95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 15 December 2021

Sec. Comparative Immunology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.775708

This article is part of the Research Topic Immunity to Emerging Pathogens in Poikilothermic Vertebrates View all 9 articles

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Dual RNA-seq of trunk kidneys extracted from channel catfish infected with Yersinia ruckeri reveals novel insights into host-pathogen interactions

Host-pathogen intectarions are complex, involving large dynamic changes in gene expression through the process of infection. These interactions are essential for understanding anti-infective immunity as well as pathogenesis. In this study, the host-pathogen interaction was analyzed using a model of acute infection where channel catfish were infected with Yersinia ruckeri. The infected fish showed signs of body surface hyperemia as well as hyperemia and swelling in the trunk kidney. Double RNA sequencing was performed on trunk kidneys extracted from infected channel catfish and transcriptome data was compared with data from uninfected trunk kidneys. Results revealed that the host-pathogen interaction was dynamically regulated and that the host-pathogen transcriptome fluctuated during infection. More specifically, these data revealed that the expression levels of immune genes involved in Cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, the NF-kappa B signaling pathway, the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling and other immune-related pathways were significantly upregulated. Y. ruckeri mainly promote pathogenesis through the flagellum gene fliC in channel catfish. The weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) R package was used to reveal that the infection of catfish is closely related to metabolic pathways. This study contributes to the understanding of the host-pathogen interaction between channel catfish and Y. ruckeri, more specifically how catfish respond to infection through a transcriptional perspective and how this infection leads to enteric red mouth disease (ERM) in these fish.

Aquaculture is one of the most dynamic sectors in the global food system and has made significant contributions to the production of protein rich food consumed by humans (1). The global aquaculture industry has grown by 5% annually over the past 20 years (2, 3). However, more recently, the practice of aquaculture has encountered many challenges, one being disease outbreak caused by microbial pathogens (4). Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) were introduced to China from the United States in 1984. After adapting to the environment in China, there was an explosive growth rate in the breeding yield and area. Channel catfish are a major component of freshwater fish culture in China. However, disease in these fish lead to a bottleneck restricting further growth of the channel catfish industry. The main pathogenic microorganisms infecting channel catfish include Aeromonas hydrophila, Yersinia ruckeri, Edwardsiella ictaluri and Streptococcus iniae, which have resulted in great economic loss for the aquaculture industry (4–10). Y. ruckeri is a gram-negative bacterium and the cause of enteric red mouth disease (ERM) in fish (11). ERM is a serious disease prevalent in aquaculture worldwide and is commonly observed in rainbow trout, sturgeon and channel catfish (12–16).

Sick channel catfish show sepsis and inflammation in most organs, including the trunk kidney, spleen, liver and gastrointestinal tract (6). During the early stage of infection, the pathogen may invade into the gills and gastrointestinal epitheliums. Later, the infection may enter the blood circulation system and infect the spleen and trunk kidney, accumulate in the lymphoid organs and finally destroy the immune system (17). Y. ruckeri is a facultative, intracellular pathogen that can survive in macrophages in vitro and in vivo. In fact, there is quite a bit more to understand about the physiology of Y. ruckeri since most research has been focused on single virulence factors, such as extracellular toxins, high affinity iron uptake systems and resistance to innate immune mechanisms (18–26). Liu et al. identified that Toll/IL-1 receptors containing the proteins stir-1, stir-2 and stir-3 synergistically assisted the immune escape of Y. ruckeri SC09 (27, 28). This study also found that the virulence protein of Y. ruckeri TIR mediated immune escape by targeting the MyD88 receptor (29). The molecular mechanisms behind the infection of channel catfish by Y. ruckeri is still not very clear.

Infection is a life and death struggle between the host and its pathogen (30). In this struggle, both the pathogen and host must mobilize all of their available resources to win (31). The transcriptomic profiles for both the host and pathogen vastly alter during the infection process (32, 33). Traditional RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technology only reflects the host transcriptome (34) and does not detect the host and pathogen transcriptome simultaneously. However, dual RNA-seq can provide analysis of the interaction between the host and pathogen transcriptomes. Dual RNA-seq has been used to study a variety of bacterial infections, including cell and animal infection models and has identified many key genes related to host-pathogen interactions (35).

To better understand the interaction between channel catfish and Y. ruckeri, an infection model was established to analyze dual RNA-seq data of the trunk kidney at different stages of infection and to monitor changes in the transcriptomes of both channel catfish and Y. ruckeri. Results obtained during this study will better clarify the host-pathogen interaction between channel catfish and Y. ruckeri.

This study was performed strictly in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals for scientific purposes formulated by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee of Changjiang Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences.

All healthy and moderate size (100 ± 20 g) channel catfish were purchased from Wuhan Baishazhou aquatic market. These fish were domesticated for one week at a temperature of 25 ± 1°C under laboratory conditions free of specific pathogens before infection. The pathogenic Y. ruckeri YZ strain (GenBank accession number is OL376599) was isolated from infected channel catfish. Y. ruckeri was cultured on a nutrient agar plate at 28°C; for 18 h, washed with sterile PBS, blown evenly, diluted to 108 CFU/mL and then inoculated in healthy channel catfish. A bacterial sample was also collected as a control. The experimental group was injected with 105 CFU/g of Y. ruckeri through the base of channel catfish ventral fin, and 100 fishes were used in the experimental group and the control group respectively. The same volume of sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was injected into the same area of the channel catfish for the control group. The water temperature was maintained at 25°C throughout the experiment. The dynamics of the catfish were observed and recorded every 6h, which swimming behavior, symptom, mortality and so on. The preliminary experiments had confirmed that channel catfish can be successfully infected by Y. ruckeri at 6,12,24 hour post-injection(hpi). For dual RNA-seq assays, the trunk kidneys of 15 infected channel catfish were sampled at 6, 12 and 24 hpi. Five trunk kidneys were mixed as one sample. PBS-treated channel catfish and in vitrocultured Y. ruckeri (28°C) were used as controls. These experimental samples were then fixed using Trizol to extract total RNA.

Total RNA from trunk kidneys and Y. ruckeri were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). A turbo DNA free DNase (Abion, USA) treatment was performed to remove possible contaminated genomic DNA. RNA samples were further purified using the RNA zero RNA Removal Kit (human/mouse/rat or Gram-negative bacteria) (Epicentre, USA). Samples of mRNA were then fragmented and cDNA was synthesized using a superscript double stranded cDNA synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, USA). After modification and purification, the enriched library fragments were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The library quality was analyzed using an Agilent 2100 biological analyzer (Agilent technology, USA). Second generation sequencing was performed using an Illumina novaseq sequencing platform.

The obtained reads were cleared using fastqc software (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and the content and quality of the remaining cleaning reads were evaluated. Low-quality reads and 3’ adapter sequences were removed using Trim Galore. A comparative analysis was then performed using the reference genome of channel catfish and Y. ruckeri. For each sample belonging to the experimental and control groups, TopHat was used to align the reference genome sequence (16, 36).

To evaluate the transcript expression levels in the different groups, rsem software with default parameter settings was used to estimate the expression levels (relative abundance) of specific transcripts mapped per million fragments per thousand base transcripts (frkm) (37, 38). The expression levels of each transcript were transformed using base log2 (fpkm + 1). DESeq software was used to screen DEGs and calculate the fold changes of transcripts (39). Two-fold changes were considered for further study and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To analyze the potential functions of DEGs, we first annotated them as depicted on the uniprot database (http://www.uniprot.org/). Then, the DEGs were functionally annotated using gene ontology (GO) terms (http://www.geneontology.org) with the use of Blast2GO (https://www.blast2go.com/) (40). All DEGs were mapped to GO terms in the GO database and the number of genes for every term was calculated. A hypergeometric test was used to detect the enriched GO terms of the DEGs when compared with the transcriptome background, as follows:

In this formula, n represents the number of genes annotated with GO. N represents the number of DEGs in n, which is the number of genes mismatched with the annotation of specific GO terms. M is the number of DEGs. The calculated p value was subjected to Bonferroni correction. The corrected p value of 0.05 was determined as the threshold for statistical significance. When the corrected p value was < 0.05, the GO term was considered as significantly enriched.

The pathway analysis for the DEGs was annotated using blastall (http://nebc.nox.ac.uk/bioinformatics/docs/blastall.html) against the yoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) database. The enriched DEG pathways were determined using the same formula as used for GO analysis. In this formula, n represents the number of genes annotated using KEGG, N represents the number of DEGs in n, MRE represents the number of genes annotated by a specific pathway and M represents the number of DEGs.

The WGCNA package in R was used to analyze the data (41). WGCNA helps identify functional pathways when studying interactions between species (42). The top 25% of genes were selected for WGCNA. A network was created based on results of the picksoftthreshold function. Hierarchical clustering and dynamic branch cutting were used to determine the stable module of tight junction genes. A hub gene was defined by module connectivity and measured by the absolute value of Pearson correlation. Hub genes in the module were considered to have functional significance. Key modules were visualized using Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

qRT-PCR was used to confirm the expression levels of DEGs identified by RNA-seq analysis. Primers used are listed in Table 1 (43–48). In channel catfish, EF-1 α was used as an endogenous control whereas gyrB was used for Y. ruckeri. qRT-PCR was performed using quantum Studio 6 flex (life technologies, USA) and melting curves were generated at the end of the run to confirm specificity. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the relative levels of DEGs (49).

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. SPSS 22 (American SPSS company) was used for data analysis. Independent sample t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett tests were used. A p value less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

The q20% and q30% of the sequencing data for each sample were between 96.01% ~ 98.63% and 89.32% ~ 96.22%, indicating that the overall sequencing quality was optimal and could be used for subsequent analysis (Table 2).

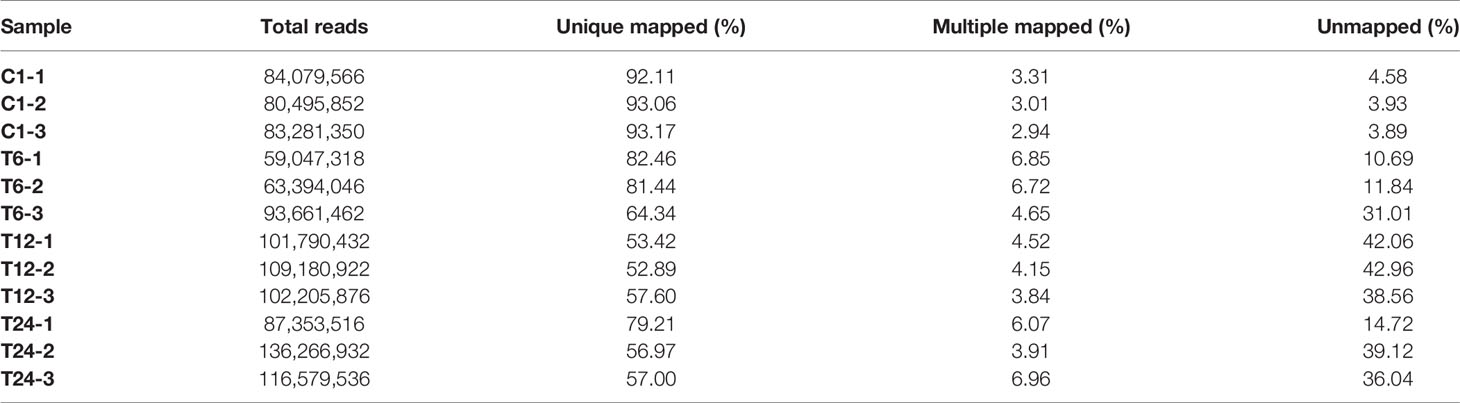

Fish and bacterial samples were compared with channel catfish GCF_ 001660625.1 and Y. ruckeri jrwx01000000 reference genomes (Tables 3 and 4). The proportion of the two samples that could be compared to a single location was greater than 95% and the proportion of multiple locations was low, indicating that the sequencing quality was sufficient for further analysis.

Table 3 Statistical results for mapping the trimmed reads with the channel catfish reference genome.

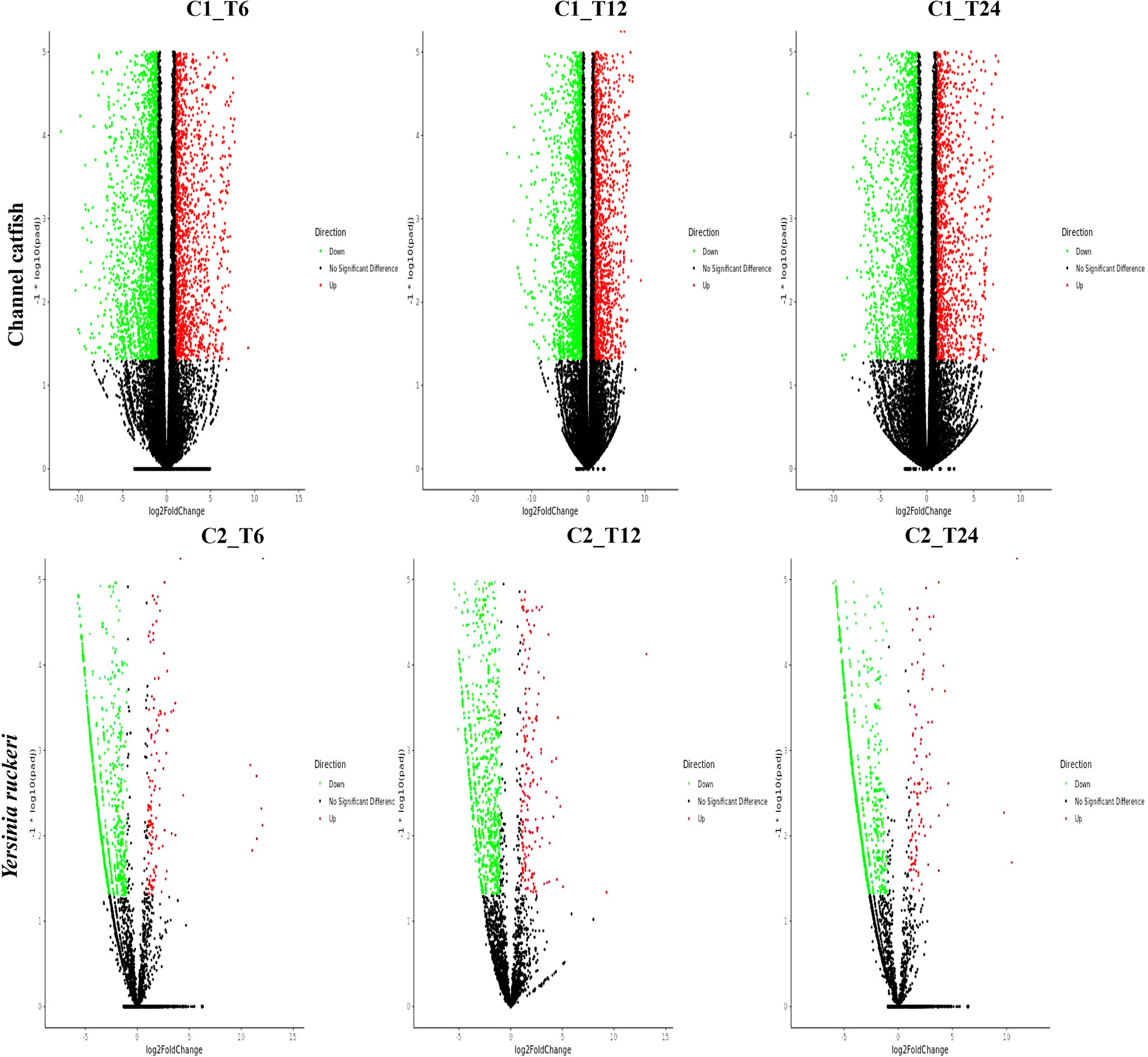

To study and compare the DEGs between control fish and infected fish or the pathogen which infected fish and the pathogen before infection, a gene expression profile was generated using the cuffdiff program (Figures 1 and 2). Transcriptome sequencing revealed that 4628 DEGs were upregulated and4281 DEGs were downregulated at 6 hpi in the trunk kidney. At 12 hpi, the trunk kidney showed a significant increase in 4494 DEGs and decrease in 4463 DEGs. At 24 hpi, 4028 DEGs were upregulated and 4235 DEGs were downregulated in the trunk kidney. For Y. ruckeri a significant upregulation in 294 DEGs and downregulation in 994 DEGs were observed at 6 hpi. At 12 hpi, 346 DEGs were significantly upregulated and 975 DEGs were significantly downregulated in Y. ruckeri. At 24 hpi, 200 DEGs were upregulated and 1212 DEG were downregulated in Y. ruckeri. These results showed a strong interaction and reaction between the host and pathogen during the infection.

Figure 1 The gene expression profiles for channel catfish and Y. ruckeri during infection. A volcanic plot depicting the differences in the expression profiles of channel catfish and Y. ruckeri. The X-axis represents a log2 (fold change) and the Y-axis represents -log10 (p value). Red represents significantly upregulated genes whereas green represents significantly downregulated genes. Each dot represents a single gene. C1_T6(C2_T6) represents 6 hpi, C1_T12(C2_T12) represents the 12 hpi and C1_T24 (C2_T24) stands for 24 hpi.

Figure 2 The gene expression profiles for channel catfish and Y. ruckeri using pattern clustering. Red represents the upregulated genes, green represents the downregulated genes. Each line represents a single gene. C1 and C2 as control group, T6, T12 and T24 represents the experimental group in 6 hpi, 12 hpi and 24 hpi.

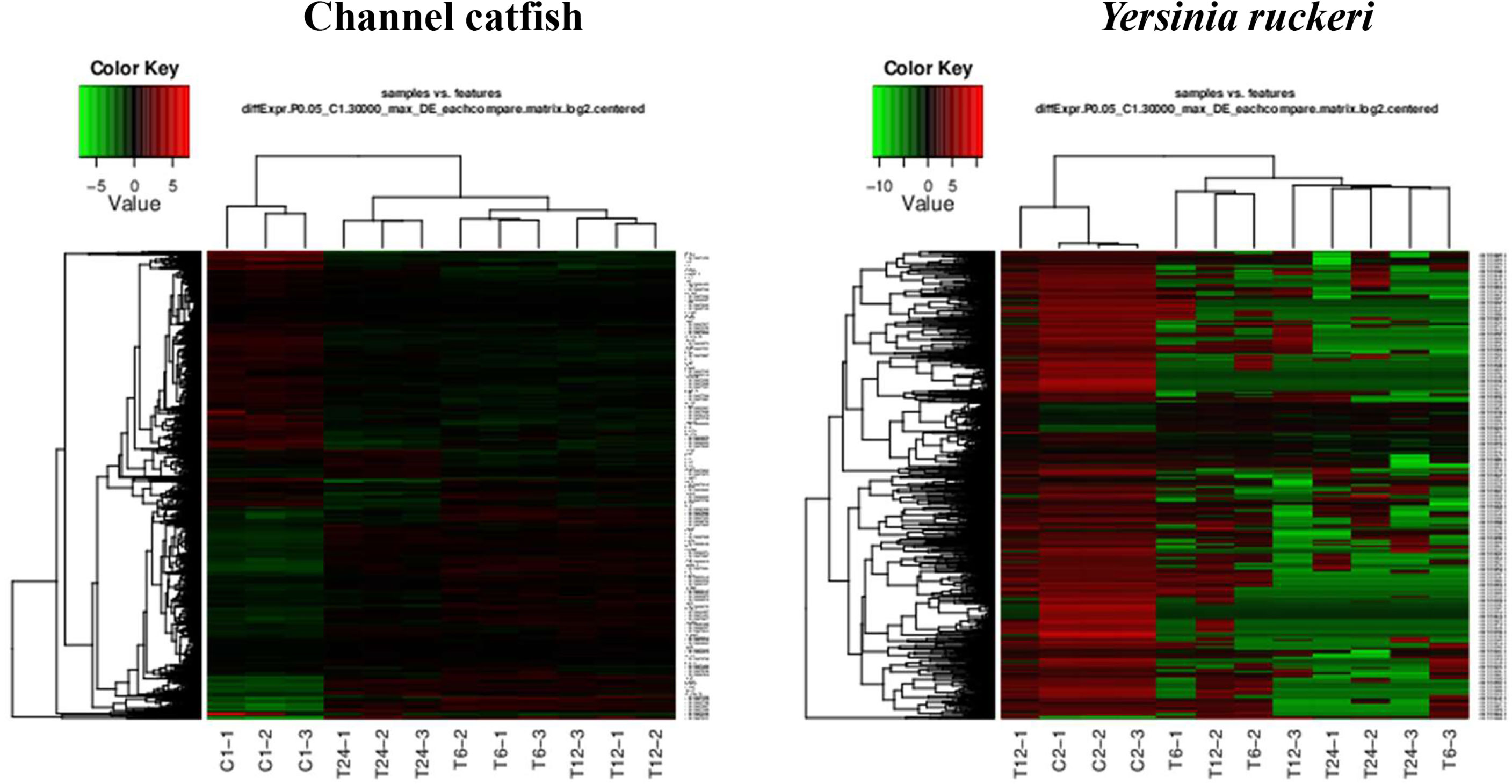

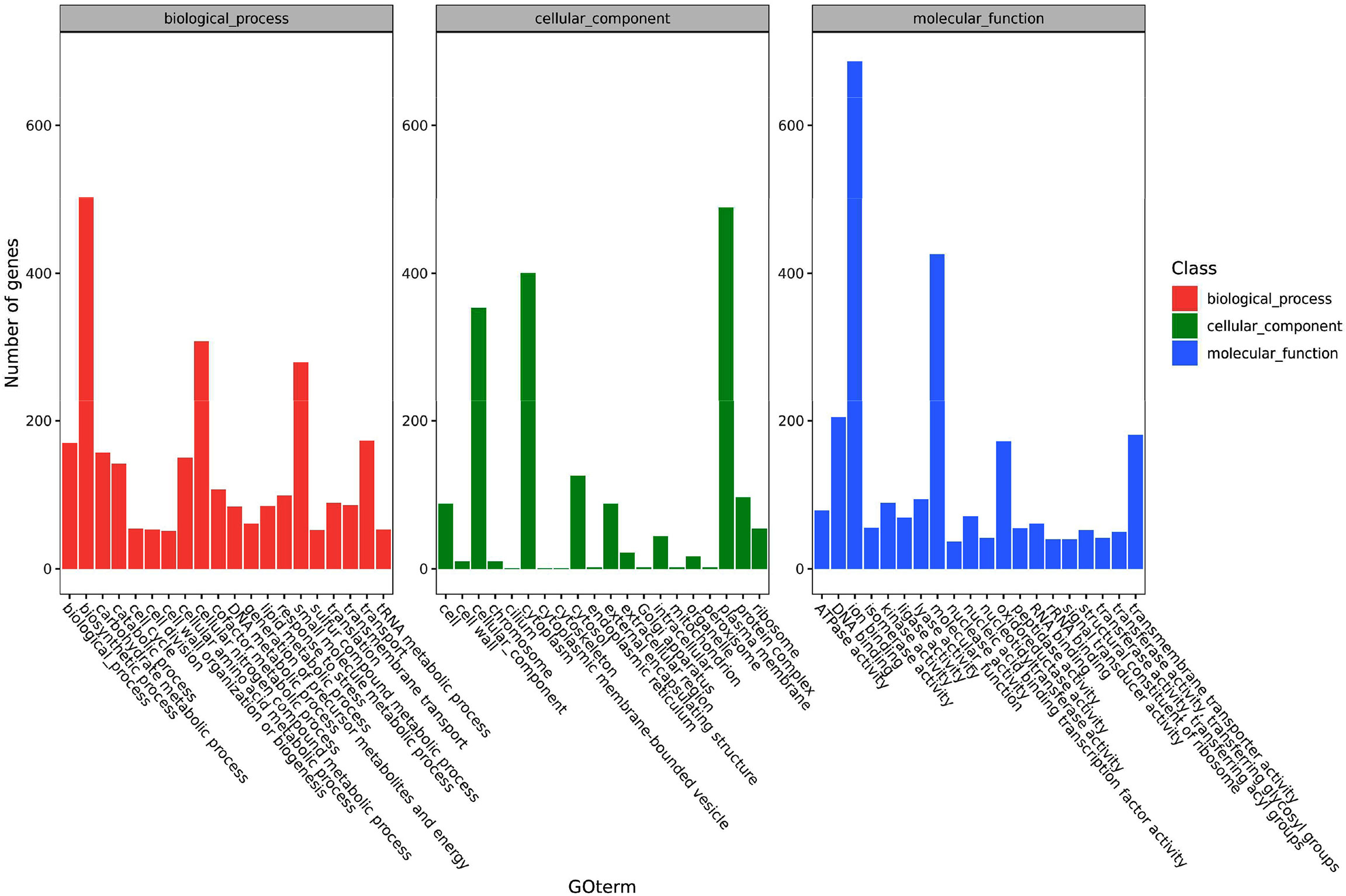

The functions of the DEGs in channel catfish are summarized in three groups, including cell components, molecular functions and biological processes. Secondary classifications of the top 20 GO terms with the most annotations under each classification are shown in Figure 3. The main subclasses for the biological processes category (containing a total of 3990 genes), includes signal transmission (2942 genes), analytical structure development (2714 genes), analytical structure development (2646 genes) and immune system (1465 genes). The main subclasses for the cell components category included the cytoplast (3673 genes), cellular components (3663 genes), plasma membrane (2891 genes) and nucleus (2853 genes). The main subclasses for the molecular functions category included ion binding (3847 genes), signal transducer activity (650 genes), DNA binding (1245 genes) and enzyme binding (982 genes) (Figure 3). Dividing the significantly upregulated and down-regulated DEGs at each time point and then performing GO analysis helps to dynamically compare the expression changes of the transcriptome at different time points. At 6 hpi, the up-regulated genes were significantly enriched in terms of the cell, cell parts, intracellular parts, binding, biological regulation and metabolic process categories. At 12 hpi, the up-regulated genes were significantly enriched in terms of intracellular parts, intracellular, binding, organelles, intracellular organelles, biological regulation and metabolic processes, signal transduction and regulation of cellular process. The up-regulated and down-regulated genes at 24 hpi were both significantly enriched in the cell, cell parts, cellular processes, organelles, metabolic processes, response to stimuli, biological regulation and other GO term categories.

Figure 3 A histogram of the enriched subcategories after GO annotation of DEGs in channel catfish infected by bacteria. The GO terms (X-axis) were grouped into 3 main ontologies, including biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC) and molecular functions (MF). The Y-axis indicates the number of DEGs.

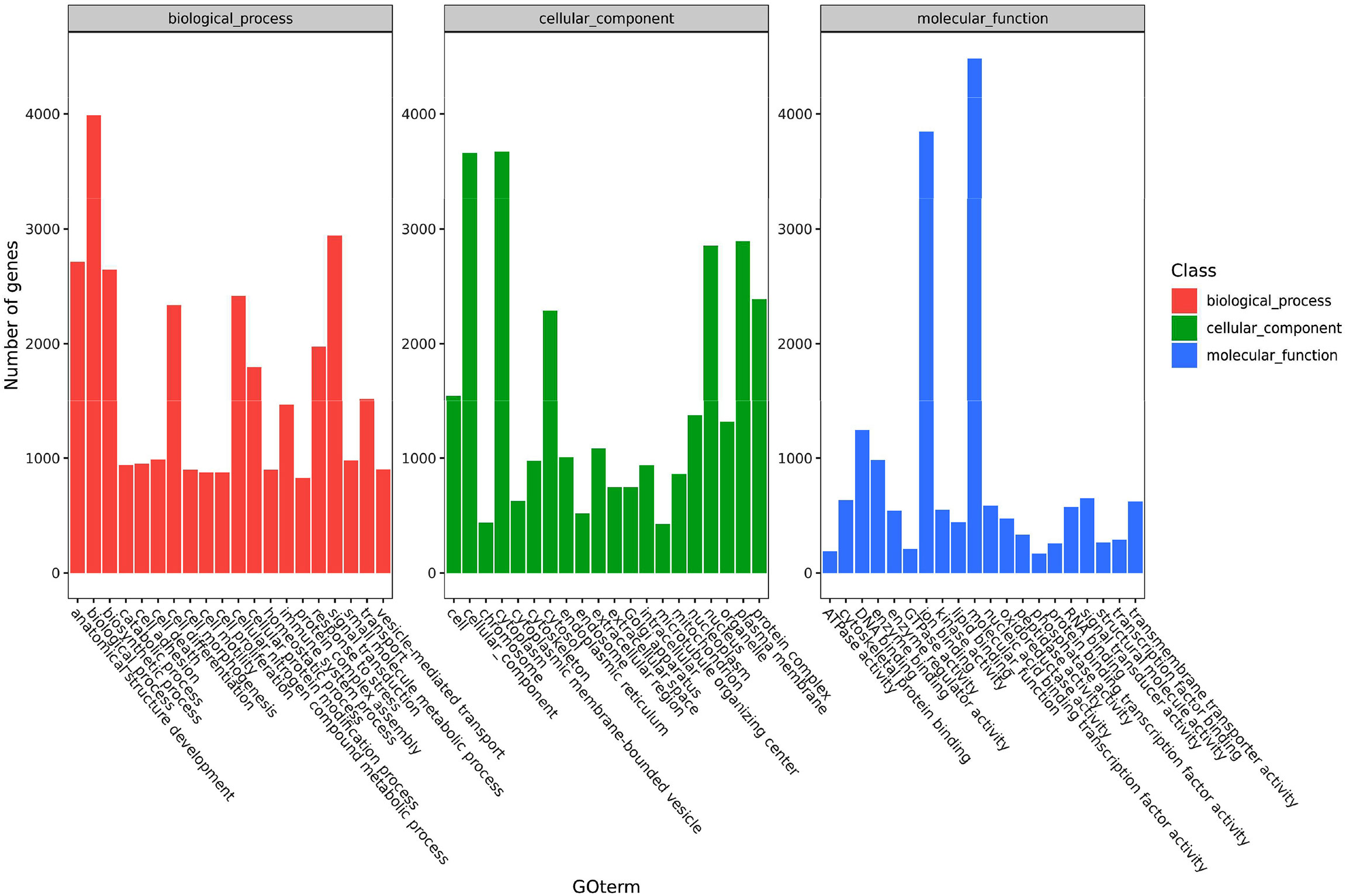

The functions of the pathogen’s DEGs are summarized in three categories including cell components, molecular functions and biological processes. Secondary classifications of the top 20 GO terms were selected from the most annotated under each classification and are shown in Figure 4. The main subclasses of the biological processes included biosynthetic processes (503 genes), cellular nitrogen compound metabolic processes (308 genes), small molecular metabolic processes (280 genes) and transport (173 genes). The main subclasses of cell components were cellular components (353 genes), cytosol (126 genes), plasma membrane (489 genes) and the cytoplast (400 genes). The main subclasses of molecular functions were ion binding (687 genes), transmembrane transporter activity (181 genes), DNA binding (205 genes) and oxidoreductase activity (181 genes) (Figure 4). At 6 hpi, the up-regulated genes were significantly enriched in terms of the cell, cell parts, cellular processes and metabolic processes categories. At 12 hpi, up-regulated genes were significantly enriched in terms of the cell, cell parts, binding, cellular process and metabolic processes categories. The up-regulated and down-regulated genes at 24 hpi were both significantly enriched in GO terms such as the cell, cell parts, cellular processes and primary metallic processes.

Figure 4 A histogram of the enriched subcategories after gene ontology (GO) annotation of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Y. ruckeri at different time points. The GO terms (X-axis) were grouped into 3 main ontologies: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). The Y-axis indicates the number of DEGs.

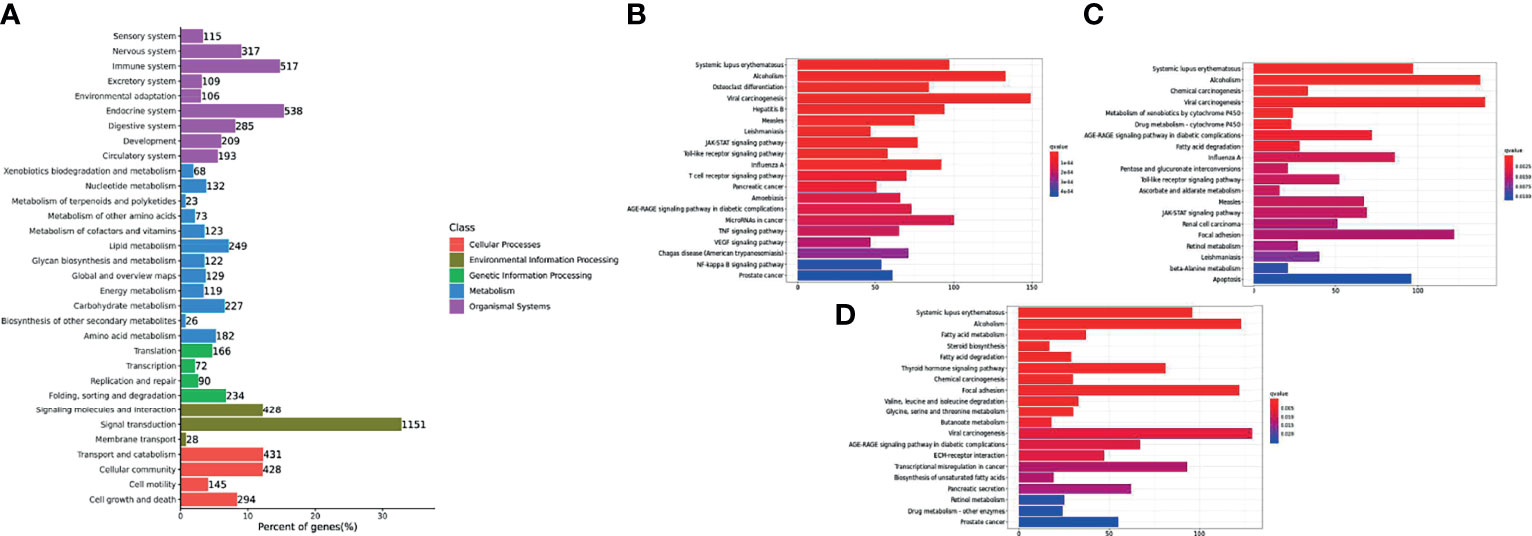

DEGs were mapped to the KEGG database to further study biological functions and important pathways. The KEGG pathway database was mainly divided into five categories, including metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes and biological systems. Trunk kidney DEGs of channel catfish were placed in 33 functional classifications, while Y. ruckeri DEGs were placed in 26 functional classifications (Figures 5A and 6A). Some genes exist in multiple pathways and some were limited to one pathway. The DEGs found in the trunk kidneys of channel catfish were significantly enriched in the functional classifications of signal transmission (1151 genes), followed by the endocrine system (538 genes), immune system (517 genes) and transport and catabolism (431 genes). The main biochemical metabolic and signal transduction pathways involved in DEGs can be determined through pathway significant enrichment. The first 20 most-enriched KEGG pathways of DEGs were noted at 6, 12 and 24 hpi. Systemic lupus erythematosus and alcoholism were significantly enriched at three time points, while the immune related JAK-STAT signaling pathway, viral carcinogenesis and toll-like receiver signaling pathways were significantly enriched at 6 and 12 hpi (Figures 5B–D).

Figure 5 Histogram of the top 20 most-enriched KEGG pathways of DEGs in channel catfish infected by bacteria. The Y-axis represents KEGG pathway categories. The X-axis represents the statistical significance of enrichment. (A) represents the classification of total KEGG, (B) represents the top 20 KEGG enriched metabolic pathways in the C1_T6 group, (C) represents the top 20 KEGG enriched metabolic pathways in the C1_T12 group and (D) represents the top 20 KEGG enriched metabolic pathways in the C1_T24 group.

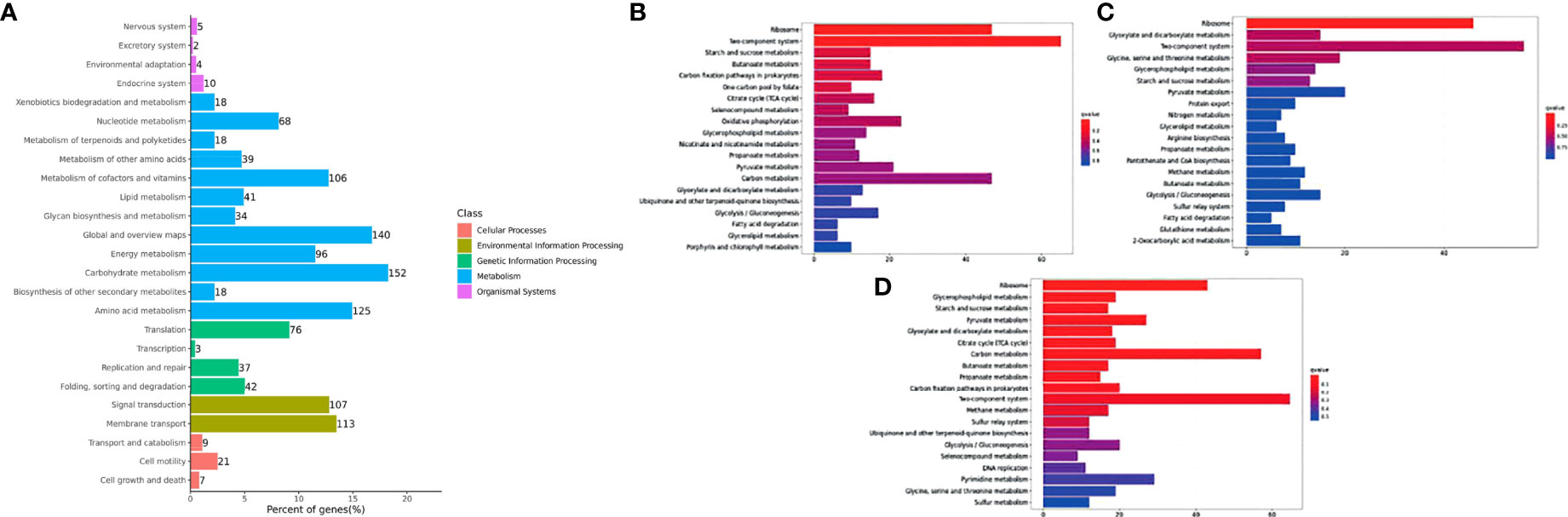

Figure 6 Histogram of the top 20 enriched KEGG pathways of DEGs in Y. ruckeri at different time points. The Y-axis represents the KEGG pathway categories. The X-axis represents statistical significance of the enrichment. (A) represents the classification of total KEGG, (B) represents the top 20 KEGG enriched metabolic pathways in the C2_T6 group, (C) represents the top 20 KEGG enriched metabolic pathways in the C2_T12 group and (D) represents the top 20 KEGG enriched metabolic pathways in the C2_T24 group.

DEGs observed in Y. ruckeri were significantly enriched for the functional classification of carbon metabolism (152 genes), followed by global and overview maps (140 genes), amino acid metabolism (125 genes) and membrane transport (113 genes). The top 20 most-enriched KEGG pathways of the DEGs were noted at 6, 12 and 24 hpi. There was significantly enrichment in the ribosome and two component systems, but this was only significant at 6 hpi. However, glycospholipid metabolism was also enriched at all points but was not found to be significant only at 6 hpi (Figures 6B–D).

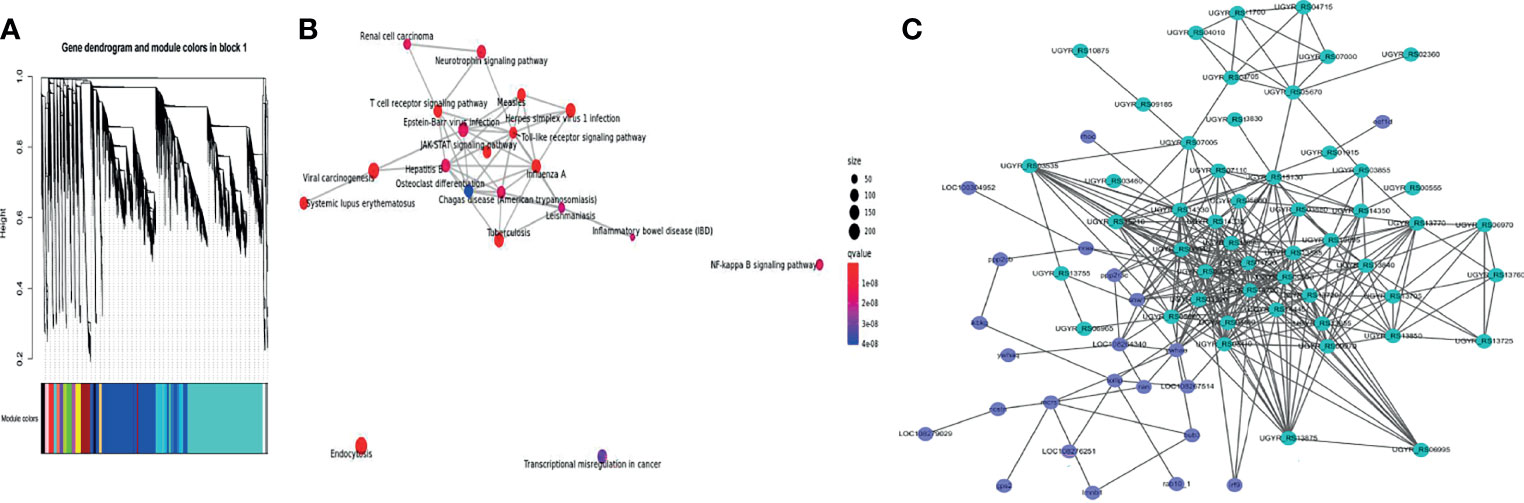

To determine the co-expression network between channel catfish and Y. ruckeri genes during infection, a hierarchical clustering tree was generated for the two organisms using WGCNA (Figure 7A). In the same module, the host and pathogen genes co-expressed at different time points were simultaneously identified. A total of 15 samples from 5 groups were used, including the channel catfish and Y. ruckeri control group and 3 experimental groups. Each experimental group contained three parallel controls. The gene coexpression network was constructed using all expressed genes. The constructed coexpression modules were divided into 19 different modules and named based on the color of their modules displayed on the hierarchical clustering tree.

Figure 7 WGCNA of transcriptional changes in channel catfish and Y. ruckeri. (A) A time-resolved transcriptome WGCNA cluster map for channel catfish and Y. ruckeri. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis for the turquoise module. The size of the circle represents the number of genes in the pathway. Color indicates significance and connected pathways represent genes within the pathway. (C) A correlation network of metabolic related DEGs in the turquoise module containing channel catfish and Y. ruckeri genes with an edge Pearson correlation coefficient greater than 0.98. Dot size represents degree values. Channel catfish genes are shown in purple and Y. ruckeri genes are shown in green.

To determine the importance of each module, KEGG enrichment analysis was performed. The turquoise module was enriched into many immune related pathways, as shown in Figure 7B. Therefore, the turquoise module was considered to be the most important module for the infection process.

To understand the interaction between the host and pathogen during infection, some key genes were selected for analysis. KME values(Pearson correlation coefficient)of genes > 0.98 and edge weights > 0.35 were selected for visualization. The interaction diagram is presented in Figure 7C, including 23 genes for the host and 50 genes for the pathogen.

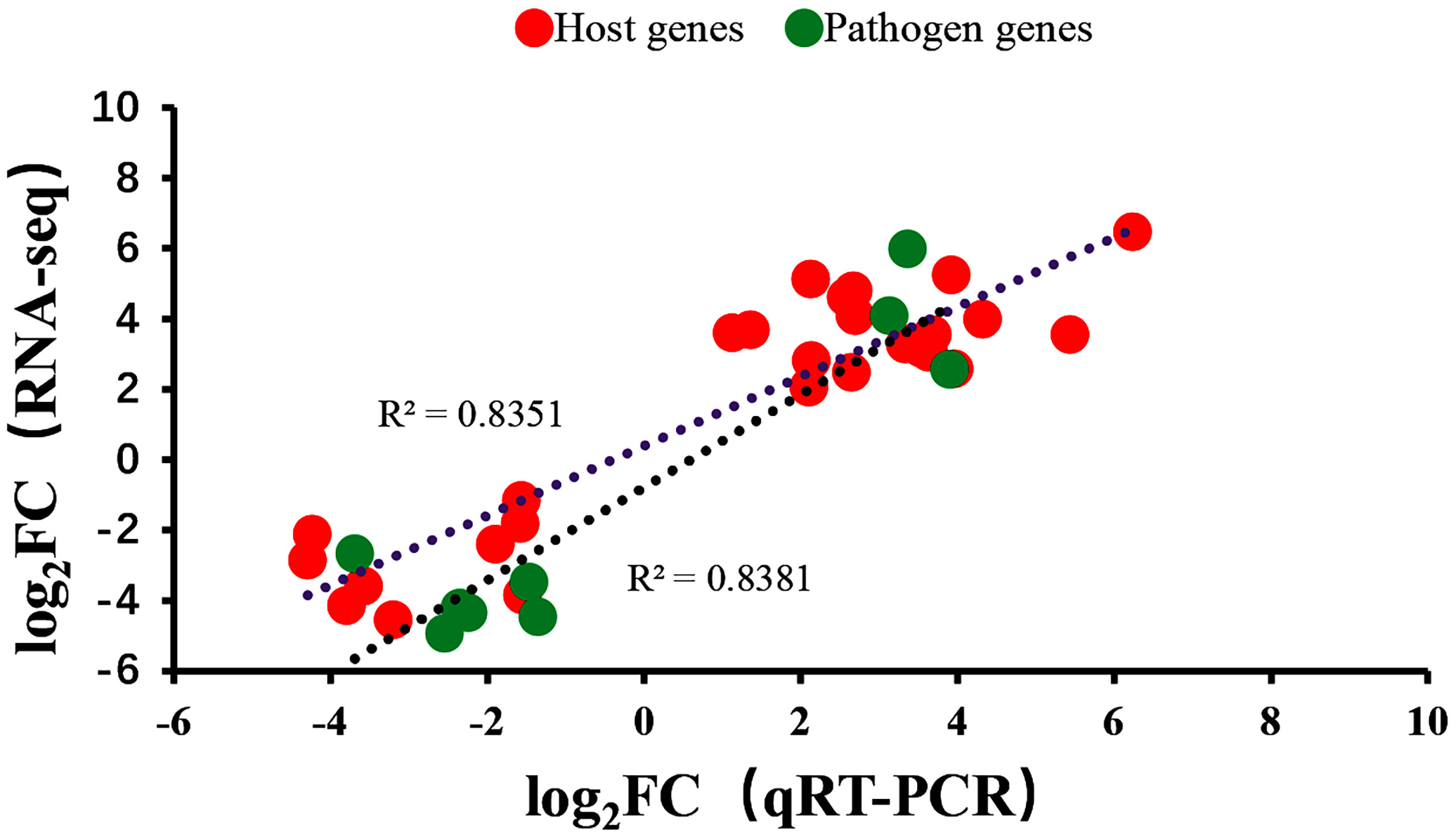

To verify the RNA-seq results, qRT-PCR was performed on the same RNA samples used for sequencing to detect 12 DEGs selected from differential expression data. The primer sequences for all genes are listed in Table 1. The qRT-PCR results of the 12 genes analyzed were consistent with results obtained from RNA -seq (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Comparison of gene expression levels for 12 genes using dual RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR. Negative values indicated that the gene expression in channel catfish was downregulated after infection by Y. ruckeri and positive values indicated an upregulation in gene expression after infection.

Y. ruckeri causes ERM in channel catfish and can lead to rapid death of this aquatic species ultimately resulting in heavy economic burdens. Both antibacterial treatment and vaccine prevention are used to control disease caused by Y. ruckeri (4, 6, 50, 51). Generally, vaccination is the most effective means of disease prevention in aquaculture. However, this method is very stressful for fish and labor-intensive for farmers (6). Traditionally, the infection rate from bacterial pathogens in aquaculture mainly depended on the use of antibiotics and antibacterial compounds (4). However, due to the high usage of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance and the safety problems related to antibiotic residues are an issue. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the mechanisms behind Y. ruckeri invasion of its host and its interaction with a host to provide a theoretical basis for finding gene targets to block bacterial invasion, reduce toxicity and strengthen host immune surveillance.

The interaction between the host and pathogen during infection is complex. During the different stages of infection, transcriptome changes occur in both the host and the pathogen. Not only is trunk kidney an important immune organ, it is also an important excretory organ in fish. At the same time, the trunk kidney is also the main organ infected in Y. ruckeri (6). Selecting the trunk kidney as the tissue analyzed during dual RNA-seq sequencing not only reflects the interaction between the host and pathogen, but also detects possible damage to the trunk kidney of channel catfish caused by Y. ruckeri, to provide basis for formulating prevention and control measures.

In this study, we investigated transcriptome changes in the trunk kidney and pathogen at different time points after channel catfish inoculation with Y. ruckeri. The number of DEGs in the trunk kidney and Y. ruckeri changed at the three different time points, but the overall change in the host was small at three time points, where 9000 genes with significant differences were enriched. However, at the 6 hpi point, genes related to innate immunity were enriched, including IL-20-like and IL-1β. There was a significantly higher number of down-regulated genes compared to upregulated genes in the pathogen, and this difference was most obvious at 24 hpi. However, OMPF genes, which are important bacterial antigens, were significantly enriched at all three time points (50). These results indicate that there is a strong immune response between the host and pathogen when Y. ruckeri infects channel catfish.

Host innate immunity uses a variety of recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors, to recognize bacteria (52–54). Transcriptomic analysis of Oreochromis niloticus during Streptococcus agalactiae infection showed that toll-like receptor-mediated pathways contribute to immune responses and protect the host against pathogens (55). The expression levels of many genes in “toll-like receptor signaling pathway” were significantly upregulated in large yellow croakers infected with pseudomonas mutants at 4 dpi (56). The results of this study showed that the expression levels of 58 differential genes in toll-like receptor signaling pathways were significantly upregulated at the onset of infection (6 hpi). Cytokines are key modulators of the host defense in innate immunity and adaptive inflammation (57). Cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, NF-Kappa B signaling pathways, important innate immune pathways such as the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, and the TNF signaling pathway were significantly enriched at 6-24 hpi, consistent with previous studies (58–61). When these pathways are significantly enriched, the fish produces an acute inflammatory response to protect itself and enhance its tissue repair and defense during infection. These results showed that the immune response of channel catfish increases during the progression of Y. ruckeri infection.

Metabolic regulation of the host is also very important in the process of infection. The immune system needs energy to resist pathogens and maintain tissue homeostasis (62, 63). To overcome stress caused by the pathogen, the infected fish expends a large amount of energy (64). Amino acid metabolism is important for host energy consumption, detoxification, protein synthesis and safe operation of innate immune responses (65). Through KEGG enrichment, all pathways enriched at 6-12 hpi are related to immunity. At 24 hpi, many metabolic pathways are enriched, such as fatty acid, glycine, serine and threonine and butanoate metabolism pathways. It is speculated that when channel catfish are infected by Y. ruckeri, the acute immune response begins immediately. As the first line barrier, innate immune-related molecules and pathways are rapidly expressed. With more serious and progressed infection, channel catfish require fatty acid and amino acid metabolism to provide energy and proteins. Changes in tryptophan metabolism were also observed in many fish such as zebrafish, large yellow cordon, Atlantic salmon and abalone, indicating that tryptophan and its metabolites may play an important role in the immune system of aquatic animals (66–68).

For pathogens that invade the host, flagella play a key role, including colonizing and invading the host, reaching the optimal host site, maintaining the infection site and spreading after infection (69–71). To date, flagella have been implicated in the virulence of many aquatic pathogenic bacteria, such as Y. ruckeri (46, 72), Edwardsiella tarda (73), and Vibrio anguillarum (74). In this study, the flagellar gene fliC was significantly upregulated from 6-24 hpi, indicating that it was involved in the infection process of Y. ruckeri (72). KEGG was significantly enriched in the two-component system of Y. ruckeri at 6-12 hpi. This indicates that the bacteria adapt to the state of the fish by sensing environmental changes, regulating the expression of survival and virulence factors and maintaining their own survival (23). At 24 hpi, the gene expression levels of the bacterial two-component system decreased, indicating that the pathogen adapted to the fish environment and the host developed symptoms and began to due. At the same time, the pathogen was significantly enriched in the sucrose of bacterial secretion system, ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis, and starch and sucrose metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, one carbon pool by folate and other signaling pathways (75). These results indicated that the pathogen used its secretory system to escape and consume energy during the invasion process.

WGCNA was divided into 19 modules and the results showed that the relationship between the host and pathogen is very complex. The turquoise module was considered to be the most important in the infection process, showing the dynamic process of the life-and-death struggle between the host and the pathogen, reflecting how the innate immunity of the host copes with pathogen invasion and how the pathogen achieves immune escape. In the interaction network diagram, 50 pathogenic genes were found to be associated with the host immune response. The pathogen mainly relied on SpaR and SpaP for immune escape through the type II secretion system, which has not been identified in previous studies (76, 77). The pathogen HlyB was up-regulated in the infection, indicating that the pathogen rely on hemolysin to cause harm in the host trunk kidney. The uvry regulatory gene and flagella transcriptional regulator flhd were also significantly down-regulated, consistent with previous studies that uvry gene mutations did not affect the survival rate of Y. ruckeri in fish (23), Therefore, the pathogen mainly depended on fliC flagellin for attachment and virulence. With progression of the infection, the expression of the multidrug resistant proteins mdtc and MDTA were seriously inhibited, suggesting that the drug resistance of the strains decreased.

Here, we successfully used tissue dual RNA-seq to simultaneously analyze the dynamics of gene expression changes in both the host and pathogen and obtained high-resolution transcriptome data. For the host, innate immunity is an important means to resist bacterial invasion and bacterial flagella is an important tool for infection used by the pathogen. WGCNA reveals the strong interaction and relationship between the host and pathogen genomes throughout the infection process, which is most closely related to metabolic activities. This study has important theoretical significance for understanding the pathogenesis of channel catfish ERM.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI SRA BioProject, accession no: PRJNA760961.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and use Committee of Changjiang Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences.

YY and YC conceived and designed the study. YY performed most of the experiments. XA, XZ, HZ, and YS provided bioinformatics assistance and support. YC and YY wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by Yancheng fishery high quality development project [No.YCSCYJ2021026], Major innovation projects in Hubei Province [No. 2019ABA077] and the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS [No.2017HY-ZD0505].

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We sincerely thank the reviewers for their constructive comments which lead to an improved manuscript.

1. Troell M, Naylor RL, Metian M, Beveridge M, Tyedmers PH, Folke C, et al. Does Aquaculture Add Resilience to the Global Food System? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2014) 111(37):13257–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404067111

2. Bostock J, McAndrew B, Richards R, Jauncey K, Telfer T, Lorenzen K, et al. Aquaculture: Global Status and Trends, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser B Biol Sci (2010) 365(1554):2897–912. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0170

4. Wang E, Wang J, Long B, Wang K, He Y, Yang Q, et al. Molecular Cloning, Expression and the Adjuvant Effects of Interleukin-8 of Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus) Against Streptococcus Iniae. Sci Rep (2016) 6:29310. doi: 10.1038/srep29310

5. Abdelhamed H, Ibrahim I, Nho SW, Banes MM, Wills RW, Karsi A, et al. Evaluation of Three Recombinant Outer Membrane Proteins, OmpA1, Tdr, and TbpA, as Potential Vaccine Antigens Against Virulent Aeromonas Hydrophila Infection in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus). Fish Shellfish Immunol (2017) 66:480–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.05.043

6. Liu T, Wang KY, Wang J, Chen DF, Huang XL, Ouyang P, et al. Genome Sequence of the Fish Pathogen Yersinia Ruckeri SC09 Provides Insights Into Niche Adaptation and Pathogenic Mechanism. Int J Mol Sci (2016) 17(4):557. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040557

7. McGinnis A, Gaunt P, Santucci T, Simmons R, Endris R. In Vitro Evaluation of the Susceptibility of Edwardsiella Ictaluri, Etiological Agent of Enteric Septicemia in Channel Catfish, Ictalurus Punctatus (Rafinesque), to Florfenicol. J Vet Diagn Invest Off Publ Am Assoc Vet Lab Diagnosticians Inc (2003) 15(6):576–9. doi: 10.1177/104063870301500612

8. Jiang J, Zheng Z, Wang K, Wang J, He Y, Wang E, et al. Adjuvant Immune Enhancement of Subunit Vaccine Encoding pSCPI of Streptococcus Iniae in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus). Int J Mol Sci (2015) 16(12):28001–13. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226082

9. Li M, Wang QL, Lu Y, Chen SL, Li Q, Sha ZX. Expression Profiles of NODs in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus) After Infection With Edwardsiella Tarda, Aeromonas Hydrophila, Streptococcus Iniae and Channel Catfish Hemorrhage Reovirus. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2012) 33(4):1033–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.06.033

10. Li M, Liu Y, Wang QL, Chen SL, Sha ZX. BIRC7 Gene in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus): Identification and Expression Analysis in Response to Edwardsiella Tarda, Streptococcus Iniae and Channel Catfish Hemorrhage Reovirus. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2012) 33(1):146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.03.026

11. Kumar G, Menanteau-Ledouble S, Saleh M, El-Matbouli M. Yersinia Ruckeri, the Causative Agent of Enteric Redmouth Disease in Fish. Vet Res (2015) 46(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0238-4

12. Saleh M, Soliman H, El-Matbouli M. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification as an Emerging Technology for Detection of Yersinia Ruckeri the Causative Agent of Enteric Red Mouth Disease in Fish. BMC Vet Res (2008) 4:31. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-4-31

13. Zuo S, Karami AM, Ødegård J, Mathiessen H, Marana MH, Jaafar RM, et al. Immune Gene Expression and Genome-Wide Association Analysis in Rainbow Trout With Different Resistance to Yersinia Ruckeri Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2020) 106:441–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.07.023

14. Li S, Zhang Y, Cao Y, Wang D, Liu H, Lu T. Trancriptome Profiles of Amur Sturgeon Spleen in Response to Yersinia Ruckeri Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2017) 70:451–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.09.033

15. Adel M, Yeganeh S, Dadar M, Sakai M, Dawood MAO. Effects of Dietary Spirulina Platensis on Growth Performance, Humoral and Mucosal Immune Responses and Disease Resistance in Juvenile Great Sturgeon (Huso Huso Linnaeus, 1754). Fish Shellfish Immunol (2016) 56:436–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.08.003

16. Wang KY, Liu T, Wang J, Chen DF, Wu XJ, Jiang J, et al. Complete Genome Sequence of the Fish Pathogen Yersinia Ruckeri Strain SC09, Isolated From Diseased Ictalurus Punctatus in China. Genome Announcements (2015) 3(1):e01327–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01327-14

17. Ohtani M, Villumsen KR, Koppang EO, Raida MK. Global 3D Imaging of Yersinia Ruckeri Bacterin Uptake in Rainbow Trout Fry. PloS One (2015) 10(2):e0117263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117263

18. Navais R, Méndez J, Pérez-Pascual D, Cascales D, Guijarro JA. The yrpAB Operon of Yersinia Ruckeri Encoding Two Putative U32 Peptidases Is Involved in Virulence and Induced Under Microaerobic Conditions. Virulence (2014) 5(5):619–24. doi: 10.4161/viru.29363

19. Qin Z, Baker AT, Raab A, Huang S, Wang T, Yu Y, et al. The Fish Pathogen Yersinia Ruckeri Produces Holomycin and Uses an RNA Methyltransferase for Self-Resistance. J Biol Chem (2013) 288(21):14688–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.448415

20. Méndez J, Reimundo P, Pérez-Pascual D, Navais R, Gómez E, Guijarro JA. A Novel cdsAB Operon is Involved in the Uptake of L-Cysteine and Participates in the Pathogenesis of Yersinia Ruckeri. J Bacteriol (2011) 193(4):944–51. doi: 10.1128/JB.01058-10

21. Dahiya I, Stevenson RM. Yersinia Ruckeri Genes That Attenuate Survival in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) Are Identified Using Signature-Tagged Mutants. Vet Microbiol (2010) 144(3-4):399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.003

22. Dahiya I, Stevenson RM. The ZnuABC Operon is Important for Yersinia Ruckeri Infections of Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus Mykiss (Walbaum). J fish Dis (2010) 33(4):331–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01125.x

23. Dahiya I, Stevenson RM. The UvrY Response Regulator of the BarA-UvrY Two-Component System Contributes to Yersinia Ruckeri Infection of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss). Arch Microbiol (2010) 192(7):541–7. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0582-8

24. Fernández L, Méndez J, Guijarro JA. Molecular Virulence Mechanisms of the Fish Pathogen Yersinia Ruckeri. Vet Microbiol (2007) 125(1-2):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.06.013

25. Fernández L, Márquez I, Guijarro JA. Identification of Specific In Vivo-Induced (Ivi) Genes in Yersinia Ruckeri and Analysis of Ruckerbactin, a Catecholate Siderophore Iron Acquisition System. Appl Environ Microbiol (2004) 70(9):5199–207. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5199-5207.2004

26. Guijarro JA, García-Torrico AI, Cascales D, Méndez J. The Infection Process of Yersinia Ruckeri: Reviewing the Pieces of the Jigsaw Puzzle. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2018) 8:218. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00218

27. Liu T, Li L, Wei W, Wang K, Yang Q, Wang E. Yersinia Ruckeri Strain SC09 Disrupts Proinflammatory Activation via Toll/IL-1 Receptor-Containing Protein STIR-3. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2020) 99:424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.02.035

28. Liu T, Yang Q, Wei W, Wang K, Wang E. Toll/IL-1 Receptor-Containing Proteins STIR-1, STIR-2 and STIR-3 Synergistically Assist Yersinia Ruckeri SC09 Immune Escape. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2020) 103:357–65. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.05.007

29. Liu T, Wang E, Wei W, Wang K, Yang Q, Ai X. TcpA, a Novel Yersinia Ruckeri TIR-Containing Virulent Protein Mediates Immune Evasion by Targeting MyD88 Adaptors. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2019) 94:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.08.069

30. Zhang B, Luo G, Zhao L, Huang L, Qin Y, Su Y, et al. Integration of RNAi and RNA-Seq Uncovers the Immune Responses of Epinephelus Coioides to L321_RS19110 Gene of Pseudomonas Plecoglossicida. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2018) 81:121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.06.051

31. Luo G, Sun Y, Huang L, Su Y, Zhao L, Qin Y, et al. Time-Resolved Dual RNA-Seq of Tissue Uncovers Pseudomonas Plecoglossicida Key Virulence Genes in Host-Pathogen Interaction With Epinephelus Coioides. Environ Microbiol (2020) 22(2):677–93. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14884

32. Jenner RG, Young RA. Insights Into Host Responses Against Pathogens From Transcriptional Profiling, Nature Reviews. Microbiology (2005) 3(4):281–94. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1126

33. Sorek R, Cossart P. Prokaryotic Transcriptomics: A New View on Regulation, Physiology and Pathogenicity, Nature Reviews. Genetics (2010) 11(1):9–16. doi: 10.1038/nrg2695

34. Yang Y, Adeola AC, Xie HB, Zhang YP. Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Selection of Genes for Puberty in Bama Xiang Pigs. Zoo Res (2018) 39(6):424–30. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2018.068

35. Aprianto R, Slager J, Holsappel S, Veening JW. Time-Resolved Dual RNA-Seq Reveals Extensive Rewiring of Lung Epithelial and Pneumococcal Transcriptomes During Early Infection. Genome Biol (2016) 17(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1054-5

36. Liu Z, Liu S, Yao J, Bao L, Zhang J, Li Y, et al. The Channel Catfish Genome Sequence Provides Insights Into the Evolution of Scale Formation in Teleosts. Nat Commun (2016) 7:11757. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11757

37. He L, Jiang H, Cao D, Liu L, Hu S, Wang Q. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of the Accessory Sex Gland and Testis From the Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir Sinensis). PloS One (2013) 8(1):e53915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053915

38. Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, et al. Differential Gene and Transcript Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments With TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc (2012) 7(3):562–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016

39. Anders S, Huber W. Differential Expression Analysis for Sequence Count Data. Genome Biol (2010) 11(10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106

40. Liu B, Jiang G, Zhang Y, Li J, Li X, Yue J, et al. Analysis of Transcriptome Differences Between Resistant and Susceptible Strains of the Citrus Red Mite Panonychus Citri (Acari: Tetranychidae). PloS One (2011) 6(12):e28516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028516

41. Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinf (2008) 9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559

42. Grote A, Voronin D, Ding T, Twaddle A, Unnasch TR, Lustigman S, et al. Defining Brugia Malayi and Wolbachia Symbiosis by Stage-Specific Dual RNA-Seq. PloS Neg Trop Dis (2017) 11(3):e0005357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005357

43. Yang Y, Fu Q, Wang X, Liu Y, Zeng Q, Li Y, et al. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of the Swimbladder Reveals Expression Signatures in Response to Low Oxygen Stress in Channel Catfish. Ictalurus Punctatus Physiol Genomics (2018) 50(8):636–47. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00125.2017

44. Wang J, Xiong G, Bai C, Liao TJA. Anesthetic Efficacy of Two Plant Phenolics and the Physiological Response of Juvenile Ictalurus Punctatus to Simulated Transport. Aquaculture (2021) 538: (12):736566. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736566

45. Jiang H, Wang M, Fu L, Zhong L, Liu G, Zheng Y, et al. Liver Transcriptome Analysis and Cortisol Immune-Response Modulation in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus). Fish Shellfish Immunol (2020) 101:19–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.03.024

46. Jozwick AKS, LaPatra SE, Graf J, Welch TJ. Flagellar Regulation Mediated by the Rcs Pathway Is Required for Virulence in the Fish Pathogen Yersinia Ruckeri. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2019) 91:306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.05.036

47. Mendez J, Cascales D, Garcia-Torrico AI, Guijarro JA. Temperature-Dependent Gene Expression in Yersinia Ruckeri: Tracking Specific Genes by Bioluminescence During in Vivo Colonization. Front Microbiol (2018) 9:1098. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01098

48. Jozwick AK, Graf J, Welch TJ. The Flagellar Master Operon flhDC is a Pleiotropic Regulator Involved in Motility and Virulence of the Fish Pathogen Yersinia Ruckeri. J Appl Microbiol (2017) 122(3):578–88. doi: 10.1111/jam.13374

49. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego Calif.) (2001) 25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

50. Wang E, Qin Z, Yu Z, Ai X, Wang K, Yang Q, et al. Molecular Characterization, Phylogenetic, Expression, and Protective Immunity Analysis of OmpF, a Promising Candidate Immunogen Against Yersinia Ruckeri Infection in Channel Catfish. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2003. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02003

51. Wang E, Yuan Z, Wang K, Gao D, Liu Z, Liles R. Consumption of Florfenicol-Medicated Feed Alters the Composition of the Channel Catfish Intestinal Microbiota Including Enriching the Relative Abundance of Opportunistic Pathogens. Aquaculture (2019) 501:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.11.019

52. Kawai T, Akira S. The Role of Pattern-Recognition Receptors in Innate Immunity: Update on Toll-Like Receptors. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(5):373–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863

53. Palti Y. Toll-Like Receptors in Bony Fish: From Genomics to Function. Dev Comp Immunol (2011) 35(12):1263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.03.006

54. Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-Like Receptors. Curr Protoc Immunol (2015) 109:14.12.1–14.12.10. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1412s109

55. Ken CF, Chen CN, Ting CH, Pan CY, Chen JY. Transcriptome Analysis of Hybrid Tilapia (Oreochromis Spp.) With Streptococcus Agalactiae Infection Identifies Toll-Like Receptor Pathway-Mediated Induction of NADPH Oxidase Complex and Piscidins as Primary Immune-Related Responses. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2017) 70:106–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.08.041

56. Tang Y, Xin G, Zhao LM, Huang LX, Qin YX, Su YQ, et al. Novel Insights Into Host-Pathogen Interactions of Large Yellow Croakers ( Larimichthys Crocea) and Pathogenic Bacterium Pseudomonas Plecoglossicida Using Time-Resolved Dual RNA-Seq of Infected Spleens. Zoological Res (2020) 41(3):314–27. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.035

57. Akdis M, Aab A, Altunbulakli C, Azkur K, Costa RA, Crameri R, et al. Interleukins (From IL-1 to IL-38), Interferons, Transforming Growth Factor β, and TNF-α: Receptors, Functions, and Roles in Diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 138(4):984–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.033

58. Wang D, Sun S, Li S, Lu T, Shi D. Transcriptome Profiling of Immune Response to Yersinia Ruckeri in Spleen of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss). BMC Genomics (2021) 22(1):292. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07611-4

59. Westermann AJ, Förstner KU, Amman F, Barquist L, Chao Y, Schulte LN, et al. Dual RNA-Seq Unveils Noncoding RNA Functions in Host-Pathogen Interactions. Nature (2016) 529(7587):496–501. doi: 10.1038/nature16547

60. Tang J, Xu L, Zeng Y, Gong F. Effect of Gut Microbiota on LPS-Induced Acute Lung Injury by Regulating the TLR4/NF-kB Signaling Pathway. Int Immunopharmacol (2021) 91:107272. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107272

61. Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-κb Signaling Pathways. Nat Immunol (2011) 12(8):695–708. doi: 10.1038/ni.2065

62. Nhan JD, Turner CD, Anderson SM, Yen CA, Dalton HM, Cheesman HK, et al. Redirection of SKN-1 Abates the Negative Metabolic Outcomes of a Perceived Pathogen Infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116(44):22322–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1909666116

63. Ganeshan K, Chawla A. Metabolic Regulation of Immune Responses. Annu Rev Immunol (2014) 32:609–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120236

64. Yin F, Gong H, Ke Q, Li A. Stress, Antioxidant Defence and Mucosal Immune Responses of the Large Yellow Croaker Pseudosciaena Crocea Challenged With Cryptocaryon Irritans. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2015) 47(1):344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.09.013

65. Lu J, Shi Y, Cai S, Feng J. Metabolic Responses of Haliotis Diversicolor to Vibrio Parahaemolyticus Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2017) 60:265–74. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.11.051

66. Mondanelli G, Iacono A, Allegrucci M, Puccetti P, Grohmann U. Immunoregulatory Interplay Between Arginine and Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1565. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01565

67. Ji C, Guo X, Ren J, Zu Y, Li W, Zhang Q. Transcriptomic Analysis of microRNAs-mRNAs Regulating Innate Immune Response of Zebrafish Larvae Against Vibrio Parahaemolyticus Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2019) 91:333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.05.050

68. Liu PF, Du Y, Meng L, Li X, Liu Y. Metabolic Profiling in Kidneys of Atlantic Salmon Infected With Aeromonas Salmonicida Based on (1)H NMR. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2016) 58:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.08.055

69. Chaban B, Hughes HV, Beeby M. The Flagellum in Bacterial Pathogens: For Motility and a Whole Lot More. Semin Cell Dev Biol (2015) 46:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.10.032

70. Gu H. Role of Flagella in the Pathogenesis of Helicobacter Pylori. Curr Microbiol (2017) 74(7):863–9. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1256-4

71. Meng J, Bai J, Chen J. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals the Role of RcsB in Suppressing Bacterial Chemotaxis, Flagellar Assembly and Infection in Yersinia Enterocolitica. Curr Genet (2020) 66(5):971–88. doi: 10.1007/s00294-020-01083-x

72. Jiang J, Zhao W, Xiong Q, Wang K, He Y, Wang J, et al. Immune Responses of Channel Catfish Following the Stimulation of Three Recombinant Flagellins of Yersinia Ruckeri In Vitro and In Vivo. Dev Comp Immunol (2017) 73:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.02.015

73. Morimoto N, Kondo M, Kono T, Sakai M, Hikima JI. Nonconservation of TLR5 Activation Site in Edwardsiella Tarda Flagellin Decreases Expression of Interleukin-1β and NF-κb Genes in Japanese Flounder, Paralichthys Olivaceus. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2019) 87:765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.02.024

74. Liu X, Wu H, Chang X, Tang Y, Liu Q, Zhang Y. Notable Mucosal Immune Responses Induced in the Intestine of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Bath-Vaccinated With a Live Attenuated Vibrio Anguillarum Vaccine. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2014) 40(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.06.030

75. Méndez J, Fernández L, Menéndez A, Reimundo P, Pérez-Pascual D, Navais R, et al. A Chromosomally Located traHIJKCLMN Operon Encoding a Putative Type IV Secretion System is Involved in the Virulence of Yersinia Ruckeri. Appl Environ Microbiol (2009) 75(4):937–45. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01377-08

76. Wrobel A, Ottoni C, Leo JC, Linke D. Pyr4 From a Norwegian Isolate of Yersinia Ruckeri Is a Putative Virulence Plasmid Encoding Both a Type IV Pilus and a Type IV Secretion System. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2018) 8:373. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00373

Keywords: channel catfish, Yersinia ruckeri, dual RNA-seq, host-pathogen interactions, immunity, virulence

Citation: Yang Y, Zhu X, Zhang H, Chen Y, Song Y and Ai X (2021) Dual RNA-Seq of Trunk Kidneys Extracted From Channel Catfish Infected With Yersinia ruckeri Reveals Novel Insights Into Host-Pathogen Interactions. Front. Immunol. 12:775708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.775708

Received: 14 September 2021; Accepted: 26 November 2021;

Published: 15 December 2021.

Edited by:

Eva-Stina Isabella Edholm, Arctic University of Norway, NorwayReviewed by:

Jing Xing, Ocean University of China, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Yang, Zhu, Zhang, Chen, Song and Ai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaohui Ai, YWl4aEB5ZmkuYWMuY24=; Yuhua Chen, NTEwMDI2NDM3QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.