- 1Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, and Special Education, Faculty of Education, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Negative school integration experiences can compromise the healthy development of newcomer youth. Little research has explored what affects their experiences; even less has engaged youth in the research process. This study investigated the school integration experiences of French-speaking newcomer youth in a predominantly anglophone Canadian province using the Arts-Based Engagement Ethnography research method. We explored: (1) How do newcomer youth experience a public francophone school? and (2) How do these experiences influence their positive integration into the francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province? Data from artifacts, interviews, and planned group discussions were organized into four structures: (a) navigating school integration challenges, (b) negotiating identity, (c) confronting biases, and (d) helping other newcomer youth. Underlying patterns painted a rich portrait of newcomer youth school integration experiences, which informed their emerging identity. Findings point to needed changes to supports and services offered to newcomer youth integrating into the francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province.

1 Introduction

A recent census (Statistics Canada, 2021) found that nearly 1.6 million of the 8.4 million newcomers (i.e., immigrants, refugees) admitted to Canada from 2016 to 2021 were youth between the ages of 15 and 24. Newcomer youth1 (NY) comprised nearly one-fifth of all newcomers to Canada in recent years, second only to adults ages 25–44 who comprised the largest admitted group. This significant population is poised to benefit from Canada’s educational system and contribute to society. However, they are also at risk for negative school integration experiences that can compromise their healthy development and wellbeing (Patel et al., 2023). Despite these risks and the pressing need to better support NY, research exploring factors affecting their school integration experiences is limited (Kaufmann, 2021). Moreover, this research base reflects a dearth of direct learning from and with NY themselves (Palova et al., 2023; Suárez-Orozco and Marks, 2016).

Canada has two official languages—French and English—so it welcomes some of its newcomers from countries where French is an official language. To support the country’s bilingualism mandate, Canada has developed a strategy to attract more French-speaking immigrants, including a recent $40 million investment in settlement services for newcomers who choose to reside outside of the predominantly francophone province of Quebec [Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), 2019]. Consequently, a portion of French-speaking NY face the challenge of integrating into the francophone school system in provinces and territories where English is the majority language. The successful integration of French-speaking NY into francophone school systems is central to sustaining bilingualism in Canada. However, little is known about their school integration experiences (Palova et al., 2023) which can be complicated by several factors: the challenge of developing and/or maintaining competence in both French and English—languages that may be their second or third—while also navigating a multicultural environment that further places them in the minority (Jacquet et al., 2008; Palova et al., 2023).

The francophone community in the predominantly anglophone province of British Columbia (BC) is the fourth largest in Canada, with over 300,000 French speakers—a figure that represents a 39% increase in the last decade (Government of British Columbia, 2019). Given this increase, it is not surprising that both francophone and French immersion school programs are currently operating above capacity (La Fédération des Francophones de la Colombie-Britannique, 2017). Of the over 60,000 students attending these programs, an estimated 25% are NY (Houle et al., 2014). Providing culturally responsive education in both French and English to NY integrating into this school system in a predominantly anglophone province is challenging but crucial. This significant population can play a pivotal role in the social fabric and success of both BC and Canadian society (Government of Canada, 2018; Hussen, 2018; Lupul, 2019). However, this potential contribution hinges on the educational, occupational, and civic opportunities available to them (Suárez-Orozco and Marks, 2016).

Palova et al. (2023) identified both theoretical and methodological gaps in the limited research exploring school integration experiences of francophone NY in predominantly anglophone provinces and territories. For example, they found a lack of research specifically investigating the school integration experiences of francophone NY, with most research analyzing data from newcomers of diverse backgrounds. This makes it difficult to isolate the unique challenges faced by this group, limiting the ability to influence policy and practice effectively. Further, the authors noted that the qualitative research methods employed in the studies were overwhelmingly traditional in nature—namely interviews, participant observations, and document analyses. While valid, these approaches have been criticized for not centering the participant or providing them with sufficient agency in the research process (Goopy and Kassan, 2019). Thus, there is a need for research that explores the school integration experiences of French-speaking NY in predominantly anglophone provinces and territories employing participatory research methods that bolster their agency and authenticity in the research process. The current study aims to bridge these gaps by applying an Arts-Based Engagement Ethnography (ABEE; Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020) to explore the school integration experiences of French-speaking NY in a public francophone school system located in the predominantly anglophone province of BC.

1.1 Newcomer youth school integration

Newcomer youth face the dual challenge of adapting to a host culture while simultaneously navigating the developmental changes of adolescence. Transitioning to secondary school is, on its own, challenging for this group (Bharara, 2020); it becomes more complex when coupled with the need to adjust to a new sociocultural environment. In school, NY must navigate academic, social, emotional, and linguistic transitions that go beyond the typical challenges of adolescence (Anisef et al., 2010; Li, 2010; Naraghi, 2013; Patel et al., 2023). The ability of NY to successfully navigate these transitions plays an important role in their school and life success (Patel et al., 2023; Salehi, 2010). Thus, research focused on the process of school integration emerged to explore the experiences of NY with the aim of enhancing support services through changes to policy and practice (Gallucci and Kassan, 2019).

Extant literature has identified several challenges to NY school integration. Chief among these is language (Wadsworth et al., 2008), and unfamiliarity with the education system (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010) and local norms (Chen, 2000). Moreover, the new school system may not assess prior education appropriately, leading to grade placements that do not match NY ability (Khanlou et al., 2009; Ngo and Schleifer, 2005). Furthermore, NY who now find themselves in racialized and/or minoritized groups face additional challenges related to prejudice, discrimination, and racism (Berry and Sabatier, 2010; Closs et al., 2001; Kaufmann, 2021). The barriers and challenges faced by NY in the process of school integration can compound, leading to poor or adverse outcomes including mental illness (Shakya et al., 2010), school dropout (Anisef et al., 2010), and gang involvement (Rossiter and Rossiter, 2009).

Less is known about the school integration experiences of French-speaking NY in the bilingual country of Canada, and less still about their experiences integrating into the francophone school system in predominantly anglophone contexts. Some research has explored the integration experiences of NY in the predominantly francophone province of Quebec (e.g., Allen, 2007; Berry and Sabatier, 2010). In Allen’s (2007) study of NY school integration experiences in Quebec’s school system, she identified themes of exclusion related to their French-language proficiency. The NY she interviewed related how they were placed in segregated educational settings until they were able to demonstrate the French-language proficiency required to join mainstream classrooms. Other research with NY integrating into francophone school systems in predominantly anglophone contexts has found similar accounts of exclusion. For example, in their review of 22 studies, Palova et al. (2023) identified a theme of “multiple marginalization” experienced by NY—findings that echo the experiences of NY in Quebec. They also discussed research from Schroeter and James (2015), which found that programs intended to address educational gaps and prepare NY for entry into post-secondary institutions instead exacerbated their experiences of marginalization and exclusion. This aligns with findings from an international study that investigated the indirect effects of NY’s acculturation orientations on school adjustment outcomes in six European countries (Schachner et al., 2017). The researchers found that youth with mainstream acculturation orientations fared worse on school adjustment outcomes than those who had integration acculturation orientations. That is, NY who felt less pressure to assimilate and were encouraged to celebrate their ethnic culture alongside mainstream culture fared better compared to those who did not.

Allen (2006) calls into question the use of the term “integration” and suggests that operationalizing the experiences of NY in this way places the onus on them to adapt to their new school context. Their experience then becomes one of exclusion rather than inclusion where “the changes demanded of the newcomers far outweigh those demanded of the host society” (p. 251). Importantly, quantitative research from Berry et al. (2006) found that discrimination had a strong negative effect on the psychological and sociocultural adjustment of NY. To fully understand the school integration experiences of NY into the francophone school system, Allen (2006) advocates for an approach that positions them as the subjects rather than the objects of integration. This approach would allow us to learn about integration “through the experiences and perspectives of immigrants themselves” (Allen, 2006, p. 252).

1.2 Conducting research with newcomer youth

Going beyond Allen’s (2006) call to position NY as subjects rather than objects in research examining their school integration experiences, other scholars have begun to develop and advocate for methodologies that position NY as fully agentic actors in the research process (Kassan et al., 2020; Matejko et al., 2021). Previous research conducted on, rather than with, NY has yielded some important findings, but the approaches employed did little to address persistent challenges related to recruitment, participant engagement, language barriers, and, crucially, the accurate representation of the lived experiences of NY (Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020; Matejko et al., 2021). Moreover, the positionality of the researcher and/or research team in traditional approaches places them in a position of power, which further exacerbates the challenge of participant engagement (Goopy and Kassan, 2019). Goopy and Kassan (2019) argued that the practice of conducting research on rather than with newcomer participants results an incomplete understanding of their actual lived experiences. Instead, this approach builds knowledge that is “understood either from within the framework of the dominant group or via between-group comparisons” (p. 2), thereby perpetuating power hierarchies and bias toward newcomer communities. Therefore, to construct meaningful knowledge about the school integration experiences of NY, it is essential to engage them as active participants who can influence the research process, ensuring that it accurately reflects their experiences and results in actionable insights.

1.3 Centering social justice in research with newcomer youth

Research exploring the school integration experiences of NY must not only engage them as active participants but also center social justice aims (Matejko et al., 2021). Clearly, NY face significant challenges integrating into the school system. Research shows that exclusion, discrimination, racism, and other forms of marginalization adversely affect their mental health and wellbeing (Patel et al., 2023). These realities necessitate the application of a social justice framework (Stewart, 2014) in research with NY to ensure it is conducted in culturally relevant and responsive ways. As defined by the British Columbia Ministry of Education (2008), social justice is “a philosophy that extends beyond the protection of rights. Social justice advocates for the full participation of all people, as well as for their basic legal, civil and human rights” (p. 12). Applied to research with NY, a social justice framework positions them as experts on their own lived experiences and prioritizes methods that enable them to share critical insights about their needs. Moreover, the goals of social justice research with NY go beyond constructing knowledge of their experiences of exclusion, discrimination, and racism to actively addressing and dismantling the inequities they face. For researchers, this requires reflexive practices that prompt them to examine their own privilege and power in relation to NY research participants (Goopy and Kassan, 2019).

1.4 Applying an arts-based engagement ethnography in research with newcomer youth

Arts-Based Engagement Ethnography (ABEE), developed by Goopy and Kassan (2019) and Kassan et al. (2020), is a promising methodology for researching harder-to-reach communities, such as NY. ABEE has been successfully used in research with newcomer communities by addressing issues commonly encountered with more traditional qualitative methodologies, such as reduced participant engagement, the over-privileging of knowledge from the dominant group, and a lack of cultural sensitivity. For example, ABEE was recently employed to understand the school integration experiences of NY in Alberta (Matejko et al., 2021). Using data generated by and with NY in the form of cultural probes, IQI, and planned group discussions based on topics that arose in the interviews, Matejko et al. (2021) identified several themes that more comprehensively captured the participants’ integration experiences than possible with traditional methodologies These experiences included typical barriers and supports identified in previous research but also revealed additional themes, including limited trust in systems, fluctuating relationship with cultural identity, and resilience through independent learning. The application of ABEE, guided by a social justice lens, uncovered aspects of NY experiences that might have gone otherwise undetected. Additionally, these findings helped identify specific action steps that school administrators, teachers, and counselors could implement immediately to improve NY school integration.

A promising methodology, more research is needed to establish the utility of using ABEE (Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020) with harder-to-reach communities. Using ABEE with a social justice framework (Stewart, 2014) to explore the integration experiences of French-speaking NY can both contribute to the research base and shed light on the understudied integration experiences of this group into the francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province. Moreover, it can help construct actionable knowledge to improve their integration experiences. The current study was guided by two main research questions: (1) How do NY experience a public francophone school? and (2) How do these experiences influence their positive integration into the francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research design

The current study applied an Arts-Based Engagement Ethnography (ABEE; Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020), grounded in a social justice framework (Stewart, 2014), to explore the experiences of NY integrating into the francophone public school system in the predominantly anglophone province of BC. ABEE is an innovative and critical ethnographic research design that elicits rich, multi-layered data in a relatively short time span. Specifically, ABEE functions as a rapid ethnography (Hardwerker, 2001), enabling in-depth data collection in non-invasive ways. It also serves as a critical ethnography (Dutta, 2015), analyzing participant experiences on individual, group, and systemic levels. For more detailed information on ABEE, please refer to Goopy and Kassan (2019). Using creative methods of inquiry has been shown to help NY express abstract concepts (e.g., identity and agency) (Böök and Mykkänen, 2014; Brown et al., 2020), construct meaning around migration experiences, and process losses (Rousseau and Heusch, 2000; Rousseau et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, creative methods involving visual and artistic materials have been shown to empower NY to express themselves and engage in meaningful conversations (Gause and Coholic, 2010; Rojek and Leek, 2019).

2.2 Data collection

The rapid, critical, and arts-based approach of ABEE involves three phases: (1) cultural probes and related IQI, (2) planned group discussions, and (3) follow-up IQI. In the first phase, cultural probes (sketchbook, colorful gel pens and sketch pencils, maps, and an instant camera) are given to participants to help them document aspects of their daily lives (e.g., feelings, interactions, events). These probes capture participants’ everyday experiences and provide researchers with deeper insights into their lives (Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020). The content of the cultural probes become the participants’ artifacts, which are then used to guide individual qualitative interviews (IQIs) aimed at gaining a more detailed understanding of their school integration experiences. In the second phase, participants are brought together for planned group discussions (PGDs), a variant of traditional focus groups (Creswell and Poth, 2018) that are more commonly used in ethnographic research (Kamberelis and Dimitriadis, 2014). PGDs typically involve participants drawn from naturally occurring groups, rather than strangers brought together to discuss a topic (O’Reilly, 2004). To track the progress of participants and gain a deeper understanding of school integration over time, our research team added follow-up individual interviews, resulting in a third phase.

2.3 Participants

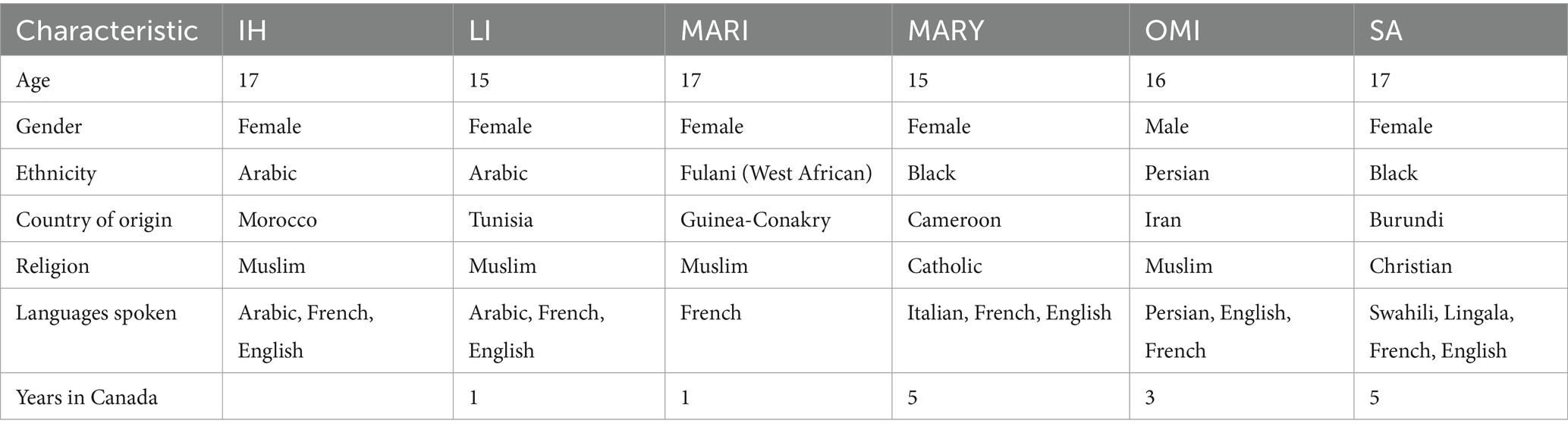

Once ethical approval was obtained from the university and the francophone public school district, [institution blinded for review], participants were recruited through purposive (Douglas, 2022) and snowball sampling (Parker et al., 2019), flyers, and classroom presentations. The inclusion criteria were: (a) being a newcomer (i.e., immigrants, refugees), (b) being currently enrolled in grade 10 or 11 at a public francophone school in BC, and (c) having a minimum proficiency in French to complete IQIs. All participants attended a public francophone school in a large urban centre in BC that serves nearly 500 students in grades 7–12. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants’ demographics.2

2.4 Procedure

Interested individuals were asked to contact the study team and complete a demographic questionnaire. Then, a research team member contacted eligible individuals to arrange a meeting and review the consent form with them. Since the study used “mature minor consent”—which in BC allows minors (under 19 years old) to consent to participate in research without parental approval, provided they demonstrate sufficient maturity and understanding of the study’s risks and benefits—the in-person meeting was essential. This meeting also allowed the researcher to verify that these conditions were met. During this meeting, the researcher also provided the participants (N = 6) with the cultural probe materials (colorful gel pens and sketch pencils, maps, and an instant camera) and reviewed the guidelines for their use. Participants were given 2 weeks to document their daily experiences in any way they chose. At the end of the 2 weeks, the researcher collected the participants’ cultural probes. These were used as artifacts to guide the topics discussed during the semi-structured IQI. The researcher reviewed the artifacts, planned the interviews, and then met with each participant individually for 30–60 min. These interviews, conducted in French and English depending on the participant’s preference, were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

A few months later, the PGD phase of the ABEE procedure began, involving two discussions held 3 months apart. Five of the six original participants chose to participate in the PGDs, each lasting approximately 60 min. Topics were derived from analysis of the participants’ artifacts and IQI; participants were also encouraged to discuss topics relevant and important to them. Discussions were conducted primarily in French, with the option to use English or other languages as needed. Each discussion was audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

After the second PGD, participants were invited to participate in a semi-structured follow-up IQI. Three of the six participants chose to participate. These interviews invited them to reflect on their artifacts and their participation in the study. The follow-up interviews gave them the opportunity to add any additional thoughts about their integration experiences, including advice they might want to offer NY and the school personnel who support them. These interviews, conducted in French and English, lasted between 30 and 60 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

2.5 Ethical considerations

To ensure participants felt comfortable with their involvement in the study, several measures were taken to protect their privacy. For example, parents were not given access to information shared during the IQI. Teachers were also not informed who was participating. However, the settlement support professional, known and trusted by all participants, was aware of who was participating because she provided her office as a meeting space for the PGDs. Participants expressed feelings of trust and affection toward this person, viewing her space as welcoming and safe. Therefore, her awareness of who was participating in the study posed minimal risk to their sense of privacy. Additionally, in preparing this manuscript, we took care to protect participants’ identities by keeping descriptions brief, using pseudonyms, and providing minimal details about the school location.

2.6 Data analysis

Data from participants’ artifacts, individual qualitative interviews, and planned group discussions were analyzed to explore the integration experiences of NY in a public francophone school in the predominantly anglophone province of BC. Data analysis included transcribing all interviews and planned group discussions. During this process, participants’ artifacts (e.g., journal entries, photographs, illustrations) were paired with their interview transcripts, with identifying information removed. Data analysis followed a three-stage process (Creswell and Poth, 2018; Matejko et al., 2021; Saldaña, 2014; Wolcott, 1994): (a) pre-analysis, (b) analysis, and (c) integration. In the pre-analysis stage, participants’ artifacts were analyzed, and preliminary codes were assigned. These codes informed the planning of the initial IQI. The analysis stage involved a series of steps to systematically analyze data from the initial IQI, the two PGDs, and the follow-up interviews. Transcripts from each dataset were read while margin notes and initial codes were recorded. The transcripts were then reread and inspected for patterns and significant themes (structures). From these, meaning units (e.g., sentences) were extracted and recorded. Following, the transcripts were re-examined from a social justice lens. For example, we looked for evidence of equitable opportunities for engagement in the school community and related this to cultural factors that may have influenced participants’ integration experience. A member of the research team with expertise in ABEE subsequently reread all the transcripts to verify the identified structures, patterns, and meaning units. In the third stage, integration, findings were compared across all datasets generated by and with the participants. For example, a cross-case analysis was conducted on the agreed upon structures and patterns to identify evidence of shared and unique integration experiences. These findings were then integrated into a representative account that captured the participants’ school integration experiences.

2.7 Rigor

Research rigor was achieved through several established practices in qualitative research. First, the research team was trained in qualitative research methods in general, and in ABEE specifically. Second, trustworthiness was achieved by adhering to three categories outlined by Williams and Morrow (2009): (a) preserving the integrity of the data, (b) maintaining a balance between subjectivity and reflexivity, and (c) ensuring clear communication of the findings. Preserving data integrity involved addressing dependability and triangulation (Patton, 2002). Dependability was achieved by using a detailed, systematic methodology (Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020), while triangulation was achieved by considering multiple perspectives on school integration through the analysis artifacts, interviews, and PGDs (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). We maintained a balance between subjectivity and reflexivity through peer debriefing and member checks (Patton, 2002). Further, member checks and peer auditing via audit trails (Morrow, 2005) were employed to verify the emerging data and prepare it for dissemination. Finally, clear communication of the findings was achieved by detailing each step of the research process and discussing the study’s implications and limitations (Williams and Morrow, 2009).

2.8 Research team positionality

The research team for this study consisted of three women from diverse cultural backgrounds. The individual and collective positionalities we brought to bear on the research process were shaped by our multiple and intersecting cultural identities and social locations. For example, while all multilingual, two members of the research team spoke French as a first language, and one considered French her second language. Additionally, as scholars in education and psychology, we were at different stages of professional development, bringing varied professional experiences to the study, including roles as a classroom teacher and program developer, a school psychologist, and a tenured professor and researcher. Our team shared an interest in adolescent mental health and wellbeing, with specific interests in education, social justice, and immigration. We critically examined the subjective perspectives each of us brought to the project and discussed how this might influence the results (Finlay, 2014). Also, as described in the section on rigor, we employed several practices to inspect our individual and shared biases throughout the research process.

3 Results

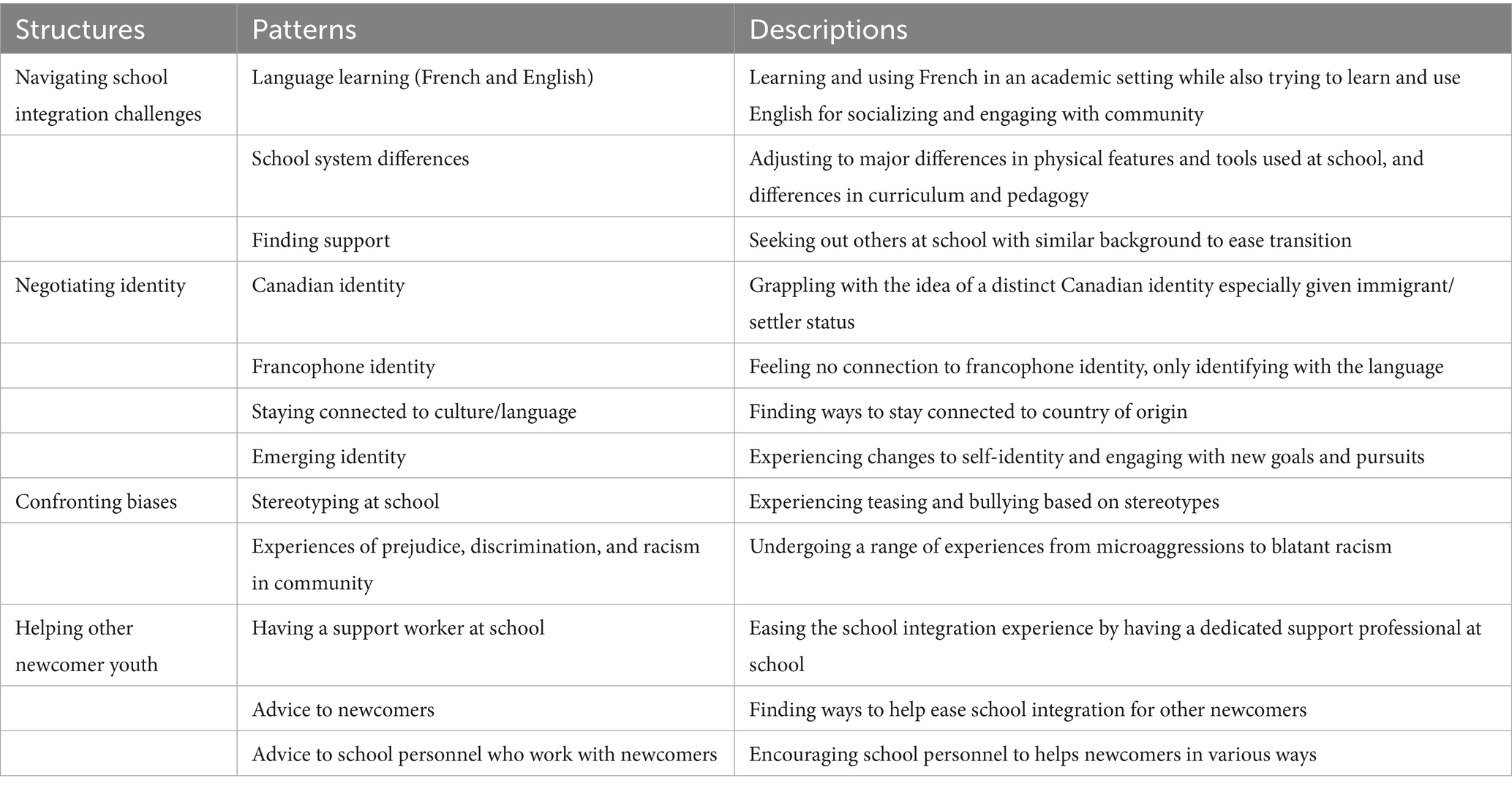

In this study, we applied an Arts-Based Engagement Ethnography (ABEE; Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020) with a social justice lens (Stewart, 2014) to explore the school integration experiences of French-speaking NY in a public francophone school in the predominantly anglophone province of BC. Our research was guided by two main questions: (1) How do NY experience a public francophone school? and (2) How do these experiences influence their positive integration into the francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province? Through systematic analyses of participants’ artifacts, interviews, and PGDs, we identified four structures and related patterns. Structures refer to how participant data were grouped and organized, and patterns capture the similarities evident within each structure (Saldaña, 2014; Wolcott, 1994). The four major structures identified included: (1) navigating school integration challenges, (2) negotiating identity, (3) confronting biases, and (4) helping other NY. Table 2 summarizes the structures, related patterns, and brief descriptions derived from participant data. To enhance the trustworthiness of our findings, direct quotes (translated from French into English where necessary) and excerpts from participants’ artifacts are incorporated into the description of each structure. Pseudonyms identified in Table 1 are used throughout to link participants with their data.

3.1 Navigating school integration challenges

Integrating into a new school context was challenging for all participants. Their experiences ranged from seemingly ordinary things, such as getting used to the unfamiliar physical features of the school building, to the more daunting task of developing language skills in one or more languages. Moreover, participants had to manage these challenges while seeking support from others to navigate cultural differences. Within this structure, three patterns were developed: (a) language learning (French and English), (b) school system differences, and (c) finding support.

3.1.1 Language learning (French and English)

Most of the participants came to the francophone school context with some French-language proficiency and prior experience of schooling in French. For them, using French in academic contexts was not particularly challenging. However, some felt that their learning stalled during the early days of their transition. For example, during the first PGD, MARY shared, “I really became a little bit more behind here because I did not feel so confident and did not understand the language very much.” The main challenge for most of the participants was adjusting to the different accents they encountered and learning the Canadian French vocabulary used in their school and the francophone community in BC. During the IQI, MARY described this phenomenon:

I learned there’s different ways of calling food. For example, people just say you wanna get some “bouffe” later? Another vocabulary word I need to add to my list! I’m like…hmmm…bouffe—what’s bouffe again? And they are like “nourriture.” Yes, of course I want to get some bouffe later! Just funny to see how even in France they speak French, in Belgium they speak French, here they speak French but it’s like different how each community changed words or even made up words.”

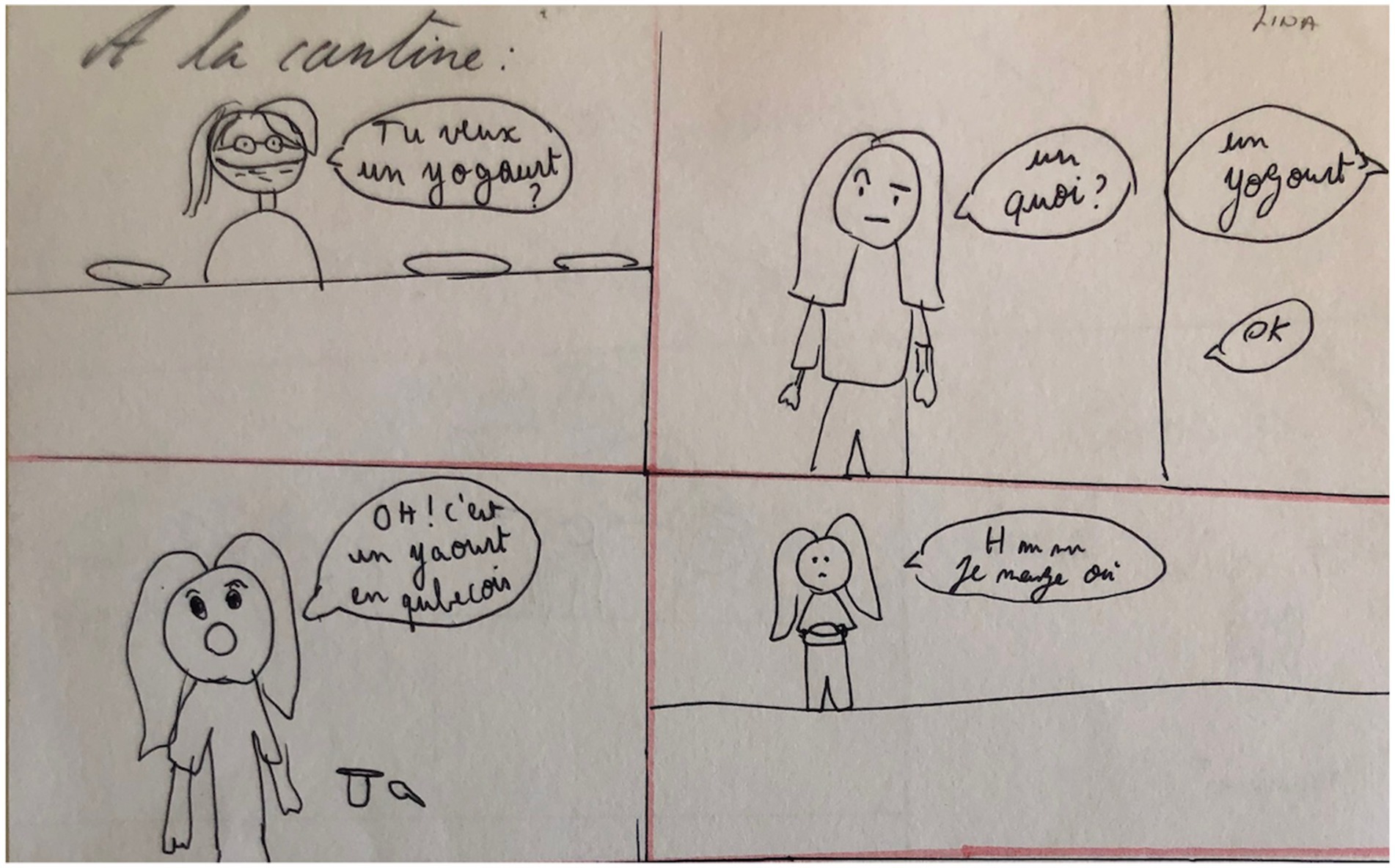

Other participants echoed how the vocabulary differed not only from the French they learned in their home country but also between provinces. A participant from Tunisia, LI, highlighted these differences in a comic strip she produced as part of this study (see Figure 1).

For some participants, both French and English were new languages to learn, both in general and in the context of school, making their integration experiences even more challenging. SA shared this example:

For me it was difficult. Because when I arrived here, I did not know English, French. At the school speaking English, French everyone was like, “Okay, how were you doing at school?’ I do not talk! I think it was like difficult to talk with friends or teachers…and then you get used to it.”

All participants observed that English was often the dominant language used for socializing, leaving those who did not speak it feeling excluded. For example, MARI shared, “For me it’s not okay. I do not know what others are saying.” She explained that making and keeping friends had been challenging due to her lack of English skills. In her initial interview she stated, “What I did not like [was] I did not have friends.” Clearly, language was a significant barrier to making friends and adjusting to the new school context.

All participants reported making progress in their French- and/or English-language skills over time. In her second interview, IH commented on her progress in both French and English with pride:

So, lots of things have changed. My French, like, my French has developed…I understand well. I can speak with my new friends. I can write. I can read books, do comprehension. I used to use Google Translate a lot. Now I use my brain. Now I can just talk. My English has also developed. I can communicate with people at school, in the street.

LI emphasized how the pervasive use of English supplanted her desire to speak French. Indeed, she went from not wanting to speak English to speaking it constantly. She explained:

The thing that’s changed the most from last year…I understood English, but I did not want to speak it. While this year I’m just speaking English 24/7. It’s like…become something I’m used to. So now it’s…more like French that I have to get used to speaking.

Other participants reflected on their multilingualism and acknowledged the varying levels of proficiency across their different languages. In her second interview, MARY reflected:

So, in my work group I’m like “the French girl.” I noticed how I’m, like…sometimes…English just like slips out of my mind. I start looking for words…there’s a slight barrier because everyone else is going to an English school…It’s not really necessary to expose [them] to my vulnerabilities, ‘Ohhh, sorry, English is not my first language.’…That’s when you try to…trust yourself…to be able to let people know “Hey, it’s true that English is not my first language, but we must use what…” I think just being straightforward, being myself, it helped me.

All participants faced challenges navigating the languages required both in and outside of school.

3.1.2 School system differences

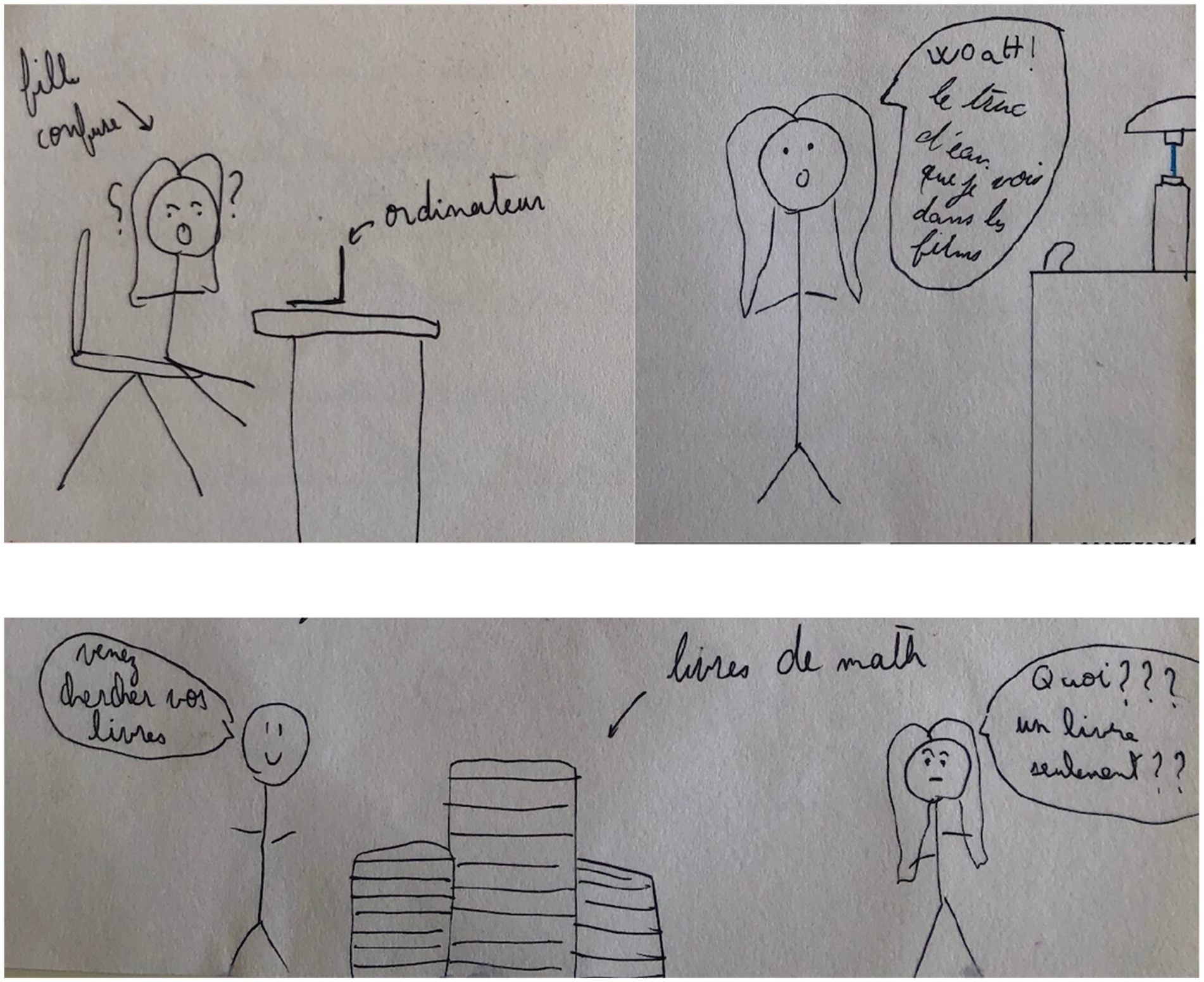

From the unfamiliar physical features of the school building to the materials used to facilitate learning, participants encountered many differences in their new school context compared to their countries of origin. For example, all participants commented on the pervasive use of laptop computers in their learning, noting how this differed significantly from the textbooks, notebooks, and pens they used in their home countries. They also shared that lockers and water bottle filling stations were novel and strange, and that it took some time to get used to. LI created comic frames depicting the novelties that surprised and confused her (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. LI comics showing differences in Canadian schools, such as the prevalence of laptop computers, water bottle filling stations, and the need for only one textbook.

Most participants also agreed that the school system here was easier than in their home countries. For example, SA commented, “It’s really different…when I arrived here the lessons were easier for me. For example, mathematics, because here what we do in fourth year I studied in the first year. I find that here the questions are easier than in Africa.” These sentiments were shared by the other participants and accounted for a large portion of the conversation during both the PGDs and interviews. For example, in the first PGD, LI elicited many nods of agreement when she stated, “It’s much busier there [in her home country]. Already we studied more hours. We had school on Saturdays, there, too [others laughing and agreeing]. The hours were longer. We had more materials…and, like, used more years.”

Getting to and from school also differed between the participants’ home countries and Canada, which they did not appreciate. In their home countries, most of the participants enjoyed short walks to school whereas in Canada, they had long commutes. For example, MARI shared that she enjoyed a 15-min walk to school in her home country, and that she could run home if she forgot a book. Similarly, LI reported that her walk was a mere 10 min, and that she preferred it to the “bus super full with a lot of kinds of students” that she uses to commute in Canada.

Participants also noted the different instructional modes in their new school. In contrast to the traditional textbook-based learning and memorization of their home countries, in Canada they encountered project-based learning and the use of laptop computers with applications that encouraged creativity. In her first interview, MARY described this contrast:

There is a style of teaching or even the curriculum [in my home country]…like…very old, very accurate, notebook, memorize, present…We were tested orally and then graded us until we were angry…but here [in Canada] we came, we had our computers, we did PowerPoint presentations. It was just more creative.

MARI also reflected on the contrast between her home country and Canada in her first interview: “Here we do everything with the computer. So, I’m looking for everything and everything. But in Guinea it’s [in] notebooks. You write. Every day you write.” Adjusting to new pedagogical approaches in Canadian schools was also a popular topic during discussions. For example, SA noted, “Like she said, computers [were different] too. I was like…yeah…So I never tried that. What do I have to do?” Overall, while the participants found the Canadian curriculum easier, they were generally pleased with the pedagogical approach and use of laptop computers.

3.1.3 Finding support

Amid all the differences they had to navigate, participants related how they sought support from others at school who were like them. Shared language and cultural backgrounds or simply having the status of “newcomer” in common connected participants with a network of peers they could lean on during the integration process. During the first PGD, LI reflected on her delight in finding someone who could also speak Arabic: “I love when you find someone for example when I found out that [IH] is from Morocco and we both spoke Arabic…like so happy because at least I can like…to practice my language.”

Participants also found support from teachers and other school personnel. For example, during the first PGD, SA noted how teachers supported her language learning differed from that in her home country: “[W]hen I arrived here I had, like, many teachers who came to help me learn French, English. So, it was, like, very different things. In my country if you do not know, you do not know. That’s the end of your problem.” Participants also found immense support from the settlement support professional embedded at their school. LI commented on the wide-ranging support offered: “When I came here, it was Madame A. who welcomed me…She helped me and my whole family a lot. She gave resources to my parents [to] find work…the doctors and everything…Like the whole family.” MARY agreed, sharing that this person helped her on her first day of school and directed her to a cultural centre where she could meet people of African descent. The support participants found, whether from others like them or from school personnel, was indispensable in helping them navigate the challenges of school integration.

3.2 Negotiating identity

This structure focuses on the myriad factors related to participants’ identities, which evolved in response to their school integration experience and migration to Canada. Identity development is one of the main tasks of adolescence. That the participants were negotiating typical identity development amid the identity changes prompted by their move to Canada speaks to the complexity found in the patterns we identified. The challenge of negotiating these multiple and intersecting identities was discussed across all interviews and PGDs, and participant artifacts. Participants overwhelmingly dismissed the notion of a “Canadian” identity and struggled with the notion of a “francophone” identity. They all sought to stay connected to the cultural identity of their home country through various means, which contributed to the emergence of an entirely new identity. Consequently, we identified four patterns in this structure: (a) Canadian identity, (b) francophone identity, (c) staying connected to culture/language, and (d) emerging identity.

3.2.1 Canadian identity

During the first PGD, participants discussed the cultural differences they experienced in their new Canadian context. These included differences in friendliness and norms around greeting others. For example, LI shared how in her home country it was customary to greet others even if you do not know them, whereas in Canada, she found that people simply behave like “robots,” not taking the time to greet others. She said, “Everyone, like they walk, they go to work, they come home. It’s just routine.” SA agreed and emphasized that, in her culture, greeting others, even strangers, demonstrates respect. Beyond adapting to new cultural norms in Canada, participants also had to adjust to a new context characterized by multiculturalism. In their initial interviews, several participants shared their surprise at the cultural and ethnic diversity of their new country. SA reflected on this difference, saying, “In Burundi, it’s more like African cultures only, but here it’s more like African, Asian, several. It was really something that I found quite interesting because it was like, ok…there are …different types of cultures.” OM related the experience of being in very diverse “Welcome” classes in Montreal, where he first lived after arriving in Canada:

There are Iranians, there are Chinese…there are from all kinds of countries…Mexicans…Even in Montreal, too, it was a lot because I was in the classes for newcomers who are going to learn French…the welcome classes [and] there were from all the countries…all the new cultures.

Alongside the adjustment to Canada’s multicultural context, participants grappled with the country’s colonial history and the experiences of its Indigenous peoples. This in concert with living in a more diverse community contributed to personal growth. MARY discussed this change:

I was pleased in a good way learning about for example the Indigenous community. I just feel like I was more exposed, I do not know, being here just like kinda open my eyes to the outside world, I guess. Being exposed to all those different communities and stuff. I feel like speaking of ethnicities or different communities there’s always work…there’s always time to improve on, there’s always place…to be more aware or accepting “cause, like, I feel like everywhere we go there are always going to be comments like even if you do not belong to that community.”

However, becoming aware of how Canada treated its Indigenous peoples led participants to reject the notion of a Canadian identity. Indeed, during the second PGD, when asked “Are you Canadian?” the participants responded in unison, “Nooo! No one is Canadian, no!” MARY explained that you should not be considered Canadian “unless you are Aboriginal or Indigenous Canadian…for several centuries.” The conversation continued with differing perspectives on the nuances of adopting a Canadian identity. LI intimated that she felt embarrassed for individuals who claimed to be Canadian:

There are also people who are…born here but they say, like, “Oh, me, I’m Canadian but my two parents are African” or something like that. And that, honestly, I’m like embarrassed for those people. Why do you have to be embarrassed about where you are from? You say, like, you are Canadian when you are something else. So, if you take a DNA test, you are not going to be Canadian.

MARY, born in Italy to parents from Cameroon, offered a different perspective that highlighted the complexities of cultural and national identity for NY:

It depends. So, when I told you that I am Italian, but my two parents are from Cameroon…it’s because “that’s all I knew” you know? But growing up you have to learn to say that my nationality is Canadian but that [my] cultural origin, as you say, is African.

3.2.2 Francophone identity

Similar to the question of a Canadian identity, the idea of being “French” or “francophone” did not resonate with the participants. Although they recognized that speaking French was part of their identity, this aspect was becoming less prominent in the anglophone context. For example, during the second PGD, LI observed:

I do not find being French-speaking as important as someone else. I speak French, that’s all. Not like francophone culture and all that. It’s like I do not identify with that. It’s just I speak French because of colonization or whatever…I’m not, like, proud to be French-speaking. I do not mind speaking another language, but I do not think it’s necessary. In Canada, I do not use the French identity. Just at school. If someone meets me in the city or something else like that, I’m Arab and I just want to speak English. So French is just non-existent for me, like, outside of school.

Participants acknowledged the value of their French-language skills for future employment, seeing it as a useful addition to their CV. However, they did not consider French or French culture to be an important part of their lives going forward. LI commented, “I know that in my future I will not use it. I could just probably, like, put it on my CV that I speak three languages…I think that apart from, like, visiting French-speaking countries, it’s not an asset.”

Contemplating the idea of a francophone identity highlighted the complexity in how participants perceived the myriad ways they could identify. From the type of French spoken by themselves and their families to the various countries they have lived in, participants found it challenging to identify in a singular way. MARY described this phenomenon:

When I speak French, they say, “Oh, you have a European accent.” But I’m just like, “We’re associated with French.” Like, my mother lived in Belgium, so she was associated with Belgian [French]. “So, you are associated with this country, but where are you really from?” they ask you. “How is it you are associated with this country? Where do you come from?” For some people, it’s complicated…it depends on your background. For my parents, it’s easy…both Cameroon, 100 percent.

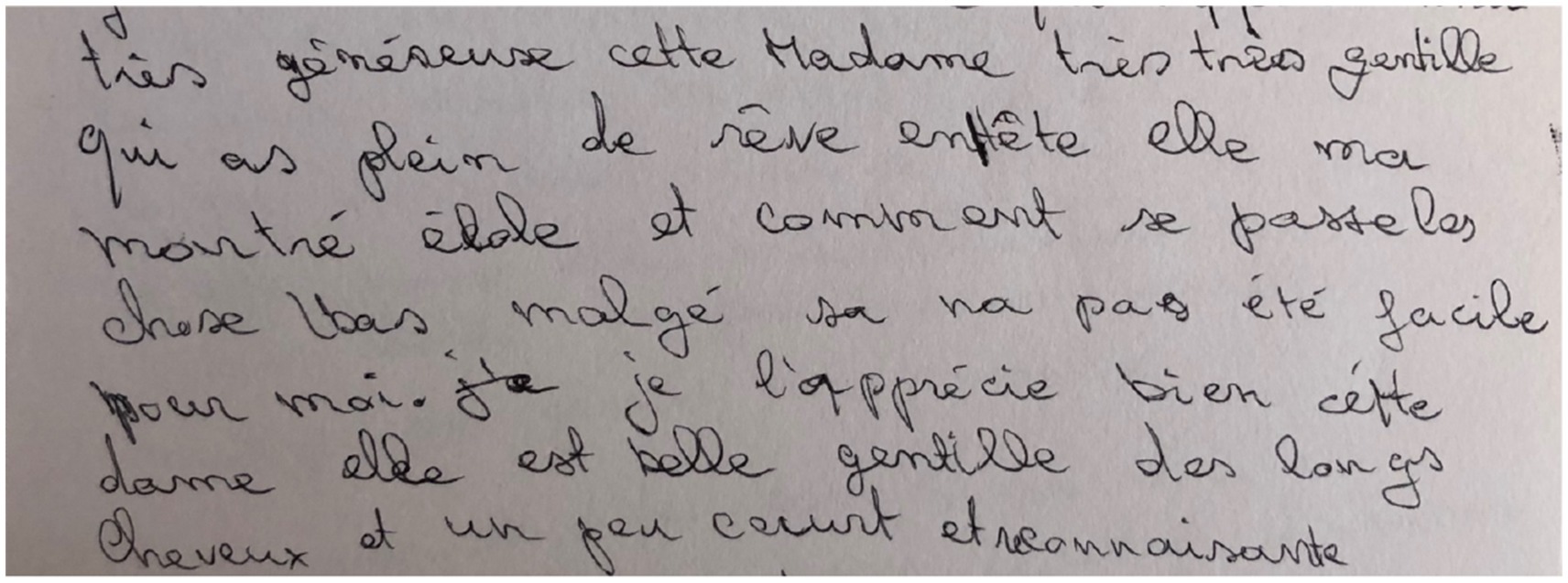

MARY expanded on the complexities of language and background in the writing she submitted as part of this study (see Figure 3). Although she spent her first 10 years in Italy, she explained how she had been exposed to French her whole life—through her Cameroonian parents, where French is the official language, and the family’s time spent in France and Belgium—contributing to her complex cultural background.

Figure 3. MARY’s description of her complex background and experience with different kinds of French.

SA shared her thoughts on her mixed background, saying, “Me, honestly, I do not know…my identity. My mother is 50 % Burundian, 50 % Tanzanian. My father is 50 % something and 50 % Somalian. So…yeah…” For others, however, it was more straightforward. LI expressed, “It’s very easy for me. I am just Tunisian. I am happy not to be mixed because it’s very easy for me.”

3.2.3 Staying connected to culture/language

Participants did not identify with a Canadian or francophone identity despite living in Canada and attending a francophone school. While some participants struggled with how to identify due the complexities inherent in their own and their family’s backgrounds, all participants expressed a desire to stay connected to the language and culture with which they most strongly identified. In the first PGD, LI described how she stayed connected, saying, “I try to find, like, any opportunity to refresh my memory. I watch, like, series…old…and everything. I like listening to music.” Despite their efforts, participants found it challenging to stay connected and felt their language skills fading. LI commented, “When I hear someone say a word I have not heard in a long time [and] I totally forgot that word…No, I’m, like, I’m fucked. I forgot my culture. I forgot everything!” Regarding the school’s efforts to celebrate the diversity of the student body in the form of a cultural parade, participants had mixed feelings. SA expressed that she and others like her chose not to participate due to the sadness associated with growing distant from their culture, explaining, “Like it’s been said, the time zones are very different. I do not find many opportunities to talk with my friends, my family [back home]. I found several people who were happy, even though it stung, why they never did the culture parades.” Seeing aspects of their culture, however well-intentioned, served as reminders of what participants missed most.

3.2.4 Emerging identity

Our discussions about Canadian and francophone identity, as well as the other complex ways in which the participants identified, revealed the emergence of a new identity taking shape within the Canadian context. Participants were developing an anglo-centric identity aligned with their environment. They spoke about becoming more aware of aspects of their identity that had been masked or less important in their home countries. Further, as they gained confidence and felt more at ease in their new environment, participants reported trying new things that were contributing to the expansion of their identity.

In both her interviews, MARY spoke at length about the changes she was experiencing. She described a growing self-awareness, particularly regarding her Blackness and its implications in Canada. She noted a difference between being Black in Europe, where she was born, and being Black in Canada and the United States. This emerging identity led her to join antiracism groups and explore the history of enslavement. She found herself moved to tears on numerous occasions, but also felt hopeful about being able to make a difference. In the first interview, she said, “I know not everything is going to change in a few days but at least I can have my input…that’s why I joined the antiracism group and also when I heard about this [study]…it’s really cool.” MARY continued her self-reflection in the second interview:

When I was younger, I did not care, but in growing up, like, there is really more…with the Black Lives Matter movement…It’s good that it really touched me and…just affected me, like pushed to do like research and just talk about it with my mom or talk with family friends about this…because before it wasn’t talked about, it wasn’t a conversation.

Other participants experienced growth and change in their identities and capacity to try new things. In her first interview, IH shared that she was scared to speak French and very nervous about making new friends. However, in her follow-up interview, she described how she had widened her circle of friends and tried new things, such as cooking. Similarly, LI reported finding a new friend group and trying new activities. MARY attributed changes in herself to the opportunities she had to expand her circle beyond the school context:

But I find that what changed…the fact that I was exposed to a lot more people. Because here [at school] it was just focused like on the people at my school. But right now, like, I also think it’s important to adapt to the city where we live and to things we do outside of school.

Overall, participants were beginning to feel more at ease in their new context, which led them to pursue new activities that expanded their social networks beyond the francophone school community.

3.3 Confronting biases

This structure was created from participants’ accounts of encountering a wide range of biases during their integration into the school and community. These experiences ranged from subtle acts, such as stereotyping and microaggressions, to overt discrimination and racism. Participants discussed their efforts to navigate and process these biases in all interviews and PGDs, and in their artifacts. Their accounts revealed that they experienced biases from multiple sources, including peers, teachers, “helpers” at school, and individuals in the community. At school, these experiences included teasing and bullying related to their newcomer status, cultural background, or religious identity. In the broader community, instances of discrimination and racism were also rooted in their cultural or religious identity and skin color. A distressing feature of their integration experiences, this structure includes the following two patterns: (a) stereotyping at school and (b) experiences of prejudice, discrimination, and racism in the community.

3.3.1 Stereotyping at school

In both the interviews and PDGs, participants provided detailed accounts of teasing and bullying at school related to aspects of their identity, such as their cultural or religious background. Initially, these experiences were no more than an annoyance, but over time, their impact intensified, leading to tears and causing real harm. LI described the teasing and bullying that she experienced and its mounting impact:

It’s especially the students in my class who say…like jokes…I hear them say Allah and…words Arabs, like, mean something very simple. I do not understand why they say it over and over. It annoys me so much…and they say it to annoy me…At the end of the year they made a parade of culture…and…someone shouted “Allah Akbar” it’s like a very normal sentence when we use if every day like Muslims to pray…now it’s like something racist like when you say that it’s like…if you said you are a terrorist…and like that annoys me…it makes me want to cry…It’s just how it happens and I do not know why.

In the second PGD, LI explained more about the teasing and bullying she experienced at school, emphasizing that it often comes from “white boys:”

White boys in our class just say words in Arabic for no reason. It’s, like, interesting, just why? They do not even know what that means. There are still people who, especially boys, make jokes about terrorists and everything and bombs and everything and it’s just irritating. I know they do not do it for, like, because I’m there. They still do it for no reason.

In the same discussion, MARY shared her experience of being stereotyped as a refugee based on her black skin and African origin. Like LI, she found these interactions tiresome and frustrating. She expressed, “This is frustrating. Like, because when he says that [you are a refugee] he already classifies you as [a] horror.”

Although upsetting, participants explained that they used humor to deal with the teasing and bullying. SA shared an example: “I find sometimes as a joke I see a person, several, like “Do you have a dad?” “Yah, how was I born?” Oh, yah, that’s a lot of Black people, they do not have fathers. Okay [laughing].” Similarly, LI described her response to the stereotype that Arabs live in the desert and ride camels:

I do the same thing…“I go to school on a camel every day!” They are “WOW!” Like I use a camel every day and I was on the sand and everything. That’s also another stereotype…there’s another a lot of people think that we just have desert…while it’s more like cities like here…another thing that Africans are black and all that is…like North Africa exists!

In addition to being teased and bullied by their peers based on stereotypes, participants also experienced stereotyping by their teachers. Several participants recounted instances where they were offered help when it was not needed or when teachers mistook their developing competence in French or English with a lack of ability in a subject area. MARY explained:

I notice [teaching assistants] kind of park it with newcomers, the ethnic minority students, and it’s a bit, like, it’s embarrassing for people who really need help like those who do not speak English. Because I did not speak English…and it’s in French, too, so I did not need help but then they’ll come and sit next to you. Like, they are not going to say that because you are new but…sometimes your skin color influences their judgment. Like, there is someone like me with dark skin, they will target you, like, “Are you okay? Do you need help? You know, if it’s too complicated we can go to a nearby room” and all that.

Participants noted that some teachers made efforts to make the curriculum more culturally relevant and inclusive, but their efforts lacked authenticity. Describing the use of diverse literary texts, MARY commented:

Very often these works are, like, very well-known works. You know, like they did not really take the time and effort to really look for diverse books. And they are just doing it to appease their conscience. And the students notice it, the students notice that it does not come from them. They notice…we do not feel necessarily included in the classroom.

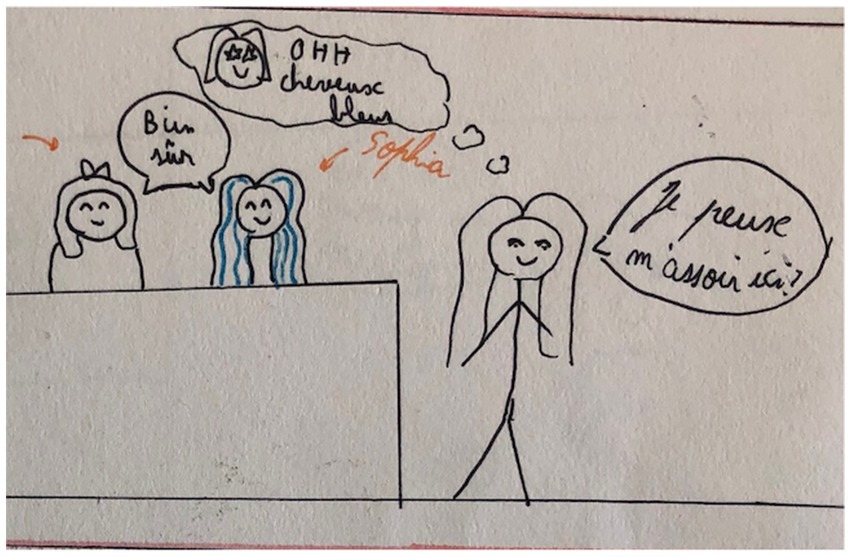

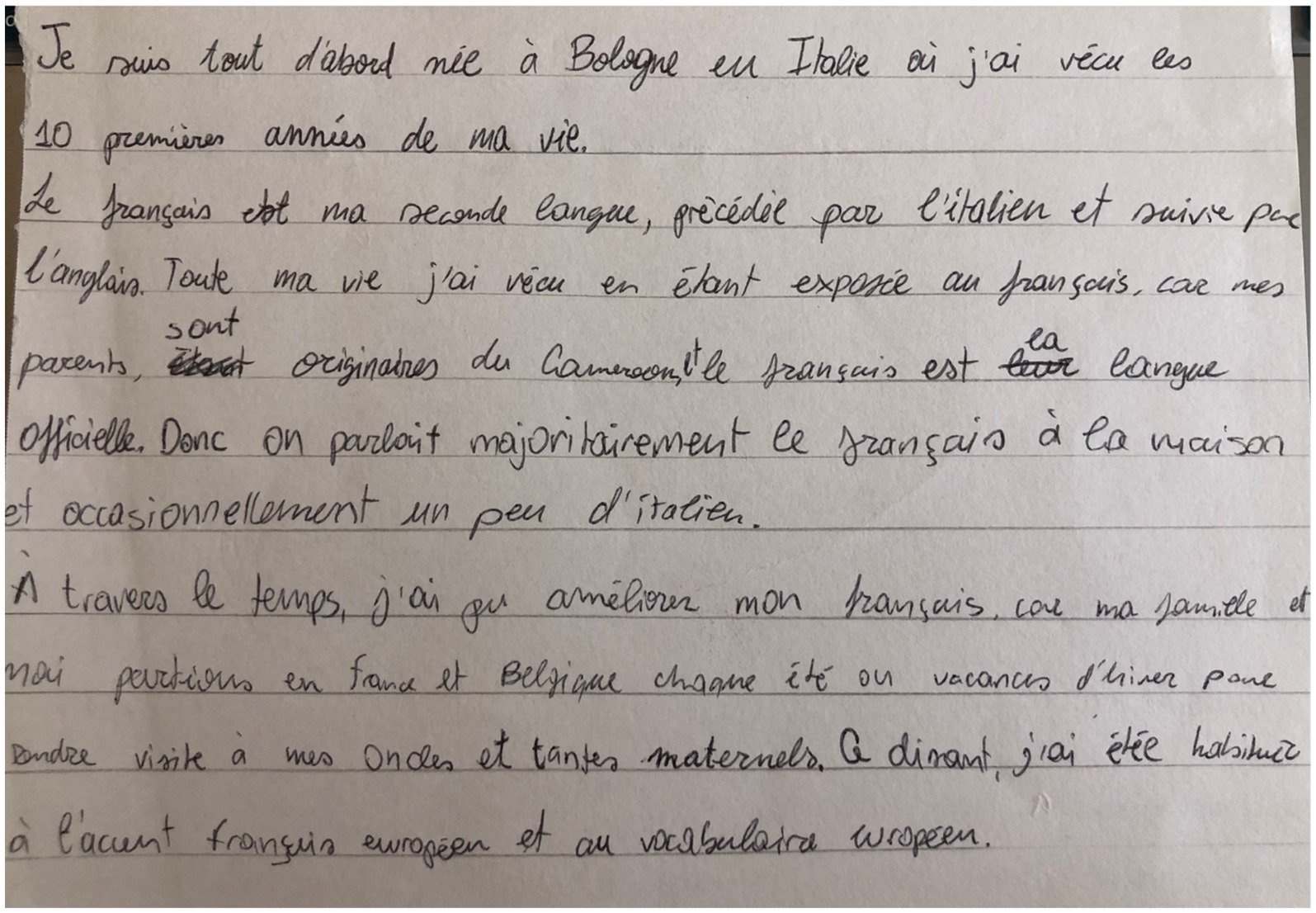

Several participants also shared the stereotypes they held about Canada and its people. For example, LI depicted the stereotypical image of a blonde-haired Canadian student in one of her comics (see Figure 4).

In her first interview, she explained that this stereotype came from popular media, saying, “When I came, it was just…in my brain…it’s like, Canada, it’s just Canadians like Americans in the films that we see.” For LI, the typical American portrayed in films had blonde hair and blue eyes. Other participants shared their perceptions of Canadians, shaped by various media sources. For example, MARY described the images of Canada she had seen before moving to the country:

I do not know what messed up site we went to…all I remember there were images of Indians—they called Indians, but the Natives—and I realized that it was not even the Canadian Natives, it was the American Natives that they show in the cowboy movies or whatever. So that was it and I remember that there was forest everywhere and some beavers…and then I think somewhere there was maple syrup…but those were the images that struck me.

Although participants held stereotypical beliefs about Canada and its people, their experiences quickly replaced these with more informed perceptions and an awareness of the new society they now inhabited. However, the stereotypes others held of them were ever-present, forcing them to confront these biases, which marked a painful part of the overall integration process.

3.3.2 Experiences of prejudice, discrimination, and racism in the community

Upon arriving in Canada, participants quickly discovered that it is a diverse country, perhaps even more so than their own. They also learned that despite this ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity, racism and racists still exist. LI summed it up eloquently: “Racism still exists in Canada. They say that it does not, that there’s no racism…it’s the people who do not receive racism who say that there is no racism.”

Participants and their families experienced prejudice, discrimination, and racism in various community settings. SA, for example, described the experience her mother had while shopping:

So, she goes to a store to buy—I forget what it was—and then the gentleman who was there, he was like “Are you sure you can afford this? I do not think we have anything for the cheap ones.” My mother was like, “I’m not looking for the cheap price. I see what I’m looking for.” “Are you sure you have enough dollars” “Did you just ask me how many dollars?!” Yeah…[shrugs and rolls eyes].

Participants commented that people in the community perceived them as lacking money or being uneducated. Or worse, that people were afraid of them, and this fear was often communicated through microaggressions. For example, MARY related a story of her father’s experience with microaggressions:

Like my father…he is like…the stereotype of a black man…which people are afraid…he is very tall, and he plays a lot of sports so he is muscular. So, he’s the typical person that when he walks women clutch their bags…also he’s like really serious. But you’ll never know that he’s really nice and so usually people are just afraid of him.

Although participants smiled and laughed while recounting their parents’ experiences, there was an underlying sadness and frustration that they and their families had to endure these experiences daily. For example, LI shared her mother’s experience as a woman who wears a hijab, expressing a mix of exasperation and sadness:

It’s like the same with my mother…my mother wears the hijab and, like, in the stores something like that, there is, like, a woman who is in front of us in line. She is holding, like, this…the things she bought, so tight, and my mom was behind her. “Can you give me space,” she said. I see, like, their looks because I can, like…I’m not too Arab for some people, but for my mother when you see her you know that she is Arab, she is Muslim. So, they are still afraid more than usual. If it was, like, a white person they would have been, like, normal. But since, like, they have Arab looks, they are just afraid.

During the second PGD, when asked whether they regularly experienced microaggressions and racism, all the participants responded affirmatively, saying, “Oh, yes. A lot.” MARY added, “Here in Canada they are polite. They’re not going to say something to your face, but there are a lot of microaggressions.” These microaggressions can also manifest as impatience with language ability, as LI described regarding her mother’s experience:

It’s like they are, they get angry very easily because they do not want to repeat their…for example, my mother, she understands but, like, when they speak quickly, she does not really understand English. She tells them, “Please, I’m trying to learn English. Can you repeat?” and the woman is just, she gets angry…Just take a breath! It’s not the end of the world if you repeat your words!

Confronting biases through stereotyping, teasing, and bullying at school, along with prejudice, discrimination, and racism in the community featured prominently in participants’ integration experiences—over and above the challenges of navigating differences between the Canadian context and their home countries.

3.4 Helping other newcomer youth

The NY in this study were eager to discuss what helped ease their school integration and offered advice based on their experiences for other NY and the school personnel who support them. All participants agreed that having a dedicated support professional embedded at their school made a significant and positive impact on their integration experiences. They also emphasized that seeking support is crucial for successfully managing the integration process, along with being patient and giving oneself grace. Additionally, they stressed that school personnel should provide the time and space needed for them to adjust to a new environment. The fourth structure encompasses participants’ reflections on what helped them integrate into the school system and host country, and the advice they would give other NY and the school personnel who support them. Specifically, this structure includes the following three patterns: (a) having a support worker at school, (b) advice to newcomers, and (c) advice to school personnel who work with newcomers.

3.4.1 Having a support worker at school

Participants were eager to share what facilitated their school integration and reflect on which aspects of their own support should be included in support for other newcomers. All participants agreed that school personnel, specifically the settlement support professional embedded at their school, made a different in their integration experiences. SA reflected on the impact of this person’s work: “I love her trying to help newcomers because I find that a lot of newcomers think they are alone and also like they cannot…but they make them feel like it’s like ‘belong.’” IH expressed a similar sentiment and described specific ways the settlement support professional helped her:

I like her work because she help people. Like, she help me very much. Like, I thought that it’s gonna be hard for me because it’s my first time I talk French, like French all the day. I want to say…thank you “cause she help me and I like the way she talked and she helped the others.”

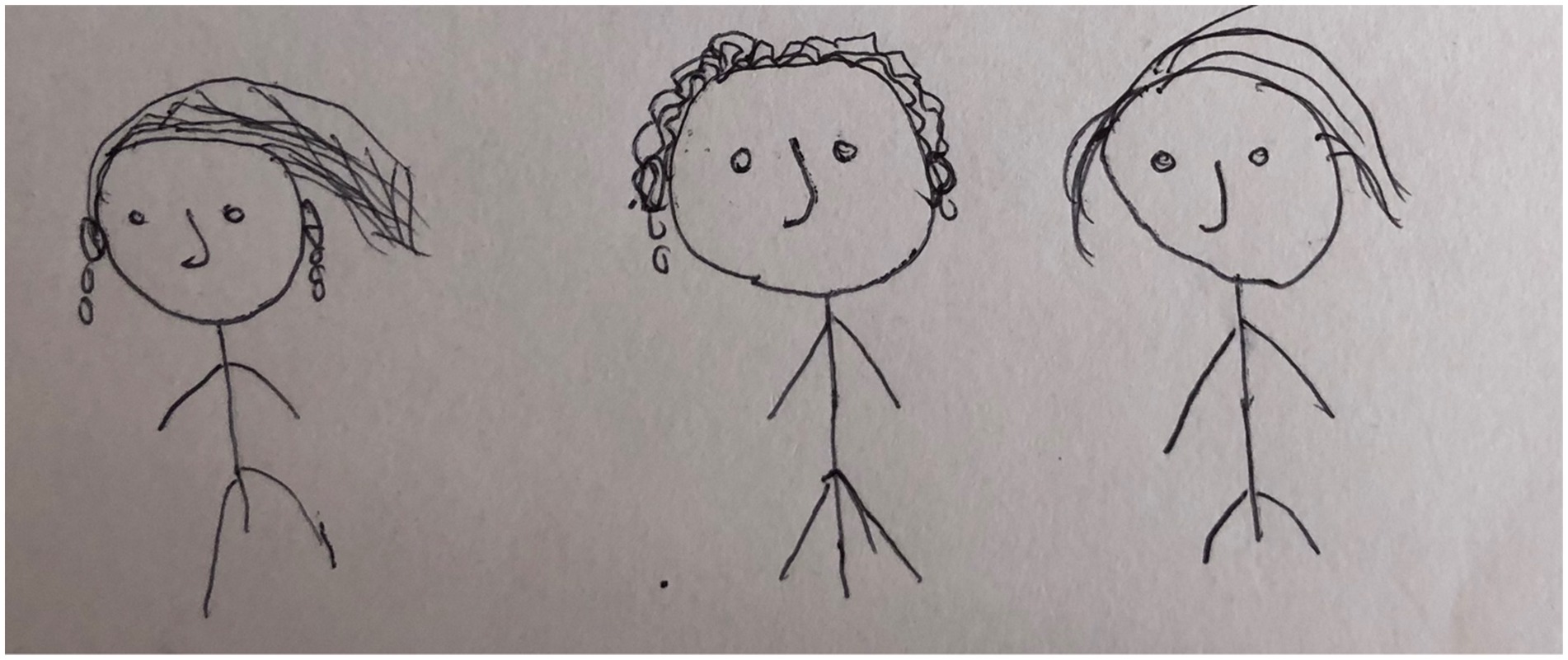

The participants’ gratitude and appreciation for this settlement support professional were evident in their journals and drawings. For example, MARI wrote a beautiful passage thanking this person for helping her through some difficult times (see Figure 5). She also included an illustration of this person alongside a close friend (see Figure 6), both of whom she described as key in helping her navigate the school integration process which was very difficult for her.

The consequential work of this settlement support professional extended beyond helping the participants at school to helping their families. LI reflected on how this person helped her entire family:

[She] welcomed me, everything was good…She helped me and my whole family a lot. She gave resources to my parents so that we can find work…the doctors and everything …she helped us a lot. Like the whole family, my brother…he graduated last year…gave us a lot of help in the summer.

Clearly, this settlement support professional excelled in her role, offering invaluable support and guidance not only to the participants but also to their families throughout the integration process at school and within the wider community. Having a staff member dedicated to supporting NY and their families proved to be an important factor in facilitating the participants’ school integration.

3.4.2 Advice to newcomers

Participants eagerly reflected on their own integration experiences and translated them into an abundance of advice for other NY. For example, several participants emphasized the importance of taking things day by day and being patient with the process. IH connected this to advice on perseverance:

I would say, day by day, you’ll get used to it…get used to speaking in French, in English. They should not give up if they want to learn French. They have to keep learning. It does not matter if they do not, like, write words in the correct way or speak it, like…they will happen… Like they do not worry because they…we find someone to help them and with time you gonna learn a lot of things, like…like me! I learn some words in French and I like that because now I talk three language!

Others underscored the importance of leaning on friends and seeking support from others whenever needed. LI advised:

Really try to find, like, all the possible resources. Like asking for help if… you do not understand something…just ask the teacher, ask the advisor, and everything…so there are still resources to help just, like …do not try to understand and all that. If you cannot, just ask for help!

Similarly, IH advised:

Do not panic and do not try to, like…just talk with everyone at the same time…let them find out about you…if you do not understand something, ask. Do not wait for people, do not hesitate. “When I’m going to ask?…Tomorrow?”…Tomorrow you do not understand something else!

Beyond trusting the process and seeking help, participants also recommended staying true to yourself and showing yourself compassion and grace. MARY advised, “It’s a message that we hear everywhere, but it’s really true! Just to be yourself, to be your person. Also, the fact that you are in a new environment helps. You can rediscover yourself, find yourself in new aspects.” In this statement, MARY extends the idea of being authentic to the promise and possibility of discovering and rediscovering yourself as a benefit of the integration process. She explained that she arrived at this advice through her own journey of trying to fit in, ultimately discovering who she truly was in Canada:

So, when you arrive you will discover new qualities, so it is important that you “self-love.” It’s important that you do not try to change yourself for groups…There were groups of girls that I found so cool…ahhh…I want to become! It’s good for, like, the first weeks. After, like, there are moments when you realize that it’s not my role and therefore it is desperate to create a new identity for yourself. Because who you are in Canada, it is really important to form your identity to be able to grow which I think I have understood.

Other participants encouraged newcomers to focus on the privilege of being in Canada, and to make the most of it by dedicating themselves to their studies and avoiding negative influences. MARI advised:

The advice that I am going to give to newcomers to Canada: They have a good chance of coming to Canada!… so the advice that I am going to give them is just have to take the serious studies, do not follow bad friends, [and] respect others.”

Finally, MARY’s advice to NY was to leverage their differences to connect with others and integrate into the school community:

I know it’s corny. Everybody says that, but it’s true. I would surely say just be yourself…not afraid of being culturally different…not afraid of what people will think. Because what happened is, it’s a good thing people are really fascinated if I come from somewhere else. So, I find to use your culture, wherever you come from, as an advantage, even as a conversation starter!

Drawing on their experiences of school integration and migration, the participants were able to offer advice to help other NY navigate their own integration process.

3.4.3 Advice to school personnel who work with newcomers

Participants were also eager to discuss the advice they would give school personnel on how to better support NY. They translated some of their negative experiences into recommendations on what to do and what not to do. IH stated succinctly: “Give them time to express what they want to say and help them.” This advice came from her own experiences of feeling rushed, overwhelmed, and generally lost during her first few months at school. These feelings were further intensified by the challenge of simultaneously learning French and English, having migrated from a country where she only spoke Arabic. Her advice underscores the need for NY to feel both supported and empowered with autonomy and agency. MARY echoed this sentiment, stressing the importance of asking newcomers if they want help rather than assuming they need it, as this assumption could be offensive, “I would just say that maybe it’s the piece that wants to help someone. Maybe he asks him with what you need help with…‘I’m here to help you. Do you need help?’”

Other participants shared what they would have appreciated as part of their integration experience. For example, LI mentioned that she would have appreciated a tour of the school to meet people and become familiar with her surroundings:

If I still had to change something…have someone who would, like, take me on a tour of the school first day, like bring me to all my classes, introduce to his friends. Or something like that to make it easier. Because…it was horrible…because I just had to follow a girl that I did not know because she helped me find my classes and everything. So, it would be good if you even had a teacher or someone like that. So that on the first day you are really integrated…It would be nice to have, like, someone who’s just going to show everything!

IH expressed that the integration process would have been easier if she had more people with whom she could speak her first language: “I wish, like, there’s people talk more Arabic…it’s too hard to use computer…like, because when I want to translate something, I used to [use] some keyboard [for] Arabic.”

Reflecting on their own integration experiences and the advice they would give to other NY and the adults who support them helped participants gain deeper insights into their own journeys. For example, SA reflected:

I appreciate that…I find more things…and people to talk about my experience…I saw several other people who had just arrived in Canada. It was like, okay, it’s not really just me…because at school I thought it was just me.”

Similarly, MARY reflected:

This experience, honestly, like at the end of the day, “La vie, c’est. la vie.” There’s always gonna be stuff that’ll make you reflect and there’s also gonna be stuff, like, damn, that I’m lucky, I’m glad to be here. There will always be good experiences you’ll have with your family and your friends. So, after all, I do not regret being here.

Despite the challenges and hardships of migrating to Canada and integrating into the francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province, participants expressed appreciation for the life they were building in Canada and optimism about their futures.

4 Discussion

Employing an Arts-Based Engagement Ethnography (ABEE; Goopy and Kassan, 2019; Kassan et al., 2020) with a social justice lens (Stewart, 2014), the current study invited French-speaking newcomer youth to explore their experiences of integrating into the public francophone school system in the predominantly anglophone province of BC. Data were collected through the participants’ artifacts, individual qualitative interviews, and planned group discussions. Systematic analyses of the data generated four distinct structures, each featuring several patterns of similarity across participants. They included: (1) navigating school integration challenges: language learning (French and English), school system differences, and finding support; (2) negotiating identity: Canadian identity, francophone identity, staying connected to culture/language, and emerging identity; (3) confronting biases: stereotyping at school and experiences of prejudice, discrimination, and racism in the community; and (4) helping other newcomer youth: having a support worker at school, advice to newcomers, and advice to school personnel who support newcomers.

The structures and patterns that emerged from the data align with previous research exploring the integration experiences of newcomers in other contexts, including in Canada. However, our findings suggest that integrating into a francophone school in a predominantly anglophone province presents additional challenges for NY that remain underexplored or inadequately addressed. Furthermore, issues of bias and racism appear to undermine the efforts of NY to integrate, highlighting the need for additional supports in this area. Thus, our findings not only corroborate existing research on NY integration but also offer a new and needed perspective with significant implications for social justice. We discuss these connections to prior research, present additional important findings, and suggest actions to improve the integration experiences of NY into a francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone community.

4.1 Navigating school differences

Participants in this study were invited to explore their experiences and perspectives on integrating into a public francophone school system in a predominantly anglophone province. The stories they shared reflected elements typical of integration experiences documented in the existing literature (e.g., Bennimas et al., 2017; Kaufmann, 2021). For example, the participants expressed surprise and confusion regarding the unfamiliar physical features of their school building (e.g., water bottle filling stations) and the tools used for learning (e.g., laptop computers). They also noted differences in pedagogy, curriculum, and teaching styles between the Canadian context and their countries of origin. Participants found themselves having to adjust to the project-based learning approach and the lower level of curriculum difficulty in their new school.

Overall, participants’ experiences of navigating school differences were mostly favorable. Similarly, Brown (2014) found that French-speaking NY positively appraised the easier curriculum, learning resources, and approaches to learning they encountered in the Ontario school system. However, the mismatch between school experiences in their home countries and the Canadian context introduced stress into their integration process, particularly for those trying to complete coursework required for applying to post-secondary institutions. This finding aligns with research by Benimmas et al. (2017), who found that parents of NY identified school differences, such as conflicting evaluation criteria, as complicating their children’s integration.

4.2 Evolving language identity

Gaining competence and confidence in a new language is a common hurdle for many newcomers during their integration experience (Kaufmann, 2021). For our participants, this challenge was further complicated by their integration into a French-language school within a predominantly English-speaking community. Further, several participants spoke other languages at home or at other points in their development, having lived in different countries, which added layers of complexity. Reflecting findings from other research (Brisson, 2018), the patterns of plurilingualism and transnationalism among our participants made their integration into a francophone school particularly challenging and served as a barrier to adopting a francophone identity. In fact, participants rejected the notion of a francophone identity, choosing to align with the cultural and linguistic identity of their home countries while prioritizing competence in English to better navigate the predominantly anglophone community they encountered daily in Canada. Notably, they expressed disdain for using French at school, questioning its relevance beyond the classroom for both their current and future lives.

Previous research suggests that newcomers often associate francophone identity with monolingualism and believe that true francophones are from Quebec or France (Brisson, 2018: Levasseur, 2016). This perception can hinder their integration into francophone communities and Canadian society. Participants in our study echoed these sentiments, identifying as neither francophone nor Canadian. The phenomenon of multilingual, transnational newcomers rejecting both francophone and Canadian identities could pose challenges for Canada’s efforts to sustain bilingualism by encouraging French-speaking immigrants to settle outside of Quebec. As Lupal (2019) suggested, the French-Canadian community is evolving into a more heterogeneous francophone community. Therefore, support for French-speaking newcomers in francophone or anglophone contexts must adapt to and honor the multilingual, multinational composition of these groups.