94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 06 February 2025

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1472724

This article is part of the Research Topic Advancing Equity: Exploring EDI in Higher Education Institutes View all 12 articles

Fatma Refaat Ahmed1*†

Fatma Refaat Ahmed1*† Ramadan Ezat Awad1

Ramadan Ezat Awad1 Huda M. Nassir1

Huda M. Nassir1 Shahd Tarek Mostafa1

Shahd Tarek Mostafa1 Batool Ghiath Oujan1

Batool Ghiath Oujan1 Basem Ali Mohamed1

Basem Ali Mohamed1 Loai A. H. Abumukheimar1

Loai A. H. Abumukheimar1 Mini Sara Abraham1

Mini Sara Abraham1 Nabeel Al-Yateem1

Nabeel Al-Yateem1 Muna Al-tamimi1

Muna Al-tamimi1 Richard Mottershead1

Richard Mottershead1 Jacqueline Maria Dias1

Jacqueline Maria Dias1 Muhammad Arsyad Subu1

Muhammad Arsyad Subu1 Mohannad Eid AbuRuz2

Mohannad Eid AbuRuz2Aim: To describe the lived experiences of expatriate students enrolled in an academic institution in the UAE and explore suggested improvement strategies to address their challenges.

Background: Exploring the experiences of expatriate students is crucial for three main reasons. First, expatriate students play a key role in the UAE’s sustainable socio-economic development and diversification. Second, cultural differences among expatriate students raise personal, social, and academic challenges, including pedagogical issues concerning teaching and learning styles and effectiveness. Third, given the global importance of internationalization, expatriates’ experiences should be considered an issue of customer satisfaction.

Method: A descriptive, qualitative, narrative study using indirect Colaizzi content analysis of 23 expatriate students’ reflections on their experiences and suggested recommendations.

Results: The consistent themes cited by participants concerning their experiences centered on dormitory-study life balance, socialization and support networks, and navigating financial challenges. They identified areas for improvement in terms of professional, social, peer, and self-support.

Conclusion: Developing an effective support system is essential to ensure a smooth expatriate student experience. The study findings propose suggestions and recommendations that may help in future planning, including maximizing professional support, providing peer tutoring, boosting academic advising and consultation, encouraging student socialization, and guiding self-development as necessary.

• First-year expatriate students commonly suffer loneliness and homesickness.

• Educational internationalization mandates student customer satisfaction.

• Effective support systems are essential to improve student experiences.

UAE exhibits a rising trend of internationalization in its universities, which attract students and staff from across the globe. In recent years, it has been attracting an increasing number of expatriate students, aided by Emirati universities actively establishing partnerships and collaborations with higher educational institutions worldwide (Qiqieh and Regan, 2023; Tahir, 2023). Expatriate students can remain in UAE after graduation, and their expertise plays an important role in the growth of a competent workforce and being retained in the pool of local labor, increasing the attractiveness of the local economy for domestic and foreign investors (De Bel-Air, 2018). In this regard, exploring the experiences of expatriate students is crucial as a key dimension of academic/educational sector performance per se, and as an indicator of the macroeconomic performance of UAE in achieving economic diversification and sustainable development. Furthermore, exploring expatriate students’ experiences and recommendations offers direct insights into how educational services can be improved, pedagogically and in terms of the holistic personal and social experience offered by UAE institutions of learning (Qiqieh and Regan, 2023).

The experiences of expatriate students in Saudi Arabia often include blessings and challenges, functioning in a different educational system and cultural setting at a great distance from their families and current social support links (Alasmari, 2023; Horne et al., 2018). The UAE is a federal union of the eponymous “Emirates,” and it should be noted that students living in UAE moving from one constituent Emirate to another to study in a university share the same challenges as those from outside the UAE. Albeit these students are in a relatively more familiar environment (i.e., UAE), they still experience challenges in adapting to the university environment, missing their families and experiencing “considerable cultural dissonance” (Allan, 2003). Thus, for the purposes of this study, students who have moved to Sharjah specifically to study in a university, whether from other Emirates within UAE or from outside UAE, are considered to be expatriate students.

The transition to new academic and living environments, social networks and an increased amount of independence can be very stressful. The first year in university is especially crucial, as those who struggle with the transition may fail in their studies and drop out. Similar common challenges are typically encountered and must be addressed by university service providers (including technology integration, in addition to student engagement into the academic and social experience). Universities have traditionally focused on academic challenges, and unfamiliar learning contexts and teaching styles, curriculum design, teacher characteristics (e.g., language or accent barriers), and the natural, inherent demands of tertiary education all contribute challenges for academic performance among first-year students (Deuchar, 2023). Aside from the academic dimension, students can encounter profound sorrow, as they have to depart from their family and friends to study remotely. Homesickness and loneliness are among the earliest emotional issues that are common especially among these students due to a lack of social support, which have been widely reported worldwide (Hack-Polay and Mahmoud, 2021; Platanitis, 2018). Social support networks can assist in managing such emotional issues. Perceived social support refers to the belief that the surrounding environment offers assistance. This support can manifest in several forms: the availability of help when required, offering services as substitutes for traditional ones that expatriates may lack, or facilitating adaption to new life circumstances (King et al., 2006; Leach, 2014).

According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, an individual’s development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from immediate surroundings (e.g., family) to broad societal structures (e.g., culture). The theory has significant implications for educational practice and for understanding diverse developmental contexts. This emphasizes the importance of paying attention to expatriate students worldwide (Guy-Evans, 2024). Although some recent studies have tentatively begun to explore students’ transition experiences during studying in UAE (Mikecz Munday, 2021; Qiqieh and Regan, 2023), there is a paucity of analyses exploring their particular experiences regarding learning, accommodations, and cultural settings. The roles of the experiences of students with support services, health, and safety services are missing in the current literature. With this study, we hope to fill this void. This study provides valuable insights into the experiences and challenges of expatriate health sciences students at an Emirati university, contributing to expatriate studies by highlighting specific social, cultural, and academic adjustments. It underscores the need for tailored institutional support and informs policy decisions to enhance the global student experience. By identifying relevant patterns, the study contributes to discussions on student mobility and educational equity, advocating for inclusive educational environments that support diversity. Ultimately, it aims to shape international strategies for improving the academic and overall wellbeing of expatriate students, establishing a model for future research in diverse contexts. Therefore, this study aims to address these issues in the literature and poses two research questions: (RQ1) What are the experiences students have in adapting to the educational and socio-cultural environment at the university? and (RQ2) What type of support could be provided to facilitate students’ adjustment process to the educational and socio-cultural environment of the university?

The objective of this study is to describe the lived experiences of students enrolled in an academic institution in UAE. Specifically, we seek to explore suggested improvement strategies in dealing with students’ challenges.

A qualitative approach is recommended to gather comprehensive details of an event. This study used a descriptive qualitative phenomenological design (Colaizzi, 1978), which allowed us to obtain a deep understanding of the experiences of students at the University of Sharjah’s College of Health Sciences. We also sought their suggestions for effective adjustment and improvements. The sample included the seven departments in the College. Health sciences students typically undergo extensive training hours and work irregular shifts, which differs significantly from those in programs with more predictable schedules. As a result, they often face greater conflict between their training commitments and family obligations, and they may also experience heightened stress levels (Fitzgibbon and Murphy, 2023). Similarly, expatriates relocating from other Emirates often struggle to organize their weekend schedules to spend time with their families, often leading them to remain in dormitories for extended periods throughout the semester.

The participants in this study consisted of first-to-fourth-year students, aged 18–23, encompassing both genders and a diverse range of majors in health sciences and nationalities. These students are the children of expats (i.e., non-Emiratis who finished high school in UAE and then went to university there or from outside UAE). Selection criteria for the study involved purposive sampling methods (Campbell et al., 2020). This strategy allowed the inclusion of a sample that was diverse in terms of age, gender, and different backgrounds.

A list of students was prepared, and recruitment was managed via emails that were sent to the students. All responses were collected by the research team. Data saturation occurred after analyzing information gathered from 23 students, as their responses consistently yielded similar findings. Consequently, it became clear that including more participants would not yield novel insights, data and new themes.

In-depth interviews were used to collect participants’ experiences. Data were collected during the Spring semester for the academic year 2023/2024. Participants completed semi-structured individual interviews that were developed by the authors and conducted by trained data collectors. The interviews lasted around 30 min and were held face-to-face, in English (the medium of instruction and an academic requirement for all healthcare programs in UAE). Table 1 presents the sequence of interview questions. All interviewers received training (12 h) on how to interpret and deliver the interview guide to elicit consistent information across all interviews. We used individual interviews to provide privacy and ensure confidentiality for participants, thereby allowing them to talk freely about their experiences, challenges, expectations and suggested recommendations to be considered in the future. All interviews were audio recorded, and important points and nonverbal cues (i.e., laughter, silence, tone of voice, eye contact, sighs) were immediately transcribed using field notes.

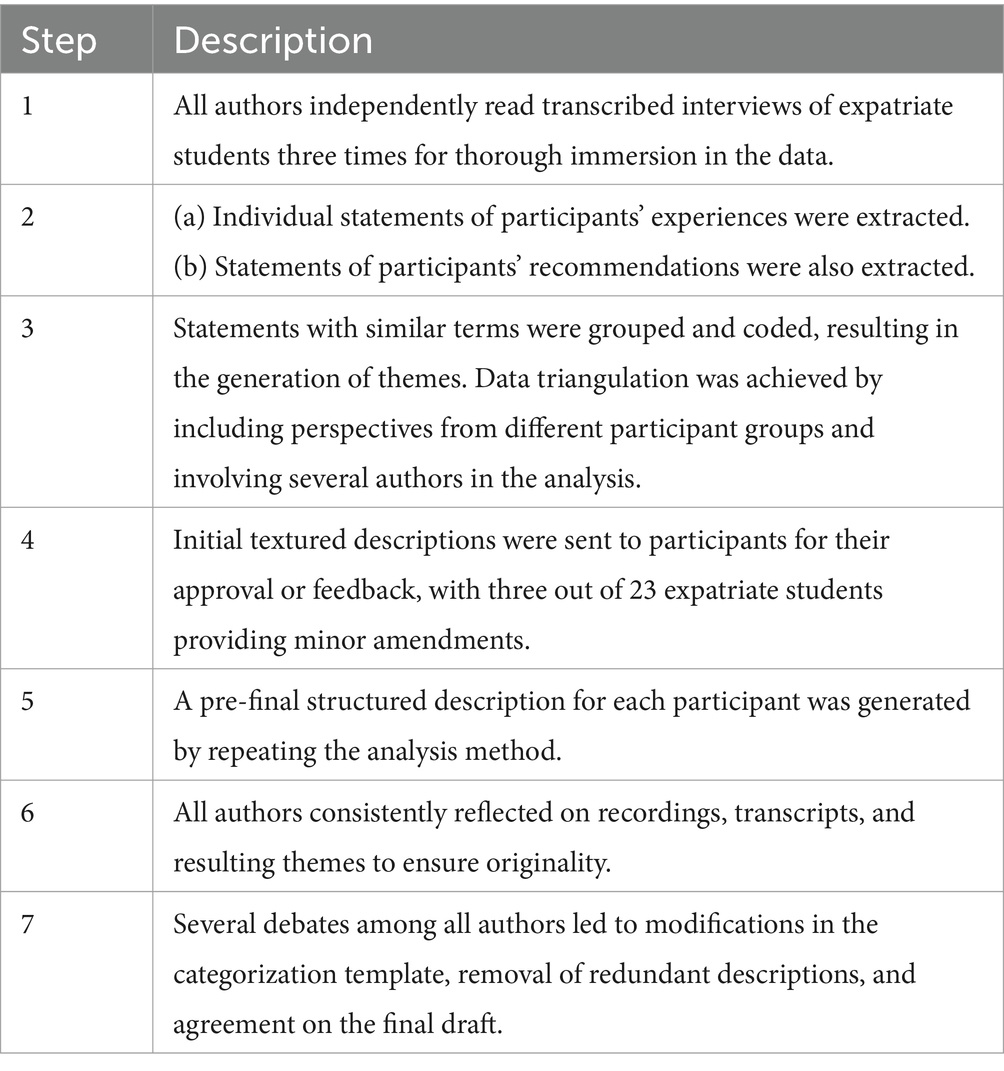

Data were analyzed using the method of Colaizzi (1978) (Table 2), which is a rigorous and robust approach that ensures the credibility and reliability of results. This method allows researchers to identify emerging themes and their relationships clearly and logically, revealing the structure of the experience under study. It has been widely used to explore the pedagogical experiences of healthcare students (Yao et al., 2024). In this research, the experiences and recommendations of students were analyzed. Analysis began by interpreting each statement in terms of its significance to participants’ experiences.

Table 2. Data analysis was conducted following Colaizzi’s (1978) method.

Narratives were reviewed multiple times to understand the underlying phenomenon. Horizontalization was employed to give equal weight to each statement, grouping similar statements into theme clusters. These clusters were synthesized into detailed descriptions that captured the richness of the themes. A structured description of the experience was developed through iterative analysis, ensuring authenticity through continuous review and reflection by the research team on interview transcripts and resulting themes. The categorization matrix underwent revisions through team discussions to refine descriptions and achieve consensus among authors. A draft of the findings was shared with expatriates students for validation before finalizing the report.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study findings, four methodological aspects were considered in this study: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Forero et al., 2018). Credibility was ensured by involving students of all genders, with different backgrounds, academic levels and varied qualifications from different majors. In addition, piloting was done by asking a few participants to check their interview transcripts to ensure that their intended meaning had been captured and revealing how cultural norms, values, and experiences influence the researcher’s interactions with participants and their interpretations. In terms of transferability, the research was fully explained in the study report and all study stages, including study context, sampling method, and data collection, were recorded to enable scrutiny by readers. We developed a detailed track record of the data collection process and implemented reflexive journals and weekly investigators meetings to dependability and confirmability. To ensure reflexivity, the research team, who were familiar with qualitative research methodology, was engaged during the research process to discuss the methodology and findings and identify any potential biases that might have been overlooked.

The Research Ethics Committee (REC-23-12-10-01-S) of the University of Sharjah gave its approval prior to the study’s execution. All interviews were anonymized, and a code number was assigned to each participant. The principal investigator encoded the identities of the participants as “S” with the number assigned to interviewed students. All recorded interviews were downloaded onto a private password-protected computer at the main researcher’s office. The content of all interviews (e.g., audios and transcriptions) were only accessible to the researchers. Participants were free to join or leave the study at any time without any consequences to avoid the effect of power imbalance that might exist between researchers and students. They got the chance to ask questions and were provided with confidentiality assurances to avoid any misunderstandings resulted from culture differences. Before participating, each student was asked to sign a consent form. The researchers ensured that ethical issues including plagiarism, uninformed consent, misconduct, data manipulation, and redundancy were handled appropriately.

In total, 23 expatriate health sciences students (8 males, 15 females) aged 18–23 years participated in this study from different nationalities. Verbatim transcripts of the interviews provided the data from which the essence of the experience emerged. Themes were constructed by highlighting words and statements that were common to the interviews and essential in their meaning. This essence is encompassed in two main themes: “experiences of expatriate health sciences students” and “recommendations from students’ perspectives to improve their experiences.” Understanding these dynamics is crucial for enhancing student wellbeing and academic success in similar educational environments.

The vivid nature of the experiences and the mix of feelings became apparent in the students’ stories of being independent and in a new culture and university setting. The most persistent theme which students imparted was the challenges they faced initially and how they could overcome them. These experiences mainly focused on university dormitory-study life balance, socialization and support network, financial challenges, and looking to fit in, as described below.

Living in university dormitory s can be an adventure filled with new experiences and opportunities for personal growth, but it also comes with its fair share of challenges. From navigating communal living to their managing academic responsibilities amidst distractions, university dormitory life presents a unique set of challenges. Living in university dormitory requires students to manage responsibilities independently, for example, academics, chores, and other household burdens.

“The study here is a little bit expensive, and it feels very creepy to be alone all the time”. (S1)

This newfound autonomy fosters personal growth but presents challenges like time conflicts and balancing personal life with studies.

“Cooking wasn’t that easy; when you come back, you’re tired and hungry, which also adds some mental stress”. (S5)

The interconnected commitments and roles of being a university student and living alone required significant time and energy from the students, and some complained about being tired and confused.

“I feel tired… the tasks are really many, I get lost among my new role”. (S2)

There was further pressure reported during the initial transition into university, when students described the difficulty as they found gaps in their academic skills. This would hinder their academic progress. S9 reflected upon the moments of uncertainty related to their academic requirements. Examples include writing papers, gaining sufficient computer skills, and meeting faculty expectations. Students felt they were not ready for the demanding pace and extensive reading requirements.

“Since the intensity is constant, I believe the initial year is likely the most challenging, as one adjusts to everything”. (S9)

“I was challenged with the academic requirements… they are completely different from the school experience”. (S1)

“The multiple roles encountered, make me feel overwhelmed… despite being a senior student, I am still struggling with how to balance the dorms-study life”. (S3)

“I am satisfied with services provided by the dormitory s, for example, satisfactory serving of quality food, students’ club center, gym, library, high-speed internet and medical care. However, we have self-responsibility towards personal and academic matters that overwhelm our daily life”. (S18)

An Arabic student (S11) commented on the challenge of language barriers that can exacerbate the already existing academic pressure:

“We usually face some problems with the language in personal and academic life … in fact, the issue is that they might use a different English pronunciation”.

For some students, interacting with people coming from different backgrounds/cultures and adjusting to a new language while navigating communal living was considered overwhelming. Miscommunication due to language and cultural differences m exacerbate social isolation.

“Sometimes, I have conflicts with people who hold different opinions because they feel that the meaning or value of what we’re arguing about is more important to them than it is to me”. (S3)

Additionally, the intense academic environment of universities can heighten the pressure to excel academically, adding to the stress of adapting to dormitory life. Participants experienced studying in a new place, knowing nobody when they initially arrived, and in some cases not trusting strangers. While facing a myriad of academic issues, this time period was clouded with personal concerns and difficulties.

“Maybe I didn’t joke because I didn’t know them… trusting people and finding real friends”. (S11)

On the other hand, more experienced (senior) students recalled happier memories of good times.

“We created a myriad of memories with our classmates, however, at time of study and exam, it was hard to have entertainments”. (S4)

Most of students experienced depression, stress, nostalgia, loneliness, felt homesick and missed their families at various times during their first-year study. However, those who had a family member living with them or who had close friends experienced the symptoms less intense and fewer negative emotions.

“I initially struggled, due to being in an unfamiliar environment without friends or acquaintances from my previous circle”. (S1)

“When you don’t have anyone to say anything to, you just feel lost, because there’s no one to either guide you or to listen to you”. (S6)

“I faced challenges in initiating social interactions and forming connections with my classmates. This struggle affected my ability to find a support network and contributed to feelings of loneliness and alienation during the early years in the program”. (S2)

A male student (non-Arab) raised an important issue in terms of social network and cultural background posing socialization challenges, especially in interactions with females.

“Cultural differences and social barriers within the university environment added some challenges to me, particularly in interacting with female peers and maintaining boundaries”. (S3)

Given that most of students had to rely on their parents or other family members for financial support, they could be predisposed to feel financial stress in regard to their financial requirements. Many students were worried about their financial situation.

“Sometimes I want to buy something, but because I usually have limited amount of money for living expenses, I couldn’t”. (S8)

“I get embarrassed every time I ask my father for extra money… I prefer to forego my needs rather than burden him with extra expenses”. (S7)

The consistent theme which students imparted was the challenges they experienced initially as they began their journey of loneliness, homesickness, and crossing cultures. However, these experiences were interwoven with feelings of independency and self-control. In this regard, senior students stated:

“Aside from the hard moments, I feel stronger right now than before”. (S18)

“I can face any other challenges that I might face… I feel like this has made me more independent and self-controlled”. (S20)

“I can deal with any potential fears and frustrations after I lived these experiences… I am ready to graduate, join a new working environment, travel abroad, and so on”. (S17)

The content analysis revealed that students’ recommendations encompassed three dimensions: university (i.e., the professional sphere), peers, and self, capturing messages to facilitate students’ adjustment process. As the students lived a rich experience of expatriation, those fitting in offered suggestions for other expatriates. These messages enclosed advice, recommendations, and suggestions that might help in managing students’ stress or difficult emotions, maintaining their mental wellbeing, and enabling them to navigate challenges with resilience and adaptability.

Participants recommended that future students should get benefit from the services provided by the deanship of student affairs for both co-curricular and extra-curricular activities.

“The orientation sessions were crucial to lessen the confusion I was felt… There are lots of useful activities on campus, for example, sports activities, events, and competitions in different fields”. (S21)

Another student drew attention to the language lab and recommended its services.

“When I struggled in language…. my academic advisor advised me to visit the language lab and check its services… I really got benefits that time”. (S12)

In addition to these recommendations, lot of students also emphasized the value of one-to-one consultation sessions with professionals in their respective fields. These consultations were regarded as essential opportunities to gain specialized insights, expert advice, and career guidance tailored to individual aspirations and academic pursuits. Students highlighted the unique advantage of interacting directly with professionals who could offer firsthand knowledge, industry-specific advice, and practical strategies for success.

“We need a person that can debrief and advise students that are going through different academic issues”. (S2)

The personalized nature of these consultations allowed students to address specific concerns, explore career pathways, and receive mentorship from professionals. Similarly, other students asked for personal consultations with professionals to enhance their adjustment process, either as expatriates or newly transferred undergraduates entering tertiary education. They expressed the strong need for initiating a students’ office and promoting continuous student-professional communications.

“Sometimes I need to talk with a consultant… I mean… talking to someone who is professional and able to guide me”. (S11)

“Lots of issues, like self-esteem, self-control, social support, self-efficacy… need to be strengthened… Of course, I need someone to give me a hand”. (S15)

“My parents are available all the time, we communicate regularly; however, there are some issues I prefer not to disclose, therefore, the presence of a special office that could meet our needs as expatriates is essential” (S13).

Students added that there are other ways to cope with challenges of expatriation, i.e., socialization and creating support network. Most of the students faced problems with their friendships due to miscommunication and cultural differences. In addition, existing in a new and unfamiliar place alone (i.e., separated from their original friends and family) pushed them to avoid steps toward socialization with their peers in the new environment. However, some senior students reflected that they made active efforts to form new friendships during the fresher period.

“Despite the negative feelings encountered by most of us initially (e.g., depression, loneliness, etc.) plus the fear of getting friend with bad people, we made efforts to find good colleagues and form friendships with trusted people”. (S23)

“When I started developing more friendships, I felt like they [friends] were at the same level of me, we shared similar thoughts and opinions. So, it was much better, as if there were physical friends around me”. (S22)

One of the strategies that helped the students to form good friends and get socialized were trips and events. Students underscored the significance of such informal bonding activities as avenues for fostering meaningful connections with fellow students. Engaging in group activities and outings provided opportunities for students to bond with their peers outside the academic setting, nurturing friendships and support networks that extended beyond the confines of the classroom.

“For me, I would request to do more activities in the university, such as doing more trips, playing more sports and so on”. (S9)

These activities ranged from outdoor excursions to cultural events and team-building exercises, allowing participants to unwind, socialize, and cultivate a sense of belonging within their academic community. Moreover, participants emphasized the importance of stepping out of their social circles and comfort zones to meet new people from diverse backgrounds and disciplines. By embracing opportunities for cross-disciplinary interaction and networking, participants expanded their perspectives, enriched their social experiences, and developed valuable interpersonal skills essential for their personal and professional growth.

Another message derived from the content analysis concerned the importance of communication. Students emphasized that communication plays a pivotal role in their experiences, facilitating their integration into new environments and fostering a sense of belonging. For them, effective communication with family, friends and colleagues is essential for building relationships, both within academic settings and the broader community.

“Communication with my colleagues and my classmates in major helps me to enlarge my social circle, and as a university student this has helped me a lot later on in my practical courses, to be involved with other professionals and healthcare providers”. (S4)

These proficient communication skills are vital for academic success, as they facilitate collaboration with peers, participation in class discussions, and understanding of course materials. On the other hand, many of students articulated that they did not get the chance to communicate with their families often during their early transition, because of numerous reasons, including time differences and the academic pressures they encountered.

“There’re time differences between my sister and I, time zone disparities create scheduling conflicts. Frequently, I lose motivation, and grapple with difficulties throughout the day, and there’s no one for me to tell. So, it kind of brings me down a bit… and it did affect my grades at some points”. (S8)

Most students enrolled in health science programs, expressed a strong preference for one-to-one consultation sessions (peer tutoring) with older or senior peers as a valuable resource.

“If we have someone older to give us advice, it will improve our academic progress, and all of these things… they could understand us easily”. (S1)

Additionally, students noted the benefit of receiving tailored guidance that resonated with their individual goals and circumstances, which they believed was best facilitated through these personalized interactions. In addition to one-to-one consultation session, group consultation sessions with peers from the same college emerged as another favored approach among students.

“So, I think it would be very nice to have like a peer group of people who they can relate to”. (S5)

These sessions provided a dynamic forum for collective problem-solving, knowledge-sharing, and mutual support within a collaborative setting. Students valued the diversity of perspectives and experiences that group sessions offered, allowing for the exploration of different strategies and solutions to common challenges.

Students reflected on the strategies they themselves had and continued to utilize in order to overcome the challenges they experienced. For example, some revealed the importance of time management, and how it was difficult to apply it in their first years. They mentioned how efficient time management allows students to balance their academic responsibilities with opportunities for cultural exploration and social integration. By prioritizing tasks, setting realistic goals, and establishing a structured schedule, students can maximize productivity and minimize stress. They attended related workshops in this regard to be able to effectively manage their time. They tried to allocate sufficient time for language learning, networking, and engaging in extracurricular activities, which are essential for personal growth and integration into the host community.

“One of my coping mechanisms I’ve used is the time management, I really struggled to imply it in my first few months of university, but it was beneficial where I always set a strict daily routine for myself, which helped me stay busy most of the time and to keep everything in check”. (S9)

In addition to attending workshops, seminars and seeking advice, students watched motivational videos to improve their resilience, self-efficacy, and self-control. They believed that these strategies might empower them to make the most of their overseas experience and achieve both academic and personal success.

“I watched many videos, went a hundred times to my academic advisors, attended self-development workshops, and sought advice from seniors to be able to overcome this stage”. (S19)

UAE is among the leading global countries experiencing an increasing trend of internationalizing its universities, attracting students and staff from diverse nationalities worldwide. Consistent with this trend, the present study explored suggested improvement strategies in dealing with expatriate students’ challenges, deriving from the analysis of their lived experiences in UAE. This study used a qualitative phenomenological approach; 22 in-depth interviews were held with expatriate students. This approach allowed a deep understanding of their experiences, revealing strategies that can enhance future students’ experiences.

Our main findings were related to the “experiences of expatriate health sciences students,” specifically relating to university dormitory-study life balance, socialization and support network, financial challenges and looking to fit. These were “must-hear” messages from experienced students’ perspectives to ensure smooth experiences for future students. Despite the students providing satisfactory feedback toward the dormitory s themselves, missing the home environment, meals, and comfort remained vital to those who lived in the dormitory. Therefore, in addition to the academic challenges they faced as new transferring students, they were challenged with keeping the balance between their dormitories and academic life. This experience was similar to findings reported from previous studied in the Gulf region (Alasmari, 2023; Qiqieh and Regan, 2023) and other expatriate learning contexts (Deuchar, 2022; Qadeer et al., 2021; Tajvar et al., 2024).

In this regard, students recommended that their future colleagues should commit to the attendance of orientation sessions held by the university, join the language lab to improve their language skills, and interact with professionals (i.e., attending advising sessions held by academic advisors, and asking for peer tutoring). These consultations are crucial chances to receive specialized insights, expert guidance, and career advice customized to students’ personal aspirations and academic goals. Through establishing stability in their academic lives, students can manage their new personal lives more efficiently (Alasmari, 2023; DeLuca, 2005; Pološki Vokić et al., 2021).

This experience of imbalance could be an important contributor to students’ emotional challenges, which were triggered by their feelings of homesickness and loneliness, as reported in previous studies (Li et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2023). However, to overcome these challenges, Alasmari (2023) suggested that students might form friendships with local residents, possibly due to the encouraging demeanor of colleagues, and university administrators.

In the present study, students agreed that social support offers opportunities for perspective-taking and problem-solving, as friends and loved ones may offer insights or solutions that individuals might not have considered on their own. By participating in various trips and events, they were able to manage feelings of loneliness. These nurturing social connections and fostering a supportive network can enhance coping abilities and contribute to overall wellbeing of the students. This finding supports previous studies in this regard (Li et al., 2021; Khawaja and Stallman, 2011). Moreover, communication with peers was revealed in the present study to be a way of empowering students to adapt successfully to new environments and thrive academically and socially, consistent with Oktavianti et al. (2024).

In terms of financial matters, besides the tuition fees, there are expenses incurred by students. Despite, the services offered by the department of student affairs, i.e., good quality food, high-speed internet, library, medical care, and transportation services, students were still in need to some other expenses that might cause some financial stress, which is commonly reported worldwide (Mikecz Munday, 2021).

In terms of peer support, students showed a preference toward having regular peer tutoring sessions. These sessions were highlighted as instrumental in providing a personalized and supportive environment for discussing academic challenges, navigating career aspirations, and seeking advice on personal development (Arthur, 2017; Chantaraphat and Jaturapitakkul, 2023). The intimate nature of these consultations fostered a sense of trust and comfort, allowing for open dialogue and the exchange of valuable insights. The University of Sharjah has initiated a peer tutoring system as one of the forms of academic support it offers to all students. The sense of camaraderie and solidarity fostered within peer support groups created a supportive community where students felt empowered to engage in meaningful discussions and receive feedback from their peers. Furthermore, group sessions also could facilitate the exchange of resources and practical tips, enhancing students’ learning experiences beyond the confines of traditional classroom settings (Page et al., 2019). Students considered that group consultation sessions would provide a rich and interactive platform for mutual learning and growth among peers. However, students preferred having private academic advisors meeting sessions. In addition to peer support, self-support played a significant role in the experience of students in higher education. Using proper measurement tools to evaluate the success of these proposed recommendations is crucial. For example, surveys, focus groups, interviews, and the utilization of existing institutional data tracking systems can help analyze trends in academic performance and student support needs. Additionally, collecting feedback from peer tutors can provide valuable insights. By combining these methods, universities can gain comprehensive insights into the effectiveness of their peer tutoring programs and support initiatives. To our knowledge, previous studies have not addressed this form of support (Alasmari, 2023; Deuchar, 2022; Zheng et al., 2023).

These recommendations are beneficial for all students, although expatriate students would particularly benefit from tailored solutions to their specific challenges. Consequently, the participants in this study expressed a strong need for the university to establish an expatriate students’ office that fosters ongoing communication between expatriate students and university professionals.

While this research study was conducted on a small scale with gender imbalance, and its findings cannot be broadly applied, they may be applicable to comparable settings within transnational universities in the region. Despite the study’s limitations, it identified several issues worthy of further exploration in future studies involving larger student populations with a more balanced sample could further explore gender differences. Moreover, the data in this study were exclusively used for qualitative analysis. Subsequent research into students’ adjustment to life and education in the UAE could consider employing mixed-methods or quantitative approaches. Integrating additional data sources, such as university records, peer observations, or secondary data and including participants from other universities within UAE, would enhance the reliability of the findings and provide a more robust validation of the results.

As higher education in the Gulf region becomes more globalized, it is crucial for university communities to grasp the challenges students face when adapting academically and socially. Developing an effective support system is essential to ensure a smooth students’ expatriation experiences. This study contributed to an in-depth understanding of students’ experiences and recommendations in the UAE. The findings propose suggestions and recommendations that may help in future planning including maximizing professional support, providing peer tutoring, boosting academic advising and consultation, encouraging students’ socialization, and guiding student self-development as necessary. This research should be replicated to include diverse universities in UAE and across the region.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

FA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RA: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HN: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SM: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. BO: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. BM: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. LA: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MiA: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft. NA-Y: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MA-t: Investigation, Writing – original draft. RM: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JD: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MoA: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alasmari, A. A. (2023). Challenges and social adaptation of expatriate students in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 9:e16283. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16283

Allan, M. (2003). Frontier crossings: cultural dissonance, intercultural learning and the multicultural personality. J. Res. Expatriate Educ. 2, 83–110. doi: 10.1177/1475240903021005

Arthur, N. (2017). Supporting expatriate students through strengthening their social resources. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 887–894. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1293876

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., et al. (2020). Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 25, 652–661. doi: 10.1177/1744987120927206

Chantaraphat, Y., and Jaturapitakkul, N. (2023). Use of peer tutoring in improving the English speaking ability of Thai undergraduate students. Reflections 30, 826–849. doi: 10.61508/refl.v30i3.268771

Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. in Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Eds. R. S. Valle and K. Mark (New York: Oxford University Press), 48–71.

De Bel-Air, F. (2018). Demography, migration, and the labour market in the UAE (GLMM - EN - no. 7/2015). Gulf Labour Markets and Migration. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279910786_Demography_Migration_and_the_Labour_Market_in_the_UAE (Accessed on July 9, 2024).

DeLuca, E. K. (2005). Crossing cultures: the lived experience of Jordanian graduate students in nursing: a qualitative study. Expatriate J. Nurs. Stud. 42, 657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.017

Deuchar, A. (2022). The problem with expatriate students’ “experiences” and the promise of their practices: reanimating research about expatriate students in higher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 48, 504–518. doi: 10.1002/berj.3779

Deuchar, A. (2023). Expatriate students and the politics of vulnerability. J. Expatriate Stud. 13, 206–211. doi: 10.32674/jis.v13i2.4815

Fitzgibbon, K., and Murphy, K. D. (2023). Coping strategies of healthcare professional students for stress incurred during their studies: a literature review. J. Ment. Health 32, 492–503. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.2022616

Forero, R., Nahidi, S., De Costa, J., Mohsin, M., Fitzgerald, G., Gibson, N., et al. (2018). Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2915-2

Guy-Evans, O. (2024). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. Simply psychology. Available at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/bronfenbrenner.html (Accessed December 19, 2024).

Hack-Polay, D., and Mahmoud, A. B. (2021). Homesickness in developing world expatriates and coping strategies. German J. Human Resour. Manag. 35, 285–308. doi: 10.1177/2397002220952735

Horne, S. V., Lin, S., Anson, M., and Jacobson, W. (2018). Engagement, satisfaction, and belonging of expatriate undergraduates at U.S. research universities. J. Expatriate Stud. 8, 351–374. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1134313

Khawaja, N. G., and Stallman, H. M. (2011). Understanding the coping strategies of expatriate students: a qualitative approach. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 21, 203–224. doi: 10.1375/ajgc.21.2.203

King, G., Willoughby, C., Specht, J. A., and Brown, E. (2006). Social support processes and the adaptation of individuals with chronic disabilities. Qual. Health Res. 16, 902–925. doi: 10.1177/1049732306289920

Leach, J. (2014). Improving mental health through social support: building positive and empowering relationships : Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Li, Y., Liang, F., Xu, Q., Gu, S., Wang, Y., Li, Y., et al. (2021). Social support, attachment closeness, and self-esteem affect depression in expatriate students in China. Front. Psychol. 12:618105. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.618105

Mikecz Munday, Z. (2021). Adapting to transnational education: students’ experiences at an American university in the UAE. Learn. Teach. Higher Educ. Gulf Perspect. 17, 121–135. doi: 10.1108/LTHE-08-2020-0017

Oktavianti, F., Saper, J. N., Yusida, S. E., and Saleh, G. A. (2024). The relationship between interpersonal communication and peer social support in overseas students. J. Psychol. Soc. Sci. 2, 1–5. doi: 10.61994/jpss.v2i1.80

Page, N., Beecher, M. E., Griner, D., Smith, T. B., Jackson, A. P., Hobbs, K., et al. (2019). Expatriate student support groups: learning from experienced group members and leaders. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 33, 180–198. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2018.1450106

Platanitis, P. (2018). Expatriates emotional challenges and coping strategies: a qualitative study [Doctoral thesis, University of Manchester]: University of Manchester Research Explorer.

Pološki Vokić, N., Rimac Bilušić, M., and Perić, I. (2021). Work-study-life balance–the concept, its dyads, socio-demographic predictors and emotional consequences. Zagreb Expatriate Rev. Econ. Bus. 24, 77–94. doi: 10.2478/zireb-2021-0021

Qadeer, T., Javed, M. K., Manzoor, A., Wu, M., and Zaman, S. I. (2021). The experience of expatriate students and institutional recommendations: a comparison between the students from the developing and developed regions. Front. Psychol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.667230

Qiqieh, S., and Regan, J. A. (2023). Exploring the first-year experiences of expatriate students in a multicultural institution in the United Arab Emirates. J. Expatriate Stud. 13, 323–341. doi: 10.32674/jis.v14i1.4967

Tahir, R. (2023). Expatriate academics: an exploratory study of western academics in the United Arab Emirates. Expatriate J. Manag. Pract. 16, 641–657.

Tajvar, M., Ahmadizadeh, E., Sajadi, H. S., and Shaqura, I. I. (2024). Challenges facing expatriate students at Iranian universities: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med. Educ. 24:Article 210. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05167-x

Yao, Y., Long, A., Tseng, Y. S., Chiang, C. Y., and Sun, F. K. (2024). Undergraduate nursing students’ learning experiences using design thinking on a human development course: a phenomenological study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 75:103886. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2024.103886

Zheng, K., Johnson, S., Jarvis, R., Victor, C., Barreto, M., Qualter, P., et al. (2023). The experience of loneliness among expatriate students participating in the BBC loneliness experiment: thematic analysis of qualitative survey data. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 4:100113. doi: 10.1016/j.crbeha.2023.100113

Keywords: content analysis, healthcare education, health sciences, expatriate students, pedagogical recommendations, UAE

Citation: Ahmed FR, Awad RE, Nassir HM, Mostafa ST, Oujan BG, Mohamed BA, Abumukheimar LAH, Abraham MS, Al-Yateem N, Al-tamimi M, Mottershead R, Dias JM, Subu MA and AbuRuz ME (2025) Ups and downs of expatriate health sciences students: towards an understanding of experiences, needs, and suggested recommendations in an Emirati university. Front. Educ. 10:1472724. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1472724

Received: 29 July 2024; Accepted: 22 January 2025;

Published: 06 February 2025.

Edited by:

Karan Singh Rana, Aston University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Muhammad Noman, Wuhan University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Ahmed, Awad, Nassir, Mostafa, Oujan, Mohamed, Abumukheimar, Abraham, Al-Yateem, Al-tamimi, Mottershead, Dias, Subu and AbuRuz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fatma Refaat Ahmed, ZmFobWVkQHNoYXJqYWguYWMuYWU=

†ORCID: Fatma Refaat Ahmed, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1008-8216

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.