95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 24 March 2025

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1522417

Bensu Du1†

Bensu Du1† Jin Geng2†

Jin Geng2† Bin Wu3†

Bin Wu3† Houru Wang4

Houru Wang4 Ru Luo5

Ru Luo5 Hanmeng Liu5

Hanmeng Liu5 Rui Zhang1

Rui Zhang1 Fengping Shan6

Fengping Shan6 Lei Liu7*

Lei Liu7* Shuling Zhang8*

Shuling Zhang8*In general, increasing lymphocyte entry into tumor microenvironment (TME) and limiting their efflux will have a positive effect on the efficacy of immunotherapy. Current studies suggest maintenance lymphocyte homeostasis during cancer immunotherapy through the two pipelines tumor-associated high endothelial venules and lymphatic vessels. Tumor-associated high endothelial venules (TA-HEVs) play a key role in cancer immunotherapy through facilitating lymphocyte trafficking to the tumor. While tumor-associated lymphatic vessels, in contrast, may promote the egress of lymphocytes and restrict their function. Therefore, the two traffic control points might be potential to maintain lymphocyte homeostasis in cancer during immunotherapy. Herein, we highlight the unexpected roles of lymphocyte circulation regulated by the two gateways for through reviewing the biological characters and functions of TA-HEVs and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels in the entry, positioning and exit of lymphocyte cells in TME during anti-tumor immunity.

The recruitment of lymphocytes into the tumor microenvironment (TME) is an essential way to enhance the efficacy of the treatments involving immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), vaccines, or adoptive T cell immunotherapy (1–3). Before infiltrating into TME, the lymphocytes usually migrate to the blood vessels and then extravasate from them (4). High endothelial venules (HEVs) are specialized vessels dedicated to lymphocyte recruitment in lymph nodes and other lymphoid organs (5, 6). Lymphocytes including CD8+ T cells can enter tumor tissue through HEVs and then participate in antitumor activities. Previous studies revealed that MECA-79+ tumor-associated HEVs (TA-HEVs) were present in some types of human solid tumors, and the density of TA-HEVs in TME was associated with the numbers of CD3+ CD8+ T cells and CD20 B cells (4, 7, 8). Subsequently, another study evidenced that the cycling lymphocytes in blood could enter the tumor tissue continuously through TA-HEVs, thus enhancing the immune response during antitumor activities (9).

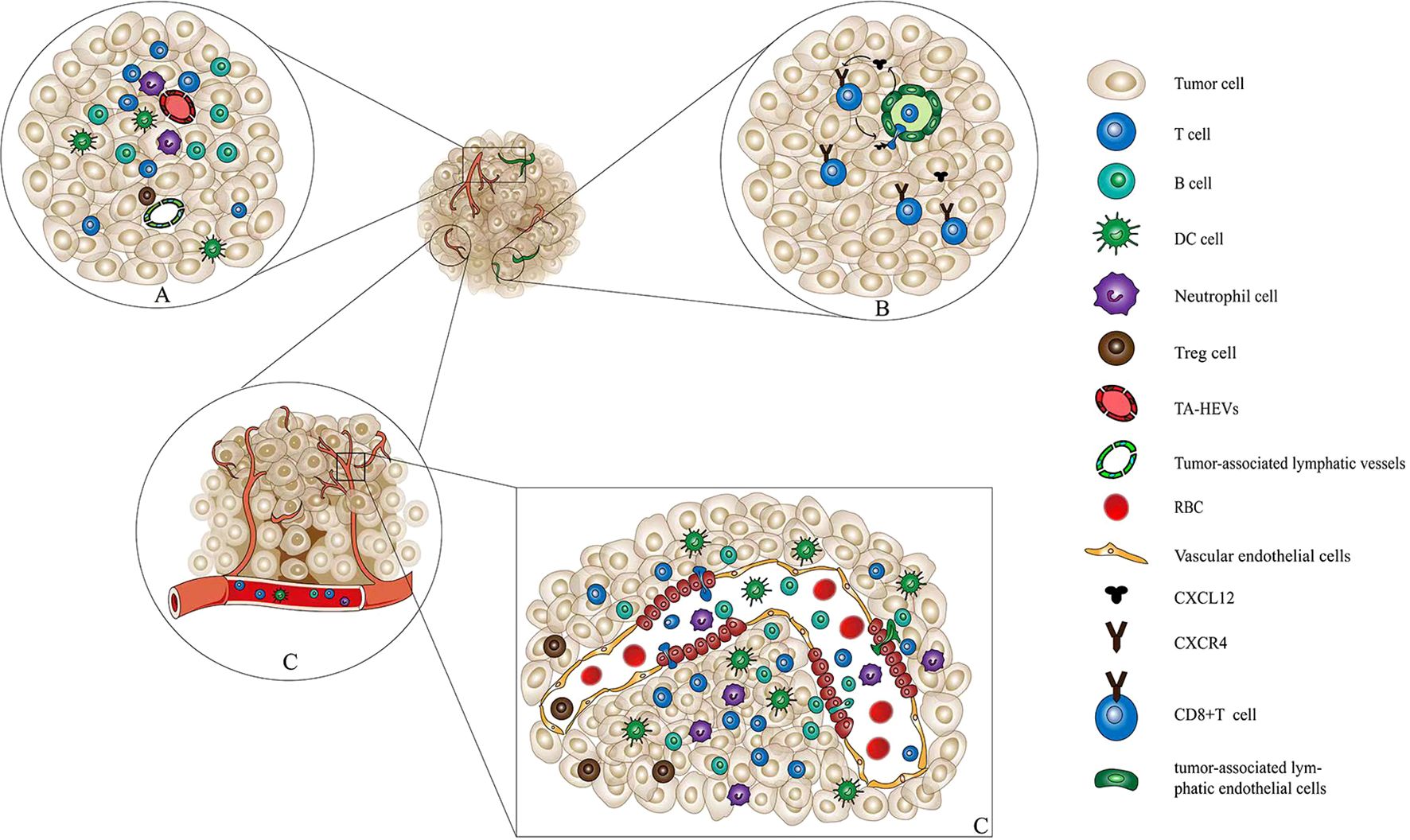

The accumulation of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells within TME is essential for the efficacy of immunotherapy. Besides increasing the infiltration of T cells into TME, reducing the leakage of effecter T cells from TME is another way to enhance the effects of antitumor activities. Studies exploring the exit of lymphocytes from tumor tissue mainly focused on the lymphatic vessels regulated by antigen contact (10). The C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12(CXCL12) is produced by tumor-associated lymphatic endothelial cells. The C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) on the surface of T cells binds to and recognizes CXCL12 and then leaves the tumor along the lymphatic vessels and is sealed around the tumor (Figures 1A, B).

Figure 1. Interaction among immune cells, TA-HEVs, and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels. (A) Interaction among immune cells, TA-HEVs, and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels. In tumor tissue, immune cells including CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and DCs infiltrate tumor tissue through tumor-associated high endothelial venules and exit through tumor-associated lymphatic vessels. In this way, the immune cells maintain their number and function of infiltration in tumor tissue. (B) Tumor-associated lymphatic vessels mediate the exit of CD8+ T cells from the tumor tissue. Tumor-associated lymphatic endothelial cells can secrete the cytokine CXCL12. Further, CXCL12 binds to the receptor CXCR4 on the surface of CD8+ T cells, inducing CD8+ T cells to approach and pass through the lymphatic endothelial cell space, and finally exit the tumor tissue. (C) HECs and the structure of vascular endothelial cells and immune cells through the HECs into tumor tissue. HECs are transformed by capillary endothelial cell migration. Immune cells such as lymphocytes, mediated by chemokines, undergo processes such as receptor recognition, adhesion, and rolling to infiltrate tumor tissues through paracellular pathways. TA-HEVs, tumor-associated high endothelial venules; DCs, dendric cells; CXCL12, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12; CXCR4, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; HECs, high endothelial cells.

Therefore, strategies limiting the leakage of effector T cells from TME while increasing the infiltration of T cells into TME can help improve the efficacy of immunotherapy. We conducted this systematic review on both the entry and exit of lymphocytes from TME, aiming to explore the potential avenues to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy.

As specialized postcapillary venules, HEVs are primarily located in other secondary lymphoid tissues except the spleen (11). High endothelial cells (HECs) are unique microstructures in HEVs, characterized by highly columnar and approximately cuboidal endothelial cells, with a width of 7–10 μm and a height of 5–7 μm (12–14), thus distinguishing them from other common endothelial cells. HECs occupy most of the luminal space, and hence the lumen of HEVs is narrow or even closed and covered with a thick basement membrane and a perivascular sheath (5, 15, 16). HECs have a large round nucleus with one or two nucleoli and abundant organelles such as mitochondria, rough endoplasmic reticulum, ribosomes, and Golgi complex. They show the characteristics of secretory cells with highly fast metabolism (15, 17–19). Ultrastructural studies revealed that HECs have a thick carbohydrate-rich glycocalyx coating on their luminal surface (20–22). In addition, sulfated carbohydrates and glycoproteins are important recognition determinants of L-selectin in lymphocytes (23). Moreover, the glycocalyx in HECs may also facilitate the retention of secreted molecules on the luminal surface of HECs (14, 20).

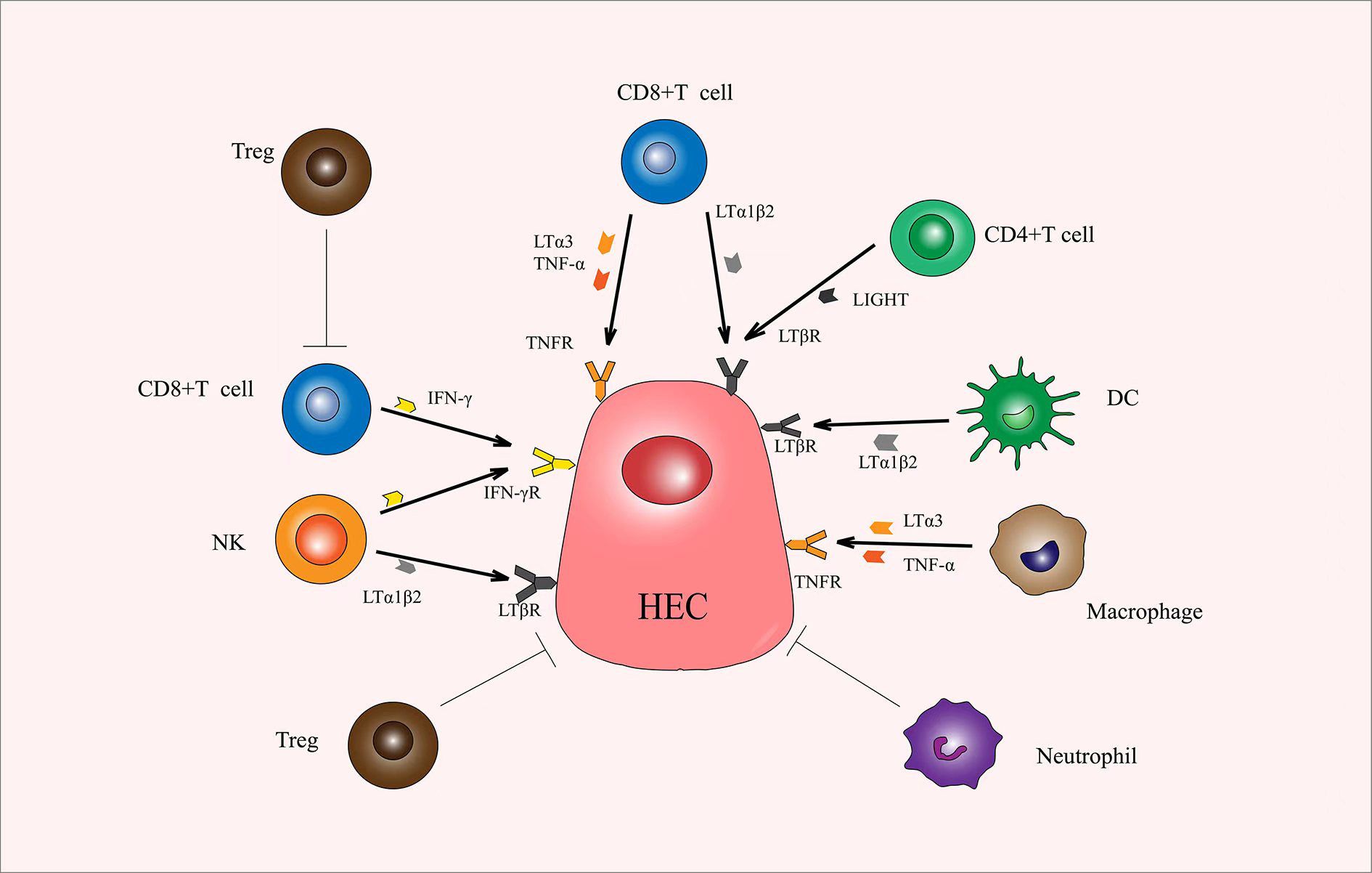

As HECs are specialized capillary endothelial cells, we focused on their mode of transformation. The pathway represented by lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which are mainly secreted by activated lymphocytes and natural killer cells (NK cells), is the most critical signaling pathway during HEVs formation (4). Lymphotoxin α3(LTα3) or TNF-α binds to tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 or 2 (TNFR1/2), whereas LTα1β2 or tumor necrosis factor superfamily 14 (LIGHT) signals bind to LTβR. TNF-α or LTα3 drives spontaneous HEVs formation, whereas LTα1β2 and LIGHT are the major inducers of HEVs. After HEVs formation, their special morphology also needs to be maintained (24, 25). LTβR signaling is important in maintaining the HEVs phenotype because LTαβ/LTβR signaling can maintain the cube-like morphology of HECs (26, 27). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P)–S1PR1 axis also plays a role in regulating HEVs maintenance (28–30). The complex relationship between LTβR signaling and TA-HEVs plays an important role in the differentiation and growth of TA-HEVs (27, 31). As such, LTβR agonists are potent inducers of TA-HEVs in tumors (32).

The special structure of HECs contributes to the special role of HEVs in lymphocyte homing and recycling (33–35). Lymphocytes may enter lymph nodes via two transendothelial migration pathways: the paracellular route (through intercellular spaces) and the transcellular route (through endothelial cells). However, the paracellular route is predominant (36–39). First, the ligands of L-selectin synthesized by HECs are processed by the Golgi complex, stored in secretory granules, and released on the luminal surface of HECs for recognition by homing receptors on the surface of passing lymphocytes to initiate the homing of lymphocytes (40). Next, the circulating lymphocytes in the blood bind to the 6-sulfo sialyl Lewis X motif modifying HEVs via L-selectin, and then tether and roll on the HEVs wall, allowing them to immobilize with heparan sulfate and interact with chemokines on the luminal surface of HEVs (41, 42). These chemokines can mediate the activation of integrins essential for lymphocyte arrest in HEVs (43–47). Integrin lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1 (LFA1) is the major integrin responsible for T and B cell arrest in HEVs in peripheral lymph nodes. The combination of the shear stress of blood flow and the G protein-coupled chemokine receptor signaling induces a conformational change in the LFA1 molecule, leading to the firm adhesion of lymphocytes to intercellular adhesion molecules 1 and 2 (ICAM1 and ICAM2) expressed on HECs (44, 46, 48). After stable arrest, the lymphocytes crawl along the luminal surface of the HEVs in search of suitable transport sites. Thereafter, they migrate through transcellular or paracellular pathways (49, 50). During migration through the paracellular pathway, the high columnar HECs rapidly close the opened intercellular space on the side of the lumen after lymphocyte passage, thus minimizing the leakage of intravascular fluid (36, 51).

The antitumor immune response primarily depends on the activity of tumor-specific lymphocytes that can recognize and eliminate tumor cells. TA-HEVs are a major gateway for lymphocyte infiltration into human tumors. They are usually found in areas with B cell–rich tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) as well as in areas with high densities of T cells and mature dendritic cells (DCs) (52, 53). TA-HEVs can be induced in different types of tumors (54, 55). However, MECA-79+ TA-HEVs are sometimes formed spontaneously in the TME even without any treatment (55–57). MECA-79+ TA-HEVs facilitate the recruitment of naive lymphocytes to tumors (4, 58). Further studies suggested that a high density of MECA-79+ TA-HEVs was associated with increased infiltration of naive and central memory T cells into TME (4, 7, 52). Therefore, an increase in the number of T cells in different morphological stages within the tumor is proposed to accelerate and foster antitumor response (59, 60). The induction of MECA-79+ TA-HEVs is also observed in a number of mouse tumor models. This is associated with the infiltration of T cells, especially CD8+ T cells, and the inhibition of tumor growth (61, 62). Moreover, increasing the differentiation and maturation of HEVs in tumors can reduce CD8+ T cell depletion and lead to an increase in the proportion of stem-like CD8+ T cells (52) (Figure 1C).

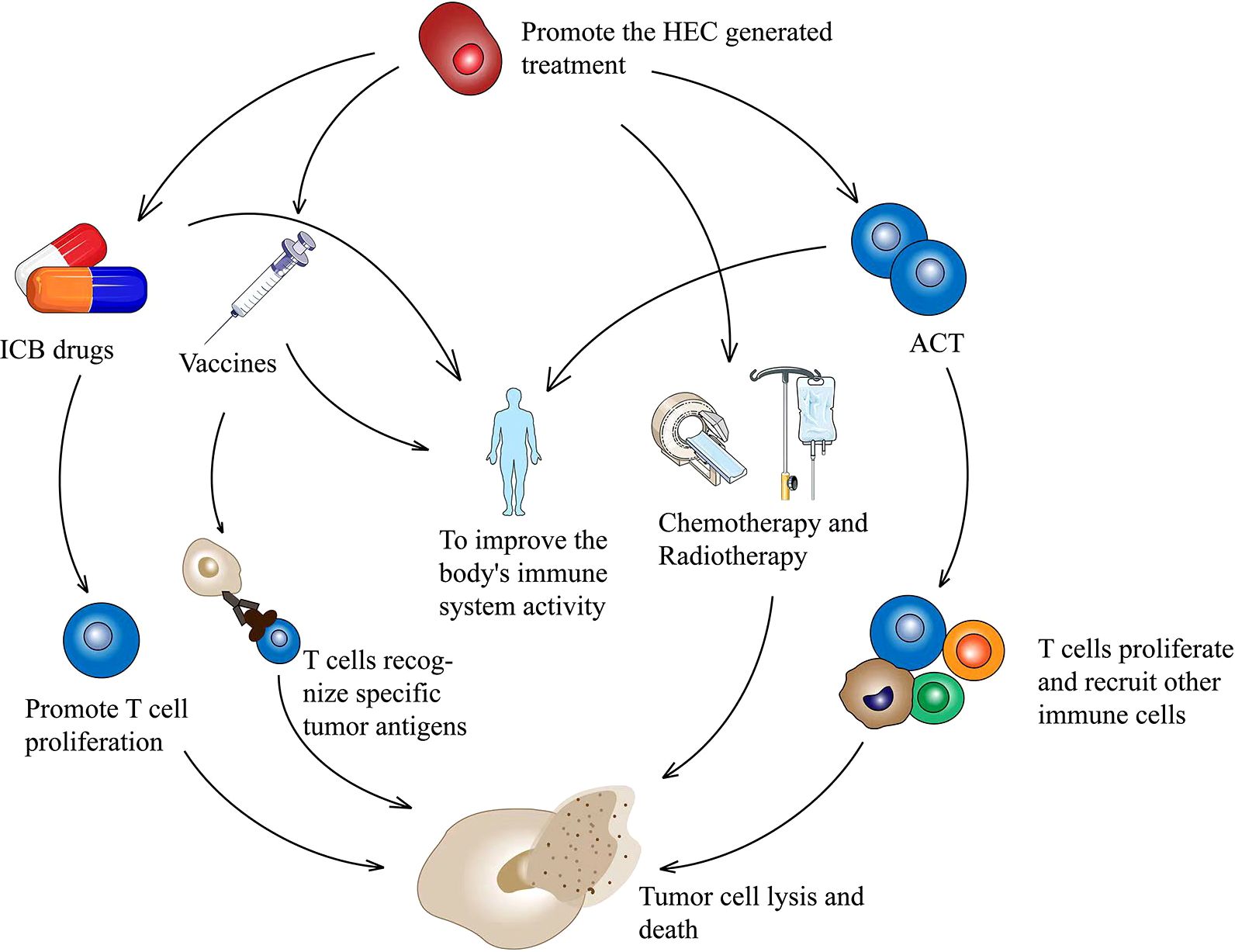

Theoretically, the efficacy of immunotherapy can be potentiated by the increased generation of HEVs, which in turn promotes lymphocyte entry into TME. In fact, many studies have suggested that the therapeutic induction of TA-HEVs in tumors might enhance the trafficking of endogenous lymphocytes, as well as adoptive transferred lymphocytes, and improve the efficacy of various cancer therapies, including immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), adoptive T cell therapy (ACT), vaccines, and potential targeted and conventional cancer therapies (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) (2, 63) (Figure 2). Additionally, the immune cells, especially lymphocytes, may also have an effect on TA-HEVs. CD8+ T cells may be the major inducers of TA-HEVs in tumors (64, 65). CD8+ T cells can produce LTα3, LTα1β2, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and other signals that induce the activation of lymphotoxin beta receptor (LTβR), thus contributing to the production of TA-HEVs (66). NK cells express LTα1β2 and IFN-γ. Follicular helper T cells express LIGHT. Macrophages express TNF-α, and LTα3 plays a role in contributing to the production of TA-HEVs. In other tumor models, the generation of TA-HEVs also requires the participation of B cells and DCs (65, 67–69). Some DCs can express LTβR and directly promote the differentiation of DC-dependent HEVs (31). CD11c integrin is important in DC physiology; Moussion and Girard demonstrated in mice that CD11c cells were essential for HEVs formation (6, 70). Thus, a larger number of CD11c cells could trigger increased HEVs formation (70). The additional regulatory role of DCs is to promote the growth of TA-HEVs in a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-dependent manner (71, 72). Regulatory T cells (Tregs) appear to limit the development of TA-HEVs in tumors, but their mechanism of action remains unclear (69, 73). The appropriate ways to treat LTβR should be explored, and the number of CD8+ T cells, DCs, and Tregs should be reasonably regulated (Figure 3). Tumor progression may also affect the presence of TA-HEVs, which needs further investigation. Since the last decades, ICB therapy, including programmed death 1 and programmed death-ligand 1(PD-1 and PD-L1) blockade treatments, has exhibited positive effects in antitumor immunotherapy for several solid tumors (2). Therefore, we focused on the association between ICB therapy and TA-HEVs. Previous studies suggested that anti-PD-1 therapy might have the potential to promote tumor immunity by stimulating the formation of TA-HEVs (74). At the same time, the formation of TA-HEVs can cooperate with anti-PD-1 therapy to promote the infiltration of lymphocytes, so that they can play a potent immune role against tumors (5, 75). Some other ICIs, such as anti-CTLA-4, can increase the abundance of TA-HECs and tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (52, 74). A combination of antiangiogenic therapy and ICB also achieved similar efficacy, thus improving the infiltration of CD8+ T cells from the periphery (52). Some mouse experiments revealed a significant increase in the homing efficiency of TA-HEV-mediated lymphocytes after ICB treatment, possibly contributing to an increase in the tumor-specific T cell repertoire (76, 77).

Figure 2. HECs production therapy in combination with other treatment options to inhibit tumor cell proliferation. Therapies combined with ICB promote T cell activation and proliferation. A combination with tumor vaccine promotes T cell specificity and kills tumor cells. HECs therapy combined with ACT promotes the proliferation of tumor killer T cells and recruits other immune cells. A combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy effectively kills tumors. HECs, high endothelial cells; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; ACT, adoptive T cell therapy.

Figure 3. Immune cells produce various cytokines that promote or inhibit the production of HECs. CD8+ T cells play an important role in the production of HECs. LTα1β2, LTα3, TNF-α, and IFN-γ secreted by CD8+ T cells promotes the production and differentiation of HECs. CD4+ T cells secrete LIGHT, DCs secrete LTα1β2, macrophages secrete LTα3 and TNF-α, and NK secrete LTα1β2 and IFN-γ, and all can promote the production and differentiation of HECs. Tregs and neutrophils can exert a direct inhibitory effect. Also, Tregs can inhibit the function of CD8+ T cells. HECs, high endothelial cells; LTα1β2, lymphotoxin α1β2; LTα3, lymphotoxin α3; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; IFN-γ, interferon γ; LIGHT, tumor necrosis factor superfamily 14; DCs, dendric cells.

Tumor-associated lymphatic vessels carry interstitial fluid and leukocytes unidirectionally from peripheral tissues to lymph nodes and are mainly involved in the generation, maintenance, and regression of adaptive immunity (78). Tumor-associated lymphatic vessels and their transport function are important conditions for controlling the exit of lymphocytes from tumor tissues. Tumor-associated lymphatic vessels can exert immunosuppressive effects, cross-present antigens, and limit CD8+ T cell-dependent tumor control in an interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-dependent manner, directly leading to tumor immune escape (79–83). However, the lymphatic system also contributes to regulating the diversity and functional status of CD8+ T cells within the tumor (84).Therefore, the inhibition of CD8+ T cell shedding by the lymphatic system is an important control point to enhance the response to immunotherapy.

The exit of lymphocytes from tumors through tumor-associated lymphatic vessels is mainly regulated by various chemokines. For example, chemokine12 (CXCL12) and its receptor CXCR4 mediated the exit of CD8+ T cells from the tumor through tumor-associated lymphatic vessels. In this process, CXCL12, a ligand for CXCR4, has been shown to promote the egress of DCs and B-lymphocytes (85, 86). CXCL12 can also promote the exit of CXCR4 CD8+ T cells from the tumor, and lymphangiogenic CXCL12 is sufficient to affect the accumulation and location of T cells in the tumor (10). Antigen contacts regulate surface CXCR4, and therefore CD8+ T cells are sensitive to CXCL12. The peritumoral tumor-associated lymphatic vessels direct the location and retention of CD8+ T cells in the TME by expressing CXCL12, which recruits and ultimately egresses a wide range of functional tumor-specific CXCR4 CD8+ T cells (87). Blocking CD8+ T cell shedding through this pathway can improve local tumor control and ICB response (88, 89). Atypical chemokine receptor 3 (ACKR3) is a decoy receptor for CXCL12. CD8+ T cells can modulate their CXCL12 sensitivity in vivo by downregulating the expression of surface CXCR4 and upregulating the expression of ACKR3 [ (10, 90). Therefore, the retention of memory and effector CD8+ T cells in tumor tissue can be promoted by downregulating the CXCR4 expression or reducing its sensitivity to CXCL12, thus allowing it to play an immune role against the tumor for a longer time (87).

Not all the T cells in the tumor are exported under the action of CXCL12–CXCR4, but selectively. Besides the role of CXCR4, T cell differentiation is also coordinated to participate in exported and retained lymphocyte screening. Exported effector CD8+ T cells have various transcriptional modules with retained effector CD8+ T cells (91). Tumor-retained effector CD8+ T cells are enriched for transcriptional modules related to hypoxia, leukocyte activation, and extracellular matrix organization, whereas exported CD8+ T cells are enriched for transcriptional modules related to leukocyte migration, glutamate receptor signaling, and branched-chain amino acid catabolism. The retained intratumoral CD8+ T cells are enriched for a gene set that is upregulated upon exhaustion (e.g., PD-1, nuclear receptor subfamily 4,group a(Nr4a2), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4(Ctla4), and T cell immune receptor with Ig and ITIM domains(Tigit)), whereas exported CD8+.T cells are enriched for a gene set that is downregulated upon exhaustion (e.g., transcription factor 7(Tcf7), selectin L(Sell), Lympho-enhancing factor 1(Lef1), chemokine receptors 7(Ccr7), and Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1(S1pr1)) (92). In addition, CD8+ T cells within the tumor predominantly express TCF1. However, a subset of exported CD8+ T cells expresses both TCF1 and PD-1, with PD-1 exported cells expressing lower levels of PD-1 than retained cells (93, 94). Finally, a fraction of the exported CD8+ T cells could produce effector cytokines after restimulation in vitro, whereas the retained CD8+ T cells could not produce effector cytokines (95).

In the immunotherapy of Tumor-associated lymphatic vessels, we focused on the role of VEGF. VEGF and its receptor are mainly responsible for the occurrence, development, and remodeling of lymphatic vessels (96). The major molecular drivers of tumor-associated lymphatic vessels are VEGF-C and VEGF-D, which are produced by tumor and infiltrating myeloid cells (96). VEGF-C and VEGF-D exert their biological effects by binding to VEGFR-3 and VEGFR-2, and activate receptor tyrosine kinase activity through autophosphorylation, thereby activating the function of lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels (97, 98). The blockade of the VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 pathway inhibits tumor-associated lymphatic vessels and tumor growth in colorectal and breast cancer models (99). In both glioblastoma and intracranial melanoma models, VEGF-C delivery is highly synergistic with immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment (anti-PD-1 alone or in combination with anti-CTLA-4) (100). Many chemokines have been found to have different effects on tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis. For example, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5(CCL5) is involved in angiogenesis and can increase VEGF expression in tumor cells by activating chemokine receptors 1 and 5 (CCR1 and CCR5) (101–104). Moreover, it has a synergistic effect with C-C motif chemokine ligand 4(CCL4) to indirectly cause lymphangiogenesis by increasing the expression of VEGF-C (105–107). Clinical and histopathological studies showed that cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression was associated with tumor-associated lymphatic vessels density and lymph node metastasis in human malignancies (108–111). The treatment with COX-2 inhibitors can halt tumor progression by simultaneously inhibiting local inflammation, tumor-associated lymphatic vessels, and angiogenesis (112, 113). Also, evidence shows that IFN-γ secreted by cytotoxic T cells reduces lymphatic vessel density in homeostatic and inflamed lymph nodes(LN) and promotes the immunosuppressive function of LECs in tumors (80, 82, 114). Therefore, targeted therapy increases the number of tumor-associated cytotoxic T cells, thus inducing the apoptosis of LECs and decreasing the number of tumor-associated lymphatic vessels (81).

HEVs are special vessels for transporting lymphocytes. They belong to the tumor-associated vasculature together with tumor-associated lymphatic vessels (115). Therefore, relevant treatment options may play a role in both HEVs and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels at the same time. For example, previous studies have shown that using anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in combination with antiangiogenic therapies (anti-VEGF or anti-VEGF/Ang2) resulted in a mutually beneficial effect in targeted antiangiogenic immunotherapy. More importantly, antiangiogenic immunotherapy successfully induced the generation of HEVs and inhibited the generation of tumor-associated lymphatic vessels. Moreover, the vascular normalization induced by antiangiogenic therapy increased lymphocyte infiltration and activation (75, 116, 117). Therefore, ICB combined with antiangiogenic drugs can be used in immunotherapy to simultaneously induce HEV production and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels inhibition. Another association between HEVs and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels is that they are both involved in transporting lymphocytes in the tumor tissue. Therefore, treating lymphocytes, especially CD8+ T cells, may simultaneously affect this complex trafficking mechanism. However, the exact mechanism needs exploration.

In this review, we focused on the entry and exit of lymphocytes into and out of tumor tissue through TA-HEVs and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels, respectively, and their impact on immunotherapeutic approaches. The special structure and function of TA-HEVs account for their role as the main site of lymphocyte extravasation into tumors during cancer immunity and immune checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. TA-HEVs have been identified in various human tumor tissues as a major portal for lymphocyte entry into the tumor and have been found to associate with TLS-rich regions. The induction of TA-HEVs may be associated with the recruitment of CD8+ T cells and may exert an inhibitory effect on tumor growth. However, tumor-associated lymphatic vessels play an important role in controlling the exit of lymphocytes from tumor tissues. The lymphatic vessel system controls the exit of lymphocytes from the tumor mainly through the synergistic differentiation of various chemokines and T cells, thus controlling the function and number of CD8+ T cells in the tumor immune microenvironment and inhibiting the immune effect to a certain extent.

Tumor cells evade human immune system surveillance by constructing various biophysical and biochemical barriers to block entry and promote the expulsion of immune cells such as lymphocytes. Also, lymphocytes are the key to tumor immunotherapy. The promotion of MECA-79+ TA-HEV production and the inhibition of CXCL12 work together to regulate the transport of lymphocytes in and out of the tumor as well as the number of immune cells such as CD8+ T cells and DCs, resulting in better therapeutic effect and prognosis for ICB combined therapy and other methods.

In summary, this review highlighted the importance of TA-HEVs and tumor-associated lymphatic vessels in immunotherapy and analyzed the two potential pathways regulating the flow of lymphocytes into and out of the TME. The modulation of these channels may be important for improving the efficacy of immunotherapy.

BD: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – review & editing. RZ: Writing – review & editing. FS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BW: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LL: Writing – review & editing. SZ: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from Liaoning Province Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no. 2024JH2/102500025) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82103338).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. (2013) 39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

2. Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Sci (New York NY). (2018) 359:1350–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060

3. Sharma P, Siddiqui BA, Anandhan S, Yadav SS, Subudhi SK, Gao J, et al. The next decade of immune checkpoint therapy. Cancer Discovery. (2021) 11:838–57. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1680

4. Blanchard L, Girard JP. High endothelial venules (HEVs) in immunity, inflammation and cancer. Angiogenesis. (2021) 24:719–53. doi: 10.1007/s10456-021-09792-8

5. Girard JP, Moussion C, Förster R. HEVs, lymphatics and homeostatic immune cell trafficking in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. (2012) 12:762–73. doi: 10.1038/nri3298

6. Moussion C, Girard JP. Dendritic cells control lymphocyte entry to lymph nodes through high endothelial venules. Nature. (2011) 479:542–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10540

7. Martinet L, Garrido I, Filleron T, Le Guellec S, Bellard E, Fournie JJ, et al. Human solid tumors contain high endothelial venules: association with T- and B-lymphocyte infiltration and favorable prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Res. (2011) 71:5678–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0431

8. Martinet L, Le Guellec S, Filleron T, Lamant L, Meyer N, Rochaix P, et al. High endothelial venules (HEVs) in human melanoma lesions: Major gateways for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology. (2012) 1:829–39. doi: 10.4161/onci.20492

9. Milutinovic S, Gallimore A. The link between T cell activation and development of functionally useful tumor-associated high endothelial venules. Discovery Immunol. (2023) 2:kyad006. doi: 10.1093/discim/kyad006

10. Steele MM, Jaiswal A, Delclaux I, Dryg ID, Murugan D, Femel J, et al. T cell egress via lymphatic vessels is tuned by antigen encounter and limits tumor control. Nat Immunol. (2023) 24:664–75. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01443-y

11. Swartz MA, Lund AW. Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumor microenvironment: linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. (2012) 12:210–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc3186

12. Uchimura K, Rosen SD. Sulfated L-selectin ligands as a therapeutic target in chronic inflammation. Trends Immunol. (2006) 27:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.10.007

13. Kobayashi M, Mitoma J, Nakamura N, Katsuyama T, Nakayama J, Fukuda M. Induction of peripheral lymph node addressin in human gastric mucosa infected by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2004) 101:17807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407503101

14. Wenk EJ, Orlic D, Reith EJ, Rhodin JA. The ultrastructure of mouse lymph node venules and the passage of lymphocytes across their walls. J ultrastructure Res. (1974) 47:214–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(74)80071-7

15. von Andrian UH. Intravital microscopy of the peripheral lymph node microcirculation in mice. Microcirculation. (1996) 3:287–300. doi: 10.3109/10739689609148303

16. Milutinovic S, Abe J, Godkin A, Stein JV, Gallimore A. The dual role of high endothelial venules in cancer progression versus immunity. Trends Cancer. (2021) 7:214–25. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.10.001

17. Kawashima H, Petryniak B, Hiraoka N, Mitoma J, Huckaby V, Nakayama J, et al. N-acetylglucosamine-6-O-sulfotransferases 1 and 2 cooperatively control lymphocyte homing through L-selectin ligand biosynthesis in high endothelial venules. Nat Immunol. (2005) 6:1096–104. doi: 10.1038/ni1259

18. Streeter PR, Rouse BT, Butcher EC. Immunohistologic and functional characterization of a vascular addressin involved in lymphocyte homing into peripheral lymph nodes. J Cell Biol. (1988) 107:1853–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1853

19. Michie SA, Streeter PR, Bolt PA, Butcher EC, Picker LJ. The human peripheral lymph node vascular addressin. An inducible endothelial antigen involved in lymphocyte homing. Am J Pathol. (1993) 143:1688–98.

20. Girard JP, Springer TA. High endothelial venules (HEVs): specialized endothelium for lymphocyte migration. Immunol Today. (1995) 16:449–57. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80023-9

21. Anderson AO, Anderson ND. Studies on the structure and permeability of the microvasculature in normal rat lymph nodes. Am J Pathol. (1975) 80:387–418.

22. Anderson AO, Shaw S. T cell adhesion to endothelium: the FRC conduit system and other anatomic and molecular features which facilitate the adhesion cascade in lymph node. Semin Immunol. (1993) 5:271–82. doi: 10.1006/smim.1993.1031

23. Rosen SD. Ligands for L-selectin: homing, inflammation, and beyond. Annu Rev Immunol. (2004) 22:129–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.090501.080131

24. Drayton DL, Ying X, Lee J, Lesslauer W, Ruddle NH. Ectopic LT alpha beta directs lymphoid organ neogenesis with concomitant expression of peripheral node addressin and a HEV-restricted sulfotransferase. J Exp Med. (2003) 197:1153–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021761

25. Sacca R, Cuff CA, Lesslauer W, Ruddle NH. Differential activities of secreted lymphotoxin-alpha3 and membrane lymphotoxin-alpha1beta2 in lymphotoxin-induced inflammation: critical role of TNF receptor 1 signaling. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950). (1998) 160:485–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.160.1.485

26. Browning JL, Allaire N, Ngam-Ek A, Notidis E, Hunt J, Perrin S, et al. Lymphotoxin-beta receptor signaling is required for the homeostatic control of HEV differentiation and function. Immunity. (2005) 23:539–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.002

27. Onder L, Danuser R, Scandella E, Firner S, Chai Q, Hehlgans T, et al. Endothelial cell-specific lymphotoxin-β receptor signaling is critical for lymph node and high endothelial venule formation. J Exp Med. (2013) 210:465–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121462

28. Xiong Y, Hla T. S1P control of endothelial integrity. Curr topics Microbiol Immunol. (2014) 378:85–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05879-5_4

29. Simmons S, Sasaki N, Umemoto E, Uchida Y, Fukuhara S, Kitazawa Y, et al. High-endothelial cell-derived S1P regulates dendritic cell localization and vascular integrity in the lymph node. eLife. (2019) 8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41239

30. Hasan Z, Nguyen TQ, Lam BWS, Wong JHX, Wong CCY, Tan CKH, et al. Postnatal deletion of Spns2 prevents neuroinflammation without compromising blood vascular functions. Cell Mol Life sciences: CMLS. (2022) 79:541. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04573-y

31. Ager A, May MJ. Understanding high endothelial venules: Lessons for cancer immunology. Oncoimmunology. (2015) 4:e1008791. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1008791

32. Barnes JA, Redd R, Fisher DC, Hochberg EP, Takvorian T, Neuberg D, et al. Panobinostat in combination with rituximab in heavily pretreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II study. Hematological Oncol. (2018) 36:633–7. doi: 10.1002/hon.v36.4

33. Piao W, Kasinath V, Saxena V, Lakhan R, Iyyathurai J, Bromberg JS. LTβR signaling controls lymphatic migration of immune cells. Cells. (2021) 10. doi: 10.3390/cells10040747

34. Norris PS, Ware CF. The LT beta R signaling pathway. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2007) 597:160–72. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-70630-6_13

35. Waisman A, Lukas D, Clausen BE, Yogev N. Dendritic cells as gatekeepers of tolerance. Semin Immunopathol. (2017) 39:153–63. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0583-z

36. Ware CF. Network communications: lymphotoxins, LIGHT, and TNF. Annu Rev Immunol. (2005) 23:787–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115719

37. du Bois H, Heim TA, Lund AW. Tumor-draining lymph nodes: At the crossroads of metastasis and immunity. Sci Immunol. (2021) 6:eabg3551. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg3551

38. Morisaki T, Morisaki T, Kubo M, Morisaki S, Nakamura Y, Onishi H. Lymph nodes as anti-tumor immunotherapeutic tools: intranodal-tumor-specific antigen-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14. doi: 10.3390/cancers14102438

39. Riedel A, Helal M, Pedro L, Swietlik JJ, Shorthouse D, Schmitz W, et al. Tumor-derived lactic acid modulates activation and metabolic status of draining lymph node stroma. Cancer Immunol Res. (2022) 10:482–97. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-0778

40. Bekkhus T, Martikainen T, Olofsson A, Franzén Boger M, Vasiliu Bacovia D, Wärnberg F, et al. Remodeling of the lymph node high endothelial venules reflects tumor invasiveness in breast cancer and is associated with dysregulation of perivascular stromal cells. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13. doi: 10.3390/cancers13020211

41. Bao X, Moseman EA, Saito H, Petryniak B, Thiriot A, Hatakeyama S, et al. Endothelial heparan sulfate controls chemokine presentation in recruitment of lymphocytes and dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Immunity. (2010) 33:817–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.018

42. Tsuboi K, Hirakawa J, Seki E, Imai Y, Yamaguchi Y, Fukuda M, et al. Role of high endothelial venule-expressed heparan sulfate in chemokine presentation and lymphocyte homing. J Immunol. (2013) 191:448–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203061

43. Okada T, Ngo VN, Ekland EH, Förster R, Lipp M, Littman DR, et al. Chemokine requirements for B cell entry to lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. (2002) 196:65–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020201

44. Gunn MD, Tangemann K, Tam C, Cyster JG, Rosen SD, Williams LT. A chemokine expressed in lymphoid high endothelial venules promotes the adhesion and chemotaxis of naive T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1998) 95:258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.258

45. Ebisuno Y, Tanaka T, Kanemitsu N, Kanda H, Yamaguchi K, Kaisho T, et al. Cutting edge: the B cell chemokine CXC chemokine ligand 13/B lymphocyte chemoattractant is expressed in the high endothelial venules of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches and affects B cell trafficking across high endothelial venules. J Immunol. (2003) 171:1642–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1642

46. Stein JV, Rot A, Luo Y, Narasimhaswamy M, Nakano H, Gunn MD, et al. The CC chemokine thymus-derived chemotactic agent 4 (TCA-4, secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine, 6Ckine, exodus-2) triggers lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1-mediated arrest of rolling T lymphocytes in peripheral lymph node high endothelial venules. J Exp Med. (2000) 191:61–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.61

47. Scimone ML, Felbinger TW, Mazo IB, Stein JV, Von Andrian UH, Weninger W. CXCL12 mediates CCR7-independent homing of central memory cells, but not naive T cells, in peripheral lymph nodes. J Exp Med. (2004) 199:1113–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031645

48. Shamri R, Grabovsky V, Gauguet JM, Feigelson S, Manevich E, Kolanus W, et al. Lymphocyte arrest requires instantaneous induction of an extended LFA-1 conformation mediated by endothelium-bound chemokines. Nat Immunol. (2005) 6:497–506. doi: 10.1038/ni1194

49. Bajénoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, et al. Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration, and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity. (2006) 25:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.011

50. Schoefl GI. The migration of lymphocytes across the vascular endothelium in lymphoid tissue. A reexamination. J Exp Med. (1972) 136:568–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.3.568

51. Chai Q, Onder L, Scandella E, Gil-Cruz C, Perez-Shibayama C, Cupovic J, et al. Maturation of lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells from myofibroblastic precursors is critical for antiviral immunity. Immunity. (2013) 38:1013–24. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.012

52. Asrir A, Tardiveau C, Coudert J, Laffont R, Blanchard L, Bellard E, et al. Tumor-associated high endothelial venules mediate lymphocyte entry into tumors and predict response to PD-1 plus CTLA-4 combination immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. (2022) 40:318–334.e319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.01.002

53. Hendriks HR, Duijvestijn AM, Kraal G. Rapid decrease in lymphocyte adherence to high endothelial venules in lymph nodes deprived of afferent lymphatic vessels. Eur J Immunol. (1987) 17:1691–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171203

54. Lauder SN, Smart K, Kersemans V, Allen D, Scott J, Pires A, et al. Enhanced antitumor immunity through sequential targeting of PI3Kδ and LAG3. J immunotherapy Cancer. (2020) 8. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000693

55. Vella G, Guelfi S, Bergers G. High endothelial venules: A vascular perspective on tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:736670. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.736670

56. Harder R, Uhlig H, Kashan A, Schütt B, Duijvestijn A, Butcher EC, et al. Dissection of murine lymphocyte-endothelial cell interaction mechanisms by SV-40-transformed mouse endothelial cell lines: novel mechanisms mediating basal binding, and alpha 4-integrin-dependent cytokine-induced adhesion. Exp Cell Res. (1991) 197:259–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90431-S

57. Zhan Z, Shi-Jin L, Yi-Ran Z, Zhi-Long L, Xiao-Xu Z, Hui D, et al. High endothelial venules proportion in tertiary lymphoid structure is a prognostic marker and correlated with anti-tumor immune microenvironment in colorectal cancer. Ann Med. (2023) 55:114–26. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2153911

58. Peske JD, Thompson ED, Gemta L, Baylis RA, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Effector lymphocyte-induced lymph node-like vasculature enables naive T-cell entry into tumors and enhanced anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:7114. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8114

59. Sautès-Fridman C, Petitprez F, Calderaro J, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2019) 19:307–25. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0144-6

60. Dieu-Nosjean MC, Goc J, Giraldo NA, Sautès-Fridman C, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol. (2014) 35:571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.09.006

61. Low S, Sakai Y, Hoshino H, Hirokawa M, Kawashima H, Higuchi K, et al. High endothelial venule-like vessels and lymphocyte recruitment in diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Pathology. (2016) 48:666–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2016.08.002

62. Hussain B, Kasinath V, Ashton-Rickardt GP, Clancy T, Uchimura K, Tsokos G, et al. High endothelial venules as potential gateways for therapeutics. Trends Immunol. (2022) 43:728–40. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2022.07.002

63. Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. (2017) 541:321–30. doi: 10.1038/nature21349

64. Martinet L, Garrido I, Girard JP. Tumor high endothelial venules (HEVs) predict lymphocyte infiltration and favorable prognosis in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. (2012) 1:789–90. doi: 10.4161/onci.19787

65. Martinet L, Girard JP. Regulation of tumor-associated high-endothelial venules by dendritic cells: A new opportunity to promote lymphocyte infiltration into breast cancer? Oncoimmunology. (2013) 2:e26470. doi: 10.4161/onci.26470

66. Hua Y, Vella G, Rambow F, Allen E, Antoranz Martinez A, Duhamel M, et al. Cancer immunotherapies transition endothelial cells into HEVs that generate TCF1(+) T lymphocyte niches through a feed-forward loop. Cancer Cell. (2022) 40:1600–1618.e1610. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.11.002

67. Martinet L, Filleron T, Le Guellec S, Rochaix P, Garrido I, Girard JP. High endothelial venule blood vessels for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with lymphotoxin β-producing dendritic cells in human breast cancer. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950). (2013) 191:2001–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300872

68. Johansson-Percival A, He B, Li ZJ, Kjellén A, Russell K, Li J, et al. De novo induction of intratumoral lymphoid structures and vessel normalization enhances immunotherapy in resistant tumors. Nat Immunol. (2017) 18:1207–17. doi: 10.1038/ni.3836

69. Colbeck EJ, Jones E, Hindley JP, Smart K, Schulz R, Browne M, et al. Treg depletion licenses T cell-driven HEV neogenesis and promotes tumor destruction. Cancer Immunol Res. (2017) 5:1005–15. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0131

70. Bravo AI, Aris M, Panouillot M, Porto M, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Teillaud JL, et al. HEV-associated dendritic cells are observed in metastatic tumor-draining lymph nodes of cutaneous melanoma patients with longer distant metastasis-free survival after adjuvant immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1231734. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1231734

71. Wendland M, Willenzon S, Kocks J, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Hammerschmidt SI, Schumann K, et al. Lymph node T cell homeostasis relies on steady state homing of dendritic cells. Immunity. (2011) 35:945–57. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.017

72. Webster B, Ekland EH, Agle LM, Chyou S, Ruggieri R, Lu TT. Regulation of lymph node vascular growth by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. (2006) 203:1903–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052272

73. Hindley JP, Jones E, Smart K, Bridgeman H, Lauder SN, Ondondo B, et al. T-cell trafficking facilitated by high endothelial venules is required for tumor control after regulatory T-cell depletion. Cancer Res. (2012) 72:5473–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1912

74. Ye D, Jin Y, Weng Y, Cui X, Wang J, Peng M, et al. High endothelial venules predict response to PD-1 inhibitors combined with anti-angiogenesis therapy in NSCLC. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:16468. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-43122-w

75. Allen E, Jabouille A, Rivera LB, Lodewijckx I, Missiaen R, Steri V, et al. Combined antiangiogenic and anti-PD-L1 therapy stimulates tumor immunity through HEV formation. Sci Transl Med. (2017) 9(385):eaak9679. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aak9679

76. Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. (2014) 515:568–71. doi: 10.1038/nature13954

77. Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, Williams J, Meng Y, Ha TT, et al. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and T(regs) in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8(+) T cells. Sci Trans Med. (2013) 5:200ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006504

78. Steele MM, Lund AW. Afferent lymphatic transport and peripheral tissue immunity. J Immunol. (2021) 206:264–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2001060

79. Lund AW, Duraes FV, Hirosue S, Raghavan VR, Nembrini C, Thomas SN, et al. VEGF-C promotes immune tolerance in B16 melanomas and cross-presentation of tumor antigen by lymph node lymphatics. Cell Rep. (2012) 1:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.01.005

80. Gkountidi AO, Garnier L, Dubrot J, Angelillo J, Harlé G, Brighouse D, et al. MHC class II antigen presentation by lymphatic endothelial cells in tumors promotes intratumoral regulatory T cell-suppressive functions. Cancer Immunol Res. (2021) 9:748–64. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0784

81. Garnier L, Pick R, Montorfani J, Sun M, Brighouse D, Liaudet N, et al. IFN-γ-dependent tumor-antigen cross-presentation by lymphatic endothelial cells promotes their killing by T cells and inhibits metastasis. Sci Adv. (2022) 8:eabl5162. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl5162

82. Lane RS, Femel J, Breazeale AP, Loo CP, Thibault G, Kaempf A, et al. IFNγ-activated dermal lymphatic vessels inhibit cytotoxic T cells in melanoma and inflamed skin. J Exp Med. (2018) 215:3057–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180654

83. Tomura M, Yoshida N, Tanaka J, Karasawa S, Miwa Y, Miyawaki A, et al. Monitoring cellular movement in vivo with photoconvertible fluorescence protein “Kaede” transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2008) 105:10871–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802278105

84. Steele MM, Churchill MJ, Breazeale AP, Lane RS, Nelson NA, Lund AW. Quantifying leukocyte egress via lymphatic vessels from murine skin and tumors. J Vis Exp. (2019) 143). doi: 10.3791/58704-v

85. Kabashima K, Shiraishi N, Sugita K, Mori T, Onoue A, Kobayashi M, et al. CXCL12-CXCR4 engagement is required for migration of cutaneous dendritic cells. Am J Pathol. (2007) 171:1249–57. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070225

86. Schmidt TH, Bannard O, Gray EE, Cyster JG. CXCR4 promotes B cell egress from Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. (2013) 210:1099–107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122574

87. Chen IX, Chauhan VP, Posada J, Ng MR, Wu MW, Adstamongkonkul P, et al. Blocking CXCR4 alleviates desmoplasia, increases T-lymphocyte infiltration, and improves immunotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2019) 116:4558–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815515116

88. Gómez D, Diehl MC, Crosby EJ, Weinkopff T, Debes GF. Effector T cell egress via afferent lymph modulates local tissue inflammation. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950). (2015) 195:3531–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500626

89. Di Pilato M, Kfuri-Rubens R, Pruessmann JN, Ozga AJ, Messemaker M, Cadilha BL, et al. CXCR6 positions cytotoxic T cells to receive critical survival signals in the tumor microenvironment. Cell. (2021) 184:4512–4530.e4522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.015

90. Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, Wells RJ, Deonarine A, Chan DS, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2013) 110:20212–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110

91. Utzschneider DT, Charmoy M, Chennupati V, Pousse L, Ferreira DP, Calderon-Copete S, et al. T cell factor 1-expressing memory-like CD8(+) T cells sustain the immune response to chronic viral infections. Immunity. (2016) 45:415–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.021

92. Bengsch B, Ohtani T, Khan O, Setty M, Manne S, O’Brien S, et al. Epigenomic-Guided mass cytometry profiling reveals disease-Specific features of exhausted CD8 T cells. Immunity. (2018) 48:1029–1045.e1025. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.026

93. Siddiqui I, Schaeuble K, Chennupati V, Fuertes Marraco SA, Calderon-Copete S, Pais Ferreira D, et al. Intratumoral tcf1(+)PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells with stem-like properties promote tumor control in response to vaccination and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Immunity. (2019) 50:195–211.e110. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.021

94. Chen Y, Ramjiawan RR, Reiberger T, Ng MR, Hato T, Huang Y, et al. CXCR4 inhibition in tumor microenvironment facilitates anti-programmed death receptor-1 immunotherapy in sorafenib-treated hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatol (Baltimore Md). (2015) 61:1591–602. doi: 10.1002/hep.27665

95. Connolly KA, Kuchroo M, Venkat A, Khatun A, Wang J, William I, et al. Kasmani MY et al: A reservoir of stem-like CD8(+) T cells in the tumor-draining lymph node preserves the ongoing antitumor immune response. Sci Immunol. (2021) 6:eabg7836. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg7836

96. Stacker SA, Williams SP, Karnezis T, Shayan R, Fox SB, Achen MG. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic vessel remodeling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2014) 14:159–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc3677

97. Achen MG, Jeltsch M, Kukk E, Mäkinen T, Vitali A, Wilks AF, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) is a ligand for the tyrosine kinases VEGF receptor 2 (Flk1) and VEGF receptor 3 (Flt4). Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (1998) 95:548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.548

98. Joukov V, Pajusola K, Kaipainen A, Chilov D, Lahtinen I, Kukk E, et al. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. (1996) 15:290–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00359.x

99. Dieterich LC, Tacconi C, Ducoli L, Detmar M. Lymphatic vessels in cancer. Physiol Rev. (2022) 102:1837–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2021

100. Song E, Mao T, Dong H, Boisserand LSB, Antila S, Bosenberg M, et al. VEGF-C-driven lymphatic drainage enables immunosurveillance of brain tumors. Nature. (2020) 577:689–94. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1912-x

101. Suffee N, Hlawaty H, Meddahi-Pelle A, Maillard L, Louedec L, Haddad O, et al. Oudar O et al: RANTES/CCL5-induced pro-angiogenic effects depend on CCR1, CCR5 and glycosaminoglycans. Angiogenesis. (2012) 15:727–44. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9285-x

102. Liu GT, Chen HT, Tsou HK, Tan TW, Fong YC, Chen PC, et al. CCL5 promotes VEGF-dependent angiogenesis by down-regulating miR-200b through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. Oncotarget. (2014) 5:10718–31. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.v5i21

103. Wang SW, Liu SC, Sun HL, Huang TY, Chan CH, Yang CY, et al. CCL5/CCR5 axis induces vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated tumor angiogenesis in human osteosarcoma microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. (2015) 36:104–14. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu218

104. Sax MJ, Gasch C, Athota VR, Freeman R, Rasighaemi P, Westcott DE, et al. Cancer cell CCL5 mediates bone marrow independent angiogenesis in breast cancer. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:85437–49. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13387

105. Wang LH, Lin CY, Liu SC, Liu GT, Chen YL, Chen JJ, et al. CCL5 promotes VEGF-C production and induces lymphangiogenesis by suppressing miR-507 in human chondrosarcoma cells. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:36896–908. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.v7i24

106. Lien MY, Tsai HC, Chang AC, Tsai MH, Hua CH, Wang SW, et al. Chemokine CCL4 induces vascular endothelial growth factor C expression and lymphangiogenesis by miR-195-3p in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:412. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00412

107. Korbecki J, Grochans S, Gutowska I, Barczak K, Baranowska-Bosiacka I. CC chemokines in a tumor: A review of pro-cancer and anti-cancer properties of receptors CCR5, CCR6, CCR7, CCR8, CCR9, and CCR10 ligands. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207619

108. Siironen P, Ristimäki A, Narko K, Nordling S, Louhimo J, Andersson S, et al. VEGF-C and COX-2 expression in papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine-related Cancer. (2006) 13:465–73. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01114

109. Soumaoro LT, Uetake H, Takagi Y, Iida S, Higuchi T, Yasuno M, et al. Coexpression of VEGF-C and Cox-2 in human colorectal cancer and its association with lymph node metastasis. Dis colon rectum. (2006) 49:392–8. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0247-x

110. Timoshenko AV, Chakraborty C, Wagner GF, Lala PK. COX-2-mediated stimulation of the lymphangiogenic factor VEGF-C in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. (2006) 94:1154–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603067

111. Zhang XH, Huang DP, Guo GL, Chen GR, Zhang HX, Wan L, et al. Coexpression of VEGF-C and COX-2 and its association with lymphangiogenesis in human breast cancer. BMC Cancer. (2008) 8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-4

112. Elmets CA, Ledet JJ, Athar M. Cyclooxygenases: mediators of UV-induced skin cancer and potential targets for prevention. J Invest Dermatol. (2014) 134:2497–502. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.192

113. Karnezis T, Shayan R, Fox S, Achen MG, Stacker SA. The connection between lymphangiogenic signaling and prostaglandin biology: a missing link in the metastatic pathway. Oncotarget. (2012) 3:893–906. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.v3i8

114. Kataru RP, Kim H, Jang C, Choi DK, Koh BI, Kim M, et al. T lymphocytes negatively regulate lymph node lymphatic vessel formation. Immunity. (2011) 34:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.016

115. Schaaf MB, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Defining the role of the tumor vasculature in antitumor immunity and immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. (2018) 9:115. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0061-0

116. Mazzone M, Bergers G. Regulation of blood and lymphatic vessels by immune cells in tumors and metastasis. Annu Rev Physiol. (2019) 81:535–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114721

Keywords: CD8 + T cells, tumor-associated high endothelial venules, immunotherapy, tumor-associated lymphatic vessels, lymphocytes

Citation: Du B, Geng J, Wu B, Wang H, Luo R, Liu H, Zhang R, Shan F, Liu L and Zhang S (2025) Pipelines for lymphocyte homeostasis maintenance during cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 16:1522417. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1522417

Received: 04 November 2024; Accepted: 27 February 2025;

Published: 24 March 2025.

Edited by:

Shahram Salek-Ardakani, Inhibrx, United StatesReviewed by:

Hiroto Kawashima, Chiba University, JapanCopyright © 2025 Du, Geng, Wu, Wang, Luo, Liu, Zhang, Shan, Liu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuling Zhang, c2x6aGFuZ0BjbXUuZWR1LmNu; Lei Liu, bGl1bGVpY211MmhAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.