- 1Research Group Value Oriented Professionalization, HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Lectureship Teacher Professionalism, HAN University of Applied Sciences, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 3Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 4Faculty of Educational Sciences, Open University, Heerlen, Netherlands

In this study, a theory synthesis was conducted from a sociocultural perspective to specify the situated processes involved in teacher agency development in the dynamics of educational practices. Agency is closely related to teacher wellbeing and important for teachers to create situations that enable them to act in line with their understanding of what is valuable and feasible. Both the policy landscape and the nature of educational processes, with their emphasis on routines and immediate actions, have had a constraining impact on teacher agency. We specified agency as a situated act that is intertwined with the sociocultural rooted structures and contexts that give rise to it, and in which it is enacted. We unpacked it as a mediating tool through which teachers, both individually and jointly, steer work processes. We brought together valuable insights from previous studies on processes that unfold in educational practices and that are involved in shaping teacher agency. To determine our focus, we conducted interviews with experts in the field of teacher agency research resulting in the study of four research domains. They include sensemaking processes, teacher collaboration processes, professional identity processes and organizational work processes. Based on our analysis, we identified twelve “agentic qualities”. These qualities enable recognizing expressions of agency within these processes. We consider studying the emergence and development of these “agentic qualities” in their interconnectedness as important for understanding the development of teacher agency. Suggestions for future research include empirically studying how these interconnected sociocultural processes are shaped in practice.

1 Introduction

Teachers express agency in their educational practice by directing their attention, making choices, and putting these choices into action. In doing so, they significantly impact on education quality (Van Vijfeijken et al., 2024; Smith, 2017). Teacher agency is related to teacher involvement, wellbeing, and problem-solving capacities (Li and Ruppar, 2020; Priestley et al., 2015). Moreover, through expressing agency, teachers can create situations that enable them to act in line with their insights about what is valuable and attainable for them. Doing so allows them to thrive as professionals (Lau et al., 2022).

In our understanding of teacher agency, we align with the insights of Eteläpelto et al. (2013) who define agency in work contexts as follows: “Agency is practiced when professional subjects and/or communities exert influence, make choices, and take stances on their work and professional identities” (p. 61). These scholars emphasize the importance of acknowledging expressions of agency in relation to the ambitions and ideals that professionals develop within their practices. They underline that how agency is practiced, is intertwined with both their personal characteristics and sociocultural circumstances. We recognize these sociocultural roots of agency both in the biography of teachers and in their practices.

Despite the substantial body of knowledge on how agency can be fostered, many teachers struggle to realize agency in their practices (Bridwell-Mitchell, 2015; Van Leeuwen et al., 2024). From a sociocultural perspective, this is quite understandable, considering the characteristics of agency and the educational practices in which it is expressed. We briefly discuss some of these complexities to clarify the focus of our contribution, and to illustrate its added value.

Agency is not a human characteristic, but a situated act: it is intertwined with the sociocultural rooted structures and contexts that give rise to it, and in which it is enacted (Evans, 2017). This entails that how agency is formed is not only influenced by the teachers' own characteristics—such as their sense of self and skills—and by the circumstances that shape their practices—such as the curriculum design and leadership distribution. It is also formed by how teachers enact their skills, knowledge, and emotions in specific situations to realize their ambitions, and by how the interactions between their actions and material and social circumstances promote or impede that agency.

This situatedness of agency indicates that identifying the factors that promote, and hinder teacher agency is not enough, since teachers' actions are not self-standing or detached from the world. Moreover, identifying agency requires an understanding of the processes that play a role in educational practice; how these processes arise and interact with each other, and how agency is both shaped by and shaping these processes (Edwards et al., 2017). It is therefore important to understand agency as intertwined with those processes. However, teachers do not just react to developments in the workplace that happen to them, but instead engage with reality while authoring and realizing it with others (Hopwood, 2022; Edwards et al., 2017). Indeed, when teachers engage in their work, they shape their practices and themselves through their social and collective contributions. Moreover, we argue that they can transcend situational circumstances through deliberate “ongoing transformative efforts and struggles” (p. 6), “committing to their own visions of the future” (Stetsenko, 2019, p. 10). Consequently, if we want to recognize teacher agency, we need to pay attention to these built-up processes and structures in both the biography of teachers and their practices.

The situatedness of agency also implies that it is ambiguous to pinpoint to what degree individual actions are agentic. This is because of how these actions are experienced as value-laden in the multivoicedness of educational practice (Bakker and Wassink, 2015). Teacher actions initially labeled as “bossy” by some colleagues, might on second thought be reframed as “courageous”. Likewise, a teacher may gradually become aware of certain moral struggles. Therefore, agency cannot be fully captured in a set of qualities or impact variables (Edwards et al., 2017). It only manifests through patterns of interactions within the dynamics of practice, in interactive collective (moral) considerations (Bakker and Wassink, 2015), and in personal interpretations of the actor (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2017).

In addition to these general features of agency, specific characteristics of educational practices can be found that complicate the promotion of teacher agency (Bridwell-Mitchell, 2015; Biesta, 2018). Typically, the social responsibilities that lie within the educational process may discourage experimentation. Moreover, the diversity of wishes and hopes put on education by caretakers, social institutions, and policy makers, puts its aims, processes, and output under a metaphorical magnifying glass (Priestley et al., 2015; Juvonen and Toom, 2023). Consequently, the tightly organized constellation of procedures, schedules, value systems and goals that shape educational settings, may ensure an orderly course of the day, and improve schools' external accountability. But in turn, they may limit opportunities for doubts, alternative insights, and ambitions (Cong-Lem, 2021; Imants and Van der Wal, 2019; Juvonen and Toom, 2023). Also, the current scarcity of available teachers, school leaders and the high turnover rates (UNESCO, 2023), puts pressure on the system and may have a restraining impact on agency development.

The challenges we put forward here, motivated us to relate teacher agency to teacher wellbeing. In line with the World Health Organization (2022), we regard professional wellbeing as the positive emotional state, mental functioning, and sense of purpose that enables professionals to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, and cope with normal stresses. Committing to projects one considers worthwhile, building meaningful relationships, and pursuing personal growth, contributes to professional wellbeing (Dhanabhakyam and Sarath, 2023). We think this striving for wellbeing and the struggle to achieve it, is integrated in a compelling way in Illeris' (2018) theorization of adult professional learning. He points out that teachers strive for mental and bodily balance, by weighing their actions within the tension field between developing their capacities, acquiring sensitivity to what is required of them as teachers, and integrating within their communities (Illeris, 2018). In line with these insights, we argue that agentic actions that enable teachers to thrive are those actions that empower teachers to reconcile discrepancies. These may include discrepancies between their appreciation of developments in their educational practices, their moral values, ambitions, and capacities what they consider necessary to participate within their social practices. For reasons of clarity and brevity, when we refer to “teacher agency” from this point on, we conceptualize it as “agency that enables teachers to thrive in their practices”, in line with this perspective.

The complexity involved in promoting teacher agency and its importance for teacher wellbeing and the attractiveness of the teaching profession, has generated considerable interest in the topic (Cong-Lem, 2021; Li and Ruppar, 2020). While both individual and social, and both temporary and sustainable processes and structures are widely acknowledged as important to promote its development (Cong-Lem, 2021), a disproportionate focus on either of these factors is still a pitfall (Stetsenko, 2019). This is unfortunate since an imbalanced approach may lead to either an undue focus on individual teachers to shape their situations (Evans, 2017; Priestley et al., 2015), or a underestimation of their ability to overcome situational factors (Stetsenko, 2019). Moreover, although the available literature highlights various aspects of agency, and studies how it manifests within different contexts and time frames (Eteläpelto et al., 2013; Li and Ruppar, 2020), an integrated perspective on how situated expressions of teacher agency might take shape within and through the dynamics of educational practices, is missing. This challenged us to analyze theoretical contributions from different research domains to identify these insights and describe them in an integrated way. The purpose of this contribution is to advance our understanding of how expressions of teacher agency can be recognized in the processes that shape educational practice. Our research question is:

What kinds of processes through which agency processes take shape, can we distinguish by integrating insights from literature produced within different research domains about teacher professional functioning?

This question reflects our ambition to gain insight into the processes that guide teachers' actions in the dynamics of their professional practices and understand how agency becomes manifest in these processes. To answer our research question, we consulted diversity of literature sources from various research domains on teacher professional functioning, and connected the insights from these sources to our understanding of teacher agency. We focused on literature that addresses how teachers actively try to establish situations and practices that align with their insights about what is valuable and attainable for them. This focus allows us to contribute to an integrative understanding of expressions of agency that enable teachers to thrive as professionals (Lau et al., 2022).

2 Materials and methods

Our approach aligns with theory synthesis (Jaakkola, 2020). This method can be used to expand existing knowledge through the integration of multiple literature strands, and by connecting them in a new way (Pound and Campbell, 2015). To determine our focus, we conducted interviews with six experts in the field of teacher agency research. We first describe the materials we used, then we discuss our method in more detail and conclude with how we addressed the quality of the study.

2.1 Materials

Semi-structured interviews were used to conduct interviews with the experts. The first author developed the interview guideline with a colleague researcher (referred to in the acknowledgment). The guideline was discussed within the research team and adjusted accordingly. Prior to the interview, the purpose of the interview, the aims of our study and the research question were shared with the expert. The guideline included two questions: (1) Which studies or insights do you consider valuable for studying processes of teacher agency development? (2) Which processes within your field of expertise do you consider relevant for studying how teacher agency takes shape in educational practices? The first author invited the experts via email. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, summarized and fed back to the experts for member checking. We used several databases to search for peer-reviewed literature such as EBSCO, ERIC, SCOPUS, Springer Link and ScienceDirect. In Section 2.2.2 we explain how we used these databases.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Determining our focus on domains of literature

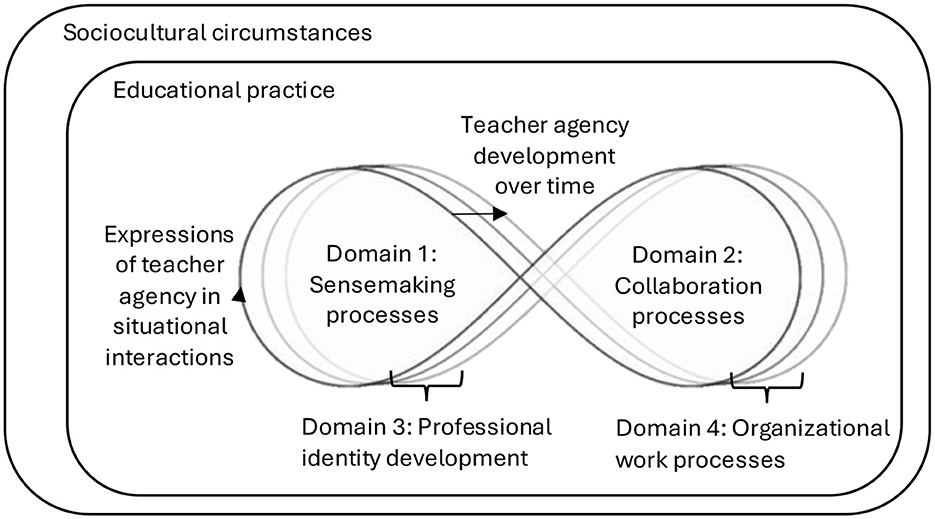

The experts we selected for the interviews were researchers who had published for several years within this field. The interviews helped us to become aware of relevant perspectives, find specific sources to consult, and to clarify choices we had to make. Based on the experts' responses to the first question, we compiled a list of studies and concepts that needed to be read and analyzed. The answers of the experts to the second interview question were summarized and their insights were clustered into themes. Based on this step, we identified four themes, or domains, to study the phenomenon of teacher agency in literature. The first theme that emerged was the dynamic, situational nature of agency and the huge role of subjective sensemaking processes in distinguishing actions as “agentic”. As a result, we focus on the domain of “sensemaking processes” (1). The second theme that emerged was the major role of social interactions within the school organization in shaping sensemaking processes and the huge role of the collective agency of the teaching community in relation to individual teacher agency (Evans, 2017). This led us to distinguish the domain of “collaborative processes” (2). Thirdly, the close relationship between teacher agency and professional identity processes emerged. It concerns the value of understanding how the situated actions of teachers are built from their own historical and developing self and therefore we focus on the domain: “professional identity processes” (3). The final theme is also related to the intertwined nature of agency: teacher actions are shaped within and through the collective practices of their workplace (Smith, 2017). This became the domain “organizational work processes” (4). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these domains, their reciprocal relationship, and their relationship to agency development and situational expressions of agency over time.

Figure 1. The four general domains of literature distinguished in this study, through which teacher agency takes shape in educational practices.

2.2.2 Developing a deeper understanding of major theoretical contributions

After selecting relevant domains of literature, we developed a more in-depth understanding of the available theories within these domains. Based on the insights gained from the expert interviews, the first author selected specific theoretical contributions and scholars from each domain. The considerations and choices were then discussed in the research team. One selection criterion was publication after 2015. Furthermore, we chose theoretical contributions that adopt a sociocultural perspective and are consistent with our understanding of teacher agency as a situated, collective, normative, and relational phenomenon. A further selection criterion was that sources needed to address processes that are important in complex systems, such as education. In these kinds of contexts, diversity, self-organization, unpredictability, ambiguity, and personal motivations are important to make the entire organization stronger (Strom and Viesca, 2020). We searched for insights to understand how teachers guide their actions to navigate these dynamics, both while relating with each other and staying connected with their own selves. The first author marked theoretical insights that were referred to in several sources, which allowed her to infer that their significance for research is currently accepted. Next, she consulted the original sources to grasp the theoretical perspectives set out in these. The second author and a colleague researcher assessed the topicality of these theoretical contributions and checked them for consistency with the perspective adopted in this study. Following this, the first author summarized and compared the insights from these sources. All four authors were actively involved in a critical discussion of these collected theoretical insights, and in reaching a consensus.

2.2.3 Describing how agency can be acknowledged within these processes

Our last step, based on our theorization of teacher agency, consisted of integrating the insights we gained about relevant processes in educational practices, and of describing how the attainment of agency can be recognized within those processes. Approached from our sociocultural perspective, agency is a phenomenon that is situated, collective, normative, and relational. To understand how teacher agency can enable teacher wellbeing, we paid particular attention to processes that enable teachers to create situations and positions that empower them to reconcile discrepancies between, on the one hand, their appreciation of developments in their educational practices, their moral values, ambitions, and capacities on the other, and what they consider necessary to participate and thrive within their social practices.

2.3 Quality assurance

To minimize personal bias in our interpretations of the literature, to interconnect the literature in a meaningful way, and to develop a deepened understanding, the methodological approach has been discussed with the entire research team. Additionally, the first author remained in continuous dialogue with the other authors during the study (Tracy, 2010). Due to the extensive research area we studied, there is a risk that our insights are based on an incomplete search. We attempted to minimize this drawback by leveraging expert insights into the search process for relevant literature and by going back to the original source. An inadequacy of our study may be related to publication bias. Because we focused our search on studies from 2015 onwards, it is possible that we paid relatively more attention to studies that challenge existing insights from studies published before 2015. As a consequence, we might have undervalued agreed upon insights on the subject. In the following sections we elaborate on our insights.

3 Results

3.1 Domain 1: teacher agency in sensemaking processes

To understand how agency takes shape within sensemaking processes, we used insights on “sensemaking processes in (self-)narratives” (Bijlsma et al., 2016; Stollman et al., 2022; Weick et al., 2005), “figured worlds and self-authoring” (Brewer et al., 2020), and “the managing of ambivalence and incongruencies in sensemaking” (Rom and Eyal, 2019).

Sensemaking is seen as an ongoing process of analyzing situations and developing presumptions about what is going on and what to do (Weick et al., 2005). Through sensemaking processes, proceedings “materialize” as they are “talked into existence” (Weick et al., 2005, p. 409) and become suitable for reflection and discussion. In this way, sensemaking has a social function for understanding situations and to make yourself understood, as well as an internal function for providing your own interpretation to create meaningfulness (Bijlsma et al., 2016). In sensemaking, multiple interpretations are negotiated, and elements of situations are amplified, removed, or reinterpreted to create coherence (Rom and Eyal, 2019; Stollman et al., 2022).

To make sense of your practice and your role in it, and to make yourself understood, it is less important that your representations of what is happening are correct. More important is that your interpretations seem plausible, legitimate, and memorable for those involved to understand the past and develop new insights and ambitions. For example, a teacher with a demanding class may experience that there is little room for innovation, while a school leader in the same context sees this very differently; a difference in “sensemaking” (Self-) narratives serve this purpose (Weick et al., 2005; Kelchtermans, 2023).

If we want to better understand how agency takes shape in teachers' sensemaking processes, we need to analyze their narrations to understand how they make what is going on plausible, and how they perceive their own role (Holland et al., 1998; Brewer et al., 2020). At the same time, we need to analyze these narrations to understand how teachers become aware of incongruencies, tensions and ambivalence in their sensemaking processes, how they allow for these (Pratt, 2000; Rom and Eyal, 2019), and what their insights are about what they can do to manage them.

3.1.1 What characterizes teacher agency in sensemaking processes?

Agency can be understood as the typical way teachers narrate knowledge gaps in their understanding of situations, to derive meaning in the complexities of their practice and to use these interpretations as a tool for action (Hopwood, 2017). Or more precisely formulated: agentic narratives help teachers to make sense of their practices, their ambitions, and their own roles as teachers, in ways that enable them to imagine and realize future situations in which what they consider important, attainable, and acceptable is connected (Stetsenko, 2019). For example, a teacher may experience the role of the school leader as demanding and reflect on this in such a way that in her actions she can circumvent a reaction from the school leader that is perceived as obstructive. The literature on sensemaking processes illustrates that it is important that in agentic narratives:

“Teachers have literate figured worlds” (Brewer et al., 2020). This indicates that teachers' practices and their role in these makes sense to them, based on an understanding of how things work for those who participate within them, and rooted in an understanding of how things have evolved because of their sociocultural history. In other words, teachers know how the work and learning processes in their practices take shape and know what is regarded as important within the community from a moral perspective. They also have a feeling for the reciprocal professional relationships between their colleagues and the discourses that take shape. And it is clear to them what is needed, attainable and possible in their practices based on an understanding of the virtues, rules and agreements that are established, and how the latter have developed through the organization's culture (Brewer et al., 2020).

“Teachers critically, and openly question the value and meaning of courses of action” (Edwards et al., 2017; Ylén, 2017). This means that teachers are aware of what they consider important in a particular situation, based on an awareness of their own moral judgements and normative positioning in relation to others and their practice. Moreover, their narratives help them to recognize, address, and express the salient features of tensions between a course of action and what they themselves consider important.

“Teachers scaffold their actions to regain coherence.” This refers to how agentic narratives enable teachers to author themselves in their practices, and to envision what they need to do to set up future practices that translate their ambitions into reality. These narrations can help them to navigate situations, or negotiate established thoughts, sense of selves and/or handlings of themselves and/or others in their practices, in ways that enable them to realize what is important to them (Brewer et al., 2020; Stetsenko, 2019).

3.2 Domain 2: teacher agency in collaboration processes

To develop our understanding of agency development within collaboration processes, we made use of the notion of “distributed leadership” (Spillane et al., 2004), insights on “teacher collaboration processes” (Grimm, 2023; Vangrieken et al., 2015) as well as insights on “heedful interrelating” (Miyahara et al., 2020) and “relational agency” (Edwards et al., 2017; Evans, 2017).

We consider “distributed leadership” a useful notion to understand how agency, in the same way as leadership, is situated in the thoughts, feelings and actions of teachers as embodied throughout their school organization. As such, agency can spread within and through numerous sociocultural charged interactions, with each interaction playing a specific role in enabling or preventing teacher agency development and laying the groundwork for further interactions (Spillane et al., 2004; Harris et al., 2022). These interactions differ in the extent to which teachers take part in said interactions, identify themselves as a team, interact to reach shared goals, and feel a shared responsibility to achieve such goals (Vangrieken et al., 2015).

The observation of others and the sharing of insights and materials can support teacher agency. However, such non-committal interactions alone are not enough to develop agency (Rajala and Kumpulainen, 2017). Agency development also requires teachers to jointly reflect on their practice, challenge current understandings, and to establish a habit of inquiry and discussion (Vangrieken et al., 2015). However, such deep-level collaborations require a willingness to take part in collaboration. This has proven difficult to achieve, especially in school cultures characterized by individualism, where teachers may feel that collaboration threatens their autonomy (Grimm, 2023).

In this sense, the notion of “relational agency” is important: the ability of teacher communities to jointly expand interpretations about what is important and required in a situation, and to act in ways that a single practitioner would be unable to achieve (Edwards, 2020). These deep-level collaborations require “relational expertise”: a capacity to find out and understand what matters to colleague teachers, and an ability to sense and convey what matters to yourself, and to draw on these understandings when needed (Edwards, 2020).

3.2.1 What characterizes teacher agency in collaboration processes?

In agentic collaboration processes, teachers align their thoughts and actions to jointly address complex matters such as critically questioning their norms, values, and handling of situations. Teachers build joint agentic actions when they recognize each other's abilities, understand how they interpret problems, and know what matters to themselves and to other teachers involved in professional practice. Joint agency also requires being involved with colleagues both from a professional and an individual perspective, and being able to express one's own values, motives, and perspectives. Finally, joint agency requires the ability to align motives by interpreting and responding to problems and, by doing so, acting in a well-considered way. The literature on teacher collaboration processes illustrates that it is important that in agentic interactions:

“Teachers feel connected through their ambitions” (Vangrieken et al., 2015). This requires that teachers who take part in the interactions are willing and committed to interacting with their colleagues, because it is in line with their ambitions. Moreover, it means that they acquire and use the proper knowledge, expertise, and authority to achieve their goals as a team. Finally, this points to a collaboration process in which teachers' individual and joint roles and responsibilities in the interactions enable them to be properly involved, because these roles are clear, suited for the purpose, and considered fair (Vangrieken et al., 2015).

“Teachers have developed relational expertise” (Edwards, 2020). This means that they recognize and understand each other's roles in the organization, each other's perspectives, customs, methods, and intentions, and what is important to everyone. They are also able to convey their own ambitions, positions, abilities, roles, norms, and values to each other. They acknowledge and respect different opinions, abilities, and motives. Such collaborations are characterized by attentive and sincere listening, openness, and inquiring about each other's reasons, interpretations, suggestions, and underlying values (Edwards et al., 2017).

“Teachers heedfully interrelate through their actions” (Edwards et al., 2017). This means that they carefully, critically, and purposively do their work, paying attention to the effect of their behavior on group functioning to complete a task (Miyahara et al., 2020). This does not imply that they respond or think alike, but it entails that their understanding of each other's responses, approaches, strategies, and actions allows them to rely on each other to respond to each other autonomously and fluidly, and to act in alignment (Stephens and Lyddy, 2016). By doing so, they join their abilities and expand their potential to achieve their individual and collective ambitions.

3.3 Domain 3: teacher agency in professional identity development

To develop our understanding of agency development within professional identity development, we made use of insights on “value oriented professional development” (Bakker, 2016), “self-understanding” (Kelchtermans, 2023) and “Dialogical Self Theory” (Akkerman and Meijer, 2010).

Bakker (2016) emphasizes the significance of developing and critically examining one's norms, values, and attitudes in the workplace, to address the complex matters that underly educational practice. These personal values of teachers arise in a firm relationship with the socio-cultural contexts in which they are developed. They are rooted in different domains such as the teacher's biography, their practices, and the teaching profession itself (Kelchtermans, 2023). Within these competing and often conflicting value systems, professionals try to make sense of what is important in practice, and strive to “achieve a good action” based on a sensitivity to their own self and the appeal which “the other for whom [they are] responsible” makes to them (Bakker, 2016, p. 18, 19).

Teachers' sense of self offers a way to see and represent themselves throughout multiple and continuous interactions in their professional practice (Kelchtermans, 2023). The roles that teachers assume guide their sensemaking processes and provide clues of who they are in relation to others. By interrelating these roles, teachers keep coherence and consistency in their sense of self (Kelchtermans, 2023). Dialogical Self Theory outlines how teachers create coherence in their interactions and helps us to understand teacher agency as both relational and intra-individual (Monereo and Hermans, 2023; Akkerman and Meijer, 2010). A teacher is seen as an active participant in a situated practice, but also as a historically continuous self, which is self-recognizable through time. Dialogical Self Theory argues that multiple I-positions (each of them personalities representing a specific viewpoint and story) are held together in the unity of self through self-dialogue (Akkerman and Meijer, 2010). Self-dialogue is an ongoing process of negotiating and interrelating multiple I-positions, leading to a continuous process of positioning and repositioning, so that a coherent and consistent sense of self is supported during different participations in the workplace. In this way, a teacher who sees himself as an expert in a particular field, but also as someone who does not dare to speak in front of a large group, can integrate the repeated I-position of bringing up issues in meetings from the role as chair of a working group into his self-image and start to see himself more as an expert teacher who is listened to. However, rapid changes, frictions or shared sensemaking processes may threaten teachers by undermining their worldview, self-efficacy, or sense of self (Weick et al., 2005). In these situations, teachers may adopt coping strategies to reconcile their conflicting ideas of self (Kelchtermans, 2023). Such coping strategies (Imants and Van der Wal, 2019) include adopting interpretations of others, trying to influence others, or disconnecting interpretations from earlier interpretations (Rom and Eyal, 2019).

3.3.1 What characterizes agentic identity development processes?

In different situations and through time, teachers weigh their actions within the tension field between developing their capacities, acquiring sensitivity to what is required of them as teachers, and integrating within their communities (Illeris, 2018). In doing this, they develop patterns that shape the unique ways in which they express agency, develop their roles, and construct their sense of self (Kelchtermans, 2023). We want to know how teachers shape these patterns that empower them to reconcile discrepancies between, on the one hand, their appreciation of developments in their practices, their moral values, ambitions, and abilities on the other, and what they consider necessary to participate and thrive within their social practices. Teachers who successfully overcome sensemaking discrepancies develop a deeper understanding of their professional identities (Rom and Eyal, 2019). When teachers cannot reconcile these discrepancies, their identities become incongruous and conflicting feelings, alienation, or identity confusion can arise (Rom and Eyal, 2019). In short, literature on teacher identity development illustrates that it is important that in agentic reflections:

“Teachers are perceptive in making moral considerations.” This refers to how identity negotiations enable teachers to address the competing and often conflicting value systems that underly educational practice. Moreover, identity negotiations permit teachers to make sense of what is important to them based on a sensitivity to their own role, capacities, norms and values, and a sensitivity to the appeal those for whom they are responsible (pupils) make on them (Bakker and Wassink, 2015).

“Teachers align their ambitions with their positions, sense of self, opportunities, and resources.” Identity negotiations enable teachers to critically examine and negotiate their norms, values, and attitudes. Moreover, identity negotiations allow teachers to maintain their unity of self through self-dialogue, an ongoing process by which they interrelate their multiple positions and roles in a variety of situations (Akkerman and Meijer, 2010).

“Teachers take control to pursue their preferences.” This means that identity negotiations enable teachers to cope with conflicting ideas and reconcile their sense of self, by developing a deeper understanding of their professional identity (Rom and Eyal, 2019).

3.4 Domain 4: teacher agency in organizational work processes

To develop our understanding of how agency develops through the organizational activity system, we used the notions “activity system” (Engeström and Sannino, 2021), “organizational learning” (Rikkerink et al., 2015; Azorín and Fullan, 2022), “common knowledge” (Edwards, 2020) and “dynamic forces in peer learning” (Bridwell-Mitchell, 2015).

While shaping their actions, teachers continually strike a balance between the assimilation of knowledge and skills newly developed in the organization, and the application and exploitation of what they learned before (Rikkerink et al., 2015). The unfolding of teachers' insights and actions can be seen as a continuous flow of feedforward and feedback, which needs to be in balance to continue the workflow in interdependence with the organization (Rikkerink et al., 2015). The continual tension between these feedforward and feedback flows, forms a circular process of (joint) discursive meaning-giving and intuitive sense-giving at a personal level. Interaction, communication, and collective reflection are essential for the smooth running of this process. As a circular process, it can only be sustained when the ambitions and actions of teachers, and their embedding in the organization, are aligned (Rikkerink et al., 2015).

Teacher collaboration processes are shaped by a variety of forces that influence the social dynamics of teacher communities, forces through which teachers develop agency (Vangrieken et al., 2015). Bridwell-Mitchell (2015) illustrates three key forces and their counterbalancing forces which impact teacher agency development in educational settings. These are: forces that drive mutual learning processes toward innovation vs. consolidation; forces that drive teacher interactions toward cohesion vs. diversity; and forces that drive sensemaking processes and ways of working toward diversity vs. conformity. Putting more pressure on socialization can foster heedful behavior but may limit experimental learning. Increasing cohesion among teachers can strengthen mutual understanding but may impede sensitivity to different interpretations or solutions. And introducing more convergence can facilitate the development of shared visions, but may limit critical reflection (Bridwell-Mitchell, 2015). For example, these developments can come about if the school vision is no longer seen as a source of inspiration from which new insights can emerge, but as a straitjacket within which all initiatives must fit. Teachers shape their actions in building and balancing these forces, individually and jointly. While seeking this balance, they make sense of what is going on, engage in projects that are important to them, learn of what is important to others, develop new insights, and renegotiate their sense of self. These processes can turn into fragmented, chaotic practices, but also in stabilized, growing workable practices (Rikkerink et al., 2015).

3.4.1 What characterizes teacher agency in organizational work processes?

To develop agency, teachers need to develop structures, routines, and practices through which they can influence the interplay of forces taking place in the activity system. This construction process needs to be undertaken individually and jointly, in a well-considered way. Moreover, while building and taking part in these practices, it is important that teachers construct and reconstruct “common knowledge”. This fostering of common knowledge includes recognizing similar long-term value-laden goals (such as children's wellbeing) as a shared moral purpose that holds all motives together. Common knowledge mediates collaboration on complex problems (Edwards et al., 2017). It is built over time in interactions across educational practices, by sharing professional values and motives in discussions, and by justifying interpretations and suggestions, inquiring after them, and providing reasons for them (Edwards et al., 2017). In short, the literature on organizational work processes illustrates that for the fostering of teacher agency it is important that:

“Teachers exchange their insights and ambitions with other professionals in various situations and social compositions as part of their work.” This requires teachers to make use of a plurality of situations and occasions to engage with their own goals, moral purposes and long-time ambitions, as well as those of others. They need to do this in varying social compositions, within their own community and in other communities (such as cross-school teacher communities, or district-based interdisciplinary communities). Such interactions enable teachers to recognize what matters in each professional organizational role, and to identify the goals and moral purposes that shape and take forward professional practice (Edwards, 2020; Azorín and Fullan, 2022).

“While doing their work, teachers adjust developments in their practices to align them with common values and organizational ambitions” (Rikkerink et al., 2015). This means that, while doing their work, teachers use opportunities to solve problems that stem from frictions between feedback and feedforward flows. This enables them to align developments in their educational practices with their joint values and ambitions (Rikkerink et al., 2015). In other words, critical inquiry is being incorporated in the daily proceedings to value and adapt the impact of (new) practices.

“Teachers experience that they are capable, authorized and willing to jointly direct developments in their practices.” This means that teachers take control to realize their individual and shared ambitions individually and jointly, in the tasks and responsibilities distributed among teachers in the workplace. To achieve this, work processes must be set up to communicate, discuss, evaluate, and adjust joint actions. Such work processes need to be rooted in common knowledge, where teachers' actions are motivated by insight into what really matters to them (Harris et al., 2022).

4 Discussion

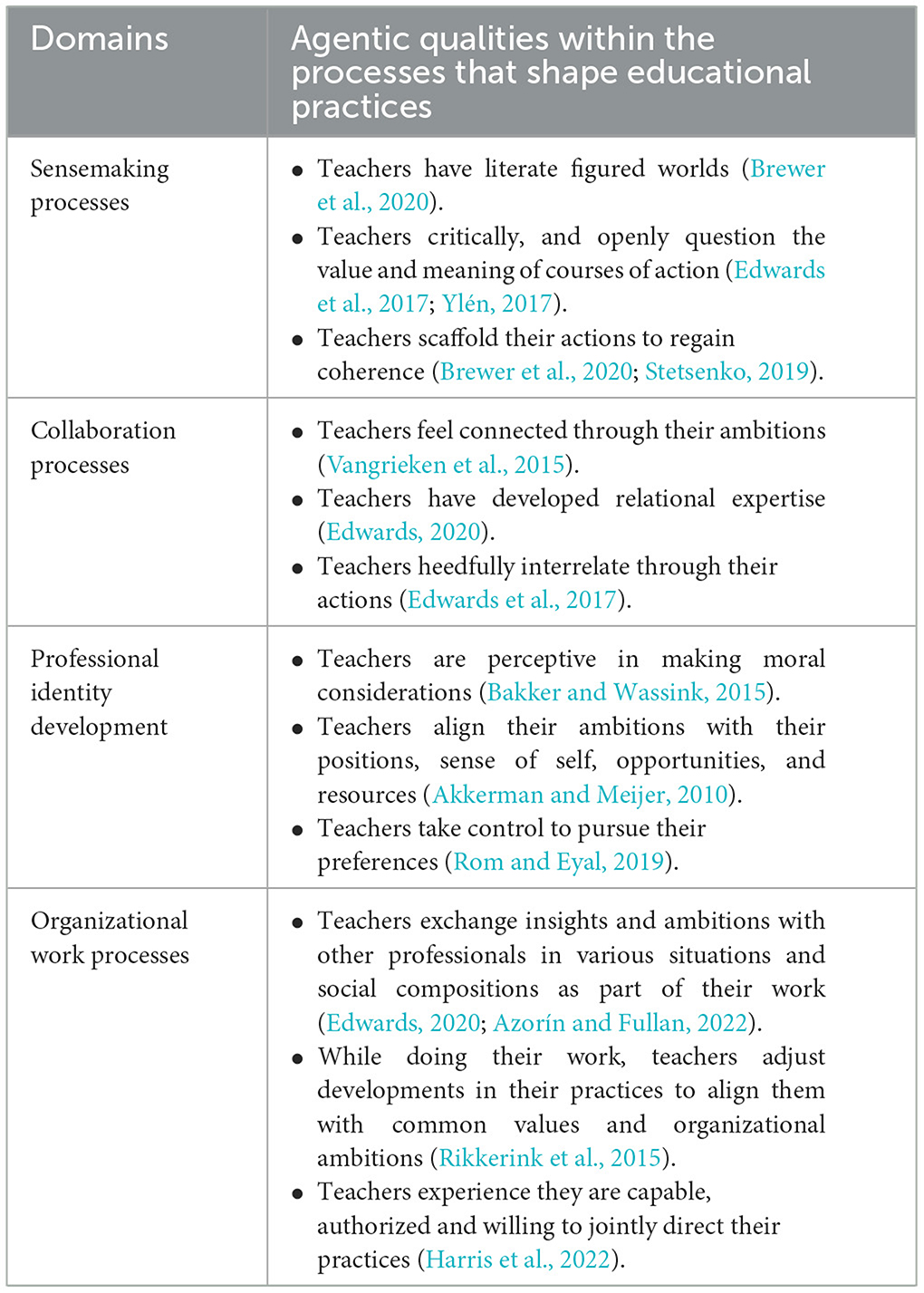

Teacher agency is a topic that has gained a lot of interest, based on expectations that it brings opportunities for teacher well-being and educational quality. Despite the available insights into how agency can be promoted in educational practices, it proves difficult to realize the changes that are needed. Our research attempts to contribute to the body of knowledge, by detailing how this situated and value-laden phenomenon can be recognized and validated in the dynamics of education. We did this by analyzing and connecting different strands of literature about processes that shape educational practices, and by specifying how expressions of teacher agency can be recognized within those processes. We described how agency can take shape in sensemaking processes, collaboration processes, professional identity development, and the organization of work processes. Table 1 summarizes the twelve qualities that characterize agency in these processes, which we have derived from our theory synthesis. Based on our theory synthesis, we have arrived at twelve agentic qualities that characterize agency in these processes. Agentic sensemaking processes can be characterized by literate figured worlds, critical, and open questioning of the value and meaning of courses of action and scaffold the actions of the teacher to regain coherence. In agentic collaboration processes, teachers feel connected with each other through their ambitions, have developed relational expertise and heedfully interrelate through their actions. In agentic professional identity processes teachers are perceptive in making moral considerations, align their ambitions with their positions, sense of self, opportunities, and resources and take control to pursue their preferences. And finally, in agentic organizational work processes, teachers exchange insights and ambitions with other professionals in various situations and social compositions as part of their work, adjust developments in their practices while doing their work, to align them with common values and organizational ambitions and teachers experience they are capable, authorized and willing to jointly direct their practices.

Table 1. Summary of agentic qualities within the processes that shape educational practices structured in four domains.

Our study contributes to the conceptualization of teacher agency as a situated phenomenon by making tangible how this situatedness can take shape, woven into the complexity of educational practices within and through structural, interactional, and intra-individual processes. The findings underscore that it is not enough to change the collaboration structures within practice, or to motivate teachers to participate in professional development programs. Instead, they underline that facilitating teacher agency requires a multi-pronged approach, in which adjustments must always be sought at various layers of the organization. Additionally, the impact of interventions can never be guaranteed in advance and must be determined and adjusted from a situated perspective. Moreover, the perspective of those involved should both serve as a starting point for processes of change and as an anchor point throughout the process. Finally, attention should be paid to expressions of agency in both immediate processes and long-term developments. We advise professionals to create situations in which attention is paid to the personal and shared professional ambitions of teachers and the tensions that teachers experience while doing their work to shape these ambitions. We propose to use agentic qualities in all four domains to support conversations and to create situations in which teachers feel acknowledged and connected. Activating joint teacher agency in the complexity of educational practice strengthens the quality of educational practice from within.

An important limitation of our study is that the domains of literature that we adopted do not provide an exhaustive account of all the processes through which teachers develop agency in their practices. For instance, from a systems perspective, a broader focus than that of the school level is needed to include insights about agency development through collaboration processes between organizations (Rönnerman and Olin, 2024). To strengthen and broaden the theoretical framework, we recommend further literature research that covers additional research domains, such as network learning.

We believe it is important to emphasize that the processes we presented in this study overlap and mutually influence each other. It is necessary to conduct empirical research into how these processes can be found in practical situations and what impact their mutual influence has on the development of agency. For future research, this implies that studies should trace situational expressions of agency across different contexts, pay attention to context characteristics, and offer theoretical insights into how agency may develop over time. Moreover, the situational nature of agency implies that it is difficult to predict how teacher agency develops over time. Gaining insight into agency development processes requires a long-term perspective to recognize patterns in the development of insights, concerns, actions, and tools, and to gain insight in their impact on teachers' inhabited cultural practice and their sense of self. We consider longitudinal case study research suitable in which developments in teacher ambitions and perceived tensions are linked to the teachers' professional development and to changes in the essential processes within and through which teacher agency takes shape in practice. The use of methods such as experience sampling, observations, and interviews with follow-ups may be helpful.

Author contributions

AE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft. HO-M: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ED: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht under Grant HRD-BB-kab-2018-437.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Inge Andersen for her inspiration and insights, which have made a valuable contribution to the realization of this work. We also want to thank experts SA, JI, AR, WS, JS, and MV for their contributions to our insights. The interviews we conducted with them enriched our insights into the various research domains within our study; organizational development, situated processes, interactive learning, and agency development. Exchanging ideas from various angles made us cross boundaries to find shared meaning. It generated an awareness of the strengths and gaps in our focus and made us more aware of the sociocultural paradigm from which we think and work. And finally, a sincere thank you to Stijn van Tongerloo for his diligent proofreading of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akkerman, S. F., and Meijer, P. C. (2010). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.013

Azorín, C., and Fullan, M. (2022). Leading new, deeper forms of collaborative cultures: questions and pathways. J. Educ. Change 23, 131–143. doi: 10.1007/s10833-021-09448-w

Bakker, C. (2016). “Professionalization and the quest how to deal with complexity,” in Complexity in Education. From Horror to Passion, eds. C. Bakker, and N. Montessori (Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei: SensePublishers), 9–29.

Bakker, C., and Wassink, H. (2015). Leraren en het goede leren. Manifest lectoraat Normatieve Professionalisering. Utrecht: Hogeschool Utrecht.

Biesta, G. (2018). “Interrupting the politics of learning,” in Contemporary Theories on Learning, Learning Theorists…In Their Own Words, 2nd Edn, ed. K. Illeris (London/New York, NY: Routledge), 243–259.

Bijlsma, N., Schaap, H., and de Bruijn, E. (2016). Students' meaning-making and sense-making of vocational knowledge in Dutch senior secondary vocational education. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 68, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2016.1213763

Brewer, C., Okilwa, N., and Duarte, B. (2020). Context and agency in educational leadership: framework for study. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 23, 330–354. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2018.1529824

Bridwell-Mitchell, E. N. (2015). Collaborative institutional agency: how peer learning in communities of practice enables and inhibits micro-institutional change. Org. Stud. 37, 161–192. doi: 10.1177/0170840615593589

Cong-Lem, N. (2021). Teacher agency: a systematic review of international literature. Iss. Educ. Res. 31, 718–738. Available at: http://www.iier.org.au/iier31/cong-lem.pdf

Dhanabhakyam, M., and Sarath, M. (2023). Psychological well-being: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 3, 603–607. doi: 10.48175/IJARSCT-8345

Edwards, A. (2020). Agency, common knowledge, and motive orientation: working with insights from hedegaard in research on provision for vulnerable children and young people. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 26:4. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.04.004

Edwards, A., Montecinos, C., Cádiz, J., Jorratt, P., Manriquez, L., and Rojas, C. (2017). “Working relationally on complex problems: building capacity for joint agency in new forms of work,” in Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds. M. Goller, and S. Paloniemi (Cham: Springer), 229–248.

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2021). From mediated actions to heterogenous coalitions: four generations of activity-theoretical studies of work and learning. Mind Cult. Act. 28, 4–23. doi: 10.1080/10749039.2020.1806328

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., and Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Evans, K. (2017). “Bounded agency in professional lives,” in Agency At Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds. M. Goller, and S. Paloniemi (Cham: Springer), 17–36.

Grimm, F. (2023). Teacher leadership for teaching improvement in professional learning communities. Prof. Dev. Educ. 50, 1135–1147. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2023.2264286

Harris, A., Jones, M., and Ismail, M. (2022). Distributed leadership: taking a retrospective and contemporary view of the evidence base. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 42, 438–456. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2022.2109620

Holland, D., Lacichotte, W., Skinner, D., and Cain, C. (1998). Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hopwood, N. (2017). “Agency, learning and knowledge work: epistemic dilemmas in professional practices,” in Agency At Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds. M. Goller, and S. Paloniemi (Cham: Springer), 121–140.

Hopwood, N. (2022). Agency in cultural-historical activity theory: strengthening commitment to social transformation. Mind Cult. Act. 29, 108–122. doi: 10.1080/10749039.2022.2092151

Illeris, K. (2018). “A comprehensive understanding of human learning,” in Contemporary Theories on Learning, Learning Theorists…In Their Own Words, 2nd Edn, ed. K. Illeris (London/New York, NY: Routledge), 7–20.

Imants, J., and Van der Wal, M. (2019). A model of teacher agency in professional development and school reform. J. Curric. Stud. 52, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2019.1604809

Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: four approaches. AMS Rev. 10, 18–26. doi: 10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0

Juvonen, S., and Toom, A. (2023). “Teachers' expectations and expectations of teachers: understanding teachers' societal role,” in Finland's Famous Education System, eds. M. Thrupp, P. Seppänen, J. Kauko, and S. Kosunen (Singapore: Springer), 212–135.

Kelchtermans, G. (2023). “Narrative and biography in teacher work lives and development,” in International Encyclopedia of Education, eds. R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, and K. Erkican (Elsevier), 106–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.04019-7

Lau, J., Vähäsantanen, K., and Collin, K. (2022). Teachers' identity tensions and related coping strategies: interaction with the career stages and socio-political context. Prof. Prof. 12:4562. doi: 10.7577/pp.4562

Li, L., and Ruppar, A. (2020). Conceptualizing teacher agency for inclusive education: a systematic and international review. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 44, 1–18 doi: 10.1177/0888406420926976

Miyahara, K., Ransom, T. G., and Gallagher, S. (2020). “What the situation affords: habit and heedful interrelations in skilled performance,” in Habits: Pragmatist Approaches from Cognitive Science, Neuroscience, and Social Theory, eds. F. Caruana, and I. Testa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 120–136.

Monereo, C., and Hermans, H. J. M. (2023). Education and dialogical self: state of art. J. Study Educ. Dev. 46:2201562. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2023.2201562

Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., Hadar, L., Smith, K., Helleve, I., and Ulvik, M. (2017). Teachers' perceived professional space and their agency. Teach. Teach. Educ. 62, 37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.11.005

Pound, P., and Campbell, R. (2015). Exploring the feasibility of theory synthesis: a worked example in the field of health related risk-taking. Soc. Sci. Med. 124, 57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.029

Pratt, M. G. (2000). The good, the bad, and the ambivalent: managing identification among amway distributors. Adm. Sci. Q. 45, 456–493. doi: 10.2307/2667106

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Rajala, A., and Kumpulainen, K. (2017). “Researching teachers' agentic orientations to educational change in finnish schools,” in Agency At Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds. M. Goller, and S. Paloniemi (Cham: Springer), 311–329.

Rikkerink, M., Verbeeten, H., Simons, R. J., and Ritzen, H. (2015). A new model of educational innovation: exploring the nexus of organizational learning, distributed leadership, and digital technologies. J. Educ. Change 17, 223–249. doi: 10.1007/s10833-015-9253-5

Rom, N., and Eyal, O. (2019). Sensemaking, sense-breaking, sense-giving, and sense-taking: how educators construct meaning in complex policy environments. Teach. Teach. Educ. 78, 62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.008

Rönnerman, K., and Olin, A. (2024). Practice changing practices: influences of master's programme practice on school practices. Prof. Dev. Educ. 50, 157–173. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2021.1910978

Smith, R. (2017). “Three aspects of epistemological agency: the socio-personal construction of work-learning,” in Agency At Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds. M. Goller, and S. Paloniemi (Cham: Springer), 67–84.

Spillane, J., Halverson, R., and Diamond, J. B. (2004). Towards a theory of leadership practice: a distributed perspective. J. Curric. Stud. 26, 3–34. doi: 10.1080/0022027032000106726

Stephens, J. P., and Lyddy, C. J. (2016). Operationalizing heedful interrelating: how attending, responding, and feeling comprise coordinating and predict performance in self-managing teams. Front. Psychol. 7:362. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00362

Stetsenko, A. (2019). Radical-transformative agency: continuities and contrasts with relational agency and implications for education. Front. Educ. 4:148. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00148

Stollman, S., Meirink, J., Westenberg, M., and Van Driel, J. (2022). Teachers' learning and sense-making processes in the context of an innovation: a two-year follow-up study. Prof. Dev. Educ. 48, 718–733. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1744683

Strom, K. J., and Viesca, K. M. (2020). Towards a complex framework of teacher learning-practice. Prof. Dev. Educ. 47, 209–224. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1827449

Tracy, S. (2010). Qualitative quality: eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 16, 837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

UNESCO (2023). The Teachers We Need For The Education We Want: The Global Imperative to Reverse the Teacher Shortage; Factsheet, International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030. Paris. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386808 (accessed April 13, 2024).

Van Leeuwen, J. L., Schaap, H., Geijsel, F. P., and Meijer, P. C. (2024). Early career teachers' experiences with innovative professional potential in secondary schools in the Netherlands. Prof. Dev. Educ. 50, 403–419. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2022.2129738

Van Vijfeijken, M., van Schilt-Mol, T., van den Bergh, L., Scholte, R. H. J., and Denessen, E. (2024). An evaluation of a professional development program aimed at empowering teachers' agency for social justice. Front. Educ. 9:1244113. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1244113

Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., and Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: a systematic review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.001

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., and Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Org. Sci. 16, 409–421. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0133

World Health Organization (2022). Mental Health. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed May 24, 2024).

Keywords: theory synthesis, sociocultural perspective, teacher agency development, teacher wellbeing, educational practices, situated processes

Citation: Emans A, Oolbekkink-Marchand H, Bakker C and De Bruijn E (2025) Teacher agency in the dynamics of educational practices: a theory synthesis. Front. Educ. 9:1515123. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1515123

Received: 22 October 2024; Accepted: 16 December 2024;

Published: 07 January 2025.

Edited by:

Amjad Islam Amjad, School Education Department, Punjab, PakistanReviewed by:

Sana Javaid, Superior University, PakistanSamiya Ashfaq, Allama Iqbal Open University, Pakistan

Copyright © 2025 Emans, Oolbekkink-Marchand, Bakker and De Bruijn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anita Emans, YW5pdGEuZW1hbnNAaHUubmw=

†ORCID: Elly De Bruijn orcid.org/0000-0003-4391-4681

Anita Emans

Anita Emans Helma Oolbekkink-Marchand

Helma Oolbekkink-Marchand Cok Bakker

Cok Bakker Elly De Bruijn

Elly De Bruijn