- 1Public Health, Societies and Belonging, Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Faculty of Health Sciences, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, South Africa

- 3School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

- 4Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

- 5Evidence Based Solutions, Cape Town, South Africa

- 6College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

Introduction: The outbreak of the SARS COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 led to a total disruption of life and impacted mental health negatively worldwide. Studies across many countries showed the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health status of students enrolled in higher institutions due to the disruption of the school year and learning. This study was aimed a measuring the prevalence and psychosocial determinants of psychological distress experienced by college and university students during the COVID-19 lockdowns in South Africa.

Methods: Students aged 18–35 years that were enrolled at tertiary institutions nationally were invited to participate in the online survey. The survey was conducted at the peak of the epidemic in South Africa from 18 June till 18 September 2020. The Kessler −10 (K10) screening scale was used to measure psychological distress among students.

Results: A total of 6,810 young people aged of between 18 and 35 years participated in the study. The majority of these students were aged between 18 and 24 years old (83.9%). About one third (66.7%) of the youth reported that they had mild to severe distress (MSD). The prevalence of psychological distress among the youth differed significantly by age group, gender, risk perception of contracting COVID-19, year of study, institution and community type (p < 0.05). Logistics regression investigated the socio-demographic factors associated with psychological distress. Older students aged 25–29 years (aOR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.62–0.88) and 30–35 years (aOR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.55–0.97), male students (aOR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.72–0.95) and those with moderate (aOR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.49–0.95), low (aOR = 0.41, 95% CI [0.30–0.57]) and very low (aOR = 0.22, 95% CI 0.16–0.31) risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19 were significantly less likely to experience MSD. Fourth year students (aOR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.14–1.69), and students in universities of technology (aOR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.20–2.04) were significantly more likely to have MSD.

Discussion: This study showed high prevalence rates of psychological distress among students during the COVID-19 pandemic. These finding highlights the need for tertiary institutions to put holistic mental health services and interventions at the center of their health and wellness programs.

Introduction

The outbreak of the SARS COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 led to a total disruption of life across the world for citizens of most countries. These widescale changes in everyday life, through rolling lockdowns and movement restrictions, may have negatively impacted young people more acutely when compared to adults. In addition, young people’s formal education, where they have access to it, was severely impacted by the pandemic (Calear et al., 2022). Education, social support mechanisms and access to health services need to be maintained with parents and/or guardians playing a key role. A World Health Organization (WHO) multi-country survey conducted in about eight countries reported rates of psychological distress in excess of 35%, painting a disturbing picture about the mental state of higher education students (Auerbach et al., 2018). The rolling lockdown actions across the globe also placed both the students and their educators under conditions not previously encountered, whereby online remote forms of instruction were the only tools available.

Several studies have been conducted in a number of countries that aimed to measure the levels of psychological distress and mental health challenges among students. An online survey administered to students attending Texas A&M University during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that 48.14 and 38.48% of them had moderate-to-severe depression and anxiety, respectively (Wang et al., 2020). Moreover, 72.26% of these students reported that their stress and anxiety levels increased during the pandemic, with below half of the participants (43.25%) being able to adequately cope with their current circumstance (Wang et al., 2020). Another study by Son et al. (2020) also found elevated rates of depression and anxiety due to the COVID-19 outbreak. These students identified contributing stressors such as fear and worry about their own health and that of loved ones, concerns surrounding academic performance, sleep pattern disruptions and decreased social interactions owing to physical distancing (Son et al., 2020). Two studies carried out in China found that being between the age of 26–30 years old, low economic status, decreased social support and having relatives affected by COVID-19 all contributed to symptoms of anxiety, while living with parents and having a stable family income were protective against developing negative mental health issues (Fu et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2020). A study carried out in the UK demonstrated similar findings, where undergraduate students reported that the worry associated with contracting COVID-19 contributed to a negative mental health state (Evans et al., 2021).

A survey conducted among university students at two South African universities revealed a notable prevalence of major depressive episodes (MDE) (%), suicidal ideation (%), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (%) during the period coinciding with the prevalence of COVID-19 (Bantjes et al., 2023). In a separate study aimed at assessing depression, anxiety, and stress along with their associated factors among Ethiopian university students in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was observed that mental health posed a significant challenge, particularly among females (Simegn et al., 2021). Meanwhile, intern-nursing students at Alexandria University Hospitals in Egypt linked their COVID-19-related poor mental health to concerns about infection and transmission to their families, coupled with accumulating feelings of strain and worthlessness. Interestingly, being male and undergoing training in the pediatric unit emerged as protective factors in this context (Eweida et al., 2020). Overall, these studies highlight the diverse mental health challenges faced by university students in different regions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A qualitative study conducted in 2020, with fifth year medical students at a university in KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa, found that they had experienced challenges with regards to teaching and learning; a stressful and at times overwhelming year; mental health issues and; developing strategies to cope. These students reported that they felt that the institutions disregarded their mental state and they were offered little support from management and staff on coping mechanisms (Ross, 2022).

Mental health challenges and coping skills thereof have emerged as key areas that need more attention particularly among young people. Large numbers of young people across the world and socio-economic class have faced many mental health challenges during the past few during the COVID-19 period (Asanov et al., 2021; Branquinho et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2020; Houghton et al., 2021). Mental health challenges have been shown to be affecting young people regardless of their socio-economic status or even access to good resources.

Although bio-medical research had its merits in informing pandemic control across the globe, clinical care and hospital provisions took precedent and only a small portion of research and resources were channeled toward mental health research, especially in low- and middle-income countries where resources are limited. There is now a growing body of evidence highlighting mental health during COVID-19 lockdowns, but very few of these studies have been conducted in South Africa. Hence, in this paper, we aim to evaluate the prevalence and psychosocial determinants of psychological distress and mental health challenges experienced by college and university students during the COVID-19 lockdowns in the country.

Methods

Study population

Young people between the ages of 18–35 years of age who were either in some form of Higher Education and training or enrolled in a tertiary institution (college or university) in all nine provinces in South Africa.

Data collection

The Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) in collaboration with the Department of Science, Innovation, Higher Health™ and UNFPA conducted an online survey to understand the social impact of COVID-19 on youth aged 18–35 years, enrolled within the Post School Education and Training (PSET) Sector in South Africa. Young people between the ages of 18–35 years of age enrolled in a Higher Education and training institution or tertiary institution (college or university) in all nine provinces in South Africa during the time of the online survey were eligible to participate. Some of the institution types were Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions, Universities of Technology, universities, private tertiary education colleges and Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs).

Eligible youth were invited to participate in the online survey, which was hosted on the BINU data free platform: https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/CovidYouth. The invitation to participate was widely distributed among strategic partner networks in higher education institutions and government. Social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter, and mainstream media such as television and radio interviews were used to inform potential participants about the survey. Additionally, two bulk SMS campaigns were that were geo-targeted across the nine provinces were implemented to further encourage student participation. The survey was conducted at the peak of the epidemic in South Africa from implemented from 18th June till 18th September 2020 when the country was going through various lockdown restriction levels. During these lockdown alert levels there were restrictions on large gatherings in order to reduce the risk of transmission and to contain outbreaks.

Participants

Young people between the ages of 18–35 years of age enrolled in a Higher Education and training institution or tertiary institution (college or university) in all nine provinces in South Africa during the time of the online survey. Some of the possible institution types were Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions, Universities of Technology, universities, private tertiary education colleges and Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs). Students were not asked whether they were enrolled part-time or full-time.

Measures

The primary outcome measure was the Kessler −10 (K10) screening scale to measure current non-specific psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2002). The scale has been validated in the South African context (Andersen et al., 2011). The 10 item Likert scale asked questions such as, in the past 4 weeks how often, “did you feel tired out of no good reason,” “did you feel hopeless,” “did you feel nervous,” and “did you feel so nervous that nothing could calm you down.” The response options were 5 = all of the time, 4 = most of the time, 3 = some of the time, 2 = a little of the time and 1 = none of the time. The sum score across the 10 items was coded into two categories with a total score < 20 indicating minimal psychological distress and scores over 20 indicating mild to severe psychological distress (Andrews and Slade, 2001).

The independent variables included were age group (18–24/25–29/30–35 years), gender (male/female/prefer not to say), population group (Black African/White/Colored/Indian/Asian/Other), risk perception of contracting COVID-19 (very high/high/moderate/low/very low risk), year of study (first/second/third/fourth or higher), institution type (TVET/University of Technology/University/Private College/Other), community type (city/suburb/township/informal settlement/rural traditional or tribal area/farm).

Ethical clearance

The study received ethics approval from the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Research Ethics Committee (protocol number REC 4/2020) and Universities South Africa (USAf) through Higher Health. Participants in the survey provided consent via the online platform prior to proceeding to the questionnaire.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted in Stata 15.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, United States). The data were benchmarked (weighted) using estimates of the youth population aged 18–35 years attending educational institutions by gender, population group, age and resident province (Stats SA, 2019). Differences in psychological distress across categories of the independent variables were compared using 95% Confidence Intervals and Chi-square tests. Univariate and multiple logistic regression models assessed the association between the independent variables and psychological distress. All variables found to be significant in the univariate logistic regressions were entered into the multiple logistic regression model. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the PSET students

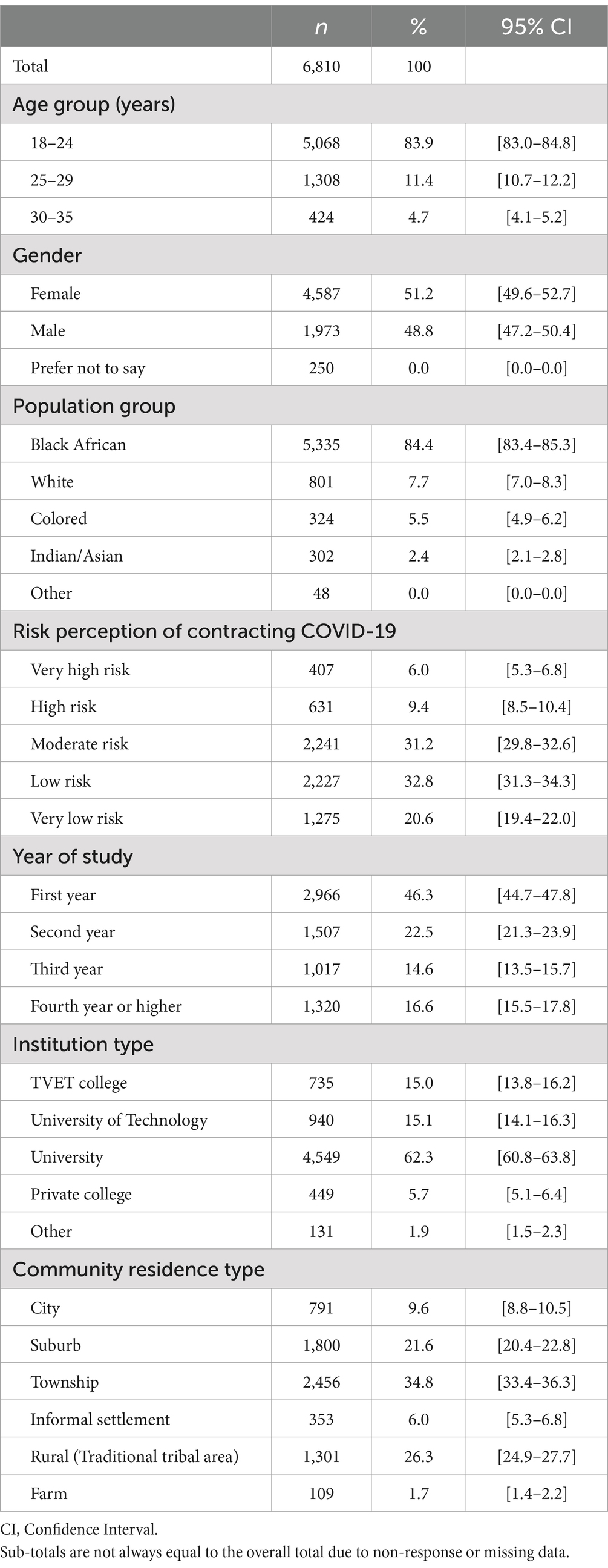

The study sample comprised of 6,810 young people aged between 18 and 35 years inclusive who were enrolled in a PSET institution in all nine provinces in South Africa (Table 1). Most of the students (83.9, 95% CI 83.0–84.8) were aged between 18 and 24 years. Female respondents constituted 51.2% (95% CI 49.6–52.7) of the study sample. Black African youth accounted for 84.4% (95% CI 83.4–85.3) of the study participants.

With regard to their perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, most youth believed they had low risk (32.8, 95% CI 31.3–34.3) or moderate risk of contracting COVID-19 (31.2, 95% CI 29.8–32.6) respectively. Just under half of the PSET students (46.3, 95% CI 44.7–47.8) were first year students while slightly over one fifth (22.5, 95% CI 21.3–23.9) were in their second year Nearly two thirds (62.3, 95% CI 60.8–63.8) of students were enrolled in universities with similar proportions enrolled in TVET colleges (15.0, 95% CI 13.8–16.2) or Universities of Technology (15.1, 95% CI 14.1–16.3). Just over one third (34.8, 95% CI 33.4–36.3) of PSET students resided in townships, while 26.3% (95% CI 24.9–27.7) of youth resided in rural or traditional tribal areas.

Prevalence of psychological distress among PSET students

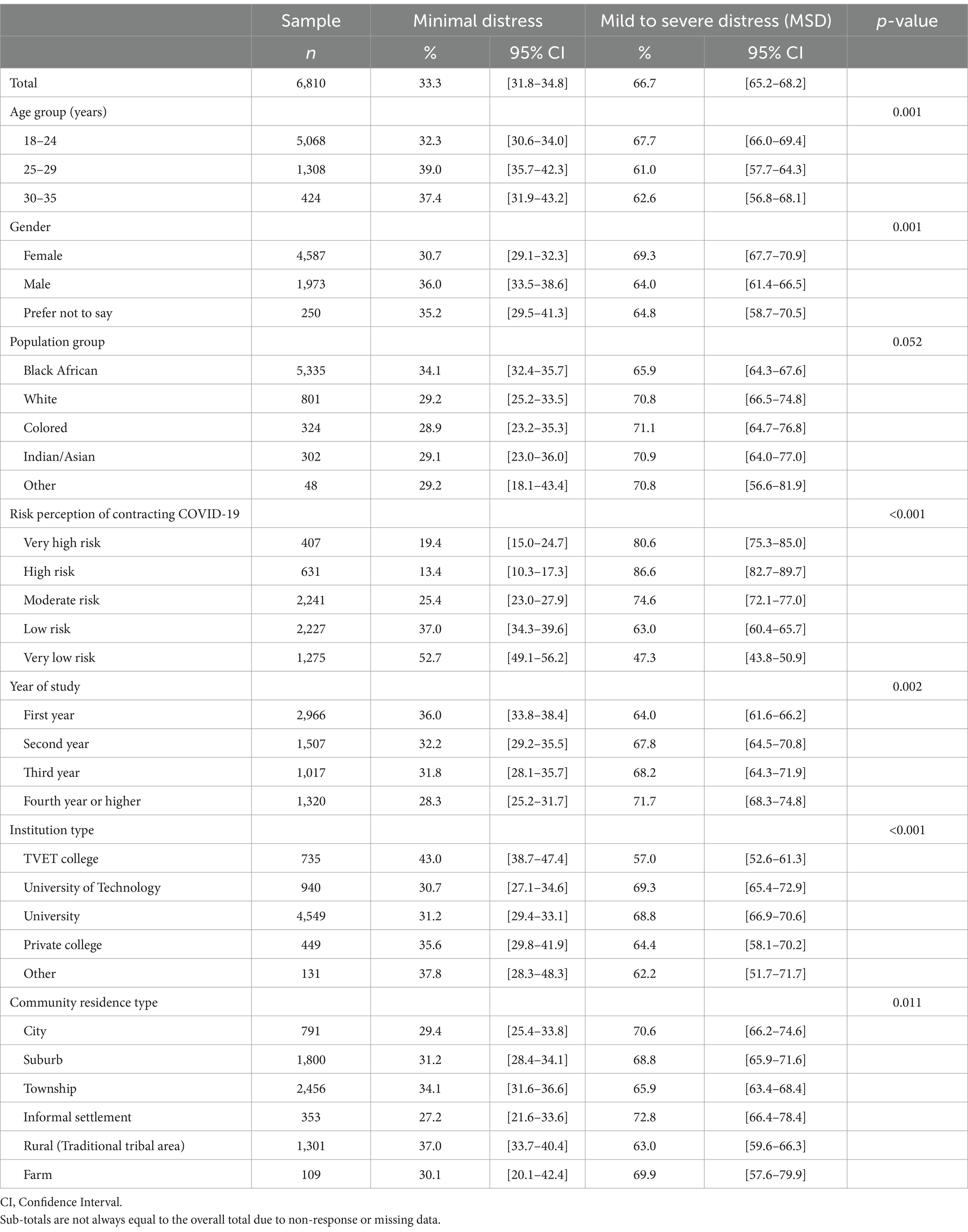

Overall, about two thirds (66.7, 95% CI 65.2–68.2) of students had MSD (Table 2). The prevalence of psychological distress among students differed significantly by age group, gender, risk perception of contracting COVID-19, year of study, institution type and community type (p < 0.05). The findings show that over two thirds of the youngest students aged 18–24 years had MSD (67.7, 95% CI 66.0–69.4), and the proportion of MSD was lower within the older age groups. In terms of gender disparities, among females MSD was 69.3% (95% CI 67.7–70.9) compared to 64.0% (95% CI 61.4–66.5) among their male counterparts.

Table 2. Prevalence of psychological distress by socio-demographic characteristics among PSET students.

The prevalence of MSD increased within increasing risk perception of contracting COVID-19. The prevalence of MSD was highest among students with a high (86.6, 95% CI 82.7–89.7) or very high (80.6, 95% CI 75.3–85.0) risk perception. Similarly, the prevalence of MSD was higher among students who were well into their qualifications compared to first year students. The prevalence of MSD among students enrolled in universities of technology (69.3, 95% CI 65.4–72.9) and universities (68.8, 95% CI 66.9–70.6) were higher compared to their counterparts enrolled in TVET and private colleges. Levels of MSD were highest among students living in informal settlements (72.8, 95% CI 66.4–78.4), cities (70.6, 95% CI 66.2–74.6) and farms (69.9, 95% CI 57.6–79.9) compared to other community types.

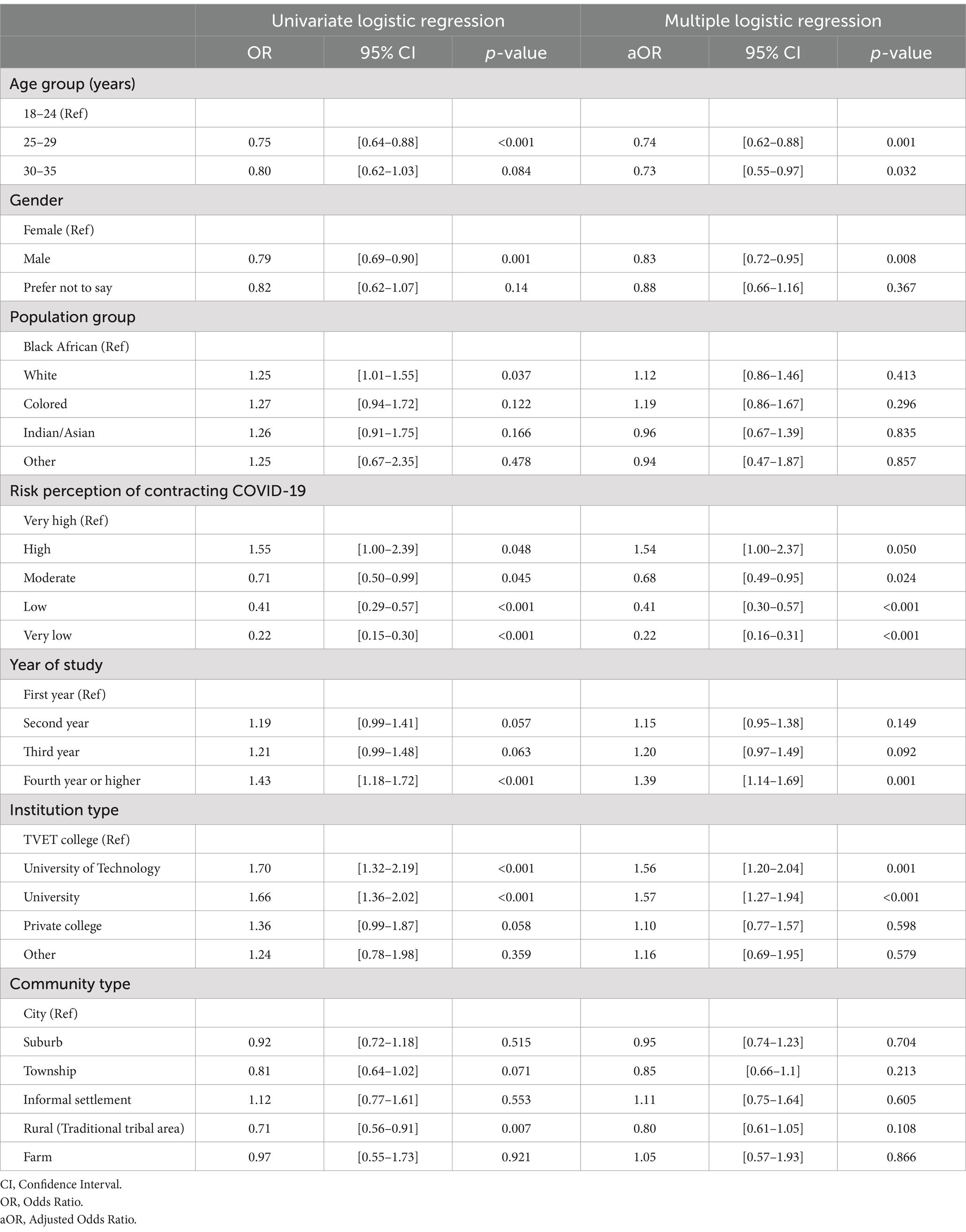

Factors associated with psychological distress among PSET students

Table 3 shows the results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of factors associated with psychological distress among students enrolled in PSET. Multivariate logistic regression results showed that older students, those aged 25–29 years (aOR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.62–0.88, p = 0.001) and those aged 30–35 years (aOR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.55–0.97, p = 0.032) were significantly less likely to have MSD compared to their younger counterparts. MSD was significantly lower among PSET male students (aOR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.72–0.95, p = 0.008) than female students.

Table 3. Univariate and Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with psychological distress among PSET students.

The MSD was significantly lower among students with moderate (aOR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.49–0.95, p = 0.024), low (aOR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.30–0.57, p < 0.001) and very low (aOR = 0.22, 95% CI 0.16–0.31, p < 0.001) risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19 compared to those with very high risk perceptions. Fourth year PSET students were significantly more (aOR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.14–1.69, p = 0.001) likely to have MSD than those who were in their first year of study. Students enrolled in universities of technology (aOR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.20–2.04, p = 0.001) and universities (aOR = 1.57, 95% CI 1.27–1.94, p < 0.001) were significantly more likely to report that they were distressed with MSD than those in TVET colleges.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and general wellbeing among young people who were enrolled in PSET institutions of higher learning in South Africa during 2020–2021. To our knowledge there is a paucity of data for PSET students in the height of the COVID-19 rolling lockdowns in South Africa. Our findings demonstrates that two thirds of PSET students had mild to severe psychological distress. The highest prevalence of MSD was found among students who were further along into their studies, among the younger age group of 18–24 years, females, those with high risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19 and those attending universities of technology or universities. Students in their third and fourth year may have had the additional anxiety of many uncertainties including the risk of not completing their studies or graduate, and the challenges of job seeking and trying to earn an income soon after they complete their studies.

The results also show that psychological distress varied based on age of the participants with younger students showing much higher MSD compared to students who were of older age. The youngest of students who are still teenagers aged 18–19 years, may have been at the time still dealing with transition from high school and newly arrived at PSET. Similar findings have been observed in other studies conducted among university students in other African settings (Kebede et al., 2019; Simegn et al., 2021). The younger students were students who were still enrolled for undergraduate qualifications, and therefore potentially more distressed by the disruption of their academic year due to the COVID-19 lockdowns. The newly enrolled students were also possibly transitioning from high school, and still learning how to cope with the demands of college and university education when lock down started.

The results from this study corroborate with other studies that found that psychological distress among students in several countries was on the increase even the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Auerbach et al., 2018). Several other studies conducted among students at colleges and universities during the COVID-19 pandemic have also reported increased rates of anxiety and psychological distress (Banati et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020; Simegn et al., 2021).

This study also found that psychological distress showed marked differences between genders with male student having less psychological distress when compared to female students, which concurs with previous studies in other countries (Chen and Lucock, 2022; Simegn et al., 2021). This study did not find significant differences in psychosocial distress between the different racial groups of students in South Africa. However previous South African studies have reported racial differences between groups, with Black African adults reportedly having higher levels of psychological distress when compared to other racial groups (Harriman et al., 2021; Herman et al., 2009). The study also showed that students who perceived themselves to have a very high risk of contracting the COVID-19 virus also showed very high levels of psychological distress compared to those with a lower risk perception of getting infected.

The present study is not without limitations. The main limitation of this study is that data collection had to be conducted on an online platform due to the lockdown regulations. Online surveys are subject to selection bias as participants had to have access to a smart phone or electronic tablet to be able to participate. However, more than 91% of South Africans have smart phones (Mzekandaba, 2020). In this regard, the data was benchmarked to be representative of the PSET student population in South Africa. South Africa with a well-known history of inequality and disparities in the country students in poorly resourced institution were not able to participate in adequate numbers compared to those who were in more affluent institutions. This was evident when looking closely at response rates from the different categories of tertiary institutions, with universities having the highest participation rates compared to Universities of Technology and community colleges.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic across the globe evidently had far reaching consequences and clearly its negative impact was mostly felt by the youth and other vulnerable groups such as the poor and children. Results from this study do clearly show the prevalence rates among students are higher as compared to the general population. The observed high rates of psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown among students in the PSET system are of concern. Even though we do not yet understand the long-term effects of this distress post-COVID-19 lockdowns, the findings from the study on the prevalence and psychosocial determinants of psychological distress among PSET students during COVID-19 lockdowns have several implications for programming and interventions.

Given that about one-third of the students reported mild to severe distress, programming efforts should focus on providing targeted mental health support to this demographic. This could involve developing counseling services, online mental health resources, and outreach programs tailored to the specific needs of PSET students. Programming efforts could also include awareness campaigns and online programs to reduce stigma around seeking mental health support, raising awareness about available resources, and encouraging open discussions on campus mental health.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee (HSRC REC) (Protocol number: REC 5/03/20). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TM: Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. IN: Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ND: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Writing – review & editing. AD: Writing – review & editing. NZ: Writing – review & editing. OS: Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – review & editing. ST-R: Writing – review & editing. PR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The data collection for this study was supported by the South African Department of Science, Technology and Innovation, Higher Health and the UNFPA.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for taking their time to complete the survey. We acknowledge the Provincial research teams from the Higher Health South Africa who coordinated the implementation of the survey in the Technical Vocational Education and training (TVET) institutions.

Conflict of interest

OS was employed by the company Evidence Based Solutions.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andersen, L. S., Grimsrud, A., Myer, L., Williams, D. R., Stein, D. J., and Seedat, S. (2011). The psychometric properties of the K10 and K6 scales in screening for mood and anxiety disorders in the south African stress and health study. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 20, 215–223. doi: 10.1002/mpr.351

Andrews, G., and Slade, T. (2001). Interpreting scores in the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) Aus NZ. J. Public Health 25, 494–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x

Asanov, I., Flores, F., McKenzie, D., Mensmann, M., and Schulte, M. (2021). Remote-learning, time-use, and mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Devel. 138:105225. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105225

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127, 623–638. doi: 10.1037/abn0000362

Banati, P., Jones, N., and Youssef, S. (2020). Intersecting vulnerabilities: the impacts of COVID-19 on the psycho-emotional lives of young people in low- and middle-income countries. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 32, 1613–1638. doi: 10.1057/s41287-020-00325-5

Bantjes, J., Swanevelder, S., Jordaan, E., Sampson, N. A., Petukhova, M. V., Lochner, C., et al. (2023). COVID-19 and common mental disorders among university students in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 119:3594. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2023/13594

Branquinho, C., Kelly, C., Arevalo, L. C., Santos, A., and Gaspar de Matos, M. (2020). “Hey, we also have something to say”: a qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people’s experiences under COVID-19. J. Comm. Psychol. 48, 2740–2752. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22453

Calear, A. L., McCallum, S. M., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A. J., Nicolopoulos, A., Brewer, J. L., et al. (2022). The sources of strength Australia project: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a peer-connectedness school-based program to promote help-seeking in adolescents. J. Affective Disord. 299, 435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.043

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Chen, B., Li, Q., Zhang, H., Zhu, J., Yang, X., Wu, Y., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on medical staff and the general public. Curr. Psychol. 41, 5631–5639. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01109-0

Chen, T., and Lucock, M. (2022). The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey in the UK. PLoS One 17:e0262562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262562

Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., and Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian J. Behav. Sci. 52:177.

Evans, S., Alkan, E. J. Z., Bhangoo,, Tenenbaum, H., and Ng-Knight, T. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Res. 298:113819. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819

Eweida, R. S., Rashwan, Z. I., Desoky, G. M., and Khonji, L. M. (2020). Mental strain and changes in psychological health hub among intern-nursing students at pediatric and medical-surgical units amid ambience of COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive survey. Nurse Educ. Pract. 49:102915. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102915

Fu, W., Yan, S., Zong, Q., Anderson-Luxford, D., Song, X., Lv, Z., et al. (2021). Mental health of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. J. Affect. Disord. 280, 7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.032

Harriman, N., Williams, D. R., Morgan, J. W., Sewpaul, R., Manyaapelo, T., Sifunda, S., et al. (2021). Racial disparities in psychological distress in post-apartheid South Africa: results from the SANHANES-1 survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 57, 843–857. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02175-w

Herman, A. A., Stein, D. J., Seedat, S., Heeringa, S. G., Moomal, H., and Williams, D. R. (2009). The south African stress and health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. S. Afr. Med. J. 99, 339–344. doi: 10.1002/pits.20388

Houghton, B., Bailey, A., Kouimtsidis, C., Duka, T., and Notley, C. (2021). Perspectives of drug treatment and mental health professionals towards treatment provision for substance use disorders with coexisting mental health problems in England. Drug Sci. Policy Law 7:205032452110553. doi: 10.1177/20503245211055382

Kebede, M. A., Anbessie, B., and Ayano, G. (2019). Prevalence and predictors of depression and anxiety among medical students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst. 13:30. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0287-6

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L. T., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32, 959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074

Mzekandaba, S. SA’s smartphone penetration surpasses 90%. (2020). Available at: https://www.itweb.co.za/article/sas-smartphone-penetration-surpasses-90/xA9PO7NZRad7o4J8 (Accessed August 22, 2024)

Ross, A. J. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 – experiences of 5th year medical students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 64, e1–e9. doi: 10.4102/safp.v64i1.5483

Simegn, W., Dagnew, B., Yeshaw, Y., Yitayih, S., Woldegerima, B., and Dagne, H. (2021). Depression, anxiety, stress and their associated factors among Ethiopian University students during an early stage of COVID-19 pandemic: an online-based cross-sectional survey. PLOS One. doi: 10.1371/journal.pon.0251670

Stats, SA. (2019). Quarterly labour force survey: quarter 4. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria: South Africa.

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., and Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: interview survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22:e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279

Keywords: youth, mental health, psychological distress, COVID-19, South Africa

Citation: Sifunda S, Sewpaul R, Mokhele T, Mabaso M, Naidoo I, Dukhi N, Parker S, Davids A, Zungu N, Shisana O, Makgalemane R, Thakoordeen-Reddy S and Reddy P (2024) Prevalence, correlates of psychological distress and mental health challenges among college and university students during the COVID-19 lockdowns in South Africa. Front. Educ. 9:1484849. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1484849

Edited by:

Laisa Liane Paineiras-Domingos, Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), BrazilReviewed by:

Juan Moisés De La Serna, International University of La Rioja, SpainEvelyn Fernández-Castillo, Universidad Central Marta Abreu de Las Villas, Cuba

Copyright © 2024 Sifunda, Sewpaul, Mokhele, Mabaso, Naidoo, Dukhi, Parker, Davids, Zungu, Shisana, Makgalemane, Thakoordeen-Reddy and Reddy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Natisha Dukhi, bmR1a2hpQGhzcmMuYWMuemE=

Sibusiso Sifunda

Sibusiso Sifunda Ronel Sewpaul

Ronel Sewpaul Tholang Mokhele

Tholang Mokhele Musawenkosi Mabaso1

Musawenkosi Mabaso1 Inbarani Naidoo

Inbarani Naidoo Natisha Dukhi

Natisha Dukhi Adlai Davids

Adlai Davids Nompumelelo Zungu

Nompumelelo Zungu