- Department of Jewish Studies, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

Introduction: This study examines the impact of pedagogical redesign on two courses about Israel and Palestine, focusing on fostering an inclusive learning environment. The project aimed to address challenges such as student retention, attendance, participation, and academic performance by implementing innovative teaching strategies tailored to diverse student backgrounds.

Methods: The redesign incorporated several key interventions: an experiential learning-based final assignment, scaffolded into multiple steps with opportunities for feedback; group discussions to promote active learning and cooperation; and the integration of optional multimedia resources, such as YouTube videos and podcasts, to enhance engagement and time on task. Additionally, students were involved in the evaluation process by providing feedback and were offered the opportunity to publish their final projects on a public website, further incentivizing their work. To examine the effectiveness of these changes, the study employed a mixed-methods approach. This approach involved the collection and analysis of both quantitative data (such as surveys and performance metrics) and qualitative data (such as student feedback and one-way ANOVA analysis) across six undergraduate course offerings between 2019 and 2024.

Results: The interventions were tested with students from varied backgrounds engaging in complex discussions. The initial findings revealed significant improvements in critical metrics, including reduced drop/fail/withdraw rates, increased time on task, and higher grades. Students demonstrated enhanced engagement and a more positive overall learning experience, indicating the potential for further positive outcomes.

Discussion: The preliminary results suggest that the implemented pedagogical changes effectively created a more inclusive and engaging learning environment. By integrating experiential learning, providing timely feedback, and utilizing diverse resources, the project demonstrated the potential for scalable improvements in student outcomes.

Introduction

This study, focusing on two undergraduate courses at the University of Kansas (KU), aimed to create a more inclusive learning environment for students in courses about Israel and Palestine. The purpose was to address the unique challenges and opportunities of teaching about Israel and Palestine, particularly the need for innovative and inclusive teaching strategies. These strategies convey the historical and political intricacies of the conflict and foster a classroom environment conducive to open dialogue, critical thinking, and mutual respect, which is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

Creating an inclusive learning environment is crucial for the success of such courses. An inclusive classroom ensures all students feel valued and supported and can contribute meaningfully to discussions. This can be achieved through equity-focused teaching practices, including active learning, collaborative group work, and digital tools to enhance engagement and retention. By fostering an inclusive climate, educators can help students from diverse backgrounds to feel comfortable expressing their opinions and engaging with complex and sensitive topics.

This article explores the implementation of inclusive and experiential learning strategies in courses about Israel and Palestine, focusing on their impact on student engagement and success. It examines the motivations behind students’ enrollment in these courses, the challenges of teaching such a contentious subject, and the effectiveness of various pedagogical approaches in creating a supportive and dynamic learning environment. Through a detailed analysis of course redesigns and student feedback, the article provides insights and recommendations for educators seeking to enhance their teaching practices and better support their students’ learning experiences. In doing so, the article details the impact of pedagogical changes on student retention, participation, and performance.

One of the courses of focus was “Israel/Palestine: The War of 1948.” This History course explores the background, key events, and aftermath of the 1948 war, focusing on topics such as the involved parties, international community efforts, the establishment of Israel, the partition of Palestine, the significance of the Nakba (catastrophe), and the unresolved status of Palestinian refugees. The course objectives aim to understand the 1948 War and its broader context comprehensively. Students explore theories of nationalism and colonialism, trace the modern historical background of Israel/Palestine, and examine the causes, events, and outcomes of the 1948 War. Students analyze the factors behind Israeli success and Palestinian failure, distinguish the interests of regional and international actors, and engage with various primary sources, including maps, to investigate the war’s consequences. Additionally, students develop digital mapping skills and critically assess competing narratives in the ongoing Israel-Palestinian conflict.

The second course was “Israel: From Idea to State.” This interdisciplinary course focuses on History and Political Science, exploring Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people and its challenge of balancing Jewish and democratic values. The first part of the course covers 19th-century Jewish history, the rise of Zionism, Palestinian history, and the path to statehood during the British Mandate while clashing with Palestinian ambitions for statehood. The second part explores the six major divides in contemporary Israeli politics and their historical roots, including the political, national, ethnic, religious, socioeconomic, and gender divides. Students analyze primary sources in historical, political, and social contexts and engage in public speaking on complex topics. Additionally, students produce a podcast episode addressing one of the key divides in modern Israel.

This article includes four sections. The first section is the literature review. The second section explains the methodology. The third section is for the findings. Fourth is the discussion section.

Literature review

Teaching Israel and Palestine

Teaching Israel and Palestine can take many forms, such as those suggesting seeing it as one field (Penslar, 2021). One leading approach is the dual narrative, which provides a forum for the two competing narratives. The opposing narrative triggers readers and students to support or criticize a narrative (Lazarus, 2008). For example, in a class based on this approach, students can compare two national cinemas in dialogue (Dittmar, 2013). Another approach is the critical-disciplinary approach derived from the practices of historians, such as the evaluation of multiple sources (Goldberg and Ron, 2014) or the critical analysis of conflicting sources (Goldberg, 2014). Another more traditional approach is focused on an authoritative single-narrative approach; however, it is educationally harmful since it could become “an attempt to reassert the “truth” of one’s own narrative against the “falsehood” of the other” (Bar-On, 2006). In this sense, an authoritative single narrative creates distrust, contrary to the need to bring students to work together.

Teaching the 1948 war to Israeli and Palestinian students at institutions in the Middle East while using the dual narrative approach encompasses the potential of education to serve as a means for de-escalating conflicts (Eid, 2010). While other challenges exist in teaching about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict outside of the region, particularly in the Global North, one major challenge persists. It is an extreme case in teaching where some of the students enrolled in such courses, particularly those with a connection to the region, enter the classroom with an already established idea about the conflict while siding with the Zionist or Palestinian narrative (Segal, 2019). It exemplifies how prior knowledge does not always provide an equally solid foundation for new learning (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 12). Despite the Middle East’s importance in USA foreign relations policy, many US citizens know very little about its history, culture, and politics (Muhtaseb et al., 2014, p. 16). Another challenge in teaching classes about the Middle East is competing with, or challenging media coverage of this region (Kirschner, 2012). This is especially relevant to online discourse, social media, and reaction to ongoing military action in the region.

Depending on the direction of the discussion, the value of education may be explained in various ways. At the core of the higher education mission is providing students with knowledge and skills. In this context, developing students’ critical thinking helps them express their opinions on this social issue and informs their activism and political decisions. Furthermore, studying Palestine can help spread the Palestinian narrative and increase activism (Pappé et al., 2024). Others went further to claim that such education of Palestinian narrative is intended to counter the dominance of pro-Israel curriculum in the West (Borhani, 2016) and suggests that a ‘paradigm shift’ is already in the making (Borhani, 2015). This highlights the problem with the dominance of Israel Studies and Jewish Studies scholars in offering courses on the conflict, let alone funding such courses, which all represent a power imbalance. On the other hand, teaching about Israel at Western institutions has expanded in the last two decades while deepening and expanding knowledge about Israel to generate sympathy and enhance understanding of Israel (Mousavi and Kadkhodaee, 2016) or, more significantly, appreciation of its complexity (Aronson et al., 2013). In addition to the importance of learning about Israel’s specifics, some have claimed that Israel is an interesting case study for scholars to gain insights into understanding diverse and complex societies and their challenges (Nikolenyi and Kabalo, 2019).

Some scholars have linked learning about the conflict to conflict resolution itself (Bar-Siman-Tov, 1994). Acknowledging and respecting each other’s narratives contributes to achieving peace by building bridges and collaboration (Dessel et al., 2017). Others highlight the linkages between learning and a higher level of sympathy with the other side, even if learning did not change the participants’ opinions (Schneider, 2020).

Inclusive learning environment and experiential learning

Equity-focused teaching is effective teaching since it creates an environment for success. Students have equal access to learning, feel valued and supported in their learning, experience parity in achieving positive course outcomes, and share responsibility for the equitable engagement and treatment of all in the learning community (University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, 2024).

The literature establishes the relationship between classroom climate and student learning. Classroom climate should not be seen as binary (inclusive vs. marginalizing). It may be more accurate to think of climate as a continuum, from explicitly marginalizing to implicitly marginalizing to implicitly centralizing and explicitly centralizing (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 171). A different approach showed that faculty conceptualize equity in three ways—“equality,” “inclusion,” or “justice,” which influence their approaches to teaching practices between instructor-centered versus student-centered (Russo-Tait, 2023). Professors reported using either lecturing (“equality conceptions”), active learning, and/or inclusive teaching practices (“inclusion conceptions”) or going beyond active learning and inclusive practices also to include an emerging critical pedagogy (“justice conception”). One example is a study focusing on equity in teaching math that used heterogeneous groups of students who were given responsibility and agency and worked collaboratively. The study reported that the vast majority responded with increased engagement, achievement, and enjoyment (Boaler and Sengupta-Irving, 2016).

Some inclusive teaching principles include having an inclusive mindset for all pedagogical decisions and providing structure (Sathy and Hogan, 2019). Courses with moderate or high-level structures have been positively correlated with students’ achievements across different student bodies (Eddy and Hogan, 2014).

Student engagement has been positively correlated with students’ success, retention, and graduation (Kinzie et al., 2008). Engaging educational practices include fostering student-faculty interaction and close relationships (Longwell-Grice and Longwell-Grice, 2008), encouraging student collaboration, promoting active learning, providing timely feedback, emphasizing time on task, setting high expectations, and respecting diverse learning styles (Chickering and Gamson, 1987).

Scholars have suggested early interventions in students’ careers to enhance retention, especially for students with underrepresented backgrounds (Kinzie et al., 2008, p. 30). More suggestions include a sense of belonging to the institution (Longwell-Grice et al., 2016), problem-solving activities, peer teaching, diverse teaching styles, collaborative learning, explicit and clear instructions, and support networks (Kuh et al., 2004).

In my courses, I follow the findings from the above literature survey. The final assignment uses digital tools to improve engagement and retention. This was based on the established record in scholarship that experiential learning can support the development of pedagogical discomfort (Greene and Boler, 2004). Hence, it supports engagement in learning conflict analysis and developing active and critical student-citizens (Head, 2020) and redesigning and scaffolding the final assignment into multiple steps to provide prompt feedback and validation and reduce the stakes of such a major assignment (Sathy and Hogan, 2019, p. 15).

Methodology

The research involved a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data with qualitative feedback to evaluate student motivations and the effectiveness of course redesigns. Data were collected from students enrolled in two specific undergraduate (BA) courses: “Israel/Palestine: The War of 1948“in Spring 2020, Fall 2022, and Spring 2024 with a total of 55 students; and “Israel: From Idea to State” in Fall 2019, Spring 2021, and Spring 2023 with a total of 67 students. Two mid-semester surveys were administered, one in Spring 2020 and another in Fall 2022, to assess student satisfaction and gather feedback on course structure and content. Surveys included closed-ended and open-ended questions to capture diverse student opinions and experiences.

Data analysis included both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Quantitative data from survey responses were analyzed to identify trends in student satisfaction, engagement, and perceived value of in-class activities. Qualitative feedback was reviewed to understand students’ personal experiences and the specific elements of the course redesign that contributed to their learning. For comparison across semesters, we focused on student performance and engagement metrics from the redesigned courses in 2021/2022 and 2023/2024, compared with data from the initial offering in 2019/2020. Metrics included the drop/fail/withdraw rate, time spent on assignments, attendance, final assignment grade, and final grades.

The IBM SPSS 28.0 software package was employed to conduct a one-way ANOVA for the quantitative analysis. This analysis assessed the effect of the “step of change” as an independent variable on key outcomes, including time spent on assignments, attendance, final assignment grades, and overall final grades. Significance levels were assessed at three thresholds (***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, and *p ≤ 0.05), allowing for precise identification of variables that meaningfully impacted academic performance.

The study involved “self-research,” whereby teachers investigate their work (Samaras and Freese, 2006). The methodological approach detailed above allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of student motivations and the effectiveness of pedagogical changes, providing a robust basis for conclusions and recommendations.

Findings

Why learn about Israel and Palestine?

Understanding the motivations behind students’ course selections can provide valuable insights into their educational priorities and interests. This study examines why students at one specific university enroll in courses focusing on Israel and Palestine. By analyzing student motivations, we aim to uncover the underlying factors that drive interest in this complex and often contentious subject matter. Such an understanding can inform curriculum development, enhance student engagement, and improve educational outcomes.

In exploring why students at my university enroll in these elective courses about Israel and Palestine, we identified four primary motivations. For detailed insights, refer to Supplementary Table A1. The first group of students expressed a general curiosity about the world. Many enrolled not with a specific intention to study Israel or Palestine but with a broader aim to understand global dynamics. They sought a “more nuanced understanding and view of what occurs in other countries” or to learn about the “political systems of different countries other than America.” This interest extended to international politics and gaining insights into regions such as the Middle East, indicating a desire to broaden their global perspective and cultural awareness.

The second group of students showed a specific interest in Israel or Palestine, driving them to seek courses that directly focus on these areas. Their motivations were often personal, stemming from family connections, recent visits, or because “[…] it often makes its way into the headlines of the day.” Students in this group were keen on understanding Israel’s historical, political, and international significance and the intricate and often contentious dynamics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They aimed to “have a better understanding of both sides of the Israeli/Palestine conflict,” reflecting a desire to grasp the complex narratives and tensions that characterize the region.

The third category of students was influenced by the professor. Some students have taken multiple classes with the professor due to their teaching style, expertise, or the engaging content they presented in their courses. This group highlights the impact of academic mentorship and the role of faculty in shaping student interests.

The fourth group included students whose decision to study Israel and Palestine was influenced by more pragmatic considerations such as course scheduling, graduation requirements, or credit fulfillment. These students often mentioned that the course “fit into their schedule” or was necessary to “fill a core goal, and this seemed interesting.” Additionally, for some, these courses were integral to their major or minor fields of study, such as History, Political Science, Global and International Studies, Jewish Studies, or Middle Eastern Studies.

In conclusion, the diverse reasons students choose to learn about Israel and Palestine at my institution underscore the multifaceted appeal of this subject. Whether driven by curiosity, personal connections, academic guidance, or practical necessities, students find these courses to provide valuable insights into the specific region and broader global and cultural contexts.

Changes in course 1: “Israel/Palestine: the war of 1948”

The course “Israel/Palestine: The War of 1948” is a History discipline offering.1 The course explores the background, key events, and aftermath of the 1948 war. In the past three times the course was offered, 47% of students were pursuing a History BA, 19% in Political Science, and 9% a degree in the School of Education. The remaining 25% of students were pursuing a BGS or a BA in Jewish Studies, Global and International Studies, Sociology, Anthropology, Architecture, or American Studies, or a major in the School of Journalism or School of Business. This diversity of academic background was noteworthy, which will be discussed further in the discussion section. During class discussions, students also shared their diverse ethnic, religious, and racial backgrounds.

When this class was first offered, the course design was based on backward design (McTighe and Thomas, 2003). I started with planning week by week. The weekly readings, lecture content, in-class components, and assignments focused on achieving specific weekly goals. The weekly goals lead to achieving unit goals, leading to achieving course learning objectives. Assessment of student learning helped decide the proper assignments or tasks in class. In addition to learning outcomes directly connected to the war, its background, causes, and consequences, the learning outcomes also include learning skills such as using maps as a primary source and searching for and analyzing various primary sources.

In the second step of changes, I wanted to redesign the course while focusing on increased student engagement and success through inclusive teaching approaches. This change aimed to broaden the understanding of diversity in the classroom beyond the traditional point of view. Also, the change aimed to incorporate new pedagogical ideas in the classroom and the syllabus while thinking about diversity and inclusiveness and using best practices for dealing with complex situations in the classroom. I wanted my students to feel more comfortable during the group discussions and presentations of the projects in class. They should be able to express their diverse opinions, listen to other opinions that vary from their own, and have constructive discussions. This is relevant due to some students’ social identity, which is connected to the topics or the people discussed, the topic’s high profile in the daily news, and its relation to the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian reality.2 Considering these aspects, my goals were to improve the students’ retention, attendance, participation in the classroom, performance on the final assignment, and final grade.

Instead of the traditional mid-semester and final exams, I created a final assignment to increase engagement and retention. I added in-class activities like group discussions to increase student cooperation and improve active learning. Instead of two weekly 75-min lectures, almost each class session is now divided into 20–25 min of lecture by the professor, 25 min of in-class group work by students, 15–20 min of reflection on group work, and discussion by students, and 10 min of synthesizing and concluding the lecture and the group work. I scaffolded the final assignment into ten weekly steps to improve feedback and validation and provided timely feedback using revised rubrics. Students present their project progress twice in class. I added two opportunities for students to provide peer reviews of the final assignment presentations in class and two additional opportunities online. Finally, I provided optional engaging resources on the Canvas site, such as YouTube videos and podcasts, to increase task time.

Out of the abovementioned changes, I will focus on the class structure and the added in-class activities. These changes incorporated the dual narrative approach and critical-disciplinary approach derived from the practices of historians. Students are divided into four groups of 5–6 students each. Students are asked to read excerpts of up to one page of text from a primary source, review pictures, posters, or the like, or view a short video (about 5 min of reading/viewing time), which is connected to the readings of the week and the professor’s short lecture. A rotating recorder takes notes and then reports the outcome of the group work at the end of the activity to the entire class. Students’ work in this in-class activity varies. One example is to discuss answers to guided questions regarding the text, video or picture. For example, they read a poem by Mahmoud Darwish, “On this land,” and a poem by Gouri (2024), “Bab al Wad,” and discuss answers to questions such as regarding the buildup of the collective memory of Palestinian or Israeli narratives about the 1948 War.3 Other forms of sources are used, such as the discussion of the place of art and cartoon characters- Handhala by Naji al-Ali, who represents the Palestinians, and Srulik by Kariel Gardosh, who represents Israelis (Bae-Dimitriadis, 2024). Another example is when all groups of students are asked to read and analyze the same primary source, but each group does that from a different perspective of the parties involved. For example, in analyzing the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181 (2024), each group focuses on one of these perspectives: Palestinian, Zionist, British, and other (the UN, Arab League, etc.). A third example is analyzing various primary sources to assess their value in researching history, their limitations, and understanding the different narratives: archive documents, memos, videos, pictures, and posters.4 For example, the Al-Qawuqji (1972) memoirs or an IDF archive document about “Druze and Circacians in the IDF” (The IDF Spokesman Unit, 1977). A fourth example was to discuss primary sources while considering the competing two narratives, including the different views among Palestinians and Israelis regarding the topic discussed.5 For example, exploring the unsolved status of Palestinian refugees based on the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 (1948) and subsequent UN resolutions or by discussing personal stories of those affected.6

This major change in class structure, with the addition of in-class activities, required an assessment of the success of this change. The mid-semester survey of students in Spring 2020 revealed general satisfaction with the changes. Students’ responses are listed in Supplementary Table A2. Students enjoyed the in-class group work and listed a few advantages such as “[…] Letting us set the information ourselves […],” “[…] it gives us a chance to see and discuss things we otherwise might have missed,” and “[…] this is a larger class so it has to be broken into groups […].”

These comments were supported by the answers to the closed-ended questions, as reported in Supplementary Table A3. 80% of the students enjoyed the class and said it met their expectations. When asked about the in-class group work, 55% of the students mentioned that it was the most valuable part of the class and wanted it to continue until the end of the semester. However, 45% of the students said it was helpful in some class sessions, but group work was not necessarily valuable for all. Students reported being prepared for the discussion if they did most of the readings (55%) or all of the readings (35%). When asked about the value of group work, students indicate that it is helpful because they better understand a concept/idea/theory (58%), share their opinion (54%), better understand an event in history or a current event (50%), practice a skill (50%), learn something new (46%), and brainstorm and execute a project/presentation (21%).

However, some students felt that there were too many in-class discussions and preferred a longer lecture from the professor. Also, they noted that some of the primary sources discussed in class were unclear or not helpful. These reflections and others helped me better prepare for the next time the class was offered. Based on this feedback, the selection of primary sources was revised, a more systematic method to rotate the recorder was adopted, and the in-class activity was shortened in some class sessions. The improvements were made toward the next time the course was offered.

The mid-semester survey was repeated in Fall 2022. Students reflected on a good learning environment and a positive experience with the in-class activities. When asked about “Which aspects of this course did you find the most helpful to your learning?” students said it was primarily the in-class group work. They responded: “I found every aspect of this course helpful to my learning, but particularly the in-class discussions and lectures and the readings”; “Great use of groups, forcing students to talk and engage in class and then taking that element online”; “The set up was easy and not stressful or overwhelming.”7

Step 3 of improving the course focused on redesigning the final assignment to a digital humanities project. Their task was to examine the effect of the 1948 War on human development, such as changes in infrastructure and demographics. In previous semesters, students worked on comparing maps manually. The redesigned final assignment is to create and present a map, using a digital tool, of the consequences of the 1948 war on human development based on primary and secondary sources. Also, I provided the students with the option to publish their final projects on a website open to the public, which increased the enthusiasm of some of the students to work on it.8

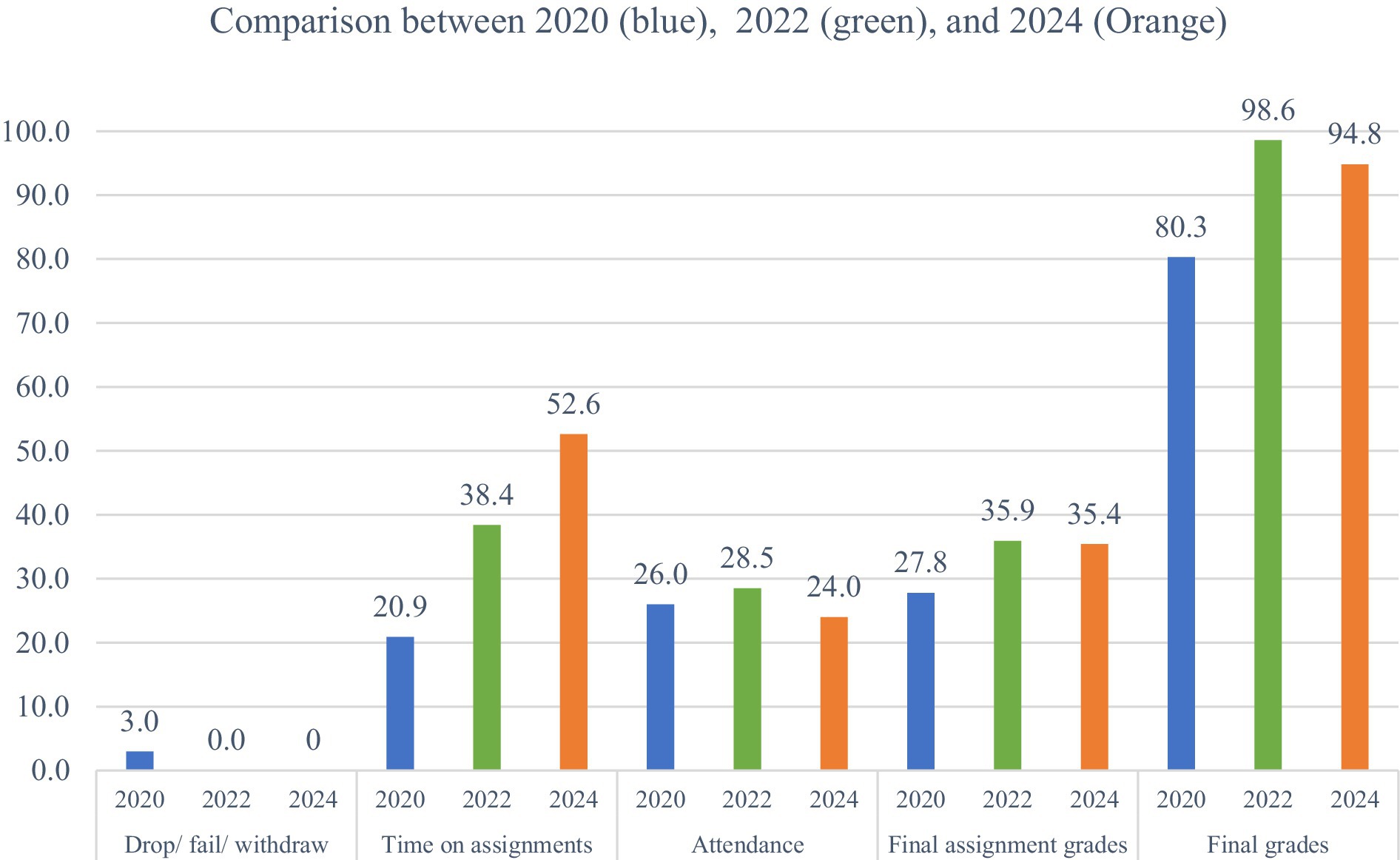

To evaluate the success of these changes in step 3, I compared the student performance in the classes of 2020, 2022 and 2024. Figure 1 shows the positive results of the changes. The results show improvement in “Drop/fail/withdraw”: from 3 in 2020 to none in 2022 and 2024, improvement regarding time on assignments: increase from 20.9 h in 2020 to 38.4 in 2022 and further increase to 52.6 in 2024, and improvement in in-person attendance: from 26 class sessions per student in 2020 to 28.5 in 2022. However, in 2024, there was a decrease in average attendance to 24 class sessions, which requires further examination. This will be discussed in the discussion section. Finally, there was an improvement in grades. In the grades of the final assignment, there was an increase from 27.8 in 2020 to 35.9 in 2022. In 2024, the average grade of the final assignment was 35.4, which is similar to that of 2022. Finally, the results show improvement in final grades for all students: from 80.3 in 2020 to 98.6 in 2022. In 2024, the final grades remained higher than in 2020 but slightly lower than in 2022 at 94.8. In conclusion, redesigning this class to become more inclusive has helped all students perform better regarding time spent on tasks, attendance, final assignments, and final grades.

Figure 1. Results for course 1: “Israel/Palestine: The War of 1948”- Spring 2020, Fall 2022, and Spring 2024. For more details, see Supplementary Table A4; “Drop/Fail/Withdraw” is by the number of students; “Time on assignments” is the average in hours; “Attendance” is the average number of class sessions attended (out of 30); “Final assignment grades” are by average point (max 36); “Final grades” are the average of student grades (max 100).

Changes in course 2: “Israel: from idea to state”

The course “Israel: From Idea to State” is an interdisciplinary course with History and Political Science as the primary disciplines at its focus.9 The course explores Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people and its challenges in balancing Jewish and democratic values.

In the past three times the course was offered, 30% of the students pursued a BA in Political Science, 22% in History, 8% in Global and International Studies, and 8% in various majors in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. The remaining 32% of students were pursuing a BGS or BA in Jewish Studies, Sociology, Anthropology, Architecture, Biology, or a major in the School of Business or School of Education.

In redesigning this course, the three steps mentioned above were repeated. The first step was backward design. In step 2, I repeated the changes as in the other course described above, with some differences. Mainly, I transformed the course to meet the General Education requirement at my institution for oral communication while adding assignments for students to present orally, each with a different purpose and audience. For clarity, here is the list of changes conducted in Step 2. To improve engagement and retention, I did not include mid-semester or final exams and instead created a final assignment. I added group discussions to improve student cooperation and active learning in each class session. I created teams that run for the entire semester and are used in class discussions, as well as an assignment that is a team presentation. Each team focused on one of the six major divides in Israeli society: political, national, ethnic, religious, socio-economic, and gender (Zeedan, 2024). This created more personal connections for students with their peers. Also, I added an assignment that was a team presentation in class, for which students cooperated outside of the classroom. To improve prompt feedback and validation, I scaffolded the final assignment into ten weekly steps and provided timely feedback while using revised rubrics. Students present their progress in class and then post another draft online. I added two opportunities for students to provide peer reviews of the final assignment presentations in class and two additional opportunities online. To improve time on tasks, I provided optional engaging resources on the Canvas site, such as YouTube videos and podcasts.

In Step 3, the final assignment was redesigned into a podcast project, scaffolded into 12 steps. The target audience is the general public. Students start working on it during the first week of the semester and receive feedback for each step. Students gain experience from presenting the first two assignments and from presenting a draft of the final project, getting feedback on them, and getting better prepared for their final version. This structure allows weekly feedback on progress, enabling the students to revise their work multiple times. Finally, the course allows the students to publish their final projects on a website open to the public, which increases the enthusiasm of some of the students to work on it. By sharing the course’s success results, the course can help other students and faculty members improve their course design and teaching strategies.

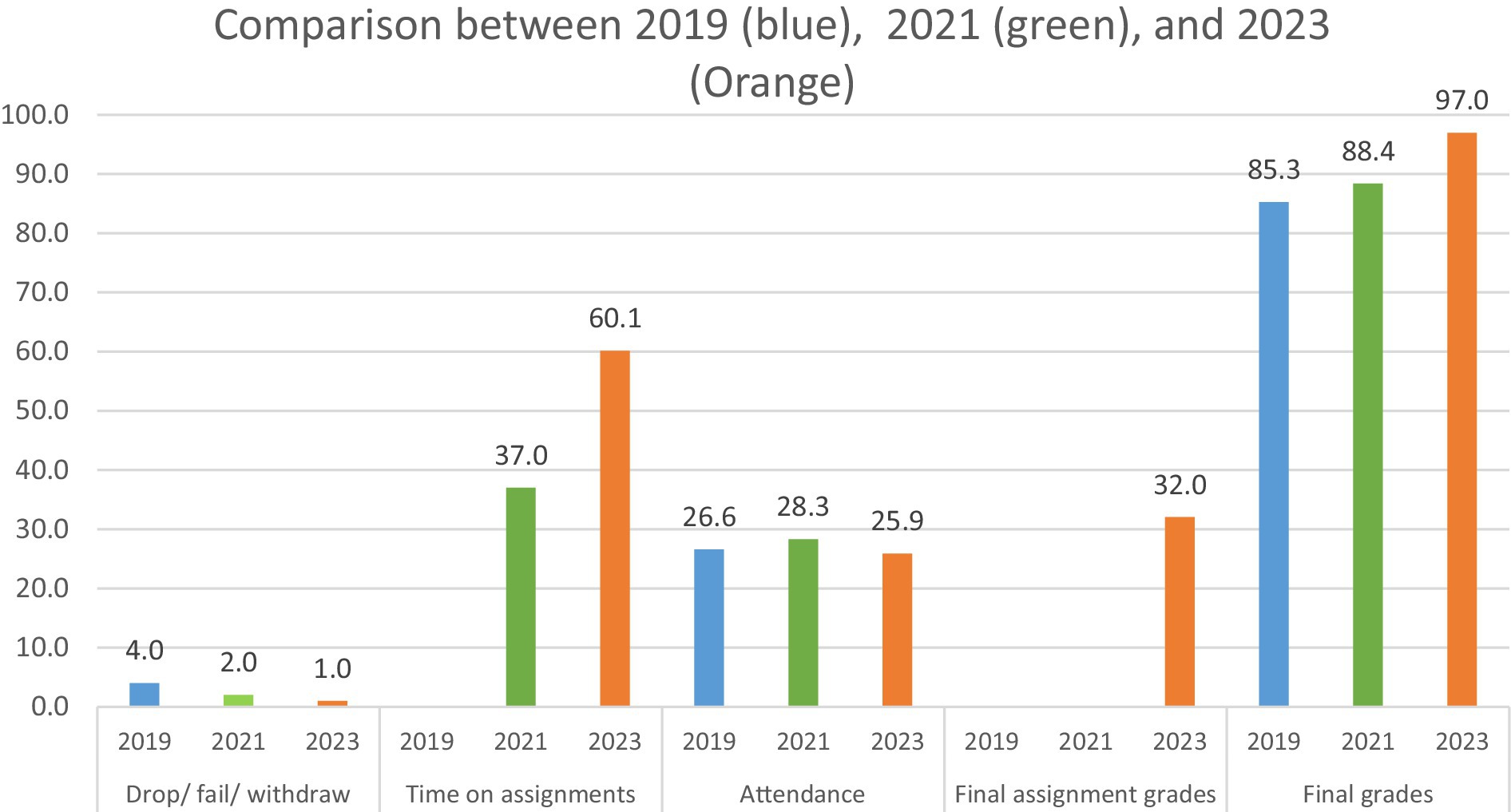

To evaluate the success of these changes in step 3, I compared the performance of the students in the classes of 2019, 2021, and 2023. Figure 2 shows the positive results of the changes. The results show improvement in “Drop/fail/withdraw” from 4 in 2019 to one in 2023, improvement regarding time on assignments: increase from 37 h in 2021 to 60.1 in 2023, and improvement in in-person attendance from 26.6 class sessions per student in 2019 to 28.3 in 2021. However, in 2023, there was a decrease in average attendance to 25.9 class sessions, similar to the results reported above for the other course. Finally, there was an improvement in grades. The results show improvement in final grades for all students, from 85.3 in 2019 to 97.0 in 2023. In conclusion, redesigning this class to become more inclusive has helped all students perform better regarding time spent on tasks, attendance, final assignments, and final grades.

Figure 2. Results for course 2: “Israel: From Idea to State”- Fall 2019, Spring 2021, and Spring 2023. For more details, see Supplementary Table A5. “Drop/Fail/Withdraw” is by the number of students; “Time on assignments” is the average in hours; “Attendance” is the average number of class sessions attended (out of 30); “Final assignment grades” are by average point (max 36); “Final grades” are the average of student grades (max 100).

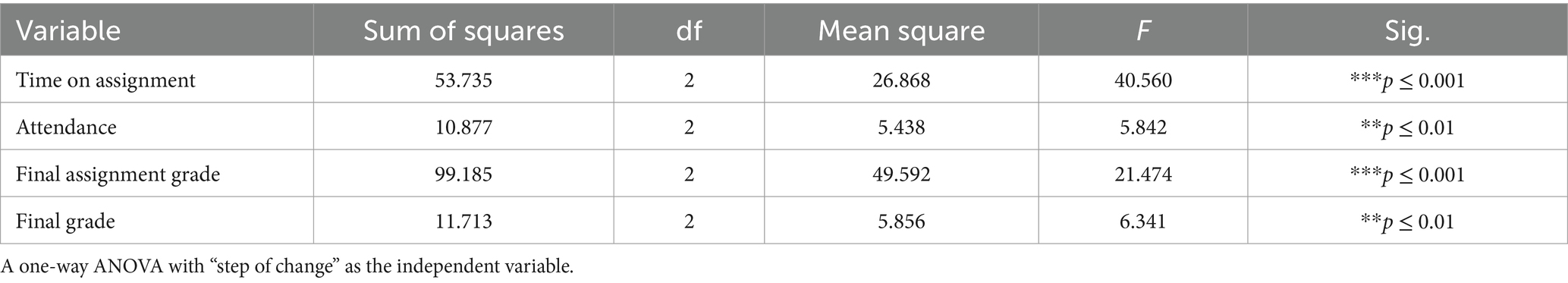

The last step to measure the success of the changes in the two courses was using a one-way ANOVA. This was conducted to examine the effect of the step of change on time spent on assignments, attendance, final assignment grade, and final grade. The analysis revealed significant differences between steps for all variables. The results are shown in Table 1. Supplementary Table A6 shows the details of the different steps used to make changes to the courses.

For time on assignment, the ANOVA yielded a significant effect of the step of change (F = 40.560, ***p ≤ 0.001), indicating that students spent increasingly more time on their assignments as they progressed through the steps. The large effect size (Eta-squared = 0.416) highlights the substantial impact of the step of change on time spent on assignments.

In terms of attendance, the ANOVA was also significant (F = 5.842, **p ≤ 0.01), though the effect size was smaller (Eta-squared = 0.093). This suggests that changes in the step of progress led to some improvement in attendance, albeit with a minor effect compared to assignment-related outcomes. This could be because high attendance was observed, and variation was insignificant in our sample due to a university-wide policy change regarding attendance and how it is documented and measured during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

For final assignment grades, the analysis found significant differences (F = 21.474, ***p ≤ 0.001), with a medium effect size (Eta-squared = 0.274), indicating that students’ performance on final assignments improved as I progressed through the steps of change.

Finally, final grades also showed significant differences (F = 6.341, **p ≤ 0.01), with a small but significant effect size (Eta-squared = 0.100), suggesting that overall course performance was influenced by the step of change, though less strongly than time spent on assignments or assignment grades.

These results suggest that the step of change has a robust influence on students’ engagement with assignments and their performance, while the impact on attendance, though significant, is less pronounced. In conclusion, the results indicate that the pedagogical changes employed were critical in influencing assignment time, assignment performance, and final grades. The significant differnces demonstrate that as students advance through structured learning stages and allocate more time to their work, they achieve better outcomes. While attendance does not appear to significantly impact performance, the findings emphasize the importance of active engagement with assignments. These insights suggest that fostering incremental progress and encouraging dedicated time on tasks can enhance academic success.

Further discussion

The findings of this study align with and extend the existing scholarly discourse on effective pedagogical strategies for teaching courses about Israel and Palestine. This study confirmed and built upon the insights from the literature by integrating dual narrative and critical-disciplinary approaches within an inclusive learning environment. These methods significantly enhanced student engagement, critical thinking, and academic success. This conclusion is supported by both qualitative feedback and quantitative data, revealing strong correlations between pedagogical changes, time spent on assignments, and final grades, as outlined in the statistical analysis.

The dual narrative approach, which scholars like Penslar (2021) have discussed for its ability to present competing Israeli and Palestinian perspectives, was found to deepen students’ understanding of the conflict. This study corroborates findings from scholars such as Eid (2010), who noted that the dual narrative fosters an environment where students can better critically assess both sides, leading to more balanced and nuanced perspectives. The significant increase in students’ ability to overcome biases and engage with conflicting narratives, reflected in the survey results, demonstrates the educational value of this approach. However, the study also revealed challenges among students with deeply held beliefs, as noted by Segal (2019). Nevertheless, the study found that inclusive pedagogical strategies effectively mitigated any such resistance, supporting existing literature and contributing new insights into the practical handling of contentious classroom discussions.

The critical-disciplinary approach, grounded in historians’ practices (Goldberg and Ron, 2014), further proved invaluable. This method encouraged students to engage deeply with multiple sources, enhancing their ability to navigate complex historical narratives. The study found that students became more adept at identifying biases and questioning the reliability of sources—skills emphasized by Ambrose et al. (2010). These findings echo the broader consensus in the literature that critical thinking is essential for students engaging with complex issues like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Furthermore, this study strongly reinforces the literature on the importance of an inclusive learning environment that is student-centered (Russo-Tait, 2023) with an inclusive mindset for all pedagogical decisions (Sathy and Hogan, 2019), and is explicitly centralizing (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 171). Scholars like Boaler and Sengupta-Irving (2016) have highlighted the value of equity-focused teaching practices, and this study provides additional evidence of their impact. The findings revealed that inclusive practices, such as collaborative group work and active learning, significantly increased student engagement and participation, aligning with Russo-Tait (2023) findings on the influence of inclusive teaching on student success. The quantitative data, with a strong correlation between implementing these practices and improved final grades, further emphasizes their effectiveness.

The use of experiential learning strategies, as supported by Greene and Boler (2004), was another crucial aspect of this study. The study found that students’ engagement and retention were significantly enhanced by incorporating digital tools and scaffolded assignments. The concept of “pedagogical discomfort” was evident as students navigated the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, leading to deeper critical engagement. As noted in the literature (Sathy and Hogan, 2019), the scaffolding of assignments also reduced anxiety. It allowed for continuous improvement, with statistical evidence showing improvements in time spent on assignments and final assignment grades.

The findings of this study correspond closely with the four pillars of inclusive teaching strategies (University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, 2024): content, instructional practices, instructor-student connections, and student–student connections. First, in terms of content, the integration of dual narratives ensured that diverse perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict were represented in all aspects of the class, allowing students to engage with Israeli and Palestinian viewpoints. Second, the instructional practices employed, such as scaffolded assignments and group discussions, were designed to be equitable, providing structure and continuous feedback, which helped reduce anxiety and allowed students to improve progressively. Third, instructor-student connections were strengthened through personalized and timely feedback and active learning techniques, facilitating a supportive and responsive learning environment. Students reported feeling more engaged and connected to the material due to the frequent opportunities for interaction with the instructor. Finally, student–student connections were enhanced through collaborative group work, which fostered peer-to-peer learning and mutual respect. These connections, in the classroom, in group work, and online opportunities, contributed to a sense of belonging and helped students navigate the sensitive nature of the course material with greater comfort and openness.

For instructors interested in making similar methodological adjustments, I recommend following my approach detailed in this study: a three-step approach to address specific challenges. First, it is recommended to ensure diverse perspectives by incorporating Israeli, Palestinian, and international voices when selecting primary and secondary sources. This balance is crucial for fostering critical engagement. After introducing these materials, it is best to conduct self-research and gather mid-semester feedback to evaluate the effect on student participation. The second step is to adjust group work dynamics by intentionally mixing students from diverse backgrounds and assigning a rotating recorder to encourage equitable participation. After implementing these changes, end-of-semester surveys should be used to assess the success of the changes and make further adjustments based on the feedback in future semesters. This iterative process allows for a more inclusive and effective learning environment.

The findings presented in this study are significant due to the diversity of academic backgrounds and ethnic, religious, and racial backgrounds among the students in the studied courses. Students in the study expressed a wide range of motivations for learning about Israel and Palestine, highlighting the significance of their diverse backgrounds. Their interests spanned from a general curiosity about other cultures and international politics to more specific desires to deepen their understanding of Middle Eastern conflicts. Some students were motivated by personal or familial connections to Israel or Palestine, while others sought to explore political complexities and international dynamics. The diversity of backgrounds among students played a crucial role in shaping these responses, reflecting their varied perspectives and learning goals. This diversity, including the academic one, allows further exploration into how students’ backgrounds influence their engagement with complex geopolitical subjects. Future studies could investigate how such diversity affects classroom dynamics, group discussions, and students’ perceptions of controversial topics. Additionally, understanding the role of personal experiences and pre-existing knowledge could provide insights into how to design better inclusive courses that address the needs of a heterogeneous student body. In courses addressing politically charged topics like Israel and Palestine, student resistance—particularly from those with deeply held beliefs—is a significant challenge. This could be manifested in classroom discussions where students struggled to engage with perspectives that conflicted with their personal or political identities. As suggested in this study, several strategies were employed to mitigate this. First, creating a respectful and inclusive learning environment was crucial. Ground rules for respectful dialogue were established early in the course, emphasizing the value of multiple viewpoints and encouraging students to approach opposing perspectives with curiosity rather than defensiveness.

Additionally, structured activities based on the dual narrative approach allowed students to engage with conflicting narratives in a more controlled manner. This approach gave them space to explore uncomfortable topics without feeling personally attacked. Diverse readings and in-class content helped students process their discomfort privately, which made them more open to engaging with differing viewpoints in group discussions. Scaffolded assignments gradually introduced more contentious topics, which allowed students to build confidence and critical thinking skills, reducing anxiety and defensiveness. The impact of these strategies on the overall learning environment was positive, as presented in this study. Both courses fostered a more open and dynamic classroom culture by framing complex topics as a learning opportunity and giving students tools to navigate them.

While this study’s findings provide valuable insights into pedagogical strategies for teaching courses on Israel and Palestine, it is essential to acknowledge that these results may not be directly transferable to other disciplines or institutions without adaptation. The specific context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict presents unique challenges that may not be present in other fields of study. Another limitation is the sample size and demographic scope, as the data was drawn from two specific undergraduate courses at one institution. This restricts the generalizability of the findings to other educational settings with more diverse student populations.

However, the core principles of active learning, inclusive teaching practices, and the dual narrative approach can be adapted to other disciplines. For example, the dual narrative method, which facilitates engagement with multiple perspectives, could be used in other universities teaching about the conflict and in courses on other contentious topics. In these contexts, encouraging students to assess competing viewpoints critically would promote balanced, reflective discussions. To extend the applicability of the findings, future research could explore how inclusive pedagogical strategies like scaffolded assignments, reflective writing, and structured debates impact student engagement and critical thinking in other academic settings. Additionally, adapting these strategies to institutions with more diverse student populations or courses with different political sensitivity levels could provide further insights into their effectiveness across various contexts. Considering these broader applications, the pedagogical changes presented in this study could inform teaching practices beyond the specific context of Israel-Palestine studies.

Additionally, the study primarily involved elective courses, meaning that students self-selected to the courses, possibly leading to higher initial engagement levels or openness than required courses in other departments. Future research should address these limitations by employing longitudinal methods and expanding the demographic scope to include a range of institutions and course types.

In terms of remaining gaps, while this study highlighted the effectiveness of the dual narrative and critical-disciplinary approaches, there is still a need for further exploration of how these strategies can be adapted for different academic disciplines and learning environments. Moreover, the issue of student resistance, particularly in contexts where personal or political identities are strongly tied to the subject matter, remains an area for deeper investigation. Further research should also examine the long-term impact of these pedagogical strategies on students’ critical thinking skills and engagement with broader global issues beyond the classroom.

Future research could investigate the development of students’ expressive abilities in active learning settings, particularly in courses exploring complex geopolitical issues like Israel and Palestine. Further exploration could examine how their ability to articulate nuanced perspectives evolves. Longitudinal studies or reflective assessments could track this development, providing insights into how scaffolding, collaborative group work, and other active learning strategies contribute to students’ growth in expressing complex ideas. Such research would deepen our understanding of how inclusive and active learning environments support students in becoming more confident and articulate in discussing controversial topics. In conclusion, this study confirms much of the existing literature regarding the benefits of dual narrative, critical-disciplinary approaches, and inclusive learning environments while providing new insights into their implementation. These findings underscore the importance of innovative pedagogical practices in fostering student engagement and success, mainly when teaching complex and contentious subjects like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Kansas: Human Research Protection Program (785–864-7385, aXJiQGt1LmVkdQ==). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because IRB protocol approved for previously collected data with very minimal risk to participants and no mechanism to current contact of participants in the study.

Author contributions

RZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the reviewers for their valuable suggestions, which significantly enhanced the final work. He also extends his gratitude to his colleagues, Dr. RB Perelmutter and Dr. Wail S. Hassan, for their insightful feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1497045/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^This course was redesigned with the help of the KU Center for Teaching Excellence and the KU Libraries.

2. ^This course was last taught in Spring 2024, during protests on US university campuses related to the War in the Gaza Strip.

3. ^On the importance of mixing historical and literary texts, see: Knopf-Newman (2011, p. 103).

4. ^Other examples of such primary sources for this course include: The Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916), McMahon–Hussein Correspondence (1915–1916), Balfour Declaration (1917), the Agreement Between Emir Feisal and Dr. Weizmann (1919), Mandate for Palestine and Transjordan Memorandum by the League of Nations (1922), Israeli Declaration of Independence (1948), Arab League (1948), posters from The Palestine Poster Project Archives (2024) and The Israeli National Library (2024), Egyptian-Israeli General Armistice Agreement (1949), Lebanese-Israeli General Armistice Agreement (1949), Israeli-Syrian General Armistice Agreement (1949), Jordanian-Israeli General Armistice Agreement (1949).

5. ^On the idea of students’ work to support an argument and simultaneously to present counterarguments, see, for example, Singh (2021, p. 33).

6. ^On the idea of personal narratives, see, for example, Dajani Daoudi and Barakat (2013). Examples of such narrative stories: Kanafani (2013) and Kaniuk (2012); On including personal stories in teaching the conflict, see: Bar-On (2011).

7. ^Other answers included: “I thought the learning environment of the class was excellent!”; “Very thorough lectures, first hand knowledge”; “The examination of primary source material.”; “The group’s activities.”; “The readings were very informative.”; “Group activities and the presentations.”

8. ^Results are published on a dedicated website. An article focusing on this redesigned assignment is under review.

9. ^This course was redesigned with the help of the KU Center for Teaching Excellence and the KU Libraries.

References

Agreement Between Emir Feisal and Dr. Weizmann (1919). Available at: https://www.panarchy.org/variousauthors/balfourdeclaration.html (Accessed September 15, 2024)

Ambrose, S., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., and Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for innovative teaching. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley.

Arab League. “Cablegram dated 15 May 1948 addressed to the secretary-general by the secretary-general of the league of Arab states.” (1948). Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/649818?v=pdf (Accessed 15 September 2024).

Aronson, J. K., Koren, A., and Saxe, L. (2013). Teaching Israel at American universities: growth, placement, and future prospects. Israel Stud. 18, 158–178. doi: 10.2979/israelstudies.18.3.158

Bae-Dimitriadis, M. (2024). Teaching peace education through art. Art Educ. 77, 4–7. doi: 10.1080/00043125.2024.2302296

Balfour Declaration (1917). Available at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/balfour.asp (Accessed 15 September 2024).

Bar-On, M. (2006). Conflicting narratives or narratives of a conflict: Can the Zionist and Palestinian narratives of the 1948 war be bridged?. In Rotberg, R. I. (Ed.). Israeli and Palestinian narratives of conflict: History’s double helix Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 142–173.

Bar-On, D. (2011). Storytelling and Multiple Narratives in Conflict Situations. In: Salamon, G. (ed.). Handbook on peace education. New York: Psychology Press, 199–212.

Bar-Siman-Tov, Y. (1994). The Arab—Israeli conflict: learning conflict resolution. J. Peace Res. 31, 75–92. doi: 10.1177/0022343394031001007

Boaler, J., and Sengupta-Irving, T. (2016). The many colors of algebra: the impact of equity focused teaching upon student learning and engagement. J. Math. Behav. 41, 179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jmathb.2015.10.007

Borhani, S. H. (2015). Palestine studies in Western academia: shifting a paradigm? Iran. Rev. Foreign Affairs 5, 119–150.

Borhani, S. H. (2016). Biases and the question of Palestine/Israel: textbook treatment of the Question's history in Western universities. J. Holy Land Palestine Stud. 15, 225–247. doi: 10.3366/hlps.2016.0142

Chickering, A. W., and Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bull. 3:39.

Dajani Daoudi, M. S., and Barakat, Z. M. (2013). Israelis and Palestinians: contested narratives. Israel Stud. 18, 53–69. doi: 10.2979/israelstudies.18.2.53

Darwish, Mahmoud, “On this land.” Available at: https://www.aldiwan.net/poem9094.html (Accessed June 7, 2024).

Dessel, A. B., Ahmad, M. Y. A., Dembo, R., and Hagai, E. B. (2017). Support for Palestinians among Jewish Americans: the importance of education and contact. J. Peace Educ. 14, 347–369. doi: 10.1080/17400201.2017.1345726

Dittmar, L. (2013). Teaching notes: side by side: Israeli and Palestinian cinema. Radic. Teach. 95, 70–74. doi: 10.5406/radicalteacher.95.0070

Eddy, S. L., and Hogan, K. A. (2014). "getting under the hood: how and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE 13, 453–468. doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-03-0050

Egyptian-Israeli General Armistice Agreement (1949). Available at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/arm01.asp#:~:text=No%20element%20of%20the%20land,shall%20advance%20beyond%20or%20pass (Accessed September 15, 2024)

Eid, N. (2010). The inner conflict: how Palestinian students in Israel react to the dual narrative approach concerning the events of 1948. J. Educ. Media Memory Soc. 2, 55–77. doi: 10.3167/jemms.2010.020104

Goldberg, T. (2014). Looking at their side of the conflict? Effects of single versus multiple perspective history teaching on Jewish and Arab adolescents’ attitude to out-group narratives and in-group responsibility. Intercult. Educ. 25, 453–467. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2014.990230

Goldberg, T., and Ron, Y. (2014). ‘Look, each side says something different’: the impact of competing history teaching approaches on Jewish and Arab adolescents’ discussions of the Jewish–Arab conflict. J. Peace Educ. 11, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/17400201.2013.777897

Gouri, H., (2024). Bab al Wad. Available at: https://tarbutil.cet.ac.il/paskol/%D7%91%D7%90%D7%91-%D7%90%D7%9C-%D7%95%D7%95%D7%90%D7%93/ (Accessed June 7, 2024).

Head, N. (2020). A “pedagogy of discomfort”? Experiential learning and conflict analysis in Israel-Palestine. Int. Stud. Perspect. 21, 78–96. doi: 10.1093/isp/ekz026

Israeli Declaration of Independence (1948). Available at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/israel.asp (Accessed September 15, 2024)

Israeli-Syrian General Armistice Agreement (1949). Available at: https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/default/files/document/files/2024/05/il20sy490720israeli-syrian20general20armistice20agreement.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2024)

Jordanian-Israeli General Armistice Agreement (1949). https://ecf.org.il/issues/issue/175#:~:text=An%20armistice%20agreement%20concluding%20the,certain%20positions%20from%20Iraqi%20forces (Accessed September 15, 2024)

Kinzie, J., Gonyea, R., Shoup, R., and Kuh, G. D. (2008). Promoting persistence and success of underrepresented students: lessons for teaching and learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2008, 21–38. doi: 10.1002/tl.323

Kirschner, S. A. (2012). "teaching the Middle East: pedagogy in a charged classroom." PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 45, 753–758. doi: 10.1017/S1049096512000753

Knopf-Newman, M. J. (2011). The politics of teaching Palestine to Americans: Addressing pedagogical strategies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kuh, G. D., Nelson Laird, T. F., and Umbach, P. D. (2004). Aligning faculty activities & student behavior: realizing the promise of greater expectations. Lib. Educ. 90, 24–31.

Lazarus, N. (2008). Making peace with the duel of narratives: dual-narrative texts for teaching the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israel Studies Forum 23, 107–124. doi: 10.3167/isf.2008.230106

Lebanese-Israeli General Armistice Agreement. (1949). Available at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/arm02.asp (Accessed September 15, 2024)

Longwell-Grice, R., Adsitt, N. Z., Mullins, K., and Serrata, W. (2016). The first ones: three studies on first-generation college students. Nacada J. 36, 34–46. doi: 10.12930/NACADA-13-028

Longwell-Grice, R., and Longwell-Grice, H. (2008). Testing Tinto: how do retention theories work for first-generation, working-class students? J. College Student Retention 9, 407–420. doi: 10.2190/CS.9.4.a

Mandate for Palestine and Transjordan Memorandum by the League of Nations. (1922). Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/829707?ln=en&v=pdf (Accessed July 24, 2022).

McMahon–Hussein Correspondence (1915–1916). Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/829707?ln=en&v=pdf (Accessed September 15, 2024)

McTighe, J., and Thomas, R. S. (2003). Backward design for forward action. Educ. Leadersh. 60, 52–55.

Mousavi, M. A., and Kadkhodaee, E. (2016). Academic contact: a theoretical approach to Israel studies in American universities. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 7, 243–257.

Muhtaseb, A., Algan, E., and Bennett, A. (2014). Teaching media and culture of the Middle East to American students. Int. Res. Rev. 4, 8–17.

Nikolenyi, C., and Kabalo, P. (2019). Israel studies: “Here” and “there”. Contemp. Rev. Middle East 6, 218–223. doi: 10.1177/2347798919873219

Pappé, I., Dana, T., and Najjab, N. N. (2024). Palestine studies, knowledge production, and the struggle for decolonisation. Middle East Critique 33, 173–193. doi: 10.1080/19436149.2024.2342189

Penslar, D. (2021). “Chapter seven toward a field of Israel/Palestine studies” in The Arab and Jewish questions: Geographies of engagement in Palestine and beyond. eds. B. Bashir and L. Farsakh (Columbia University Press), 173–200. doi: 10.7312/bash19920-009

Russo-Tait, T. (2023). Science faculty conceptions of equity and their association to teaching practices. Sci. Educ. 107, 427–458. doi: 10.1002/sce.21781

Samaras, A. P., and Freese, A. R. (2006). Self-study of teaching practices primer. Peter Lang Group AG.

Sathy, V., and Hogan, K. A. (2019). How to make your teaching more inclusive. Chron. High. Educ. 7. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-make-your-teaching-more-inclusive/ (Accessed November 19, 2024).

Schneider, E. (2020). It changed my sympathy, not my opinion: alternative Jewish tourism to the occupied Palestinian territories. Sociol. Focus 53, 378–398. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2020.1823286

Segal, D. A. (2019). Teaching Palestine-Israel: a pedagogy of delay and suspension. Rev. Middle East Stud. 53, 83–88. doi: 10.1017/rms.2019.15

Singh, R. (2021). Arguing BDS in the undergraduate seminar. Rev. Middle East Stud. 55, 28–34. doi: 10.1017/rms.2021.36

Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916). The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Available at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/sykes.asp (Accessed September 15, 2024).

The IDF Spokesman Unit. (1977). “Druze and Circassians in the IDF”, IDF archive, June 1, 1977, box 2010-7-16 (document in English in the original).

The Israeli National Library. (2024). Available at: https://www.nli.org.il/en/discover/posters (Accessed September 15, 2024).

The Palestine Poster Project Archives. (2024). Available at: https://www.palestineposterproject.org/ (Accessed August 7, 2024).

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181. (2024). Available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ARES181II.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2024)

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 (1948). Available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ARES194III.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2024).

University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching. (2024). Available at: https://crlt.umich.edu/overview-equity-focused-teaching-michigan (Accessed August 7, 2024).

Keywords: equity-focused teaching, inclusion and diversity, Israel studies, Palestine studies, group discussions, student engagement, experiential learning

Citation: Zeedan R (2024) College student engagement and success through inclusive learning environment and experiential learning in courses about Israel and Palestine. Front. Educ. 9:1497045. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1497045

Edited by:

Elizabeth Alvey, The University of Sheffield, United KingdomReviewed by:

Rebecca Lewis, University of East Anglia, United KingdomLaurel Chaproniere, Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Zeedan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rami Zeedan, cnplZWRhbkBrdS5lZHU=

Rami Zeedan

Rami Zeedan