- 1School of Public Health, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Department of Community Health, Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Guangzhou, China

- 4Department of Chronic Disease, Guangzhou Yuexiu District Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Guangzhou, China

- 5Department of Geriatrics, Institute of Geriatrics, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Science, Guangzhou, China

- 6Department of Cardiology, Guangdong Cardiovascular Institute, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Science, Guangzhou, China

- 7School of Public Health and Emergency Management, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China

Background: Adherence to a healthy lifestyle could reduce the risk of hypertension and diabetes in general populations; however, whether the associations exist in subjects with dyslipidemia remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the integrated effect of lifestyle factors on the risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia.

Methods: In total of 9,339 subjects with dyslipidemia were recruited from the baseline survey of the Guangzhou Heart Study. A questionnaire survey and medical examination were performed. The healthy lifestyle score (HLS) was derived from five factors: smoking, alcohol drinking, diet, body mass index, and leisure-time physical activity. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated by using the logistic regression model and the multinomial logistic regression after adjusting for confounders.

Results: The prevalence of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity was 47.65, 16.02, and 10.10%, respectively. Subjects with a higher HLS were associated with a lower risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity. In comparison to the subjects with 0–2 HLS, the adjusted ORs for subjects with five HLS was 0.48 (95% CI: 0.40–0.57) and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.54–0.84) for hypertension and T2DM. Compared with subjects with 0-2 HLS and neither hypertension nor T2DM, those with five HLS had a lower risk of suffering from only one disease (OR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.40–0.57) and their comorbidity (OR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.26–0.47).

Conclusions: The results suggest that the more kinds of healthy lifestyle, the lower the risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia. Preventive strategies incorporating lifestyle factors may provide a more feasible approach for the prevention of main chronic diseases.

Introduction

Previous studies have shown that dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are three key risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, and they often occur alone or synergistically as main chronic non-communicable diseases (1–3). They have become a major public health challenge, especially in developing countries (4, 5). According to the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study, high systolic blood pressure and high fasting plasma glucose have become the leading risks of death, and the global burden of dyslipidemia has increased with socio-economic development (6). In China, the prevalence of dyslipidemia has constantly increased in recent years (7, 8). Previous studies have found that compared with those with normal blood lipid levels, patients with dyslipidemia were at higher risk for developing hypertension and diabetes, and even have a higher prevalence of coexisting risk factors (3, 9, 10). Given the commonality in lifestyle factors among hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, it is of significance to identify effective strategies to prevent or delay the development of hypertension and T2DM in subjects with dyslipidemia.

Based on published studies, efforts to reduce the risk of hypertension and T2DM, such as adherence to a healthy lifestyle, have been encouraged in the general population (11–14). For instance, previous studies conducted in different countries showed that four main healthy lifestyle factors including no smoking, no drinking, healthy physical activity, and healthy body mass index (BMI), were associated with a decreased risk of hypertension (11–13). A systematic review and meta-analysis including 14 studies and approximately one million subjects indicated that adherence to the healthiest lifestyles was associated with a 75% reduced risk of T2DM when compared with individuals with the least healthy lifestyles (14). However, in the subjects with dyslipidemia, whether adopting a healthy lifestyle will also have similar beneficial effects on hypertension and T2DM is still unclear.

Therefore, this present study aimed to examine the integrated effect of five major lifestyle factors, including smoking, alcohol drinking, diet, BMI, and leisure-time physical activity (LTPA), on the risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia. The results of this study will provide evidence to prevent hypertension and T2DM by adopting lifestyle adjustment strategies that are easy to implement among subjects with dyslipidemia.

Methods

Setting and subjects

This study was based on the baseline survey of the Guangzhou Heart Study (GZHS), an ongoing prospective population-based cohort study in Guangzhou, China. The baseline survey of GZHS was successfully conducted between July 2015 and August 2017 using the multistage sampling method. Detailed information about GZHS can be seen in our previous reports (15–19). Briefly, a total of 12,013 permanent residents aged 35 years or above were recruited and accomplished the GZHS baseline survey. Those who had mental or cognitive disorders, had mobility difficulties, had any history of cancer, were pregnant or lactating women, and were non-Guangzhou permanent residents were excluded when recruiting subjects. In this study, among 12,013 subjects, we excluded subjects with missing data on blood pressure or diabetes-related information (n = 5) and subjects without dyslipidemia (n = 2,669). Ultimately, a total of 9,339 subjects with dyslipidemia were included for further analysis. The flow chart of selecting subjects was shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Biomedical Research, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University. The study was performed in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and all subjects provided informed consent.

Ascertainment of hypertension, T2DM, and dyslipidemia

All subjects were invited to undergo a free medical examination. Subjects were instructed to rest for 10 min in a quiet room before blood pressure measurement. Systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were measured three times by trained medical workers, and then the mean of the three measurements was calculated. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg or having self-reported physician-diagnosed hypertension (19). A fasting blood sample from each subject was collected, and serum concentrations of fasting blood glucose, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and cholesterol were detected. Subjects whose fasting blood glucose was ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or who had self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes (excluding gestational diabetes mellitus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, or other types of diabetes) were defined as having T2DM (20). Subjects who self-reported physician-diagnosed dyslipidemia or with serum cholesterol of ≥5.2 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) of ≥ 3.4 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) of < 1.0 mmol/L or triglyceride of ≥ 1.7 mmol/L was considered as having dyslipidemia (21). Uniform inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above were used for the three disease populations.

Assessment of lifestyle factors

Structured questionnaires conducted with a face-to-face approach were used to collect information on social demographics and lifestyle factors including cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking. For smoking, subjects who have never smoked or smoked < 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were classified as non-smokers, and those who have currently smoked or smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime were classified as smokers. For alcohol drinking, subjects were asked to report their current drinking status: “frequent drinking”, “occasional drinking” and “never drinking or alcohol cessation”. Subjects who reported “frequent drinking” were considered as frequent drinkers, others as moderate drinkers.

Dietary consumption was collected using a 22-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (17). The intake frequency of each food item (< once per month, 1–3 times per month, 1–3 times per week, 4–6 times per week, and ≥once per day) over the previous 12 months was collected from each subject. A total of 12 major food items in FFQ (cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruit, dairy, nuts, fish, poultry, red meat, fried foods, high-salt foods, and sugary beverages) were used to create a diet quality score based on the Chinese Dietary Guidelines (22). For fruit and vegetables, one point was assigned if they were consumed more than three times per week; for whole grains, legumes, nuts, dairy, poultry, and fish, one point was assigned separately if they were consumed at least once per week; for red meat, one point was assigned if it was consumed less than once per week; for high-salt foods, fried foods, and sugary beverages, one point was assigned separately if they were not consumed or consumed less than once per month. A point of 0 was assigned to each food item if the intake frequency did not meet the corresponding criteria aforementioned. Accordingly, the diet quality score of subjects ranged from 0 (lowest) to 12 (highest). A healthy diet was defined as a quality score was 7 points or more (the median value), otherwise an unhealthy diet.

The medical examination was performed on each participant; height and weight were measured using standard instruments. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2); a healthy BMI was defined as BMI in the range of 18.5 to 23.9 kg/ m2 according to the Chinese standard, otherwise an unhealthy BMI (23).

Leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) was evaluated by a modified Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (24, 25). The total volume of LTPA for each subject was calculated as the sum of volumes of eight categories of most common LTPA including Tai Chi/Qigong, housework, stroll, bicycling, brisk walking/exercises/Yangko, ball games (basketball, table tennis, badminton, etc.), swimming, long-distance running/aerobics dancing. The volume of each LTPA was assessed by multiplying the frequency of activity by its duration and then by its intensity (quantified by the value of metabolic equivalent, MET). More detailed information on the assessment of physical activity was shown in our previous report (19). According to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on physical activity, to attain substantial health benefits, adults should perform at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, or at least 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of both throughout the week (26). Accordingly, conducting activity with at least 10 MET-hours/week is suggested as the minimum level of the recommended standard (26).

Healthy lifestyle score establishment

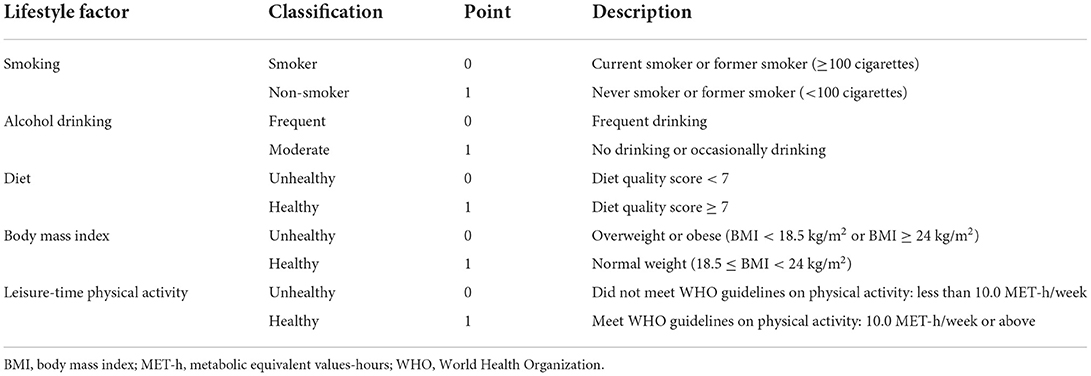

The details of the healthy lifestyle score (HLS) are shown in Table 1. The HLS was established by using five modifiable lifestyle factors including smoking, alcohol drinking, diet, BMI, and LTPA. These factors were dichotomized as healthy or unhealthy, and each factor was assigned a score of 1 and 0 for healthy and unhealthy, respectively. The score for each lifestyle factor was defined as follows: smoking (1 = non-smoker, 0 = smoker), alcohol drinking (1 = moderate drinker, 0 = frequent drinker), diet (1 = healthy diet, 0 = unhealthy diet), BMI (1 = healthy BMI, 0 = unhealthy BMI), LTPA (1 = reach the minimum level of the WHO recommended standard, 0 = not reach the minimum level of the WHO recommended standard). The total score for HLS was calculated as the sum of the scores of five selected factors. Consequently, The HLS ranged from zero (least healthy) to five (healthiest) points.

Potential confounding factors

The structured questionnaires aforesaid were used to collect information on social demographics by using face-to-face interviews. The social demographics included age (years), sex (male, female), education (< high school, ≥high school), marital status (married, others), and retirement status (yes, no).

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed using mean and standard deviation (SD), and the continuous variables with non-normal distribution were displayed using median and quartile range (IQR). The normality was examined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The distribution of categorical variables was represented as frequency and percentage. The distribution difference of baseline social demographics, lifestyle factors, and other covariables among different groups was evaluated by chi-square test for a categorical variable and t-test, one-way analysis of variance, Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum-test for a continuous variable. The associations between HLS and its components were examined using the Spearman correlation coefficient (rs). Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were measured by logistic regression models to demonstrate the individual and overall impact of lifestyle factors on the risk of hypertension and T2DM. Multinomial logistic regression was used to estimate ORs and CIs of suffering from either or both hypertension and T2DM compared with those of non-hypertension and non-T2DM. Stratified analysis was conducted by sex and retirement status. The multiplicative interaction of HLS with sex and retirement status was estimated respectively using the likelihood ratio test, with a comparison of the likelihood scores of the two models with and without the interaction terms.

A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the robustness of the results. We used every dyslipidemia indicator to define the dyslipidemia and repeated the analysis. Considering that different lifestyle components may have unequal effects on diseases, we created a weighted lifestyle score weighted by the multivariable-adjusted risk estimates (β coefficients) on hypertension and T2DM. The equation was: Weighted score = (β×1 factor1 + β2 × factor3 + β3 × factor4 + β4 × factor4 + β5 × factor 5) × (5/sum of the β coefficients) (27). We further grouped all subjects into three categories based on the tertile cut-off points of weighted score. As the volume of LTPA of most subjects met the WHO recommended standard (85.43%), we conducted an analysis by using the median in place of the WHO-recommended cut-off value of LTPA in generating HLS. To verify the effect of different BMI cut-off values on our results, we further used 25 kg/m2, suggested as the cut-off point of overweight by WHO, as the cut-off value for healthy and unhealthy BMI in generating HLS. To examine whether the HLS was appropriate for the risk assessment (28), we replaced BMI with waist circumference as a component of HLS. Repeated analyses were also performed by excluding subjects with a BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 to rule out unknown bias brought by underweight (n = 355), by excluding subjects aged 75 years or above to rule out the effects of age-related factors (n = 953), and with additional adjustment for the number of dyslipidemia indicators. All analyses were conducted with R 4.0.1 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria); the tests were two-tailed, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the total of 9,339 subjects with dyslipidemia, 4,889 subjects (52.35%) were divided into the non-hypertension group and 4,450 (47.65%) into the hypertension group; 7,843 (83.98%) subjects were classified into the non-T2DM group and 1,496 (16.02%) into the T2DM group; 4,336 (46.43%) subjects suffered neither hypertension nor T2DM and 943 (10.10%) suffered both hypertension and T2DM.

The mean age and BMI in the hypertension group and T2DM group were larger than those in the non-hypertension and non- T2DM groups respectively (Table 2). In comparison to the non-hypertension subjects, subjects with hypertension were more likely to be male and not married, to have a lower level of education, to be retirees, to smoke and drink alcohol, to have an unhealthy diet, or have an unhealthy BMI (all P < 0.05). More subjects in the diabetes group than in the non-T2DM group were male, married, retirees, and had an unhealthy BMI (all P < 0.05).

As shown in Supplementary Table S1, compared with subjects who with neither hypertension nor T2DM, subjects who suffered from hypertension or T2DM or their comorbidity were more likely to be male and non-married, have a lower level of education, be retirees, have an unhealthy diet, and have an unhealthy BMI (all P < 0.05). Five individual lifestyle factors were all strongly correlated with HLS (all P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S2).

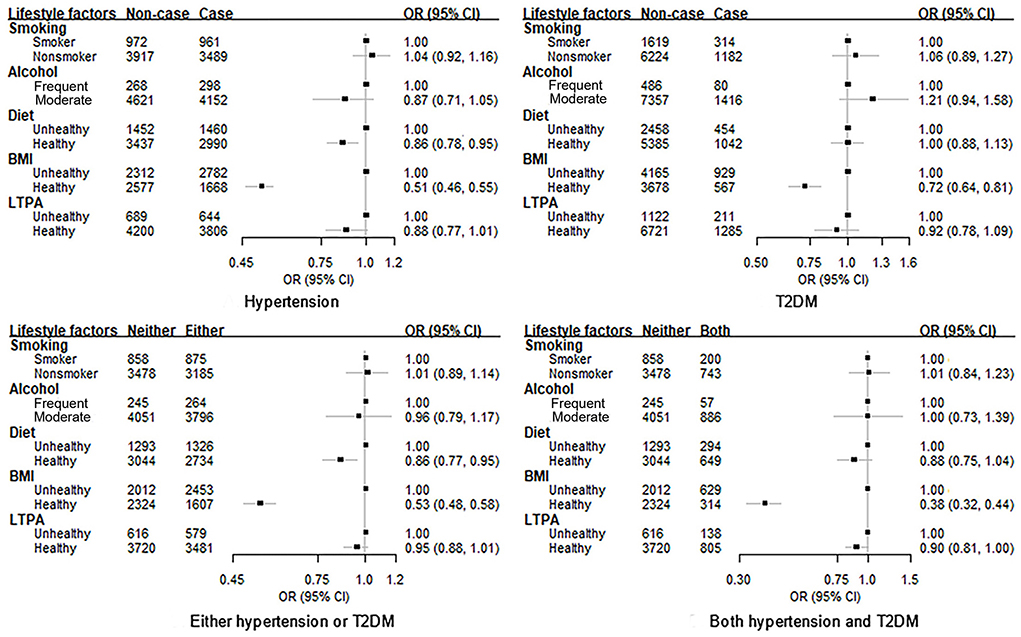

For individual lifestyle factors, as shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Tables S3–S5, healthy BMI was observed to be associated with a lower risk of hypertension (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.46–0.55) and T2DM (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.64–0.81) respectively after adjusting for confounders, while the healthy diet was only associated with a reduced risk of hypertension (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.95). When considering hypertension and T2DM simultaneously, similarly, only healthy BMI was associated with a decreased risk of the comorbidity of both hypertension and T2DM (OR: 0.38, 95% CI 0.32–0.44) after considering for confounders.

Figure 1. Association between each lifestyle factor and the risk of hypertension, T2DM and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia. BMI, body mass index; LTPA, leisure-time physical activity; OR, odds radio; CI, confidence interval; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adjust for age, sex, education, marital status, retirement status, diabetes (only for the association with hypertension) or hypertension (only for the association with diabetes), and all other lifestyle factors.

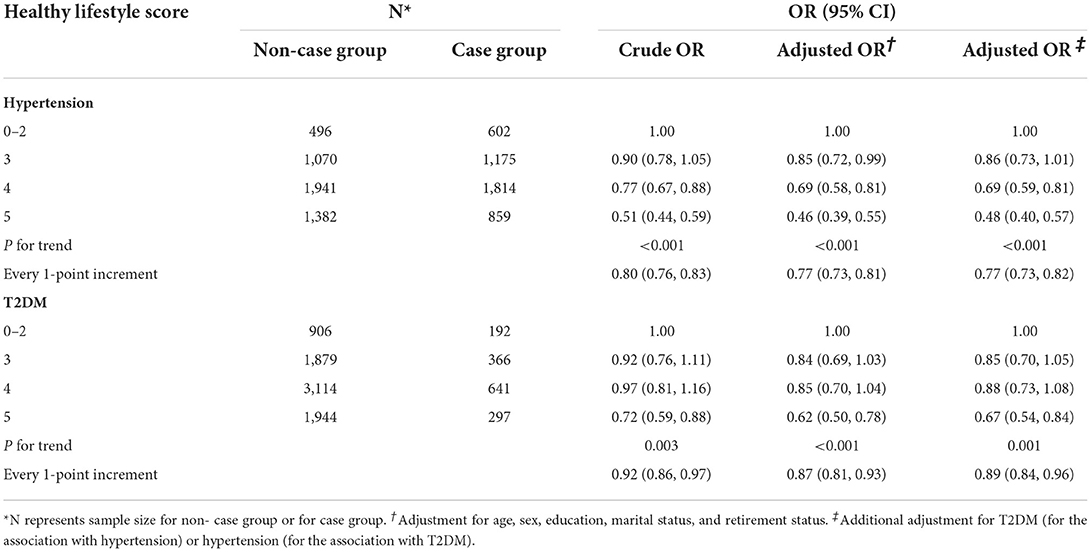

An increment of HLS was significantly associated with a lower risk of hypertension and T2DM (both P−trend < 0.05) after adjusting for confounders (Table 3). Compared with the subjects with 0–2 HLS, the OR for hypertension for subjects with 3, 4, and 5 HLS was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.73–1.01), 0.69 (95% CI: 0.59–0.81), and 0.48 (95% CI: 0.40–0.57), respectively, after adjusting for all confounders. Compared with the subjects with 0–2 HLS, the OR for T2DM for subjects with 3, 4, and 5 HLS was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.70–1.05), 0.88 (95% CI: 0.73–1.08), and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.54–0.84), respectively, after adjusting for all confounders. Every 1-point increment of HLS was associated with a 23% (OR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.73–0.82) decreased risk of hypertension and 11% (OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.84–0.96) reduced risk of T2DM.

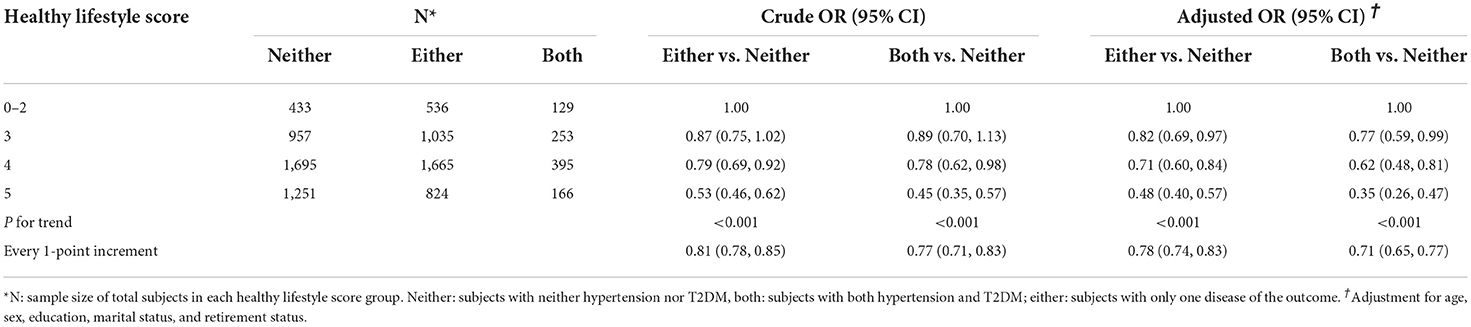

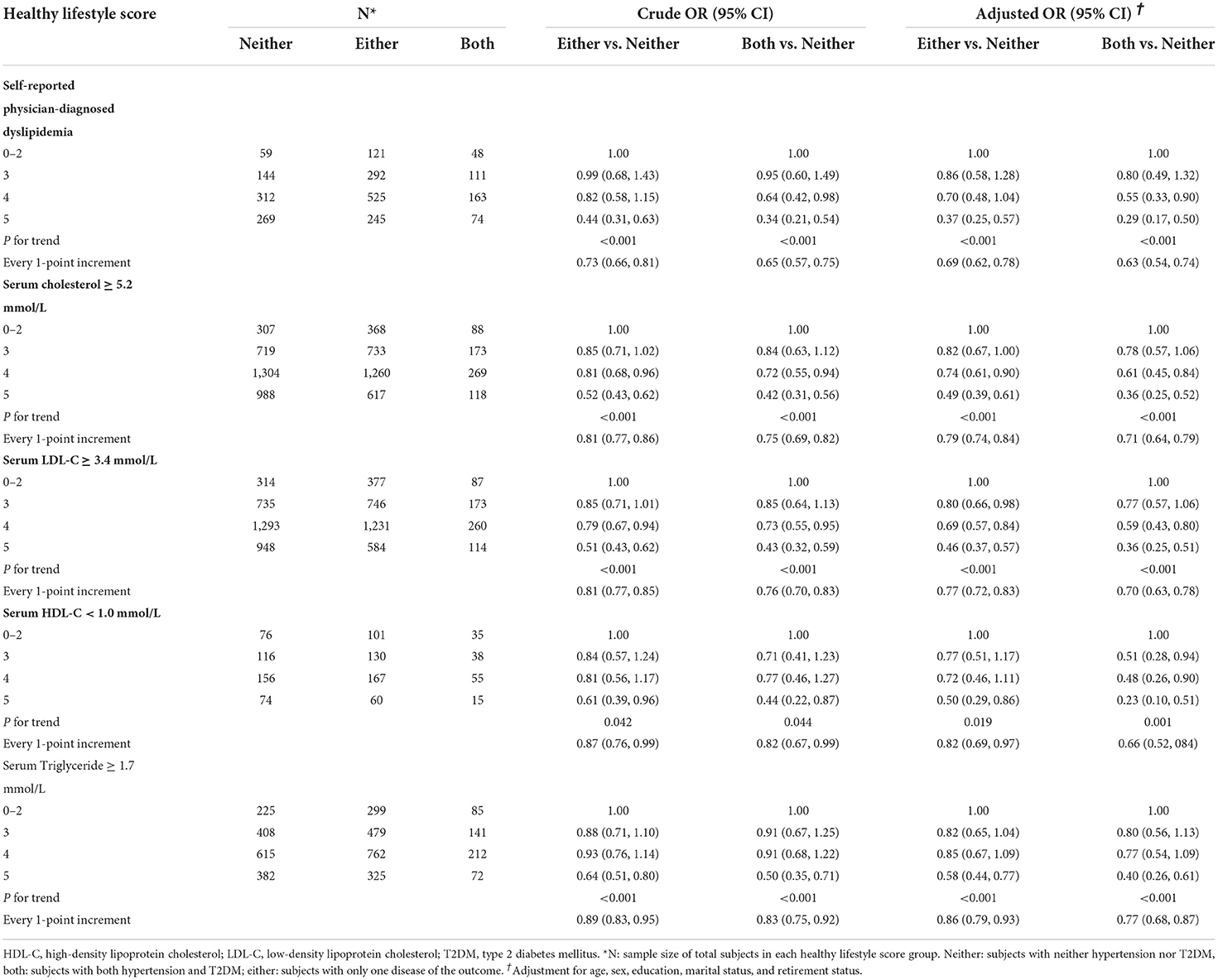

As seen in Table 4, individuals with a higher HLS had a lower risk of suffering from either or both hypertension and T2DM when compared with those being non-hypertension and non-T2DM (both P−trend < 0.05). Compared with the subjects with 0–2 HLS, the ORs of suffering from either but not both hypertension and T2DM for subjects with 3, 4, and 5 HLS were 0.82 (95% CI 0.69–1.02), 0.71 (95% CI 0.60–0.84), and 0.48 (95% CI 0.40–0.57) after adjusting for confounders; the ORs of suffering from both hypertension and T2DM for subjects with 3, 4, and 5 HLS were 0.77 (95% CI 0.59–0.99), 0.62 (95% CI 0.48–0.81), and 0.35 (95% CI 0.26–0.47) after adjusting for confounders.

Table 4. Association between healthy lifestyle score and the risk of comorbidity of hypertension and T2DM using multi-nominal logistic regression.

When stratified by sex and retirement, a higher HLS was associated with a lower risk of hypertension in each subgroup; however, a higher HLS was significantly associated with a lower risk of T2DM only in females and retirees (Supplementary Tables S6, S7). The multiplicative interactions of HLS with sex (P−interaction = 0.005) and retirement (P−interaction < 0.001) on hypertension, and with sex (P−interaction = 0.033) on T2DM, were observed. Likewise, a higher HLS prevented subjects with dyslipidemia suffering from one or both hypertension and T2DM in both males and females, retirees, and non-retirees (Supplementary Tables S8, S9); stronger associations existed in females and non-retirees (all P−interaction < 0.001).

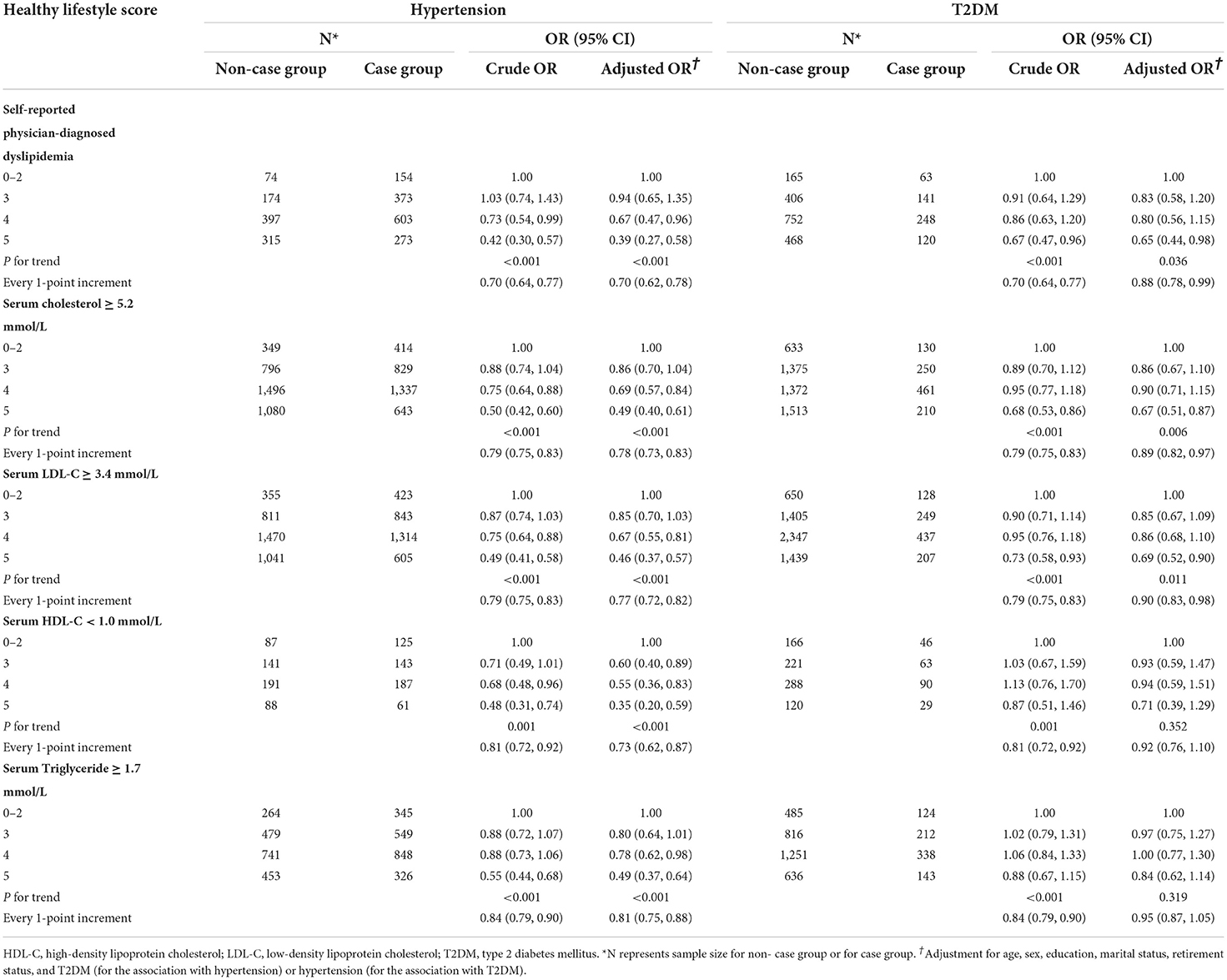

In sensitivity analysis, as seen in Table 5, an increment of HLS was associated with a lower risk of hypertension and T2DM after adjusting for confounders in different dyslipidemia subtypes, however, the association between HLS and T2DM risk was not significant in serum HDL-C < 1.0 mmol/L group and in serum triglyceride ≥ 1.7 mmol/L group. As shown in Table 6, individuals with a higher HLS had a lower risk of suffering from either or both hypertension and T2DM when compared with those being non-hypertension and non- T2DM in different dyslipidemia subtypes (all P−trend < 0.05). Besides, using a weighted lifestyle score did not alter the results remarkably (Supplementary Table S10); repeated analyses also yielded similar results by using the median in place of the WHO-recommended cut-off value of LTPA in generating HLS, by using 25 kg/m2 as the cut-off value for healthy and unhealthy BMI in generating HLS, and by replacing BMI with waist circumference as a component of HLS, by excluding subjects with BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2, and by excluding subjects aged 75 years or above, and with additional adjustment for the number of dyslipidemia indicators (Supplementary Tables S11–S17).

Table 5. Association between healthy lifestyle score and the risk of hypertension and T2DM according to different dyslipidemia definitions.

Table 6. Association between healthy lifestyle score and the risk of comorbidity of hypertension and T2DM according to different dyslipidemia definitions.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale population-based study conducted in China to investigate both individual and combined effects of healthy lifestyle factors on the risk of hypertension and T2DM among subjects with dyslipidemia. Our study found that HLS established by five main modifiable lifestyle factors, including smoking, alcohol drinking, diet, BMI, and LTPA, was adversely associated with the risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their commodity among subjects with dyslipidemia. Consistent results were also yielded in a series of sensitivity analyses, highlighting the importance of adopting a healthy lifestyle to prevent hypertension and diabetes among the populations with dyslipidemia.

Our results are broadly consistent with previous studies conducted among the general population (11, 12, 14, 29–33). Although lifestyle factors included in these studies were slightly different, findings of all studies consistently revealed beneficial effects on hypertension and diabetes by adopting healthy lifestyles. In two prospective cohort studies of women (29, 30) and a prospective cohort study of men (11), adherence to more healthy lifestyle factors was associated with a decreased risk of self-reported hypertension. A prospective cohort study in Australia also reported that having a higher number of lifestyle risk factors (i.e., high BMI, high alcohol intake, low physical activity levels, current smoking, low vegetable and fruit intake, and high risk of psychological distress) was associated with a higher risk of self-reported hypertension among middle-aged and older adults (12). A recent report from the Hortega Study found that adherence to 3–5 healthy lifestyle factors, relative to those with 0–1 healthy lifestyle factors, showed an 80% decreased risk of T2DM (32). In a cohort study in Spain, healthy lifestyle behaviors, including traditional modified lifestyle factors and other lifestyle indicators not typically included in risk scores, were associated with a 46% relative decreased hazard of T2DM (33). In addition, our results show that adherence to a healthier lifestyle is associated with a reduced risk of one or both comorbidities of hypertension and type 2 diabetes in subjects with dyslipidemia, and the effect is more pronounced in subjects with comorbidities. Our results for the first time indicated that even in the subjects with dyslipidemia, adherence to healthier lifestyle behaviors still exerts beneficial effects on preventing hypertension and T2DM and needs to be encouraged.

Our study showed that among the subjects with dyslipidemia, a healthy BMI was still a significant protective factor for hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity. A retrospective cross-sectional study involving 90,047 adults aged 18–85 years indicated that a higher BMI was associated with an increased prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia in both Japan and the USA (34). Another study conducted in China also found that overweight and obese individuals had a significantly higher risk than normal-weight people to develop hypertension, and dyslipidemia significantly shared interactions with overweight and obesity that increased the risk of hypertension (35). A meta-analysis including 18 prospective cohort studies showed that obesity and overweight were associated with about 7-fold risk and 3-fold risk of diabetes (36). Compared with subjects with healthy BMI, overweight and obese individuals are more likely to suffer metabolism disorders and insulin resistance, which may lead to the occurrence of hypertension and diabetes (35). Hence, sustained weight loss may be the primary driver of decreased risk of hypertension, diabetes, and other cardiometabolic diseases in the long term (37, 38). We also found that a healthy diet was associated with a lower risk of hypertension and of suffering from either hypertension or T2DM in the subjects with dyslipidemia. A previous study from NHS showed that adopting a low-risk diet was associated with a significantly lower incidence of hypertension among general women (29). However, we did not find an apparent association between other lifestyle factors with the risk of hypertension, T2DM, or their comorbidity. Similar results were also reported in the previous studies (39, 40). Even so, this current study showed that HLS was associated with a decreased risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity, which may be due to that the beneficial effect of different components of HLS is synergistic and cumulative, and the synergistic association of these factors became greater than individual effect. Our findings highlighted the importance of a combined health effect of different lifestyle behaviors for the prevention of hypertension and T2DM among subjects with dyslipidemia, instead of just concerning a single lifestyle choice.

One interesting result of the present study was that the negative associations between HLS and the risk of hypertension, T2DM, and suffering from one or both hypertension and T2DM were stronger in females than in males, which was consistent with previous reports (12, 41). The reason for this difference may be due to physiologic changes related to aging, changes in sex hormones, increased arterial stiffness, and lower responsiveness of the sympathetic nervous system (30, 42, 43). We also found a stronger association of HLS with the risk of hypertension and suffering from one or both hypertension and T2DM in non-retirees than in retirees. The physical damage from years of work was unavoidable, which may negatively affect retirees' physical function in their old age (44).

There are several strengths in our study. First, this is the first large-scale population-based study among Chinese adults to explore the association of combined effects of healthy lifestyle factors with the risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity in the subjects with dyslipidemia. Our findings will provide useful clues for further prospective studies. Second, subjects in the present study were recruited by using the multistage sampling method, which can potentiate the representativeness of subjects and minimize selection bias to some degree. Moreover, the questionnaire survey was conducted face to face by trained medical workers, which can to some degree reduce the information bias. Third, a series of sensitivity analyses were carried out and consistent results were displayed, which indicated a relatively good internal consistency for the HLS assessed.

Some limitations also exist in this study. First, this study was a cross-sectional study, which limited the ability to determine the direction of the association and infer a causal association. Second, the diagnosis of T2DM was determined by fasting blood glucose and self-report, but a lack of oral glucose tolerance test and determination of glycosylated hemoglobin may cause a few subjects with diabetes to not be identified; however, this would not lead to a fundamental change in the results of the study. Third, dietary information over the past 12 months was collected from each subject using the FFQ, which might result in recall bias inevitably. However, face-to-face questionnaire surveys and physical examinations were conducted at baseline by trained medical workers, which can to a large degree reduce the bias. Finally, although our study adjusted for several possible confounders, there may be residual confounding due to unmeasured factors, such as genetic factors. However, GZHS is an ongoing cohort study, possible confounding factors will be added in future research to verify our study.

Conclusions

In summary, the results suggest that the more kinds of healthy lifestyle, the lower the risk of hypertension, T2DM, and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia. Preventive strategies integrating multiple-dimensional lifestyle factors may provide a more feasible approach for the prevention and management of main chronic diseases.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Biomedical Research, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XL and HD conceived the study. XL, WZ, and HD supervised the study. MZ, JH, XD, MX, YZ, YL, and LL collected the data. PH analyzed the data. PH, MZ, and XD drafted the manuscript. WZ, HZ, HD, and XL reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors provided comments and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou City (No. 202102080404), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2022A1515010686), the Guangdong Provincial Key R&D Program (No. 2019B020230004), and the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC1312502).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank epidemiologist, nurses, and doctors in Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, in Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, in community healthcare centers in data collection, and thank all study subjects for their participation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.1006379/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; HLS, healthy lifestyle score; LTPA, leisure-time physical activity; OR, odds ratio; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

References

1. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 387:957–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8

2. Aune D, Schlesinger S, Neuenschwander M, Feng T, Janszky I, Norat T, et al. Diabetes mellitus, blood glucose and the risk of heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Nutr Metabol Cardiov Dis. (2018) 28:1081–91. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.07.005

3. Xing L, Jing L, Tian Y, Yan H, Zhang B, Sun Q, et al. Epidemiology of dyslipidemia and associated cardiovascular risk factors in northeast china: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Metabol Cardiov Dis. (2020) 30:2262–70. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.07.032

4. Teo KK, Rafiq T. Cardiovascular risk factors and prevention: a perspective from developing countries. Can J Cardiol. (2021) 37:733–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.02.009

5. Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990-2010: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. (2013) 381:1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1

6. Stanaway JD, Afshin A, Gakidou E, Lim SS, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1923–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6

7. Zhang M, Deng Q, Wang L, Huang Z, Zhou M, Li Y, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and achievement of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets in Chinese adults: a nationally representative survey of 163,641 adults. Int J Cardiol. (2018) 260:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.069

8. Lu Y, Zhang H, Lu J, Ding Q, Li X, Wang X, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and availability of lipid-lowering medications among primary health care settings in China. JAMA network open. (2021) 4:e2127573. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27573

9. Halperin RO, Sesso HD, Ma J, Buring JE, Stampfer MJ, Gaziano JM. Dyslipidemia and the Risk of Incident Hypertension in Men. Hypertension. (2006) 47:45–50. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196306.42418.0e

10. Peng J, Zhao F, Yang X, Pan X, Xin J, Wu M, et al. Association between dyslipidemia and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged and older chinese adults: a secondary analysis of a nationwide cohort. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e042821. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042821

11. Banda JA, Clouston K, Sui X, Hooker SP, Lee CD, Blair SN. Protective health factors and incident hypertension in men. Am J Hypertens. (2010) 23:599–605. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.26

12. Nguyen B, Bauman A, Ding D. Association between lifestyle risk factors and incident hypertension among middle-aged and older australians. Prevent Med. (2019) 118:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.007

13. Gao J, Wang L, Liang H, He Y, Zhang S, Wang Y, et al. The association between a combination of healthy lifestyles and the risks of hypertension and dyslipidemia among adults-evidence from the northeast of China. Nutr Metabol Cardiov Dis. (2022) 32:1138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2022.01.020

14. Zhang Y, Pan XF, Chen J, Xia L, Cao A, Zhang Y, et al. Combined lifestyle factors and risk of incident type 2 diabetes and prognosis among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetologia. (2020) 63:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-04985-9

15. Deng H, Guo P, Zheng M, Huang J, Xue Y, Zhan X, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of atrial fibrillation in southern china: results from the guangzhou heart study. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:17829. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35928-w

16. Duan X, Huang J, Zheng M, Zhao W, Lao L, Li H, et al. Association of healthy lifestyle with risk of obstructive sleep apnea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med. (2022) 22:33. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01818-7

17. Du Y, Duan X, Zheng M, Zhao W, Huang J, Lao L, et al. Association between eating habits and risk of obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based study. Nat Sci Sleep. (2021) 13:1783–95. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S325494

18. Duan X, Zheng M, Zhao W, Huang J, Lao L, Li H, et al. Associations of depression, anxiety, and life events with the risk of obstructive sleep apnea evaluated by berlin questionnaire. Front Med. (2022) 9:799792. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.799792

19. Duan X, Zheng M, He S, Lao L, Huang J, Zhao W, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. (2021) 25:1925–34. doi: 10.1007/s11325-021-02318-y

20. World Health Organization. Classification of Diabetes Mellitus 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/classification-of-diabetes-mellitus (accessed March 13, 2021).

21. China adult dyslipidemia control guidelines revision joint committee. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Chinese Adults (Revised Edition, 2016). Chin Circulat J. (2016) 31:937–53. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2016.10.001

22. Chinese Nutrition Society. The Chinese Dietary Guidelines (2022). Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House (2022).

23. Chen C, Lu FC, Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health PRC. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. (2004) 17:1–36.

24. World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (Gpaq) (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/GPAQ_EN.pdf (accessed April 5, 2021).

25. Hu P, Zheng M, Huang J, Zhao W, Wang HHX, Zhang X, et al. Association of habitual physical activity with the risk of all-cause mortality among Chinese adults: a prospective cohort study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:919306. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.919306

26. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54:1451–62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

27. Deng YY, Zhong QW, Zhong HL, Xiong F, Ke YB, Chen YM. Higher healthy lifestyle score is associated with lower presence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged and older chinese adults: a community-based cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 24:5081–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000902

28. Bao Y, Lu J, Wang C, Yang M, Li H, Zhang X, et al. Optimal waist circumference cutoffs for abdominal obesity in Chinese. Atherosclerosis. (2008) 201:378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.03.001

29. Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated with Incident Hypertension in Women. JAMA. (2009) 302:401–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1060

30. Cohen L, Curhan GC, Forman JP. Influence of Age on the Association between Lifestyle Factors and Risk of Hypertension. J Am Soc Hypert. (2012) 6:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.06.002

31. Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. (2001) 345:790–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492

32. Delgado-Velandia M, Gonzalez-Marrachelli V, Domingo-Relloso A, Galvez-Fernandez M, Grau-Perez M, Olmedo P, et al. Healthy lifestyle, metabolomics and incident type 2 diabetes in a population-based cohort from Spain. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2022) 19:8. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01219-3

33. Ruiz-Estigarribia L, Martínez-González MA, Díaz-Gutiérrez J, Sayón-Orea C, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Bes-Rastrollo M. Lifestyle behavior and the risk of type 2 diabetes in the seguimiento universidad de navarra (Sun) cohort. Nutr Metabol Cardiov Dis. (2020) 30:1355–64. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.04.006

34. Kuwabara M, Kuwabara R, Niwa K, Hisatome I, Smits G, Roncal-Jimenez CA, et al. Different risk for hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hyperuricemia according to level of body mass index in Japanese and American subjects. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1011. doi: 10.3390/nu10081011

35. Tang N, Ma J, Tao R, Chen Z, Yang Y, He Q, et al. The effects of the interaction between bmi and dyslipidemia on hypertension in adults. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:927. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-04968-8

36. Abdullah A, Peeters A, de Courten M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diab Res Clin Pract. (2010) 89:309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.012

37. Tyson CC, Appel LJ, Vollmer WM, Jerome GJ, Brantley PJ, Hollis JF, et al. Impact of 5-year weight change on blood pressure: results from the weight loss maintenance trial. J Clin Hypert. (2013) 15:458–64. doi: 10.1111/jch.12108

38. Delahanty LM, Pan Q, Jablonski KA, Aroda VR, Watson KE, Bray GA, et al. Effects of weight loss, weight cycling, and weight loss maintenance on diabetes incidence and change in cardiometabolic traits in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. (2014) 37:2738–45. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0018

39. Fretts AM, Howard BV, McKnight B, Duncan GE, Beresford SA, Mete M, et al. Life's simple 7 and incidence of diabetes among american indians: the strong heart family study. Diabetes Care. (2014) 37:2240–5. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2267

40. Joseph JJ, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Carnethon MR, Bertoni AG, Shay CM, Ahmed HM, et al. The association of ideal cardiovascular health with incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Diabetologia. (2016) 59:1893–903. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4003-7

41. Mozaffarian D, Kamineni A, Carnethon M, Djoussé L, Mukamal KJ, Siscovick D. Lifestyle risk factors and new-onset diabetes mellitus in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. (2009) 169:798–807. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.21

42. Dubey RK, Oparil S, Imthurn B, Jackson EK. Sex hormones and hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. (2002) 53:688–708. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00527-2

43. Maric C. Sex, Diabetes and the Kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2009) 296:F680–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90505.2008

Keywords: hypertension, diabetes, comorbidity, subjects with dyslipidemia, lifestyle

Citation: Hu P, Zheng M, Duan X, Zhou H, Huang J, Lao L, Zhao Y, Li Y, Xue M, Zhao W, Deng H and Liu X (2022) Association of healthy lifestyles on the risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia. Front. Nutr. 9:1006379. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1006379

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 09 September 2022;

Published: 26 September 2022.

Edited by:

Diego Augusto Santos Silva, Federal University of Santa Catarina, BrazilReviewed by:

Chen Jiageng, Tianjin Medical University, ChinaXia Gong, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2022 Hu, Zheng, Duan, Zhou, Huang, Lao, Zhao, Li, Xue, Zhao, Deng and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenjing Zhao, emhhb3dqJiN4MDAwNDA7c3VzdGVjaC5lZHUuY24=; Hai Deng, ZG9jdG9yZGgmI3gwMDA0MDtob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Xudong Liu, eGRsaXUuY24mI3gwMDA0MDtob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Peng Hu

Peng Hu Murui Zheng3†

Murui Zheng3† Xueru Duan

Xueru Duan Hai Deng

Hai Deng Xudong Liu

Xudong Liu