- Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Internal exclusion (IE) in the UK, wherein pupils are removed from their classroom and placed in a separate area within the school, has been implemented to mixed reception with the intention of reducing classroom disruptions. For this study, an online survey was completed by 34 parents of children who have experienced IE, focusing on parent perspectives of their children’s experiences and mental health (MH), with 67% of parents reporting that their child felt distressed or unhappy while in IE. Eleven parents also participated in a semi-structured interview. Thematic analysis of interviews generated three themes: (1) IE as a tool to manage disruption, (2) counterproductive implementation, and (3) breakdown of trust with the school. Results highlight that parents felt the implementation of IE was given inappropriately, negatively impacted their child’s MH, or was ineffective in improving behaviour. Parents of pupils with learning difficulties also found IE to be difficult, and suggested alterations to existing IE implementation to support communication between schools and families and to prioritise the voices of pupils and parents in the school environment at the whole-school level.

1 Introduction

Internal exclusion (IE) refers to a process by which pupils are removed from their school’s normal area of education and placed in a separate area within the school (DCSF, 2009). It is considered an alternative to fixed-term exclusion, when a pupil is temporarily removed from a school altogether (Barker et al., 2010). IE areas, also known as “internal inclusion units” (Mills and Thomson, 2018), “remove rooms” (Sealy et al., 2021), or more broadly, “isolation room punishment” are designed to isolate individuals from their peers or to interrupt disruptive behaviour (Sealy et al., 2021). Disruptions by pupils can cause difficulties with behavioural management for school staff, increasing stress in the classroom and decreasing learning time for pupils (Burton and Goodman, 2011; Ofsted, 2014; Rhodes and Long, 2019). As a result, teachers and support staff may find themselves seeking ways to prioritise productive and nurturing environments for pupils as a means of alleviating pressure to meet learning targets and to handle disruptive or challenging behaviour (Burton and Goodman, 2011). According to guidance from the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF, now called the Department for Education), the purpose of IE is to alter the behaviour of young people (YP) by having them spend time working constructively on their assignments or evaluating their behaviour (DCSF, 2009). In 2018, the Department for Education (DfE) reported that over half of secondary schools used internal inclusion units for pupils vulnerable to exclusion (Mills and Thomson, 2018), with a wide variety of duration and frequency observed in general exclusion practices (Power and Taylor, 2020). The DfE has also outlined the potential variety of implementation between schools, with some offering it as a place of reflection, and others being more punitive (Skipp and Hopwood, 2017). However, the DfE’s official guidance on school behavioural policy in the UK prioritises suspension and permanent exclusion, with less focus on examining IE policies, highlighting the potential allowance of varied policy implementation across the UK due to lack of current detailed data on individual forms of IE (Department for Education, 2024).

Exclusion practices have been found to be more common among children with specific vulnerabilities, such as special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) or low socioeconomic status (Tejerina-Arreal et al., 2020). It is therefore important to understand potential connections between IE, mental health (MH), and academic outcomes for individuals with specific learning difficulties. Lack of proper implementation and moderation of IE may also potentially have negative psychological impacts on the MH and educational outcomes of YP, as seen in wider exclusion practices (Martin-Denham, 2020), suggesting a need to look further into how isolation-based punishment impacts the wellbeing of YP. Overall absence from school has been negatively linked to attainment in UK schools, with lower attainment associated with additional days missed from school (Department for Education, 2016), although more data is needed on IE specific absences and long-term pupil development. Some studies, however, reported that IE has allowed pupils to improve attainment and to resolve disciplinary problems without disrupting academic progress (Gilmore, 2012, 2013). Other research suggests that IE may have varied effectiveness due to variations in practice (McCluskey et al., 2015; Timpson, 2019).

In a 2022 survey, only 7% of parents and 21% of YP in England felt that “schools are responsive to young people’s mental health needs when dealing with behavioural issues” (CYPMHC, 2022). A recent report raised the concern of removal rooms being used as a deterrent or in response to minor offences (Rainer et al., 2023). Some studies also found isolation rooms to be distressing or detrimental to the emotional wellbeing of pupils (Sealy et al., 2021) with potentially discriminatory, disproportionate punishment given to some pupils based on demographic factors (Gillies and Robinson, 2012). Other pupils likened IE spaces to that of a “prison” and stated that these rooms fail to provide adequate long-term support for healthy internal change, making them feel powerless (Barker et al., 2010). This could potentially parallel fixed-term exclusion from school, wherein some parents have reported limited support or communication from their school for their children’s needs (Parker et al., 2016).

Arguments have been made to move away from processes emphasising punitive control in education (Barker et al., 2010; Condliffe, 2023; Cushing, 2021; Noguera, 2003). Supported alternatives to exclusion practices include implementing a “whole-school approach” which involves shaping school culture to intervene on the behalf of positive behaviours and to prevent the development of negative or disruptive behaviours (Graham et al., 2019). Parent involvement in their child’s education has likewise been documented to have positive effects on their child’s achievements (Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003), so drawing connections between the wider network of pupils, their schools, and their parents could shed light on further potential influences of IE. As practical application of IE is varied and receives mixed reception from pupils who experienced IE, and with little qualitative research that explores parent perspectives and the nature of second-hand reactions to IE implementation, this study focused on the experiences of parents whose children had been internally excluded as well as perspectives regarding how parents felt IE had impacted their child’s MH and overall education experience.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics, recruitment, and data collection

This study was reviewed and approved by the Cambridge University Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE.2022.116). This study occurred between February and July 2023 and recruited voluntary participants: parents who live in the UK with children who have experienced IE. Parents were recruited through social media, UK community groups, and over email and charity websites. Parents were invited to participate in a survey as well as an optional additional interview.

Data collection took place online, with surveys via Qualtrics and interviews through Zoom. The survey took 30 min or less to complete and asked matrix table questions with Likert type responses based on their experiences with IE in schools, MH, and their impressions. Participants were interviewed by a member of the research team (KT). The interview was semi-structured and guided by a topic guide (see Supplementary File 1). The researcher allowed the participant to naturally and organically discuss topics that they wished to share. The interviewer strived to develop a positive rapport with the participant to provide a comfortable environment for the participant to share their experiences.

2.2 Data analysis

Survey open-ended questions were analysed using conventional content analysis, wherein responses were read and analysed (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Interviews were transcribed by the primary interviewer (KT) and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA), prioritising interpretative development of themes following a process of coding the data, as influenced by the subjective understanding of the researchers (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019, 2021). The data was inductively coded, highlighting and identifying patterns and groups among the data set. Mind maps and tables were created to visually collect ideas and to organise participants with shared characteristics. KT and A-MB met weekly to discuss the analysis and thematic development and this process generated three major themes. This research strived to find shared meanings among experiences of IE within the data set through an interpretative process and continuous self-reflexivity by the researchers: A-MB and JA as chartered psychologists working with MH and education, and KT from the perspective and reflections of a student (Braun and Clarke, 2019).

3 Results

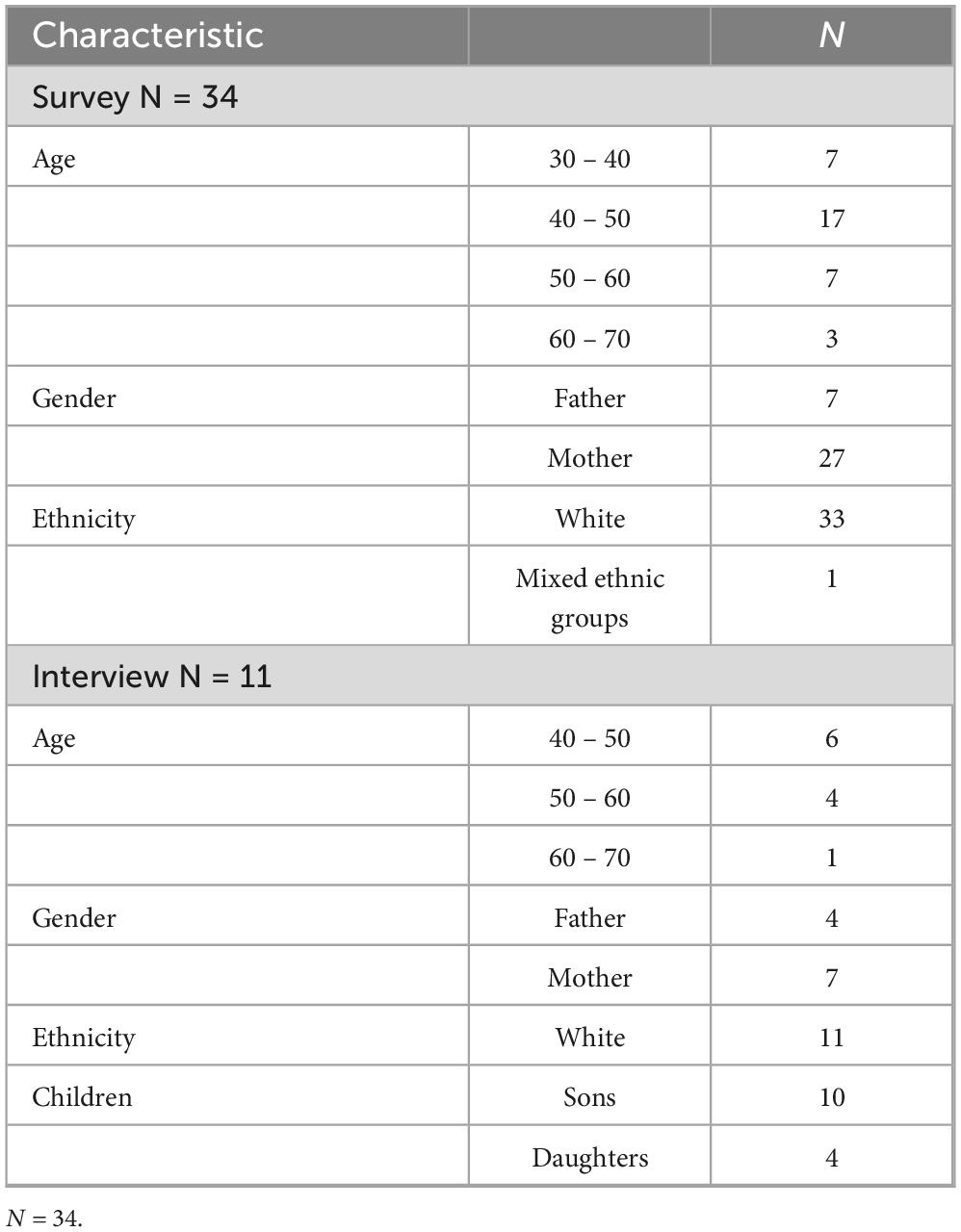

The results section first discusses general survey Likert responses and open-ended question responses, followed by qualitative analysis of interview findings. A total of 34 parents participated in the survey and 11 in the interview (see Table 1). Of these, 21 parents reported that their child has some form of specific learning difficulties or SEND, with many experiencing IE during secondary school. Parents also reported a variety of implementation frequency and duration, with some dividing pupils into rooms or booths or using dividers. Of the 11 interviewed parents, the experiences of 10 sons and 4 daughters were discussed.

3.1 Survey findings

When asked about their general experience while their child was in IE, most parents reported that the experience was negative to some degree (76%, n = 26), with half of parents (50%, n = 17) reporting that their experience was very negative. When asked to respond with how their child’s MH was when their child was in IE, 26 (76%) found their MH to be negative to some degree, with 14 (41%) finding it very negative. The majority of parents likewise found their own MH to be negative to some degree (76%, n = 26) with most in the “negative” category (35%, n = 12).

Survey responses to open-ended questions were mixed, with some parents describing their experiences with IE as ineffective and upsetting, and others describing them more positively as a form of behavioural correction. Parents reported that IE implementation in their school was referred to by several names, including but not limited to: isolation, isolation booths, detention, reset, inclusion, seclusion rooms, IE, a refocus room, or a withdrawal room. Parents also reported a variety of implementation frequency, with some parents stating that their child had only undergone IE once, and others reporting that their child experienced IE multiple times, such as for whole school days or multiple times a week. Parent responses often utilised strong language to describe their impressions of IE.

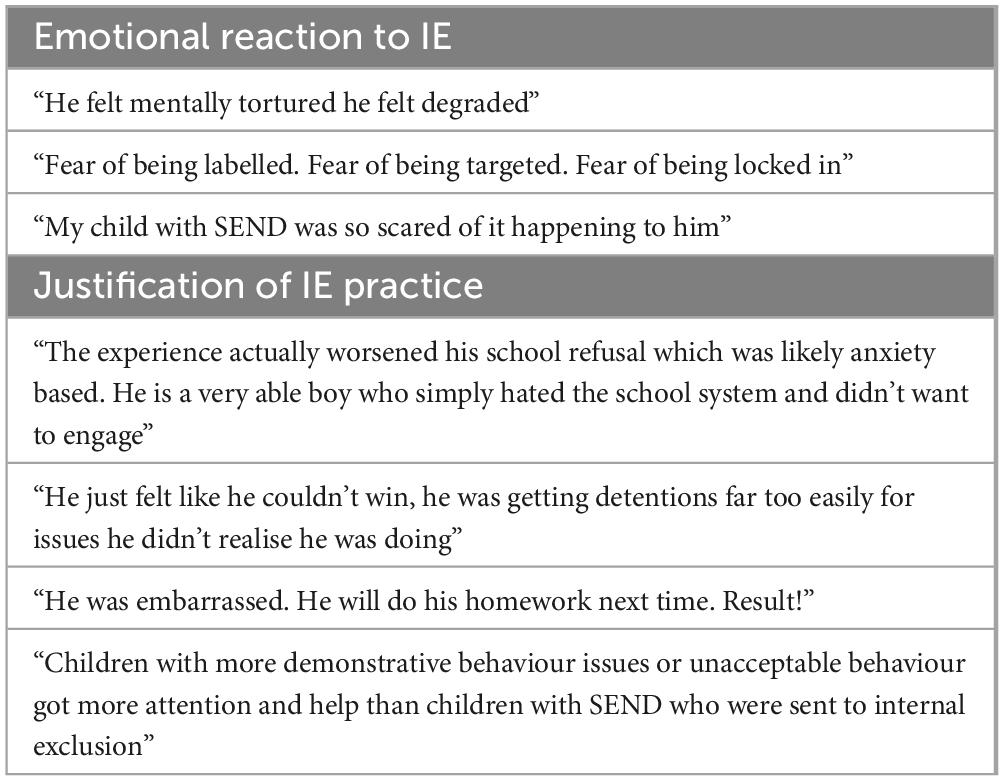

3.1.1 Emotional reaction to IE

Many of the parent responses in the survey expressed unhappiness with the current state of IE at their schools, as written in their emotional descriptions. The majority of parents agreed that their child felt distressed or unhappy while in IE at school (67%, n = 23) and wished for their schools to implement more effective education policies. The majority of parents (61%, n = 21) negatively assessed the MH provisions provided in their schools. Some parents wanted a change to their school’s IE practice as they found it detrimental to their children’s MH and wellbeing.

Strong emotional responses were likewise expressed by pointed word choice in the open-ended responses, with some describing IE as “peculiarly cruel,” an “evil practice,” or “inhumane, torture.” One parent described their child “feeling targeted,” whereas another parent described the teaching assistant in charge of IE as “like a prison guard.” Some parents reported that their child felt increased fear of attending school and anxiety about the school system as a result of their experiences or in anticipation of receiving IE. Table 2 gives additional emotional responses from the open-ended questions.

3.1.2 Justification of IE practice

Parents generally did not think that IE was effective, justified, or fair. Nearly three quarters of participants (73%, n = 25) disagreed that the punishment their child received at school was fair and justified. Additionally, when asked if they agreed that pupils with learning difficulties are supported at their child’s school, responses were fairly mixed, with 15 participants (44%) disagreeing to some degree and 15 (44%) agreeing to some degree. Most participants (70%, n = 24) strongly disagreed with the notion that IE improved their child’s ability to learn.

Some parents were not averse to the use of IE for the purpose of managing disruption in the main classroom. However, they did feel that IE was unfairly implemented for minor infringements and disengaged their children from their peers and the learning environment. A connection was drawn by some parents between the use of IE as a punishment and their child’s SEND characteristics. A few parents expressed an increased sense of compassion from their school after their child’s special educational needs were identified, whereas others felt that IE was unjustified and unfairly targeted children with SEND, leaving them without adequate support from their schools.

Some parents doubted the overall effectiveness of IE in improving their children’s behaviour and education outcomes. While they understood the motivation to manage disruptive behaviour, they often declared that the practice of IE offered no additional incentive for their child to improve and thus decreased valuable education time and failed to change their child’s behaviour. A few participants gave favourable responses to the contrary, finding that IE allowed their children to focus and reflect on their behaviour which led to improved behaviour in class. Table 2 provides a few additional responses to the open-ended questions.

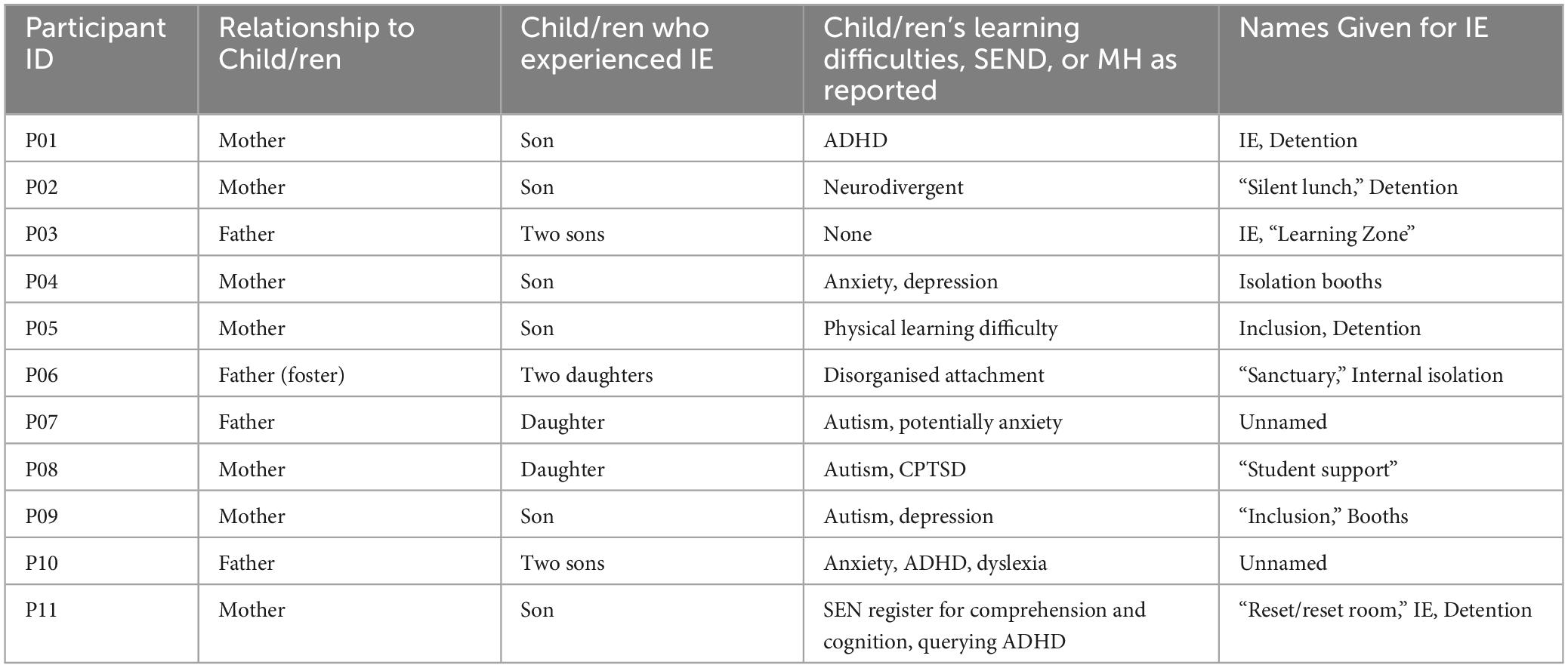

3.2 Qualitative interview findings

Various terms and names were used to describe the form of IE utilised by the schools of the participants as well as the places within the schools that IE took place (see Table 3). Some of the implementations were simply referred to as “internal exclusion” or forms of after school detention, whereas others reported the use of names such as “inclusion,” “reset,” “silent lunch,” “student support,” or “learning zone.” Parents relayed that most IE was experienced during secondary school or at the age of 11 or later. Parents reported varying levels of frequency of their children experiencing IE, from one time incidents to repeated numbers of incidents over months of time.

Various descriptions of IE rooms were given, most describing a specific classroom within the school that was dedicated for placing their child in IE (P03, P07, P08, P09, P11), or that the classroom was used in various ways including for IE. Most parents described a level of supervision by school staff (teachers or other staff members) of the children in these rooms, where the pupils were not allowed to leave without permission. Some parents noted a lack of exposure to peers or that pupils were not allowed to leave the room during IE. Some likened the room used for IE to that of a prison (P02, P06, P09) or that the building where their child was being held was notably “austere” (P06). Some classrooms divided pupils into booths (P04, P09) or utilised dividers to separate pupils from their peers.

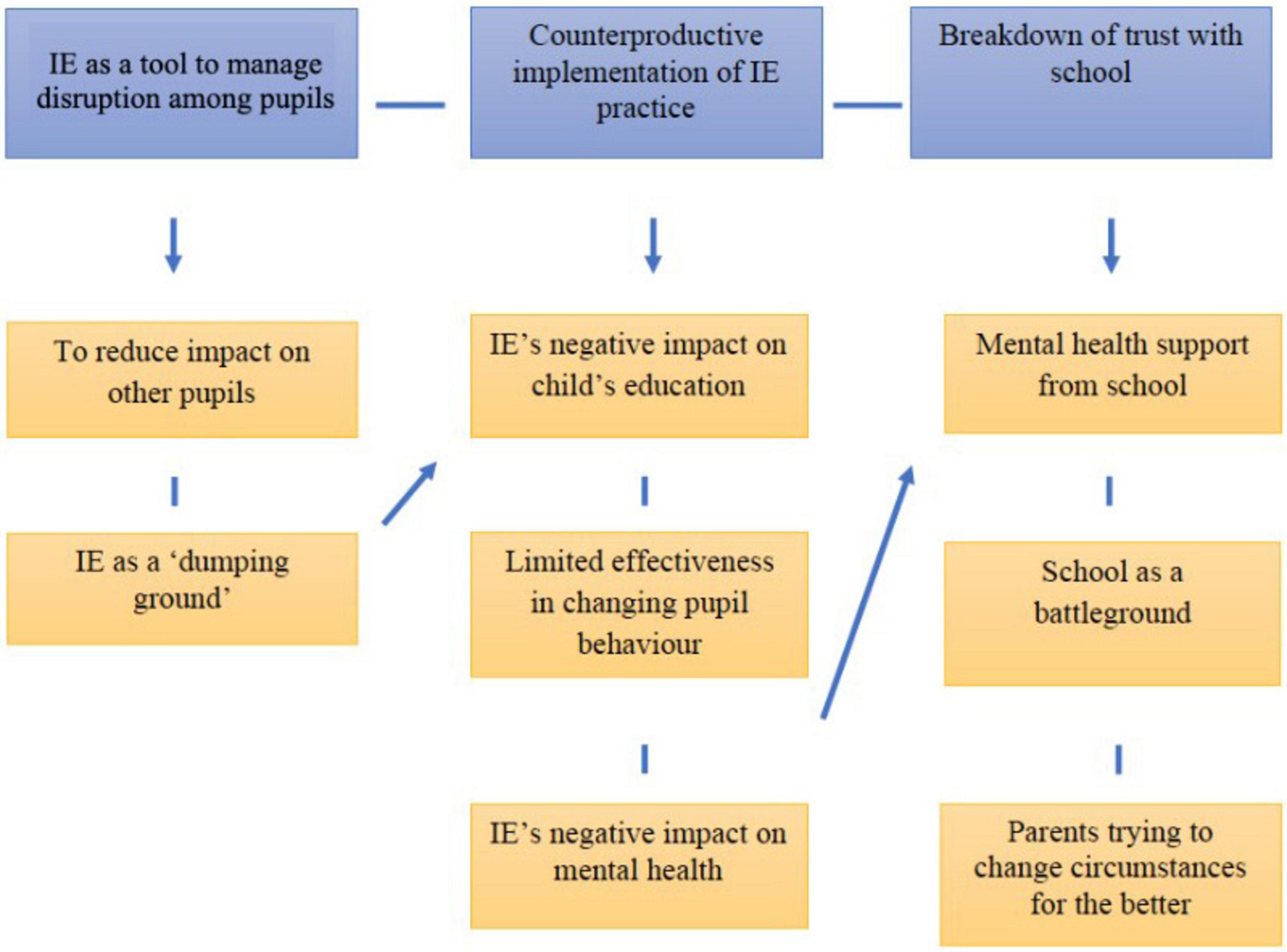

Thematic analysis of interview data led to the generation of three main themes with multiple subthemes (see Figure 1).

3.2.1 Theme 1: IE as a tool to manage disruption among pupils

To reduce impact on other pupils

Some parents reported that their child had been given IE for “legitimate” or genuine reasons, such as disturbing another child or school property or breaking established school rules, like speaking out of turn or disrupting class. These participants remarked that the practice was being used as a way to reduce the impact on other students or disruption in class, and expressed that some form of behavioural correction might be necessary for their children. However, parents relayed that IE offered little direct benefit to their own child. They did not agree with the specific implementation, severity, or duration of IE that their child had experienced. Even though parents felt their child’s behaviour warranted correction, they said the incident had involved minor incidents or infractions and the response had been disproportionate.

It [IE] was kind of an irritation, you know, they [children] didn’t feel it was appropriate for what they’d done in both instances.

(P10, Father of sons)

Some parents felt that their children were being isolated arbitrarily or unfairly as punishment and questioned why their child would need to be given IE at all. One even stated that their child was being made an example for other pupils.

…he’d broken a window – it was an accident…but because it had caused so much disruption in the school, the head teacher felt that he needed to make an example of him and that’s why the punishment was quite severe.

(P01, Mother of son)

IE as a “dumping ground”

Some parents relayed that the reasons they felt that their children had been sent to IE were not for direct behavioural problems, but rather for specific traits or characteristics exhibited by their child. While most parents found little benefit to their child being in IE, some made a point to say that IE may be beneficial to children who prefer to be removed from noise or peer distractions, but that some children might find IE harder to deal with than others because it fails to provide for their particular vulnerabilities or because they may have different preferences. Although IE may be seen as beneficial to some children, parents remarked that some children might find IE harder to deal with than others.

I think for children where their mental health is already quite low, it’s just really bad. You know for children who are overwhelmed by noise and crowds and all those things, probably quite a nice experience. But for children who want to actually get on and you know achieve, to sit and be given nothing to do would drive you mad.

(P04, Mother of son)

Parents felt that their schools were not adequately providing for or making reasonable adjustments for the children and their unique vulnerabilities. Other parents seemed to suggest that their children were given IE for inappropriate reasons related to specific traits relating to their child’s neurodivergence, SEND, or MH issues. They frequently felt that their school was unable to adequately handle specific behaviours and dealt with them as they would a disruptive child.

[the school] disciplined [my child] in the same way that you would if a child didn’t have additional needs or special needs. So, it would mean that if she questioned something – because she’s very logical so she would ask questions – or if she couldn’t cope, then she was often told to go to the place where – out of the classroom.

(P08, Mother of a daughter)

Parents generally felt that these practices were being unfairly implemented as punishment for their child’s personality or for not fitting into “the mould” of a more typical pupil. Because of this disconnect, parents felt that their schools defaulted to IE and were unwilling to work specifically with their children.

She’d never given anyone any trouble, but she was still treated as the same as say, quote unquote, “bad” or “naughty” pupils because they simply didn’t have a plan, and the school didn’t have the capacity, the capability to actually do anything for her. She was just dumped in there and left to rot, really.

(P07, Father of daughter)

One described the IE space as a “dumping ground” for children, further divorcing them from the classroom and exacerbating pre-existing issues with attendance. Instead of providing for their child’s specific educational needs or allowing the child to catch up with missed work, the school segregated them from their learning environment, breeding resentment in pupils and parents.

…this is why I used the term “dumping ground,” it became the sort of the space, well what do we do with this young lady? She can’t be in the classroom. We’re not gonna provide her with any work.

(P07, Father of daughter)

3.2.2 Theme 2: Counterproductive implementation of IE practice

IE’s negative impact on child’s education

The implementation of IE was sometimes counterproductive toward the goals of fostering a nurturing environment for pupils. One parent described it as a “blunt instrument,” suggesting a one-size-fits-all approach without regard to the nuances of individual family circumstances. A common issue parents reported was that their child was not allowed to do “proper class work” while in IE, and instead had to sit and occupy themselves with doing other activities or nothing for long periods of time, leading to frustration. A main concern was that their children were missing out on vital school time or peer interaction because of time spent in IE, which often lasted whole school days, multiple times a week, or extended after school.

I kept saying to them, but his teachers aren’t coming to either bring him work, what is the point in him being there if his teachers aren’t coming to bring him work? Or check in on him? Or see where he’s up to with things? There was just, it was hopeless. Made me very cross.

(P04, Mother of son)

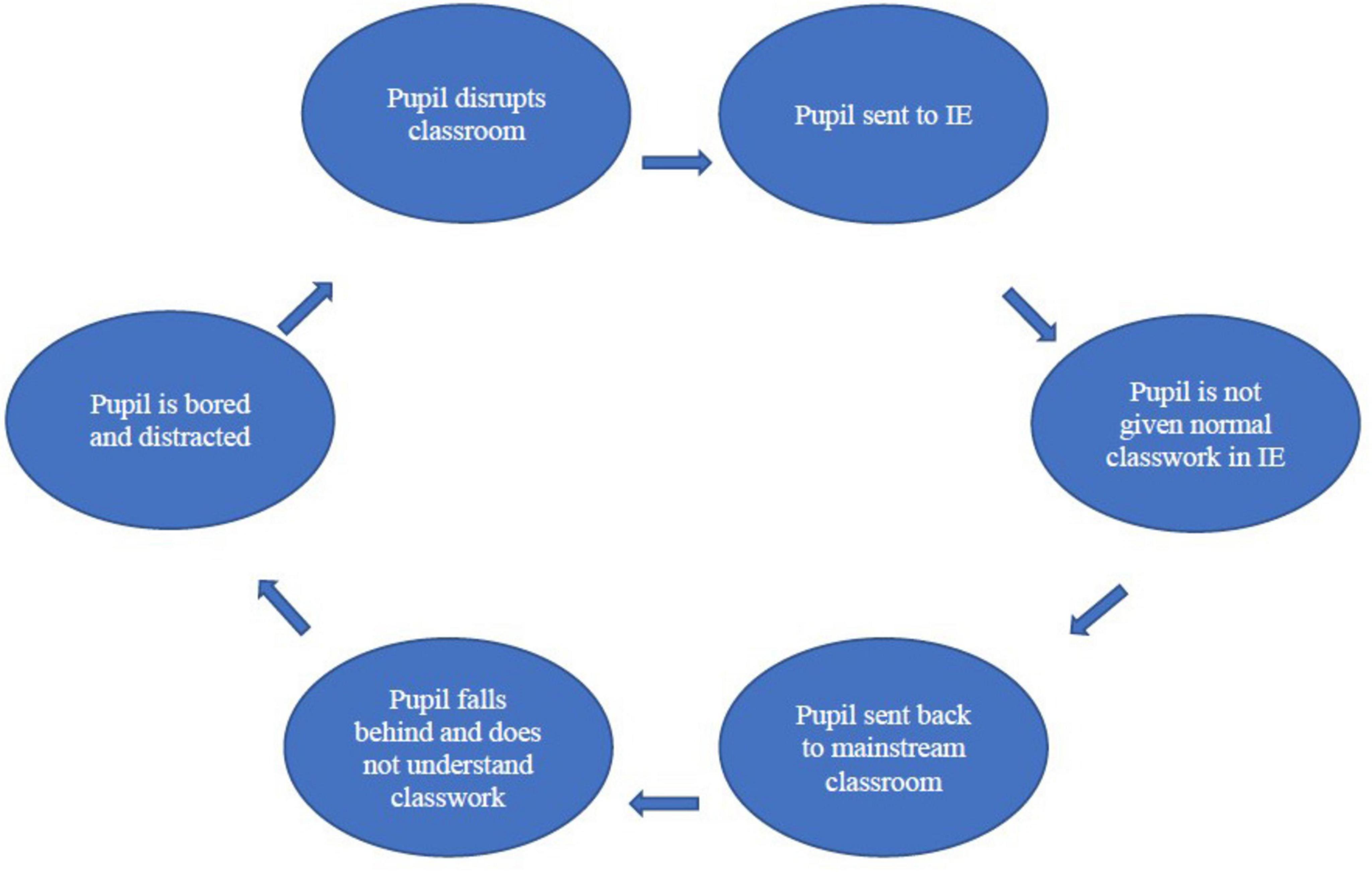

Children removed from the classes could fall further behind academically and cause further disruption because they did not understand lessons they missed, which some parents perceived as an escalating relationship that negatively impacted their academic performance and class involvement (see Figure 2). Parents were frequently visibly frustrated during the interviews when describing that their children had been upset because they would miss out on normal classroom time and interaction with their peers.

Figure 2. A visual representation of the cyclical nature between IE implementation and returning to the mainstream classroom as described by parent participants.

Now he’s lost so much time in certain lessons that his grades are starting to drop and then he goes back into certain lessons and not being able to understand what he’s got to do and quite often then might be sent to Reset again because he can’t do the work. So, he’s now in this vicious cycle and it’s mentally killing these children basically.

(P11, Mother of son)

Limited effectiveness in changing pupil behaviour

A common view was that IE practices had limited effectiveness in improving behaviour in the long-term because of their child’s inability to reflect on the reason for spending their time there and the consequences for their actions, or because of their child had disengaged from the school’s attempts at discipline.

He’s a child that does not learn from his mistakes because he doesn’t remember the consequences of his actions, anything that he’s done before and he’s very impulsive. So, for a child like him that sort of punishment…is just completely pointless.

(P01, Mother of son)

One parent explained that their child actually utilised “a positive pathway to a negative outcome” by intentionally disrupting class so they would have time on their own in IE. In this case, the parent suspected that their child was using IE as a coping strategy by being away from her peers.

…mostly she would be spending her time just trying to undermine whatever the process was that was put in place that was trying to help her regulate her behaviour…it was a game of cat and mouse…

(P06, Father of foster daughter)

IE’s negative impact on MH

Parents described their children’s emotional experiences during and after IE, which ranged from simple dislike to feelings of distress or panic. A few parents mentioned that they had been given support for their children’s MH at school and did not foresee many long-term MH impacts on their children as a result of their IE experience. Others described the experience for their child as being akin to a prison, or that the experience was demoralising, upsetting, or irritating.

[IE] was very close to hell for him.

(P02, Mother of son)

Some commented on how their child struggled to cope with the isolated setting of IE, or disliked how their child was deprived of fresh air, interaction with peers, or a proper lunch. In some cases, parents said that IE made it difficult for their children to return to school, with previous poor experiences in IE negatively impacting their child’s MH over time.

He was there [in IE] because he refused to go, he found school just really uninspiring. You know, hugely anxious, but he became depressed. And I did take him to the doctor, and they said he was depressed.

(P04, Mother of son)

The repetition of IE was described as ineffectual and contributed additional stressors to the child’s education.

…if it worked, it should have worked by now. It’s not working and it’s for minor infractions as I said. And all it’s doing is causing problems to their mental health. He’s up at night sometimes crying at half eleven feeling absolutely worthless, life’s not worth living, what is the point of going to school.

(P11, Mother of son)

During these experiences, a few parents felt the need to remove their children from school entirely. One parent refused for a time to allow their child to return to IE, with the intent to protect their child’s MH.

…we kept him out of it [IE] for 2 weeks…We said he’s not doing any. And in fact, his attitude at home changed for the better. We actually started seeing him smile again. Just 2 weeks taking him out of the Reset room made a massive difference to his mental health.

(P11, Mother of son)

The use of IE also put a strain on family life, making it difficult for parents to plan their day or know when their child would come home or receive additional punishments. Some expressed dissatisfaction or anger with the ways in which IE impacted their children’s MH and their own lives.

I’m up a lot in the night, I can’t stop thinking about – I’m worried about his next day because I know which teachers he’ll get “resets” from. And I know when he gets in there what a pickle, he’s gonna get in to cause he’s worried he’s gonna get suspended from that room. It’s affecting my husband and we’ve always been really positive people, really supporting people, and even my husband has said at points he’s felt like just ending it all because this is how bad it’s getting.

(P11, Mother of son)

3.2.3 Theme 3: Breakdown of trust with school

MH support from school

A variety of MH support given by their schools was described by parents with mixed views. Some parents were aware that some forms of MH support were provided by the school, such as counselling. Others said that their school failed to provide adequate support for the MH needs of their child and failed to make reasonable adjustments for their child’s education in response to concerns about their child’s needs. Parents wished that their schools were capable of providing support for preventing behavioural issues that would lead to IE implementation in the first place, highlighting a potential inconsistency between schools. They identified that schools ultimately failed to communicate sufficiently and transparently with parents.

I know schools aren’t perfect and they don’t have the ideal provision, but they did not address his special needs…and they didn’t address his particular background either, with mental health issues, and perhaps if they’d paid more attention to that, things like that wouldn’t have happened.

(P09, Mother of son)

Some parents described that the faculty at their schools were actually accommodating or provided special individualised one-on-one teaching as a result of their difficulties. In these cases, the school was able to provide potential workarounds for grievances brought forth by pupil behaviour or parent concerns. Other parents possessed an understanding of the difficulties involved in providing support, but still described inadequate care, citing a lack of resources, skills, or training for teachers, or even unprofessional behaviour by faculty.

I’m not sure how qualified she [teaching assistant] was, but she did it [IE] most of the time, this particular person. And he described her to me as a sort of prison warder… he said she was vindictive.

(P09, Mother of son)

School as a “battleground”

Participants would also cite repeated failed attempts to contact the school about changing their IE policies, such as reducing duration or frequency. In these incidents, parents discussed that contact with the teachers would prioritise punishing their children over nurturing an educational environment.

I wish schools would listen to parents and children. I don’t feel like they do but I also recognise that they don’t necessarily have the resources to do that but when I’m kind of sat there going, oh you’re making things really bad for me and you and him, like is there not another way we can do this?

(P05, Mother of son)

This led to a breakdown of trust between parents and pupils with their school, where parents were frustrated about the lack of control over their child’s experiences and the general lack of concern for their children.

So, the more that they [school] tried to – (sigh) crush him? For want of a better word, the more that he would fight back and be like “no actually, you’re wrong, I’m right.” And it had massive negative impacts I think and even though it’s only a few occasions it kind of just adds to the narrative of school being a horrible place, a fighting place, a battling place where you’re constantly trying to be heard, where you want people to understand you.

(P05, Mother of son)

Parents trying to change circumstances for the better

In response to the problems parents found with their children’s experiences, parents commented upon the ways they attempted to improve their circumstances through direct communication with their school. They mentioned personally writing provisions for their children or moving schools entirely, in hopes that their child might have a place to start over.

They knew he had special needs; they knew he had a history of mental health issues, and it made no difference. I don’t think it was an unusually punitive school or anything, they were following procedure, they were doing what they normally do.

(P09, Mother of son)

Some parents drew upon their own professional experience of working within psychology or education, sympathising with the teacher position but feeling that they were held back from making meaningful changes as parents. Support groups were formed among parents to compare and reflect on experiences, especially for those of children with specific learning difficulties.

Because I work in schools and I know how schools work and I know that the system can be so much better than that, but they didn’t want to hear it, and they certainly didn’t want to hear it from me.

(P04, Mother of son)

4 Discussion

This study highlighted the experiences and views of parents of children who have experienced IE in UK schools. Interviewed parents frequently had emotional reactions to their child experiencing IE, such as distress or frustration with the school’s justification or implementation of IE. They often understood that schools could use IE to manage disruption but found these methods to be counterproductive to the purpose of improving the MH and general learning environment for pupils, which in many cases led to a breakdown of trust between parents and their school. These findings are important as they help to shed light on how some parents in the UK view IE as a practice impacting their child’s overall academic experience, both as a potential influence on how their child’s educational environment is maintained, but also as a factor in their child ’s ongoing MH.

A wide variety of IE practices exist throughout the UK which vary from school to school, an observation which was evident in the responses to the current study and previously (Skipp and Hopwood, 2017). Prior literature suggests that disciplinary inclusion rooms are an effective model to enhance learning for pupils (Gilmore, 2012, 2013). However, the findings of the current study suggest that the methods of implementation sometimes do not meet the goals of improving the educational environment for pupils. Parents in the current study often expressed how their children felt cut off from the mainstream classroom as a result of IE. As greater levels of absence from school has been found to be associated with lower attainment in UK schools (Department for Education, 2016), it might be useful to further consider how IE specific absences from the primary classroom might contribute to levels of attainment and other academic and social outcomes among pupils, such as sense of belonging and long-term academic development. Parents also believed that IE practices held limited effectiveness in improving pupil behaviour, and as such the pupils would further disengage from the classroom or would not reflect on their behaviour or properly learn consequences. Similar to how pupils who are engaged with zero tolerance policies or fixed-term exclusion are more correlated with poorer academic performance (Gill et al., 2017; Skiba, 2014; Tejerina-Arreal et al., 2020), parents in this study were also concerned that IE might contribute to poorer academic performance and behaviour. This came across in parent accounts of children not being allowed to do normal class work in IE or falling behind in regular classes and further disrupting the classroom after IE.

Parents’ accounts suggested that IE is utilised to manage disruption and reduce the educational impact on other pupils, which broadly falls into DfE guidelines and reflects other descriptions of IE (Department for Education, 2012; Sealy et al., 2021). Parents in the current study emphasised that IE as a response to disruption was at times disproportionate to their child’s offence and provided little direct benefit to their children, similar to comments in a previous report (Rainer et al., 2023). These findings stand in contrast to other accounts of inclusion room usage as a means to help reduce fixed-term exclusions and promote inclusive practice (Gilmore, 2012). Similar qualitative analysis of isolation booths has found that pupils sometimes consider the practice to be disproportionate or unjust, due to limited perceived benefit, a dislike of a punitive approach, and a perceived lack of autonomy (Condliffe, 2023). This seems to suggest that in certain cases, parents consider IE to not be entirely beneficial for managing disruption in classrooms.

Parents viewed the implementation of IE as either inappropriate or given for arbitrary reasons, indicating a lack of regulation or sufficient justification, which has similarly been highlighted in other studies regarding inclusion room practices (Gillies and Robinson, 2012). IE in the current study was seen as a “dumping ground” for children with SEND or poor MH, with some children described as being unfairly placed in IE for their characteristics rather than errant behaviours, resulting in their specific needs not being met. This highlights a similarity between forms of IE and greater alternative provisions and exclusion processes, such as a previous study in which pupil referral units were also considered by a local authority officer as a “dumping ground,” in how it tackled the perceived variability of meeting the specific needs of children (McCluskey et al., 2015). The diverse nature of IE practices observed in this study as well as the emphasis on personal perceptions of parents additionally supports further consideration of IE’s impacts on both pupils and the families of pupils, due to the existing difficulty of classifying schools as more or less inclusive due to lack of standardised duration and frequency data regarding wider exclusion practices (Power and Taylor, 2020). Additionally, the limited guidance for IE in comparison to more traditional exclusion practices could suggest the need for further evaluation of recommendations for IE practice as a form of widespread education policy, which could be provided through clarification of policy prioritisation by the DfE, comparisons of IE and consistency of MH care across different schools in the UK, or further evaluation and data collection on standardisation of frequency, duration, or methods of practice (Department for Education, 2024).

Many participants of the current study reported that their children had some form of SEND or MH difficulty, which bears resemblance to findings suggesting that children with learning disabilities are associated with traditional exclusion (Ford et al., 2017; Toth et al., 2023). Parents in this study also pointed out that their children might be punished in the same manner as children without SEND, and that schools were unwilling to find productive alternatives for children that did not fit the mould of an average pupil. When considering the particular vulnerability of children with SEND (Tejerina-Arreal et al., 2020), this treatment could become an issue. In the current study, parents said they and their children sometimes struggled day to day to cope with school, with IE seeming to add unnecessary stressors or fears to the school environment. A previous qualitative study into IE found similar potentially damaging effects to the MH of pupils, suggesting that prolonged isolation deprived pupils of proper stimuli (Sealy et al., 2021). Other studies echo sentiments and language found in the current study, likening IE and isolation booth practices to prison geographies, leaving pupils feeling powerless (Barker et al., 2010; Condliffe, 2023). Schools and researchers may wish to re-examine how IE engages with specific groups of pupils, how it might fail to inspire certain individuals to learn, or how it may worsen their MH or the MH of their parents in the long-term. This suggests IE practices may not be used in the way they were originally intended, as seen in a perceived lack of regulation among some schools in the study and in previous literature.

These findings also suggest the need to more closely examine the intersections between special needs and the reasons behind IE implementation. While some parents in the current study were unhappy with the degree or severity with which IE was enacted, some addressed that IE rooms might be more beneficial for children with specific needs, such as those who wish to be removed from their peers. Existing literature suggests that these accounts fit into the desired outcomes for employing IE as a positive model of behavioural management in schools (DCSF, 2009; Sealy et al., 2021). In cases such as this, pupils with SEND may actually prefer to be in IE or in a more isolated environment, depending on school specific factors of implementation.

Additionally, participants frequently spoke about how that they felt their school did not listen to the concerns or ideas of parents or involved pupils, thus preventing changes or improvements from being made to the academic experience or environment of their children. As a result of this lack of communication from their schools and failures to provide adequate provisions for their children in the form of MH support or alterations to existing IE practice, parents felt ignored and incapable of improving their child’s overall educational experience, as well as uninfluential in their school’s community. This led to a breakdown of trust with schools, similar to how pupil experiences have been associated with the degree of communication between pupils, parents, and the school in regard to traditional exclusion practices (Parker et al., 2016). It has been suggested previously that greater counselling and MH support in schools after pupils have experienced an exclusion may be a factor in improving MH and reducing further exclusions (Toth et al., 2023). Findings of the current study also cited a lack of proper response from schools, as parents often described attempts at contacting authority figures within the school to discuss compromises or alterations to established practice, only to be met with limited action by the school. Communication between school staff and parents is considered an important aspect of defining school climate and influencing a positive academic environment (Wang and Degol, 2016), especially in regard to promoting good MH support between teaching staff and pupils (Jessiman et al., 2022). The findings of this study highlight the potential for school staff to use IE practices to prioritise acts of punishment over educational encouragement, which may contribute to correlations between poorer MH and academic performance, as seen in more traditional exclusion practices (Gill et al., 2017; Tejerina-Arreal et al., 2020). This is supported by previous literature which suggests for appropriate and prompt intervention in support of children with MH problems (Ford et al., 2017). Parents also frequently mentioned how they felt that a lack of resources for schools and teachers may contribute to diminished overall care for their children, which falls in line with how some schools find it difficult to meet curriculum targets, raise school standards, accommodate SEND pupils, and provide inclusive spaces for pupils (Burton and Goodman, 2011).

Pupils in a previous study similarly acknowledged the perceived injustice of being placed in isolation rooms (Sealy et al., 2021), supporting the idea that IE can introduce difficulties for some parents and their children. It has also been argued that parent and school collaboration is important in the academic achievements and MH of pupils (Povey et al., 2016), and that parents might take both “proactive” and “reactive” roles in their child’s school life (Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003). The importance of a positive school climate in reducing unfavourable behaviours, increasing pupil achievement, and impacting MH is also recognised in literature (Jessiman et al., 2022; Wang and Degol, 2016), so increased division between parents and schools suggests that IE may be associated with altering the school climate. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines recommend adoption of a whole-school approach to the education environment, which consists of considering the school community as an interconnected unit which supports the wellbeing of staff and YP, including those with learning difficulties in education (NICE, 2022). Parent frustration with IE in this study may be indicative of a general deviation from whole-school approaches and an absence of widespread trauma-informed practices that prioritise pupil wellbeing.

Parents and pupils have previously expressed that they perceive overly strict teachers as having a detrimental effect on MH, and that a prioritisation of academic performance meant that teachers would not be able to adequately handle pupil stress (Jessiman et al., 2022). As a result, this study likewise supports the suggestion to further reevaluate punitive disciplinary systems and to prioritise more restorative practices, foster communication between school staff and pupil and family units, and to improve training of school staff (Jessiman et al., 2022). Further evaluation of wider school policy and IE implementation in regards to SEND pupils or pupils of vulnerable backgrounds, such as providing different accommodations depending on pupil and parental feedback and clear communication between involved parties, might also be a worthy point of investigation. Such recommendations to alterations of implementation may help in improving the school environment at the whole-school level, by prioritising the voices of children in communications with staff (Hall, 2010).

In order to maintain a positive, productive, and healthy classroom environment, schools might consider reevaluating their implementation of IE and related practices so as to avoid the potential problems associated by parents with IE in this study. School climate and school experiences are complex, and ambiguity exists between framing of disciplinary practices as either an academic concern or a safety concern (Wang and Degol, 2016). Considering the complex relationships between academic domains, determining how best to manage a classroom, promote pupil learning, and maintaining safety concerns is therefore important (Wang and Degol, 2016). As such, further investigating IE as an evolving part of school climate and the whole-school approach could be beneficial. Participant responses of the current study might suggest such policy and practice changes as formally regulating communication between pupil and parent parties and school faculty when providing punishment, care, or behavioural correction, as well as focusing on evaluating duration and frequency of IE practices over time. Additionally, reintegration of pupils into the mainstream school environment is an important factor post fixed-term exclusion and involves careful planning (Department for Education, 2022; Graham et al., 2019), so focusing on developing and refining similar reintegration processes and developing a positive school culture and climate post IE might be beneficial to certain children, such as those with SEND.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Considering IE experiences are an underexplored area in education, it is important to study the wider impacts of IE on the MH of YP and their parents, as parents are often influential in education experiences, student achievement, and the MH journeys of adolescents (Wang and Sheikh-Khalil, 2014). A strength of this study was its coverage of parents with personal experience of having children in IE across the UK, as well as the inclusion of parents of children with a wide range of SEND. Semi-structured interviews also allowed for participants to speak freely on their experiences, elaborate their thoughts, viewpoints, and emotions, and reveal aspects of personal experiences in an informative way (Campbell et al., 2011). Even so, the limited inclusion criteria, as well as the difficulties of discussing school and MH as a subject matter, may have contributed to difficulties with recruitment.

A limitation of the study is that the sample size for the survey was small and lacked diversity in terms of socio-demographic characteristics. This means that views of parents from underrepresented groups who may have experiences that differ from the participants in this study were not captured. Also, while the qualitative nature of the study limits drawing conclusions about causal effects of IE, it highlights potential gaps in knowledge regarding longitudinal relationships between parents and schools and parents and their children in the context of IE. Additionally, while the parental perspectives of the current study are valuable to examine qualitatively when considering potential impacts of IE, such a selected sample can be limited in scope and cannot fully touch upon IE as a practice across the entirety of the UK. As such, future studies additionally examining the wider perspectives of pupils, teachers, and other related school staff could help researchers further compare IE practices among various involved individuals within school communities and help to shed light on more diverse and evolving perspectives and IE implementation across the UK. Future studies could also benefit from inquiring with parents with less professional experience in fields related to education or SEND or in comparing implementation across specific regions. Limitations regarding generalisability and representativeness could also be addressed by approaching more underrepresented groups by utilising patient and public involvement (PPI) strategies and consultation.

5 Conclusion

These findings give a glimpse as to how parents perceive the variety by which IE is implemented in the UK as well as some mixed or negative receptions to IE practices, through highlighting unique parental perceptions of a counterproductive nature of implementation and the resulting breakdown of trust with school systems. Parents of pupils with SEND and other learning difficulties find it particularly tough to cope with aspects of IE and as such, further research into the connections between IE and long-term MH and academic impacts would be beneficial to help continually evaluate education and discipline both for involved pupils but also within the wider family unit.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data may be available upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YW1iMjc4QGNhbS5hYy51aw==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Cambridge University Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE.2022.116). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. A-MB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the parents who gave their time to participate in the study. We would also like to thank those individuals and organisations who supported recruitment efforts and spread word of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1519110/full#supplementary-material

References

Barker, J., Alldred, P., Watts, M., and Dodman, H. (2010). Pupils or prisoners? Institutional geographies and internal exclusion in UK secondary schools. Area 42, 378–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00932.x

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Burton, D., and Goodman, R. (2011). Perspectives of SENCos and support staff in England on their roles, relationships and capacity to support inclusive practice for students with behavioural emotional and social difficulties. Pastoral Care Educ. 29, 133–149. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2011.573492

Campbell, R., Pound, P., Morgan, M., Daker-White, G., and Britten, N. (2011). Evaluating meta-ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol. Assess. 15:43. doi: 10.3310/hta15430

Condliffe, E. (2023). ‘Out of sight, out of mind’: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of young people’s experience of isolation rooms/booths in UK mainstream secondary schools. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 28, 129–144. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2023.2233193

Cushing, I. (2021). Language, discipline and ‘teaching like a champion’. Br. Educ. Res. J. 47, 23–41. doi: 10.1002/berj.3696

CYPMHC. (2022). School Behaviour Policies are Ineffective in Creating Change, According to Findings from a New Survey. London: Children & Young People’s Mental Health Coalition.

DCSF (2009). Internal Exclusion Guidance. Schools and Families Department for Children, 1-6. London: DCSF Publications.

Department for Education (2012). Pupil Behaviour in Schools in England. London: Department for Education.

Department for Education (2016). The Link Between Absence and Attainment at KS2 and KS4. London: Department for Education.

Department for Education (2022). Suspension and Permanent Exclusion from Maintained Schools, Academies and Pupil Referral Units in England, Including Pupil Movement. London: Department for Education.

Department for Education (2024). Behaviour in Schools: Sanctions and Exclusions. London: Department for Education.

Desforges, C., and Abouchaar, A. (2003). The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievements and Adjustment: A Literature Review. Nottingham: DfES Publications.

Ford, T., Parker, C., Salim, J., Goodman, R., Logan, S., and Henley, W. (2017). The relationship between exclusion from school and mental health: A secondary analysis of the British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Surveys 2004 and 2007. Psychol. Med. 48, 1–13. doi: 10.1017/S003329171700215X

Gill, K., Quilter-Pinner, H., and Swift, D. (2017). Making The Difference: Breaking the Link Between School Exclusion and Social Exclusion. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Gillies, V., and Robinson, Y. (2012). ‘Including’ while excluding: Race, class and behaviour support units. Race Ethnicity Educ. 15, 157–174. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2011.578126

Gilmore, G. (2012). What’s so inclusive about an inclusion room? Staff perspectives on student participation, diversity and equality in an English secondary school. Br. J. Special Educ. 39, 39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2012.00534.x

Gilmore, G. (2013). ‘What’s a fixed-term exclusion, Miss?’ Students’ perspectives on a disciplinary inclusion room in England. Br. J. Special Educ. 40, 106–113. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12029

Graham, B., White, C., Sumner, A. L., Potter, S., and Street, C. (2019). School Exclusion: A Literature Review on the Continued Disproportionate Exclusion of Certain Children. London: Department for Education.

Hall, S. (2010). Supporting mental health and wellbeing at a whole-school level: Listening to and acting upon children’s views. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 15, 323–339. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2010.523234

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Jessiman, P., Kidger, J., Spencer, L., Geijer-Simpson, E., Kaluzeviciute, G., Burn, A. M., et al. (2022). School culture and student mental health: A qualitative study in UK secondary schools. BMC Public Health 22:619. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13034-x

Martin-Denham, S. (2020). An Investigation into the Perceived Enablers and Barriers to Mainstream Schooling: The Voices of Children Excluded from School, Their Caregivers and Professionals. Sunderland: University of Sunderland.

McCluskey, G., Riddell, S., and Weedon, E. (2015). Children’s rights, school exclusion and alternative educational provision. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 19, 595–607. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.961677

Mills, M., and Thomson, P. (2018). Investigative Research into Alternative Provision. London: Department for Education.

NICE (2022). Social, Emotional and Mental Wellbeing in Primary and Secondary Education. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Noguera, P. A. (2003). Schools, Prisons, and Social Implications of Punishment: Rethinking Disciplinary Practices. Theory Into Pract. 42, 341–350. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4204_12

Parker, C., Paget, A., Ford, T., and Gwernan-Jones, R. (2016). ‘.he was excluded for the kind of behaviour that we thought he needed support with…’ A qualitative analysis of the experiences and perspectives of parents whose children have been excluded from school. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 21, 133–151. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2015.1120070

Povey, J., Campbell, A., Willis, L. D., Haynes, M., Western, M., Bennett, S., et al. (2016). Engaging parents in schools and building parent-school partnerships: The role of school and parent organisation leadership. Int. J. Educ. Res. 79, 128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2016.07.005

Power, S., and Taylor, C. (2020). Not in the classroom, but still on the register: hidden forms of school exclusion. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 24, 867–881. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1492644

Rainer, C., Le, H., and Abdinasir, K. (2023). Behaviour and Mental Health in Schools. London: Children & Young People’s Mental Health Coalition.

Rhodes, I., and Long, M. (2019). Improving Behaviour in Schools Guidance Report. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

Sealy, J., Abrams, E., and Cockburn, T. (2021). Students’ experience of isolation room punishment in UK mainstream education. ‘I can’t put into words what you felt like, almost a dog in a cage’. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 27, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1889052

Skipp, A., and Hopwood, V. (2017). Case Studies of Behaviour Management Practices in Schools Rated Outstanding. London: Department for Education.

Tejerina-Arreal, M., Parker, C., Paget, A., Henley, W., Logan, S., Emond, A., et al. (2020). Child and adolescent mental health trajectories in relation to exclusion from school from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 25, 217–223. doi: 10.1111/camh.12367

Toth, K., Cross, L., Golden, S., and Ford, T. (2023). From a child who IS a problem to a child who HAS a problem: Fixed period school exclusions and mental health outcomes from routine outcome monitoring among children and young people attending school counselling. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 28, 277–286. doi: 10.1111/camh.12564

Wang, M. T., and Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 315–352. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1

Keywords: qualitative research, parents’ experiences, secondary school, mental health, parent perspectives, internal exclusion

Citation: Trippler K, Anderson J and Burn A-M (2025) Internal exclusion as a “dumping ground”: analysis of the perspectives of parents whose children have experienced internal exclusion in UK schools. Front. Educ. 10:1519110. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1519110

Received: 29 October 2024; Accepted: 16 January 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

Darren Moore, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Simon Benham-Clarke, University of Exeter, United KingdomAlexandra Sewell, University of Worcester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Trippler, Anderson and Burn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anne-Marie Burn, YW1iMjc4QGNhbS5hYy51aw==

Kiana Trippler

Kiana Trippler Joanna Anderson

Joanna Anderson Anne-Marie Burn

Anne-Marie Burn