- 1Oncology and Hematology Department, Israelita Albert Einstein Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil

- 2Bioethical Committee, Israelita Albert Einstein Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil

- 3Clinical Nutrition Division, São Paulo University, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil

Introduction: Bioethics and nutrition are essential issues in end of life, advanced dementia, life-sustaining therapies, permanent vegetative status, and unacceptably minimal quality of life. Even though artificially administered nutrition (AAN), for this type of health condition, does not improve quality of life and extension of life, and there is evidence of complications (pulmonary and gastrointestinal), it has been used frequently. It had been easier considering cardiopulmonary resuscitation as an ineffective treatment than AAN for a healthy team and/or family. For this reason, many times, this issue has been forgotten.

Objectives: This study aimed to discuss bioethical principles and AAN in the involved patients.

Discussion: The AAN has been an essential source of ethical concern and controversy. There is a conceptual doubt about AAN be or not be a medical treatment. It would be a form of nourishment, which constitutes primary care. These principles should be used to guide the decision-making of healthcare professionals in collaboration with patients and their surrogates.

Conclusions: This difficult decision about whether or not to prescribe AAN in patients with a poor prognosis and without benefits should be based on discussions with the bioethics committee, encouraging the use of advanced directives, education, and support for the patient, family, and health team, in addition to the establishment of effective protocols on the subject. All of this would benefit the most important person in this process, the patient.

Introduction

Despite the lack of studies about bioethics and artificial nutrition, this issue should be discussed further since we have never had such a high life expectancy associated with a search for quality of life in human history (1–3). However, the proportion of chronic and end-of-life patients living with severe conditions without the quality of life and using beneficial treatments, including artificially administered nutrition (AAN), is increasing (4–6).

Artificially administered nutrition (AAN) is oral nutritional supplements, enteral nutrition, including nasogastric and nasogastrojejunal tubes or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or jejunostomy, or parenteral nutrition involves peripheral intravenous access or central venous access (7).

In end-of-life, advanced dementia, life-sustaining therapies, permanent vegetative status, and unacceptably minimal quality of life, AAN has not improved quality of life and extension of life and has been associated with pulmonary and gastrointestinal complications (8, 9). Nevertheless, family and some health professionals consider it a life-prolonging treatment, and discontinuing tube feeding or parenteral nutrition seems as direct a cause of death as stopping a ventilator (8, 9). Although these patients do not experience thirst or hunger and, therefore, there is no suffering, this therapeutic decision can cause 11% of discordance by treatment decisions in Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment forms (9, 10).

Religious beliefs, cultural values, and emotional factors explain the difficulty in not prescribing AAN, even in cases where it is proven not to benefit health professionals and/or family members. Often, doctors convince families about the need for this prescription because they think it is the best standard of care for patients (8, 11–13). For relatives and the health, the team has been more accessible considering cardiopulmonary resuscitation as an ineffective treatment than AAN, that many times this issue has been forgotten (8).

Due to all these factors involved in this challenging nutritional subject, discussing bioethics and nutrition in end-of-life, advanced dementia, life-sustaining therapies, permanent vegetative status, and unacceptably minimal quality of life have been important issues (11, 12, 14–16).

Despite all the scientific evidence, there is difficulty deciding not to nourish patients with adverse conditions by all those involved artificially. Therefore, our objective is to discuss bioethical principles and AAN.

Understanding the Role of Food in Our Lives

Nutrition is involved with the evolution of the human being. The discovery of fire provided a high-quality diet, with cooked food, which increased brain size, crucial for our intellectual development (17). The changing to raw food from cooked food allowed more energy for the brain (17).

Our nutrition and/or food relationship, based on a complicated behavior and physiologic mechanism, has social, environmental, culture, ethics, economics, religion, physiology, marketing, and psychological influences that interact with many other factors (18–21). Besides, nutrition, unusual in a scientific discipline, is defined by political codifications or laws and linked directly to marketing products (22).

In addition, food has many symbolic meanings, such as eating alone is different from eating during a religious ceremony, where its sociality can be identified (21). For a religious person, food consumption during religious ceremonies determines and reestablish the relationship between man and God (21).

Every social event, such as religious ceremonies, parties, friendship, family and business meetings, and social status, has been associated with food, symbolizing happiness and wealth (21).

Physicians are influenced not only for their food behavior, influenced by all things previously cited, but the medical literature is also replete with allusions of a gustatory nature, such as croissant appearance to diagnose a schwannoma; Blueberry muffin rash in congenital rubella; the kidney is bean form (23).

All these factors associated with food could explain difficulties in denying AAN for patients, even when there is a lack of benefits.

Concepts of Starvation and Suffering

In western societies, observing hunger is unacceptable, conducting inconsistent clinical practice (24). For this cultural factor, generally, difficulty in eating often causes anxiety in the patients' entourage (family and health care team), who worry that the patient will starve to death (25). However, end-of-life, severe dementia, and permanent vegetative status patients have not experienced hunger (>60%). Therefore they do not suffer without a lot of food (25, 26).

The patients' entourage must be informed that food often causes more discomfort than pleasure in these patients (25). It is essential delicate care and continuing communication for avoiding unnecessary AAN (25). There is no suffering for these patients when AAN is not prescribed.

The cause of death in starvation is dehydration; without food, healthy people last until two months (27, 28). Therefore, when AAN is not prescribed, it is not a death cause or suffering in these patients. It should be explained to the family, patient, and health team.

The Artificial Administrated Nutrition (AAN) in End-of-Life, Advanced Dementia, and Permanent Vegetative Status

More and more advances in technology and the ability to provide AAN; for this reason, more research into the legal, ethical, clinical, religious, cultural, personal, and physical aspects have been conducted (29).

Artificially administered nutrition (AAN) could be administrated in neurological and in cancer patients, potentially increasing survival and quality of life in selected patients in palliative care (7). However, there is a consensus about not providing AAN for the terminally ill when the prognosis is less than six months of life, metastatic cancer, advanced dementia, permanent vegetative status, and unacceptably minimal quality of life (7, 11, 12, 30).

End-of-life care is attached to complexity and emotion, and it makes the process difficult for the individual as well as family, friends, health care providers, and society (29). For this reason, although there are no benefits in using AAN in end-of-life, permanent and persistent vegetative status, it has usually been prescribed (8, 31). According to family and clinicians, a feeding tube seems less comfortable with fewer side effects. Therefore PN, apparently less aggressive, has been more prescribed for these patients, even though it has more side effects (31).

Persistent vegetative status is considered a state of extreme unresponsiveness, lasting for more than 1 month, with no awareness or higher cerebral function. And after ~1 year of this condition, it is defined as a permanent vegetative state (29). Many clinical cases about AAN prescribed in permanent vegetative conditions were discussed by courts and legislative bodies, such as the Therese Schiavo case, which was debated in many countries for many years (7, 15, 16, 24, 32).

Artificially administered nutrition (AAN) should not be prescribed due to a lack of evidence of benefits in severe dementia either. However, AAN is very common in patients with this condition using percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or jejunostomy or nasogastric and nasogastrojejunal tubes (7, 11).

In addition, ethically and legally, withholding and withdrawal of treatments are identical, but the decisions to withdraw AAN, previously prescribed, are admittedly harder emotionally than the decisions not to initiate this therapy (33). This is another aspect that must carefully be evaluated to avoid further suffering for the family and patient.

Besides, factors below for family, physicians, and administrators encouraging the use of AAN in Clinical Practice in the terminal ill (8, 31):

• Family: to deny terminal prognosis; belief in to be cruel not administer AN; must demand interventions to avoid guilt

• Physicians: lack of familiarity with palliative care techniques; length of time required to educate families on facts of AAN; reimbursement for insertion of enteral and parenteral nutrition; the desire to avoid controversial discussions; fears of litigation

• Administrators: a reimbursement for insertion of enteral and parenteral nutrition; fear of regulatory sanctions if AAN is not administered (nursing homes); extra time and staff needed to assist with oral feedings in weakened or demented patients; fears of litigation.

Most of the time, the decision about AAN prescription has been related to incomplete clinical information, intense and often conflicting attitudes and judgments from patients, families, and health professionals; economic, social, cultural, and religious opinions; consequently, more unscientific than scientific factors influence this decision (33).

Bioethics Dilemmas in Artificial Nutrition

There was a conceptual doubt about AAN being or not being a medical treatment, and it would be a form of nourishment, which constitutes primary care. For this reason, it has been an essential source of ethical concern and controversy AAN (30). However, in 2021, the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) affirmed that AAN and hydration are medical treatments (9).

Therefore, ethical principles could guide healthcare professionals' decisions in collaboration with patients and their surrogates (33–35).

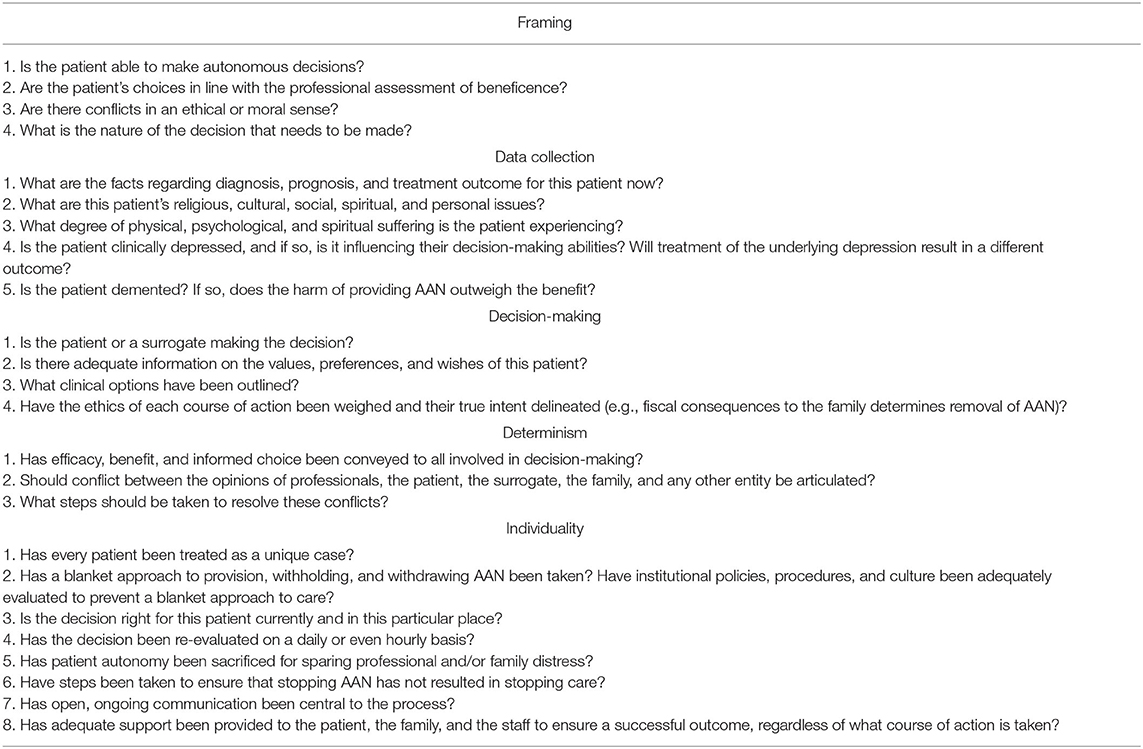

In 2010, Heuberger, RA suggested some questions for end-of-life. Still, they could be applied for dementia and permanently vegetative states, helping health professionals make the best decision for patients and families (29) (Table 1).

Table 1. Questions to ask regarding the ethics of providing AAN (29).

Bioethics Principles

Nutrition support clinician participation on interprofessional rounds, family meetings, and the bioethics committee is essential to understanding decision-making complexity in cases dealing with nutrition concerns, mainly in prescribing or not prescribing AAN (36). The bioethics is based on the “four principles approach to medical ethics” which are autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice (35, 37, 38).

Autonomy

The principle of autonomy recognizes a patient's right and capacity to decide about accepting or not accepting AAN, including medical decisions related to the initiation, withholding, or withdrawal (7, 33, 36). An example of respecting autonomy is not feeding hunger strikers mentally competent by the World Medical Association Declaration of Tokyo (7).

Every decision should be made after obtaining the appropriate information and having an adequate understanding without coercion or pressure (7). When the patient cannot exercise their autonomy, the legal representatives (authorized according to different rules depending on the countries law and practice) could decide for them about AAN (7).

For the health team, another tool used in AAN when the patient was not conscious is the Advance directives. However, despite extensive public health education and promotion, <20% of Americans have signed it (29, 33).

Beneficence and Non-Maleficence

The health care team should maximize potential benefits for their patients and do the best for them (beneficence) while at the same time minimizing potential harm for them (“primum non-nocere”) (7, 33). Non-maleficence, i.e., to not harm, is the most introductory statement of the goal of healthcare to prevent and alleviate pain and suffering and minimize adverse effects of the intervention (33).

Artificially administered nutrition (AAN) has been beneficial for several patients, prolonging and increasing the quality of life. In severe dementia, permanent vegetative state, and end of life, in addition to there being no benefits in AAN prescription, there are potential complications and burdens, so it should not be used (7, 33, 36).

Justice

The principle of justice refers to equal access to health care for all. Nutrition must be based on social responsibility for local, regional, national, global nutrition and wellbeing (7, 39). The expensive nutritional therapies should always be provided solely when indicated. However, undertreatment may never result from containing the growing costs of healthcare (7).

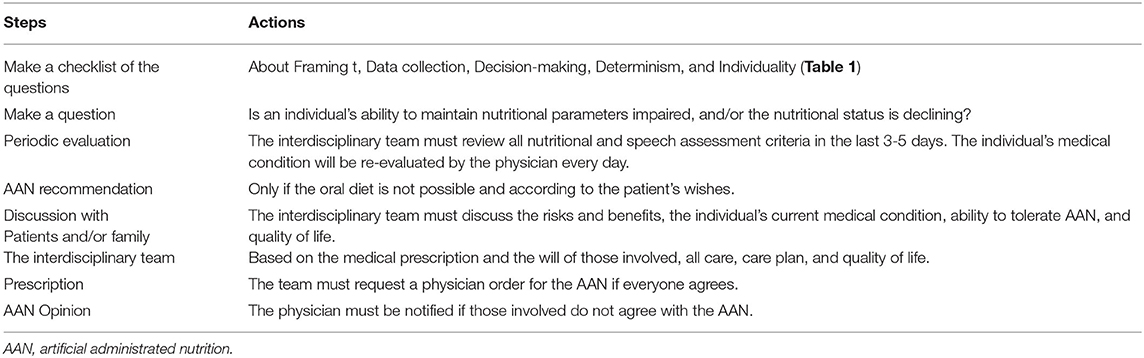

In Table 2, some steps and procedures according to the Academy/CDR Code of Ethics for the Nutrition and Dietetics Profession in Bioethics Principles are essential for professionals in the nutrition area (39).

Table 2. According to the academy/CDR code of ethics for the nutrition and dietetics profession in bioethics principles is essential for professionals in the nutrition area (39).

In addition to, Table 3, there are steps for the interdisciplinary team to prescribe or not AAN in an ethical and clinically appropriate way based on scientific evidence and nutritional and bioethical consensus (29, 35).

Table 3. Seven steps for the interdisciplinary team to prescribe or not AAN with ethics and clinically based on scientific evidence, nutritional and bioethical consensus.

Conclusions

Although there are many nutrition guidelines and scientific studies about AAN in end-of-life, severe dementia, and permanently vegetative states, their decisions are influenced by relatives and health professionals' emotional, economic, social, cultural, and religious values.

This difficult decision about whether or not to prescribe AAN in patients with a poor prognosis and without benefits should base on discussions with the bioethics committee, encouraging the use of advanced directives, education, and support for the patient, family, and health team, in addition to the establishment of effective protocols on the subject.

Therefore, more studies about this important topic are essential and the education of health professionals who work with palliative care, nutrition and end-of-life patients, and bioethics committee. All of this would benefit the most important person in this process, the patient.

Author Contributions

AP, SC, and MB equally contributed to the conception and design of the research. AP, SC, MB, and HG drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, agreed to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Andrew Steptoe ADAAS. Psychological wellbeing, health and ageing. Lancet. (2015) 385:640–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0

2. World Health Organization(WHO). Ageing and health. Available online at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs404/en. (2015).

3. Schwartz DB. Integrating patient-centered care and clinical ethics into nutrition practice. Nutr Clin Pract. (2013) 28:543–55. doi: 10.1177/0884533613500507

4. Spathis Anna, Booth S. End of life care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease : in search of a good death. Int J COPD. (2008) 3:11–29. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S698

5. Macedo E, Filho L, Pinheiro PP, Coimbra J, Cruz M, Silveira RT, et al. Bioethics inserted in oncologic palliative care : a systematic review. Int Arch Med. (2015) 8:1–15. doi: 10.3823/1702

6. Hansen-flaschen J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The last year of life. Respir Care. (2004) 49:90–7. Available online at: http://rc.rcjournal.com/content/respcare/49/1/90.full.pdf

7. Druml C, Ballmer PE, Druml W, Oehmichen F, Shenkin A, Singer P, et al. ESPEN guideline on ethical aspects of artificial nutrition and hydration. Clin Nutr [Internet]. (2016) 16:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.02.006

8. Brody H, Hermer LD, Scott LD, Grumbles LL, Kutac JE, McCammon SD. Artificial nutrition and hydration: the evolution of ethics, evidence, and policy. J Gen Intern Med. (2011) 26:1053–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1659-z

9. Schwartz DB, Barrocas A, Annetta MG, Stratton K, McGinnis C, Hardy G, et al. Ethical aspects of artificially administered nutrition and hydration: an ASPEN position paper. Nutr Clin Pract. (2021) 36:254–67. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10633

10. Hickman SE, Hammes BJ, Torke AM. The quality of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment decisions: a pilot study. J Palliat Med. (2017) 20:2. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0059

11. Volkert D, Chourdakis M, Faxen-irving G, Frühwald T, Landi F, Suominen MH, et al. ESPEN guideline ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin Nutr. (2015) 34:1052–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.004

12. Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr [Internet]. (2017) 36:11–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015

13. Arends J, Bodoky G, Bozzetti F, Fearon K, Muscaritoli M, Selga G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: non-surgical oncology. Clin Nutr. (2006) 25:245–59. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.020

14. Körner U, Bondolfi A, Bühler E, Macfie J, Meguid MM, Messing B, et al. Ethical and legal aspects of enteral nutrition. Clin Nutr. (2006) 25:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.024

15. Quill TE. Terri schiavo–a tragedy compounded. N Engl J Med. (2005) 352:1630–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058062

16. Paris JJ. Terri Schiavo and the use of artificial nutrition and fluids: insights from the catholic tradition on end-of-life care. Palliat Support Care. (2006) 4:117–20. doi: 10.1017/S1478951506060160

17. Gowlett JAJ. The discovery of fire by humans : a long and convoluted process. Philos Trans B. (2016) 371:1–11. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0164

18. Hardcastle SJ, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Chatzisarantis NLD. Food choice and nutrition: a social psychological perspective. Nutrients. (2015) 7:8712–5. doi: 10.3390/nu7105424

19. Köster EP. Diversity in the determinants of food choice: a psychological perspective. Food Qual Prefer. (2009) 20:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.11.002

20. Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E, Goldberg J, Snyder D. Why Americans eat what they do: taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J Am Dietetic Assoc. (1998) 98:1118–26. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00260-0

21. Ma G. Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese society. J Ethn Foods [Internet]. (2015) 2:195–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.11.004 doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2015.11.004

22. Rucker RB, Rucker MR. Nutrition: ethical issues and challenges. Nutr Res [Internet]. (2016) 36:1183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.10.006

23. Lakhtakia R. Twist of taste: gastronomic allusions in medicine. Med Humanit [Internet]. (2014) 14:1–3. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2014-010522

24. Miller I. Starving to death in medical care : ethics, food, emotions and dying in Britain and America, (1970s). – (1990s). Biosocieties. (2017) 12:89–108. doi: 10.1057/s41292-016-0034-z

25. Prevost V, Grach MC. Nutritional support and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing palliative care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2012) 21:581–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01363.x

26. Muscaritoli M, Anker SD, Argilés J, Aversa Z, Bauer JM, Biolo G, et al. Consensus definition of sarcopenia, cachexia and pre-cachexia: Joint document elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG) “cachexia-anorexia in chronic wasting diseases” and “nutrition in geriatrics.” Clin Nutr. (2010) 29:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.004

28. Gétaz L, Rieder JP, Nyffenegger L, Eytan A, Gaspoz JM, Wolff H. Hunger strike among detainees: guidance for good medical practice. Swiss Med Wkly. (2012) 142:1–5. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13675

29. Heuberger RA. Artificial nutrition and hydration at the end of life. J Nutr Elder [Internet]. (2010) 29:347–85. doi: 10.1080/01639366.2010.521020

30. Del Río N. The influence of latino ethnocultural factors on decision making at the end of life: withholding and withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. (2010) 6:125–49. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2010.529009

31. Orrevall Y, Tishelman C, Permert J, Lundström S. A national observational study of the prevalence and use of enteral tube feeding, parenteral nutrition and intravenous glucose in cancer patients enrolled in specialized palliative care. Nutrients. (2013) 5:267–82. doi: 10.3390/nu5010267

32. Monturo C. The artificial nutrition debate: still an issue. After All These Years. Nutr Clin Pract. (2007) 206–13. doi: 10.1177/0884533609332089

33. Geppert CMA, Andrews MR, Druyan ME. Ethical issues in artificial nutrition and hydration: a review. J Parenter Enter Nutr. (2009) 34:79–88. doi: 10.1177/0148607109347209

34. Schwartz DB, Armanios N, Monturo C, Frankel EH, Wesley JR, Patel M, et al. Clinical ethics and nutrition support practice: implications for practice change and curriculum development. J Acad Nutr Diet [Internet]. (2016) 116:1738–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.01.009

35. Schwartz DB, Posthauer ME, O'Sullivan Maillet J. Advancing nutrition and dietetics practice: dealing with ethical issues of nutrition and hydration. J Acad Nutr Diet [Internet]. (2021) 121:823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.07.028

36. Schwartz DB, Pavic-Zabinski K, Tull K. Role of the nutrition support clinician on a hospital bioethics committee. Nutr Clin Pract. (2019) 34:869–80. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10378

37. Beauchamp, Tom L; Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. (2000) 20:1–12.

38. Beauchamp TL. Methods and principles in biomedical ethics. JMedEthics [Internet]. (2003) 29:269–74. doi: 10.1136/jme.29.5.269

Keywords: bioethics, nutrition, artificial nutrition, end-of-life, dementia

Citation: Pereira AZ, da Cunha SFdC, Grunspun H and Bueno MAS (2022) The Difficult Decision Not to Prescribe Artificial Nutrition by Health Professionals and Family: Bioethical Aspects. Front. Nutr. 9:781540. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.781540

Received: 22 September 2021; Accepted: 31 January 2022;

Published: 03 March 2022.

Edited by:

Lidia Santarpia, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyReviewed by:

Irzada Taljic, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and HerzegovinaVanessa Fuchs-Tarlovsky, General Hospital of Mexico, Mexico

Copyright © 2022 Pereira, da Cunha, Grunspun and Bueno. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Z. Pereira, YW5kcmVhcF9wZXJlaXJhQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Andrea Z. Pereira

Andrea Z. Pereira Selma Freire de Carvalho da Cunha3

Selma Freire de Carvalho da Cunha3