- 1CAS Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China

- 2Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao, China

- 3Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China

- 4University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Nutrients and phytoplankton associated with mariculture development are important concerns globally, as they can significantly impact water quality and aquaculture yield. Currently, there is still insufficient information regarding the variations in nutrients and phytoplankton community of intensive mariculture systems, and effective treatment is lacking. Here, based on consecutive daily monitoring of two Litopenaeus vannamei ponds from July to October, the dynamic variations in nutrients and phytoplankton were elucidated. In addition, modified clay (MC) method was adopted to regulate the nutrients and phytoplankton community. The temporal variations in organic and inorganic nutrients presented fluctuating upward trends. Notably, organic nutrients were the dominant species, with average proportions of TON/P in TN/P were as high as 75.29% and 87.36%, respectively. Furthermore, a marked increase in the ratios of dinoflagellates to diatoms abundance were also observed in the control pond, concurrently with dominant organic nutrients, ascending N/P ratio and decreasing Si/N and Si/P ratios. In the MC-regulated pond, MC reduced the contents of both organic and inorganic nutrients. Furthermore, a distinct change pattern of dominant phytoplankton community occurred, with green algae becoming the most abundant phytoplankton in the MC-regulated pond. This study can provide new insights into an effective treatment for managing water quality and maintaining sustainable mariculture development.

Highlights

● Organic N and P were the dominant species of nutrients in mariculture shrimp ponds.Higher N/Si and N/P ratios were prominent over the production cycle.

● Variations in nutrients favored the potential predominance of dinoflagellates.

● Modified Clay effectively reduced nutrient contents and regulated the phytoplankton community.

Introduction

Mariculture is one of the fastest-expanding sectors worldwide (Campbell and Pauly, 2013; Froehlich et al., 2018; Meng and Feagin, 2019), with global production reaching 87.5 million tons in 2020 (FAO(Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2022). Notably, China has played a major role in this growth (Li et al., 2017). In China, pond farming is a dominant aquaculture farming system. For instance, the total production of pond farming continued to increase in 2019, contributing approximately 50% of national aquaculture production (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2020). However, the rapid development of mariculture has been accompanied by environmental pollution, such as nutrient and organic matter overload, harmful algal blooms, and drug residues, which pose threats to mariculture development (Briggs and Funge-Smith, 1994; Couch, 1998; Bouwman et al., 2013; Han et al., 2021). Currently, mariculture has become a significant and expanding cause of coastal nutrient enrichment and has influenced marine ecosystems of the receiving coastal waters (Bouwman et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017).

As is the case with all intensive farming systems, large quantities of excess feed and faeces increase the nutrient loading to water bodies, which cause the deterioration of water quality and restrict the sustainable mariculture (Alonso-Rodrıguez and Páez-Osuna, 2003; Casé et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2017; Díaz et al., 2019). Notably, the accumulation of ammonia and nitrite will exert toxic effects on aquaculture organisms and cause disease proliferation in culture ponds (Casé et al., 2008; Glibert, 2016). Moreover, the excessive accumulation and unbalanced proportion of nutrients will influence the phytoplankton community and can cause the occurrence of ‘harmful algal blooms (HABs)’ (Glibert, 2016; Díaz et al., 2019). Increasing occurrences of HABs, such as Karenia spp, dinoflagellates, and Aureococcus anophagefferens, are leading to growing deleterious impacts including the poisoning, asphyxiation and even the death of mariculture organisms and human poisoning (Davidson et al., 2009; Gobler et al., 2011; Anderson, 2012; Brown et al., 2020). On the other hand, the unbalanced proportion of nutrients can cause a significantly higher toxicity activity of phytoplankton (Johansson and Granéli, 1999; Hagström and Granéli, 2005). Furthermore, the discharge of mariculture effluents generates diverse effects on coastal waters (Bouwman et al., 2013). For instance, over 26% of the excess nitrogen in China’s waters is likely a result of shrimp production alone (Meng and Feagin, 2019).

Modified clay (MC), produced from natural clays via the surface modification by inorganic or organic compounds, can effectively control HABs (Yu et al., 2017; Song et al., 2021). Currently, MC technology has been included as a national standard method to control HABs and is widely employed in China (Yu et al., 2017). Previous studies found that MC can not only remove algal cells but also reduce nutrients and organic matter contents, improve water quality and reduce the degree of eutrophication (Gao et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2017; Song et al., 2021). In addition, MC has no adverse effects on the survival and growth of typical economically marine organisms when used at appropriate dosages (Zhang et al., 2019; Song et al., 2021). Furthermore, in mitigating the blooms of toxin-producing dinoflagellates, MC can quickly reduce algal toxins in water (Hagström and Granéli, 2005; Lu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019).

The variations in nutrients and phytoplankton associated with mariculture development are important concerns globally, as they can have a variety of potential impacts on the mariculture yield and the environment of receiving water. Currently, there is still insufficient information on the dynamic variations in nutrients and phytoplankton, and effective regulation treatment is lacking. In the present study, based on daily monitoring of nutrients and phytoplankton of intensive mariculture shrimp ponds in Laizhou Bay, the specific objectives were to: (i) elucidate the dynamic variations in nutrients and explore the potential responses of phytoplankton community to the variations in content, composition and stochiometric ratio of nutrients, (ii) compare the variations in nutrients and phytoplankton community between an MC-regulated and control ponds and assess the regulation effects of MC. The results of this study are crucial for the comprehensive understanding of the variation patterns of nutrients and phytoplankton in the mariculture systems, and provide new insights into an effective regulation treatment for managing water quality and maintaining sustainable mariculture development.

Materials and methods

Study area

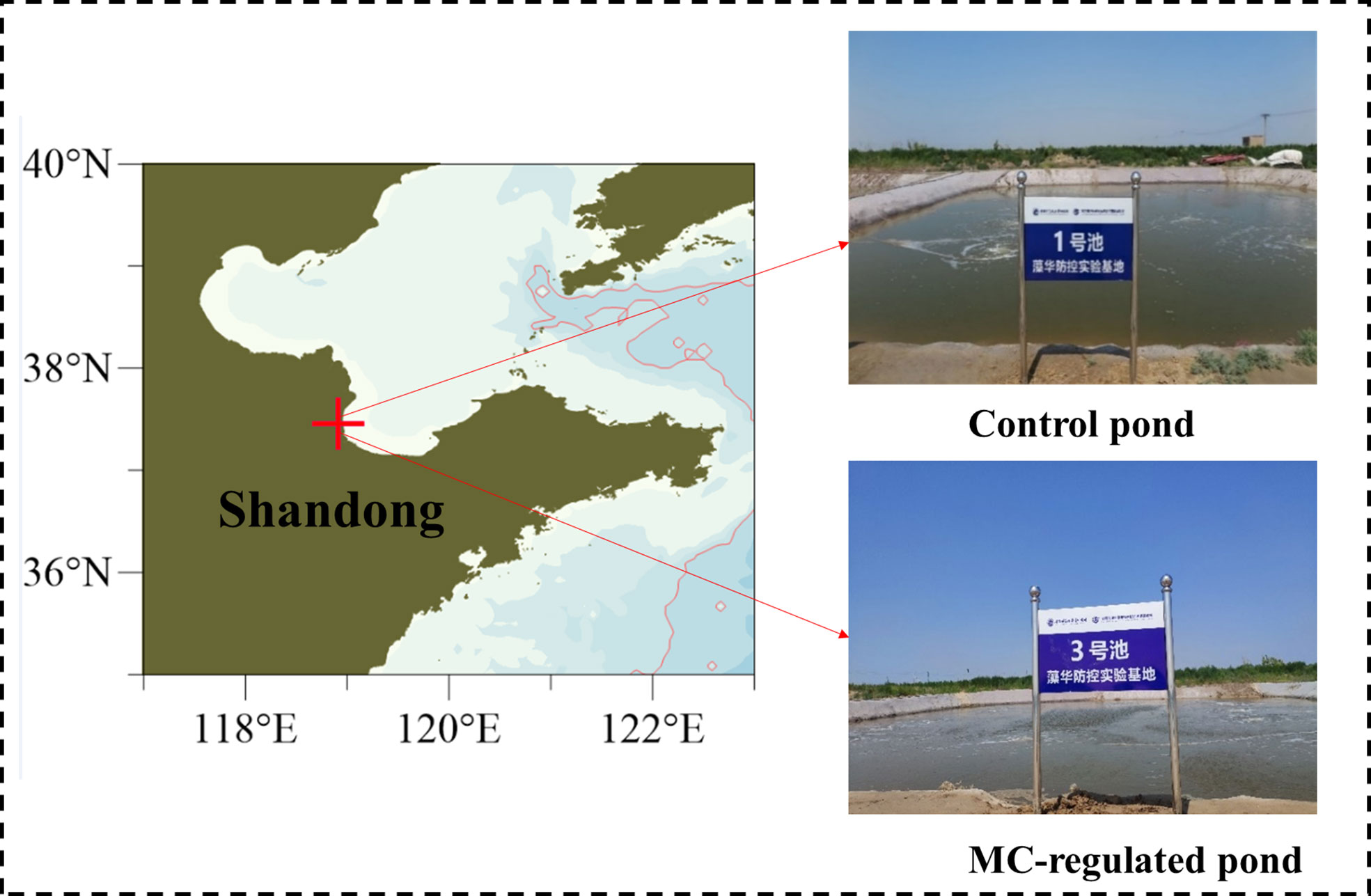

Intensive rearing Litopenaeus vannamei ponds were located in Dongying, Laizhou bay, China (118°55’E, 37°27’N), and two shrimp ponds were selected as the control pond and the MC-regulated pond, respectively (Figure 1). Each pond covered an area of approximately 1000 m2, with an average water depth of 1.5 m (shrimp stocking density: 5 × 104 shrimp per pond, the average body length of shrimp: 1.6 cm). There were no water changes during the culture process and each pond was equipped with an aerator to ensure a suitable dissolved oxygen concentration. The control pond adopted the traditional culture method for breeding, while the MC-regulated pond adopted MC to regulate water quality and phytoplankton community. The elemental composition and content of the MC were determined by XRF, as shown in Table S1. The MC is prepared into a suspension with seawater and then sprayed on the pond in a boat with spraying equipment. And the spraying of the MC were determined according to the variations in water quality and phytoplankton community (Table S2).

Sampling and analysis

Hydrographic parameters, including temperature and salinity, were measured by a YSI multiparameter water quality meter (YSI Ltd., USA). The water samples analyzed for nutrients, Chl a and 18S rDNA were collected at a depth of 0.5 m below the surface from multiple points (four corners and the center) in the pond every two days. In addition, parallel samples were collected every week. Samples for measuring total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) were collected and stored at -20°C in a sulfuric acid solution (50% v/v) with a final concentration of 0.2%. Water samples for the determination of dissolved inorganic nutrients were filtered under dim light through Whatman GF/F filter membranes (pore size: 0.68 μm). The filtrate was poured into 60 mL polyethylene bottles added to approximately 0.1 mL of chloroform and stored at -20°C. For the Chl a measurement, 100 mL of water sample was filtered using What man GF/F filters after initial filtration through a 200 µm nylon sieve, and the filter membrane was wrapped in stored in a dark environment at -20°C. Water samples for 18S rDNA were filtered through a 200 µm nylon sieve to eliminate the interference of zooplankton. Following filtration, the samples were passed through a 0.22 µm cellulose acetate membrane filter. The filters were collected in a centrifuge tube and stored in liquid nitrogen at -196°C.

In the laboratory, the concentrations of TN, TP, and dissolved inorganic nitrogen [DIN, including nitrate (NO3-), nitrite (NO2-), TAN (non-ionic ammonia (NH3) and ammonium ion (NH4+))], dissolved inorganic phosphorous (DIP) and dissolved silicate (DSi) were measured with a SKALAR Flow Analyser (Skalar Ltd., Netherlands). The TON and TOP contents were calculated by the differential subtraction method, i.e. TON=TN-DIN, TOP=TN-DIP. Chl a was extracted in acetone, and its concentrations were determined by using a Trilogy fluorometer (Turner Design Ltd., USA).

DNA extraction, PCR, and gene sequencing

DNA was extracted using the HiPure Soil DNA Kits (Magen, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For 18S rDNA genes, universal primers 528F (5’-GCGGTAATTCCAGCTCCAA-3’) and 706R (5’-AATCCRAGAATTTCACCTCT-3’) targeting the V4 regions were used for PCR (95°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 45 s, 72°C for 90 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min). Ampicons were extracted using 2% agarose gels and purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced (PE250) on an Illumina platform according to the standard protocols.

Data processing and analysis

The raw reads were further filtered using FASTP to obtain high-quality clean reads. Paired-end clean reads were merged as raw tags using FLASH, with a minimum overlap of 10 bp and a mismatch error rate of 2%. The clean tags subjected to specific filtering conditions were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of ≥ 97% similarity using the UPARSE pipeline. All chimeric tags were removed using the UCHIME algorithm; finally, effective tags were obtained for further analysis. The tag sequence with the highest abundance was selected as the representative sequence within each cluster. The representative OTU sequences were classified into organisms by a naïve Bayesian model using the RDP classifier based on the SILVA database, with a confidence threshold value of 0.8. To further elucidate the abundance and richness of eukaryotic phytoplankton from the 18S rDNA results, the nonalgal OTUs, including Metazoa, Fungi, Apicomplexa, Intramicronucleata, Streptopyta, Postciliodesmatophora, Opalozoa, and unclassified data were removed. In addition, the relative abundance of each taxon was calculated by dividing the sequence number of OTUs of this group by the total sequence number of algae.

The ranking analysis of phytoplankton and environmental factors was performed using CANOCO for Windows 5.0 software package. To satisfy the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance, all species data and environmental data were subjected to log (x + 1) transformation prior to multivariate analysis (Lepš and Šmilauer, 2003). According to the results of detrended correspondence analysis (DCA), redundancy analysis (RDA) was selected to determine the relationship between phytoplankton and environmental factors. The significance of the RDA ranking model was verified by the Monte Carlo permutation test.

Results

Temporal variations in nutrients

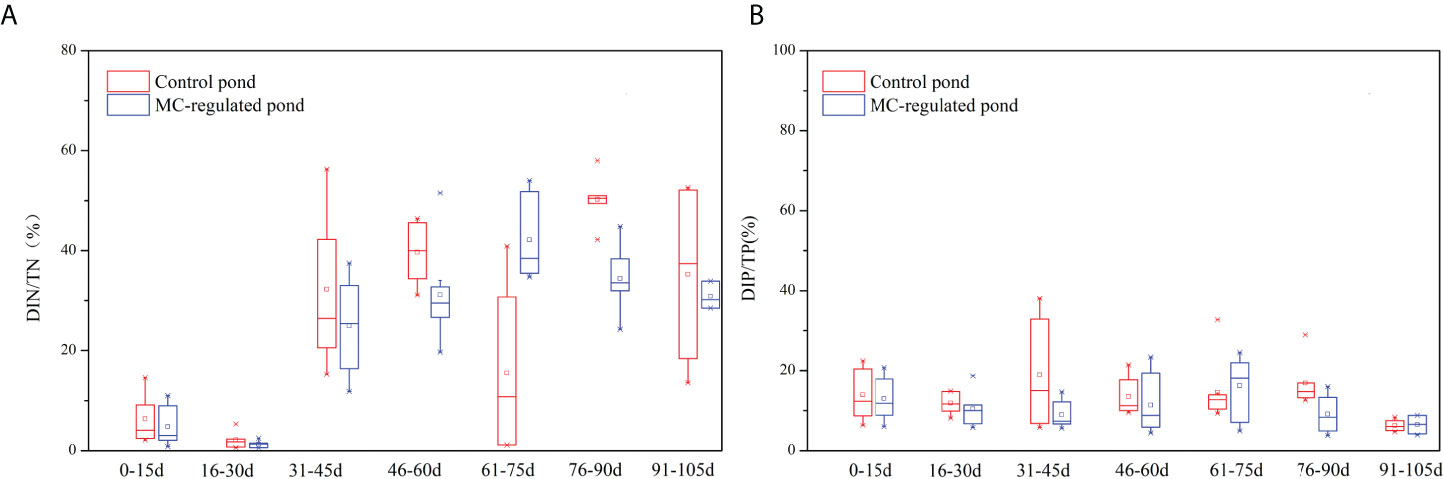

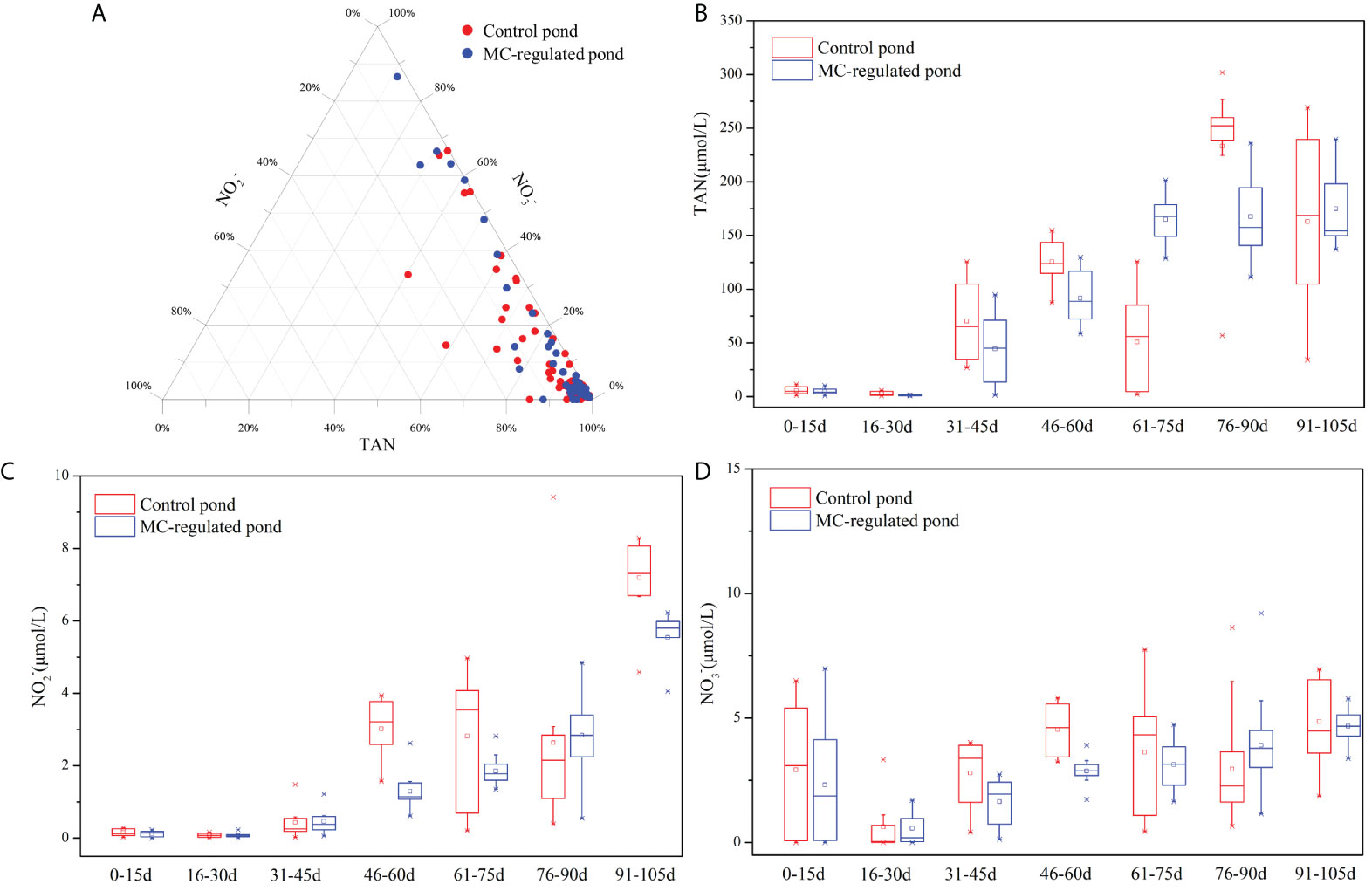

The TN and TP concentrations in the control and MC-regulated ponds varied in the ranges of 95.10-588.76 μmol/L, 100.86-557.41μmol/L and 1.73-22.47 μmol/L, 2.24-19.32 μmol/L, respectively. Notably, the contents of TN (Figure 2A) and TP (Figure 2B) in both ponds exhibited a rapid and fluctuating upward trend over time. Overall, during the main culture period, the TN and TP concentration of the MC-regulated pond were lower than those of the control pond. As for TON and TOP, the ranges in the control and MC-regulated ponds were 88.66-478.81 μmol/L, 43.81-387.82 μmol/L, and 0.81-21.42 μmol/L, 1.85-18.60 μmol/L, respectively. The mean concentrations of TON (Figure 2C) and TOP (Figure 2D) were significantly higher than those of DIN and DIP, which indicated that organic nutrients were the predominant species of nutrients in the water column of shrimp ponds. Similarly, significant temporal variations in TON and TOP concentrations were observed over the study period, which showed an increasing trend over time. Overall, in the late stage, the TOP concentration of the MC-regulated pond was lower than that of the control pond. The concentrations of DIN and DIP in the control and MC-regulated ponds varied in the ranges of 0.91-281.82 μmol/L, 0.79-248.37 μmol/L, and 0.22-5.62 μmol/L, 0.19-3.75 μmol/L, respectively. Significant temporal variations in the DIN (Figure 2E) and DIP (Figure 2F) were observed, with a fluctuating upward trend observed in the middle and late stages. Comparatively, the concentrations of DIN, especially DIP, in the MC-regulated pond were lower than those in the control pond during the study period. The DSi concentrations remained relatively stable during the study period (Figure 2G), and DSi concentrations in the control and MC-regulated ponds varied in the ranges of 1.55-8.96 μmol/L and 1.81-8.86 μmol/L.

Figure 2 Temporal variations in (A) TN, (B) TP, (C) DON, (D) DOP, (E) DIN, (F) DIP and (G) DSi concentrations in the water column.

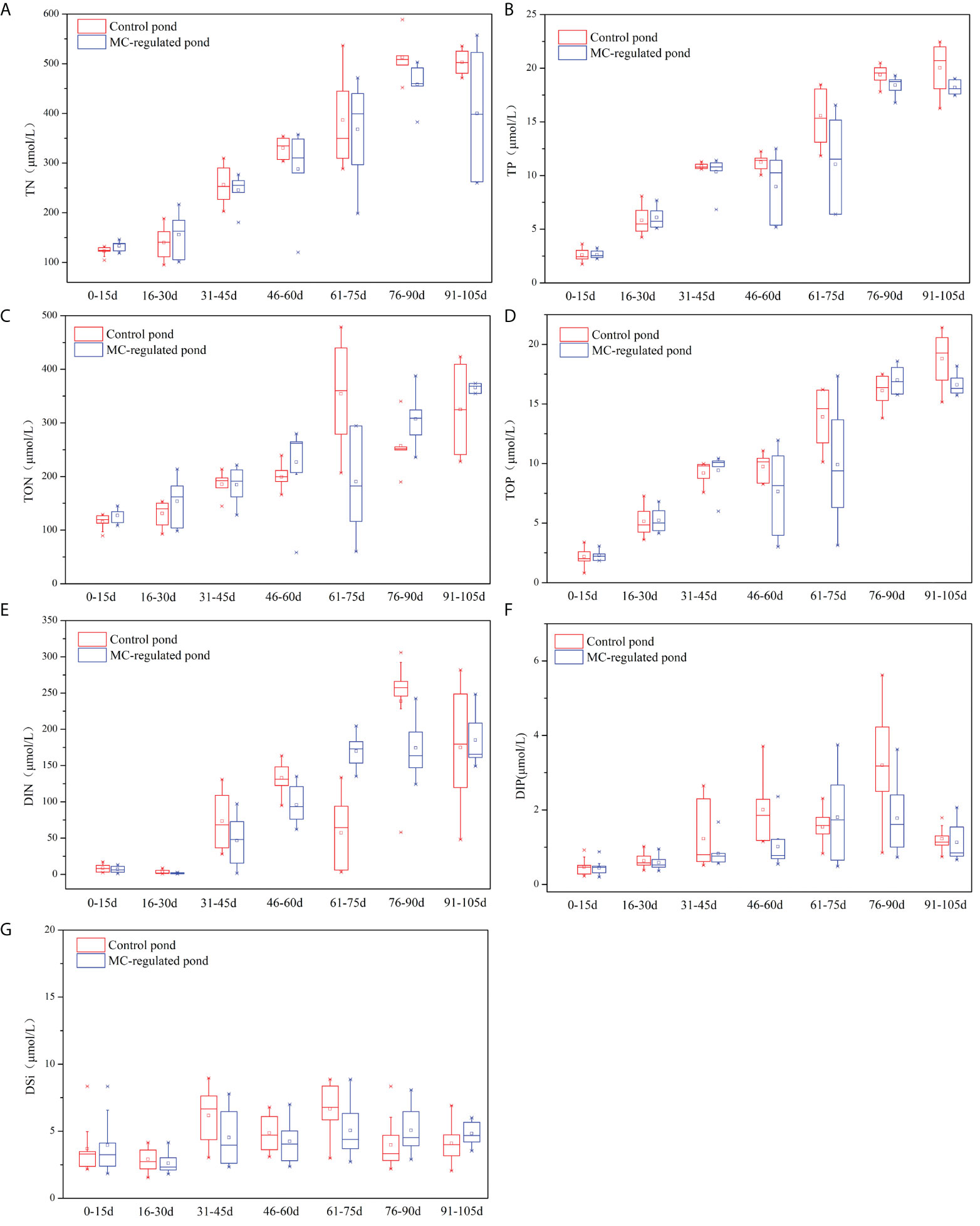

The concentrations of TAN, NO2- and NO3- ranged as follows: 0.78-301.93 μmol/L, 0.01-9.41 μmol/L and 0.00-8.63 μmol/L, respectively, in the control pond; while 0.70-239.71 μmol/L, 0.00-6.23μmol/L, and 0.00-9.21 μmol/L, respectively, in the MC-regulated pond. Notably, TAN was the predominant species of DIN, with significantly higher concentrations than those of NO2- and NO3-, and its average content accounted for 86.72% and 88.30% of the DIN concentration in the control and MC-regulated ponds, respectively (Figure 3A). Temporal variations in the TAN (Figure 3B) and NO2- (Figure 3C) concentrations of both ponds were observed, which exhibited an overall increasing trend during the study period. In addition, the TAN and NO2- concentrations were lower in the MC-regulated pond than in the control pond during the main study period. Differently, the concentrations of NO3- exhibited a different temporal variation (Figure 3D), decreasing in the early stage and then increasing in volatility during the middle and late stages.

Figure 3 (A) The composition of DIN and temporal variations in each component ((B) TAN, (C) NO2-, (D) NO3-) of DIN.

Temporal variations in Chl a concentrations and phytoplankton community

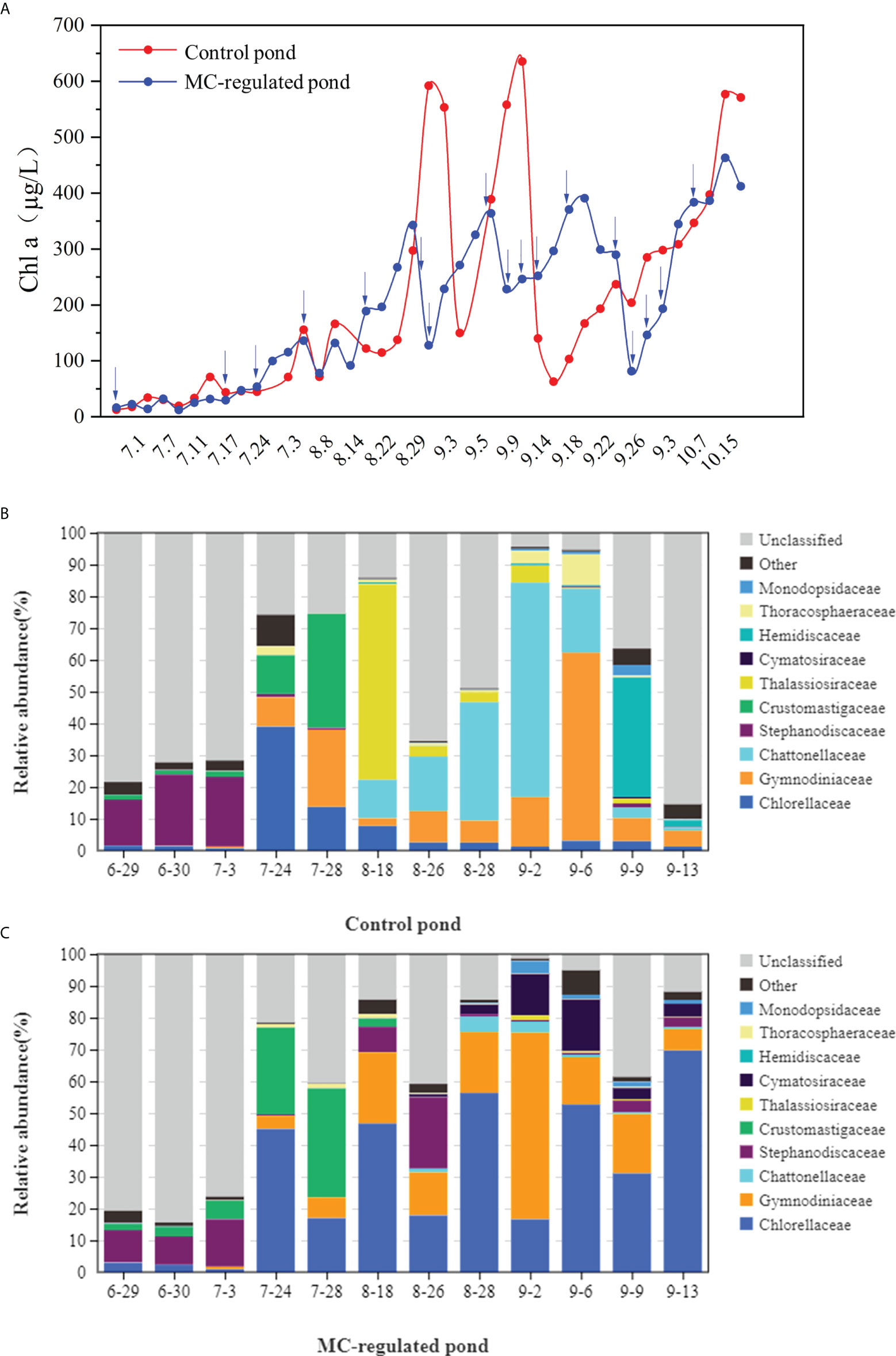

The Chl a concentrations ranged between 12.57-635.40 µg/L and 12.25-489.93 µg/L in the control and MC-regulated ponds, respectively. There were significant temporal variations in Chl a concentrations in the two ponds, with considerably lower concentrations observed during the initial stage than the other two stages (Figure 4A). Comparatively, the variation of Chl a in the control pond exhibited greater fluctuations than that in the MC-regulated pond. As for phytoplankton community, a total of 2,728,684 effective tags by 18S rDNA gene sequencing were obtained, after quality screening, with an average N50 of 343 bp. After clustering based on a 97% similarity threshold and removing non-algal OTUs, 212 and 222 algal OTUs were obtained from the control and the MC-regulated ponds, respectively. Overall, six phyla, 16 classes, 22 orders, 29 families, 33 genera and 38 species were identified after annotation. Among them, the top ten algae with the highest abundance at the family level were defined as the dominant phytoplankton genera, and the abundance of families in the two ponds is shown in Figures 4B, C. In the initial stage, the phytoplankton community in both the control and the MC-regulated ponds were similar and dominated by diatoms, mainly including Stephanodiscaceae at the family level. Thereafter, the phytoplankton composition exhibited temporal variations, with a decreasing ratio of diatoms was observed. Moreover, the dominant phytoplankton species exhibited different variation pattern between the two ponds. Notably, the dominant phytoplankton species in the control pond changed to dinoflagellates, mainly including Gymnodiniaceae at the family level. And the proportion of dinoflagellates (30.02%) in the control pond was higher than that of the MC-regulated pond (25.37%) (Welch’s t-test, P > 0.05). In addition, the Chattonellaceae (Heterosigma at the genus level), one of the HABs species, was another dominant family in the control pond, and had a much higher proportion in the control pond (13.09%) than the MC-regulated pond (0.92%). In contrast, the dominant phytoplankton species in the MC-regulated pond became green algae, mainly including Chlorellaceae at the family level and Nannochloris at the genus level, which had the highest proportion. In addition, the mean relative abundance (29.9%) of Chlorellaceae was significantly higher than that in the control pond (6.41%) (Welch’s t-test, P < 0.05).

Figure 4 Temporal variations in the (A) Chl a concentrations and relative abundance of major taxa of phytoplankton in (B) the control pond and (C) MC-regulated pond at the family level. The blue arrows indicates the date when MC was applied.

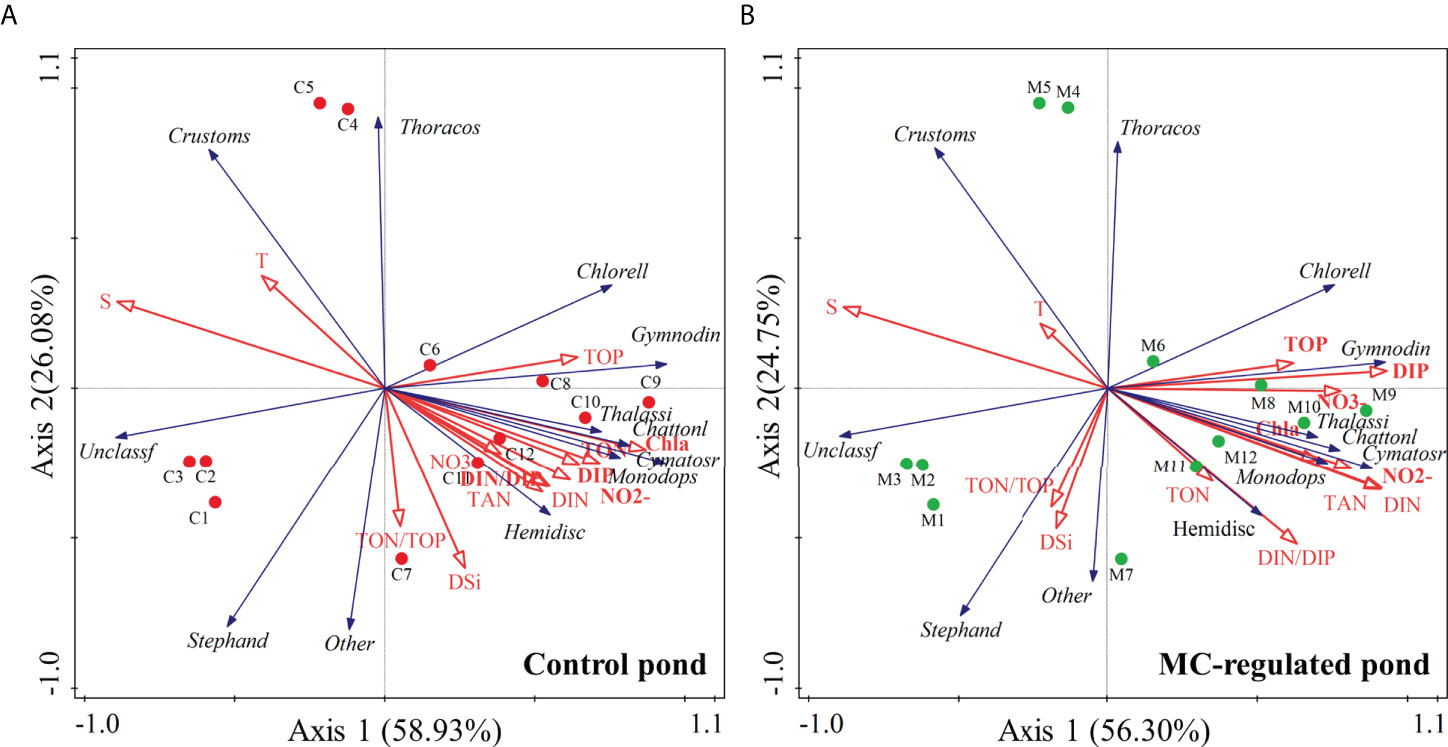

RDA ranking analysis between the abundance of major phytoplankton species and environmental variables

Overall, the phytoplankton richness, indicated by Chl a concentration, was negatively correlated with salinity and temperature, and positively correlated with nutrients in both organic and inorganic forms (Figure 5), resulting in gradually higher phytoplankton biomass as the nutrient accumulated during the study period. As for the phytoplankton communities, the RDA results indicated that the phytoplankton patterns were largely grouped by nutrient regimes. In addition, there were temporal variations in the relationship between phytoplankton communities and environmental variables. In the initial stage, the clustering characteristics of the samples from the control and MC-regulated ponds were basically the same. During this period, the phytoplankton composition was dominated by diatoms, mainly including Stephanodiscaceae, whose abundance was positively correlated with DSi. Thereafter, the clustering characteristics of the samples from the two shrimp ponds differed, indicating that the environmental influences on the distribution of the samples from the two ponds became inconsistent. In the control pond, the dominant phytoplankton species have become harmful dinoflagellates, mainly including Gymnodiniaceae and Thoracosphaeraceae. And their abundance responded strongly to TON and TOP, as indicated by their positive correlations. In contrast, the dominant species of phytoplankton in the MC-regulated pond was Chlorellaceae, a kind of green algae, and its abundance exhibited a significant positive correlation with TOP and DIP and a significant negative correlation with DSi.

Figure 5 RDA ranking of samples and phytoplankton families with environmental variables in (A) the control pond and (B) the MC-regulated pond.

Discussion

Nutrient variation characteristics in mariculture ponds and their impacts on water quality of receiving coastal waters

In the intensive mariculture pond systems, the variation and accumulation of nutrients could cause the deterioration of water quality and pose threat to the organisms (Alonso-Rodrıguez and Páez-Osuna, 2003; Casé et al., 2008; Ray et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2017; Díaz et al., 2019). In addition, the export of mariculture pond effluents is an important anthropogenic source of nutrients pollution in coastal waters (Cao et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017), which has significantly increased the nutrients concentrations (Paerl, 2006; Danielsson et al., 2008; Glibert and Burford, 2017), and altered the nutrients composition and structure (Glibert et al., 2012; Peñuelas et al., 2012; Sutton et al., 2013). In the present study, the nutrients of the mariculture shrimp ponds exhibited unique characteristics compared with typical coastal regions. The concentrations of TON/P and DIN/P in the shrimp ponds were significantly higher, while DSi concentrations were lower than those in typical coastal waters. Notably, organic forms of nitrogen and phosphate were dominant (Figure 6), which could be attributed to continuous input and lower utilization efficiency of feeds (Bouwman et al., 2013). In general, more than 63% of nitrogen and 83% of phosphorus from feed have been discharged into the water column and sediment (Bouwman et al., 2013). Moreover, a large supply of organic nutrients stimulates microbial decomposition in the water column and sediment, as indicated by the increasing trend of DIN concentrations and DIN/TN ratios in this study. Notably, TAN was the predominant species of DIN, and it could be oxidized to NO2- and NO3-. Yang et al., 2017 found that the sediment fluxes in the shrimp ponds were significantly higher than the range of 0.01-31.25 mg N/(m2 h). As the most common toxicant in mariculture (Santacruz-Reyes and Chien, 2010), the general safe concentrations for TAN and NO2- in mariculture systems are under 200 μg/L and 10 μg/L, respectively (Lai, 2014), although the specific toxicity is species-dependent. In this study, the concentrations of TAN and NO2- were higher than the safe concentrations, and this result was consistent with the study by Yang et al. (2017), which could potentially restrict the development of shrimp farming.

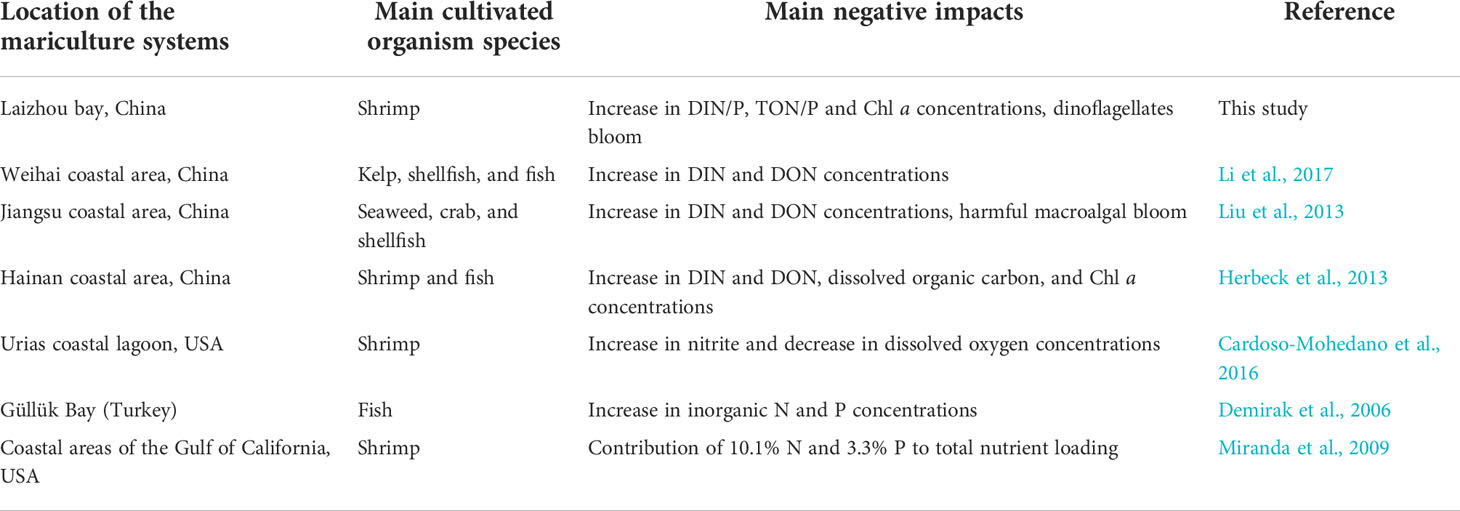

Moreover, as an important anthropogenic source of nutrient pollution in coastal waters (Table 1). (Lacerda et al., 2008) estimated that more than 827 t N/yr and 69.2 t P/yr were exported from shrimp ponds of northeastern Brazil. In the Gulf of California, the estimated nutrients loads from shrimp aquaculture were 9044 t N/yr and 3078 t P/yr (Páez-Osuna et al., 1997; Páez-Osuna et al., 2013; Páez-Osuna et al., 2017). In the present study, we further estimated the potential impacts of effluent discharge on water quality of receiving coastal waters. Assuming that our average data during the study period are representative of the aquaculture ponds across China, with a total area of 2.57×1010 m2 and a mean water depth of 1.4 m (Yang et al., 2017), approximately 1.05×105 t TON (in terms of N), 1.08×104 t TOP (in terms of P), 4.80×104 t DIN and 1.69×103 t DIP accumulated in the pond system and could be discharged into coastal waters. This value represents approximately 16% of the total nutrient fluxes from the main rivers of China into the sea, whose contribution was smaller than other anthropogenic nutrient sources (SOA (State Oceanic Administration), 2017). Our results were basically consistent with the estimation of Meng and Feagin, 2019, which proposed that more than 26% of the excess nitrogen in China’s waters likely originates from shrimp production alone (Meng and Feagin, 2019). With the rapid development of marine aquaculture in China, its potential impact on water pollution will be more prominent in the future. In addition, the nutrients characteristics of the shrimp ponds could also significantly alter the composition and structure of phytoplankton community and cause the occurrence of HABs, which could also limit healthy mariculture development.

Table 1 Main negative impacts caused by intensive mariculture systems in the Laizhou bay compared with other coastal areas.

The impacts of nutrient variations on the phytoplankton community and potential occurrences of HABs

A healthy and stable phytoplankton community structure is crucial for the stability and balance of mariculture ecosystems (Alonso-Rodrıguez and Páez-Osuna, 2003; Casé et al., 2008). Previous studies have documented the negative effect of algal blooms, especially dinoflagellate blooms, on shrimp development (Shumway et al., 1990; Alonso-Rodrıguez and Páez-Osuna, 2003; Matsuyama and Shumway, 2009; Lou and Hu, 2014). Generally, the structure and variation of phytoplankton communities are controlled by the complex interactions between environmental drivers and biotic interactions (Griffiths et al., 2016). Among them, the concentration, composition, and structure of nutrients are crucial for the growth and community succession of phytoplankton and the potential occurrence of HABs. Generally, both the inorganic (Altman and Paerl, 2012; Kamp et al., 2015) and organic nutrients are available for phytoplankton (McCarthy, 1972; Lønborg and Álvarez-Salgado, 2012). This could also be verified by the positive correlations between the Ch l a concentration with both the TON/P and DIN/P concentrations in the present study. Generally, most phytoplankton preferentially assimilate NH4+ due to the lower energy consumption requirements than those (Kamp et al., 2015). In addition, different species of phytoplankton differ in their preferences and responses to different forms of nutrients, previous studies indicated that NO3- is preferred by diatoms (Goldman and Glibert, 1983; Lomas and Glibert, 1999; Lomas et al., 2002; Berg et al., 2003), while organic nitrogen is preferred by dinoflagellates (Glibert and Terlizzi, 1999; Dyhrman and Anderson, 2003; Fan et al., 2003). For instance, dinoflagellates could absorb DON and easily replace other algae as the dominant species when DON is the nitrogen source (Collos et al., 2014). In the present study, DON/P were the predominant species, although an increasing trend in the ratio of DIN was observed in the late stages, with an average proportion of 78.92% and 88.18% in TN and TP, respectively. Furthermore, the predominant TAN in DIN were observed in this study, with a significantly higher proportion than those of the NO2- and NO3-. This was consistent with previous studies, which could be attributed to the continuous decomposition of protein-rich feeds (Yang et al., 2017). Consequently, as the main forms of nutrient reservoirs, the nutrient pattern, dominated by TON and TAN, could contribute to the potential dominance of dinoflagellates, as verified by the 18S rDNA results.

In addition, the fluctuation in nutrient structure can induce a shift in dominant species of phytoplankton, and researchers have proposed that the variation of N/P ratios might stimulate HABs worldwide (Alonso-Rodrıguez and Páez-Osuna, 2003; Davidson et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). Generally, the pattern of “more N, less P and Si” may lead to a shift in the dominant species from diatoms to dinoflagellates (Li et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). For instance, excessive DIN and persistently elevated N/P have led to the dominant species shifting from diatoms to dinoflagellates in the Changjiang estuary (Wang and Cao, 2012). Likewise, Justić et al., (1995) suggested that the increase in N and P and the relative stabilization of Si in coastal waters, increased the possibility of Si limitation, leading to a shift in dominant phytoplankton species from diatom to non-diatom species. By comparing the differences in phosphorus requirements and uptake and utilization strategies of different algal species, the previous study has indicated that diatoms have the lowest mean optimum nitrogen to phosphorus ratio, followed by dinoflagellates, and green algae have the highest mean optimum nitrogen to phosphorus ratio (Hillebrand et al., 2013). In this study, there were no absolute concentration limitations of N, P, and Si in mariculture pond systems. However, the nutrient structure in terms of N/P and N/Si ratios exhibited significant temporal variations during the culture process. Relatively stable ratios of TON/TOP (with an average value of 27) but fluctuating increasing ratios of DIN/DIP (with an average value of 66) were found, which could be attributed to the higher mineralization and accumulation rate of N than P. In addition, increased DIN/DSi and decreased DSi/DIP ratios, indicating potential Si limitation, were observed especially in the middle and late stages. The variations in the nutrient stoichiometric ratios favored the shift in the dominant species that changed from diatoms to dinoflagellates. In addition, a gradually increasing proportion of dinoflagellates and decreasing proportion of diatoms corresponded well with the variations in N/P and N/Si ratios.

Regulation effects of MC on nutrients and the phytoplankton community

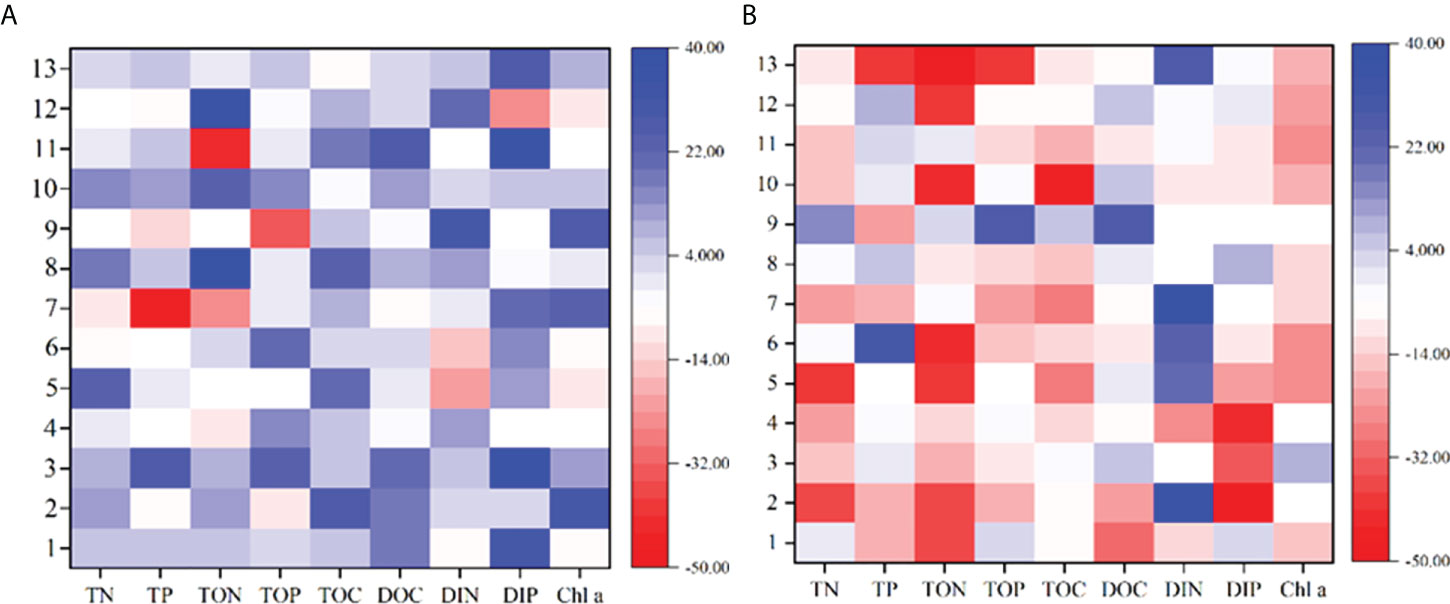

The intensive mariculture systems are under the threat of excessive organic loading and nutrient accumulation, which cause water quality problems and subsequent diseases (Hargreaves and Tucker, 2004; Santacruz-Reyes and Chien, 2010; Castillo-Soriano et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014). Notably, the TAN threat can become pronounced in intensive culture systems when TAN is rapidly accumulated to concentrations beyond the safe level (Santacruz-Reyes and Chien, 2010). More importantly, it can trigger outbreaks of HABs and pose a serious threat to the aquaculture ecosystem (Huang et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2020). In this study, the initiative MC technology was adopted to regulate the nutrients and phytoplankton in the typical mariculture pond system. We observed that the nutrient contents of both organic and inorganic forms in the water column effectively decreased in most instances 24 h after the spray of MC (Figure 7). The TON and TOP contents could be reduced by up to 57% and 65%, respectively. While the TAN, NO2- and PO43- concentrations could be reduced by up 32%, 45%, and 64%, respectively, in the MC-regulated pond. In contrast, both organic and inorganic forms in the water column of the control pond increased in most instances. Overall, the contents of these nutrients in the MC-regulated pond were lower than those in the control pond. It has been suggested that MC can reduce inorganic nutrients, especially phosphate, and organic nutrients through adsorption flocculation and chelation (Lu et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2017). In addition, MC could cause algal cells to flocculate and settle to the bottom layer, and the interaction of clay minerals with organic matter provides physical protection for organic matter (Hemingway et al., 2019). This protection could delay the microbial (Pinck and Allison, 1951) and oxidative (Eusterhues et al., 2003) decomposition processes of organic matter and reduce the mineralized regeneration of nutrients.

Figure 7 Changes in nutrients and Chl a in (A) the MC-regulated pond before and after spraying of MC and the comparison with (B) the control pond.

Furthermore, MC exerted a moderating effect on the phytoplankton biomass and community in the shrimp pond. In this study, the phytoplankton biomass was significantly higher and exhibited greater volatility in the control pond. In addition, HABs have occurred twice in the control pond, including an H. akashiwo bloom on September 2 with a density of 1.26 × 105 cells/mL (He et al., unpublished data). In contrast, the phytoplankton community in the MC-regulated pond was relatively stable in change and no HABs occurred during the study period. Based on the mean Bray-Curtis distances and molecular ecological network analysis of the community, (Ding et al. 2021) proposed that MC could enhance the resistance of phytoplankton ecological communities in cultured waters to environmental disturbance. Moreover, under the traditional condition, a high propensity for dinoflagellate blooms existed, influenced by the variation in the composition and structure of nutrients, and posed a potential risk to the growth of shrimp. This result could be verified by the variation in the dominant species of phytoplankton that changed from diatoms to dinoflagellates in the control pond. Compared with the control pond, the percentage of dinoflagellates in the MC-regulated pond was maintained at a lower level, and the percentage of green algae was higher, with Nannochloris being the dominant species. As an aquatic bait algae species, Nannochloris can improve the survival and production rate of fish and shrimp to some extent, which is important to maintain the stability of the ecosystem (Alonso-Rodrıguez and Páez-Osuna, 2003; Davidson et al., 2009). MC can directly dispose of HAB organisms through flocculation; additionally, they can induce the programmed mortality of red tide organisms through oxidative stress and other effects, thus controlling HABs (Yu et al., 2017). On the one hand, the Nannochloris could occupy a favorable ecological niche and became dominant after the removal of targeted dinoflagellates in the MC-regulated pond. On the other hand, the MC increased the N/P ratio and favored the Nannochloris, which has a higher average optimal nitrogen to phosphorus ratio than dinoflagellates (Hillebrand et al., 2013).

Conclusion

This research studied the dynamic variations in nutrients and phytoplankton of intensive mariculture systems and explored the effects of MC. The intensive culture of Litopenaeus vannamei caused a temporal significant increase in nutrients, especially in the organic forms. In addition, concurrently with ascending N/P ratio and decreasing Si/N and Si/P ratios, a marked increase in the biomass and ratios of dinoflagellates to diatoms abundance were also observed, which pose a potential threat to the mariculture organism. The MC reduced the contents of nutrients in both organic and inorganic forms, and improved the water quality. Moreover, MC effectively removed the dinoflagellates and contribute to the dominance of Nannochloris, which improved the stability of the phytoplankton community. This study provide new insights into an effective regulation treatment for managing water quality and maintaining sustainable mariculture development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LC: writing – original draft and investigation. YD: writing – review & editing and formal analysis. LH: writing – review & editing and data curation. ZW: writing – review & editing and data curation. YY: writing – review & editing and investigation. XC: writing – review & editing and formal analysis. XS: writing – review & editing. ZY: writing – review & editing and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the research group for their assistance with data acquisition during the experiments. Additionally, we are grateful to the reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. This study was supported by the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grants No. XDA19060203), the “Key Research Program of the Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grants No. COMS2020J02)”, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 42006119).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.976353/full#supplementary-material

References

Alonso-Rodrıguez R., Páez-Osuna F. (2003). Nutrients, phytoplankton and harmful algal blooms in shrimp ponds: a review with special reference to the situation in the gulf of California. Aquaculture. 219 (1-4), 317–336. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00509-4

Altman J. C., Paerl H. W. (2012). Composition of inorganic and organic nutrient sources influences phytoplankton community structure in the new river estuary, north Carolina. Aquat. Ecol. 46 (3), 269–282. doi: 10.1007/s10452-012-9398-8

Anderson D. M. (2012). HABs in a changing world: a perspective on harmful algal blooms, their impacts, and research and management in a dynamic era of climactic and environmental change. Harmful Algae. 2012 (3), 17.

Berg G. M., Balode M., Purina I., Bekere S., Béchemin C., Maestrini S. Y. (2003). Plankton community composition in relation to availability and uptake of oxidized and reduced nitrogen. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 30 (3), 263–274. doi: 10.3354/ame030263

Bouwman L., Beusen A., Glibert P. M., Overbeek C., Pawlowski M., Herrera J. (2013). Mariculture: significant and expanding cause of coastal nutrient enrichment. Environ. Res. Lett. 8 (4), 044026. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/044026

Briggs R. M., Funge-Smith S. J. (1994). A nutrient budget of some intensive marine shrimp ponds in Thailand. Aquac. Reaearch. 25 (8), 789–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.1994.tb00744.x

Brown A. R., Lilley M., Shutler J., Lowe C., Artioli Y., Torres R., et al. (2020). Assessing risks and mitigating impacts of harmful algal blooms on mariculture and marine fisheries. Rev. Aquac. 12 (3), 1663–1688. doi: 10.1111/raq.12403

Campbell B., Pauly D. (2013). Mariculture: A global analysis of production trends since 1950. Mar. Pol. 39, 94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.10.009

Cao L., Wang W. M., Yang Y., Yang C. T., Yuan Z. H., Xiong S. B., et al. (2017). Environmental impact of aquaculture and countermeasures to aquaculture pollution in China. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. Int. 14 (7), 452–462.

Cardoso-Mohedano J. G., Páez-Osuna F., Amezcua-Martínez F., Ruiz-Fernández A. C., Ramírez-Reséndiz G., Sanchez-Cabeza J. A. (2016). Combined environmental stress from shrimp farm and dredging releases in a subtropical coastal lagoon (SE gulf of California). Mar. pollut. Bull. 104 (1-2), 83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.02.008

Casé M., Leça E. E., Leitao S. N., Sant E. E., Schwamborn R., de Moraes Junior A. T. (2008). Plankton community as an indicator of water quality in tropical shrimp culture ponds. Mar. pollut. Bull. 56 (7), 1343–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.02.008

Castillo-Soriano F. A., Ibarra-Junquera V., Escalante-Minakata P., Mendoza-Cano O., Ornelas-Paz J. C., Almanza-Ramírez J. C., et al. (2013). Nitrogen dynamics model in zero water exchange, low salinity intensive ponds of white shrimp, litopenaeus vannamei, at colima, Mexico. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 41 (1), 68–79. doi: 10.3856/vol41-issue1-fulltext-5

Collos Y., Jauzein C., Ratmaya W., Souchu P., Abadie E., Vaquer A. (2014). Comparing diatom and alexandrium catenella/tamarense blooms in thau lagoon: Importance of dissolved organic nitrogen in seasonally n-limited systems. Harmful Algae. 37, 84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2014.05.008

Couch J. A. (1998). Characterization of water quality and a partial nutrient budget for experimental shrimp ponds in Alabama (Alabama, United States: Auburn University).

Danielsson Å., Papush L., Rahm L. (2008). Alterations in nutrient limitations — scenarios of a changing Baltic Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 73 (3-4), 263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.10.015

Davidson K., Gowen R. J., Tett P., Bresnan E., Harrison P. J., McKinney. A., et al. (2012). Harmful algal blooms: how strong is the evidence that nutrient ratios and forms influence their occurrence? Estua. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 115, 399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2012.09.019

Davidson K., Miller P., Wilding T. A., Shutler J., Bresnan E., Kennington K., et al. (2009). And prolonged bloom of karenia mikimotoi in Scottish waters in 2006. Harmful algae. 8 (2), 349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2008.07.007

Demirak A., Balci A., Tüfekci M. (2006). Environmental impact of the marine aquiculture in güllük bay, Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 123 (1), 1–12.

Díaz P. A., Álvarez G., Varela D., Pérez-Santos I., Díaz M., Molinet C., et al. (2019). Impacts of harmful algal blooms on the aquaculture industry: Chile as a case study. Perspect. Phycol. 6 (1-2), 39–50. doi: 10.1127/pip/2019/0081

Ding Y., Song X., Cao X., He L., Liu S., Yu Z. (2021). Healthier communities of phytoplankton and bacteria achieved via the application of modified clay in shrimp aquaculture ponds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (21), 11569. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111569

Dyhrman S. T., Anderson D. M. (2003). Urease activity in cultures and field populations of the toxic dinoflagellate alexandrium. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48 (2), 647–655. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.2.0647

Eusterhues K., Rumpel C., Kleber M., Kögel-Knabner I. (2003). Stabilisation of soil organic matter by interactions with minerals as revealed by mineral dissolution and oxidative degradation. Org. Geochem. 34 (12), 1591–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2003.08.007

Fan C., Glibert P. M., Burkholder J. M. (2003). Characterization of the affinity for nitrogen, uptake kinetics, and environmental relationships for prorocentrum minimum in natural blooms and laboratory cultures. Harmful Algae. 2 (4), 283–299. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9883(03)00047-7

FAO, (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2022). The state of world fisheries and aquiculture (SOFIA). Rome, Italy.

Froehlich H. E., Gentry R. R., Halpern B. S. (2018). Global change in marine aquaculture production potential under climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2 (11), 1745–1750. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0669-1

Gao Y. H., Yu Z. M., Song X. X., Cao X. H. (2007). Impact of modified clays on the infant oyster (Crassostrea gigas). Mar. Sci. Bull. 26 (3), 53–60. doi: 10.1002/cem.1038

Glibert P. M. (2016). Margalef revisited: A new phytoplankton mandala incorporating twelve dimensions, including nutritional physiology. Harmful Algae. 55, 25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.01.008

Glibert P. M., Burford M. A. (2017). Globally changing nutrient loads and harmful algal blooms: recent advances, new paradigms, and continuing challenges. Oceanography. 30 (1), 58–69. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2017.110

Glibert P. M., Burkholder J. M., Kana T. M. (2012). Recent insights about relationships between nutrient availability, forms, and stoichiometry, and the distribution, ecophysiology, and food web effects of pelagic and benthic prorocentrum species. Harmful Algae. 14, 231–259. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.023

Glibert P. M., Terlizzi D. E. (1999). Cooccurrence of elevated urea levels and dinoflagellate blooms in temperate estuarine aquaculture ponds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 (12), 5594–5596. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.12.5594-5596.1999

Gobler C. J., Berry D. L., Dyhrman S. T., Wilhelm S. W., Salamov A., Lobanov A. V., et al. (2011). Niche of harmful alga aureococcus anophagefferens revealed through ecogenomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (11), 4352–4357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016106108

Goldman J. C., Glibert P. M. (1983). Kinetics of inorganic nitrogen uptake by phytoplankton. Nitrogen Mar. Environ, 233–274. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-160280-2.50015-8

Griffiths J. R., Hajdu S., Downing A. S., Hjerne O., Larsson U., Winder M. (2016). Phytoplankton community interactions and environmental sensitivity in coastal and offshore habitats. Oikos 125 (8), 1134–1143. doi: 10.1111/oik.02405

Hagström J. A., Granéli E. (2005). Removal of prymnesium parvum (Haptophyceae) cells under different nutrient conditions by clay. Harmful algae. 4 (2), 249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2004.03.004

Han Q. F., Song C., Sun X., Zhao S., Wang S. G. (2021). Spatiotemporal distribution, source apportionment and combined pollution of antibiotics in natural waters adjacent to mariculture areas in the laizhou bay, bohai Sea. Chemosphere. 279, 130381. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130381

Hargreaves J. A., Tucker C. S. (2004). Managing ammonia in fish ponds Vol. 4603 (South Carolina, USA: Southern Regional Aquaculture Center Stoneville).

Hemingway J. D., Rothman D. H., Grant K. E., Rosengard S. Z., Galy V. V. (2019). Mineral protection regulates long-term global preservation of natural organic carbon. Nature. 570 (7760), 228–231. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1280-6

Herbeck L. S., Unger D., Wu Y., Jennerjahn T. C. (2013). Effluent, nutrient and organic matter export from shrimp and fish ponds causing eutrophication in coastal and backreef waters of NE hainan, tropical China. Cont. Shelf Res. 57, 92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2012.05.006

Hillebrand H., Steinert G., Boersma M., Malzahn A., Meunier C. L., Plum C., et al. (2013). Goldman Revisited: Faster-growing phytoplankton has lower n: P and lower stoichiometric flexibility. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58 (6), 2076–2088. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.6.2076

Huang S. L., Wu M., Zang C. J., Du S. L., Domagalski J., Gajewska M., et al. (2016). Dynamics of algae growth and nutrients in experimental enclosures culturing bighead carp and common carp: Phosphorus dynamics. Int. J. Sediment Res. 31 (2), 173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsrc.2016.01.003

Hu Z., Lee J. W., Chandran K., Kim S., Sharma K., Khanal S. K. (2014). Influence of carbohydrate addition on nitrogen transformations and greenhouse gas emissions of intensive aquaculture system. Sci. Total Environ. 470, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.09.050

Johansson N., Granéli E. (1999). Influence of different nutrient conditions on cell density, chemical composition and toxicity of prymnesium parvum (Haptophyta) in semi-continuous cultures. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 239 (2), 243–258. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(99)00048-9

Justić D., Rabalais N. N., Turner R. E., Dortch Q. (1995). Changes in nutrient structure of river-dominated coastal waters: stoichiometric nutrient balance and its consequences. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 40 (3), 339–356.

Kamp A., Hogslund S., Risgaard-Petersen N., Stief P. (2015). Nitrate storage and dissimilatory nitrate reduction by eukaryotic microbes. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1492. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01492

Lønborg C., Álvarez-Salgado X. A. (2012). Recycling versus export of bioavailable dissolved organic matter in the coastal ocean and efficiency of the continental shelf pump. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 26 (3), 1–12 doi: 10.1029/2012gb004353

Lacerda L. D., Molisani M. M., Sena D., Maia L. P. (2008). Estimating the importance of natural and anthropogenic sources on n and p emission to estuaries along the ceará state coast NE Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 141 (1), 149–164. doi: 10.1007/s10661-007-9884-y

Lai S. Y. (2014). The ecological aquaculture technique of prawn (Beijing (in Chinese with English abstract: China Agriculture Press).

Lepš J., Šmilauer P. (2003). Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press).

Li H. M., Li X. M., Li Q., Liu Y., Song J. D., Zhang Y. Y. (2017). Environmental response to long-term mariculture activities in the weihai coastal area, China. Sci. Total Environ. 601, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.167

Li J., Song X. X., Zhang Y., Xu X. X., Yu Z. M. (2019). Effect of modified clay on the transition of paralytic shellfish toxins within the bay scallop argopecten irradians and sediments in laboratory trials. Aquaculture. 505, 112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.02.038

Li H. M., Tang H. J., Shi X. Y., Zhang C. S., Wang X. L. (2014). Increased nutrient loads from the changjiang (Yangtze) river have led to increased harmful algal blooms. Harmful Algae. 39, 92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2014.07.002

Liu D., Keesing J. K., He P. M., Wang Z. L., Shi Y. J., Wang Y. J., et al. (2013). The world’s largest macroalgal bloom in the yellow Sea, China: formation and implications. Estuar 129, 2–10 doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2013.05.021

Lomas M. W., Glibert P. M. (1999). Temperature regulation of nitrate uptake: A novel hypothesis about nitrate uptake and reduction in cool-water diatoms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44 (3), 556–572. doi: 10.4319/lo.1999.44.3.0556

Lomas M. W., Trice. T., Glibert P. M., Bronk D. A., McCarthy J. J. (2002). Temporal and spatial dynamics of urea uptake and regeneration rates and concentrations in Chesapeake bay. Estuaries. 25 (3), 469–482. doi: 10.1007/BF02695988

Lou X., Hu C. (2014). Diurnal changes of a harmful algal bloom in the East China Sea: Observations from GOCI. Remote Sens. Environ. 140, 562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2013.09.031

Lu G. Y., Song X. X., Yu Z. M., Cao X. H. (2017). Application of PAC-modified kaolin to mitigate prorocentrum donghaiense: effects on cell removal and phosphorus cycling in a laboratory setting. J. Appl. Phycol. 29 (2), 917–928. doi: 10.1007/s10811-016-0992-3

Lu G. Y., Song X. X., Yu Z. M., Cao X. H., Yuan Y. Q. (2015). Effects of modified clay flocculation on major nutrients and diatom aggregation during skeletonema costatum blooms in the laboratory. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 33 (4), 1007–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00343-015-4162-2

Matsuyama Y., Shumway S. (2009). Impacts of harmful algal blooms on shellfisheries aquaculture. New Technol. Aquac. Elsevier 2009, 580–609. doi: 10.1533/9781845696474.3.580

McCarthy J. J. (1972). The uptake of urea by natural populations of marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 17 (5), 738–748. doi: 10.4319/lo.1972.17.5.0738

Meng W., Feagin R. A. (2019). Mariculture is a double-edged sword in China. Estua. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 222, 147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2019.04.018

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2020). The China fishery statistical yearbook of 2019.Beijing,China.

Miranda A., Voltolina D., Frías-Espericueta M. G., Izaguirre-Fierro G., Rivas-Vega M. E. (2009). Budget and discharges of nutrients to the gulf of California of a semiintensive shrimp farm (NW Mexico). Hidrobiológica 19 (1), 43–48.

Paerl H. W. (2006). Assessing and managing nutrient-enhanced eutrophication in estuarine and coastal waters: Interactive effects of human and climatic perturbations. Ecol. Eng. 26 (1), 40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2005.09.006

Páez-Osuna F., Álvarez-Borrego S., Ruiz-Fernández A. C., García-Hernández J., Jara-Marini M. E., Bergés-Tiznado M. E., et al. (2017). Environmental status of the gulf of California: a pollution review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 166, 181–205. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.01.014

Páez-Osuna F., Guerrero-Galván S., Ruiz-Fernández A., Espinoza-Angulo R. (1997). Fluxes and mass balances of nutrients in a semi-intensive shrimp farm in north-western Mexico. Mar. pollut. Bull. 34 (5), 290–297. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(96)00133-6

Páez-Osuna F., Piñón-Gimate A., Ochoa-Izaguirre M., Ruiz-Fernández A., Ramírez-Reséndiz G., Alonso-Rodríguez R. (2013). Dominance patterns in macroalgal and phytoplankton biomass under different nutrient loads in subtropical coastal lagoons of the SE gulf of California. Mar. pollut. Bull. 77 (1-2), 274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.09.048

Peñuelas J., Sardans J., Rivas-ubach A., Janssens I. A. (2012). The human-induced imbalance between c, n and p in earth’s life system. Glob. Change Biol. 18 (1), 3–6 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02568.x

Pinck L., Allison F. (1951). Resistance of a protein-montmorillonite complex to decomposition by soil microorganisms. Science. 114 (2953), 130–131 doi: 10.1126/science.114.2953.130

Ray A. J., Dillon K. S., Lotz J. M. (2011). Water quality dynamics and shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) production in intensive, mesohaline culture systems with two levels of biofloc management. Aquac. Eng. 45 (3), 127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2011.09.001

Santacruz-Reyes R. A., Chien Y. H. (2010). Yucca schidigera extract–a bioresource for the reduction of ammonia from mariculture. Bioresour. Technol. 101 (14), 5652–5657. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.127

Shumway S. E., Barter J., Sherman-Caswell S. (1990). Auditing the impact of toxic algal blooms on oysters. Environ. Auditor. 2 (1), 41–56.

SOA (State Oceanic Administration). (2017). Bulletin of China marine environment status in 2016.Beijing China

Song X. X., Zhang Y., Yu Z. M. (2021). An eco-environmental assessment of harmful algal bloom mitigation using modified clay. Harmful Algae. 107, 102067. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2021.102067

Sutton M. A., Bleeker A., Howard C., Erisman J., Abrol Y., Bekunda M., et al (2013). Our nutrient world. the challenge to produce more food & energy with less pollution. Centre Ecol. Hydrology.

Wang J., Cao J. (2012). Variation and effect of nutrient on phytoplankton community in changjiang estuary during last 50 years. Mar. Environ. science. 31 (6), 310–315. doi: 10.1007/s11783-011-0280-z

Wang J. N., Yan W. J., Chen N. W., Li X. Y., Liu L. S. (2015). Modeled long-term changes of DIN: DIP ratio in the changjiang river in relation to chl-α and DO concentrations in adjacent estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 166, 153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.11.028

Yang P., Lai D. Y., Jin B., Bastviken D., Tan L. S., Tong C. (2017). Dynamics of dissolved nutrients in the aquaculture shrimp ponds of the Min river estuary, China: Concentrations, fluxes and environmental loads. Sci. Total Environ. 603, 256–267. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.074

Yu Z. M., Song X. X., Cao X., Liu Y. (2017). Mitigation of harmful algal blooms using modified clays: Theory, mechanisms, and applications. Harmful Algae. 69, 48–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2017.09.004

Keywords: mariculture, dynamic variations, nutrient composition and structure, phytoplankton, modified clay

Citation: Chi L, Ding Y, He L, Wu Z, Yuan Y, Cao X, Song X and Yu Z (2022) Application of modified clay in intensive mariculture pond: Impacts on nutrients and phytoplankton. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:976353. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.976353

Received: 23 June 2022; Accepted: 04 August 2022;

Published: 23 August 2022.

Edited by:

Zhangxi Hu, Guangdong Ocean University, ChinaReviewed by:

Dajun Qiu, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaAndreas Seger, University of Tasmania, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Chi, Ding, He, Wu, Yuan, Cao, Song and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhiming Yu, enl1QHFkaW8uYWMuY24=

Lianbao Chi

Lianbao Chi Yu Ding1,2,3,4

Yu Ding1,2,3,4 Liyan He

Liyan He Yongquan Yuan

Yongquan Yuan Xihua Cao

Xihua Cao Zhiming Yu

Zhiming Yu