94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Nutr., 16 March 2022

Sec. Eating Behavior

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.860259

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Food Supply, Dietary Patterns, Nutrition and Health: Volume 2View all 11 articles

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has caused striking alterations to daily life, with important impacts on children's health. Spending more time at home and out of school due to COVID-19 related closures may exacerbate obesogenic behaviors among children, including consumption of sugary drinks (SDs). This qualitative study aimed to investigate effects of the pandemic on children's SD consumption and related dietary behaviors. Children 8–14 years old and their parent (n = 19 dyads) participated in an in-depth qualitative interview. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and independently coded by two coders, after which, emergent themes and subthemes were identified and representative quotations selected. Although increases in children's SD and snack intake were almost unanimously reported by both children and their parents, increased frequency of cooking at home and preparation of healthier meals were also described. Key reasons for children's higher SD and snack intake were having unlimited access to SDs and snacks and experiencing boredom while at home. Parents also explained that the pandemic impacted their oversight of the child's SD intake, as many parents described loosening prior restrictions on their child's SD intake and/or allowing their child more autonomy to make their own dietary choices during the pandemic. These results call attention to concerning increases in children's SD and snack intake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intervention strategies to improve the home food environment, including reducing the availability of SDs and energy-dense snacks and providing education on non-food related coping strategies are needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the daily lives of families in the United States (U.S.) and worldwide. Public health guidance to stay at home and practice social distancing has had marked impacts on children's weight (1) and has likely influenced children's diet-related behaviors (2). Although preparation of meals at home is typically associated with lower intakes of nutrients of concern including salt, saturated fat, and added sugar (3, 4), findings of studies examining impacts of COVID-19 related stay-at-home orders on dietary intake among adults are mixed (5), and evidence on pandemic-related dietary changes among children in the U.S. is lacking.

Recent survey data in the U.S. indicate that about half of U.S. adults reported consuming more “unhealthy snacks/desserts” and approximately one-third of U.S. adults reported drinking more SDs, during, compared to before, the pandemic (6). Given that excess added sugar intake is a well-established risk factor for obesity and cardiometabolic disease (7) and children's SD intake already exceeded recommendations prior to the pandemic (8), these trends are of particular public health concern. Recent studies have reported increases in SD intake during the pandemic among U.S. adults (6, 9), yet studies examining changes in children's SD intake during the pandemic, to our knowledge, have not been conducted.

Elucidating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's SD consumption is paramount because alterations in dietary behaviors during the pandemic may persist longer-term. Furthermore, time away from school and structured activities is known to exacerbate key risk factors for overweight and obesity among children (10, 11). For example, poorer dietary intake, including higher consumption of SDs and highly processed snack foods and desserts (“junk food”), is reported during the summer months, along with greater sedentary time and use of screens (e.g., television, video games, computers) (11). These patterns of obesity risk behaviors may be worsened in the context of COVID-19 related closures and stay-at-home orders, given limited access to fresh groceries, and cancellation of youth sports and other structured programming (2). In addition, the home environment (e.g., availability of SDs at home, parental modeling of SD consumption) is a well-established contributor to excess SD consumption among children (12–14), and may be especially problematic in light of increased time spent at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Herein, we report findings of a qualitative study designed to examine effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's SD consumption and related dietary behaviors.

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with 19 children and their parent/guardian (hereafter parent). The children who participated were enrolled in a larger, entirely virtual, intervention study (“Stop the Pop”) designed to investigate children's physical and emotional feelings during three days of SD cessation, findings of which will be published separately. Children 8–14 years old and their parent were recruited from across the continental U.S. to participate in “Stop the Pop” using social media, community organization listservs, and parent-targeted study advertisements created by a professional recruitment agency. Interested parents completed a brief survey (administered via Qualtrics™) to determine study eligibility. Inclusion criteria were parent report that their child: (1) was between the ages of 8 and 14 years old, and (2) consumed ≥12 ounces of SDs (including regular soda, fruit drinks, fruit juice, sports drinks, and sweet tea) per day. Recruitment for “Stop the Pop” took place from November 2020 to June 2021, and the subset of 19 parent-child dyads who participated in the qualitative interviews was recruited between March 2021 and June 2021.

After providing informed consent (parent) and assent (child), and after completing the 3-day “Stop the Pop” protocol, children and their parent were invited to participate in an in-depth qualitative interview, conducted virtually via Zoom™. Interviews were conducted by a trained interviewer (ACS) using a semi-structured guide (Supplementary Material), which included questions about how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the child's SD intake and eating behaviors, and if parental oversight of the child's SD intake had changed during the pandemic. Given that conceptualizing and articulating changes in dietary behavior during the pandemic may be cognitively challenging for children, the child and parent were interviewed together. Questions about changes in SD intake and overall diet during the pandemic were first directed to the child and then asked of the parent, whereas questions about changes in parental oversight of the child's SD intake were directed only toward parents. Data collection continued until saturation was reached, at which point, interviews had been conducted with 19 dyads. All interviews were recorded using Zoom™ and transcribed verbatim. Each dyad received a $25 Amazon gift card at the end of the interview as compensation for study participation.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the child participants. Two coders (ACS and JHK) independently coded a subset (n = 3) of the transcripts using Microsoft Word and developed a shared codebook. Both coders then independently coded all transcripts in accordance with the shared codebook, using the NVivo Pro Software Package (version 12; QSR International Inc.; Burlington, MA, USA), and added new codes as they emerged. Once the codebook was finalized, transcripts were reviewed independently by both coders, and any discrepancies in coding were discussed. After completion of coding, the two coders independently identified key overarching themes and subthemes. Themes and subthemes were then collaboratively refined by the two coders, after which, representative quotations were selected.

Demographic characteristics of the 19 children who participated in qualitative interviews are shown in Table 1. Given that the study was designed to investigate changes in the children's SD intake and dietary behaviors during the pandemic, no demographic data were collected from parents. The sample of children was 57% female, and 63% of participants self-identified as non-Hispanic white. Forty-two percent of the participants indicated eligibility for free/reduced price lunch, and most of the children (79%) reported attending school virtually at the time of the interview.

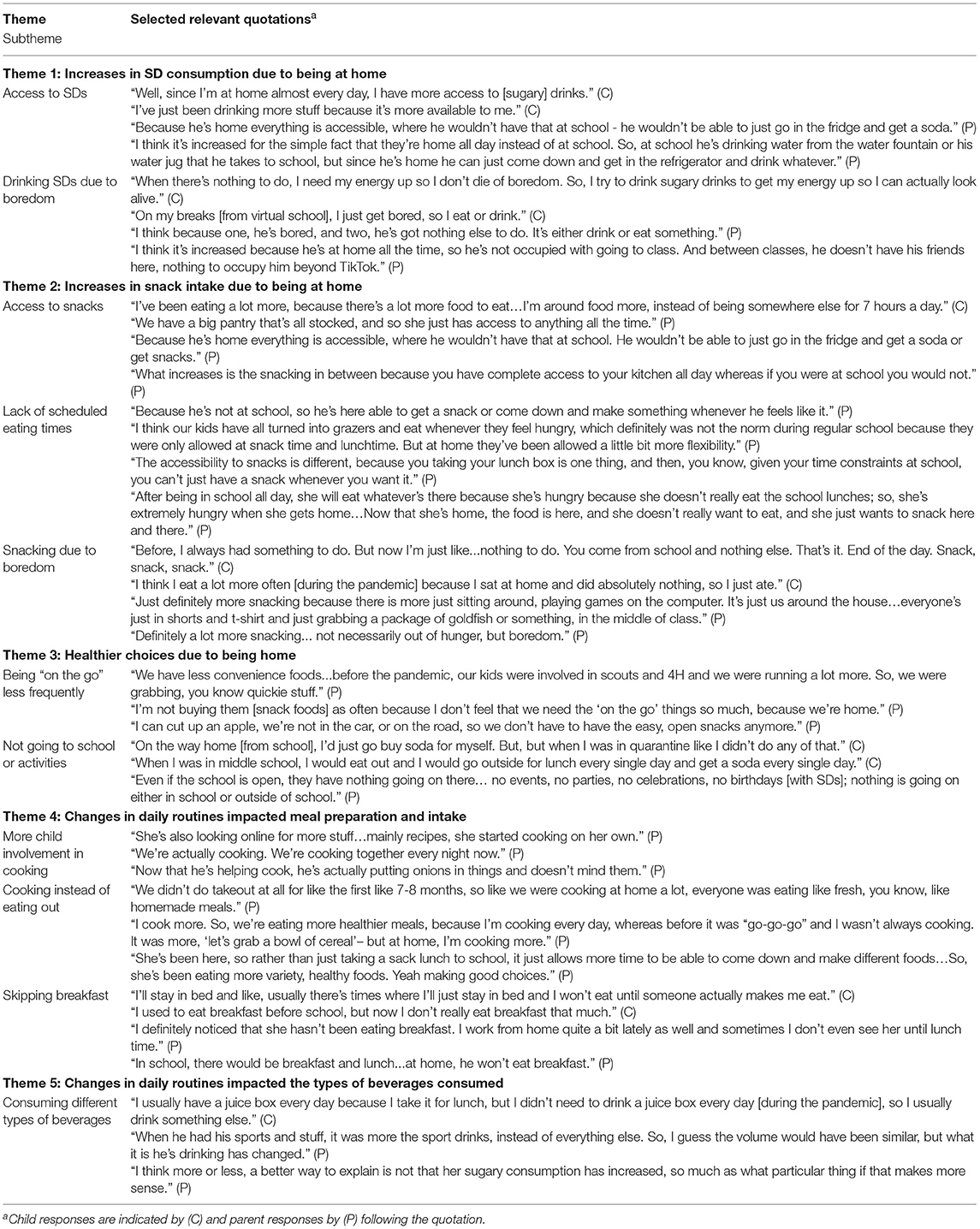

Two overarching themes emerged from the qualitative interviews. A key theme described by both children and parents was that changes in children's daily routines during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their SD, snack, and meal intake (Table 2). The second overarching theme, as explained by parents, was that the pandemic altered parents' oversight of children's SD and snack consumption (Table 3). In addition, a minor theme identified was that changes in grocery shopping behaviors during the pandemic (e.g., stockpiling shelf stable foods due to grocery shortages, purchasing more SDs and snacks due to the whole family being at home) further promoted children's SD and snack intake.

Table 2. Changes in children's daily routines during the pandemic impacted their sugary drink, snack, and meal intake.

As shown in Table 2, five key themes related to how changes in children's daily routines during the pandemic impacted their SD and snack intake were identified. Most notably, increased time spent at home, rather than in school, promoted excess consumption of SDs and snacks among children, according to both children and their parents. Increased SD and snack intake at home was commonly attributed to having unrestricted access to SDs and snacks, the child experiencing boredom, and a lack of scheduled or structured eating times. Skipping breakfast when attending school virtually was also commonly reported by children and corroborated by parents. However, parents also explained that changes in the child's daily routine during the pandemic led to favorable dietary changes, including making healthier choices as a result of not being “on the go” and cooking more meals at home, as opposed to eating out. Some children and parents also described a shift in the types, rather than the volume, of SDs the child consumed as a result of the pandemic; for instance, consuming fewer juice boxes and sports drinks, due to not needing to bring a lunch to school and having fewer sports and extracurricular activities.

As shown in Table 3, three key themes were identified pertaining to changes in parental oversight of the child's SD intake during the pandemic. Parents described removing prior restrictions on SDs, and in some cases, providing their children with SDs as a means of helping them cope with disturbances to daily life caused by the pandemic. For example, parents reported providing their child with SDs as a treat to make the child happy, and being more lenient about allowing their child to have SDs due to feeling bad for their child during the pandemic. Parents also described allowing their child more autonomy in making their own beverage choices during the pandemic. For instance, some parents explained that prior expectations that the child ask before helping themselves to SDs were no longer applicable. While these changes in parental oversight of their child's SD intake were commonly described as facilitators of increased SD consumption during the pandemic, some parents reported that being home together made them more aware of their children's SD consumption and/or made it easier for them to restrict their children's SD intake during the pandemic.

Our findings demonstrate that spending more time at home and out of school during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in perceived increases in children's SD and snack intake. These findings are consistent with several recent studies reporting unfavorable effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on dietary intake among adults (6, 9), as well as recent reports of unhealthful dietary changes among children in other countries, including Italy (15) and China (16). Increases in SD intake and snacking during the pandemic are also supported by a large body of evidence demonstrating that unhealthy weight gain among children occurs disproportionately when out of school (i.e., during the summer months), compared with during the school year (17, 18).

Greater access to SDs and snacks while at home was described by both parents and children as the predominant contributor to reported increases in children's SD and snack consumption during the pandemic. This is not surprising, as the contribution of physical aspects (e.g., availability) and social aspects (e.g., parental modeling, family meal practices) of the home environment to children's dietary intake is well-established (12, 14). Availability of SDs in the home is positively associated with SD intake among youth (19, 20), and similar findings have been reported with regard to intake of energy-dense snacks (21). A recent cross-sectional study in the U.S. indicated that one-third of parents increased the amount of high-calorie snack foods, desserts, and sweets available in the home during the pandemic, while nearly half (47%) reported increases in the availability of non-perishable processed foods (22). These shifts in the home food environment during the COVID-19 pandemic may have further exacerbated increases in children's SD and snack intake behaviors. In addition, parent modeling of SD intake is another well-described contributor to children's SD intake (23). Given that SD intake also increased among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (6), amplified parent modeling of SD consumption may have further contributed to the reported increases in children's SD intake.

Children and parents in our study also commonly described the lack of scheduled meal and snack times, and cancellation of extracurricular activities, as reasons for reported increases in their children's SD and snack intake. This finding is consistent with the “structured days hypothesis (SDH)” (10), which has been proposed to explain accelerated weight gain among children during the summer months. The SDH posits that compared with the school year, during which children follow a consistent, structured, and regimented schedule with adult supervision, the summer months typically consist of less structure and more child autonomy (10). This lack of structure provides children with more opportunities to eat (as opposed to scheduled snack and mealtimes in school) and may increase the likelihood that children make poor dietary choices (10).

Parents also described loosening restrictions on their child's dietary intake during the pandemic, which has also been reported among parents of younger children (24), and providing SDs and treats to help their children cope with disruptions to daily life. These behaviors are concerning because indulgent parenting (25), where children have freedom to eat and drink whatever they wish, and emotional eating (26), where intake of foods high in sugar and/or fat to reduce the intensity of negative emotions, are both associated with excess weight gain among children (25, 26). Marked increases in depression and anxiety among children during the COVID-19 pandemic (27) may also have contributed to reported increases in SD and snack intake, given that psychological distress is associated with overeating among youth (28).

Despite the nearly unanimously reported increases in children's SD intake and snacking, parents reported some favorable impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's diets, specifically with regard to cooking at home and eating healthier meals. Increases in cooking during the pandemic were reported in a recent scoping review (5), which also demonstrated that the pandemic had both favorable and unfavorable effects on dietary intake. Parents in our study explained that having more time and having fewer other commitments (i.e., not being on the go) were key reasons for cooking more frequently during the pandemic, consistent with prior work describing a perceived lack of time as a barrier to cooking healthy meals at home (29, 30). As has been reported in other recent publications (31, 32), parents also explained that their child was more involved in cooking meals during the pandemic. Given that cooking at home is associated with healthier dietary patterns (33), the shift toward more cooking during the pandemic may lay the groundwork for sustained improvements in meal healthfulness beyond the pandemic. Greater child involvement in cooking also holds promise, as learning cooking skills at an early age is positively associated with higher diet quality (34). However, it is unclear whether these benefits will persist, given that by mid-2021, national food sales outside the home began to exceed food at home for the first time since the pandemic began (35).

While our findings offer novel insights into impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's SD, snack, and meal consumption, the study was subject to several limitations. First, the children's responses may have been influenced by interviewing the parent and child together, leading to possible contamination of the data collected. In addition, the small sample size precluded comparing differences in pandemic-related dietary changes based on participants' race, ethnicity, or household income. This is an important limitation because youth from low-income and/or minority backgrounds are most susceptible to weight gain when out of school (36); thus, increases in SD and snack intake reported during the pandemic may worsen already marked health disparities. Another limitation was the enrollment of children who reported habitual daily consumption of SDs (per inclusion criteria for “Stop the Pop”); therefore, the extent to which the pandemic may have impacted SD intake among less frequent SD consumers could not be assessed. The parents' work environment (remote vs. in-person) also may have changed as a result of the pandemic and influenced children's SD intake and related dietary behaviors; however, data on the parent's work environment were not collected. It is also important to note that participants in the present qualitative study comprised a subset of individuals participating in a larger intervention study of short-term SD cessation. It is therefore possible that these individuals may have already had a high awareness or concern about SD intake, and thus, their description of changes in SD intake behaviors during the pandemic may not reflect those of the general population.

Taken together, our findings call attention to concerning increases in SD and snack intake among children during the COVID-19 pandemic, the effects of which may be partially offset by increases in cooking and consumption of healthier meals. Surveillance of children's diets throughout and following the pandemic is needed, as the extent to which the perceived increases in SD and snack consumption will persist longer-term is presently unclear. While these dietary changes were reported in the unique context of the COVID-19 pandemic, our findings may apply more broadly to other prolonged periods of unstructured, out-of-school time (i.e., the summer recess). Intervention strategies to improve the home food environment, such as reducing the availability of SDs and energy-dense snacks are needed, along with efforts to educate parents about optimal food parenting practices and equip children with more adaptive, non-food related coping skills.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board at the George Washington University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

AS, JK, AV, and JS designed the research. AS and JK performed the analyses. AS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in editing the manuscript and approved the final version.

This project was supported by a KL2 Career Development Award (PI: AS), under Parent Award numbers UL1TR001876 and KL2TR001877 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCATS.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to thank Anjali Sankar, Natasha Kumar, and Simran Sadhwani for their assistance with transcription of the interviews.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.860259/full#supplementary-material

1. Woolford SJ, Sidell M, Li X, Else V, Young DR, Resnicow K, et al. Changes in body mass index among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. (2021) 326:1434–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15036

2. Rundle AG, Park Y, Herbstman JB, Kinsey EW, Wang YC. COVID-19-related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity. (2020) 28:1008–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.22813

3. Lachat C, Nago E, Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Van Camp J, Kolsteren P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev. (2012) 13:329–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00953.x

4. Wolfson JA, Leung CW, Richardson CR. More frequent cooking at home is associated with higher Healthy Eating Index-2015 score. Public Health Nutr. (2020) 23:2384–94. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019003549

5. Bennett G, Young E, Butler I, Coe S. The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak on dietary habits in various population groups: a scoping review. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:626432. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.626432

6. Park S, Yaroch A, Blanck HM. Changes in consumption of foods and beverages with added sugars during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults. Curr Dev Nutr. (2021) 5:242. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzab029_043

7. Malik VS, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health: an update of the evidence. Nutrients. (2019) 11:1840. doi: 10.3390/nu11081840

8. Powell ES, Smith-Taillie LP, Popkin BM. Added sugars intake across the distribution of US children and adult consumers: 1977-2012. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2016) 116:1543–50 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.06.003

9. Cummings JR, Ackerman JM, Wolfson JA, Gearhardt AN. COVID-19 stress and eating and drinking behaviors in the United States during the early stages of the pandemic. Appetite. (2021) 162:105163. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105163

10. Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, Pate RR, Turner-McGrievy GM, Kaczynski AT, et al. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: the structured days hypothesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2017) 14:100. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0555-2

11. Tanskey LA, Goldberg J, Chui K, Must A, Sacheck J. The state of the summer: a review of child summer weight gain and efforts to prevent it. Curr Obes Rep. (2018) 7:112–21. doi: 10.1007/s13679-018-0305-z

12. Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity. (2007) 15:719–30. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.553

13. Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Sharma AJ, Uyeda K, Sticklor LA, Alijewicz KE, et al. Parental and home environmental facilitators of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among overweight and obese Latino youth. Acad Pediatr. (2013) 13:348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.02.009

14. Couch SC, Glanz K, Zhou C, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Home food environment in relation to children's diet quality and weight status. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2014) 114:1569–79 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.05.015

15. Pietrobelli A, Pecoraro L, Ferruzzi A, Heo M, Faith M, Zoller T, et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in verona, italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity. (2020) 28:1382–5. doi: 10.1002/oby.22861

16. Jia P, Liu L, Xie X, Yuan C, Chen H, Guo B, et al. Changes in dietary patterns among youths in China during COVID-19 epidemic: the COVID-19 impact on lifestyle change survey (COINLICS). Appetite. (2021) 158:105015. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105015

17. von Hippel PT, Workman J. From kindergarten through second grade, U.S. children's obesity prevalence grows only during summer vacations. Obesity. (2016) 24:2296–300. doi: 10.1002/oby.21613

18. Franckle R, Adler R, Davison K. Accelerated weight gain among children during summer versus school year and related racial/ethnic disparities: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. (2014) 11:E101. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130355

19. Pearson N, Griffiths P, Biddle SJH, Johnston JP, Haycraft E. Individual, behavioural and home environmental factors associated with eating behaviours in young adolescents. Appetite. (2017) 112:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.001

20. Haughton CF, Waring ME, Wang ML, Rosal MC, Pbert L, Lemon SC. Home matters: adolescents drink more sugar-sweetened beverages when available at home. J Pediatr. (2018) 202:121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.06.046

21. Larson N, Miller JM, Eisenberg ME, Watts AW, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multicontextual correlates of energy-dense, nutrient-poor snack food consumption by adolescents. Appetite. (2017) 112:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.008

22. Adams EL, Caccavale LJ, Smith D, Bean MK. Food insecurity, the home food environment, and parent feeding practices in the era of COVID-19. Obesity. (2020) 28:2056–63. doi: 10.1002/oby.22996

23. Sylvetsky AC, Visek AJ, Turvey C, Halberg S, Weisenberg JR, Lora K, et al. Parental concerns about child and adolescent caffeinated sugar-sweetened beverage intake and perceived barriers to reducing consumption. Nutrients. (2020) 12:885. doi: 10.3390/nu12040885

24. Trofholz A, Hersch D, Norderud K, Berge JM, Loth K. Changes to the home food environment and parent feeding practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative exploration. Appetite. (2021) 169:105806. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105806

25. Jalo E, Konttinen H, Vepsalainen H, Chaput JP, Hu G, Maher C, et al. Emotional eating, health behaviours, and obesity in children: a 12-country cross-sectional study. Nutrients. (2019) 11:351. doi: 10.3390/nu11020351

26. Shloim N, Edelson LR, Martin N, Hetherington MM. Parenting styles, feeding styles, feeding practices, and weight status in 4-12 year-old children: a systematic review of the literature. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:1849. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01849

27. Meade J. Mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: a review of the current research. Pediatr Clin North Am. (2021) 68:945–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2021.05.003

28. Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Overeating among adolescents: prevalence and associations with weight-related characteristics and psychological health. Pediatrics. (2003) 111:67–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.67

29. Velez-Toral M, Rodriguez-Reinado C, Ramallo-Espinosa A, Andres-Villas M. “It's important but, on what level?”: Healthy cooking meanings and barriers to healthy eating among university students. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2309. doi: 10.3390/nu12082309

30. Robson SM, Crosby LE, Stark LJ. Eating dinner away from home: perspectives of middle-to high-income parents. Appetite. (2016) 96:147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.019

31. Benson T, Murphy B, McCloat A, Mooney E, Dean M, Lavelle F. From the pandemic to the pan: the impact of COVID-19 on parental inclusion of children in cooking activities: a cross-continental survey. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 25:36–42. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021001932

32. Hammons AJ, Robart R. Family food environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Children. (2021) 8:354. doi: 10.3390/children8050354

33. Wolfson JA, Bleich SN. Is cooking at home associated with better diet quality or weight-loss intention? Public Health Nutr. (2015) 18:1397–406. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014001943

34. Lavelle F, Spence M, Hollywood L, McGowan L, Surgenor D, McCloat A, et al. Learning cooking skills at different ages: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2016) 13:119. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0446-y

35. Economic Research Service U,. S. Department of Agriculture. COVID-19 Economic Implications for Agriculture, Food, Rural America: Food Consumers. (2021). Available online at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/covid-19/food-and-consumers/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

Keywords: sugar-sweetened beverages, coronavirus, diet, youth, obesity, soda, nutrition

Citation: Sylvetsky AC, Kaidbey JH, Ferguson K, Visek AJ and Sacheck J (2022) Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children's Sugary Drink Consumption: A Qualitative Study. Front. Nutr. 9:860259. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.860259

Received: 22 January 2022; Accepted: 11 February 2022;

Published: 16 March 2022.

Edited by:

Igor Pravst, Institute of Nutrition, SloveniaReviewed by:

Natasa Fidler Mis, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, SloveniaCopyright © 2022 Sylvetsky, Kaidbey, Ferguson, Visek and Sacheck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Allison C. Sylvetsky, YXN5bHZldHNAZ3d1LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.