- Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Most animals maintain mutually beneficial symbiotic relationships with their intestinal microbiota. Resident microbes in the gastrointestinal tract breakdown indigestible food, provide essential nutrients, and, act as a barrier against invading microbes, such as the enteric pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Over the last decades, our knowledge of V. cholerae pathogenesis, colonization, and transmission has increased tremendously. A number of animal models have been used to study how V. cholerae interacts with host-derived resources to support gastrointestinal colonization. Here, we review studies on host-microbe interactions and how infection with V. cholerae disrupts these interactions, with a focus on contributions from the Drosophila melanogaster model. We will discuss studies that highlight the connections between symbiont, host, and V. cholerae metabolism; crosstalk between V. cholerae and host microbes; and the impact of the host immune system on the lethality of V. cholerae infection. These studies suggest that V. cholerae modulates host immune-metabolic responses in the fly and improves Vibrio fitness through competition with intestinal microbes.

Introduction

Background

A complex set of interactions among host intestinal cells, and gut-resident microbes, impacts the viability of all participants. For example, commensal microbes consume intestinal nutrients, and generate metabolites that influence development, growth, metabolism, and immune system function in the host (1–8). Introduction of microbes with pathogenic potential to the gut lumen, or rearrangements to the composition or distribution of gut microbial communities, can have substantial impacts on intestinal homeostasis for the host (9). In particular, shifts in niche occupancy by gut bacteria, or alterations to metabolic outputs from the gut microbiome, can result in the development of severe intestinal disease (10–13). For example, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a common human commensal, cleaves host glycans to produce fucose, a sugar that modulates the virulence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (14). Despite the importance of regulated molecular exchanges among host and microbial cells for host fitness and microbial function, our knowledge of pathogen-commensal interactions in the context of immune-metabolic regulation and intestinal disease is still quite limited. To fully understand such complex, multipartite interactions, it is essential that we deploy all relevant experimental systems at our disposal.

Drosophila melanogaster is a valuable experimental tool for studying host-microbe interactions. Lab-raised strains of Drosophila associate with a limited number of bacterial taxa (15–17), dominated by easily cultivated Acetobacter and Lactobacillus strains that are accessible to genetic manipulation, and deployment in large-scale screens. Researchers have access to simple protocols for the establishment of flies with a defined intestinal microbiome (18, 19), and there is an abundance of publicly available lines for the genetic manipulation of fly intestinal function. Combined, these advantages allowed researchers to make substantial breakthroughs in understanding how flies interact with intestinal bacteria (20). Importantly, given the extent to which genetic regulators of intestinal homeostasis are conserved between vertebrates and invertebrates (20, 21), discoveries made with the fly have the potential to illuminate foundational aspects of host-microbe interactions. However, there are several key differences to note between flies and vertebrates that partially limit the utility of the fly model. Specifically, flies lack lymphocyte-based adaptive defenses, and the fly microbiome is considerably different to that reported in vertebrates.

Antimicrobial Defenses in the Fly Intestine

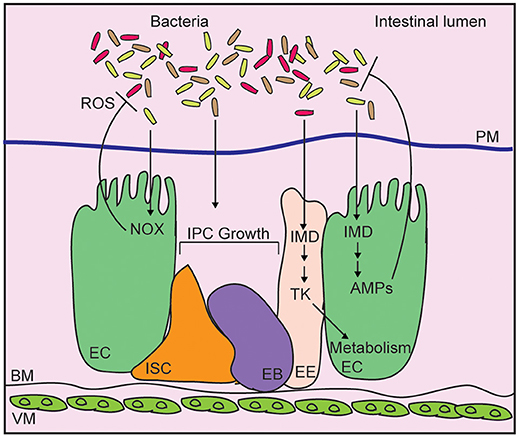

Drosophila integrate physical, chemical, proliferative, and antibacterial strategies to neutralize intestinal microbes, and prevent systemic infection of the host (Figure 1) (22, 23). The chitinous peritrophic matrix lines the midgut, and presents a physical barrier against bacterial invasion (24), similar to the mucus lining of the vertebrate intestinal tract. The germline-encoded immune deficiency (IMD) antibacterial defense pathway, a signaling pathway similar to the mammalian Tumor Necrosis Factor pathway (25), detects bacterial diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan, and acts through the NF-κB transcription factor family member, Relish, to induce expression of antimicrobial peptides (26–29). At the same time, Dual Oxidase (Duox) and NADPH Oxidase (Nox) protect the host from gut bacteria through the generation of bactericidal reactive oxygen species (30, 31). Evolutionarily conserved growth regulatory pathways respond to damage of epithelial cells by promoting a compensatory growth and differentiation of intestinal stem cells (ISCs) in infected flies (32–35). This adaptive repair mechanism maintains the epithelial barrier, and prevents systemic infection of the host. Combined, these antibacterial defenses protect the host from infection, and maintain beneficial relationships between the fly and their gut microbiome.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the adult Drosophila midgut. Intestinal bacteria are contained within the lumen by a chitinous peritrophic matrix (PM). Bacteria diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan activates the immune deficiency (IMD) pathway in enterocytes (EC), leading to production of antimicrobial peptides (AMP). In enteroendocrine cells (EE), IMD controls expression of the metabolism-regulatory hormone Tachykinin (Tk). Epithelial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by NADPH oxidases (NOX) also contribute to bacterial killing while cues from the bacterial microbiome promote the growth of intestinal progenitor cells (IPC), composes of intestinal stem cells (ISC), and enteroblasts (EB).

The Drosophila Microbiome

The fly microbiome is transmitted horizontally through the deposition of bacteria on the outer surface of freshly laid embryos, and is maintained through the ingestion of food contaminated with bacteria (36). Gut bacteria regulate Drosophila intestinal homeostasis by affecting metabolism, growth, and immunity in the host. Interactions between the host and gut microbiota have been extensively covered in several recent reviews (20, 37–39), and will not be discussed in detail here. In brief, detailed studies have uncovered roles for symbiotic Lactobacillus and Acetobacter species in the control of fly metabolism and growth (40–42). For example, a dehydrogenase activity in Acetobacter pomorum, produces acetic acid that regulates insulin signaling, carbohydrate, and lipid levels in the host (40). In addition to the effects of individual symbionts on nutrient allocations in the host, interactions among bacterial communities have significant effects on host metabolism, growth, and physiology (43–47). Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) has emerged as a particularly useful tool to study interactions between the host, the intestinal microbiota, and an enteric pathogen. A pioneering study in 2005 established that flies are susceptible to oral infection with V. cholerae, dying within a few day from a diarrheal disease with symptoms similar to cholera in humans (48). The genetic tractability of the fly and V. cholerae established this system as a very attractive model to identify key host and microbial determinants of pathogenesis. In the following years, a number of studies uncovered complex roles for metabolism, host immunity, epithelial growth, and microbial antagonism in the outcome of V. cholerae pathogenesis in the fly. In this review, we will discuss key findings from these studies, and outline what they tell us about host-microbe interactions in general, and V. cholerae-mediated pathogenesis in particular.

Vibrio cholerae: Pandemics and Pathogenicity

Vibrio cholerae is a curved, Gram-negative member of the Vibrionaceae family of Proteobacteria (49). It inhabits aquatic environments, and copepods and chironomids are reported as natural reservoirs in marine ecosystems (50, 51). Intestinal colonization by V. cholerae causes the diarrheal disease, cholera, and is considered a substantial public health threat, especially in countries with poor sanitation and contaminated water (52). The first cholera pandemic emerged in 1817, with an expansion of cholera beyond the Indian subcontinent (53). Since then, the world has witnessed an additional six pandemics, with the seventh pandemic ongoing (54). Models that estimate cholera burden predict ~3 million cases of disease per year, resulting in roughly 100,000 deaths (55).

Vibrio cholerae strains are divided into classical and non-classical serotypes, with classical ones expressing the O1 antigen on their surface (56, 57). Classical serotypes are further subdivided into two biotypes—classical and El Tor—that differ in the expression of a number of markers, such as hemolysins (58–61). The outbreak of epidemic cholera that spread through southeast Asia in 1992 is caused by the non-classical strain of V. cholerae 0139 (62), whereas the ongoing pandemic that originated in Indonesia in 1961 is caused by the El Tor biotype (63). El Tor causes a milder cholera disease (64), with infected individuals frequently remaining asymptomatic early in infection (65).

Vibrio cholerae encodes several virulence factors that regulate survival, colonization, and pathogenicity (66–69). Cholera toxin (CT) is a hexameric adenosine diphosphate-ribosyl transferase that contains one A subunit surrounded by five B subunits (70, 71). Upon release into the intestinal lumen via a type two secretion system (72), the B pentamer of CT interacts with host GM1 ganglosides (73), permitting toxin endocytosis, and a subsequent cytosolic release of the A1 subunit (74). A1 ADP-ribosylates the Gs alpha subunit, locking Gαs in an active state (75). Active Gαs elevates adenylate cyclase activity, greatly increasing levels of 3′,5′-cyclic AMP, resulting in excess protein kinase A (PKA) activity (76). PKA stimulates an efflux of chloride ions through the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel (77), leading to an uncontrolled flow of water, sodium and potassium ions into the intestinal lumen. This extreme, and rapid, dehydration results in the voluminous rice-water diarrhea that hallmarks cholera disease (78). In addition to CT, V. cholerae require the toxin co-regulated pilus virulence factor for pathogenesis (79). Toxin co-regulated pilus is a type IV pilus system that mediates colonization of the small intestine by a self-associate mechanism that supports the formation of bacterial microcolonies (80). Toxin co-regulated pilus also serves as the receptor for the CTXφ bacteriophage. CTXφ encodes ctxAB, and converts benign V. cholerae to pathogenic strains. The ability to synthesize toxin co-regulated pilus is advantageous for V. cholerae in aquatic environments, as it improves V. cholerae fitness by facilitating inter-bacterial interactions during colonization of host chitinaceous surfaces (81).

Although fluid replacement through oral rehydration solutions, antibiotic therapy, and vaccines are effective treatment options for patients with cholera, increased rates of antibiotic resistance among classical (82) and non-classical (83) strain of V. cholerae complicate treatment of the disease. Therefore, new antibacterial strategies that effectively target V. cholerae virulence factors are critical to contain this deadly disease. Over the last century, a variety of animal models that include rabbits, mice, fish, and flies, have been used to study Vibrio-host interactions and each of these models have added to our understanding of virulence, host responses to infection, interactions between Vibrio and host microbes, and cholera vaccine development.

The Rabbit Model

The first animal model to study V. cholerae dates back to 1884 when Nicati and Rietschin inoculated V. cholerae into the duodenum of guinea pigs, resulting in cholera-like symptoms (84). Since then, both infant and adult rabbit models of cholera have been widely used by researchers (85–87). As adult rabbits are resistant to oral infection with V. cholerae, the pathogen is typically introduced to the animal by ligated ileal loop surgery. In this technique, the small intestine of the rabbit is sealed at two ends, and the pathogen is delivered by injection into the ligated loop, allowing direct measurement of intestinal fluid secretion (88). The rabbit model has been very instructive for understanding V. cholerae distribution in the small intestine during infection, the importance of the mucosal barrier to prevent systemic infection of V. cholerae, and mechanisms of V. cholerae attachment to the intestinal epithelium (89, 90). As infant rabbits are capable of developing toxin co-regulated pilus-dependent cholera, they have been useful to study the reactogenicity associated with developing live attenuated V. cholerae vaccines as well (91). However, despite these advances, Vibrio pathogenesis studies using the rabbit ligated ileal loop model are labor-intensive, and do not replicate the normal route of infection. An alternative, oro-gastric infection model with infant rabbits pre-treated with the stomach acid production inhibitor, Cimetidine, allows oral infection and provides a valuable adult mammal model that circumvents needs for surgical interventions (87).

The Mouse Model

The infant or suckling mouse in commonly used to study V. cholerae pathogenesis (92). In this model, infant mice are infected via the oro-gastric route. In the infant mouse, the intestinal microbiome has not fully developed, allowing V. cholerae to colonize the host with diminished colonization resistance from commensal microbes. Studies working with infant mice have uncovered essential virulence factors of V. cholerae. For example, the toxin co-regulated pilus (93), and ToxR (69), which regulates toxin co-regulated pilus expression were originally characterized in the suckling mouse model. The adult mouse model was also a significant contributor to understanding the mechanisms of V. cholerae pathogenesis using accessory toxins such as hemolysin, hemagglutinin/protease, and multifunctional auto-processing RTX toxin (94). These observations were important to understand the ability of V. cholerae to express toxins other than CT to prolong its colonization in the host without severe diarrheal symptoms. However, this model comes with some limitations, as suckling mice do not develop watery diarrhea, and lymphocyte-based immune defenses are not fully developed in the host (95–97). Furthermore, as infant mice are separated from their mothers, they have a limited survival and reduced timeframe for research performance. Adult mice are less efficient for cholera studies as they are naturally resistant to V. cholerae colonization (98). Thus, manipulations such as removal of intestinal microbes by antibiotic treatment (99), or infection by ligated ileal loop surgery (100), are necessary for colonization of adult mice with V. cholerae.

The Zebrafish Model

V. cholerae is found in the intestinal tract of fish in the wild, where the bacteria degrades macromolecules ingested by fish via its chitinase and protease, building a commensal relationship between fish and V. cholerae (101). Analysis of cholera patients from an outbreak in 1997 showed that dried fish consumption was significantly associated with the spread of disease, implicating fish as potential vector for V. cholerae (102). Building on associations between fish and V. cholerae in the wild, the zebrafish, Danio rerio, has recently been developed recently as a natural host model to study V. cholerae (103). Importantly, pathogenic strains of V. cholerae cause a cholera-like disease characterized by host intestinal colonization, epithelial destruction, diarrhea, and the expulsion of live pathogens (103). Unlike the adult rabbit model, researchers do not require surgical interventions prior to infection, and in contrast to the mouse model, investigators are not restricted to working with antibiotic-treated juveniles (103, 104). Fish and humans have similarly complex microbiomes that shift with age and diet (105), making fish a useful model to study interactions between commensal bacteria and the invading pathogen (106). However, it is important to note that fish cannot be raised in axenic conditions, and it is technically challenging to generate and maintain fish populations with fully defined microbiota for sustained periods.

The Drosophila Model

Insects such as chironmids (107) and houseflies (108) are candidate reservoirs of V. cholerae, and some studies suggest a correlation between disease transmission and increases in fly population, during cholera outbreaks, or in areas where the disease is endemic (109). Given the association of V. cholerae with arthropod vectors, researchers tested the utility of Drosophila as a model to characterize V. cholerae pathogenesis. Drosophila infections typically involve oral delivery of the pathogen, or introduction of the pathogen into the body cavity of the fly through a septic injury (110). In contrast to non-pathogenic Vibrio strains, injection of V. cholerae into the body cavity resulted in a rapid death of infected flies, raising the possibility of using flies as a model to study V. cholerae pathogenesis (111). In a foundational study from 2005, researchers showed that continuous feeding of adult flies with V. cholerae caused a cholera-like disease characterized by loss of weight, and rapid death that required a functional Gαs in the host (48), establishing flies as a valuable model to characterize V. cholerae pathogenesis. However, in contrast to vertebrates, ctx mutants remain lethal to flies, suggesting CT-independent pathogenic mechanisms in adult flies. Furthermore, Vibrio polysaccharide-dependent biofilm formation is important for persistent colonization of the fly rectum and for V. cholerae-mediated lethality (112), whereas Vibrio polysaccharides interfere with colonization of the host intestine (113). Thus, the fly is a useful tool to identify uncharacterized virulence factors that affect interactions between V. cholerae and an arthropod host. As studies with this model progress, it will be interesting to determine how such virulence factors impact pathogenesis in vertebrate models.

Vibrio cholerae and the IMD Pathway

The IMD pathway modifies expression of host genes that control processes as diverse as bacterial killing, metabolism, and intestinal homeostasis (114–121). Mutations in the IMD pathway are linked with intestinal phenotypes that implicate IMD as a critical modifier of host-bacteria interactions. For example, IMD is required to survive enteric infections with entemopathogenic Pseudomonas entomophila (122). Additionally, IMD pathway mutants are characterized by changes to the composition of the intestinal microbiome, modified distribution of live bacteria throughout the intestine (123), and elevated bacterial loads in the intestine (17, 123–127). It is tempting to speculate that IMD controls bacterial populations through the direct release of antimicrobial peptides into the gut lumen. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study that confirmed a failure to contain infectious Gram-negative and fungal pathogens in flies that lack antimicrobial peptide genes (29). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that IMD-dependent control of bacterial populations includes inputs from other processes such as intestinal metabolism. Consistent with this hypothesis, studies have revealed links between immune and insulin activity in several models (128–132), including flies (120, 133–138), and IMD activity controls expression of the metabolism-regulatory peptide, Tachykinin, in enteroendocrine cells of the anterior midgut (117). In addition to metabolic deregulation, IMD pathway mutants are characterized by accelerated proliferation of intestinal progenitor cells, intestinal tissue dysplasia, and early death (34). Many of these phenotypes are reverted by elimination of the gut microbiome (124), confirming links between IMD, gut microbial composition, and intestinal health. As flies are highly amenable to modifications of intestinal gene activity, Drosophila has emerged as a particularly valuable tools to characterize links between host epithelial immunity, and V. cholerae pathogenesis.

In flies, reactive oxygen species generation does not appear to affect V. cholerae pathogenesis (139). In contrast, septic injury of adult flies with V. cholerae causes elevated expression of IMD-responsive antimicrobial peptides. Furthermore, induced expression of antimicrobial peptide genes attenuated V. cholerae pathogenesis in the septic injury model (111). These observations suggest that IMD will have protective effects against V. cholerae. However, characterization of flies challenged with V. cholerae through the natural, oral route, revealed an unexpected link between host immunity and pathogenesis. Specifically, although oral infection promotes the expression of IMD-responsive antimicrobial peptides in the intestine, IMD pathway mutants displayed an enhanced survival after oral infection with V. cholerae (140), indicating that host immune activity contributes to V. cholerae pathogenesis. Follow-up work showed that mutations in the IMD pathway have minimal effects on levels of intestinal V. cholerae (139). Nonetheless, whereas V. cholerae inhibit ISC growth in wild-type flies, ISC proliferation is unimpaired in the intestines of V. cholerae-infected IMD pathway mutants (139) suggesting that V. cholerae-dependent activation of IMD inhibits ISC proliferation, accelerating host death.

Studies of links between host immunity and V. cholerae pathogenesis uncovered an involvement of the Drosophila oxidation resistance 1 ortholog, mustard (mtd), in host viability (139, 141). Mustard is a Lysine Motif domain-bearing protein with roles in pupal eclosion (142). A gain-of-function mutant, mtdEY04695, that increases expression of a nuclear localized mustard isoform, significantly improves the survival duration of flies infected with V. cholerae (141). Molecular work showed that mtdEY04695 mutants process the IMD-responsive NF- κB transcription factor Relish normally, and express most antimicrobial peptides to wild type levels after infection (139, 141). However, genome-wide transcriptional studies uncovered broad overlaps between the expression profiles of mtdEY04695 and an IMD pathway mutant, including diminished expression of the diptericin antimicrobial peptide, suggesting interactions between mustard function and IMD activity. Similar to IMD pathway mutants, mtdEY04695 flies are capable of progenitor cell growth after infection, supporting the notion of links between immune activity, ISC proliferation, and host survival. Looking forward, it will be interesting to characterize the immune phenotypes of loss-of-function mutations in the mtd locus.

A recent study from our group examined the consequences of IMD inactivation in defined intestinal cell types for host viability after infection with V. cholerae (143). We found that inhibition of IMD in differentiated enterocytes significantly extended the survival times of infected flies, whereas inhibition of IMD in the progenitor cell compartment shortened survival times. These observations suggest that the activity of IMD in enterocytes is sufficient to enhance V. cholerae pathogenesis. The mechanism by which immune activity influences V. cholerae pathogenesis requires clarification. In this context, we note that IMD is required for the delamination of damaged cells in the intestinal epithelium (119). As V. cholerae causes extensive damage to the midgut epithelium (139, 140, 144), we consider it is possible that V. cholerae kills the host, in part, by activating IMD-dependent sloughing of the epithelium. In this untested model, excess delamination effectively disrupts the epithelial barrier, preventing the transduction of growth cues to progenitor cells, and leading to systemic infection and host death. However, we cannot exclude alternative, and potentially non-exclusive mechanistic links, such as metabolic dysfunction, between immune activity and host mortality. In particular, there is a considerable amount of data linking intestinal metabolism to disease progression in infected flies.

Vibrio cholerae and Host Metabolism

The gut microbiota modifies metabolism in Drosophila, with implications for host growth and development (40, 42, 145). For example, symbiotic Ap are a source of thiamine during development (146). Additionally, Ap-derived acetate stimulates insulin signaling activity in the fly (40). The Drosophila insulin response pathway is highly similar to the vertebrate counterpart (147), and Ap-dependent control of insulin activity affects key developmental processes such as intestinal growth, size regulation, and storage of energy (40). Similar to Ap, symbiotic Lactobacillus plantarum plays an important role in the regulation of larval growth. In this case, Lp activates intestinal peptidases, at least partially in an IMD-dependent manner (148), to promote the uptake of amino acids from the larval growth medium, thereby activating the Target of Rapamycin complex, and promoting larval growth (42). When considering microbial control of host metabolism, it is important to note that higher-order interactions in a complex community of intestinal bacteria impact host health and fitness (43). For example, interactions between symbiotic Acetobacter and Lactobacillus species influence lipid homeostasis in adult flies (149).

A genetic screen for V. cholerae mutants with impaired pathogenesis in flies identified the CrbRS two-component system as a modifier of host killing (150). CrbRS is composed of the CrbS histidine kinase sensor, and the CrbR response regulator. CrbRS controls expression of acetyl CoA-synthase (acs1), a bacterial regulator of acetate consumption. In E. coli, expression of acs1 activates the acetate switch, whereby bacteria switch from production to consumption of the short-chain fatty acid, acetate (151). The acetate switch is conserved in V. cholerae, as mutations in crbR, crbS, or acs1 prevent consumption of acetate by V. cholerae in liquid culture (150, 152). These observations suggest that V. cholerae-dependent virulence may involve consumption of intestinal acetate by the pathogen. Consistent with that hypothesis, provision of dietary acetate was sufficient to extend survival times in flies infected with V. cholerae. Mechanistically, the authors showed that consumption of intestinal acetate by wild-type V. cholerae disrupted insulin signaling in the host, leading to intestinal steatosis and depletion of lipid stores from the fly fat body, an insect organ with functional similarities to the vertebrate liver and white adipose tissue (153). Removal of lipids from the fly medium prevented steatosis, and extended host viability, confirming a role for lipid homeostasis in V. cholerae pathogenesis. Interestingly, CrbS is expressed during V. cholerae infections in mice and humans (154, 155), raising the possibility that pathogenic consumption of intestinal acetate is a general virulence strategy of V. cholerae.

Links between metabolism and pathogenesis extend beyond short-chain fatty acid consumption. For example, mutations of the V. cholerae glycine cleavage system also attenuate virulence in the fly model (156). These mutants colonize fly intestines with equal efficiency as wild-type V. cholerae, indicating that the phenotype is likely a consequence of an increased ability of the host to tolerate infection. In line with this hypothesis, glycine cleavage mutants fail to suppress ISC division, and do not affect lipid levels in fat tissue or homeostasis. Instead, glycine cleavage mutants have increased levels of methionine-sulfoxide in their intestines, and dietary supplementation with methionine-sulfoxide, or mutation of the host Methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA) gene extended host viability and restored lipid homeostasis to flies infected with V. cholerae, implicating methionine-sulfoxide availability in pathogenesis.

Metabolic regulation is also sensitive to quorum-sensing by V. cholerae. A recent study showed that quorum sensing in the El tor C6706 strain minimizes pathogenesis in flies, as deletion of the quorum-sensing master regulator, hapR, increased pathogenesis (157). HapR suppresses the expression of CT (158), and toxin co-regulated pilus virulence factors (159), and inhibits expression of Vibrio polysaccharide (160, 161), a biofilm exopolysaccharide that enables colonization of the Drosophila rectum (112). The elevated pathogenesis observed in ΔhapR strains was not the result of increased biofilm formation. Instead, the phenotype appears to be the consequence of increased succinate uptake by ΔhapR due to elevated expression of the Vibrio cholerae INDY succinate transporter. Consistent with this model, supplementation of the infection medium with succinate significantly extended survival times of flies infected with ΔhapR. Similar to phenotypes associated with methionine-sulfoxide, and acetate, succinate consumption by V. cholerae was associated with depletion of lipid stores from the fat body, suggesting a possible role for inter-organ regulation of lipid homeostasis in the survival of infection with V. cholerae.

Vibrio cholerae and ISC Growth

Much of the data above describe the phenotypic impacts of V. cholerae-mediated consumption of intestinal metabolites. However, it is important to remember that V. cholerae competes with gut-resident bacteria for attachment to the intestinal niche (162). Thus, V. cholerae-dependent displacement of intestinal bacteria can also affect the profile of metabolites available to the host. For example, V. cholerae encodes a type six secretion system (T6SS) that delivers an array of toxins to susceptible prokaryotic, and eukaryotic, prey (163–165). Two studies from our group implicated the T6SS in Drosophila pathogenesis mediated by the El Tor strain, C6706. The first study showed that the T6SS targets symbiotic Acetobacter pasteurianus for killing, and that the T6SS contributes to host killing (144). T6SS-dependent killing of the host requires the presence of Ap, and association of adult flies exclusively with T6SS-refractory Lactobacillus species is sufficient to extend the viability of C6706-infected hosts. These data indicate that T6SS-mediated killing of flies proceeds through an indirect route that requires host association with Acetobacter.

More recently, we showed that the T6SS also affects epithelial renewal in infected flies. In agreement with previous work (139), we showed that V. cholerae causes extensive damage to the midgut epithelium, but fails to activate compensatory proliferation in basal progenitor cells (166). Removal of the T6SS diminishes epithelial damage, and restores renewal in infected midguts. These effects are not the result of direct interactions between the T6SS and the host epithelium, as removal of the intestinal microbiome restores renewal capacity to midguts infected with C6706. Collectively, these data indicate that the T6SS contributes to V. cholerae-mediated inhibition of epithelial renewal in a manner that requires a gut microbiome. In these assays, inhibition of renewal is not a simple consequence of interactions between V. cholerae and symbiotic Acetobacter. Instead, inhibition of renewal required association of infected flies with a tripartite community of gut bacteria, consisting of Ap, Lactobacillus brevis, and Lp, suggesting that T6SS-dependent arrest of progenitor growth is the result of complex interactions between the pathogen and a community of symbionts. Interestingly, quorum sensing appears to be an important factor in progenitor renewal. In vertebrates, the master quorum sensor regulator, hapR is not expressed at early stages of infection, where V. cholerae are present in low density. The absence of HapR allows for production of the toxin coregulated pilus, and CT, resulting in disease. As V. cholerae numbers increase, quorum sensing-dependent production of HapR results in a repression of virulence genes. In our studies, we used a C6706 strain with low hapR expression (167), allowing for expression of virulence genes in the fly. In contrast, earlier studies with several C6706 strains that express hapR failed to arrest progenitor growth, and were not pathogenic to flies (157). Mutation of hapR in these strains restored pathogenesis, and blocked proliferation. In total, these studies hint at a sophisticated interplay between quorum sensing, bacterial competition, and epithelial renewal in the host. It will be interesting to determine the mechanistic basis for these interactions in future studies.

Conclusion and Future Direction

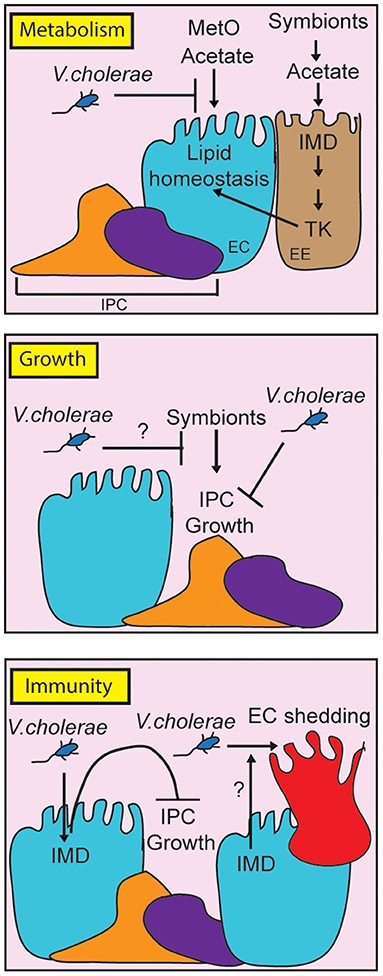

In this review, we have discussed the utility of D. melanogaster as an experimental model to understand V. cholerae pathogenesis. In the last 15 years, work with the fly uncovered a complex series of interactions between the invading pathogen, the intestinal microbiome, and host defense mechanisms (Figure 2). V. cholerae disrupts lipid metabolism in enterocytes, and in the fat body, suggesting impacts of the pathogen on communication between these critical regulators of lipid homeostasis. Host immune defenses contribute to pathogenesis, as IMD pathway mutants survive infections longer than their wild-type counterparts, and display an improved epithelial renewal response. It will be interesting to determine the mechanistic links between immune activity and epithelial renewal, and to determine how changes to lipid metabolism impact pathogenesis. We also consider it important to remember that growth, immunity, and metabolism share numerous regulatory components. The fly is a particularly valuable model to ask how these evolutionary conserved pathways interact to orchestrate systemic responses to a global health threat.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the impact of pathogenic Vibrio cholerae on metabolism, growth and immunity in the adult Drosophila midgut. For clarity, we have broken the individual responses into separate panels, although it is important to note that growth, metabolism and immunity share regulatory components in vivo. By consuming metabolites such as methionine sulfoxide (MetO) and acetate, V. cholerae affects lipid homeostasis contributing to death. At the same time, V. cholerae impairs IPC growth pathways, although it is unclear how this affects symbiont-dependent growth responses (indicated with a question mark). Finally, the host IMD pathway contributes to pathogenesis by impairing IPC growth, and possibly by affecting epithelial turnover (indicated by a question mark).

Author Contributions

SD and EF wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to EF (MOP77746).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:341–52. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42

2. Levy M, Blacher E, Elinav E. Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol. (2017) 35:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.10.003

3. Lee WJ, Hase K. Gut microbiota-generated metabolites in animal health and disease. Nat Chem Biol. (2014) 10:416–24. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1535

4. Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:16767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105

5. Robertson RC, Manges AR, Finlay BB, Prendergast AJ. The human microbiome and child growth – first 1000 days and beyond. Trends Microbiol. (2019) 27:131–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.09.008

6. Yamamoto M, Yamaguchi R, Munakata K, Takashima K, Nishiyama M, Hioki K, et al. A microarray analysis of gnotobiotic mice indicating that microbial exposure during the neonatal period plays an essential role in immune system development. BMC Genomics. (2012) 13:335. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-335

7. Lu J, Synowiec S, Lu L, Yu Y, Bretherick T, Takada S, et al. Microbiota influence the development of the brain and behaviors in C57BL/6J mice. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e201829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201829

8. Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, Saeedi B, Scholz CC, Bayless AJ, et al. Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:662–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.005

9. Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, et al. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe. (2007) 2:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.010

10. Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, et al. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn's disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. (2006) 55:205–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.073817

11. Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Rivera-Chávez F, Tiffany CR, Cevallos SA, Lokken KL, et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-γ signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science. (2017) 357:570–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9949

12. Swidsinski A, Loening-Baucke V, Lochs H, Hale LP. Spatial organization of bacterial flora in normal and inflamed intestine: a fluorescence in situ hybridization study in mice. World J Gastroenterol. (2005) 11:1131–40. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i8.1131

13. Coker OO, Dai Z, Nie Y, Zhao G, Cao L, Nakatsu G, et al. Mucosal microbiome dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut. (2018) 67:1024–32. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314281

14. Pacheco AR, Curtis MM, Ritchie JM, Munera D, Waldor MK, Moreira CG, et al. Fucose sensing regulates bacterial intestinal colonization. Nature. (2012) 492:113–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11623

15. Adair KL, Douglas AE. Making a microbiome: the many determinants of host-associated microbial community composition. Curr Opin Microbiol. (2017) 35:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.11.002

16. Wong CNA, Ng P, Douglas AE. Low-diversity bacterial community in the gut of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. (2011) 13:1889–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02511.x

17. Broderick NA, Lemaitre B. Gut-associated microbes ofDrosophila melanogaster. Gut Microbes. (2012) 3:19896. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19896

18. Douglas AE. The Drosophila model for microbiome research. Lab Anim. (2018) 47:157–64. doi: 10.1038/s41684-018-0065-0

19. Douglas AE. Simple animal models for microbiome research. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2019) 17:764–75. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0242-1

20. Miguel-Aliaga I, Jasper H, Lemaitre B. Anatomy and physiology of the digestive tract ofDrosophila melanogaster. Genetics. (2018) 210:357–96. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.300224

21. Jiang H, Edgar BA. Intestinal stem cell function in Drosophila and mice. Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2012) 22:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.04.002

22. Ferrandon D. The complementary facets of epithelial host defenses in the genetic model organism Drosophila melanogaster: from resistance to resilience. Curr Opin Immunol. (2013) 25:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.11.008

23. Buchon N, Broderick NA, Lemaitre B. Gut homeostasis in a microbial world: insights from Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2013) 11:615–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3074

24. Kuraishi T, Binggeli O, Opota O, Buchon N, Lemaitre B. Genetic evidence for a protective role of the peritrophic matrix against intestinal bacterial infection inDrosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:15966–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105994108

25. Myllymaki H, Valanne S, Ramet M, Myllymäki H, Valanne S, Rämet M. The Drosophila Imd signaling pathway. J Immunol. (2014) 192:3455–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303309

26. Bosco-Drayon V, Poidevin M, Boneca IG, Narbonne-Reveau K, Royet J, Charroux B. Peptidoglycan sensing by the receptor PGRP-LE in the Drosophila gut induces immune responses to infectious bacteria and tolerance to microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. (2012) 12:153–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.002

27. Kaneko T, Yano T, Aggarwal K, Lim J-H, Ueda K, Oshima Y, et al. PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE have essential yet distinct functions in the Drosophila immune response to monomeric DAP-type peptidoglycan. Nat Immunol. (2006) 7:715–23. doi: 10.1038/ni1356

28. Neyen C, Poidevin M, Roussel A, Lemaitre B. Tissue- and ligand-specific sensing of gram-negative infection in Drosophila by PGRP-LC isoforms and PGRP-LE. J Immunol. (2012) 189:1886–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201022

29. Hanson MA, Dostálová A, Ceroni C, Poidevin M, Kondo S, Lemaitre B. Synergy and remarkable specificity of antimicrobial peptides in vivo using a systematic knockout approach. Elife. (2019) 8:44341. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44341

30. Ha E-M, Oh C-T, Bae YS, Lee W-J. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science. (2005) 310:847–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1117311

31. Lee KA, Cho KC, Kim B, Jang IH, Nam K, Kwon YE, et al. Inflammation-modulated metabolic reprogramming is required for DUOX-dependent gut immunity in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe. (2018) 23:338–52.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.011

32. Jiang H, Grenley MO, Bravo MJ, Blumhagen RZ, Edgar BA. EGFR/Ras/MAPK signaling mediates adult midgut epithelial homeostasis and regeneration in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. (2011) 8:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.026

33. Jiang H, Patel PH, Kohlmaier A, Grenley MO, McEwen DG, Edgar BA. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. (2009) 137:1343–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014

34. Buchon N, Broderick NA, Poidevin M, Pradervand S, Lemaitre B. Drosophila intestinal response to bacterial infection: activation of host defense and stem cell proliferation. Cell Host Microbe. (2009) 5:200–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.003

35. Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. (2009) 4:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.016

36. Blum JE, Fischer CN, Miles J, Handelsman J. Frequent replenishment sustains the beneficial microbiome of Drosophila melanogaster. MBio. (2013) 4:e00860–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00860-13

37. Wong ACN, Vanhove AS, Watnick PI. The interplay between intestinal bacteria and host metabolism in health and disease: lessons fromDrosophila melanogaster. DMM Dis Model Mech. (2016) 9:271–81. doi: 10.1242/dmm.023408

38. Lee W-J, Brey PT. How microbiomes influence metazoan development:insights from history and Drosophila modeling of gut-microbe interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. (2013) 29:571–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122333

39. Capo F, Wilson A, Di Cara F. The intestine of Drosophila melanogaster: an emerging versatile model system to study intestinal epithelial homeostasis and host-microbial interactions in humans. Microorganisms. (2019) 7:336. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090336

40. Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, Kim B, Kim AC, Lee KA, et al. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. (2011) 334:670–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1212782

41. Téfit MA, Leulier F. Lactobacillus plantarum favors the early emergence of fit and fertile adult Drosophila upon chronic undernutrition. J Exp Biol. (2017) 220:900–7. doi: 10.1242/jeb.151522

42. Storelli G, Defaye A, Erkosar B, Hols P, Royet J, Leulier FF. Lactobacillus plantarum promotes Drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab. (2011) 14:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.012

43. Gould AL, Zhang V, Lamberti L, Jones EW, Obadia B, Korasidis N, et al. Microbiome interactions shape host fitness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:E11951–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809349115

44. Pais IS, Valente RS, Sporniak M, Teixeira L. Drosophila melanogaster establishes a species-specific mutualistic interaction with stable gut-colonizing bacteria. PLoS Biol. (2018) 16:e2005710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005710

45. Wong AC-N, Dobson AJ, Douglas AE. Gut microbiota dictates the metabolic response of Drosophila to diet. J Exp Biol. (2014) 217:1894–901. doi: 10.1242/jeb.101725

46. Sommer AJ, Newell PD. Metabolic basis for mutualism between gut bacteria and its impact on the Drosophila melanogaster host. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2019) 85:e01882–18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01882-18

47. Kuraishi T, Hori A, Kurata S. Host-microbe interactions in the gut ofDrosophila melanogaster. Front Physiol. (2013) 4:375. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00375

48. Blow NS, Salomon RN, Garrity K, Reveillaud I, Kopin A, Jackson FR, et al. Vibrio cholerae infection of Drosophila melanogaster mimics the human disease cholera. PLoS Pathog. (2005) 1:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010008

49. Oliver JD, Jones JL. Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus. In: Molecular Medical Microbiology: Second Edition. Elsevier Ltd. p.1169–86. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397169-2.00066-4

50. Broza M, Halpern M. Chironomid egg masses and Vibrio cholerae. Nature. (2001) 412:40. doi: 10.1038/35083691

51. Colwell R, Huq A. Marine ecosystems and cholera. Hydrobiologia. (2001) 460:141–5. doi: 10.1023/A:1013111016642

52. Legros D. Global cholera epidemiology: opportunities to reduce the burden of cholera by 2030. J Infect Dis. (2018) 218:S137–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy486

53. Deen J, Mengel MA, Clemens JD. Epidemiology of cholera. Vaccine. (2019). doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.078. [Epub ahead of print].

54. Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Qadri F, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB. Cholera. Lancet. (2012) 379:2466–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X

55. Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2015) 9:3832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832

56. Morona R, Manning PA, Stroeher UH. Molecular basis for O-antigen biosynthesis in Vibrio cholerae O1: ogawa-inaba switching. In: Vibrio cholerae and Cholera. American Society of Microbiology (1994), p.77–94.

57. Karaolis DK, Lan R, Reeves PR. The sixth and seventh cholera pandemics are due to independent clones separately derived from environmental, nontoxigenic, non-O1 Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. (1995) 177:3191–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3191-3198.1995

58. Olivier V, Haines GK, Tan Y, Fullner Satchell KJ. Hemolysin and the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin are virulence factors during intestinal infection of mice with Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 strains. Infect Immun. (2007) 75:5035–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00506-07

59. Mitra R, Figueroa P, Mukhopadhyay AK, Shimada T, Takeda Y, Berg DE, et al. Cell vacuolation, a manifestation of the El Tor hemolysin of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. (2000) 68:1928–33. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.4.1928-1933.2000

60. Son MS, Megli CJ, Kovacikova G, Qadri F, Taylor RK. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 El tor biotype variant clinical isolates from Bangladesh and Haiti, including a molecular genetic analysis of virulence genes. J Clin Microbiol. (2011) 49:3739–49. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01286-11

61. Pradhan S, Baidya AK, Ghosh A, Paul K, Chowdhury R. The El tor biotype of Vibrio cholerae exhibits a growth advantage in the stationary phase in mixed cultures with the classical biotype. J Bacteriol. (2010) 192:955–63. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-09

62. Calia KE, Murtagh M, Ferraro MJ, Calderwood SB. Comparison of Vibrio cholerae O139 with V. cholerae O1 classical and El Tor biotypes. Infect Immun. (1994) 62:1504–6.

63. Hu D, Liu B, Feng L, Ding P, Guo X, Wang M, et al. Origins of the current seventh cholera pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:E7730–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608732113

64. Woodward WE, Mosley WH. The spectrum of cholera in rural Bangladesh. II. Comparison of El Tor Ogawa and classical Inaba infection. Am J Epidemiol. (1972) 96:342–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121465

65. Bart KJ, Huq Z, Khan M, Mosley WH. Seroepidemiologic studies during a simultaneous epidemic of infection with El Tor Ogawa and classical Inaba Vibrio cholerae. J Infect Dis. (1970) 121(Suppl 121):17. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.supplement.s17

66. Matson JS, Withey JH, DiRita VJ. Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect Immun. (2007) 75:5542–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01094-07

67. Karaolis DKR, Johnson JA, Bailey CC, Boedeker EC, Kaper JB, Reeves PR. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1998) 95:3134–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3134

68. Tacket CO, Taylor RK, Losonsky G, Lim Y, Nataro JP, Kaper JB, et al. Investigation of the roles of toxin-coregulated pili and mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin pili in the pathogenesis of Vibrio cholerae O139 infection. Infect Immun. (1998) 66:692–5.

69. Herrington DA, Hall RH, Losonsky G, Mekalanos JJ, Taylor RK, Levine MM. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J Exp Med. (1988) 168:1487–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487

70. Yamamoto S, Takeda Y, Yamamoto M, Kurazono H, Imaoka K, Yamamoto M, et al. Mutants in the ADP-ribosyltransferase cleft of cholera toxin lack diarrheagenicity but retain adjuvanticity. J Exp Med. (1997) 185:1203–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1203

71. Moss J, Stanley SJ, Vaughan M, Tsuji T. Interaction of ADP-ribosylation factor with Escherichia coli enterotoxin that contains an inactivating lysine 112 substitution. J Biol Chem. (1993) 268:6383–7.

72. Sikora AE. Proteins secreted via the type II secretion system: smart strategies of Vibrio cholerae to maintain fitness in different ecological niches. PLoS Pathog. (2013) 9:e1003126. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003126

73. Jobling MG, Yang Z, Kam WR, Lencer WI, Holmes RK. A single native ganglioside GM1-binding site is sufficient for cholera toxin to bind to cells and complete the intoxication pathway. MBio. (2012) 3:e00401–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00401-12

74. Kassis S, Hagmann J, Fishman PH, Chang PP, Moss J. Mechanism of action of cholera toxin on intact cells. Generation of A1 peptide and activation of adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem. (1982) 257:12148–52.

75. Cassel D, Selinger Z. Mechanism of adenylate cyclase activation by cholera toxin: inhibition of GTP hydrolysis at the regulatory site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1977) 74:3307–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3307

76. Schafer DE, Lust WD, Sircar B, Goldberg ND. Elevated concentration of adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate in intestinal mucosa after treatment with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1970) 67:851–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.2.851

77. Cheng SH, Rich DP, Marshall J, Gregory RJ, Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Phosphorylation of the R domain by cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates the CFTR chloride channel. Cell. (1991) 66:1027–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90446-6

78. Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Faruque ASG, Ryan ET. Severe, acute watery diarrhea in an adult. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2010) 4:e898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000898

79. Klose KE. Regulation of virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Int J Med Microbiol. (2001) 291:81–8. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00104

80. Craig L, Pique ME, Tainer JA. Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2004) 2:363–78. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro885

81. Reguera G, Kolter R. Virulence and the environment: a novel role for Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pili in biofilm formation on chitin. J Bacteriol. (2005) 187:3551–5. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3551-3555.2005

82. Glass RI, Huq I, Alim ARMA, Yunus M. Emergence of multiply antibiotic-resistant Vibrio cholerae in Bangladesh. J Infect Dis. (1980) 142:939–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.6.939

83. Weill F-X, Domman D, Njamkepo E, Tarr C, Rauzier J, Fawal N, et al. Genomic history of the seventh pandemic of cholera in Africa. Science. (2017) 358:785–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5901

84. Ritchie JM, Waldor MK. Vibrio cholerae Interactions with the gastrointestinal tract: lessons from animal studies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. (2009) 337:37–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-01846-6_2

85. Spira WM, Sack RB, Froehlich JL. Simple adult rabbit model for Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea. Infect Immun. (1981) 32:739–47.

86. Abel S, Waldor MK. Infant rabbit model for diarrheal diseases. Curr Protoc Microbiol. (2015) 2015:6A.6.1–6.15. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc06a06s38

87. Ritchie JM, Rui H, Bronson RT, Waldor MK. Back to the future: studying cholera pathogenesis using infant Rabbits. MBio. (2010) 1:e00047–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00047-10

88. DE SN. Enterotoxicity of bacteria-free culture-filtrate of Vibrio cholerae. Nature. (1959) 183:1533–4. doi: 10.1038/1831533a0

89. Schrank GD, Verwey WF. Distribution of cholera organisms in experimental Vibrio cholerae infections: proposed mechanisms of pathogenesis and antibacterial immunity. Infect Immun. (1976) 13:195–203.

90. Nelson ET, Clements JD, Finkelstein RA. Vibrio cholerae adherence and colonization in experimental cholera: electron microscopic studies. Infect Immun. (1976) 14:527–47.

91. Rui H, Ritchie JM, Bronson RT, Mekalanos JJ, Zhang Y, Waldor MK. Reactogenicity of live-attenuated Vibrio cholerae vaccines is dependent on flagellins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:4359–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915164107

92. Klose KE. The suckling mouse model of cholera. Trends Microbiol. (2000) 8:189–91. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01721-2

93. Taylor RK, Miller VL, Furlong DB, Mekalanos JJ. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1987) 84:2833–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2833

94. Olivier V, Salzman NH, Satchell KJF. Prolonged colonization of mice by Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 depends on accessory toxins. Infect Immun. (2007) 75:5043–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00508-07

95. Klose KE. The suckling mouse model of cholera. Trends Microbiol. (2000) 8:189–91. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01721-2

96. Matson JS. Infant Mouse Model of Vibrio cholerae Infection and Colonization. Humana Press Inc (2018). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8685-9_13

97. Richardson SH. Animal models in cholera research. In: Vibrio cholerae and Cholera. American Society of Microbiology (1994), p. 203–26. doi: 10.1128/9781555818364.ch14

98. Olivier V, Queen J, Satchell KJF. Successful small intestine colonization of adult mice by Vibrio cholerae requires ketamine anesthesia and accessory toxins. PLoS ONE. (2009) 4:e7352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007352

99. Butterton JR, Ryan ET, Shahin RA, Calderwood SB. Development of a germfree mouse model of Vibrio cholerae infection. Infect Immun. (1996) 64:4373–7.

100. Sawasvirojwong S, Srimanote P, Chatsudthipong V, Muanprasat C. An adult mouse model of Vibrio cholerae-induced diarrhea for studying pathogenesis and potential therapy of cholera. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2013) 7:e2293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002293

101. Senderovich Y, Izhaki I, Halpern M. Fish as reservoirs and vectors of Vibrio cholerae. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e8607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008607

102. Acosta CJ, Galindo CM, Kimario J, Senkoro K, Urassa H, Casals C, et al. Cholera outbreak in southern Tanzania: risk factors and patterns of transmission. Emerg Infect Dis. (2001) 7:583–7. doi: 10.3201/eid0707.010741

103. Mitchell KC, Withey JH. Danio rerio as a native host model for understanding pathophysiology of Vibrio cholerae. Methods Mol Biol. (2018) 1839:97–102. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8685-9_9

104. Runft DL, Mitchell KC, Abuaita BH, Allen JP, Bajer S, Ginsburg K, et al. Zebrafish as a natural host model for Vibrio cholerae colonization and transmission. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2014) 80:1710–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03580-13

105. Stephens WZ, Burns AR, Stagaman K, Wong S, Rawls JF, Guillemin K, et al. The composition of the zebrafish intestinal microbial community varies across development. ISME J. (2016) 10:644–54. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.140

106. Logan SL, Thomas J, Yan J, Baker RP, Shields DS, Xavier JB, et al. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system can modulate host intestinal mechanics to displace gut bacterial symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:E3779–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720133115

107. Halpern M, Broza YB, Mittler S, Arakawa E, Broza M. Chironomid egg masses as a natural reservoir of Vibrio cholerae non-O1 and non-O139 in freshwater habitats. Microb Ecol. (2004) 47:341–9. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-2007-6

108. Echeverria P, Harrison BA, Tirapat C, McFarland A. Flies as a source of enteric pathogens in a rural village in Thailand. Appl Environ Microbiol. (1983) 46:32–6.

109. Fotedar R. Vector potential of houseflies. (Musca domestica) in the transmission of Vibrio cholerae in India. Acta Trop. (2001) 78:31–4. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00162-5

110. Neyen C, Bretscher AJ, Binggeli O, Lemaitre B. Methods to study Drosophila immunity. Methods. (2014) 68:116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.023

111. Park SY, Heo YJ, Kim KS, Cho YH. Drosophila melanogaster is susceptible to Vibrio cholerae infection. Mol Cells. (2005) 20:409–15.

112. Purdy AE, Watnick PI. Spatially selective colonization of the arthropod intestine through activation of Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:19737–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111530108

113. Watnick PI, Lauriano CM, Klose KE, Croal L, Kolter R. The absence of a flagellum leads to altered colony morphology, biofilm development and virulence in Vibrio cholerae O139. Mol Microbiol. (2001) 39:223–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02195.x

114. Guo L, Karpac J, Tran SL, Jasper H. PGRP-SC2 promotes gut immune homeostasis to limit commensal dysbiosis and extend lifespan. Cell. (2014) 156:109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.018

115. Molaei M, Vandehoef C, Karpac J. NF-κB shapes metabolic adaptation by attenuating foxo-mediated lipolysis in Drosophila. Dev Cell. (2019) 49:802–10.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.009

116. Paredes JC, Welchman DP, Poidevin M, Lemaitre B. Negative regulation by Amidase PGRPs shapes the Drosophila antibacterial response and protects the Fly from innocuous infection. Immunity. (2011) 35:770–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.018

117. Kamareddine L, Robins WP, Berkey CD, Mekalanos JJ, Watnick PI, et al. The Drosophila immune deficiency pathway modulates enteroendocrine function and host metabolism. Cell Metab. (2018) 28:449–62.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.026

118. Ryu JH, Ha EM, Oh CT, Seol JH, Brey PT, Jin I, et al. An essential complementary role of NF-κB pathway to microbicidal oxidants in Drosophila gut immunity. EMBO J. (2006) 25:3693–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601233

119. Zhai Z, Boquete J-P, Lemaitre B. Cell-specific Imd-NF-κB responses enable simultaneous antibacterial immunity and intestinal epithelial cell shedding upon bacterial infection. Immunity. (2018) 48:897–910.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.010

120. Davoodi S, Galenza A, Panteluk A, Deshpande R, Ferguson M, Grewal S, et al. The immune deficiency pathway regulates metabolic homeostasis in Drosophila. J Immunol. (2019) 202:2747–59. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801632

121. Petkau K, Ferguson M, Guntermann S, Foley E. Constitutive immune activity promotes tumorigenesis in Drosophila intestinal progenitor cells. Cell Rep. (2017) 20:1784–93. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.078

122. Liehl P, Blight M, Vodovar N, Boccard F, Lemaitre B. Prevalence of local immune response against oral infection in a Drosophila/Pseudomonas infection model. PLoS Pathog. (2006) 2:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020056

123. Broderick NA, Buchon N, Lemaitre B. Microbiota-induced changes in Drosophila melanogaster host gene expression and gut morphology. MBio. (2014) 5:e01117–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01117-14

124. Buchon N, Broderick NA, Chakrabarti S, Lemaitre B. Invasive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. (2009) 23:2333–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.1827009

125. Ryu J-HH, Kim S-HH, Lee H-YY, Bai JY, Nam Y-D Do, Bae J-WW, et al. Innate immune homeostasis by the homeobox gene Caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science. (2008) 319:777–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1149357

126. Clark RI, Salazar A, Yamada R, Fitz-Gibbon S, Morselli M, Alcaraz J, et al. Distinct shifts in microbiota composition during Drosophila aging impair intestinal function and drive mortality. Cell Rep. (2015) 12:1656–67. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.004

127. Ferguson M, Petkau K, Shin M, Galenza A, Fast D, Foley E. Symbiotic Lactobacillus brevis promote stem cell expansion and tumorigenesis in the Drosophila intestine. bioRxiv. (2019) 2019:799981. doi: 10.1101/799981

128. Evans EA, Chen WC, Tan M-WW. The DAF-2 insulin-like signaling pathway independently regulates aging and immunity in C. elegans. Aging Cell. (2008) 7:879–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00435.x

129. Tsai S, Clemente-Casares X, Zhou AC, Lei H, Ahn JJ, Chan YT, et al. Insulin receptor-mediated stimulation boosts T cell immunity during inflammation and infection. Cell Metab. (2018) 28:922–34.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.003

130. Ventre J, Doebber T, Wu M, MacNaul K, Stevens K, Pasparakis M, et al. Targeted disruption of the tumor necrosis factor-gene: metabolic consequences in obese and nonobese mice. Diabetes. (1997) 46:1526–31. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.9.1526

131. Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF- α function. Nature. (1997) 389:610–4. doi: 10.1038/39335

132. Evans EA, Kawli T, Tan M-WW. Pseudomonas aeruginosa suppresses host immunity by activating the DAF-2 insulin-like signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. (2008) 4:e1000175. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000175

133. Dionne MS, Pham LN, Shirasu-Hiza M, Schneider DS. Akt and foxo dysregulation contribute to infection-induced wasting in Drosophila. Curr Biol. (2006) 16:1977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.052

134. Karpac J, Younger A, Jasper H. Dynamic coordination of innate immune signaling and insulin signaling regulates systemic responses to localized DNA damage. Dev Cell. (2011) 20:841–54. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.011

135. Roth SW, Bitterman MD, Birnbaum MJ, Bland ML. Innate immune signaling in Drosophila blocks insulin signaling by uncoupling PI(3,4,5)P 3 production and Akt activation. Cell Rep. (2018) 22:2550–6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.033

136. McCormack S, Yadav S, Shokal U, Kenney E, Cooper D, Eleftherianos I. The insulin receptor substrate Chico regulates antibacterial immune function in Drosophila. Immun Ageing. (2016) 13:15. doi: 10.1186/s12979-016-0072-1

137. Fink C, Hoffmann J, Knop M, Li Y, Isermann K, Roeder T. Intestinal FoxO signaling is required to survive oral infection in Drosophila. Mucosal Immunol. (2016) 9:927–36. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.112

138. Libert S, Chao Y, Zwiener J, Pletcher SD. Realized immune response is enhanced in long-lived puc and chico mutants but is unaffected by dietary restriction. Mol Immunol. (2008) 45:810–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.353

139. Wang Z, Hang S, Purdy AE, Watnick PI. Mutations in the IMD pathway and mustard counter Vibrio cholerae suppression of intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. MBio. (2013) 4:e00337–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00337-13

140. Berkey CD, Blow N, Watnick PI. Genetic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster susceptibility to intestinal Vibrio cholerae infection. Cell Microbiol. (2009) 11:461–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01267.x

141. Wang Z, Berkey CD, Watnick PI. The Drosophila protein mustard tailors the innate immune response activated by the immune deficiency pathway. J Immunol. (2012) 188:3993–4000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103301

142. Stowers RS, Russell S, Garza D. The 82F late puff contains the L82 gene, an essential member of a novel gene family. Dev Biol. (1999) 213:116–30. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9358

143. Shin M, Jones LO, Petkau K, Panteluk A, Foley E. Cell-specific regulation of intestinal immunity in Drosophila. bioRxiv. (2019) 2019:721662. doi: 10.1101/721662

144. Fast D, Kostiuk B, Foley E, Pukatzki S. Commensal pathogen competition impacts host viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:7099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802165115

145. Ridley EV, Wong AC-N, Westmiller S, Douglas AE. Impact of the resident microbiota on the nutritional phenotype ofDrosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e36765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036765

146. Sannino DR, Dobson AJ, Edwards K, Angert ER, Buchon N. The Drosophila melanogaster gut microbiota provisions thiamine to its host. MBio. (2018) 9:e00155–18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00155-18

147. Nässel DR, Liu Y, Luo J. Insulin/IGF signaling and its regulation in Drosophila. Gen Comp Endocrinol. (2015) 221:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.11.021

148. Fast D, Duggal A, Foley E. Monoassociation with Lactobacillus plantarum disrupts intestinal homeostasis in adultDrosophila melanogaster. MBio. (2018) 9:e01114–18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01114-18

149. Newell PD, Douglas AE. Interspecies interactions determine the impact of the gut microbiota on nutrient allocation inDrosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2014) 80:788–96. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02742-13

150. Hang S, Purdy AEE, Robins WPP, Wang Z, Mandal M, Chang S, et al. The acetate switch of an intestinal pathogen disrupts host insulin signaling and lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe. (2014) 16:592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.006

151. Wolfe AJ. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. (2005) 69:12–50. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.69.1.12-50.2005

152. Muzhingi I, Prado C, Sylla M, Diehl FF, Nguyen DK, Servos MM, et al. Modulation of CrbS-dependent activation of the acetate switch in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. (2018) 200. doi: 10.1128/JB.00380-18

153. Yongmei Xi YZ, Xi Y. Fat body development and its function in energy storage and nutrient sensing inDrosophila melanogaster. J Tissue Sci Eng. (2015) 6:1–8. doi: 10.4172/2157-7552.1000141

154. Lombardo M-J, Michalski J, Martinez-Wilson H, Morin C, Hilton T, Osorio CG, et al. An in vivo expression technology screen for Vibrio cholerae genes expressed in human volunteers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:18229–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705636104

155. Osorio CG, Crawford JA, Michalski J, Martinez-Wilson H, Kaper JB, Camilli A. Second-generation recombination-based in vivo expression technology for large-scale screening for Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection of the mouse small intestine. Infect Immun. (2005) 73:972–80. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.972-980.2005

156. Vanhove AS, Hang S, Vijayakumar V, Wong ACN, Asara JM, Watnick PI. Vibrio cholerae ensures function of host proteins required for virulence through consumption of luminal methionine sulfoxide. PLoS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006428. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006428

157. Kamareddine L, Wong ACNN, Vanhove AS, Hang S, Purdy AE, Kierek-Pearson K, et al. Activation of Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing promotes survival of an arthropod host. Nat Microbiol. (2018) 3:243–52. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0065-7

158. Zhu J, Miller MB, Vance RE, Dziejman M, Bassler BL, Mekalanos JJ. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2002) 99:3129–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052694299

159. Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. Regulation of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by quorum sensing: HapR functions at the aphA promoter. Mol Microbiol. (2002) 46:1135–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03229.x

160. Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. (2003) 50:101–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x

161. Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev Cell. (2003) 5:647–56. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00295-8

162. Zhao W, Caro F, Robins W, Mekalanos JJ. Antagonism toward the intestinal microbiota and its effect on Vibrio cholerae virulence. Science. (2018) 359:210–3. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8775

163. Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:15508–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104

164. Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, et al. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2006) 103:1528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103

165. Ho BT, Fu Y, Dong TG, Mekalanos JJ. Vibrio cholerae type 6 secretion system effector trafficking in target bacterial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:9427–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711219114

166. Fast D, Petkau K, Ferguson M, Shin M, Galenza A, Kostiuk B, et al. Complex symbiont-pathogen interactions inhibit intestinal repair. bioRxiv. (2019) 2019:746305. doi: 10.1101/746305

Keywords: IMD, Drosophila melanogaster, proliferation, Vibrio cholerae, insulin, microbiome, metabolism, T6SS

Citation: Davoodi S and Foley E (2020) Host-Microbe-Pathogen Interactions: A Review of Vibrio cholerae Pathogenesis in Drosophila. Front. Immunol. 10:3128. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03128

Received: 31 October 2019; Accepted: 23 December 2019;

Published: 24 January 2020.

Edited by:

Susanna Valanne, Tampere University, FinlandReviewed by:

Shoichiro Kurata, Tohoku University, JapanIoannis Eleftherianos, George Washington University, United States

Bruno Lemaitre, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland

Copyright © 2020 Davoodi and Foley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Edan Foley, ZWZvbGV5QHVhbGJlcnRhLmNh

Saeideh Davoodi

Saeideh Davoodi Edan Foley

Edan Foley