- 1Cambridge Centre for Sport and Exercise Sciences, School of Psychology, Sport and Sensory Science, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

- 3Institute of Health and Wellbeing, Federation University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Introduction: Entering higher education (HE) is one of the most significant transitions in a student’s life and is negatively impacted by any disparity between expectation and initial experience when joining their course.

Method: The current study explored how the students’ experiences of learning and teaching practices in their previous educational environment influenced their expectations and initial experiences of HE. The study adopted a mixed methods approach, initially surveying 69 students concerning their previous educational experiences, expectations and experiences of HE. Informed by the questions in the survey, two semi-structured focus groups comprising a total of 6 students were completed and analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results and discussion: The current research identified specific challenges students face as they transition into HE, often resulting in an initial culture shock as that adapt to their new learning environment. These challenges are, to some extent, a consequence of their previous learning environment. Whilst expectations of HE were cultivated in their previous educational environment, they were not always accurate and resulted in a mismatch between expectation and reality of HE. This article identifies what may be missing for a student as they transition from further education into HE, and explores some of the opportunities HE faces in addressing these deficits.

1 Introduction

Higher Education (HE) across England (United Kingdom) has been set long-term expectations to ensure students are ‘supported to access, succeed in, and progress from higher education’ (OfS, 2022). Whilst the English HE sector has a positive record on student progression, relative to international comparators, the persistence of non-completion suggests that this remains a prevalent issue within the UK (Hillman, 2021). Transitioning into HE marks one of the most significant transitions in a student’s life (Beasley and Pearson, 1999); students are required to develop new academic skills, whilst simultaneously acquiring new social skills and adapting to their role as an independent learner in a cultural setting different to what they may know.

Successfully transitioning into HE increases students’ chances of success (i.e., reducing the likelihood of dropout, Wilcox et al., 2005). Theoretical models provide a framework with which to conceptualize student transition. Tinto (1975) model of social integration recognises the importance of students integrating into social and then academic systems within an institution. The model proposes that successful integration enhances students’ commitment, positively influencing their intended persistence in their studies and their eventual academic outcome (Fincham et al., 2021). Whilst a student’s initial commitment is continually modified by their interactions with social and HE institution’s academic systems (Fincham et al., 2021), students who demonstrate delayed or minimal commitment at the outset, limit their integration and subsequently increase their risk of non-continuation (Hadjar et al., 2022). One approach to mitigate delayed commitment is highlighted through Nicholson (1990) cyclical transition model, where students prepare (preparation) to enter HE, achieving a state of readiness through developing precise and realistic expectations of the environment they are about to enter (De Clercq et al., 2018). Lizzio (2006) proposes a more encompassing approach, with five ‘senses of success’ (capability, connectedness, purpose, resourcefulness and academic culture), each of which are essential to students’ transition into HE (Larsen et al., 2020). Whilst Lizzio (2006) contends that there is commonality in students’ needs as they enter university, he takes a pragmatic stance to student transition, suggesting a ‘one size fits all’ approach is not feasible, and with no guarantees for a positive impact on a positive student outcome.

More recent models provide an additional lens to consider student transition. Risquez et al. (2008) presented the U-Curve Theory of Adjustment, which recognises the initial negotiation of unrealistic expectations as a period of ‘culture shock’, characterized by feelings of disillusionment and dejection, as students potentially face adjustment to the changes in their environment (location and culture shock), social life (meeting new people, sharing accommodation, interacting with academic staff) and academic/learning environment (Denovan and Macaskill, 2013; Gu et al., 2010; Thurber and Walton, 2012; Wrench et al., 2013). Burnett’s student experience model (2007) presents student transition from much earlier in a student’s life, framing the first of 6 phases ‘pre-transition’ from aged 13–17 years old (school years 9–12 in England). It is during the pre-transition phase that students begin to consider studying in HE and make decisions based on career planning, knowledge and familiarity of courses, university culture, family and work commitments and financial factors (QAA, 2023). It is in the period between having a firm offer of a university place and starting welcome/orientation week where students enter the second phase of ‘transition or preparing for HE’ and commonly encounter mixed feelings of excitement and fear (Burnett, 2007).

Previous research conducted by Timmis et al. (2022) investigated student transition into HE through utilising second and third-year undergraduate students’ perspectives. Students wrote a letter to their younger self, providing guidance on how to successfully transition into HE. One of the six themes identified from analysing the letters highlighted the need for students to ‘Beware of unrealistic expectations’ and the value of gathering appropriate information to facilitate imagining/planning realistic expectations for university life. The gap between student expectation and experience when joining their course is common (Holmegaard et al., 2014) and complex, with many contributing factors (Tett et al., 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2023). This is influenced by individual characteristics (e.g., family background, personal attributes, previous academic performance and family encouragement, e.g., Tinto, 1975); personal attributes including being an independent, self-regulated learner (Hockings et al., 2018; Jonker et al., 2011; Pather and Dorasamy, 2018; Rowley et al., 2008), a collaborative, critical thinker able to communicate in large audiences (e.g., Hayman et al., 2017; Hayman, 2018; Hockings et al., 2018; McMillan, 2013); course characteristics (Timmis et al., 2022) and degree level expectations (Farhat et al., 2017; Lowe and Cook, 2003); teaching practices (Money et al., 2017); personal circumstances including cost associated with the degree (e.g., travel from home to place of study) and time requirements around commuting to university (Timmis et al., 2022; Holmegaard et al., 2014; Yorke and Longden, 2008).

In recent months, across England there has been a much stronger political narrative surrounding the value (benefit) of HE degrees, with the OfS threatening to impose sanctions on universities that are failing to deliver ‘good’ outcomes for students (DfE, 2023). Outcomes are being partly regulated through the number of students who initially enrol on a course and complete their studies (continuation and completion) and progress into a highly skilled job or further study 15 months after graduating [progression; condition B3, OfS (2023)]. Whilst student retention has long been identified as a concern in HE (Wilson et al., 2016), the subject area of Sport and Exercise Sciences is particularly poor, having recently been ranked second lowest across 34 subjects in terms of students projected to obtain a degree (OfS, 2022) and is an area of continued concern for those involved in sport and exercise sciences education.

To better understand the link between the risk to non-continuation (drop out) when transitioning into HE and students’ unrealistic expectations, it is necessary to investigate the learning and teaching experiences of first year sport degree students who had recently enrolled in HE and compare these experiences with how they were taught at their previous educational establishment, further education. Literature has shown that students self-report differences between teaching and learning experiences in further education compared to HE (e.g., Cook and Leckey, 1999; Lowe and Cook, 2003) and the study habits students formed in further education persist to the end of the first semester of university (Cook and Leckey, 1999). However, aforementioned research focused on students’ self-reported difference and did not seek to understand the experiences of students as they transition into HE, or negotiate any unrealistic expectations. If students’ capabilities to navigate change and transition into HE are to be fully understood and resourced, it is necessary for research to foreground students’ lived realities (Gale and Parker, 2014) and increase the current understanding by considering students’ own perspective (Maunder et al., 2013).

Through using both survey and focus groups, the current project investigated how the students’ previous education experience impacts student expectation and initial experience of transitioning into HE.

2 Method

2.1 Organizational context

This study was undertaken at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), an English HE provider which traces its origins to the Cambridge School of Art, founded in 1858, and granted university status in 1992. ARU’s passion for widening access to, and participation in, HE, recognises education for all and is an enabler of positive transformational change for both individuals and wider society, realized in the institution’s mission;

“Transforming lives through innovative, inclusive and entrepreneurial education and research.”

ARU’s student body is best characterized by its diversity, attracting students from groups that are underrepresented in HE. 30.2% of our students fall into quintile 1 of at least one of the Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), Tracking Underrepresentation by Area (TUNDRA) and Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) measures. We attract considerably more mature (57.1% aged 21+), minority ethnic (36.0%), female (62.9%), and local (36.5%) students than the respective sector averages (29.9% aged 21+, 29.0% minority ethnic, 56.1% female, 21.8% local). 34.7% of our students have an Access/Foundation/‘other Level 3’ course as their entry qualification (sector average, 17.0%), and 16.7% of our students have ‘other’ entry qualifications – typically mature learners admitted on the basis of their prior and experiential learning (sector average, 8.1%).

ARU has offered sport degree courses since 2000. Initially offering a degree in Sport and Exercise Science, the discipline has grown to meet industry demands and provides a pathway for academic study across 4 undergraduate and 1 postgraduate degree programmes.

2.2 Participants

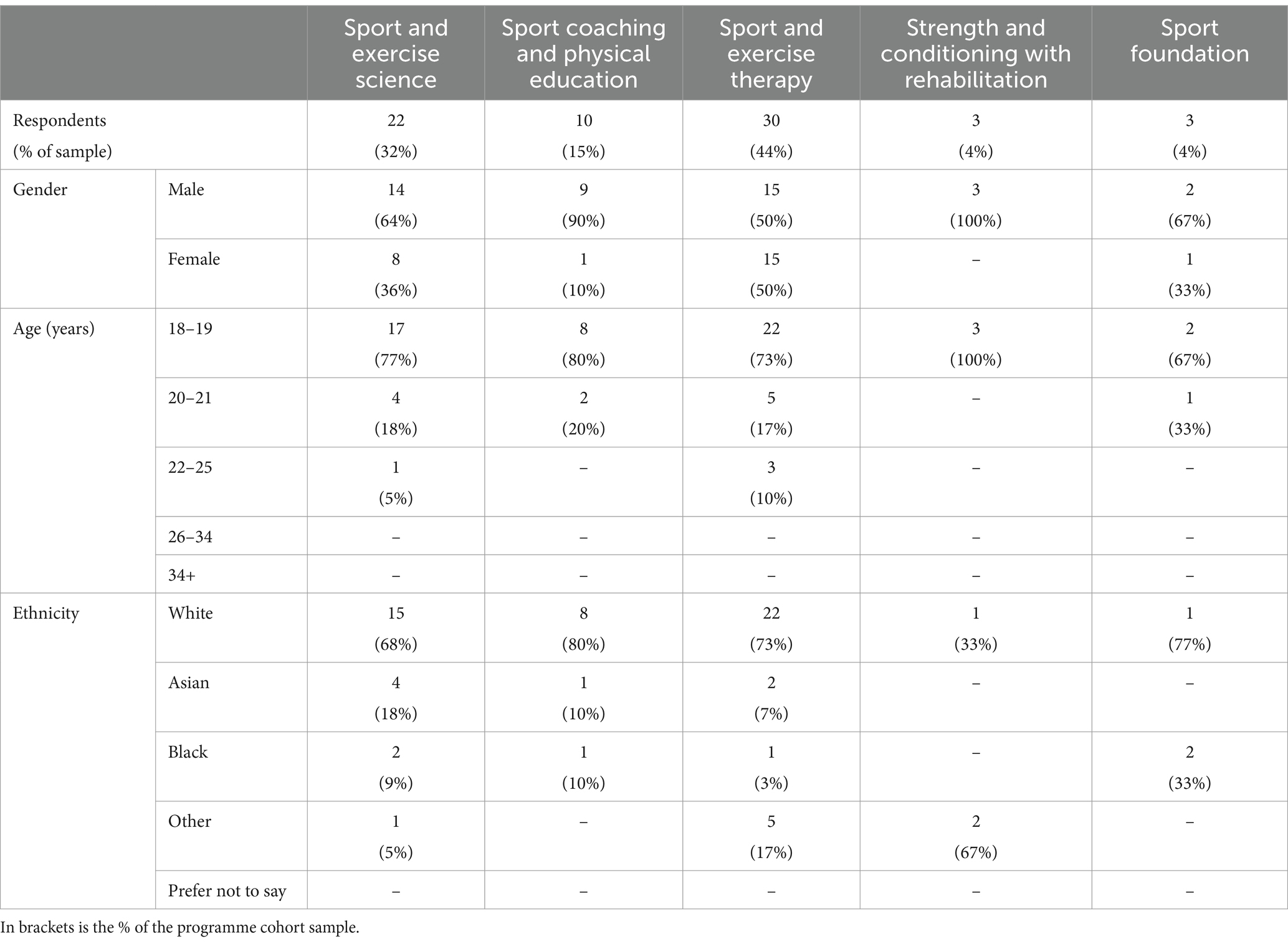

The total sample which completed the survey comprised 69 out of 92 eligible participants (75% completion rate), of which 64% were male and 36% were female (0% identified as other/nonbinary). Most participants were aged 18 or 19 years (77%), Caucasian (70%), classed as ‘home’ students (93%) and studied either A-Levels (33%) or Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC) courses (36%), at sixth form (59%) or college (32%) full-time (97%). BTEC courses and A-Levels are widely recognized level 3 qualifications that enable entry into HE settings within the United Kingdom. BTEC courses are vocational and renowned for providing specialist and applied work-related learning across a range of sectors whereas A-Levels offer more traditional subjects and class-based approaches to teaching and assessment. The participant demographics related to each programme of study can be seen in Table 1.

2.3 Procedure

In October 2023, all level four (first year) undergraduate and foundation (level 3) sport students were invited to participate in the study. Following institutional ethical approval, an initial recruitment email outlining the study aims, objectives and procedures to follow, along with participant information sheet and consent form were sent to all students, inviting them to participate. Prior to data collection, consenting participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and they were assigned numbers to protect anonymity.

Surveys were completed during teaching weeks six and seven of semester one (November 2023) at the start of a face-to-face lecture. Participants were briefed to answer each section honestly and to leave any questions blank which they did not fully understand/did not apply to them or their context. Two members of the research team attended each data collection session, distributed then collected hard copies of surveys and responded to any participant queries. Following completion of the survey, participants were invited to attend a focus group, enabling opportunity to expand on their answers provided in the survey.

2.4 Research design

This current study has adopted a mixed methods approach, utilising both quantitative and qualitative techniques to generate data, in order to get a more ‘complete’ picture (Kumar, 2019). Fetters et al. (2013) specify three levels of integration of mixed methods research – design, methods and interpretation/integration. Mixing quantitative and qualitative methods aims to maximize the strengths of each approach, whilst offsetting the respective weaknesses of each to generate stronger conclusions (Stephens and Stodter, n.d.). The quantitative survey aimed to capture data on a large representation of the student cohort at level four in order to gain a generalized view of their previous educational backgrounds and experiences, and expectations of study at HE. The subsequent qualitative focus groups provided the opportunity to gather further insight and rich description related to the research questions that the survey on its own may not provide. Likewise, the smaller sample size of the focus groups may have been relatively limited in generalisability on their own (Stephens and Stodter, n.d.).

2.4.1 Survey

The survey structure was developed by the research team and informed by previous HE transitional studies (e.g., Hayman et al., 2017) which had identified several relatable variables and key demographics. The survey, initially piloted on a group of undergraduate sport students, informed the final design, which comprises mainly closed questions, including a mix of yes or no and likert scale options. There were no correct or incorrect answers. The survey was piloted with four second-year sport undergraduate students which established an approximate completion time of 10 min, with all wording considered appropriate and understandable for first-year undergraduate and foundation cohorts. In the survey, participants provided responses to five separate sections addressing: (A) background demographic information including gender, age, ethnicity, previous study experience and qualifications (B) experiences of completing their further education qualifications at their previous education establishment (C) expectations and experiences to date of their university sports degree programme and (D) skills they perceived as necessary to be successful on their university course and (E) teaching resources they utilized within their further education and university studies to date. A copy of the survey is available on request from the first author.

2.4.2 Focus groups

Whilst the surveys collected data from a larger sample, focus group interviews were subsequently conducted to gainer richer data from a smaller sample group to explore the ‘why’ and ‘how’ rather than ‘what’ and ‘how many’ (Gratton and Jones, 2004). Two focus groups were conducted in March 2024, taking place approximately 4 months post-survey to allow time for participants to reflect on their experiences in HE, whether there had been any mismatch with expectations, and the potential impact of this. The focus groups were semi-structured in nature and informed by the questions posed in the survey, with three level four sport students in each, lasting 34 min and 44 min. Participants were invited to participate from the initial survey sample, with additional consent provided following receipt of a separate participant information sheet. Students were reminded that they were free to withdraw and could answer questions voluntarily.

The focus group data were subject to inductive thematic analysis, a widely-used method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) in qualitative research (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim and read for data familiarity. Transcripts were reread and coded by labeling interesting items deemed pertinent to the research questions. Similar codes were clustered together to generate initial subthemes, and subsequently reviewed. Relationships between subthemes were considered and defined before grouping into high-order themes and used as a structural framework for the section that follows.

2.4.3 Integration

Linking mixed methods of data is key to maximising the strengths of each approach with the whole being stronger than the sum of its parts (Mason, 2006). The quantitative and qualitative approaches form equal parts in this research study (Kumar, 2019). Whilst the survey was used to inform focus group questions, the results from each method were initially analyzed separately, using a phase connection approach for integration, whereby quantitative and qualitative components are separate until an explicit connection is made to provide more complete and validated conclusions (Plano Clark and Ivankova, 2016). Following initial analysis, the results from each approach were merged into a combined dataset to provide a coherent narrative around the three themes of FE experiences and HE expectations and realities. Quantitative survey data were used to explore generalisability of findings from the focus groups, for example, whether the whole cohort view success in HE as aligning to the framing of HE study set by the teaching staff from the previous educational establishment of the focus group participants. Similarly, qualitative data were used to explain the survey results in more depth, e.g., to discuss the practical implications of different class sizes, using contextualized verbatim text examples with further opportunity to reflect on perception of the transition to and experience of HE.

3 Results

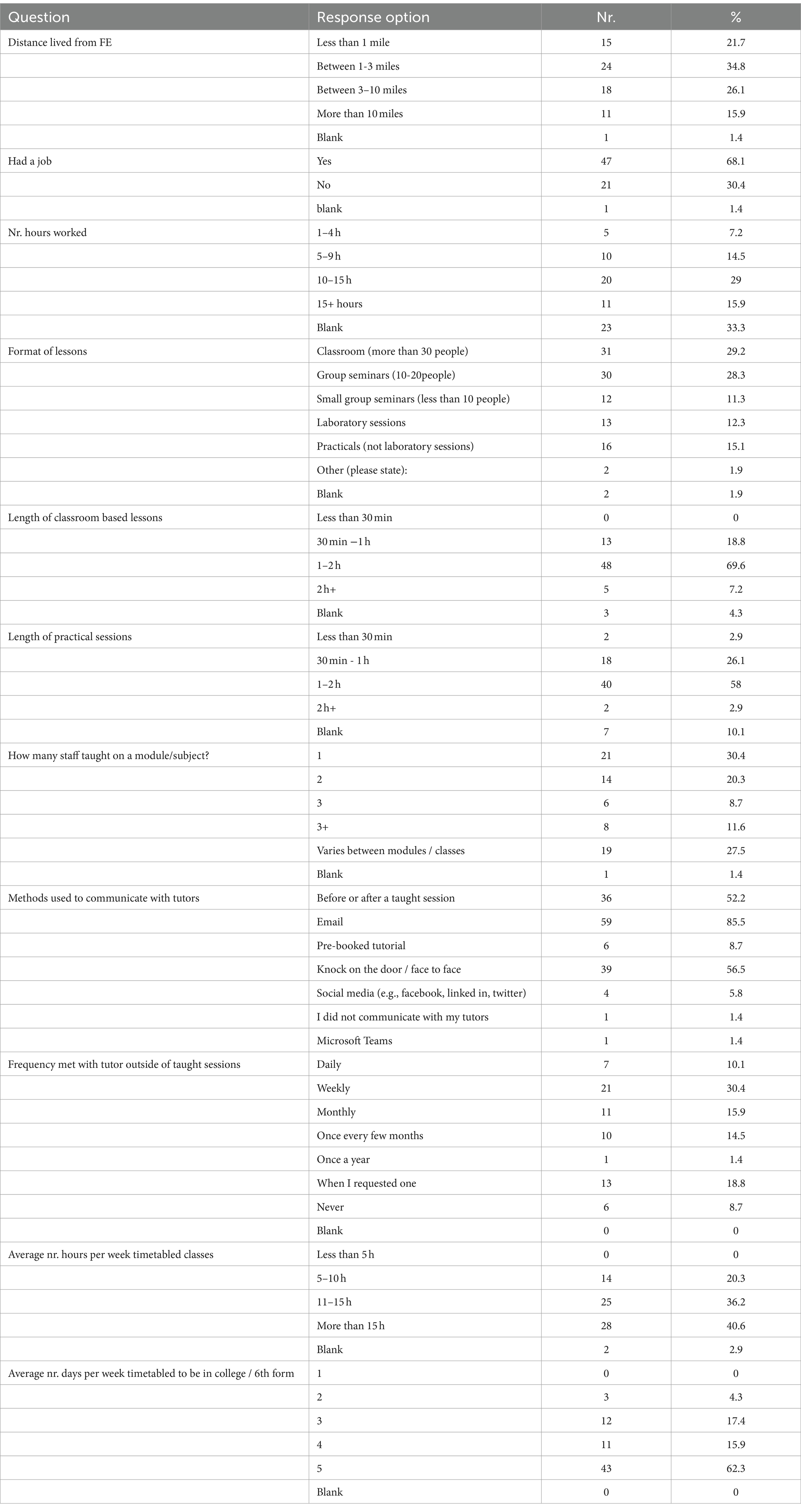

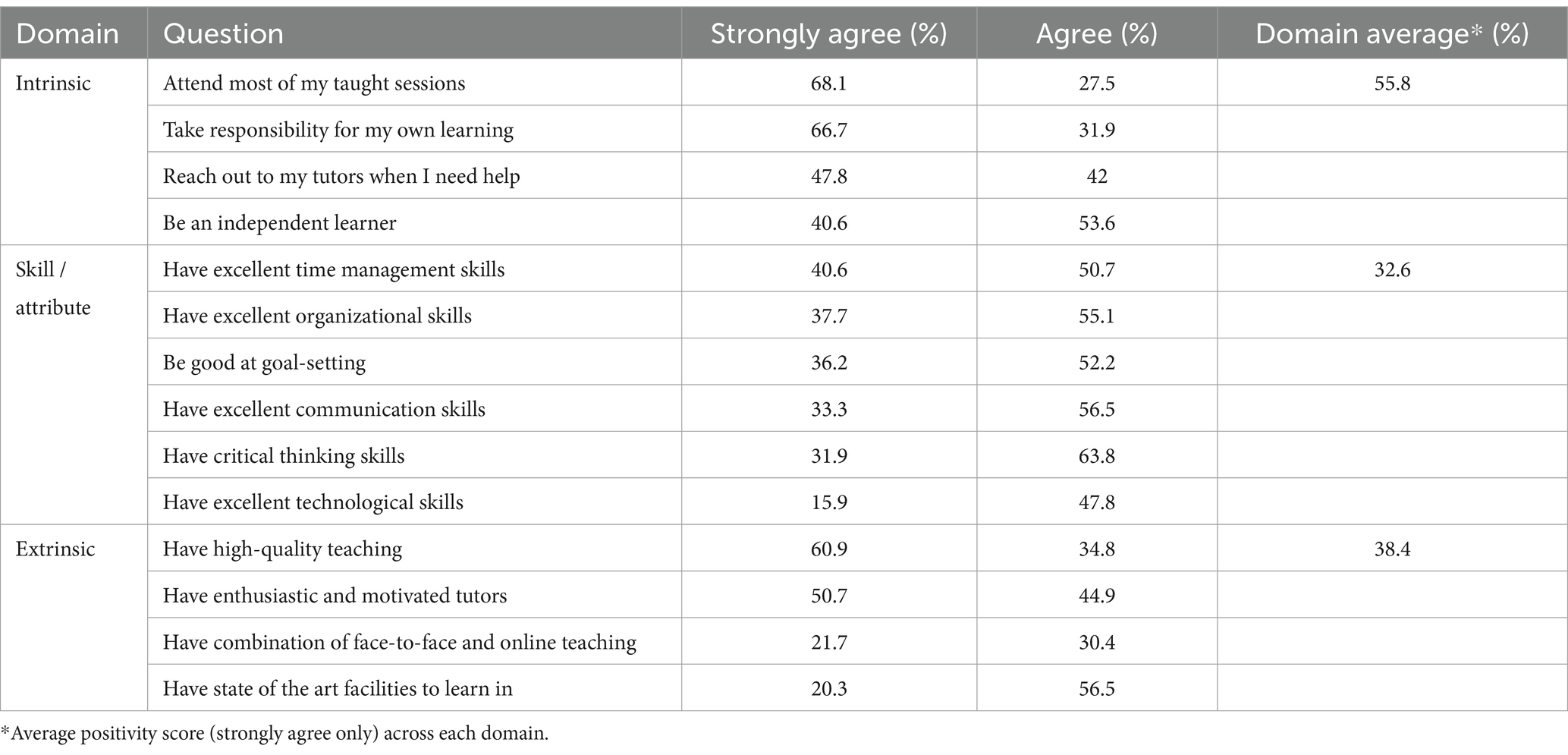

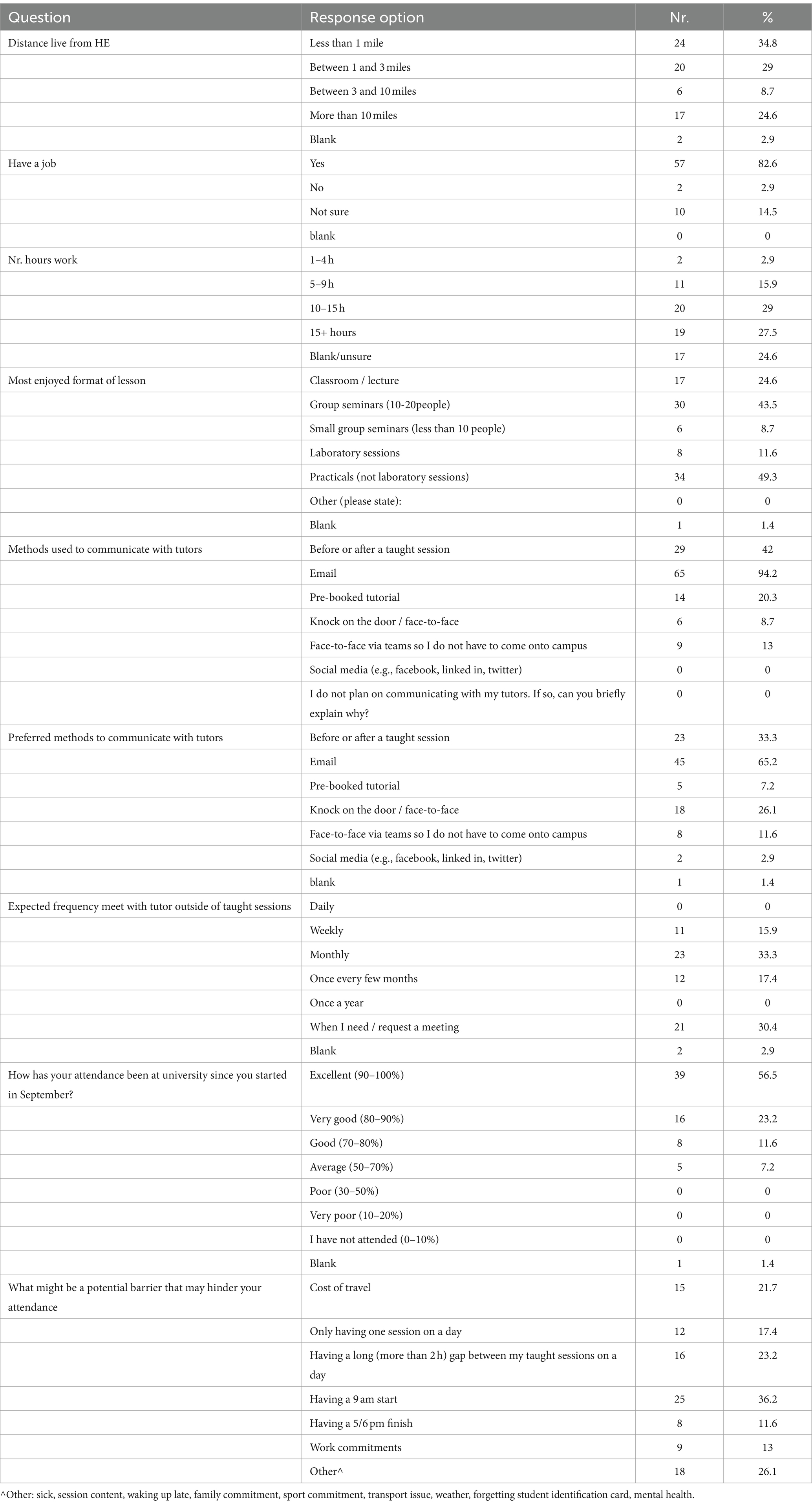

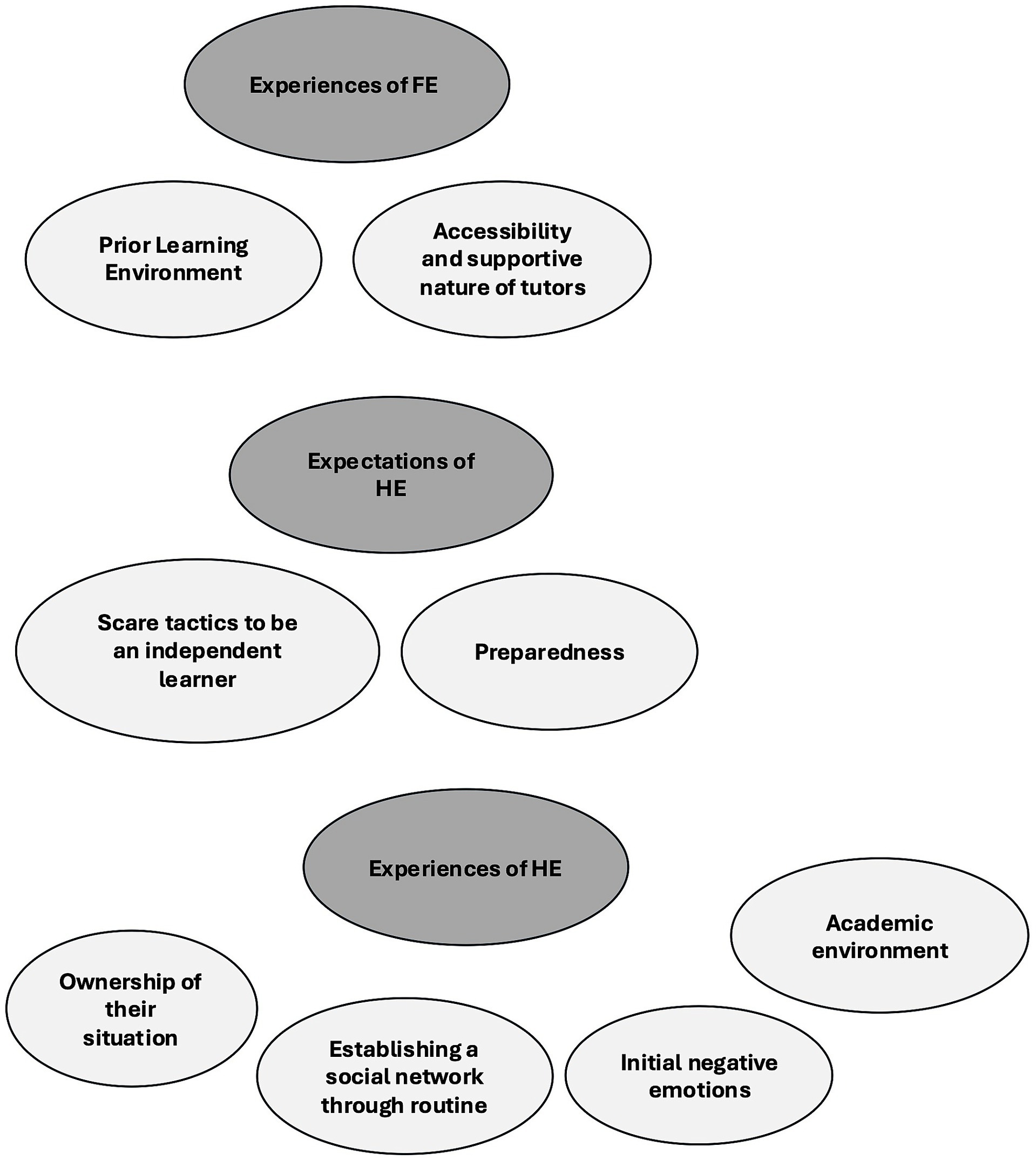

The current study explored students’ experiences of learning and teaching practices in their previous educational establishment, their expectations and initial experiences in HE. The results section integrates both survey and focus group results into a single narrative. Key survey data are drawn from Tables 2–4 and presented alongside the themes reflected in the thematic analysis; These themes and sub themes are represented in the thematic map below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Themes (dark grey) and sub themes (light grey) relating to the research question understanding students’ experiences of learning and teaching practices in their previous educational establishment and their initial expectations and experience in HE.

3.1 Experiences of FE

The theme Experiences of FE included sub themes Prior learning environment and Accessibility and supportive nature of tutors. Students in their prior learning environment experienced a high level of consistency in the tutor that taught them. The highest response was a single tutor (30%). Whilst a portion of students had variation in the number of staff teaching them between modules/subjects (28%), ranging from the same one or two tutor(s) within the subject, occurring due to occasionally being taught by other tutors for sessions “linked to a specific sport” or “someone who knew a bit more about a certain sport.” Few had experienced large (3+) teaching teams (12%).

Students also experienced small class sizes, with a small portion (29%) having experienced a classroom with more than 30 people. “Sport was definitely the smallest, or one of the smallest classes we had,” ranging from “16 to 20 people for each class” to “around ten-ish.” The (small) class size provided opportunity to engage with the session “For the smaller classrooms, I think it was more beneficial [for learning].” The consequence of the small class size provided opportunity to be “a lot more vocal,” potentially because the environment “felt a lot more casual….it was more like discussion based.” This environment also resulted in “more one-on-one conversations [with the tutor]” and personalized learning “you [the student] can set work and [the tutor] be going around so you get more time [with the tutor] if you need it.”

Most students experienced a mixture of lecture and practical/lab sessions. The length of taught classroom sessions were commonly 1–2 h (70%), with few sessions being longer (7%). The length of practical sessions were commonly 1–2 h (58%), although a portion experienced shorter 30 min-1 h sessions (26%). Students were able to select their favored format of lessons (selecting all that applied). Approximately half of students favored practical sessions (49%) and mid-sized group seminars (44%). A quarter of students favored lectures (25%). Small group sessions (9%) and laboratory sessions (12%), whilst preferred by some, were less favorable. Students preferred the practical sessions “just because it’s hands-on,” more than the “theory side” but recognized the value of initial theory (lecture) through “needing the study [lecture] that you do beforehand to then go into the lab.” Students recognized that they “did really like small classroom settings [lecture] with theory” and how their experience was “more down to my teachers.” “It depended on the teacher, so sometimes it was more like sitting and just listening, or sometimes we’d just be doing presentations and us teaching the other students in class.” Where students did comment negatively about their lecture experience, this was attributed to “one subject that’s like 3 h straight, so it was quite boring. You know, because you are just sitting, you just watch the PowerPoint and the teacher speaks. So it was quite repetitive and it was boring as well because it was too long, the classes.”

3.2 Expectations of HE

The theme, Expectations of HE included sub theme Preparedness. The close relationships between students and tutors created an opportunity for tutors to share their experiences and prepare the students in some manner for HE. “For the experience of university, all the teachers were very open about their experiences,” “the actual experience of university both in and outside of the classroom, I like that it’s just open kind of thing. It’s like how they actually presented it, not lied about what it’d be, based on their own experiences with it.” However, whilst students wanted to hear about the experiences of their tutors, not all received it which subsequently resulted in feeling that “They [tutors] did not really prepare us for uni, like what happened there, but they did prepare us a lot when we were applying to it, but not necessarily like what to expect when we go into uni.”

Students recognized that certain academic expectations were preparing them for HE. “English, we kind of learned how to embed quotes into things or like criticism of literature, criticism into our essays. I guess that kind of links to what we are doing now, but just at a very basic level. And then for history, because we were giving presentations, public speaking I guess, and doing our own research. So yeah, kind of. It was kind of like a little preparation to uni, I guess, so.…”

The other sub theme Scare tactics to be an independent learner resulted from the information the tutors shared with the students. “What my teacher told me was that it was going to be a whole bunch of work. They kind of scared us almost.” “We were told, from what I’d heard, everything’s basically on you.” “I just knew that in university we are not going to be spoon fed all the time because in school we were spoon fed a lot. Like the teachers just give you everything and there’s not a proper way to learn it because they are just giving you everything.” Whilst most students were experiencing interactive engaging teaching sessions in their current place of study, when they attend university “the lectures will be on, it’s more of a they talk, then you take down notes.” “It was made out to be like, oh, you have got to be taking notes like every single time you are at a lecture. You have to be proper on it,” “it’s just, they talk to you, it’s not interactive.”

The expectations of HE, shaped by the experiences shared by their tutors, helps to contextualize the responses to the questionnaire which asked students to rate the skills and attributes necessary to be successful in HE. Success in HE was attributed to intrinsic factors related to attendance and being responsible for their own learning (68 and 67% strongly agreeing, respectively). Students shared (see Experiences of FE sub-section) how the interactive and engaging teaching approaches adopted by the teacher shaped their enjoyment of the lectures. Similarly, success in HE was attributed to extrinsic factors associated with the quality and enthusiasm of the teacher (61 and 51% strongly agreeing, respectively).

3.3 Realities of HE

The theme, Realities of HE included sub themes Academic environment, Initial negative emotions, Ownership of their situation, and Establishing a social network through routine.

Within the academic environment students reflected on the teaching format and approach. Whilst students valued the opportunities lecturers provided for engagement in lectures, students recognized how there was opportunity to not engage. “I think the lectures are really engaging. They try to make it… They do not just try to deliver something, but they just… They try to get the students to answer (which does not always work).” “I think that would help as well, if people speak more in classes, contribute more” but “maybe you know that if you do not [answer], someone else will say something or [tutor] move on.” The experiences of the lectures are that “it’s quite a big group and there’s a lot going on in that session.” “The smaller ones [seminars/practical] are just better…because everyone actually interacts and talks.” “Like for physiology our practical sessions, because it’s quite small, I actually got to talk to so many people I did not think I would have spoken to besides these two [gestures to others in the focus group]. So it’s like, okay, I got to know more people. So I like the smaller ones because you get to like meet new people you did not think you would speak to.” “Yeah, people talk more in seminars.”

Student’s experienced seminars differently to their previous educational environment. “It’s quite different how seminars work here… [school was] like a self-directed session rather than you telling us, [at university] you have to do this [activity] in this particular seminar. Yeah, [at school] it’s just like we do whatever work we need to get done, basically. They just give us free time during school.”

Students reflected the different approach to assessment between previous and current place of study. “In my previous school we just had like a week [to complete part of an assessment], they will not really give us all [of the assessment] they would, I guess, they would give us [a weekly] due date but it would not be as much.” In their current place of study, students face “a set date on when everything’s due and it’s usually months ahead so we have actually time to work on it” resulting in “we know our assignments from the get go, we know what we are building toward, so there’s that clear plan.” “Whereas here, it’s you have got so much time to work toward it.”

Students valued the approachable, pastoral nature of lecturers. “It just feels like they care, not just as a student, but as a person as well. Emotionally, they’ll be like, oh, if you need anything, let me know. So I think that just makes my day as well.” “I definitely like it when lecturers are more open. It just makes it less scary as well, and I can ask. I’m not too shy to ask for help.” “Here it’s like, it’s not just about the lectures, they will also come and ask if you need anything or if you just need to talk. There’s a lot of support, not just from the lecturers, but also if you need other stuff.” “I feel like they encourage you to book a meeting if you are lost or to ask questions if you feel lost or you need help. They invite you to do it.” “In university, everyone is really welcoming and encourage you to ask for help. So you can book a meeting with anyone.” “Usually a meeting is 15 min, I think. I wanted more, and most of the time, they let you take as much of their time as possible. But I know everyone’s really busy, but they still make time for you.” “And here it’s more like you can talk to them [academic staff] a bit more freely, you know, I feel like there’s more of a connection. It helps, it’s less scary I guess to ask or to like just talk about something like, I do not know, anything else. It is definitely easier.”

The realities of HE were met with initial negative emotions. The initial experiences of the large cohort lectures “was overwhelming, because the first day I went all the way to the back, and I sat, and I can see everyone’s laptops, and I’m just like, I feel like I wasn’t doing the work, because everyone’s typing, typing, typing, and I’m just sitting there like, oh, what am I doing? So it was overwhelming.” But others “did not feel like any particular way, I was just like, okay, well, there’s a lot of people I have to find a place to sit. That’s all I thought.”

Students reflected that during the initial weeks, they had an initial “dislike,” or “shock,” but over time something changed, “but I was like, then I got used to it.” “I think it was a bit of a shock, but then I think after a couple of weeks it kind of was just a really smooth transition,” “but once you get into it, uni is actually quite a smooth transition, I think.” “Yeah I actually do really enjoy coming to uni. I did not really enjoy going to school before. I hated it, I did not even want to do a degree first because I thought it would be the same like initially when I first started, yeah, but then I like it now.” “I actually like uni now. Because from high school it’s different. So I’m enjoying uni and I’m especially like because I’m doing what I like so I’m really enjoying the course and just the uni experience.”

Part of the enjoyment reflected by students may be attributed to the “refreshing nature” of HE, “you are used to being in an environment where you have got to study, but then coming to university, it felt a bit more refreshing,” “I think that university is a bit better, I’d say. I think it’s just more relaxed…. sixth form was casual but this is a lot more casual,” “there’s a lot more breathing room to kind of relax.” “It’s a lot more of a relief, it’s like, okay I get to do this and then I get the rest of the day to myself to either continue studying if you need to or just get on with whatever you need to do in the day. It’s a lot more relaxing, you get a lot more free time I’d say.”

Students recognized the need to take ownership of their situation and the responsibility of self in their success, “It’s you who fails at the end of the day, so there’s a consequence.” “Like, it’s just all independent and down to you. Like, if you are willing to learn, you are able to learn.” “And then you are placed into a room where… I’m making it more scary than it is, but you are in a room with complete strangers, even the lecturers, you do not know them, they are not going to do the work for you, so that’s when you are kind of like, oh, okay, I’ve got to do this now, I cannot rely on, just because I know this lecturer, I know this person, I know everyone here, it’s like you have got to do it for yourself, you kind of have to, it’s not, for me, it’s not like learning it, it’s like, okay, I’m put in this situation, I am forced. You’ve got to work it out.” “Here I’m actually doing things by myself which I really like because I’m actually being independent doing my own research. Last semester I really liked the assignments because I got to do it by myself as well.”

Students’ external environment outside the university impacted their approach to studying. It was realized that a consequence of having to be independent outside the university resulted in independence leaking into being an independent student. “I lived at home and now I’m living in dorms, it’s completely different. I have to buy my own groceries and everything and get a job and what not. I could not really have those opportunities when I was at home because that’s stuff my parents do. They have their own job, like getting the money in. I could not get a job because I’d have school all day. So I guess that type of individuality would be different to the previous education.” “So I still think there’s a lot more to it, that, a lot more responsibility, as opposed to just being at home.” “I think the only shocking thing was, well not really shocking, but the living by myself thing, that’s the only thing I did not really prepare myself for.”

Recognising the opportunities outside of formal studies created opportunities for students to grow their whole self. “For me it’s the amount of opportunities to do stuff outside of uni [course]. I really like the fact that they have societies.” “And I also like the fact that we can do the professional development, they give us a lot of opportunities to just try stuff really, because you will do things that will build you up, like your CV and stuff, so if that wasn’t compulsory, I do not think I would have done it, but now that I’m doing it, it’s like, oh this actually helps. So I do, I do like the PDT [Personal Development Tutorial; pastoral system] and I do enjoy my courses as well and I do like the lectures because they are all so nice.”

In the initial weeks, students established a social network through their routine. “I think just having that, that kind of routine, like at the beginning, so you come in, the first time you sit down in a lecture hall and there’s like 100 students there, and you are just not used to it at all, and then you go into a seminar and it’s back down to 20, 30, or well, it should be probably higher, but most of the time it’s like, it’s like, once you just get used to that, like, oh, even speaking in front of 100 people is completely different to the thing you do before, especially when you do not know any of them.” The familiarity of routine, shared with many other students created opportunity to establish new friendships, “I think it’s once you are in a routine and then you become familiar with people as well, obviously the lecturers and people in the class. So, see, in the first, like, two, three days, I was by myself and I was like, okay, this is going to be a long three years. And then we [fellow students] became friends. We become friends with some other people as well who we actively see all the time, communicate with.” This experience also resonated with international students, “Oh, well it’s because I’m an international student, so like, when I first came here I’m away from my family and my own friends, and it was hard to make friends when I first came as well. So I was like by myself and I did not really understand how to even use Canvas [online learning management system] for example. So it was like I was doing things by myself and it just got depressing for like the first few months because I was by myself. But then obviously after I met them [friends] and then I got to know the course and I got used to things, I started to like it.” The smaller teaching groups also facilitated opportunity to connect, “I feel like for the practicals, the physiology ones, we got split. We’re not in the same group, but they are smaller groups, so I’ve met people I’ve never talked to before and they are really nice, but the thing is that they have been split from their friends, that they’ll actually talk to you.”

The development of a friendship group served to remove elements of isolation, “So once you have your friend group, like, we used to have a two hour break, I think, after the first lecture. So like once we had something to do through that [break], or because obviously, there’s wasn’t really much work set at the start. It’s like, you just had a routine, you knew you had people you’d go there with, you wasn’t by yourself and you got a bit more confident with the lecturer and the lecturers themselves. I think it just became a lot more smooth,” “and especially once you then get friends or you end up not having to spend like two hours alone, like in between slots” and “this semester I would say I’m much better, but last semester I was just like getting used to things and doing things by myself so it was not what I expected uni to be. Quite an adjustment.” ‘You just had a routine, you knew you had people you’d go there with, you wasn’t by yourself and you got a bit more confident with the lecturer and the lecturers themselves.”

4 Discussion

To better understand the link between the risk to non-continuation (drop out) when transitioning into HE and how this is impacted by a student’s expectations when entering HE, the current project utilized focus groups, informed through an initial survey, to explore students’ experiences of learning and teaching practices in their previous educational establishment and their initial expectations and experience in HE. Results highlighted themes aligned to students’ experiences on FE, expectations of HE and Experiences in HE. The discussion considers The reality of HE for a student, identifying what is missing as they transition from FE into HE.

Understanding how to be an independent learner and possess effective time management skills are necessary for student success (Christie et al., 2013). The development of these (and related) academic skills have been similarly reported in the literature as important in facilitating student transition into HE (e.g., Scouller et al., 2008; Timmis et al., 2022; Van der Meer et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018) and understood as “early transition needs” to enable integration into the academic environment (Wilson et al., 2016). It is through establishing these academic skills that students begin forming a positive student learner identity (Leese, 2010), which is an essential factor in the persistence and success of a university student (Briggs et al., 2012).

In the current study, at the start of their HE journey, students did not recognize the importance of being an independent learner or requiring effective time management skills; the highest rated skill was time management, but only 41% strongly agreed this was valuable. It should be recognized that students have come from an FE environment with high dependence (support) from their tutor which did not necessarily expose them to the level of independence and time management skills needed in HE. As one student commented in the focus group, “Like the teachers just give you everything and there’s not a proper way to learn it because they are just giving you everything.”

Whilst students studying at university are required to become “self-regulated learners” (Zimmerman, 2000), they need support, starting during induction/orientation week, and continuing throughout the first year (Palmer et al., 2009; Van der Meer et al., 2010) as they learn to become independent (Wilson et al., 2016). This support requires a nuanced co-curricular and curricular approach which recognises the diversity within the first-year student cohort (e.g., where students have progressed from), subsequently allowing distinct learner identities to be developed (i.e., Briggs et al., 2012). Our previous research has demonstrated the value of utilising pre-arrival resources to support students’ transition into HE and a similar pre-arrival model could be employed as a skills development programme.

The relationships students develop with academic staff and their personal tutor are an important part of their integration into academic life (McGivney, 1996). Experiencing staff as supportive and approachable helps students to gain confidence within the academic environment and increases their willingness to seek out support (Morosanu et al., 2010; Tett et al., 2017). However, students can perceive the relationships with academic staff as much more distant compared to their previous place of study, where interaction with teaching staff was embedded in everyday learning practices (Christie et al., 2008). In the current study, whilst students highlighted the approachable, pastoral nature of the lecturers, students reported that the frequency of communication with their tutor reduced from FE to HE, communicating daily/weekly reducing from 40 to 16%, and communicating monthly increasing from 16 to 33%. The reduction in contact with staff between FE and HE likely impacts the perception from students that academic staff are much more distant which could be further exacerbated in an environment where students have high expectations with being able to access academic staff outside of scheduled teaching classes (Tomlinson et al., 2023).

In FE, most students used emails (86%) as a common method of communicating with tutors. However, half also relied on more informal ‘catching’ the tutor around teaching session (52%) or dropping by the tutor’s office (57%). In HE, 94% of students use email to communicate with tutors, however, only 65% prefer to use this method of communication. 42% ‘catch’ the tutor around the teaching session, with 33% preferring this approach. 26% prefer to knock on the door, but only 9% use this approach to communicate. Only 20% make use of the tutorial system (whether in person or online) and only 7% prefer this approach; further work is needed to better understand students’ reticence to use the tutorial system.

In HE, whilst emails are the mechanism for students to communicate with lecturers, the less formal approaches used in FE, whilst preferred, are absent. It is likely that this initial negotiation of communication expectations serves as a period of ‘Culture Shock’, characterized by feelings of disillusionment and dejection, as students potentially face adjustment to the changes in their environment (Risquez et al., 2008). Recommendations for practice suggest (in the initial weeks of a student’s transition into HE) holding course leader ‘drop in’ sessions, when an open-door policy is increasingly provisioned, reducing as the term progresses.

The gap between student expectation and experience when joining their course is common (Holmegaard et al., 2014). In the current research, students highlighted how they came from an FE environment where they experienced high levels of support and connectedness to their tutor and class. However, when entering HE, they experienced initial negative emotions, feeling overwhelmed, isolated and lonely. Whilst the initial ‘culture shock’ (Risquez et al., 2008) and negative emotions dissipated as the term progressed (likely as they established a social network and sense of connectedness through their routine), there is clear opportunity to better support the transition of students into the HE environment. Particular effort should be directed toward modules with high student numbers, to tackle the ‘sea of students’ in the lecture and mitigate against student’s feeling overwhelmed and lost amongst the masses. In addition, where students are experiencing a variety in lecturers, additional work is required to develop a sense of belonging and connectedness (Artinger et al., 2006), such that students feel connected and supported (Hausmann et al., 2007). Indeed, students who do not feel adequately supported by their institution are more likely to drop out, especially in their first year of study (Wilcox et al., 2005).

Results from this current project provides additional support for designing increasingly flexible and relational modes of sport education provision (Su and Wood, 2023). This relationship rich approach to education (Felten and Lambert, 2020; Gravett, 2023) will likely better support the academic needs and ease the transition to independent learning of sports students as they enter HE. Whilst resource constraints will likely impact pedagogic design principles, recommendations for practice should review initial large group sessions (lectures of 100+ students) and instead consider smaller, more personalized learning with the same lecturer throughout several weeks, enabling social networks to be established quicker and increased connectedness with their lecturer; sessions can develop into larger groups as the term progresses.

Tinto’s (1993) theory of student integration identifies the importance of social interaction in university as it enables students to create a sense of belonging to the institution, a critical part of the retention process (Wade, 1991). When students develop this sense of belonging, they become involved in other university activities and further integrated into the university (Miller, 2011). Students, however, often do not immediately fit in at university and encounter a transient space between home and university life, where they experience feelings of not belonging (Blair, 2017). Transitioning students therefore need support with getting to know their peers and the university community and in feeling at home in HE (Ackermann, 1991; Hausmann et al., 2007; Cabrera et al., 2013; Gale and Parker, 2014; Coertjens et al., 2017).

The results from the current work have identified the contrast between the relative high level of support and frequency of contact with their tutor in FE and the reduction when entering HE. The initial negative emotions reported in the focus groups when entering HE may well be attributed to the reduced contact or loss of support between places of study. Coupled with aspects of isolation in the initial weeks of HE, this could be attributed to the idea of mattering (France and Finney, 2009).

Mattering is conceptualized through feeling that we impact the lives of those around us and are significant to our immediate environment (Elliott et al., 2004)and is important for developing self-identity, sense of belonging, and understanding one’s purpose in life (Elliott et al., 2004; Rosenberg, 1985; Taylor and Turner, 2001). France and Finney (2009) make an important distinction between belonging and mattering; belonging to a group not being sufficient to elicit feelings of mattering. Rather, for an individual to matter, not only does their presence in the group need recognising and valuing, but the individual must, themselves feel as though they are important and make significant contributions to the group. Through ensuring students, as they enter HE, are afforded opportunity to develop meaningful relationships with people who are focused on the student’s welfare (e.g., fellow students, lecturers, personal tutors etc.), this will foster a sense of mattering and fill the need to belong (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Through actively encouraging students early in their HE journey to engage in wider university activities will also increase the student’s opportunity to forge connections and foster a sense of mattering.

Likely the result of the experiences and advice received from the students’ FE tutor (see 3.2 Expectation of HE sub-section), students recognized the importance of being responsible for their own learning (67% strongly agreed this was a key skill). Sub theme taking ownership (of both the personal and professional) highlighted students’ lack of familiarity and preparedness with the freedom HE ‘life’ entails (Liu and Zhang, 2023). This lack of preparedness is likely associated with their experiences in FE where they attended every day (62%) or 4+ days (78%). In HE this reduced to ~3 days a week with students experiencing gaps between teaching sessions, uncertain how to manage these breaks. The reduction in time spent in university is filled by students having a part-time job. Only 3% of students stated for certain that they would not have a part time job. 55% stated that they planned on working 10+ hours a week; approximately one third (28%) planned on working 15+ hours a week, equivalent to 2 full day’s work. Our previous research highlighted the need for students, as they transition into HE, to be aware of their personal needs. Specifically, the need to take care of oneself, paying attention to different aspects of life that affect overall wellbeing (Timmis et al., 2022). Students need to be supported in negotiating the demands of paid employment and university studies through learning to cultivate a healthy lifestyle and taking care of one’s mental health (Timmis et al., 2022). With the number of students in part-time work increasing, alongside the number of hours worked per week (Wonkhe, 2024) institutions are being challenged to consider how the part-time work students undertake alongside their studies can become increasingly relevant to their future careers and integrated into their learning (Wonkhe, 2024). Integrating paid employment into a student’s subject of study would provide a more cohesive educational journey, affording the opportunity for the skills and knowledge developed within their paid employment to permeate into their studies, and vice-versa.

As students adapt to being responsible for their own learning, most students (92%) reported having at least ‘good’ attendance in HE. However, 10% of the sample stated that their attendance (at best) would be either ‘average’ or ‘good’, suggesting that they would miss between 1 in 5 sessions (20%) to 1 in 2 sessions (50%). Barriers to attendance are a little contradictory. The most frequent barrier was reported as a 9 am start (36%), but only having one session in a day (17%), possibly due to cost of travel with repeat commutes to the university (22%) was a barrier; only 25% of the sample are commuter students, traveling 10+ miles to attend HE. 64% live close (less than 3 miles) to campus. Conversely, a long break between sessions (23%), or sessions finishing later into the afternoon/early evening also impacted attendance (12%), presumably due to part-time work commitments.

It is recognized that the current study only focused on capturing the lived experiences of Sport and Exercise Science undergraduate students, and this was deliberate. When students enter HE, they are not only faced with understanding the wider university culture in which they operate (Beasley and Pearson, 1999), but the culture of their specific study programme, and this requires getting to know the place, practices, and knowledge of that particular environment (Beasley and Pearson, 1999; Gregersen et al., 2021). Due to cultural differences across study programmes (Ulriksen et al., 2017) and institutions, it was necessary to ensure that the lived experiences gathered from the students was specific to the context of their culture. Readers of this research are encouraged to view these results through the lens of their particular environment (Smith, 2018).

Our previous work (Timmis et al., 2022, 2024) suggested that student transition into HE is not a one-off event, completed during welcome/induction week. Rather, it is a more fluid and enduring component of the university experience (Pennington et al., 2018) which is shaped by the individual experience students gather in their complex interaction with their institution (Trautwein and Bosse, 2017). Future research should therefore consider a longitudinal approach which goes beyond capturing the students’ initial experiences and recognising longer-term challenges or successes as they transition into their HE environment.

5 Summary

The current research identified specific challenges students face as they transition into HE, often resulting in an initial culture shock as that adapt to their new learning environment. These challenges are, to some extent, a consequence of their previous learning environment. Whilst expectations of HE were cultivated in their previous educational environment, they were not always accurate and resulted in a mismatch between expectation and reality of HE. Additional work is needed to prepare students for the realities of HE through providing tutors (in FE) with more accurate understanding of the realities of HE and ensuring pre-arrival information for students enables a greater understanding of the realities of HE.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Anglia Ruskin University Faculty ethics panel. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ackermann, S. P. (1991). The benefits of summer bridge programs for underrepresented and low-income transfer students. Commun. Junior College Res. Quart. Res. Pract. 15, 211–224. doi: 10.1080/0361697910150209

Artinger, L., Clapham, L., Hunt, C., Meigs, M., Milord, N., Sampson, B., et al. (2006). The social benefits of intramural sports. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 43, 69–86. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.1572

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Beasley, C. J., and Pearson, C. A. (1999). Facilitating the learning of transitional students: strategies for success for all students. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 18, 303–321. doi: 10.1080/0729436990180303

Blair, A. (2017). Understanding first-year students’ transition to university: a pilot study with implications for student engagement, assessment, and feedback. Politics 37, 215–228. doi: 10.1177/0263395716633904

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briggs, A. R., Clark, J., and Hall, I. (2012). Building bridges: understanding student transition to university. Qual. High. Educ. 18, 3–21. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2011.614468

Burnett, L. (2007). “Juggling first-year student experience and institutional change: an Australian example” in The 20th international conference on first year experience (Hawaii), 1–33.

Cabrera, N. L., Miner, D. D., and Milem, J. F. (2013). Can a summer Bridge program impact first-year persistence and performance?: a case study of the new start summer program. Res. High. Educ. 54, 481–498. doi: 10.1007/s11162-013-9286-7

Christie, H., Barron, P., and D’Annunzio-Green, N. (2013). Direct entrants in transition: becoming independent learners. Stud. High. Educ. 38, 623–637. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.588326

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., Hounsell, J., and McCune, V. (2008). ‘A real rollercoaster of confidence and emotions’: learning to be a university student. Stud. High. Educ. 33, 567–581. doi: 10.1080/03075070802373040

Coertjens, L., Brahm, T., Trautwein, C., and Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2017). Students’ transition into higher education from an international perspective. High. Educ. 73, 357–369. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0092-y

Cook, A., and Leckey, J. (1999). Do expectations meet reality? A survey of changes in first-year student opinion. J. Furth. High. Educ. 23, 157–171. doi: 10.1080/0309877990230201

De Clercq, M., Roland, N., Brunelle, M., Galand, B., and Frenay, M. (2018). The delicate balance to adjustment: a qualitative approach of student’s transition to the first year at university. Psychologica Belgica 58, 67–90. doi: 10.5334/pb.409

Denovan, A., and Macaskill, A. (2013). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of stress and coping in first year undergraduates. British Educational Res. J. 39, 1002–1024. doi: 10.1002/berj.3019

DfE (2023). Crackdown on rip-off university degrees. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/crackdown-on-rip-off-university-degrees#:~:text=Under%20the%20plans%2C%20the%20Office,deliver%20good%20outcomes%20for%20students (Accessed March 2024).

Elliott, G. C., Kao, S., and Grant, A. (2004). Mattering: empirical validation of a social-psychological concept. Self Identity 3, 339–354. doi: 10.1080/13576500444000119

Farhat, G., Bingham, J., Caulfield, J., and Grieve, S. (2017). The academies project: widening access and smoothing transitions for secondary school pupils to university, college and employment. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 5, 23–30. doi: 10.14297/jpaap.v5i1.229

Felten, P., and Lambert, L. (2020). Relationship rich education: How human connections drive success in college. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., and Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 48, 2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117

Fincham, E., Rózemberczki, B., Kovanović, V., Joksimović, S., Jovanović, J., and Gašević, D. (2021). Persistence and performance in co-enrollment network Embeddings: an empirical validation of Tinto's student integration model. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 14, 106–121. doi: 10.1109/TLT.2021.3059362

France, M. K., and Finney, S. J. (2009). What matters in the measurement of mattering? Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 42, 104–120. doi: 10.1177/0748175609336863

Gale, T., and Parker, S. (2014). Navigating change: a typology of student transition in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 734–753. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.721351

Gravett, K. (2023). Relational pedagogies: Connections and mattering in higher education : Bloomsbury Publishing.

Gregersen, A. F. M., Holmegaard, H. T., and Ulriksen, L. (2021). Transitioning into higher education: rituals and implied expectations. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45, 1356–1370. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1870942

Gu, Q., Schweisfurth, M., and Day, C. (2010). Learning and personal growth in a 'Foreign' context: Intercultural experiences of international students. Essex: Colchester.

Hadjar, A., Haas, C., and Gewinner, I. (2022). Refining the Spady–Tinto approach: the roles of individual characteristics and institutional support in students’ higher education dropout intentions in Luxembourg. Eur. J. High. Educ., 1–20.

Hausmann, L. R., Schofield, J. W., and Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and white first-year college students. Res. High. Educ. 48, 803–839. doi: 10.1007/s11162-007-9052-9

Hayman, R. (2018). A flipped learning maiden voyage: insights and experiences of undergraduate sport coaching students. Innov. Pract. High. Educ. 3, 81–102. http://journals.staffs.ac.uk/index.php/ipihe/article/view/134

Hayman, R., Allin, L., and Coyles, A. (2017). Exploring social integration of sport students during the transition to university. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 5, 31–36. doi: 10.14297/jpaap.v5i2.284

Hillman, N., (2021). A short guide to non-continuation in UK universities. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/A-short-guide-to-non-continuation-in-UK-universities.pdf (Accessed November 2023).

Hockings, C., Thomas, L., Ottaway, J., and Jones, R. (2018). Independent learning – what we do when you’re not there. Teach. High. Educ. 23, 145–161. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2017.1332031

Holmegaard, H. T., Madsen, L. M., and Ulriksen, L. (2014). A journey of negotiation and belonging: understanding students’ transitions to science and engineering in higher education. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 9, 755–786. doi: 10.1007/s11422-013-9542-3

Jonker, L., Elferink-Gemser, M., and Visscher, C. (2011). The role of self-regulatory skills in sport and academic performances of elite youth athletes. Talent Dev. Excell. 3, 263–275.

Larsen, A., Horvath, D., and Bridge, C. (2020). 'Get ready': improving the transition experience of a diverse first year cohort through building student agency. Student Success 11, 14–27.

Leese, M. (2010). Bridging the gap: supporting student transitions into higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 34, 239–251. doi: 10.1080/03098771003695494

Liu, Y., and Zhang, X. (2023). Understanding academic transition and self-regulation: a case study of English majors in China. Human. Soci. Sci. Commun. 10:98. doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-01596-z

Lizzio, A. (2006). Designing an orientation and transition strategy for commencing students. First Year Experience Project: A conceptual summary of research and practice.

Lowe, H., and Cook, A. (2003). Mind the gap: are students prepared for higher education? J. Furth. High. Educ. 27, 53–76. doi: 10.1080/03098770305629

Mason, J. (2006). Mixing methods in a qualitatively driven way. Qual. Res. 6, 9–25. doi: 10.1177/1468794106058866

Maunder, R. E., Cunliffe, M., Galvin, J., Mjali, S., and Rogers, J. (2013). Listening to student voices: student researchers exploring undergraduate experiences of university transition. High. Educ. 66, 139–152. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9595-3

McGivney, V. (1996). Staying or leaving the course: non-completion and retention. Adults Learn. 7, 133–135.

McMillan, W. (2013). Transition to university: the role played by emotion. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 17, 169–176. doi: 10.1111/eje.12026

Miller, J. (2011). Impact of a university recreation center on social belonging and student retention. Recreational Sports J. 35, 117–129. doi: 10.1123/rsj.35.2.117

Money, J., Nixon, S., Tracy, F., Hennessy, C., Ball, E., and Dinning, T. (2017). Undergraduate student expectations of university in the United Kingdom: what really matters to them? Cogent Educ. 4:1301855. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1301855

Morosanu, L., Handley, K., and O’Donovan, B. (2010). Seeking support: researching first-year students’ experiences of coping with academic life. High. Educ. Res. Develop. 29, 665–678. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.487200

Nicholson, N. (1990). The transition cycle: Causes, outcomes, processes and forms. On the move: The psychology of change and transition, 83–108.

OfS. (2022). Office for Students Strategy 2022 to 2025. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/2bd39abc-837c-4745-ab86-c37c0c0b7a7c/ofs-strategy-2022-final-accessible.pdf (Accessed December 2024).

OfS (2023). How we regulate student outcomes. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/for-providers/quality-and-standards/how-we-regulate-student-outcomes/ (Accessed March 2024).

Palmer, M., O'Kane, P., and Owens, M. (2009). Betwixt spaces: student accounts of turning point experiences in the first-year transition. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 37–54. doi: 10.1080/03075070802601929

Pather, S., and Dorasamy, N. (2018). The mismatch between first-year students’ expectations and experience alongside university access and success: a south african university case study. J. Stud. Affairs Africa 6, 49–64. doi: 10.24085/jsaa.v6i1.3065

Pennington, C. R., Bates, E. A., Kaye, L. K., and Bolam, L. T. (2018). Transitioning in higher education: an exploration of psychological and contextual factors affecting student satisfaction. J. Furth. High. Educ. 42, 596–607. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1302563

Plano Clark, V., and Ivankova, N. (2016). How to use mixed methods research: Understanding the basic mixed methods designs. London: Sage Publications.

QAA (2023). Supporting student transitions. Available at: (https://www.qaa.ac.uk/membership/membership-areas-of-work/teaching-learning-and-assessment/flexible-pathways-and-student-transitions/supporting-student-transitions).

Risquez, A., Moore, S., and Morley, M. (2008). Welcome to college? Developing a richer understanding of the transition process for adult first year students using reflective written journals. J. College Retention 9, 183–204.

Rosenberg, M. (1985). “Self-concept and psychological well-being in adolescence” in The development of the self. ed. R. Leahy (New York: Academic Press), 205–246.

Rowley, M., Hartley, J., and Larkin, D. (2008). Learning from experience: the expectations and experiences of first-year undergraduate psychology students. J. Furth. High. Educ. 32, 399–413. doi: 10.1080/03098770802538129

Scouller, K., Bonanno, H., Smith, L., and Krass, I. (2008). Student experience and tertiary expectations: factors predicting academic literacy amongst first-year pharmacy students. Stud. High. Educ. 33, 167–178. doi: 10.1080/03075070801916047

Smith, B. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual. Res. Sport, Exerc. Health 10, 137–149. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

Stephens, D., and Stodter, A. (in press.). “Mixed methods research in sport coaching” in Routledge handbook of research methods in sport coaching. eds. L. Nelson, R. Groom, and P. Potrac. 2nd ed (London: Routledge). Chapter 16

Su, F., and Wood, M. (2023). Relational pedagogy in higher education: what might it look like in practice and how do we develop it? Int. J. Acad. Dev. 28, 230–233. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2023.2164859

Taylor, J., and Turner, R. J. (2001). A longitudinal study of the role and significance of mattering to others for depressive symptoms. J. Health Soc. Behav. 42, 310–325. doi: 10.2307/3090217

Tett, L., Cree, V. E., and Christie, H. (2017). From further to higher education: transition as an on-going process. High. Educ. 73, 389–406. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0101-1

Thurber, C. A., and Walton, E. A. (2012). Experiences from the field homesickness and adjustment in university students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 60, 1–5.

Timmis, M. A., Humphrey, K., Strongman, C., Scruton, A., Winnard, Y., and Cavallerio, F. (2024). “You've already, kind of, got the wheels moving a little bit”; students' value of pre-arrival support in transitioning into higher education. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 35:100521. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2024.100521

Timmis, M. A., Pexton, S., and Cavallerio, F. (2022). Student transition into higher education: time for a rethink within the subject of sport and exercise science? Front. Educ. 7:1049672. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1049672

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: a theoretical synthesis of recent research. Rev. Educ. Res. 45, 89–125. doi: 10.3102/00346543045001089

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. 2nd Edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tomlinson, A., Simpson, A., and Killingback, C. (2023). Student expectations of teaching and learning when starting university: a systematic review. J. Furth. High. Educ. 47, 1054–1073. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2023.2212242

Trautwein, C., and Bosse, E. (2017). The first year in higher education—critical requirements from the student perspective. High. Educ. 73, 371–387. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0098-5

Ulriksen, L., Holmegaard, H. T., and Madsen, L. M. (2017). Making sense of curriculum—the transition into science and engineering university programmes. High. Educ. 73, 423–440. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0099-4

Van der Meer, J., Jansen, E., and Torenbeek, M. (2010). ‘It’s almost a mindset that teachers need to change’: first-year students’ need to be inducted into time management. Stud. High. Educ. 35, 777–791. doi: 10.1080/03075070903383211

Wade, B.K., (1991). A profile of the real world of undergraduate students and how they spend discretionary time. Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED333776. (Chicago, IL, ERIC Document).

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., and Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: the role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 30, 707–722. doi: 10.1080/03075070500340036

Wilson, K. L., Murphy, K. A., Pearson, A. G., Wallace, B. M., Reher, V. G., and Buys, N. (2016). Understanding the early transition needs of diverse commencing university students in a health faculty: informing effective intervention practices. Stud. High. Educ. 41, 1023–1040. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.966070

Wonkhe (2024). Student part-time work is on the rise. Here’s what universities can do next. Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/our-full-time-students-are-almost-full-time-workers-too/ (Accessed February 2024).

Wrench, A., Garrett, R., and King, S. (2013). Guessing where the goal posts are: managing health and well-being during the transition to university studies. J. Youth Stud. 16, 730–746. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2012.744814

Yorke, M., and Longden, B. (2008). The first-year experience of higher education in the UK. York: Higher Education Academy.

Keywords: higher education, transition, expectation, sport and exercise science, further education

Citation: Timmis MA, Hibbs A, Polman R, Hayman R and Stephens D (2024) Previous education experience impacts student expectation and initial experience of transitioning into higher education. Front. Educ. 9:1479546. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1479546

Edited by:

Mei Tian, Xi’an Jiaotong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Cucuk Wawan Budiyanto, Sebelas Maret University, IndonesiaAsma Shahid Kazi, Lahore College for Women University, Pakistan

Copyright © 2024 Timmis, Hibbs, Polman, Hayman and Stephens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew A. Timmis, bWF0dGhldy50aW1taXNAYXJ1LmFjLnVr

Matthew A. Timmis

Matthew A. Timmis Angela Hibbs2

Angela Hibbs2 Rick Hayman

Rick Hayman David Stephens

David Stephens