- Department of Applied Foreign Language Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Long recognized as a significant integrated task in major English proficiency tests, reading-to-write tasks have been researched from dimensions mainly concerning its testing validity. A further exploration into the process is essential for a better understanding of the construct and instructions of the integrated task in different cultural and educational contexts. The present study investigated the process of a response writing task by collecting data of interviews and reflective journals from 36 Chinese learners. These data were analyzed qualitatively to identify the main phases and sub-stages occurring in the reading-to-write process. The results disclosed three main phases: pre-reading, reading for writing, and writing from reading. Besides, among a set of sub-stages, planning and rereading recurred and were embedded with each other in the main phases, and therefore, bridged reading and writing. The purposes of the occurrence of the main phases and recurring sub-stages presented the dynamic agency that learners exercise. Accordingly, a new model was constructed to account for the nuanced processes as well as their connection and interaction in a reading-to-write task, providing new insight into the recursive and reciprocal nature of reading-to-write tasks for learners in the Chinese context and furthermore, into the construct of integrated academic tasks. Pedagogical suggestions for L2 learners were provided in the end.

1 Introduction

The integration of reading and writing skills has been universally employed in language proficiency tests of different kinds all over the world, particularly since TOEFL iBT incorporated integrated writing (reading-listening-writing) into its writing section (Ascención, 2004; 2008; Cumming et al., 2005; 2016; Plakans, 2008; Plakans and Gebril, 2012, 2013; Wette, 2018; Xie, 2023). For performing the sourced-based integrated writing, writers need respond to what they have read or listened to. This task type is considered to resemble what test takers will encounter in their future academic settings in addition to the test-oriented purposes (Cumming et al., 2005).

The enquiries concerning the integration of reading and writing in the abovementioned reading-to-write tasks, for example, conceptualization of task construct, validity of test item, and the discourse features of written products (Ascención, 2004, 2008; Cumming et al., 2005; Esmaeili, 2002; Wanatabe, 2001), promoted the attention to probing into its process. In a few attempts at constructing models of reading-to-write tasks in the L2 research, efforts have been made to investigate the main phases, the recurrence of source reading behavior, and potential shared processes covering both reading and writing (Plakans, 2008; Plakans et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the endeavor mainly focused on the written products or the recurrence of source reading in the writing phase, or reading and writing strategies employed to assist the task performance. A detailed process that could precisely disclose the recursive and reciprocal nature of reading-to-write task has not been caught nor presented.

Most of such studies have been conducted in the countries where the English language resides a dominating position. It is unclear whether learners from different cultural and educational background undergo similar processes and share similar experiences (Cumming et al., 2018). Unsurprisingly, there is a lack of research in the relevant field in the Chinese context (Pan and Lu, 2023), whose learners have long received English instructions separating reading from writing. They tend to write from personal experience, generate ideas from Chinese translation, and organize their essays following the conventional practices in their native language. This is not how English academic writing takes place in real life. As a result, the Chinese learners would encounter great challenges when engaged in English writing tasks for academic purposes. Leki (1993) points out “reading builds knowledge of various kinds to use in writing” (p. 10). Content support plays an important role to assist writers in constructing their own essay writing (Jung, 2020). Exploring what resources Chinese learners will rely on and what assistance instructors can offer in the process of reading-to-write tasks may shed light on future research in this domain.

The research into the process of reading-to-write tasks has undergone the initial concern about roles of reading, attention to the interactions between reading and writing, model construction, and to what extent the two acts shape each other so that the writers are able to accomplish their eventual source-based written products (Ascención, 2004; Plakans, 2009a; Plakans et al., 2019; Wanatabe, 2001).

Since the addition of reading to the writing section of TOFEL iBT, to what extent reading can affect the outcome of reading-based writing has gone under heated discussion. Several studies found out that the roles of reading in writing cannot be underestimated. It is not surprising that writers with better comprehension of source readings produced writings with higher quality not only in terms of conventional criteria for assessing independent writing, like grammatical accuracy and syntactic complexity, but also with respect to integration amount and quality of the source passages (Cumming et al., 2005, 2006). In her doctoral dissertation, Esmaeili (2002) conducted an exploratory study to investigate whether the content knowledge in the source reading had an impact on the processes and products of a reading to writing task and discovered that writers reading thematically relevant passages produced essays of better quality than those who read those not thematically relevant to the written tasks. She concluded that reading and writing processes could not be separated from each other; more importantly, the thematic connection between the reading passages and writing tasks contributed to students' writing performance. Jung (2020) also found that lack of content support significantly increased the task complexity of reading-to-write as writers reported greater task demand and paused longer at the level of sentence writing according to the keystroke logging.

Some other studies found less considerable power of reading in reading-to-write tasks. In an analysis of the writers' performance on a reading-to-write task, Wanatabe (2001) found writing could better predict writers' performance compared to reading; what's more, the impact of reading on writing had better be attributed to writers' overall proficiency level rather than comprehension ability. Ascención (2004) also discovered low correlation between reading ability and the scores of summary and response writing—two different types of reading-to-write tasks.

Reading at different levels for different purposes may also play roles of different kind. Khalifa and Weir (2009) contended that among the four types of reading processes (local vs. global, careful vs. expeditious), expeditious reading best facilitated reading-to-write task performance for its efficient and accurate location of the needed source information. Due to the limited language competence of L2 writers and the needs and demands generated by their cultural and educational settings (Grabe and Zhang, 2013), the presence of reading may pose unique challenges to their performance of a reading-to-write task. Plakans (2009b) reported that those weak at reading comprehension did have difficulty synthesizing the source reading and responding appropriately in their own writing.

Complicated and controversial as the role of reading is in the process of reading-to-write, it cannot be completely ignored for the acts of reading and writing co-occur and reshape each other in an integrated task type.

The connection and interaction between reading and writing have been long acknowledged since the last century. It is believed that both of them are “essentially similar processes of meaning-construction” (Tierney and Pearson, 1983, p. 568). The reading-to-write process has been considered recursive and reciprocal (Flower, 1990) as the social constructive view contends that in such tasks, the boundaries between reading and writing are “permeable” and therefore, blurring (Nelson, 1998). A clearcutting line between reading and writing is almost impossible in reading-to-write tasks.

Following the constructivist view of reading and writing connection (Spivey, 1990), some researchers made careful observations and thorough analysis on how learners read for the purpose of writing. Greene (1992) coined a term “mining” (p. 151), which he interpreted as a metaphor for “understanding how writers read purposefully and intently in order to develop a store of discourse knowledge that they can use to achieve their goals in composing” (p. 155). According to the students' think-aloud data, specific strategies employed in the process of mining the texts included text reconstruction, structural inference and imposition, and language selection. Greene commented that the process of mining suggested, on the one hand, the activeness of writers to take control of their own text construction; on the other, reading sources offered a “mine” or a “bounce off” springboard (Jolliffe, 2007). Writers took the miner-like reading process to prepare for their text construction. Murrey (1991) proposed a similar term “reading writer” and explained that reading writers read everything—from the lexical level to structural level—about the whole text, which was a complicated process involving all the possible elements of writing (p. 142). Hirvela (2004) distinguished miner writers and reading writers in that when the former read with specific purposes serving a subsequent writing task, the latter would stand in the shoes of the original writer, predicting, thinking, and evaluating as if he or she were producing the same piece. Either type of readers as well as writers underwent both reading and writing as meaning-composing processes; in a word, they were doing “writerly reading” (Hirvela, 2004). An individual engaged in reading-to-write tasks acquires a dual identity, a reader as well as a writer, borrowing meaning from others' writing and contributing meaning to others' writing.

Along the same vein, writing also helps shape reading. McGinley (1992) pointed out in his study investigating the role of reading, writing, and reasoning based on the data of a composing-from-multiple-sources task that essay composing engaged a number of interrelated sub-processes, including formulating and articulating thoughts and arguments, and making decisions on specific ideas. Note-writing was considered very significant because it helped with planning and organizing ideas, building an “intermediate text” in its own as a foundation for the subsequent reshaping or adjusting of ideas and information from the reading sources. He cautioned oversimplistic description of source-based composing process as being linear or non-linear, but argued for a largely recursive process in terms of reading, writing, and reasoning (p. 241).

As the nature of reading-to-write process has been controversial, a number of attempts have been made to explore the process of such task types so that a clearer picture of reading-writing relations could be disclosed. In a case study in which six secondary students were required to write a research report on the basis of several source passages, Lenski and Johns (1997) reported three patterns of reading-to-write processes: sequential, spiral, and recursive. The process pattern was decided by how they understood the task type. Only the student following a recursive pattern produced a report integrating information from the source texts whereas the other two submitted summaries and paraphrases. More recently, Solé et al. (2013) asked 10 last-year secondary students to write a synthesis based on three history texts and also discovered different patterns to undergo the reading-to-write task: linear/reproductive (with the lowest level of integration), linear/elaborative (with some source text integration) and linear/elaborative plus some elements of recursiveness (the most successful type of source integration). What is most notable is that in the pattern that presented recursiveness of reading and writing, rereading was discovered to be frequently employed in the process for various purposes. In addition, planning and revision were also found to be significant to impact both the recursiveness of the process as well as the quality of the ultimate written products. It can be concluded that whether the process of reading-to-write presents the interactive and recursive nature may depend on the competence and experience of the writers.

In the L2 context, the prerequisite that has to be taken into consideration is the limited language proficiency and literacy skills of writers. That is why the process of reading-to-write in L2 has been discussed and explored in terms of challenges rather than support (Grabe and Zhang, 2013).

The empirical studies on the L2 reading-to-write process were rooted in the L1 constructive model of discourse synthesis (Spivey and King, 1989, Spivey, 1990). Following the three major processes in discourse synthesis writing Spivey (1990) elaborated on, organizing (“organize textual meaning”), selecting (“select the textual content for the representation”), and connecting (“connects content cued by the text with content generated from previously acquired knowledge”) (p. 254–257), Plakans (2009b) discovered two additional processes according to the think-aloud data of her L2 student writers in a response essay writing task based on two source texts, monitoring and language difficulties. Monitoring was employed by students to “consider the topic, evaluate own writing, and express affect” while language difficulties emerged when they selected vocabulary, translated from their native language and made decisions on syntactical issues. Apparently, Spivy's discourse synthesis processes are those mostly taking place before writing whereas the newly-discovered L2-specific processes concern the students' need for the written task, their lack of competence with the target language, and their insufficient practice with the task type. It might be true that L2 writers face bigger challenges compared to their L1 counterparts in the academic settings where reading-to-tasks are essential.

When conceptualizing the construct of reading-to-write, Ascención (2008) cautioned the interpretation of the task nature, rather than linear, the process should be viewed as a reciprocal interaction between the two literacy skills. Plakans (2008) partially acknowledged the reciprocity of the process. In her working model of reading-to-write tasks based on the think-aloud data from L2 students, the interaction between source reading and the response writing was only recognized in the “writing phase”; the “preparing to write” phase, where the processes of brainstorming, reading and planning occurred, was depicted to be linear. Due to such a complication, besides reading and writing, there could be other types of competence required for such an integrated task. McCulloch (2013) sharply pointed out that most L2 studies in this field underrepresented the needs of L2 writers for they generally completed such tasks in one sitting, which definitely led them to employ strategies entailed by exam-oriented topic-based writing tasks. The lab-like setting could not show authentic processes the L2 writers have undergone. By employing a structural equation approach, Yang and Plakans (2012) discovered that integrated writing (in their study, a reading-listening-writing task) was demanding in that in addition to discourse synthesis strategies and test-related strategies, students also needed to activate their self-regulatory mechanism for completing the integrated task. The educational, cultural, and contextual factors have to be taken into consideration at the same time.

In a number of processes frequently employed by L2 writers for reading-to-write tasks, monitoring and rereading are the ones thoroughly described and discussed. Monitoring has been reported as an important operational process of reading-to-write tasks in quite a few studies (Ascención, 2004; Plakans, 2009a,b; Yang and Plakans, 2012). It was discovered that monitoring often emerged when writers set up goals, make decisions and generate plans. Rereading, as an essential process preparing writers for further planning of the subsequent writing, cannot be absent if they hope to produce a final product living up to the task requirements (Plakans, 2009a; Plakans et al., 2019; Delgado-Osorio et al., 2023). In the exploration of reading roles in integrated tasks, Plakans (2009a) discovered the two most frequently employed strategies were rereading and metacognitive strategies. Rereading occurred on both lexical and content level, and spanned the processes of reading, writing and revision. Metacognitive strategies were employed to monitor both comprehension check and the need of “mining” (Greene, 1992). It was also found that during strategic processing of summary and argumentative writing, two different types of reading-to-write tasks, rereading played the role of source selection in the phase of reading and that of information confirmation in the phase of writing; monitoring, recognized as the major metacognitive strategy, mainly served checking the accuracy and relevance of source uses and appropriateness of source citation (Delgado-Osorio et al., 2023). In a qualitative study (Plakans et al., 2019), a newly designed iterative integrated task was employed to investigate which processes might be shared by both reading and writing. Among the five identified shared processes, rereading and monitoring were the only two recurring in all the phases of reading, writing and revision. Explicit instructions on how to fit the two strategies into the process of reading-to-write are essential and critical for L2 writers to achieve better academic performance.

Unfortunately, the above introduced processes and strategies have not been clearly presented in the existent descriptive models of reading-to-write. In the L1 context, Spivey (1990) described the three-step discourse synthesis processes, not giving consideration to the needs of L2 writers, let alone other socio-cultural issues. The L2 model of reading-to-write tasks (Plakans, 2008) laid its emphasis on the differences between topic-based independent writing and integrated writing. The segmentation of the “preparing to write” and “writing” phases as well as its corresponding sub-processes oversimplified the needs, behaviors and process of L2 reading-to-write tasks.

Not much has been explored into the L2 reading-to-write tasks in the Chinese context (Cumming et al., 2016, 2018; Pan and Lu, 2023). Students in China have not enough exposure to and practice in integrated writing tasks in their English classrooms. It is challenging for them to naturally and spontaneously apply what they have learned from reading instructions, linguistically as well as rhetorically, to their written practices. Nevertheless, the ability to produce successful reading-based writing was indispensable for L2 learners in academic settings (Grabe, 2003; Grabe and Zhang, 2013). It is pressing for them to acquire basic processing skills of reading and writing for such a task type. In addition, other factors that may coordinate with their literacy skills should also be taken into consideration.

The present study intends to explore the major phases and the corresponding sub-stages in the process of a response writing task (responding to source reading and eventually, write a response essay), contributing empirical data to the field of L2 integrated writing in the Chinese context; in addition, this study attempts to build a new model of reading-to-write tasks. The following research questions will be addressed:

• What process do Chinese English learners undergo in a reading-to-write task, a response essay writing?

1) What phases do they undergo when writing a response essay?

2) What sub-stages are embedded in the phases when they write a response essay?

2 Materials and methods

The present study employed a task design that might elicit integration and responsive argumentation, aiming at exploring the processes of a reading-to-write task. The data bank consists of source texts, response essays, reflective journals, and a post-task interview of a few randomly invited participants. The analysis of the data, mainly the interview and reflective journal data, was carried out by the researcher and a co-rater through multiple coding sessions and discussions.

2.1 Participants

Thirty-six non-English majors from a key university in China participated in the present study. They were attending an academic writing course taught by the researcher in the second semester of the freshmen year at the time of data collection. The course aimed at helping students acquire and practice basic skills of academic English essay writing. Argumentative essay writing was the central content of the course. Inevitably, the fundamental knowledge about critical thinking was also introduced and practiced. Upon receiving the task in the present study, the participants had already practiced writing multi-drafted argumentative essays after reading about relevant issues over a period of approximately 3 months. They had been learning how to establish a clear position on a selected issue and support the point of view with appropriate and sufficient evidence. Nevertheless, they had not experienced producing response writings with time constraints in a test condition.

In the semester prior to the writing course, all the participants attended a reading and writing course with the focus mainly on reading comprehension practice for students of high intermediate level (decided by a placement test upon entering the university). Over 18 years of age, having received relatively high-quality secondary education, with exposure to a number of readings and practices of a few topic-based college English writing assignments, these participants were believed to be mature and competent enough to generate ideas on the issues selected for the current study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

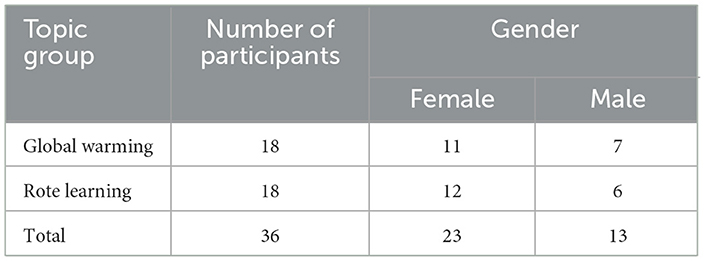

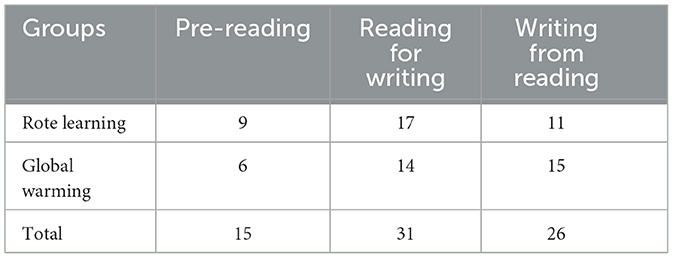

Table 1 provides the basic information of the participants based on the topic groups they were allocated to. They took the reading-to-write task as part of the end-of-the-semester practice.

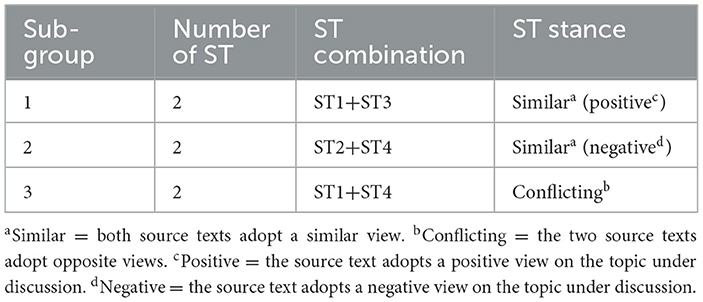

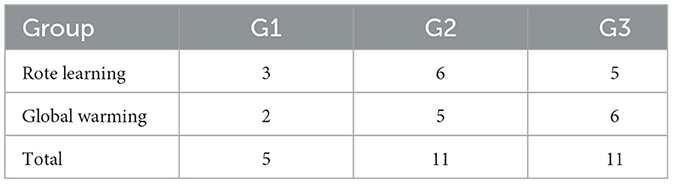

The participants were evenly divided into two topic groups. Half of them wrote about global warming; the other half, rote learning. Within each topic group, the participants were further divided into another three sub-groups according to three different combinations of source reading materials (see Table 2).

2.2 Instruments

The instruments employed in the present study include response writing task prompts, 8 source reading passages, questions for an immediate follow-up interview and requirements for a reflective journal after the writing task.

2.2.1 The response essay writing task

Before the participants received the source texts, the writing prompts in Chinese (see Appendix A) were handed out so that they could have a separate period of time (5 min) from the actual reading and writing task for concentrating on understanding the task requirements. They were also required to give their own opinions on the topic immediately after reading the prompt (the design here was intended for another study closely related to the present one).

The response essay writing task consisted of two steps: source texts reading and writing a response essay accordingly. The participants from different sub-groups were assigned different combinations of source texts depending on their viewpoints on one of the topics: rote learning and global warming. The task design partially followed the integrated writing section of TOFEL iBT (Bider and Gray, 2013; Cumming et al., 2005, 2006) and those tasks from a set of studies researching different dimensions of integrated writing (Ascención, 2004, 2008; Gebril and Plakans, 2013; Plakans, 2008, 2009a,b; Plakans and Gebril, 2012).

Following the above design, the participants read the source texts on paper, and then, wrote the response essays on www.pigai.org (an online writing platform). Each of them was assigned two source texts on one topic (see Table 2). They were also required to mark the parts on the original source reading sheets that they would use in their own response essays.

2.2.2 Source texts

Eight source texts on two topics were employed in this study (see Appendix D), four for each topic, among which two hold positive view and the other two, negative. The source texts were adapted from original English news articles, magazine articles, and blogs with approximate length (550–800 words each) and difficulty level (Flesh Reading Ease 43.2–55.2).

Both the source texts and the task procedures had been piloted together with another two texts among a different group of participants from the same proficiency level but different writing classes beforehand. Among the four topics, global warming was selected for the students showed concern about it while rote learning was a familiar learning approach to the Chinese students from their experience.

In the context of the present study, in addition to difficulty level, how convincing the source texts were also had an impact on the viewpoint decision of the participants in their own response essays. Hypothetically, the participants might follow the opinions of the better supported arguments in the source texts whereas they would abandon those less sufficiently justified. The assessment of the argument power of the source texts was carried out by two experienced teachers from the same department, following an adapted version of Toulmin model (Qin and Karabarak, 2010; Stapleton and Wu, 2015). They scored these source texts based on 6 frequently employed elements of argumentation to assess the argument power of the source texts: claim, data, counterclaim, counterclaim data, rebuttal claim, and rebuttal data. These elements were taught and practiced in the writing courses taken by the participants. Table 2 presents the combination of the source texts.

2.2.3 Interview

A semi-structured follow-up interview (See Appendix B) was administered in Chinese immediately after the participants completed their response writing task. Two participants from each sub-group were invited for the interview, i.e., 12 in total from all 6 groups. Chinese, their native language, was employed in order to reduce their anxiety and hence better idea expression and retrieval. During the interview, the marked source texts and the written texts of the participants were placed aside to help them recall, specify and clarify their writing and thinking. The session for each interviewee lasted for 10 to 15 min, and was completely recorded with their consent.

The semi-structured interview stimulated by open-ended questions was employed for tapping into the participants' memory (both short-term and long-term) and metacognition of their decisions and behaviors in the process (Ruiz-Funes, 1999a). With the presence of the marked source reading passages and written texts of the interviewees, the interview could elicit as much data as possible on the interactive and decision-making processes (Hyland, 2013, 2016). Twelve interview questions were designed centering around the following three aspects: (1) the major phases they underwent as well as the corresponding sub-stages in each phase; (2) metacognitive thinking over how the acts of reading and writing interacted with each other; (3) the specific decisions they made in different phases or sub-stages as well as reasons for such decisions.

2.2.4 Reflective journal

In 2 days after the writing task was completed, all the participants were required to submit a reflective journal with guided questions (See Appendix C) as a homework assignment. Reflective journals were employed to collect further data of all the participants on how they processed and performed the response writing task. Although there could be a loss of memory on what was going on at the time of task performance, retrospection and reflection in written form not a long time afterwards and without intruding into the reading-to-write process, like think-aloud protocol or video taking, may help push a rich and reliable recall of thinking process hard to be accessed by other means (Hyland, 2016). The directions and guided questions (see Appendix C) of the reflective journal were provided on the online writing platform (www.pigai.com) in Chinese. The participants could choose to write the journal either in English or in Chinese. The guided questions of the journal were similar to those examined in the interview. The journal content was going to be triangulated with the interview data and the participants' written texts.

2.3 Data collection

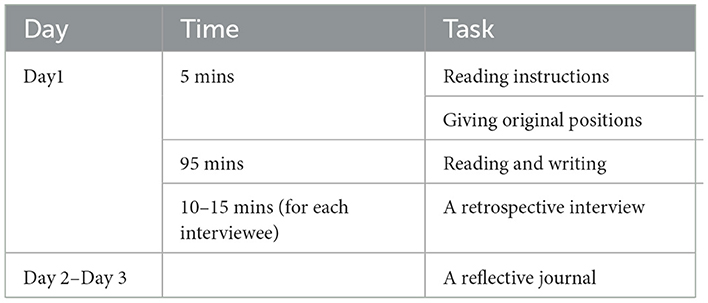

The data were collected in 3 days, as shown in Table 3.

In normal class time (100 min altogether) on the 1st day, the participants performed an in-class reading and writing task. Before the source texts were distributed to the participants, they each received a piece of note paper on which they read the task instructions in Chinese and they were required to write down their viewpoint on the relevant topic in a designated place. The note paper was collected in 5 min. Afterwards, each participant was assigned two source texts according to their grouping. During the next 95 min, the participants read their source texts on paper and wrote their response essays on the online writing platform, www.pigai.org. They were also required to mark the parts of the source texts that they planned to use in their own response writing. No other intervention disrupted their reading and writing acts. In order to catch the fresh memory and process of task completion without being obtrusive, an immediate face-to-face retrospective interview was conducted by the researcher herself. Two participants from each sub-group (six sub-groups from two topic groups), thus twelve in total, were randomly invited to receive the interview. With the consent of the interviewees, their talks were recorded. The interview was carried out in Chinese so that the interviewees felt at ease and more comfortable to share what they had thought about, behaved, and experienced during the task. In addition, all participants were required to write a reflective journal based on some guided questions about how they performed the reading-based response writing task in 2 days. The journal instructions and questions were provided in Chinese. They could choose to produce the journal either in Chinese or in English so that they could better express their ideas.

2.4 Data analysis

Data were analyzed following qualitative coding of the participants' reported acts of reading and writing according to their interview and reflective journal content. The researcher and another rater, also an experienced English teacher from the same department, went over all interview transcripts (from 12 randomly invited participants) and reflective journals (of all 36 participants). For the convenience of coding, the terms of phases and sub-stages were borrowed from previous process-oriented studies on writing (Flower and Hayes, 1981; Plakans, 2008), for example, planning, drafting, and revising.

The researcher and the rater did the coding in an Excel file so that each phase, sub-stage as well as the corresponding original text pieces from the interview transcripts or reflective journals could be well organized. Considering the necessity to check back any detail when needed, they also drafted a memo for each participant summarizing the prominent features in the process of task performance.

During the first round of coding, they randomly picked 4 sets of interview data and 6 reflective journals from both topics and worked together to tease out the major phases and sub-stages emerging in the data. The segmentation was carried out according to what the participants reported about their acts and reasons of the acts. Due to the task design, the researcher and the rater quickly agreed upon the segmentation of the main phases and some of the obvious sub-stages.

During the second round of coding, they worked independently on the rest of the interview data and reflective journals following the decided items and notes in the Excel files from the first round. When they discovered a new sub-stage, or one they had difficulty deciding its type, they would take note of it. The inter-rater reliability then was 84%.

In the end, they met with each other for discussing all the unresolved issues, mostly about sub-stages included in a main phase (for example, it was planning or rereading in the reading for writing phase). All puzzles and problems were resolved by such face-to-face discussions.

3 Results

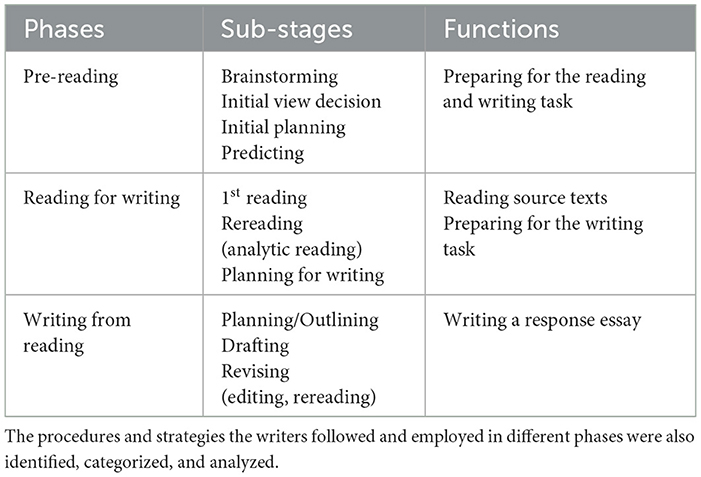

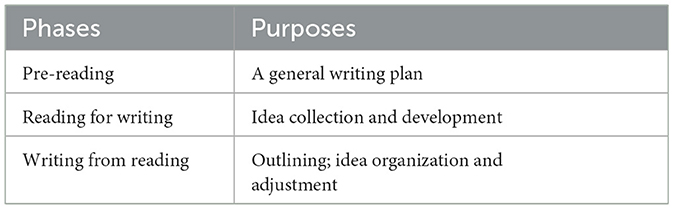

The major phases identified include the following three: pre-reading, reading for writing, and writing from reading. Table 4 presents a list of the functions of each phase and their sub-stages.

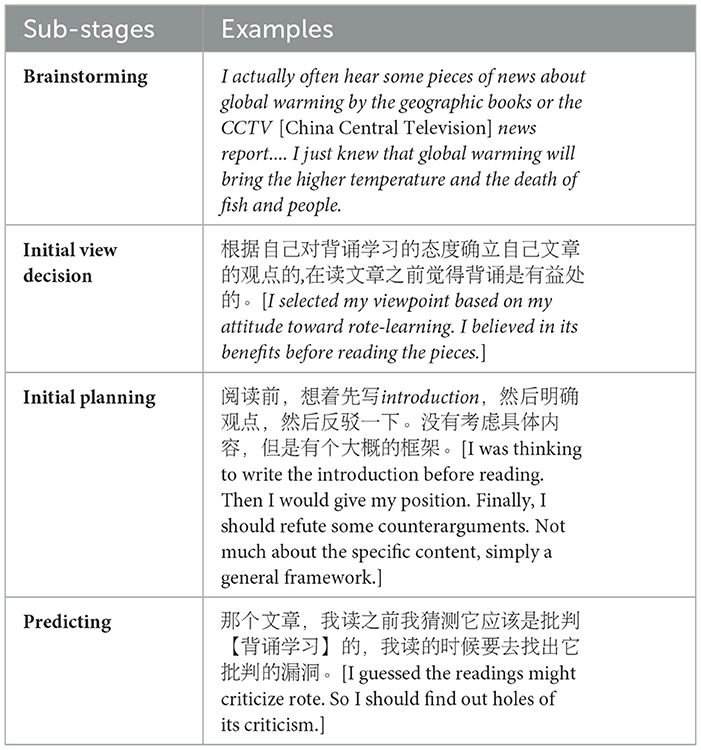

3.1 Pre-reading

Due to the task design, the pre-reading phase was compulsory during which the participants did more than reading the instructions; they were also quested about an opinion on the topic. In the meantime, they spontaneously started brainstorming relevant information and ideas from their memory, did some planning for the response essay, and some even predicted the view or content of the source texts. Therefore, the pre-reading phase includes the following sub-stages: brainstorming, initial view decision, initial planning, and predicting (see Table 5 for the examples).

These sub-stages did not necessarily occur following a fixed sequence; they were embedded with one another.

Almost all of the participants reported an immediate and detailed brainstorming process after understanding what they were going to do according to the interview and reflective journals. Topic familiarity played a role in what they brainstormed. With rote learning, a familiar topic for the Chinese participants, they went beyond gathering information; they directly shared experience and presented positions on the controversial learning approach. In contrast, global warming writers, less familiar with the issue, mostly retrieved information from what they had covered in their native language readings (Wang and Wen, 2002).

At the required stage of initial view decision, 17 out of 18 participants from the rote learning groups chose to support beneficial effects of the learning approach; only one student believed it to have short-term effects on learning outcome, not in the long run. All the 18 participants of the global warming groups unanimously agreed that global warming does exist.

Some writers started planning for their own response essays in the pre-reading phase. Half of them (9) from the rote learning groups explicitly claimed that they set out to plan for their own writing; and one-third (6) from the global warming groups did so, too.

Though not many, some participants from both topic groups made predictions about the source views and content. Four from the rote learning groups predicted about the source texts and 3 from the global warming groups did so. What they predicted was mainly concerned with the view inclination of the source texts, the possibility of their later change of position, and helpful reading and writing strategies they would employ.

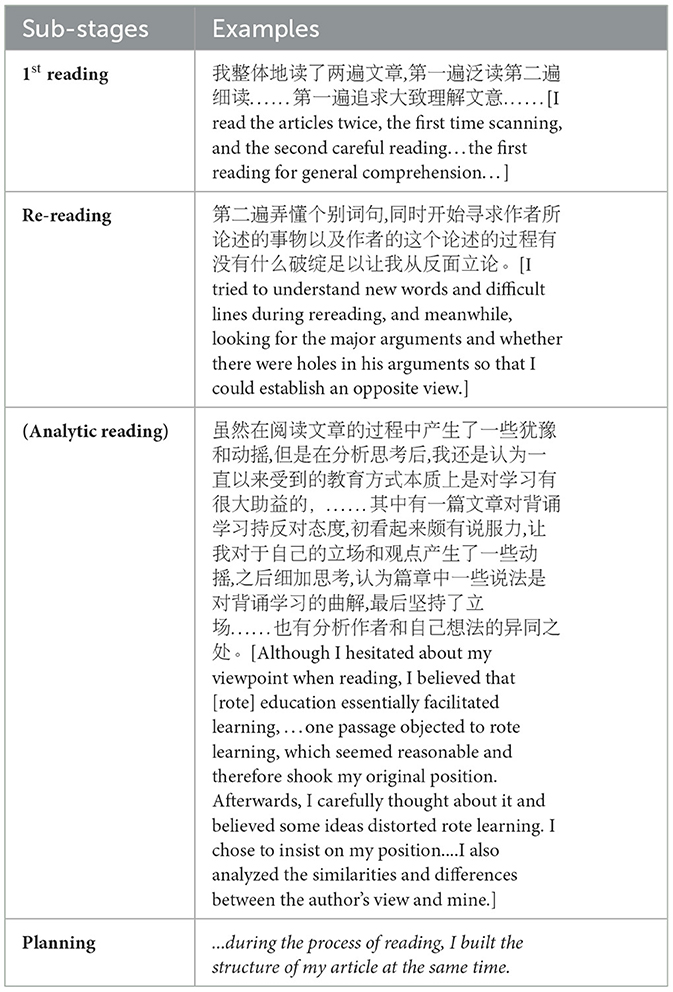

3.2 Reading for writing

The reading-for-writing phase in this study presented a dynamic picture during which basic comprehension was not the sole purpose; instead, the writers employed more strategic approaches to processing the source texts for accomplishing the ultimate writing task. The sub-stages (see Table 6 for the examples) identified in this phase include: first reading, re-reading, and planning. Re-reading, where the writers dug into and analyzed the source texts, co-occurred with planning.

Most participants claimed at least reading the source texts twice, of which the first time was devoted to basic comprehension and viewpoint identification and the second time was used beyond a reading comprehension purpose. The major purposes of re-reading included searching for valuable information they could use, what ideas or viewpoints they could challenge and refute, and meanwhile further planning accordingly for the response essay.

During the re-reading stage, besides further exploring into the source texts, some writers read the passages analytically, especially those who were exposed to views and ideas unfamiliar to them or conflicting with what they used to believe in. As Group 2 and 3 from both topics were given passages with such texts whereas Group 1 dealt with positive opinions only, more participants from G2 and G3 were engaged in analytical reading than those from G1 (see Table 7).

Reading the opposing views and ideas of the source texts, Group 2 and 3 writers generally underwent a process of confusion and hesitation:

Those two passages, however, confused me to some degree.

I was wavering about the view position during reading.

Their solutions to getting out of the dilemma were to further analyze the source texts, check the specific evidence and logic, assess the argument quality, and compare with their own experience and understanding of the issue. Those involved in analytical reading accounted for their confusion, hesitation, analysis, and final decisions in the interview and reflective journals.

I thought about the opinions of the writers and compared them with my own opinions, tried to figure out at what point I share the same idea with the two articles and at what point I have different ideas.

I was afraid their views were too radical, so inappropriate. I exercised my critical thinking and checked the quoted research findings and logical analysis. I found they are substantial and convincing.

Apparently serving the ultimate writing, and having thought about and collected the information and ideas, planning was natural for most writers during the phase of reading for writing. Seventeen out of 18 writers from the rote learning groups and 14 out of 18 from the global warming reported that they deliberately planned for their own essay writing across the sub-stages of reading for writing.

I mainly looked for the content relevant to my own viewpoint when reading. I read the articles with clear purposes, in other words, I was thinking about my own writing when reading.

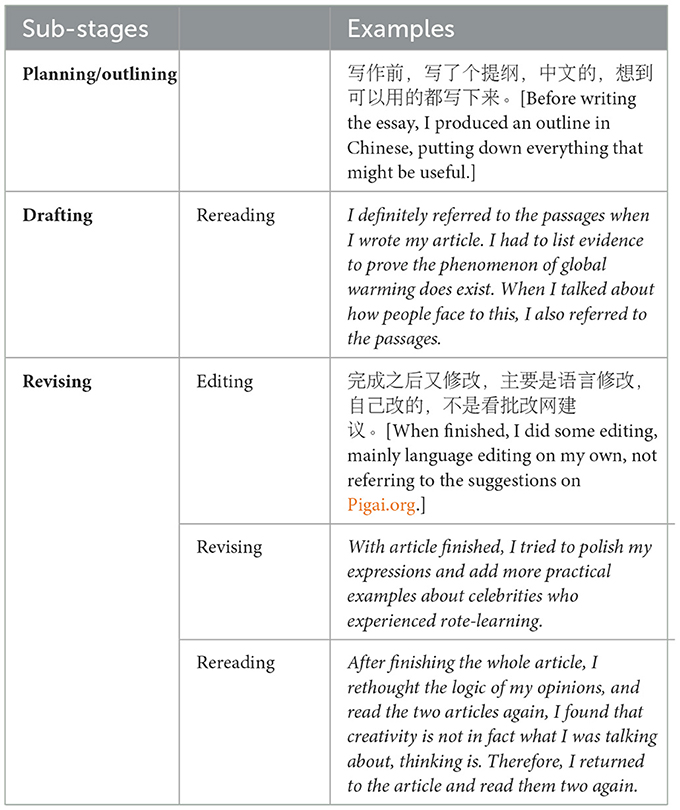

3.3 Writing from reading

The cutting line between the reading-for-writing phase and writing-from-reading phase was indistinguishable. Not very different from topic-based writing, the following sub-stages were identified: planning/outlining, drafting, and revising (see Table 8 for the examples). The writing act emerged in as early as the pre-reading phase as many participants started conceiving their writing plans before reading the source texts; such planning for writing permeated the task process until they started drafting the response essay. Nonetheless, the thoughts over planning were constantly interrupted during pre-reading and reading, for example, by a need to check a new word in a dictionary, or one to assess the validity of a piece of evidence. Eventually, it was time for the writers to concentrate solely on the essay writing in the current phase.

Planning, or a better term at this moment, outlining, was prevalent among the writers. From both topic groups, almost all reported in the interview and reflective journals that they either produced a written outline or one in their mind.

Before writing, I planned three paragraphs for my essay. And I prepared evidence for each paragraph.

The outline was right in my mind. But I did not write it up. I knew where to find the evidence from the reading passages.

Not much was reported about how the writers put down each line of their essays; however, rereading was mentioned by almost all of them, mainly for the following four purposes: ensuring that the highlighted information or ideas were not mis-quoted or misrepresented; further mining new information or ideas; rereading some lines to press further thinking; seeking language help.

When I was not sure about the information, I would go back to reading.

When I was stuck in the process of writing, I also rescanned the passages to seek further inspiration.

When I hesitated about the structure [of my essay], I went back to the underlined parts to look for breakthroughs.

Clearly, planning went together with rereading during the sub-stage of drafting. the writers' metacognition about writing functioned at this stage, facilitating the development of the essay writing.

The act of revising was rare as many participants complained about the shortage of time. Most of them reported doing surface-level editing. Among a couple of writers who did find time rethinking about their written work, they reread the source texts, prompted by the need of revision.

I did some content revision, that is, adding something…. When I added the point, I surely went back to reread the passages.

4 Discussion

The above exploration of the major phases as well as the corresponding sub-stages led to the disclosure of the following compelling dimensions of source-based writing in the context of the present study. The phases of reading and writing could be hardly separated from each other. The integration skills were mostly present in the sub-stages. The very two sub-stages, rereading and planning in particular, made prominent contributions to revealing the reciprocal interaction between the phases. In addition, the participants exercised their leaner agency in the process of the reading-to-write task. The following discussion of these dimensions in light of the findings may shed light on both the construct and instructions of L2 integrated writing.

4.1 The inseparable phases of reading for writing and writing from reading

The inseparability of reading and writing phases permeated the whole process of the reading-to-write task (Chaffee, 1985; Flower and Hayes, 1985; Grabe, 2003; Nelson, 1998; Spivey, 1990). At the very beginning of pre-reading phase, an intentional task design for a detection of the writers' initial view decision, they started away with a set of preparatory acts beyond simply “reading task prompt and instructions” in the “pre-writing” phase according to Plakans (2008)'s working model of reading-to-write tasks; moreover, writers also brainstormed ideas, predicted about the source reading, and made preliminary plans for the response essay. Brainstorming and planning are typical preparations for writing tasks while predicting about the source reading is a natural step before the reading phase. The skill integration of reading and writing naturally occurred from the very start, which could be attributed to the hybrid nature of the reading-to-write task (Spivey, 1990) as well as the agency of L2 writers activated by their previous knowledge and experience (Fitzgerald and Shanahan, 2000; Flower and Hayes, 1980).

If the pre-reading phase was a prelude to the whole process, the inseparability of the actual reading and writing phases was obvious for the distinct purposes of both phases and hence, the roles and identity of the writers.

The purpose of reading in the present study went beyond comprehension though comprehension was the first step and basis of the latter ones. As source reading was targeted at the ultimate response writing, the reading phase was loaded with writing purposes which turned out to be “writerly reading” (Hirvela, 2004; Smith, 1983; Spivey and King, 1989) during which readers actively mined for support from the source texts (Greene, 1992; Hirvela, 2004) as most of them typically did so in their rereading stage (Solé et al., 2013). When writers “mined” or read to integrate, they interpreted the source texts semantically as well as rhetorically (Trites and McGroarty, 2005) so that they were able to appropriately integrate their understanding of the source texts into the discussion of their own points of view in the response essay. Such a complicated and recursive reading phase was presented as part of a “pre-writing phase” in Plakans (2008)' working model of reading-to-write tasks, which apparently cast the attention on writing only without giving credit to reading as an inherent part of an integrated writing task. The reading-writing interaction was signified by bidirectional arrows. Nonetheless, how the interaction took place was not thoroughly explored nor described in detail.

Unsurprisingly, the phase of writing of the present study was not limited to sub-stages concerning writing acts alone. It proceeded with constant interactions with the source reading. However, the box labeled “using source text” during the writing phase in Plakans (2008)' working model of reading-to-write cannot accurately present what happens. During the drafting and later revising or editing the response essay, rereading and planning also occurred out of different needs and purposes. Source reading performed the role of a “constant companion” (Plakans and Gebril, 2012) and a “springboard” to assist the subsequent writing job (Jolliffe, 2007) as writers referred back to the source texts from time to time in the process of composing the response essay. The interaction between reading and writing was online all along. The inseparability of reading and writing and hence the recursive and reciprocal nature of reading-to-write tasks were manifest in the process.

In such a recursive and reciprocal task process, writers took a dual identity, i.e., they worked as both writers and readers when engaged in the response writing task, which in turn affected their purpose of reading or writing (Spivey, 1990). Conscious or subconscious of their dual identity in the present study, the writers took the initiative to develop plans of different kinds to perform their reading-to-write task at each phase. The active planning, a typical “monitoring” behavior, played a pivotal role leading to successful integrated writing tasks for writers could better manage their task process (Plakans et al., 2019). The writers of the present study did not aimlessly wander about the reading and writing task; instead, they were aware of what they needed to do at each phase. In some studies, the strong sense of task control or monitoring was attributed to the task design like think-aloud (Plakans et al., 2019); in some others, it was also considered to be elicited by the nature of integrated tasks (Ascención, 2008; Cumming et al., 2006; Plakans, 2009a; Plakans and Gebril, 2013). Under the circumstances of the present study, the latter makes a better sense. The hybrid nature of the reading-to-write task brought about the dual identity of the writers, who instinctively, actively, and deliberately planned for each step in the process.

The data and discussion of the inseparability of reading and writing in the present study contributed evidence from the Chinese context to the complex construct of integrated writing and offered some insight into the roles of the L2 writers.

4.2 The embedded sub-stages: planning and rereading

The complex and dynamic nature of reading-to-write tasks and the inseparability of reading and writing phases were especially prominent in the sub-stages of planning and rereading for their embedded occurrence based on the findings of the present study. Both the sub-stages recurred and co-occurred in the main phases of reading and writing.

The sub-stage, planning, in the three phases of this study presented its variety and complication due to the needs of the writers for different purposes. Consistent with the previous studies (Plakans, 2008; Plakans et al., 2019; Solé et al., 2013), planning in this study accompanied the writers from the initial pre-reading phase till the end of the response essay writing phase, showing its effect on the recursiveness of reading-to-write process. Also, the purposes of planning in different phases varied from one another, but not that simple as was accounted for as “Planning and organizing content” in the preparing-write phase and “Planning and rehearsal” in the writing phase in Plakans (2008)'s model. The number of writers (see Table 9) varied from one phase to another together with increasingly elaborate intents (see Table 10) for the accomplishment of the response essay writing.

Its patterns and purposes taken into consideration, planning worked as an important monitoring stage mediating between reading and writing acts. According to Table 9, the writers' need of planning were not very strong in the pre-reading phase, but peaked in the reading phase, and kept the high level of need till the writing phase. Similar to the three-step planning for a conventional topic-based essay (Kellogg, 1996): a general goal-setting, idea generation following the previously set goals, and ultimately idea organization, it did not indicate a linear process as writers adjusted their plans from time to time during reading and drafting out of online and momentary needs (Flower and Hayes, 1981, p. 373). This is particularly true in an integrated reading-to-write task. Although it is not surprising that experienced writers tend to plan before drafting, the addition of reading gives rise to the need of planning in the process of completing a reading-to-write task (Ascención, 2008; Plakans, 2009a; Plakans et al., 2019). In this study, planning served unveiling the task preliminarily in the pre-reading phase, reached its climax in the reading for writing phase as the writers were busy collecting and developing ideas on the basis of the source content, and continued its functioning in the writing from reading phase for their need to organize, finalize and adjust their ideas. Planning bridged the phases of reading and writing and therefore, belonged to a shared process between reading and writing (Ruiz-Funes, 1999a,b; Plakans et al., 2019).

Also recurring in both reading and writing phases, and in many cases, embedded with planning, was rereading. Almost all writers reported rereading the source texts in the reading for writing phase as well as in the writing from reading phase. Their purposes of rereading went beyond comprehension and seeking language support (Cumming et al., 2016; Grabe and Zhang, 2013; Plakans and Gebril, 2012; Plakans et al., 2019); they reread the source texts out of content and logic construction needs for the subsequent response essay writing because as they further analyzed and contemplated the source ideas, for example, assessing the validity of the major claims and evidence of the source texts, they would work out their own final viewpoint decisions and how they would exploit or refute the claims or evidence in concern. When composing their own response essays, rereading occurred as the writers needed to confirm the selected information, seek new information, push forward their idea development, find inspirations to generate new ideas. All such needs were not limited to basic comprehension or lexical retrieval; they served the logical and textual formulation of the final written product. These purposes of rereading naturally elicited new rounds of planning as the writers would adjust their idea generation and therefore, organization. As a “higher-level reading” (Pan and Lu, 2023, p. 9), pressing further thinking and more elaborate goal-setting, rereading accompanied the ongoing process of planning.

Planning and rereading worked together to bridge reading and writing in the present response writing task though the former is a conventional writing sub-stage, and the latter a typical reading sub-stage. They, too, were hardly separable, for their recurrence in both phases, which also represented the recursive and reciprocal nature of the integrated task. Planning is considered “the only reflective process” that guides the goal-setting processing and adjustment (Flower and Hayes, 1981; Hayes, 1996). In an integrated reading-to-write task, rereading could be viewed as an additional “process” that elicits reflection on both reading and writing. In the process analysis of previous studies (for example, Plakans, 2008), planning has not been given sufficient attention to while rereading was generally taken as a reading strategy for further comprehension, mostly for the purpose of seeking linguistic support (Plakans, 2009a). Their interactive relationship has not been even mentioned, let alone discussed. The findings of the present study contributed to the discovery and understanding of the two sub-stages.

4.3 Learner agency in play in the process of reading-to-write

One dimension that can hardly be ignored in the process of the current reading-to-write task was the roles of the Chinese writers. It has been extensively stressed that in addition to a set of skills required for an integrated writing task (Solé et al., 2013; Yang and Plakans, 2012), the roles and efforts of the writers cannot be ignored. The initiative of learners in a learning activity is termed “learner agency” (van Lier, 2008; Mercer, 2012). The way they exercised their agency contributed to their task performance by capitalizing their cognitive, metacognitive as well as contextual resources.

The cognitive and metacognitive resources facilitated the immediate enactment of learner agency and its later ubiquity in the process. The writers' prior understanding and experience with reading and writing argumentative pieces prompted them to be engaged in a set of sub-stages from the beginning pre-reading phase, through the reading for writing phase and till the eventual writing from reading phase. For instance, the sub-stages during the pre-reading phase—brainstorming what they had already known about the topic, predicting about the source texts, setting up an initial view, and even planning for the ultimate writing task—all took place within 5 min. The instant reaction to the given integrated task clearly came from the learning and training they had received from previous education, including but not limited to the writing course they were attending at the time of the study. The self-initiated actions without been pushed or instructed were typical presence of learner agency in a learning activity (Lin, 2013). Learners did not wait to be instructed to respond to a given task; instead, they actively reacted to the context and even impacted on the context, which supported both the presence of their agency and willingness to exercise their agency (Mercer, 2011, 2012).

The much-discussed metacognitive and self-regulatory elements in learner agentic system were particularly prominent in the sub-stages, planning and rereading, across both reading and writing phases. Indirectly contributing to the ultimate products, the two metacognitive stages (Plakans, 2008; Plakans et al., 2019) suggested the writers' awareness of their capacities of learner agency (Brown, 2009). In the present study, the participants all underwent rereading for their belief in its necessity in order to further analyze the source texts and better prepare for the subsequent response writing. Such awareness also led a number of writers to plan more than once, with greater elaboration of ideas and details over the process of task performance. Planning and rereading, either during the phase of reading or writing, mostly co-prompted the need of each other, pushing forward the task process or contributing to a better end-product.

Cultural belief and experience constituted significant resources for learners to enact their agency when deciding on view positions. In the present study, this was particular true with the topic, rote learning. The Chinese writers presented a mixed feeling toward the frequently employed learning approach in China, which can be dated back to its ancient times. On the one hand, the writers hated the method for the boredom and tediousness it brought to their learning process; on the other, when facing criticisms against the method, many of them turned to defend it by sharing their own experience to support its effectiveness. The attachment to their cultural tradition of repeated recitation could be part of the reason for their strong reaction to the disapproval of the source texts arguing against rote learning method. In contrast, as for the topic, global warming, a less culturally-loaded one, the writers did not hesitate too much and most chose to follow the idea that the phenomenon does exist. From the socio-cultural perspective, affective factors (Bandura, 2008) definitely have their impacts on whether and how learners exert their agency on an activity. The cultural factors involved in the writing topic entailed the enactment of the Chinese writers' agency, impacting on their evaluation of the source views as well as the final decision on the views of their own response essay writing.

The above-mentioned factors prompting the exercise of learner agency in the present reading-to-write tasks influenced the decisions and emergent sub-stages of the task process. They co-acted, and therefore, should be discussed in a holistic manner, which also provided evidence for why and how the process of a reading-to-write task was dynamic, recursive and reciprocal.

4.4 Developing a new model of reading-to- write tasks

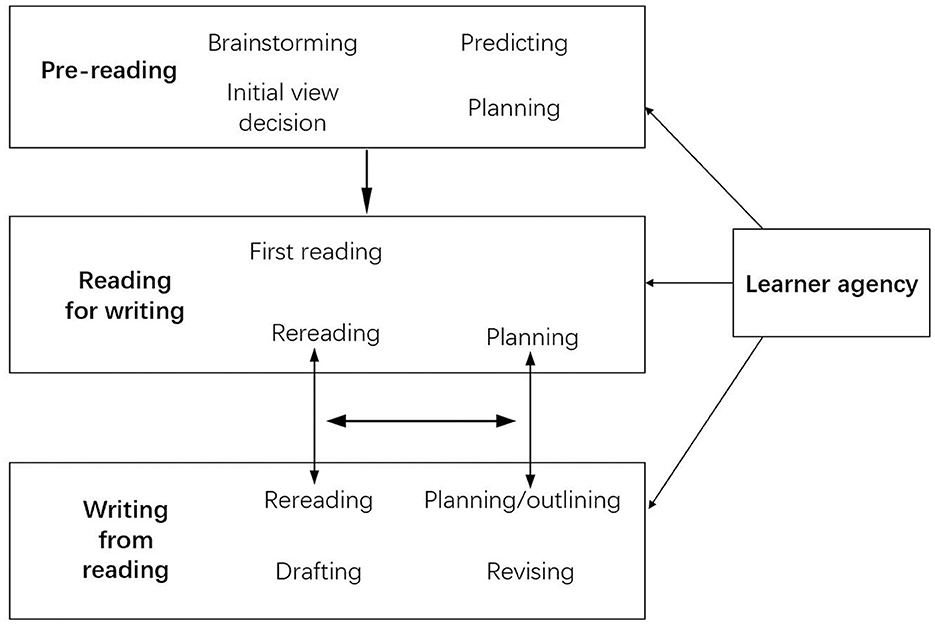

In light of the findings about the phases and sub-stages as well as their relationships and interactions, a tentative new model of reading-to-write tasks was proposed as follows (see Figure 1).

The main phases are presented in boldface located in three different boxes connected with arrows of different types. The sub-stages are included in each corresponding phase box. The pre-reading phase is a separate one from the other two. On the one hand, it is part of the special design of the present study; on the other, in any writing task, this phase is a naturally elicited one due to writers' cognitive sequence. It is connected to the phase of reading for writing by a unidirectional arrow for it occurred before the source texts were handed out.

The other two main phases, reading for writing and writing from reading are presented in the other two boxes connected to each other by bi-directional arrows, indicating their inseparable relationship as well as ongoing interactions. The sub-stages, planning and rereading, are positioned to highlight the frequent interactions between the main phases mainly by their bridging function in between. The bidirectional arrow right between rereading and planning presents their potential co-occurrence and inseparability, that is, some plans might have been generated by rereading the source texts, or new plans could have triggered the need of rereading.

Learner agency is placed beside the three phase boxes, linked to them by unidirectional arrows, signifying its ubiquitous roles in the process.

The new model avoids presenting the process of reading-to-write in a linear manner with unidirectional arrows linking the boxes of the main phases. Except planning and rereading, the positioning of the other sub-stages is not fixed as the sequence of their occurrence cannot be exactly presented as the writers might not undergo all the sub-stages or follow the same route out of individual factors. Planning and rereading are intentionally positioned at the edge of the boxes, bridging the main phases of reading and writing, indicating their function as a channel for free communication between them, disclosing the hybrid, recursive, and reciprocal nature of reading-to-write process. Also, their parallel positioning suggests potential chronological overlapping and equal significance.

Without abandoning the conventional cognitive perspective to interpret writing process in the late 20th century (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Flower and Hayes, 1980, 1981; Hayes, 1996; Kellogg, 1996), the new model attempts to present the unique procedures and process of reading-to-write tasks. While previous models, for example, Plakans (2008)'s model of reading-to-write tasks, casts the central attention to the writing phase, the new model gives equal weight to the phases of reading and writing. The reciprocal and recursive nature of the process has also been captured and presented by the constant interaction between reading and writing through a set of sub-stages.

In addition, these phases and sub-stages of reading and writing involve recursive and reciprocal decision-making processes of the writers. For the realization of the dynamic interaction, the learners cannot standby and passively receive the source texts; instead, they actively make decisions under the test conditions in their individual context. “A model is a metaphor for a process….” (Flower and Hayes, 1981, p. 368). In other words, an effective model can represent the key procedures as well as other contextual factors involved in a process. Also, some individual factors might have affected the performing processes of a response essay task in the present study as “there are as many writing processes as there are people who write, things to write, and goals to be served” (Kennedy, 1985, p. 439). The box “learner agency” in this new model is aimed at acknowledging the significant roles learners play in the process of reading-to-write tasks. Complicated yet dynamic as the process is, its recursiveness and reciprocity make an inherent part of integrated writing tasks (Cheong et al., 2019; Grabe and Zhang, 2013; Wette, 2017).

Tapping into the detailed processing of a reading-to-write task, the present study contributed data from the Chinese context to further supporting the non-linearity, yet recursiveness and reciprocity of integrated writing. The role of reading not simply manifested its significance at the level of comprehension and source selections, but was prominent and essential when rereading recurred, where writers further analyzed the source texts and adjusted their writing plans. In particular, the embeddedness of planning and rereading characterized the inseparability and hence the connection and interaction between the phases of reading and writing. In addition, individual roles could not be ignored in this complicated process. The Chinese writers in this study were found to have actively exercised their learner agency initiated by their previous learning experience as well as the on-the-spot motivation to well accomplish the task. A new model was eventually constructed based on the qualitative findings of this study, giving equal attention to reading and writing and taking learner agency into consideration. Hopefully, the account of the process may inform further understanding of the construct of reading-to-write tasks.

The findings of the study also suggest implications for L2 teaching of reading and writing. First of all, reading and writing instructions should be included in L2 curriculum design in a combined manner (Hirvela, 2004). The inseparable connection between reading and writing in integrated academic tasks requires the inclusion of explicit instructions in the courses for L2 students to acquire fundamental skills (Zhang, 2013). The evidence from the present study shows that in addition to basic comprehension, deep-level reading (for example, analytical reading) can be taught and trained. Systematic planning, with goals more elaborate one after another in the process of reading and writing, can also be important content of course instructions. Also, such instructions should be offered early and iteratively in the L2 teaching as learners need accumulate experience with the task type overtime (Grabe and Zhang, 2013). The findings of the study once again indicate that the cognitive processes are not the only factors impacting the process of reading-to-write tasks (Plakans, 2009b; Solé et al., 2013); learner roles cannot be ignored and await to be further researched. How learners can well enact their agency in the process of integrated writing tasks can be guided according to their specific circumstances. The complication of the academic task entails intentional teaching in L2 context.

Exploratory and qualitative-oriented as it is, the present study incurs several limitations in methodology. First of all, data collection and data analysis came from immediate retrospective interviews and reflective journals shortly after the response writing task was completed. The loss of memory and inaccuracy of reflections were inevitable. Secondly, the average number of participants of each group is relatively small. Caution should surely be urged for generalization of the findings. Thirdly, the topic selection of source texts should also be reconsidered for familiarity with and interest in the topics may also affect the processing of readings and interpretation of the ideas. Fourthly, learner agency has not been clearly categorized in correspondence to the phases and sub-stages. In the end, proficiency threshold has not been taken into consideration. The L2 writers of different proficiency levels may choose different approaches or routes to access and process a reading-to-write task. Future research could try a combination of both online methods (e.g., think-aloud protocol or eye-tracking devices) with retrospective approaches, a larger population of participants from various proficiency levels, new and intriguing topics of readings, and a thorough exploration into the impact of learner agency, so that the model can be further examined and thus improved.

Though having been researched to a great extent over the last few decades, reading-to-write tasks have not caught sufficient attention in second language teaching and learning. The present study revisited the process of reading-to-write tasks in a more detailed manner on a group of Chinese learners, contributing new data to the field of integrated writing, supporting the recursive and reciprocal nature of the hybrid task type, and building a new model by highlighting the significant roles of the sub-stages, rereading and planning. In addition, learner agency was considered to play important roles in the process. Further research could be conducted to verify and improve the model, taking into consideration the educational, cultural, and contextual challenges of L2 learners so as to provide fresher understanding of the construct of integrated tasks.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee/Social Science Sub-Committees of Nanjing University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by all the participants.

Author contributions

LW: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/flang.2024.1422123/full#supplementary-material

References

Ascención, Y. (2004). Task representation of a Japanese L2 writer and its impact on the usage of source text information. J. Asian Pacific Commun. 14, 77–89. doi: 10.1075/japc.14.1.06all

Ascención, Y. (2008). Investigating the reading-to-write construct. J. English Acad. Purp. 7, 140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2008.04.001

Bandura, A. (2008). “Toward an agentic theory of the self,” in Self-processes, learning, and enabling human potential: Dynamic new approaches, eds. H. W. Marsh, R. G. Craven, and D. M. McInnerney Charlotte (NV: Information Age Publishing), 15–49.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1987). The Psychology of Written Composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Press.

Bider, D., and Gray, B. (2013). Discourse characteristics of writing and speaking task types on TOEFL iBTTM test: A lexical-grammatical analysis (TOEFL iBTTM Research report/TOEFL iBT-19). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. doi: 10.1002/j.2333-8504.2013.tb02311.x

Brown, J. (2009). Self-regulatory strategies and Agency in self-instructed language learning: a situated view. Mod. Lang. J. 93, 570–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00965.x

Chaffee, J. (1985). Viewing reading and writing as thinking process. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicargo, IL. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED260110.pdf (accessed November 10, 2022).

Cheong, C. M., Zhu, X., Li, G. Y., and Wen, H. (2019). Effects of intertextual processing on L2 integrated writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 44, 63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2019.03.004

Cumming, A., Kantor, R., Baba, K., Erdosy, U., Eouanzoui, K., and James, M. (2005). Differences in written discourse in independent and integrated prototype tasks for Next Generation TOEFL. Assess. Writ. 10, 5–43. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2005.02.001

Cumming, A., Kantor, R., Baba, K., Erdosy, U., Eouanzoui, K., and James, M. (2006). Analysis of Discourse Features and Verification of Scoring Levels for Independent and Integrated Prototype Tasks for new TOEFL (TOEFL Monograph No. MS-30). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. doi: 10.1002/j.2333-8504.2005.tb01990.x

Cumming, A., Lai, C., and Cho, H. (2016). Students' writing from sources for academic purposes: a synthesis of recent research. J. English Acad. Purp. 23, 47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2016.06.002

Cumming, A., Yang, L., Qiu, C., Zhang, L., Ji, X., Wang, J., et al. (2018). Students' practices and abilities for writing from sources in English at universities of China. J. Second Lang. Writ. 39, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2017.11.001

Delgado-Osorio, X., Koval, V., Hartig, J., and Harsch, C. (2023). Strategic processing of source text in reading-into-writing tasks: A comparison between summary and argumentative tasks. J. English Acad. Purp. 62, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101227

Esmaeili, H. (2002). Integrated reading and writing tasks and ESL students' reading and writing performance in an English language test. Canad. Mod. Lang. J. 58, 599–622. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.58.4.599

Fitzgerald, J., and Shanahan, T. (2000). Reading and writing relations and their development. Educ. Psychol. 35, 39–50. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3501_5

Flower, L. S. (1990). “Introduction: studying cognition in context,” in Reading-to-write: Exploring a cognitive and social process, eds L. S. Flower, V. Stein, J. Ackerman, M. J. Kantz, K. McCormick, and W. C. Peek (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 3–32. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780195061901.001.0001

Flower, L. S., and Hayes, J. R. (1980). The cognition of discovery: defining a rhetorical problem. College Composit. Commun. 31, 21–32. doi: 10.58680/ccc198015963

Flower, L. S., and Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composit. Commun. 32, 365–387. doi: 10.58680/ccc198115885

Flower, L. S., and Hayes, J. R. (1985). Response to marylin cooper and michael holzman, “Talking about protocols.” College Composit. Commun. 36, 94–97. doi: 10.2307/357610

Gebril, A., and Plakans, L. (2013). Toward a transparent construct of reading-to-write tasks: the interface between discourse features and proficiency. Lang. Assess. Q. 10, 9–27. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2011.642040

Grabe, W. (2003). “Reading and writing relations: Second language perspectives on research and practice,” in Exploring the Dynamics of Second Language Writing, ed. B. Kroll (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139524810.016

Grabe, W., and Zhang, C. (2013). Reading and writing together: a critical component of English for academic purposes teaching and learning. TESOL J. 4, 9–24. doi: 10.1002/tesj.65

Hayes, J. R. (1996). “A new framework to understanding of cognition and affect in writing,” in The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences and Applications, eds. C. M. Levy, and S. Ransdell (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 1–17.

Hirvela, A. (2004). Connecting Reading and Writing in Second Language Writing Instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.23736

Hyland, K. (2013). Faulty feedback: perceptions and practices in L2 disciplinary writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 22, 240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2013.03.003

Hyland, K. (2016). Teaching and Researching Writing (3rd edition). London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315717203

Jolliffe, D. A. (2007). Learning to read as continuing education. College Composit. Commun. 58, 470–494. doi: 10.58680/ccc20075915

Jung, J. (2020). Effects of content support on integrated reading-writing task performance and incidental vocabulary learning. System 93, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102288

Kellogg, R. T. (1996). A model of working memory in writing,” in The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications, eds. C. M. Levy, and S. Ransdell (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 57–71.

Kennedy, M. L. (1985). The composing process of college students writing from sources. Written Commun. 2, 434–456. doi: 10.1177/0741088385002004006

Khalifa, H., and Weir, C. J. (2009). Examining reading: Research and practice in assessing second language reading. Modern Lang. J. 95, 334–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01200.x

Leki, I. (1993). “Reciprocal themes in reading and writing,” in Reading in the Composition Classroom: Second Language Perspectives, eds J. G. Carson, and I. Leki (Boston: Heinle and Heinle).

Lenski, S. D., and Johns, J. L. (1997). Patterns of reading-to-write. Read. Res. Instr. 37, 15–18. doi: 10.1080/19388079709558252

Lin, Z. (2013). Capitalizing on learner agency and group work in learning writing in English as a foreign language. TESOL J. 4, 633–654. doi: 10.1002/tesj.60

McCulloch, S. (2013). Investigating reading-to-write processes and source use of L2 postgraduate students in real-life academic tasks: an exploratory study. J. English Acad. Purp. 12, 136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2012.11.009

McGinley, W. (1992). The role of reading and writing while composing from sources. Read. Res. Q. 27, 226–248. doi: 10.2307/747793

Mercer, S. (2011). Understanding learner agency as a complex dynamic system. System 39, 427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.08.001

Murrey, H. (1991). Close reading, closed writing. College Writ. 53, 195–208. doi: 10.58680/ce19919595

Nelson, N. (1998). “Reading and writing contextualized,” in The reading-writing connection: Ninety-seventh year-book of the National Society for the Study of Education, eds N. Nelson and R. C. Calfee (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 266–285. doi: 10.1177/016146819809900612

Pan, R., and Lu, X. (2023). The design and cognitive validity verification of reading-to-write tasks in L2 Chinese writing assessment. Assess. Writ. 56, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2023.100699

Plakans, L. (2008). Comparing composing processes in writing-only and reading-to-write test tasks. Assess. Writ. 13, 111–129. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2008.07.001

Plakans, L. (2009a). The role of reading strategies in integrated L2 writing tasks. J. English Acad. Purp. 8, 252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2009.05.001

Plakans, L. (2009b). Discourse synthesis in integrated second language assessment. Lang. Test. 26, 561–587. doi: 10.1177/0265532209340192

Plakans, L., and Gebril, A. (2012). A close investigation into source use in integrated second language writing. Assess. Writ. 17, 18–34. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2011.09.002

Plakans, L., and Gebril, A. (2013). Using multiple texts in an integrated writing assessment: Source text use as a predictor of score. J. Second Lang. Writ. 22, 217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2013.02.003

Plakans, L., Liao, J. T., and Wang, F. (2019). “I should summarize the whole paragraph”: shared processes of reading and writing in iterative integrated assessment tasks. Assess. Writ. 40, 14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2019.03.003

Qin, J., and Karabarak, E. (2010). The analysis of Toulmin elements in Chinese EFL university argumentative writing. System 38, 444–456. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2010.06.012

Ruiz-Funes, M. (1999a). The process of reading-to-write used by a skilled Spanish-as-a-foreign-language student: a case study. Foreign Lang. Ann. 32, 45–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.1999.tb02375.x

Ruiz-Funes, M. (1999b). Writing, reading, and reading-to-write in a foreign language: a critical review. Foreign Lang. Ann. 32, 515–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.1999.tb00880.x

Solé, I., Miras, M., Castells, N., Espino, S., and Minguela, M. (2013). Integrating information: an analysis of the processes involved and the products generated in a written synthesis task. Written Commun. 30, 60–90. doi: 10.1177/0741088312466532

Spivey, N. N. (1990). Transforming texts: constructing processes in reading and writing. Written Commun. 7, 256–287. doi: 10.1177/0741088390007002004

Spivey, N. N., and King, J. R. (1989). Readers as writers composing from sources. Read. Res. Q. 24, 7–26. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.24.1.1

Stapleton, P., and Wu, Y. (2015). Assessing the quality of arguments in students' persuasive writing: a case study analyzing the relationship between surface structure and substance. J. English Acad. Purp. 17, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2014.11.006

Tierney, R. J., and Pearson, P. D. (1983). Toward a composing model of reading. Lang. Arts 60, 568–580. doi: 10.58680/la198326307

Trites, L., and McGroarty, M. (2005). Reading to learn and reading to comprehend: New tasks for reading comprehension test. Lang. Test. 22, 174–210. doi: 10.1191/0265532205lt299oa

van Lier, L. (2008). “Agency in the classroom,” in Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages, eds J. P. Lantolf and M. E. Poahner (London: Equinox), 163–186.

Wanatabe, Y. (2001). Reading-to-write Tasks for the Assessment of Second Language Academic Writing Skills: Investigating Text Features and Rating Reactions. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii in Manoa.