- 1Department of Psychology, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL, United States

- 2Department of Physical Therapy, Samford University, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 3School of Communication and Media, Ulster University, Belfast, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Human Studies, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 5Department of Physical Therapy, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 6UAB Center for Engagement in Disability Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 7UAB Center for Exercise Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 8Department of Physician Assistant Studies, Samford University, Birmingham, AL, United States

Introduction: The purpose of this pilot study was to provide preliminary evidence on the effects of an instructor swearing during a lecture on learning and student perceptions in a field classroom setting.

Methods: First-year doctoral students (n = 36) who were enrolled in a Human Anatomy course within a physical therapist education program were randomly assigned to a non-swearing lecture (NSL; n = 18) or a swearing lecture (SL; n = 18) on basic human anatomy. A single instructor provided identical 40-min lectures to each student group except for two inserted phrases to emphasize content which differed between NSL and SL. For the NSL, the instructor emphasized the content by stating: “Anatomy just makes sense sometimes” and “Anatomy is interesting.” For the SL, the content was emphasized by saying “Anatomy just makes f***ing sense sometimes” and “This s**t is interesting.” Following the lectures, a 10-question post-lecture knowledge retainment assessment (“pop” quiz) was given to the NSL and SL groups. The SL group also completed a 14-item mixed methods survey with 12 Likert and 2 open-ended questions regarding student perceptions.

Results: There were no differences in knowledge retainment on the “pop” quiz scores between the NSL and SL (p = 0.780). Results from the mixed methods survey suggested an overall neutral to positive response to the SL whereby swearing did not negatively impact learning or perception of the instructor or the class.

Discussion: Collectively, this pilot field study provides preliminary evidence suggesting that swearing during a lecture in higher education neither helps nor hurts student learning or perceptions of instructors and may positively impact student perceptions of the class. Future studies with additional control and larger diverse populations are warranted.

1 Introduction

Swearing is defined as using emotionally loaded terms, which are taboo in a given culture and have a strong potential to cause offense (Beers Fägersten, 2012). Due to the taboo/offensive potential, swearing uniquely alters responses to various stimuli and is relationally “powerful.” Indeed, swearing elicits anomalous effects, both negative and positive, that are not readily observed with other forms of language use (Stapleton et al., 2022). While some studies have reported negative or mixed effects, several others have demonstrated that swearing can positively impact attention (Kwon and Cho, 2017; Mullins, 2020), memory (Jay et al., 2008), and perceptions of the speaker (Hamilton et al., 1990; Cavazza and Guidetti, 2014; Generous et al., 2015; Generous and Houser, 2019; Mullins, 2020). These findings are potentially relevant in higher education given the benefits of student attention and positive speaker perception in the classroom. While widely thought of as inappropriate or unprofessional behavior in the classroom (Jay and Janschewitz, 2008), the topic of swearing warrants new investigation in light of evidence showing the potential for positive, albeit highly contextualized, effects of swearing on attention, recall, and perceptions of the speaker. Previous evidence has suggested that the majority of college students in the United States say they encounter professor swearing, with only 9% of students indicating they “never” encounter instructor swearing (Generous and Houser, 2019), further supporting that this topic is relevant in higher education.

In experimental studies, swear words have often been shown to command more attention and lead to improved short-term memory when compared to non-taboo language. Jay et al. (2008) conducted a study in which participants were shown 36 words (12 neutral words, 12 emotional words, 12 swear words). After reading the 36 words, participants completed a math worksheet to stimulate forgetting the 36 words. After a surprise recall test, participants remembered 39% of the swear words compared to 13% of the emotional words and 7% of the neutral words (Jay et al., 2008). Jay et al. (2008) proposed that the higher recall for swear words is explained by the emotional arousal that occurs when swearing. Swearing increases arousal and, therefore, may result in increases in attention and recall. Conversely, there is some evidence that swear words are cognitively processed more slowly than neutral words and that swearing may actually interfere with the processing of other stimuli (Sulpizio et al., 2019; Donahoo et al., 2022). Donahoo et al. (2022) found that including a swear word in a sentence delayed the cognitive processing of that sentence, but did not affect the comprehension accuracy of the sentence (Donahoo et al., 2022). In other words, sentences containing a swear word were not more or less difficult to understand, compared with those that did not contain a swear word. MacKay et al. (2004) had participants complete a taboo Stroop test which required participants to name the color of randomly intermixed swear and neutral words. This study found that participants took longer to name the color of swear words than the color of the neutral words but were able to recall more swear words than neutral words in a surprise memory test. This study also found improved memory for colors consistently associated with swear words compared to neutral words and that swear words positively impacted the recall of “neighboring” words (MacKay et al., 2004). This suggests that swear words trigger a recall link to the information delivered with the swear word.

Research on social perceptions of swearing and swearers, including instructors/speakers, shows mixed outcomes (Generous et al., 2015). Since swearing, by definition, has the strong potential to cause offense, is it not surprising that swearing can produce higher ratings of message and swearer offensiveness (DeFrank and Kahlbaugh, 2019). For example, it has been shown that regular swearers are often perceived as socially inept (Winters and Duck, 2001) and untrustworthy (Hamilton et al., 1990). Contrary to this, swearing has been suggested to positively impact speaker evaluations on solidarity dimensions, such as informality, relatability, and humor. Cavazza and Guidetti (2014) found swearing may increase persuasiveness of the swearer's message. Swearing can also increase perceptual ratings of speaker passion and enthusiasm (Hamilton et al., 1990). The latter finding has high amounts of relevance for educational settings, where a professor's enthusiasm for a subject may be expected to impact student engagement levels (Lazarides et al., 2018).

In the classroom, investigations of instructor swearing have produced equivocally nuanced and contextualized findings. Some research has found that instructor swearing may negatively impact the student-instructor relationship. Some evidence has suggested instructor swearing negatively affects students' perceptions of the instructor's credibility (Frisby and Sidelinger, 2013; Sidelinger et al., 2015; Allard and Holmstrom, 2023). Allard and Holmstrom (2023) showed that students perceived instructors as more relatable when they abstained from taboo language which is likely also linked to perception of credibility. Instructor credibility is believed to be one of the most important attributes of an instructor in higher education with higher credibility leading to improved student attention (Brann et al., 2005). Instructors who are perceived as more credible tend to be evaluated more positively by students. Students also view instructor swearing as an emotional tool to express frustration, anger, passion, excitement, or comfortability (Mullins, 2020). With respect to expressing passion, excitement, and comfortability, instructor swearing may effectively make the subject stand out, foster attention, decrease the formality of the classroom, humanize the instructor, increase the authenticity of their teaching, and make the instructor more relatable. Mullins (2020) concluded that the use of swear words to display passion and draw attention to a subject can increase the relatability of the instructor and their perceived authenticity. This may allow students to feel more comfortable in the classroom and encourage students to engage in class discussions.

While intriguing, most investigations to date have used highly controlled simulated classroom environments or recalls of student experiences to study the effects of instructor swearing. Despite methodological, ethical, and unintended behavioral modification challenges of conducting a field study on instructor swearing, there is a need for an initial, exploratory, and ecologically valid study to examine the impact of instructor swearing on learning outcomes and student perceptions. A better understanding of the effects of swearing in the classroom would provide instructors with guidance for the inclusion and/or avoidance of swearing into teaching and speaking. Given the conflicting literature regarding the impact of swearing on student attention, recall, and perceptions of the instructor/speaker, the purpose of this pilot field study is to examine the effects of swearing by an instructor on student learning and student perceptions in a real-world university classroom setting. Due to the conflicting, anomalous, nuanced, and contextualized findings from the previous literature on the impact of swearing on memory and perceptions, we hypothesized that instructor swearing would simply: (1) impact student performance on a post-lecture knowledge retainment assessment (“pop” quiz), (2) impact student perceptions of the instructor, and (3) impact student perceptions of the class.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

Using a mixed-methods approach, university doctoral students (n = 36) enrolled in the same Human Anatomy course were randomly divided into two groups: (1) Non-swearing lecture (NSL), (2) Swearing lecture (SL). A single instructor gave an identical 40-min anatomy lecture without (NSL) or with (SL) the presence of swearing. Following the lectures, a 10-question post-lecture knowledge retainment assessment was given. Additionally, a 14-item mixed methods survey with 12 Likert and 2 open-ended questions regarding student perception of the instructor was completed by the SL group. Groups were compared for “pop” quiz scores and the perceptions of the SL group were further characterized with the mixed methods survey.

2.2 Participants

A convenience sample comprising an entire cohort of first-year, first-semester doctoral students (n = 36) enrolled in a Human Anatomy course within a physical therapist education program at Samford University was invited to participate in this study. This course was a required component of the curriculum for this cohort. Samford University, a private Christian institution located in Birmingham, Alabama, USA, serves ~6,100 students. Descriptive characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Prior to data collection, ethical approval was sought and granted by the appropriate Institute Review Board from the first author's institution; approval number EXPD-HP-23-SUM-2. Written and verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the beginning of data collection, and all methods and procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3 The instructor and human anatomy course

A 42-year-old Caucasian male instructor (author NBW) with 9 years of full-time experience as a lecturing faculty member delivered the lecture material. The Human Anatomy course used in this study is a doctoral level course taken by first year physical therapy doctoral students, with the primary objective for students to develop knowledge, skill, and ability related to the anatomical organization and the anatomical structures and functions of the human body. The instructor (NBW) was not the instructor of record for the Human Anatomy course used in this study and his only prior experience with teaching the student participants in this study was as a laboratory assistant in this Human Anatomy course. All material was delivered in English which was the instructor's native language.

2.4 Lecture interventions

For the lecture, students were randomly divided into a NSL (n = 18) or SL (n = 18) group using simple randomization via random.org, with the NSL group receiving a lecture without swearing and the SL group receiving a lecture that included two swear words. Habituation to swearing has been observed in various contexts (Stephens and Umland, 2011; Lafreniere et al., 2022). To minimize potential habituation effects, swearing was limited to two occurrences for the SL group during the 40-min lecture. For the SL, the words “fuck” and “shit” were included as these have been suggested to be the most commonly used swear words in the classroom (Generous et al., 2015) and are generally considered to be prototypical examples of “strong” swearing (Beers Fägersten, 2012; Love, 2021; Beers Fägersten and Stapleton, 2022; Stapleton et al., 2022). The lecture content consisted of a 40-min session on foot and ankle arthrology. During the NSL, the instructor said the pre-determined phrases “Anatomy just makes sense sometimes” 10 min into the lecture, and “Anatomy is interesting” 30 min into the lecture. During the SL, the instructor said, “Anatomy just makes fucking sense sometimes” and “This shit is interesting.” The intended use of the pre-determined phrases by the instructor was to emphasize course content and gain the focus and attention of the class. The pre-determined phrases for both NSL and SL were consistent with respect to timing, inflection, and intended purpose with the only difference being the addition of the swear word. Students were informed through the informed consent process that the lecture was part of a research experiment.

The Human Anatomy course involved in this study traditionally delivers a 2-h lecture to the entire 36-student cohort three times per week. However, for the purpose of this experiment, the students were divided into two groups, the SL group and the NSL group, which were assigned to separate classrooms on different floors of the same building during a single 2-h lecture block. The goal of this separation was to minimize interactions between the groups throughout the 2-h lecture block. During the first hour, the course coordinator (author RMC) conducted a review session for the SL group, focusing on material unrelated to the lecture intervention used in this study. Meanwhile, the instructor responsible for the lecture intervention (author NBW) delivered the 40-min lecture to the NSL group. At the start of the second hour, the two groups remained in their respective classrooms while the instructors switched places, further preventing communication between the groups. During this time, the course coordinator (author RMC) provided a review session to the NSL group, while the lecture intervention instructor (author NBW) delivered the 40-min lecture to the SL group. This arrangement ensured that both groups received the same content while maintaining the experimental conditions necessary for the study.

2.5 Acute recall assessment and perception survey

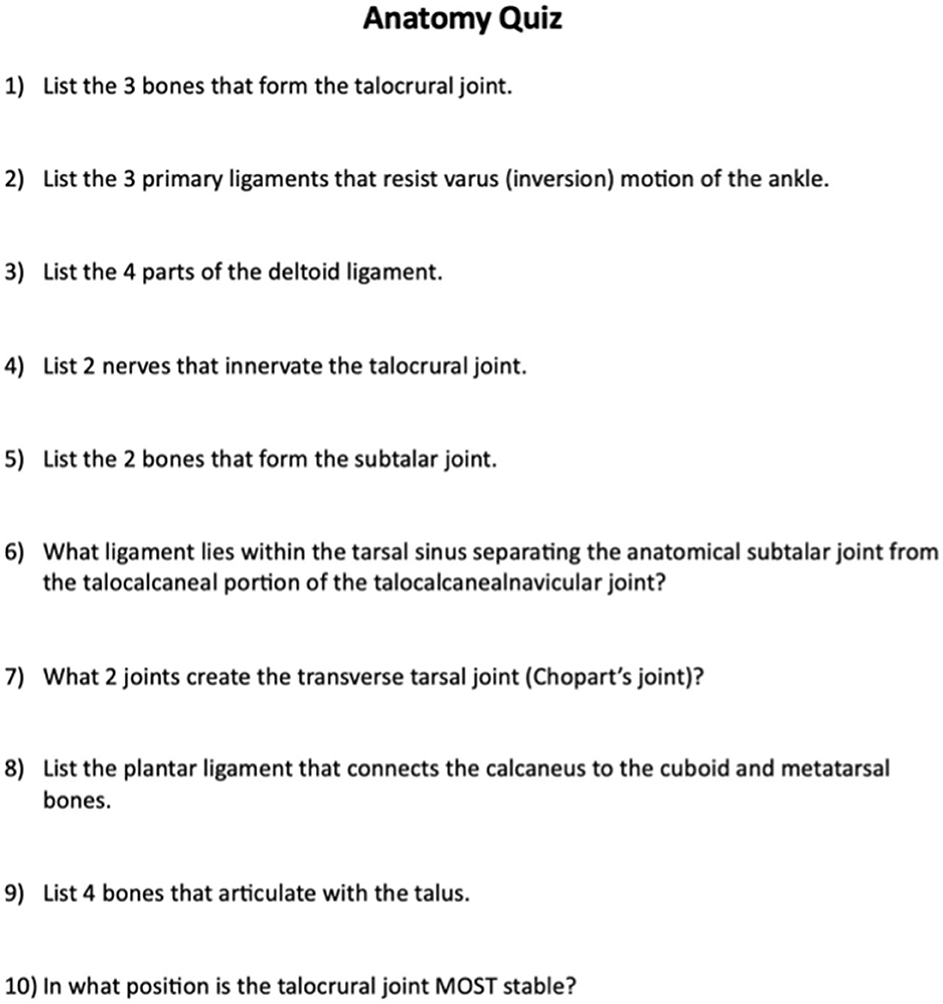

The authors developed a knowledge retainment assessment (“pop” quiz) to measure student learning immediately after the lecture (Le, 2012). This assessment included 10 free-response questions (see Figure 1) pertaining to the content that was delivered. Each question had one to four answers, giving this 10-question quiz 23 possible points. All students completed the assessment in < 15 min. Student perceptions in the SL group were assessed using a novel 14-item electronic questionnaire created by the authors and administered via Qualtrics (Qualtrics LLC; Provo, UT; see Figure 2). This questionnaire, designed specifically for this study, measured students' reactions and perception of the swearing that occurred during the lecture. Only the SL group was eligible to complete the survey and completed it immediately following the completion of the “pop” quiz. The survey contained 2 open-ended and a 12 Likert scale questions (5 point) pertaining to the perceptions of the instructor and class session. Both the 10-question “pop” quiz and 14-item questionnaire were developed specifically for this experiment. However, the psychometric properties of these tools, including their reliability and validity, have not been established.

2.6 Data analysis

All data were analyzed using Jamovi statistical software (Version 0.9; Sydney, Australia). Normality of data distribution was checked for all variables using the Shapiro-Wilk method. For the knowledge retainment assessment (“pop” quiz), an independent t-test was used to compare scores of NSL and SL groups. For the Likert scale question portion of the perception survey, all data violated normality assumptions and a non-parametric one-sample t-test (Wilcoxon rank) was employed. A test value of 4, which corresponds to the Likert choice “agree,” was used to compare participants' responses against the test value (≠test value). This was done in efforts to make conclusions on participant responses against the response of someone who would “agree” with the statement. All quantitative data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 a priori.

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative analyses

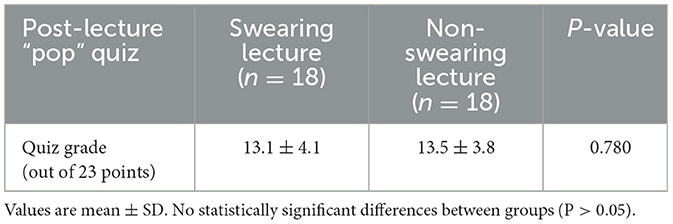

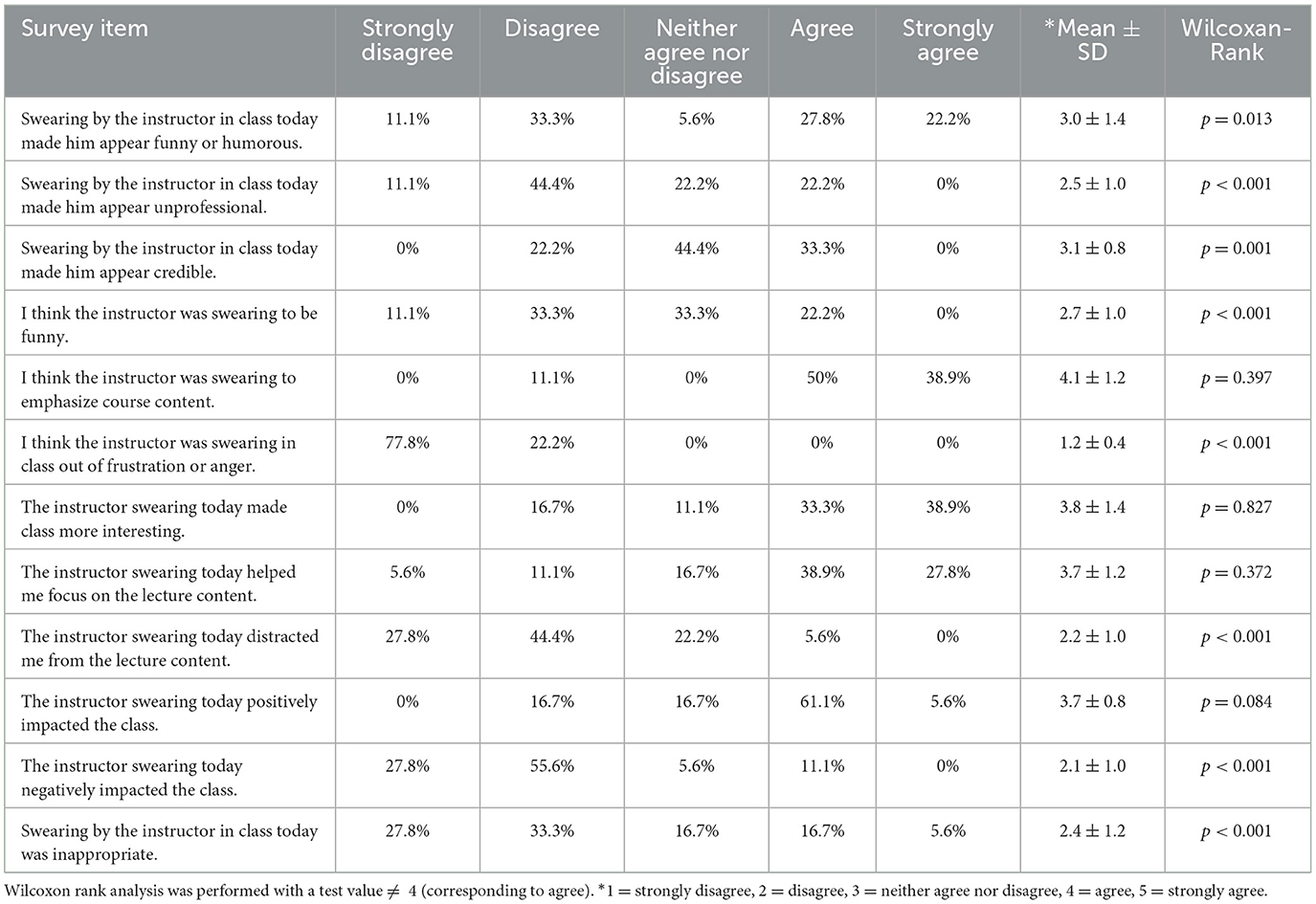

Performance on the knowledge retainment assessment (“pop” quiz) is shown in Table 2. Analysis revealed that there were no statistical differences in scores between NSL and SL groups (p = 0.780). Results from the Likert scale portion of the perception survey are shown in Table 3. Participants answered significantly lower than the “agree” test value for survey items related to perceived humor, unprofessionalism, credibility, and anger from the instructor. Furthermore, participants gave answers that were not statistically different from the “agree” test value related to perceptions of positive impacts on the class, emphasis on content, interest in content, and focus. Answers related to perceived inappropriateness and negative class experiences were significantly lower than the “agree” test value.

3.2 Qualitative analyses

The qualitative data collected from two open-ended questions on the perception survey completed by the SL group were analyzed for general themes.

3.2.1 How often did the instructor swear during this class session?

For the question “How often did the instructor swear during this class session?,” 17 of the 18 students in the swearing lecture reported hearing the instructor swear twice during the lecture, with one student hearing one swear word during the same lecture.

3.2.2 What was your reaction when the instructor swore during class today?

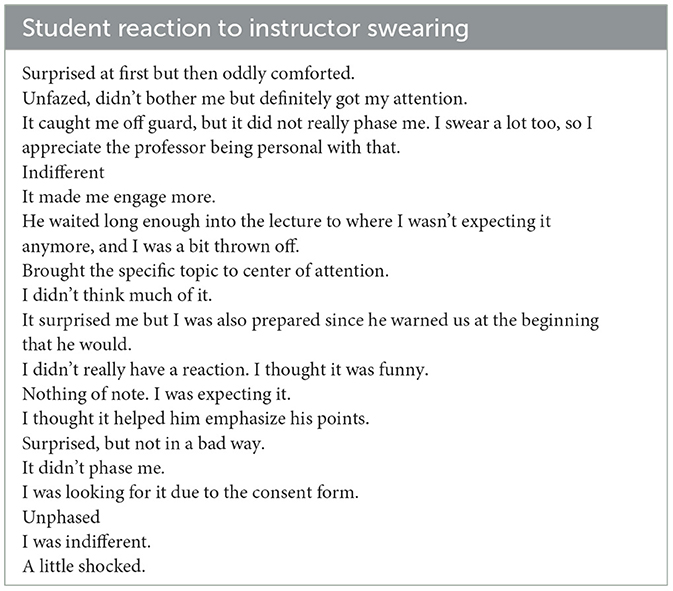

For the question “What was your reaction when the instructor swore during class today?,” eight out of the 18 students reported being unfazed or indifferent, five students said they were surprised or caught off guard, three students said they were expecting it, and two students stated the swearing increased their attention. For example, one student said “Unfazed, didn't bother me but definitely got my attention.” Another student said, “It caught me off guard, but it didn't really phase me. I swear a lot too, so I appreciate the professor being personal with that.” Other comments included, “Surprised at first but then oddly comforted,” “Brought the specific topic to the center of attention,” and “I thought it helped him emphasize his points.” Finally, students also reported that they were expecting to hear swearing and said, “It surprised me but I was also prepared since he warned us at the beginning that he would” and “I was looking for it due to the consent form.” Student responses to “What was your reaction when the instructor swore during class today?” are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Swearing survey results for “What was your reaction when the instructor swore during class today?” This is a series of individual student responses; one per students for a total of 18 responses.

4 Discussion

This study included an instructor using strategic swearing to emphasize course content and gain the focus and attention of the class. The instructor in this study swore twice during a 40-min anatomy lecture on foot and ankle arthrology, including “Anatomy just makes fucking sense sometimes” 10 min into the lecture, and “This shit is interesting” 30 min into the lecture. “Shit” and “fuck” were the swear words chosen for this study, as they have been reported as the most commonly used swear words in the classroom (Generous et al., 2015) and they are considered both prototypical and strong swearing (Beers Fägersten, 2012; Love, 2021; Beers Fägersten and Stapleton, 2022; Stapleton et al., 2022). There was no difference between the SL group and NSL group on knowledge retainment outcomes as assessed by the overall scores on a post-lecture “pop” quiz. Moreover, swearing by the instructor did not significantly impact students' perceptions of the instructor. However, it did appear to influence student perceptions of the class. The outcomes of this current exploratory study, in conjunction with the study hypotheses, will serve as a framework for discussion.

This study was the first to directly examine the effects of instructor swearing in a field classroom setting. As such, it was inherently exploratory in nature and purpose, with a dual focus on student learning (knowledge retainment) and perceptions. Before discussing the findings, it is important to note that while a core aim of the research was to examine the effects of instructor swearing in a real-life classroom setting, certain methodological and ethical imperatives affected the extent to which this aim could be truly achieved. Firstly, in order to directly examine knowledge retainment and perception outcomes, it was necessary to use a quasi-experimental design, with pre-planned swearing, and the construction of experimental and control conditions. Secondly, for ethical reasons, it was essential that students be informed, at least in part, of the nature of the study before they gave informed consent. Specifically, the student participants were informed that during the class, the instructor might “use emotional language, which could include swearing” as part of the verbal and written informed consent. This is likely to have cued the participants in a number of ways. For example, they might have been actively anticipating or “looking out” for the swearing, which might, in turn, have distracted their attention from other aspects of the lecture. In addition, foreknowledge would have mitigated any possible “shock factor” on hearing the swear words, which might have mediated the potential effects on attention and memory. Finally, knowing that the instructor was swearing as part of a research project is likely to have attenuated the effects of this behavior on their perceptions of him. As Stapleton (2020) has shown, the perception effects of speaker swearing are strongly related to the listener's attribution for why he or she swore. All of these methodological factors, then, may be expected to have had some effect on the different outcome measures.

The hypothesis that instructor swearing will impact students' knowledge retainment was not supported. The swearing utilized by the instructor during a lecture in this study did not impact overall student grades on a post-lecture “pop” quiz when compared to not swearing in a lecture. Interestingly, the NSL group's quiz average was higher than the swearing group's quiz average, albeit not statistically significant (Table 2).

Students may have been focused on the swear word used, taking their attention away from the lecture content, which may have contributed to the NSL group's quiz average being higher than the SL group's average. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that swear words may interfere with the processing of other stimuli (Sulpizio et al., 2019; Donahoo et al., 2022). Swear words are processed more slowly than non-swear words (Sulpizio et al., 2019), and reading a sentence with a swear word will delay the cognitive processing of that sentence (Donahoo et al., 2022). Although swear words are processed more slowly than non-swear words, swear words are found to be more accurately processed than non-swear words (Sulpizio et al., 2019). Therefore, future studies should examine the effects of swearing on long term knowledge retainment. For example, would the findings of this current study change if the post-lecture “pop” quiz was administered at a later date instead of immediately after the lecture? Additionally, what impact would repeated exposure to swearing across multiple lectures have on knowledge retainment? These questions could provide valuable insights into the interplay between swearing and cognitive processing in educational settings.

For the free response question “What was your reaction when the instructor swore in class today?,” the most consistent theme was that students were unfazed by or indifferent to the swearing. Five students reported being surprised or caught off guard, and two students stated the swearing increased their attention. It may be that the students' feelings of “surprise” and “increased attention” were directed at the swearing itself and thus took attention away from the lecture content, which contributed to a non-statistically significant decreased performance on the “pop” quiz. Three students stated that they were expecting to hear swearing due to the informed consent, which may have affected their attention to content being presented during the lecture. This brings up an important limitation to this current study. Although this study took place in a field classroom setting, the students were nonetheless expecting to hear swearing due to the informed consent. The informed consent included language that “the instructor may use emotional language, which could include swearing.” The effects and perceptions of swearing are often due to the degree to which the swearing violates someone's expectations (Johnson and Lewis, 2010); therefore, the findings of this study are likely to have been affected by the students' foreknowledge that the instructor may swear during the class.

The hypothesis that instructor swearing will impact student perceptions of the instructor was not supported. The swearing by the instructor in this study did not significantly impact students' perceptions of the instructor as impacted by his swearing. But, as another unavoidable methodological artifact, some of these responses might be because students “knew” that the instructor was going to swear as part of a research study. Students averaged 3.0 and 3.1 on the survey items “Swearing by the instructor in class today made him appear funny or humorous” and “Swearing by the instructor in class today made him appear credible,” respectively, indicating students tended to neither agree nor disagree with those statements. This is inconsistent with the findings from Allard and Holmstrom (2023) where instructor swearing diminished students' perceptions of the instructor credibility. These inconsistences may be due to the small sample size or the intentional use of “fuck” and “shit” to emphasize course content in this current study, as compared with the hypothetical scenarios or the use of softer swear words “suck” and “damn” in the study by Allard and Holmstrom (2023). Nevertheless, there is an inconsistency across studies in the students' perception of instructor credibility when instructors swear. For the survey item “Swearing by the instructor in class today made him appear unprofessional,” students averaged 2.5, indicating student were halfway between disagreeing and neither agreeing nor disagreeing with that statement. Mullins (2020) found that act of swearing by an instructor does not automatically decrease their professionalism or credibility, as it is not the act of swearing that causes negative perceptions but the perceived intent behind the swearing. The findings in this study are consistent with Mullins (2020), where swearing by the instructor with the intent to emphasize course content did not make the instructor appear unprofessional or alter his credibility. However, while Mullins (2020) acquired data from focus groups of students asking about their retrospective accounts of swearing in the classroom, the current study was a field classroom study that informed students in advance that the instructor “may use emotional language, which could include swearing.” As previously stated, this informed consent is likely a confounding variable impacting student perceptions of the instructor.

The instructor in this study swore twice during a lecture with the intention to emphasize course content and gain the focus and attention of the class. The findings of the swearing survey suggest that the instructor's intentions for swearing were consistent with the students' perceptions of the instructor's intentions. Students agreed that the instructor swore to emphasize course content (4.1 on swearing survey item #7; Figure 2 and Table 3), while strongly disagreeing that the instructor was swearing out of frustration or anger (1.2 on swearing survey item #8; Figure 2 and Table 3). This is an important finding as previous research has found that instructor swearing is perceived as appropriate and positive when used to highlight course content and inappropriate when directed at a student or used to express frustration (Generous et al., 2015; Generous and Houser, 2019; Mullins, 2020). The fact that students agreed that the instructor was swearing to emphasize course content supports the finding that students tended to disagree with the statement “Swearing by the instructor in class today was inappropriate” (2.4 on swearing survey item #14; Figure 2 and Table 3).

The hypothesis that instructor swearing will impact student perceptions of the class appears to be supported. Students tended to agree that the instructor swearing made class more interesting and help them focus on lecture content (3.8 and 3.7 on swearing items #9 and #10, respectively; Figure 2 and Table 3). This is consistent with Mullins (2020), who found that students view instructor swearing as a method to foster attention and make the content stand out. Students disagreed that the instructor swearing distracted them from the lecture content and negatively impacted the class (2.2 and 2.1 on swearing survey item #11 and #13, respectively; Figure 2 and Table 3). Students averaged 2.4 on the survey question “Swearing by the instructor in class today was inappropriate,” suggesting students tended to disagree with the idea that the instructor swearing was inappropriate.

The age, gender, and race of the instructor may have impacted how the swearing was perceived by students. The instructor in this current study was a 42-year-old Caucasian male, which likely impacted the students' perceptions of his swearing. Age, gender, and race, and their interactions, need to be considered when interpreting the findings of this current study and future research. The complex discussions around the topics of age, gender, and race are beyond the scope of this manuscript; however, there is evidence for different perceptions of swearing, use of swearing, and outcomes of swearing depending on the age, gender, and race of the swearer (Jay and Janschewitz, 2008; Beers Fägersten, 2012; Guvendir, 2015; Beers Fägersten and Stapleton, 2022; Stapleton and Beers Fägersten, 2023). Future studies should specifically examine the variables of age, gender, and race on the effects of instructor swearing in the classroom.

Although this was the first lecture these students received from the instructor in this study, the students did have knowledge of and, likely, preconceived perceptions of the instructor prior to this lecture, as he has been a part of this course as a lab assistant. These preconceived perceptions of the instructor may have impacted the students' perceptions of his swearing. Students who thought positively or negatively of the instructor before the lecture may be more likely to interpret his swearing in a way that confirms those positive or negative perceptions. Students may justify or rationalize the instructor's swearing to maintain their preconceived positive or negative view of the instructor (Rasmussen, 2008; Stapleton, 2020).

5 Limitations and future research

This study was the first to directly examine the effects of instructor swearing in a field classroom setting, but several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study was not pre-registered and should therefore be considered exploratory. Additionally, the small sample size (n = 36) limits the generalizability of the findings and reduces statistical power to detect subtle effects. To avoid cross-condition contamination, participants were not exposed to both the SL and NSL conditions, as doing so might have prompted conscious or unconscious comparisons that could alter their natural reactions to swearing and affect the validity of the results. However, exposing participants to both conditions may offer advantages, such as increased statistical power by using participants as their own controls and richer insights through qualitative feedback comparing their preferences and perceptions of the two conditions.

The informed consent process included notifying participants that the instructor might swear. This foreknowledge likely influenced participant reactions, reducing the potential for surprise or shock, which could have otherwise affected attention and perception outcomes. Despite being conducted in a classroom setting, the study's experimental design, including pre-determined swearing and controlled conditions, does not fully replicate the spontaneous nature of swearing in a naturalistic classroom environment. Additionally, the instructor's specific characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race) may have influenced students' perceptions, making it difficult to generalize results to instructors with different demographic profiles. This study also used only two instances of swearing (“fuck” and “shit”), restricting insights into the effects of other swear words, frequencies, or contexts of swearing. Furthermore, the 10-question “pop” quiz and 14-item survey used in this study were designed specifically for this experiment, and their psychometric properties (e.g., reliability, validity) were not established. Finally, the instructor had prior interactions with students as a lab assistant, potentially introducing bias due to pre-existing perceptions of him.

Future research should examine how instructor characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race) influence the effects and perceptions of swearing, assessing whether these findings are consistent across diverse instructor profiles. Additional studies should explore the impact of different swear words, including in particular, those with different levels of “strength” or offensiveness, varying frequencies, and contextual factors (e.g., swearing to express frustration versus emphasizing content) to better understand their nuanced effects. Longitudinal studies are also needed to determine whether swearing has lasting effects on knowledge retention and student perceptions, including its potential impact over a semester-long course.

Interdisciplinary approaches combining insights from psychology, linguistics, and education could provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which swearing affects learning and perceptions. Ideally, to really explore the effects of classroom swearing in a naturalistic way, future research would include classroom-based studies without prior instructions to the students concerning the expectation of hearing the instructor swear. This may not be possible for ethical reasons, which leaves researchers with challenging methodological issues in conducting studies in real-life classroom settings to determine the utility of instructor swearing in the classroom. However, methodologically sound research in real-life classroom settings is required so that instructors better understand when, how, and if swearing can be used for reliable positive effects in the classroom; and conversely, when swearing should be avoided by instructors.

6 Conclusion

The present study found that a 42-year-old Caucasian male instructor saying “fuck” and “shit” during a 40-min lecture in an attempt to emphasize course content and gain attention did not significantly impact overall student performance on a post-lecture “pop” quiz when compared to not swearing during the lecture. Swearing by the instructor did not significantly impact students' perceptions of the instructor but did appear to impact student perceptions of the class. Although instructor swearing had an overall neutral to positive effect on student perceptions, it is challenging to justify the use of swearing by an instructor due to the possible negative consequences of swearing. In the current study, two students agreed that the instructor swearing negatively impacted the class and four students either agreed or strongly agreed that the instructor swearing was inappropriate, suggesting it may be impossible to swear indiscriminately with everyone in all situations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Samford University Institute Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RC: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allard, A., and Holmstrom, A. J. (2023). ‘Students' perception of an instructor: the effects of instructor accomodation to student swearing. Lang. Sci. 99:101562. doi: 10.1016/j.langsci.2023.101562

Beers Fägersten, K. (2012). Who's Swearing Now? The Social Aspects of Conversational Swearing. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Beers Fägersten, K., and Stapleton, K. (2022). ‘Swearing', in Handbook of Pragmatics Online (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 129–155.

Brann, M., Edwards, C., and Myers, S. A. (2005). Perceived instruction credibility and teaching philosophy. Commun. Res. Rep. 22, 217–226. doi: 10.1080/00036810500230628

Cavazza, N., and Guidetti, M. (2014). Swearing in political discourse: why vulgarity works. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 33, 537–547. doi: 10.1177/0261927X14533198

DeFrank, M., and Kahlbaugh, P. (2019). Language choice matters: when profanity affects how people are judged. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 38, 126–141. doi: 10.1177/0261927X18758143

Donahoo, S. A., Pfeifer, V., and Lai, V. T. (2022). Cursed concepts: new insights on combinatorial processing from ERP correlates of swearing in context. Brain Lang. 226:105079. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2022.105079

Frisby, B. N., and Sidelinger, R. J. (2013). Violating students expectations: Student disclosures and student reactions in the college classroom. Commun. Stud. 64, 241–258. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2012.755636

Generous, M. A., and Houser, M. L. (2019). “Oh, S**t! Did i just swear in class?”: using emotional response theory to understand the role of instructor swearing in the college classroom. Commun. Q. 67, 178–198. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2019.1573200

Generous, M. A., Houser, M. L., and Frei, S. S. (2015). ‘Exploring students' emotional responses to instructor swearing. Commun. Res. Rep. 32, 216–224. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2015.1052901

Guvendir, E. (2015). Why are males inclined to use strong swear words more than females? An evolutionary explanation based on male intergroup aggressiveness. Lang. Sci. 50, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.langsci.2015.02.003

Hamilton, M., Hunter, J., and Burgoon, M. (1990). An empirical investigation of an axiomatic model of the effect of language intensity on attitude change. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 9, 235–255. doi: 10.1177/0261927X9094002

Jay, T., and Janschewitz, K. (2008). The pragmatics of swearing. J. Politeness Res. 4, 267–288. doi: 10.1515/JPLR.2008.013

Jay, T. B., Caldwell-Harris, C., and King, K. (2008). Recalling taboo and non-taboo words. Am. J. Psychol. 121, 83–103. doi: 10.2307/20445445

Johnson, D. I., and Lewis, N. (2010). Perceptions of swearing in the work setting: an expectancy violations theory perspective. Commun. Rep. 23, 106–118. doi: 10.1080/08934215.2010.511401

Kwon, K. H., and Cho, D. (2017). Swearing effects on citizen-to-citizen commenting online: a large-scale exploration of political versus nonpolitical online new sites. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 35, 84–102. doi: 10.1177/0894439315602664

Lafreniere, K. C., Moore, S. G., and Fisher, R. J. (2022). The power of profanity: the meaning and impact of swear words in word of mouth. J. Mark. Res. 59, 908–925. doi: 10.1177/00222437221078606

Lazarides, R., Buchholz, J., and Rubach, C. (2018). Teacher enthusiasm and self-efficacy, student-perceived mastery goal orientation, and student motivation in mathematics classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 69, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.017

Le, M. (2012). The use of anonymous pop-quizzes (APQs) as a tool to reinforce learning. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 100, 316–319. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.100.4.017

Love, R. (2021). Swearing in informal spoken English: 1990s-2010s. Text Talk. 41, 739–762. doi: 10.1515/text-2020-0051

MacKay, D. G., Shafto, M., Taylor, J. K., Marian, D. E., Abrams, L., Dyer, J. R., et al. (2004). Relations between emotion, memory, and attention: evidence from taboo Stroop, lexical decision, and immediate memory tasks. Mem. Cognit. 32, 474–488. doi: 10.3758/BF03195840

Mullins, E. (2020). Watch Your Mouth: Swearing and Credibility in the Classroom (Master's Theses). Wichita State University, Wichita, KS, United States.

Rasmussen, K. (2008). “Halo Effect,” in Encyclopedia of Educational Psychology (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc).

Sidelinger, R., Nyeste, M., Madlock, P., Pollak, J., and Wilkinson, J. (2015). Instructor privacy management in the classroom: exploring instructors' ineffective communication and student communication satisfaction. Commun. Stud. 66, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2015.1034875

Stapleton, K. (2020). Swearing and perceptions of the speaker: a discursive approach. J. Pragmat. 170, 381–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.001

Stapleton, K., and Beers Fägersten, K. (2023). Editorial: swearing and interpersonal pragmatics. J. Pragmat. 218, 147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2023.10.009

Stapleton, K., Fägersten, K. B. R., and Loveday, C. (2022). The power of swearing: what we know and what we don't'. Lingua 277:103406. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103406

Stephens, R., and Umland, C. (2011). Swearing as a response to pain: effect of daily swearing frequency. J. Pain 12, 1274–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.09.004

Sulpizio, S., Toti, M., Del Maschio, N., Costa, A., Fedeli, D., Job, R., et al. (2019). Are you really cursing? Neural processing of taboo words in native and foreign language. Brain Lang. 194, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2019.05.003

Keywords: swearing, higher education, perception, recall, learning

Citation: Washmuth NB, Stapleton K, Ballmann CG and Caulkins RM (2025) Effects of professor swearing on learning and perceptions: a pilot field study. Front. Educ. 10:1451584. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1451584

Received: 19 June 2024; Accepted: 01 April 2025;

Published: 17 April 2025.

Edited by:

Zachary J. Domire, East Carolina University, United StatesReviewed by:

Zhuoying Wang, The University of Texas at Austin, United StatesMarissa Bello, Middle Tennessee State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Washmuth, Stapleton, Ballmann and Caulkins. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicholas B. Washmuth, bncwMDc3QHVhaC5lZHU=

Nicholas B. Washmuth

Nicholas B. Washmuth Karyn Stapleton3

Karyn Stapleton3 Christopher G. Ballmann

Christopher G. Ballmann