JJ, Al Jawaldeh A. Review of the nutrition situation in the eastern Mediterranean region. East Mediterr Health J. (2018) 24:77–91. doi: 10.26719/2018.24.1.77

9. Ghattas H, Jamaluddine Z, Akik C. Double burden of malnutrition in children and adolescents in the Arab region. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2021) 5:462–4. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00162-0

10. Popkin BM, Corvalan C, Grummer-Strawn LM. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet. (2020) 395:65–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32497-3

11. Signal LN, Stanley J, Smith M, Barr MB, Chambers TJ, Zhou J, et al. Children’s everyday exposure to food marketing: an objective analysis using wearable cameras. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2017) 14:137. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0570-3

12. Dalton MA, Longacre MR, Drake KM, Cleveland LP, Harris JL, Hendricks K, et al. Child-targeted fast-food television advertising exposure is linked with fast-food intake among pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:1548–56. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000520

13. Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Ann Rev Public Health. (2009) 30:211–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100304

14. Sadeghirad B, Duhaney T, Motaghipisheh S, Campbell N, Johnston B. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Rev. (2016) 17:945–59. doi: 10.1111/obr.12445

15. Pournaghi Azar F, Mamizadeh M, Nikniaz Z, Ghojazadeh M, Hajebrahimi S, Salehnia F, et al. Content analysis of advertisements related to oral health in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. (2018) 156:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.12.012

16. Pourmoradian S, Ostadrahimi A, Bonab AM, Roudsari AH, Jabbari M, Irandoost P. Television food advertisements and childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. (2021) 91:3–9. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000681

17. World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

18. WHO. Montevideo Roadmap 2018-2030 on NCDs As A Sustainable Development Priority WHO Global Conference on Non-communicable Diseases Pursuing Policy Coherence to Achieve SDG Target 3.4 on NCDs (Montevideo, 18-20 October 2017). Montevideo, UY: WHO (2017).

19. Magnusson RS, McGrady B, Gostin L, Patterson D, Abou Taleb H. Legal capacities required for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Bull World Health Organ. (2019) 97:108–17. doi: 10.2471/blt.18.213777

20. World Health Organization. Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010).

21. Granheim SI, Vandevijvere S, Torheim LE. The potential of a human rights approach for accelerating the implementation of comprehensive restrictions on the marketing of unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. Health Promot Int. (2019) 34:591–600. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dax100

22. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern, Implementing the WHO Recommendations on the Marketing of Food and Non-alcoholic Beverages to Children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, World Health Organization. Cairo: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2018).

24. Ngqangashe Y, Goldman S, Schram A, Friel S. A narrative review of regulatory governance factors that shape food and nutrition policies. Nutrition Reviews (2022) 80:200–14. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuab023

25. Garde A, Byrne S, Gokani N, Murphy B. A Child Rights-Based Approach to Food Marketing A Guide for Policy Makers. New York, NY: UNICEF (2018).

26. World Health Organization. A Framework for Implementing the Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2012).

27. Rayner M, Jewell J, Al Jawaldeh A World Health Organization. Nutrient Profile Model for the Marketing of Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, World Health Organization. Cairo: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2017).

28. Rayner M. Nutrient profiling for regulatory purposes. Proc Nutr Soc. (2017) 76:230–6. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117000362

29. Abachizadeh K, Ostovar A, Pariani A, Raeisi A. Banning advertising unhealthy products and services in Iran: A one-decade experience. Risk Manag HealthcPolicy. (2020) 13:965. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S260265

30. Omidvar N, Al-Jawaldeh A, Amini M, Babashahi M, Abdollahi Z, Ranjbar M. Food marketing to children in Iran: regulation that needs further regulation. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. (2021) 9:712–21. doi: 10.12944/CRNFSJ.9.3.02

32. Taghizadeh S, Farhangi MA, Khodayari-Zarnaq R. Stakeholders perspectives of barriers and facilitators of childhood obesity prevention policies in Iran: a delphi method study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:2260. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12282-7

33. Taghizadeh S, Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Farhangi MA. Childhood obesity prevention policies in Iran: a policy analysis of agenda-setting using Kingdon’s multiple streams. BMC Pediatr. (2021) 21:250. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02731-y

34. Mahmood H, Suleman Y, Hazir T, Akram DS, Uddin S, Dibley MJ, et al. Overview of the infant and young child feeding policy environment in Pakistan: federal, Sindh and Punjab context. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:474. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4341-5

35. Rady M. Food & Beverages Advertising Viewed by Egyptian children: A content Analysis. Cairo: American University in Cairo (2016).

36. Al-Ghannami S, Al-Shammakhi S, Al Jawaldeh A, Al-Mamari F, Gammaria I. Al, Al-Aamry J, et al. Rapid assessment of marketing of unhealthy foods to children in mass media, schools and retail stores in Oman. East Mediterr Health J. (2019) 25:820–7. doi: 10.26719/emhj.19.066

37. Nasreddine L, Taktouk M, Dabbous M, Melki J. The extent, nature, and nutritional quality of foods advertised to children in Lebanon: the first study to use the WHO nutrient profile model for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Food Nutr Res. (2019) 63. doi: 10.29219/fnr.v63.1604

38. Hajizadehoghaz M, Amini M, Abdollahi A. Iranian television advertisement and children’s food preferences. Int J Prev Med. (2016) 7:128. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.195825

40. Awofeso N, Imam SA, Ahmed A. Content analysis of media coverage of childhood obesity topics in UAE newspapers and popular social media platforms, 2014-2017. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2019) 8:81–9. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.100

41. Hawkes C, Harris JL. An analysis of the content of food industry pledges on marketing to children. Public Health Nutr. (2011) 14:1403–14. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011000607

42. IFBA. Global Food and Beverage Companies in the GCC Renew and Strengthen Their Voluntary Pledge to Restrict Marketing to Children. Bahia: IFBA (2016).

43. IFBA. Compliance Monitoring Report For the International Food & Beverage Alliance on UAE & KSA Advertising in Television, Print and Internet. Bahia: IFBA (2020).

44. Harris JL, Sarda V, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Redefining “child-directed advertising” to reduce unhealthy television food advertising. Am J Prevent Med. (2013) 44:358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.039

45. Kraak VI, Rincón-Gallardo Patiño S, Sacks G. An accountability evaluation for the international food & beverage alliance’s global policy on marketing communications to children to reduce obesity: a narrative review to inform policy. Obes Rev. (2019) 20:90–106.

46. Twenge JM, Martin GN, Spitzberg BH. Trends in US Adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: the rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychol Popular Media Cult. (2019) 8:329. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000203

47. Tan L, Ng SH, Omar A, Karupaiah T. What’s on YouTube? A case study on food and beverage advertising in videos targeted at children on social media. Childhood Obes. (2018) 14:280–90. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0037

48. Tatlow-Golden M, Boyland E, Jewell J, Zalnieriute M, Handsley E, Breda J, et al. Tackling Food Marketing to Children in a Digital World: Trans-Disciplinary Perspectives. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

49. Taillie LS, Busey E, Stoltze FM, Dillman Carpentier FR. Governmental policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children. Nutr Rev. (2019) 77:787–816. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz021

50. WHO. Meeting on Childhood Obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Virtual Meeting. Geneva: WHO (2021).

51. Galbraith-Emami S, Lobstein T. The impact of initiatives to limit the advertising of food and beverage products to children: a systematic review. Obes Rev. (2013) 14:960–74. doi: 10.1111/obr.12060

52. Fleming-Milici F, Harris JL. Food marketing to children in the United States: can industry voluntarily do the right thing for children’s health? Physiol Behav. (2020) 227:113139. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113139

53. Vergeer L, Vanderlee L, Potvin Kent M, Mulligan C, L’Abbé MR. The effectiveness of voluntary policies and commitments in restricting unhealthy food marketing to Canadian children on food company websites. Appl Physiol Nutr Metabol. (2019) 44:74–82. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2018-0528

54. Bin Sunaid FF, Al-Jawaldeh A, Almutairi MW, Alobaid RA, Alfuraih TM, Bin Saidan FN, et al. Saudi Arabia’s healthy food strategy: progress & hurdles in the 2030 road. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2130.

55. Gibson S, Ashwell M, Arthur J, Bagley L, Lennox A, Rogers PJ, et al. What can the food and drink industry do to help achieve the 5% free sugars goal? Perspect Public Health. (2017) 137:237–47. doi: 10.1177/1757913917703419

56. Lee Y, Yoon J, Chung S-J, Lee S-K, Kim H, Kim S. Effect of TV food advertising restriction on food environment for children in South Korea. Health Promot Int. (2017) 32:25–34.

Keywords: Eastern Mediterranean Region, marketing, childhood obesity, media, unhealthy food

Citation: Al-Jawaldeh A and Jabbour J (2022) Marketing of Food and Beverages to Children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Situational Analysis of the Regulatory Framework. Front. Nutr. 9:868937. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.868937

Received: 18 February 2022; Accepted: 26 April 2022;

Published: 18 May 2022.

Edited by:

Farhana Akter, Chittagong Medical College, BangladeshReviewed by:

Tim Lobstein, World Obesity Federation, United KingdomRahnuma Ahmad, Medical College for Women and Hospital, Bangladesh

Ayukafangha Etando, Eswatini Medical Christian University, Eswatini

Copyright © 2022 Al-Jawaldeh and Jabbour. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jana Jabbour, amphYmJvdXJAbXVicy5lZHUubGI=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Ayoub Al-Jawaldeh

Ayoub Al-Jawaldeh Jana Jabbour

Jana Jabbour

Riyadh: SFDA (2021).

Riyadh: SFDA (2021).