- 1College of Animal Science and Technology, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China

- 2Hunan Co-Innovation Center of Animal Production Safety, Changsha, China

- 3Department of Food Science and Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima, Japan

Dietary protein sources have the potential to affect the colon microbiome of piglets that will subsequently have a large impact on metabolic capabilities and hindgut health. This study explored the effects of different protein sources on the growth performance, diarrhea rate, apparent ileal digestibility (AID) of crude protein (CP), colonic mucin chemotypes, colonic microbiome, and microbial metabolites of piglets. Twenty-four piglets were randomly divided into four groups that received isoenergetic and isonitrogenous diets containing either Palbio 50 RD (P50), Soyppt-50% (S50), concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein (CDCP), or fish meal (FM) as the sole protein source. The experimental diets did not affect the estimated daily gain (EDG), but P50 increased fecal score compared with S50 and CDCP. CDCP increased, but P50 reduced AID of CP in comparison to FM and S50. S50 and CDCP increased the amount of mixed neutral-acidic mucins relative to P50. Venn analysis identified unique OTUs in the P50 (13), CDCP (74), FM (39), and S50 (31) groups. The protein sources did not change the colonic bacterial richness or diversity. High Escherichia abundance in the P50 and FM, great abundant of Lactobacillus in the CDCP, and high Gemmiger abundance in the S50 were found. The CDCP tended to elevate valeric acid and branched chain fatty acid (BCFA) concentrations compared with the other diets. The P50 and FM groups had greater ammonia nitrogen and methylamine contents than the S50 and CDCP groups. There was a positive correlation between the Escherichia and ammonia nitrogen, the Lactobacillus and short chain fatty acid (SCFA), and a negative correlation between the Gemmige and BCFA. These findings suggested short-term feeding of different protein sources did not affect the piglets' growth, but P50 increased the diarrhea rate. Potential pathogenic bacteria and detrimental metabolites appeared in the colons of piglets fed P50 and FM, whereas, beneficial effects were conferred upon piglets fed CDCP and S50, thus indicating that available plant proteins (cotton seed, soy) added to the diets of piglets enhanced colon health by reducing protein fermentation.

Introduction

The weaning of piglets is often accompanied by low growth performance and a high risk of morbidity (mainly diarrhea rate) and death due to immature development of the gut and immune systems, which makes the piglets vulnerable to digestive disorders and highly susceptible to pathogenic bacteria (1–3). Indigestion causes excess undigested nutrients, mainly carbohydrates and protein, to flow into the hindgut where they are fermented by microbes. Carbohydrates fermentation is generally considered beneficial to the intestinal epithelium because it generates short chain fatty acids (SCFAs, acetate, propionate, and butyrate) (4, 5), but protein fermentation is considered to have adverse impacts on intestinal health because it can produce potentially toxic metabolites such as ammonia, biogenic amines, hydrogen sulfide, indols, and phenolic compounds, which are closely associated with the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and diarrhea (1, 5, 6). Excessive protein fermentation not only wastes protein sources, but also induces some enteric diseases. The inclusion of high-quality of protein (milk by-products, animal proteins, processed proteins, etc.) (1, 2), the reduction of dietary protein intake or protein level (2, 3, 7), the addition of dietary fiber (8–10), and the use of various feed additives (1, 8) are commonly seen in swine production. These nutritional strategies can effectively reduce the outflow of undigested protein into the hindgut and decrease substrates for protein fermentation.

The colonic microbiota plays an important role in digestive physiology and makes a significant contribution to homeostasis (11, 12). Colonic bacteria can catabolize mostly amino acids via the abundant proteases and peptidases produced during fermentation (13). The ileal digestibility of protein and amino acids varies amongst protein source and determines the outflow of substrates into the hindgut for protein fermentation and specific biomarkers (2, 8). Therefore, identification of the biomarkers of various protein sources during fermentation is useful for the selection of suitable protein ingredients for piglets' diets and to provide a reference for dietary modulation to maintain piglets' gut health.

Although enzyme-treated soybean meal (14), cottonseed protein (15), dried porcine solubles (16, 17), and fish meal (18) are widely used in piglets' diets, few studies have evaluated the microbial mechanism of these protein sources on protein fermentation in the hindgut. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of P50, S50, CDCP, and FM on the growth performance, AID of CP, colonic mucin chemotypes, and the composition and metabolites of colonic microbiota in piglets. The results provide a reference for protein sources selection in piglet diets based on hindgut micro-ecosystem regulation.

Materials and Methods

The Hunan Agricultural University Animal Ethics Committee (Changsha, China) reviewed and approved all experimental protocols. The four protein sources used in the study were Palbio 50 RD (P50, a dried porcine solubles; Bioiberica, S.A, Spain), Soyppt-50% (S50, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; Jiangsu Peptid Biological Co., Ltd, Jiangsu, China), Concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein (CDCP, a novel processed cottonseed meal; Xinrui Biotech, Hunan, China), and fish meal (FM, steam dried fish meal; Tecnológica de Alimentos S.A., Peru).

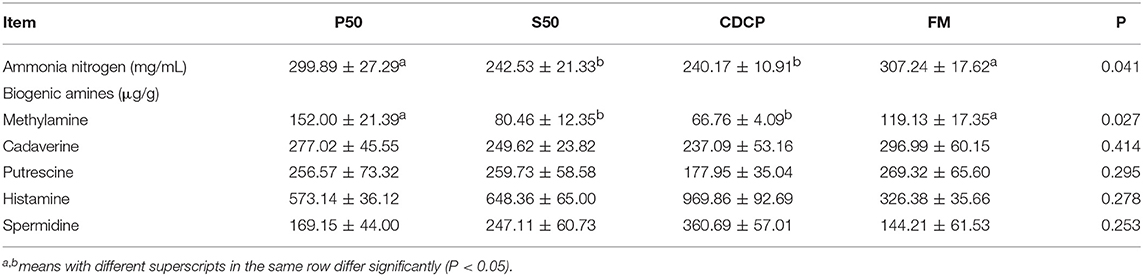

Animal, Diets, and Experimental Design

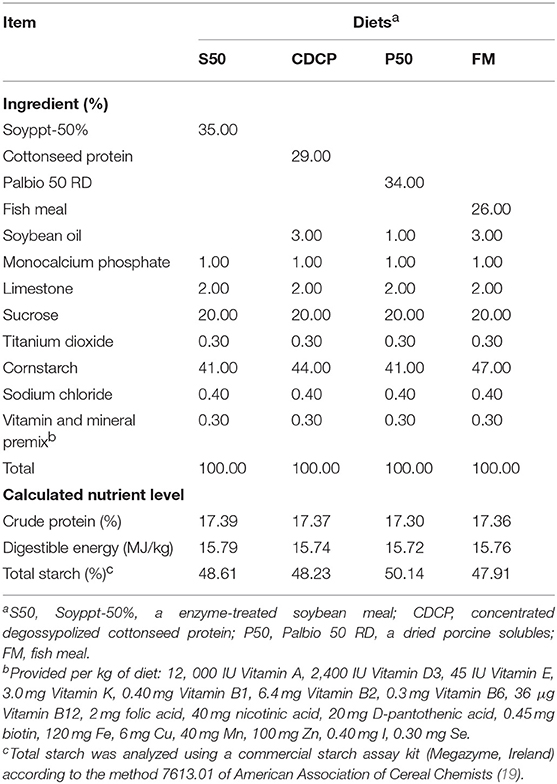

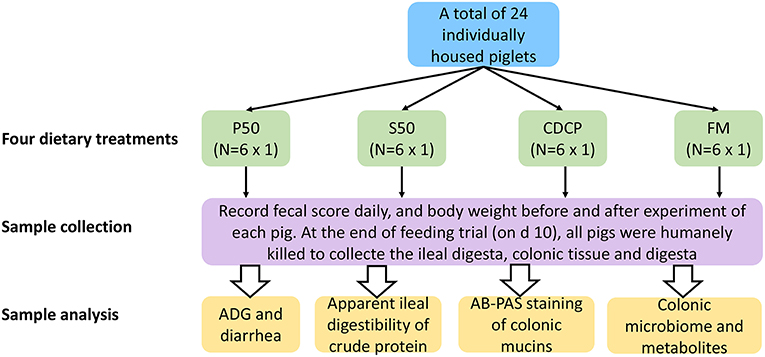

Twenty-four barrows (Landrace × Yorkshire; initial BW = 12.61 ± 1.45 kg) were individually housed in stainless steel metabolism chambers (0.7 × 1.4 m) equipped with a nipple drinker, a feeder, and a fully slatted plastic floor. The piglets were randomly allotted to 1 of 4 diets with 6 piglets in each group (Figure 1). Four cornstarch-based diets were formulated with P50, S50, CDCP, or fish meal as the sole protein (Table 1). Piglets were fed the experimental diets for 9 days, and each piglet was fed a daily level of 5% of the average initial BW of 24 piglets. Feed was provided three times a day, with the daily allowances averaged over the three meals. All piglets had ad libitum access to water. On the day 10, piglets were humanly slaughtered to collect the ileal and colonic digesta, and colon tissue.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the experimental design. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

Sample Collection and Preparation

Body weight per piglet was measured at the beginning and conclusion of the 9-day experimental period to calculate the estimated daily gain (EDG). The fecal score for each piglet was recorded daily, according to the method introduced by Hu et al. (20) (hard feces = 1; slightly soft = 2; soft and partially formed feces = 3; loose, semi-liquid = 4; watery feces = 5). After the feeding trial, all piglets were anesthetized with serazine hydrochloride (Jilin Huamu Animal Health Product Co., Ltd., Changchun, China) at a dosage of 0.5 ml/kg BW by intramuscular injection and humanely euthanatized. The digesta in ileal segment 15 cm prior to ileocecal junction was collected and lyophilized for the determination of apparent ileal digestibility (AID) of crude protein (CP). The digesta in the colonic lumen was collected and stored at −80°C for microbiology and metabolites analyses. The colonic tissue was fixed in Bouin's solution for Histomorphological analysis.

Measurement of AID of CP

The methods for determining CP and titanium (Ti) contents in diets and lyophilized ileal digesta were detailedly described by Li et al. (21). The AID of CP in diets was calculated as following: AID (%) = [1–(CPi × Tid)/(CPd/Tii)] × 100, where CPi and Tii are the contents of CP and TiO2, respectively, in the ileal digesta and CPd and Tid represent the concentrations of CP and TiO2, respectively, in diets.

AB-PAS Staining of Mucins in Colonic Tissue

To characterize the neutral and acidic mucins in colonic goblet cells, an Alcian blue (pH 2.5)-periodic acid Schiff (AB-PAS) staining procedure, based on the method of Liu et al. (22) and Henwood (23) was conducted. Briefly, the colon tissue samples were fixed in Bouin's solution and then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin blocks. A 5 μm section was sliced, deparaffinized, hydrated, and then stained with AB-PAS. The neutral and acidic mucins in goblet cells were stained in magenta and blue colors, respectively. The results were visualized by computer-assisted microscopy (DT2000, Nanjing dongtu digital technology co. LTD, China) and image-analysis software (Motic Images Plus 2.0, Dongguan, China).

Analysis of SCFA, BCFA, and Nitrogen Metabolites

Approximately 1.0 g of colon digesta was diluted with 10 mL of ultra-pure water, vortexed for 2 min, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min and filtered (0.45 μm) to collect the filtrate. A 2-mL portion of the filtrate was transferred to a 10-ml centrifuge tube, and 0.2 mL of 50% sulfuric acid and 2 mL of diethyl ether were added successively. The solution was vortexed for 2 min, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min and placed at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was analyzed for SCFA (acetic acid, propionate acid and butyric acid) and BCFA (isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid) using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatographer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA) equipped with an HP-FFAP elastic quartz capillary vessel column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The carrier gas was high-purity nitrogen (99.999%) with a constant flow rate of 2.0 mL/min. The column temperature procedure was from 100°C for 1 min then increasing by 5°C/min to reach 150°C for 5 min. The inlet and detector (FID) temperatures were 270°C and 280°C, respectively. The inlet volume was 2.0 μL, as measured by splitless injection.

The contents of ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) in samples were determined using Nessler's reagent spectrophotometry as described by Chen et al. (24). Briefly, 0.5 g of colonic digesta was mixed with 5 mL of ammonia-free water and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to collect the supernatants. A 1-mL portion of supernatants was transferred to a 50-mL aseptic tube filled with 19 mL of ammonia-free water and 1 mL of potassium sodium tartrate, after which 1.5 mL of Nessler's reagent was added and the mixture was left to stand for 10 min. The OD value of the mixture was measured at 420 nm against ammonia-free water on a multi-scan spectrum microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific (China), Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China).

The concentrations of biogenic amines in the colonic digesta, mainly methylamine, cadaverine, putrescine, histamine, and spermidine, were analyzed with high- performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) according to the method introduced by Fan et al. (25). In short, 0.2 g of colonic digesta was weighed into a 2-mL tube, and 1 mL of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added and homogenized for 10 min. Afterward, the mixture was centrifuged at 3,600 × g for 10 min at 4°C to collect the supernatants. An equal volume of n-hexane was mixed with the supernatants and vortexed for 5 min, after which the organic phase was removed and the aqueous phase was re-extracted in the same way. The extracts were transferred into a 50-mL tube, and 20 mL of internal standard, 1.5 mL of saturated sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), 1 mL of dansyl chloride, and 1 mL of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were then added successively. The mixture was heated at 60°C for 45 min with occasional mild shaking. Next, 100 μL of termination solution (i.e., ammonia) was added to the mixture, and the solution was maintained 40°C in a water bath to vaporize the acetone by blow-drying with N2. Finally, the sample was extracted twice with 3 mL of diethyl ether, and the collected extracts were blow-dried with N2, and the residue was then re-dissolved in acetonitrile solution for HPLC analysis. An ammonium acetate-acetonitrile gradient elution program was used on an Agilent 1200 equipped with a variable wavelength detector (VWD) and a reversed–phase ZORBAX 80 A Extend–C18 (4.6 mm × 250 mm; 5 μm) column (Agilent Technologies, USA). The flow rate, temperature and wavelength were set at 1.0 mL/min, 30°C and 260 nm, respectively.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Twenty colonic digesta samples from 4 dietary groups (5 per group) were randomly selected for 16S rRNA sequencing analysis. The total genomic DNA of each sample was extracted by using the TIANamp Stool DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of extracted DNAs were measured using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. Nineteen acceptable DNA samples (one low-quality DNA sample from the FM group was discarded) were sent to BGI (Wuhan, China) for 16S rRNA sequencing.

The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with the barcoded universal primers (341F-806R). All the PCR reactions were performed in 30-μL reaction volumes containing 1.0 μL of each primer, 1.0 μL of DNA template, 15 μL of Phusion® PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs, USA), and 12 μL of sterile water. After the PCR amplification ended under the set cycle condition, agarose gel electrophoresis and a GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used to determine, and extract and purify the PCR products. Sequencing libraries were prepared using an NEB Next® UltraTM DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, USA) according to the manufacturer's methods. Sequencing was conducted on the Illumina HiSeq platform by HiSeq2500 PE250 (Illumina, USA), and 250 bp paired-end reads were generated.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Paired-end reads from the sequencing data were screened and processed by FLASH (v1.2.11) (26, 27) and QIIME (v1.8.0) (28). Chimeric sequences produced by the PCR amplification were removed by UCHIME (v4.2.40) (29). The assembled tags were clustered as OTU via USEARCH (V7.0.1090) (30). Sequences with 97% similarity were assigned to the same operational taxonomic units (OTUs), selected by UPARSE. Meanwhile, we picked a representative sequence for each OTUs and used the RDP (v2.2) classification to assign taxonomic data to each representative sequence, with a confidence threshold of 0.6. Taxonomy classifications were set against Greengene (V201305) (31) and RDP (Release9 201203) (32). An OTU table was further generated to record the abundance of each OTU in each sample, and a profiling histogram was made using R software (v3.1.1) to represent the relative abundance of taxonomic groups from phylum to species. A Venn diagram was generated to visualize the occurrence of shared and unique OTUs among groups1 Alpha diversity indices based on the OTUs in all samples were analyzed with mothur (v1.31.2) according to the calculation formula of each index2 and displayed with Prism software (v7.0). Beta diversity was evaluated using the Unifrac metric, and the UPGMA tree based on the unweighted UniFrac distances between the OTUs was displayed by QIIME (v1.80). Principal component analysis (PCA) was also conducted with R software (v3.1.1) based on the OTUs among samples from different groups. A heatmap was created using R software (v3.1.1) after performing the logarithmic transformation of relative abundance in each sample. LefSe analysis was conducted based on the relative abundance of annotated taxonomic composition to identify biomarkers for microbial communities from phylum to genus3.

Statistical Analysis

EDG, fecal score, and colonic SCFAs, ammonia nitrogen, biogenic amines and alpha diversity indexes were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA using the GLM procedure of SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with individual piglet as an experimental unit. Unweighted Unifrac distances were compared based on approximately-maximum-likelihood to construce UPGMA trees. The Kruskal test was used for post hoc comparison of taxonomy. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered as significant difference, while 0.05 < P < 0.10 as a tendency. Correction between metabolites and microbiota in colonic digesta was done with Spearman's rank- order correlation test in R software (v3.1.1).

Results

Growth Performance, Fecal Scores, and AID of CP

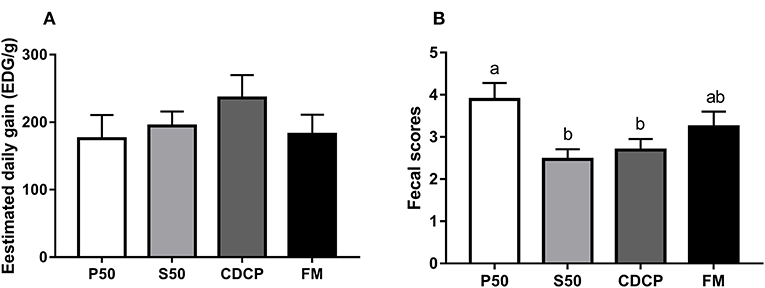

No differences in EDG were observed among the four dietary groups (P = 0.173) (Figure 2). However, the piglets in the P50 group elevated fecal scores compared with those in the S50 and CDCP groups (P = 0.039). Protein source significantly affected the AID of CP in diets (P < 0.01) (published in our previous paper). CDCP had the highest AID of CP and P50 had the lowest AID of CP. No differences in AID of CP were found between S50 and FM (P > 0.05).

Figure 2. The estimated daily gain (EDG, A) and fecal score (B) of piglets fed different dietary protein sources. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, an enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal. Different letters above the error bar mean significant difference (P < 0.05).

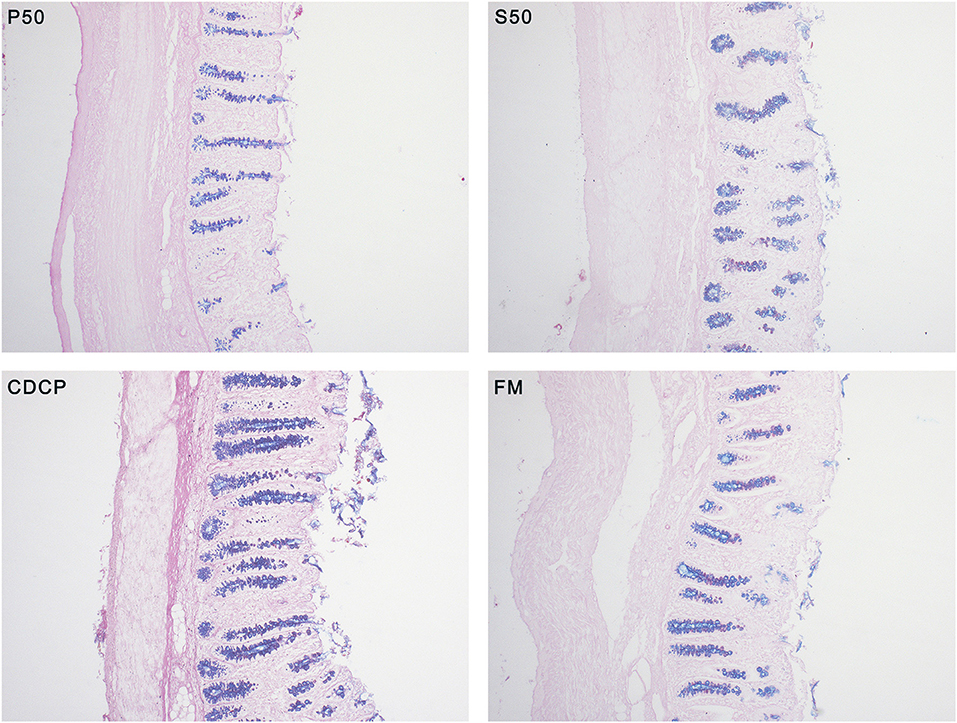

Characterization of Mucin Chemotypes

With AB-PAS staining, the amount of mixed neutral-acidic mucins in colon tissue of piglets fed S50 and CDCP diets were increased (P < 0.05) compared with those fed P50 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Alcian blue (pH 2.5)-periodic acid Schiff (AB-PAS) stained section (100×) in colon tissues. Neutral mucins are marked in magenta, while acidic mucins in blue. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

Microbial Community Structure in Colonic Digesta

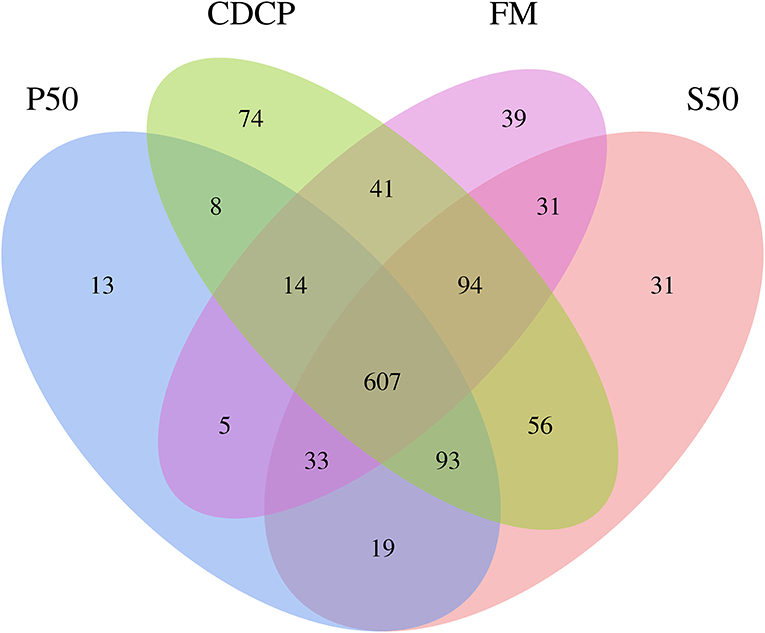

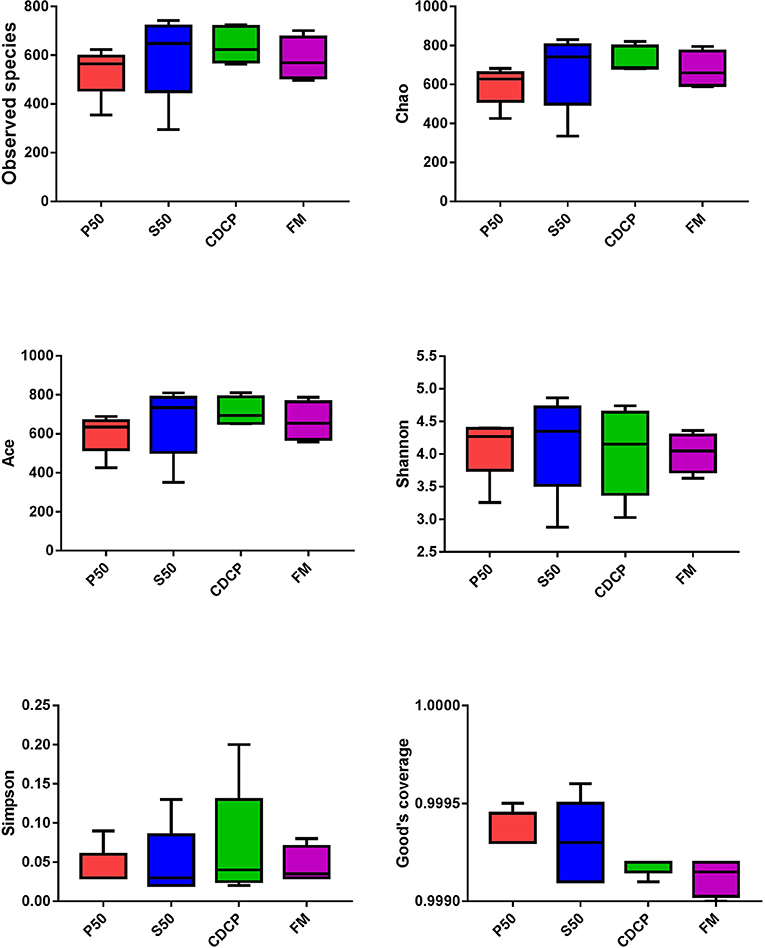

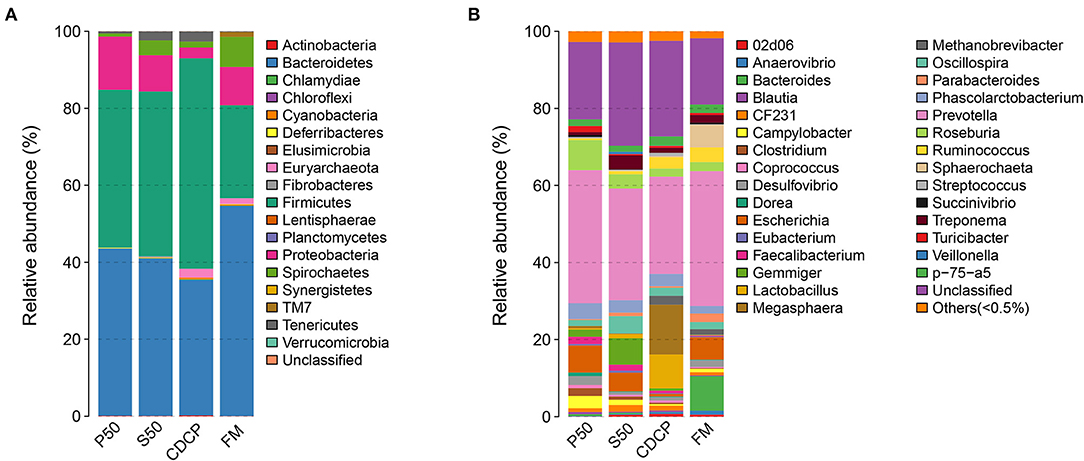

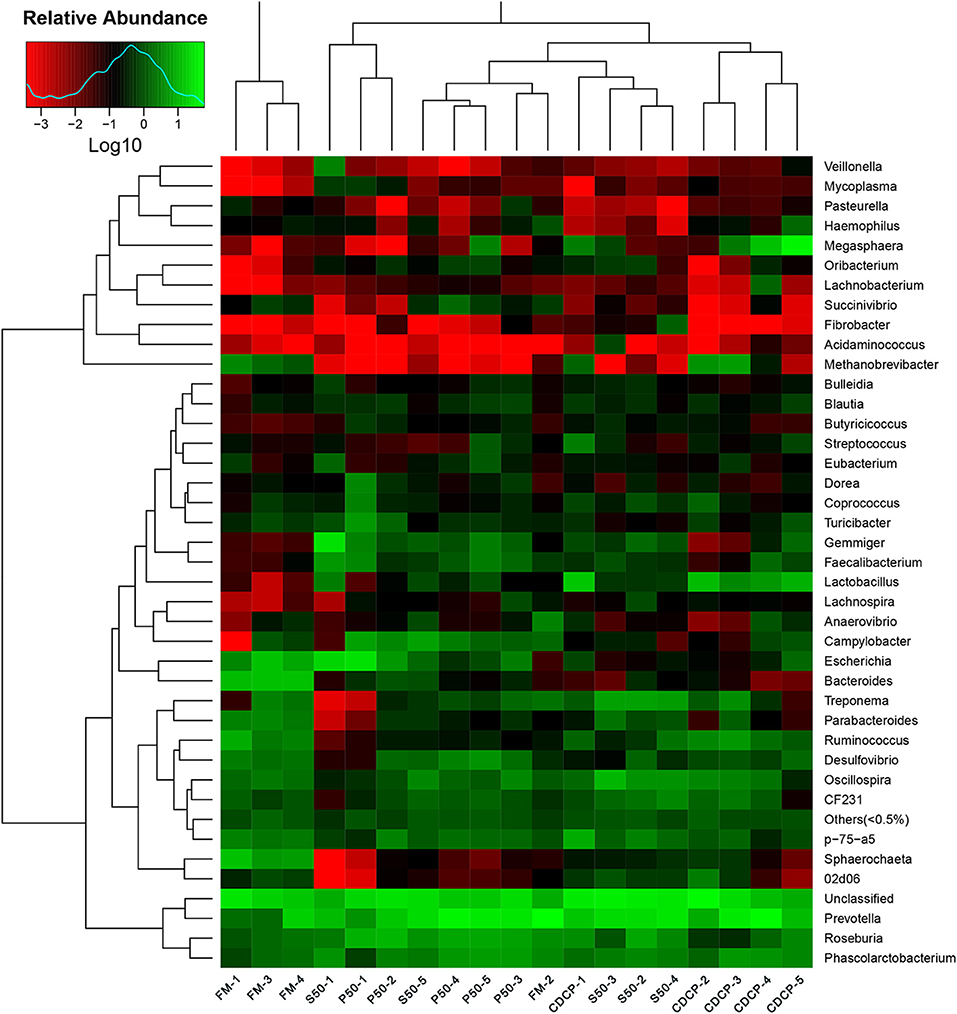

The Venn analysis identified 13, 74, 39, and 31 unique OTUs in the P50, CDCP, FM, and S50 dietary groups, respectively (Figure 4). Dietary protein sources did not affect the alpha diversity indices (Figure 5). Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Spirochaetes were the four most abundant phyla (Figure 6A). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios in CDCP, S50, P50, and FM were 1.54, 1.03, 0.95, and 0.45, respectively. FM had a lower abundance of Firmicutes (P = 0.025), but a greater abundance of Spirochaetes (P = 0.040) and TM7 (P = 0.007) than the other three groups, S50 and CDCP had increased Tenericutes abundance compared with P50 and FM (P = 0.012) (Supplementary Table S2). Down to the genus level, P50 and FM had high abundances of Escherichia (P = 0.029) and Clostridium (P = 0.041), whereas, CDCP had abundances of Lactobacillus (P = 0.002) and Megasphaera (P = 0.033) and S50 had a high abundances of Gemmiger (P = 0.018) (Figure 6B).

Figure 4. Venn pictures exhibit shared and the unique OTUS among dietary treatments. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

Figure 5. Difference analysis of alpha diversity index among different dietary treatments. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

Figure 6. Relative abundance of colonic bacteria, at phylum (A) and genus (B) level, in piglets fed diets containing P50, S50, CDCP, and FM. Representative sequences for each OUT were used to annotate taxonomic information. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

The heatmap results showed that Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, and Roseburia were the most abundant genera within the four dietary groups (Figure 7). CDCP had greater Lactobacillus abundance than the other three dietary groups, whilst P50 and FM had increased Escherichia abundance compared with CDCP and S50.

Figure 7. Relative abundance of each taxonomic genus in different dietary treatments. The rows show the top 50 genera in each sample and the color scale illustrates the comparison of each genera among the samples. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

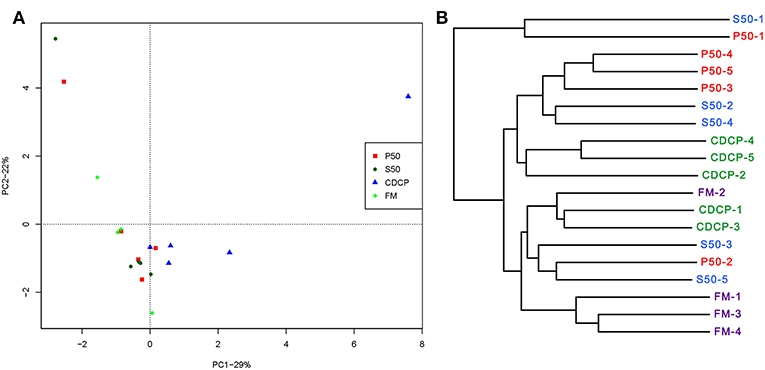

PCA, a multivariate analysis, was used to compare the overall composition of the microbiota in the colonic samples from various dietary groups (Figure 8A). The first two components accounted for 52% of the variation. PC1 mainly represented the diet-induced variations, whilst PC2 explained intra-group variations in microbial structure. Greater variations were seen in P50 and FM than in CDCP and S50, whilst P50, S50, and CDCP had similar microbial communities. The UPGMA tree analysis (Figure 8B) revealed that remarked differences in the structure of colonic microbiota among various dietary groups, suggesting that the protein sources had a notable impact on colonic microbial communities.

Figure 8. Comparison of colonic microbial structures within piglets fed different dietary protein sources. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) based on OTUs among samples of different groups, each point represents one sample. (B) UPGMA tree, all revealing significant differences among groups based on Unweighted UniFrac distances of OTUs community. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

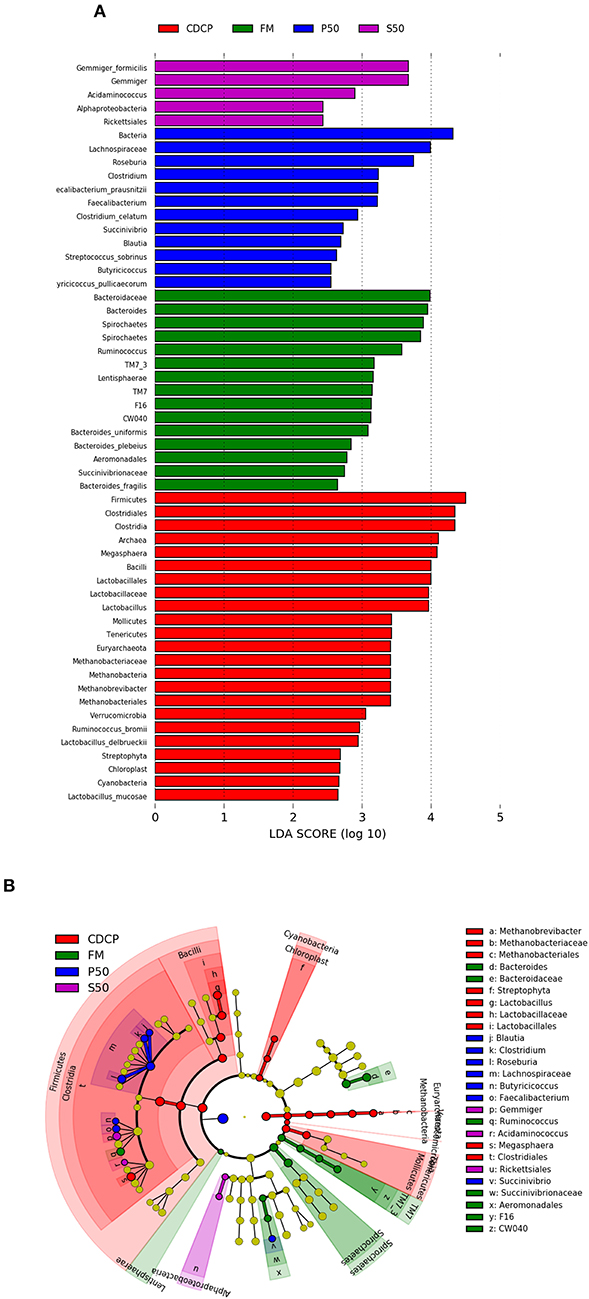

LEfSe analysis showed 55 different OTUs among the 4 dietary protein groups, and the abundance of 5 OTUs was low in S50, with 12 in P50, 15 in FM, and 23 in CDCP (Figure 9A). There was a high abundance of Lactobacillus in CDCP, Bacteroides in FM, Clostridium in P50, and Gemmiger in S50, respectively (Figure 9B).

Figure 9. LefSE analysis of colonic microbiota among different dietary groups. (A) LDA scores are calculated for characteristics at the OUT level. (B) Cladogram shows the relative abundance of OTUs from the phylum to genus level, the node size represented the average relative abundance of the taxon, the yellow node indicated no difference among groups, but the other color nodes suggested the significant difference, the letters identified the taxon name with notable difference among groups. P50, Palbio 50 RD, a dried porcine solubles; S50, Soyppt-50%, a enzyme-treated soybean meal; CDCP, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein; FM, fish meal.

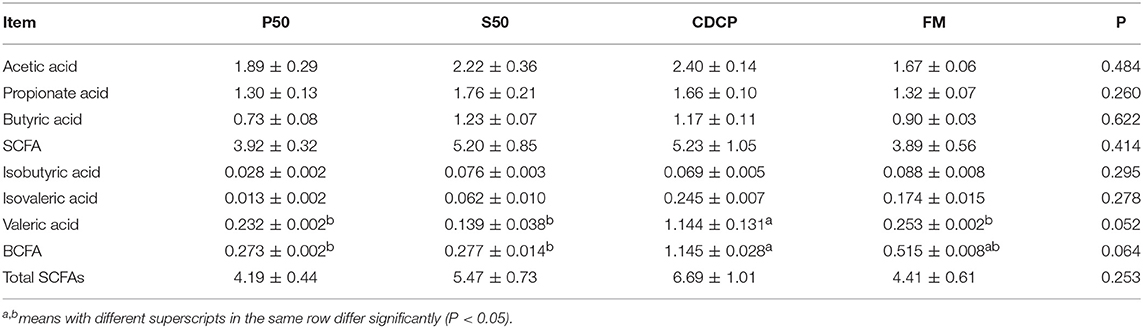

Fermentation Metabolites of Colonic Digesta

CDCP showed a trend of elevated valeric acid (P = 0.052) and BCFA (P = 0.064) concentrations (Table 2). P50 and FM had greater ammonia nitrogen and methylamine contents than S50 and CDCP (P = 0.041) (Table 3).

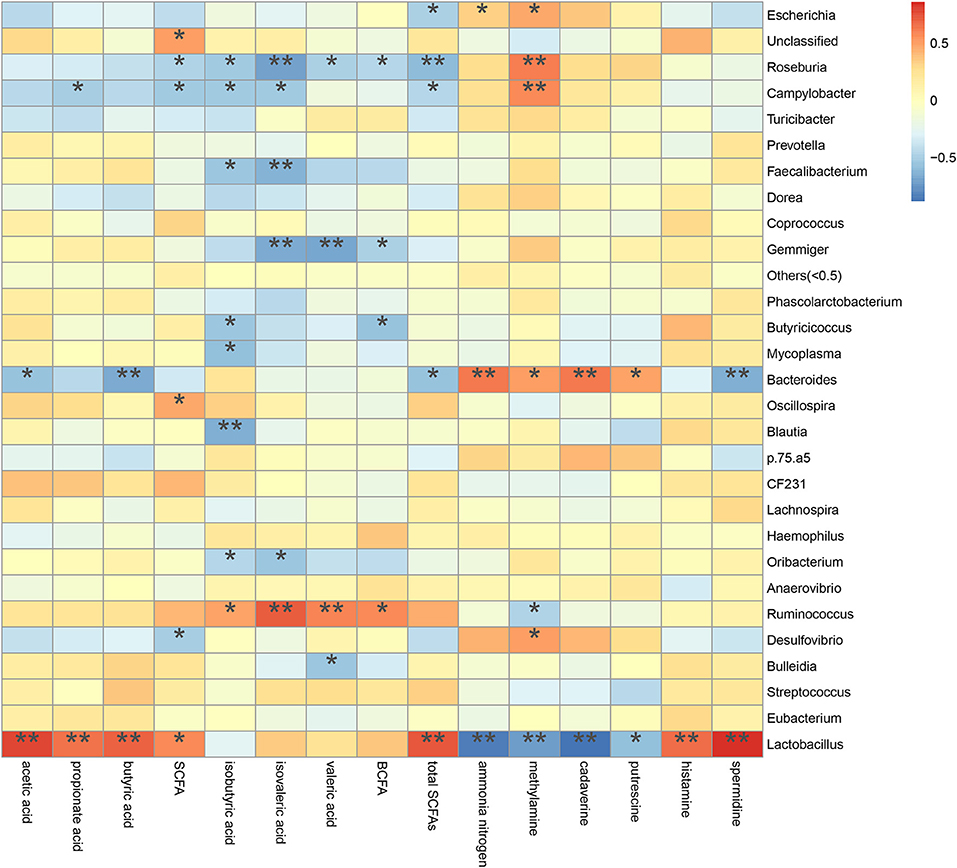

Correction Between Metabolites and Microbiota in Colonic Digesta

A spearman's rank correlation analysis was done to infer taxa associated with metabolic potentials (Figure 10). We found that the increased Escherichia abundance in FM and P50 group was positively correlated with ammonia nitrogen (P < 0.05) and methylamine (P < 0.05), but negatively corrected with total SCFAs (P < 0.05). Lactobacillus, contained an increased abundance in CDCP group, was positively correlated with acetic acid (P < 0.01), propionate acid (P < 0.01), butyric acid (P < 0.01), SCFA (P < 0.05), total SCFAs (P < 0.01), histamine (P < 0.01), and spermidine (P < 0.01), but negatively corrected with ammonia nitrogen (P < 0.01), methylamine (P < 0.01), cadaverine (P < 0.01), and putrescine (P < 0.05). Gemmiger, had an increased abundance in S50 group, was negatively corrected with isovaleric acid (P < 0.01), valeric acid (P < 0.01), and BCFA (P < 0.05).

Figure 10. Correlation between metabolite contents and relative microbiota abundance in colonic digesta from piglets. Correlation is indicated by a color gradient from blue to red based on Spearman's correlation coefficients (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Discussion

Dietary protein is mainly digested into peptides and amino acids in the foregut via the action of proteases (13, 25). The digestion and absorption of protein is closely associated with the increased lean muscle mass (33). The weight gain of piglets is primary lean muscle mass due to their rapid growth and quick protein turnover (34, 35). In our study, equal amounts of feed with similar DE and CP were fed to each piglet daily to ensure the similar dietary protein and energy intakes. This helps to explain, along with the short experimental period (9 days), why the EDG of the piglets showed no difference among the dietary groups. However, the P50 group increased the diarrhea rate, perhaps because of the high salt content and poor carriers added to co-dried P50, which is the porcine mucosa hydrolysate after heparin extraction and is usually sprayed into a soybean meal carrier (16, 17, 36). Additionally, the reduced AID of CP in the P50 group in our previous study (21) could also explain the increased diarrhea rate, because more undigested protein flow into the hindgut for protein fermentation.

The porcine gastrointestinal tract harbors highly diverse and dynamic microbial communities that play a vital role in maintenance of intestinal health, which contributes to nutrient utilization and modulation of the immune system (5, 37). Diet composition, especially carbohydrates and protein, reflects the substrates available for the intestinal microbiota, which affects their composition and metabolic activity (38). Researchers and the feed industry have paid increasing attention to dietary protein manipulation of the intestinal microbiota in piglets (7, 15, 39, 40). Our experiment determined the colonic microbiome of piglets fed diets containing either P50, S50, CDCP, or FM as sole protein source via 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing. On average, 164,709 effective tags were achieved for each sample with a high Good's coverage (>99.90%) (Supplementary Table S1). Meanwhile, protein sources did not affect the alpha diversity indices, suggesting that the ecological diversity of the colonic microbiota was quite similar among the samples. The alpha diversity reflects the species diversity in a single sample, including species richness indices (observed species, chao, and ace), species diversity (Shannon, Simpson, and Good's coverage) (31, 41). Our findings concurred with those of Cao et al. (15), who found no change in alpha diversity of piglets fed diets containing soybean meal, cottonseed meal, SBM and CSM or fish meal. However, Venn analysis identified 13, 74, 39, and 31 unique OTUs in the P50, CDCP, FM, and S50 groups, respectively, indicating that specific bacteria appeared in piglets fed different diets.

At the phylum level, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Spirochaetes were the major phyla in colonic digesta (Figure 6A), similar to the findings of a study by Cao et al. (15). The value for Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in CDCP, S50, P50, and FM was gradually reduced (Figure 7). This index is positively correlated with obesity (42), and interestingly, no differences in EDG were found among the four groups (Figure 2A). Down to the genus level, there were high abundances of Escherichia and Clostridium in P50 and FM, of Lactobacillus and Megasphaera in CDCP, and of Gemmiger in S50 (Figure 6B). These observations were also confirmed by heatmap (Figure 7) and LEfSe analysis (Figure 9), which can identify unique biomarkers for high dimensional gut bacteria composition (43). Prevotella is a dominant genus in all dietary groups (Figure 7), and the bacteria in this genus mainly used carbohydrates as substrates (44); thus, our finding might be due to the similar total starch content among diets (Table 1). Bacteroides, Coliform bacteria, and Clostridium are closely related to protein fermentation and often increase the risk of diarrhea (2). The high abundance of Escherichia and Clostridium in P50 and FM can explain the increased fecal scores. The finding was similar to that of Heo et al. (45), who reported that the occurrence of pathogenic diarrhea in piglets was mainly due to the release of endotoxin by Escherichia coli, which adhered to gut epithelial cells. PCA and UPGMA tree revealed greater variations were seen in P50 and FM than in CDCP and S50, suggesting that the intestinal microbiota responds differently to animal protein.

SCFA (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) and BCFA (isobutyrate, isovalerate, and valerate) are generated from fermentation of carbohydrates and protein in the colon (1). Both carbohydrates and protein fermentation produce SCFA, whilst BCFA are coming from deamination of valine, leucine, and isoleucine (25). In piglets, considerable amounts of carbohydrates are fermented in the proximal colon, but protein fermentation takes place more distally, especially when there is a shortage of available fermentable carbohydrates (1). Our results (Table 2) showed that dietary protein did not affect SCFAs profiles, but the CDCP group showed a tendency of increased valeric acid and BCFA contents. Some reports have indicated that BCFA play a role in maintaining intestinal cell integrity (46, 47) and suggested that CDCP might ameliorate the colon health. This was consistent with the study by Cao et al. (15), who found a beneficial effect of cottonseed meal on the gut of piglets. However, Rist et al. (1) suggested that BCFA might be an indicators of the extent of protein fermentation and exerted detrimental effects upon the host.

The decarboxylation and deamination of amino acids generate bioamines and ammonia, respectively. Ammonia, amines, phenols, and indoles are considered as potentially toxic products, which may interfere with epithelial cell turnover and inhibit pig growth (13, 24). In this study, S50 and CDCP had lower ammonia nitrogen and methylamine contents than P50 and FM (Table 3), possibly because plant protein (S50 and CDCP) contains dietary fiber, which help to reduce protein fermentation. Many researchers have suggested that the addition of dietary fiber to piglets' diets could reduced protein fermentation and diarrhea rate (6, 8, 9, 37, 48). The finding that CDCP and S50 decreased Escherichia abundance compared with P50 and FM (Figure 7) could also explain the reduced nitrogen metabolites. Additionally, the increased Escherichia abundance in FM and P50 was positively correlated with ammonia nitrogen and methylamine, but negatively corrected with total SCFAs (Figure 10), which could also provide an evidence for the beneficial effect of CDCP and S50 to colon.

Mucin layer spreads over the surface of mucosa and safeguards the intestine and its structural integrity (22). Mucins is broadly categorized into neutral and acidic chemotypes. In our study, we distinguished and detected the two types of mucins and we found that CDCP and S50 increased the amount of mixed neutral-acidic mucins in colon, which might ascribe the reduced protein fermentation in colon of piglets fed plant protein sources (Figure 3).

Conclusion

Protein intake from 4 different diets (P50, S50, CDCP, and FM) had similar effects on piglet growth, but P50 increased diarrhea rate during short-term feeding. CDCP and S50 reduced the protein flows into hindgut and increased the amount of mixed neutral-acidic mucins in colon. Potential pathogenic bacteria (Escherichia) and detrimental metabolites (ammonia) were found in the colons of piglets fed P50 and FM, whilst beneficial effects (Lactobacillus and BCFA) were seen in pigs fed CDCP. These findings indicate that the addition of available plant protein such as CDCP to the diet of piglets enhances colon health by reducing protein fermentation.

Data Availability

The datasets for this manuscript are not publicly available because we have not uploaded the datasets to the NCBI due to some secret data, temporarily. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGlydWkxODEwMDBAMTYzLmNvbQ==.

Ethics Statement

The Hunan Agricultural University Animal Ethics Committee (Changsha, China) reviewed and approved all experimental protocols.

Author Contributions

RL, XH, and D-XH design the experiment and revised the manuscript. RL, ZS, and GH conducted the experiments. RL, ZS, ZF, and XH offered the experimental reagents and materials. RL analyzed the data and finished the manuscript. RL, LC, GH, ZS, and D-XH prepared the figures and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National key R & D Program of China (2017YFD0500506, 2016YFD0501200), the Double first-class construction project of Hunan Agricultural University (SYL201802015, SYL201802009) and the Hunan postgraduate research and innovation project (CX2018B399).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the workers in BGI (Wuhan, China) for their experiment on 16s rDNA high-throughput sequencing, and thank bioinformatics trainers in Personalbio (Shanghai, China) for their help in data preparation and analysis. The authors are also grateful to the staff at Department of Animal Nutrition and Feed Science of Hunan Agricultural University for their assistance in conducting the experiment.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2019.00151/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^http://www.ehbio.com/ImageGP/index.php/Home/Index/VennDiagram.html

References

1. Rist VTS, Weiss E, Eklund M, Mosenthin R. Impact of dietary protein on microbiota composition and activity in the gastrointestinal tract of piglets in relation to gut health: a review. Animal. (2013) 7:1067–78. doi: 10.1017/S1751731113000062

2. Rist VTS, Weiss E, Sauer N, Mosenthin R, Eklund M. Effect of dietary protein supply originating from soybean meal orcasein on the intestinal microbiota of piglets. Anaerobe. (2014) 25:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.10.003

3. Almeida VV, Nuñez AJC, Schinckel AP, Alvarenga PVA, Castelini FR, Silva-Guillen YV, et al. Interactive effect of dietary protein and dried citrus pulp levels on growth performance, small intestinal morphology, and hindgut fermentation of weanling pigs. J Anim Sci. (2017) 95:257–69. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.0498

4. Wong JM, De SR, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. (2006) 40:235–43. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00015

5. Pieper R, Villodre Tudela C, Taciak M, Bindelle J, Perez JF, Zentek J. Health relevance of intestinal protein fermentation in young pigs. Anim Health Res Rev. (2016) 17:137–47. doi: 10.1017/S1466252316000141

6. Molist F, van Oostrum M, Pérez JF, Mateos GG, Nyachoti CM, van der Aar PJ. Relevance of functional properties of dietary fibre in diets for weanling pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2014) 189:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2013.12.013

7. Zhou L, Fang L, Sun Y, Su Y, Zhu W. Effects of the dietary protein level on the microbial composition and metabolomic profile in the hindgut of the pig. Anaerobe. (2016) 38:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.12.009

8. Pieper R, Kröger S, Richter JF, Wang J, Martin L, Bindelle J, et al. fermentable fiber ameliorates fermentable protein-induced changes in microbial ecology, but not the mucosal response, in the colon of piglets. J Nutr. (2012) 142:661–7. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.156190

9. Pieper R, Neumann K, Kroger S, Richter JF, Wang J, Martin L, et al. Influence of fermentable carbohydrates or protein on large intestinal and urinary metabolomic profiles in piglets. J Anim Sci. (2012) 90:34–6. doi: 10.2527/jas.53918

10. Sun Y, Su Y, Zhu W. Microbiome-metabolome responses in the cecum and colon of pig to a high resistant starch diet. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:779. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00779

11. Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Bacteria, colonic fermentation, and gastrointestinal health. J Aoac Int. (2012) 95:50–60. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.SGE_Macfarlane

12. Tan Z, Wang Y, Yang T, Ao H, Chen S, Xing K, et al. Differences in gut microbiota composition in finishing Landrace pigs with low and high feed conversion ratios. Anton Van Leeuw. (2018) 111:1673–85. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1057-1

13. Fan P, Li L, Rezaei A, Eslamfam S, Che D, Ma X. Metabolites of dietary protein and peptides by intestinal microbes and their impacts on gut. Curr Protein Pept Sci. (2015) 16:646–54. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150630133657

14. Jeong JS, Kim IH. Comparative efficacy of up to 50% partial fish meal replacement with fermented soybean meal or enzymatically prepared soybean meal on growth performance, nutrient digestibility and fecal microflora in weaned pigs. Anim Sci J. (2015) 86:624–33. doi: 10.1111/asj.12335

15. Cao K, Zhang H, Han H, Song Y, Bai X, Sun H. Effect of dietary protein sources on the small intestine microbiome of weaned piglets based on high-throughput sequencing. Lett Appl Microbiol. (2016) 62:392–8. doi: 10.1111/lam.12559

16. Mateos GG, Mohiti-Asli M, Borda E, Mirzaie S, Frikha M. Effect of inclusion of porcine mucosa hydrolysate in diets varying in lysine content on growth performance and ileal histomorphology of broilers. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2014) 187:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2013.09.013

17. Myers AJ, Goodband RD, Tokach MD, Dritz SS, DeRouchey JM, Nelssen JL. The effects of porcine intestinal mucosa protein sources on nursery pig growth performance. J Anim Sci. (2014) 92:783–92. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6551

18. Kim SW, Easter RA. Nutritional value of fish meals in the diet for young pigs. J Anim Sci. (2001) 79:1829–39. doi: 10.2527/2001.7971829x

19. American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods of Analysis. American Association of Cereal Chemists, St. Paul, MN (1976).

20. Hu C, Gu L, Luan Z, Song J, Zhu K. Effects of montmorillonite-zinc oxide hybrid on performance, diarrhea, intestinal permeability and morphology of weanling pigs. Anim Feed Sci Tech. (2012) 177:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2012.07.028

21. Li R, Hou G, Song Z, Zhao J, Fan Z, Hou D-X, et al. Nutritional value of enzyme-treated soybean meal, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein, dried porcine solubles and fish meal for 10- to−20 kg pigs. Anim Feed Sci Tech. (2019) 252:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.04.002

22. Liu P, Pieper R, Rieger J, Vahjen W, Davin R, Plendl J, et al. Effect of dietary zinc oxide on morphological characteristics, mucin composition and gene expression in the colon of weaned piglets. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e91091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091091

23. Henwood AF. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of mucins of the gastrointestinal tract. J Histotech. (2017) 40:21–4. doi: 10.1080/01478885.2017.1264556

24. Chen J, Kang B, Jiang Q, Han M, Zhao Y, Long L, et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate in low-protein diets for growing pigs: effects on cecal microbial communities and parameters of microbial metabolism. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:1057. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01057

25. Fan P, Liu P, Song P, Chen X, Ma X. Moderate dietary protein restriction alters the composition of gut microbiota and improves ileal barrier function in adult pig model. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:43412. doi: 10.1038/srep43412

26. Tanja M, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. (2011) 27:2957–63. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507

27. Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, Sengamalay N, Ott S, Brotman RM, et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome. (2014) 2:1–7. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6

28. Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. (2010) 7:335–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303

29. Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. (2011) 27:2194–200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381

30. Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. (2013) 10:996–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

31. DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2006) 72:5069–72. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05

32. Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam SA, Mcgarrell DM, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. (2005) 33:294–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki038

33. Geirsdottir OG, Arnarson A, Ramel A, Jonsson PV, Thorsdottir I. Dietary protein intake is associated with lean body mass in community-dwelling older adults. Nutr Res. (2013) 33:608–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.05.014

34. Hohenshell LM, Cunnick JE, Ford SP, Kattesh HG, Zimmerman DR, Wilson ME, et al. Few differences found between early- and late-weaned pigs raised in the same environment. J Anim Sci. (2000) 78:38–49. doi: 10.2527/2000.78138x

35. Jones CK, Gabler NK, Main RG, Patience JF. Characterizing growth and carcass composition differences in pigs with varying weaning weights and postweaning performance. J Anim Sci. (2012) 90:4072–80. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4793

36. Sulabo RC, Mathai JK, Usry JL, Ratliff BW, Mckilligan DM, Moline JD, et al. Nutritional value of dried fermentation biomass, hydrolyzed porcine intestinal mucosa products, and fish meal fed to weanling pigs. J Anim Sci. (2013) 91:2802–11. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5327

37. Pieper R, Boudry C, Bindelle J, Vahjen W, Zentek J. Interaction between dietary protein content and the source of carbohydrates along the gastrointestinal tract of weaned piglets. Arch Anim Nutr. (2014) 68:263–80. doi: 10.1080/1745039X.2014.932962

38. Heinritz SN, Weiss E, Eklund M, Aumiller T, Louis S, Rings A, et al. Intestinal microbiota and microbial metabolites are changed in a pig model fed a high-fat/low-fiber or a low-fat/high-fiber diet. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0154329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154329

39. Yin J, Han H, Li Y, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Fang R, et al. Lysine restriction affects feed intake and amino acid metabolism via gut microbiome in piglets. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2017) 44:1749–61. doi: 10.1159/000485782

40. Yin J, Li Y, Zhu X, Liu G, Huang X, Fang R, et al. Effects of long-term protein restriction on meat quality, muscle amino acids, and amino acid transporters in pigs. J Agric Food Chem. (2017) 65:9297–304. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02746

41. Ijaz MU, Ahmed MI, Zou X, Hussain M, Zhang M, Zhao F. Beef, casein, and soy proteins differentially affect lipid metabolism, triglycerides accumulation and gut microbiota of high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:2200. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02200

42. Indiani CMDSP, Rizzardi KF, Castelo PM, Ferraz LFC, Darrieux M, Parisotto TM, et al. Childhood obesity and firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio in the gut microbiota: a systematic review. Child Obes. (2018) 14:501–9. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0040

43. Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. (2011) 12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60

44. Zhu Y, Shi X, Ye K, Xu X, Li C, Zhou G. Beef, chicken, and soy proteins in diets induce different gut microbiota and metabolites in rats. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:1395. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01395

45. Heo JM, Opapeju FO, Pluske JR, Kim JC, Hampson DJ, Nyachoti CM. Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: a review of feeding strategies to control post-weaning diarrhoea without using in-feed antimicrobial compounds. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. (2013) 97:207–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2012.01284.x

46. Boudry G, Jamin A, Chatelais L, Gras-Le Guen C, Michel C, Le Huërou-Luron I. Dietary protein excess during neonatal life alters colonic microbiota and mucosal response to inflammatory mediators later in life in female pigs. J Nutr. (2013) 143:1225–32. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.175828

47. Liu H, Zhang J, Zhang S, Yang F, Thacker PA, Zhang G, et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus fermentum I5007 favors intestinal development and alters the intestinal microbiota in formula-fed piglets. J Agri Food Chem. (2014) 62:860–6. doi: 10.1021/jf403288r

Keywords: protein sources, colon, semi-synthetic diet, bacterial communities, metabolites, piglets

Citation: Li R, Chang L, Hou G, Song Z, Fan Z, He X and Hou D-X (2019) Colonic Microbiota and Metabolites Response to Different Dietary Protein Sources in a Piglet Model. Front. Nutr. 6:151. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00151

Received: 27 February 2019; Accepted: 30 August 2019;

Published: 24 September 2019.

Edited by:

Helieh S. Oz, University of Kentucky, United StatesReviewed by:

Wenkai Ren, South China Agricultural University, ChinaHein Min Tun, School of Public Health, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Mrigendra Rajput, Arkansas Tech University, United States

Bingkun Zhang, China Agricultural University (CAU), China

Copyright © 2019 Li, Chang, Hou, Song, Fan, He and Hou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zehe Song, emVoZXNvbmcxMTFAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Rui Li

Rui Li Ling Chang

Ling Chang Gaifeng Hou

Gaifeng Hou Zehe Song

Zehe Song Zhiyong Fan

Zhiyong Fan Xi He

Xi He De-Xing Hou

De-Xing Hou