- Center for Research and Intervention in Education (CIIE), Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences (FPCEUP), University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

This paper conceptualizes ‘quality of education’ in the European political discourse. The expression ‘education quality’ and its variations are frequently found in literature and policies at supranational, international, national, and local levels but are not explicitly defined. However, it is assumed to be a goal that countries pursue and has gained prominence in the European context. Acknowledging the European agencies’ legislation’s influence on Member-States’ domestic policies, understanding what “education quality” means is of the utmost importance. Based on the content analysis of political documents issued by several European agencies, this paper categorizes, systematizes, and interprets the European political discourse on education to infer aspects that can compose ‘quality of education’ and develop an understanding of the concept. The analysis resulted in the systematization of three aspects that help to conceptualize the ‘quality’ of education: (i) ‘What is expected of education’; (ii) ‘Components of education quality’; (iii) ‘Priorities for Education’. Based on these aspects, a generic definition was formulated stating that education of quality is oriented toward preparing people to contribute to the social and political project, acquiring knowledge, skills, and competences to be productive; needing motivated and well-prepared teachers and leaders, adequate conditions, and being closely monitored and evaluated. The paper concludes with some recommendations. The paper conclusions could help policy-makers and school professionals in their professional practice and reaching education quality. Nonetheless, by only focusing on European documents addressing ‘quality of education’ the paper may present a narrower perspective that could be complemented by analyzing a wider range of international/transnational documents.

1 Introduction

The quality of education1 has been a topic of concern since the late 90s, given the central place education occupies in modern societies. Globalization and the fast dissemination and access to digital resources made it easier to be aware of our surroundings. This phenomenon had a particular impact in Europe, where since the establishment of the European Union, nations committed to shared, or similar, policies and efforts toward establishing a European identity and force (European Union, 1957). This means that the aims and intentions decided at the macro level in European agencies such as the European Commission, the European Council, and the European Union itself as a governing body of countries with a shared purpose, convey a particular view of social phenomena, education included, that directly impacts national contexts, leading to a common agenda. This dynamic, called Europeanisation (Alexiadou, 2007), creates a certain uniformity within Europe, setting the standards and steering policies and actions.

With this broader awareness came a sense of comparison, raising concerns about the performance of individual nations and, consequently, leading to competition and efforts toward improvement when a particular country is falling below the average. In education, this translated into movements aiming to promote and ensure the quality of educational systems, institutions, and results. Among such efforts was the implementation of educational policies framing the organization of educational systems and curricula and guiding educational processes.

However, Santos Guerra (2003) warns us to be cautious when considering what “quality” means. The author advises against the peril of simplification, for instance, by considering results as quality; of confusion, by considering the attributes of quality as synonyms of the concept; of distortion, ignoring essential components of quality; of technicality, narrowing quality to the application of testing [e.g., PISA (Program for International Student Assessment)]; of comparison, trying to compare unparalleled situations. The author also stresses that everything in education is also political, something already argued by Paulo Freire in the 1960s, which is why it is essential to deeply study policies and what they convey since policies are also an instrument of control, used to shape realities according to a specific ideology, intention or perspective (Apple, 2019). This is particularly important in education, given its role in preparing children and young people for an active life in society as professionals and citizens. To put it in other terms, considering the paramount role school education plays in people’s lives, it is essential to understand and critically analyze what it is that decision-makers are deciding regarding educational contents and practices, the priorities, the aims, and the standards set to education and, ultimately, what is considered an education of quality.

In this setting, this paper attempts to conceptualize the notion of ‘quality of education’ conveyed by supranational – European2 – policies framing and influencing education in Europe and its nations. The goal is not to criticize the recommendations or orientations provided in the policies but to identify the underlying understanding of education quality and/or its components, providing a thorough state-of-the-art analysis and, ultimately, reach a sort of general understanding of the concept of ‘quality of education’, based on the political discourse from the analyzed documents. Notwithstanding, and sustained by the analysis result, the paper attempts to also advance with a suggestion of parameters for defining quality, which could be used at different times and contexts.

The paper draws from the analysis of political documents, such as recommendations, conclusions, studies, and reports concerning education, from European bodies such as the European Commission and the European Council, with references to ‘quality’. Although it is relevant to form a more comprehensive understanding of education quality, including different levels and modalities of education, the research this paper stems from is focused on primary and secondary formal education. Therefore, the only documents considered in the study and the paper are the ones addressing these levels of education. Based on this analysis, the paper concludes on what can be understood as quality of education. The paper does not intend to present a conclusive definition of education quality but rather systematize the implicit meanings it has presented in policies throughout time and, with this conceptualization, support the understanding and interpretation of educational policies in different national contexts.

While it does not present a ‘typical’ analysis of policies or critical policy analysis, the paper provides a systematization, categorization, and interpretation of the European political discourse on education, presenting an understanding of this topic that, while not indisputable, can help to conceptualize ‘quality of education’ and what it can mean for educational processes, from a broader perspective.

2 About educational policies

Policies convey a specific view of the world, corresponding to the ideology, interests, and perspectives of those behind its production (Apple, 2019). This view then translates into premises and orientations in the political texts aiming to influence the aspects addressed in them, changing processes, contexts, and realities (Ball, 1990). In this sense, policies are an instrument to create a particular social organization. For instance, in Portugal, during the dictatorship, education was an underdeveloped area, only teaching essential reading, writing, and math so that people could function in society, but not so much that they became critical thinkers, as the primary goal was to format people into an ideology and indoctrinate them into social morals and values, thus unable to criticize and oppose the regime (Nóvoa, 1992).

The policy text itself results from a process of negotiation and dispute between different voices and sources of power that struggle to see their view of the topic in question translated into the policy (Bowe et al., 1992; Mainardes, 2006). This dispute results in either one party being the victor or reaching a consensus in which all parties agree on the text. Additionally, in the current social organization, other voices influence policy-making, either implicitly or explicitly (Heimans, 2012; Olmedo and Ball, 2015). For instance, the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) has become a prominent source of influence in education and the implementation of high-stakes evaluation regarding students’ learning, mainly through the PISA test. PISA, and other similar programs, have encouraged comparison and completion among nations by presenting a ranking and setting standards. The presence of civil society’s agencies in policy-making is part of a new, although not so recent, form of political governance (Olmedo and Ball, 2015), emerging from the liberal and new-liberal orientations, in which the role of the State has been redefined has more of a regulator than an active agent. Thus, policy-making is a negotiation process between different actors with power of influence. This dynamic is particularly evident in Europe.

The European project seeks to establish this world region and this group of countries as a social, economic, and political power (Lawn, 2006; Ozga, 2012), by creating a sense of belonging and a common identity to which all nations adhere and contribute to, while also respecting the individual identity and sovereignty of each nation. In this dynamic, European agencies are set as collaborators and providers of help and resources for nations to thrive. This does not mean European orientations, recommendations, and positions do not influence national policies and processes (Dale, 2008; Lawn, 2019; Ozga, 2020a). On the contrary, they embody what Castells (2000) calls the “network society.” Moreover, governance in Europe is currently under the Open Method of Coordination model, in which the establishment of goals, frameworks, and standards to be achieved through cooperation and benchmarking allows for a direct influence and an external steering of national contexts (Lange and Alexiadou, 2007; Dale, 2008; Villalba, 2015; Lawn, 2019).

In education, this project led to the establishment of a European educational space, stemming from the acknowledgment of education as a pillar of societies and essential for European nations’ development and growth, aiming to help “European Union Member States work together to build more resilient and inclusive education and training systems.” In this regard, the role of the European Union (EU), and consequently of the remaining agencies, such as the European Commission as the main legislative body of the European Council, is to “contribute to the development of quality education by encouraging cooperation between Member States and, if necessary, by supporting and supplementing their action, while fully respecting the responsibility of the Member States for the content of teaching and the organization of education systems and their cultural and linguistic diversity” (Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Part III, TITLE XII, Article 165 (former Article 149), consolidated version). Nevertheless, as argued by authors such as Dale (2008), Lawn (2019), and others, the choice for an undefined and imprecise objective, such as “quality,” enables a greater level of influence and steering from the EU to nations. The search for higher quality led to the definition of standards and indicators for education, agreed upon by all Member-States, and to be reached in a timeframe. However, as many authors also point out, quality is never objectively defined, only its so-called components, which can change throughout time and in consonance with the perspectives of those in power or those with an influencing voice in policy-making – as argued above. Moreover, the search for quality and the setting of standards led to recommendations toward quality assurance and accountability to verify and encourage the reaching of such targets, which is in itself a form of regulation and steering of the education developed in each country (Olmedo and Ball, 2015; Villalba, 2015), and creating a phenomenon of political influence and convergence (Ball, 2001; Robertson and Roger, 2001; Nóvoa and Lawn, 2002; Dale, 2004; Steiner-Khamsi, 2004; Robertson, 2009). It is, then, possible to affirm that European law, while not binding, by conveying a vision of education, promotes a certain uniformity and “… changes the way that education is organized and delivered but also changes the meaning of education and what it means to be educated and what it means to learn…” (Ball, 1998: 128), thus shaping national contexts to the image of the European Educational Space (Dale, 2008).

It is, thus, ever more critical to explore what education quality is in the European recommendations and orientations and what they bring forward as orientations for education, particularly in the search for high-quality education (Heimans, 2012; Apple, 2019) to understand better and interpret the national policies and processes they trigger.

3 About quality in education

Education is the cornerstone of the individual and society’s growth and development. It is a fundamental human right, foreseen and established in the United Nations (1948) and the United Nations (1989). Both documents defend that education must be made accessible to all, ensure the acquisition of knowledge and skills, and promote the integral development of each person.

Freire (1967) defended education as a process of emancipation, allowing transformation, growth, and development in each individual and society. Dewey (1916) sees education as a democratic process in that it is “for all” and in which all, including children and students, have the right to participate actively in all stages of the process. In modern societies, though, education gained many responsibilities beyond its primary scope. While still being devoted to schooling, the transmission of knowledge, teaching children and young people curricular contents, and promoting spaces and opportunities for the development of the self, the forming of personality, and the acquisition of values, school education responsibilities evolved and integrated a much more socially driven orientation (Bernstein, 2000; Charlot, 2013). This orientation assigns school education a role in preparing future active, proactive, and productive citizens and professionals who contribute to society’s development, growth, and stability. It is through education that children and young people acquire basic disciplinary and curricular knowledge, such as the one Young (2008, 2010) calls “powerful knowledge” as it is considered the basic knowledge everyone should learn and is integrated into school curricula, being only accessible through schooling, particularly since education became accessible to all within the framework of democratic education (Dewey, 1916). However, it is also in schools that students acquire or deepen their socialization with social norms and functioning and can develop skills and competencies for a successful integration into social life (Charlot, 2013).

Education is, thus, political in the sense that it can not be neutral and immune to the social, cultural, and political setting in which it is defined and occurs, embodying the ideology, intentions, objectives, and rationale of those in the decision-making positions, that define the curricula, the design the legislation regulating educational systems, therefore being an instrument for social cohesion and steering; likewise, education in political in the sense that the society is not immune to education that, as an instrument of power, can shape the contexts and people through by teaching the intended values and norms that form the identity of the society education responds to Freire (1975) and Charlot (2013).

Fundamental to achieving these aims is how the educational and schooling process is organized, particularly concerning the pedagogical practices – teaching, learning, and assessment – and school management to create safe, challenging, supportive, and successful learning environments and experiences. Curriculum design and development are foundational in this process. An education that is inclusive, meaningful, and promotes effective learning and the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and competencies cannot rest on a “one size fits all” model. On the contrary, it needs to be as diverse as the student population, resorting to different approaches to adapt and develop the curriculum in a meaningful way, such as curriculum contextualization (Bernstein, 2000; Apple and Beane, 2007; Fernandes et al., 2013; Leite et al., 2018), and assessment practices that are not just about measuring the ranking students, but assume a role as promoters of learning, such as formative evaluation (Fernandes, 2006). Teachers are essential in this regard, as they remain the main actors responsible for curriculum development. The literature argues for their autonomy and agency, that is, their role as co-constructors and co-authors of the curriculum and the teaching and learning process, as well as their preparedness to act more than to execute (Leite and Fernandes, 2010; Priestley, 2011, 2012; Mouraz et al., 2013; Priestley et al., 2013; Biesta et al., 2015). This is only possible in an educational environment that promotes and values such practices, to which leadership is essential. Many studies highlight the influence that school leaders have in the school environment, in professionals’ motivations and performance, and even on students’ achievement (Fullan and Hargreaves, 1998; Priestley, 2011; Carrington et al., 2021; Chen-Levi et al., 2024).

Education has, thus, been an increasingly important part of societies, and its quality has become a topic of debate and concern, leading to continuous initiatives toward improving, promoting, or studying it. Nonetheless, defining quality is no easy task. The concept of quality is somewhat subjective. As Doherty (2008) argues, it ranges from “Fitness for purpose… [which] requires defining the purpose and setting criteria by which a judgment can be made” (pp. 256) or “Excellence,” a “… concept [that] is just as subjective as “quality”” (pp. 256). In other words, quality can have different meanings and refer to various aspects. In the same line of thought, many authors are adamant in stating the polysemic and complex nature of quality, arguing that its interpretation and definition are dependent on the geographical, political, and sociocultural context where it is discussed (Ishihara-Brito, 2013; Lee and Zuilkowski, 2017; Moreno, 2017; Joshi, 2018; Egido, 2019; Zheng, 2020). For instance, education quality is often perceived in a market-oriented and product-oriented, being associated with the results achieved by students, assuming that the higher the scores, the higher the quality of the educational process, or with education’s contribution to the labor market and social progress (Lee and Zuilkowski, 2017; Moreno, 2017; Joshi, 2018). At the opposite end are the perceptions of education quality as providing the necessary conditions for students to reach their full potential, including mastering curricular and disciplinary knowledge, and a range of transversal and soft skills that allow them to be active and responsible citizens. This requires ensuring the necessary conditions for a successful schooling path, such as well-prepared, motivated, and valued teachers, resources of diverse nature, access to education, support, differentiated pedagogical practices and learning opportunities, up-to-date and diverse educational offer and curricula, good school leadership and management, among others (Moreno, 2017; Joshi, 2018; Egido, 2019; Zheng, 2020). Some authors stress the need to consider both understandings of quality in a more comprehensive approach (Lee and Zuilkowski, 2017; Moreno, 2017; Zheng, 2020). Kumar and Sarangapani (2004), in their work, traced the understanding of the quality of education throughout time by analyzing different conceptions of what education is for and what it should be. The authors give an account of education as an instrument of social mobility and social equity, of control, as a multifaceted process demanding diverse pedagogical approaches, as an object of interest to politicians, scholars, and the overall population, and as a service provided in a market-oriented perspective. With this timeline, the authors reached six lessons regarding education quality that briefly summarize as quality search and debate being essential to analyze the state of things and make necessary advancements; that it is essential to continue to discuss the aims of education from a philosophical perspective; that quality and equity are closely linked; that the rise of accountability impacted on how education is seen and developed (Kumar and Sarangapani, 2004). Likewise, Hopkins et al. (2014) trace the evolution of school improvement efforts and theories, having identified five phases, among which are the attention paid to schools as able to improve and as living organisms; the consideration of aspects such as teachers’ work; efforts concerning the dissemination of knowledge to inform and base reforms and improvements. Also related is the intention to identify and promote “what works” in education and what should be done to achieve excellence and top results. This is the aim of Educational Effectiveness Research (EER), a research approach aimed at exploring and trying to understand what can explain the differences in school success at different schools and which factors promoted such success, what contributes to students’ success, focusing mainly on the school institution and related aspects such as school environment and culture, teachers’ practices, and school resources, and separating it from other factors such as students’ characteristics, among others. With this, EER expects to develop a theoretical framework to support educational practices, thus fostering success where it is not yet achieved (Reynolds et al., 2014; Creemers and Kyriakides, 2015a, 2015b). By researching these factors, EER produces knowledge that can help educational institutions, such as schools and central administration agencies, and professionals, from politicians to teachers, to work more effectively in their specific contexts, thus reaching higher levels of quality (Reynolds et al., 2014; Creemers and Kyriakides, 2015a, 2015b). Other authors have alerted to a movement where the quality of education is synonymous with its products, academic results, and overall quantitative achievements, particularly in the context of large-scale assessments such as the PISA program, and country comparisons regarding measurable aspects of education (Biesta, 2009; Grek, 2009; Grek et al., 2009; Figueiredo et al., 2017).

Furthermore, despite the uncertainty as to what quality education is, the centrality school education gained in modern societies resulted in initiatives aiming to ensure it and in the emergence of policies dedicated to encouraging and implementing quality assurance processes from a mega-level (supranational) perspective to a micro level (institutional level). These are aimed at assessing and promoting the quality of education and have commonly taken the form of evaluation of educational institutions – schools –, educational outcomes – students’ results –, educational professionals – teachers –, or a combined version of all. The arguments behind such processes stem from changes in educational governance, particularly the rise of New Public Management trends, which transferred to education a managerial rationale, resting on principles of competitiveness and market (demand-offer nexus and productivity), translated in concerns with (or even so, more important) training and preparing students with knowledge and skills to respond to labor-market and society’s needs and demands, while also achieving high levels of academic success and reaching predetermined and present standards, developing future workers and active citizens (Grek et al., 2009; Figueiredo et al., 2018). The New Public Management also resulted in different roles assumed by the State and the local institutions, which in the case of education meant the transfer of powers from the State to schools, with more autonomy given to the latter accompanied by accountability requirements. In this framework, schools are given more decision-making power, especially in resource management and, at a smaller level, in curriculum management. The State is no longer responsible for what happens but still acts as a supervisory body and a regulator, and schools are now being increasingly held responsible for their performance (Afonso, 2013; Ozga, 2020b). At the same time, within this scenario arises the perception that the more information is available about education and schools’ performance to inform management, the better the decisions made are (Aderet-German and Ben-Peretz, 2020), assigning quality assurance (QA) processes with an empowerment feature, as they produce information that can help identify aspects in need of change and improvement and possible routes for action (Figueiredo et al., 2018). This argument is based on research lines such as the above-referred Educational Effectiveness Research (EER) and data-driven decision-making (DDDM) (Aderet-German and Ben-Peretz, 2020).

Some significant examples of QA implementation are found in Ireland, England, Scotland, Netherlands, and Portugal, where the evaluation of schools is already a tradition and is linked to educational quality assessment and promotion. Despite being geographically and culturally different, these countries share common traits in their quality assurance mechanisms. As a result, QA processes are developed within a duality between emancipation and regulation, meaning that all aim for the improvement of education while at the same time relying on these mechanisms for accountability purposes (Ehren and Swanborn, 2012; Ehren and Visscher, 2008; Figueiredo et al., 2018). Interestingly, despite the several references made to quality in the guiding documents used in these processes, again, the concept is never fully defined.

4 Methods

The study presented in this paper is part of a larger research project that aims to map the effects of external evaluations on educational quality, focusing on primary and secondary education schools. In line with the project’s goals, this study aimed to understand and systematize how ‘quality’ in education has been presented and conceived in European political documents by exploring either the specific definitions, when existent, or the aspects associated with quality in the considerations made in European recommendations and reports. Accordingly, the methodology followed a qualitative interpretative orientation using the content analysis technique (Julien, 2008; Bardin, 2011) as it allows the identification of patterns in discourse, the interpretation of large blocks of discourse in a cross-analysis, and the inference of meanings, either explicit or implicit (Julien, 2008; Bardin, 2011). This approach differs from a classic policy analysis as it does not intend to identify one single “truth,” the one intention and meaning expressed in the text, nor dissect the political text to identify its context of origin and its contradictions and incoherences (Codd, 1988). On the contrary, the analysis intended to understand the different meanings and aspects attributed to quality in education in documents referring to it, aiming to create an understanding concerning a plural concept such as “quality.”

The analysis corpus consisted of documents identified in the online repository of European Law (EUR-Lex), using ‘quality education’ as a keyword and without restricting any of the available filters (year of publication, collection, type of act, author, and type of procedure). The keywords combining ‘quality’ in the first search field and ‘education’ in the second search field ensured a more focused search, given that the EUR-Lex platform contains documents from diverse areas and topics. The choice for this combined keyword resulted from a brief process of experimentation in the EUR-Lex platform with different search options, such as ‘educational quality’ and ‘quality of education’, and using filters regarding the documents’ authors and the theme. This experimentation revealed that the search engine would not fully restrict the documents found, as it would present documents addressing subjects beyond education. The expression ‘quality education’ was the most targeted one, resulting in a more focused search while also presenting some documents outside the scope of the study, but nonetheless, in a smaller number. For this reason, the keyword used in the search was only ‘quality education’, and no other filters were used. Likewise, the option for not restricting the time period of search relied on the intention to access all documents that address quality in general primary and secondary education throughout time, which could provide a perspective of the evolution of socio-historical change in the understanding of ‘quality’. Although no filters were used in the database, some documents were excluded, such as the ones concerning higher education, adult/lifelong education, vocational education, and other targeting specific levels or modalities of education, working staff documents, proposals, or other non-consolidated documents. These exclusion criteria allowed the identification of documents oriented explicitly to the educational level studied and for the official and published discourse. The search considered official documents from different European agencies, such as the European Union, the European Council, the European Commission, the Council of the European Union, and the European Parliament, due to their roles in proposing and producing legislation, decision-making, and enacting policies and decisions. Therefore, these agencies’ official discourse plays a central part in defining educational priorities in Europe and expresses the orientation and interests steering educational actions. Reports from Eurydice were also considered, as it is the branch of European agencies responsible for studying education.

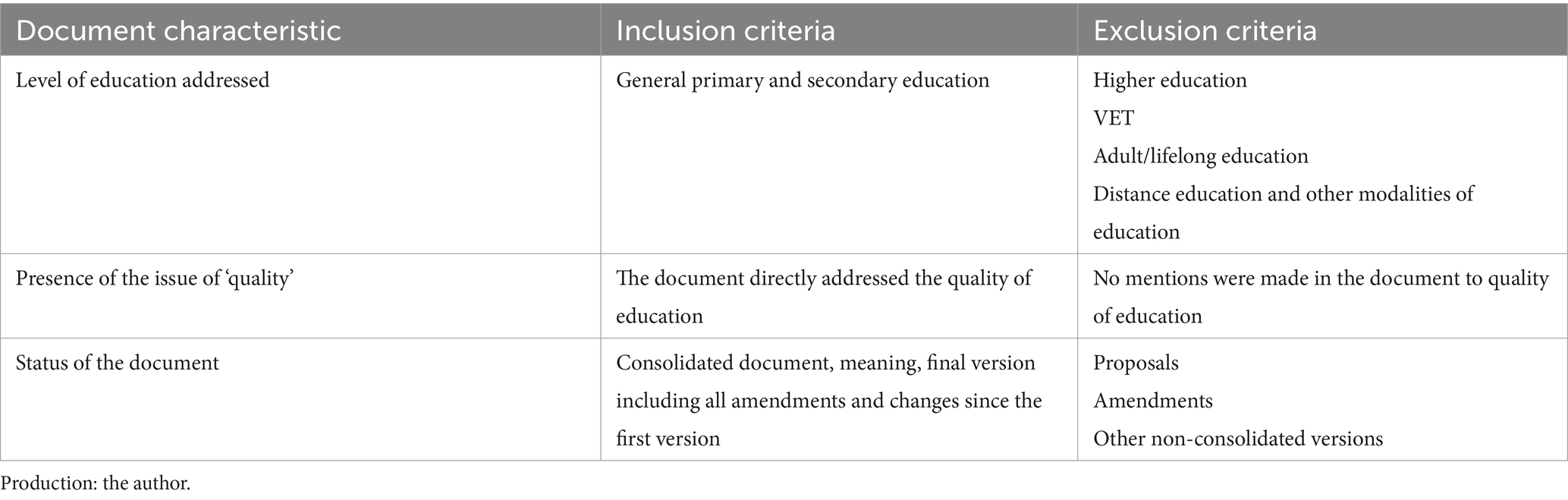

A total of 40 documents were collected, selected by the titles, and subjected to a screening read. With this process, the intention was to assess whether the documents addressed ‘quality of education’ or developed around different aspects. The screening read revealed that 21 documents focused on school education but did not address the issue of quality. Despite acknowledging the relevance of several of those documents to discuss education, educational improvement, and educational goals, since ‘quality’ was absent from them, these 21 documents were discarded. Table 1 shows all inclusion and exclusion criteria used for document selection.

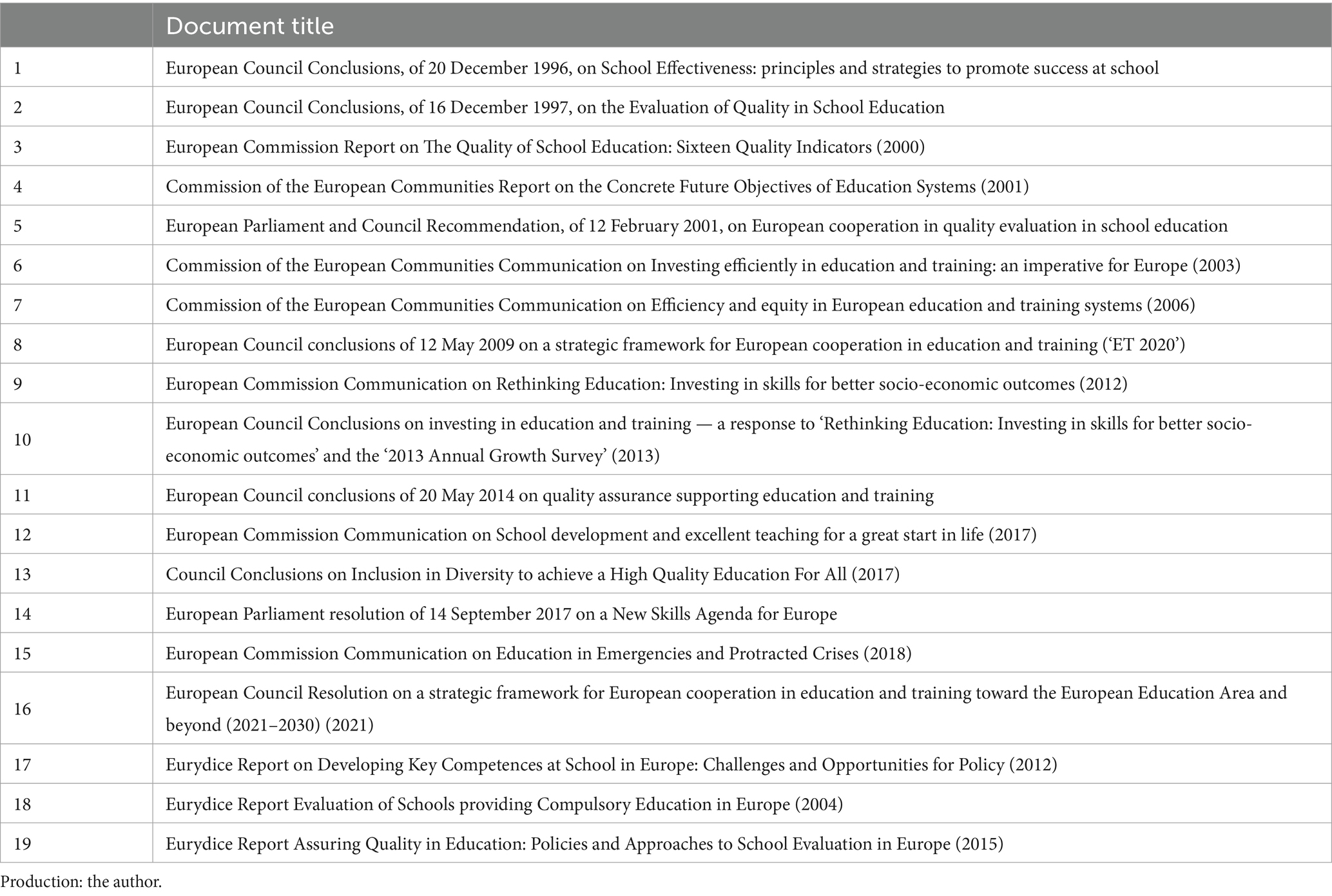

The screening read resulted in the selection of 19 documents that addressed ‘quality of education’, either by relating it to education planning and development or quality assurance, as identified in Table 2.

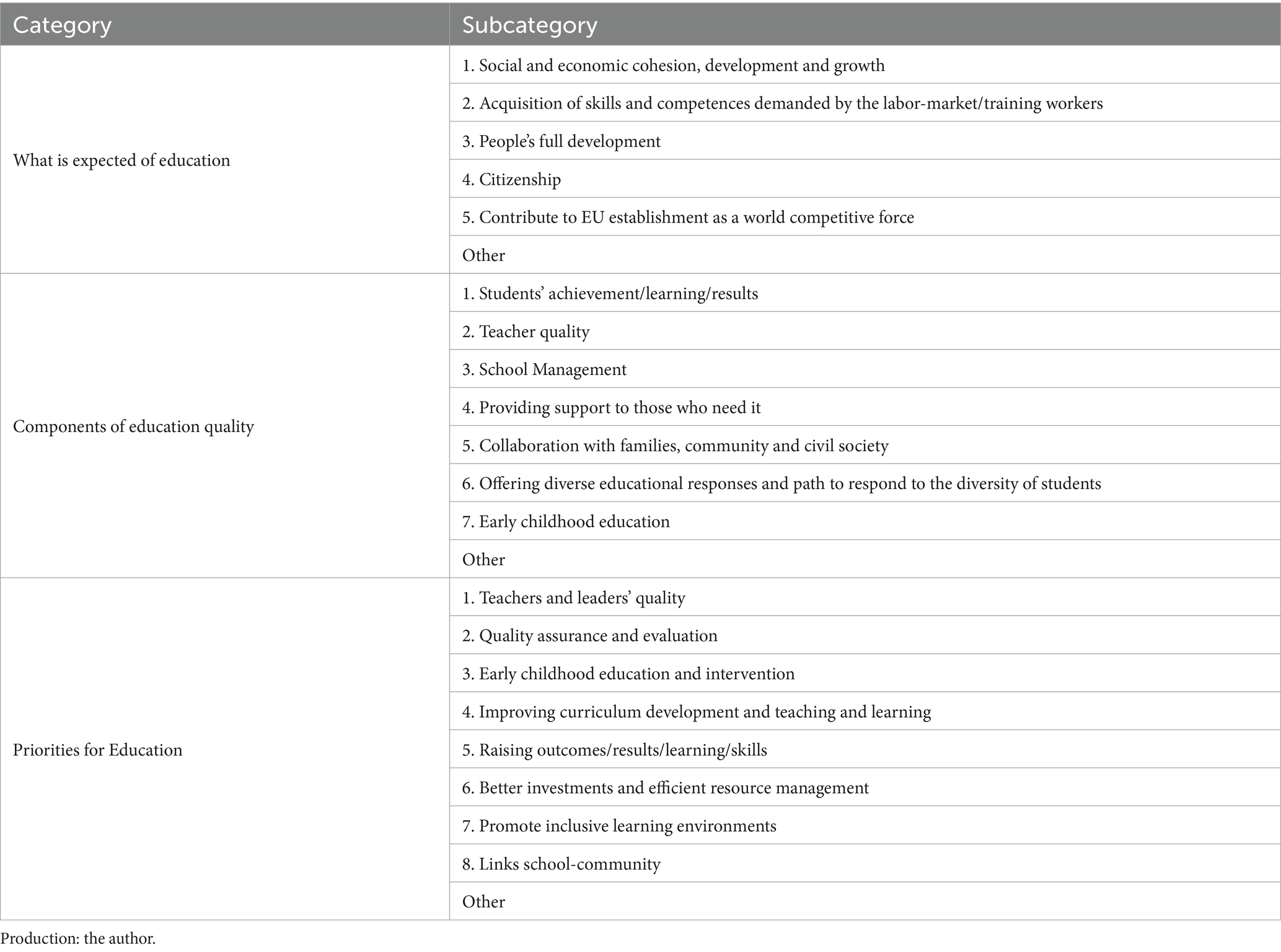

The 19 documents were subjected to thematic content analysis to identify discursive trends organized into categories. The analysis process consisted of a series of steps to deeply explore, organize, and interpret the information in the documents. The first step consisted of a deep reading of each document to identify the main themes/topics addressed, which later constituted the categories of analysis. These were all emergent categories induced by the documents’ content (Amado et al., 2017; Bardin, 2011). The second step consisted of coding the information into the corresponding category. The coding comprises units of sense, e.g., sentences, paragraphs, words, or ideas expressed about a particular aspect related to the category (Bardin, 2011). To ensure rigor and thoroughness in the analysis and organization of information, the categories established were mutually exclusive, meaning that each unit of sense could only be allocated into one category. In the third, fourth, and fifth steps, the coding was revisited to eliminate duplications and contradictions, merge or divide the categories into subcategories whenever necessary, and ensure that each unit of sense was allocated into the proper category/subcategory. The final category structure can be seen in Table 3.

As only one researcher, the author, developed this study, it was not possible to conduct an inter-coder reliability check (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020). However, to ensure reliability, the coding process was reviewed three times (steps 3, 4, and 5) to confirm the coding results. This allowed for a more profound level of analysis and a reliable iterative and interpretative process. The following sections and subsections explore the results of the analysis.

5 Education quality in European policies: expectations and priorities for education

A first consideration to make is that no specific definition of ‘quality’ was found in the 19 documents analyzed. Furthermore, the polysemy associated with the concept of education quality identified in the scientific literature is confirmed by the European documents analyzed. Nonetheless, one can infer what quality has meant throughout the years by analyzing and interpreting the considerations and guidance provided for education when its quality is on the line. From the analysis, three main themes of discourse associated with mentions of educational quality emerged: (i) ‘What is expected of education’, which addresses the expectations regarding the education of quality, what it should consist of and should achieve; (ii) ‘Components of education quality’, regarding the aspects listed of referred to when exploring concerns with the education of quality; (iii) ‘Priorities for Education’, regarding the priority aspects of education that need to be addressed and invested in, in order to ensure its quality. The cross-analysis of these aspects allows for the interpretation of what quality in education means, thus helping to conceptualize it. This section explores each of these themes individually.

5.1 ‘What is expected of education’

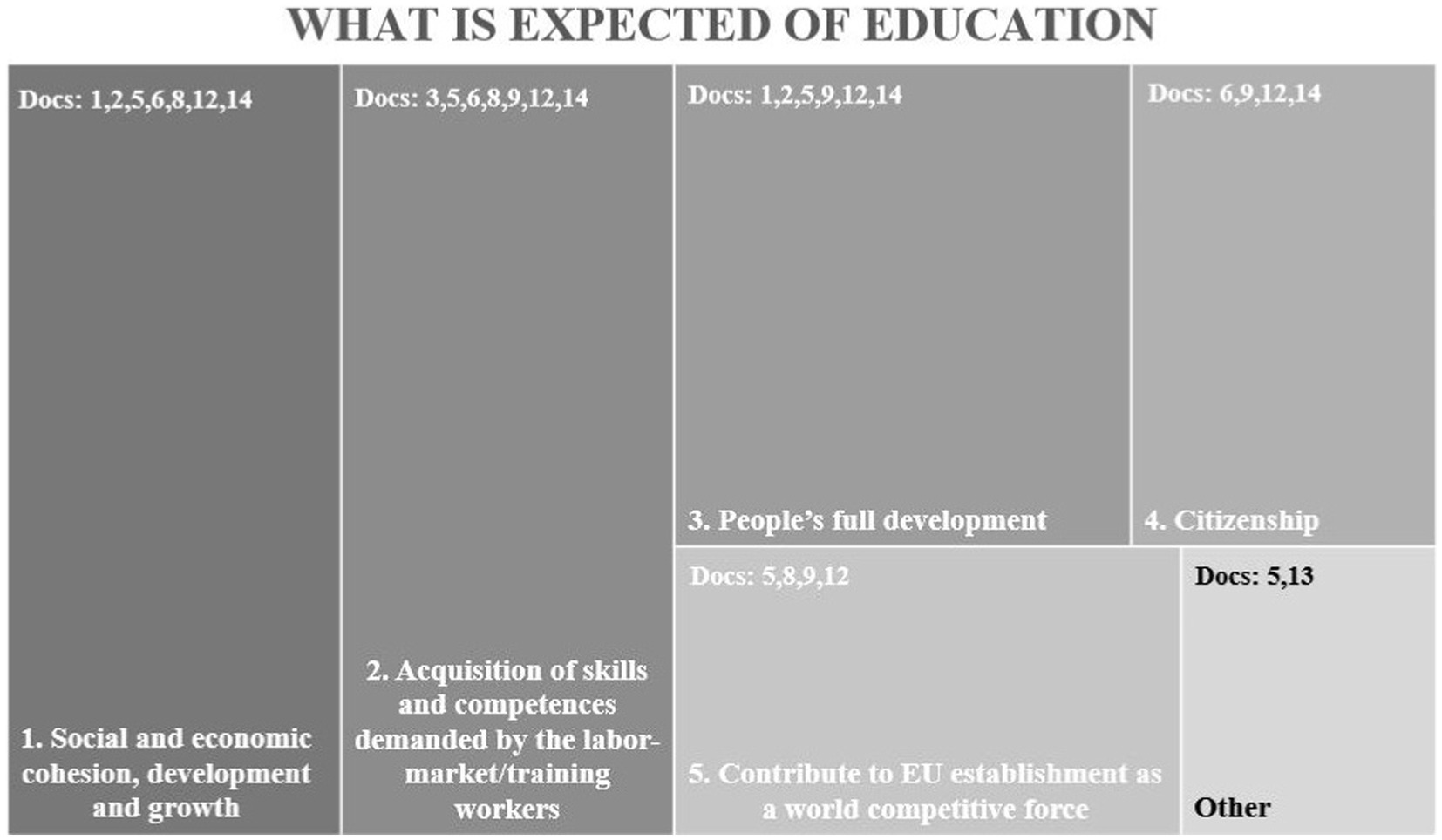

A first dimension that emerged in the analysis is the frequency with which the documents make considerations on the role education plays in society and the individual, setting the tone as to what education is, regardless of the specific characteristics of Member States, is supposed to pursue and achieve. In this regard, five key aspects are mentioned in 10 of the 19 documents, as illustrated in Figure 1: (1) Social and economic cohesion, development, and growth; (2) Acquisition of skills and competencies demanded by the labor-market/training workers; (3) People’s full development; (4) Citizenship; (5) Contribute to the establishment of the EU as a competitive world force.

The first aspect, 1. Social and economic cohesion, development, and growth, is present in the majority of documents considered in this category (docs 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 14), based on the assumption that education, by fostering learning on different aspects, and training students for an active role in society as workers and citizens, creates conditions for them to contribute to social development and growth actively. An example of this is found in the 14. European Parliament resolution of 14 September 2017 on a new skills agenda for Europe, which “Stresses, as stated by the OECD, that more educated people contribute to more democratic societies and sustainable economies” (point 34).

Another highly mentioned aspect in the documents is education’s role in fostering the 2. Acquisition of skills and competencies demanded by the labor-market/training workers, present in several documents (documents 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12, 14). It is argued that one of the primary goals of education and its functions is to prepare students to enter the labor-market, promoting the conditions for acquiring knowledge, skills, and competencies necessary for and demanded by enterprises, businesses, and other employment options.

Regarding 3. People’s full development (documents 1, 2, 5, 9, 12, 14), the documents state that education is a process through which children and young people can fulfill their full potential and achieve personal growth.

In what concerns to 4. Citizenship (documents 6, 9, 12, 14), it is stated that one of the goals of education systems and institutions is to promote children and young people’s development of knowledge and values for active citizenship.

Finally, the documents also state education’s role to 5. Contribute to EU establishment as a world competitive force (documents 5, 8, 9, 12). This can only be achieved by first achieving the previous aspect, particularly those related to social and economic growth and the training of workers, which can directly contribute to creating a ‘European dimension in education’.

Other less expressive mentions are made of the role of education in fostering inclusion and digital competencies, both emerging from the rapid pace at which the world develops and from the increasing challenges related to social, economic, and political crises (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of the five key aspects of ‘What is expected of education’. Production: the author.

Finally, looking at the documents throughout the years, it becomes clear three aspects are recurrent and have remained stable since the late 1990s and the recent years: education’s role in promoting social and economic cohesion, development and growth, in ensuring the acquisition of skills and competences and training workers for the labor market, and, although less expressively, promoting people’s full development. Less present in the documents is the relationship with preparing students to be active and responsible citizens, a concern present mostly in the second half of years 2010. Likewise, although the European project seems to be a priority, education’s role in achieving it is rarely directly addressed in ‘What is expected of education’.

5.2 ‘Components of education quality’

As stated before, very few definitions of education were found in the analysis of the documents. However, several mentions are made in the documents of aspects that compose what is considered an education of quality. This category systematizes those components of education quality, which can then be used to understand what is understood as quality in the documents influencing political decisions in Member-States.

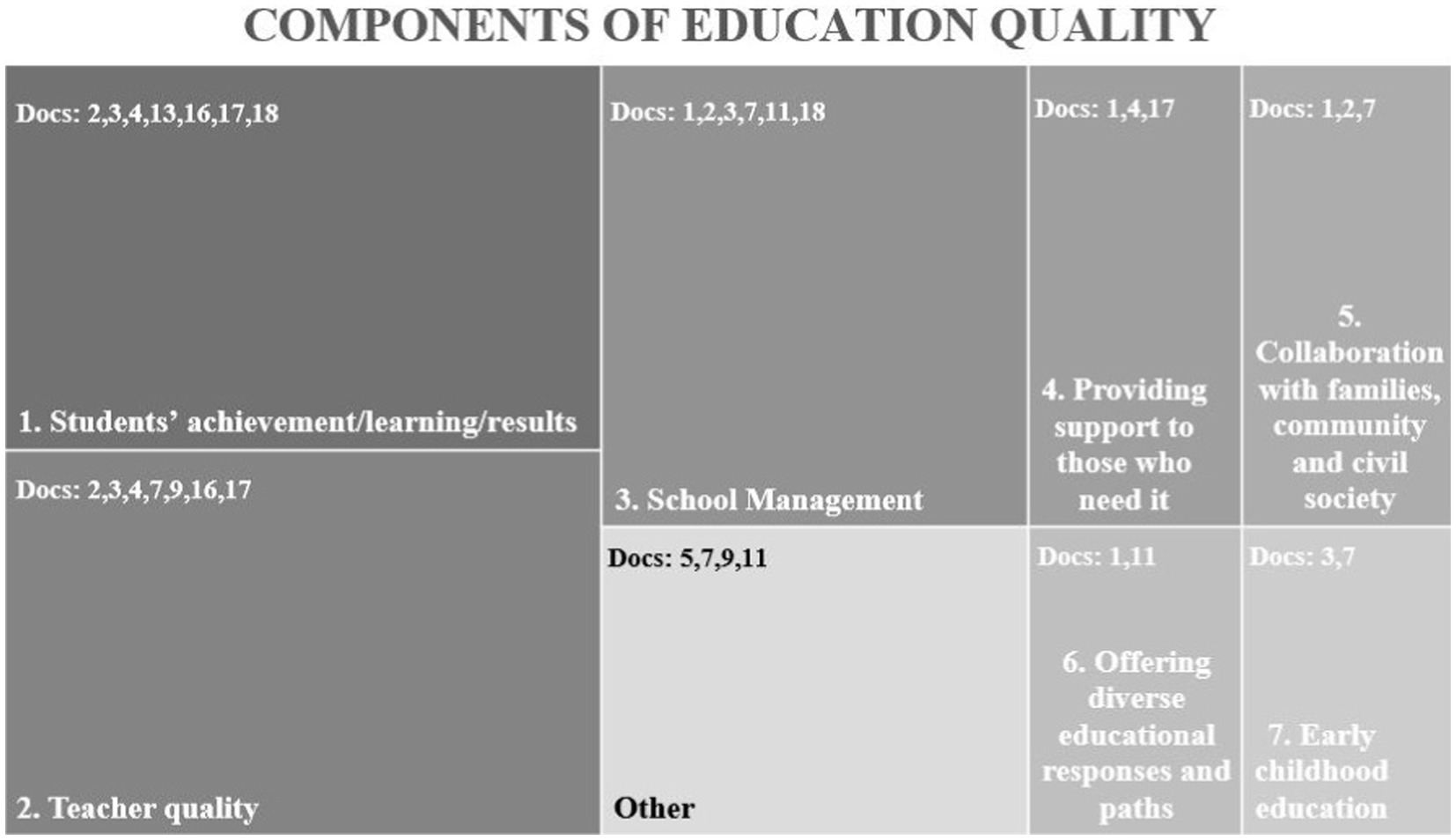

These components can be grouped into seven types:

An obvious component of education quality, present in several documents, relates to 1. Students’ achievement/learning/results (documents 2, 3, 4, 13, 16, 17, 18). This component includes the students’ acquisition of essential knowledge and skills, such as literacy, numeracy, knowledge of sciences, digital competencies, and transversal skills. It also includes the completion rate and attainment or conclusion of education levels.

Related to the previous one, as stated in several documents, is 2. Teacher quality (documents 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 16, 17). The documents state that the quality of the teaching staff and how they develop the teaching and learning process is fundamental to students’ success in school and to the quality of the process. Included in teachers’ quality are concerns with the recruitment processes, the working conditions offered, such as pay and support, and the quality of teacher training.

3. School Management is another component considered in the documents’ references to education quality (documents 1, 2, 3, 7, 11, 18). Within school management are aspects related to school leaders’ quality: their training and preparation, how they engage and motivate school staff, and their decision-making processes. This component also includes the efficient use of investments made and resources attributed to education in a manner that ensures the offering of better learning opportunities and equity. Also relevant to this component are monitoring and evaluation processes as tools to ensure and promote the quality of the educational process at all times and in all it implies.

4. Providing support to those who need it (documents 1, 4, 17), or in other words, being aware of the diversity of students and their very different needs, and working to ensure all children and young people receive the necessary support to attain and complete schooling with success. This, in turn, means ensuring the quality of the necessary physical (infrastructure) and material conditions (books, digital equipment, and others) and, if necessary, early intervention to help cope with difficulties. Also included in this component is ensuring that all, regardless of gender, culture, nationality, religion, and needs, have access to an effectively inclusive education.

5. The Collaboration with families, community, and civil society is also highlighted in the documents (documents 1, 2, 7) based on the assumption that schools thrive from establishing partnerships and involving different educational actors, as they can contribute to designing and promoting better and more diverse learning opportunities and experiences, which are more likely to meet the diversity of students.

Related to the previous component is the 6. Offering diverse educational responses and paths to respond to the diversity of students (documents 1, 11), meaning that education of quality rejects a “one size fits all” approach and multiplies the possibilities for students’ schooling paths as a means to better respond to the diversity of needs, characteristics, and interests, thus fostering their success.

The existence of 7. Early childhood education systems is also referred to (documents 3, 7), as it is understood that these systems are essential in promoting an inclusive educational system, tackling inequality and difficulties, and creating the basis for a successful educational path.

Figure 2 summarizes the distribution of mentions to each component among the documents analyzed.

Figure 2. Distribution of the ‘Components of education quality’. Production: the author, to the end of section 5.2 ‘Components of education quality’.

Repeating the exercise of looking back over the years, it is possible to understand that three components are present in a significant number of documents over the years: student achievements/results, teacher quality, and school management. Other more qualitative and humanistic aspects, such as providing support, school engagement with families and the community, diversity of educational paths and options, and early childhood education offer, seem to become absent from the political discourse. Although it is not possible to effectively conclude on the matter, it seems that these components have been relegated to a secondary, or even inexistent, place in most recent years, contradicting the roles attributed to education as found in What is expected of education’, like promoting people’s full development which includes such components. This could signify a turn to a market-oriented approach to education quality. This acknowledgment is particularly alarming considering the current political trend in many countries of the rise of right-wing parties, particularly extremist ones.

5.3 ‘Priorities for education’

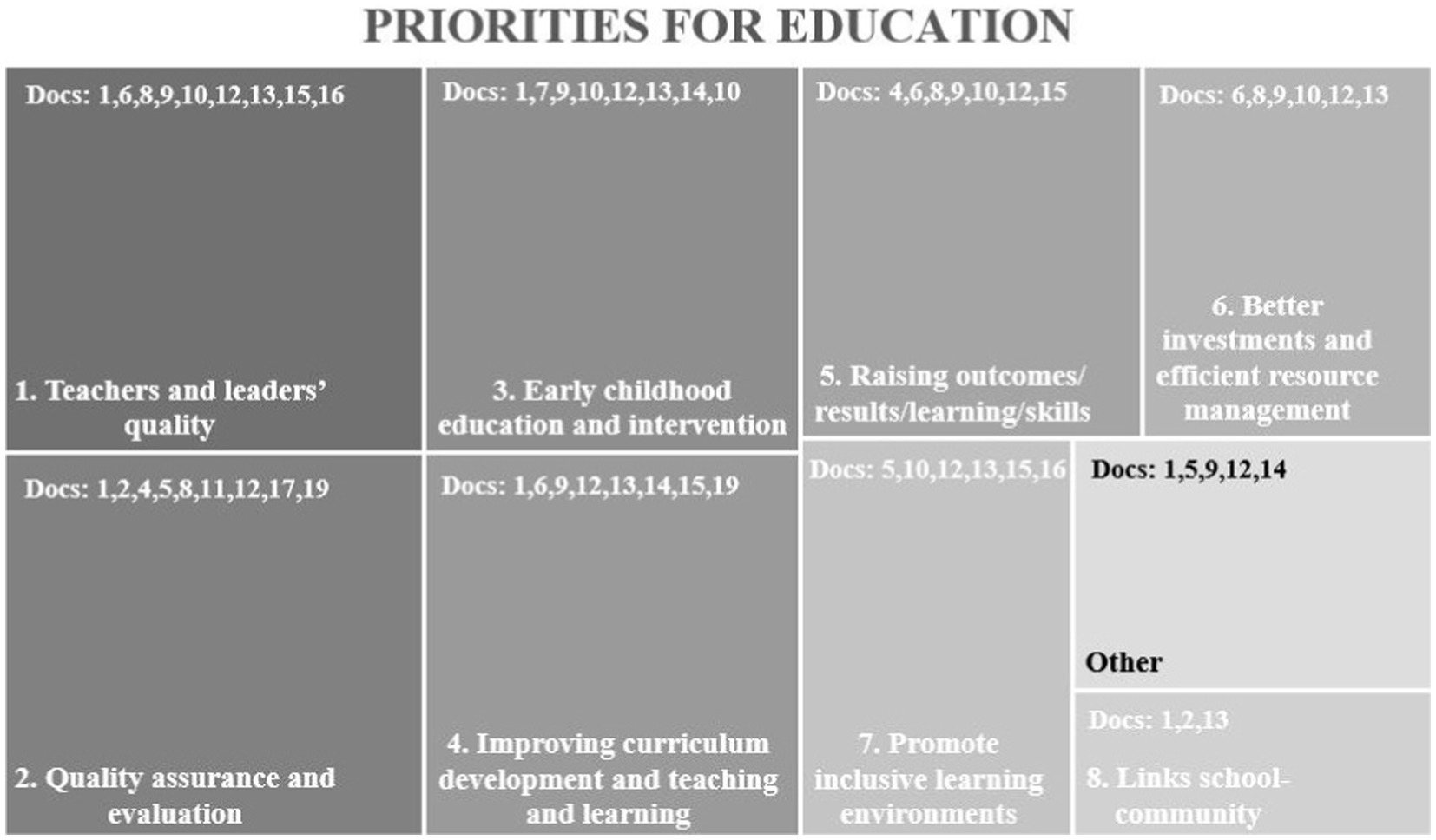

Another category found regards priorities established or recommended to be adopted in the documents, which, as expected, are aligned with the roles and functions attributed to education and the components of education quality. Eight (8) priorities were identified in the analysis, as explored below and represented:

1. Teachers and leaders’ quality is the most frequent aspect referred to in the documents as a priority Member States should invest in, particularly regarding teachers (documents 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16). The underlying assumption is that, as stated in the previous section, teachers are essential to the quality of the learning environment and experiences. Nonetheless, the challenges currently faced by teachers and the profession’s current state are acknowledged. As such, several documents stress the need to invest in recruiting the best teachers and in their initial and in-service/continuous training. Furthermore, emphasis is placed on providing conditions to motivate and attract teachers, such as pay, support, and status improvements, among others. Regarding leaders, priorities must be set for recruiting leaders with the best profiles and training.

As these documents develop around improving education and encouraging change for education to meet specific goals, several documents refer to the need to invest in 2. Quality assurance and evaluation (documents 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12, 17, 19). These processes are understood as critical tools for nations, educational systems, and educational institutions to judge the quality of the service provided, being accountable regarding their increasing levels of autonomy and for resource management while also producing knowledge, identifying good practices, and areas in need of improvement. With all this, quality assurance and evaluation mechanisms are essential to informed decision-making at different levels of educational governance.

Also highly mentioned is the need to invest in establishing and improving 3. Early childhood education and intervention (documents 1, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 16), understood as the basis of the educational process and the first line of intervention toward fighting inequality and supporting children with needs or in a disadvantageous position.

Another relevant priority is set on 4. Improving curriculum development and teaching and learning (documents 1, 6, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19). This includes several measures to ensure that students’ learning experiences are rich, diversified, respectful of the diversity of students’ characteristics, and oriented toward ensuring the continuity of their development in higher levels of education and the labor market. Such measures include curricular contextualization – linking the curricula with real-life experiences – creating different offers and educational paths to meet all students, and investing in formative assessment practices.

As could be expected given the previous sections, one of the areas to invest in is 5. Raising outcomes/results/learning/skills (documents 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15). This includes implementing measures to foster learning basic skills – literacy, numeracy, science, ICT – and transversal skills- allowing students to develop as persons, citizens, and future workers. Also important is promoting the acquisition of skills for an active life in society.

6. Better investments and efficient resource management is also a priority referred to in several documents (documents 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13), as a focus on education and on implementing change requires investments in equal measure, oriented toward the priorities established, and managed efficiently to ensure the best input–output nexus.

Acknowledging the increasing diversity that inhabits schools, another priority is to 7. Promote inclusive learning environments (documents 5, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16) to ensure an effective education for all, regardless of social, cultural, religious, or personal characteristics, regardless of needs and difficulties.

Also, a priority is the establishment of 8. Links school-community (documents 1, 12, 13), seen as an asset in promoting better learning experiences and creating educational responses better suited to each student.

Other aspects focused on as necessary, while less frequent, are adopting a whole school approach and adapting educational systems to the fast-paced change in the world (documents 1, 5, 9, 12, 14) (Figure 3).

The look throughout the years regarding the ‘Priorities for Education’ is substantially different from that of the previous categories. It seems that most priorities are somewhat recurring in the political discourse, and, oddly, raising results is one of the least mentioned priorities in the documents. On the contrary, more humanistic aspects are mentioned, such as the quality of teachers, curriculum, and early childhood, which allude to education processes rather than education products.

6 Discussion

The polysemy associated with the concept of education quality identified in the scientific literature is confirmed by the European documents analyzed. Although, as previously stated, there was no clear definition of education quality, the analysis allowed the identification of a set of principles, goals, and orientations for education in the search for its quality that is intimately related to how we perceive education in the society, and the political ideologies and intentions of those in the decision-making and policy-production positions.

Regarding the first category, ‘What is expected of education’, the documents give a higher relevance, in the sense that it is the most referenced aspect, to education’s role in ensuring social cohesion, development, and growth, or, in other words, in education’s responsibility in helping society to develop and establish itself as a strong entity, of known importance and relevance, with a distinctive identity. Such role embodies what Bernstein (2000), Charlot (2013), and others, argue is the political role of education, that is, the capacity to shape realities into what is expected or desired. Likewise, the alignment in the documents’ discourse and the prevalence of these goals reveals the power of policies in establishing a specific view of the world (Ball, 1990; Apple, 2019).

Alongside is the function to promote the acquisition of skills and competencies, not so much in acquiring academic, disciplinary, and curricular knowledge as is the primary goal of schooling, but acquiring a set of necessary skills to be productive workers. This corresponds to a market-oriented conception of education, in which schools must align with businesses and the labor-market, tailoring their practices and approach to education to meet the needs of such a market an increasing and highly debated priority in education (Kumar and Sarangapani, 2004; Grek et al., 2009; Figueiredo et al., 2018). This aligns with the first aspect, as preparing these specialized and highly trained workers contributes to a sustainable, productive, and competitive society, as is sought by European agencies and the nations they represent. This is reinforced by the less expressive but still significant aim of contributing to establishing the European Union as a world competitive force. Again, education seems to be perceived as an instrument for creating and maintaining a particular social order, and to form(at) people for what society needs from them, to transmit a set of social norms, rules and values that are shared by the population thus creating a sense of shared identity (Bernstein, 2000; Charlot, 2013). Moreover, this aligns with the European goal to create a European identity in which the countries form a united front to establish Europe – the European Union – as an inter/supranational power (Lawn, 2006; Ozga, 2012, 2020a). Based on this, it is possible to infer that education is being increasingly, and regularly, conceived more in an instrumental way, serving a political purpose, being used as an instrument of power and social modeling rather than as a social process that seeks to foster people’s development, growth and the reaching of their full potential and citizenship, which literature still presents as the primary role of education (Dewey, 1916; Freire, 1967; Bernstein, 2000; Young, 2008, 2010; Ozga, 2012; Charlot, 2013), something that while still present in the documents, is less expressive than the three aspects above. Considering the judgment of something’s quality requires a comparison between what is expected and what is achieved, it could be argued that the quality of education will be closely related to it fulfilling these roles and to its contribution to the social and political goal, more than for its impact on people’s lives.

Concerning the second category, ‘Components of education quality’, it is possible to find aspects that, in some measure, contradict the deductions from the previous category, as these components are mainly focused on the processes and elements that compose educational processes rather than what is achieved. Students’ achievements and results are, undoubtedly, relevant in understanding and assessing the quality of education as, reasonably, every educational process aims to promote and ensure the educational success of students, and this could, in turn, resonate in the above-referred aspects such as the acquisition of skills and the training of future workers. Nonetheless, the majority of aspects found in the documents regarding the quality of education refer to elements integral to the process, with particular emphasis on teachers’ quality – preparedness, motivation, practices – and the conditions for their professional work – salaries, training, among others, as they are considered the driving forces behind schooling and the main responsible people for the development of meaningful and successful learning environments and experiences. Teachers are, indeed, fundamental actors in education, with their attitudes and posture highly influencing students’ learning and well-being in school and the classroom (Leite and Fernandes, 2010; Priestley, 2011, 2012; Mouraz et al., 2013; Priestley et al., 2013; Biesta et al., 2015). Also important, and somewhat related to teachers’ working conditions and to the quality of the learning environments, is school management, in the sense that this is the process that ensures the good functioning of schools, that provides the necessary conditions and resources, with school leaders playing a vital role in this regard as they are responsible for creating the conditions for high-quality education processes, for providing support for professionals, to manage resources effectively and efficiently, and to create healthy and successful organizational culture and environments (Fullan and Hargreaves, 1998; Priestley, 2011; Carrington et al., 2021; Chen-Levi et al., 2024;). Likewise, good management and good teachers are prerequisites for the following three aspects found – providing support to those who need it; collaboration with families, community, and civil society; offering diverse educational responses and paths to respond to the diversity of students – all of which regarding the creation of suitable conditions for the educational process, fostering students’ participation and engagement in education. Hence, what is found in these components of education quality is a conception of educational quality in a much more humanistic perspective when compared to the instrumentalist stance found in “what is expected of education,” more concerned with the characteristics of the process, the quality of the process, experiences, and conditions, and what is offered as an educational response. Identifying these components is significantly important to promote awareness in all those interested and invested in education (professionals, decision-makers, and other stakeholders) on the complexity of achieving educational quality and that all components are interrelated in a complex web of influence. Furthermore, it could help policy-makers and nations to effectively identify which components may need more substantial investment and intervention to improve, thus contributing to improving quality overall. This is the difference between adapting and adopting policies and measures, meaning a critical and conscientious consideration of European recommendations and guidelines, adapting them to each country’s specific characteristics and situations while still aiming for a common and higher goal.

The third category, ‘Priorities for Education’, accounts for aspects that are, as could be expected, closely aligned with the components identified in the previous category, with particular emphasis on investing in teachers and leaders, their recruitment, their working conditions, their training and preparedness for their roles, and their overall quality, which, as was already stated, are prerequisites to the creation of inclusive, diversified and meaningful learning experiences, opportunities and paths as these are essential to reach another priority that is improving outcomes. Also clearly expressed in the documents is the need to ensure better investments to make the previous priorities possible since, without proper investment, it becomes impossible to improve conditions. A note here for two priorities that seem to go beyond what was found in the previous categories: Early childhood education and intervention, only briefly mentioned as a component in two documents but significantly present in the priorities for education being mentioned in 8 documents, and Quality assurance and evaluation mechanisms present in 9 of the 18 documents analyzed, thus assuming a prominent position in the priorities for education. Regarding the latter, such relevance can be explained by the understanding of such processes as instruments to promote the desired quality, by assessing the fulfillment of the priorities set and allowing to compare what is achieved with what is expected, but also by creating the basis for improvement action whether at the State level or the school level (Aderet-German and Ben-Peretz, 2020; Ehren and Swanborn, 2012; Ehren and Visscher, 2008; Figueiredo et al., 2018). Furthermore, it is also important to explore the issue of quality assurance. As stated in section 3, About quality in Education, despite the lack of a shared and generalized understanding of ‘education quality’, there have been several initiatives aiming to assess and ensure it, most in the form of quality assurance processes (QA). The need to implement quality evaluation mechanisms has been present in the European discourse since the end of the 1990s and was directly and more detailed addressed in 2001 in the European Parliament and Council Recommendation on European cooperation in quality evaluation in school education. Since then, most European nations implemented their own QA systems (as shown in documents 18 and 19). Documents 18 and 19, while acknowledging the importance of an education of quality and stemming from this very same belief, do not present, themselves, a definition of education quality. The documents, instead, provide a picture of what countries have done and the processes they have implemented to ensure and promote the quality of education, revealing national QA systems with evaluations at the students’ results level, teachers’ level, and, inmost countries, at the school level [institutional evaluation (document 18)]. According to the analysis, these evaluation processes address a wide range of aspects, from educational processes to products (document 18) including, in most nations, aspects related to students’ academic results, teaching and learning, and school management practices (document 19). However, despite the range of such processes, considering the components of quality and the priorities for education found in the analysis, it seems that some QA processes may be falling short of a comprehensive evaluation of education quality and could be updated to address the complexity of the schooling process better.

7 Conclusions and recommendations

Recalling this paper’s aim to conceptualize ‘quality of education’ from the point of view of the European official political discourse on education, and bearing all of the above in mind, it is possible to state that education of quality is oriented toward preparing people to contribute to the social and political project, with the necessary knowledge and set of skills and competences to be productive; but is also an education with high-quality processes, translated in motivated and well-prepared professionals – teachers and leaders –, adequate conditions and environments – that are inclusive, healthy and meaningful –, which is also closely monitored and evaluated. With this conceptualization in mind, it appears that to define quality, scholars, politicians and professionals should pay attention to the following parameters: the extent of promotion of students /individuals’ full development, with academic knowledge and transversal and social skills; the richness of educational processes including a diversified educational offer and inclusive and meaningful practices and learning environments and opportunities; the professionals, teachers and leaders, their quality, training and working conditions; the processes for monitoring and evaluating educational practices and outcomes to ensure quality and promote improvement.

However, while this comprehensive perspective seems to check different boxes and appears to be somewhat holistic, attention should be paid to the specifics found in the documents, particularly in the roles and functions attributed to education within a context of political influence and convergence, as is the European one (Ball, 2001; Robertson and Roger, 2001; Nóvoa and Lawn, 2002; Dale, 2004; Steiner-Khamsi, 2004; Robertson, 2009), as this is the official discourse that influences and steers, even if implicitly, the educational policies and action in the national contexts. It is also noteworthy to acknowledge that despite the weight of the European official discourse in member-states policies and practices, countries have specific social, political, and cultural characteristics that permeate and influence their understanding of the supranational orientations, in line with the concept of “enactment” (Ball et al., 2011a) and the argument that the concept of quality depends of such conditions (Doherty, 2008; Ishihara-Brito, 2013; Lee and Zuilkowski, 2017; Moreno, 2017; Joshi, 2018; Egido, 2019; Zheng, 2020). Therefore, government and decision-makers’ interpretations of European orientations and guidelines can differ significantly and lead to highly distinctive measures, particularly considering the ambivalence of many documents. This could explain the differences found in the priorities established for education in various countries, of which the curricular design is a solid example (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2012).

With all of the above in mind, it is deemed important to highlight some final considerations, as follows:

• As stated, defining ‘Quality of education’ is as complex as the concept itself. Based on the results of this study, to achieve a definition, it could be helpful to resort to the identification of what constitutes quality, meaning, of its components. This paper provides somewhat of a structure of the components considered in the European political discourse. However, others could be added to the framework according to the context in which the concept is debated and defined. In essence, it is a question of specifying the understanding of what constitutes quality education, what factors, and what aspects of education are essential to ensure quality educational and school processes capable of achieving significant results. This specification will allow all those involved in improving educational quality to analyze their realities and identify the aspects that need improvement to achieve the desired quality. However, although this is a helpful approach, it is important not to fall into instrumentalism and compartmentalization of such a broad concept as quality. In other words, it is necessary that this specification does not distract attention from the bigger picture and that the close relationship between quality components is kept in mind.

• Governments and countries serve as mediators between the European agencies’ orientations and the national contexts, deciding what priorities are established, what processes are to be adopted and, ideally, adapted, and what path to follow afterward. This means that there is a need for a very conscious and critical analysis of political orientations coming from European agencies when thinking and deciding on Education at the national, and consequently, local, levels so as not to jeopardize national expectations, maintaining a balance between the European and the national contexts (Lange and Alexiadou, 2007; Dale, 2008; Villalba, 2015; Lawn, 2019; Ozga, 2020a).

• It is essential to explore the orientations coming from the European legislation to effectively understand what they are aiming at and what it means in terms of practice from a critical stance, being aware of the sometimes-opposite discourses when enacting (Ball, 1994; Ball et al., 2011a; Ball et al., 2011b; Heimans, 2012) the policies. For instance, the difference found in “what is expected of education” and the “components of quality,” which seem to push the educational action in different directions, one more instrumental and one more humanistic, or, more alarming, to bend the educational process to operationalizing these goals.

• When producing the recommendations and guidelines, European policy-makers should be aware of the inconsistencies and contradictions of the discourse, as such documents can be received and implemented in nations without proper critical thinking (Ozga, 2020a). This is particularly important if a policy targets a specific aspect (component) of education or educational quality, such as academic results or competencies. It is, thus, necessary to provide a broader framework, highlighting the connection between different components and how they contribute to the intended goal. This approach, while present in some of the analyzed documents, is not generally adopted and could be worth considering. Countries should be aware of the political role of education, its ideological stance, emerging from the European documents’ orientations, which seem to use education as an instrument for Europe – the European Union – to reach a particular position of power in the world, rather than focusing on the primary role of education that is promoting learning and the full development of people.

As a final point, it is important to mention that the documents trace an oscillating evolution of the European political discourse regarding the various aspects identified in the paper regarding ‘education quality’. If in ‘What is expected of education’ and ‘Components of education quality’ there seems to be an underlying focus on education products (results and training workers) and, therefore, a market-oriented consideration of education and its quality, in the ‘Priorities for Education’ the scenario is almost opposite. Nonetheless, it is important to be aware and alert regarding the marketization of education and the absence of more humanistic aspects in educational policies, particularly as we witness the rise of extremist right-wing parties to power in many European and worldwide nations (e.g., USA, Italy, and Hungary, among others).

Finally, this paper does not intend to present a formula for achieving education quality nor define it definitively. It aims to understand how education and its quality have been perceived and presented in European normative documents that countries have committed to following since becoming part of the European Union. Hence, this paper aims to develop an understanding of this topic that, while not indisputable, can help those interested in education to conceptualize ‘quality of education’ and what it means for educational processes from a broader perspective. Likewise, it was not intended to criticize the policies or present a judgment on their content but to identify and map the main ideas, creating an attempted x-ray of the European political discourse on ‘quality of education’ and what it entails, to try to clarify the underlying conception of the concept and provide a sort of framework for its understanding. Furthermore, the paper’s conclusions may help those invested and involved in education to understand better what is meant by ‘quality of education’ and what constitutes it, thus helping to steer their professional practices toward such a goal. Nonetheless, although the aim was to analyze only the European discourse and documents that clearly presented the expression ‘quality’ in their texts, this could limit the results achieved, as there may be other relevant European documents to take into consideration that provide complementary inputs, or documents from other organizations such as OECD, United Nations or UNESCO equally relevant.

Author contributions

CF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by national funds, through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, IP (FCT), under the research contract established under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Individual Programme [grant no. CEECIND/04172/2017]; and by the FCT, under the multiyear funding awarded to CIIE [grant nos. UIDB/00167/2020 and UIDP/00167/2020].

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For the purposes of simplifying the writing and reading of the text, the expressions education quality, quality of education and education of quality will be used as synonyms and interchangeably.

2. ^For the purposes of simplifying the writing and reading of the text, the terms European and Europe will be used to refer to the discourse emanating from the European Union and its agencies with political representation and ‘power’.

References

Aderet-German, T., and Ben-Peretz, M. (2020). Using data on school strengths and weaknesses for school improvement. Stud. Educ. Eval. 64:100831. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.100831

Afonso, A. (2013). Mudanças no Estado-avaliador: comparativismo internacional e teoria da modernização revisitada. Rev. Bras. Educ. Méd. 18, 267–284. doi: 10.1590/S1413-24782013000200002

Alexiadou, N. (2007). The Europeanisation of education policy: researching changing governance and ‘new’ modes of coordination. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2, 102–116. doi: 10.2304/rcie.2007.2.2.102

Amado, J., Costa, A., and Crusoé, N. (2017). “A técnica de análise de conteúdo” in Manual de Investigação qualitativa. ed. J. Amado (Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra), 303–354.

Apple, M. (2019). On doing critical policy analysis. Educ. Policy 33, 276–287. doi: 10.1177/0895904818807307

Apple, M., and Beane, J. (2007). Democratic schools: lessons in powerful education. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Ball, S. (1990). Politics and Policy Making in Education: Explorations in Policy Sociology. London: Routledge.

Ball, S. (1994). Some reflections on policy theory: a brief response to Hatcher and Troyna. J. Educ. Policy 9, 171–182. doi: 10.1080/0268093940090205

Ball, S. (1998). Big policies/small world: an introduction to international perspectives in education policy. Comp. Educ. 34, 119–130. doi: 10.1080/03050069828225

Ball, S. (2001). Diretrizes políticas globais e relações políticas locais em educação. Curr. Front. 1, 99–116.

Ball, S., Maguire, M., and Braun, A. (2011a). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. London: Routledge.

Ball, S., Maguire, M., Braun, A., and Hoskins, K. (2011b). Policy subjects and policy actors in schools: some necessary but insufficient analyses. Discourse 32, 611–624. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2011.601564

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research, critique. Mayland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 21, 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., and Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 21, 624–640. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Bowe, R., Ball, S. J., and Gold, A. (1992). Reforming education and changing schools: case studies in policy sociology. London: Routledge.

Carrington, S., Spina, N., Kimber, M., Spooner-Lane, R., and Williams, K. E. (2021). Leadership attributes that support school improvement: a realist approach. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 42, 151–169. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2021.2016686

Castells, M. (2000). Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society. Br. J. Sociol. 51, 5–24. doi: 10.1080/000713100358408

Charlot, B. (2013). A mistificação pedagógica: realidades sociais e processos ideológicos na teoria da educação. São Paulo: Cortez Editora.

Chen-Levi, T., Buskila, Y., and Schechter, C. (2024). Leadership as agency. Int. J. Educ. Reform 33, 127–141. doi: 10.1177/10567879221086274

Codd, J. A. (1988). The construction and deconstruction of educational policy documents. J. Educ. Policy 3, 235–247. doi: 10.1080/0268093880030303

Creemers, B., and Kyriakides, L. (2015a). Developing, testing, and using theoretical models for promoting quality in education. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 26, 102–119. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2013.869233

Creemers, B., and Kyriakides, L. (2015b). “Educational effectiveness, the field of” in International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. ed. J. D. Wright (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 224–228.

Dale, R. (2004). Globalização e educação: demonstrando a existência de uma “cultura educacional mundial comum” ou localizando uma “agenda globalmente estruturada para a educação”? Educ. Soc. 25, 423–460. doi: 10.1590/S0101-73302004000200007

Dale, R. (2008). Construir a Europa através de um Espaço Europeu de Educação. Rev. Lusofona Educ. 11, 13–30.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: an introduction to the philosophy of education. London: Macmillan Publishing.

Doherty, G. (2008). On quality in education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 16, 255–265. doi: 10.1108/09684880810886268

Egido, M. (2019). Percepciones del Profesorado sobre las Políticas de Aseguramiento de la Calidad Educativa en Chile. Educ. Soc. 40:e0189573. doi: 10.1590/ES0101-73302019189573

Ehren, M., and Swanborn, M. (2012). Strategic data use of schools in accountability systems. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 23, 257–280. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2011.652127

Ehren, M., and Visscher, A. (2008). The relationships between school inspections, school characteristics and school improvement. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 56, 205–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00400.x

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2012). Developing key competences at School in Europe: challenges and opportunities for policy. Luxembourg: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice.

European Union (1957). Treaty establishing the European Community (consolidated version). Rome: European Union.

Fernandes, P., Leite, C., Mouraz, A., and Figueiredo, C. (2013). Curricular contextualization: tracking the meanings of a concept. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 22, 417–425. doi: 10.1007/s40299-012-0041-1

Figueiredo, C., Leite, C., and Fernandes, P. (2017). Avaliação externa de escolas: do discurso às práticas: uma análise focada em Portugal e em Inglaterra. Meta: Aval. 9:1205. doi: 10.22347/2175-2753v9i25.1205

Figueiredo, C., Leite, C., and Fernandes, P. (2018). Uma tipologia para a compreensão da avaliação de escolas. Rev. Bras. Educ. 23, 1–25. doi: 10.1590/s1413-24782018230018

Fullan, M., and Hargreaves, A. (1998). What’s worth fighting for out there? New York: Teachers College Press.

Grek, S. (2009). Governing by numbers: the PISA ‘effect’ in Europe. J. Educ. Policy 24, 23–37. doi: 10.1080/02680930802412669

Grek, S., Lawn, M., Lingard, B., and Varjo, J. (2009). North by northwest: quality assurance and evaluation processes in European education. J. Educ. Policy 24, 121–133. doi: 10.1080/02680930902733022

Heimans, S. (2012). Education policy, practice, and power. Educ. Policy 26, 369–393. doi: 10.1177/0895904810397338

Hopkins, D., Stringfield, S., Harris, A., Stoll, L., and Mackay, T. (2014). School and system improvement: a narrative state-of-the-art review. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 25, 257–281. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.885452

Ishihara-Brito, R. (2013). Educational access is educational quality: indigenous parents’ perceptions of schooling in rural Guatemala. Prospects 43, 187–197. doi: 10.1007/s11125-013-9263-0

Joshi, P. (2018). Identifying and investigating the “best” schools: a network-based analysis. Compare 48, 110–127. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2017.1293504

Julien, H. (2008). “Content analysis” in The sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. ed. L. Given (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.), 120–121.

Kumar, K., and Sarangapani, P. (2004). History of the quality debate. Contemp. Educ. Dialogue 2, 30–52. doi: 10.1177/097318490400200103

Lange, B., and Alexiadou, N. (2007). New forms of European Union governance in the education sector? A preliminary analysis of the open method of coordination. Eur. J. Educ. Res. J. 6, 321–335. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2007.6.4.321

Lawn, M. (2006). Soft governance and the learning spaces of Europe. Comp. Eur. Polit. 4, 272–288. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110081

Lawn, M. (2019). Governing education in the European Union: networks, data and standards. Roteiro 44, 1–16. doi: 10.18593/r.v44i3.20897

Lee, J., and Zuilkowski, S. (2017). Conceptualising education quality in Zambia: a comparative analysis across the local, national and global discourses. Comp. Educ. 53, 558–577. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2017.1348020

Leite, C., and Fernandes, P. (2010). Desafios aos professores na construção de mudanças educacionais e curriculares: Que possibilidades e que constrangimentos. Educação 33, 198–204.

Leite, C., Fernandes, P., and Figueiredo, C. (2018). Challenges of curricular contextualisation: teachers’ perspectives. Aust. Educ. Res. 45, 435–453. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0271-1

Mainardes, J. (2006). Abordagem do Ciclo de Políticas: uma contribuição para a análise de políticas educacionais. Educ. Soc. 27, 47–69. doi: 10.1590/S0101-73302006000100003

Moreno, J. (2017). La calidad de la educación básica mexicana bajo la perspectiva nacional e internacional: el caso de lectura en tercero de primaria. Perf. Educ. 157, 162–180.

Mouraz, A., Leite, C., and Fernandes, P. (2013). Teachers’ role in curriculum design in Portuguese schools. Teach. Teach. 19, 478–491. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2013.827363