- Smith College Wurtele Center for Leadership, Northampton, MA, United States

Institutions of higher education almost universally promise to produce society’s future leaders and changemakers. However, collegiate leadership programs are often more attractive and accessible to students from dominant backgrounds, resulting in a lack of diversity. Further, students participating in formal collegiate leadership programming, whether curricular or co-curricular, are frequently taught a one-size-fits-all style of leadership that focuses on individual traits and skills and fails to teach students how to facilitate change with real groups of complex and diverse human beings. This study explores the ways in which undergraduate students gain powerful collaborative leadership skills and begin to redefine leadership via an alternate route in their college experience: applied group projects embedded in disciplinary liberal arts courses. Such projects give students a chance to redefine leadership for themselves, and practice a style of leadership that is more adaptable, contextually embedded, power-aware, and non-hierarchical. We term this “small-l” leadership. In this case study, we explore the role of collaborative group projects in the development of “small-l” leadership through a qualitative study driven by grounded -theory methodology followed by a thematic analysis. Through a series of individual and oral interviews with 18 undergraduate students enrolled in 10 distinct courses at a small liberal arts college, we find that long-term collaborations in classrooms help students: (1) develop heightened sensitivity and skill in navigating group dynamics, (2) gain consciousness of how to navigate their own agency in relation to that of the group, and (3) begin to adopt a more expansive definition of leadership. We determine that with a handful of small interventions, instructors can significantly enhance “small-l” leadership learning through group work. Altogether, our findings illustrate how collaborative learning in liberal arts classrooms can meaningfully contribute to the development of leaders who impact the world around them by co-creating with others across disciplines and differences.

Introduction

There are very few colleges and universities in the United States that do not, somewhere in their mission statements, mention the word “leader” or “leadership.” Central to the identity of higher educational institutions is the idea that they are preparing the world’s future leaders, equipping students with the knowledge and skills they need to step forward and tackle society’s greatest challenges. This emphasis emerged in the last 40–50 years, as the number of leadership programs exploded on college and university campuses in tandem with the rise of what Barbara Kellerman dubs the “leadership industry” in the US in the late 20th century: a vast proliferation of corporate trainings, seminars, workshops, books, podcasts, consultancies, etc., designed to expand productivity through professional development (Kellerman, 2012). As of 2024, there are at least 237 undergraduate degree programs in leadership offered at US colleges and universities, hundreds of additional graduate programs, and countless other leadership workshops and trainings offered to students through the co-curriculum (International Leadership Association, n.d.). This amounts to what some critics dub nothing less than a “student leadership industrial complex” (Biswas, 2019).

Certainly, as the higher education sector finds itself under increasing scrutiny and skepticism from the general public (Belkin, 2024), preparing leaders who can take on complex adaptive challenges is all the more salient a selling point for colleges and universities. Yet many of the formal leadership programs in American colleges and universities—whether curricular or co-curricular—reinforce what we call “Big-L” leadership models, which groom students to focus their energy on adopting positional power, without attending to ethical considerations of the impact individuals might have in those roles. These models frequently emphasize individualistic, trait-based approaches, often ignoring the inherently relational, contextual, and power-embedded nature of leadership (Liu, 2017; Collinson and Tourish, 2015; Dugan and Leonette, 2021). This is a problematic approach, considering that academic scholarship on leadership is trending toward relational and collaborative models (Liu, 2017; Haslam and Reicher, 2016; Ospina and Uhl-Bien, 2012). Because most degree and co-curricular leadership programs focus on building individual skills devoid of context, or discuss leadership theory without practical application, or both, students do not gain direct practice leading change within real groups of multifaceted human beings. This causes many undergraduate students to falsely assume that “leadership” is either a position of power, or a universal set of traits or capacities that apply in all settings. Adding to the problem is the fact that students from marginalized backgrounds, who often struggle to feel a sense of belonging on college campuses, can feel disdain toward the label of “leader,” and consequently often either do not opt into formal leadership programs or pay a significant price in terms of mental health when they do (Arminio et al., 2000; Domingue, 2015).

Our work at the Wurtele Center for Leadership at Smith College is driven by a desire to disrupt traditional models of collegiate leadership development. The Wurtele Center is a small unit embedded in an American liberal arts college, which seeks to build bridges across students’ curricular and co-curricular experiences in order to strengthen their capacities to effectively work with others across differences to effect positive change. The research team included the director of the Wurtele Center, who also serves as an instructor at the college, and two undergraduate researchers. We were curious about how the Wurtele Center can foster an institutional critique of more traditional, individualistic, trait-based approaches to leadership learning, navigating toward more contextually-relevant, relationally-focused, and power-aware pedagogies, especially within the unique context of a women’s college. At the Wurtele Center, we describe this approach as “small-l” leadership development, which positions leadership as a set of socially-situated practices rather than a role, sheds light on the interpersonal nature of collaborative change work, and highlights for students the impossibility of leading toward a positive impact at any scale entirely on one’s own. Our mission is to broaden our students’ vision beyond the “Big-L” leadership models (focused on achieving high-level positional leadership) that many of them have absorbed via popular cultural discourses and/or previous leadership development experiences. Given that formal co-curricular leadership programs are often inaccessible or unappealing for many students, even in an environment designed specifically to support women and gender non-conforming individuals, we explored where “small-l” leadership learning might be happening within the academic classroom. While the majority of colleges like ours tend to place “leadership development” outside of the liberal arts curriculum, confining it to the co-curricular world of Student Affairs or offering a Leadership Studies minor or certificate, we looked to the collaborative work situated within disciplinary classrooms to find out how students might be (often unknowingly) gaining an increasingly important set of leadership skills within their curricular experiences.

Through our exploration of the scholarly literature in the field of leadership development, we found ample discussion of aptitude for engaging in teamwork as one of the many skillsets pursued by college-level leadership development models. Of particular note is the National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs’ (NCLP) Social Change Model of Leadership Development, which challenges the idea that leadership is positional in nature, and emphasizes Collaboration as one of the “Seven C’s for Change” student leaders should adopt (Komives and Wagner, 2016). At the same time, there is a wealth of scholarship in the literature on teaching and learning in the disciplinary college classroom that highlights the benefits of collaborative learning techniques, including group work. Studies published in the last decade show that socially active learning increases student performance in STEM classrooms (Freeman et al., 2014), even if students do not always perceive that they have learned more as a result of these learning experiences (Deslauriers et al., 2019). Scholars in other fields, particularly the social sciences, have likewise explored the ways in which collaborative work can enrich students’ ability to adopt the scholarly practices necessary to succeed in their discipline (Glotfelter et al., 2022; Monson, 2019). And as humanities disciplines increasingly face enrollment challenges and seek to demonstrate the value of a humanities degree, collaborative skills are increasingly listed as a key outcome resulting from group projects within those disciplines (Grobman and Ramsey, 2020).

Rarely, however, do these two scholarly conversations overlap, as the literature on leadership development largely locates it outside of the liberal arts curriculum, and the literature on college teaching and learning frequently misses the potential for leadership development inherent in collaborative pedagogical practices. Additionally, meta-analyses of literature on the outcomes of small-group pedagogies frequently leave out studies that rely on qualitative evidence, which provides crucial evidence of the nuances of group processes and how they might affect learning outcomes (Monson, 2019; McKinney, 2017). This case study seeks to place these two areas of inquiry in conversation with one another, to explore whether and how leadership development might be fruitfully embedded within the context of applied academic learning.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews of Smith College undergraduate students completing collaborative projects in their current coursework. This case study was conducted over the course of four semesters in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 academic years, and received approval from the Smith College IRB.

Sample and recruitment

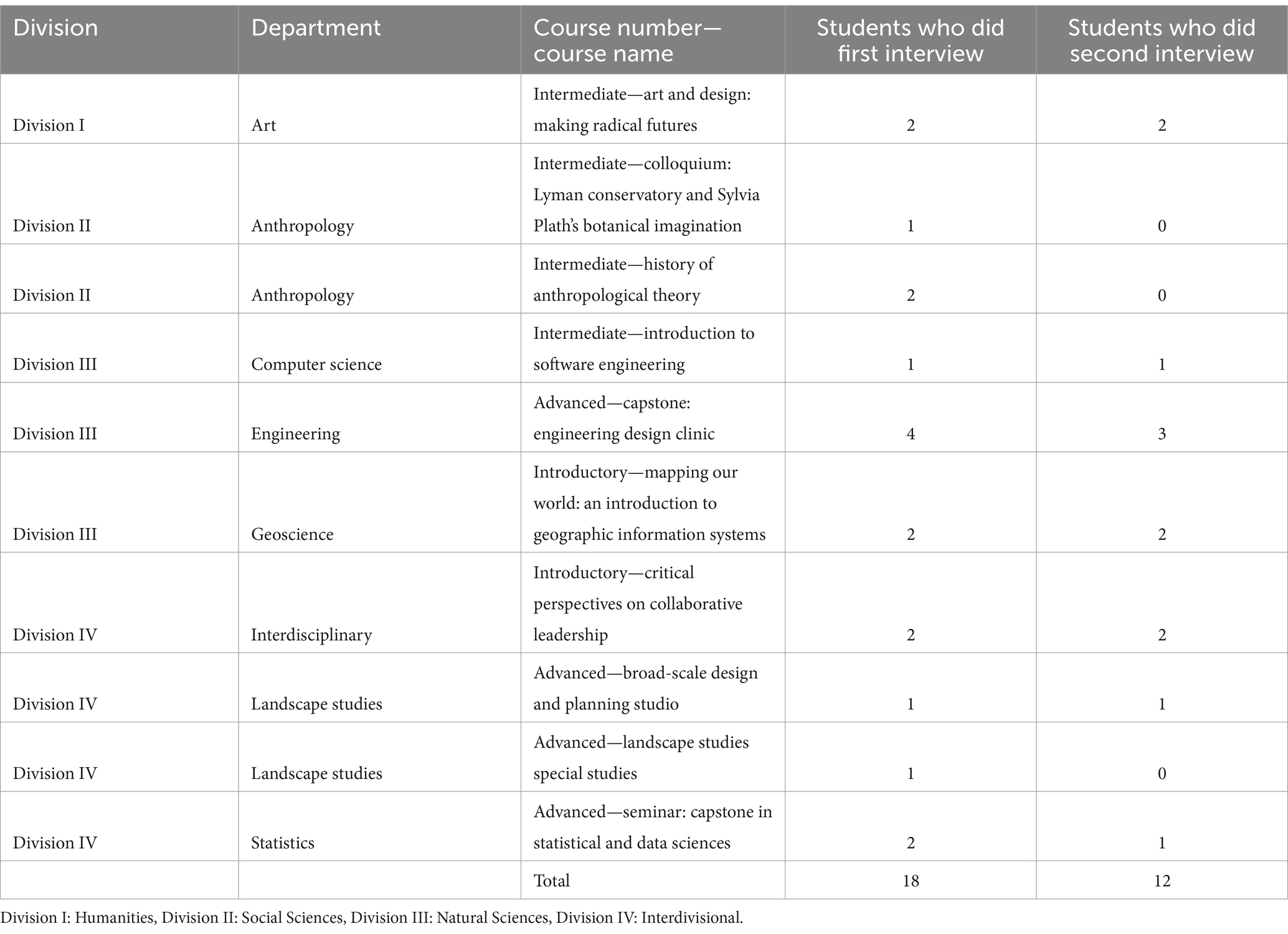

Participants were recruited from 10 academic undergraduate courses with significant collaborative components, such as informal discussion groups, small-sized studio models, and semester-long applied projects. These courses were identified through a review of the course catalog and from existing relationships with instructors and/or familiarity with their pedagogical approaches. Courses represented a range of disciplines, spanning STEM, Humanities, and Arts departments, and varied in rigor from 100-level introductory classes to senior-level seminars or independent studies projects conducted in teams (Table 1). Instructors were contacted, provided the details of the study, and asked to send out a template recruitment email to their students who could then choose to participate based on their time and interest in the study. Researcher understanding of students’ experiences with collaboration in these courses comes entirely from interviews, as there was no further communication with course instructors after this point.

The study involved two rounds of interviews, one toward the beginning of the project/class and a second toward the end or after the class had concluded (typically at the beginning of the following semester). A total of 18 undergraduate students across these 10 courses participated in the first round of interviews, and of those, 12 students completed a second interview (Table 1). In order to incentivize participation among students, study participants were offered compensation in “Dining Dollars,” a Smith College-specific campus currency that could only be used at campus restaurants or stationary stores. Study participants were awarded $15 Dining Dollars only after completing both interviews. We did not conduct a demographic questionnaire for any subjects, and any information related to identity or demographics provided by students was volunteered in the interviews.

Table 1. A table describing the number of undergraduate students we interviewed for this study, the courses they were taking, and the department/division of each course.

Interview procedure

Following a broad review of the literature across domains on leadership-related topics and study design, a series of interview questions were designed to gain the fullest possible understanding of the collaborative processes these participants’ engaged in during their course. Both the pre- and post-course interviews were semi-structured around a set of existing questions, where the researchers used the question list as a guide but allowed participants’ responses to shape the conversation by asking follow-up questions or delving deeper into certain topics. In this way, the researchers set the topics of the interview and guided participants, but what participants identified as important remained central to the interviews.

Questions asked participants to describe the structure of their projects (for instance, how tasks were divided up, goals of the project, and extent of instructor scaffolding), their experiences working with their group members (how close the group members felt and how relationships evolved), and participants’ perceptions of collaboration and leadership more broadly (how they would define the terms, experience with the concepts outside of class, etc.). To assess the change in opinions and experiences over time, the first interview also asked participants to discuss how they imagined the group project would evolve over time, and the second interview asked participants to reflect on those predictions. A complete list of all questions is included in Supplementary Information 1.

These interviews were conducted orally and one-on-one. While researchers might have interviewed multiple members of the same class, participants did not interact in the context of this research project. Interviews were conducted either in person or over a video conferencing software like Zoom. No interviews were conducted over the phone. All three researchers conducted interviews.

Analysis strategy

Audio recordings of interviews (30 total) were transcribed using an online transcription software, Otter.ai, and transcripts were checked manually for accuracy by the researchers (Liang and Fu, 2020). Transcripts were anonymized and pseudonyms were used for individuals and courses to maintain confidentiality. The transcripts were then qualitatively analyzed using NVivo software, following grounded theory methodology.

Grounded theory analysis is effective in exploring research questions like ours, which are open-ended and exploratory but centered around areas of interest (Auerbach and Silverstein, 2003; Corbin and Strauss, 2014). The inductive coding used in a grounded theory approach allows researchers to identify key ideas/thoughts that emerge from interview data and then group these into themes that are observed across interviews. Grounded theory is useful in settings where limited prior research exists, and our exploration of leadership development in course-based collaborative projects fits into this type of research context. This approach also allows for findings to emerge authentically from the data and reflect what is most important to participants.

Using NVivo, we coded all interview transcripts by identifying recurring topics raised by students regarding facets of group work, such as “communication,” “conflict resolution,” and “workload distribution.” Based on the interviews, the three researchers came to a collective definition for each recurring topic to ensure consistency across interviews during coding (Supplementary Information 2). We then grouped these topics into themes by identifying areas of overlap, and selected the most prominent ones, which are explored below. This approach to data analysis was done to ensure that our interpretation of students’ responses stayed as close to their own ideas as possible.

Results and discussion

In our exploration of how students’ intensive collaborative experiences in classrooms developed their leadership capacities, we found that codes clustered around a handful of common themes:

Attitudes and Intentions: The majority of participants reported positive feelings toward collaboration, either because they reported having had good experiences with group work in the past, or they intentionally sought to develop collaborative skills through selecting courses or pursuing a major that required significant collaborative engagement. Only one participant spoke negatively about their experience with group work in the course in which they were currently enrolled. Interviewees who reported a specific intention to develop their group work skills cited skill development as a meaningful outcome of the project, while those who did not actively seek out collaborative skill development often spoke about only the academic achievements of their group (as opposed to recognizing skill development as one of the outcomes).

Accountability, Boundaries, and Workload Distribution: Participants that reported that their collaboration was successful often cited open communication about workload distribution and the need for creating boundaries in order to protect balance. Interviewees’ discussion of accountability included comments on preemptive and direct interventions when members fell behind on tasks or when group processes fell apart.

Leadership: None of our interviewees addressed the topic of leadership unprompted, but all offered reflections on the relationships between leadership and collaborative group work upon being asked about those connections. Across interviews, interviewees reported a realization that leadership is not always positional in nature. Once asked about leadership, several interviewees made independent connections between skill development in their collaborative group work and applications for co-curricular or other leadership experiences they participate in outside of the classroom.

Emerging from these themes were three key takeaways that seemed most important and relevant to the future of leadership development in collegiate settings: (1) group work increased students’ consciousness of and ability to tend to group dynamics, (2) group work allowed individuals to better balance individual and collective agency within the collaborative process, and (3) many students ended their group projects with a more nuanced definition of leadership.

Takeaway 1: consciousness of and intentional tending to group dynamics

Regardless of the type of collaborative work students engaged in, across most interviews students described how their experiences working with other classmates toward a shared academic goal made them more sensitive to group dynamics. We define “group dynamics” as the evolving interpersonal relationships between and among group members, which allow or disallow for functional collaboration. We observed that many students experienced the meaningful development of interpersonal relationships, strengthened communication within the team, and gained skills for conflict resolution. These developments were often interrelated: through forming and strengthening their interpersonal connections, students were able to efficiently and peacefully navigate conflict, a process which often reciprocally reinforced their communication skills.

Especially when beginning a more intensive group project, students who established a personal familiarity with each other found that collaboration was marked by greater group harmony and efficacy. In the words of one student, “I really like that we had the first couple [of] weeks to just do stuff together. [I]t was also just a really great time for us to bond before we actually had to get into groups together. [It] taught me the importance of just knowing who you are working with.” The shape of this bonding varied from group to group: for some it was built into class, others had pre-existing relationships that extended beyond the group, and others purposefully dedicated time either in or outside of class to form relationships. Regardless of the mechanism, many students came to understand the importance of trusting each other: as one student articulated, “the maintenance of the group and creating the trust, […] is ultimately what led to it being really– a good group.”

In addition to building a foundation of strong relationships with each other as they intentionally tended to the group dynamic, many students came to recognize the necessity of continuous communication for effective collaboration. By communicating to their group members about individual and common expectations for sharing the workload, completing tasks, and generating ideas, students could ensure work was collectively accomplished in a timely, satisfactory, and sustainable manner. Students also mentioned that technology served as an essential facilitator of communication, from video calling sick classmates into class, to coordinating out of class meeting times, to sharing notes from out of class meetings. Being able to work asynchronously was essential to ongoing collaboration, and this increased connection also helped students learn how their group best functioned.

In addition to helping with actual project work, students also felt that clear communication of their expectations for the work to each other helped ensure all group members were coming to the table with a shared understanding of what they each wanted to get out of the project, which in turn strengthened their interpersonal relationships. One student spoke on the importance of taking the time to verbally surface assumptions about how the project would proceed together as a team: “[y]ou have to be intentional about communicating, ‘hey, what does good teamwork look like to us?’ Because […] if you do not set those expectations with each other, how am I supposed to know how someone else feels about this?” Several students articulated a similar newfound recognition of the ways in which intentional communication can improve collaborative engagement.

Many interviewees expressed increased confidence in their ability to prevent conflict between group members. Students reported that working in a group with common goals and expectations provided powerful incentives to be more flexible: “people became a lot more […] willing to compromise to make sure that these experiences of collaborative learning can be positive in the classroom.” Additionally, many students reported that conflict was most effectively prevented by communicating their conflict styles and how the group should ensure accountability for completing their work before the project began. This also ensured that conflict could be resolved quickly and without hurt feelings: “we also were trying to work on the bonds between the group […] to make sure that we were able to express dissent […] so that we would feel safe doing that.” For some students, dissent took the form of disagreeing with ideas for the project; in other cases, it included speaking up about disruptions in the group’s dynamic. Several interviewees spoke to how their group project experience gave them practice voicing those concerns directly. One interviewee discussed learning to “[be] really direct in your communication, and not worrying, like, ‘oh, it’s gonna hurt their feelings if I say they are doing a bad job’.” For several students, working in a group offered experience with both mitigating the emergence of conflict and actively engaging in repair.

Takeaway 2: balancing individual and collective agency

Particularly when students were engaged in longer-term applied group projects, many also demonstrated an increase in both individual and collective agency, as well as a better ability to balance the two. By individual agency, we mean cognizance of personal motivations, strengths, and goals, as well as a willingness to develop and contribute ideas that might help move the project forward. By collective agency, we mean a recognition of the goals of the overall team and willingness to combine and evolve individual ideas and actions into a common effort. Across interviews, participants spoke to their success (or lack thereof) at integrating the two types of agency.

When describing their collaboration, many students discussed feeling a sense of autonomy within the group, highlighting the personal attributes and contributions that impacted their engagement with the collaborative process. Articulating strengths and limitations was a key component of this personal agency; students learned that the more they communicated their own needs and abilities, the more effective the group process could be. For instance, one student noted that “[I got better at] communicating when I need to step back and take a break and […] when I’m not able to do something […] I learned how to prioritize myself a little bit more.” This self-awareness and advocacy not only helped with setting group expectations and establishing trust, but also allowed individuals to strengthen their own autonomy within the group process. Several students also mentioned the value of using individual strengths to make the work more efficient, i.e., dividing up tasks in ways that played to the skills that group members brought with them into the project. Whether it was utilizing unique strengths or setting boundaries and requesting support from teammates, being able to articulate and honor group member’s individual experiences made the group process more effective and enjoyable for many interviewees.

Recognizing the value of their individual ideas also helped students increase their confidence in themselves and the collaborative process. Several students shared that they valued the diversity of thought that comes from cultivating individual opinions before bringing them to the group. One student reflected on the reality that if a group member is not given space and encouragement to engage in independent thinking, “you might lose the courage to say no or show disagreement.” Another student similarly concluded, “I think there’s also a lot of merits to sitting alone and being like, ‘okay, what do I actually think here?’ […] You can only have a discussion when you are solid in your own footing.” Through working with a group, many students felt empowered to hold and share their own ideas and opinions, which introduced a greater range of potential possibilities for the group to pursue, making their deliverable more effective.

While collaborative group projects helped students develop more individual agency, just as importantly, teams also developed collective agency through designing and carrying out shared processes and integrating their diverse ideas, perspectives, and skills toward a common end goal. Many students mentioned how a team created outcomes that were greater than the sum of their parts, noting, for instance, “I would never have been able to get this far by myself in this project” and “… knowing that you are never really alone in the group work, it’s contributing to something bigger.” Several students discussed how having a common goal helped the team develop a shared identity. Individual members’ growth in their community-building and relational skills helped teams develop shared agency that went beyond individual contributions.

For many of our interviewees, the team’s success hinged on their ability to recognize and draw on individual strengths while also actively combining ideas and efforts. One student described this process with a metaphor that captures this finding beautifully: the student likened collaboration to the endeavor of baking a cake, describing how team members come in with different ingredients, which they figure out together how to mix, and in what order. When team challenges arise, such as “an eggshell in the batter,” team members bring different tools and ideas to problem-solving, and the team works collectively to determine what works best. The student concludes this metaphor by saying, “we all want the cake at the end,” which highlights the shared product and learning that emerges by integrating the group’s individual and collective work.

Takeaway 3: redefining leadership

A third key finding, which emerged especially strongly (but not exclusively) among students who completed a long-term applied group project, was a marked reimagining of the concept of “leadership.” This was striking because in most cases, collaborative projects and assignments were not presented as “leadership development.” However, when asked about leadership in the interviews, students unearthed interesting alternative ways of thinking about the term that came out of their collaborative experiences in the classroom. Between the first and second interviews, many students’ definitions of leadership evolved to become more nuanced and, in many cases, less hierarchical. One interviewee, for example, expressed in their first interview an intention to practice power-sharing: “[leadership is] the ability to navigate a project in a way that encourages collaboration, communication, honesty and vulnerability, without taking over.” The same student, in their second interview, discussed how rewarding it was to engage with that practice during their project: “I think it’s really rewarding to [get] to a point where your team feels welcomed and also where [the group] trust each other and are honest and it’s been a challenging process, but also rewarding.” In several cases, the collaborative nature of these projects specifically liberated students from top-down leadership paradigms. When asked about past experiences of leadership, one student said: “In the past, […] I had to be the primary organizing person and the pick-up-whatever-slack-that-there-was-in-the-group. I did not feel that way [in this project].” When they found themselves working within the context of a dedicated and communicative team, several interviewees experienced a sense of relief in not feeling the need to lead the group from a position of authority; instead they could engage with others in mutual give-and-take as they carried out their project.

Under their newly expanded definitions of leadership, many students voiced an increased sense of personal power and confidence: “[T]his class has instilled in me more than anything, […] a sense of confidence in my own ability to lead and collaborate with other folks.” In addition to a general sense of belonging, students also reflected on specific aspects of their identity which they could now embrace under the new leadership definition: “it’s really cool to know that I can not be a cis-, straight, white man, and actually be something in terms of leadership.” Especially for those students who self-identified as marginalized along the lines of gender, race, class, and other identities, the definition of leadership expanded through collaboration to include those who otherwise would struggle to see themselves represented in traditional, hierarchical conceptualizations of leadership.

Significantly, a handful of interviewees who reported on their evolving definitions of leadership also spoke directly to how they were translating those new definitions across contexts. For instance, one student who also served as the President of their House Council (a leadership organization for Smith dorms) described their new approach to House Presidency: “[C]all it leadership from behind or leadership from within. But […] you can be part of the group, and still be a leader, without being above other people.” This ability to apply newfound skills across contexts indicates that these collaborative skills and sensitivity to group dynamics are not domain-specific.

Implications for educators

Our research illuminates the degree to which students are encountering meaningful “small-l” leadership development experiences within their academic work across the liberal arts disciplines in the form of applied group projects that serve as underappreciated laboratories for collaborative leadership skill building. There are scholarly articles as well as practical handbooks (Barkley et al., 2014; Colbeck et al., 2000; Doren, 2017) that speak to ways instructors in higher education classrooms can design more effective group projects to build collaborative skills, as well as formal leadership development program models (Komives and Wagner, 2016) that highlight collaboration as one of many important leadership skills. Our research allows us to begin to draw connections across these two conversations to make it clear to faculty across liberal arts disciplines the degree to which inclusion of collaborative learning experiences in their teaching, especially in the form of longer-term applied group projects, can expand students’ “small-l” leadership capacities and provide them with a more expansive understanding of their own collaborative efficacy. This will also enhance these learning experiences are an alternative to “Big-L” leadership models, which emphasize individual talents and achievements and assume that the ultimate purpose of leadership training is to prepare individuals to adopt formal leadership roles. As described above, “small-l” approaches instead position leadership as a practice rather than a role, shed light on the relational, contextual, and power-embedded realities of collaborative change work, and highlight the impossibility of effectively tackling complex problems alone. For some students, reframing leadership as a collaborative practice brings a great deal of relief and comfort, providing a model that reinforces their sense of efficacy without the pressure of pursuing high-profile roles and positions, or tending to their own individual achievements over those of a group or community. And for those students seeking to practice “Big-L” leadership, the collaborative skills gained within these learning experiences are clearly transferable and may even lead to a reframing of how an individual should behave when wielding the power that accompanies a formal leadership role.

Metacognition and group dynamics

Across our interviews, many students engaged in metacognition about their group’s dynamic, either because they were assigned to do so by their instructor or simply because immersion within a group required them to pause and consider the complexities of collaborating with their team. By metacognition, we mean thinking about one’s own thinking or (in the case of group work) observing, thinking about, and/or discussing a group’s dynamic. We witnessed several students draw direct connections between the efforts they made to build, manage, and maintain relationships and the overall problem-solving efficacy of their groups. This resulted in more intentional tending to group processes and relationships. Students reflected on how they managed their group’s way through Tuckman’s Model of Group Development (with stages of forming, storming, norming, and performing), without having the consciousness they were doing so (Tuckman, 1965). Reflecting back on the project in their second interviews, several interviewees commented on how impossible the project would have been had they attempted to achieve it alone, and cited active relationship building as central to both their successful outcomes and their overall positive experience working on the project. By tending to active communication and articulating their needs and work styles within a team, students began to surface areas of difference and generate group norms that could later be called on as tools for arbitrating conflict.

Research suggests that in group settings, people with marginalized social identities, as compared to people with privileged social identities, tend to speak up less frequently, and are more frequently challenged or interrupted when they do (Eagly and Carli, 2007). This emerged in our interviews, as well: one student reflected that “we have been so ingrained as femme-identified people to not bring up our anxieties, to try to be as little of a problem to other folks as we can.” For students of color in particular, group projects can be painful experiences due to the fact that they are often excluded or isolated within groups (particularly when they are the only member from their racial or ethnic background) (Tichavakunda, 2021). By learning to set and adhere to group norms around communication within their project teams, students took an important first step toward reversing these trends through actively negotiating how they would be inclusive of all voices and honor the various needs of group members. Consequently, many of them became better able to metabolize conflict within the team, working through interpersonal tensions with a level of care established from the start and welcoming healthy dissent around ideas for how to carry the project forward. Given the high levels of polarization and conflict aversion on our campuses and in society at large, fostering healthy disagreement and dissent within the relatively safe context of a group project can go a long way toward teaching students to embrace intellectual and cultural differences and practice civil discourse (Magee, 2024; Capineri, 2024). In general, collaborative group projects that offer students opportunities to engage in metacognition about their own behaviors, the value of group diversity, and their team’s dynamic equip them with the agency to build healthy relationships and collaborate well toward common impact-oriented goals (Lin et al., 2022).

Balancing individual and group agency

Among the most important areas of “small-l” leadership learning for our interviewees was their demonstrably increased ability to navigate the tensions between individual autonomy and agency and the needs of the larger group. Striking this balance can be especially challenging for students, many of whom reported previous group project experiences in which they “had to be the primary organizing person” and felt solely responsible to “pick up whatever slack there was in the group.” Tensions emerged within groups around task functions, such as making decisions about how to divide work or choosing which ideas to move forward and which to discard. Tensions also arose around group maintenance functions, such as creating space for individual group members to take breaks as necessary. While some students’ teams managed these tensions by adopting a full “divide-and-conquer” approach, others spoke extensively about how they learned through the project to find their way back and forth between leveraging the skills of individuals and dividing tasks during some phases of the work and joining forces to actively combine ideas and co-create solutions in other phases. For students who took the latter approach, there was a clear recognition of the value of authentic integration, most frequently articulated as an observation that the team’s results were much greater than the sum of its parts. These revelations suggest that within the context of an applied group project, students are developing what professional facilitator Ewen LeBorgne calls “process literacy”: an ability to design group processes intentionally to allow for individuals to have their needs met and ideas valued while also maximizing the ability of the group to combine efforts and harness its collective brilliance to achieve common goals (Hadnes and Le Borgne, 2021). This capacity to design and lead group process is a leadership skill that is increasingly necessary for students to develop before launching into a world that will require them to be able to work across disciplines and draw together diverse thinkers to tackle increasingly complex social and ecological problems (Sawyer, 2006). As far as we know, this skill generally remains unaddressed in the literature on both leadership development and collaborative pedagogy, yet to recognize its importance and develop it in students helps emphasize the relational nature of collaborative leadership work.

Redefining of leadership

Students with marginalized social identities are frequently skeptical of formal leadership training because they are aware that their identities are excluded from the traditional definition of “leader,” and they are keenly aware of how taxing “Big-L” leadership positions can be with the added layers of racism, classism, sexism, etc. that they might experience. For international students attending an American college or university, the gap between “Big-L” leadership and the cultural models they hold might also be large, as many of the “small-l” mindsets are often central to leadership models in cultures outside of the United States (Liu, 2010). When given the chance to develop and practice leadership skills in the context of a collaborative group project, however, many of these students with marginalized gender, race, class, and sexual identities regarded themselves as leaders and embraced “small-l” approaches to making change. By broadening the boundaries around what it means to practice leadership, collaborative projects in disciplinary courses across the liberal arts effectively diversify the pool of individuals who are interested in exploring the impact they can have on the world through collective action. Our research offers direct evidence that for some students who do take on a “Big-L” leadership role following a group project, the experience can reframe their understanding of the work of formal leadership and equip them with skills and tools to carry out their role in inclusive and collaborative ways. Moreover, these experiences, as projects embedded within academic coursework, are more accessible to college students who frequently need to balance work, school, and often family obligations and who might not have the time to participate in co-curricular programming. The fact that these projects are both applied and directly connected to a student’s developing mastery of a disciplinary field further reinforces the power of the learning; rather than exploring leadership theory divorced from context-embedded practice, or participating in co-curricular skill building workshops separated from academic learning, students participating in these projects gain direct and meaningful practice with the very real-world work of navigating complex group dynamics in order to galvanize a diverse group of people to achieve a common goal.

Supporting “small-l” leadership learning

Our research shows that students developed new leadership skills across many different types of collaborative learning experiences in the classroom, whether their course included only informal collaborative discussion groups or engaged them in more intensive and longer-term applied group projects. However, we found that interviewees varied in their level of consciousness about the skills they were learning, especially as these skills applied to leadership. In reflecting on what contributed to their group’s success (or lack thereof), many students engaged in what might be described as “magical thinking”: they suggested that they were just “lucky” to have had a positive group experience, or they attributed their success to having been grouped together with inherently likable people. We found that these attitudes emerged far more frequently in classes in which the collaborative element in the class was less formal (such as small discussion groups), or in which the instructor included little to no scaffolding within the structure of the project for students to reflect on their collaborative engagement and team dynamics. One student, for example, suggested that when they are in groups in which everyone naturally agrees, “it works. And when people are dissonant, no matter which way they think, it does not. I think there’s just not a lot of structure provided by the faculty.” In classes where the instructor provided more of these kinds of metacognitive and collaborative support structures, students articulated a much clearer understanding of the specific actions necessary for group members to be able to lead toward smooth processes and team coherence. One interviewee reflected on a lack of scaffolding as a missed opportunity: “We’re doing the work of the class, but it’s not intentional enough to further develop those group work skills.”

Clearly, course instructors can significantly enhance student leadership development by scaffolding reflective and connective exercises into the design of collaborative learning, particularly in the form of an applied group project assignment. Indeed, Carol L. Colbeck et al. found that collaborative group projects correlate to enhanced learning, but only if they are accompanied by “instruction about interpersonal skills, encouraging positive interdependence among students, making individual goal achievement dependent upon attainment of group goals, and encouraging students to reflect on the group process” (Colbeck et al., 2000). As Mariah Doren writes on the topic of assigning group work in the college classroom, “When we take for granted that [students] will simply ‘figure it out,’ we allow all the dynamics of privilege and authority at play in the larger society to simply be replicated on a smaller scale” (Doren, 2017). Renee Monson found that negative experiences within a group can detrimentally affect students’ learning outcomes; she recommends instructor interventions including “attending to group size, exercising oversight on the research topic, and building in deterrents for free-riding and problematic leadership dynamics” as forms of prevention (Monson, 2019). By offering structured team development experiences throughout the semester or through the duration of a project, instructors can ensure that all students gain practice in creating and facilitating inclusive and equitable collaborative change processes.

Our research illuminated six pedagogical strategies that, when employed within the structure of a well-designed collaborative project, can have a significant impact on “small-l” leadership learning for students. These include pedagogical strategies employed by the instructors of the courses being taken by our interviewees, as well as strategies that are frequently recommended in the literature on collaborative teaching and learning techniques.

1. Short and Frequent Self-Assessments: At multiple stages throughout the life of the group, ask students to engage in a 5–10 min reflection on what they are noticing about themselves as collaborators and what the dynamic is within the group. This might take the form of each student creating a “User Manual for Working With Me” at the start of a project, or quick Google forms with 3–5 reflection questions assigned as homework. Questions can be the same each time to document change over time in a student’s answers, or varied in order to capture reflections on different stages in the life of the project. These self-assessments can serve as powerful metacognitive tools that enhance student awareness of their own behaviors and those of the group.

2. Team Contracts: At the start of a project, engage teams in conversations about what they explicitly expect from one another in terms of collaborative behaviors and group culture. Make the first assignment of the project be a team contract that lays out no more than 5–6 specific agreements all members will adhere to (more than 5–6 can be challenging to remember and follow). Agreements should be short, specific, and action-oriented (rather than vague principles). Teams should also discuss what they will do if group members break the contract.

3. Rotating Project Lead Role: Particularly for semester- or year-long group projects, rotating a formal Project Lead role among all of the members of the group can offer students an opportunity to step in and out of designing and directing the group’s process and managing the team’s relationships. Students who engage in this experience often gain new appreciation for the potential for exercising “leadership” whether or not one is in a formal directing role.

4. Culture Building/Bonding Exercises: Build in opportunities for students to get to know each other as people, beyond the confines of your class and their project tasks. This might take the form of five-minute ice breakers at the start of each team work session, or it could be an assignment for the team to meet outside of class and do something fun together, with the only rule being that they can discuss anything but the class and the project.

5. Team “Storming” Prompts: Create space for and scaffold direct conversations within project teams about tricky team dynamics or areas of disagreement or conflict. Ask students to write down answers to questions such as “I wish our team process was more ____ and less ______,” and then foster discussion about what they wrote down and why. Have students complete the United States Institute for Peace’s “Conflict Styles Assessment” and discuss their results in connection to their team’s dynamic (United States Institute of Peace, 2024). For other prompts on group dynamics, the Wurtele Center created a Collaborative Leadership Project Deck as a classroom resource (Supplementary Information 3).

6. Structured Peer-to-Peer Feedback: After building trust within a team, give students a structured opportunity to deliver feedback to their peers. Discuss the practice of giving and receiving feedback, including perhaps games or exercises illustrating the importance of both negative and positive feedback (Dieckman et al., 2022). Frame feedback not as critique but rather as a chance to uncover assumptions or unconscious behaviors that negatively impact the group, and understand how they might engage differently as a collaborator for the remainder of the project and beyond. Ask students to draft their feedback in written form and share with the instructor for coaching and revision before the team delivers it in person. (Note that this approach is both time-intensive and requires a good deal of engagement on the part of the instructor to ensure that students practice respectful and mutually helpful feedback exchange. An alternative approach is to provide students with a chance to submit feedback for their teammates which the instructor then synthesizes and delivers to each individual student as an aggregate).

Limitations

We recognize that, given the size of our study and the unique qualities of the institution in which it was carried out, our research cannot present a comprehensive picture of the ways in which undergraduate students encounter collaborative learning experiences in the classroom. Smith College is not representative of all American institutions of higher education or even all small liberal arts colleges. As a women’s college with an undergraduate enrollment of roughly 2,500, Smith’s student body largely identifies as female, with a significant population of gender-nonconforming students. This demographic context might have contributed to students’ development of such strong small-l leadership skills, and outcomes at co-ed colleges and larger universities very likely would vary. This is an avenue for further exploration in future studies.

Additionally, our study was conducted on a relatively small sample of students and academic courses at Smith. While we were able to interview students who completed courses in all four academic divisions (humanities, social science, natural sciences, and interdisciplinary studies), as well as courses of various levels of difficulty (ranging from the 100- to the 400-level), there are a number of academic paths within Smith we did not investigate. Further, our sample wasn’t truly representative of the variety of experiences students might have had with collaboration. We found that students who volunteered for our study tended to be enthusiastic collaborators, and had overwhelmingly positive attitudes toward group work. Thus we did not completely capture the scope of students’ collaborative experiences, as there is a known correlation between the “grouphate” phenomenon and how smoothly a project is progressing (Goodboy, 2005). We encourage any further exploration to include a more representative sample of the student population.

Conclusion

This study of leadership development in liberal arts colleges has identified intensive collaborative projects as spaces for relational, contextual, and power-embedded leadership development, which we have termed “small-l” leadership. Students’ awareness of group dynamics and personal and group agency, as well as their redefinition of leadership together contribute to a more harmonious and rewarding collaborative and leadership experience. We also identified a relationship between students’ consciousness of their collaborative experience, the efficacy of their team, and the amount of pedagogical scaffolding provided by course instructors. Our work illuminates the highly impactful leadership learning happening in educational spaces that are not explicitly framed as “leadership development,” yet nonetheless equip students with a strengthened ability to collaborate as scholars within a given discipline, as well as a deepened sense of themselves as collaborative leaders with the ability to make an impact alongside others. We also address the implications of these findings for educators and offer specific strategies to support “small-l” leadership development in the classroom.

We believe our findings address essential questions about where leadership development might be happening within the larger educational landscape of our institutions, what leadership skills and models students are learning (consciously or unconsciously) during their time in college, and what role instructors might play in scaffolding that instruction when it is happening in the context of embedded, applied group projects in liberal arts classrooms. Disciplinarily-focused pedagogies often prioritize what it means to teach the discipline well, but might miss the ways in which students gain important skills for working effectively with others to apply their knowledge toward collaborative interdisciplinary problem-solving. Very few academic departments at liberal arts colleges integrate leadership learning into their curriculum; the STEM Teaching and Research (STAR) Program at Austin College offers a rare example of what it might look like to intentionally scaffold leadership learning around interpersonal communication, problem solving, collaborative work, foresight and planning, and moral consciousness directly into the curriculum in STEM fields (Reed et al., 2016). Another example is the “Being Human in STEM” Initiative at Amherst College, which integrates pedagogical practices geared toward collaborative leadership and community building in STEM courses (Burnell et al., 2023). We hope this work contributes to institutions of higher education investing greater attention toward leadership development for their students not only in STEM fields but across the curriculum, to consider the liberal arts classroom as an underutilized space with great potential for doing that work.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Smith College Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the Smith students who participated in this study, and the professors who assisted us in contacting them. Additionally, Caroline Melly, Sam Intrator, Susannah Howe, Patricia DiBartolo, and Fraser Stables for their feedback on this publication. We would also like to thank everyone who supported us throughout this process, including the Wurtele Center, and especially Margaret Wurtele.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1480929/full#supplementary-material

References

Arminio, J. L., Carter, S., Jones, S. E., Kruger, K., Lucas, N., Washington, J., et al. (2000). Leadership experiences of students of color. NASPA J. 37, 496–510. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.1112

Auerbach, C. F., and Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis (pp. ix, 202). New York, NY, US: New York University Press.

Barkley, E., Major, C., and Cross, P. (2014). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty (2nd ed.). Wiley. Available at: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Collaborative+Learning+Techniques%3A+A+Handbook+for+College+Faculty%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9781118761557 (Accessed April 22, 2024).

Belkin, D. (2024). Essay | Why Americans have lost faith in the value of college. WSJ. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/us-news/education/why-americans-have-lost-faith-in-the-value-of-college-b6b635f2 (Accessed February 29, 2024).

Biswas, S. (2019). Stop trying to cultivate student leaders. The chronicle of higher education. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/stop-trying-to-cultivate-student-leaders/ (Accessed February 29, 2024).

Burnell, S., Jaswal, S., and Lyster, M. (2023). Being human in STEM: Partnering with students to shape inclusive practices and communities (1st ed.). Routledge. Available at: https://www.routledge.com/Being-Human-in-STEM-Partnering-with-Students-to-Shape-Inclusive-Practices-and-Communities/Bunnell-Jaswal-Lyster/p/book/9781642672299 (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Capineri, C. F. (2024). The group project’s potential: Emphasizing collaborative writing with community engagement – reflections. Available at: https://reflectionsjournal.net/2024/06/the-group-projects-potential-emphasizing-collaborative-writing-with-community-engagement/ (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Colbeck, C. L., Campbell, S. E., and Bjorklund, S. A. (2000). Grouping in the dark: what college students learn from group projects. J. High. Educ. 71, 60–83. doi: 10.2307/2649282

Collinson, D., and Tourish, D. (2015). Teaching leadership critically: New directions for leadership pedagogy. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 14, 576–594. doi: 10.5465/amle.2014.0079

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications, Inc. Available at: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/basics-of-qualitative-research/book235578 (Accessed February 29, 2024).

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., and Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 19251–19257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Dieckman, A., Nelson, E., Luechtefeld, R., and Giles, G. (2022). The good game: Developing feedback through action learning. InSight 17, 99–124. doi: 10.46504/17202206di

Domingue, A. D. (2015). “Our leaders are just we Ourself”: black women college student leaders’ experiences with oppression and sources of nourishment on a predominantly white college campus. Equity Excell. Educ. 48, 454–472. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2015.1056713

Dugan, J. P., and Leonette, H. (2021). The complicit omission: Leadership development’s radical silence on equity. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 62, 379–382. doi: 10.1353/csd.2021.0030

Eagly, A. H., and Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders (pp. xii, 308). Boston, MA, US: Harvard Business School Press. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-01900-000

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Glotfelter, A., Martin, C., Olejnik, M., Updike, A., and Wardle, E. (2022). Changing conceptions, changing practices: Innovating teaching across disciplines. University Press of Colorado. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv335kw99 (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Goodboy, A. (2005). A study of Grouphate in a course on small group communication. Psychol. Rep. 97, 381–386. doi: 10.2466/PR0.97.6.381-386

Grobman, L., and Ramsey, E. M. (2020). Major decisions: College, career, and the case for the humanities. University of Pennsylvania Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv16t6dzr (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Hadnes, M., and Le Borgne, E. (2021). Process literacy: The new collaborative team skill with Ewen Le Borgne. Workshops Work. Available at: https://workshops.work/podcast/116/ (Accessed March 4, 2024).

Haslam, S. A., and Reicher, S. D. (2016). Rethinking the psychology of leadership: From personal identity to social identity. Daedalus 145, 21–34. doi: 10.1162/DAED_a_00394

International Leadership Association. (n.d.). Leadership education program directory [Dataset]. Available at: https://ilaglobalnetwork.org/program-directory/?pmp_degree_type=Bachelors (Accessed February 29, 2024).

Kellerman, B. (2012). The end of leadership. HarperBusiness. Available at: https://www.harpercollins.com/products/the-end-of-leadership-barbara-kellerman (Accessed February 29, 2024).

Komives, S., and Wagner, W. (Eds.) (with National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs). (2016). Leadership for a better world: Understanding the social change model of leadership development, 2nd Edition | Wiley (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. Available at: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Leadership+for+a+Better+World%3A+Understanding+the+Social+Change+Model+of+Leadership+Development%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9781119207597 (Accessed April 22, 2024).

Liang, S., and Fu, Y. (2020). Otter.ai [Computer software]. Available at: https://otter.ai. (Accessed January 1, 2021).

Lin, M.-H., Nariswari, A., Zhang, C., and Lundvall, E. (2022). Leveraging group diversity to improve student learning. J. Finan. Educ. 48, 1–10.

Liu, H. (2017). Reimagining ethical leadership as a relational, contextual and political practice. Leadership 13, 343–367. doi: 10.1177/1742715015593414

Magee, M. (2024). Advice | How to reduce cultural conflict on campus. The chronicle of higher education. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-reduce-cultural-conflict-on-campus (Accessed March 4, 2024).

McKinney, K. (2017). The integration of the scholarship of teaching and learning into the discipline of sociology. Teach. Sociol. doi: 10.1177/0092055X17735155

Monson, R. A. (2019). Do they have to like it to learn from It? Students’ experiences, group dynamics, and learning outcomes in group research projects. Teach. Sociol. 47, 116–134. doi: 10.1177/0092055X18812549

Ospina, S., and Uhl-Bien, M. (2012). “Mapping the terrain: Convergence and divergence around relational leadership,” in Advancing relational research: A dialogue among perspectives. Information Age Publishing. Available at: https://www.infoagepub.com/products/Advancing-Relational-Leadership-Research (Accessed February 29, 2024).

Reed, K. E., Aiello, D. P., Barton, L. F., Gould, S. L., McCain, K. S., and Richardson, J. M. (2016). Integrating leadership development throughout the undergraduate science curriculum. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 45, 51–59. doi: 10.2505/4/jcst16_045_05_51

Sawyer, R. K. (2006). Educating for innovation. Think. Skills Creat. 1, 41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2005.08.001

Tichavakunda, A. A. (2021). “Informal relationships: the (im)possibility of peer collaboration” in Black campus life (State University of New York Press), 135–164.

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol. Bull. 63, 384–399. doi: 10.1037/h0022100

United States Institute of Peace. (2024). Conflict styles assessment. United States Institute of Peace. Available at: https://www.usip.org/public-education-new/conflict-styles-assessment (Accessed April 16, 2024).

Keywords: collaboration, leadership, liberal arts, undergraduate, higher education pedagogy, leadership development

Citation: Almazovaite M, Cohn EP and Kumar S (2024) Group projects as spaces for leadership development in the liberal arts classroom: a case of American undergraduate students. Front. Educ. 9:1480929. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1480929

Edited by:

Joana Carneiro Pinto, Catholic University of Portugal, PortugalReviewed by:

Maria Tsvere, Chinhoyi University of Technology, ZimbabweMargarida Piteira, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Almazovaite, Cohn and Kumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erin Park Cohn, ZWNvaG5Ac21pdGguZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Marta Almazovaite

Marta Almazovaite Erin Park Cohn

Erin Park Cohn Sirohi Kumar

Sirohi Kumar