94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 26 February 2025

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1437836

This study explored faculty perceptions of university-based transition services for students with intellectual disabilities (IDs) in Saudi Arabia, using a descriptive analytical approach with a sample of 153 members. Faculty demonstrated strong competencies in transitional programs, particularly in philosophical foundations, program evaluation, educational content, and behavior management. This study emphasizes the importance of specialized training in postsecondary knowledge, collaboration, and assessment for special education teachers. No significant gender differences in faculty competency awareness were noted. The findings underscore the need for continuous faculty development, integrated curricula, and collaborative planning to enhance transitional programs in Saudi special education departments. Tailored educational content, student involvement, and guidance toward meaningful postsecondary pathways are recommended, focusing on holistic development, including social skills and family engagement.

Defining the purpose of education remains a highly contested topic in the academic, political, and societal spheres (Marshall, 2017). However, as “education is central to the socialization of both individuals and society” (Marshall, 2017, p. 15), one may argue that the purpose of education is to prepare students to be contributing members of their society. A crucial period in the process of becoming a contributing member of society occurs after students leave high school, as they transition from school to community life (Rowe et al., 2015). In Saudi Arabia, expanding access to higher education, including for individuals with intellectual disabilities (IDs), is crucial for societal progress. This research explores faculty perceptions of university-based transition services for such students, acknowledging the transformative shift toward inclusivity in higher education. By the term “university-based transition services, we refer university-based transition services are programs, resources, and support systems that help students with IDs transition from secondary to postsecondary education or employment (Ghasemi et al., 2023). While many Saudi universities offer transition-focused courses, there remains a need to enhance these services. Transition-focused courses are course that are designed to prepare students with disabilities to move into a new environment (Chiba and Low, 2007). These courses aim to equip students with necessary skills for successful transitions, such as moving from high school to college or entering the workforce (Wehman et al., 2015). According to Landmark et al. (2010), these programs focus on developing students’ self-advocacy, social skills, time management, and other practical abilities essential for thriving in unfamiliar settings. The primary goal, as noted by Trainor et al. (2016), is to enhance students’ independence and readiness for post-secondary challenges. For the context of our study, such courses aim to equip individuals, especially those with IDs, for the transition from secondary education to post-secondary life. These courses typically cover a range of essential skills, including career exploration, self-advocacy, independent living, social communication, and academic preparation relevant to higher education or vocational training. They aim to bridge the gap between high school and adult life, addressing the unique challenges faced by individuals with IDs as they navigate this critical transition period (Almalki, 2022).

The growing body of literature on transition competencies investigates the necessary abilities and expertise that educators need to assist students with IDs in transitioning from high school to college, employment, and independent life (Landmark et al., 2010). The term Students with IDs is defined in the current study context as individuals who have been diagnosed with limitations in intellectual functioning (typically measured by an IQ score below a certain threshold) and who may require additional support and accommodations to succeed academically and socially in a university setting (National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, 2011).These competencies include understanding how to create effective transition plans, working well with students, families, and other support agencies, and using teaching strategies that prepare students for life after high school. They also involve assessing how ready students are for these transitions and ensuring that services are fair and inclusive. However, the lack of sufficient research on the effectiveness of educators’ training in delivering these transition services highlights the need for increased attention in this area (Almutairi, 2018). As noted by Trainor et al. (2016), the primary goal of these courses is to enhance students’ independence and readiness for post-secondary challenges, addressing the unique needs that arise during these pivotal life changes. While there is a growing body of literature on transition competencies, limited research focuses on the effective delivery of transition content in personnel preparation. Transition services play a vital role in helping individuals with IDs move from secondary school to higher education and beyond, as they often require personalized support for successful transitions with outcomes that have room for improvement compared to students with other disabilities (Almalky, 2018; Alnahdi, 2014; Alqraini, 2013).

The importance of transition services for students with IDs necessitates an examination of the perceptions and training needs of special education personnel. This evaluation is crucial to ensuring that preparation programs align with the actual requirements of transition service providers. Notably, prior research has revealed a significant correlation between faculty perceptions of service preparation and the frequency of service implementation and activity (Bouck and Flanagan, 2016; Wandry et al., 2008).

In accordance with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) (IDEA), transition services should be goal-oriented. These guidelines expect transition services to improve students’ academic and functional performance, fostering success and maximizing their autonomy beyond high school. Valuable insights from a range of disciplines are indispensable, including timely consultations with service organizations, postsecondary education programs, disability coordinators, employment organizations, adult day programs, and supported living organizations. These coordinated initiatives are essential to ensuring an effective transition plan and its resulting outcomes (Carter et al., 2016; Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2004; Skinner and Lindstrom, 2003).

However, Saudi Arabia has its own approach to supporting students with disabilities. While it may not have legislation identical to IDEA, Saudi Arabia has made significant strides in inclusive education through various policies and initiatives. For instance, the Kingdom has adopted inclusive education strategies in line with its Vision 2030 goals, which aim to create a more inclusive society, including people with disabilities. International practices often inspire the expansion of special education services and transition programs (Saudi Vision 2030). The framework in Saudi Arabia is still developing, and much of the support for students with disabilities is coordinated through the Ministry of Education and social welfare organizations (Almalki, 2022). There is increasing collaboration with international bodies and educational institutions to enhance transition services postsecondary support, and workforce integration for students with disabilities. In this context, Saudi Arabia is in the process of evolving its own system that aims to ensure effective transition and autonomy for students with disabilities, although its structure and legislative framework differ from those of the U.S. under IDEA (Alqraini, 2013).

In the United States, transition services prepare students for employment, independent living, or higher education (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2004). Three models exist for community and college settings: separate programs, mixed programs on college campuses, and inclusive and individualized services, all spanning the transition years from 18 to 21. Further research is needed to gauge the effectiveness of these models (Cimera et al., 2013, 2014; Wehmeyer et al., 2011). Understanding faculty perceptions of university-based transition services is crucial for assessing inclusivity in higher education, identifying the barriers, evaluating the support systems, and promoting the principles of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, contributing to Saudi Arabia’s educational excellence and leaving no one behind (Alothman, 2010; Ministry of Labor and Social Development of Saudi Arabia, 2017).

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in exploring the dynamics of faculty perceptions regarding university-based transition services for students with IDs (Alhossan and Trainor, 2015). The increasing role of technology, including artificial intelligence, in facilitating learning experiences for people with disabilities and a broader global shift toward inclusive education are the driving forces behind this interest. Faculty members play a central role in shaping the educational environment, and their perceptions can significantly influence the outcomes of students with IDs (Alhossan and Trainor, 2015).

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a significant step was taken in 2005 to introduce transition services specifically designed for high school students with IDs. In Saudi Arabia, several educational opportunities exist for students with IDs. A multitude of students with IDs either enroll in institutes or conventional schools. In institutional settings, students with IDs get training in designated classrooms customized to their needs and challenges. An alternate educational option for persons with disabilities is their participation in a mainstream program. Mainstream programs in Saudi Arabia are curricula created by students with IDs, conducted in regular public schools rather than specialized institutions (Alqraini, 2013). This initiative was aimed at facilitating a smoother transition for these students from school to further education, work, or other post-school activities. Consequently, students who completed high school before this pivotal year of 2005 were not afforded the advantages of these services. They transitioned to their post-school lives without the targeted support that later cohorts would receive. Over the subsequent 15 years following this introduction, various research endeavors aimed to evaluate and understand the efficacy and scope of these transition services. One of the most recurring concerns highlighted in these investigations was the apparent lack of adequate support. This deficit was not just in terms of resources but also in administrative backing, which is crucial for the sustained and impactful delivery of such services (Almutairi, 2018; Alnahdi, 2014; Alqraini, 2013).

Another significant area of concern arising from these studies was the relationship between schools and families (Almalki, 2022). Effective transition services are often a collaborative effort between educational institutions and families, ensuring that students receive consistent support both in school and at home. The role of families in reinforcing and complementing the transition strategies initiated at schools cannot be understated, making this a critical area of focus.

The outcomes for individuals with IDs in Saudi Arabia are considered poor (Almalky, 2018), indicating that a smooth transition to the community is uniquely challenging for Saudi Arabian students with IDs who are learning within the Saudi educational system. These challenges are mainly due to a lack of availability of appropriate resources and transition services in public secondary schools. High schools in Saudi Arabia do not include transition-specific education for students with disabilities (Alhossan and Trainor, 2015; Almalky, 2018; Elsheikh and Alqurashi, 2013). As a result, high schools often do not provide education that helps students with IDs prepare for college or work. This lack of transition-specific education makes it hard for these students to succeed when they enroll in a university program. In fact, transition is still considered a relatively new endeavor in Saudi Arabia (Almalky, 2018), limiting our understanding of the practices and services currently in place to support the transition to the community, particularly for high-needs populations like students with IDs.

Research consistently highlights the critical role of well-prepared transition personnel in supporting students with intellectual disabilities (IDs) during their educational journey. Alhossan and Trainor (2015) examined faculty perceptions of transition preparation in Saudi Arabia, emphasizing the importance of staff training to enhance transition services. Similarly, Alnahdi (2017) found that although faculty appreciated transition curricula, they did not consistently integrate it into their teaching, underscoring the need for a more structured approach in preparatory programs for educators. These studies suggest that the effectiveness of transition services is closely tied to the quality of personnel preparation and call for more formalized training programs to address this gap.

The attitudes and knowledge of faculty and school psychologists are key to the successful inclusion and transition of students with IDs. Talapatra et al. (2018) found that school psychologists’ knowledge of transition services significantly impacts service delivery, with increased knowledge and positive attitudes improving the quality of these services. Gibbons et al. (2020) extended this discussion to the postsecondary education setting, revealing that while faculty and students were open to inclusive programs for students with IDs and autism, faculty expressed greater uncertainty about the impact of inclusion in the classroom. This underscores the need for institutional support in educating faculty about inclusive practices and fostering positive attitudes toward students with disabilities.

The transition from education to employment for students with disabilities presents numerous challenges, as highlighted in studies by Goodall et al. (2022) and Fernández-Batanero et al. (2022). These studies identify barriers such as social stigma, discrimination, and employer attitudes, which hinder successful transitions. Goodall et al. (2022)‘s systematic review recommends addressing these barriers through institutional and policy reforms, suggesting that targeted support and positive employer engagement are crucial facilitators for smoother transitions into the workforce for students with disabilities.

Faculty perceptions in the current study context refers to refer to the beliefs, attitudes, and opinions held by university faculty members regarding the university-based transition services provided to students with IDs (Carey et al., 2022).Research exploring faculty perspectives on the inclusion of students with IDs and other disabilities in higher education reveals both support and concerns. Carey et al. (2022) found that faculty acknowledged the benefits of inclusion, such as improved teaching skills and increased awareness of disabilities. However, they also highlighted significant challenges, including concerns about accommodating students and maintaining an inclusive classroom environment. These findings echo those of Gibbons et al. (2020), who noted that while faculty were generally willing to embrace inclusion, there were concerns about its practical implications in classroom settings. The research suggests that institutions must provide faculty with ongoing professional development and support to help them navigate these challenges effectively. Focusing on the Saudi Arabian context, Alsolami and Vaughan (2023) investigated teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with special educational needs (SEN) in general education settings. The study revealed overall positive attitudes among teachers, with no significant differences based on gender or teaching experience. This aligns with global trends advocating for inclusive education, but it also highlights the need for continued institutional support and training to enhance teachers’ ability to effectively include students with SEN in mainstream classrooms. This research provides important insights into how inclusive practices are evolving within the Saudi educational system, a key area of focus for your study on the transition of students with IDs and SEN in Saudi Arabia. Jezik (2022) examined faculty experiences with disability services, showing that while faculty appreciated the assistance provided, there was a range of competence in addressing the needs of students with learning disabilities. This suggests that ongoing support and professional development are essential to ensure faculty can effectively support students with disabilities. In both the U.S. and Saudi contexts, the research points to the importance of comprehensive support systems that equip educators with the knowledge and resources necessary to foster inclusive learning environments.

To conclude, the previous reviews show that faculty perceptions playing a vital role in integrating students with IDs into higher education, as demonstrated by Fisher (2008), who found positive faculty attitudes and advocated for training and support. Additionally, Alnahdi (2017) and Gibbons et al. (2020) emphasized the value of transition curricula while noting inconsistencies. Carey et al. (2022) and Jezik (2022) stressed the importance of faculty support, training, and accommodations, while Fernández-Batanero et al. (2022) and Goodall et al. (2022) underlined the importance of addressing challenges faced by students with disabilities in higher education. Key findings and conclusions include positive faculty attitudes, the need for improved transition curricula, and the significance of addressing faculty and student concerns and providing support. A research gap exists in the limited focus on the experiences of students with IDs themselves, while unaddressed points include specific experiences in Saudi Arabia, the impact of transition services on academic and social integration, parental roles, and long-term outcomes. The academic contribution lies in exploring faculty perceptions and providing recommendations, with the potential for enhanced insight by including student and family perspectives to understand the overall impact of transition services in Saudi Arabia.

Our study builds upon previous research in both Saudi and international contexts, addressing a significant gap in the literature regarding comprehensive faculty perspectives on transition services for students with IDs in Saudi higher education. While studies in Saudi Arabia have primarily focused on general attitudes toward inclusion and basic transition curricula, other international studies have investigated specific faculty experiences, challenges, and recommendations for supporting students with IDs in higher education settings. Moreover, the limited number of studies in Saudi Arabia contrasts sharply with the more extensive body of research available in other countries, highlighting the need for more context-specific investigations in the Kingdom. Therefore, this study aims to explore faculty perceptions of university-based transition services for students with IDs in Saudi Arabia. Using a descriptive analytical approach, the research surveys a sample of 153 faculty members across Saudi Arabian universities. This research endeavor aims to contribute valuable insights into the evolving landscape of inclusive higher education in Saudi Arabia, with a specific focus on the perspectives of faculty members. By examining these dimensions, this study seeks to advocate for evidence-based improvements in university-based transition services and ultimately enhance the educational experiences and outcomes of students with IDs in Saudi Arabian universities.

While there has been a significant amount of research on faculty perceptions and attitudes toward students with IDs in higher education, many gaps and uncertainties persist. This research aims to bridge these gaps, specifically focusing on the context of Saudi Arabian public postsecondary institutions. Key areas of investigation include faculty attitudes toward students with ID, the importance assigned to transition curricula in special education, and determinants influencing curriculum inclusion (Thoms et al., 2022). This study also probes the benefits and challenges faculty perceive when incorporating students with IDs into their courses and gathers suggestions for optimizing the inclusion process.

By examining the experiences of professors instructing students with IDs, this study gauges the adequacy of support from educational institutions. It further analyzes the factors that boost or hinder the confidence of special education teachers in Saudi Arabia when delivering transition services. This study also assesses the obstacles students with IDs face in higher education and proposes solutions to foster a more inclusive academic atmosphere. Finally, it evaluates the impact of transition and postsecondary programs on the job prospects of students with IDs, with a particular focus on the role of accreditation in maintaining program excellence.

1. To what extent do faculty members who specialize in special education demonstrate awareness of competencies related to the philosophical foundations of transition services for students with IDs?

2. To what extent are faculty members in special education departments familiar with competencies related to the assessment and evaluation of transitional programs for students with IDs?

3. To what extent are faculty members in special education departments aware of competencies related to the educational content of transitional programs for students with IDs?

4. How familiar are faculty members in special education departments with student behavior management and social interaction skills within transitional programs for students with IDs?

This study employed a quantitative descriptive research design to examine faculty members’ perceptions of transition program competencies for students with intellectual disabilities. Specifically, the study surveyed faculty members to assess their perceptions across four key competency areas: philosophical foundations, assessment competencies, educational content competencies, and behavior management skills. A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was used to collect data on these perceptions, allowing for systematic measurement and analysis of faculty views regarding the implementation and importance of these transition program components. This approach enabled us to analyze patterns in faculty perceptions and draw conclusions about the current state of transition program competencies in special education programs.

Data were collected through a questionnaire designed using Google Forms to assess faculty members’ perceptions regarding transitional services for special education in Saudi universities. The study tool (questionnaire) was divided into four domains: (1) Philosophical Foundations Competencies (6 items), which assessed theoretical understanding and program implementation; (2) Assessment Competencies (6 items), which evaluated skills related to student assessment and goal-setting; (3) Educational Content Competencies (7 items), which measured curriculum implementation and planning strategies; and (4) Behavior Management and Social Interaction Skills (6 items), which assessed competencies related to student behavior and social development. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and a literature review, and included demographic characteristics along with the 25 statements addressing transition services. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

The questionnaire was built and administered online through Google Forms and distributed via participants’ email addresses obtained from Saudi universities’ special education departments. To ensure validity and reliability, the questionnaire was validated by a panel of experts and checked for internal consistency among the items (see the complete questionnaire in Appendix A).

The study included a diverse sample of 153 faculty members from Saudi Arabian universities who were selected as a convenient sample. The demographic data of the participants revealed a gender distribution of 62.1% male (n = 95) and 37.9% female (n = 58). Regarding academic rank, the majority of participants were assistant professors (44.4%, n = 68), followed by professors (21.5%, n = 33). A significant portion of the participants (66.6%, n = 102) had received training in transitional services, while 33.3% (n = 51) had not. In terms of professional experience, the largest group had between 5 and 10 years of experience (47%, n = 72), followed by those with less than 5 years (30%, n = 46), and those with more than 10 years of experience (22.8%, n = 35). This diverse sample provides a comprehensive representation of faculty members across different demographics, ranks, and levels of experience in Saudi Arabian higher education institutions. It is worth mentioning that demographic data was not a major variable in our study, as we aimed to examine faculty perceptions toward transition services programs provided to ID students regardless of their gender, rank, and/or experience. The demographic data is summarized in Table 1. The study included participants from 11 Saudi universities that offer special education programs: King Saud University (n = 25), Taif University (n = 15), Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University (n = 16), King Faisal University (n = 11), Northern Borders University (n = 10), Imam Muhammad bin Saud Islamic University (n = 18), Tabuk University (n = 13), Al-Baha University (n = 11), Najran University (n = 15), Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (n = 12), and Jazan University (n = 4). The total number of participants was 153 faculty members representing special education departments across Saudi universities.

The collected data were imported into SPSS 26 for analysis. A descriptive analysis was conducted on the participants’ responses regarding their views about transition competencies. Means, standard deviations, and frequencies were computed to assess their perceptions.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the IRB committee at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

The questionnaire instrument was developed based on previous studies and a comprehensive literature review, ensuring content validity. Reliability was established through pilot testing with 50 participants, whose responses were excluded from the main study. Their feedback was collected and analyzed to confirm that the questionnaire statements were well-constructed and that all items were reliable. Cronbach’s alpha scores ranged from 0.913 to 0.981, indicating a very high level of reliability. Regarding the validity of the questionnaire, two procedures were employed to ensure it. First, a panel of experts was invited to assess the questionnaire for face validity, evaluating the suitability of the items, their linguistic formulation, relevance to the field, and appropriateness for the targeted sample. The panel also provided recommendations for eliminating, modifying, or adding specific items. Additionally, they helped determine how well the statements reflected the study’s questions, resulting in the removal of irrelevant questions that could undermine the validity of the results. Based on their feedback, adjustments were made to certain sections until an 80% consensus was reached, confirming face validity. Second, internal consistency was evaluated by calculating the correlation between each individual item and the total score (see Table 2). Pearson correlation values indicated a high correlation among the items, further ensuring the validity of the questionnaire.

Three main terms were used in this study and we need to define them. First, Faculty perceptions: refers to the beliefs, attitudes, and opinions held by university faculty members regarding the university-based transition services provided to students with IDs (Carey et al., 2022). Second, University-based transition services: In this study, university-based transition services are programs, resources, and support systems that help students with IDs transition from secondary to postsecondary education or employment (Ghasemi et al., 2023). Third, Students with IDs: this concept refers to individuals who have been diagnosed with limitations in intellectual functioning (typically measured by an IQ score below a certain threshold) and who may require additional support and accommodations to succeed academically and socially in a university setting (National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, 2011).

Objective scope: this study explored Saudi faculty perceptions of transition services for students with IDs in higher education.

Time scope: this study was conducted during the 2023 academic year. Data collection, analysis, and reporting occurred within this specific timeframe.

Spatial scope: the spatial scope of this study was limited to higher education institutions in Saudi Arabia. The research focused on faculty members working in universities and colleges within the country.

Human scope: this study included faculty members from diverse disciplines in Saudi higher education who interacted with students with IDs, along with relevant administrative and support staff.

This study contributes significant value to the field of special education and transition services in several interconnected ways. Primarily, by examining faculty perceptions of transition program competencies, the research addresses a critical gap in understanding how Saudi universities prepare special education teachers to support students with intellectual disabilities (IDs). The study’s focus on four essential competency domains - philosophical foundations, assessment, educational content, and behavior management - provides comprehensive insights into the current state of transition service preparation in Saudi higher education.

In terms of practical implications, the findings directly inform faculty development initiatives by identifying specific areas where professional development may enhance transition service delivery. This aligns with the study’s aim of understanding faculty perceptions regarding transition program implementation and supports the broader goal of improving educational outcomes for students with IDs. The research also contributes to policy development in Saudi higher education by providing evidence-based insights into the current status of transition program competencies, thereby supporting informed decision-making about program enhancement and resource allocation.

Furthermore, this study establishes a foundation for future research by systematically documenting current faculty perceptions across multiple Saudi universities. This comprehensive assessment of transition program competencies not only fills a significant research gap in the Saudi context but also provides a framework for comparative studies both regionally and internationally. The findings offer valuable insights for educational institutions seeking to enhance their transition services and support systems for students with IDs, while contributing to the broader discourse on inclusive education practices in higher education.

To achieve the study objectives, we used the social cognitive theory (SCT) by Bandura (1986), which includes the following aspects:

Self-efficacy: this central construct of SCT plays a pivotal role in understanding faculty perceptions. Self-efficacy is a person’s confidence in their ability to do a task or accomplish a goal (Ghasemi et al., 2023). Faculty self-efficacy includes confidence in their ability to instruct students with IDs. Faculty with strong self-efficacy are more enthusiastic about this role and more ready to change their teaching approaches to meet the various requirements of students with IDs. However, educators with poor self-efficacy may avoid these students or feel unprepared to help them.

Observational learning: SCT places significant importance on observational learning, also known as modeling (Lave and Wenger, 1991). This suggests that faculty members’ perceptions and behaviors can be heavily influenced by observing their colleagues. When faculty members witness their peers successfully engaging with students with IDs, implementing inclusive teaching strategies, and navigating the challenges effectively, they are more likely to emulate these behaviors. Conversely, observing resistance or difficulties among their colleagues can hinder the acceptance and implementation of transition services.

Environmental factors: the university environment is a complex interplay of various components, including policies, resources, support systems, and institutional culture (Mavroidis et al., 2022). Within this framework, environmental factors play a critical role in shaping faculty perceptions. For instance, an institution with inclusive policies and a commitment to accessibility sends a strong signal that faculty members are expected to support students with ID. Adequate resources, such as assistive technology and professional development opportunities, can empower faculty members to effectively engage with these students. Conversely, a lack of resources, unclear policies, or a non-inclusive institutional culture can create barriers and negatively impact faculty perceptions.

Reciprocal determinism: SCT emphasizes the dynamic and bidirectional nature of the relationship between personal, environmental, and behavioral factors (Bofah, 2016). In the context of this study, it means that faculty members’ perceptions of university-based transition services and their experiences interact with the institutional environment and policies. For example, positive experiences or successes in supporting students with IDs can boost faculty members’ self-efficacy, leading to more proactive engagement. Conversely, if faculty members face challenges or barriers, such as a lack of training or resources, this can erode their self-efficacy and hinder their willingness to engage effectively with these students.

In conclusion, this study’s use of SCT as its theoretical framework provides a deep understanding of how self-efficacy, observational learning, environmental factors, and reciprocal determinism affect faculty members’ perceptions. This framework helps to elucidate the complex dynamics of faculty engagement with university-based transition services for students with IDs in Saudi Arabia. By recognizing and addressing these factors, institutions can better support both faculty and students, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and conducive learning environment.

The first question gauged faculty members’ awareness within special education departments regarding the diverse competencies of the transitional program for students with disabilities. To assess this, descriptive statistics were used to calculate means, standard deviation, and frequencies of the participants’ responses. It should be that “neutral” scale must be converted into a number. To do so, this study followed the equation as per Siti Rahaya and Salbiah’s (1996). The interpretations for the mean scales are shown in Table 3.

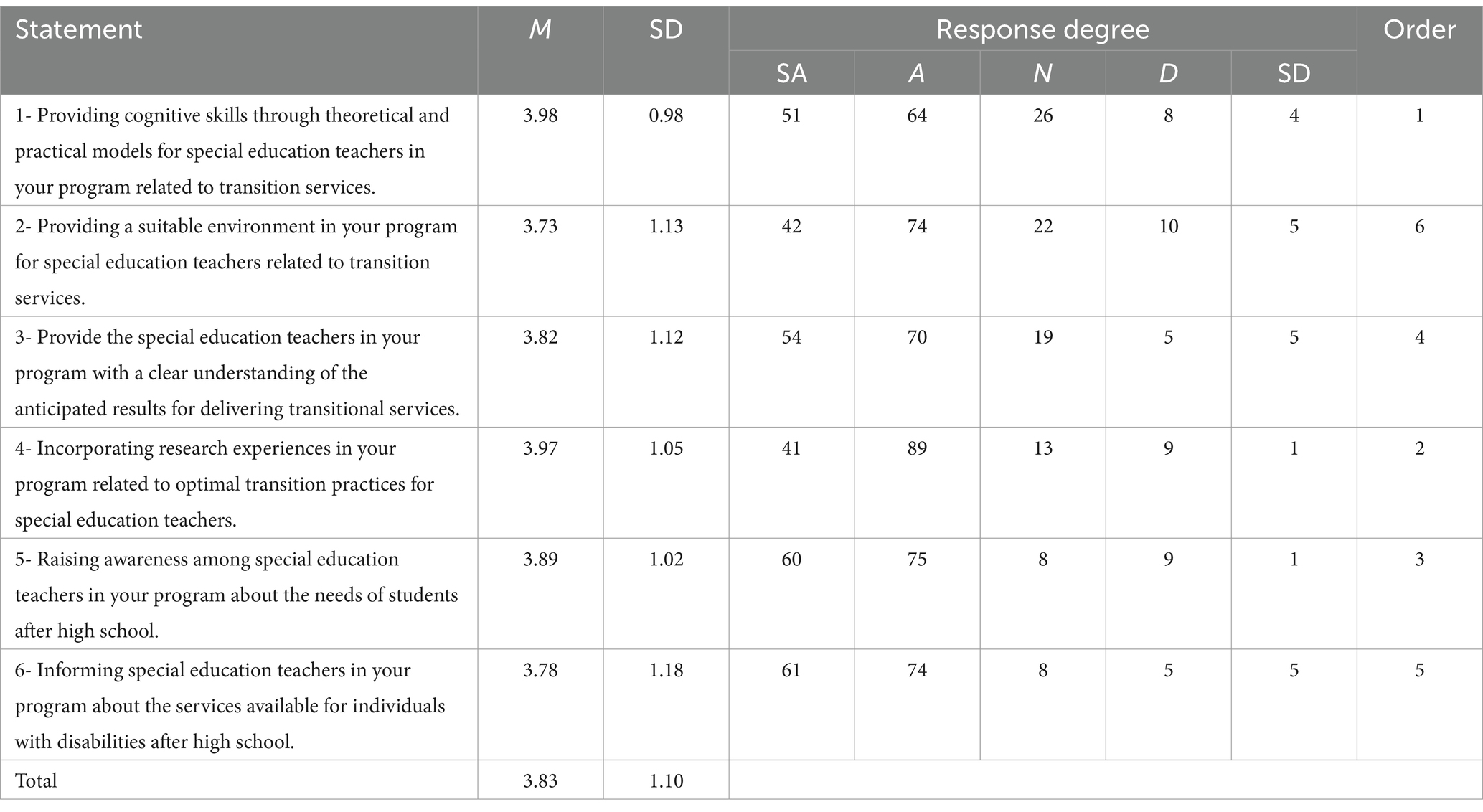

Table 3 provides compelling evidence of faculty members’ extensive awareness of diverse competencies within the transitional program for students with disabilities in special education departments. Notably, the survey results indicate that faculty members specializing in special education demonstrate a substantial awareness of competencies related to the philosophical foundations of transition services for students with ID. The overall means scores for the six statements were 3.83 (SD = 1.10), indicating a generally high level of awareness and implementation of transition service competencies. Faculty members reported particularly strong awareness in providing cognitive skills through theoretical and practical models (M = 3.98, SD = 0.98) and incorporating research experiences related to optimal transition practices (M = 3.97, SD = 1.05). They also demonstrated high awareness of students’ post-high school needs (M = 3.89, SD = 1.02) and clear understanding of anticipated results for delivering transitional services (M = 3.82, SD = 1.12). While still positive, faculty members indicated slightly lower, but still substantial, awareness in providing information about available services for individuals with disabilities after high school (M = 3.78, SD = 1.18) and creating a suitable environment for transition services (M = 3.73, SD = 1.13).

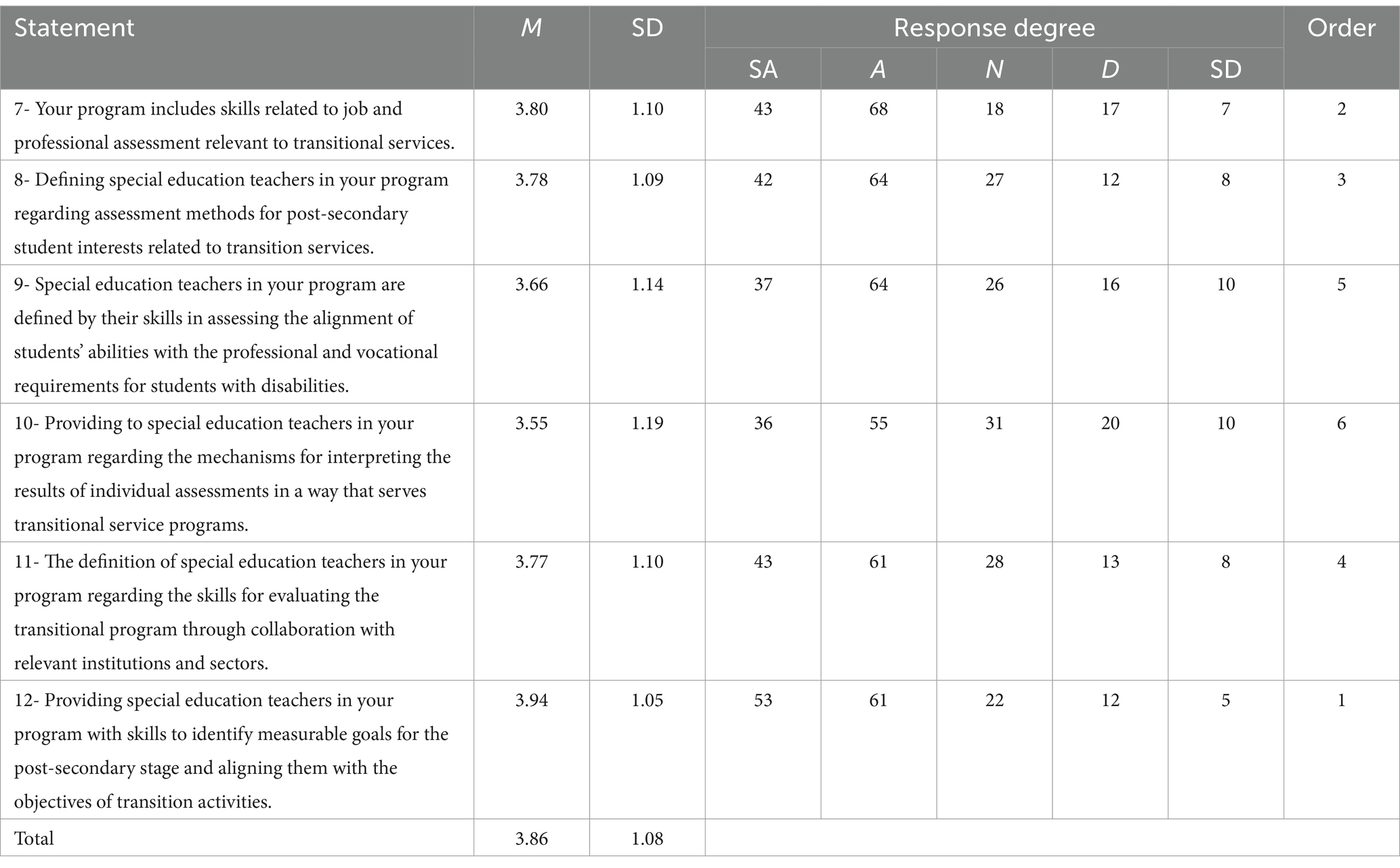

The survey results show that faculty members in special education departments have good knowledge about assessing and evaluating transition programs for students with IDs. They answered questions about six important areas, with an average score of 3.86 out of 5 (SD = 1.08). This suggests they highly understand these skills. Faculty members were best at teaching how to set clear goals for students after high school (M = 3.94, SD = 1.05) and how to assess job skills (M = 3.80, SD = 1.10). They were also very good at teaching how to assess students’ interests after high school (M = 3.78, SD = 1.09) and how to work with others to evaluate programs (M = 3.77, SD = 1.10). They scored a bit lower, but still high, on matching students’ abilities to job requirements (M = 3.66, SD = 1.14) and explaining assessment results (M = 3.55, SD = 1.19). Results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Perceptions of the participants toward philosophical foundations competencies for student with IDs transitional programs.

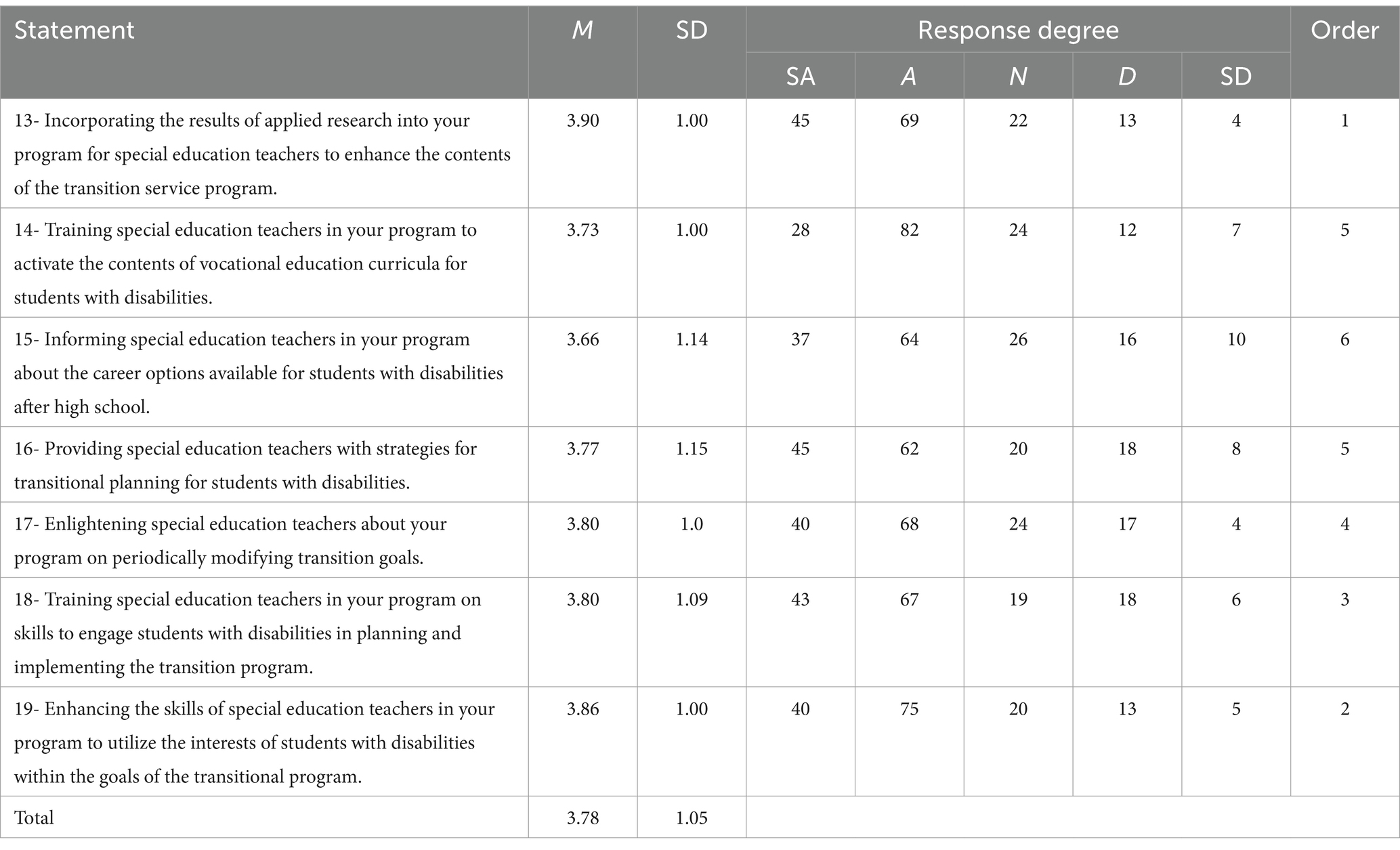

Table 5 reports that the perceptions of faculty members in special education departments are quite aware of competencies related to the educational content of transitional programs for students with IDs. They answered questions about seven important areas, with an average score of 3.78 out of 5 (SD = 1.05). This suggests they have good knowledge of these skills. Faculty members were best at using research results to improve transition service programs (M = 3.90, SD = 1.00). They were also good at teaching how to use students’ interests in transition programs (M = 3.86, SD = 1.00). Faculty showed strong awareness in training teachers to change transition goals when needed (M = 3.80, SD = 1.0) and to involve students in planning their transition (M = 3.80, SD = 1.09). They scored a bit lower, but still well, on teaching about transition planning strategies (M = 3.77, SD = 1.15) and how to use vocational education curricula (M = 3.73, SD = 1.00). The lowest score, though still positive, was for informing teachers about career options for students after high school (M = 3.66, SD = 1.14).

Table 5. Perceptions of the participants toward assessment competencies for transitional program for students with IDs.

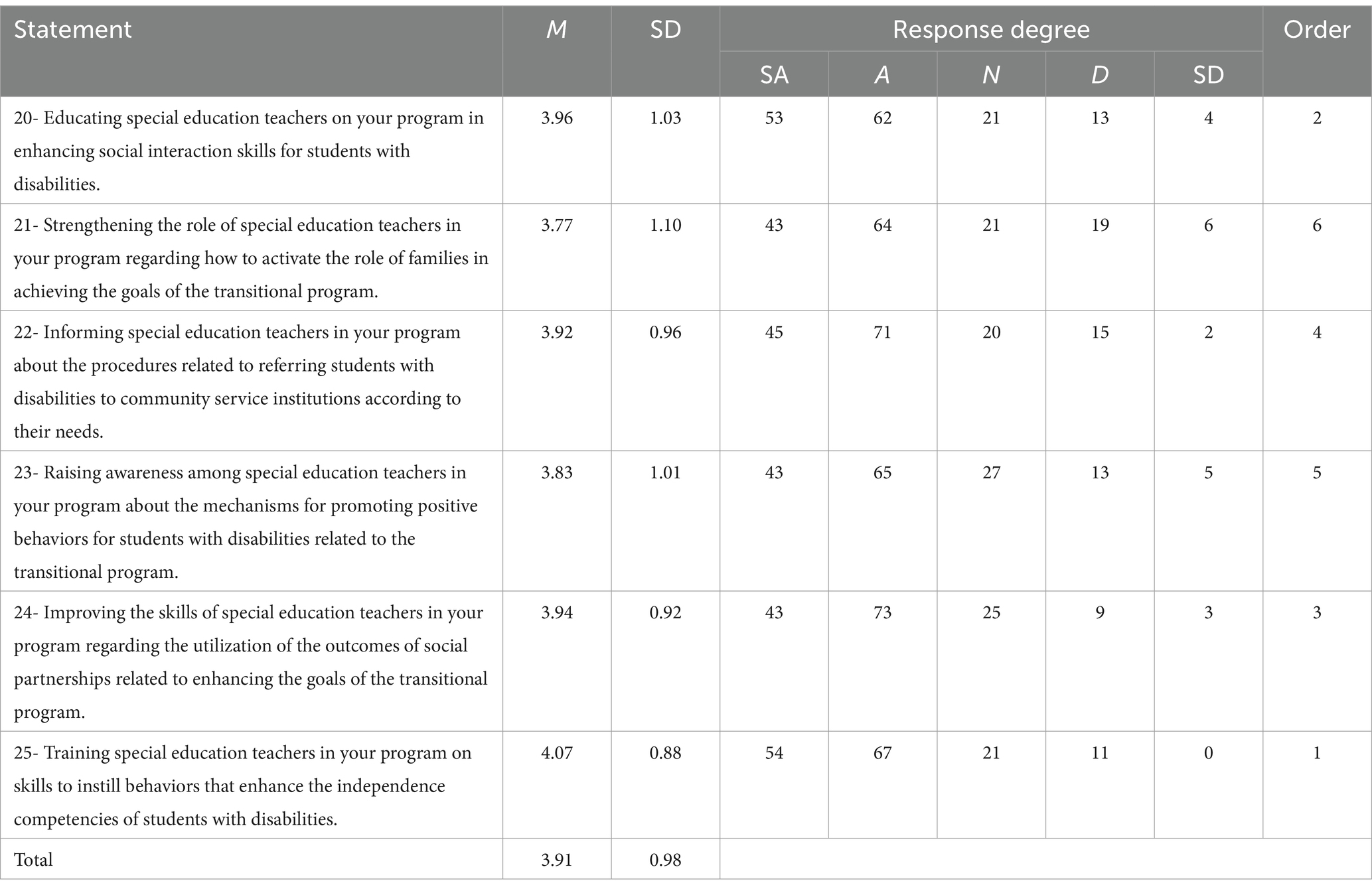

The survey results, as reported in Table 6, show that faculty members in special education departments are quite familiar with student behavior management and social interaction skills within transitional programs for students with IDs. They answered questions about six important areas, with an average score of 3.91 out of 5 (SD = 0.98). This suggests they have good knowledge of these skills. Faculty members were best at training teachers to help students become more independent (M = 4.07, SD = 0.88). They were also very good at teaching how to improve students’ social interaction skills (M = 3.96, SD = 1.03) and how to use community partnerships to help with transition goals (M = 3.94, SD = 0.92). Faculty showed strong familiarity with teaching about how to refer students to community services (M = 3.92, SD = 0.96) and how to encourage positive behaviors in students (M = 3.83, SD = 1.01). The lowest score, though still positive, was for teaching how to involve families in transition programs (M = 3.77, SD = 1.10).

Table 6. Perceptions of the participants toward educational content competencies for transitional program for students with IDs.

To conclude, faculty members in special education departments demonstrate a high level of awareness and familiarity with various competencies related to transition services for students with IDs. The overall mean scores for the different sections ranged from 3.78 to 3.91 on a 5-point scale, indicating strong knowledge and implementation of transition service competencies. Faculty members showed particular strengths in areas such as behavior management, social interaction skills, and providing cognitive skills through theoretical and practical models. While all areas were rated positively, there may be room for slight improvement in aspects like family involvement and interpreting individual assessment results. Overall, these findings suggest that faculty members are well-prepared to train special education teachers in transition services (Table 7).

Table 7. Perceptions of the participants toward student behavior management and social interaction skills within transitional program for students with IDs.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into faculty perceptions of university-based transition services for students with IDs in Saudi Arabia. The results demonstrate that faculty members in special education departments possess a high level of awareness and competency across various domains of transition services, including philosophical foundations, assessment and evaluation, educational content, and behavior management.

In relation to the social cognitive theory (SCT) framework employed in this study, the high levels of awareness and competency reported by faculty members suggest a strong sense of self-efficacy in their ability to support students with IDs. This aligns with Bandura’s (1986) concept of self-efficacy, indicating that faculty members feel confident in their capacity to implement effective transition services. This self-efficacy appears to be reinforced through observational learning, as evidenced by consistent high scores in implementing theoretical models and research-based practices. The positive perceptions across all domains may be attributed to observational learning, as proposed by SCT, where faculty members have likely observed successful implementations of transition services among their peers.

To detail the specific competencies reported by our participants, results show high awareness of philosophical foundations, indicating that faculty members have a solid theoretical understanding of transition services. This finding is consistent with Alnahdi (2017)’s study, which emphasized the importance of transition curricula in special education programs. The strong competency in providing cognitive skills through theoretical and practical models further supports this conclusion and suggests that faculty members are well-equipped to prepare future special education teachers. Likewise, competencies related to assessment and evaluation perceived by Saudi faculty members reported high scores. This suggests that faculty members demonstrated proficiency in crucial areas such as setting post-high school goals and assessing job skills. This aligns with the recommendations of Talapatra et al. (2018), who emphasized the importance of specific knowledge in transition services. The high competency in these areas suggests that Saudi universities are preparing educators who can effectively evaluate and support students with IDs in their transition to post-secondary life. Concerning educational content competencies, results reveal a strong emphasis on research-based practices and student involvement in transition planning. This approach is consistent with international best practices and addresses the concerns raised by Almalky (2018) regarding the need for improved transition services in Saudi Arabia. The focus on utilizing research results to enhance transition service programs indicates a commitment to evidence-based practices in Saudi higher education institutions. The high familiarity with behavior management and social interaction skills is particularly noteworthy. This competency aligns with the findings of Carey et al. (2022), who identified engagement and teaching skills improvement as key benefits of including students with IDs in university classes. The strong emphasis on promoting student independence suggests that faculty members are well-prepared to foster autonomy among students with IDs, addressing a crucial aspect of successful transition outcomes.

However, the slightly lower scores in areas such as family involvement and interpreting individual assessment results, while reported high, still indicate potential areas for improvement. These findings echo the concerns raised by Almalki (2022) regarding the relationship between schools and families in the transition process. Enhancing faculty competencies in these areas could further strengthen the overall quality of transition services.

The generally positive perceptions across all domains suggest that the environmental factors within Saudi universities, as conceptualized in SCT, are supportive of transition services for students with IDs. This positive environment likely contributes to the high levels of faculty self-efficacy observed in the study. The reciprocal determinism proposed by SCT is evident in the way faculty members’ positive experiences and competencies reinforce their engagement with transition services. Despite these encouraging findings, it is important to note that this study focused solely on faculty perceptions. Future research should explore the perspectives of students with IDs and their families to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of transition services in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the long-term outcomes of students who have received these transition services would provide valuable insights into the real-world impact of these programs.

To sum up, this study reveals that faculty members in Saudi Arabian universities possess strong competencies in delivering transition services for students with IDs. These findings are encouraging and suggest that Saudi higher education institutions are making significant strides in supporting students with IDs in their transition to post-secondary life. However, continued efforts to enhance family involvement and assessment interpretation skills could further improve the quality of transition services. As Saudi Arabia continues to develop its approach to inclusive education, reflecting its 2030 Vision, these insights can inform policy decisions and professional development initiatives, ultimately contributing to better outcomes for students with IDs in higher education and beyond.

This study’s conclusions are multifaceted. Faculty members in Saudi special education departments exhibit a significant understanding of transitional program competencies, which underscores their commendable awareness. Their perceptions emphasize the vital role of teacher preparation and skills in equipping effective university-based special education transition services for students with IDs. Additionally, competencies in evaluation, educational content, and managing student behavior, along with promoting social and family interaction skills, hold significant importance in faculty members’ views, guiding program development. These findings collectively contribute to the enhancement of transitional programs, fostering inclusivity and student success in Saudi higher education.

The study provides significant practical implications regarding teacher training programs in developing pre-service teachers’ competencies for managing transitional programs for students with IDs, both internationally and locally. Our findings emphasize the importance of continuous faculty development in special education and transition services to keep pace with evolving best practices. The results suggest that teacher preparation programs should maintain a careful balance between theoretical foundations and practical applications, while incorporating specialized courses for students with disabilities in Saudi university curricula to address educational environment changes and reduce anxiety for students and their families. Strengthening collaborative partnerships with community providers and stakeholders is vital to enhancing transitional program effectiveness, as is the integration of independence skills, social interactions, and familial engagement into curricula for holistic student development. The findings highlight a consensus among faculty members in Saudi universities’ special education departments, irrespective of gender, offering reassurance to program designers and policymakers. This gender-neutral perspective enables educational institutions to implement inclusive strategies that enhance transitional services through student-centered approaches and collaborative planning.

• Prioritize ongoing faculty training and development to keep faculty members updated with the latest research and best practices in special education and transition services.

• Engage faculty members in the design and development of transitional programs to ensure alignment with their insights and priorities.

• Develop transitional programs that focus on holistic student development, including behavior management as well as social and family interaction skills.

• Offer specialized training in program evaluation and assessment skills to enhance faculty members’ abilities in this critical area.

• Strengthen collaborative partnerships with community service providers, employers, and stakeholders to enhance transitional program effectiveness.

The limitations include this study’s focus on Saudi Arabian special education departments, which may not fully represent international perspectives. Future research could broaden the geographical scope. The reliance on self-reported data could have introduced response bias, suggesting the incorporation of additional data sources for enhanced reliability. Future studies should consider the perspectives of students, parents, and other stakeholders for a more comprehensive view. While no significant gender-based differences were found in faculty perceptions, exploring variations among demographic groups (e.g., age, experience) could yield nuanced insights. Longitudinal studies could assess the long-term impact of faculty perceptions on transitional program outcomes. Lastly, as education practices evolve, future research should examine evolving competencies and best practices in transitional programs to meet changing student needs.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

RA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1437836/full#supplementary-material

Alhossan, B. A., and Trainor, A. A. (2015). Faculty perceptions of transition personnel preparation in Saudi Arabia. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 40, 104–112. doi: 10.1177/2165143415606665

Almalki, S. (2022). Transition services for high school students with intellectual disabilities in Saudi Arabia: issues and recommendations. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 68, 880–888. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2021.1911564

Almalky, H. A. (2018). Investigating components, benefits, and barriers of implementing community-based vocational instruction for students with intellectual disability in Saudi Arabia. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 53, 415–427. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26563483

Almutairi, R. A. (2018). Teachers and practitioners’ perceptions of transition services for females with intellectual disability in Saudi Arabia (publication no. 10933434) [doctoral dissertation]. Greeley, Colorado: University of Northern Colorado.

Alnahdi, G. (2014). Special education programs for students with intellectual disability in Saudi Arabia: issues and recommendations. Available at:https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ105828915 [Accessed February 11, 2022].

Alnahdi, G.H. (2017). Best practices in the transition to work services for students with intellectual disability: perspectives by gender from Saudi Arabia. Available at:https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1120712.pdf [Accessed March 31, 2020].

Alothman, S. (2010). Ministry of Education provides services for 10 out 16 categories of disabilities. Available at:http://www.alriyadh.com/2010/07/21/article545405.html [Accessed August 4, 2020].

Alqraini, T. A. S. (2013). The extent of provision of transitional services in educational institutions for students with multiple disabilities and their importance from the perspective of their employees. Educ. Psychol. Lett. 40, 58–85.

Alsolami, A., and Vaughan, M. (2023). Teacher attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities in Jeddah elementary schools. PLoS One 18:e0279068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279068

Bofah, E.A. (2016). Reciprocal determinism between students’ mathematics self-concept and achievement in an African context. Available at:https://hal.science/hal-01287995/document [Accessed August 7, 2020].

Bouck, E. C., and Flanagan, S. M. (2016). Preparing transition-age students with high-incidence disabilities for postsecondary education and employment: a review of the literature. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 39, 131–143. doi: 10.1177/2165143415580676

Carey, G. C., Downey, A. R., and Kearney, K. B. (2022). Faculty perceptions regarding the inclusion of students with intellectual disability in university courses. Inc 10, 201–212. doi: 10.1352/2326-6988-10.3.201

Carter, E. W., Boehm, T. L., Biggs, E. E., and Annandale, N. H. (2016). Characteristics of effective secondary transition programs for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 31, 115–123. doi: 10.1177/1088357615580271

Chiba, C., and Low, R. (2007). A course-based model to promote successful transition to college for students with learning disorders. Available at:https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ825763 [Accessed Sptemper 3,2024]

Cimera, R. E., Burgess, S., and Bedesem, P. L. (2014). Does providing transition services by age 14 produce better vocational outcomes for students with intellectual disability? Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 39, 47–54. doi: 10.1177/1540796914534633

Cimera, R. E., Burgess, S., and Wiley, A. (2013). Does providing transition services early enable students with ASD to achieve better vocational outcomes as adults? Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 38, 88–93. doi: 10.2511/027494813807714474

Elsheikh, A. S., and Alqurashi, A. M. (2013). Disabled future in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci 61:16. Available at: https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol16-issue1/K01616871.pdf

Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., and Fernández-Cerero, J. (2022). Access and participation of students with disabilities: the challenge for higher education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:11918. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191911918

Fisher, J. W. (2008). Impacting teachers’ and students’ spiritual well-being. J. Beliefs Values 29, 253–261. doi: 10.1080/13617670802465789

Ghasemi, S., Bazrafkan, L., Shojaei, A., Rakhshani, T., and Shokrpour, N. (2023). Faculty development strategies to empower university teachers by their educational role: a qualitative study on the faculty members and students’ experiences at Iranian universities of medical sciences. BMC Med. Educ. 23:260. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04209-0

Gibbons, M. M., Cihak, D. F., Mynatt, B., and Wilhoit, B. E. (2020). Faculty and student attitudes toward postsecondary education for students with intellectual disabilities and autism. J. Postsec. Educ. Disabil. 28, 149–162. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1074661

Goodall, G., Mjen, O. M., Wits, A. E., Horghagen, S., and Kvam, L. (2022). Barriers and facilitators in the transition from higher education to employment for students with disabilities: a rapid systematic review. Front. Educ. 7:882066. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.882066

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2004). Vision 2030 kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Available at:http://www.vision2030.gov.sa

Jezik, A. (2022). Faculty perceptions on working with students with learning disabilities (publication no. 4928) [Master’s thesis]. Charleston, Illinois: Eastern Illinois University. EIU Institutional Repository.

Landmark, L. J., Ju, S., and Zhang, D. (2010). Substantiated best practices in transition: fifteen plus years later. Except. Individ. 33, 165–176. doi: 10.1177/0885728810376410

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation learning in doing. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Marshall, J. (2017). Contemporary debates in education studies : Routledge. Available at: https://www.routledge.com/Contemporary-Debates-in-Education-Studies/Marshall/p/book/9781138680241?srsltid=AfmBOopN_INrCMFIA_WOg-5aD6AHShYwoeigkuHAno7ToekzJ8VSisKG

Mavroidis, I., Kourkoutas, E., and Giovazolias, T. (2022). Perceived knowledge and attitudes of faculty members towards inclusive education for students with disabilities: evidence from a Greek university. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1488. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031488

Ministry of Labor and Social Development of Saudi Arabia. (2017). Welfare of disabled persons. Available at:https://www.hrsd.gov.sa/en/media-center/news/261449 [Accessed February 10, 2020].

National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities. (2011). Intellectual disability. Available at:https://www.parentcenterhub.org/intellectual/ [Accessed July 10, 2020].

Rowe, D. A., Alverson, C. Y., Unruh, D. K., Fowler, C. H., Kellems, R., and Test, D. W. (2015). A Delphi study to operationalize evidence-based predictors in secondary transition. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 38, 113–126. doi: 10.1177/2165143414526429

Siti Rahaya, A., and Salbiah, M. (1996). Pemikiran guru cemerlang: Kesan teradap prestasi pengajaran. Bangi: Fakulti pendidikan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Skinner, M. E., and Lindstrom, B. D. (2003). Bridging the gap between high school and college: strategies for the successful transition of students with learning disabilities. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 47, 132–137. doi: 10.1080/10459880309604441

Talapatra, T., Lindsay, S., and Alameda-Lawson, G. (2018). Transition services for students with intellectual disabilities: school psychologists’ perceptions. Psychol. Sch. 56, 56–78. doi: 10.1002/pits.22189

Thoms, L.-J., Colberg, C., Heiniger, P., and Huwer, J. (2022). Digital competencies for science teaching: adapting the DiKoLAN framework to teacher education in Switzerland. Front. Educ. 7:802170. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.802170

Trainor, A. A., Morningstar, M. E., and Murray, A. (2016). Characteristics of transition planning and services for students with high-incidence disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Quart. 39, 113–124. doi: 10.1177/0731948715607348

Wandry, D. L., Webb, K. W., Williams, J. M., Bassett, D. S., Asselin, S. B., and Hutchinson, S. R. (2008). Teacher candidates’ perceptions of barriers to effective transition programming. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 31, 14–25. doi: 10.1177/0885728808315391

Wehman, P., Sima, A. P., Ketchum, J., West, M. D., Chan, F., and Luecking, R. (2015). Predictors of successful transition from school to employment for youth with disabilities. Exceptionality 25, 323–334. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9541-6

Keywords: faculty perceptions, transition services, special education, intellectual disabilities, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Alhilfi RA (2025) Faculty perceptions of university-based transition services for students with intellectual disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Front. Educ. 10:1437836. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1437836

Received: 27 June 2024; Accepted: 10 February 2025;

Published: 26 February 2025.

Edited by:

Laura Maria Dunne, Queen’s University Belfast, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Alhilfi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Reem Abdullah Alhilfi, UmF0bXV0YWlyaUBpbWFtdS5lZHUuc2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.