94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 12 February 2025

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1536431

This article is part of the Research Topic Continuing Engineering Education for a Sustainable Future View all 19 articles

Introduction: Alternative credentialed forms of learning provide important learning pathways for professionals to up-and re-skill. In Scotland, credit-rating of learning is one option to create these credentialed courses, based on national principles from the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) Partnership. However, there is currently almost no evidence on the benefits of such an approach for those involved, so this study focuses on examining the benefits of having a flexible national qualification system (SCQF) that allows ‘credit-rating’ of organizational learning.

Methods: An exploratory research methodology using a single case study design (based on one Scottish university) was used. Nine semi-structured interviews (with both learning providers and university employees) were inductively analyzed using a two-cycle thematic analysis approach to determine themes.

Results: The SCQF guidance and the business-orientated nature of Scottish universities in credit-rating of learning were highlighted as an important enabler for this alternative form of credentialed learning to being possible. Value to learners focused on having a professionally relevant qualification that had validity, both through possible credit transfer to other programs and providing recognition of competence. Such credit transfer and entry into university programs is a benefit for the university and aligns to Scottish Government priorities of widening access as well as supporting up-and re-skilling. Credit-rating of learning also enhances the credibility of the learning provider’s offering and enhances their own quality assurance processes.

Discussion: Clear value to a range of stakeholders is created, with the university able to determine its own business model to provide credit-rating of learning, and this flexibility is important to align to institutional strategy, as well as to provide an effective, efficient service. It is recognized that credit-rating of learning co-creates value for the participants, and future research and opportunity lies around exploring this further. Credit-rating of learning has great potential to support national priorities, but this service needs to be better understood by companies and employers for it to reach its potential.

The landscape of education and workforce development has undergone significant transformations in recent decades, driven by globalization, technological advancements, and evolving labor market demands. The World Economic Forum estimates that, by 2025, 50% of all employees will need re-skilling due to adopting new technology (Li, 2022). Similarly, a McKinsey report indicates that by 2030, 1 in 16 workers will have to change occupation to meet the changing needs of the labor market (McKinsey, 2021). In addition, the workforce is more fluid as workers are motivated by varied factors (Work Institute, 2020, 2024), particularly millennials who highly value career development, with associated training and development. This group also changes employers more frequently, often intending to spend no more than 3 years with an employer (Tenakwah, 2021). Consequently, up-and re-skilling are important considerations for both individuals and organizations alike.

Responding to these career development needs, there are more options for individuals and organizations to support their employees to develop and grow, and this can support talent retention (McKinsey, 2023; LinkedIn Learning, 2024). These options cover both credential and non-credential options (Brown et al., 2021). The range of providers extends beyond formal education institutions, such as universities, and includes professional bodies (e.g., Chartered Management Institute, Institute of Engineering and Technology, and Institute for Electrical and Electronic Engineering), for-profit training providers, EdTech learning providers, learning platforms supporting Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and online education, employers, and third-sector (charity) organizations. Consequently, a competitive marketplace for training and development has emerged, and this is highly beneficial to learners and organizations alike to find a suitable solution to address short-term and long-term development needs.

While some of this learning is training, as it is focusing on skills development, not contextualized within formal education institutions and their systems and awards, there is an increasing development of more formalized learning, whether this is in the form of alternative credentials, micro-credentials, micro-and nano-certificates, and qualifications, typically in conjunction with formal learning providers (OECD, 2020a; West and Cheng, 2023). Gallagher (2022) and Díaz et al. (2022) conceptualize the university credentials landscape from degrees (long and broad offered by Education Institutions) to digital badges (short, targeted learning offered often by non-educational institutional providers), with alternative credentials occupying an intermediate space. Moreover, there are different practical and institutional implementations (business models) that range from content-push (such as universities offering short courses and micro-credentials based on areas of expertise), market-pull (courses with clear market requirement and companies partnering with universities) to partnership and co-creation (collaborative working to match expertise to meet clear need) (Carton et al., 2018; Rybnicek and Königsgruber, 2019). Furthermore, implementations allow varying loci of control and coverage, depending on technology platforms, partnership agreements, and national infrastructure and policy. Currently, there is an evolving credentials ecosystems and landscape that varies across country and institution.

This marketplace of credentials, reflecting the complexity outlined above, can make it more challenging for employers to understand what credentials mean and their associated quality. So, there are new forms of organizational and professional learning that seek credibility of that learning through working with formal education institutions. In essence, learning providers (outside of formal education institutions) are increasingly looking to make their learning provision more portable through quality-assured recognition within and benchmarking to National Qualifications Frameworks.

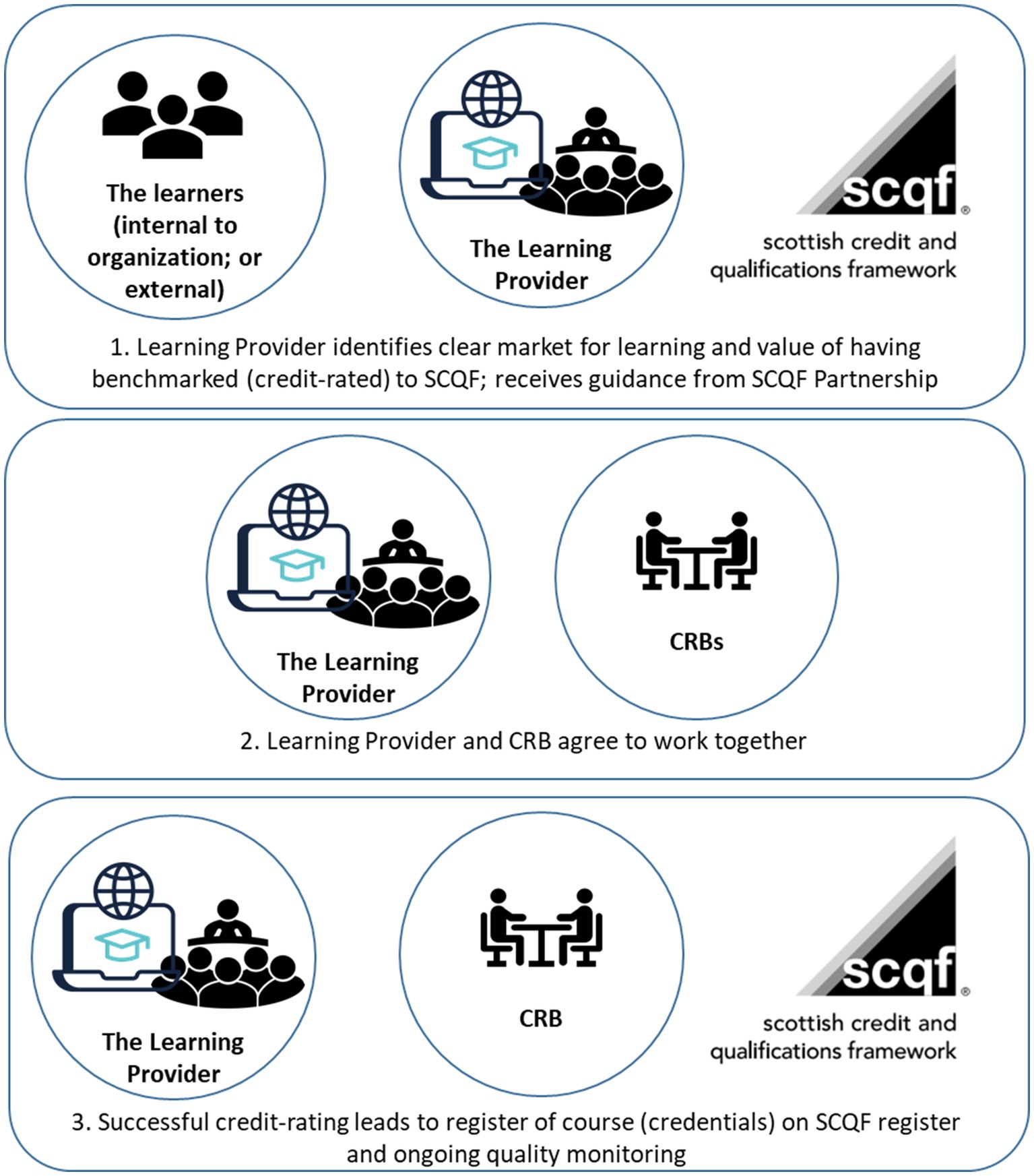

Within the Scottish education system, the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) is Scotland’s national framework for lifelong learning and is one of the oldest formal frameworks in the world. The SCQF is an inclusive framework for all forms of qualifications and learning (formal, non-formal, academic, and vocational) reflecting that there are diverse pathways of learning (Dunn, 2022; SCQF Partnership, 2024d). The SCQF provides a framework for learning throughout life (from pre-school to doctoral level) and seeks to “show learners and others potential routes to progression and credit transfer” (Dunn, 2022, 47). Reflecting this inclusive approach, currently 8% of qualifications registered in the SCQF Partnership database (SCQF Partnership, 2024a) are offered outside of formal education institutions and national award bodies. Most of these qualifications would be considered alternative credentials, or micro-credentials based on the definition of QAA Scotland (2022). These qualifications reflect that the SCQF allows non-educational organizations to have their training evaluated against the five characteristics of the SCQF criteria. This process, called “credit-rating,” evaluates the learning (and the assessment of that learning) to indicate the SCQF level of the training, as well as a recognition of the learning hours; one credit is based on 10 notional learning hours in Scotland (Dunn, 2022; SCQF Partnership, 2022). This evaluation is conducted by approved Bodies - all Scottish universities and colleges can, along with approved ‘SCQF Credit-Rating Bodies’ – organizations that have been approved by the SCQF Partnership, such as Scottish Qualifications Agency, and other Professional Organizations, e.g., Scottish Fire and Rescue Service and Scottish Police College (SCQF Partnership, 2024e). Figure 1 below outlines the top-level process of credit-rating of learning, and Table 1 summarizes key terms used in this study.

Figure 1. Top-level outline of credit-rating process between learning provider and CRB (Credit-rating body that include Scottish universities and colleges and select other organizations).

Currently, there is a lack of contemporary evidence around how “credit-rating” of learning courses are supporting skills development in Scotland and globally; only one Scottish Government report describing how the SCQF can be used for community learning and development was found (Scottish Government, 2008). Therefore, the objective of this study examines the quality assurance mechanisms and benefits of such a collaborative system of formal learning assessment within Scotland, using one Scottish university (as an approved learning assessor/SCQF Credit-Rating Body) and learning providers in the digital services sector. Its contribution is to provide an exploratory and contemporary evaluation of credit-rating of learning at one Scottish University, thereby establishing benefits to the university and learning providers and how credit-rating supports national priorities.

The research question was “what are the benefits of having a flexible national qualification system (SCQF) that allows ‘credit rating’ of organizational learning?” This question was answered by examining the drivers and practices at one Scottish University—Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU).

This study first reviews drivers for alternative forms of credentialed learning, before outlining the qualitative, exploratory methodology adopted for this research. The findings from a thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews are presented, before discussing the implications of these findings for GCU, the Scottish tertiary education more broadly, as well as wider societal considerations.

Considering the exploratory research question that seeks to understand the value and benefits of credit-rating of learning, then this review of existing literature and practices considered (1) the drivers for lifelong learning in a contemporary, professional, and international landscape, (2) a synthesis of literature to analyze the advantages of adopting a flexible approach to national qualifications and credit-rating of organizational learning in the Scottish context, and (3) outlining the arrangements in place for third-party credit-rating of learning as outlined by the SCQF Partnership and as embedded at GCU.

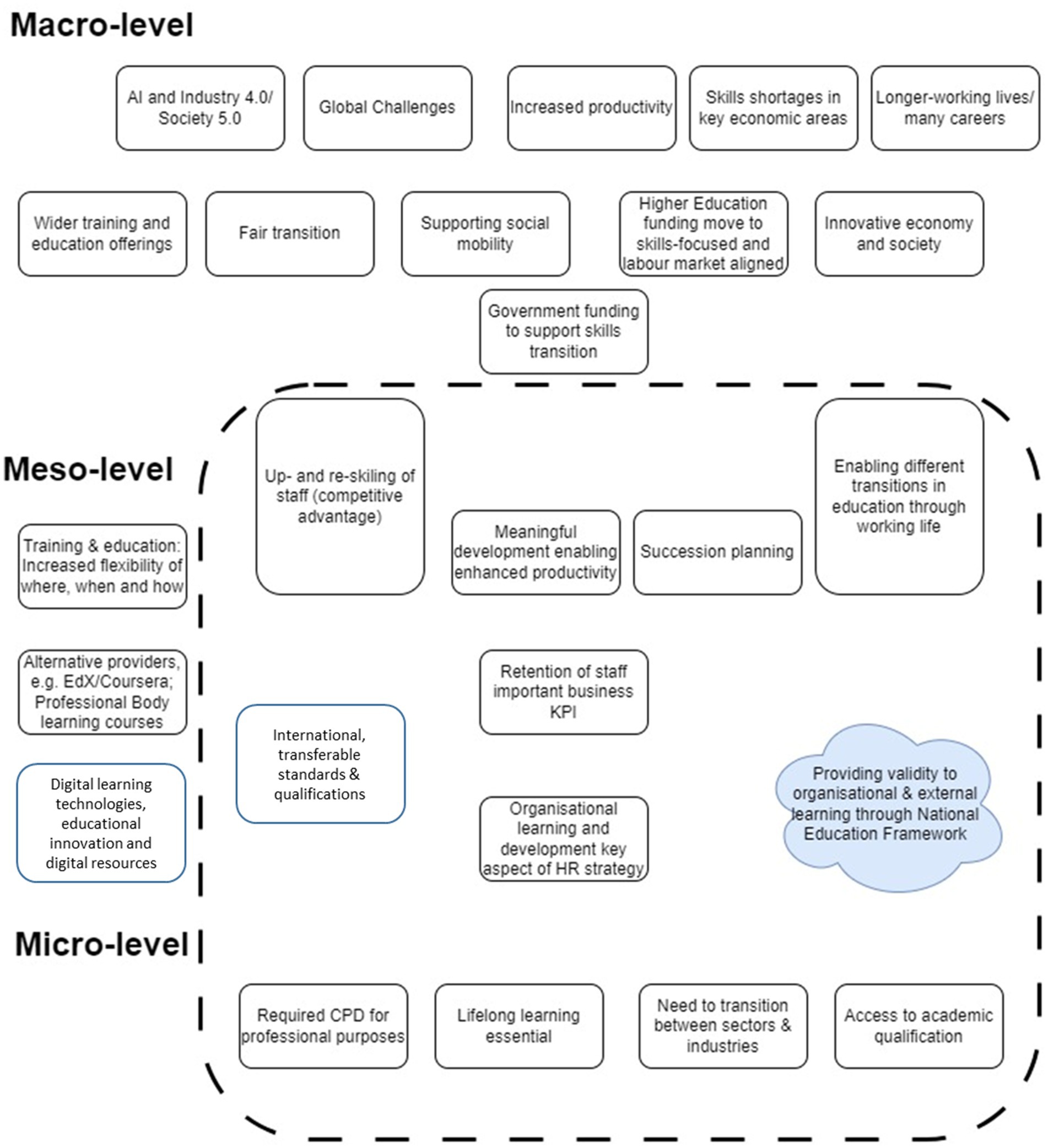

There are different drivers across the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels that create a need and market for diverse forms of up-and re-skilling learning (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2018; Valenti, 2021; World Economic Forum, 2020, 2023, 2024; OECD, 2024; European Commission, 2024b) that Figure 2 summarizes. Some key aspects of these drivers are explored below that provide relevant contextual background as to the increasing need for flexible, high-quality alternative credentials.

Figure 2. Drivers across macro-, meso- (institutional), and micro-levels for credit-rating of organizational learning.

Technology has been both a driver and an enabler of up-and re-skilling approaches over the last 30 years (Mamaghani, 2006; Nizami et al., 2022; Morandini et al., 2023; Balch, 2024), with an acceleration seen in response to COVID-19 (McKinsey, 2021; Li, 2022; White and Rittie, 2022). In recent years, the widespread, public availability of generative AI has brought new opportunities (such as enhanced productivity, up-and re-skilling for new roles and new skills) as well as disruption to the marketplace. These emergent technologies also offer the potential to provide mass personalization along with the required, adaptive quality assurance systems. However, it is bringing challenges, such as traditionally lower-skilled roles being at greatest risk of being replaced by AI or automation (Gallagher, 2022). So, the need for fair transition, as traditional roles are displaced by technology, is recognized. A similar opportunity for green transition exists, with equivalent role displacement challenges (Kyriazi and Miró, 2023; Arabadjieva and Barrio, 2024). If done correctly, then new approaches for up-and re-skilling have the potential to enable social mobility and support workforce development and redeployment (Campo et al., 2024). Post-COVID responses from different governments and pan-national institutions provided appropriate stimulus to help those in lifeboat careers, showing the potential of a coordinated approach with financial stimulus and innovative responses (Pisu et al., 2021; ILO, 2024), including short courses, micro-credentials, and alternative credential offerings. Since COVID-19 there is increased focus on lifelong learning with associated funding and schemes (CEDEFOP, 2021; Lands and Pasha, 2021; Scottish Funding Council, 2022; European Commission, 2024a), although some post-COVID stimulus packages have been discontinued (Ross, 2024) potentially weakening the national lifelong learning ecosystem. So, the factors outlined in Figure 2 are dynamic.

Companies and enterprises recognize the skills gap in their organizations and the lack of supply is encouraging examining alternative approaches, such as looking more at skills in recruitment and professional development (Baird et al., 2021; McKinsey, 2022). This change in ‘demand’ encourages innovative approaches and business models, such as micro-credentials and alternative credentials internationally (Baird et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2021; Selvaratnam and Sankey, 2021; Australian Government, 2022; Braxton, 2023; Tamoliune et al., 2023; Bauer et al., 2024; Iatrellis et al., 2024). However, this commodification of education can lead to inequality in access and barriers to transform learners’ social and economic potential. Moreover, commodification risks devaluing credits through oversupply (Tomlinson and Watermeyer, 2022); this oversupply and lack of explicit and implicit quality mirrors the emergence of professional IT certificates in the 1990s (Gallagher, 2022). Consequently, for recruiting managers, organizational development professionals, and employees, credentials that have recognized standing add value; this recognition can be through brand-sharing (e.g., from educational institution), formal benchmarking, and alignment to national frameworks.

While different forms of alternative credentials exist, micro-credentials have received a lot of attention in recent years (Brown et al., 2021; Ahsan et al., 2023; Varadarajan et al., 2023). Brown et al. (2021) highlight that, while there are international definitions of micro-credentials (European Union, 2022; UNESCO, 2022), the lack of shared understanding creates barriers to wider adoption. Brown et al. (2021) also highlights different national approaches—across Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Canada, USA, Netherlands, Italy, and European MOOC Consortium. At the heart of these approaches is often a stable National Qualifications Framework, with associated quality assurance standards and systems that enable the emergence of micro-credentials. Of note, some definitions imply micro-credentials are from a trusted body, so may maintain the status-quo of only being provided by existing education institutions and not facilitate more innovative business models.

The above section outlined international considerations and examples that set important background context for credit-rating of organizational learning. Focusing now specifically on the Scottish context, an exploratory scoping of literature was conducted to examine the advantages of adopting a flexible approach to national qualifications, focusing on the SCQF as a case, and specifically considering credit-rating of organizational learning in the Scottish context. Four key themes emerged from this review: (1) Enhancing Workforce Development and Employability, (2) Facilitating Lifelong Learning and Continuing Professional Development (CPD), (3) Promoting Inclusivity and Widening Participation, and (4) Supporting Innovation and Adaptability in Education and Industry. Each theme is explored through critical insights, analysis, and discussions drawn from the literature, providing a comprehensive understanding of the benefits of flexible qualification systems like the SCQF.

Scotland, with its devolved government, sets out national priorities (Scottish Government, 2024a), and together with other organizations (such as local government, employer groups, and labor unions) set out regional development plans to grow local economies and societies (SHRED, 2024). These plans highlight particular skills required and actions to address these (Skills Development Scotland, 2024). The need for targeted learning in recent years by the Scottish Government saw a national upskilling fund (Scottish Funding Council, 2022), with a range of credentialed and non-credentialed responses adopted from more lifelong learning courses offered by some institutions, and others offering credentialed courses aligned to skills gaps; of note, similar approaches were seen in different countries (BCG, 2024). Unfortunately, these ring-fenced monies were removed from the 2024/25 Scottish Government budget, (Scottish Funding Council, 2024) removing a financial enabler for universities and colleges to offer micro-credentials and alternative credentials. In addition, the UK-wide Apprenticeship Levy has encouraged education programs more aligned to the workforce (UK Department for Education, 2023). In Scotland, thirteen Graduate Apprenticeships Frameworks have been approved aligned to key needs of economy (Apprenticeships Scotland, 2024).

The increased offerings require a clear benchmark to support employers in making sense of the level and amount of learning. In this context, flexible national qualification systems like the SCQF play a crucial role in enhancing workforce development and employability. By providing a framework for recognizing and accrediting both formal and informal learning experiences, these systems enable individuals to demonstrate their skills and competencies to employers effectively (SCQF Partnership, 2024d). This recognition of prior learning (RPL) is particularly valuable for individuals transitioning between sectors or seeking to re-enter the workforce after a period of absence, such as in veterans and refugees (Scottish Government, 2024b; SCQF Partnership, 2024c); RPL in this context can also be called credit transfer.

Specific to this research, the flexibility offered by systems like credit-rating allows individuals to pursue personalized learning pathways tailored to their career goals and aspirations. This personalized approach to education and training not only enhances motivation and engagement, ensuring that individuals acquire the specific skills and knowledge demanded by employers in various industries (Shemshack and Spector, 2020), but also enables students to choose their learning’s content, pace, location, and method flexibly. This flexibility addresses vocational challenges in education (Brennan, 2021), and it can lead to constant innovation and optimization of curriculum structure, and teaching and learning strategy thus improving the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of education services by catering to individual learning capacities and achievements (Martin and Furiv, 2022).

However, while flexible qualification systems can enhance workforce development and employability, challenges exist in ensuring the quality and consistency of learning outcomes. As discussed above, the proliferation of micro-credentials and short courses, often offered by non-traditional providers, raises questions about the comparability and rigor of qualifications (Brown et al., 2021). In addition, employers may still prioritize traditional qualifications over alternative credentials, leading to issues of recognition and acceptance in the labor market (McGreal and Olcott, 2022).

One of the key advantages of flexible national qualification systems like the SCQF is their ability to facilitate lifelong learning and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) (Behringer and Coles, 2003). Lifelong learning is increasingly recognized as essential for maintaining relevance and competitiveness in today’s rapidly changing world (Jackson, 2011). Recent Scottish Government commissioned reports (Scottish Government, 2023a, 2023b) highlighted the need for a lifelong and skills-focused approach, including a lifelong national education identifier. These reports highlighted the critical, enabling role of the SCQF in recognizing all forms of learning (informal, non-formal, and formal). Specifically, by providing mechanisms for the recognition and accumulation of credits across various learning experiences, the SCQF encourages individuals to engage in continuous learning throughout their careers (SCQF Partnership, 2015). However, there are challenges to achieve this within the Scottish context, including a lack of unique lifelong identifier to which all forms of learning could be (digitally) attached; this is not a uniquely Scottish challenge.

Furthermore, the credit-rating of organizational learning allows employers to support the professional development of their employees more effectively as learning involves the recognition and accreditation of learning outcomes attained within organizational contexts (Eraut and Hirsh, 2010). By accrediting in-house training programs, workshops, and other learning activities, organizations can demonstrate their commitment to employee growth, skill, and talent development (CIPD, 2023). This, in turn, contributes to higher levels of employee satisfaction, retention, and productivity, while fostering a culture of continuous improvement (Sypniewska et al., 2023).

However, challenges may arise concerning the accessibility and affordability of lifelong learning opportunities, particularly for individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds or underrepresented groups (Pennacchia et al., 2018). Moreover, the rapid pace of technological change necessitates frequent updates to qualifications and learning pathways, posing challenges for both learners and educational institutions in keeping pace with evolving skills demands (Jagannathan, 2021). A flexible national qualification system allowing credit-rating of organizational learning can bridge the qualification gap between labor market supply and demand, promoting vocational training, facilitating lifelong learning developments (European Training Foundation, 2016), and thus optimizing organizational human capital investment and professional development.

Flexible qualification systems, like the SCQF, have the potential to promote inclusivity and widen participation in education and training by promoting lifelong learning through assisting ‘people of all ages and circumstances to access appropriate education and training over their lifetime to fulfill their personal, social, and economic potential’ (SCQF Partnership, 2015). By recognizing a broader range of learning experiences, including work-based learning, and formal and informal learning, these systems validate diverse forms of knowledge and expertise and enhance employability (Morley, 2018). This can be particularly beneficial for individuals who may have non-traditional educational backgrounds or limited access to formal learning opportunities.

Moreover, the SCQF’s emphasis on credit accumulation and transfer facilitates smoother transitions between different levels of education and training and between employment sectors, thus reducing barriers to progression and promoting social mobility and inclusion (SCQF Partnership, 2015). This is especially important for individuals seeking to upskill or re-skill to adapt to changing labor market demands or pursue new career pathways. Furthermore, credit-rating organizational learning enhances the transferability of skills across sectors and promotes collaboration between education and industry stakeholders (European Commission: Directorate-General for Employment, 2011). The potential to individuals of having credentialed learning, referenced to the SCQF, brings international portability of the learning and credentials (through alignment to other National Qualifications Frameworks), promoting geographic mobility, in addition to potential economic and social mobility.

However, despite the potential for inclusivity, challenges persist in ensuring equitable access to flexible qualification systems. Socioeconomic inequalities in access to educational resources and support services may perpetuate existing disparities in educational attainment and employment outcomes (Ainscow, 2020). In addition, issues of recognition and portability of qualifications may disproportionately affect individuals from marginalized or underrepresented groups, further exacerbating inequalities in the labor market (Office of National Statistics, 2017).

Flexible national qualification systems like the SCQF also play a vital role in supporting innovation and adaptability in both education and industry. By allowing for the recognition of emerging skills and competencies, these systems enable educational institutions and employers to respond more effectively to changing economic and technological trends (Scottish Government, 2022; SCQF Partnership, 2022). This flexibility is particularly important in dynamic sectors such as technology, where traditional qualifications may quickly become outdated. Furthermore, flexible national qualification systems can enhance benchmarking and standards for education on a country level, promoting acceptance by various stakeholders and improving educational outcomes. In addition, they can be used as reference points for comparison such as relevant occupational or professional standards (SCQF Partnership, 2017, 2019).

Moreover, organizational learning encourages a culture of innovation within organizations as employees are incentivized to engage in continuous learning and knowledge sharing. This contributes to increased organizational agility and competitiveness as companies can more readily adapt to new market conditions and opportunities by enabling the rapid deployment of new skills and knowledge, emphasizing enhancing professional competence to meet industry demands (Achdiat et al., 2023). In addition, a national system (credit-rating of learning) to benchmark learning against the SCQF can nurture alternative learning providers and provide a richer, quality-assured ecosystem of learning with the required diversity to meet individual, business, industry, and societal needs.

However, challenges exist in ensuring that flexible qualification systems remain responsive to emerging skills needs and industry trends. The process of updating and revising qualifications can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, leading to potential delays in aligning curricula with evolving demands (OECD, 2020b). In addition, concerns have been raised about the role of industry stakeholders in shaping qualification frameworks, with some critics arguing that corporate interests may prioritize short-term skills needs over broader educational objectives (European Training Foundation, 2012).

The Scottish Credit and Qualification Framework exemplifies the benefits of adopting a flexible approach to national qualifications and the credit-rating of organizational learning. This exploratory review of literature has illustrated the multifaceted benefits of flexible national qualification systems that incorporate credit-rating of organizational learning. They play a pivotal role in addressing the evolving needs of both individuals and organizations, promoting lifelong learning, enhancing vocational training, up-and re-skilling for sustained employability, and optimizing educational outcomes through innovations and adaptations to contemporary challenges. Challenges do exist, around inclusivity (price and overcoming any hidden barriers), keeping pace with technology and keeping courses up to date to meet market and learner needs, as well as navigating the plethora of possible courses, their different purposes, and how clearly these are understood by learners and employers alike.

Importantly, the above literature review highlights that an adaptive, innovative, and collaborative system of learning provision can meet the needs of a range of stakeholders, namely, national policy, and practice, together with educational institutions and organizations co-creating value for learners with high-quality, internationally recognized, and transferable learning.

The Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework Partnership (SCQFP) guidelines establish key principles for credit-rating, ensuring consistency, standardization, transparency, and quality across educational institutions (SCQF Partnership, 2015). All universities and colleges in Scotland, including GCU, are empowered to assign credit-ratings to qualifications in alignment with these standards, although not all choose to do so; these institutions are called ‘SCQF Third-Party Credit-Rating Bodies’ (CRB for short). The business model by which each CRB does this is determined by each institution, aligned to their strategy and quality assurance policy and procedures. Of note within the Scottish Higher Education sector, then a collaborative, enhancement-led approach has been used for many years (QAA Scotland, 2024a). The most recent national approach—Tertiary Qualifications Enhancement Framework—and its associated review process will enhance the role of the SCQF Partnership in determining best practices and knowledge sharing across Third-Party Credit-Rating of Learning (QAA Scotland, 2024b). GCU adopts an enhancement mindset to credit-rating, so looking to support the learning providers through a value-add, long-term approach.

To ensure compliance with academic standards and support students in achieving recognized qualifications, GCU rigorously follows SCQFP principles, embedding them into our quality assurance processes (Glasgow Caledonian University, 2022). GCU’s credit-rating guidance, available through the university’s academic resources, adheres to these principles, providing a clear framework for evaluating and awarding credits in accordance with SCQF levels. Further details can be accessed through the SCQFP and GCU’s official guidance documents.

The lack of extant literature evaluating credit-rating in Scotland, as outlined in the introduction, necessitated an exploratory methodology (Thomas and Lawal, 2020). To gain insights into the value, benefits, and operational aspects of credit-rating, a qualitative methodology was adopted to allow rich insights from a range of stakeholders to be gained. A single case study method was adopted (Bao et al., 2017; Gustafsson, 2017; Yin, 2018), which focused on the credit-rating activities of GCU. A case study method was adopted, as within this exploratory design and reflecting the standard principles that all institutions credit-rating of learning must follow, then the review of one formal tertiary level education institute in Scotland can highlight relevant practices in the Scottish university sector.

Credit-rating at GCU is organized through the Institute for University to Business Education (GCU, 2022) that has delegated responsibility to manage the commercial as well as the academic quality assurance processes; oversight is provided by the university’s central Quality Assurance and Enhancement (QAE) department. GCU is a modern Scottish University with a successful history of widening access and offering innovative education to lifelong learners and workplaces.

Semi-structured interviews focused on four areas: (a) what interviewee took credit-rating of learning to be; (b) what were the benefit and value of credit-rating of learning (to learners, business, organizations, and GCU), (c) how did the organizations start working together, and (d) views on the quality assurance processes. The focus on these four areas reflected the desire in this exploratory research to understand (a) how credit-rating is conceptualized among stakeholders, (b) what drivers and value are there to credit-rating (key aspect of the research question), (c) the ease of access to this service and reflecting collaborative aspect, and (d) how the service provides the required quality-assured standards. Interviews were conducted with nine (9) stakeholders—five internal to the university covering business, academic, and quality assurance roles and four external to the university (so four different learning providers). A purposive sampling strategy (based on 21 clients) was adopted to give a coverage of different perspectives, such as business, academic, and quality assurance (within the university), and learning providers that are stand-alone businesses providing learning to specific markets, as well as providers working within a wider organization. All participants have had recent experience within GCU credit-rating activities and, for external organizations, are currently credit-rated by GCU and have been for at least 18 months. Some learning providers were excluded as either being new clients, or the scale of their current offering having fewer learners.

MS Teams-based interviews lasted between 38 and 57 min, with an average of 48 min. The transcript of the recorded interviews was verified for accuracy, before being inductively coded by one of the researchers with reference to the research question. Subsequently, the second cycle analysis—thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2021)—was conducted by one of the researchers, with final analysis and interpretation being discussed by all authors.

Ethical approval was granted for this research by GCU ADSL/IU2B Ethics Committee (23 February 2024), and the ethics protocols were followed in conducting this research.

The authors acknowledge the methodological limitations of this research, namely, one institution and the use of a purposive sampling. In this exploratory research, the intent was to determine a diverse set of benefits of credit-rating of learning, and the findings from the nine interviewees did provide a wide-range of benefits, as well as highlighting areas of consensus and disagreement. In addition, considering the lack of existing research around credit-rating of learning, the findings of this research provide new insights into this important part of the Scottish Education system.

The analysis of the interviews resulted in five key themes, around (1) the importance of the national qualifications frameworks, (2) value to the learners, (3) value to the learning providers, (4) value to university and how its business model influences this, and (5) areas for future enhancement.

The Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF), Scotland’s National Qualifications Framework (NQF), together with a well-defined national system for credit-rating of organizational learning provided by the SCQF Partnership was highlighted as being an important enabler:

it's not just … the SCQF, obviously there's a framework, but there's obviously the specific SCQF guidelines that Credit Rating Bodies have to follow … 25 plus principles (P7)

This national system means that universities and colleges (termed as ‘Credit-Rating Body’ in this context) are allowed to credit-rate learning for organizations bringing their expertise in quality-assured learning:

So, they come to a university or another institution like ours, who's a credit rating body, and they get that benchmark and that quality assurance from us. (P3)

They [SCQFP] published the guidelines, they expect institutions to adhere to these guidelines when they go through these processes, so it's up to us to ensure that we meet the rigor of their guidelines and anything that we do so that we don't fall short of what the expectations are. (P7)

The presence of a national system in itself is not sufficient, but it was highlighted that Scottish universities being perceived as business-orientated, “Scottish universities are by far the most business orientated so … there’s less red tape” (P5), while offering a robust quality-assured process.

For some of the learner providers then credit-rating of their learning is essential as it provides mapping to the European Qualifications Framework, which provides portability across nationally defined qualifications frameworks:

People walk into the shop on the website, and we have to say things that make credible sense to the people who are looking for whatever we have to sell. … And then we also have a couple of logos that say these are, you know, GCU is supporting us, and we're mapped to the European Qualifications Framework. (P5)

This international portability is not relevant for all providers, but the credibility of externally quality-assured learning is, “I think the [credit rating] brings credibility to this [learning offering] … I mean the benefits [of credit rating] are huge” (P1). Of note, not all countries have a NQF and have different naming conventions, which means that the name of the credit-learning is geographically sensitive:

We found out that you can't call it a diploma in the US, they don't go for the diplomas. … diploma means something completely different. You have to call it a certificate in the US. (P5)

Together, the SQQF and credit-rating guidelines appear to play a key enabling role, along with the business and community alignment of Scottish universities.

There is a significant recognized value of credit-rated learning programs, as these programs are aligned to professional development needs, “so it enables us to design professional learning that is absolutely rooted in … practice” (P1), and this is often because “many high profile clients that we have, they have a well-developed advisory boards” (P4). This awareness of industry needs and trends ensures learning offered is contemporary:

So, we're constantly having to update our curriculum based on changes within the industry and that needs to be the case … we're constantly innovating, as new modules, as you're adding new certs, and we can all do that by being connected with industry and connected with students (P6).

Moreover, the learning providers provide flexible access to learning at a Higher Education level to support their professional development, “it’s a structured approach for re-skilling and up-skilling. In such a way that is 100% manageable … by the students in terms of time, resource commitment, work life balance” (P4). This recognizes that for some students, that “they are probably not at the point where there may be ready to invest in a Masters or they do not need to at this stage, but … if I invest in this experience with [company], that I can potentially down the line, put that against another qualification” (P6).

This access to other Higher Education courses and programs that credit-rating brings was acknowledged by other interviewees:

These [credit-rated learning] modules … can be used as part of an RPL [Recognition of Prior Learning] process. … because the student studies only say anything from 10 to 30, 40 credits, you cannot expect to RPL the entire year, but there will be some form of recognition (P4).

We would get a lot of questions around how can they transfer credits … can I build up credits (P6).

Some of our clients … use the credit rated program as a bridging course for students to come to GCU and study one of our Masters programs (P4).

However, not all participants indicated that they felt that this was useful, “I think of the thousands of students that have graduated well, I only know a handful that have actually asked about … how could I apply these credits to something else?” (P9).

The external quality-assured nature of the credits is important to learners as they decide which learning course to choose, “some of the emails we get through the credit rating inbox, which will say I’m thinking about doing this course with this organization. They say that you accredit it, (for a kind of layman’s term) … Is that true?” (P3). In addition, the ongoing quality assurance of the learning is important to learners:

[It’s] really important to them to know that we have that quality assurance in place on top of, OK we've got the credit rating, but we're also getting regularly quality assured to make sure that our, particularly that our assessments, are of a certain standard

This nationally (and internationally recognized) credit is often important to learners but not always the key motivation, “it’s [mapping to EQF] a mix of do we sell that as a value proposition or does the customer see it as a value proposition? And I think it’s probably a mix of both” (P5). However, the ability to share their achievements professionally is of value to successful learners, “It’s all about social proof … they take the qualifications they get from us, and they put it on to their LinkedIn. So now that they are saying this is important to me, and by virtue of the fact they say this is important to me, it’s important to, for them, to tell others” (P5).

In addition, completing the credit-rated learning course supports career transitions as well as building confidence in learners who already were working in their field:

A lot of people coming from kind of adjacent industries, … that they think there is a better future and higher earnings potential and more security by switching into and by taking those skills adding [FieldA] onto it … and then the people from all sorts of backgrounds nurses, security guards, policemen, teachers. (P9)

There could be people who’d be working in [FieldA] for years because … they're not qualified they kind of feel like, I’m not sure if anybody's listening to me, but somehow magically they have this qualification and they feel like … people are listening to you more in the meetings (P9)

As already mentioned above, the benefits for the learning providers include recognition of their learning on SCQF and the international equivalency and portability that this brings. Moreover, credit-rating of learning offers pathways into university programs. In addition, credit-rating brings further credibility to the offering of the learning provider:

idea, concept, package, program, whatever you want to call it that they could have potentially delivered on their own however they want you to garner a bit more brand, a bit more, kudos, credibility and therefore they wanted to partner with us to, get themselves, get it credit rated, but also to have that GCU stamp of approval (P2).

It’s really about customer focus and the customer looks at us and says ‘are these guys reputable?’ and the University accreditation helps us with that reputation (P5).

For some learning providers, credit-rating is essential due to the nature of training that they provide.

Our students are educators themselves … so they understand the credit system, the European credits and how they transfer … It's a cornerstone of what we do. It adds huge value … I think it's probably important to say that it [credit-rating] … is a fundamental part of our business. … we wouldn't have a business without credit-rating, that's the reality of it (P6).

Whereas for others, the credit-rating aligns to supporting staff within their own organization in their professional development and the impact that this learning has, including them becoming change agents within their own organization:

The [manager] told me that [it] is the confidence and knowledge those [practitioners] bring back with them and how to change practice to make it work better for [their users] (P1)

One [practitioner] that I spoke to was now doing stuff across the [wider organization] (P1)

The ability for internal organizational development professionals to support their colleagues to access credit-bearing learning is another key driver as this meets professional requirements, “there’s no free Masters level provision for [profession], anywhere in Scotland that I can find right now” (P1).

Another noted value to learning providers of credit-rating their learning is that it enhances their own offering and quality assurance of that learning:

We go through the rigor because we know that's important to you guys [GCU], but it's also important to us. So, we just embed that in and that's part of the business relationship (P5).

the annual audit … we find that really constructive as well … I guess what we find to a certain extent is preparing for the audit … it helps us with our own timetable for the year … a conversation around where we are, what the gaps might be, getting access to some of our students as well. So, it's a very it's a very positive experience, but it's rigorous (P6)

Finally, the model of credit-rating of learning means that the learning provider retains ownership of their learning materials, which is important as “dual ownership … where the university would and the [OrgX] might have joint ownership over the curriculum, and it just does not work … it does not give you the flexibility in the agility and the ownership piece” (P6).

Credit-rating is a strategic choice for any university to engage in, and in the case of GCU aligns to its vision and strategy, as “credit ratings we do would very much fit the Civic University” (P2) and its “complementary [to our traditional programs] because it supports that kind of lifelong learning partnership approach” (P3). Moreover, GCU as the leading Scottish university for widening access to Higher Education, then this is an alternative form of widening access, as “it gives opportunity to people to get some form of qualification. So, you might say we are widening access” (P4) that offer pathways into GCU programs or other Higher Education programs, as mentioned above.

It was clear also that participation in credit-rating offers benefits to the university that range from sharing expertise, gaining new insights in your discipline, and bringing examples (with permission) back into GCU teaching:

I do think GCU do learn a lot from some of the practices that we would have around that. So equally we learn a lot from standards around the assessment (P6).

As a university, we can learn quite a lot from that as a specialist in an area. So, if you're already a subject matter expert in an academic school, you might not be getting exposure to that, and you wouldn't see the back-end workings (P3).

So, we had a wonderful opportunity on the day we credit rate [providerA] to learn some latest developments in the field, some new theories and requirements in the area … I used some of the discussions, some of the examples shared with us during the day as examples in my teaching for [modules A and B] (P4).

It was acknowledged that this engagement with learning providers allows GCU to meet Scottish Government priorities:

I think it's important to give recognition to external organizations … to say that what learning you're doing is of high value and is of importance. So, I think that it’s meeting the demand that Scotland's looking for in terms of the workforce … I suppose it's giving a gateway to these external organizations to meet the Scottish Government aspirations (P7).

Furthermore, the business model adopted by the university in credit-rating of learning is seen as contributing to the success, whether this is (a) how the process of credit-rating is communicated to interested learning providers, (b) how decisions are made around whether credit-rating is of mutual benefit at the time of enquiry, (c) the ongoing relationships management, and (d) how to provide credit-rating in a robust and effective manner. One learning provider indicates that the business model for mutual benefit is important and that GCU is viewed as a current benchmark:

How would you actually deliver lifelong learning? Like, what does it actually look like from a CPD perspective? And I think you know also that universities are going to be at the cornerstone of it. But I think for universities to do it properly … they need to look at their partnership model … How do we make sure that we're meeting is in a really flexible manner and that's why I just think that this particular model, that GCU have is, is really a really strong benchmark and a good use case study of how it should be done (P6).

There is some flexibility required in the business model, and when it works, credit-rating is viewed as mutually beneficial, “So the ability to have programs credit rated, it feels more like a partnership” (P1). However, it is critical that the mutual value is recognized and that this is explicitly recognized within any ongoing commercial relationship.

The interviews identified that credit-rating does bring value to the different stakeholders. However, there were areas that were identified to enhance credit-rating. First, it was acknowledged that the term ‘credit-rating’ may be confusing and hinder wider adoption of credit-rating:

So, I think the terminology around it [credit rating] … it's still very academic and a little bit old and we could do with finding a different way to communicate that … more customer centric and that means more to the outside world … I think it [term credit-rating] creates potential barriers (P3)

I do believe we need to come up with a more catchy term. In the near future, especially if we're going to grow the business (P4)

In addition, one of the interviewees (P8) highlighted there is a potential for confusion around learner’s understanding of the professional standing of non-credentialed courses and credentialed courses; credentialed courses included credit-rated learning courses.

This lack of awareness and appreciation needs to be addressed, due to the changing nature of lifelong learning in Scotland (as in other countries)

[in development of] micro credential framework for Scotland … a key part of the discussion is around you won't just necessarily register to do a full-time masters in one year, you might actually want to just come and do a bit of something, and then come back (P7).

Credit-rating is one option to respond to this opportunity, as “it’s a model for rolling out these [micro-credentials], for getting credit rating to industry in a flexible manner without probably pulling in a huge amount of resources within the university itself” (P6). In addition, it is important that in this more flexible, lifelong learning system that pathways are more clearly signposted to GCU programs, or more flexible learning programs, “I think more could be done on creating visibility on pathways, … either across universities or within universities are from providers into universities” (P6). This deeper connection and opportunities for synergies are a further area for development,

We [GCU] are creating leaders of the future who are then going to be looking to organizations like this [learning provider H], potentially for some of their organizational training and development needs, … it can develop the pool of demand if we introduce it to them as a student … I think it would add to the benefits of why we do this and what it brings to the institution (P2)

so how could we go from a situation where GCU is credit-rating and auditing our courses to, to the extent that we could start working more … in a partnership model, maybe in terms of curriculum just, … students maybe being transferred to courses on GCU that they might be interested in? (P6)

This deepening relationship touches on another area for enhancement, which relates to how GCU more systematically diffuses insights gained from credit-rating into the wider organization.

The findings from the interviewees highlighted that there is a positive and clear value to a range of groups: (1) to individual learners who are looking to up-and re-skill and transition into new careers through high-quality learning, completing a course that is registered on the SCQF which then has alignment to other international National Qualifications Frameworks (such as the EQF), (2) to universities (Credit-Rating Bodies) and their civic responsibility, as credit-rating of learning widens access to high-quality professionally aligned learning (which in turn matches to the priorities of the Scottish Government and employers within Scotland), and (3) to the learning providers in further enhancing the credibility of their offerings, improving their courses through refined development and quality processes, as well as bringing international recognition (through alignment to the SCQF) and portability to progress onto further formal education.

Therefore, credit-rating of learning aligns to the purpose of the SCQF’s purpose as outlined in Section 1, namely, “to show learners and others potential routes to progression and credit-transfer” (Dunn, 2022, p. 47) and to facilitate lifelong learning (Behringer and Coles, 2003). Moreover, it provides a flexible route for learners to up-and re-skill at a pace and time that is appropriate to them (Brennan, 2021) and has benefits to sponsoring organizations in terms of workforce development. In addition, learning providers (such as EdTech companies) can respond more rapidly to these individual and organizational demands and that the credit-rating route provides a flexible, responsive route to get their courses registered on an internationally recognized National Qualifications Framework, such as the SCQF through the SCQFP (SCQF Partnership, 2024b). Also, the independence of the SCQFP that manages the SCQF appears to be an important enabler, as this independence allows them to recognize that meaningful learning takes place across different organizations, and not just in formal education institutions. Together with the clear principles and guidelines on credit-rating of learning support, CRBs (universities and colleges) provide a structure for alternative forms of credentialed learning to emerge.

The research identified also that there is confusion around the term credit-rating and an improved understanding of this term across a range of stakeholders (education, employers, lifelong learners, and citizens) would be beneficial to see a wider adoption and engagement with credit-rating of learning. While some believed that a more learner/business-friendly term would be beneficial, other participants argued that credit-rating gave gravitas to the process and its outcome, so further consultation around this would be required. What is acknowledged is that wider understanding of credit-rating of learning would be beneficial to lifelong learners, employees, employers, and society more generally to meet workforce needs.

Importantly, the research highlighted that the business model adopted by the Credit-Rating Body (GCU in this instance) is a key consideration. A stream-lined process of initial engagement and then credit-rating with clear criteria and guidance allows an efficient, but robust process. The autonomy of GCU in defining this process, aligned to SCQFP principles for credit-rating of learning (SCQF Partnership, 2015), recognizes the flexibility that the arrangements around the SCQF allow, and the benefit of such an approach. Each CRB needs to ensure that its business model recognizes the value proposition of credit-rating generally but equally recognizes the value co-creation that is created through credit-rating of a learning provider’s learning. Furthermore, the alignment of the CRB’s institutional strategy to the purpose and value of credit-rating is another important enabler. The operationalization of this strategy needs to allow mutual recognition of value through the credit-rating process—that the university is benefiting from offering this service, as is the learning provider and that together value is being co-created. In fact, the findings highlight that there is potential for further shared value, such as clearer pathways beyond the credit-rated learning course that would align to national priorities (such as widening access, supporting fair job transition due to macro-environment and industry-specific changes).

This exploratory research had the research question, “what are the benefits of having a flexible national qualification system (SCQF) that allows ‘credit rating’ of organizational learning?” The research identified a number of benefits and value to individual lifelong learners, to the university (GCU in this case), and to the learning provider whose learning courses are being credit-rated.

• For Lifelong Learners: The SCQF’s flexible framework offers learners a wider variety of accredited courses, allowing them to pursue personalized learning pathways that align with career goals.

• For Universities (e.g., GCU): The ability to credit-rate external learning enhances the university’s role in the broader educational ecosystem, improving its attractiveness to both learners and potential partners.

• For Learning Providers: The process of credit-rating helps external providers enhance their credibility by having their courses recognized within a structured national framework, thus attracting more learners.

These benefits emanate from a flexible national qualifications framework (SCQF) that enables and recognizes high-quality learning can come from a range of providers and that a diversity of choice for learners strengthens the overall provision of education available. The SCQFP guidance around credit-rating allows Credit-Rating Bodies (CRBs), such as universities, to credit-rate a learning provider’s learning in a robust manner, resulting in that course being registered on the SCQFP database at a particular SCQF level and with a number of credits (equating to a number of intended learning hours). The de-centralized approach allows each CRB to develop their own business model so long as it fulfills the guidance of the SCQFP, and the findings indicate that developing and sustaining an appropriate business model enables mutual benefits for the CRB and for the learning provider.

This exploratory research used a purposive sampling of participants to determine initial themes around benefits, so the number of participants represents a limitation of this research, as well as using one CRB (university). In addition, this research did not engage with learners or sponsoring organizations, a critical gap for understanding the full value of credit-rating from a learner’s perspective. Further research is required to address these limitations and the emergent findings:

1. Expand Sample Size and Context:

• Broaden the scope of the study to include more CRBs, including private and non-university providers.

• Include participants from diverse educational sectors to validate whether the benefits identified in this study are applicable in other contexts.

1. Engage Learners and Sponsoring Organizations:

• Conduct follow-up or longitudinal research that directly involves learners who have taken credit-rated courses and sponsoring organizations (e.g., employers) to understand their perspectives on the value of credit-rating.

1. Revisit the Terminology:

• Investigate whether the term “credit-rating of learning” is the most effective term. A comparative analysis of alternative terms, such as “learning accreditation” or “skills certification,” could help determine whether a clearer term exists that conveys the process’s value to all stakeholders (learners, providers, employers, and society).

1. Examine Value Co-Creation in Credit-Rating:

• Explore how value co-creation between CRBs, learning providers, and learners occurs in the credit-rating process. Identify the key factors that contribute to sustainable, successful partnerships, and develop a model to support these relationships

The anonymized dataset (second cycle of coding) for this study can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Glasgow Caledonian University ADSL/IU2B Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

CS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. CC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. FS-K: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We would like to thank GCU’s credit-rating clients for funding this study through their partnership with GCU.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Achdiat, I., Mulyani, S., Azis, Y., and Sukmadilaga, C. (2023). Roles of organizational learning culture in promoting innovation. Learn. Organ. 30, 76–92. doi: 10.1108/TLO-01-2021-0013

Ahsan, K., Akbar, S., Kam, B., and Abdulrahman, M. D. A. (2023). Implementation of micro-credentials in higher education: a systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 13505–13540. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11739-z

Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: lessons from international experiences. Nordic J. Studies Educ. Policy 6, 7–16. doi: 10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

Apprenticeships Scotland (2024) Graduate apprenticeships | apprentices. Available at: https://www.apprenticeships.scot/become-an-apprentice/graduate-apprenticeships/ (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Arabadjieva, K., and Barrio, A. (2024). Rethinking social protection in the green transition: Implementing the council recommendation on fair transition : ETUI Research Paper-Policy Brief.

Australian Government (2022) National Microcredentials Framework. Available at: https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-publications/resources/national-microcredentials-framework (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Baird, M. D., Bozick, R., and Zaber, M. A. (2021). Beyond traditional academic degrees: the labor market returns to occupational credentials in the United States. IZA J. Labor Econ. 11. doi: 10.2478/izajole-2022-0004

Balch, O. (2024) ‘Tech and generational changes increase urgency of upskilling’, Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/c8d27903-119b-4456-9694-8781fd6fe46f (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Bao, Y., Pöppel, E., and Zaytseva, Y. (2017). Single case studies as a prime example for exploratory research. Psych J. 6, 107–109. doi: 10.1002/pchj.176

Bauer, M., Sisto, E., and Zilli, R. (2024). Increasing economic opportunity and competitiveness in the EU: The role of micro-credentials : ECIPE Policy Brief.

BCG (2024) How governments can improve the global skills market, BCG global. Available at: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/how-governments-can-improve-global-skills-market (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Behringer, F., and Coles, M. (2003). The role of national qualifications systems in promoting lifelong learning. OECD education working papers, no. 3, OECD publishing. OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2003/09/the-role-of-national-qualifications-systems-in-promoting-lifelong-learning_g17a195f/224841854572.pdf (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Braxton, S. N. (2023). Competency frameworks, alternative credentials and the evolving relationship of higher education and employers in recognizing skills and achievements. Int. J. Inform. Learning Technol. 40, 373–387. doi: 10.1108/IJILT-10-2022-0206

Brennan, J. (2021) Flexible learning pathways in British higher education: A decentralized and market-based system. UNESCO. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/about-us/flexible-learning-pathways.pdf (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Brown, M., Nic Giolla Mhichíl, M., Beirne, E., and Mac Lochlainn, C. (2021). The global micro-credential landscape: charting a new credential ecology for lifelong learning. J. Learn. Dev. 8, 228–254. doi: 10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.525 (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Campo, G., Deer, J., Mørk, S. D., Fyhn, H., Larsen, A. G., Khitous, F., et al. (2024) R&I for a fair green transition: Project review and policy analysis. European Union. Available at: https://forskning.ruc.dk/files/99486724/R_I_for_a_Fair_Green_Transition.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Carton, G., McMillan, C., and Overall, J. (2018). Strategic capacities in US universities-the role of business schools as institutional builders. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 16, 186–198. doi: 10.21511/ppm.16(1).2018.18

CEDEFOP (2021) Microcredentials for labour market education and training | CEDEFOP. Available at: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/projects/microcredentials-labour-market-education-and-training (Accessed 20 December 2024).

CIPD (2023) Learning at work. Survey report June 2023. CIPD. Available at: https://www.cipd.org/globalassets/media/knowledge/knowledge-hub/reports/2023-pdfs/2023-learning-at-work-survey-report-8378.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

Díaz, M. M. M. B., Lim, J. R., Navia, I. C., and Elzey, K.. (2022) A world of transformation: Moving from degrees to skills-based alternative credentials. Inter-American Development Bank.

Dunn, S. (2022). ‘The role of credit in the Scottish credit and qualifications framework’, in widening access to higher education in the UK: developments and approaches using credit accumulation and transfer. Open University Press, 96–109.

Eraut, M., and Hirsh, W. (2010) The significance of workplace learning for individuals, groups and organisations. ESRC Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance (SKOPE). Available at: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:903bda08-1eab-4695-949a-1601e1af5273/files/me7d5d8753659652395dd6d06529c17d2 (Accessed August 8, 2024).

European Commission (2024a) EU funding instruments for upskilling and reskilling - European Commission. Available at: https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies-and-activities/skills-and-qualifications/working-together/eu-funding-instruments-upskilling-and-reskilling_en (Accessed 20 December 2024).

European Commission (2024b) European skills agenda-European Commission. Available at: https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies-and-activities/skills-and-qualifications/european-skills-agenda_en (Accessed 20 December 2024).

European Commission: Directorate-General for Employment. (2011). Transferability of skills across economic sectors – role and importance for employment at European level. Publications Office. Available at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/21d614b0-5da2-41e9-b71d-1cb470fa9789 (Accessed August 26, 2024).

European Training Foundation (2012) Qualifications frameworks from concepts to implementation. European training foundation. Available at: https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/m/529B0A5F8060186AC12581E100546EA8_Qualifications%20frameworks.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

European Training Foundation. (2016). Qualification systems: Getting organised. European training foundation. Available at: https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/m/89E0B0EEF0F8C468C12580580029F2CD_Qualification%20systems_toolkit.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

European Union. (2022) Council recommendation of 16 June 2022 on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability 2022/C 243/02. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022H0627(02) (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Gallagher, S. R. (2022). The future of university credentials: New developments at the intersection of higher education and hiring : Harvard Education Press.

Glasgow Caledonian University. (2022). Credit rating service, Glasgow Caledonian University | Scotland, UK. Available at: https://www.gcu.ac.uk/business/credit-rating-service (Accessed 24 November 2024).

Gustafsson, J. (2017). Single case studies vs. multiple case studies: A comparative study : Halmstad University.

Iatrellis, O., Samaras, N., and Kokkinos, K. (2024). Towards a capability maturity model for Micro-credential providers in European higher education. Trends Higher Educ. 3, 504–527. doi: 10.3390/higheredu3030030

ILO (2024) Micro-credentials: Powerful new learning tool, or just “pouring old wine into new bottles”? | International Labour Organization. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/micro-credentials-powerful-new-learning-tool (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Jackson, S. (2011). Lifelong learning and social justice: Communities, work and identities in a globalised world, vol. 30. Leicester: NIACE, 431–436.

Jagannathan, S. (2021). Reimagining digital learning for sustainable development: How upskilling, data analytics, and educational technologies close the skills gap. New York: Routledge.

Kyriazi, A., and Miró, J. (2023). Towards a socially fair green transition in the EU? An analysis of the just transition fund using the multiple streams framework. Comp. Eur. Polit. 21, 112–132. doi: 10.1057/s41295-022-00304-6

Lands, A., and Pasha, C. (2021). Reskill to rebuild: Coursera’s global partnership with government to support workforce recovery at scale. Powering Learn. Soc. During Age Disruption, 281–292. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-0983-1_19

Li, L. (2022). Reskilling and upskilling the future-ready workforce for industry 4.0 and beyond. Inf. Syst. Front. 26, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10796-022-10308-y

LinkedIn Learning (2024) 2024 workplace learning report | LinkedIn learning. Available at: https://learning.linkedin.com/resources/workplace-learning-report (Accessed 20 November 2024).

Mamaghani, F. (2006). Impact of information technology on the workforce of the future: an analysis. Int. J. Manag. 23:845.

Martin, M., and Furiv, U. (2022) ‘SDG-4: Flexible learning pathways in higher education–from policy to practice: An international comparative analysis ’.

McGreal, R., and Olcott, D. Jr. (2022). A strategic reset: Micro-credentials for higher education leaders. Smart Learning Environments 9:9. doi: 10.1186/s40561-022-00190-1

McKinsey (2021) The future of work after COVID-19 | McKinsey. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19 (Accessed 26 August 2024).

McKinsey (2022) Taking a skills-based approach to building the future workforce | McKinsey. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/taking-a-skills-based-approach-to-building-the-future-workforce (Accessed 20 December 2024).

McKinsey (2023) Reimagining people development to overcome talent challenges | McKinsey. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/reimagining-people-development-to-overcome-talent-challenges (Accessed 20 November 2024).

Morandini, S., Fraboni, F., de Angelis, M., Puzzo, G., Giusino, D., and Pietrantoni, L. (2023). The impact of artificial intelligence on workers’ skills: upskilling and reskilling in organisations. Informing Science 26, 039–068. doi: 10.28945/5078

Nizami, N., Tripathi, T., and Mohan, M. (2022). Transforming skill gap crisis into opportunity for upskilling in India’s IT-BPM sector. Indian J. Labour Econ. 65, 845–862. doi: 10.1007/s41027-022-00383-9

OECD (2020a) The emergence of alternative credentials, OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/the-emergence-of-alternative-credentials_b741f39e-en.html (Accessed 20 November 2024).

OECD (2024) Promoting green and digital innovation, OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/promoting-green-and-digital-innovation_feb029df-en.html (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Office of National Statistics (2017) Characteristics and benefits of training at work, UK - Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/characteristicsandbenefitsoftrainingatworkuk/2017 (Accessed 26 August 2024).

Pennacchia, J., Jones, E., and Aldridge, F. (2018) Barriers to learning for disadvantaged groups. UK Department for Education. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b7d2ea2ed915d14d88482d6/Barriers_to_learning_-_Qualitative_report.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

Pisu, M., Von Rüden, C., Hwang, H., and Nicoletti, G. (2021) Spurring growth and closing gaps through digitalisation in a post-COVID world: Policies to LIFT all boats. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/spurring-growth-and-closing-gaps-through-digitalisation-in-a-post-covid-world-policies-to-lift-all-boats_b9622a7a-en.html (Accessed 20 December 2024).

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2018) Workforce of the future - the competing forces shaping 2030. Available at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/workforce/publications/workforce-of-the-future.html (Accessed 20 November 2024).

QAA Scotland (2022). Scottish tertiary education Micro-credentials glossary. Available: QAA Scotland at: https://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/docs/ethemes/resilient-learning-communities/scottish-tertiary-education-micro-credentials-glossary.pdf?sfvrsn=c620a381_18 (Accesed December 20, 2024).

QAA Scotland (2024a) Quality enhancement framework in Scotland. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/scotland/quality-enhancement-framework (Accessed 20 December 2024).

QAA Scotland (2024b) Tertiary quality enhancement review (TQER). Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/scotland/reviewing-quality-in-scotland/scottish-quality-enhancement-arrangements/tertiary-quality-enhancement-review (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Ross, C. (2024) ‘Fresh blow to universities and businesses as axe falls on £7m fund to upskill Scottish workers’, The Scotsman,. Available at: https://www.scotsman.com/education/scotland-universities-fresh-blow-as-axe-falls-on-ps7m-fund-to-upskill-scottish-workers-4597799 (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Rybnicek, R., and Königsgruber, R. (2019). What makes industry–university collaboration succeed? A systematic review of the literature. J. Bus. Econ. 89, 221–250. doi: 10.1007/s11573-018-0916-6

Scottish Funding Council (2022) University up-skilling fund AY 2022–23, Scottish Funding Council. Available at: https://www.sfc.ac.uk/publications/pdfs__trashed/university-up-skilling-fund-ay-2022-23/ (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Scottish Funding Council (2024) Guidance for graduate apprenticeships 2024–25, Scottish Funding Council. Available at: https://www.sfc.ac.uk/publications/guidance-for-graduate-apprenticeships-2024-25/ (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Scottish Government (2008) Worth doing: Using the Scottish credit and qualifications framework in community learning and development. Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/382/7/0067465_Redacted.pdf (Accessed December 11, 2024).

Scottish Government (2022) Delivering economic prosperity. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2022/03/scotlands-national-strategy-economic-transformation/documents/delivering-economic-prosperity/delivering-economic-prosperity/govscot%3Adocument/delivering-economic-prosperity.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

Scottish Government (2023a) Fit for the future: Developing a post-school learning system to fuel economic transformation. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/fit-future-developing-post-school-learning-system-fuel-economic-transformation/ (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Scottish Government (2023b) It’s our future-independent review of qualifications and assessment: Report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/future-report-independent-review-qualifications-assessment/ (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Scottish Government (2024a) Explore the National Outcomes | National Performance Framework. Available at: https://nationalperformance.gov.scot/national-outcomes/explore-national-outcomes (Accessed 20 December 2024).

Scottish Government (2024b) Insights on key learning/future work. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/skills-recognition-scotland-srs-pilot-learning-insights/pages/6/ (Accessed 20 December 2024).

SCQF Partnership (2015) SCQF Handbook. Available at: https://scqf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/scqf_handbook_web_final_2015.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

SCQF Partnership (2017) SCQF credit rating: Criteria explained. Available at: https://scqf.org.uk/media/zayef4ff/criteria-explained-final-web-oct-2017.pdf (Accessed 26 August 2024).

SCQF Partnership (2019) ‘Referencing the Scottish Credit & Qualifications Framework (SCQF) to the European qualifications framework (EQF) ’. Available at: https://scqf.org.uk/news-and-blog/update-of-the-referencing-of-the-scqf-to-the-eqf/ (Accessed 26 August 2024).

SCQF Partnership (2022) The SCQF: Recognising skills in a changing landscape conference recordings, Scottish credit and qualifications framework. Available at: https://scqf.org.uk/news-and-blog/the-scqf-recognising-skills-in-a-changing-landscape/ (Accessed 26 August 2024).

SCQF Partnership (2024a) ‘How many qualifications are on the SCQF that are not offered from “traditional” providers?’ Email correspondence.

SCQF Partnership (2024b) SCQF register, Scottish credit and qualifications framework. Available at: https://scqf.org.uk/the-framework/scqf-register/ (Accessed 24 November 2024).