- 1Department of Pedagogy, Aleksander Moisiu University, Durrës, Albania

- 2Department of English, Aleksander Moisiu University, Durrës, Albania

Principals plays a decisive role in shaping school culture. First, based on teachers’ perceptions, this research explores indicators that differentiate schools with a positive culture from those with a negative culture. Second, it investigates potential perceptual differences between teachers and principals regarding school culture. The research approach is a grounded theory, utilizing unstructured interviews with principals, semi-structured interviews with school teachers, and observations conducted over a two-month period. The study population includes teachers and principals from eight secondary schools. From this population, the study sample consists of 12 principals and 137 teachers. The study findings evidenced that schools with a positive culture stand out for fostering a culture of cooperation among staff, celebrating school achievements, and collaborating in groups to develop curricular plans and programs. Furthermore, schools with a positive culture maintain strong connections with the community through participation in local ceremonies and adherence to community customs. The study concludes that the actions taken by leaders are closely associated with changes in school culture over time. Schools characterized by a positive culture cultivate a benevolent and productive environment, fostering satisfaction among staff. In contrast, schools with a negative culture often exhibit manifestations such as indifference, fragmentation, interpersonal conflicts, and a lack of job satisfaction.

Introduction

Culture plays a fundamental role in shaping the life of a school, providing the foundation for the shared history, beliefs, and values among staff, students, and the broader community. It is visible through external indicators, such as the school’s climate, environment, behaviors, rules, and uniforms. However, the deeper elements of school culture—such as heroes, rituals, stories, values, language, assumptions, and norms—are less visible yet crucial in defining the character of the institution (Peterson and Deal, 2009; Schein, 2004; Weick and Sutcliffe, 2007).

The relationship between leadership and school culture is central to both internal development and the broader influence of the school on its community. As Bush (2021) highlights, leadership and culture are intertwined and can vary significantly depending on the social and cultural context. Leadership practices are influenced by social norms, which in turn, shape how leadership is enacted within schools. For instance, hierarchical leadership structures in countries like China and Saudi Arabia contrast sharply with more collaborative and inclusive approaches in countries like the USA and Finland. This diversity in leadership practices underscores the importance of cultural responsiveness in school leadership, particularly in fostering an inclusive and effective school culture.

In this context, this study adopts grounded theory as its research methodology, applying a combination of Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory (2006) and Corbin and Strauss’s grounded theory approach (2014), which allows for a deeper understanding of the less visible aspects and indicators of school leadership. Grounded theory has become increasingly prominent in qualitative research, particularly in management and education, as a way to uncover patterns and dynamics that are often overlooked. Scholars like Maharani (2021), Makri and Neely (2021), and Stough and Lee (2021) have explored the evolution and application of grounded theory, highlighting its flexibility and adaptability across different research contexts. Maharani (2021) compares two approaches to data analysis within grounded theory: Glaser’s flexible, researcher-led method and Strauss’s more structured process. Makri and Neely (2021) note that while grounded theory is widely used, its application in management studies remains underexplored. Meanwhile, Stough and Lee (2021) emphasize its growing use in educational research, particularly with the rise of alternative approaches, such as Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory, which can be tailored to various research settings (Apramian et al., 2016).

This research aims to address key issues in school culture and leadership. Specifically, the study has two main objectives: first, to identify the indicators that distinguish schools with positive cultures from those with negative cultures; and second, to examine possible perceptual differences between teachers and principals regarding the culture of their schools. These objectives will guide the investigation into the complexities of school culture and the pivotal role leadership plays in shaping and sustaining it.

Conceptual framework/theory

The landscape of educational leadership is shaped by the interplay between principals, teachers, and the broader school culture. Research has increasingly focused on how these elements contribute to school effectiveness, accountability, and student achievement. The role of school culture in shaping educational environments is crucial for fostering effective learning and collaboration among students and staff. According to Peterson and Deal (2009), school culture consists of unwritten rules, symbols, traditions, and shared language that create an “underground river” of values and norms, which profoundly influence daily interactions and experiences within the school. Schein (2004) emphasizes that culture is built upon shared assumptions, beliefs, and values that define an organization’s identity and goals. Dongjiao (2022) defines it as the system culture of a school, referring to the organizational structure, rules, regulations, and management culture that are shaped through the implementation of the school’s spiritual culture. This system culture determines which actions should be encouraged, helps disseminate the school’s value system, and regulates the behavior of teachers, students, and staff.

Schein identifies three levels of culture: visible artifacts, espoused beliefs and values, and unconscious underlying assumptions, emphasizing that leaders must understand these deeper cultural layers to lead effectively. Aspin (2005) defines values as shared standards of behavior, while beliefs are deeply held cognitive views about truth and identity, which are difficult to change. Peterson and Deal (2009) suggest that in schools, values guide decision-making, while beliefs shape attitudes towards teaching and learning, both of which can be resistant to change. Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) describe an “informed culture” as one that aligns with a community’s values and beliefs, fostering reflection and thoughtful decision-making.

The studies by Chiang et al. (2016), Harris (2009), and Jabonillo (2022) offer diverse perspectives on the relationship between leadership, school effectiveness, and the roles of principals. Harris (2009) emphasizes the importance of evaluating teacher contributions to educational policies and student achievement, arguing that teacher involvement in decision making is crucial for school success. In contrast, Chiang et al. (2016) question the utility of school effectiveness as a metric for assessing principal performance, highlighting that school value-added models do not reliably predict principal value-added. Similarly, Jabonillo (2022) explores the connection between leadership and school culture, noting that while leadership influences school culture, there is no significant relationship between school culture and school effectiveness.

Diverse studies have highlighted the central role of principals in fostering collaboration, school culture, and teacher development, though they approach these concepts in different ways (Çoban et al., 2023; DeMatthews, 2014; Gumuseli and Eryilmaz, 2011; Jabonillo, 2022; Karadağ et al., 2020; Sahlin, 2022, Turan and Bektas, 2013). Gumuseli and Eryilmaz (2011) emphasize the principal’s role in promoting professional learning communities (PLCs) to enhance school quality, a view supported by DeMatthews (2014), who advocates for distributed leadership to empower teachers through PLCs, thereby fostering collaboration and improving student achievement. Karadağ et al. (2020) expand on this by examining the role of spiritual leadership and school culture, concluding that both factors positively influence academic performance. This perspective is aligned with Turan and Bektas (2013), who find a significant relationship between leadership practices—such as vision creation and personnel encouragement—and school culture. Sahlin (2022) similarly underscores the importance of principals in leading school improvement through active participation and clear direction. Lastly, Çoban et al. (2023) emphasize the importance of building trust with teachers and prioritizing instruction to foster collaboration and enhance self-efficacy. Collectively, these studies illustrate the multifaceted role of leadership in shaping a positive school environment, with a shared emphasis on leadership’s role in promoting collaboration, school culture, and teacher effectiveness.

Allton (1994) posits that principals serve as cultural leaders, akin to artists who shape the identity of their schools. This perspective underscores the essential role of school leaders in actively fostering a positive culture that enhances instructional effectiveness. In this context, Johnson et al. (1996) expand on the concept of school culture by introducing the idea of school work culture, which refers to the collective work patterns within a school. They argue that productive organizations are driven by shared goals and collaborative efforts, reinforcing the notion that a strong school culture enhances overall effectiveness and productivity. Building on this, Gaziel (1997) emphasizes the crucial role of school culture, particularly in institutions serving disadvantaged students, where a commitment to continuous improvement, staff dedication, and clear policies can significantly enhance performance. Phelps (2008) further enriches this discussion by advocating for the cultivation of teacher leadership, arguing that empowering educators to assume leadership roles fosters a collaborative environment that benefits both teachers and students. This innovative approach to school improvement underscores the interconnectedness of effective leadership and a supportive culture, as highlighted by Atkinson (2000), who asserts that meaningful progress cannot rely solely on individual talent. Instead, he advocates for a dedicated and collaborative team effort to create a thriving school environment.

Friedman (1991) and Fullan (1995) emphasize the critical role of school culture in fostering teacher well-being and effectiveness. Friedman explores how a supportive environment, in which teachers are recognized as professionals, can significantly reduce burnout, ultimately enhancing their engagement and performance. Similarly, Fullan advocates for continuous learning among educators, arguing that a culture prioritizing academic achievement and teamwork is essential for sustained improvement. He cautions against the isolation of the “lonely martyr” teacher, emphasizing that collaboration and support among educators are crucial for long-term success. Complementing these ideas, Killion (2006) discusses how a positive school culture can enhance teachers’ willingness to engage in collaborative professional learning. She argues that transforming traditional professional development into collaborative practices increases both teacher and student learning time, highlighting the reciprocal relationship between school culture and professional development.

Organizational culture plays a fundamental role in shaping identity and behavior. Schein (1990, 2004) highlights that shared assumptions and values significantly influence organizational actions. Derr et al. (2002) examine the impact of national culture on leadership development, asserting that cultural values, norms, and artifacts are pivotal in shaping leadership practices. They emphasize the importance of culturally responsive leadership that accounts for diverse contexts, a principle essential for educators navigating the complexities of school environments. March and Weil (2005) argue that fostering mutual trust and delegation is critical for enhancing individual commitment to organizational goals. Additionally, Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) stress the necessity of resilience amid uncertainty, advocating for a culture that prioritizes open communication and encourages error reporting to improve organizational performance. Teasley (2016) underscores the vital role of leadership and collaboration in cultivating a positive school culture. He also explores the dual effects of school culture—both positive and negative—on effectiveness, morale, and student learning potential, emphasizing the need for a deliberate approach to create a supportive and collaborative environment essential for educational success.

Recent studies also emphasize the importance of leadership in fostering a creative and innovative educational environment. Shamasneh (2022) emphasizes the role of motivational leadership in enhancing creativity among teachers. The study shows that effective leadership practices can significantly improve teacher motivation, contributing to the development of a culture of innovation. This finding aligns with Pažur et al. (2020), who discuss the correlation between democratic school leadership and democratic school culture. Principals who practice democratic leadership contribute significantly to fostering a culture that nurtures creativity and teacher engagement, ultimately enhancing student learning. Additionally, Mutohar et al. (2021), found that principal leadership behavior, teacher role models, and a positive school culture are essential in shaping student character and preparing students to adapt to a globalized world. These elements of leadership and culture align with findings from Nelianti Fitria and Puspita (2021) observed that principal leadership and school work culture directly influence teacher professionalism, with both factors contributing to an environment that promotes teacher growth and performance.

The role of transformational leadership in fostering organizational learning and school culture has also been highlighted by Kızıloğlu (2021). His study indicates that transformational leadership, when supported by a positive organizational culture, can significantly improve learning outcomes. The importance of leadership styles is further supported by Gyimah (2020), who found that transformational, transactional, and instructional leadership styles positively impact both school culture and performance. These studies reinforce the idea that leadership styles directly influence the quality of school culture and, in turn, contribute to improved school performance. Finally, Zepeda et al. (2022) highlight the significance of teacher voice in shaping school culture. By fostering an environment where teachers feel empowered to share their ideas, schools can create a culture of continuous improvement. Teacher agency, rooted in trust and respect, enables teachers to contribute meaningfully to school development.

Methodology

Participants

The participants in this study include a total of 149 individuals across three phases. The first phase involved 12 school leaders (N = 12), comprising 8 principals and 4 vice-principals from 9-year-old schools in the Durrës district. The second phase included 137 teachers (N = 137) from various departments including science, social, and elementary education subjects. In the third phase, an observation was conducted involving both teachers and principals from the five selected schools, coded Sa, Sc, Sd, Se, and Sm.

Instruments

Data were collected through a combination of unstructured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and surveys. In the first phase, unstructured interviews with the school leaders focused on indicators of school culture, including celebrations, stories, common sayings, taboos, rituals, ways of rewarding, communications, and events, as outlined by Stoll (1999). In the second phase, semi-structured interviews were adapted from the “School Leader’s Tool for Assessing and Improving School Culture” (Wagner, 2006) and focused on aspects such as Professional Collaboration, Affiliative Collegiality, and Self-Determination/Efficacy. These interviews included a mix of closed and open-ended questions. In the third phase, a manual observation tool was utilized, where teacher-observers manually recorded words and phrases frequently expressed by the principals and teachers in the selected schools.

Data collection procedures

The data collection was carried out in three distinct steps:

1. Unstructured Interviews with School Leaders: Preliminary data were gathered through unstructured interviews with 12 school leaders. The data were transcribed and coded using open, axial, and selective coding.

2. Semi-Structured Interviews with Teachers: In the second phase, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 137 teachers across various subject areas. These interviews used both closed and open-ended questions to explore key aspects of school culture. Data collection occurred over a period of 3 months, with interviews distributed and collected according to school codes (Sa, Sb, Sc, Sd, Se, Sf, Sm, Sn).

3. Observation in Selected Schools: In the final phase of the study, observations were conducted in five schools (coded Sa, Sc, Sd, Se, and Sm) over a period of 2 months. The schools were selected based on three key criteria: (1) location (ensuring a balance between central, suburban, and rural schools), (2) average score results (with schools classified as low, medium, or high, based on collected data; see Table 2), and (3) issues identified during interviews with teachers. The observations were carried out by 3–4 teachers per school, minimizing the subjectivity of the observer. These teacher-observers were thoroughly trained in ethical guidelines and research procedures, which included informed consent, confidentiality, and respect for participants’ privacy. Additionally, they were briefed on the importance of impartiality and how to conduct observations in a way that ensures no harm or bias. Finally, discussions were held with each observer to clarify their notes and gain deeper insights into their perceptions of the overall observation process.

Data analysis procedures

Data analysis was conducted through grounded theory methodology, using the processes of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Corbin and Strauss, 2014). The analysis followed a cyclical and continuous process, beginning with the initial coding of interview data and expanding as more data were gathered from teachers (Glaser and Strauss, 2017) and through observations (Charmaz, 2006). Constant comparisons were made between concepts related to school culture, allowing for the development of narratives and theories on positive versus negative school cultures. Triangulation and data validation were also integral to the analysis, ensuring the robustness of the findings and the creation of a theory on school culture.

Findings and discussion

Perceptions of school leaders on school culture (research step 1)

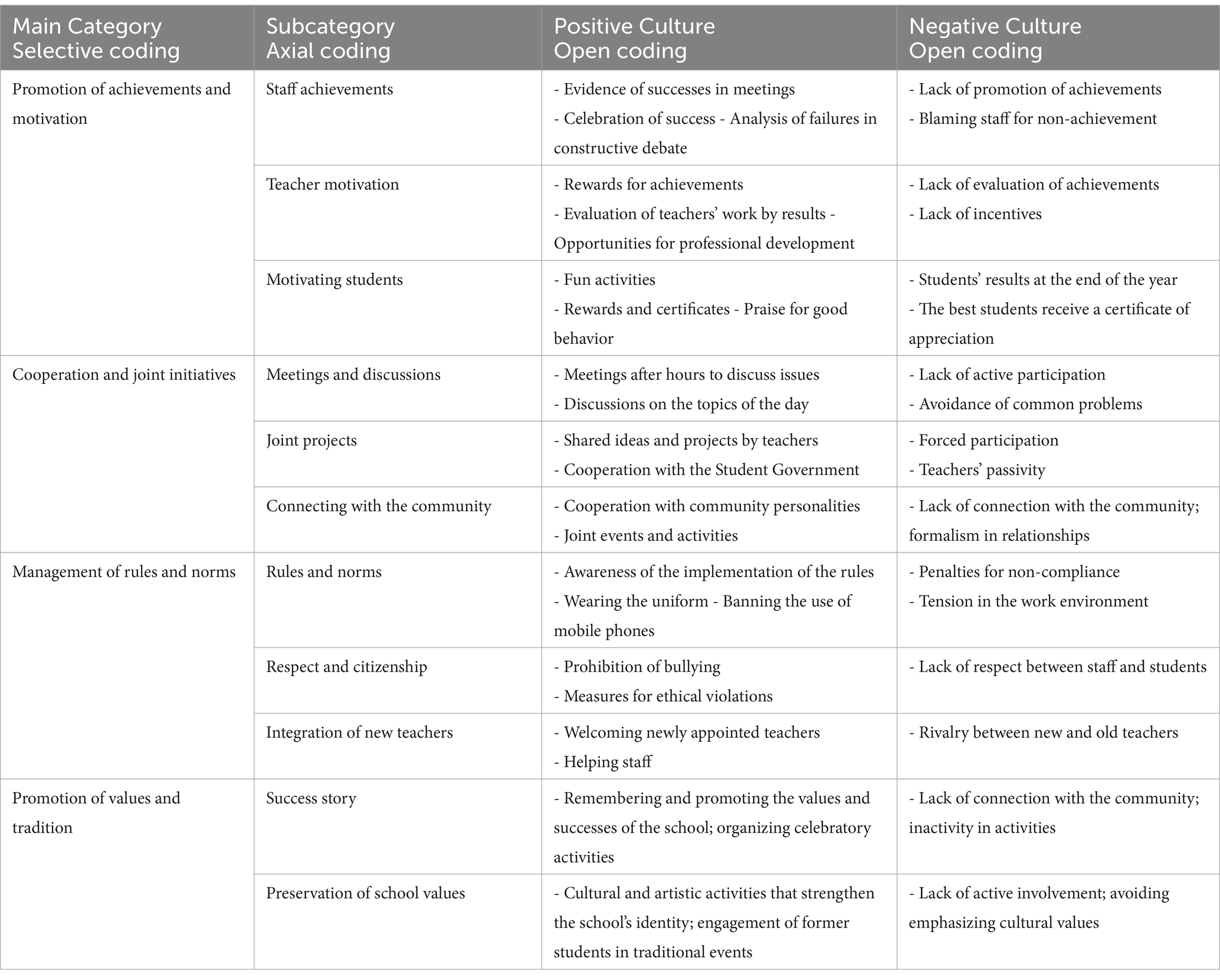

The analysis of school leaders’ transcripts revealed 26 distinct codes that captured both positive and negative aspects of school culture. These codes were organized into 11 subcategories and 4 core categories: promotion of achievements and motivation; collaboration and joint initiatives; management of rules and norms; and promotion of values and traditions, as summarized in Table 1. The distinction between positive and negative school culture was based on criteria such as the presence or absence of supportive leadership behaviors, recognition of achievements, opportunities for collaboration, clarity and fairness in the enforcement of rules and norms, and the alignment of shared values and traditions. In a positive school culture, leaders create a motivational environment where both staff and students feel valued and supported, consistent with the principles of transformational leadership. Effective principals inspire, motivate, and provide individualized support to their teams, fostering professional growth and achievement (Engels et al., 2008). This focus on recognition, achievement, and ongoing professional development nurtures a thriving academic atmosphere. For instance, principals who recognize staff and student successes through ceremonies, awards, and incentives help create a positive climate that boosts morale and drives high performance (Habegger, 2008; McChesney and Cross, 2023). These behaviors align with the school’s vision, setting high academic standards and cultivating a shared commitment to growth (Jerald, 2006; Lee and Louis, 2019). While the promotion of achievements and motivation is an essential aspect of a positive school culture, collaboration and joint initiatives, management of rules and norms, and the promotion of values and traditions are equally crucial in distinguishing positive school cultures from negative ones. In contrast, negative school cultures often lack these leadership practices and structural support, which leads to disengagement and disconnection within the school community (Verma, 2021). A misalignment between actions, values, and traditions can hinder a school’s ability to improve student outcomes, as observed in environments where trust, collaboration, and professional development are minimal, leading to stagnation and low motivation (Jerald, 2006).

The following table provides a detailed overview of the identified categories and subcategories, illustrating key themes related to school culture based on principals’ perceptions.

Building on the selective coding analysis, which identified these key dimensions of school culture, the following discussion provides a deeper exploration of how these core categories contribute to shaping a positive or negative school environment:

Promotion of achievements and motivation

In a positive school culture, achievements of staff and students are consistently recognized and celebrated. The school leadership actively highlights successes in meetings, fostering a sense of pride and motivation among teachers. For instance, motivational ceremonies, awards, and modest financial incentives for students encourage a thriving academic environment. Willower (1984) supports this by emphasizing the significance of shared values and goals in promoting a culture of excellence. Generative dialogue within organizations promotes inclusivity and mindfulness, helping leaders foster a unified narrative that supports an inclusive culture (Wasserman et al., 2008). Conversely, a negative culture is characterized by a lack of recognition and support for achievements. Here, the leadership adopts a more transactional approach, implying that staff are expected to fulfill their duties without acknowledgment of their efforts. This atmosphere may lead to resentment and disengagement among both teachers and students, ultimately undermining motivation (Gaziel, 1997).

Collaboration and joint initiatives

Effective principals encourage collaboration through regular meetings and discussions about challenges and ideas. Allton (1994) highlights that principals act as cultural leaders, fostering environments that promote collective problem-solving. Engaging in joint projects with teachers and the student government further enhances collaboration and ownership over school initiatives, contributing to a sense of community. By being authentic and strategically using personal experiences, principals help cultivate a trustworthy and supportive atmosphere (Wasserman et al., 2008). In contrast, negative cultures often exhibit a lack of initiative and collaboration. Teachers may isolate themselves, leading to finger-pointing regarding student outcomes. This environment stifles innovation and prevents the sharing of best practices, resulting in stagnation (Rhodes et al., 2011). By using “defense mechanisms” (Argyris, 2000, 2004), teachers maintain two different “theories of action” regarding effective behavior: what they advocate for and what they actually use. If this process persists over time, boundaries can transform into obstacles, and what begins as protection can evolve into isolation (Freiberg, 1999).

Management of rules and norms

A positive culture thrives on clearly communicated norms and rules that are collaboratively established and enforced. This approach fosters respect and accountability among staff and students. Willower (1984) suggests that creating structures that support professional learning can enhance adherence to norms, promoting a safe and productive educational atmosphere. In a negative school culture, rules may be enforced rigidly without input from the school community, leading to resentment and noncompliance. This can manifest in students feeling alienated and disengaged from the school environment. The lack of supportive leadership can result in disciplinary measures being seen as punitive rather than constructive (Opdenakker and Van Damme, 2007).

Promotion of values and traditions

A thriving school culture is rooted in shared values and traditions that celebrate community and inclusivity (Peterson and Deal, 2009; Schein, 2004). Schools that emphasize cultural heritage and collective achievements foster a sense of belonging among students and staff. Paradise and Robles (2016) highlight the importance of integrating community values into daily school life, promoting a cohesive educational environment. In contrast, a negative culture often overlooks the significance of shared values and traditions, leading to fragmentation within the school community. Without a cohesive identity, students and staff may feel disconnected from the school’s mission, resulting in lower engagement and commitment (Shaw and Reyes, 1992).

Positive school culture compared to negative culture according to teachers’ perception (research step 2)

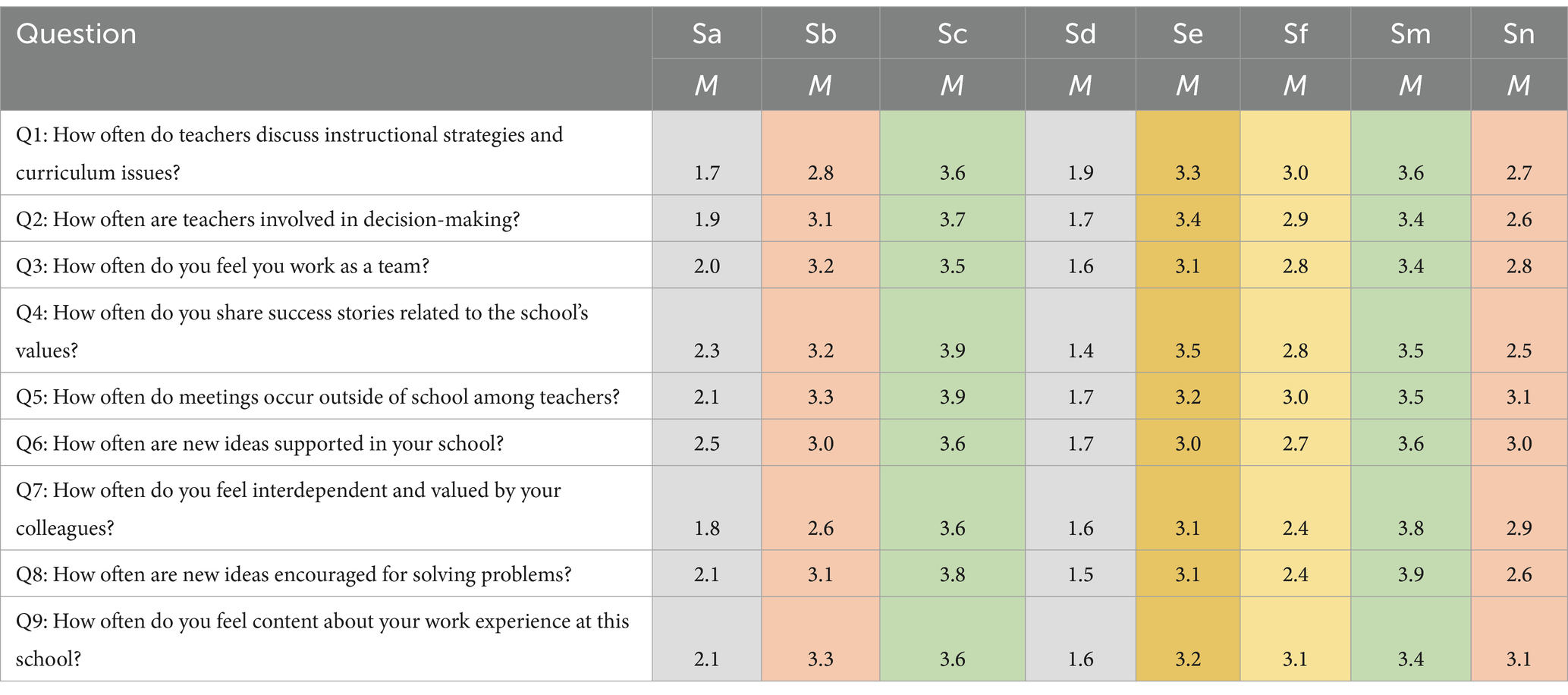

The average scores in Table 2 were calculated by averaging the responses from teachers across the 9 questions. These scores, categorized by school type (urban: Sa, Sb, Sc; rural: Sd, Sm, Sn; suburban: Sf, Se), reflect behaviors and perceptions related to collaboration, collegiality, and self-determination within each school culture. The scale ranges from 1 (never) to 5 (always), capturing variations in how often teachers engage in activities such as discussing instructional strategies, sharing successes, participating in decision-making, and fostering a team-oriented environment.

These scores provide insight into the level of engagement and satisfaction within each school, reflecting teachers’ perceptions of their work environment. Higher average scores indicate a positive culture marked by collaboration, trust, and shared success, while lower scores suggest negative aspects, such as poor communication, lack of collaboration, and low morale.

Exploring variations in school culture: insights from high and low scoring schools

Based on the average scores, we conclude that Schools Sc and Sm exhibit high levels of cooperation and respect, indicating a positive school culture and strong teacher commitment. These schools consistently score highly on key questions, such as Q4 (sharing success stories), with Sc (M = 3.9) and Sm (M = 3.5), and Q5 (meetings outside of school), with Sc (M = 3.9) and Sm (M = 3.5). The informal sharing of stories, achievements, and experiences plays a critical role in reinforcing school values and norms, contributing to a cohesive work environment (Kotter, 1996). By studying the behaviors and manners of school members, along with relevant activities and ceremonies, we can better understand the school’s overall behavioral culture (Dongjiao, 2022). Q7, which measures teachers’ perceptions of interdependence and feeling valued, scores particularly high in Sm (M = 3.8) and Sc (M = 3.6), reflecting strong collegial relationships and a shared sense of purpose. In these schools, teachers are more likely to feel supported by their peers, creating a positive atmosphere conducive to collaboration (Lee and Louis, 2019; Sahlin, 2022). Q8 (encouraging new ideas for problem-solving) also reflects this trend, with Sm and Sc scoring M = 3.9 and M = 3.8, respectively. This suggests that innovation and a willingness to embrace change are actively encouraged, further reinforcing a positive, forward-thinking culture. Teachers’ own beliefs and attitudes toward professional learning and development influence how they engage with and implement new ideas in their teaching (McChesney and Cross, 2023). Higher-scoring schools typically demonstrate stronger communal ties and a more collaborative culture, which are essential for fostering staff commitment (Peterson and Deal, 2009).

In contrast, Schools Sd and Sa show lower scores on several key questions, particularly Q1 (discussing instructional strategies), with Sa (M = 1.7) and Sd (M = 1.9), and Q4 (sharing success stories), with Sa (M = 2.3) and Sd (M = 1.4). These lower values indicate limited collaboration, minimal engagement in decision-making, and a lack of experience-sharing, suggesting a more hierarchical and less dynamic culture (Verma, 2021). Additionally, Q7 scores are particularly low in both Sa (M = 1.8) and Sd (M = 1.6), suggesting that teachers in these schools may not feel valued or supported by their colleagues. This lack of interdependence could hinder professional growth and contribute to feelings of isolation. Q8 also shows lower engagement in Sa (M = 2.1) and Sd (M = 1.5), indicating that these schools may be less open to new ideas and collaborative problem-solving, which can limit their ability to adapt and innovate. In these schools, teachers may struggle to feel valued or supported, hindering their professional growth and commitment. Moreover, the absence of regular engagement in sharing successes or solving problems collaboratively can reinforce a rigid, hierarchical structure, limiting adaptability and growth. This stagnant culture restricts meaningful collaboration, ultimately reducing overall school effectiveness (Peterson and Deal, 2009).

Exploring core categories from teacher responses to open-ended questions

Based on the transcripts obtained from the open-ended interview questions, the data were analyzed using open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. This process resulted in the creation of 48 codes, 16 subcategories, and 4 main categories: Environment and Collaboration; Leadership Style; Development Opportunities; Activities and Celebrations.

Environment and collaboration

Positive Culture (schools Sc and Sm): There is a strong sense of support and collaboration among teachers, with constructive criticism for improvement (school Sc). Teachers feel like they are part of a family and work closely with the local community, promoting values and traditions (school Sm).

Teachers reported:

“In school, there is hard work and strong collaboration; criticism for improving work is natural in meetings with groups of teachers, according to departments.” (Teacher 11, Sc).

“Every teacher at the school has found support from the staff and the school directorate during difficult moments (not only in their work but also in cases of illness or family tragedies).” (Teacher 8, Sc).

“We feel like we are in a family, where everyone shares everything with each other.” (Teacher 5, Sm)

“Teachers coming from the city appreciate and collaborate closely with the teachers and the local community.” (Teacher 10, Sm).

Negative Culture (school Sa and Sd): There is a lack of discussion and collective decision-making; teachers focus on their personal problems and do not feel encouraged to contribute more (School Sd). There is a lack of clarity in guidance and involvement in decision-making; teachers feel disengaged (school Sa).

Teachers’ reported:

“The requests are often unclear, and meetings frequently end with a lack of clarity regarding what is required concerning orders and directives from above.” (Teacher 20, Sa).

“Teachers do not have the opportunity to discuss; we simply accept what the school directorate decides.” (Teacher 14, Sa).

“Each teacher looks at their own work and family problems.” (Teacher 4, Sd).

“We gather together, but we discuss school issues very little.” (Teacher 8, Sd).

“The decisions of the school are made by the school directorate.” (Teacher 4, Sa).

Chong and Kong (2012) and Willower (1984) both highlight the importance of balancing teacher autonomy with collaborative practices to enhance instructional effectiveness. In schools Sc and Sm, the establishment of formal learning communities allowed teachers to collaborate and share best practices, directly reflecting Willower’s concept of fostering ongoing collaboration. Interviewees reported that this environment boosted their confidence and efficacy. In contrast, schools Sa and Sd had more hierarchical structures that limited teacher autonomy, corroborating Meier’s (2012) findings that collaborative environments are crucial for effective instruction.

Activities and celebrations

Positive Culture (schools Sc and Sm): Activities and celebrations provide opportunities for socializing among teachers (school Sc). Organizing celebrations in collaboration with the community is a tradition (school Sm).

Teachers reported:

“It is a tradition of the school that year-end celebrations are held with the community.” (Teacher 10, Sc).

“Activities such as greening the environment, culinary events promoting local dishes, and showcasing traditional Albanian clothing on national holidays have become a school tradition.” (Teacher 7, Sc).

“Despite work debates, in our free time or after classes, on regular days or even on holidays, we gather in each other’s company, celebrating birthdays or personal events.” (Teacher 14, Sm).

Negative Culture (schools Sa and Sd): Teachers have a limited role in organizing activities, leading to a division of responsibilities (school Sa). School activities are lacking, and student interest is low (school Sd).

Teachers reported:

“Activities are lacking in the school. There are absences of students in the classrooms.” (Teacher 1, Sd).

“Students are not interested in learning.” (Teacher 9, Sd).

“The staff’s opinions are only considered for excursions or festive events, but not for other school initiatives.” (Teacher 3, Sa).

When the principal highlights general values of symbolic importance, it enables teachers to frame their activities in relation to socially significant human goals and to connect their daily work to educational values. This awareness of values is a hallmark of a school culture that supports improvement (Willower, 1984). “Without ceremonies, traditions, and rituals, we could easily lose our way amid the complexity of everyday life at work” (Peterson and Deal, 2009: 39).

Leadership style

Positive Culture (schools Sc and Sm): The leader is inspirational and values the work of the staff (school Sc). The leader knows the community well, creating a supportive environment (school Sm).

Teachers’ reported:

“It is a pleasure to work in an environment where hard work and achievements are valued.” (Teacher 13, Sc).

“There is much to learn from an experienced leader who is professional, a good listener, and a visionary.” (Teacher 3, Sc).

“The principal is an inspiring role model.” (Teacher 1, Sc).

“Every teacher at the school has found support from the principal.” (Teacher 7, Sm).

“The principal is from this area and knows the community’s mindset well.” (Teacher 3, Sm).

“The principal is a strong advocate regarding work and a special friend, gentle and supportive at the same time.” (Teacher 12, Sm).

According to Cohen (2010), the most significant motivational factors include working with respected individuals, engaging in interesting tasks, receiving recognition for good work, having opportunities to develop skills, and collaborating with individuals who listen to ideas for the benefit of the work.

Negative Culture (schools Sa and Sd): Leadership is authoritarian and critical, providing insufficient support for development (Sa). The leader is liberal, resulting in a lack of engagement and planning (Sd).

Teachers’ reported:

“The principal is liberal, and the annual plan is formal.” (Teacher 5, Sd).

“Changes or new findings are not communicated.” (Teacher 13, Sa).

“We are unclear about the requests and tasks.” (Teacher 21, Sa).

“The vice principal creates obstacles for integrated teaching lessons and does not accept discussions.” (Teacher 17, Sa).

“Both new and old teachers face a leader who only criticizes and does not offer support.” (Teacher 7, Sd).

Leaders must balance authority and approachability, as excessive power may lead to tyranny, while too little can appear weak (March and Weil, 2005). When a leader views direction, directives, and control as the most effective methods for managing an institution or community, they are essentially rejecting the idea of empowerment (Block, 1987).

Opportunities for development

Positive Culture (schools Sc and Sm): Staff engage in meetings for improvement (school Sc). Help and experience sharing are present (school Sm).

Teachers’ reported:

“The leader shares her work experience as a methodologist and teacher with the staff.” (Teacher 11, Sm).

“The principal values and encourages every school project and initiative.” (Teacher 8, Sm).

“The department heads coordinates the work.” (Teacher 2, Sc).

“We observe each other’s classes, especially for specific topics.” (Teacher 11, Sm).

“We participate in training sessions both inside and outside the school.” (Teacher 6, Sc).

Negative Culture (schools Sa and d): There is a lack of efficiency in professional development and no constructive discussions (school Sa). Development is formal and lacks real impact (school Sd). Teachers’ reported:

“Professional development is fictional.” (Teacher 3, Sd).

“No one discusses or debates the open teaching classes.” (Teacher 15, Sa).

“We are not trained for the needs we have.” (Teacher 6, Sd).

“New teachers are incompetent and do not want to work.” (Teacher 2, Sa).

“Open classes are held twice a year, and they are formal.” (Teacher 7, Sd).

“We are tired of worthless things.” (Teacher 2, Sd).

“When I came to this school, no one helped me.” (Teacher 1, Sa).

“We are not included in projects.” (Teacher 8, Sa) and (Teacher 10, Sd).

These findings resonate with Sergiovanni’s perspective that school culture is shaped more by shared values than by management controls. The significance of socialization and share activities in fostering a strong school culture is underscored by Nonaka et al. (2001), who highlight that shared experiences can enhance tacit knowledge and collective efficacy. In conclusion, Schools Sc and Sm demonstrate high indicators of professional collaboration, collegiality, and self-determination compared to Schools Sd and Sa. This difference may stem from teachers being more responsive to shared values and norms than to management controls (Sergiovanni, 2001). A positive culture builds commitment (Peterson and Deal, 2009), and informal meetings and storytelling enhance connections among students, influencing behavior norms and shared values. Consequently, school culture becomes powerful because these interactions occur naturally and without conscious intention, making it difficult to challenge or question (Kotter, 1996).

Values/beliefs/attitudes of principal and teacher based on 2 months observations

The observations from the four schools reveal a distinct correlation between the values and beliefs held by principals and the resulting attitudes of teachers. Each principal’s approach creates a unique environment that affects teacher morale, engagement, and ultimately student success.

At school Sa (Urban), the principal’s values center on authority and compliance. Phrases like “I know this” and “It will be done as I say” illustrate a belief in a top-down approach that stifles collaboration. This leads to teacher frustration, as reflected in statements like “Students are not like they used to be” and “We’re wasting our time.” The overall atmosphere is one of disengagement, highlighting the need for improved communication and support. In contrast, school Sc (Urban) showcases a principal who values collaboration and open dialogue. The principal’s encouragement of discussion is evident in phrases such as “How do you see this?” and “Let us meet to discuss.” This fosters a belief in the importance of diverse perspectives and maintaining the school’s reputation. Teachers echo this collaborative spirit with statements like “Let us help the students” and “I can help,” creating a positive attitude that promotes engagement and proactive involvement. School Sd (Rural) presents a different picture, with the principal’s values rooted in control and urgency. Phrases like “Come on, move!” and “I want it done today!” reflect a belief in strict accountability, which cultivates a punitive attitude. Teachers express disillusionment, stating, “Our work no longer has value” and “These are pointless tasks.” The overall environment is negative, indicating an urgent need for a shift toward more supportive leadership. Conversely, in school Sm (Rural), the principal embodies an optimistic and collaborative leadership style. Phrases such as “Nothing is impossible” and “Let us do it together” highlight values of teamwork and support. This belief fosters an attitude of encouragement, with teachers expressing sentiments like “I was pleased with the students’ preparation” and “Let us celebrate the children’s achievements.” The result is a vibrant and engaging atmosphere that values community and recognizes accomplishments.

The following table highlights the most frequently noted phrases from each school, illustrating the stark contrasts in principal and teacher attitudes (Table 3).

From these observations, it is evident that values and beliefs significantly influence the attitudes of both principals and teachers. A collaborative and supportive leadership style fosters engagement and satisfaction, while authoritarian and punitive approaches can lead to disengagement and disillusionment. Thus, the nature of leadership is crucial in creating a thriving educational community. In conclusion, schools where principals adopt an authoritarian style, such as Sa (Urban) and Sd (Rural), tend to exhibit a culture marked by disengagement and dissatisfaction among teachers. The focus on compliance and control creates an environment where teachers feel undervalued and disillusioned, ultimately hindering their motivation and effectiveness. Conversely, in schools like Sc (Urban) and Sm (Rural), where principals embrace collaborative and supportive leadership styles, the school culture thrives. Open communication and a shared sense of purpose foster engagement and satisfaction among teachers, resulting in a positive atmosphere that benefits both educators and students. This analysis underscores the importance of leadership in shaping school culture, as “leadership and culture are two sides of the same coin” (Schein, 2004, p. 10).

Conclusion

Based on data triangulation from principal-teacher interviews and a two-month observation, the findings suggest that in schools with a positive culture, there are fewer perceptual differences between principals and teachers. This is because these schools are perceived as familiar environments where both parties contribute jointly to shared values and achievements. In these schools, rituals, holidays, entertainment, ceremonies, healthy debates, and open communication help foster an environment where relationships are both supportive and collaborative (Denning, 2004; Peterson and Deal, 2009; Stolp, 1996).

In contrast, in schools with a negative culture, perceptual differences arise between the leaders and teachers. Leaders tend to see their role as one focused on accountability, structure, rigid planning, and enforcement of rules, while teachers view their leaders as distant, unable to solve their problems, and somewhat one-dimensional in their approach. This disparity in perception often results in defensive mechanisms (Argyris, 1995), which hinder open communication and trust.

The analysis also highlights that professional collaboration, affiliative collegiality, and self-determination are more prominently observed in schools with a positive culture. A truly positive school culture extends beyond mere discipline and involves shared values and norms that unite the community toward common goals (Craig, 2006; Dongjiao, 2022). In such schools, the role of the leader is crucial in promoting collaboration (Engels et al., 2008), involving the “teacher voice” (Zepeda et al., 2022) in decision-making processes, and fostering an environment where healthy debates and accountability occur, without resulting in quarrels or divisions between teachers.

Moreover, in schools with a positive culture, it is evident that the leader is supportive and kind to the staff regarding their personal and family problems, as much as he is demanding, stimulating and motivating at work. These schools also tend to promote national and local traditions, which reinforces a sense of community among both teachers and students.

While the findings indicate strong indicators of positive culture in urban and rural schools, it is important to approach the assertion that positive school culture is independent of demographic indicators with caution. The current study’s design does not provide conclusive evidence to definitively support this claim. Instead, the role of the leader in fostering a positive school culture emerged as a significant factor in sustaining a healthy school environment, irrespective of school size or location.

In this last point, it is noted that rural schools with a positive culture convey school cultural indicators that are more integrated and closer to the tradition of the area, referring to the clothing and cooking of the area; rites and customs, while the schools of the center with a positive culture demonstrate their individuality by participating in projects, activities and enterprises that promote the local culture. This study suggests that school culture is an area of great interest for future research, particularly in relation to the promotion of school, national, and human values.

Limitation and suggestions for future research

The experiences of a small group of leaders may not represent the broader population of school leaders across different contexts. The geographical focus on the Durres district may also limit the findings’ applicability to other regions, especially those with differing socio-economic, cultural, or educational contexts. The two-month observation period might not be long enough to capture the dynamic nature of school culture. School cultures can evolve over time, and a more extended observation period might provide deeper insights into these changes and the sustainability of positive cultures.

To address these limitations, future research could consider expanding the sample size and geographical diversity, utilizing longitudinal studies to observe changes over time, and incorporating a broader range of contextual factors that influence school culture.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data was collected manually. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AP; dWFtZC5hbmlsNzlAeWFob28uY29t.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Durres Regional Educational Directorate. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KL: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Aleksander Moisiu University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Apramian, T., Cristancho, S., Watling, C., and Lingard, L. (2016). (re)grounding grounded theory: a close reading of theory in four schools. Qual. Res. 17, 359–376. doi: 10.1177/1468794116672914

Argyris, C. (1995). Action science and organizational learning. J. Manag. Psychol. 10, 20–26. doi: 10.1108/02683949510093849

Argyris, C. (2000). Flawed advice and the management trap: How managers can know when they’re getting good advice and when they’re not. Oxford University Press.

Aspin, D. N. (2005). “Values, beliefs and attitudes in education: the nature of values and their place and promotion in schools” in Institutional Issues (Routledge), 197–218.

Block, P. (1987). The empowered manager: Positive political skills at work.San. Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.XV.

Bush, T. (2021). School leadership and culture: societal and organisational perspectives. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadership 49, 211–213. doi: 10.1177/1741143220983063

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Chiang, H., Lipscomb, S., and Gill, B. (2016). Is school value added indicative of principal quality? Educ. Finance Policy 11, 283–309. doi: 10.1162/EDFP_a_00184

Chong, W. H., and Kong, C. A. (2012). Teacher collaborative learning and teacher self-efficacy: the case of lesson study. J. Exp. Educ. 80, 263–283. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2011.596854

Çoban, Ö., Özdemir, N., and Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2023). Trust in principals, leaders’ focus on instruction, teacher collaboration, and teacher self-efficacy: testing a multilevel mediation model. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadership 51, 95–115. doi: 10.1177/1741143220968170

Cohen, A. W. (2010). Heroic leadership: Leading with integrity and honor. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Craig, J. (2006). School culture: the hidden curriculum : The Centre for Comprehensive School Reform and Improvement, 1–7.

DeMatthews, D. E. (2014). Principal and teacher collaboration: an exploration of distributed leadership in professional learning communities. Int. J. Educ. Leadership Manag. 2, 176–206. doi: 10.4471/ijelm.2014.16

Derr, C. B., Roussillon, S., and Bournois, F. (2002). Cross-cultural approaches to leadership development. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Dongjiao, Z. (2022). Overview of school culture and its management. School Cult. Improve. Denmark: River Publishers. 1–53. doi: 10.1201/9781003339359-1

Engels, N., Hotton, G., Devos, G., Bouckenooghe, D., and Aelterman, A. (2008). Principals in schools with a positive school culture. Educ. Stud. 34, 159–174. doi: 10.1080/03055690701811263

Freiberg, H. J. (Ed.). (1999). Perceiving, behaving, becoming: Lessons learned. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Alexandria, VA, USA.

Friedman, I. A. (1991). High and low-burnout schools: school culture aspects of teacher burnout. J. Educ. Res. 84, 325–333. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1991.9941813

Fullan, M. (1995). The school as a learning organization: distant dreams. Theory Pract. 34, 230–235. doi: 10.1080/00405849509543685

Gaziel, H. H. (1997). Impact of school culture on effectiveness of secondary schools with disadvantaged students. J. Educ. Res. 90, 310–318. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1997.10544587

Glaser, B., and Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. London & New York: Routledge.

Gumuseli, A. I., and Eryilmaz, A. (2011). The measurement of collaborative school culture (CSC) on Turkish schools. New Horizons Educ. 59, 13–26.

Gyimah, C. A. (2020). Exploring the role of school leadership styles and school culture in the performance of senior high schools in Ghana using PLS- SEM approach. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. Res. 3, 39–56. doi: 10.37500/IJESSR.2020.3044

Habegger, S. (2008). The Principal's role in successful schools: creating a positive school culture. Principal 88, 42–46.

Harris, D. N. (2009). Would accountability based on teacher value added be smart policy? An examination of the statistical properties and policy alternatives. Educ. Finance Policy 4, 319–350. doi: 10.1162/edfp.2009.4.4.319

Jabonillo, E. (2022). School culture and its implications to leadership practices and school effectiveness. Psychol. Educ. 5, 942–953.

Jerald, C. D. (2006). School culture. Washington, DC: Center for Comprehensive School Reform and Improvement.

Johnson, W. L., Snyder, K. J., Anderson, R. H., and Johnson, A. M. (1996). School work culture and productivity. J. Exp. Educ. 64, 139–156. doi: 10.1080/00220973.1996.9943800

Karadağ, M., Altınay Aksal, F., Altınay Gazi, Z., and Dağli, G. (2020). Effect size of spiritual leadership: in the process of school culture and academic success. SAGE Open 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2158244020914638

Killion, J. (2006). Collaborative professional learning in school and beyond: A tool kit for New Jersey educators. New Jersey: Department of Education & National Staff Development Council.

Kızıloğlu, M. (2021). The impact of school principal’s leadership styles on organizational learning: mediating effect of organizational culture. Business Manag. Stud. 9, 822–834. doi: 10.15295/bmij.v9i3.1814

Lee, M., and Louis, K. S. (2019). Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teach Teach Educ. 81, 84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.02.001

Maharani, S. N. (2021). Research paradigm on grounded theory method for accounting research: filtering all sensory input. Proceedings of the 7th Regional Accounting Conference (KRA 2020)

Makri, C., and Neely, A. (2021). Grounded theory: a guide for exploratory studies in management research. Int J Qual Methods 20, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/16094069211013654

McChesney, K., and Cross, J. (2023). How school culture affects teachers’ classroom implementation of learning from professional development. Learn. Environ. Res. 26, 785–801. doi: 10.1007/s10984-023-09454-0

Meier, L. T. (2012). The effect of school culture on science education at an ideologically innovative elementary magnet school: an ethnographic case study. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 23, 805–822. doi: 10.1007/s10972-011-9252-1

Mutohar, P. M., Trisnantari, H. E., and Masduki,. (2021). The effect of principal leadership behavior, teacher model, and school culture on student’ character in adapting to the global environment. Asian Soc. Sci. Human. Res. J. 3, 36–44. doi: 10.37698/ashrej.v3i2.78

Nelianti Fitria, H., & Puspita, Y. (2021). The Influence of school leadership and work culture on teacher professionalism. Proceedings of the International Conference on Education Universitas PGRI Palembang (INCoEPP 2021)

Nonaka, I., Konno, N., and Toyama, R. (2001). Emergence of “Ba”: a conceptual framework for the continuous and self-transcending process of knowledge creation. Knowledge Emergence, 13–29. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780195130638.003.0002

Opdenakker, M., and Van Damme, J. (2007). Do school context, student composition and school leadership affect school practice and outcomes in secondary education? Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 179–206. doi: 10.1080/01411920701208233

Paradise, R., and Robles, A. (2015). Two Mazahua (Mexican) communities: introducing a collective orientation into everyday school life. Eur J Psychol Educ. 31, 61–77. doi: 10.1007/s10212-015-0262-9

Pažur, M., Domović, V., and Kovač, V. (2020). Democratic school culture and democratic school leadership. Croat. J. Educ. 22, 1137–1164.

Peterson, K. D., and Deal, T. E. (2009). The shaping school culture fieldbook. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, 39.

Phelps, P. H. (2008). Helping teachers become leaders. The Clearing House: J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 81, 119–122. doi: 10.3200/tchs.81.3.119-122

Rhodes, V., Stevens, D., and Hemmings, A. (2011). Creating positive culture in a new urban high school. High Sch. J. 94, 82–94. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2011.0004

Sahlin, S. (2022). Teachers making sense of principals’ leadership in collaboration within and beyond school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 67, 754–774. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2022.2043429

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. Am. Psychol. 45, 109–119. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.109

Shamasneh, J. (2022). The degree of practicing the motivational leadership by the public school principals in the capital Amman governorate and its relationship to enhance the creativity culture among teachers from their point of view. J. Educ. Psychol. Sci. 6, 1–20. doi: 10.26389/ajsrp.n260821

Shaw, J., and Reyes, P. (1992). School cultures: organizational value orientation and commitment. J. Educ. Res. 85, 295–302. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1992.9941129

Stoll, L. (1999). School culture: black hole or fertile garden for school improvement? School Culture, 30–47. doi: 10.4135/9781446219362.n3

Stough, L. M., and Lee, S. (2021). Grounded theory approaches used in educational research journals. Int J Qual Methods 20, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/16094069211052203

Teasley, M. L. (2016). Organizational culture and schools: a call for leadership and collaboration. Child. Schools 39, 3–6. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdw048

Turan, S., and Bektas, F. (2013). The relationship between school culture and leadership practices. Eurasian. J. Educ. Res. 13, 155–168.

Verma, V. (2021). School culture: methods for improving a negative school culture. Int. J. Educ. Res. Stud. 3, 14–17.

Wagner, C. R. (2006). The school leader’s tool for assessing and improving school culture. Princ. Leadersh. 7, 41–44.

Wasserman, I. C., Gallegos, P. V., and Ferdman, B. M. (2008). Dancing with resistance. Divers. Resist. Organ., 175–200.

Weick, K. E., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Willower, D. J. (1984). School principals, school cultures, and school improvement. Educational Horizons 63, 35–38.

Keywords: leadership, school culture, professional collaboration, affiliative collegiality, self-determination

Citation: Plaku AK and Leka K (2025) The role of leaders in shaping school culture. Front. Educ. 10:1541525. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1541525

Edited by:

José Matias Alves, Faculdade de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, PortugalReviewed by:

J. Roberto Sanz Ponce, Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir, SpainMarisa Carvalho, Portuguese Catholic University, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Plaku and Leka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anila Koli Plaku, dWFtZC5hbmlsNzlAeWFob28uY29t

Anila Koli Plaku

Anila Koli Plaku Klodiana Leka2

Klodiana Leka2