95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 09 October 2024

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1473353

Introduction: Native speakerism has a profound influence on many aspects of ELT, for example negatively affecting job opportunities of those perceived as ‘non-native speakers’. Nevertheless, little is known about the effect of native speakerism on the recruitment of course book authors (CBAs).

Methods: Therefore, this study analysed the linguistic and ethnic representation of 161 CBAs of 77 business English business English and English for specific purposes English for Specific Purposes course books (CBs) published globally by Pearson, OUP, CUP, Macmillan and NGL.

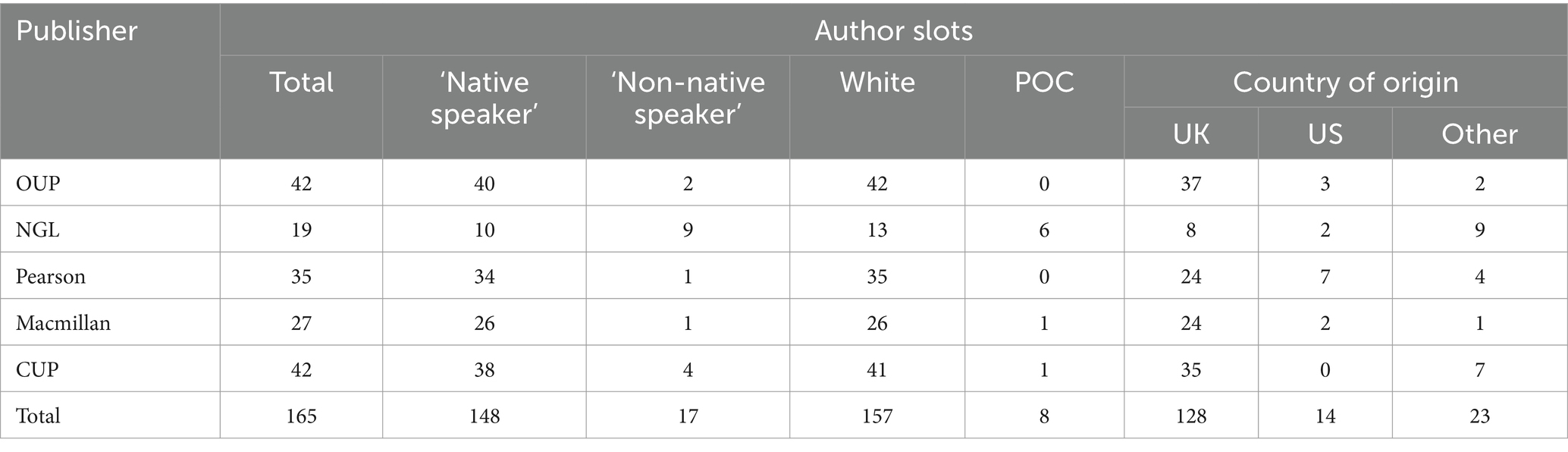

Results: The data clearly show that publishers tend to hire white ‘native speakers’ from the UK as CBAs. More specifically, 90% of all CBA slots were taken by ‘native speakers’, 95% by white CBAs, and 78% by CBAs from the UK.

Discussion: This indicates a profound native speakerist bias among publishers against not only ‘non-native speakers’, but also those ‘native speakers’ who are not white or do not come from the UK. It is thus suggested that business English and English for Specific Purposes publishers pay greater attention to the diversity of the author teams they hire.

Native speakerism can be defined as an ideology which places those perceived as ‘native speakers’ as superior both linguistically, culturally and pedagogically to those perceived as ‘non-native speakers’ (Holliday, 2005, 2006). The word perceived is emphasized here because who is regarded as a ‘native’ or a ‘non-native speaker’ in ELT is highly subjective and ideological (Aboshiha, 2015). For example, those ‘native speakers’ of English who are not white might not be perceived as ‘native speakers’ and may thus suffer similar discrimination that many ‘non-native speakers’ do (Esch et al., 2020; Rivers and Ross, 2013; Ruecker and Ives, 2015). In addition, despite several book-length attempts to define the concept of the ‘native speaker’, it still remains fairly elusive (Davies, 1991, 2003, 2013).

Nevertheless, it is clear that those perceived as ‘native speakers’, which often means those L1 English users who are white, Western-looking and come from an Inner Circle country (Kachru, 1983), that is a country where English has been spoken as a mother tongue for a considerable amount of time, such as the UK or the US, have numerous unfair advantages in the profession. For example, Kiczkowiak and Lowe (2021) showed that ‘native speakers’ and white speakers predominate as plenary speakers at ELT conferences in the EU. Moreover, research has demonstrated that recruiters prefer hiring ‘native speakers’ (Kiczkowiak, 2020; Mahboob and Golden, 2013; Selvi, 2010). This can go as far as discriminating against people of color (Park, 2012) and rejecting applicants because of ‘non-Western’ names (Ali, 2009). There is also some evidence showing that students have a preference for ‘native speakers’ and standard ‘native speaker’ accents (Cheung and Braine, 2007; Kiczkowiak, 2019; Levis et al., 2017), although this bias is less visible when students do not know their teacher’s ‘nativeness’ or are unable to identify their accent as ‘native’ or ‘non-native’ (Aslan and Thompson, 2016; Scales et al., 2006; Watson Todd and Pojanapunya, 2009). This can lead to unequal job opportunities and feelings of inferiority among those perceived as ‘non-native speakers’ (Bernat, 2008; Lowe and Kiczkowiak, 2016).

Nevertheless, while much has been stated on native speakerism and its ideological foundations as well as its impact on the L2 learners and teachers, much less is known about the effect of native speakerism on who is hired to write CBs. To date, only one study has examined the representation of ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’, and white and people of color (POC) among course book authors (CBAs) (Kiczkowiak, 2022). The study investigated 127 CBAs of 28 general English general English CB series for adults showing that 98% of all CBAs were ‘native speakers’, 97% were white, and 79% from the UK. However, it was limited to a sample of general English CBs for adults, and no study to date has analyzed this issue in business English or English for Specific Purposes CBs.

Therefore, this study aims to examine the representation of ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’, as well as white people and POC among CBAs of business English and English for Specific Purposes books published globally by OUP, CUP, NGL, Macmillan, and Pearson.

This paper shows that the vast majority of business English and English for Specific Purposes CBAs are ‘native speakers’ (90%), are white (95%), and from the UK (78%). This confirms Kiczkowiak (2022) earlier findings about general English CBs and further highlights the profound bias against POC and ‘non-native speakers’ in ELT publishing. These findings are important as they might encourage ELT publishers to rethink their author hiring process in order to address this bias. Future research can also examine to what extent this lack of diversity among the CBAs might lead to a similar lack of linguistic or ethnic diversity in the CB materials themselves.

This paper is organized as follows. The following section presents the methodology used in this study. Afterwards, the results are presented and discussed, drawing comparisons with previous literature where relevant. Finally, this paper ends by outlining some practical implications of this study and making suggestions for future research.

The ideology of native speakerism posits that those perceived as ‘native speakers’ are treated as superior in numerous aspects within ELT (Holliday, 2006, 2013). For the purposes of this paper, it is defined as a systemic ideology which has Western chauvinism at its core, is deeply ingrained in the ELT profession, and profoundly affects the lives of various ELT professionals and students. Despite the critique it has received in recent years (Kiczkowiak and Wu, 2018) and attempts from organizations to tackle it (Kamhi-Stein, 2016), it still exerts a powerful impact on ELT (Kumaravadivelu, 2016). In other words, native speakerism can be thought of as ‘common-sense’ knowledge of ‘native speaker’ linguistic, cultural and pedagogical superiority, which is often taken for granted in ELT, spread and institutionalized through various practices.

It is important to point out here that one of the core tenets of native speakerism is the objectivity of the terms ‘native’ and ‘non-native speaker’. Various studies, however, show that the terms are applied arbitrarily based on ideological and often racist notions such as skin color or even names (Aboshiha, 2015; Ali, 2009; Amin, 2004). As a result, within ELT, ‘native’ and ‘non-native speaker’ categories are socially constructed and often based on stereotypes held by others. When these terms are thus used in this paper, they are not used as objective labels, but rather as subjective and socially constructed ones, which are often based on ideological notions. To reflect this subjective and ideological nature of the terms, ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’ are placed in inverted commas.

It has been recently suggested that the terms should be abolished entirely, as to continue using them continues the perpetuation of the ideology and the discrimination resulting from it (Rudolph, 2022; Selvi et al., 2022). While in principle this argument has considerable merit, it should also be noted that in order to study a social reality in which a group of people might be discriminated against, a use of some labels, albeit ideologically laden, might be necessary. Moreover, doing away with the terms completely, even for research purposes, can lead to what has been referred to color-blind liberalism, whereby the labels are abolished in search of equality, but the discrimination continues (Kiczkowiak and Lowe 2021).

One of the areas where native speakerism is most widely visible and evidenced is ELT recruitment. Already 20 years ago researchers showed that ‘native speakers’ are preferred by ELT recruiters in the US and the UK (Clark and Paran, 2007; Mahboob, 2003). Since then, this has been confirmed in other contexts (Kiczkowiak, 2020), and ‘native speakers’ have been shown to receive higher salaries (Paciorkowski, 2021; Panaligan and Curran, 2022). Studies have also shown that recruiters often prefer ‘native speakers’ who are white and Western-looking (Rivers, 2016; Ruecker and Ives, 2015). Indeed, there are numerous accounts of POC who highlight their discrimination when seeking ELT jobs (Hashimoto, 2013; Park, 2012). Thus, in ELT recruitment a ‘native speaker’ is often idealized and perceived as a white person from the native-speaking West (Rivers and Ross, 2013).

Much less is known, however, about the recruitment of CBAs by publishers. Indeed, thus far only one study has investigated this, showing that the vast majority of general English CBAs are white ‘native speakers’ from the UK or the US (Kiczkowiak, 2022). Bearing in mind the importance of CBs in teaching English (Canale, 2021; McGrath, 2013), this is rather surprising. Therefore, this study seeks to investigate the representation of ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’, as well as POC and white people, among business English and English for Specific Purposes CBs published by NGL, OUP, Pearson, CUP and Macmillan.

First, the study focused on five publishers (OUP, CUP, NGL, Macmillan, and Pearson) as together they accounted for 56.6% of ELT market share in 2016 (Worlock, 2017). Moreover, their books are published globally, and thus the results from the analysis might more accurately reflect wider ELT trends in terms of diversity among CBAs than a sample of CBs published in one particular country. Since previous research has shed some light on this issue as far as general English CBs for adults are concerned (Kiczkowiak, 2022), it was decided that only English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs be included in this study. In addition to general English CBs, young learners, exam preparation and English for Academic Purposes CBs were also excluded from this study. Even though English for Academic Purposes might be seen as a subdomain of English for Specific Purposes, on publishers’ websites EAP CBs were classified as two separate categories. On the other hand, English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs were frequently one category in publishers’ catalogues. Finally, self-study grammar or vocabulary books, such as CUP’s Business Vocabulary in Use, were also excluded.

A total of 80 CBs were included in this study (see Table 1). The number of authors was retrieved from publishers’ websites. The years of publication were retrieved from Amazon, as in most cases they were not available on publishers’ websites. The studied CBs were published between 2020 (2 CBs) and 1994 (1 CB). Almost half of the CBs (n = 38) were published between 2020 and 2011. There were a total of 183 CBA slots distributed across the 80 CBs ranging from 11 (Business Result, OUP) to one. However, the vast majority (167) had either one or two CBA slots (Mdn = 2). Since some CBAs authored more than one CB for the same or different publishers, and since the publisher had the freedom to hire whomever they deemed qualified for the job, it was decided that CBA slots would give a better overall picture of the diversity (or lack thereof) in the studied sample rather than the number of different CBAs themselves. The full list of CBs studied here can be found in the Supplementary Appendix.

Arguably, classifying the CBAs into ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’ was one of the most challenging aspects of the project as these labels are highly contested in ELT (Dewaele et al., 2021; Holliday, 2005). This has led several scholars to completely reject them in favor of other, arguably less ideological, terms such as L1/L2/LX user (Dewaele, 2018) or expert user (Rampton, 1990). Nevertheless, since this study is concerned precisely with the ideology of native speakerism and how it might favor those perceived as ‘native speakers’ as CBAs, it seems appropriate to use the terms here with all their ideological baggage. Moreover, as previous authors have argued (Bhattacharya et al., 2019; Kiczkowiak and Lowe 2021), some crude form of labelling is necessary in order to be able to quantify the extent to which one group might be favored or discriminated.

Therefore, background information about the CBAs was gathered from publishers’ websites, social media and the Internet. In order to determine their ‘native’ or ‘non-native speaker’ status, country of origin, early education and accent were all taken into account. The classification into white and POC was based on CBAs photos available on publishers’ websites or elsewhere on the Internet. Their country of origin was similarly retrieved from the information retrieved from the Internet and social media.

Since it was not possible to gather sufficient background information on 13 CBAs to reliably determine their ‘nativeness’, ethnicity, or country of origin, they were excluded from the study. They occupied a total of 18 CBA slots, which reduced the sample to 165 slots. In addition, three CBs (English for Business: Professional English, English for the Financial Sector, and English for Business Studies 3rd Edition) were excluded from the study as they were written by individual CBAs about whom it was not possible to gather sufficient information. This reduced the number of analyzed CBs to 77.

As can be seen in Table 2, 40 out of the total of 42 CBA slots were occupied by ‘native speakers’. In fact, the two ‘non-native speaker’ slots were occupied by the same person, which means OUP hired only one ‘non-native’ CBA for the 42 potential authoring opportunities between 2020 and 2015. It should also be observed, that four ‘native speaker’ CBAs worked on two titles each (data not shown). Moreover, all OUP CBAs in this sample were white, and 37 (88%) came from the UK. This data suggests that OUP not only tends to hire as business English and English for Specific Purposes CBAs those who are ‘native speakers’, but more specifically those who are white ‘native speakers’ from the UK.

When English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs published by NGL are analyzed (see Table 3), there initially seems to be much more diversity. Out of 19 CBA slots spread over six CBs, 10 are occupied by ‘native speakers’, while nine by ‘non-native speakers’, which gives an almost equal balance between the two groups. In addition, there are six (31%) POC slots and nine slots from countries other than the UK or the US. Nevertheless, two thirds of all ‘non-native speakers’ and POC were hired on one project, which means that there were only three ‘non-native speakers’ (23%) and no POC among the remaining 13 CBA slots. In addition, it should be noted that one ‘non-native speaker’ was hired three times for three different CBs, which further reduces the diversity.

Pearson’s CBs seem to display a similar trend as those of OUP. As can be seen in Table 4, 34 (97%) out of 35 CBA slots were taken by ‘native speakers’. In addition, there was not a single POC. More than two thirds (68%) of the CBAs were from the UK, and there were only three ‘native speaker’ CBAs from countries other than the US or the UK (one from Canada and two from Ireland). There were also various CBAs, all of whom were white ‘native speakers’, who worked on more than one book. In fact, one CBA was hired on four different CBs, another one on three, while four more on two CBs each. This further reduces the diversity among the CBAs and highlights the dominance of white ‘native speaker’s from the UK as CBAs already seen in OUP CBs.

Similarly to OUP and Pearson, Macmillan also hired almost exclusively white ‘native speakers’ from the UK (see Table 5). Twenty-six out of the 27 CBA slots were taken by ‘native speakers’ and 26 by white people. In addition, 88% (n = 24) of the CBAs were from the UK. As with Pearson, there also seemed to be a tendency to hire the same ‘native speaker’ CBAs. For example, one white ‘native speaker’ was hired three times for three distinct CBs. In addition, five other white ‘native speakers’ were hired twice each. This means that almost half (48%; n = 13) of all CBA slots were taken by the same authors (data not shown), reducing the diversity among the author pool even further and leaving few opportunities for other CBAs.

The situation is very similar when business English and English for Specific Purposes CBs published by CUP are analyzed (see Table 6). 90% (n = 38) of the CBA slots are occupied by ‘native speakers’ and 98% (n = 41) by white authors. Furthermore, 83% (n = 35) of all the CBA slots were occupied by CBAs from the UK. It should also be noted that as other publishing houses, CUP tends to hire the same (white ‘native speaker’) authors repeatedly, with one author occupying three slots, and four authors occupying two slots each. This means that similarly to OUP, Pearson and Macmillan, CUP has a strong tendency to choose CBAs that are white ‘native speakers’ from the UK as authors of their English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs.

When all the CBA slots from the five analyzed publishers are taken together (see Table 7), it is clear that the vast majority were occupied not merely by ‘native speakers’ (90%), but by white authors (95%) most of whom come from the UK (78%). While it is true that NGL seems to have the most diverse group of CBAs in terms of ‘nativeness’ and skin color, it is worth highlighting that six out of nine ‘non-native speakers’ and four out of six POC worked on one specific NGL CB and where all from the same country and institution. Therefore, if this outlier was excluded from the sample, NGL’s line-up of CBAs would look very similar to those of other publishers. In addition, it would further reduce the ratio of ‘non-native speakers’ to a mere 6% and POC to 2%. The data thus clearly shows that a typical CB author of business English or English for Specific Purposes CBs is a white ‘native speaker’, typically from the UK. The data also suggests a tendency among the studied publishing houses to hire the same (white ‘native speaker’) CBAs repeatedly, thus further reducing the diversity.

Table 7. CBA slots in English for specific purposes and business English CBs published by OUP, NGL, Pearson, Macmillan and CUP.

This study is the first to analyze the extent to which native speakerism influences the hiring of English for Specific Purposes and business English CBAs. The results are very similar to those obtained by Kiczkowiak (2022), who analyzed general English CBs for adults published by the same five publishers. He found that 122 CBA slots out of a total of 126 (96%) were occupied by ‘native speakers,’ 123 (97%) by white CBAs, and 100 (79%) by CBAs from the UK. They also confirm the bias against ‘non-native speakers’ and POC prevalent in ELT recruitment (Kiczkowiak, 2022; Mahboob, 2003; Mahboob and Golden, 2013), advertising (Lengeling and Pablo, 2012; Rivers, 2016) and on the conference circuit (Kiczkowiak and Lowe 2021). Nevertheless, further research on other types of ELT CBs (e.g., young learners, EAP, locally published CBs) is needed to ascertain how widespread the preference for white ‘native speaker’ CBAs from the UK is in ELT.

It is interesting to discuss to what extent such lack of diversity among business English and English for Specific Purposes CBAs might be reflected in the content of the CBs. Bearing in mind the international aspect of business communication in English, as well as that in other English for Specific Purposes fields (e.g., tourism, aviation, medicine), a substantial amount of which (if not the majority) occurs between ‘non-native speakers’ or with at least one ‘non-native speaker’ present, it could be expected that business English and English for Specific Purposes CBAs would aim to present a diverse range of speakers and Englishes. However, various authors have observed a dominance of ‘native speakers’ in English for Specific Purposes and business English CB recordings (Franceschi, 2015; Si, 2019; Van, 2019). Van (2019), who compared tourism CBs and natural discourse occurring in tourism settings (i.e., hotels), argues that the overrepresentation of ‘native speaker’ models in some English for Specific Purposes CBs does not adequately prepare students for real-life interactions, where conversations with other ‘non-native speakers’ predominate. Nevertheless, it is difficult to ascertain to what extent the lack of linguistic and racial diversity among CBAs reflects a similar lack of diversity in the content. On the one hand, in the general English context, some commissioning editors observed that hiring primarily white ‘native speakers’ from the UK can make the CBs more Western-centric (Kiczkowiak, 2022). On the other hand, CBAs highlight that their choice of what to include in a CB, for example in terms of pronunciation, is largely dictated by the publisher (Kiczkowiak, 2021; McCarthy, 2021). Therefore, future studies could aim to not only analyze the content of CBs, but also interview CBAs and commissioning editors to gain insights into the reasons behind for example mostly including ‘native speaker’ accents.

It is also important to discuss why almost 80% of all English for Specific Purposes and business English CBAs are white ‘native speakers’ from the UK. One reason could be the market demand from students and teachers using the CBs, which is a frequently cited argument by ELT recruiters who do not hire ‘non-native speakers’ (Kiczkowiak, 2020). This was indeed mentioned by one commissioning editor in a study of general English CBs (Kiczkowiak, 2022), and there is some indication that some learners do prefer ‘native speaker’ accents (Levis et al., 2017; Walkinshaw and Duong, 2012). Nevertheless, there is no evidence whether the inclusion of ‘non-native speaker’ CBAs would in any way negatively affect the sales of CBs. Another reason could be a conscious or unconscious bias among commissioning editors, who are responsible for hiring CBAs. To date only one study has explored this among general English CBs, showing that while commissioning editors are open to hiring diverse CBAs and recognize the benefits of it, they still mostly hire white ‘native speakers’ from the UK or the US (Kiczkowiak, 2022). It is likely then that an unconscious native speakerist bias against ‘non-native speakers’ and POC is at play, as numerous studies in other disciplines have shown (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2003; Oreopoulos and Dechief, 2012). It is also possible that there are very few POC or ‘non-native speakers’ who are CBAs, or who are sufficiently skilled or knowledgeable to become one. Indeed, some commissioning editors have observed that the ELT CA group is predominantly made up of white ‘native speakers’ (Kiczkowiak, 2022). This could explain why some white ‘native speakers’ are hired repeatedly as CBAs to write various CBs, while ‘non-native speakers’ and POC are rarely recruited at all. Future studies should, however, aim to determine the baseline representation of POC and ‘non-native speakers’ among CBAs to validate this claim.

This study is the first to analyze the representation of ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’, as well as POC and white people, among CBAs of English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs published by Pearson, OUP, CUP, Macmilan and NGL. It showed not only that the vast majority of CBAs are ‘native speakers’ (90%), but also that they are white (95%) and from the UK (78%). These results match very well those obtained by Kiczkowiak (2022), who examined the ‘nativeness’ and race of general English CBAs, the only other study on this topic to date. They also corroborate numerous other studies which show the discrimination in ELT hiring policies against those perceived as ‘non-native speakers’ (Kiczkowiak, 2020; Mahboob and Golden, 2013; Selvi, 2010).

One important limitation of this study is that it did not seek to analyze the content of the selected CBs. As a result, even though numerous studies show that the content of some English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs is rather ‘native speaker’ and Western centric English for Specific Purposes business English (Franceschi, 2015; Si, 2019; Van, 2019), it is unclear how this bias originates. Interviews with CBAs suggest that this might be due to publisher’s or commissioning editor’s demands (Kiczkowiak, 2021). Nevertheless, it is suggested larger scale studies are conducted on the content of CBs, for example utilizing natural language processing (Li et al., 2020). In addition, future research could aim to interview a greater number of CBAs or commissioning editors to better understand if and how the lack of diversity among CBAs influences the content of the books.

There are also several other limitations which should be taken into account. First, this study only analyzed authors of English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs published by five publishers. While they do represent a substantial proportion of the English for Specific Purposes and business English CB market due to the global outreach of publishing houses such as OUP or CUP studied here, they certainly are not representative of all English for Specific Purposes and business English materials, nor of other types of course books, such as those for young learners. Therefore, future research could focus on ‘nativeness’ and race of English for Specific Purposes and business English CBs published more locally by other publishers, as well as other types of course books, for example for young learners. In addition, this study did not seek to interview those responsible for hiring CBAs, such as commissioning editors. Although Kiczkowiak (2022) highlighted the difficulty in including commissioning editors in a study on general English CBs, due to for example challenges in identifying their names or contact details or unwillingness to participate, other researchers should aim to qualitative research involving commissioning editors’ or representatives of the publishing houses responsible for hiring CBAs to gain insights into the reasons why most CBAs hired seem to be white ‘native speakers’. Such study could also provide an opportunity to design an appropriate recruitment protocol that would allow publishers to hire more diverse CBA teams. Finally, the classification of CBAs into the different groups was done by the researcher based on publicly available information, which can be inaccurate and potentially misinterpreted. While such methodology has been successfully employed in previous studies (Kiczkowiak and Lowe, 2021; Kiczkowiak, 2022), future studies could ask participants to self-identify as for example ‘native speakers’ or POC.

The results of this study have an important practical implication for publishers. The data clearly shows that most English for Specific Purposes and business English CBAs are white ‘native speakers’ from the UK. This does not reflect the diversity of the English language and its users. It thus seems important that publishers hire more diverse CBA teams. This could be achieved through the process of blind hiring, which has been shown in numerous other disciplines to foster impartiality and lead to more diversity (Goldin and Rouse, 2000; Neumark, 2021). Since no research thus far has examined the effect of blind hiring in ELT, it is suggested that future studies examine its potential for dealing with native speakerism. In addition, compiling a list of potential ‘non-native’ and ‘non-white’ CBAs that could be used by publishers when hiring might be helpful. However, as Kiczkowiak and Lowe (2021) observe, this would have to be done with care to avoid excluding or stereotyping authors based on race or L1. Finally, the very fact of reporting inequalities can help bring them into spotlight and thus potentially lead to greater equality, as argued by other researchers (Bhattacharya et al., 2019; Gerull et al., 2020).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

MK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1473353/full#supplementary-material

Aboshiha, P. (2015). “Rachel’s story: development of a ‘native speaker’ English language teacher” in (En)countering native-speakerism. eds. A. Swan, P. Aboshiha, and A. Holliday (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 43–58.

Ali, S. (2009). “Teaching English as an international language (EIL) in the Gulf corporation council (GCC) countries: the Brown Man’s burden” in English as an international language: Perspectives and pedagogical issues. ed. F. Sharifan (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 34–57.

Amin, N. (2004). “Nativism, the native speaker construct, and minority immigrant women teachers of English as a second language” in Learning and teaching from experience. Perspectives on nonnative English-speaking professionals. ed. L. D. Kamhi-Stein (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press), 61–80.

Aslan, E., and Thompson, A. S. (2016). Are they really “two different species”? Implicitly elicited student perceptions about NESTs and NNESTs. TESOL J. 8, 277–294. doi: 10.1002/tesj.268

Bernat, E. (2008). Towards a pedagogy for empowerment: the case of ‘impostor syndrome’ among pre-service non-native speaker teachers in TESOL. English Lang. Teach. Educ. Develop. J.l 11, 1–8.

Bertrand, M., and Mullainathan, S. (2003). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination (working paper no. 9873; working paper series). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bhattacharya, U., Jiang, L., and Canagarajah, S. (2019). Race, representation, and diversity in the American Association for Applied Linguistics. Appl. Linguis. 41, 1–7. doi: 10.1093/applin/amz003

Canale, G. (2021). The language textbook: representation, interaction & learning: conclusions. Lang. Cult. Curric. 34, 199–206. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2020.1797081

Cheung, L. Y., and Braine, G. (2007). The attitudes of University students towards non-native speakers English teachers in Hong Kong. RELC J. 38, 257–277. doi: 10.1177/0033688207085847

Clark, E., and Paran, A. (2007). The employability of non-native-speaker teachers of EFL: a UK survey. System 35, 407–430. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2007.05.002

Davies, A. (1991). The native speaker in applied linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Davies, A. (2013). Native speakers and native users: Loss and gain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dewaele, J.-M. (2018). Why the dichotomy ‘L1 versus LX user’ is better than ‘native versus non-native speaker.’. Appl. Linguis. 39, 236–240. doi: 10.1093/applin/amw055

Dewaele, J.-M., Bak, T., and Ortega, L. (2021). The mythical native speaker has mud on its face. Mouton De Gruyter. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/551192?rskey=PsjEbS&result=13 (Accessed September 30, 2024).

Esch, K. S. V., Motha, S., and Kubota, R. (2020). Race and language teaching. Lang. Teach. 53, 391–421. doi: 10.1017/S0261444820000269

Franceschi, V. (2015). Nursing students and the ELF-aware Sy llabus: exposure to non-ENL accents and repair strategies in Coursebooks for healthcare professionals. Iperstoria 5:5. doi: 10.13136/2281-4582/2015.i5.268

Gerull, K. M., Wahba, M. B., Goldin, L. M., McAllister, J., Wright, A., Cochran, A., et al. (2020). Representation of women in speaking roles at surgical conferences. Am. J. Surg. 220, 20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.09.004

Goldin, C., and Rouse, C. (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: the impact of “blind” auditions on female musicians. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 715–741. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.4.715

Hashimoto, K. (2013). “The construction of the ‘native speaker’ in Japan’s educational policies for TEFL” in Native-speakerism in Japan. Intergroup dynamics in foreign language education. eds. S. Houghton and D. J. Rivers (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 159–168.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Holliday, A. (2013). “‘Native speaker’ teachers and cultural belief” in Native-speakerism in Japan. Intergroup dynamics in foreign language education. eds. S. Houghton and D. J. Rivers (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 17–27.

Kamhi-Stein, L. D. (2016). The non-native English speaker teachers in TESOL movement. ELT J. 70, 180–189. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccv076

Kiczkowiak, M. (2019). Students’, teachers’ and recruiters’ perception of teaching effectiveness and the importance of nativeness in ELT. J. Second Lang. Teach. Res. 7:1-25–25.

Kiczkowiak, M. (2020). Recruiters’ attitudes to hiring ‘native’ and ‘non-native speaker’ teachers: an international survey. TESL-EJ 24, 1–9.

Kiczkowiak, M. (2021). Pronunciation in course books: English as a lingua Franca perspective. ELT J. 75, 55–66. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccaa068

Kiczkowiak, M. (2022). Are most ELT course book writers white ‘native speakers’? A survey of 28 general English course books for adults. Language Teaching Research. 13621688221123273. doi: 10.1177/13621688221123273

Kiczkowiak, M., and Lowe, R. J. (2021). Native-speakerism in English language teaching: ‘native speakers’ more likely to be invited as conference plenary speakers. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 45, 1408–1423. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2021.1974464

Kiczkowiak, M., and Wu, A. (2018). Discrimination and discriminatory practices against NNESTs. In: TESOL Encyclopaedia of English Language Teaching. ed. J. I. Liontas John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 45, 1408–1423.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2016). The Decolonial option in English teaching: can the subaltern act? TESOL Q. 50, 66–85. doi: 10.1002/tesq.202

Lengeling, M., and Pablo, I. M. (2012). “A critical discourse analysis of advertisements: inconsistencies of our EFL profession” in Research in English language teaching: Mexican perspectives. eds. R. Roux, A. M. Vazquez, and N. P. Guzman Trejo (Palivo: Bloomington, IN), 91–105.

Levis, J. M., Sonsaat, S., and Link, S. (2017). Students’ beliefs about native vs. non-native pronunciation teachers: professional challenges and teacher education. In A. Martinez and J. Diosde (Eds.), Native and non-native teachers in English language classrooms (pp. 205–238). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton

Li, L., Demszky, D., Bromley, P., and Jurafsky, D. (2020). Content analysis of textbooks via natural language processing: findings on gender, race, and ethnicity in Texas U.S History Textbooks. AERA Open 6:233285842094031. doi: 10.1177/2332858420940312

Lowe, R. J., and Kiczkowiak, M. (2016). Native-speakerism and the complexity of personal experience: a duoethnographic study. Cogent Educ. 3, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1264171

Mahboob, A. (2003). Status of nonnative English speakers as ESL teachers in the United States. Human. Soc. Sci. 64:2065.

Mahboob, A., and Golden, R. (2013). Looking for native speakers of English: discrimination in English language teaching job advertisements. Voices Asia J. 1, 72–81.

McCarthy, M. (2021). Fifty-five years and counting: a half-century of getting it half-right? Lang. Teach. 54, 343–354. doi: 10.1017/S0261444820000075

McGrath, I. (2013). Teaching materials and the roles of EFL/ESL teachers: practice and theory. Continuum.

Neumark, D. (2021). Age discrimination in hiring: evidence from age-blind vs. non-age-blind hiring procedures. J. Hum. Resour. 420, 420–10831R1. doi: 10.3368/jhr.0420-10831R1

Oreopoulos, P., and Dechief, D. (2012). Why do some employers prefer to interview Matthew, but not Samir? New evidence from Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver (SSRN scholarly paper ID 2018047). Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2018047

Paciorkowski, T. (2021). Native Speakerism: Discriminatory employment practices in polish language schools

Panaligan, J. H., and Curran, N. M. (2022). “We are cheaper, so they hire us”: discounted nativeness in online English teaching. J. Socioling. 26, 246–264. doi: 10.1111/josl.12543

Park, G. (2012). “I am never afraid of being recognized as an NNES”: one Teacher’s journey in claiming and embracing her nonnative-speaker identity. TESOL Q. 46, 127–151. doi: 10.1002/tesq.4

Rampton, M. B. H. (1990). Displacing the ‘native speaker’: expertise, affiliation, and inheritance. ELT J. 44, 97–101. doi: 10.1093/eltj/44.2.97

Rivers, D. J. (2016). “Employment advertisements and native-speakerism in Japanese higher education” in LETs and NESTs: Voices, views and vignettes. eds. F. Copland, S. Garton, and S. Mann (London: British Council), 68–89.

Rivers, D. J., and Ross, A. S. (2013). Idealized English teachers: the implicit influence of race in Japan. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 12, 321–339. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2013.835575

Rudolph, N. (2022). Narratives and negotiations of identity in Japan and criticality in (English) language education: (dis)connections and implications. TESOL Q. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3150

Ruecker, T., and Ives, L. (2015). White native English speakers needed: the rhetorical construction of privilege in online teacher recruitment spaces. TESOL Q. 49, 733–756. doi: 10.1002/tesq.195

Scales, J., Wennerstrom, A., Richard, D., and Wu, S. H. (2006). Language learners’ perceptions of accent. TESOL Q. 40, 715–738. doi: 10.2307/40264305

Selvi, A. F. (2010). All teachers are equal, but some teachers are more equal than others: trend analysis of job advertisements in English language teaching. Watesol NNEST Caucus Ann. Rev. 1, 155–181.

Selvi, A. F., Rudolph, N., and Yazan, B. (2022). Navigating the complexities of criticality and identity in ELT: a collaborative autoethnography. Asian Eng 24, 199–210. doi: 10.1080/13488678.2022.2056798

Si, J. (2019). An analysis of business English coursebooks from an ELF perspective. ELT J. 74, 156–165. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccz049

Van, V. T. H. (2019). The alignment between the ESP course materials and the English language used in the hotel setting in Vietnam. J. Sci. Soc. Sci. 9, 75–85. doi: 10.46223/HCMCOUJS.soci.en.9.2.263.2019

Walkinshaw, I., and Duong, O. T. H. (2012). Native- and non-native speaking English teachers in Vietnam: weighing the benefits. TESL EJ 4. doi: 10.1177/2158244014534451

Watson Todd, R., and Pojanapunya, P. (2009). Implicit attitudes towards native and non-native speaker teachers. System 37, 23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.08.002

Keywords: native speakerism, course books, non-native speaker, teaching English, native speaker

Citation: Kiczkowiak M (2024) Who gets to be an ELT course book author? Native speakerism in English for specific purposes and business English course books. Front. Educ. 9:1473353. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1473353

Received: 30 July 2024; Accepted: 24 September 2024;

Published: 09 October 2024.

Edited by:

Fan Fang, Shantou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Juan Sánchez García, Autonomous University of Nuevo León, MexicoCopyright © 2024 Kiczkowiak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marek Kiczkowiak, bWFyZWtAYWNhZGVtaWNlbmdsaXNobm93LmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.