94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Nutr. , 15 November 2021

Sec. Nutritional Epidemiology

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.760437

Introduction: Double burden of malnutrition (DBM) is a fast-evolving public health challenge. The rising prevalence of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases alongside persistent nutritional deficiencies are compelling problems in many developing countries. However, there is limited evidence on the coexistence of these conditions in the same individual among community-dwelling adults. This cross-sectional study describes the various forms of DBM and examines the determinants of DBM at the individual level among adults in the Philippines.

Materials and Methods: A nationwide dataset from the 2013 Philippine National Nutrition Survey was used. The final study sample consisted of 17,157 adults (8,596 men and 8,561 non-pregnant and non-lactating women). This study focused on three DBM types within adults: (#1) Underweight and at least one cardiometabolic risk factor (Uw + ≥1 CMRF), (#2) Anemia and at least one cardiometabolic risk factor (An + ≥1 CMRF), (#3) Vitamin A deficiency or iodine insufficiency and at least one cardiometabolic risk factor (Other MND + ≥1 CMRF). The total double burden of malnutrition was also evaluated as the sum of the aforementioned three types. Logistic regression models were used to assess associations between socio-demographic and lifestyle factors and DBM.

Results: The prevalence of the three types of DBM were: type #1, 8.1%; type #2, 5.6%; type #3, 20.6%, and the total DBM prevalence was 29.4%. Sex, age, educational attainment, employment status, wealth quintile, and alcohol drinking were the risk factors for DBM. In contrast, marital status, smoking, and physical activity were associated with the different DBM types.

Conclusion: The study findings contribute to the current state of knowledge on the broad spectrum of individual-level DBM. Understanding the disparities of this phenomenon could guide integrated actions directed to the concomitance of malnutrition in various forms and cardiometabolic disease risks.

Many developing countries are facing nutrition transitions propelled by socioeconomic and technological advancements (1). These shifts have led to a rise in obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases (2). Parallel to this, micronutrient deficiency remains highly prevalent in these countries (3). Evidence suggests that nutrition transition contributes to the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) or “the coexistence of undernutrition or micronutrient deficiency along with overweight, obesity, or diet-related NCDs” (4).

The Philippines suffers from this double nutritional burden, as evident in the annual increase of overweight/obesity among adults at 0.73% over 20 years (1993–2013). In addition, the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease risks (overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity, elevated fasting blood glucose, and abnormalities in blood lipid levels) continuously rise. Worse still, chronic energy deficiency, anemia, and vitamin A deficiency are significant public health problems in Filipino adults (5).

Past studies undertaken in the Philippines investigating DBM have primarily focused on the overlap between underweight and overweight/obesity in the population (6–8) or within households (9). Thus, the double burden of malnutrition at the individual level has not been adequately studied. Research documenting the distribution of adults who are underweight or micronutrient deficient and at the same time experiencing cardiometabolic risk factors (CMRF) are also scarce and limited to urban settings (10–15). Hence, our study aims were: (1) to determine the extent of individual-level DBM among Filipino adults, and (2) to identify the association of DBM with socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics.

We analyzed data from the 2013 National Nutrition Survey (NNS) of the Philippines, publicly available at http://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/site/home.php (16). The NNS is a cross-sectional survey conducted to define the country's food and nutrition situation (5). In brief, the survey adopted the 2003 Master Sample of the National Statistics Office and utilized a stratified three-stage sampling design (17). Data were collected from 35,825 households across 17 regions of the country between June 2013 to April 2014. A complete description of the 2013 NNS survey methodology has been published previously (5, 18).

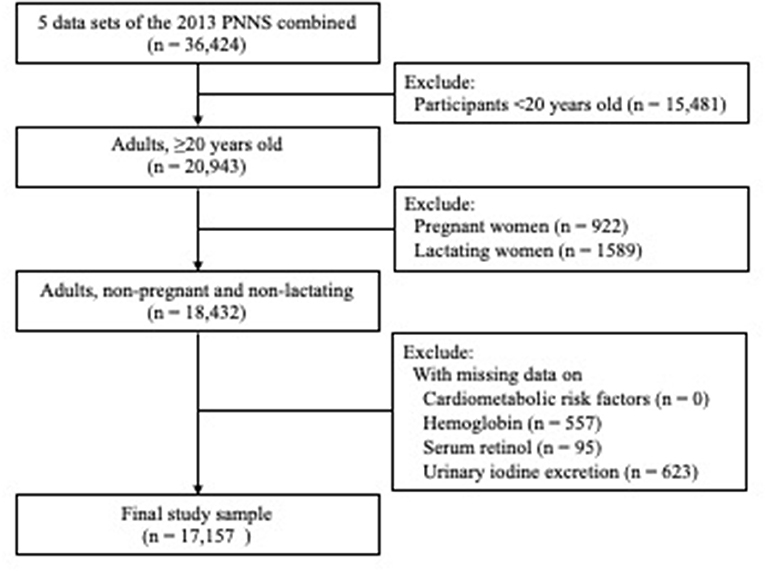

This study was limited to adults (≥20 years) with complete subject identification in the anthropometry, biochemical, clinical, and socioeconomic (individual and household) survey components. Moreover, pregnant and lactating women and those with missing values on cardiometabolic risk factors, hemoglobin, serum retinol, and urinary iodine excretion (UIE) were excluded. Accordingly, the final study sample involved 17,157 adults (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participants excluded in the study. Cardiometabolic risk factor was defined as an individual with any of the following four factors: (1) overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity; (2) hypertension; (3) hyperglycemia; (4) dyslipidemia (low HDL cholesterol or hypertriacylglycerolemia). There were no study participant with missing value on cardiometabolic risk factor.

Weight was measured using the Detecto™ platform beam balance weighing scale to the nearest 0.1 kg, and the Seca™ microtoise was utilized to obtain height to the nearest 0.1 cm (5). We used the weight and height measurements to calculate the body mass index (BMI). The BMI of adults were classified based on the World Health Organization recommended cut-off points: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) (19). Waist circumference was obtained with a calibrated tape measure midway between the lowest rib and tip of the hip bone while the participant was standing and breathing normally, and expressed to the nearest 0.1 cm. Abdominal obesity was defined as waist circumference ≥102 cm for males or ≥88 cm for females (20).

Blood pressure readings were taken with a calibrated non-mercurial sphygmomanometer (A&D Um-101™) and stethoscope on the participant's right arm after a minimum of 5 min rest. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice with at least 2-min intervals (5). A blood pressure measurement of ≥140/≥90 mmHg indicated hypertension (21).

Venous blood samples were drawn into vacutainers tubes with Lithium Heparin for plasma blood glucose and plain tubes for serum blood lipids. Afterwards, blood glucose and lipid profiles were analyzed utilizing the enzymatic colorimetric method with Roche COBAS Integra and Hitachi 912. The cut-off points for hyperglycemia was fasting blood glucose ≥110 mg/dL (22); low high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was <40 mg/dL for male or <50 mg/dL for female (23, 24); and hypertriacylglycerolemia was triglyceride ≥150 mg/dL (23, 24). The study participants were then classified as having CMRF if they had any of the following conditions: (1) overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity, (2) hypertension, (3) hyperglycemia, 4) dyslipidemia (low HDL cholesterol or hypertriacylglycerolemia) (14, 25).

During the survey, hemoglobin, serum retinol, and urinary iodine excretion were collected for the assessment of anemia, vitamin A deficiency, and iodine insufficiency, respectively. Hemoglobin was determined from venous blood samples using the cyanmethemoglobin method (5, 26). Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL for males or <12 g/dL for females (27). Serum retinol was extracted from the blood samples and examined by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography according to the method of Furr et al. (5, 28), where serum retinol of <10 μg/dL indicated vitamin A deficiency (29). Also, midstream urine samples were tested for UIE concentrations. The acid digestion/colorimetric method was employed to evaluate the UIE levels with a cut-off of <50 μg/dL for iodine insufficiency (30, 31).

The covariates in this study included sex, age, educational attainment, marital status, employment status, household size, wealth quintile, smoking, alcohol drinking, and physical activity. The participants' sex was classified as male or female. The age variable was categorized as 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years old, while educational attainment was grouped into elementary or lower, high school, and college or higher. Marital status was reported as single, married or with a partner, and others (widowed/separated/annulled/divorced). The status of employment utilized binary categories of employed and unemployed. Household size was constructed from the socioeconomic data sets and divided into three levels (1–3, 4–6, and ≥7). Wealth status, based on quintiles of household assets, was created utilizing principal component analysis (5). An individual who smoked either: (1) ≥1 cigarette daily/on a regular or occasional basis, or (2) not daily, but at least weekly/less often than weekly was considered as a current smoker (32). Current alcohol drinking was characterized as consumption of any alcoholic beverage during the past year (33). Low physical activity referred to not having: (1) ≥3 days of vigorous-intensity activity for at least 20 min per day, or (2) ≥5 days of moderate-intensity activity for at least 30 min per day (32).

We assessed three types of DBM at the individual level and each was a combination of nutritional deficiency along with any CMRF. Nutritional deficiency encompasses underweight and micronutrient deficiency/insufficiency. CMRF measurements included the following: overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia (low HDL cholesterol or hypertriacylglycerolemia) (14, 25). Thus, we categorized the three types of DBM as: (#1) co-occurrence of underweight and at least one CMRF (Uw + ≥1 CMRF), (#2) co-occurrence of anemia and at least one CMRF (An + ≥1 CMRF), (#3) co-occurrence of vitamin A deficiency or iodine insufficiency and at least one CMRF (Other MND + ≥1 CMRF). The total double burden of malnutrition was also reported as the sum of the three types (i.e., co-occurrence of underweight or anemia or vitamin A deficiency or iodine insufficiency and at least one CMRF). Since the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency was too small, we did not consider it as a different type.

All analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and survey sampling weights were employed to obtain results representative of adult population in the Philippines. We generated descriptive statistics for the socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics of the participants. The prevalence of underweight, overweight, obesity, cardiometabolic risk factors, micronutrient deficiency/insufficiency, and types of DBM were calculated. The chi-square test was utilized to identify the differences between sex and independent variables. We also conducted a bivariate analysis to describe variations with every determinant in each type of DBM and total DBM. Binary logistic regression was carried out to examine the relationships between DBM and socio-demographic and lifestyle factors. Multi-collinearity was assessed in all models, which were all <3, indicating no collinearity. The statistical significance of associations was identified at p < 0.05.

A total of 17,157 adults were included in the present study, with a balance between male and female participants (Table 1). The study samples were mostly in the 20–39 years age group (45.8%), finished high school education (38.2%), married or with a partner (67.0%), and employed (60.0%). There were slightly more females in the older age group (17.1%) and similarly, more females graduated from college or higher (31.8%). A higher proportion of males (26.5%) were single or unmarried, and 57.1% of females were unemployed.

Approximately 45% of the study participants belonged to households with 4–6 members, and no differences in sex were found. Regarding wealth status, more males were in the poorest and poor quintiles. For lifestyle factors, 27.1% were current smokers, 51.5% were current alcohol drinkers, and 43.5% had low physical activity. A markedly greater percentage of males were smokers and drinkers at the time of the survey. Inversely, more females had low physical activity.

The prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity was 11.2, 23.4, 6.2%, respectively, and these conditions were consistently higher in females than males (Table 2). A large proportion of the participants (84.4%) had at least one CMRF, which was higher in females. Among the metabolic syndrome components, the highest prevalence was for low HDL cholesterol (70.4%), while the lowest was hyperglycemia (9.9%). These components, except for hyperglycemia, showed statistical differences between males and females. Remarkably, abdominal obesity prevalence among females was seven times higher than males (20.8 vs. 2.9%). As for micronutrient deficiency/insufficiency, iodine insufficiency had the greatest prevalence (23.9%), whereas vitamin A deficiency was noted in a very small percentage of adults (0.1%). More female adults were affected by anemia and iodine insufficiency.

Table 2. Nutritional status, cardiometabolic risk factors, and double burden of malnutrition of adults in the Philippinesa.

Overall, 29.4% adults exhibited a double burden of malnutrition and was significantly higher for females than males. The prevalence of the three types of DBM was: (#1) the co-occurrence of underweight and at least one CMRF was 8.1%; (#2) the co-occurrence of anemia and at least one CMRF was 5.6%; and (#3) the co-occurrence of vitamin A deficiency or iodine insufficiency and at least one CMRF was 20.6%.

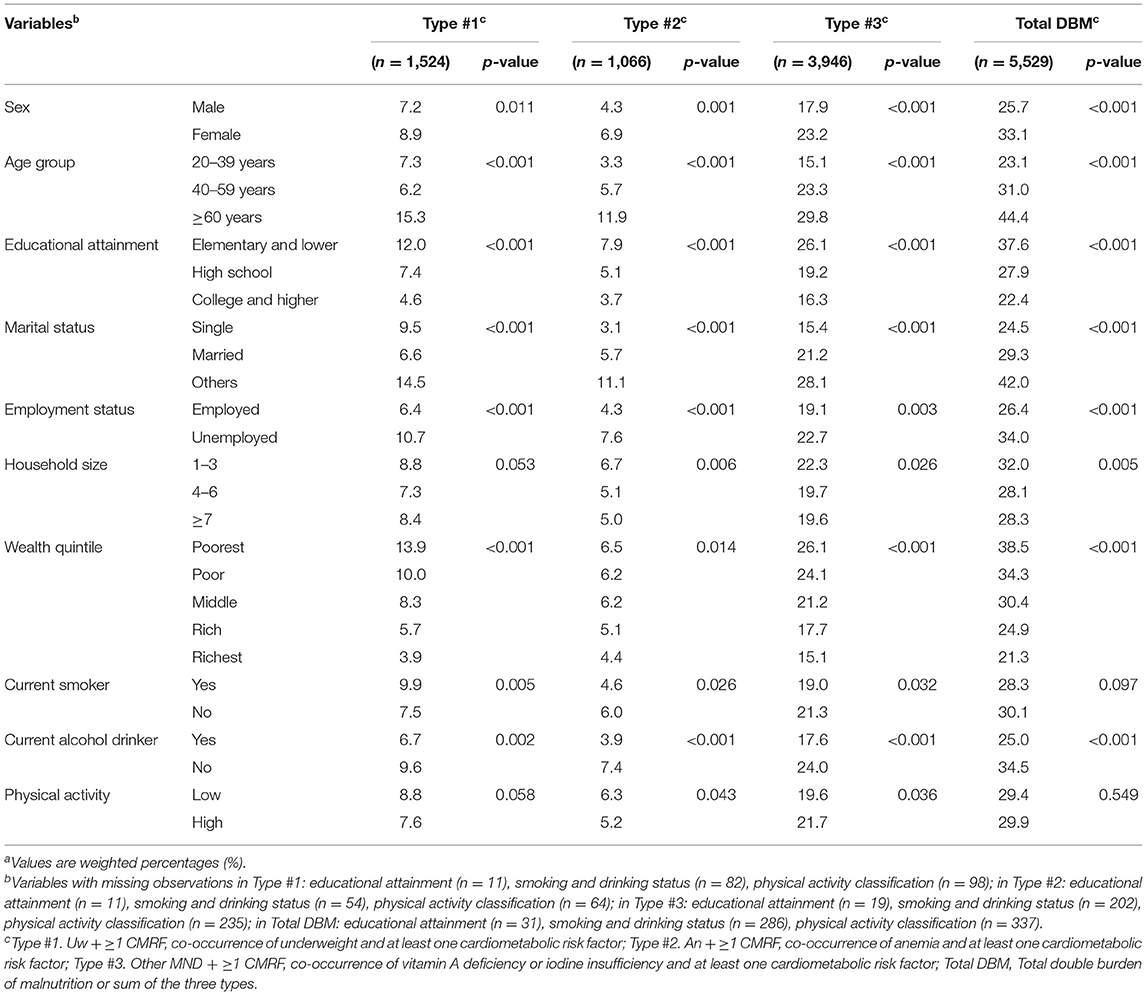

As shown in Table 3, significant differences between socio-demographic and lifestyle factors and DBM were identified. The prevalence of DBM was higher among females, aged ≥60 years old, with elementary education or below, widowed/separated/annulled/divorced, unemployed, residing in small-sized (1–3 members) and poorest households, and non-drinkers. To add, current smoking was correlated with the three DBM types. Significant differences were also observed in DBM types #2 and #3 for physical activity.

Table 3. Socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics of adults by double burden of malnutrition characterizationsa.

Table 4 displays the socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and types of DBM in the logistic regression models. We found that sex, age, educational attainment, employment status, wealth quintile, and alcohol drinking were associated with DBM at the individual level. Being a female had higher odds of experiencing DBM. Older adults (≥60 years) were twice likely to have DBM compared with younger adults (20–39 years). Furthermore, middle-aged adults (40–59 years) had a lower risk of DBM type #1 but not for the other types. Adults with higher education, unemployed, and non-current drinkers were significantly associated with DBM. Noteworthy, the odds of having DBM declined with improvement in the wealth quintile.

The variables of smoking and physical activity were associated only with a single type of DBM. Not smoking offered protection for DBM type #1, while engaging in high physical activity increased DBM type #3 risk. For marital status, those who were married had lower susceptibility to DBM type #1. No significant differences were noted for household size in any type of DBM.

To the best of our knowledge, this current study is one of the first to assess the broad spectrum of DBM at the individual level in Southeast Asia. The results highlight that nutritional deficiencies (underweight or micronutrient deficiency/insufficiency) simultaneously occur with cardiometabolic risk factors in the adult population. Moreover, the distribution of DBM varies across several socio-demographic and lifestyle parameters.

The prevalence of underweight, micronutrient deficiency/insufficiency, and cardiometabolic risk factors in this study were comparable with national estimates and past literature (34–36). Notably, overweight was twice higher than underweight in the adult population. For the dual burden of malnutrition, the overall DBM prevalence and DBM type #1 were higher than published studies (14, 15). However, caution must be taken when comparing the extent of DBM given the differences in the stage of nutrition transition across different countries, i.e., the Philippines is in the more advanced phase, whereas Burkina Faso is in the early phase (37, 38).

A wide range of socio-demographic and lifestyle factors was associated with DBM. Women bear an enormous burden of DBM, and late adulthood increases the odds of experiencing DBM. Females and older adults in the Philippines are at greater independent risk of having undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and cardiometabolic disease risks (5). Likewise, the strong DBM determinant of age may be ascribed to the biological and environmental changes in aging that may contribute to the development of DBM (4). This finding suggests that DBM may progressively become an age-related disease, and must be addressed as life expectancy continues to increase in the future.

Educational attainment, marital status, employment, and wealth quintile were the other DBM risk factors. A higher educational level was found to reduce the risk of DBM possibly through better dietary and lifestyle choices (39). Being married and widowed/separated/annulled/divorced was also related to DBM. These life transitions are stressful events that could positively or negatively alter an individual's psychosocial condition affecting their nutritional status. It was also hypothesized that the availability of financial resources and social support systems could also influence marital and health states (40, 41). Adults without employment were more vulnerable to any type of DBM. This is in line with a past research wherein underweight and anemia prevalence was highest among unemployed adults (35). In the same study, adults with no employment were less physically active than those who were employed, which may further explain this relationship (35). The association of household wealth with DBM indicates that these conditions are not a matter of affluence, i.e., it could happen in different wealth statuses. Angeles-Agdeppa et al. documented that an advancement in wealth among Filipino households was not always translated to better dietary intakes (42).

Smoking, alcohol drinking, and physical activity were the lifestyle factors correlated to DBM. Adults who were not currently smoking had lesser susceptibility to DBM type #1. Existing literature on tobacco use suggests that smoking increases the risk for non-communicable diseases through weight gain, inflammatory reactions, and oxidative stress (43, 44). Conversely, non-current drinkers and those physically active had higher a risk for DBM. It should be noted that non-current drinkers in this study covered adults who were lifetime abstainers or former drinkers. Alcohol consumption could affect nutrient metabolism and absorption, which may then lead to malnutrition. Evidence substantiates the adverse effects of alcohol intake on nutritional deficiencies and cardiometabolic disease risks (45, 46). It is widely known that exercise with optimal duration and intensity decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nonetheless, individuals who engage in physical activity may undergo modest and short-term changes in cardiometabolic disease risks (47–49). Taken altogether, these DBM determinants are potentially modifiable, and underlines that an integrated approach is vital to prevent malnutrition in all its forms.

The main strength of this study is the use of a large nationally representative dataset with biochemical markers for the investigation of micronutrient deficiencies and cardiometabolic risk factors. Nevertheless, we must interpret the study findings while considering some limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design did not allow for the life-course analysis of DBM, and the observed associations to be interpreted as causal. Second, unmeasured non-nutritional factors, i.e., inflammation, medication use, and disease history, may have biased the study. Third, we did not include data on food consumption that could help explain the nutritional outcomes. Finally, bias due to the missing variable may be limited because the models were adjusted for potentially important determinants of DBM that were not collinear.

To conclude, our study findings confirm the persistence of undernutrition amidst cardiometabolic risk factors among Filipino adults. The overall prevalence of individual-level DBM was 29.4%. Sex, age, educational attainment, employment status, wealth quintile, and alcohol drinking were the factors related to DBM. On the other hand, marital status, smoking, and physical activity were associated with the different types of DBM. These factors alter the various forms of malnutrition and cardiometabolic risk factors through unhealthy diets and lifestyles. Given the ongoing nutrition transition in the Philippines, it is imperative to tackle these nutritional problems simultaneously through double-duty actions. This may involve programs focusing on women's nutrition, and social policies such as continued investments in education and employment opportunities. A holistic and intensified approach to promote healthy diets and lifestyles is equally important to improve the nutritional landscape of adults.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/site/home.php.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Research Ethics Committee of National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City, Taiwan. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AJ, W-CH, and SH designed the research. AJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. W-CH and AJ analyzed the data. SH supervised the research and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We acknowledge the Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology, Philippines for providing access to the 2013 National Nutrition Survey data.

1. Popkin BM, Corvalan C, Grummer-Strawn LM. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet. (2020) 395:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0140–6736(19)32497–3

2. World Health Organization. WHO Technical Report Series on Obesity: Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization (2003). Available online at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed September 21, 2020).

3. Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. (2008) 371:243–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140–6736(07)61690–0

4. World Health Organization. The Double Burden of Malnutrition Policy Brief. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-17.3 (accessed September 21, 2020).

5. Department of Science and Technology-Food and Nutrition Research Institute. eNutrition, Facts and Figure 2013 National Nutrition Survey. Taguig: Department of Science and Technology-Food and Nutrition Research Institute (2015). Available online at: https://www.fnri.dost.gov.ph/index.php/19-nutrition-statistic/175-national-nutrition-survey#facts-and-figures (accessed September 03, 2020).

6. Florentino RF, Villavieja GM, Laña RD. Regional study of nutritional status of urban primary schoolchildren 1 Manila, Philippines. Food Nutr Bull. (2002) 23:24–30. doi: 10.1177/156482650202300104

7. Angeles-Agdeppa I, Gayya-Amita PI, Longalong WP. Existence of double burden of malnutrition among Filipino children in the same age-groups and comparison of their usual nutrient intake. Malays J Nutr. (2020) 25:445–61. doi: 10.31246/mjn−2019–0079

8. Leyso NLC, Palatino MC. Detecting local clusters of under-5 malnutrition in the Province of Marinduque, Philippines using spatial scan statistic. Nutr Metab Insights. (2020) 13:1–6. doi: 10.1177/1178638820940670

9. Angeles-Agdeppa I, Lana RD, Barba CV. A case study on dual forms of malnutrition among selected households in District 1, Tondo, Manila. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2003) 12:438–46.

10. Danquah I, Dobrucky CL, Frank LK, Henze A, Amoako YA, Bedu-Addo G, et al. Vitamin A: potential misclassification of vitamin A among patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in urban Ghana. Am J Clin Nutr. (2015) 102:207–14. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.101345

11. Jones AD, Hayter AKM, Baker CP, Prabhakaran P, Gupta V, Kulkarni B, et al. The co-occurrence of anemia and cardiometabolic disease risk demonstrates sex-specific socio-demographic patterning in urbanizing rural region of southern India. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2015) 70:364–72. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.177

12. Traissac P, El Ati J, Gartner A, Ben Gharbia H, Delpeuch F. Gender inequalities in excess adiposity and anaemia combine in a large double burden of malnutrition gap detrimental to women in an urban area in North Africa. Public Health Nutr. (2016) 19:1428–37. doi: 10.1017/s1368980016000689

13. Yu EA, Finkelstein JL, Brannon PM, Bonam W, Russell DG, Glesby MJ, et al. Nutritional assessment among adult patients with suspected or confirmed active tuberculosis disease in rural India. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0233306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233306

14. Zeba AN, Delisle HF, Renier G, Savadogo B, Baya B. The double burden of malnutrition and cardiometabolic risk widens the gender and socioeconomic health gap: a study among adults in Burkina Faso (West Africa). Public Health Nutr. (2012) 15:2210–19. doi: 10.1017/s1368980012000729

15. Zeba AN, Delisle HF, Renier G. Dietary patterns and physical inactivity, two contributing factors for the double burden of malnutrition among adults in Burkina Faso, West Africa. J Nutr Sci. (2014) 3:e50. doi: 10.1017/jns.2014.11

16. Department of Science and Technology-Food and Nutrition Research Institute. Data from: 2013 National Nutrition Survey Department of Science and Technology-Food and Nutrition Research Institute Public Use File (2018). Available online at: http://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/site/home.php (accessed February 14, 2020).

17. Barcenas ML. The development of the 2003 Master Sample (MS) for Philippine Household Surveys. In: Proceedings of the 9th National Nutrition on Statistics. Manila (2004).

18. Patalen CF, Ikeda N, Angeles-Agdeppa I, Vargas MB, Nishi N, Duante CA, et al. Data resource profile: the Philippine National Nutrition Survey (NNS). Int J Epidemiol. (2020) 49:742–3. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa045

19. World Health Organization. WHO Technical Report Series on Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization (2000). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42330 (accessed September 21, 2020).

20. World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization (2011). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501491 (accessed September 03, 2020).

21. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eight Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. (2014) 311:507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427

22. World Health Organization. Definition, Diagnosis, and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation, Part 1, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization (1999).

23. Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. (2001) 285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486

24. Grundy SM, Brewer Jr HB, Cleeman JI, Smith Jr SC, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on Scientific Issues Related to Definition. Circulation. (2004) 109:433–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000111245.75752.c6

25. Delisle H. Double burden of malnutrition at the individual level. Sight and Life. (2018) 32:76–81.

26. International Committee for Standardization in Haematology. International Committee for Standardization in Haematology: protocol for type testing equipment and apparatus used for haematological analysis. J Clin Pathol. (1978) 31:275–79. doi: 10.1136/jcp.31.3.275

27. World Health Organization United Nations Children's Fund United Nations University. Iron Deficiency Anaemia: Assessment, Prevention and Control, a Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85839/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_11.1_eng.pdf (accessed September 26, 2020).

28. Furr HC, Tanmihardjo SA, Olson JA. Training Manual for Assessing Vitamin A Status by Use of the Modified Relative Dose Response and Relative Dose Response Assays. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development. (1992).

29. Sommer A. Vitamin A Deficiency and Its Consequences: a Field Guide to Detection and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization (1995). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/40535 (accessed September 26, 2020).

30. Dunn JT, Crutchfield HE, Gutekunst R, Dunn AD. Methods for Measuring Iodine in Urine. Wageningen: International Council for Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (1993).

31. World Health Organization. Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring Their Elimination: A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization (2001). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241595827 (accessed September 26, 2020).

32. World Health Organization. WHO STEPS Surveillance Manual: The WHO STEPwise Approach to Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization (2005). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43376 (accessed September 29, 2020).

33. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 (accessed September 29, 2020).

34. Sy RG, Llanes EJB, Reganit PFM, Castillo-Carandang N, Punzalan FER, Sison OT, et al. Socio-demographic factors and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Filipinos from the LIFECARE cohort. J Atheroscler Thromb. (2014) 21:S9–17. doi: 10.5551/jat.21_sup.1–s9

35. Aguila DV, Gironella GMP, Capanzana MV. Food intake, nutritional and health status of Filipino adults according to occupations based on the 8th National Nutrition Survey 2013. Malays J Nutr. (2018) 24:333–48.

36. Duante CA, Canag JLQ, Patalen CF, Austria REG, Acuin CCS. Factors associated with overweight and obesity among adults 20.0 years and over: results from the 2013 National Nutrition Survey, Philippines. Philipp J Sci. (2019) 148:7–20.

37. Lipoeto NI, Geok Lin K, Angeles-Agdeppa I. Food consumption patterns and nutrition transition in South-East Asia. Public Health Nutr. (2012) 16:1637–43. doi: 10.1017/s1368980012004569

38. Steyn NP, Mchiza ZJ. Obesity and the nutrition transition in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2014) 1311:88–101. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12433

39. Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Vlismas K, Skoumas Y, Palliou K, et al. Dietary habits mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and CVD factors among healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Public Health Nutr. (2008) 11:1342–49. doi: 10.1017/s1368980008002978

40. Teachman J. Body weight, marital status, and changes in marital status. J Fam Issues. (2013) 37:74–96. doi: 10.1177/0192513x13508404

41. Jung YA, Kang LL, Kim HN, Park HK, Hwang HS, Park KY. Relationship between marital status and metabolic syndrome in Korean middle-aged women: the Sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2013–2014). Korean J Fam Med. (2018) 39:307–12. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.17.0020

42. Angeles-Agdeppa I, Sun Y, Denney L, Tanda KV, Octavio RAD, Carriquiry A, et al. Food sources, energy and nutrient intakes of adults: 2013 Philippines National Nutrition Survey. Nutr J. (2019) 18:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12937–019–0481–z

43. Northrop-Clewes CA, Thurnham DI. Monitoring micronutrients in cigarette smokers. Clin Chim Acta. (2007) 377:14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.08.028

44. Kolovou GD, Kolovou V, Mavrogeni S. Cigarette smoking/cessation and metabolic syndrome. Clin Lipidol. (2016) 11:6–14. doi: 10.1080/17584299.2016.1228285

45. Barve S, Chen SY, Kirpich I, Watson WH, McClain C. Development, prevention, and treatment of alcohol-induced organ injury: the role of nutrition. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. (2017) 38:289–302.

46. Lankester J, Zanetti D, Ingelsson E, Assimes TL. Alcohol use and cardiometabolic risk in UK Biobank: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS ONE. (2020) 16:e0255801. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.10.376400

47. Thompson PD, Crouse SF. Goodpaster B, Kelley D, Moyna N, Pescatello L. The acute versus the chronic response to exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2001) 33(supplement):S438–45. doi: 10.1097/00005768–200106001–00018

48. Fagard RH. Exercise characteristics and the blood pressure response to dynamic physical training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2001) 33(supplement):S484–92. doi: 10.1097/00005768–200106001–00012

Keywords: double burden of malnutrition, underweight, micronutrient deficiency, overweight, obesity, cardiometabolic risk factors, adults, Philippines

Citation: de Juras AR, Hsu W-C and Hu SC (2021) The Double Burden of Malnutrition at the Individual Level Among Adults: A Nationwide Survey in the Philippines. Front. Nutr. 8:760437. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.760437

Received: 18 August 2021; Accepted: 25 October 2021;

Published: 15 November 2021.

Edited by:

Christophe Matthys, KU Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Hélène Delisle, Université de Montréal, CanadaCopyright © 2021 de Juras, Hsu and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan C. Hu, c2h1aHVAbWFpbC5uY2t1LmVkdS50dw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.