- 1Phytochemistry Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Men’s Health and Reproductive Health Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 3Department of Pharmacognosy, College of Pharmacy, Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraq

- 4Neurophysiology Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 5Dietary Supplements and Probiotic Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

- 6Department of Medical Biotechnology, School of Medicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

- 7Skull Base Research Center, Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Behehsti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 8Institute of Human Genetics, Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany

- 9Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Shahid Behehsti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

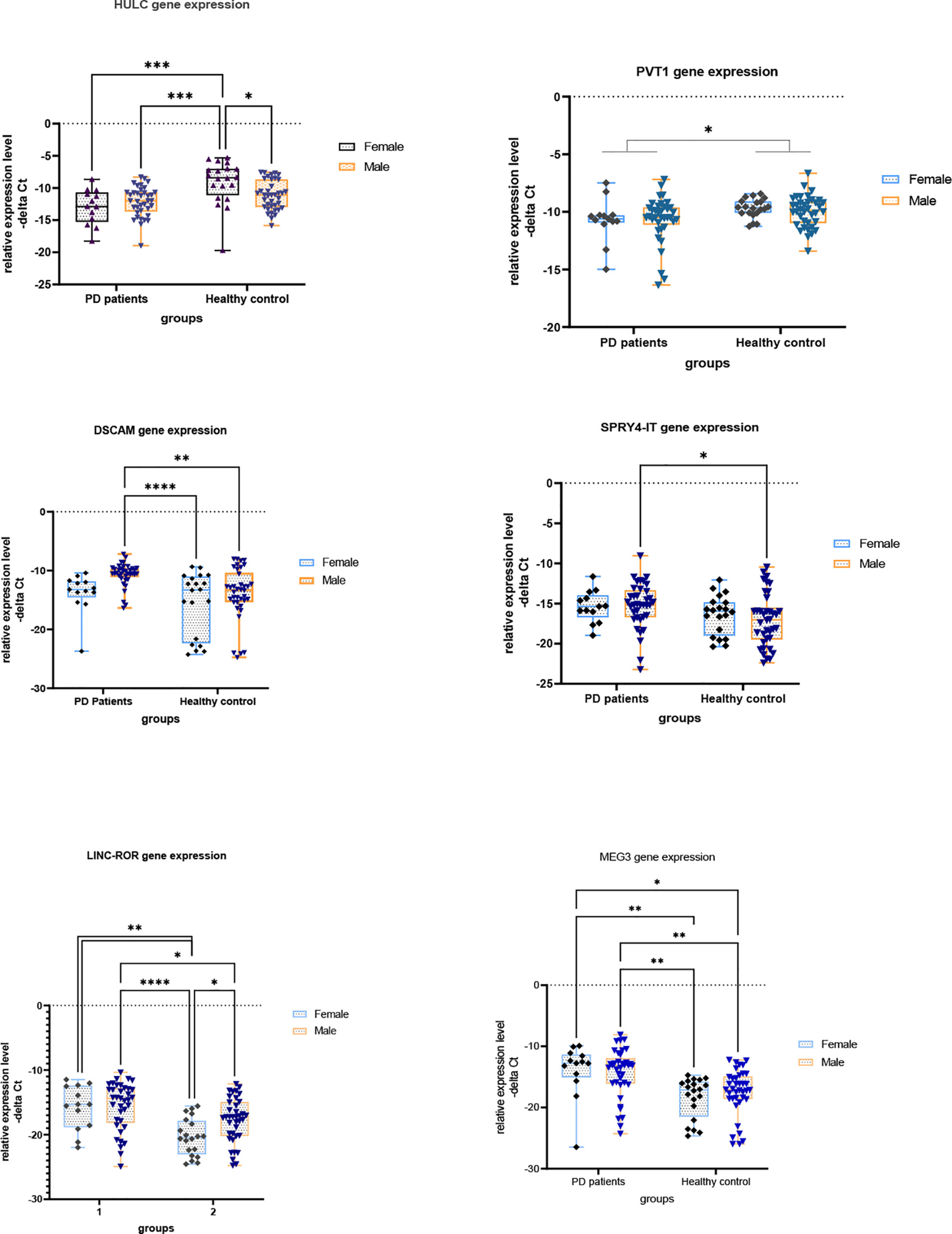

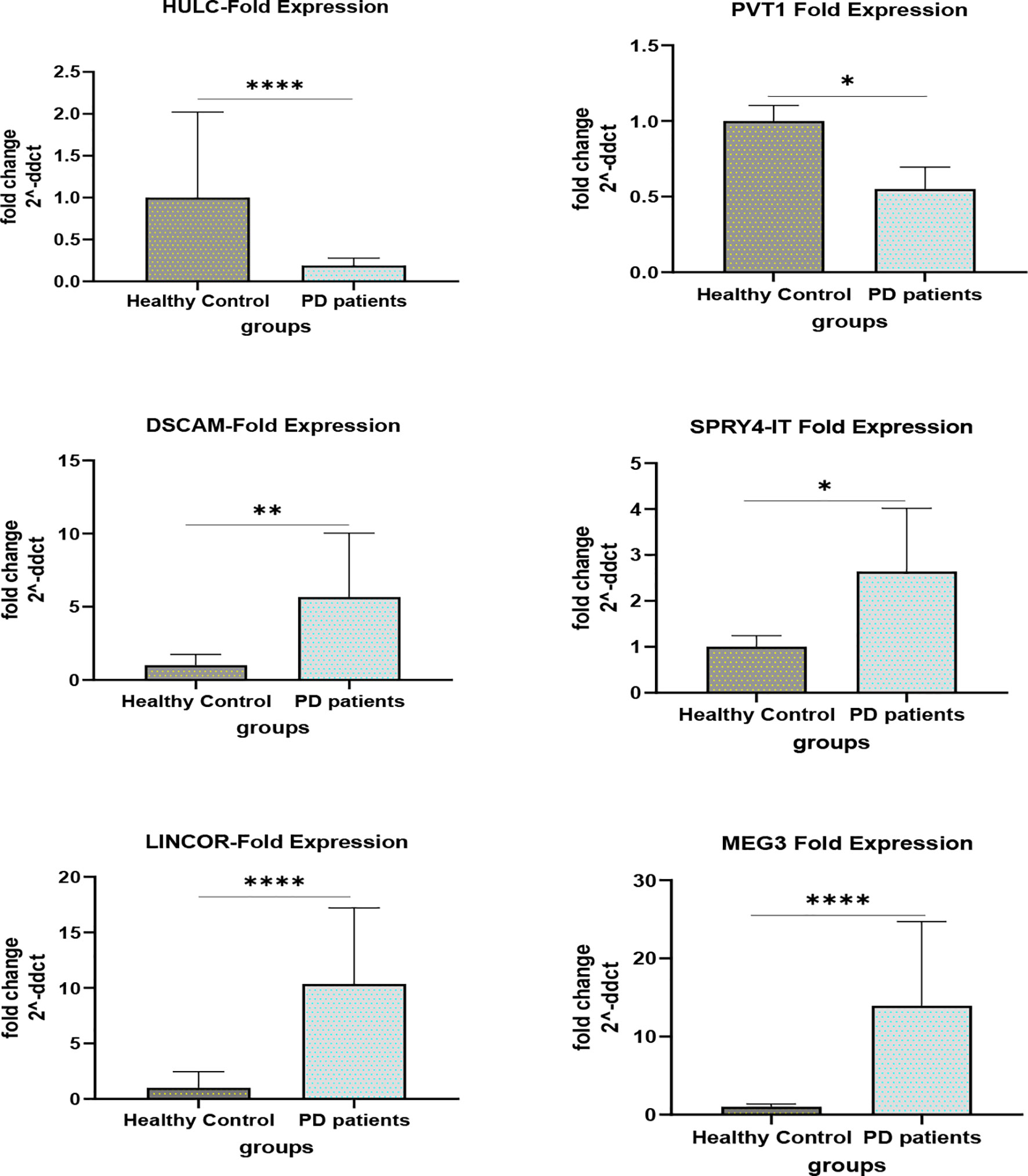

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been recently reported to be involved in the pathoetiology of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Circulatory levels of lncRNAs might be used as markers for PD. In the present work, we measured expression levels of HULC, PVT1, MEG3, SPRY4-IT1, LINC-ROR and DSCAM-AS1 lncRNAs in the circulation of patients with PD versus healthy controls. Expression of HULC was lower in total patients compared with total controls (Expression ratio (ER)=0.19, adjusted P value<0.0001) as well as in female patients compared with female controls (ER=0.071, adjusted P value=0.0004). Expression of PVT1 was lower in total patients compared with total controls (ER=0.55, adjusted P value=0.0124). Expression of DSCAM-AS1 was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=5.67, P value=0.0029) and in male patients compared with male controls (ER=9.526, adjusted P value=0.0024). Expression of SPRY4-IT was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=2.64, adjusted P value<0.02) and in male patients compared with male controls (ER=3.43, P value<0.03). Expression of LINC-ROR was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=10.36, adjusted P value<0.0001) and in both male and female patients compared with sex-matched controls (ER=4.57, adjusted P value=0.03 and ER=23.47, adjusted P value=0.0019, respectively). Finally, expression of MEG3 was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=13.94, adjusted P value<0.0001) and in both male and female patients compared with sex-matched controls (ER=8.60, adjusted P value<0.004 and ER=22.58, adjusted P value<0.0085, respectively). ROC curve analysis revealed that MEG3 and LINC-ROR have diagnostic power of 0.77 and 0.73, respectively. Other lncRNAs had AUC values less than 0.7. Expression of none of lncRNAs was correlated with age of patients, disease duration, disease stage, MMSE or UPDRS. The current study provides further evidence for dysregulation of lncRNAs in the circulation of PD patients.

Introduction

As a progressive neurodegenerative condition, Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects 2-3% of the whole population age more than 65 years with a gradually increasing incidence (1). This disorder is characterized by resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity of muscles, balance disturbances, postural instability and a number of non-motor manifestations, particularly cognitive dysfunction which affects the vast majority of PD patients (2). PD is associated with alteration of expression and activity of several genes, particularly those related with dopamine-dependent oxidative stress (3). Many genetic and environmental risk factors of PD converge in pathways inducing cell death in dopaminergic neurons. In fact, high level of dopamine in cytoplasm of nigral neurons has been associated with dopamine oxidation and production of reactive oxygen species which have detrimental effects on these neurons (3). Cumulatively, dopamine-associated oxidative stress, dysfunction of synaptic vesicles and misfolding of α-synuclein produce an extending vicious cycle which perpetually results in death of dopaminergic neurons (3). PD has been associated with dysregulation of several transcripts among them are long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) (4). LncRNAs have possible role in brain development. A multi-disciplinary study of four highly conserved and brain-expressed lncRNA has shown that lncRNAs are functional transcripts with important roles in the development of vertebrate brain. This speculation is based on the observed preservation of lncRNAs across various amniotes, obvious conservation of their exons structures, and resemblances in lncRNA signature throughout the embryonic and early postnatal phases (5).

A number of lncRNAs affect pathoetiology of PD. For instance, NEAT1 has been shown to promote the MPTP-associated autophagy in PD via increasing the stability of PINK1 protein (6). Moreover, HOTAIR has been found to target miR‐126‐5p to facilitate progression of PD via RAB3IP (7). A recent study has reported lower plasma levels of MEG3 in PD patients compared with control group. Notably, authors have reported negative correlations between MEG3 levels and Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) stage and Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) score in PD group. However, expression of this lncRNA has been positively correlated with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores. Thus, authors have suggested close relation between MEG3 expression and worsening of non-motor symptoms, cognitive impairments, and PD stage (8).

In the present work, we measured expression levels of HULC, PVT1, MEG3, SPRY4-IT1, LINC-ROR and DSCAM-AS1 lncRNAs in the circulation of patients with PD versus healthy controls. These lncRNAs have been suggested to affect immune responses and participate in the pathoetiology of immune-related disorders of nervous system (9). Moreover, expressions of LINC-ROR, MEG3 and SPRY4-IT1 have been shown to be higher in patients with schizophrenia compared with healthy subjects (10). These lncRNAs might also affect pathoetiology of PD, since they can influence fundamental processes in this disorder such as autophagy. For instance, HULC has been found to target ATG7 (11), an autophagy related gene with crucial functions in the development of PD (12). Moreover, PVT1 can induce cytoprotective autophagy (13). MEG3 triggers autophagy through modulation of activity of ATG3 (14). The role of LINC-ROR in regulation of autophagy has been investigated in the context of cancer (15). These lncRNAs might also affect neurotoxic events. For instance, SPRY4-IT1 has been shown to modulate ketamine-associated neurotoxicity in human embryonic stem cell-originated neurons (16). Besides, DSCAM-AS1 has interaction with hnRNPL (17), an RNA-binding protein with possible role in the etiology of PD (18). However, their role of the development of PD has been less studied.

Materials and Methods

Patient and Controls

The present project was performed using the blood specimens collected from 50 cases of PD (Female/male ratio: 13/37) and 58 healthy individuals (Female/male ratio: 20/38). Patients were enlisted during January 2020-April 2021 from Farshchian, Hamadan, Iran. PD cases were diagnosed based on criteria proposed by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (19). Exclusion criteria were current or chronic infections, neoplastic conditions or any systemic disorder. H&Y staging system was used for evaluation of the functional disability associated with PD (20). Moreover, the MMSE was used as a screening tool for PD dementia, with values below 26 showing possible dementia (21). Moreover, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) was used as a rating tool to estimate the severity and progression of PD (22). Persons enlisted in the control group had no personal or family history of any neuropsychiatric disorder. The study protocol was confirmed by ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. All PD patients and controls signed the informed consent forms.

Expression Assays

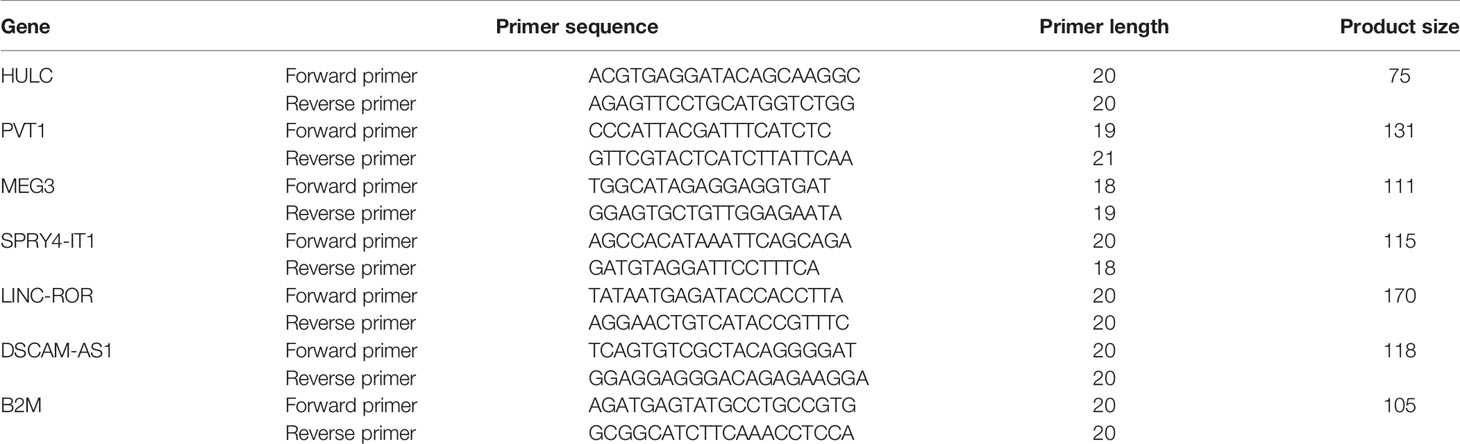

A total of 5 mL of peripheral blood was collected from PD patients and healthy persons in EDTA-blood collection tubes. Total RNA was extracted from these specimens using GeneAll extraction kit (Seoul, South Korea). The quality and quantity of RNA were assessed using gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop equipment. Afterwards, cDNA was made from roughly 75 ng of RNA using BioFact™ kit (Seoul, South Korea). The Ampliqon real time PCR master mix (Denmark) was used for making PCR reactions. Primers were designed so that the amplicon contains exon-intron boundary. Tests were accomplished in StepOnePlus™ RealTime PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). Table 1 shows primers sequences. PCR program comprised a preliminary activation stage for 5 minutes at 94°C, and 40 cycles at 94°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 45 seconds.

Statistical Methods

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v.18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical assessments. Graphics were created using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA. Expressions of lncRNAs in each sample were calculated using the Efficiency adjusted Ct of normalizer gene (B2M) - Efficiency adjusted Ct of target gene (comparative –delta Ct method). A two-way ANOVA was used to analyze effects of disease and gender on expression level of lncRNA in peripheral blood of patients and controls. Tukey post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons between subgroups. The “– delta Ct” Data in the figures were plotted as box and whisker plots (including the median [line], mean [cross], interquartile range [box], and minimum and maximum values. The delta delta Ct value was determined by subtracting the delta Ct of the control sample from the individual delta Ct of the test sample. The fold change of the test sample relative to the control sample was determined by 2-delta delta Ct and was shown as lower limit-mean and upper limit in the figures and table. The correlations between transcript levels of lncRNAs were evaluated using regression model and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The partial correlation between expression levels and age of study participants, disease stage (Hoehn & Yahr stage), disease duration, MMSS and UPDRES was described by R and P values. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were depicted to appraise the diagnostic power of expression levels of lncRNAs. Youden’s J parameter was measured to find the optimum threshold. P value < 0.05 was considered as significant. The significance of difference in mean values of lncRNAs expression (mean of –delta Ct method) between two subgroups of patients using L-DOPA and other drugs was computed using the t-test. Dynamic principal component analysis of lncRNA expression profile was used to cluster samples via Gene Expression software (GenEx SW, Multid Analysis AB, Göteborg, Sweden). Normalized values were used for principal component analysis. Heatmaps were generated by using GenEx software.

Results

General Data of Cases

Table 2 shows the clinical data and demographic information of PD cases.

Expression Assays

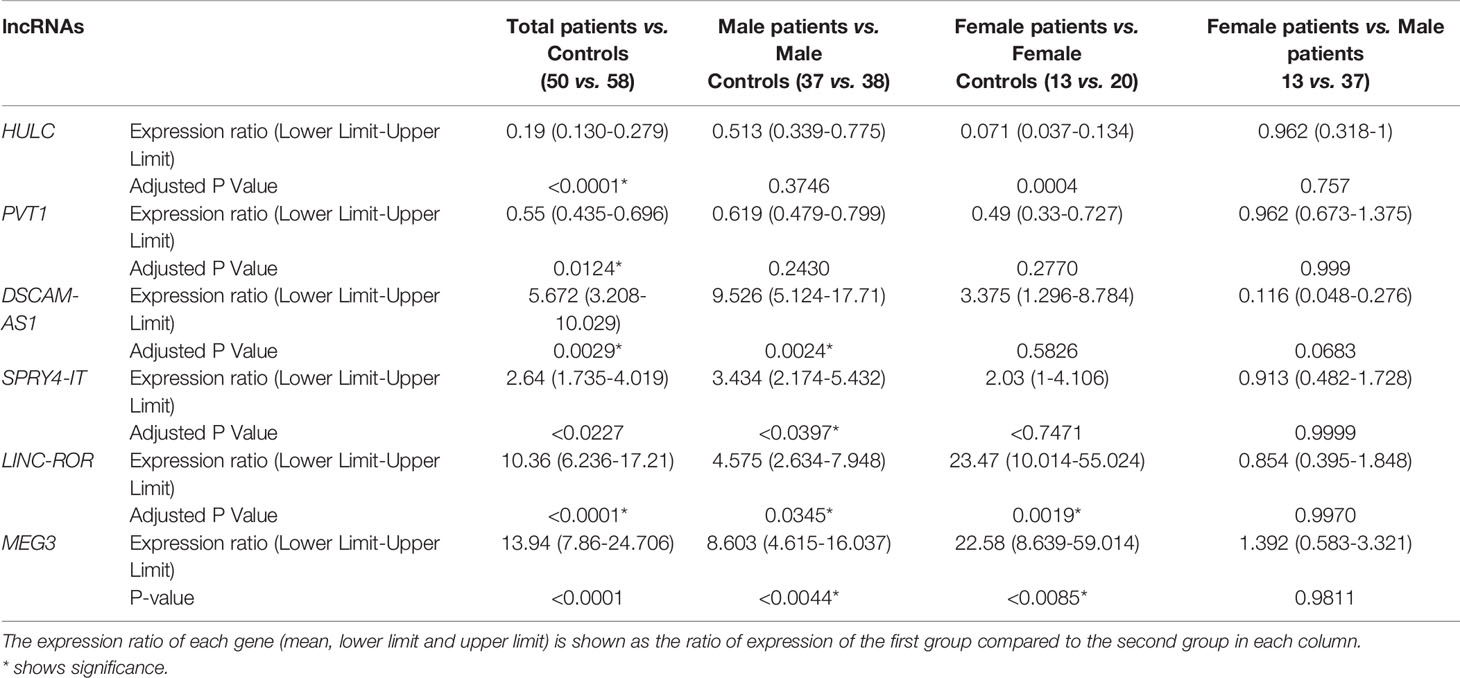

Expression of HULC was lower in total patients compared with total controls (Expression ratio (ER)=0.19, adjusted P value<0.0001) as well as in female patients compared with female controls (ER=0.071, adjusted P value=0.0004). Expression of PVT1 was lower in total patients compared with total controls (ER=0.55, adjusted P value=0.0124). Expression of DSCAM-AS1 was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=5.67, P value=0.0029) and in male patients compared with male controls (ER=9.526, adjusted P value=0.0024). Expression of SPRY4-IT was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=2.64, adjusted P value<0.02) and in male patients compared with male controls (ER=3.43, P value<0.03). Expression of LINC-ROR was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=10.36, adjusted P value<0.0001) and in both male and female patients compared with sex-matched controls (ER=4.57, adjusted P value=0.03 and ER=23.47, adjusted P value=0.0019, respectively). Finally, expression of MEG3 was higher in total patients compared with total controls (ER=13.94, adjusted P value<0.0001) and in both male and female patients compared with sex-matched controls (ER=8.60, adjusted P value<0.004 and ER=22.58, adjusted P value<0.0085, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3 The results of expression study of lncRNAs in peripheral blood of patients with PD compared with healthy controls.

Figures 1 and 2 show relative expression of expression levels of lncRNAs and their fold changes in PD patients versus controls.

Figure 1 Relative expression levels of lncRNAs in PD patients versus controls (*P value < 0.05, **P value < 0.001, ***P < 0.001 and ****P value < 0.0001).

Figure 2 Fold changes of lncRNAs in PD patients versus controls (*P value < 0.05, **P value < 0.001 and ****P value < 0.0001).

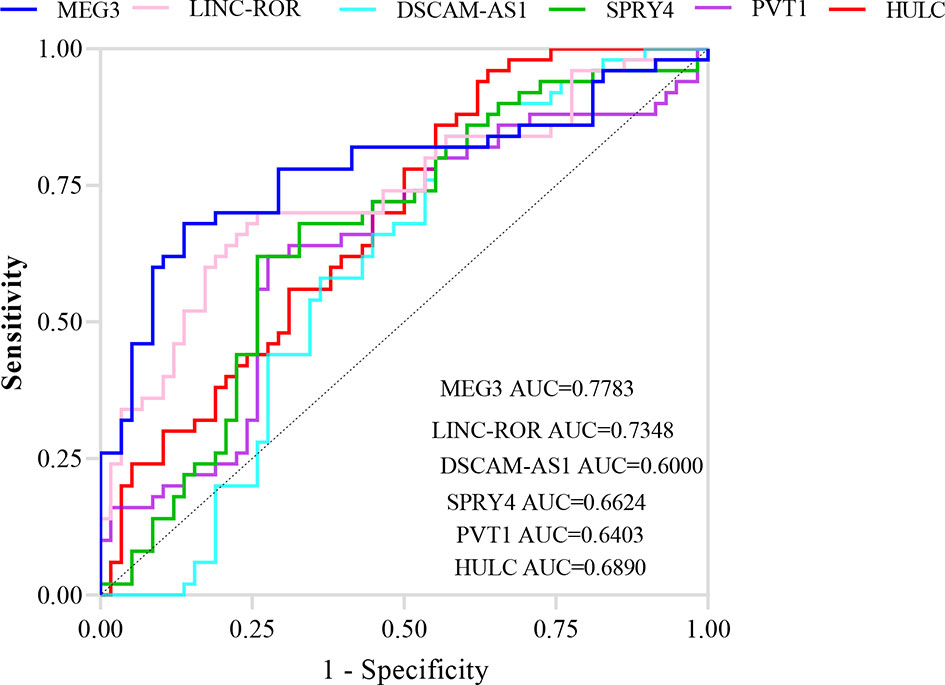

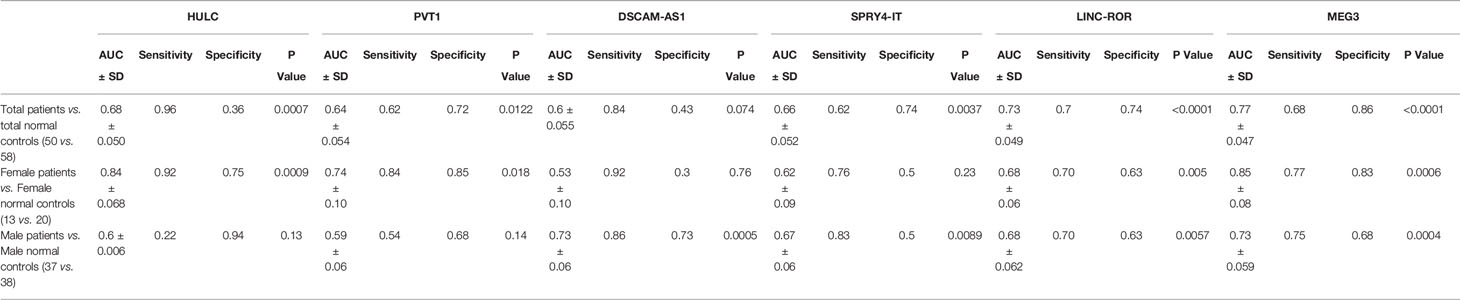

ROC curve analysis revealed that MEG3 and LINC-ROR have diagnostic power of 0.77 and 0.73, respectively (Figure 3). Other lncRNAs had AUC values less than 0.7.

Table 4 shows sensitivity, specificity and AUC values of each lncRNA in separation of PD cases from controls. This type of analysis was repeated for distinct sex-based groups. HULC and PVT1 could differentiate only between female subgroups. On the other hand, DSCAM-AS1 and SPRY4-IT could differentiate only between male subgroups.

Table 4 Sensitivity, specificity and AUC values of each lncRNA in separation of PD cases from controls.

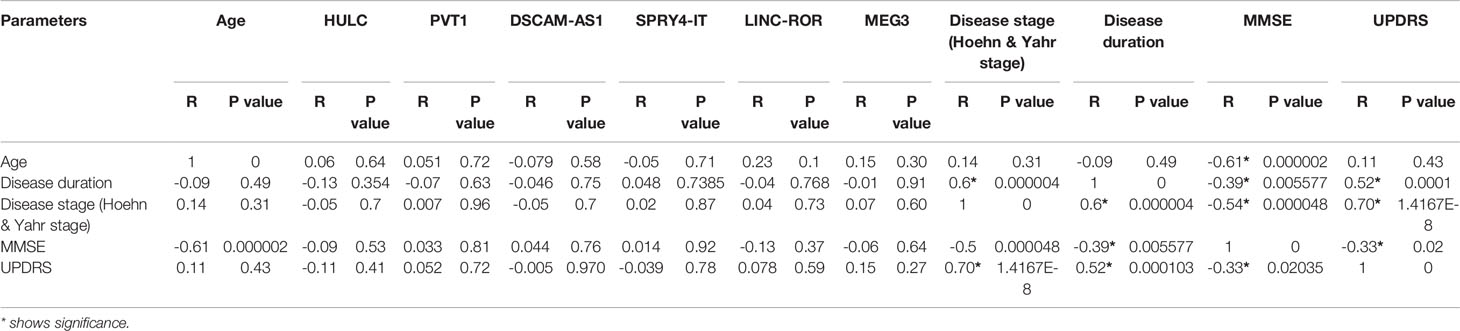

Expression of none of lncRNAs was correlated with age of patients, disease duration, disease stage, MMSE or UPDRS (Table 5).

Table 5 The results of partial correlation between expression of lncRNAs and age, Disease duration, Disease stage, MMSE and UPDRS [Controlled for sex, Diseases duration was classified into 3 ranges (1-5, 6-10 and more than 10 years)].

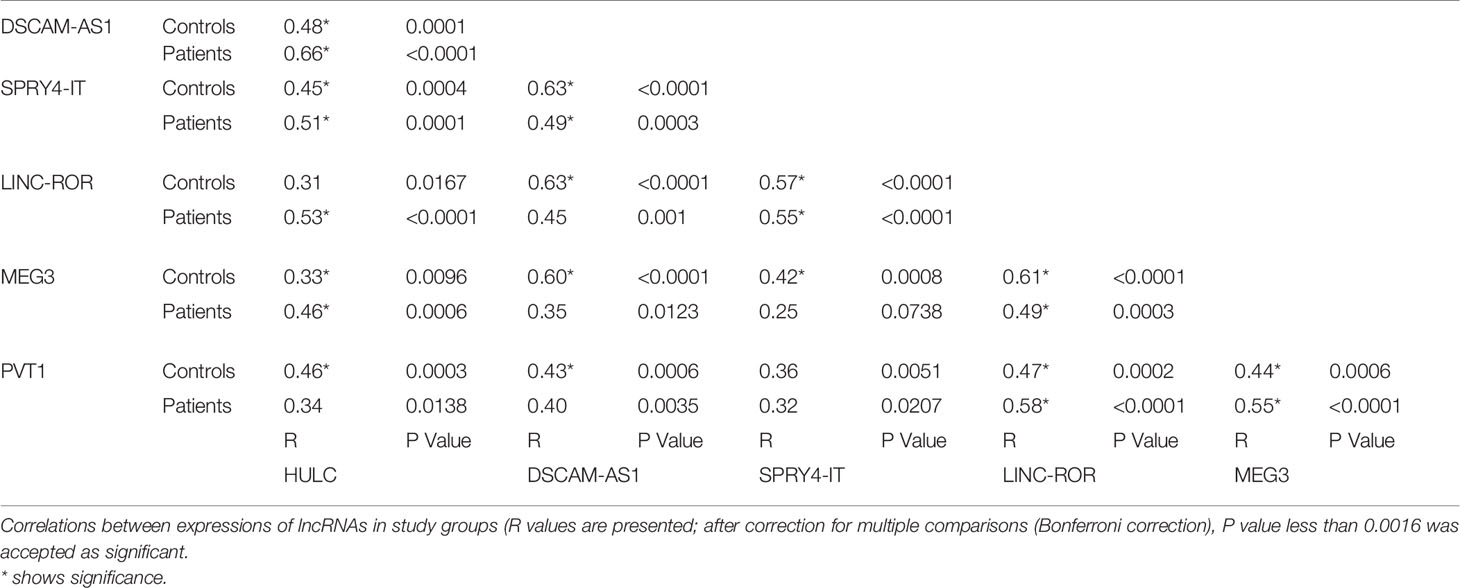

Expressions of lncRNAs were significantly correlated with each other in both PD patients and controls (Table 6).

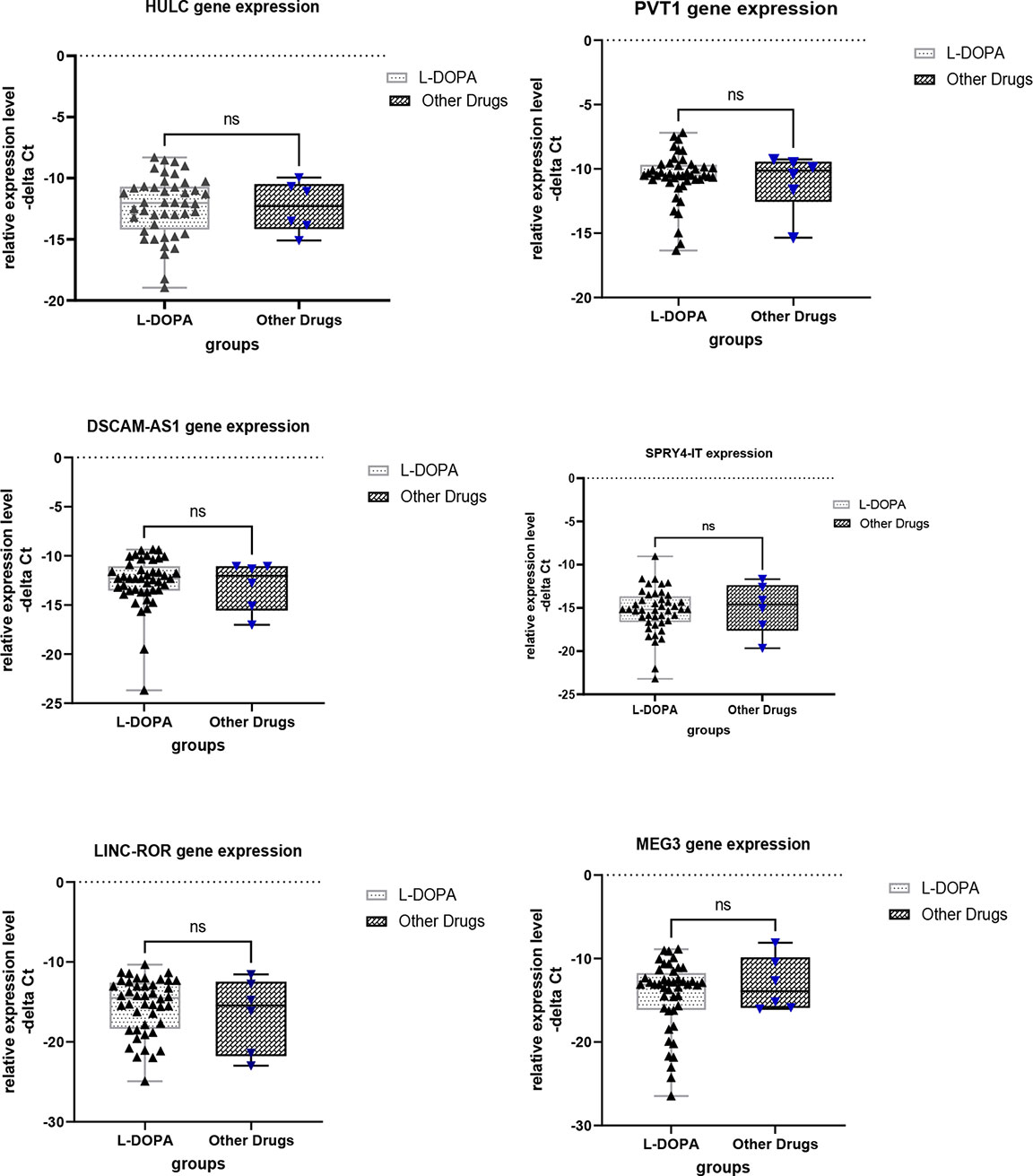

Finally, we compared expression levels of lncRNAs in patients receiving L-DOPA versus those being under treatment with other drugs (Figure 4). This analysis revealed no significant difference in expression of lncRNAs between these two groups.

Figure 4 Comparison of expression levels of lncRNAs between patients receiving L-DOPA and those under treatment with other drugs. ns, not significant.

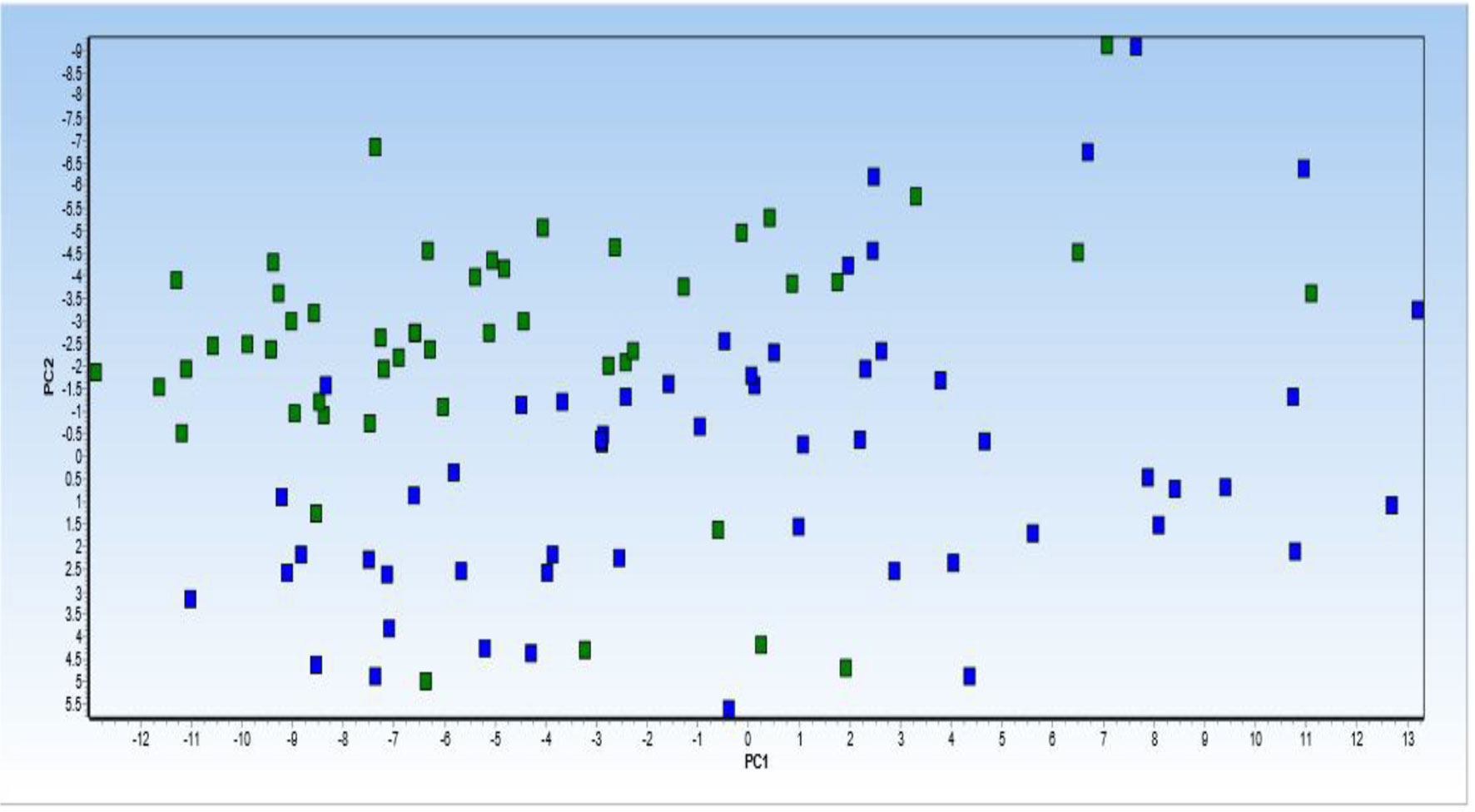

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on 6 lncRNA expression profiles in patients with PD compared with healthy control. PCA of the 6 lncRNAs expression data could not clearly clusters samples collected from healthy controls (blue squares) and patients with Parkinson (green squares) into their respective groups (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Principal component analysis (PCA) of 6 lncRNA expression profiles in patients with Parkinson diseases compared with healthy control. PCA of the 6 lncRNAs expression data could not clearly clusters samples collected from healthy controls (blue squares) and patients with Parkinson (green squares) into their respective groups. Normalized values were used for principal component analysis.

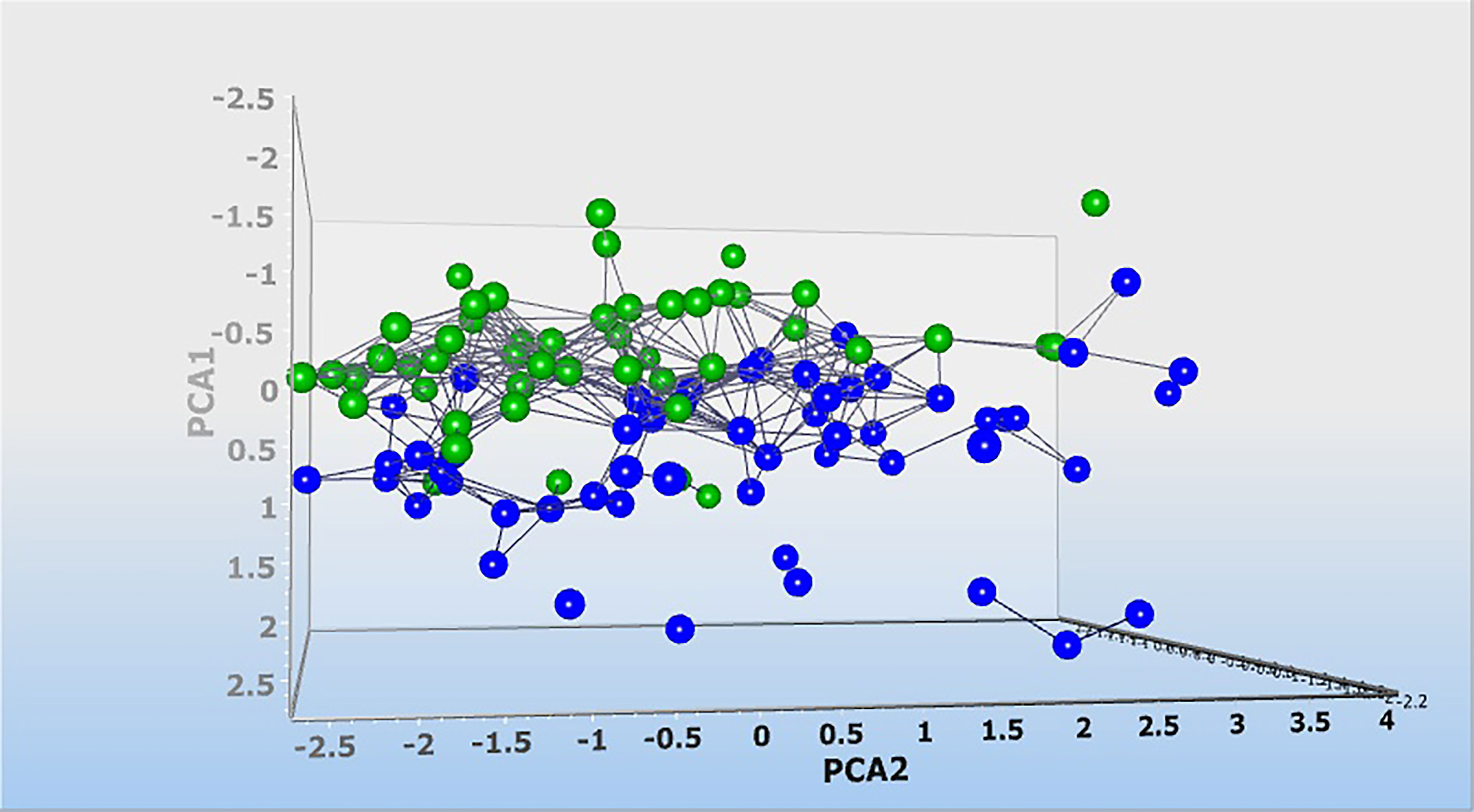

Then, dynamic principal component analysis (DPCA) was performed on the lncRNA results from the analyzed samples to determine how the 6 differentially expressed lncRNAs were distributed among the samples from PD patients and healthy controls. DPCA excluded lncRNA PVT1 with low standard deviation. Thus, 5 lncRNAs expression data were used to clusters samples collected from healthy controls (blue squares) and patients with PD (green squares) into their respective groups. As shown in Figure 6, the DPCA almost clearly separated the samples collected from healthy controls (blue squares) and patients with PD (green squares) into their respective groups.

Figure 6 Dynamic principal component analysis (DPCA) of 6 lncRNA expression profiles. DPCA was used to filter out and exclude lncRNA with low standard deviation. LncRNA PVT1 was excluded and 5 lncRNA expression data were used to clusters samples collected from healthy controls (blue squares) and patients with Parkinson (green squares) into their respective groups. Normalized values were used for principal component analysis.

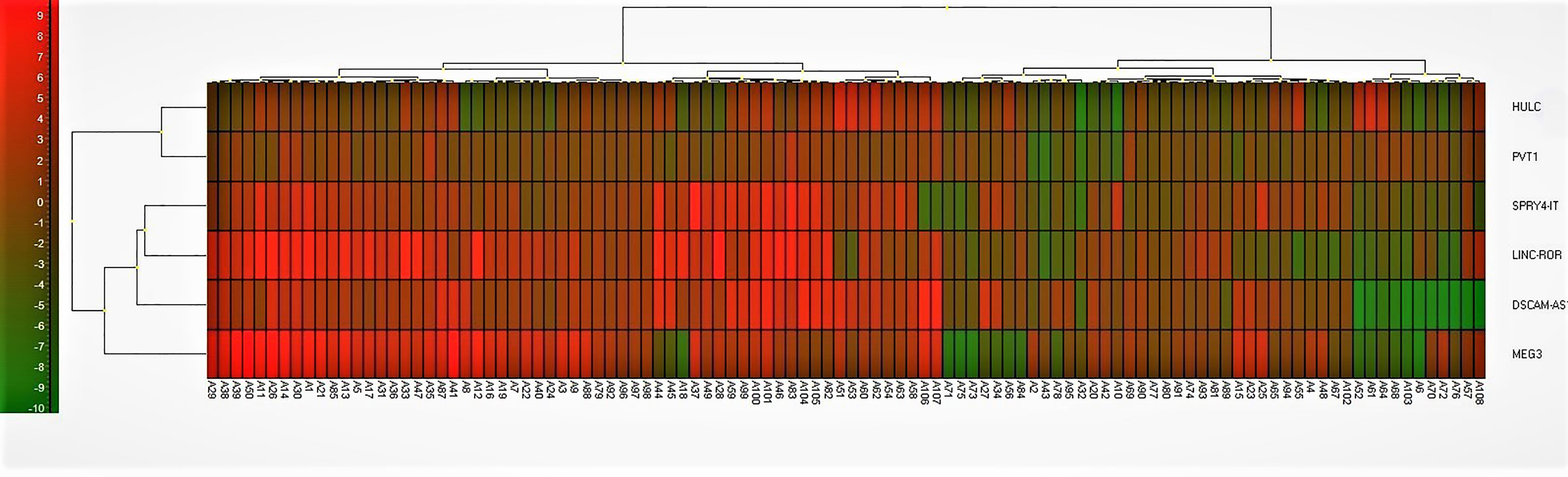

Finally, we depicted Log2 Fold Change Heat Map for lncRNA levels (Figure 7). Most of patient samples (A1-A50) were located on the left side with increased expression of lncRNAs studied in this work.

Figure 7 Log2 Fold Change Heat Map. A heat map for the subjects with Parkinson diseases and healthy control. Log2 fold change was calculated based on delta Ct value compared to the control samples. Red color implies increased expression while green implies decreased expression. LncRNAs on the right are clustered using a hierarchical clustering method (Ward’s method, Euclidean distances) and 5 clusters were found. Cluster 1 = HULC and PVT1; Cluster 2 = SPRY4-IT; Cluster 3 = LINC-ROR; Cluster 4 = DSCAM-AS1; Cluster 5 = MEG3. Most of patient samples (A1-A50) were located on the left side with increased expression of lncRNAs studied in this work.

Discussion

In the present work, we measured expression levels of 6 lncRNAs in the circulation of patients with PD versus healthy controls. Expression of HULC was lower in total patients compared with total controls as well as in female patients compared with female controls. This lncRNA has a role in regulation of immune response, since up-regulation of HULC has been shown to has a necessary role in pro-inflammatory responses in the course of LPS-associated sepsis (23). In addition, HULC has a role in regulation of apoptosis. Experiments in the contexts of various neoplasms have indicated an anti-apoptotic role for HULC (24, 25). This function of HULC has not been assessed in neurons. If this lncRNA exerts similar role in neurons, down-regulation of HULC in the circulation of patients with PD might be associated with higher apoptosis of neurons. It has been widely accepted that apoptosis of nigral dopaminergic neurons has essential roles in the development of PD (26). Various mechanisms including both intrinsic and extrinsic routes participate in the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in this disorder (26). However, the exact position of HULC within this complicated network of apoptosis-related mechanisms needs to be clarified.

Expression of PVT1 was lower in total patients compared with total controls. PVT1 silencing has been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit cell cycle transition via modulating EFGR pathway (27). Experiment in animal model of PD has shown the impact of EGFR signaling in cell death of dopaminergic neurons in the course of neuro-apoptosis (28).

Expressions of DSCAM-AS1 and SPRY4-IT were higher in total patients compared with total controls and in male patients compared with male controls. DSCAM-AS1 has been previously reported as an Estrogen receptor α-dependent lncRNA with critical roles in the regulation of cell growth and migration (29). Since estrogen and some selective estrogen receptor modulators have been suggested as possible therapeutic options for PD (30), identification of the molecular mechanism of participation of DSCAM-AS1 in the pathetiology of PD has clinical significance. The observed sex-biased dysregulation of this lncRNA among PD patients further support the interaction between estrogen receptor and this lncRNA. SPRY4-IT1 has been shown to modulate ketamine-associated neurotoxicity in human embryonic stem cell-originated neurons via EZH2 (16). Up-regulation of this lncRNA in the circulatory blood of PD patients might be a compensatory mechanism to decrease PD-associated neuron loss.

Expressions of LINC-ROR and MEG3 were higher in total patients compared with total controls and in both male and female patients compared with sex-matched controls. LINC-ROR has been shown to regulate apoptosis through influencing p53 ubiquitination via regulation of miR-204-5p/MDM2 axis (31). MEG3 has been shown to affect neuron apoptosis through miR-181b-12/15-LOX signaling (32). Thus, modulation of apoptotic pathways is possible mechanism of participation of these lncRNAs in PD.

ROC curve analysis revealed that MEG3 and LINC-ROR have diagnostic power of 0.77 and 0.73, respectively. Other lncRNAs had AUC values less than 0.7. Thus, MEG3 and LINC-ROR are possible markers for PD.

Expression of none of lncRNAs was correlated with age of patients, disease duration, disease stage, MMSE or UPDRS. The current study provides further evidence for dysregulation of lncRNAs in the circulation of PD patients. Therefore, expression level of these lncRNAs is independent from PD course.

Moreover, the DPCA almost clearly separated the samples collected from healthy controls and patients with PD into their respective groups. This suggests that the observed lncRNA differences are associated with the pathophysiology of PD, and these lncRNA might constitute an important biomarker signature for PD.

In conclusion, the current study shows dysregulation of lncRNAs in the circulation of PD patients. The study has limitations regarding small sample size and lack of inclusion of drug-naïve patients. Moreover, it is important to characterize each lncRNA in detail, such as the structure and function of each lncRNA, and to quantify the role of lncRNA in PD in multinational multicenter studies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was confirmed by ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

SG-F wrote the draft and revised it. MT and BH designed and supervised the study. SE analyzed the data. KH, MG, and PG performed the experiment. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The current study was supported by a grant from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, Halliday GM, Brundin P, Volkmann J, et al. Parkinson Disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers (2017) 3(1):1–21. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13

2. Marsili L, Rizzo G, Colosimo C. Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson’s Disease: From James Parkinson to the Concept of Prodromal Disease. Front Neurol (2018) 9:156. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00156

3. Lotharius J, Brundin P. Pathogenesis of Parkinson's Disease: Dopamine, Vesicles and α-Synuclein. Nat Rev Neurosci (2002) 3(12):932–42. doi: 10.1038/nrn983

4. Rezaei O, Nateghinia S, Estiar MA, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. Assessment of the Role of non-Coding Rnas in the Pathophysiology of Parkinson's Disease. Eur J Pharmacol (2021) 896:173914. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173914

5. Chodroff RA, Goodstadt L, Sirey TM, Oliver PL, Davies KE, Green ED, et al. Long Noncoding RNA Genes: Conservation of Sequence and Brain Expression Among Diverse Amniotes. Genome Biol (2010) 11(7):1–16. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r72

6. Yan W, Chen ZY, Chen JQ, Chen HM. Lncrna NEAT1 Promotes Autophagy in MPTP-Induced Parkinson's Disease Through Stabilizing PINK1 Protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2018) 496(4):1019–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.149

7. Lin Q, Hou S, Dai Y, Jiang N, Lin Y. Lncrna HOTAIR Targets Mir-126-5p to Promote the Progression of Parkinson's Disease Through RAB3IP. Biol Chem (2019) 400(9):1217–28. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0431

8. Quan Y, Wang J, Wang S, Zhao J. Association of the Plasma Long non-Coding RNA MEG3 With Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol (2020) 11. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.532891

9. Gholipour M, Taheri M, Mehvari Habibabadi J, Nazer N, Sayad A, Ghafouri-Fard S. Dysregulation of Lncrnas in Autoimmune Neuropathies. Sci Rep (2021) 11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95466-w

10. Fallah H, Azari I, Neishabouri SM, Oskooei VK, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. Sex-Specific Up-Regulation of Lncrnas in Peripheral Blood of Patients With Schizophrenia. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49265-z

11. Chen S, Wu D-D, Sang X-B, Wang L-L, Zong Z-H, Sun K-X, et al. The Lncrna HULC Functions as an Oncogene by Targeting ATG7 and ITGB1 in Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis (2017) 8(10):e3118–e. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.486

12. Niu XY, Huang HJ, Zhang JB, Zhang C, Chen WG, Sun CY, et al. Deletion of Autophagy-Related Gene 7 in Dopaminergic Neurons Prevents Their Loss Induced by MPTP. Neuroscience (2016) 339:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.09.037

13. Huang F, Chen W, Peng J, Li Y, Zhuang Y, Zhu Z, et al. Lncrna PVT1 Triggers Cyto-Protective Autophagy and Promotes Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Development via the Mir-20a-5p/ULK1 Axis. Mol Cancer (2018) 17(1):98–. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0845-6

14. Xiu Y-L, Sun K-X, Chen X, Chen S, Zhao Y, Guo Q-G, et al. Upregulation of the Lncrna Meg3 Induces Autophagy to Inhibit Tumorigenesis and Progression of Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma by Regulating Activity of ATG3. Oncotarget (2017) 8(19):31714–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15955

15. Chen W, Yang J, Fang H, Li L, Sun J. Relevance Function of Linc-ROR in the Pathogenesis of Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol (2020) 8:696. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00696

16. Huang J, Xu Y, Wang F, Wang H, Li L, Deng Y, et al. Long Noncoding RNA SPRY4-IT1 Modulates Ketamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Neurons Through EZH2. Dev Neurosci (2021) 43(1):9–17. doi: 10.1159/000513535

17. Niknafs YS, Han S, Ma T, Speers C, Zhang C, Wilder-Romans K, et al. The Lncrna Landscape of Breast Cancer Reveals a Role for DSCAM-AS1 in Breast Cancer Progression. Nat Commun (2016) 7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12791

18. Costain WJ, Mishra RK. PLG Regulates Hnrnp-L Expression in the Rat Striatum and Pre-Frontal Cortex: Identification by Ddpcr. Peptides (2003) 24(1):137–46. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(02)00286-3

19. Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, Poewe W, Olanow CW, Oertel W, et al. MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson's Disease. Movement Disord Off J Movement Disord Soc (2015) 30(12):1591–601. doi: 10.1002/mds.26424

20. Poewe W. Global Scales to Stage Disability in PD: The Hoehn and Yahr Scale. Rating Scales Parkinsons Dis (2012) 115–22. doi: 10.1093/med/9780199783106.003.0258

21. Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué I Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the Detection of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias in People With Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2015) 2015(3):CD010783–CD. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub2

22. Ebersbach G, Baas H, Csoti I, Müngersdorf M, Deuschl G. Scales in Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurol (2006) 253(4):iv32–5. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-4008-0

23. Chen Y, Fu Y, Song Y-F, Li N. Increased Expression of Lncrna UCA1 and HULC is Required for Pro-Inflammatory Response During LPS Induced Sepsis in Endothelial Cells. Front Physiol (2019) 10:608. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00608

24. Zhao Y, Guo Q, Chen J, Hu J, Wang S, Sun Y. Role of Long non-Coding RNA HULC in Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis and Tumor Metastasis of Gastric Cancer: A Clinical and In Vitro Investigation. Oncol Rep (2014) 31(1):358–64. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2850

25. Li Y, Liu JJ, Zhou JH, Chen R, Cen CQ. Lncrna HULC Induces the Progression of Osteosarcoma by Regulating the Mir-372-3p/HMGB1 Signalling Axis. Mol Med (Cambridge Mass) (2020) 26(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00155-5

26. Singh S, Dikshit M. Apoptotic Neuronal Death in Parkinson's Disease: Involvement of Nitric Oxide. Brain Res Rev (2007) 54(2):233–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.02.001

27. Li W, Zheng Z, Chen H, Cai Y, Xie W. Knockdown of Long non-Coding RNA PVT1 Induces Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Through the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Pathway. Oncol Lett (2018) 15(5):7855–63. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8315

28. Kim IS, Koppula S, Park SY, Choi DK. Analysis of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Related Gene Expression Changes in a Cellular and Animal Model of Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci (2017) 18(2):430. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020430

29. De Bortoli M, Miano V, Ferrero G, Annaratone L, Coscujuela L, Castellano I, et al. DSCAM-AS1, a Breast Cancer Specific and Estrogen Receptor Alpha-Dependent Long Noncoding RNA, is a Key Component of the Pathway Controlling Cell Growth and Migration. In: Cancer Research. PHILADELPHIA, PA: AMER ASSOC CANCER RESEARCH 615 CHESTNUT ST, 17TH FLOOR (2017).

30. Baraka AM, Korish AA, Soliman GA, Kamal H. The Possible Role of Estrogen and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators in a Rat Model of Parkinson's Disease. Life Sci (2011) 88(19-20):879–85. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.03.010

31. Gao H, Wang T, Zhang P, Shang M, Gao Z, Yang F, et al. Linc-ROR Regulates Apoptosis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma via Modulation of P53 Ubiquitination by Targeting Mir-204-5p/MDM2. J Cell Physiol (2020) 235(3):2325–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29139

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, lncRNA, HULC, PVT1, MEG3, SPRY4-IT1, LINC-ROR, DSCAM-AS1

Citation: Honarmand Tamizkar K, Gorji P, Gholipour M, Hussen BM, Mazdeh M, Eslami S, Taheri M and Ghafouri-Fard S (2021) Parkinson’s Disease Is Associated With Dysregulation of Circulatory Levels of lncRNAs. Front. Immunol. 12:763323. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.763323

Received: 23 August 2021; Accepted: 22 October 2021;

Published: 11 November 2021.

Edited by:

Roberta Magliozzi, University of Verona, ItalyReviewed by:

Hikoaki Fukaura, Saitama Medical University, JapanRezvan Noroozi, Jagiellonian University, Poland

Amin Safa, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Honarmand Tamizkar, Gorji, Gholipour, Hussen, Mazdeh, Eslami, Taheri and Ghafouri-Fard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Taheri, TW9oYW1tYWRfODIzQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==; Soudeh Ghafouri-Fard, cy5naGFmb3VyaWZhcmRAc2JtdS5hYy5pcg==

Kasra Honarmand Tamizkar

Kasra Honarmand Tamizkar Pooneh Gorji

Pooneh Gorji Mahdi Gholipour

Mahdi Gholipour Bashdar Mahmud Hussen3

Bashdar Mahmud Hussen3 Solat Eslami

Solat Eslami Mohammad Taheri

Mohammad Taheri Soudeh Ghafouri-Fard

Soudeh Ghafouri-Fard