- 1English Studies Department, Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Universitat Jaume I, Castellón de la Plana, Spain

- 2Department of Sociology, NORDIK Institute Research Associate, Algoma University, Sault Ste. Marie, ON, Canada

Introduction: The Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) is described as a pedagogical experience linking the classrooms of two or more higher education institutions across culturally and linguistically differentiated regions. COIL intends to provide academics and students with the ability to communicate and collaborate with peers internationally through online interactions. During the Fall of 2021, this collaboration involved the Universitat Jaume I (UJI), located in the city of Castelló de la Plana in Spain and Algoma University, located on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabek Nation, as well as the homelands of the Métis Nation. The student profiles, each institutions’ geographical locations, as well as the linguistic, cultural and critical approaches to teaching and learning provided ample opportunities and challenges for the development and implementation of this experience.

Methods: The purpose of this paper is to provide a pedagogical reflection on the development of a 5-week module taught together during three academic years. The authors provide an account and reflection of their collaboration centered on the institutional challenges and opportunities that currently exist for courses that aim to engage Indigenous and critical/ecological thinking.

Results and discussion: The background of the collaboration leads to a detailed analysis of the context of COIL implementation and the reflections on the modules’ development and improvement. Our recommendations are based on lessons learned from the substantive and technical challenges and opportunities on the complexity of teaching about contemporary ecological/social issues, as well as the tools required to inspire future activists.

1 Introduction

The COIL experience has been a comparative exercise between the two regions (Canada and Spain) in relation to the barriers and opportunities for achieving the United Nations Development Goals, with special emphasis on SDG5, SDG13 and SDG16, although it is worth highlighting the interconnectedness between all the goals (in our case we necessarily touch on goal SDG10 because of their close relationship with SDG13 in the approach we follow).

Our collaboration started in 2021 with a COIL-VE agreement (Collaborative Online International Learning Virtual Exchange) between both universities in their efforts to foster international cooperation and innovation. One of the benefits of this type of exchange is to provide accessibility to students, especially underrepresented student groups, who may not be able to travel to another country for quality international learning opportunities. Our experience and the experience of other colleagues has promoted the creation of more stable collaboration in the form of Innovation in Education UJI projects in 2023-24 and Algoma University Global Mobility and COIL-VE programmes. The university grants for these innovation projects now includes COIL methodology as one of the five criteria valued as positive. The grants value the description of the project’s aims and experience, proposed activities and assessment mechanisms as part of the COIL project implementation. Algoma University provided the opportunity to travel to UJI and meet students and faculty through the Canadian government’s Global Skills Opportunity (GSO) program. The GSO facilitates travel abroad for students who wouldn’t otherwise get an opportunity to study abroad. This is a mobility program that provides unique international study experiences that help students build intercultural competencies needed for work globally.

The strategies for co-creating curriculum for our first COIL experience titled ‘Influences on the Social Construction of Gender’, provided students and the directors an opportunity to get to know one another, their institutions and the social, political, economic and linguistic contexts, as well as compare their perspectives on gender constructions and gender based social inequities and crimes. Our analysis is grounded in a critical pedagogy that centers intersectional and decolonizing frameworks. The choice of this framework aimed at grounding the instructors’ areas of expertise to develop a critical analysis and discussion of the evolving process and outcomes of the course focusing on environmental justice. Specifically, this framework allowed the instructors to shape the current module’s learning objectives.

During the second and third experiences, we developed our COIL project around “Movements for Social and Environmental Justice,” which was adjusted and developed in the third module and academic year (“Incorporating Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education Curricula”) to cover, among other issues, specific SDG evaluation criteria. During these two academic years the students of the Criminology and Security (Universitat Jaume I) worked collaboratively with Sociology students (Algoma University, Canada). The synergies between sociology and criminology make this international online combination an ideal breeding ground for participants’ learning and future professional development (Niitsu et al., 2023). The focus has been a critical examination of the social relations of diverse communities and the meanings derived from the construction of the environment. This is an instance of what Sachs (2015) describes as the role of universities in realizing SDGs. Sachs proposes universities are engines of the local and national economy. But this is not the only contribution universities can make. In fact, prioritizing critical thinking can increase a global understanding of SDGs and their interconnectedness. To create “a network of problem-solving made up of the world’s universities…called… the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN)” (Sachs, 2015: 62) it is necessary to equip learners not only with knowledge but also with critical thinking skills and the ability to enact intercultural competence. The project provided a basis for critique of ecological issues while emphasizing environmental justice movements in the context of social and environmental justice. Thus, students learnt about the relationship between environmental problems and marginalization/exclusion, racial and gender discrimination while focusing on resistance and direct action within an interdisciplinary and experiential framework.

Extant literature defines Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) as a pedagogical experience linking the classrooms of two or more higher education institutions across culturally and linguistically differentiated regions (Guth, 2013). COIL intends to allow academics and students to communicate and collaborate with peers internationally through online interactions (Rubin, 2015; Borger, 2022; Kučerová, 2023). Beginning in the Fall of 2021, this collaboration involved the Universitat Jaume I (UJI), located in the city of Castelló de la Plana in Spain, and Algoma University, located on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabek Nation, as well as the homelands of the Métis Nation. Factors like teacher and student profiles, each institution’s geographical location, and the linguistic, cultural, and critical approaches to teaching and learning provided ample opportunities and challenges for developing and implementing this experience.

In this article, the course directors critically reflect on the 5-week COIL module they taught together. The module resulted from working collaboratively during three academic years in three different academic courses During this time, the course directors integrated the adapted content and pedagogy of the COIL module to meet students’ needs and interests while improving each iteration based on the lessons learned from previous modules. The conclusion will provide recommendations based on an assessment of our collaboration centered on the institutional challenges and opportunities that currently exist. The propositions will support efforts to engage in COIL and support the course directors in a meaningful way.

2 Literature review

Recent research in educational leadership has shown that formal and informal sustainability defenders face numerous barriers when implementing Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) (UNESCO, 2014) in the classroom (Foley, 2021; Žalėnienė and Pereira, 2021). Among others, the scientific literature alludes to a lack of specific training (Didham and Ofei-Manu, 2018; Qablan, 2018), bureaucratic overload (Huang et al., 2021), and scarcity of time and resources (Pesanavi and Lupele, 2018). From an educational leadership perspective, as much as it is essential to integrate the SDGs in postsecondary institutions, other issues constantly take priority (Amorós Molina et al., 2023). In practice, efforts to meaningfully integrate the SDGs into the curriculum amount to singular actions that often lack continuity. These issues are exacerbated by the difficulties in generating collective awareness and developing a sustainable culture among students, teachers, and the environment. To address these issues, the course directors engaged in an ongoing commitment to develop COIL modules that were refined each year, with the end goal of developing a framework to apply regardless of the content of the courses selected for the COIL experience. The next section provides a historical overview of these 3 years, followed by a critical discussion on the key challenges and opportunities experienced and future directions for ongoing collaborations.

3 Collaborative international online learning development

In this section, we examine the development of our international collaboration progress from 2021 to 2024, three academic years. The cooperating instructors are the authors of this paper and discuss the development of their work together with all their students. Our institutional partnership was an opportunity for internationalization where students could meet and learn from other students located in a different country and cultural setting sharing an online classroom. The COIL experience was a portal for our students to learn about their disciplines from a different perspective in a practice that was integrated in their curricula.

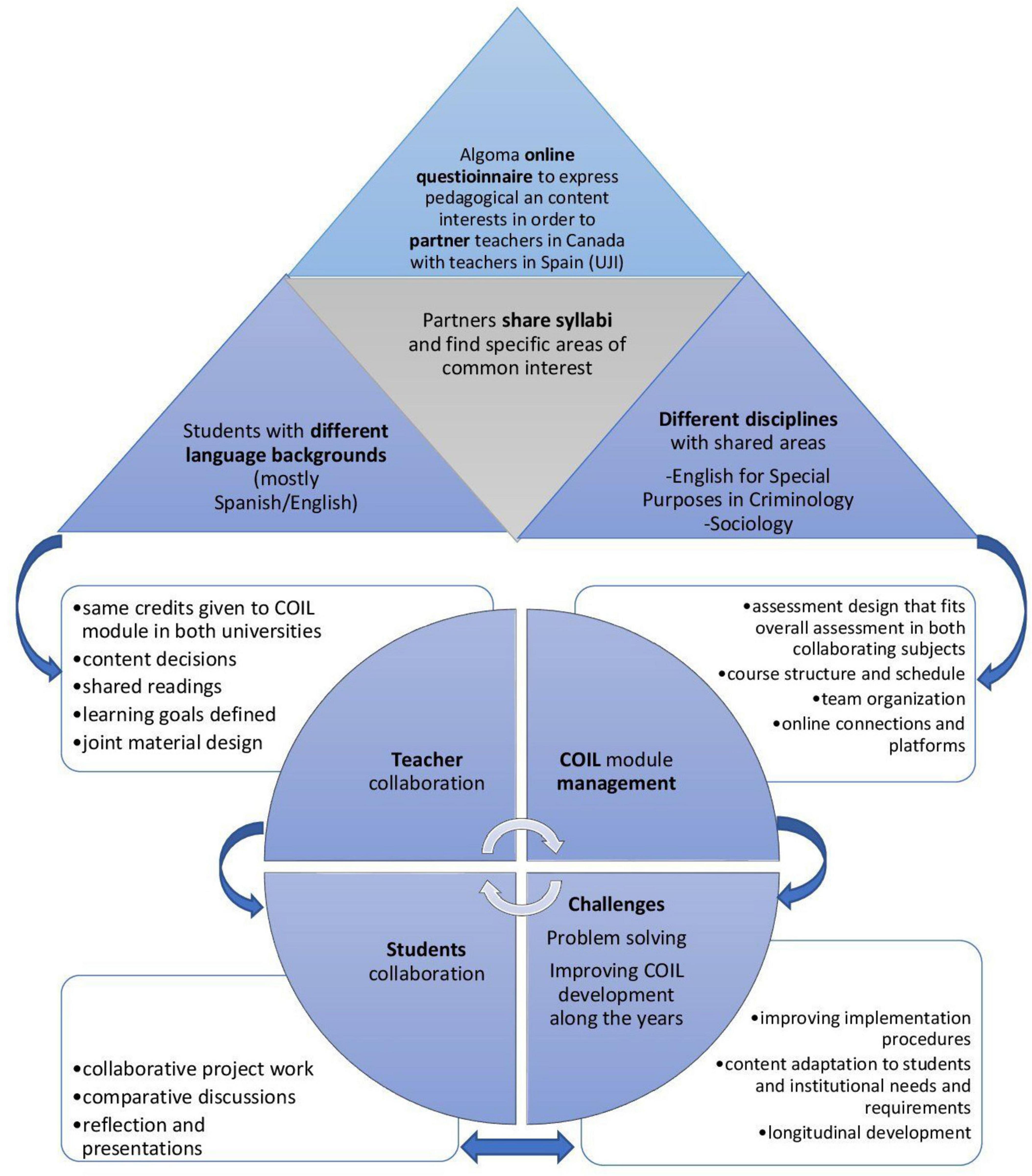

It was essential during the first year that the topic clearly related to both disciplines. SDG5 is tackled both in criminology studies (from a psychological and a law enforcement perspective) and in sociology studies where gender is analyzed as a social construct that relates to gender-based inequalities in power and privileges. It is the complementary views of both disciplines what made course alignment possible. Each group had to understand the perspective explained by the other group, which always brought up new points of view to the topic under study. The curiosity to find out how specific laws worked in each country, how society reacts in front of the proposed topics, or how related crimes and laws were approached in both countries, triggered student discussions. An important aspect in teacher coordination was to design tasks with sufficient information to generate interest in the students. In this sense, for instance, during the first-year students on both sides were impressed with how much society and law differed between the two countries, and the information shared during the project development together with the research they performed promoted student engagement and became evident in project outcomes when students suggested changes that should be made in their respective countries. Figure 1 summarizes the method employed in the COIL implementation development.

Figure 1. Method and reflective practice for instructors engaging in COIL development over a period of 3 years.

The pedagogical reflection reported here provides data that are related to the teachers’ development. It is a study of how teachers’ knowledge and know-how is interwoven in the educational processes and changes throughout the years. The study exemplifies instances of success and challenges and how teachers evolved in their planning of the 3 years as (1) an answer to problems encountered, (2) a shared evaluation of how effective tasks were (task reformulation or elimination, task improvement, materials adaptation to the students’ time for completing tasks, changing the module’s content from very specific to very open in order to adapt and cater for different students’ interests).

This pedagogical reflection (Ulmer et al., 2020) is based on instructor insights from student assessment procedures; ongoing feedback on the course based on students’ participation and emails; and ongoing recorded instructor reflections (see Supplementary Appendix 2). The shared interactive journaling process provided both teachers the necessary background information to understand which could be the relevant strategies to prepare the sessions. This process was used to become aware of different meanings and acceptable interactions under each culture and instructional settings. The circumstances under which team work progressed in a particular session helped visualizing a picture of each group in the context of their shared knowledge and reactions within the framework of international collaborative team work.

Our analysis is based on reflection on the following:

A. Student Assessments - how teachers interpreted the rubrics

B. Ongoing feedback through emails and in class (both online and after class comments)

Feedback themes:

1. Collaboration:

a. different time zones

b. different schedules

c. different expectations when scheduling meeting times

2. Task

a. different task interpretations

b. task expectations (also in relation to institutional practice, for instance on how to make a presentation and what to include/exclude)

c. task distribution of responsibilities within group members

3. Language and cognitive competency:

a. different language levels

b. intercultural language awareness of political correctness

C. Ongoing recorded instructor reflections as reported in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Due to time and institutional constraints, it was not feasible to undergo an ethics review process to include student data that could be reported in the study. During the first and second years, students were asked to comment on their view of the COIL experience when presenting the final projects and comments were useful when re-designing the course. Their comments cannot be considered unbiased however, since they were part of their final presentations. They were however very useful to make instructors aware of details they could otherwise not predict or be conscious of. In the third year, final questionnaires were used as feedback for teachers at the end of each course but could not be used as part of the study because the consent procedures at both institutions could not be followed. This is an aspect that we would like to highlight for researchers planning to engage in a COIL project: consent procedures should be designed well in advance of the teaching sessions and in parallel with the design of each module. Institutional processes related to obtaining informed consent is highly regulated and managing to cross procedures that are accepted by both institutions requires additional planning and preparation. Working with a variety of students implies designing interrogation procedures that are adequate for all students in all the topics dealt with in the COIL practice. This will also be a linguistic challenge since formulation of questions will need careful phrasing either in questionnaires, surveys or interview format. If task results are used in the future, a full explanation stating how, why and what are they used for will also be needed. These are of course common procedures in research, but we want to emphasize that the complexity of the project presented here in terms of international collaboration, different ethnic backgrounds and different languages and language proficiency levels would need explanations that are adequate for a wide range of students and that considers comprehensibility of the instructions and specific questions as well as data use.

3.1 Year 1: exploring and building on commonalities

In July 2021, an invitation to express interest in developing and incorporating COIL modules into existing courses brought together the course directors from Universitat Jaume I (Castellón de la Plana, Spain) and Algoma University (Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario). Foundational workshops offered to course directors provided information on virtual team building, partnership, and the importance of reflection in developing COIL modules effectively. Another set of workshops focused on supporting students’ intercultural skills online, considerations for maintaining a strong relationship with a COIL teaching partner, options and approaches to bridging language differences, and how to approach team building and developing trust.

After several virtual meetings and sharing documents throughout July and August, the course directors learned about each other, their institutions, and their unique social, political, economic, and linguistic contexts. Ongoing meetings and exchanges provided the space and time to co-develop this first experience from their unique perspectives on gender constructions, gender-based social inequities, and gender-related crimes in different sociocultural contexts. The course directors finished developing the first academic module, ‘Influences on the Social Construction of Gender’ for the courses Thinking Sociologically at Algoma University and the English Applied to Crime and Police Investigation course at Universitat Jaume I.

This first critical education module used intersectional decolonial frameworks to critically develop discussions of the process and outcomes. In this approach, we used intersectionality to understand how multiple forms of inequality or disadvantage sometimes compound themselves and create obstacles that often are not understood among conventional ways of thinking (Crenshaw, 1991). This analysis also guided the activities and methodology in the classroom. As instructors, we agreed that an intersectional analysis was important to teach from a decolonizing lens that, according to Tuhiwai (2012, p. 98), involves “a long-term process involving the bureaucratic, cultural, linguistic, and psychological divesting of colonial power.” The combination of these perspectives provided the course directors with an intersectional decolonial framework to collaboratively develop and improve the module. This module sought to unveil power structures while simultaneously making space for Indigenous and other voices from the margins (Hooks, 1984). The dynamic of sharing power and centering marginalized perspectives became the foundation for future collaboration and innovation of the refined COIL project. This framework sought to unveil uneven power dynamics in the classroom and institutional contexts. At the end of this experience, a joint reflection on the different engagement processes in the course activities and content led to improving the next iteration of the COIL module focused on the Social Construction of the Environment and linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The refined material addressed both synchronous and asynchronous online learning and teaching units.).

3.2 Year 2: refining our power dynamics and approach to the SDGs from an equity lens

A critical examination of the social relations of diverse communities and the meanings derived from the construction of the environment provided a foundation for the critique of ecological problems while emphasizing movements for environmental justice in the context of social and environmental justice. Given our reflection and engagement with systems thinking, the course directors refined the course and centered an Indigenous framework to create the course and make connections holistically. Dr. Jimenez-Estrada’s approach to studying the environment from her position as an Indigenous Maya Achi scholar provided the framework to weave the relationship between environmental problems and marginalization/exclusion, racial and gender discrimination while focusing on resistance and direct action within an inter-disciplinary and experiential framework. Drawing on the expertise of the two instructors, the course utilized an Indigenous and critical/ecological thought framework unveiling the legal implications of these issues. To demonstrate the successful achievement of the learning objectives the course’s final project focused on a comparative exercise between the two regions (Canada and Spain). The final collaborative student project focused on barriers and opportunities to achieve the United Nations Development Goals, specifically Goal 11 - Sustainable Cities and Actions, Goal 13, Climate Action, and Goal 16 - Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, placing the emphasis on Goal 13.

In Canada, the course Environmental Sociology, a third-year undergraduate course provided the opportunity for students to learn about the social construction of the environment. Students learned about the environmental justice movement and Indigenous perspectives as drivers to take action to achieve the SDGs. In Spain, the course English Applied to Crime and Police Investigation seeks to make students aware of the importance of language learning for communication and professional development. The course aims to improve the students’ linguistic resources in the English language and uses language learning as an instrumental competence to achieve different career goals. In this sense, the COIL experience provided an opportunity for students to develop their linguistic competence in working with other students who used English as (one of) their native languages. In doing so, they became aware of those aspects of the language where they lacked knowledge or confidence and found an opportunity to improve those areas. One such area was for instance the ability to negotiate in a foreign language. The English subject is also concerned with improving the student’s knowledge of issues relevant to the degree in Criminology and Security, ensuring that they will be able to manage material in English dealing with such key topics. The intersection between gender/crime and sociology/crime led to exploring environmental criminology, all key issues in the Criminology degree. Students participate in other subjects dealing with the topic as well as formative courses and conferences with the participation of social agents (such as the National Police, Guardia Civil, and the Conselleria de Justicia, Interior y Administración Pública).

3.3 Year 3: sustainability and beyond: students’ motivation and international exchange

Building from the second year of the Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) practice, the third year focused on a comparative exercise between the two regions (Canada and Spain) about the barriers and opportunities to achieve the 17 United Nations Development Goals (SDGs). The instructors facilitated a process whereby the students chose to work on the SDG that interested them the most. Selecting an SDG to focus on motivated them to learn more about the goal and how the two regions approached the aims of that goal. Critically thinking of their student realities and how to act for change became central to the course dynamics to develop an expanded concept of socio-ecological justice.

The third year fostered the students’ ability to identify the relationships between ecological, economic, political, and social problems and how these play out for under-represented groups comparatively between Canada and Spain and specifically for Indigenous Peoples. Working with all the SDGs in the different groups allowed students to make connections between the goals and contribute to the work of other groups. The group work also facilitated an understanding of social issues and interactions between humans and nature. The group addressed many environmental issues, mainly environmental racism and justice in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to the SDG that each small group worked in. Finally, students were encouraged to identify local actions demonstrating community engagement in the context of the UN SDGs.

4 Institutional context and combining pedagogical tools

Universitat Jaume I (UJI), located in the city of Castelló de la Plana. The university was founded in 1991 and has approximately 14,000 students. It has four faculties located in a single campus. Since its beginnings, the activity of the Universitat Jaume I has been marked by social commitment, respect for diversity, equality between men and women, the improvement and protection of the environment, and work for peace through cooperation and solidarity actions. The UJI has its own ambassadors’ network where voluntary students, staff, and teachers contribute to positioning the UJI on a global scale and to establish strategic alliances in a commitment to internationalization based on people, studies, research and international promotion. The university has a Diversity and Disabilities Unit that develops the Plan for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities at the UJI. There is a Violet-Rainbow Point on campus, an instrument promoted by the Ministry of Equality to involve society in the fight against gender violence. The service offers information, guidance, and psychological and legal advice on sexual harassment, sexist violence, and affective-sexual and gender diversity, raising awareness about the need to seek solutions to social problems such as sexism or LGTBI-phobia.

Algoma University is a Canadian public university with three campuses. Its main campus is in the city of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. It is located on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabek Nation and Métis homelands and on the site of the former Shingwauk Residential School, where Indigenous children were taken from their families through government policy lasting from 1871 to 1996 to forcibly strip them of their Indigenous identity and assimilate them into white, Euro-Canadian society (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015; Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2002). Given this historical context, the university takes it as its Special Mission to be a teaching-oriented university and cultivate cross-cultural learning between Indigenous and other communities.

In line with its Special Mission, Algoma University is committed to honoring truth and reconciliation, creating safety for its community members, and increasing equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) for all its students and employees. This commitment permeates across all departments at AU and is foundational to the course selected for the COIL experience - the second-year course titled Thinking Sociologically.

Together, SOCI 2016 Thinking Sociologically and CS2008 English Applied to Crime and Police Investigation served as the foundation for the COIL course that sought to promote the following objectives:

– Active citizenship of a person, who can realize and identify universal human values.

– Appreciation of diverse worldviews, based on dialogues between cultures and personal realization of the person’s role in a diverse multicultural society

– Critical awareness of acceptable behavior in a multicultural society

– Instill cross-cultural communication with other people, to arrive at mutual understanding

– Ability to engage with students from a culture outside of one’s self via written and oral communication for self-development in the multicultural and multilingual work environment

– Knowledge of sociocultural specifics of a country and the diverse communities inhabiting it

– Develop applied skills in differentiating cultures and pointing out similarities and

– differences amongst the diverse groups of people living in each country

5 Theoretical framework

Critical pedagogy stresses the symbolic importance of knowledge, language, and social action within educational practices and the material and cultural impact on disadvantaged and privileged populations. Its general goal is to change educational practices to represent diverse voices, perspectives, and experiences - not only of those with resources and power (Giroux, 2020). From this perspective, education is proposed as a liberating experience, designed to spur students to seek social and economic justice. This experience is in flux and needs a critical assessment of each student’s social location and how these interlocking and intersecting identities give rise to unique learning experiences. Thus, intersectionality as a theory (Crenshaw, 1989; Collins, 2019) provides a lens to raise awareness of these differences and how instructors create meaningful opportunities for all students to participate and actively engage in learning.

Within the framework of Critical Pedagogy in a COIL experience, communication for all played an important role. COIL projects provide excellent communication and information-sharing opportunities where students from different cultures interact in an intercultural, international setting. Key to achieving this goal is providing students with information and exercises that unveil the power differences in society due to unequal benefits and opportunities for social actors. Exercises that challenge students to think outside of their own experiences to develop empathy and understanding for others focus on analyzing privilege, bias and stereotyping. One lesson focused on the aforementioned, in what constitutes thinking sociologically (Mills, 1959) to enact change. In their volume SDG18 Communication for all, Servaes and Yusha’u (2023) and contributors in the different chapters express the need to include one new goal focused on the role of communication in achieving the SDGs. As suggested in the different chapters, achieving the SDGs without seeing the role of communication in the different areas of development is an impossible task. In this sense, access to accurate information and knowledge or access to communication is a right that needs to be balanced among the global population. This lack of access to communication impedes (Vargas and Lee, 2023:26) “full participation in development processes, especially for the poorest and most marginalized people in society.” Vargas and Lee talk for instance about “communication and information poverty” about SDG5 (Gender Equality) and the way women are under and mis-represented in media content. Further examples they provide are the violence against women journalists exercising their right to communicate and express opinion and the need for women’s equal access to and participation in decision making and leadership in political, economic and public life. Facilitating the use of communication technologies to promote the empowerment of women as well as the importance of visualizing the triangle between communication, gender and development are essential to promote gender equality. We would like to add here that these and other communication rights need to be considered regarding communication and the misrepresented LGTBQ + community that is still in need of an informed acknowledgment inside SDG5.

Part of SDG18 Communication for all is Transformative Language for Sustainability (TLS), a learner-oriented language teaching focusing on those language competencies and skills needed to reach SDGs in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) (Maijala et al., 2024). This is further developed in the Linguistic Challenges section in this paper.

6 Discussion - experiences and challenges shaping the course

In the first year, both groups identified the social construction of gender as paramount in understanding the root causes of gender-based violence through discussions of gender identity and expression and the implications for policy and law creation, enforcement, and transparent accountability. These elements led to the construction of the COIL project, where students from both universities were asked to develop a collaborative project that would promote teaching and learning about the issue in each region. Each group presented on a different topic and social identity(ies), leading to a rich and nuanced exposition of lessons learned (see Figure 2).

During the COIL development of the first academic year, the sociological perspective of the construction of gender made us aware of how it related to SDGs from a holistic perspective, and how dealing with the COIL project having the SDG as a reference would create opportunities for critical thinking and develop students’ ability to relate the impacts of one goal on other SDGs. Thus, the second and third-year modules were structured around the SDGs. This space allowed students to show their personal interest in specific goals. Given that the SDGs are interconnected, the module critically emphasized the relationship between one’s lived experiences and how these lead to an individual understanding of issues. The cross-cultural exchanges between students also demonstrated the barriers and opportunities to engage in action to address problems such as climate change and social inequality. The combination of the materials provided, the pedagogical approaches and different voices teaching the material provided real examples of how the wider community and society can address sustainability. Notwithstanding, there were challenges at the institutional levels that were overcome through constant negotiation between the course directors and amongst the students requiring constant debriefing and improvement of the course itself.

Intercultural competence is understood as “behaving and communicating effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations” (Deardorff, 2006). This competence was developed in the collaborative group work because of the nature of COIL. All students had to communicate effectively so that they could understand and produce their final project, and had to understand students in the other university since they worked in mixed university groups. They were always discussing COIL contents from the perspective of two different universities and countries, which fostered communication in intercultural contexts. For all the projects students were requested to show and contrast sociocultural differences between Canada and Spain in the issues they presented. Thus, intercultural competence at a conceptual level was always part of the task construct. For example, during the second-year students had to discuss and compare the similarities between Indigenous Peoples in Canada and Roma groups in Spain. This exercise sought to highlight the unique experiences that demonstrate how both groups are disproportionately impacted by environmental injustice and racism. Additionally, devising solutions to these urgent societal issues requires awareness, education and an open mind to see how systemic issues are created by societies, and therefore, can be undone through movements focused on social and policy changes. Working across cultural and linguistic differences requires a skill set that can enhance students’ abilities to understand and interact with each other across differences. The instructors envisioned intercultural competence as a set of tools that could bring students together to understand the historical nature of inequities. However, intercultural communication or learning how to engage across differences is complex and cannot be fully achieved in a 5-week module. Moreover, as suggested by Zotzmann (2015) intercultural competence is not something that people are or have but something they do, and the outcomes of intercultural learning are basically performance-based. In this sense, it was impossible to reach all students’ interactions in the many different topics dealt with. That would imply recording students’ interaction, and they would not be comparable across years and within the same year because each group would show different problems, challenges and achievements.

There are, however, some indicators that reveal that intercultural competence is activated or needs to be activated. Instances of intercultural competence development activation could happen when students need to contrast laws in Canada and Spain in order to develop their projects, or when they learn while working on their projects about extreme weather events and how they are tackled by different security forces in their countries of origin as well as the opinion they may have in the different actions that may be taken regarding this and any other issues. An important part of our methodology was material selection and the design of task instructions to engage with intercultural values in the classroom. Task instructions could be changed from 1 year to another when student feedback or task outcomes revealed that they had not been clear enough or needed simplification or adaptations. Task instructions were formulated to guide students into the co-construction of meanings.

On the other hand, there is a difference between lower order achievements and higher order achievements. While conceptual level achievements are easy to assess, being able to understand and critically interpret intercultural situations in a mixed level class with students of different provenance and sensibilities is an enormous challenge (these are higher order achievements). In this COIL environment, the rubrics used support acknowledging whether the students show general understanding of the topic and whether there are signs that they gained a more in-depth knowledge or were able to identify possible actions to take to solve SDG problems.

An important teaching moment arose during students’ small group discussions and collaborative projects, where students demonstrated different levels of acceptance to using pejorative language and expressions detrimental to gender diverse groups. This experience demonstrated the importance of developing intercultural communication and cultural safety through learning about the context and meaning of words in the different languages and cultural contexts. In line with linguistic relativity (Lucy, 1997; Batisti, 2024) suggesting that language shapes thought and therefore, how one thinks (Boroditsky, 2011), the instructors became aware of the differences and level of comfort with which Spanish speakers used pejorative language targeting non-binary gender identities. This experience demonstrated the need to highlight how the choice of words one uses reveals a person’s biases (Fillmore, 1985; Hart, 2023; Searle, 2013; Silvestre-López et al., 2023) and the cultural norms of each region, which may not be accepted or legal in another region. Students had the opportunity to unpack and reflect upon why students from Canada reacted with discomfort when students from Spain use this type of language. It became imperative to highlight what is appropriate and does not breach human rights in each country. With this in mind, establishing the legal imperatives and responsibilities to respecting diverse gender identities became a central topic that allowed students in Spain to understand how their use of offensive and gendered language was not just politically incorrect. It also breached human rights. In this case, teachers had the opportunity to explain in class and elaborate ad hoc material giving recommendations for the use of gender terms, pronouns and other key concepts in their final project presentations.

7 Challenges and opportunities: substantive and technical challenges

This section describes the different challenges that were faced before and while implementing the COIL exchange. These are divided into substantive challenges linguistic challenges and technical challenges.

7.1 Substantive challenges

Courses are meant to provide a storyline, and is a continuum of skills and information learned and built upon in an academic program. The challenges of COIL programming mainly stem from three basic factors: instructors need time to get to know one another in the context of their courses, their pedagogical approaches based on student profiles, and institutional limitations to class coordination.

Couched within understanding pedagogical choices is the need to understand each instructor’s aims and working methods for their individual courses. For this to successfully happen, both need to find a shared way to convey information that synthesizes relevant information for each of the two courses while keeping true to the overall educational objectives and outcomes required by their academic programs. This includes meeting and not exceeding the in-class time requirements for which some students struggle with given extracurricular activities of paid and non-paid work, as well as travel time to their places of employment and origin. This issue became more evident as some of the common times for the groups to come together and work synchronously on their COIL project was the weekend, however, it was not possible for those students with weekend part-time jobs and/or those with limited to no access to the internet outside of the institution. All of these disparities need to be accounted for in planning a cohort of students that will successfully engage in and complete the requirements of this program.

Pedagogical approaches were based on the student profiles and time availability given their course schedules. Balancing the needs vs approaches of the different contexts, coupled with challenges in intercultural communication impacted the learning environment and the pace of learning, particularly in relation to the number of courses each student was taking, and the different scheduling requirements of each institution (UJI worked mostly from a 9 to 7 approach while AU students had more flexibility with their course schedules). Given that the only solution was to schedule the courses asynchronously for 5 meeting dates proved challenging due to the 6-h time difference.

Another key element was to find an assessment method that worked for both courses. The reality for both of these courses being that strict rubrics had to be developed in order to clearly demonstrate expectations and ways to successfully engage with the materials as well as with the outcomes.

An assessment rubric was developed to assess the course’s general achievements. In order to design this rubric, we revised all the UNESCO framework (2017) Education for Sustainable Development Goals: learning objectives. Cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioral learning objectives were selected and slightly modified to fit the course. These were implemented in a simple rubric where teachers assessed whether students had achieved the learning outcomes or not. This general assessment rubric is suitable for COIL because it is easier to implement in the two different groups than a more intricate assessment tool. The COIL experience itself is quite time-consuming and complex and having clear and direct assessment is a good evaluation choice. In order to align with the ESD framework, we chose three different types of objectives related to cognitive, socioemotional and behavioral achievements. Further improvement of this rubric would be to describe different levels at which the learning objectives are accomplished. This would entail thinking about the different SDGs in relation to each element so that the rubric can be more precise and developing descriptors that relate to different levels of achievement.

This rubric was complemented with a group work rubric where the essentials of collaborative work were taken into consideration. The rubric was employed for the assessment of the final group presentation that all groups engaged in. For the purpose of this presentation, a second collaborative work rubric was created in which the following criteria were assessed: communication skills, topic understanding, identifying the goal within the SDGs and the ability to address specific actions related to the goal. Thus, students were required to summarize their goal and address related problems in a clear and structured way. It was important that to bear in mind the relation to the course content regarding Indigenous Ecological theory and to adopt a critical perspective in the presentations. Students were asked to specify short or long-term actions, and to reflect on the impact these may have.

7.2 Linguistic challenges

A final and important element that is seldom discussed is the need to recognize the added task of working with students with different language proficiency levels. This is also a disparity for students in the sense that having English set as the language of instruction may disadvantage students receiving instruction in a language other than their primary language.

In a university setting, different approaches to integrating a foreign language into the content subject classroom (usually English) has been a common practice in European universities. This is an attempt to foster internationalization and may combine with foreign language subjects. In this regard, three noteworthy methods are CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning), CBI (Content Based Instruction) and English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI).

The Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach implies the acquisition of curricular contents through a target language (Carrió-Pastor, 2019). For CLIL practitioner’s disciplinary knowledge and communicative skills in the target language can be acquired simultaneously. English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) is an approach adopted by educational institutions (Morell et al., 2022) offering courses delivered in English (language learning is not a priority in EMI, the focus is on content).

While in CLIL classrooms the aim is teaching both language and the subject content, in EMI university level classrooms the aim is to teach the subject while speaking English. EMI is “The use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions in which the majority of the population’s first language is not English” (Dearden, 2014).

In Content Based Instruction (CBI), the instruction of a content subject takes place in a foreign language and places emphasis on the learning of meaningful content while developing communicative skills in the target language (Lightbown, 2014).

A COIL experience may prove more effective as a tool to promote internalization, both from a cultural and a linguistic point of view. What differentiates COIL from CLIL, CBI, and EMI is that participants in the classroom come from two or more different sociocultural realities and that the language that is chosen to communicate and interact in the classroom may be a mother or second language for part of the group and a foreign language for the other part. In this sense, what is relevant in COIL from a linguistic perspective is that there will be two linguistic challenges:

– For speakers of English as a second or mother language, the challenge is to be precise and simple enough for the rest of the group to understand. They will also need to develop their linguistic competence to rephrase their contributions in the different conversations and shared written texts. This group of students will practice synthesizing and paraphrasing skills.

– For speakers of English as a foreign language, the experience will be similar to CLIL, CBI, and EMI but with the added value that their interaction will be with native and other speakers of English, thus providing an opportunity to improve their proficiency level, particularly at a communicative level. They will need to make an effort to understand their partners in a context where only English is used, not their mother tongue. They will also have to become aware of cultural differences and backgrounds and widen their perspectives of the world and the different views of sustainability in the process.

As opposed to CLIL, CBI, and EMI, one key issue in COIL is collaborative work - which demands understanding each other and reaching agreements on the proposed tasks. In this regard, a third and fourth linguistic challenge arises:

– Both participants will need to develop their negotiation skills (some will focus on how to negotiate with the other culture, some on how to express what they want in English), and both will need to understand the sociocultural demands of the other side.

– Participants will have to work on the conceptualization of the main ideas they worked with in the different SDGs. Conceptualization is an important component of the Transformative Language for Sustainability (TLS) framework and relates to various concepts, terms and perspectives. It also includes social and individual perspectives.

It seems relevant to pay attention to the different linguistic challenges in a COIL group as well as to anticipate possible student needs in this context. It entails preparing relevant classroom and/or study materials that each of the linguistic groups may need for better interaction. Asking first-language speakers to develop the above-mentioned skills is also relevant to have a balanced linguistic demand on both sides.

This COIL approach to language teaching and language use was further enhanced by following the Transformative Language for Sustainability (TLS) approach (Maijala et al., 2024). TLS is a methodology promoted by the Ethical and Sustainable Language Teaching project [Eettisesti kestävä kielten opetus (EKKO)] in the University of Turku. It integrates transformation-oriented Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) into language teaching using linguistic and cultural features of sustainability that are key in language teaching and learning. TSL studies how the principles of ethics and sustainability can be built in language teaching. Its goal is “to help teachers to find new ways to combine education for sustainable development (ESD) with language teaching.”1

TLS has different facets, one of such facets is conceptualization of terms, that is, the importance to fully understand concepts and ideas, such as sustainability and its different facets. In this sense, it is important that our students understand the meaning of sustainability terms in relation to the SDGs and how these terms are used in different contexts by different agents.

The role of language and communication is in fact a central issue in fostering SDGs. The ability to understand the whole sustainability framework proposed in the UN SDGs is an important educational asset. Access to sustainability concepts and framework contents is a key educational goal and an important factor that creates differences in how countries may access or relate to sustainability ideas and proposals. For this reason, Nayak and Raval (2024) propose that language and communication should become SDG18. As they suggest (2024: 1782): “strong command of the English language facilitates linguistic empowerment, which is a fundamental component of global involvement. Because English is the lingua franca in international commerce, science, and diplomacy, people from all over the globe can participate in collaborative activities and contribute to the discussion on sustainability when they have a strong command of the language”. This is also the line in proposals dealing with foreign language learning (De la Fuente, 2022).

One way to overcome linguistic challenges was to explicitly explain to students what they had to achieve from a linguistic point of view depending on their language proficiency level. For instance, in negotiations about how to address their SDG, proficient students were given instructions on how to reformulate ideas and how to synthesize information in a comprehensible way. Less proficient students were provided guidelines that helped them to ask for clarification and to detect keywords and linking words that guide discourse.

Thus, linguistic challenges are twofold, on the one hand, they are related to language proficiency in a foreign language and developing communicative skills in the mother and foreign language. This means working with a mixed-ability classroom regarding language of instruction. It also means that all students are linguistically challenged to communicate effectively to reach a consensus. On the other hand, teaching language for sustainability demands that the teachers select the specific language that is being used, paying close attention to word choice and appropriate texts that are simultaneously informative and understandable for all students.

7.3 Technical challenges

Among the technical challenges that may be found in a COIL project, the following issues tend to be recurrent in most COIL encounters:

– Time zone differences and ensuring class schedules matched for synchronous sessions

– Finding classrooms with appropriate technology and readily accessible technical support to address ongoing internet and other issues

– Creating dedicated Moodles at each university given the barriers to create one single student repository for both universities. This required ongoing technical assistance with the different Moodle for the different tasks

– Ensuring students acquired the technical knowledge of tools to facilitate synchronous and asynchronous collaboration (sending calendar invites, working with online whiteboards, setting up effective working documents where everyone can see the progression of the work and identify whose contributions belong to whom)

– Ongoing support based on students’ different language proficiency levels (native/non-native)

– Leveling the academic and critical skills of students who were in different years (some students were taking a first-year course and others a second or third-year course)

The first three aspects are institutional and need to be dealt with before the actual teaching sessions begin. This implies sufficient time and coordination supports from the different administrative services to reach the desired outcome. The last three technical challenges are closely related to the methodology proposed for the different sessions. There were synchronous whole-group sessions and synchronous sub-group sessions. Thus, using synchronous communication with the whole group effectively introduced the modules. Here, the course instructors provided the theoretical and technical grounds to develop the session. In these synchronous sessions, the instructors focused on sharing information while assigning specific tasks for small group work. Therefore, the demands on the students were lower to make communication easier. In the synchronous sessions, students worked in small groups to accomplish the required collaborative tasks. Asynchronous sessions were employed to complete the assigned tasks when all students knew their roles in the group. Understanding their specific tasks contributed to the completion of small group assignments. Finally, leveling the academic skills of students to meet the course objectives required negotiation between the course instructors. The course at UJI was a first-year course while the courses at Algoma were second or third-year level courses that required demonstration or mastering of key program outcomes such as critical thinking and theoretical praxis.

7.4 Assessment challenges and learning opportunities

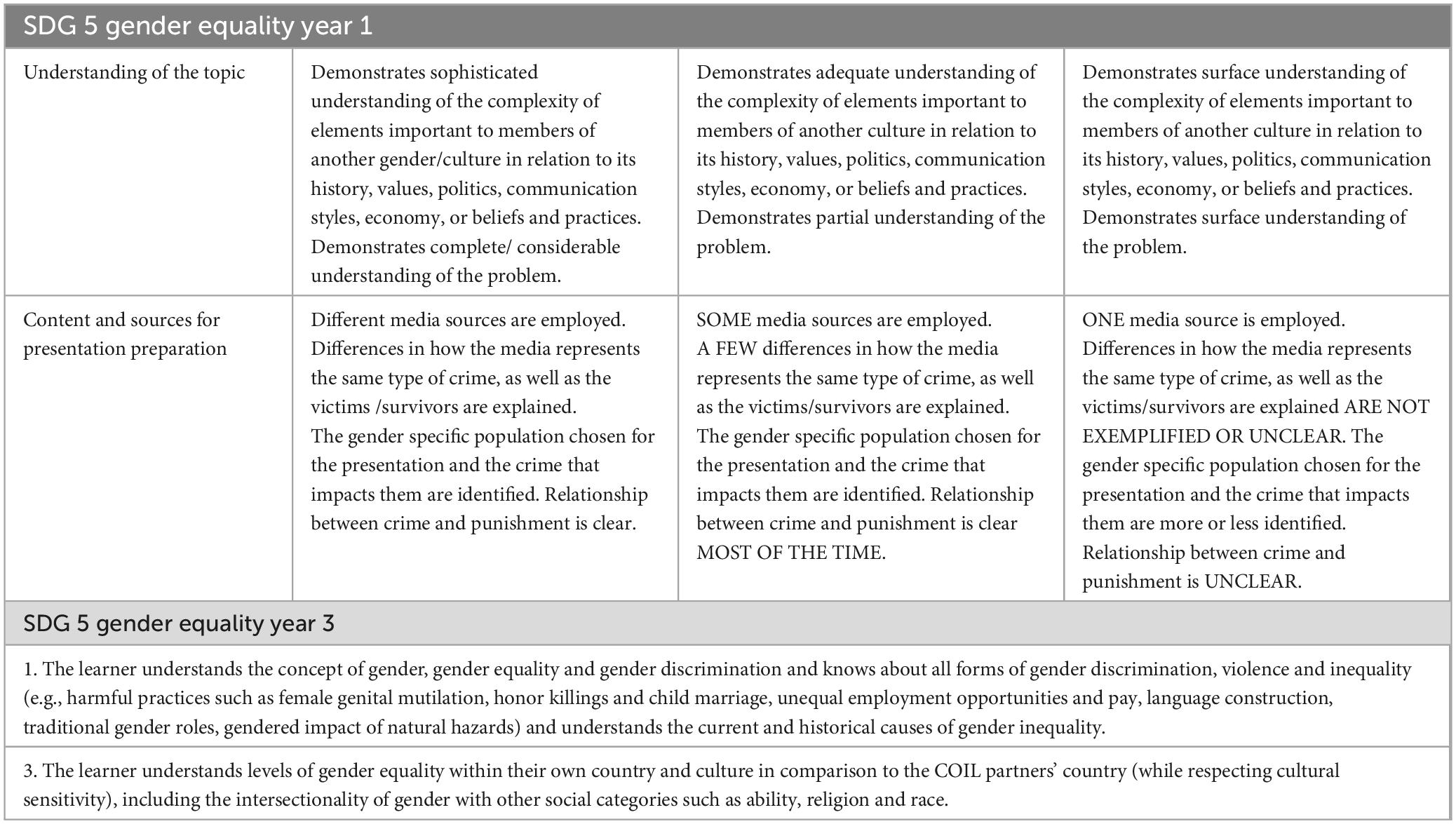

Evaluation of students’ outcomes was also a challenging point due to the different student backgrounds in terms of English language proficiency levels, the degree they were studying, year of study in the degree, and different sociocultural backgrounds. This section shows how rubrics were developed and adapted throughout the years. In Table 1 comparison is exemplified in relation to cognitive learning objectives. Years 1 and 2 focused on one SDG (SDG5 and SDG13 respectively) while year 3 focused on all SDGs. As can be observed, the first rubric for SDG 5 develops topic understanding, content and sources used to document the learner’s projects. The challenge in year 3 was to synthesize rubrics to common features for all SDGs. In order to do so, competence descriptors were taken and slightly adapted from the UN Education for Sustainable Goals Learning Objectives (UNESCO, 2017; Ahmad et al., 2023). Thus, during the third year we used, for instance, the first cognitive learning goal for all SDGs (shown as 1 in Table 1 in the rubric). Although this is a very general descriptor it was useful to unify a general rubric for all students and goals. The rest of the UN cognitive learning objectives were then used as secondary assessment references to find out if the group had taken the cognitive learning objectives more in depth. In the case of the group working SDG5 for example, descriptor 3 shown in the table fits the project presented by the students. Another challenge in the implementation of UN learning objectives was how to create tasks that could be used to measure behavior. How could we evaluate students’ ability to change their behavior in relation to their personal activities? Supplementary Appendix 1 shows an instance of a class activity designed with that aim in mind.

Table 1. Assessment development in rubrics for SDG5 gender equality (cognitive learning objectives).

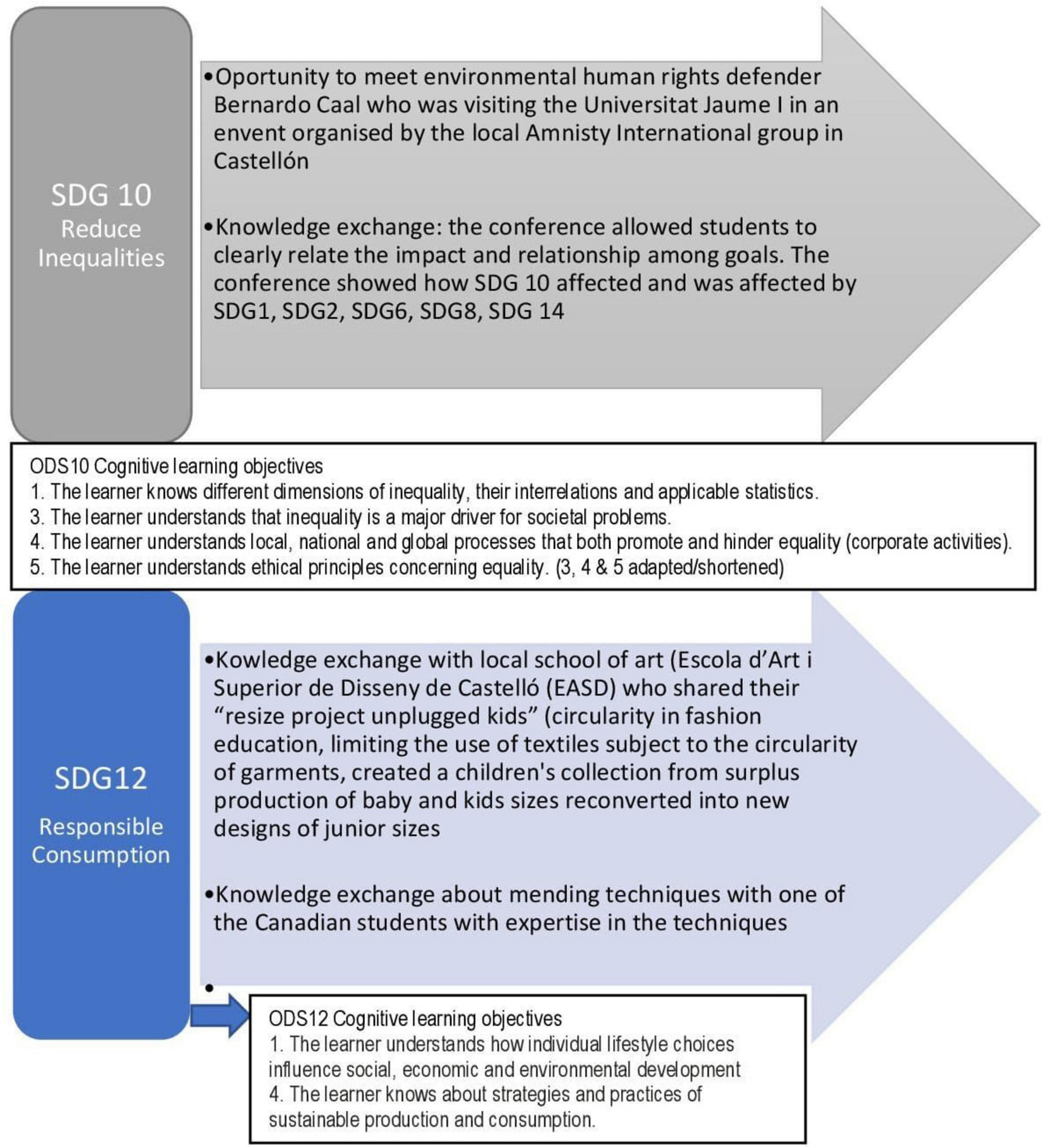

Another aspect of the COIL project that was challenging was to provide as many learning opportunities as possible in relation to the SDGs. Figure 3 illustrates opportunities in relation to SDG10 and SDG12.

8 Limitations of the study

The content of this study has to be seen in the light of some limitations such as the lack of qualitative student data analysis. Although each teacher as participant brought their own experiences and worldview to the study, the possibility to include student data and analysis in future COIL research will shed new light on our findings and show different dimensions of the COIL practice. Future research could include data from students’ surveys analyzing their learning experiences and the contribution of students to their groups and passed through an institutional REB process to address the ethical considerations of working across different cultures, languages and institutional procedures.

Another limitation of the study is the fact that it includes the perspective of one of the agents involved in the COIL module development. Alternatives to this limitation are (1) including the institutional perspective based on educational agents collaborating in COIL (2) including student consent informed data analysis (3) students as member checking participation that may be complemented by (4) teacher as part of the member checking process where the teacher is an external observer.

This study has intended to reflect on the teachers’ experience alone, based on their own collaboration to design a COIL course, and how their course progressed along the years. Interaction with the students is of course an essential part of the experience and as such, and the lack of student data is a drawback in the present study. After careful consideration of implications of collecting student data in similar projects, we will consider inviting students to co-author in future studies, since they are an active part of the COIL investigation.

9 Concluding thoughts and recommendations

This paper has described an example of Collaborative Online International Learning in a joint program between Algoma University and Universitat Jaume I. The COIL exchange sought to transform the students’ learning process by creating a sustainability mindset that facilitated learning about the SDGs critically. Aligning students’ experiences with SDG content and sharing these experiences between two different social and cultural contexts proved to be an effective learning approach.

As noted in our discussion, our collaboration process highlighted the institutional challenges and opportunities that need to be improved. Some examples include providing the appropriate time to develop collaborative modules that meet the learner’s needs while meeting the learning objectives and outcomes of each course in their respective academic programs and appropriate to their level of study. Some recommendations for instructors and institutions hoping to engage in COIL and support the course directors in a meaningful way include:

– Recognition that collaborative modules or work require more time and work to develop and implement

– Administrative support to develop and provide one common student repository system like Moodle to students in both institutions

– Scheduling of courses containing COIL should align to allow for synchronous teaching at reasonable times

– Language instruction for students in Canada, so that they also experience the challenges of speaking in a second language and develop or refine their intercultural communication skills

– Academic leveling for all students requires an understanding of the institutional culture of each institution as well as the differences in pedagogical approaches and class management strategies

Finally, we would like to emphasize that COIL was originally developed as a way to provide global and applied learning mobility opportunities for students and faculty during the pandemic, however, considerations for continuing it can provide a more sustainable way to provide the experience while lessening our carbon footprint. We propose that COIL experiences should be formally recognized for both students and teachers. For teachers, it is an immense training (Lozano-García et al., 2008) and learning opportunity that enhances their teaching abilities and innovation skills. For students, participating in COIL should be recognized as part of their exchange program curriculum. Funding opportunities for faculty exchanges should be guaranteed so that students can meet the instructors and students of each institution.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MC-C: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. VJ-E: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research conducted in this article is part of the Universitat Jaume I Education and Innovation Research Project: 52905/24 Incorporating Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge that funding provided by the Government of Canada’s Global Skills Opportunities Fund made travel from Canada to Spain possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1520859/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2002). Research series. Available at: http://www.ahf.ca/publications/research-series (December 18, 2024).

Ahmad, N., Toro-Troconis, M., Ibahrine, M., Armour, R., Tait, V., Reedy, K., et al. (2023). CoDesignS education for sustainable development: a framework for embedding education for sustainable development in curriculum design. Sustainability 15:16460. doi: 10.3390/su152316460

Amorós Molina, Á, Helldén, D., Alfvén, T., Niemi, M., Leander, K., Nordenstedt, H., et al. (2023). Integrating the United Nations sustainable development goals into higher education globally: a scoping review. Glob. Health Action 16:2190649. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2023.2190649

Batisti, F. (2024). “Linguistic relativity and gender inclusive language: general remarks upon the debate on Italian,” in Actas del Congreso Relatividad Lingüística y Filosofía Experimental, eds P. Hernando Carrera and C. G. Llorente (Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid), 40–45.

Borger, J. G. (2022). Getting to the CoRe of collaborative online international learning (COIL). Front. Educ. 7:987289. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.987289

Boroditsky, L. (2011). How language shapes thought. Sci. Am. 304, 62–65. doi: 10.1006/cogp.2001.0748

Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (2019). “The implementation of content and language integrated learning in Spain: Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language Education Curriculum Design, eds P. Mickan and I. Wallace (Milton Park: Routledge), 77–89. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, doi: 10.2307/j.ctv11hpkdj

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Univ. Chicago Legal Forum 1989, 139–167. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198782063.003.0016

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1300.

De la Fuente, M. J. (2022). Education for Sustainable Development in Foreign Language Learning: Content-Based Instruction in College-Level Curricula. Milton Park: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Dearden, J. (2014). English as a Medium of Instruction-A Growing Global Phenomenon. London: British Council.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 10, 241–266. doi: 10.1177/1028315306287002

Didham, R. J., and Ofei-Manu, P. (2018). “Advancing policy to achieve quality education for sustainable development,” in Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development, eds J. Leicht, J. Heiss, and W. J. Byun (Paris: UNESCO), 87–110.

Foley, H. (2021). Education for sustainable development barriers. J. Sustain. Dev. 14, 52–59. doi: 10.1186/s42055-022-00050-3

Guth, S. (2013). The COIL Institute for Globally Networked Learning in Humanities. Available online at: http://coil.suny.edu/sites/default/files/case_study_report.pdf (accessed September, 12, 2024).

Hart, C. (2023). Frames, framing and framing effects in cognitive CDA. Discourse Stud. 25, 247–258. doi: 10.1177/1461445623115507

Huang, Y. S., Harvey, B., and Asghar, A. (2021). Bureaucratic exercise? Education for sustainable development in Taiwan through the stories of policy implementers. Environ. Educ. Res. 27, 1099–1114.

Kučerová, I. (2023). Benefits and challenges of conducting a collaborative online international learning class (COIL). Int. J. Stud. Educ. 5, 193–212. doi: 10.46328/ijonse.110

Lozano-García, F. J., Gándara, G., Perrni, O., Manzano, M., Elia Hernández, D., and Huisingh, D. (2008). Capacity building: a course on sustainable development to educate the educators. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 9, 257–281.

Lucy, J. A. (1997). Linguistic relativity. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 26, 291–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.291

Maijala, M., Gericke, N., Kuusalu, S. R., Heikkola, L. M., Mutta, M., Mäntylä, K., et al. (2024). Conceptualising transformative language teaching for sustainability and why it is needed. Environ. Educ. Res. 30, 377–396.

Morell, T., Beltrán-Palanques, V., and Norte, N. (2022). A multimodal analysis of pair work engagement episodes: implications for EMI lecturer training. J. English Acad. Purposes 58, 101124.

Nayak, P. S., and Raval, R. J. (2024). Fostering global sustainability: the role of English language in development. Educ. Administr. Theory Pract. 30, 1782–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102353

Niitsu, K., Kondo, A., Hua, J., and Dyba, N. A. (2023). A case report of collaborative online international learning in nursing and health studies between the United States and Japan. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 44, 196–197.

Pesanavi, V. T., and Lupele, C. (2018). “Accelerating sustainable solutions at the local level,” in Issues and trends in Education for Sustainable Development, (Paris: UNESCO), 177.

Qablan, A. (2018). “Building capacities of educators and trainers,” in Issues and trends in Education for Sustainable Development, eds J. Leicht, J. Heiss, and W. J. Byun (Paris: UNESCO), 133–156.

Rubin, J. (2015). Faculty Guide for Collaborative Online International Learning Course Development. Available online at: http://www.ufic.ufl.edu/UAP/Forms/COIL_guide.pdf (accessed March 27, 2024).

Searle, J. R. (2013). “Truth and speech acts, studies in the philosophy of language,” in Truth and Speech Acts: Studies in the Philosophy of Language, eds D. Greimann and G. Siegwart (London: Routledge), 61–89. doi: 10.4324/9780203940310

Servaes, J., and Yusha’u, M. J. (eds.). (2023). SDG18 communication for all, Volume 2: Regional perspectives and special cases. Springer Nature.

Silvestre-López, A. J., Pinazo, D., and Barrós-Lorcertales, A. (2023). Metaphor can influence meta-thinking and affective levels in guided meditation. Curr. Psychol. 42, 3617–3629.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Canada’s Residential Schools: The legacy. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queens University Press.

Ulmer, J. B., Kuby, C. R., and Christ, R. C. (2020). What do pedagogies produce? Thinking/teaching qualitative inquiry. Qualit. Inquiry 26, 3–12. doi: 10.1177/1077800419869961

UNESCO (2014). Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO. doi: 10.54675/CGBA9153

Vargas, L., and Lee, P. (2023). “Communication and information poverty in the context of the sustainable development goals (SDGs): A case for SDG 18–communication for all,” in SDG18 Communication for All. Sustainable development goals Series, Vol. 1, eds J. Servaes and M. J. Yusha’u (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan). doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-19142-8_2

Žalėnienė, I., and Pereira, P. (2021). Higher education for sustainability: a global perspective. Geogr. Sustain. 2, 99–106.

Keywords: collaborative work, Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), 21st century skills, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Education For Sustainable Development (ESD), Transformative Language for Sustainability (TLS)

Citation: Campoy-Cubillo MC and Jimenez-Estrada V (2025) A critical approach to SDGs through Collaborative Online International Learning: experiences from Canada and Spain. Front. Educ. 9:1520859. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1520859

Received: 31 October 2024; Accepted: 27 December 2024;

Published: 15 January 2025.

Edited by:

Mayra Urrea-Solano, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Noelia Santamaría-Cárdaba, University of Valladolid, SpainJessica Harris, State University of New York at Oswego, United States

Copyright © 2025 Campoy-Cubillo and Jimenez-Estrada. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vivian Jimenez-Estrada, dml2aWFuLmppbWVuZXotZXN0cmFkYUBhbGdvbWF1LmNh; Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo, Y2FtcG95QHVqaS5lcw==

Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo

Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo Vivian Jimenez-Estrada2*

Vivian Jimenez-Estrada2*