- 1School of Education, City University of Macau, Macau, Macao SAR, China

- 2Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, City University of Macau, Macau, Macao SAR, China

Introduction: An increasing body of research has explored the predictive effect of personality traits and affective factors on EFL learners’ willingness to communicate (WTC). However, more is needed to know about how the sub-facets of individual personality traits influence WTC in the classroom context. Therefore, drawing on positive psychology, this study aims to bridge this gap by examining these roles in a mediation model of WTC incorporating FLE and conscientiousness.

Methods: To this end, 244 Chinese EFL undergraduates from two distinct universities participated in an online survey, completing a composite questionnaire of the three constructs. The bootstrapping technique was employed to test the proposed relationships.

Results: The findings indicated a positive correlation between both FLE and conscientiousness with WTC. Additionally, conscientiousness significantly mediated the relationship between FLE and WTC, supporting a partial mediation effect. Also, FLE had a direct influence on conscientiousness. These results may have some notable implications for EFL educators.

Discussion: The adoption of a holistic approach that emphasizes affective factors alongside acknowledging individual differences among learners could enhance students’ willingness to communicate in English.

1 Introduction

Spoken English is a direct manifestation of language aptitude, and it is also a priority for many Chinese EFL students who face communicative difficulties in a non-English environment. Similarly, according to statistics, the speaking component in the IELTS test is one of the most challenging abilities for Chinese EFL learners to improve within a fixed period, often resulting in a specific negative emotion, namely speaking anxiety. Besides, L2 reticence of Chinese students in English learning has been widely observed in classroom settings (Sang and Hiver, 2021), and the reasons for their reticence varied across different communicative contexts (Zhong, 2013), highlighting the need for more support and attention for these language learners. These phenomena have prompted significant research into oral English communicative competence and spoken performance. Following this, the willingness to communicate (WTC) of L2 learners has become a topic in L2 academic research, defined as “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using an L2” by MacIntyre et al. (1998, p. 547), which is considered the last essential step before actual communicative behavior. Given the paramount role of WTC in the development of spoken ability, numerous studies have indicated the relationships between WTC and a variety of cognitive and non-cognitive factors (see the literature review). Empirical findings suggest that students with a higher level of WTC tend to achieve better performance in oral English and vice versa. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the antecedents of WTC, and the current study aligns with this focus by examining the predictive role of foreign language enjoyment (FLE) and Conscientiousness on WTC.

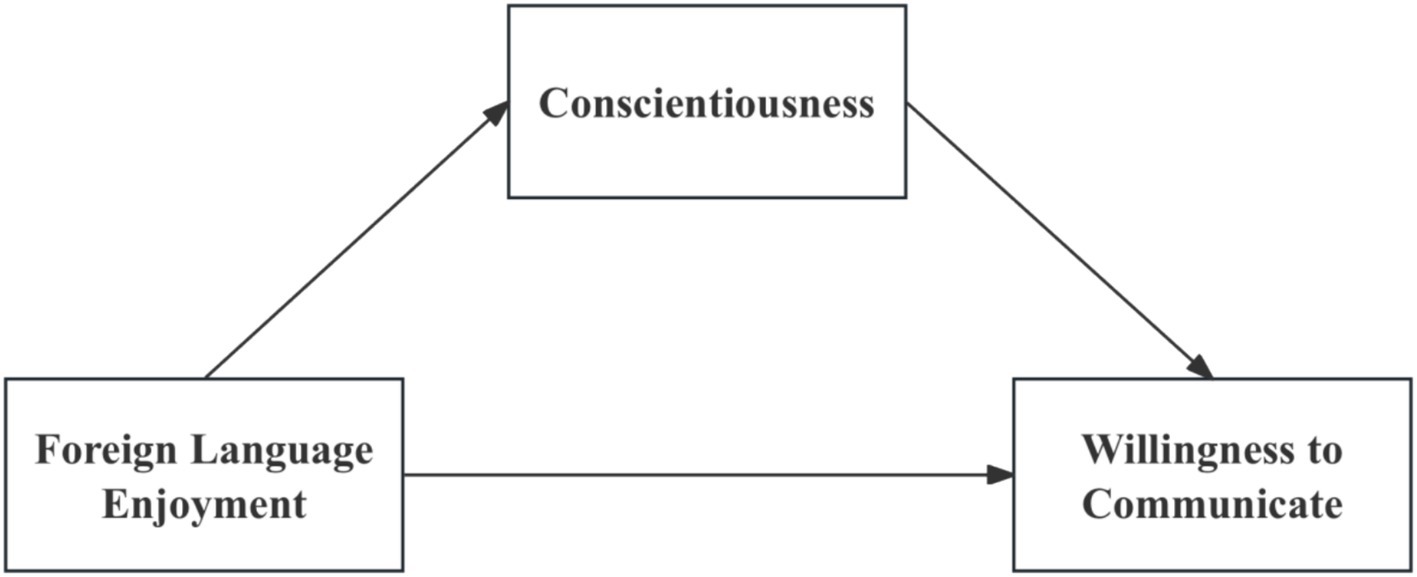

Drawing on positive psychology (PP) in recent decades, positive emotions have been found to have a profound and beneficial impact on the language learning process (Dewaele and Dewaele, 2018). Before this, researchers had focused more on negative affective factors, such as foreign language classroom anxiety (FLCA), stress, and burnout, among others. Consequently, FLE, the primary positive emotion in second language acquisition, has been defined as “a positive disposition toward the foreign language learning process, peers, and teachers” (Botes et al., 2020, p. 282). Following the seminal work by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014), a growing body of research has confirmed that learners who find EFL more enjoyable are more likely to perform better in the learning process (see the literature review). Despite previous findings suggesting a positive relationship between WTC and FLE, based on the theoretical framework that FLE is one of the affective factors that may influence WTC (MacIntyre et al., 1998; see Figure 1), few studies have tested the indirect effect of FLE on WTC. In other words, the potential mediating role of Conscientiousness between FLE and WTC should be further explored.

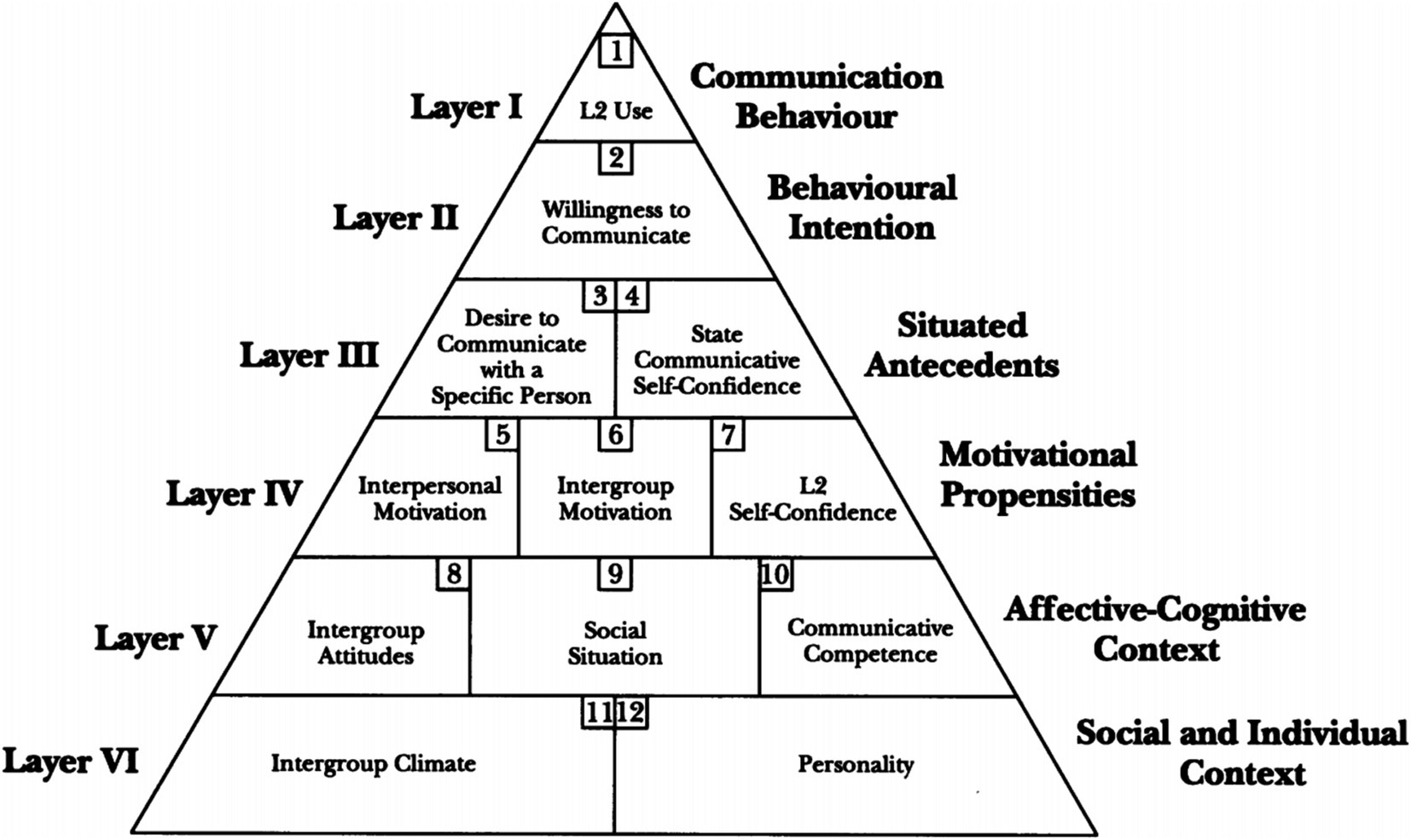

Figure 1. The heuristic model of variables influencing WTC (MacIntyre et al., 1998).

Another variable, Conscientiousness, is worth investigating in the correlation between WTC and FLE due to a greater focus on individual differences among learners (Xu and Zheng, 2022), representing a research shift from teacher-orientation to student-orientation. As one of the five basic personality traits, Conscientiousness consists of a range of characteristic qualities, such as competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation (Costa et al., 1991). These qualities have aroused an increasing interest in the educational field, and there is substantial empirical evidence that Conscientiousness directly or indirectly affects learners’ achievement (see the literature review). Moreover, this personality trait is also one of the fundamental variables in the heuristic model of variables influencing WTC (see Figure 1). However, few studies have deeply investigated the influence of specific facets of this trait on WTC and its interplay with the emotional variable. Therefore, a focused study is needed to confirm the relationship between Conscientiousness and WTC alongside the affective factor FLE.

Although previous studies have revealed a variety of factors that may influence WTC, few have incorporated a specific personality trait, FLE, and WTC into a mediation model. This study aims to deepen the understanding of these factors that impact WTC in the context of the English classroom in China. For this purpose, the PROCESS macro, as a powerful analytic tool, has been used to test the role of these variables in predicting WTC.

2 Literature review

2.1 Willingness to communicate

The concept of WTC was originally from an actual communicative predisposition behavior of first or native-language speakers labeled as unwillingness to communicate, mainly based on personality traits and affective variables (e.g., Burgoon, 1976). After that, McCroskey and Baer (1985) reframed this personality-based construct as WTC, which was fairly consistent across distinct contexts and receivers. To extend the trait-like conceptualization focused on L2 communication, MacIntyre et al. (1998) defined WTC as “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using a second language” (p. 547), which clarified the multi-manifested feature of L2 WTC, as compared to WTC in L1. This concept considers factors that can affect WTC, encompassing both situation-specific and enduring influences, which has been tested by numerous studies (e.g., Guo et al., 2023; Peng and Woodrow, 2010). As shown in the pyramid-shape structure (Figure 1) schematized by MacIntyre et al. (1998), there are six layers in top-down order from the most transient communication behavior layer to the most stable social and individual layer, the combinations of which converge on a specific moment in time to affect the language learner’s decision making and intention of communicating in L2 or not (MacIntyre et al., 2020). However, in addition to the long-term factors, such as personality traits and intergroup climate, as shown in the bottom layer, the fluctuation of WTC in various settings has been captured and established by many researchers (e.g., Kang, 2005; Pawlak et al., 2016), which turned to a recent shift in the last decades focusing more on the dynamic nature of WTC and its situational variables (e.g., Dewaele and Pavelescu, 2019; MacIntyre, 2020; MacIntyre and Legatto, 2011; Nematizadeh and Wood, 2021), indicating that the complexity of WTC is both dynamic and relatively stable.

Given the important role of WTC in communication skills, many researchers have revealed the direct and indirect influences on WTC, including language learning emotions (Pavelescu, 2023), L2 self (Fathi et al., 2023; Lee and Lee, 2020), feedback (Alavi et al., 2021), self-efficacy (Guo et al., 2023), individual differences, such as gender, major and age (Cheng and Xu, 2022), and foreign language anxiety (Barabadi et al., 2022). Among these, Alrabai’s (2022) study in language classrooms highlighted that motivation and anxiety were the most significant direct predictors of WTC, suggesting that situational factors play a crucial role in WTC to varying extents. Despite the growing body of studies on WTC, some questions remain unanswered, particularly about the East Asian EFL learners, who were found by a collection of researchers to be more reticent within the classroom context (Cao, 2011; King and Harumi, 2020; Shao and Gao, 2016). For instance, with a focus on English classes in southern China, Peng (2020) employed the Dynamic Systems Theory (DST) to explore the relationship between Chinese EFL students’ WTC and silence in the classroom. The findings from this study revealed that students spoke English primarily within the confines of pair or group interactions, rarely initiating class-wide discussions. Moreover, a frequent inclination toward silence was observed, attributed to a spectrum of psychological factors, such as being capable but unwilling to speak or unprepared to do so. Consequently, this underscores the imperative to explore this situation-specific construct and its other antecedents in the heuristic pyramid model to bolster students’ predisposition toward verbal engagement and motivate them to break their silence.

2.2 Foreign language enjoyment

Psychology has always significantly influenced second or foreign language learning process particularly concerning negative or aversive emotions, such as foreign language anxiety, boredom, distress, and burnout, among others (Xu et al., 2022). However, an increasing number of SLA researchers have started to concentrate on positive emotions, including joy, interest, contentment, and love, which may “broaden an individual’s momentary thought-action repertoire, the consequences of which in turn build that individual’s personal resources” (Fredrickson, 2004, p. 1367). These positive emotions are one of the three research areas in positive psychology based on the Broaden-and-Build Theory developed by Fredrickson (2001). Although foreign language anxiety is the most widespread negative emotion in the realm of SLA affective studies (Gkonou et al., 2017) and should not be altered by other topics, many language researchers hold that positive-broadening emotions of learners in language learning processes would be a vital additional perspective in SLA research (MacIntyre and Mercer, 2014). Thus, the number of studies on such emotions has considerably surged as they may be beneficial to facilitating L2 learning as well as promoting language learners’ well-being (Li et al., 2018).

Studies on FLE have received increasing attention in the field of L2 learning in the past two decades (Li et al., 2024). The recent definition of FLE is “a broad, overarching positive psycho-emotional variable that is designed to encapsulate a positive disposition toward the FL learning process, peers, and teachers” (Botes et al., 2020, p. 282). In sync with descriptions of positive emotions (Csikszentmihalyi and Csikzentmihaly, 1990; Fredrickson, 2001; MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012), the construct of FLE is two-dimensional, encompassing the social dimension, which manifests as the language learners’ satisfaction drawn from a positive FL classroom atmosphere collectively fostered by teachers and students, and the private dimension about the learners’ internal sense of accomplishment and pride in the face of challenging (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2016).

Copious studies have been conducted to examine the relationship between FLE and a range of factors, including motivation (Dewaele et al., 2023), direct or indirect effects on learners’ foreign language performance or academic achievement (Liu et al., 2024), affective variables, such as FLA, emotion regulation (Dewaele and Saito, 2024; Zhang et al., 2021), and factors pertaining to the teacher as the most key source of FLE (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2019). Proietti Ergün and Ersöz Demirdağ (2022) reported that Subjective Well-Being (SWB) was the strongest predictor of FLE, followed by Perceived Stress (PS) with a small but significant effect, and implied that the overall circumstances of the students’ life influence the classroom dynamics. In line with most of the preceding investigations, Tsang and Dewaele (2023) examined the effects of three FL emotions, FLE, FLCA, and boredom, on the learners’ engagement and skill-specific proficiency within the context of EFL class. Finally, they found that FLE was the leading predictor of engagement and language proficiency. These findings are consistent with the seminal study by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014), who revealed that FLE as an independent notion, interplaying with FLA instead of the opposition of it, has a direct significant influence on learners’ achievement and concluded that “experiencing enjoyment and playfulness in language might be an especially facilitating experience for language learners” (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014, p. 261), which highlights the critical role of this construct in EFL acquisition process and academic research.

2.3 Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a personality trait based on the Five Factor Model (FFM), representing the characteristic qualities of competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation, with both proactive and inhibitive aspects (Costa et al., 1991). The multifaceted conceptualization of Conscientiousness allows scholars to focus on the facet as required by research purposes (Roberts et al., 2014; Spielmann et al., 2022). Additionally, it is posited that specific facets are more predictive of educational performance than the broad Big Five traits (Stewart et al., 2022). Due to its recognition as a significantly robust indicator of high levels of academic accomplishments (McAbee and Oswald, 2013), this trait has drawn the attention of educational researchers, including those in the field of SLA.

In light of the effect of Conscientiousness as a personality trait in educational settings, many scholars have investigated this variable to explore its role in facilitating learning, along with the affective variables. For instance, Botes et al. (2023) measured the relationships between personality, FLE, FLA, and boredom using a series of increasingly restrictive statistical models among 246 adult foreign language learners and demonstrated that Conscientiousness played a moderating role in large statistically significant correlations in those three emotion factors. Conscientiousness has also been identified as a potent predictor of examination results, as reported by Minnigh et al. (2024), who proposed a structural equation between grit, conscientiousness, SAT scores, and GPAs, concluding that grit does not substantially enhance the prediction of academic performance, compared with Conscientiousness. Similarly, Friedrich and Schütz (2023) tested whether Conscientiousness compensates for intelligence or enhances the effect of intelligence on performance in a large sample of 3,775 German students and found that there existed a more vital link between intelligence and grades if students are conscientious. Overall, these findings and inferences regarding Conscientiousness have shown significant correlations with emotional variables and their increased effects on academic achievement. Nevertheless, there is a dearth of studies that integrate affective factors and Conscientiousness into learners’ WTC, with most researchers placing more emphasis on the effects of other four personality traits, including Extraversion, Openness to Experience, and Neuroticism (Piechurska-Kuciel, 2018). Thus, it becomes necessary to explore the role of Conscientiousness in the SLA context with clarity and profundity.

2.4 Relationships between FLE, conscientiousness, and WTC

Given that students with greater enjoyment of learning are inclined to be more willing to communicate within the classroom context (Khajavy et al., 2018), many empirical studies have investigated the relationship between FLE and WTC, finding that FLE has a positive impact on WTC (see reviews by Botes et al., 2022; Cao, 2022). Consistent with these studies, Lee (2020) demonstrated that FLE significantly predicted WTC, along with the perseverance of effort, as one facet of grit. Similarly, the research of Lee et al. (2021) revealed that, in contrast to L2 anxiety, L2 enjoyment served a more significant and positively direct role in WTC among Korean secondary and tertiary students. In a similar vein, Yu and Ma (2024) not only reported the direct impact of FLE on WTC among a substantial sample of 2,426 Chinese undergraduate students but also investigated the mediating effects of FLE on WTC through three distinct pathways involving general language proficiency and grit. In summary, many researchers have validated that FLE may have a notably positive relationship with WTC.

However, scant studies established the importance of Conscientiousness on L2 WTC, while some researchers examined the predictability of other personality traits on WTC. For instance, an earlier study conducted by Oz (2014) examined the relationship between Big Five personality traits and WTC, and the results showed that Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Openness to Experience significantly predicted the WTC. In line with it partially, Khany and Nejad (2016) and Fatima et al. (2020) found that higher openness to experience and Extraversion predicted higher WTC. In contrast to previous findings, Conscientiousness was found to be positively correlated with WTC in several studies (Katić and Šafranj, 2019; Karadağ and Kaya, 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). This aligns with the argument that students who are more conscientious and better organized may show a more positive attitude toward learning a second or foreign language (Krashen, 1981; Lalonde and Gardner, 1984; MacIntyre and Charos, 2016). Considering the significance of this trait in L2 learning, the divergent results underscore the necessity for further evidence to examine the relationship between Conscientiousness and WTC across various contexts.

Regarding FLE and Conscientiousness, very few researchers have examined the relationship between these two variables. In the study conducted by (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2019), significant correlations were found between FLE and four personality traits, namely Cultural Empathy, Social Initiative, Open-mindedness, and Emotional Stability, to varying degrees ranging from low to medium. Although these facets do not completely align with the ones in the FFM, the result highlights the important role of personality traits on foreign language learning emotions, and further investigation may be necessary to support the relationship between these two factors.

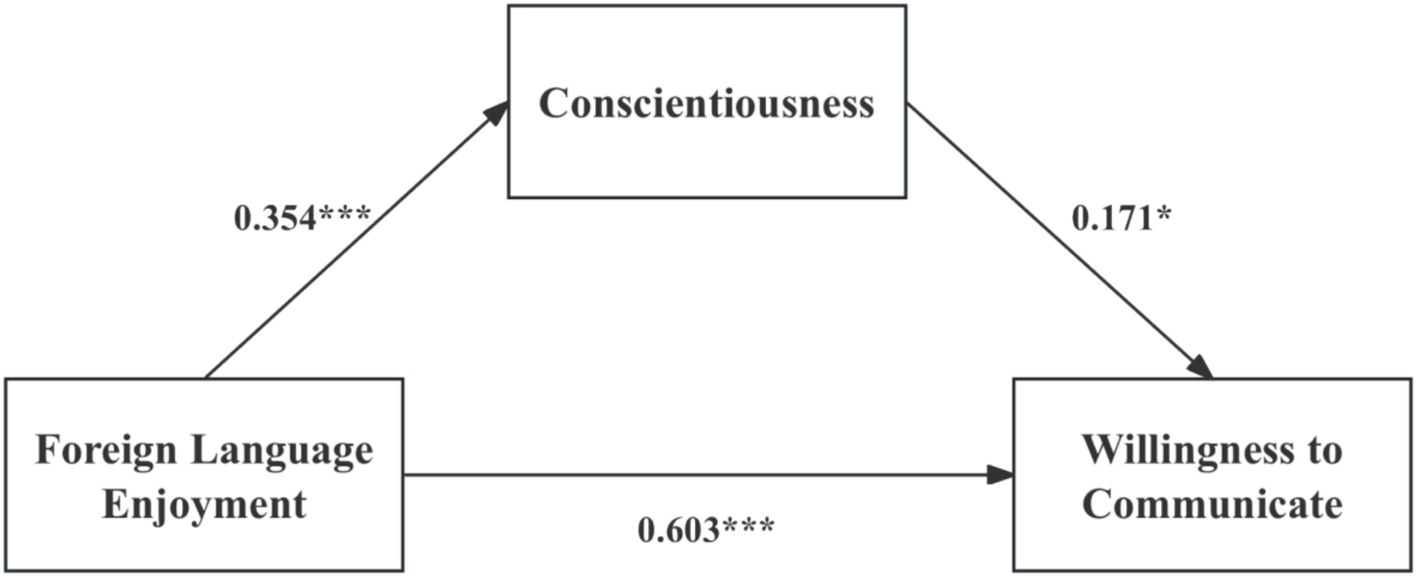

Therefore, given the theoretical underpinnings of the constructs and the existing empirical findings previously reviewed, this study hypothesized a mediating model of WTC in the link between FLE and Conscientiousness in the classroom context. Along with the path directions, the proposed model was depicted in Figure 2. The subsequent hypotheses were suggested as follows based on the preceding rationale:

Hypothesis 1: FLE positively predicts WTC.

Hypothesis 2: Conscientiousness positively predicts WTC.

Hypothesis 3: FLE positively predicts Conscientiousness.

Hypothesis 4: FLE has a positive influence on WTC through the mediating role of Conscientiousness.

3 Methodology

3.1 Participants

Employing a convenience sampling approach, this study enrolled 244 first-year to second-year Chinese EFL undergraduate students to explore their WTC, FLE, and Conscientiousness. Of these participants, 180 (74%) were female, and 64 (26%) were male; 176 (72%) were freshmen, and 68 (28%) were sophomores; 140 (57%) were from South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, and 104 (43%) were from Guangdong Ocean University (Yangjiang Campus) in Yangjiang. Undergraduate students from two different stages were targeted to capture both WTC and affective feelings to varying degrees. Along with the fact that South China Agricultural University is recognized as a key university compared with Guangdong Ocean University (Yangjiang Campus), this study also aimed to ensure sample diversity and avoid the potential common method bias that could arise from distributing questionnaires to a specific university.

3.2 Instruments

The data were collected by a three-construct composite questionnaire, along with a demographic information section. Since the survey was conducted in a Chinese EFL context, the questionnaire, originally developed in English, was translated into Chinese. This translated version of the three-construct composite questionnaire underwent three rounds of review and revision by both authors and an associate professor with a Ph.D. in applied linguistics, focusing on enhancing the clarity and adaptability of the items for Chinese EFL undergraduate students. The three scales are as follows.

3.2.1 WTC in English scale

A 10-item scale from Peng and Woodrow (2010), initially developed by Weaver (2005), was used to measure students’ WTC in English. This scale comprises two dimensions: WTC in meaning-focused and form-focused activities. Each item was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score on this scale suggests that the student is more willing to communicate in English.

3.2.2 Foreign language enjoyment scale

The students’ FLE in learning English was gauged by a 10-item scale (Jiang and Dewaele, 2019), originally from Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014). This scale encompasses the social and private enjoyment of learners in the classroom. The participants rated each statement on a scale of 1, representing “strongly disagree,” to 5, representing “strongly agree.” A higher score reflects a higher level of enjoyment in learning English.

3.2.3 Conscientiousness scale

Conscientiousness was tapped using six items from the sub-scales of IPIP-NEO-60 scale (Maples-Keller et al., 2017), which is a representation of 300-item IPIP-NEO (Goldberg et al., 2006) from the International Personality Item Pool, measuring five personality traits: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. The 6-item scale assesses facets of the participants’ Conscientiousness, including Orderliness, Achievement Striving, and Cautiousness. A higher score indicates that the respondent is more conscientious.

3.3 Procedure for data collection

Data collection was conducted in May 2024, and it took 21 days to gather all the data. The questionnaire was distributed online via Wenjuanxing1 an online survey platform with the assistance of two instructors from two universities. Before distribution, all students were informed that participation in the survey was voluntary and were asked to read a separate consent form to ensure that they were fully well-informed about the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. All questionnaire items were set to the mandatory fill-in mode; thus, this research had no missing data.

3.4 Data analysis

This study employed SPSS 29.0, along with the accompanying PROCESS macro version 4.1, to analyze the data. In the first phase, descriptive statistics for all latent constructs were calculated to present an overview of the dataset, including distribution, mean, and standard deviation. Then, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), with principal component factoring (PCF) analysis and varimax rotation, was conducted to assess the internal structure of each scale. Following this, the convergent and discriminant validity of the variables was verified using the indices of Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and the square roots of AVE, which further ensured that all prerequisites for subsequent analyses were met (Hair et al., 2019). To this end, four hypotheses were tested using the PROCESS macro with the Bootstrapping technique, one of the most effective and recently developed programs in testing mediation (Lan et al., 2023; Hayes, 2022). This method, yielding bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, was used to examine the significance of mediation effects by generating 5,000 Bootstrap samples (Hayes, 2022).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive analysis

The skewness (ranging from −0.395 to 0.275) and kurtosis (ranging from −0.603 to 0.657) of all 26 items were computed in the descriptive analysis. For all latent constructs, skewness values lower than ±2 and kurtosis values lower than ±7 suggested the normal distribution of the gathered data in this study (Finney and DiStefano, 2006).

4.2 Reliability and validity of the research instruments

At the beginning, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was performed to ensure that the data were appropriate to the EFA. Bartlett’s test of sphericity for all three constructs was significant (p < 0.001), and the KMO values ranged from 0.593 to 0.867, indicating the suitability of the data for conducting the EFA to assess the dimensional structure. Given the benchmark that items with eigenvalues greater than 1 and standardized factor loadings above 0.60 were retained (Hair et al., 2019), 22 items were selected from the original composite questionnaire.

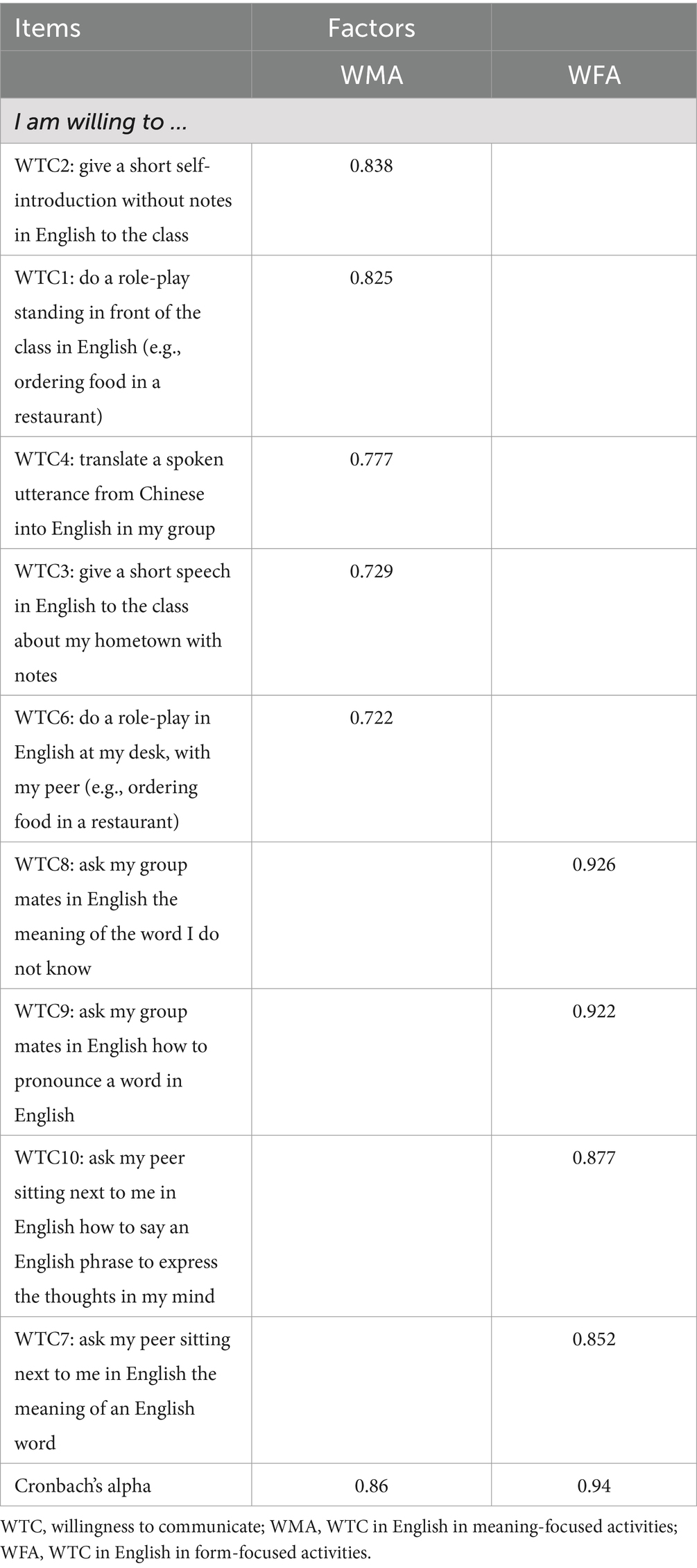

Next, as can be seen from Table 1, two dimensions were extracted, and item 5 was eliminated due to its low factor loading. The nine remaining items, with no cross-loading greater than 0.40, explained 73.22% of the total variance, which aligned well with the initial dimensions of the WTC scale. The first factor represented students’ WTC in meaning-focused activities within the classroom context (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), while the second factor reflected the students’ WTC in English pertained to form-focused activities (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

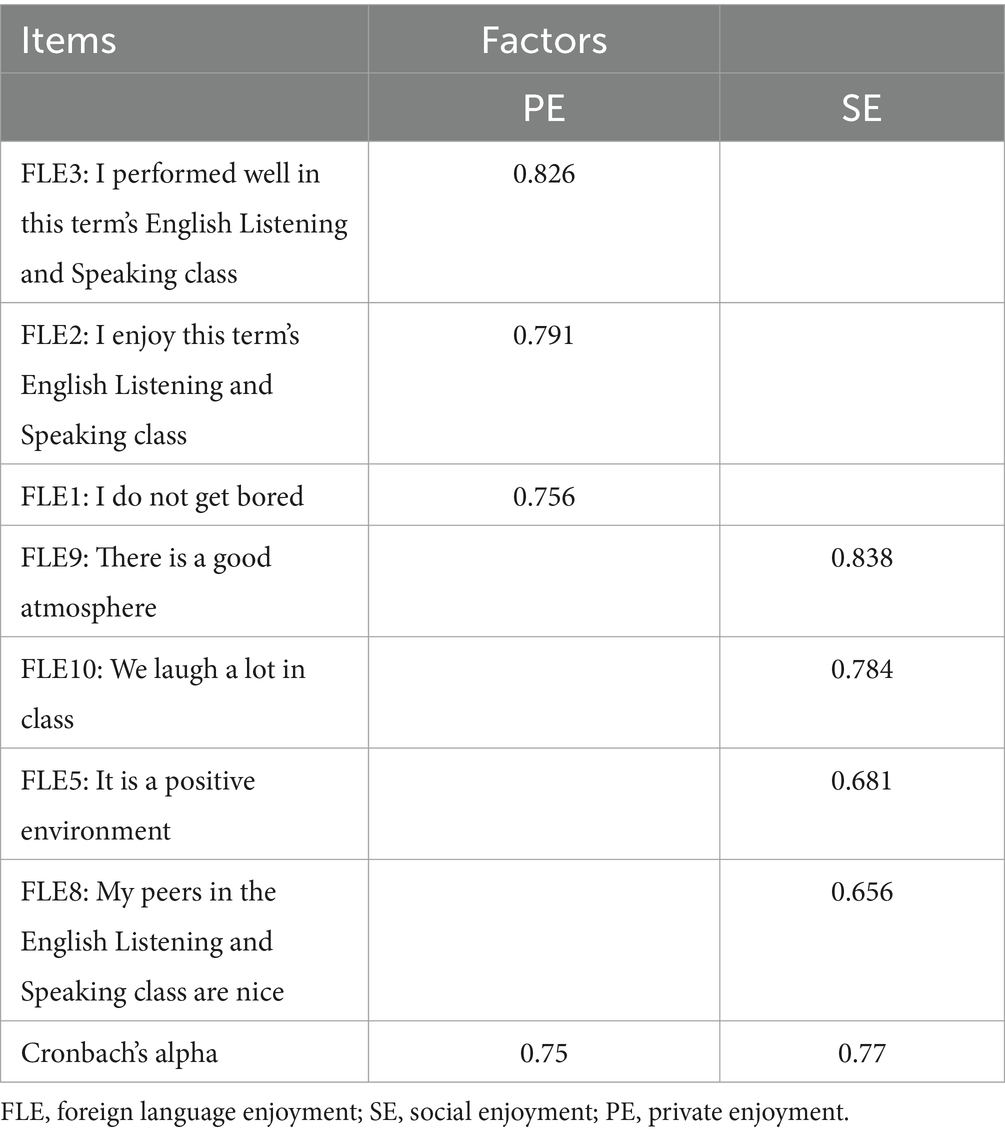

After that, as shown in Table 2, the EFA yielded a two-dimensional structure for the scale of FLE, which accounted for 63.88% of the total variance. Item 4 and 7 were removed due to their cross-loadings exceeding 0.40, while item 6 was eliminated as a result of its low factor loading. The first factor reflected the students’ private enjoyment of English lessons (Cronbach’s α = 0.75), and the second factor represented their social enjoyment from interactions with classmates and the English teacher (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

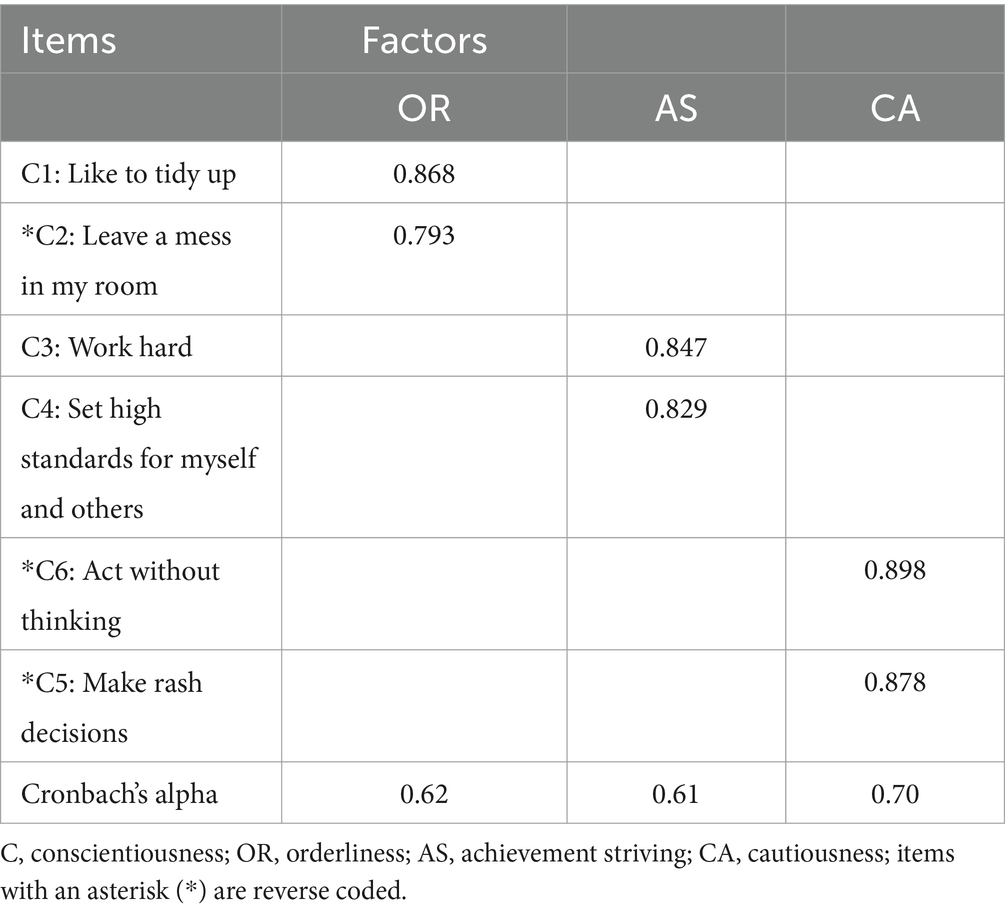

Then, Table 3 illustrates that a three-factor structure was produced by the EFA for the Conscientiousness scale, accounting for 77.63% of the total variance, which was consistently in line with the initial design of the scale’s dimensions. The three facets explained Conscientiousness from distant perspectives, including orderliness (Cronbach’s α = 0.62), achievement striving (Cronbach’s α = 0.61), and cautiousness (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

Based on the results from the EFA presented in Tables 1–3, the standardized factor loadings and the internal consistency of the items for the WTC, FLE, and Conscientiousness scales all met the acceptable or recommended criterion (Hair et al., 2019). Consequently, the convergent and discriminant validity of the research instruments were evaluated.

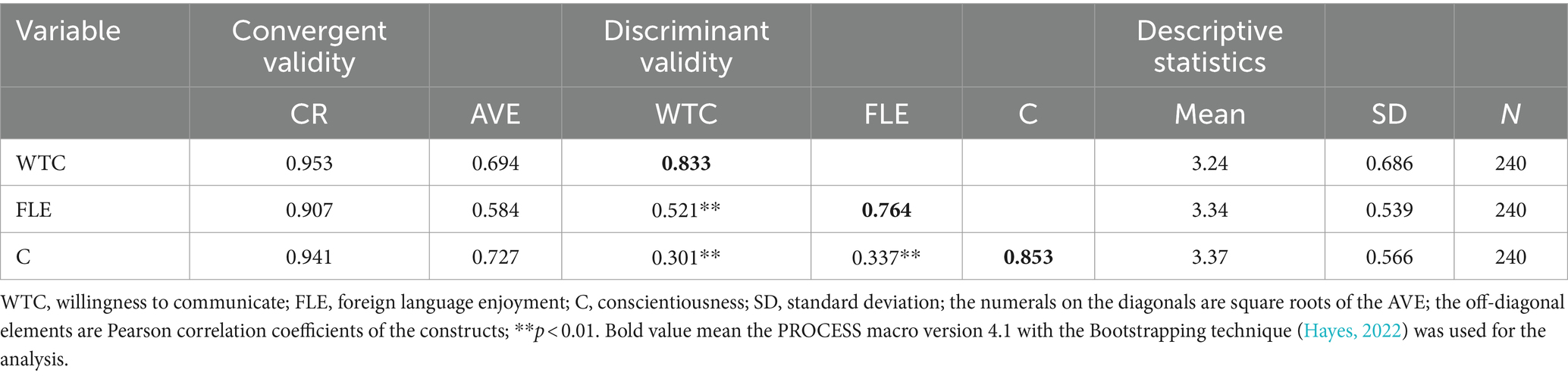

As reported in Table 4, the findings indicated solid convergent validity of all constructs, with composite reliability (CR) exceeding 0.70 and average variance extracted (AVE) exceeding 0.50. Additionally, the square roots of the AVE for each variable (see the numerals on the diagonals in Table 4) were greater than their corresponding Pearson correlation coefficients, thus fulfilling the criterion for discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the correlations among the variables were computed (see Table 4), revealing that all the constructs were significantly inter-correlated. Specifically, the results indicated that students’ WTC was positively correlated with their FLE (r = 0.521, p < 0.01) and Conscientiousness (r = 0.301, p < 0.01). In the same vein, FLE was also positively correlated with Conscientiousness (r = 0.337, p < 0.01).

4.3 The results of the research hypotheses

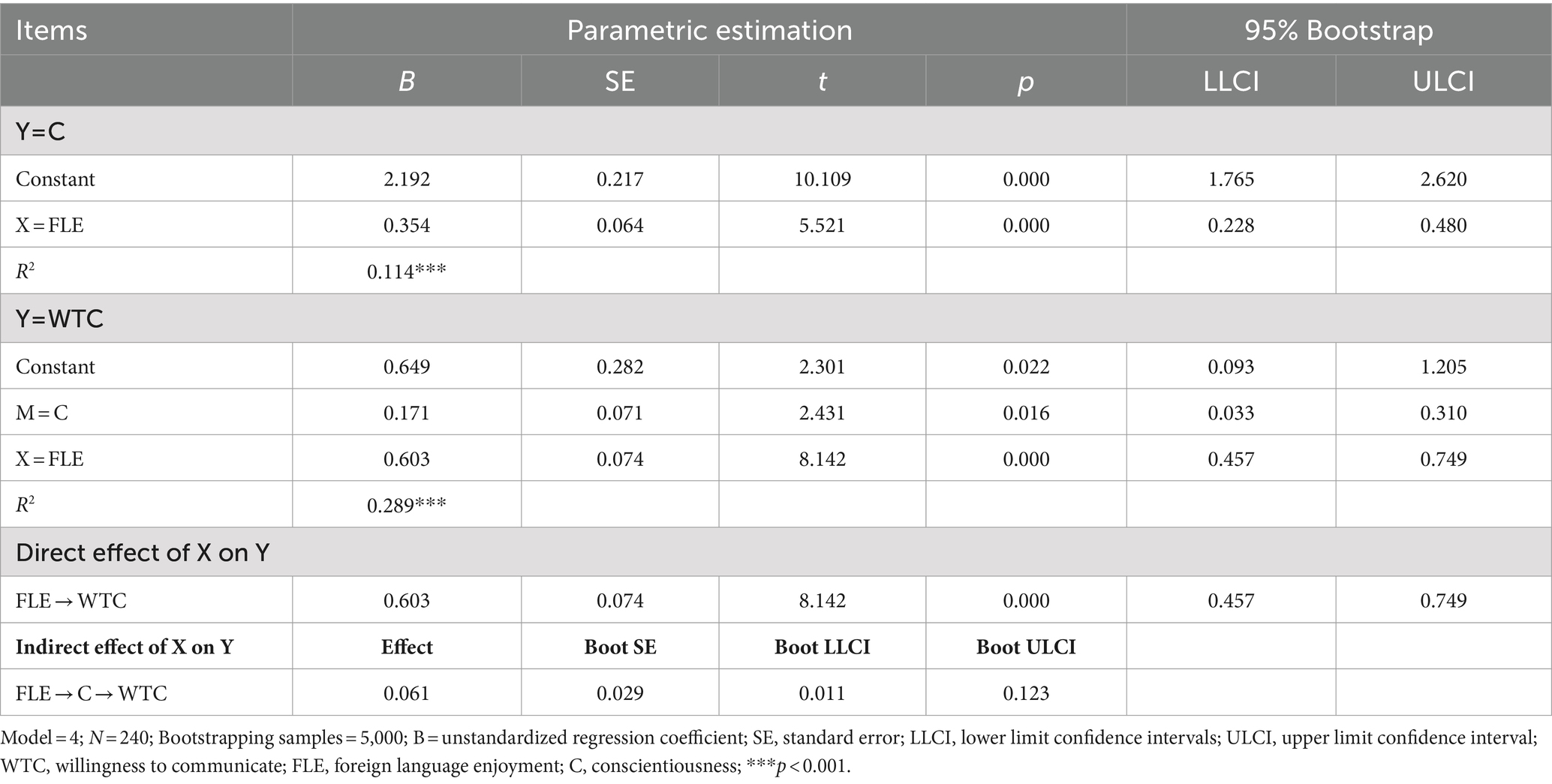

After confirming that all prerequisites were fit for the following analyses, the PROCESS macro with the Bootstrapping technique was employed to test all the hypotheses put forward previously. First, as can be seen in Table 5, the results confirmed Hypothesis 3. The path leading from FLE to Conscientiousness was statistically significant (β = 0.354, p < 0.001). This result indicated that the variable FLE was positively correlated with Conscientiousness, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3.

Following this, the path from FLE to WTC (β = 0.603, p < 0.001) and the path from Conscientiousness to WTC (β = 0.171, p < 0.05) were also examined to be statistically significant, substantiating Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. These findings verified the positive predictability of both FLE and Conscientiousness on WTC.

In addition, based on the rule that a mediation effect was considered significant if zero did not straddle between the lower and upper bounds (Hayes, 2022), the indirect effect in the nexus FLE → C → WTC was statistically significant (β = 0.061, 95% Boot CI = 0.011 to 0.123), indicating that Conscientiousness mediated the relationship between FLE and WTC (see Figure 3). This finding provided empirical evidence validating Hypothesis 4. As the direct effect of FLE on WTC was also significant (β = 0.603, p < 0.001), it could be concluded that the mediation effect was partial (see Little et al., 2007, p. 210).

5 Discussion

The current study shed light on the associations among FLE, Conscientiousness, and WTC in an EFL context in China. The Bootstrapping method was employed to verify the mediation effect within the three-variable model and to confirm the initial four hypotheses. Regarding Hypothesis 1, a significantly positive link was found between FLE and WTC. This is in line with the findings of a substantial body of research, including studies by Lee et al. (2021), Cao (2022), and Zhang et al. (2024), which found FLE an important positive emotion affecting WTC. EFL students who experience a higher level of enjoyment are more inclined to engage in English language communication (Lan et al., 2023). As a non-cognitive factor, the positive role of FLE in the context of the classroom has been acknowledged by a growing body of studies in academic literature (see reviews by Botes et al., 2022; Dewaele et al., 2023). This also supports the argument by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) that enjoyment might be the emotional key to unlocking the language learning potential of foreign language learners. In other words, FLE could potentially be the pivotal element that helps learners move the last step forward before actual communication to communicate.

Then, Conscientiousness was revealed to be a direct and positive predictor of WTC, thus supporting Hypothesis 2. This suggests that L2 learners who possess a more conscientious personality trait are more likely to engage in communicative interactions with their peers and the English teacher. This result partially echoes the findings of the existing studies (e.g., Zhang et al., 2023), confirming the significantly positive relationship between Conscientiousness and WTC, but it contradicts the findings of Oz (2014). According to the multilayered pyramid model (MacIntyre et al., 1998), personality traits are not regarded as absolute determinants of WTC, yet it should be noted that Conscientiousness, along with its sub-facets like Orderliness, Achievement Striving, and Cautiousness, may promote a more positive attitude toward language learning opportunities, potentially enhancing their readiness to engage in L2 communication (Krashen, 1981).

Concerning Hypothesis 3, FLE was indicated to positively predict Conscientiousness, indicating that students who have a higher level of enjoyment in learning a foreign language are more likely to show greater levels of Conscientiousness. While there are scant studies that have delved into this specific relationship, this present finding is partially in agreement with the main arguments of some studies pertaining to the connection between positive emotions and personality traits (e.g., Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014). However, these studies tend to emphasize the one-sided influence of learners’ personality traits on their emotions, such as FLE and FLCA, regardless of the reciprocal influence of emotions on personality traits. This finding also contributes empirical evidence to the Broaden-and-Build Theory developed by Fredrickson (2001). Based on this theory, we can argue that EFL learners who are more enjoyable in the classroom settings, are more likely to be positively influenced in the development of Conscientiousness as a valuable personality trait.

In addition, FLE affected WTC indirectly through the mediating role of Conscientiousness (FLE → C → WTC), supporting Hypothesis 4. This is in line with the theoretical perspective that positive emotions play a role in shaping behavior and personal development (Fredrickson, 2004). As WTC was considered a key variable in enhancing foreign language oral proficiency, we might argue that L2 learners inclined to enjoy the English learning process from both private and social perspectives are likely to develop a more conscientious attitude toward English courses and be more willing to proactively initiate interactions with others in English. Furthermore, the conceptual framework of WTC might explain the results of this study (see Figure 1), which indicates that FLE, as an affective variable in the fifth layer, and Conscientiousness, as a personality trait in the sixth layer, affected WTC in an inter-correlated way.

6 Conclusion and implications

The present study examined the positive predictability of FLE and Conscientiousness on WTC in the mediation English language learning model. The findings indicated that Conscientiousness mediated the link between FLE and WTC, which could be elucidated from three perspectives. First, FLE has a significantly positive influence on Conscientious. Second, Conscientiousness was a positive predictor of WTC. Third, FLE also has a direct impact on WTC. Taken together, these results highlighted the critical role of the dynamic interplay of non-cognitive factors, including positive emotions and personality traits, in fostering the willingness to communicate among Chinese EFL learners. These findings not only enriched the existing literature on the relationship among these variables but also provided notable implications for EFL educators. To regard the key predictive effect of FLE in affecting WTC directly, L2 educators are suggestive of concentrating on fostering a playful and delightful classroom environment to stimulate students’ willingness to engage in English communication (Fredrickson, 2001). From the social perspective, as part of the two-factor structure of FLE, teachers are recommended to make group work engaging for learners by developing intriguing activities and strategically assigning group members based on their preferences or individual differences. This can enhance EFL participants’ enjoyment of interactions with classmates, which in turn increases their WTC. In addition, strengthening the teacher-student relationship through a range of supportive feedback (Rosiek and Beghetto, 2009), such as teacher-written feedback and online peer feedback, might also encourage students to proactively seek assistance from the English teacher and peers using the English language when they face difficulties.

At the individual level, learners’ FLE and WTC are primarily related to the relevance of lesson topics. Therefore, curriculum developers can incorporate more practical and current topics into the English learning curriculum. This can be achieved by blending traditional textbooks with online learning resources (Yu et al., 2022) and enhanced through computer-assisted techniques, like QR code scanning for additional information. Following Dewaele and Saito (2024), educators should also focus on students’ attitudes toward foreign language learning, guiding them to recognize the usefulness of English as a global lingua franca (Wang et al., 2024). This said, students might naturally acquire English in a more relaxed and pleasurable environment, which can lead to a gradual increase in their willingness to get involved in spoken English tasks. This finding contributes to the empirical evidence of positive psychology in education, underlining the pivotal role of emotional factors in second language acquisition (Tsang and Dewaele, 2023).

Regarding the indirect impact of FLE on WTC in English through the mediator of Conscientiousness, teachers are recommended to leverage students’ conscientious traits by immersing them in a stress-free and low-anxiety English learning atmosphere to increase their WTC. Accordingly, English language curricula ought to be designed to aid learners in establishing explicit, attainable goals alongside the cultivation of a systematic, regular, and self-regulated learning schedule to improve their English-spoken proficiency. This recommendation aligns with the viewpoint that students whose level of conscientiousness is low may particularly need assistance from their teachers (Przybył and Pawlak, 2023). Furthermore, it should also be noted that additional investigations incorporating the non-cognitive attitude variable are required to explore how Conscientiousness shapes specific behaviors and attitudes toward English learning, ultimately affecting students’ WTC.

It is acknowledged that this study also suffers from some limitations. Firstly, the complexity and multifaceted nature of personality traits cannot be fully measured by a single self-report scale, thus potentially undermining the reliability of the gathered data. Consequently, subsequent studies employing a mixed method might be needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of conscientious behavior and the underlying mechanisms related to personality traits, FEL, and WTC. Secondly, the current study was cross-sectional, failing to assess the long-term stability of the mediation effect. Longitudinal studies are therefore recommended to examine the influence of the relatively stable personality traits (Caspi et al., 2005) on the fluctuations of WTC. In addition, convenience sampling, a nonprobability or nonrandom sampling technique, was used in the study, and only Chinese EFL students in the first and second years were included. While this nonprobability sampling is useful, especially when randomization is impossible, such as in large populations (Etikan et al., 2016), the results may not fully capture the characteristics of EFL learners in China. Thus, future studies might consider a more diverse and representative sample across various academic levels and cultural settings to enhance the generalization of the findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ZL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Alavi, S. M., Esmaeilifard, F., and Tommasi, M. (2021). The effect of emotional scaffolding on language achievement and willingness to communicate by providing recast. Cogent Psychol. 8:1911093. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2021.1911093

Alrabai, F. (2022). Modeling the relationship between classroom emotions, motivation, and learner willingness to communicate in EFL: applying a holistic approach of positive psychology in SLA research. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 45, 2465–2483. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2022.2053138

Barabadi, E., Khajavy, G. H., Booth, J. R., Rahmani Tabar, M., and Vahdani Asadi, M. R. (2022). The links between perfectionistic cognitions, L2 achievement and willingness to communicate: examining L2 anxiety as a mediator. Curr. Psychol. 42, 30878–30890. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-04114-7

Botes, E. L., Dewaele, J.-M., and Greiff, S. (2020). The power to improve: effects of multilingualism and perceived proficiency on enjoyment and anxiety in foreign language learning. Eur. J. Appl. Linguist. 8, 279–306. doi: 10.1515/eujal-2020-0003

Botes, E., Dewaele, J.-M., and Greiff, S. (2022). Taking stock: a meta-analysis of the effects of foreign language enjoyment. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 12, 205–232. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.2.3

Botes, E., Dewaele, J.-M., Greiff, S., and Goetz, T. (2023). Can personality predict foreign language classroom emotions? The devil’s in the detail. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 46, 51–74. doi: 10.1017/s0272263123000153

Burgoon, J. K. (1976). The unwillingness-to-communicate scale: development and validation. Commun. Monogr. 43, 60–69. doi: 10.1080/03637757609375916

Cao, Y. (2011). Investigating situational willingness to communicate within second language classrooms from an ecological perspective. System 39, 468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.10.016

Cao, G. (2022). Toward the favorable consequences of academic motivation and L2 enjoyment for students’ willingness to communicate in the second language (L2WTC). Front. Psychol. 13:997566. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.997566

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., and Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: stability and change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

Cheng, L., and Xu, J. (2022). Chinese English as a foreign language Learners’ individual differences and their willingness to communicate. Front. Psychol. 13:883664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883664

Costa, P. T., McCrae, R. R., and Dye, D. A. (1991). Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: a revision of the NEO personality inventory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 12, 887–898. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(91)90177-d

Csikszentmihalyi, M., and Csikzentmihaly, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience, vol. 1990. New York: Harper & Row, 1.

Dewaele, J. M., and Dewaele, L. (2018). Learnerinternal and learner-external predictors of willingness to communicate in the FL classroom. J. Europ. Sec. Langu. Assoc. 2, 24–37. doi: 10.22599/jesla.37

Dewaele, J.-M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 237–274. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewaele, J. M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2016). Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: the right and left feet of the language learner. In: Positive psychology in SLA, 215, 9781783095360–9781783095010.

Dewaele, J. M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2019). “The predictive power of multicultural personality traits, learner and teacher variables on foreign language enjoyment and anxiety” in Evidence-based second language pedagogy. (Abingdon, UK: Routledge), 263–286.

Dewaele, J.-M., and Pavelescu, L. M. (2019). The relationship between incommensurable emotions and willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language: a multiple case study. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 15, 66–80. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2019.1675667

Dewaele, J.-M., and Saito, K. (2024). Are enjoyment, anxiety and attitudes/motivation different in English foreign language classes compared to LOTE classes? Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 14, 171–191. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.42376

Dewaele, J.-M., Saito, K., and Halimi, F. (2023). How foreign language enjoyment acts as a buoy for sagging motivation: a longitudinal investigation. Appl. Linguis. 44, 22–45. doi: 10.1093/applin/amac033

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., and Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 5, 1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Fathi, J., Pawlak, M., Mehraein, S., Hosseini, H. M., and Derakhshesh, A. (2023). Foreign language enjoyment, ideal L2 self, and intercultural communicative competence as predictors of willingness to communicate among EFL learners. System 115:103067. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2023.103067

Fatima, I., Ismail, S. A. M. M., Pathan, Z. H., and Memon, U. (2020). The power of openness to experience, extraversion, L2 self-confidence, classroom environment in predicting L2 willingness to communicate. Int. J. Instr. 13, 909–924. doi: 10.29333/iji.2020.13360a

Finney, S. J., and DiStefano, C. (2006). “Structural equation modeling” in Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. ed. R. C. Serlin (Charlotte, NC, the United States: Information Age Publishing), 269–315.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 359, 1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Friedrich, T. S., and Schütz, A. (2023). Predicting school grades: can conscientiousness compensate for intelligence? J. Intelligence 11:146. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence11070146

Gkonou, C., Daubney, M., and Dewaele, J. M. (2017). New insights into language anxiety: theory, research and educational implications, vol. 114. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., et al. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. J. Res. Person. 40, 84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007

Guo, Y., Wang, Y., and Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). The impact of blended learning-based scaffolding techniques on learners’ self-efficacy and willingness to communicate. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras 40, 253–273. doi: 10.30827/portalin.vi40.27061

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. 8th Edn. Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. 3rd Edn: The Guilford Press.

Jiang, Y., and Dewaele, J. M. (2019). How unique is the foreign language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? Sys. 82, 13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.02.017

Kang, S. J. (2005). Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System 33, 277–292. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2004.10.004

Karadağ, Ş., and Kaya, S. D. (2019). The effects of personality traits on willingness to communicate: a study on university students. MANAS Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 8, 397–410. doi: 10.33206/mjss.519145

Katić, M., and Šafranj, J. (2019). The relationship between big five personality traits and willingness to communicate. Педагошка стварност 65, 69–81. doi: 10.19090/ps.2019.1.69-81

Khajavy, G. H., MacIntyre, P. D., and Barabadi, E. (2018). Role of the emotions and classroom environment in willingness to communicate. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 40, 605–624. doi: 10.1017/s0272263117000304

Khany, R., and Nejad, A. M. (2016). L2 willingness to communicate, openness to experience, extraversion, and L2 unwillingness to communicate: the Iranian EFL context. RELC J. 48, 241–255. doi: 10.1177/0033688216645416

King, J., and Harumi, S. (2020). “East Asian perspectives on silence in English language education” in Multilingual Matters, vol. 6.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Lalonde, R. N., and Gardner, R. C. (1984). Investigating a causal model of second language acquisition: where does personality fit? Cana. J. Behav. Sci. 16, 224–237. doi: 10.1037/h0080844

Lan, G., Zhao, X., and Gong, M. (2023). Motivational intensity and willingness to communicate in L2 learning: A moderated mediation model of enjoyment, boredom, and shyness. System 117:103116. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2023.103116

Lee, J. S. (2020). The role of grit and classroom enjoyment in EFL learners’ willingness to communicate. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 43, 452–468. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2020.1746319

Lee, J. S., and Lee, K. (2020). Role of L2 motivational self system on willingness to communicate of Korean EFL university and secondary students. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 49, 147–161. doi: 10.1007/s10936-019-09675-6

Lee, J. S., Xie, Q., and Lee, K. (2021). Informal digital learning of English and L2 willingness to communicate: roles of emotions, gender, and educational stage. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 45, 596–612. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2021.1918699

Li, C., Jiang, G., and Dewaele, J.-M. (2018). Understanding Chinese high school students’ foreign language enjoyment: validation of the Chinese version of the foreign language enjoyment scale. System 76, 183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.06.004

Li, S., Wu, H., and Wang, Y. (2024). Positive emotions, self-regulatory capacity, and EFL performance in the Chinese senior high school context. Acta Psychol. 243:104143. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104143

Little, T. D., Card, N. A., Bovaird, J. A., Preacher, K. J., and Crandall, C. S. (2007). “Structural equation modeling of mediation and moderation with contextual factors” in Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. eds. T. D. Little, J. A. Bovaird, and N. A. Card (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 207e230.

Liu, G. Z., Fathi, J., and Rahimi, M. (2024). Using digital gamification to improve language achievement, foreign language enjoyment, and ideal L2 self: a case of English as a foreign language learners. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 40, 1347–1364. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12954

MacIntyre, P. (2020). Expanding the theoretical base for the dynamics of willingness to communicate. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 10, 111–131. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2020.10.1.6

MacIntyre, P. D., and Charos, C. (2016). Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 15, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0261927x960151001

MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., and Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: a situated model of confidence and affiliation. Mod. Lang. J. 82, 545–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x

MacIntyre, P., and Gregersen, T. (2012). “Affect: the role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learning” in Psychology for language learning: Insights from research, theory and practice (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 103–118.

MacIntyre, P. D., and Legatto, J. J. (2011). A dynamic system approach to willingness to communicate: developing an idiodynamic method to capture rapidly changing affect. Appl. Linguis. 32, 149–171. doi: 10.1093/applin/amq037

MacIntyre, P. D., and Mercer, S. (2014). Introducing positive psychology to SLA. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 153–172. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.2

MacIntyre, P. D., Wang, L., and Khajavy, G. H. (2020). Thinking fast and slow about willingness to communicate: A two-systems view. Eur. J. Appl. Linguist. 6, 443–458. doi: 10.32601/ejal.834681

Maples-Keller, J. L., Williamson, R. L., Sleep, C. E., Carter, N. T., Campbell, W. K., and Miller, J. D. (2017). Using Item Response Theory to Develop a 60-Item Representation of the NEO PI–R Using the International Personality Item Pool: Development of the IPIP–NEO–60. J. Person. Assessm. 101, 4–15. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2017.1381968

McAbee, S. T., and Oswald, F. L. (2013). The criterion-related validity of personality measures for predicting GPA: a Meta-analytic validity competition. Psychol. Assess. 25, 532–544. doi: 10.1037/a0031748

McCroskey, J. C., and Baer, J. E. (1985). Willingness to communicate: the construct and its measurement. In: Paper presented at the annual meeting of the speech communication association. Denver, CO: ERIC document reproduction service. No. ED265604.

Minnigh, T. L., Sanders, J. M., Witherell, S. M., and Coyle, T. R. (2024). Grit as a predictor of academic performance: not much more than conscientiousness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 221:112542. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2024.112542

Nematizadeh, S., and Wood, D. (2021). “Second language willingness to communicate as a complex dynamic system” in New perspectives on willingness to communicate in a second language (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 7–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-67634-6_2

Oz, H. (2014). Big five personality traits and willingness to communicate among foreign language learners in Turkey. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 42, 1473–1482. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2014.42.9.1473

Pavelescu, L. M. (2023). Emotion, motivation and willingness to communicate in the language learning experience: a comparative case study of two adult ESOL learners. Lang. Teach. Res. 136216882211468. doi: 10.1177/13621688221146884

Pawlak, M., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A., and Bielak, J. (2016). Investigating the nature of classroom willingness to communicate (WTC): a micro-perspective. Lang. Teach. Res. 20, 654–671. doi: 10.1177/1362168815609615

Peng, J. E. (2020). “Willing silence and silent willingness to communicate (WTC) in the Chinese EFL classroom: a dynamic systems perspective” in East Asian perspectives on silence in English language education, 143–165.

Peng, J., and Woodrow, L. (2010). Willingness to communicate in English: a model in the Chinese EFL classroom context. Lang. Learn. 60, 834–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00576.x

Piechurska-Kuciel, E. (2018). Openness to experience as a predictor of L2 WTC. System 72, 190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.01.001

Proietti Ergün, A. L., and Ersöz Demirdağ, H. (2022). The relation between foreign language enjoyment, subjective well-being, and perceived stress in multilingual students. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 45, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2022.2057504

Przybył, J., and Pawlak, M. (2023). Personality as a factor affecting the use of language learning strategies: The case of university students. Cham, Zug, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Roberts, B. W., Lejuez, C., Krueger, R. F., Richards, J. M., and Hill, P. L. (2014). What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed? Dev. Psychol. 50, 1315–1330. doi: 10.1037/a0031109

Rosiek, J., and Beghetto, R. A. (2009). “Emotional scaffolding: the emotional and imaginative dimensions of teaching and learning” in Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives. eds. P. A. Schutz and M. Zembylas (Boston, MA, the United States: Springer), 175–194.

Sang, Y., and Hiver, P. (2021). Using a language socialization framework to explore Chinese Students’ L2 Reticence in English language learning. Linguist. Educ. 61:100904. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2021.100904

Shao, Q., and Gao, X. (2016). Reticence and willingness to communicate (WTC) of east Asian language learners. System 63, 115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2016.10.001

Spielmann, J., Yoon, H. J. R., Ayoub, M., Chen, Y., Eckland, N. S., Trautwein, U., et al. (2022). An in-depth review of conscientiousness and educational issues. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 2745–2781. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09693-2

Stewart, R. D., Mottus, R., Seeboth, A., Soto, C. J., and Johnson, W. (2022). The finer details? The predictability of life outcomes from big five domains, facets, and nuances. J. Pers. 90, 167–182. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12660

Tsang, A., and Dewaele, J. M. (2023). The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, and enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 15, 2015–2034. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2022-0077

Wang, Y., Xu, W., Guan, K., Zhao, J., and Wu, P. (2024). English teachers’ post-pandemic motivation in Macau’s higher education system. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 14, 1990–2001. doi: 10.17507/tpls.1407.05

Weaver, C. (2005). Using the Rasch model to develop a measure of second language learners’ willingness to communicate within a language classroom. J. Appl. Measur. 6, 396–415.

Xu, W., Zhang, H., Sukjairungwattana, P., and Wang, T. (2022). The roles of motivation, anxiety and learning strategies in online Chinese learning among Thai learners of Chinese as a foreign language. Front. Psychol. 13:962492. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.962492

Xu, W., and Zheng, S. (2022). Personality traits and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese university students: the moderating role of internet self-efficacy and gender. Front. Psychol. 13:779139. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.779139

Yu, X., and Ma, J. (2024). Modeling the predictive effect of enjoyment on willingness to communicate in a foreign language: the chain mediating role of growth mindset and grit. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2023.2300351

Yu, Z., Xu, W., and Sukjairungwattana, P. (2022). A meta-analysis of eight factors influencing MOOC-based learning outcomes across the world. Interact. Learn. Environ. 32, 707–726. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2022.2096641

Zhang, J., Beckmann, N., and Beckmann, J. F. (2023). More than meets the ear: individual differences in trait and state willingness to communicate as predictors of language learning performance in a Chinese EFL context. Lang. Teach. Res. 27, 593–620. doi: 10.1177/1362168820951931

Zhang, Z., Liu, T., and Lee, C. B. (2021). Language learners’ enjoyment and emotion regulation in online collaborative learning. System 98:102478. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102478

Zhang, Q., Song, Y., and Zhao, C. (2024). Foreign language enjoyment and willingness to communicate: the mediating roles of communication confidence and motivation. System 125:103346. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2024.103346

Keywords: willingness to communicate, foreign language enjoyment, conscientiousness, personality traits, English as a foreign language

Citation: Zhao J, Guan K, Feng Y and Liu Z (2024) The effect of foreign language enjoyment on willingness to communicate among Chinese EFL students: conscientiousness as a mediator. Front. Educ. 9:1473649. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1473649

Edited by:

Priscilla Roberts, University of Saint Joseph, Macao SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Zhao, Guan, Feng and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kaining Guan, a2FpbmluZ2dAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Jin Zhao

Jin Zhao Kaining Guan1*

Kaining Guan1* Ziqing Liu

Ziqing Liu