- Prithivi Narayan Campus, Tribhuvan University, Pokhara, Nepal

Knowledge of vocabulary is an essential aspect of language development. Most of the non-English specialised students feel hesitation in communicating in English due to limited vocabulary. Effective vocabulary teaching and learning can be aided by multimodal glosses. In this rationale, this mixed methods participatory action research is intended to investigate the effect of multimodal glosses in improving the English vocabulary of non-English specilised EFL students in a public university in Nepal. The study was conducted in a three-month intervention experiment for an intact class of 60 non-English specilised undergraduates. The data were collected from tests (pre-test, progress-test, and post-test), and interviews. The data were analysed using quantitative statistics (mean, standard deviation, and T-test), and the data from the unstructured interview were analysed descriptively. The overall results revealed that the use of multimodal glosses led to significant improvements in students’ English vocabulary and its use. The findings suggest that the study’s intervention, the use of multimodal glosses, was effective in improving non-English specialised undergraduates’ ability to develop, comprehend, and use English vocabulary. Thus, students and teachers are to be aware of using multimodal glosses contextually to increase, understand, and adopt English vocabulary appropriately.

Introduction

Vocabulary refers to the words of a language that include a single item, phrase, or group of several words that have a specific meaning. Vocabulary includes not only all the words in a language but also the way words collocate into lexical phrases or chunks. Vocabularies are taken as the basic units of language, and effective communication is not possible without knowledge and understanding of the words used in the language. Getting mastery over vocabulary is crucial for everyone who wishes to learn a language. Vocabulary is an essential aspect for developing competence and performance along with the process of language development (Harmon et al., 2009; Cummings et al., 2018; Yokubjonova, 2020). Language learning without an ample repertoire of vocabulary is impossible. The learners who are learning English as their foreign (EFL) or additional language (EAL) are often struggling with vocabulary. The students who pursue their academic career in EFL or EAL contexts, begin English language learning with a lower level of vocabulary, so they are in need of struggle in learning language (NALDIC, 2015; Brooks et al., 2021). Due to a limited vocabulary repertoire, EFL and EAL require more time and effort to learn English.

Knowledge of vocabulary does not mean only understanding the meaning of the words; it also includes the way of getting mastery over language skills, literary genres, and language aspects. Polok and Starowicz (2022) argue that learning a foreign language is impossible without a sound command of the majority of its words. Learning a foreign language’s vocabulary is one of the most important aspects of language competence for enhancing learners’ overall linguistic growth and development (Katemba, 2022). In the same context, research shows that an EFL learner should know 98 percent of their vocabulary with its contextual use and meaning to get mastery over the language (Schmitt et al., 2001). Thus, vocabulary is regarded as the heart of language, without which it is impossible to imagine the existence of language.

As an educator and English language instructor, I have experienced teaching English vocabulary as a great challenge for the learners who are learning English as a foreign or additional language in the universities of Nepal. The students are recommended several reading courses where they need to read, comprehend the text, and do the exercises. But they do not show their interest in reading those texts because of their limited ability to understand the vocabulary used in the texts. On the one hand, they have less knowledge of English vocabulary, and on the other hand, they do not understand the meaning of the lexemes used in the text. I remembered a day of my teaching in which I asked them to read a poem, “The Ballad of a Dead Friend,” composed by Edwin Arlington Robinson, find out the meaning of the various words, phrases, and lexical chunks used in the poem, and then use them in meaningful sentences. The murmur was, “hamilai sabdaharuko artha kehi audaina, sar le kaam gara bhane bhayo kasari garne ho” [We do not know the meaning of the words, sir told us to do it, but how to do it?]. Most of them did not do that because they did not find their meaning in the dictionaries they had. Most of the time, I teach them the texts translating such unfamiliar vocabulary into Nepali because they are hesitant to communicate in English due to a lack of lexical knowledge. While teaching them in English into Nepali, they do not get exposure to English, and at the same time, the objectives of the curriculum are not achieved on the one hand, and using Nepali cannot be the sole solution in multilingual classes.

Similar to my experiences, Al-Bukhari and Dewey (2023) state that it is a universal challenge for all English teachers to find effective, creative, and innovative ways of teaching vocabulary for EFl students. Moreover, a lack of one to one correspondence between spelling, pronunciation, and word meaning and difficulty in pronunciation, idiomatic expressions make teaching English vocabulary to EFL learners more difficult (Astatia, 2019). Moreover, as my experiences, Sari and Wardani (2019) also felt that lexical problems affected students’ communication in English. All these accounts, students’ behaviours, and my experiences made me feel that students produce such expressions due to a lack of knowledge of appropriate understanding, choice, and use of English vocabulary, and that special techniques need to be applied for making them comfortable with learning English vocabulary and the language. Difficulties in teaching English vocabulary lead English teachers to some steps they can take to overcome the problem (Sari and Wardani, 2019). According to Das (2007), the English vocabulary proficiency of students in urban community schools is higher than that of students in rural community schools. Similar to this, Sijali (2016) also finds that students in community schools who were instructed in the grammar translation method had a lower level of English vocabulary than those who were instructed in the English language at institutional schools, though both types of students did not have the satisfactory level of proficiency required for effective communication in English. Dhungana (2011) finds that the students who were familiar with sense relation in English could have better knowledge to use vocabulary in the context. In this issue, Magar (2021) argues that Nepali students learning English could have less exposure to the English language, and as a result, they are unable to use the words in the context even if they know the words. All these accounts reveal that teachers are the change makers and can apply several strategies and techniques for making EFL students able to cope with English vocabulary and its contextual use. In this context, I believe multimodal glosses for teaching vocabulary can be one of the best techniques for EFL students in multilingual classes in Nepal.

Glossing helps for second language vocabulary learning and retention (Al-Seghayer, 2001; Ramezanali and Faez, 2019). Glossing is a useful technique in multilingual and multileveled classes for teaching EFL vocabulary. Glossing helps to avoid incorrect guessing, decrease dependency on dictionaries, promote learners’ autonomy in learning vocabulary, and help them learn with techniques that suit their levels and interests (Ko, 2012; Al-Seghayer, 2001). Glosses can be in different forms and formats. Research shows that multimedia, multiple choice, glossary, text, video, audio, definition, example, picture, etc. are the forms of glosses that can be used in unimodal (only one) or multimodal (combination of two or more) for teaching vocabulary (Al-Seghayer, 2001; Boers et al., 2017a; Yanagisawa et al., 2020; Yeh and Wang, 2003). Glosses are often used to teach unfamiliar and difficult words, which enable the students to comprehend the EFL words and texts without interruption and limit the use of a dictionary. Studies claim that Multimodal glosses are more useful for promoting learners’ vocabulary knowledge (Ouyang et al., 2020; Ramezanali and Faez, 2019). However, Lin and Tseng (2012) concede in their research that glosses in texts and videos are more useful for teaching unfamiliar words in a second language. Moreover, multimodal glosses of pictures, videos, and gestures are more effective and successful in learning second language vocabulary (Andrä et al., 2020; Morett, 2019). In her research, Rassaei (2017) insists that the students who were exposed to audio glosses achieved a higher degree of vocabulary than those who were exposed only to textual glosses. In university education of Nepal, English is taught as a compulsory subject with the aim of developing communicative ability of the students though they are not majoring in English. In the same vein, Rai (2019) concludes that vocabulary learning can be enhanced by using YouTube videos though the students face problems in understanding pronunciation and comprehending the texts. But teaching vocabulary is not given special and separate space in the curricula and textbooks (Sijali, 2016); instead, it is integrated within reading texts and very limited words are given as the glossary in each text where, students are expected to learn vocabulary from the text itself. So, both teachers and students are not eager to put particular attention towards them, even though vocabulary is the basic foundation for developing language skills, aspects, literary genres, and language competency, which leads to limited knowledge in the English language and makes students feel difficulty communicating in English. In this context, the purpose of the research is to explore the effect of glosses on developing EFL students’ English vocabulary in public universities in Nepal.

Theoretical framework

In this research, I investigated the role of glosses for teaching English vocabulary in the context of a public university in Nepal, where English-learning students are expected to communicate in the language expertly, efficiently, effectively, and successfully without any hesitation. Along with demonstrating the application of glosses in classroom teaching, I confirm a prediction that multimodal glosses could be a better technique than unimodal glosses for building learners confidence in learning, understanding, and using English vocabulary. The Dual Coding Theory (DCT) introduced by Allan Paivo in 1971 focuses on the use of two codes (visual codes and verbal/symbolic codes) to facilitate the students encoding of the information effectively, successfully and enable them to retrieve it later in need of contextual use (Clark, 2021; Loveless, 2022; Jennifer et al., 2007). Ramezanali et al. (2021) suggest that the use of two modal glosses can be effective for teaching English vocabulary. In this study, I used a multimodal combination of text, picture, definition, audio, video, gesture, and example glosses in teaching English vocabulary for undergraduate non-English specialised students who are learning EFL for communication.

Research questions

i. To what extent does the use of multimodal glosses improve university students’ English vocabulary in the EFL context of Nepal?

ii. What do students perceive about the usefulness of multimodal glosses in improving their English vocabulary?

Research methodology

Collaborative Mixed Methods Participatory Action Research (CMMPAR) was the research design used in this study. The students’ inability to communicate effectively and meaningfully in English due to their limited knowledge and understanding of vocabulary was explored as a classroom problem, which I experienced during my teaching for non-English specialised students. CMMPAR is an effective design to provide a comprehensive assessment of the problem, make a solid and effective plan, and conduct rigorous evaluation of the intervention(s) for the improvement of the students through the integration of quantitative and qualitative data (Mills, 2011; Ivankova, 2015; Ivankova, 2017). The results of quantitative data provide a base for qualitative data to explore deeper information and an adequate solution to the problem. CMMPAR supports achieving the pragmatic and transformative goals of the research (Ivankova and Wongo, 2018; Shulha and Wilson, 2003). In this research, multimodal glosses were the interventions used to improve students’ English vocabulary. With my close attachment to the students as an English instructor, I experienced that most of the students mostly found it difficult to comprehend and use English words in the reading texts, which left them unable to interpret the text adequately. So, I used multimodal glosses and the students’ participation in several activities and exercises to improve their English vocabulary.

Participants

The participants in this study were 60 non-English-majoring first-year undergraduates in the faculty of education at a public university in Nepal. The participants were from different geographical locations and with different mother tongues. A test on vocabulary was taken to maintain the homogeneity of their English language proficiency prior to experimenting with intervention. An intact class consisting 60 non-English specialised students was selected, where they were obliged to take a compulsory English course for developing communicative skill. I was responsible for teaching them the English course. I taught them reading passages by making lesson plans, and in each lesson, they were taught vocabulary with multimodal glosses to understand the meaning of unfamiliar words and use them in the contexts. They were also exposed to the role of multimodal glosses in improving vocabulary power and their use. Each lesson lasted for 45 min and was split into two stages: building knowledge and putting it into context. During the first phase, I taught them texts explaining vocabulary with multimodal glosses and some exercises. In the second stage, I gave them different exercises from the text book prescribed for them, where they were asked to supply synonyms, antonyms, matches, locates, definitions, and uses of vocabularies. The exercises were based on the texts they learned, and they were encouraged to use the words in a meaningful context. In each lesson, the students were given 10 min to read the particular text and find out the unfamiliar words, and then the teacher took 15 min to describe the text and vocabulary using suitable multimodal glosses, engaging them in the vocabulary-related exercises given in the book, which were designed in the form of multiple-choice questions and finding word meaning. Then, for the last 20 min, they were engaged in post-reading activities that consisted of making sentences, matching, substitution, and giving synonyms and antonyms. The teacher worked with them as a participant, creating interaction and discussion among them in both stages. Each day in each lesson, they were given a homework assignment, which was checked the following day, and feedback was provided. Such activities continued for 3 months, six periods per week, that is, 72 days in total, reducing the number of Saturdays and public holidays.

Among the participants, six were from Brahmin and Chhetry, two were Newar, 11 were Gurung, nine were Magar, 13 were Tamang, and 19 were of Dalit ethnicities. Similarly, 30 of them spoke Nepali, 10 of them spoke Gurung, 11 of them spoke Tamang, five spoke Magar, one spoke Newari, and three spoke some other languages as their mother tongue. The age range of the participants was 19–25 years old, and 44 of them were from community-based schools, while only 16 were from institutional schools. 48 of them were female, and only 12 were male. Among 60 students, 10 were selected purposively for interview in order to explore their perceptions on the use and necessity of multimodal glosses in learning English vocabulary.

Tools and procedures

The tools used in this study were tests, observations, and interviews. The students took a pre-test before the intervention, a progress test in between the intervention, and a post-test at the end of the session. One hour was allocated for each test, and the tests included a set of matching (consists of 10 items), 10 multiple-choice items, one set of five words to supply synonyms, one set of five words to supply antonyms, one set of five words to use the words in sentences, five fill in the blanks, and one set of 10 words to construct a readable paragraph or story using the given words. Altogether, there were 50 questions worth 50 marks (Appendix A). The test was piloted among 20 students of the same level who were not participants in this study prior to the real administration. For the sake of validity and reliability of the test, I showed them to the three experienced professors of the university and got feedback from them. Based on the results of the piloting, and the feedback from the professors, the tests were finalised and administered. The pre-test, progress test, and post-test were selected from the reading texts of the book English for the New Millennium, a text book prescribed for the first-year undergraduates in the faculty of education at a public university in Nepal (Awasthi et al., 2015). The same set of test items was used in the pre, progress, and post tests for measuring the progress of the students and seeing the effect of the intervention. However, they were not informed that they were being tested on the same item because the order of presenting questions in each set was different. The pre-test was taken before the intervention to identify the students’ vocabulary power, and the post-test was taken after the use of multimodal glosses in teaching vocabulary for 3 months. Between the pre-test and post-test, one progress test was conducted to explore how effectively the intervention was functioning. All the scores of each test were recorded and analysed using simple statistical tools like mean and standard deviation. During the three-month treatment period, I worked together with the students engaging in the group work as a member, monitoring and facilitating them, and also observed their behaviour, which I recorded in a daily note. Then, I compared the results of the pre-test, progress tests, and post-test in order to find out the effect of multimodal glosses on improving students’ English vocabulary power. Then, to explore the students’ perceptions of the usefulness of multimodal glosses for improving their English vocabulary, I conducted semi- structured interviews with the selected participants. I asked them to share their feelings, experiences, and practises for understanding and using vocabulary with the use of multimodal glosses. The interviews were recorded, coded, categorised, thematized, and is analysed descriptively by myself. I Interpretated the results of experiments, observations, and interviews integrated them into the discussion. I have maintained the research ethics throughout the research process by giving adequate credit to the cited resources, maintaining unanimity among the participants, and using pseudonyms in the report.

Results

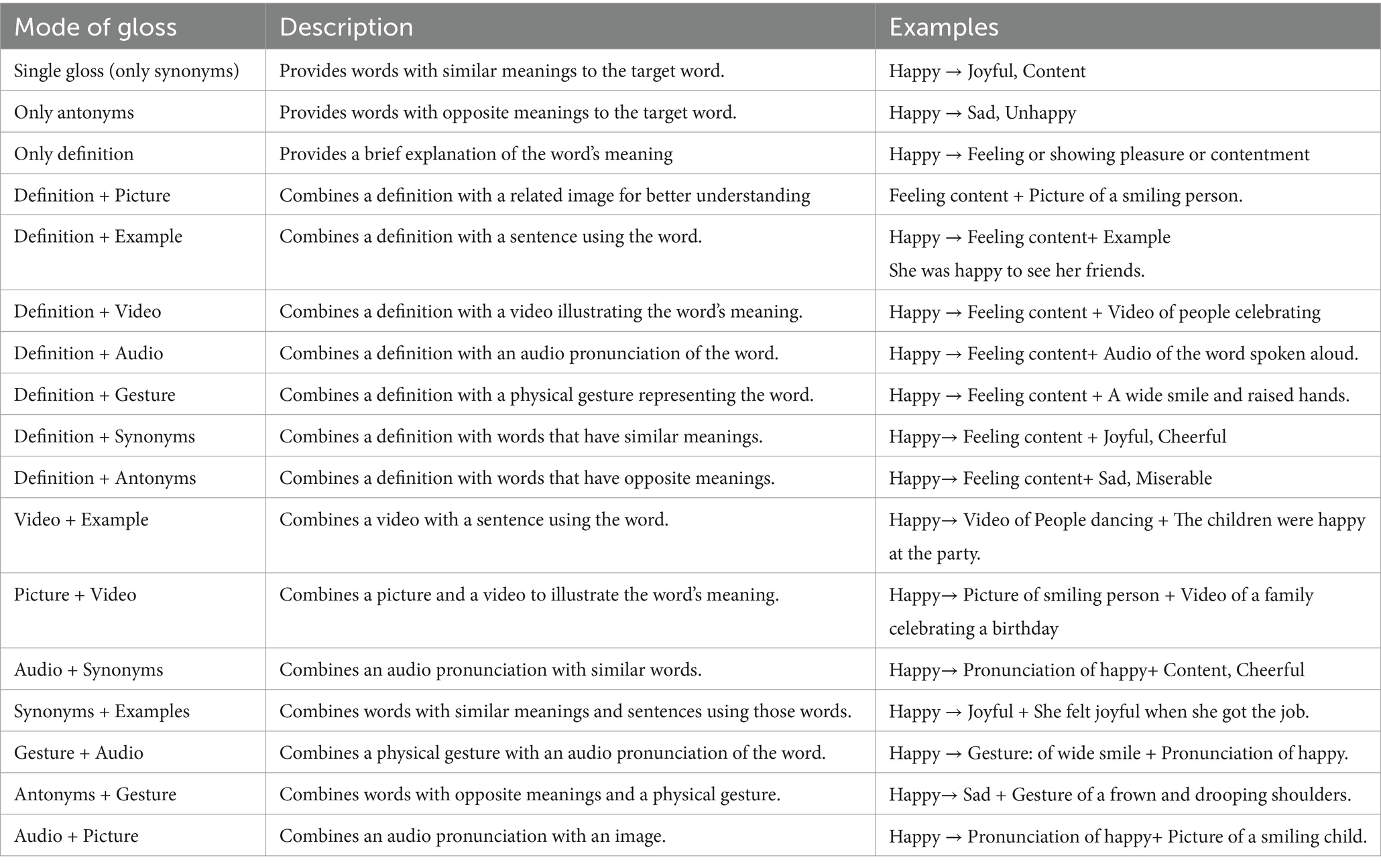

The results are presented as per the research questions: the use of multimodal glosses to improve students English vocabulary and the students’ opinions towards the usefulness of multimodal glosses for improving, comprehending, and using English vocabulary. The modes of glosses used in the study are presented in Table 1.

Use of multimodal glosses to improve university non-English major students’ English vocabulary

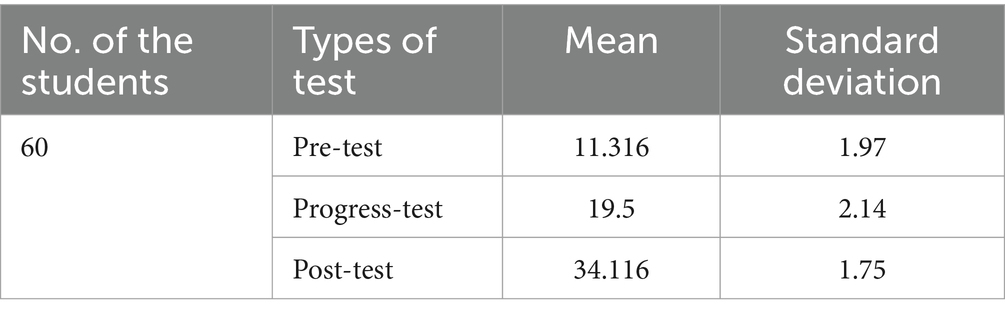

To examine the effect of multimodal glosses on improving the English vocabulary of non-English specialised students in an EFL context in higher education in Nepal, I taught the students six periods per week for 3 months, engaging them in various exercises and activities related to English vocabulary and training them to use the learned words in the context for effective and successful communication. I investigated the students’ vocabulary power by counting the correct responses out of 50 questions in seven different categories: multiple choice (10), giving synonyms (5), giving antonyms (5), making meaningful sentences using the words given (5), writing a paragraph using the given words (10), matching (10), and filling in the blanks (5) (Appendix A). The distribution of the marks is uneven to establish the validity of the content of the test. To gauge the effect of the intervention, two measurements were taken. First, I calculated the mean scores of the pretest, progress test, and posttest and compared. Second, the mean scores and standard deviations of the pretest and posttest were treated by using the paired sample T test. The results of the pretest, progress test, and posttest are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 indicates the significant increase in the average score of university level non-major students in English vocabulary. In the pre-test, the mean score for the students’ achievement was 11.316 (Appendix B). After one and a half months of using multimodal glosses in teaching vocabulary, students’ engagement and active participation on various exercises and activities increased the mean score to 19.5 in the progress test (Appendix C). The raised mean score indicates the gradual improvement in English vocabulary. Similarly, with a three-month long experiment of intervention, the mean score reached 34.116 in the post-test (Appendix D), which was almost three times greater than the score of the pretest. Besides, the standard deviation of the score in posttest (1.75) is lower than the score in the progress test (2.14) and pretest (1.97) (Appendix D). Such variation in standard deviation implies that the use of multimodal glosses in English vocabulary teaching and learning not only assisted in improving vocabulary power but also helped reduce the gap in learning vocabulary among them. The standard deviation in the progress test is higher than in the pre-test, which indicates that though the mean score is higher, in the initial days of using multimodal glosses, academically advanced students benefitted more than those of poorer backgrounds. However, the frequent use of intervention decreased such individual gaps among the individuals, as reflected in the posttest results. A paired sample t-test was used for the comparative analysis of the results of the pretest and posttest, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the comparative analysis of the results of the pretest and posttest is 13.37, and calculating the p-value with the degree of freedom, the p-value is 0.00, which is less than the significant level of 0.05 (Appendix E). A p-value less than the significant level α = 0.05 implies that the use of multimodal glosses in teaching vocabulary to improve students English vocabulary did have a positive effect.

Students’ experiences towards the usefulness and necessity of multimodal glosses for improving English vocabulary

The knowledge and development of English vocabulary is an essential phenomenon for effective communication and the development of language skills and other aspects of the English language. The students were engaged in reading the texts, which were explained with glosses, and assigned various activities and exercises for 3 months. The vocabulary used in the texts was taught using a contextual and need-based combination of pictures, definitions, audios, videos, gestures, and examples. The students were passionate about learning English vocabulary for effective communication. In an observation, I found them to be shy and hesitant to take part in the activities in the initial days. Academically good students were observed as being more active than those who were poor and wished to escape from the tasks. As shown in the results of the progress test, the academically good students used to take part in each activity and respond more quickly than the others. As shown in the results of the pretest and posttest, the students during the interview also expressed that they saw a significant improvement in their English vocabulary with their engagement in learning with multimodal glosses. After the pretest, when they were engaged in vocabulary learning exercises like giving synonyms, naming the pictures, giving antonyms, matching, and so on, most of them felt difficulty doing them. They were observed talking to each other in Nepali as follows:

Afuharulai sabaibhanda gahro angrejika shabdaharu sikna ho. Jati gare pani, jati padhe pani, kahi bujhidaina; bujhe pani, tyo shabda prayog garna nai audaina. Yo sarle pahile pahile ta note lekhauthyo; tyahi ghoke hunthyo ra parikshya pass vainthyo. Khai ali din bho ajabholi ta shabda sikauna hamilai nai sabai kaam garna lagauchha, afu pani sangai baschha, vocabulary sambandhi yati kaam ra exercise dinchha kasri garne ho. Eso google search handiu bhane sarnai yahi hunchha sangai kam garera baschha. [The most difficult aspect of learning English for us is learning English words. No matter how much we do or how much we read, we do not understand, and even if we did, we would not be able to use that word. This teacher used to provide notes before, we used to rote them and pass the exam, but these days, to make us learn the words, he makes us do all the work. He sits and works with us. He gives us so much work and exercise on vocabulary; how do we do it? If we do a google search, teacher live together and work with us].

They further murmured as “pahile pahile ta nepali mai bhaninthyo shabda ko artha, ahile ta chitra, video, aDio, udaharaN dinchha sarale tara pani khai bujhnai gahro bhayo. Yasari padhdaa: Sikine ho ki pariksha mai fel bhaine ho.” [Before, the meaning of the words used to be said in Nepali, but now the teacher teaches with pictures, videos, and audio examples; however, it is difficult to understand. If we study this way, we will either learn English or fail the exam].

Evenly, when they were exposed to several activities and exercises on vocabulary and taught the texts and words with multimodal glosses, their motivation for learning vocabulary increased. Their voluntary involvement in the activities had been increased. Students who previously struggled academically and sought to avoid assignments have now become more engaged, actively participating and demonstrating improved responsiveness to the exercises. They changed their voices and droned after about 3 weeks of learning words with the glosses:

Sachchai sanai klas bata English word haru yastai tarikale padhaeko padheko bhae ta English bolna lekhna ta kharra hune rahechha ni. Ahile yo ek mahina ta kati sikiyo kati. Majja pani achha. Sabda jane ta sentence ta latarpatar parihalinchha ni bolada, lekhda ta. Yo sarle purai barsa yahi tarikale sikaune hola ki bichama gaera uhi puranai tarika prayog garla. Yahi tarika le padhaunus bhanera karaunu parchha. [If we had read those English words and were taught in the same way from the very first class, then we would be able to speak and write English easily. We have learned so much in this one month. It's also fun. If we know the words, the sentence is not a big challenge when speaking or writing. This teacher will teach the same way for the whole year or will go to the middle and use the same old method. We should request him to do so in this way].

During the interviews, all the students agreed that they had made significant improvements in their English vocabulary over the three-month period and could communicate in English, though it might not be a perfect language. Sharing her experience, one of the participants, Smriti, expressed:

The use of various glosses really helped us improve our English vocabulary. I had never learned or been taught words in this way. The use of pictures, videos, audios, and examples helped me understand and use English vocabulary in communication, even though I am not specialised in the language.

In the same vein, another student, Aditya, added, “I love learning vocabulary with videos and pictures that make my learning sustainable.” Karuna, another student, recalled her past days and shared:

I took a test three months ago that required me to read the passage and provide synonyms, antonyms, and single words to the given definition, but I could not do that because I did not understand the text itself. When my teacher began to ask questions in English, I tried to escape. But now, after I was taught vocabulary with glosses, my confidence increased, and I can take the risk of speaking and writing in English. The knowledge of vocabulary helps one comprehend the message and respond accordingly.

She emphasised that anyone who wishes to communicate in English should have a large vocabulary. Many of the students realised that they were afraid of using English due to their poor vocabulary. They had difficulty understanding the meaning of words, their choices, collocation, and contextual use. In this context, Sandesh conceded, “Learning vocabulary with glosses helps us understand how particular words are used in real-life contexts.” Glosses became not only the means for learning words from the text but also taught them how to be used in context. Ashok, another student, shared, “During these 3 months, I learned vocabulary in funny and entertaining ways. The use of gestures, pictures, videos, and audios not only gave me the meaning and contextual use of the words, but also taught me their pronunciation and intonation pattern.” The students expressed that the main cause of their unwillingness to learn was anxiety that increased with unfamiliar words. One of the participants, Padma, shared as follows:

When I was exposed to unfamiliar words in any text, my anxiety reached a high point, and I could not dare to read and learn. But learning vocabulary through pictures, videos, examples, gestures, definitions, etc. reduced my anxiety, and I learned vocabulary with relaxation and fun.

The students also agreed that multimodal glosses enhanced their motivation level and willingness to learn vocabulary. These accounts reveal that glosses are motivating and interesting for increasing students’ participation in classroom learning and making the learners knowledgeable about the words, their use, pronunciation, and meaning, which helps them comprehend and interpret the texts and messages appropriately. Let us observe some of the pieces of conversation from the interview with the students.

Researcher (me): My first question is; How do you feel about learning vocabulary with glosses for 3 months?

Sandesh: In fact, I have learned the way of learning and teaching the vocabulary of not only English but also of any other second language. The way you engaged us in the activities and exercises was really marvellous. As a result, we saw a significant improvement in our English vocabulary. We experienced such types of learning strategies where learners and teachers work together, watch and listen together, and the teacher teaches the students in a lively manner using pictures, videos, examples, and so on. I really enjoyed it and learned a lot.

Researcher (me): Have you improved your vocabulary and communication skills in this short period of time?

Smriti: Of course, in the initial days, I was unable to understand the English words used in the texts, so I felt hesitant to communicate in English. But this three-month period changed my behaviour. Now I do not feel any hesitancy to communicate in English because I have developed a good repertoire of English words and have the confidence to use them, though my communication may not be perfect but comprehensible.

Researcher (me): How do you think the vocabulary teaching with glosses contributed to your performance in understanding English vocabulary and their use for communication and comprehending English texts?

Shova: Thank you, sir, for the question. The glosses, the activities, and the exercises you engaged us in made the classroom learning lively and interesting. We enjoyed the activities a lot and learned vocabulary and its use naturally and without much effort. We realised that we were playing with pictures, videos, audio, your gestures, and examples, but ultimately we achieved word power. Now we can communicate in English and understand the texts comfortably because we have word power. We are grateful to you and your efforts for enlightening us on the effective way of learning vocabulary.

Researcher: How did such an improvement in your vocabulary power happen?

Prajwal: Here, we both play and read, and in the regular English reading text, we attended the lessons regularly and actively, and you participated in the activities along with us. Then, we were comfortable and confident. We enjoyed the words with two to three glosses. When we feel uncomfortable learning from one, we use the next, which has been a boon for us.

All the accounts received from the tests, the students’ regular observations as teachers, and the responses from the interviews reveal that all the students agreed that the vocabulary teaching activities in which they engaged with using glosses were effective. They assert that they had feared communicating in English in the past but now do so without any hesitation. They could understand, use, and communicate in English and comprehend the texts.

Discussion

The research intended to investigate the effect of multimodal glosses for improving the English vocabulary of non-English specialised undergraduates in higher education in Nepal. The results from the pretest, progress test, and posttest show that multimodal glosses have a positive effect on improving English vocabulary. A similar effect was found in the previous research (Ramezanali and Faez, 2019; Ouyang et al., 2020). The solid and adequate use of multimodal glosses improves EFL non-English specialised undergraduates’ English vocabularies, their understanding, and contextual use for communication and comprehension of the texts. The mean scores of the students’ vocabulary achievement increased from 11.316 to 19.5 to 34.116, and the standard deviation ranged from 1.97 to 2.14 to 1.75 in the pretest, progress test, and posttest, respectively. The increased ratio of the average score and the decreased ratio of the standard deviation in the test results show the affirmative effectiveness of multimodal glosses in developing English vocabulary. The students’ improvement in vocabulary learning (in the posttest) is better when they are exposed to multimodal glosses than when they are exposed to single or no gloss (results in the pretest). The finding is in line with the dual code theory that claims learning vocabulary becomes effective while learning with visual and verbal/symbolic modes (Clark, 2021; Loveless, 2022; Jennifer et al., 2007; Ramezanali et al., 2021) and assimilates with the findings of the previous researches, which conclude that dual or multimodal glosses could be more effective for learning second or foreign language vocabulary than single gloss mode (Rassaei, 2017; Wang and Lee, 2021) However, the finding contrasts with Boers et al. (2017b), who claim that textual and pictorial glosses are no more effective for learning and retaining vocabulary than textual explanations. Similar to this and in contrast with my research finding, Akbulut (2007) argues that there are no significant differences in learning vocabulary with single gloss or multimodal glosses. The results show an increased ratio of standard deviation in the progress test than in the pre-test, which implies that the initial phase of the intervention experiment was confusing and difficult for the students, and as a result, only the academically sound ones get more benefits than those on average. This finding corroborates with my own experience and the research findings, which claimed that difficulties and confusion faced at the initial phase are difficult to detect, manage, and respond to, but they enable the learners to develop cognitive strategies for learning (Lodge et al., 2018).

In the interview, the students expressed that they have made a significant improvement in their English vocabulary. The use of multimodal glosses made them able to understand the texts and communicate in English, which implies that learning through glosses promotes vocabulary uptake from reading (Boers et al., 2017a). The changed level of learner motivation from unwillingness to strong willingness reveals that they found learning English vocabulary with multiple glosses interesting, engaging, and effective. The finding is in line with the claims that the combination of visual and oral modes could be useful for learners’ vocabulary retention (Al-Seghayer, 2001; Farley et al., 2012; Ramezanali and Faez, 2019; Yanguas, 2009). The increased level of the learners’ confidence and comprehension enable them to interpret the texts adequately and communicate in English appropriately, which assimilates with the research that claims that level of comprehension plays a significant role in the understanding of reading texts and communicative ability of the students. Learners who have a free and relaxing mind learn better than those who have a stressful mind (Srisang and Everatt, 2021; Shiotsu and Weir, 2007). The use of multimodal glosses in vocabulary learning has created a learner friendly environment where they could learn with fun, reducing their level of anxiety. A lower level of anxiety makes for high motivation and better comprehension, which leads to effective language use. The level of vocabulary knowledge determines the learners’ ability to organise and use their words for learning other aspects and skills of language. As the students claim that they could understand English text and communicate on it comfortably, they exhibit the affirmative impact of glosses in their learning English vocabulary in the EFL context of Nepal. Similar to this finding, Al-Bukhari and Dewey (2023) found positive effects of multimodal glosses for improving recognition and recall of Arabic vocabulary. A solid knowledge of vocabulary is the foundation for developing proper command over language. The use of multimodal glosses supports the learners learning in a lively and interesting manner so that they learn not only the meaning of the words, but also the appropriate use of them in the context.

Conclusion and implications

This research intended to investigate the role of multimodal glosses in teaching English vocabulary to EFL non- English specialised undergraduates in a public university in Nepal using mixed methods participatory action research. After 3 months of intensive practise and engagement in understanding the meaning of the words and their contextual uses using multimodal glosses, the students’ English vocabulary has been significantly improved. The increased ratio of the mean score in pre-to-post tests, their observed behaviour, and the students’ own experiences demonstrate that they are greatly motivated towards learning English vocabulary and using it in communication. All the students expressed that using multimodal glosses plays a pivotal role in improving their English vocabularies and using them in context appropriately. The students wish to learn English vocabulary with glosses rather than only textual explanation. Vocabulary teaching needs to be taken into consideration for enhancing students’ overall proficiency and competency in the language. English language curricula, the text book, and teachers are expected to have special focus and space on vocabulary for students’ better language learning. The students’ attraction to learning with glosses reveals that they have realised the crucial role of knowledge of vocabulary for language development, and they are expecting appropriate strategies and techniques for better learning of English vocabulary.

The findings of this study are cogent for raising awareness about the value of vocabulary in developing competence in language aspects, skills, and communicative abilities. Moreover, it is valued for raising students’ and teachers’ awareness of the importance of instructing English vocabulary through multimodal glosses in EFL contexts for better student comprehension. Beyond the regular classroom instruction, various workshops, meetings, and conferences on vocabulary learning can be conducted to expose the students to English vocabularies and their use. Vocabulary teaching can be incorporated into the English language curricula and textbooks, with a special focus on the evaluation system too. This research was conducted in a single classroom of a public university in Nepal, thus, it can be replicated for more classes in different contexts and universities, and a comparative study can be made using the same intervention on the same issue using either the same research design or a different one. The major problem with developing English vocabulary in EFL contexts like Nepal is the lack of students’ reading habits and authentic resources for learning English. Thus, the concerned authorities can establish reading clubs, reading centres, reading materials banks, and so on, and encourage the students to engage in reading activities. The research’s conclusions suggest classroom strategies and curricular policies that curriculum designers, policymakers, teachers, and students can consider to enhance EFL students’ English vocabulary and improve their ability to speak and understand the English language.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Centre for Research and Innovation, Prithvi Narayan Campus, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1443803/full#supplementary-material

References

Akbulut, Y. (2007). Effects of multimedia annotations on incidental vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of advanced learners of English as a foreign language. Instr. Sci. 35, 499–517. doi: 10.1007/s11251-007-9016-7

Al-Bukhari, J., and Dewey, J. A. (2023). Multimodal glosses enhance learning of Arabic vocabulary. Lang. Learn. Technol. 27, 1–24.

Al-Seghayer, K. (2001). The effect of multimedia annotation modes on L2 vocabulary acquisition: a comparative study. Lang. Learn. Technol. 5, 202–232. doi: 10125/25117

Andrä, C., Mathias, B., Schwager, A., Macedonia, M., and von Kriegstein, K. (2020). Learning foreign language vocabulary with gestures and pictures enhances vocabulary memory for several months post-learning in eight-year-old school children. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 32, 815–850. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09527-z

Astatia, S. (2019). Teachers’ difficulties in teaching vocabulary at SMP Negeri 2 Jatibarang Brebes [unpublished masters’ thesis]. Semarang: Faculty of Languages and Arts, Universitas Negeri Semarang.

Awasthi, J. R., Bhattarai, G. R., and Rai, V. S. (2015). English for the new millennium. Kathmandu: Ekta Books.

Boers, F., Warren, P., Grimshaw, G., and Siyanova-Chanturia, A. (2017a). On the benefits of multimodal annotations for vocabulary uptake from reading. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 30, 709–725. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2017.1356335

Boers, F., Warren, P., He, L., and Deconinck, J. (2017b). Does adding pictures to glosses enhance vocabulary uptake from reading? System 66, 113–129. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.03.017

Brooks, G., Clenton, J., and Fraser, S. (2021). Exploring the importance of vocabulary for English as an additional language learners’ reading comprehension. Stu. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 11, 351–376. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.3.3

Clark, M. (2021). What t is dual coding theory and how can it help teaching? Available at: https://www.century.tech/news/what-is-dual-coding-theory-and-how-can-it-help-teaching/#:~:text=Dual%20coding%20is%20the%20idea,used%20are%20visual%20and%20verbal (Accessed February 12, 2024).

Cummings, A. G., Piper, R. E., and Pittman, R. T. (2018). The importance of teaching vocabulary: the whys and hows. Read Online J. Liter. Educ. 4:6.

Das, D. K. (2007). A study on English vocabulary achievement of grade four iv students [unpublished M. Ed. Thesis]. Kirtipur: Tribhuvan University.

Dhungana, S. (2011). Teaching vocabulary through sense relations [unpublished M. Ed. Thesis]. Kirtipur: Tribhuvan University.

Farley, A. P., Ramonda, K., and Liu, X. (2012). The concreteness effect and the bilingual lexicon: the impact of visual stimuli attachment on meaning recall of abstract L2 words. Lang. Teach. Res. 16, 449–466. doi: 10.1177/1362168812436910

Harmon, J. M., Wood, K. D., and Keser, K. (2009). Promoting vocabulary learning with interactive word wall. Middle Sch. J. 40, 58–63. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2009.11495588

Ivankova, N. V. (2015). Mixed methods applications in action research: From methods to community action. London: Sage.

Ivankova, N. V. (2017). Applying mixed methods in community-based action research: a framework for engaging stakeholders with research as means for promoting patient-centeredness. J. Nurs. Res. 22, 282–294. doi: 10.1177/1744987117699655

Ivankova, N., and Wingo, N. (2018). Applying mixed methods in action research: Methodological potentials and advantages. American Behavioral Scientist (Reprints and permissions), 1–20. doi: 10.1177/0002764218772673

Jennifer, M., Suh, J. M., and Moyer-Packenham, P. S. (2007). “The application of dual coding theory in multi-representational virtual mathematics environments” in Proceedings of the 31st conference of the International Group for the Psychology of mathematics education. eds. J. H. Woo, H. C. Lew, K. S. Park, and D. Y. Seo (PME: Seoul), 209–216.

Katemba, C. V. (2022). Vocabulary enhancement through multimedia learning among grade 7th EFL students. MEXTESOL J. 46, 1–13. doi: 10.61871/mj.v46n1-8

Ko, M. H. (2012). Glossing and second language vocabulary learning. TESOL Q. 46, 56–79. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3

Lin, C., and Tseng, Y. (2012). Videos and animations for vocabulary learning: a study on difficult words. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 11, 346–355.

Lodge, J. M., Kennedy, G., Lockyer, L., Arguel, A., and Pachman, M. (2018). Understanding difficulties and resulting confusion in learning: an integrative review. Front. Educ. 3:49. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00049

Loveless, B. (2022). Dual coding theory: the complete guide for teachers. Available at: https://www.educationcorner.com/dual-coding-theory/ (Accessed January 12, 2023).

Magar, S. (2021). Two good practices of teaching vocabulary: reflection of a teacher [blog article]. ELT CHOUTARI. Available at: https://eltchoutari.com/2021/01/two-good-practices-of-teaching-vocabulary-reflection-of-a-teacher/ (Accessed January 23, 2024).

Mills, G. E. (2011). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. 4th Edn. London: Pearson Education.

Morett, L. M. (2019). The power of an image: images, not glosses, enhance learning of concrete L2 words in beginning learners. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 48, 643–664. doi: 10.1007/s10936-018-9623-2

NALDIC (2015). EAL achievement: the latest information on how well EAL learners do in standardized assessments compared to all students. England: National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum. https://www.naldic.org.uk/research-and-information/eal-statistics/ealachievement/

Ouyang, J., Huang, L., and Jiang, J. (2020). The effects of glossing on incidental vocabulary learning during second language reading: based on an eye-tracking study. J. Res. Read. 43, 496–515. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12326

Polok, K., and Starowicz, K. (2022). The usefulness of various technological tools in enhancing vocabulary learning among FL polish learners of English. Open Access Libr. J. 9, 1–13. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1109283

Rai, B. K. (2019). Students’ perceptions on using you-tube videos in learning vocabulary. Kirtipur: Tribhuvan University.

Ramezanali, N., and Faez, F. (2019). Vocabulary learning and retention through multimedia glossing. Lang. Learn. Technol. 23, 105–124.

Ramezanali, N., Uchihara, T., and Faez, F. (2021). Efficacy of multimodal glossing on second language vocabulary learning: a meta-analysis. TESOL Q. 55, 105–133. doi: 10.1002/tesq.579

Rassaei, E. (2017). Computer-mediated textual and audio glosses, perceptual style, and L2 vocabulary learning. Lang. Teach. Res. 22, 657–675. doi: 10.1177/1362168817690183

Sari, S. N. W., and Wardani, N. A. K. (2019). Difficulties encountered by English teachers in teaching vocabularies. Res. Innov. Lang. Learn. 2, 183–195. doi: 10.33603/rill.v2i3.1301

Schmitt, N., Schmitt, D., and Clapham, C. (2001). Developing and exploring the behavior of two new versions of the vocabulary levels test. Lang. Test. 18, 55–88. doi: 10.1177/026553220101800103

Shiotsu, T., and Weir, C. (2007). The relative significance of syntactic knowledge and vocabulary breadth in the prediction of reading comprehension test performance. Lang. Test. 24, 99–128. doi: 10.1177/0265532207071513

Shulha, L. M., and Wilson, R. J. (2003). “Collaborative mixed methods research” in Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. eds. A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie (London: Sage), 639–669.

Sijali, K. K. (2016). English language proficiency level of higher secondary level students in Nepal. JAAR 3, 59–75.

Srisang, P., and Everatt, J. (2021). Lower and higher level comprehension skills of undergraduate EFL learners and their reading comprehension. LEARN J. Lang. Educ. Acq. Res. Netw. 14, 427–454.

Wang, S., and Lee, C. I. (2021). Multimedia gloss presentation: learners’ preference and the effects on EFL vocabulary learning and Reading comprehension. Frontier in. Psychology 11:602520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.602520

Yanagisawa, A., Webb, S., and Uchihara, T. (2020). How do different forms of glossing contribute to L2 vocabulary learning from reading? Studies in second language. Acquisition 42, 411–438. doi: 10.1017/S0272263119000688

Yanguas, I. (2009). Multimedia glosses and their effect on L2 text comprehension and vocabulary learning. Lang. Learn. Technol. 13, 48–67. doi: 10125/44180

Yeh, Y., and Wang, C. (2003). Effects of multimedia vocabulary annotations and learning styles on vocabulary learning. CALICO Journal, 21, 131–144. doi: 10.1558/cj.v21i1.131-144

Keywords: multimodal glosses, English vocabulary, EFL context, non-English specialised graduates, participatory action research

Citation: Paudel P (2025) Use of multimodal glosses in teaching English vocabulary for non-English specialised undergraduates in public university in Nepal. Front. Educ. 10:1443803. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1443803

Edited by:

Thomas Amundrud, Nara University of Education, JapanReviewed by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaHimdad Abdulqahhar Muhammad, Salahaddin University, Iraq

Copyright © 2025 Paudel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pitambar Paudel, cGl0YW1iYXJwQHBuY2FtcHVzLmVkdS5ucA==

Pitambar Paudel

Pitambar Paudel