- 1Department of Psychology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Psychological Clinical Science, University of Toronto Scarborough, Toronto, ON, Canada

Effective and efficient Wellbeing measurement is essential within the social sciences and public health. Wellbeing is described as a three-factor construct composed of Life Satisfaction, Positive Affect, and Negative Affect, yet there are few measurement models validated for the increasingly popular use of longitudinal, app-based assessment. We explored Wellbeing measurement in a postsecondary student sample, including two mechanistic indicators described in Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory: Decentering and Positive Reappraisal. Across two studies, we compared and validated popular measurement models for each construct. The most parsimonious Wellbeing model indicated only a two-factor structure comprised of positive (e.g., happiness, life satisfaction, and flourishing) and negative dimensions (e.g., anger, sadness, and anxiety). A third study revealed that a three-factor structure for Wellbeing was only supported when sampling a greater diversity of positive emotions than the earlier studies. Furthermore, while the Mindfulness-to-Meaning pathway to Wellbeing was replicated, only some operationalizations of Decentering and Reappraisal accounted for variance in Wellbeing. Concrete recommendations for the longitudinal assessment are provided. This research contributes not only to our understanding of Wellbeing, but also informs its optimal assessment in longitudinal research such as clinical trials and experience sampling studies.

Introduction

Wellbeing measurement is an important endeavor in the social sciences and public health. Measuring Wellbeing can be challenging, given its complex and multifaceted definition, spanning from basic survival needs to the realization of higher purpose in life (Maslow, 1943). Research efforts have accordingly drawn from many different domains, including subjective appraisals (Diener et al., 2018a), relationships (Demir et al., 2007; Keyes, 1998), environment (Burns, 2005; Rajani et al., 2019), fit with culture and sense of belonging (Berger-Schmitt and Noll, 2000), personal and societal values (Diener and Suh, 1997), and financial security (Netemeyer et al., 2018).

The diversity of Wellbeing domains creates a challenge for contemporary research, which increasingly focuses on ecologically valid, longitudinal assessment in the form of Wellbeing apps (Hwang et al., 2021), or more broadly in ecological momentary assessment designs that employ frequent and repeated assessments (Yin et al., 2024). In longitudinal research, conceptual breadth must be constrained by the need for efficient assessment, avoiding placing an onerous burden on participants and research resources, particularly given very high (>50%) participation attrition rates in this area (Mitchell et al., 2009; Page and Vella-Brodrick, 2013), and even greater attrition in the therapeutic app marketplace (Nwosu et al., 2022). Yet whether wellbeing can be reliably measured using a reduced set of assessment items is unknown, despite the finding that most recent smartphone-based wellness studies assessed happiness with a single question (De Vries et al., 2021).

The need for balance between comprehensiveness and practicality in Wellbeing research motivates refining existing measures to improve their validity and efficiency. However, there seems to be little agreement on the core components of Wellbeing, with no standardized measurement model and a variety of popular instruments currently in use (Upsher et al., 2022). This lack of uniform measurement limits the generalizability of studies, impeding researchers’ ability to draw firm conclusions on the efficacy of Wellbeing interventions. To improve the fidelity of measurement, Dodd et al. (2021) recommend first establishing core psychometric components of Wellbeing. Here, we describe an empirical effort to compare several popular, validated measures of self-reported Wellbeing, with the aim of developing a refined, reliable, and parsimonious measurement model.

Additionally, the issue of measurement extends to mechanistic constructs related to Wellbeing change. For example, Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (MMT; Garland et al., 2015a) has garnered empirical support as a mechanism of action explaining the benefits of mindfulness training interventions (Garland et al., 2017; Garland et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2023). MMT identifies at least two mechanistic mediators of Wellbeing enhancement: Decentering—the capacity for detachment from viewing thoughts and feelings as enduring truths—and Reappraisal—the ability to change one’s perspective or interpretation of events to promote a deeper sense of meaning and acceptance. While other factors like personality, environment, and social status (Costa and McCrae, 1980; DeNeve and Cooper, 1998; Heller et al., 2004; Watson et al., 1988) undoubtedly influence Wellbeing, our study concentrates on MMT as one avenue to improve the longitudinal assessment of Wellbeing, rather than attempting to cover all possible mechanistic explanations.

This paper therefore primarily focuses on enhancing the longitudinal assessment of Wellbeing. A secondary objective is to refine the measurement of key mechanisms, Decentering and Reappraisal, which are frequently targeted in student-focused Wellbeing interventions (Bennett et al., 2021; Pogrebtsova et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2024). To provide context for our selection of measures for investigation, we initiate with a brief review of the prevalent definitions of Wellbeing, Decentering, and Reappraisal in the research literature. Through this review, we aim to identify representative and validated measures within each domain. We then explore how the empirical analysis of these measures can contribute to the refinement of assessing Wellbeing, Decentering, and Reappraisal.

Models for wellbeing measurement: subjective wellbeing

Subjective Wellbeing, initially proposed by Diener (1984), consists of three dimensions: positive affect and negative affect, reflecting transient mood states, and life satisfaction, reflecting subjective appraisals of how ideally life is unfolding. This tripartite model has since been substantiated both by Diener et al. (2003), Emmons and Diener (1985), and Oishi et al. (2007) and independent research groups (Adler and Fagley, 2005; Campbell, 1976, 1981; Sagiv and Schwartz, 2000). The three components are not completely distinct: self-reported life satisfaction tends to be positively correlated with positive affect and negatively correlated with negative affect (Diener et al., 2009a).

Various models have been proposed to explain the common underlying construct of Subjective Wellbeing. The hierarchical structure model suggests a latent second-order Subjective Wellbeing factor that encapsulates its three lower-order components (Lawrence and Liang, 1988; Liang, 1984, 1985; Linley et al., 2009). However, the assumptions underlying this model, particularly the distinction between this higher-order factor from its three components, have not been adequately tested (Busseri and Sadava, 2011). Alternatively, Subjective Wellbeing can be viewed as a system of causally related components, with life satisfaction considered an outcome of positive and negative affect (Bradburn, 1969; Kozma et al., 1990; Schimmack et al., 2002). Given their correlated structure, it remains unclear how to most efficiently capture all three Subjective Wellbeing components over the type of brief, repeated measurements required in longitudinal, high resolution, Wellbeing research.

Models for wellbeing measurement: discrete emotions

Historically, research on the affective components of Wellbeing have focused on dimensions of positive and negative affect to indicate emotional states (Michalos, 2014; Tellegen et al., 1999; Watson and Tellegen, 1985). For example, dimensional instruments such as the PANAS (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule) are popular forms of affect assessment, scoring the two dimensions of positive and negative affect rather than specific emotions. However, this approach has been criticized as potentially failing to capture the varieties of emotional experience (Watson et al., 1988), and may therefore fail to sufficiently encapsulate feelings associated with Wellbeing (Diener et al., 2009b). Emerging research suggests that single- or two-dimensional accounts of affect may miss the complexity and richness of the emotional landscape (Chung et al., 2022), as their design primarily is focused on maximizing parsimony in measuring affect as a subcomponent of Wellbeing (Busseri and Sadava, 2011).

In contrast to generalized affect, discrete emotions are linked to distinctive triggers, expressive features, phenomenology, and action repertoires (Ekman and Davidson, 1994), helping individuals navigate their environments, survive, reproduce, and care for others (Fischer and Van Kleef, 2010; Keltner et al., 2022). As such, discrete emotions may capture complexity in Wellbeing measurement that is lost when data is reduced to two valence dimensions (Ekman, 2007). Happiness, sadness, anger, and fear are consistently included in research as prototypical emotions (Asselmann and Specht, 2023; Payne and Schimmack, 2024), although taxonomies of discrete emotions vary among researchers and increasingly include more diverse forms of positive affect (e.g., awe, gratitude) and social emotions (e.g., pride, shame) (Ortony, 2022).

Capturing the variance between discrete emotions could therefore illuminate how emotions influence behavior and decision-making, significantly impacting overall psychological Wellbeing (Diener et al., 2009b; Payne and Schimmack, 2024). Supporting this view, Chipperfield et al. (2003) reported that older adults who experienced more diverse positive emotions, such as happiness, contentment, and gratitude, had better health outcomes than those who experienced more negative emotions, such as sadness, anger, and guilt. Similarly, Tan et al. (2022) found that positive emotional granularity, or the ability to differentiate and label positive emotions with specificity, was associated with higher levels of psychological Wellbeing and resilience. Furthermore, the impact of discrete emotions on Wellbeing can vary depending on the context and individual factors. Tamir and Ford (2012) investigated the influence of emotional preferences on Wellbeing. People who valued unpleasant emotions, such as anger, as being useful in some situations tended to report greater Wellbeing than those who consistently avoided negative emotions. In this study, we explored whether incorporating discrete emotions explained unique variance in Wellbeing assessment.

Models for wellbeing measurement: life domains

To extend Wellbeing assessment beyond affect and life satisfaction, researchers have recently argued for assessment of specific domains, such as sense of purpose, health, relationships, family, work, and community (Ryff and Keyes, 1995; VanderWeele et al., 2020; Weziak-Bialowolska et al., 2022). Notably such domains are not traditionally factored into Wellbeing assessment (Diener et al., 2010; Hyde et al., 2003; Ryff, 1989; Su et al., 2014). Measuring multiple domains of Wellbeing provides a holistic picture of functioning and flourishing, identifying strengths, challenges, interactions, and trade-offs (Cummins et al., 2003).

Flourishing, which has been conceptualized as a state of high Wellbeing across these domains, can also serve as a policy target to inform interventions tailored to the needs of specific populations (VanderWeele, 2017). The Flourishing Scale (VanderWeele, 2017) was intended to extend beyond the domain coverage of the Psychological Wellbeing Scale (Ryff and Keyes, 1995), which focused on meaning, relatedness, and engagement in daily life. In this study, we explored whether incorporating the five Flourishing domains explained unique variance in Wellbeing assessment.

Mediators of wellbeing change: decentering and reappraisal

The study of Wellbeing rarely occurs in a vacuum, but rather to understand its contributing factors and potential for intervention. A second aim of this paper was to provide refined set of measures for testing the MMT in Wellbeing research, which requires measurement of its theorized mediators: Decentering and Reappraisal. Like Wellbeing, both constructs are multifaceted and can be measured using different scales. Here, we provide a brief overview of some of the most widely used measures for these constructs.

Decentering, which is the first stage of the MMT, is the process of creating psychological distance from one’s cognitive appraisals, allowing individuals to attend to mental events without becoming preoccupied with their content (Bishop et al., 2004). To integrate previous psychometric efforts, a multifaced decentering instrument was recently validated as the Metacognitive Processes of Decentering-Trait (MPoD-T) scale (Hanley et al., 2020), which captures three related constructs: meta-awareness, (dis)identification with internal experience, and (non)reactivity to internal experience. Meta-awareness refers to the ability to observe thoughts and emotions without becoming entangled, recognizing them as passing events rather than absolute truths. (Dis)identification with internal experience assesses how individuals perceive thoughts and emotions as transient mental events that do not define their core identity. (Non)reactivity to internal experience examines the tendency to non-reactively respond to thoughts and emotions, allowing observation without automatic reactions or entanglement.

Reappraisal, the second stage of the MMT, is based on the ability to acknowledge that stress-related feelings can influence Wellbeing differently, contingent on one’s subsequent appraisal of coping capabilities (McEwen, 2017). Although reappraisal has been a very popular strategy in the emotion regulation literature, it can be difficult to implement during times of distress (Ford and Troy, 2019); the MMT proposes that Decentering provides a moderating influence that allows for reappraisal by affording psychological distance from the stressor. However, unlike Decentering, no single scale comprehensively measures Reappraisal; rather, it is captured by at least three distinct scales. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross and John, 2003) Reappraisal subscale measures the individuals’ tendency to regulate emotions by cognitive Reappraisal. The Cognitive Flexibility Inventory (CFI; Dennis and Vander Wal, 2010) alternative subscale evaluates people’s capacity for recognizing multiple explanations and solutions in challenging scenarios. Lastly, the State Reappraisal Inventory (SRI; Ganor et al., 2018) assesses the use of Reappraisal by individuals immediately following an emotional event.

Research objectives and design

The exploration of Wellbeing in post-secondary students is a critical and increasingly pertinent area of study within the social sciences and public health (Davies-Cooper, 2014; Tay and Diener, 2011). This demographic frequently finds itself at a critical transition point, contending with distinctive challenges and life changes that profoundly influence their mental health and overall Wellbeing (Arnett, 2000; Conley et al., 2013). Understanding the multifaceted nature of Wellbeing in this context—ranging from basic survival needs to the realization of a higher purpose in life (Maslow, 1943; Ryan and Deci, 2001)—is essential for developing effective support systems and interventions tailored to their specific needs. Moreover, the dynamics of Wellbeing in post-secondary students encompass a spectrum of factors, including subjective appraisals, relationships, environmental influences, cultural fit, personal and societal values, and financial security (Diener et al., 2018b; Keyes, 1998).

Given the complexity of these influences and the high stakes involved in fostering healthy, resilient young adults, our study aimed to contribute to this critical field by offering a refined and reliable model for measuring Wellbeing, specifically focusing on the MMT (Garland et al., 2015a). By understanding and measuring the key constructs of Decentering and Reappraisal within this population, we seek not only to enhance academic understanding but also to inform practical strategies that can positively impact the Wellbeing of post-secondary students.

Our first research objective was to evaluate whether distinct self-report methods for measuring Wellbeing could be refined to a parsimonious set of measures. Our second objective was to refine the mechanistic mediators of Decentering and Reappraisal based on their ability to explain variation in Wellbeing, thereby clarifying the most beneficial aspects of these multifaceted constructs.

To accomplish these objectives, three empirical studies were conducted. Study 1 examined the factor structure of the targeted outcome variables through exploratory factor analysis (EFA; Spearman, 1904; Johnson and Wichern, 2007) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA; Brown, 2015) across three waves of assessments. Study 2 further tested the hypothesized optimal factor structure using CFA in a new participant sample and explored the relationships among these variables using structural equation modeling (SEM). Following unexpected findings in the first two studies, Study 3 expanded both sample size and measurement of discrete positive emotions to establish the minimum requirements for identifying the well-established three-factor structure of Wellbeing.

Transparency and openness

We pre-registered a priori study hypotheses, measures, analysis plan, sample size determination, data exclusions, and all manipulations on the Open Science Framework1 and provide open access to data and analysis scripts.2

General methods

Participants

Across all studies, participants were undergraduate students from at the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM). In Study 1 (N = 225) and Study 2 (N = 164), participants were recruited an introductory Psychology class via the online participant pool. As compensation, participants were able to obtain up to 3% course credit toward their class grades. In Study 3 (N = 552), participants were compensated with small gifts (notepads, fidget toys, or teddy bears) for attending an in-person on-campus survey station.

To self-enroll, prospective participants underwent an initial screening process using a web-based survey platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Exclusion criteria included: (i) the presence of an ongoing cognitive or mood disorder, including substance use disorders, (ii) a previous diagnosis of such a disorder within the past year, and (iii) an inability to commit to participating in the required study sessions.

The study was approved by the University Research Ethics Board (Approval Number: #41481). An a priori power analysis was also conducted using the semPower package (Moshagen and Bader, 2023) in RStudio version 1.2.5042, which indicated that N ≥ 122 participants would be needed to achieve 80% power to detect medium effect sizes relative to a null model at α = 0.05. The choice of using a medium effect size is consistent with current recommendations for meaningful effects in the field (Funder and Ozer, 2019; Gignac and Szodorai, 2016).

Given the expectation of at least 30% participant attrition over repeated measurements, the initial plan was to recruit at least 175 participants. However, with the availability of larger samples from the university participant pool and uncertainty around the true attrition rates, we elected to oversample participants to ensure sufficient power. For study 1, we recruited a total N = 225 participants. In study 2, we were unable to recruit an equivalent sample size (N = 164) but elected to proceed as a conservative replication test. Study 3 aimed to explain an unexpected Wellbeing factor structure observed in studies 1 and 2, using a larger sample (N = 552) and expanded corpus of assessment items to determine the cause of the unexpected results.

Measures

Studies 1 and 2 employed identical measures, with alterations in Study 3 described in more detail below.

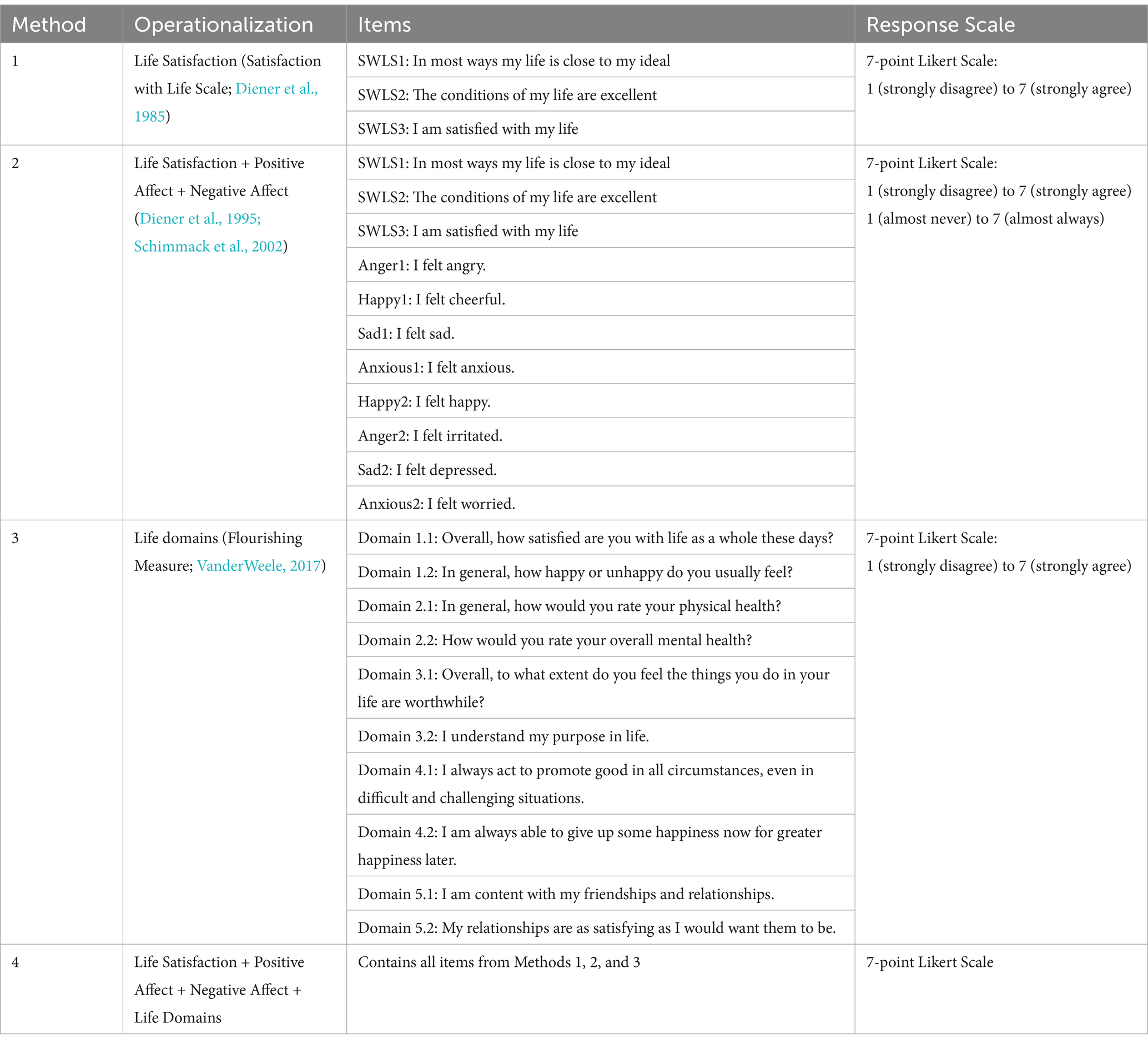

Wellbeing measurement

Wellbeing was operationalized using four different models (Table 1): exploring life satisfaction appraisal alone (method 1), appraisal combined with affect ratings (method 2), probing specific life domains (method 3), and an integrated approach that combined all ratings (method 4). Only three items from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) were used because they have been found to have superior psychometric properties than the other two items (Oishi, 2006). The SWLS, discrete emotions, and domain-specific flourishing measures have been validated in post-secondary student populations (Busseri and Newman, 2022; Davis et al., 2022; Howell and Buro, 2015; Hultell and Gustavsson, 2008; Sachs, 2003; Schimmack et al., 2002).

Decentering measurement

The Metacognitive Processes of Decentering Scale-Trait (MpoD-T; Hanley et al., 2020) was used to measure Decentering. The scale consists of 15 items that can be divided into three subcategories: meta-awareness, disidentification, and nonreactivity. We decided to use a CFA to test structural validity because prior literature has identified and integrated three subdomains of Decentering (Bernstein et al., 2015) and shown evidence for their validity. Participants rated the frequency of their experiences in the past week using a scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely) to 7 (very often or always). Higher scores on each subdomain indicate higher levels of that domain, and the total scores were calculated by summing the three domains. The MpoD-T has been validated in post-secondary student populations (De Oliveira et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023).

Reappraisal measurement

To assess Reappraisal, we explored the factor structure of 17 items drawn from the top-loading three different scales, with an aim to efficiently capture the four dimensions measured. The scales were: the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross and John, 2003) Reappraisal subscale, the Cognitive Flexibility Inventory (CFI; Dennis and Vander Wal, 2010) alternative subscale, and the State Reappraisal Inventory (SRI; Ganor et al., 2018). The ERQ includes six items that measure the tendency to regulate emotions by cognitive Reappraisal. The CFI alternative subscale includes five items that measure the ability to perceive alternative explanations and solutions to difficult situations. The SRI measures the Reappraisal goals following emotional events and contains two subscales, with three items taken from the Increase Positive and three items from Decrease Negative subscales included. Respondents answered each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” All three scales have been validated in post-secondary student populations (Ganor et al., 2018; Preece et al., 2023; Nakhostin-Khayyat et al., 2024).

Procedure

Participants self-enrolled through a research participation website (“PsychED”) administered by the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Eligibility was determined via a pre-consent screener that assessed inclusion and exclusion criteria without retaining data. Eligible participants proceeded by providing their email addresses for self-enrollment, which triggered an email containing a link to informed consent materials and the initial survey. All study materials were presented using the Qualtrics platform.

Data analysis

For all analyses, missing data were labeled as “NA” and not further manipulated.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

We used the “paran” package (Dinno, 2012) to conduct Horn’s Parallel Analysis and the “psych” package (Revelle, 2016) to conduct the EFA function. Specifically, we applied the “oblimin” rotation method to ensure that the factors are correlated when extracting multiple factors. Our loading criterion was set at ≥0.4 (Burnett and Dart, 1997) for each factor to ensure that items sufficiently loaded onto their respective factors.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

To perform CFA, we used the “lavaan” package in R (Rosseel et al., 2017). To evaluate model fit, we focused on two criteria: the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The CFI measures fit relative to a null or baseline model (Hu and Bentler, 1999), i.e., is this model “better than nothing?” Our model fit target for the CFI was >0.90, indicating acceptable model fit (Mueller and Hancock, 2008). We evaluated RMSEA to explore the potential for statistical inference, as it has a known statistical distribution that can be used for inferential statistical tests. An RMSEA <0.10 indicates an adequate fit and an RMSEA <0.05 indicates a good fit (Mueller and Hancock, 2008).

We performed model invariance tests across all assessment time points. For configural variance, all data was included in the same model, for metric invariance, loadings were constrained to be equal between time points, and for scalar invariance, both loadings and intercepts were constrained to be equal.

To address inadequate model fit during CFA, a specification search of the items was performed using the modification index (MI) for each item, which helps to identify highly correlated items that may prevent model convergence (Bryant et al., 1999). We modeled the covariance between highly similar questionnaire items (e.g., “angry” and “irritated”), to address the possibility of a “bloated” specific factor (Cattell and Tsujioka, 1964), wherein specific, homogeneous indicators cluster together and appear as their own distinct factor (Oltmanns and Widiger, 2018).

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

SEM was employed to explore the causal relationships among the key constructs (Decentering, Reappraisal, and Wellbeing), and the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (MMT) pathway of Decentering → Reappraisal → Wellbeing. To perform the SEM analysis, we utilized the “lavaan” package in R (Rosseel et al., 2017) and applied the same model fit criteria (i.e., RMSEA, and CFI) to assess the goodness-of-fit of the SEM models.

Study 1

The primary objective of Study 1 was to compare measurement approaches to identify the most parsimonious models for each of Wellbeing, Decentering, and Reappraisal. To establish the stability of these estimates across different levels of life demands, measurements were taken three times over three consecutive weeks: before midterm examinations, during examinations, and the subsequent reading week break period. Three specific aims were employed: Aim 1.1 explored novel composite measures of Reappraisal and Wellbeing involving discrete emotions, applying EFA to Assessment 1 data. Aim 1.2 aimed to validate existing measurement models using CFA for all measures.

Methods

Participants

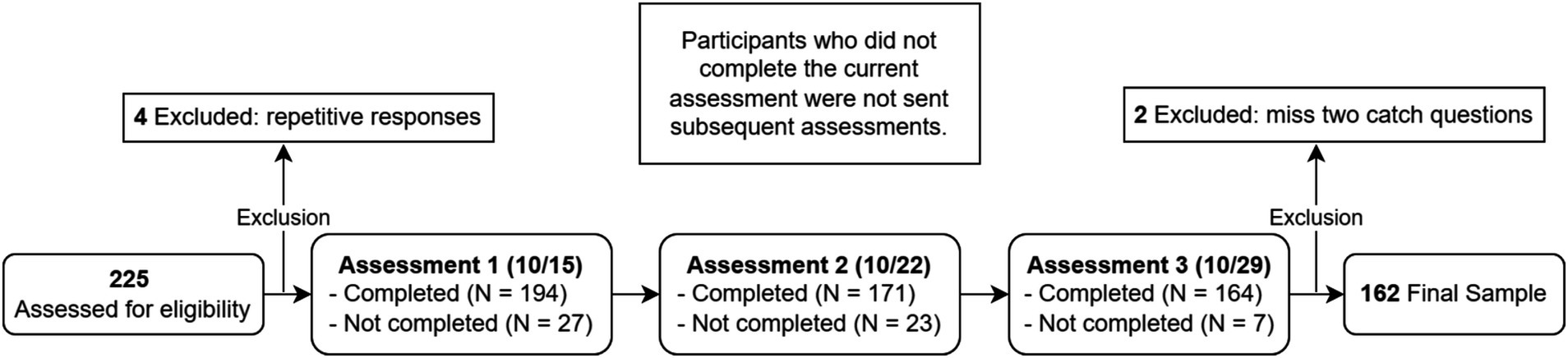

Participant flow through the study is summarized in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 1). After excluding four responses due to multiple pre-screener completions, initial participation led to 194 completing the first assessment, 171 the second, and 164 the third. Post-exclusion for failing attention checks, the attrition rate was 16.5% over 3 weeks, with the final sample size of 162 participants. The participants had a median age of 18.0 years, with an age range from 16 to 32. Among the participants, 82% identified as female and 18% identified as male. Demographic data were consistent of the ethnically diverse, Canadian university setting (30% White, 22% South Asian, 17% East Asian, 12% Middle Eastern/North African, 10% Black, 7% listed as Other, 2% Bi-racial).

Procedure

Participants self-enrolled through the research participation website (“PsychED”). Following a pre-consent screening survey, participants provided informed consent, and then completed three identical assessments spaced a week apart. Each item was rated on experiences from the past week.

Data analysis

For the first study aim, we conducted EFA on data from Assessment 1 to initially validate the proposed scales for Wellbeing and Reappraisal variables. Following the establishment of a factor structure for these variables, we conducted CFAs on the subsequent datasets from Assessments 2 and 3 to validate and refine the scales for each of the MMT constructs (Decentering, Reappraisal, and Wellbeing).

Results

Aim 1.1: exploratory analysis of new measurement models

Some candidate measures of Wellbeing had not been previously validated, including discrete emotions (Method 2), life domains (Method 4), and combined measures of reappraisal. EFA was therefore performed on Assessment 1 data before CFA was conducted on subsequent samples.

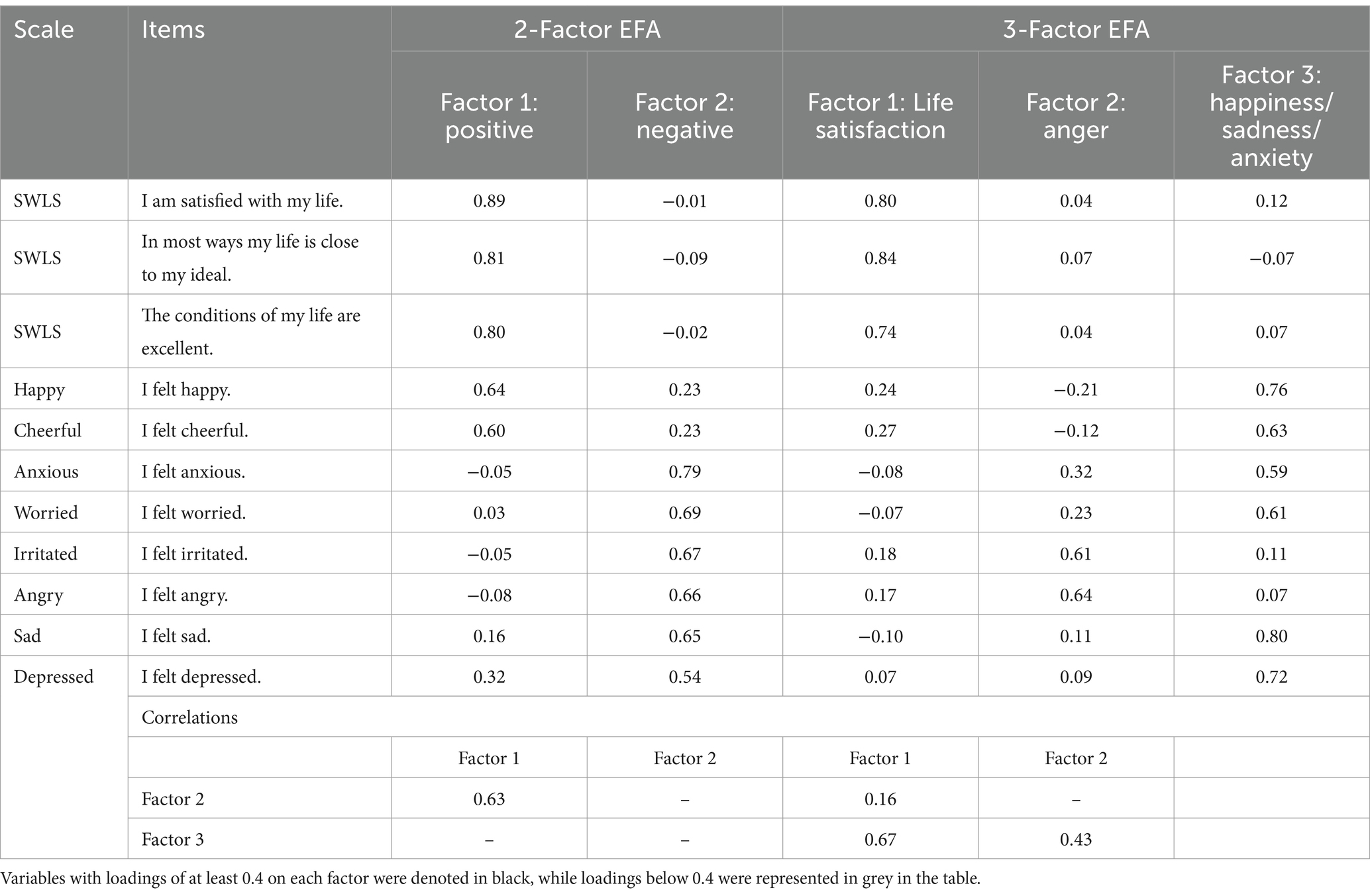

Wellbeing as life satisfaction and mood (method 2)

Contrary to the three-factor model of Wellbeing, parallel analysis indicated that only two components should be retained, as indicated by adjusted eigenvalues >1 (5.35 and 1.09, respectively). The findings from the EFA indicated that a 2-factor model adequately captured all the items related to the Wellbeing variable, with each item exhibiting a loading >0.54 (Table 2). Exploring a 3-factor structure failed to distinguish Wellbeing appraisal (SWLS) from the two valence dimensions, instead distinguishing anger from other negative affect terms (sadness and anxiety).

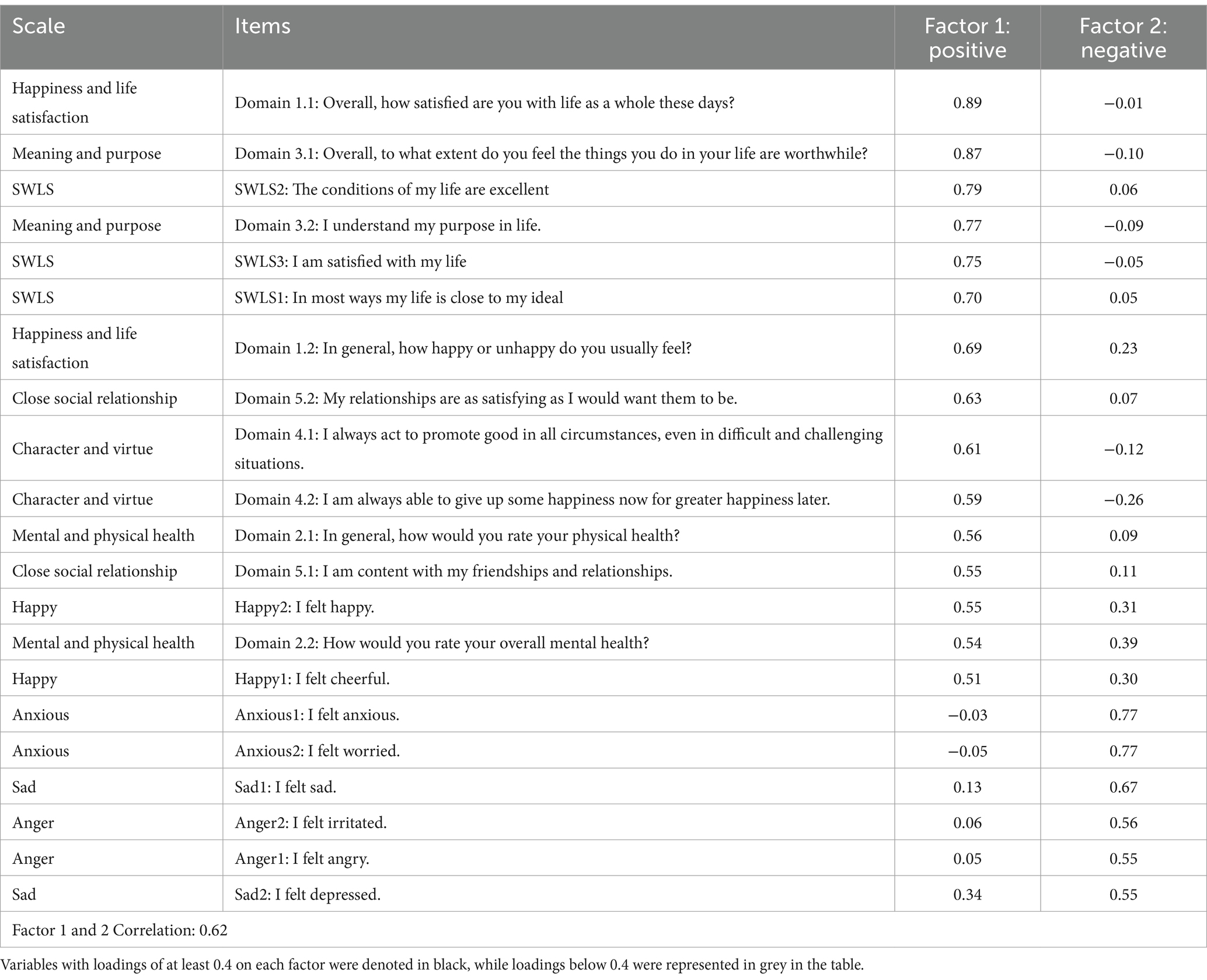

Wellbeing as life satisfaction, mood, and flourishing domains (method 4)

Parallel analysis indicated that it would be appropriate to retain only two factors based on the adjusted eigenvalues >1 (9.54 and 1.31, respectively), which accounted for 53% of the total variance. Notably, ratings of all the Flourishing questions displayed significant factor loadings on the first factor (Table 3). A three-factor structure did not support the identification of a new appraisal factor. Instead, the social relationship domain items loaded onto a distinct factor (Supplementary Table S1).

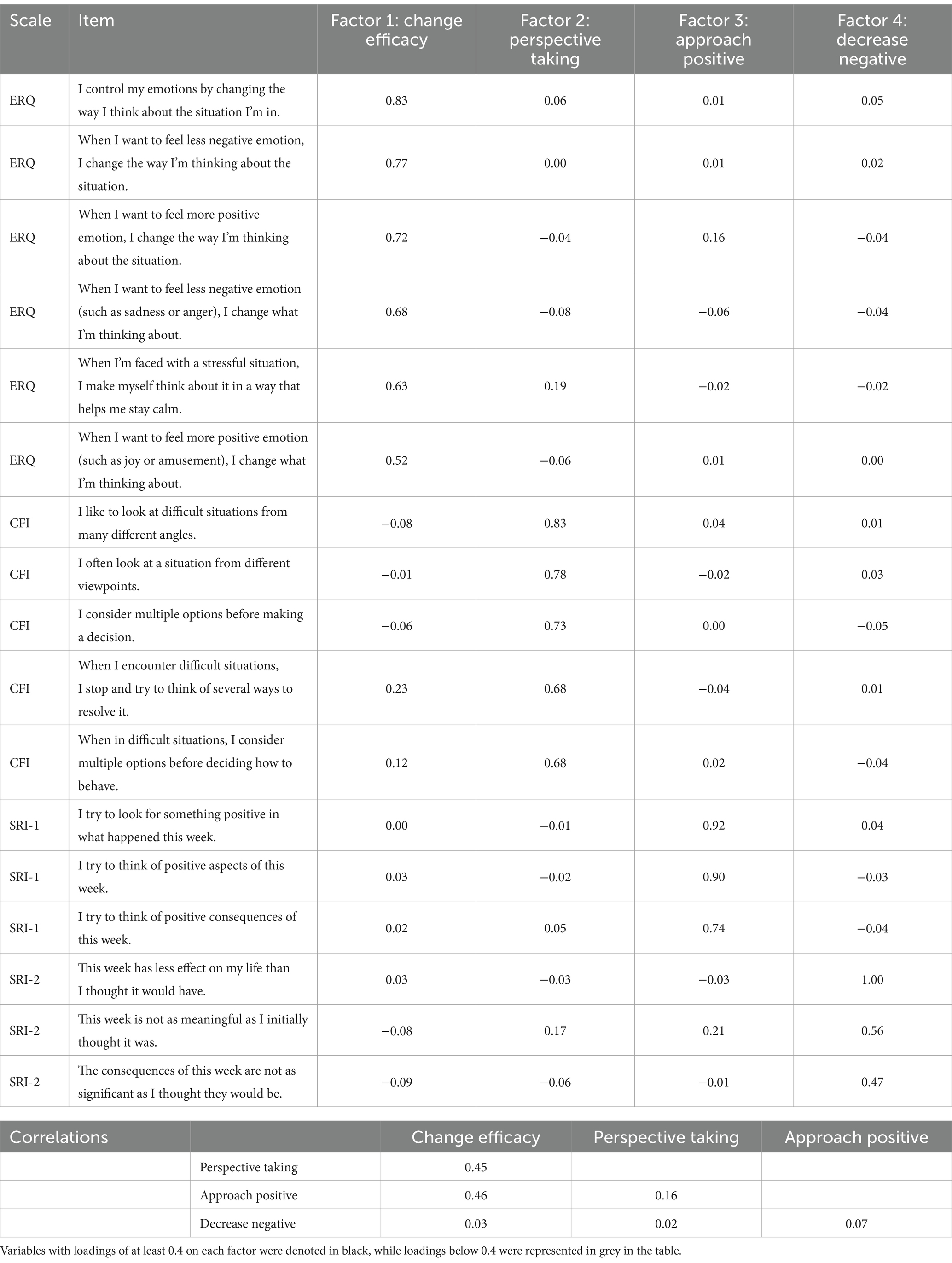

Reappraisal

Parallel analysis suggested that Reappraisal could be characterized by four underlying factors (eigenvalues of 4.99, 2.03, 1.56, and 1.19), which accounted for 59% of the total variance and included all Reappraisal items. Factor 1 consisted of all 6 items from the ERQ scale, while Factor 2 included the 5 items from the CFI scale. Factor 3 consisted of three items from the SRI-Increase Positive subscale, and Factor 4 incorporated the three items from the SRI-Decrease Negative subscale (Table 4).

Aim 1.2: replication of CFA factor structure for all measures

To preserve data independence between EFA and CFA, models described in Aim 1.1 above (Method 2, Method 4, and Reappraisal) used only the final two assessment timepoints, whereas previously validated measures (Method 1, Method 3, and Decentering) used data from all three timepoints.

Wellbeing as life satisfaction (method 1)

The CFA confirmed that all three items loaded onto a single latent variable. The results indicated a saturated model, where the observed data has 0 degrees of freedom (West et al., 2012). Across all three assessment timepoints, there were no violations of configural, metric, or scalar invariance (Supplementary Table S2).

Wellbeing as SWLS and discrete emotions (method 2)

Assessment 2 confirmed a two-factor structure (Supplementary Table S3) but indicated poor model fit (RMSEA = 0.15 [0.13, 0.17], CFI = 0.88). Examination of model indices suggested that some emotion items shared significant variance (mi = 48.32, 33.23, 26.28, and 15.24). Since pairs of emotion items were intended to measure the same emotion (e.g., anger and irritation), we additionally modeled covariance between such item pairs, which resulted in an improved model fit (RMSEA = 0.09 [0.07, 0.11], CFI = 0.96). To validate the structure of the updated model, we conducted a CFA for Assessment 3, which yielded acceptable model fit (RMSEA = 0.08 [0.06, 0.11], CFI = 0.97), with no violations of configural, metric, or scalar invariance across the three timepoints (Supplementary Table S4).

Wellbeing as flourishing domains (method 3)

For Wellbeing as Flourishing domains (Method 3), the CFA indicated that all five domains from the Flourishing questionnaire can be represented by a single latent factor (Supplementary Table S5), although the model fit was poor (RMSEA = 0.16 [0.14, 0.19], CFI = 0.84).

Examination of model indices suggested that the two items from Domain 5 shared a significant amount of variance (mi = 106.09). We allowed these residual variances to covary with each other because they were also similar in content (i.e., I am content with my friendships and relationships and My relationships are as satisfying as I would want them to be) and had similar standard deviation loadings. The updated model resulted in improved fit (RMSEA = 0.08 [0.06, 0.11], CFI = 0.96). Subsequent time points confirmed a one-factor structure, with no violations of configural, metric, or scalar invariance (Supplementary Table S6; RMSEA = 0.10[0.07, 0.12], CFI = 0.96).

Wellbeing as SWLS, emotion, and flourishing (method 4)

Assessment 2 confirmed a two-factor structure (Supplementary Table S7; RMSEA = 0.12 [0.11, 0.13], CFI = 0.84). Like the modification indices recommendations for Method 2 and Method 3, the results also suggested that items from Domain 5 (social relationship) and emotion items should be allowed to covary with each other. This updated model for Assessment 2 showed improved fit (RMSEA = 0.09 [0.08, 0.11], CFI = 0.90). The model showed configural and metric invariance across all three timepoints, but worse scalar invariance (p = 0.024) compared to the metric model, suggesting that participants intercepts shifted over time (Supplementary Table S8).

Decentering

The CFA confirmed a three-factor model (Supplementary Table S9) but a poor overall model fit (RMSEA = 0.10[0.09, 0.11], CFI = 0.86). Examination of the model indices indicated significant shared variance among items 3 and 4 (mi = 58.88; i.e. I can watch my thoughts and emotions drift by like leaves on a stream and I can watch my thoughts and emotions come and go like clouds). An updated three-factor model that allowed covariances between these items demonstrated significantly improved model fit (RMSEA = 0.08[0.07, 0.10], CFI = 0.90). With the updated model, no violation of configural, metric, or scalar invariance across the three timepoints was observed (Supplementary Table S10).

Reappraisal

The CFA confirmed a 4-factor structure for both Assessment 2 (RMSEA = 0.09 [0.07, 0.10], CFI = 0.93). Across the three timepoints, comparing configural to metric invariance led to significant chi-square change but did not change the RMSEA or CFI; further introducing scalar invariance did not change model fit (Supplementary Table S11). The violation of metric invariance appeared to be driven by small changes in covariance with Decrease Negative at Time 2, where a weak (β = −0.15) relationship with both Change Efficacy and Approach was observed but was not apparent at other timepoints. More generally, the reappraisal factors showed weak to moderate positive covariance with each other, except for Decrease Negative, which showed absent or weakly negative associations with the other factors.

Discussion

The results suggested that Wellbeing could be consistently assessed as a single-factor measure of Life Satisfaction (Method 1), but and while complex assessments supported a two-factor, positive/negative structure, no additional factors were indicated. These findings collectively support a conceptualization of Wellbeing as a construct combining both positive and negative dimensions, integrating aspects from life satisfaction, positive mood, negative mood, and flourishing domains. The three-factor structure of Decentering was replicated, while the incorporation of multiple Reappraisal measures supported four distinct factors, encompassing emotion regulation, cognitive flexibility, and positive and negative appraisals.

Support for only two factors to describe Wellbeing was consistent, even when discrete negative emotions (Model 2) and diverse flourishing indicators (Model 3), were introduced. This was surprising given that Wellbeing is consistently described via a three-factor structure that distinguishes positive affect from appraisals of life satisfaction (Diener et al., 2009a). The study, however, was not optimally designed to measure longitudinal changes in Wellbeing, as broader appraisals may require more time to develop meaningfully, although prior research has reported changes over a single university semester (Slykerman and Mitchell, 2021). This discrepancy highlights the need for further investigation into how different measurement models capture changes in Wellbeing over time.

Study 2

The main objective of Study 2 was to demonstrate the potential of the validated measures for assessing variations in student Wellbeing over time, and to assess the stability of Wellbeing’s relationship to the constructs proposed in Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (MMT). This goal was pursued across three specific aims: Aim 2.1 involved conducting CFAs on the Wellbeing, Decentering, and Reappraisal measures in an independent sample; Aim 2.2 evaluated the stability of MMT construct relationships to guide future assessments.

Methods

Participants

Participant recruitment and flow through the study were summarized in a CONSORT diagram (Figure 2). The retention rate over the three-week period was 72.91% (N = 105). The median age of participants was 18.0 years (range = 16–41) and 81% identified as female. Demographic data were consistent of the ethnically diverse, Canadian university setting (31% South Asian, 21% White, 20% East Asian, 10% listed as Other, 7% Middle Eastern/North African, 7% Black, 4% Bi-racial).

Procedures

The assessment schedule for Study 2 was modified by extending the interval between assessments from 1 to 3 weeks, to identify variance in participant wellbeing that would not be discernible within Study 1’s shorter timeframe. Students were sent assessment links via email at four timepoints: start of the semester, reading week break, midterm period, and end of the semester. Participants were instructed to rate their experiences for each item based on the past 3 weeks.

Data analysis

For each MMT construct (Decentering, Reappraisal, and Wellbeing), we conducted a CFA to validate our proposed scales for each variable. SEM was utilized to explore the MMT pathway (Decentering → Reappraisal → Wellbeing). A Latent Growth Curve Modeling approach was also used to explore changes in study variables over time, but did not ultimately contribute to the study aims (please see Supplementary materials for details).

Results

Aim 2.1: replicating the proposed factor structures

We conducted four CFAs for each of the key constructs (i.e., Decentering, Reappraisal, and Wellbeing) across the 4 timepoints. The outcomes of these analyses were consistent with our prior CFAs, providing evidence for the validity of the proposed factor structures in our sample (Tables S12-S17). For each model, there was no violations of configural, metric, or scalar invariance across the four time points, with the exception of Decentering, where introducing metric invariance led to significant changes in the χ2 but did not reduce the RMSEA (Supplementary Table S16).

Aim 2.2: exploring construct relationships within the MMT pathway

The MMT suggests a causal pathway for Wellbeing enhancement, wherein Decentering from proximal experiences fosters positive Reappraisal of life experience. We evaluated whether specific subfactors within the MMT best explain this mechanistic pathway.

MMT with wellbeing as life satisfaction (method 1)

The model delineating the relationship between Decentering and Reappraisal with Wellbeing as Life Satisfaction showed an acceptable model fit, RMSEA = 0.07[0.06, 0.07], CFI = 0.90 (Supplementary Table S18). The Decentering constructs of Disidentification and Nonreactivity were positively associated with Life Satisfaction, but unexpectedly, Meta-Awareness exhibited a negative and significant relationship with Wellbeing. Only the Approach Positive aspect of Reappraisal contributed to Wellbeing, yet according to the standardized estimates, its impact was significantly greater than that of any individual Decentering construct.

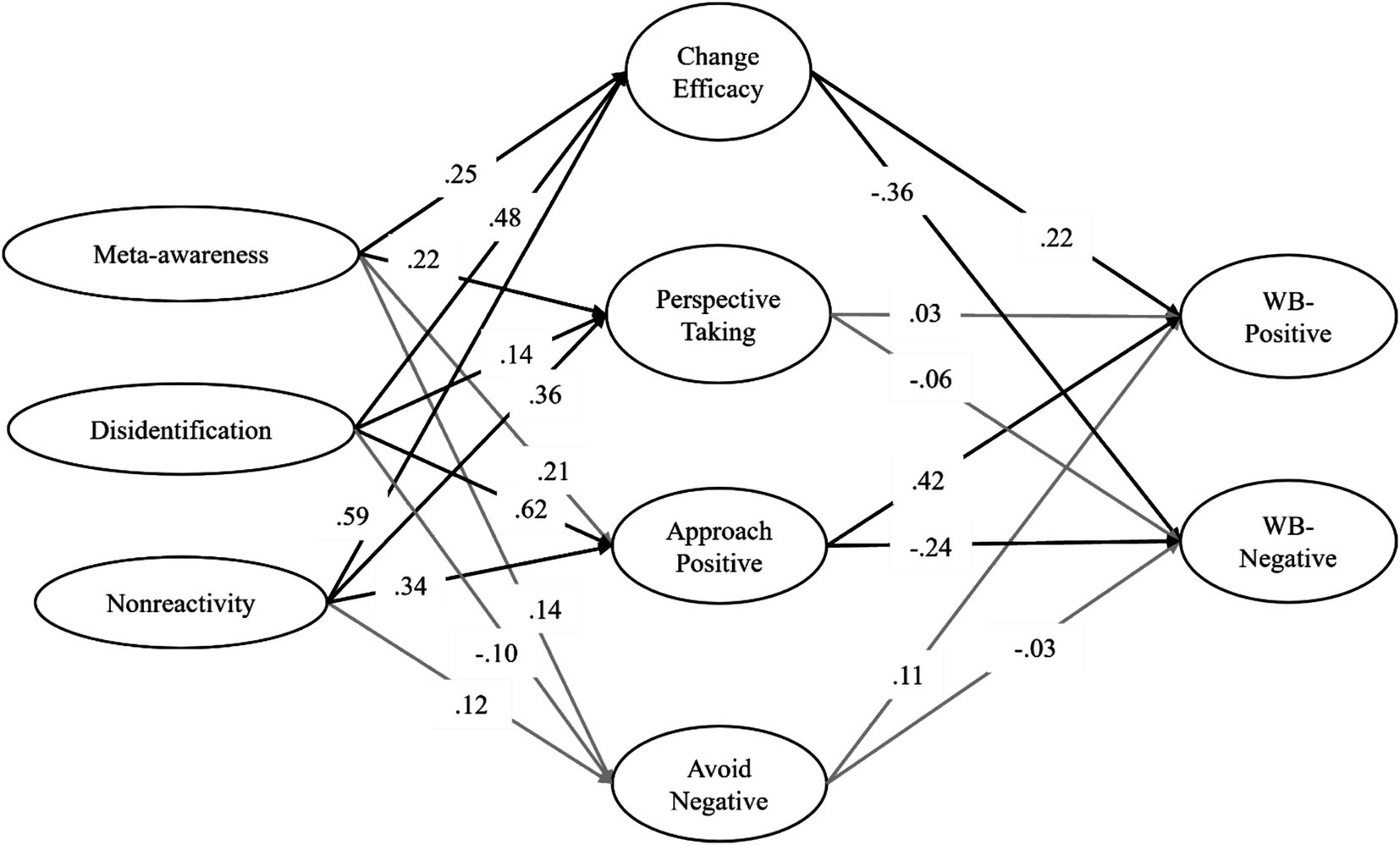

MMT with wellbeing as SWLS and discrete emotions (method 2)

Modeling Wellbeing as a combination of life satisfaction and discrete emotions revealed distinct contributions of the different MMT constructs with acceptable model fit, RMSEA = 0.06 [0.06, 0.07], CFI = 0.88. For positive Wellbeing, the Decentering constructs of Disidentification and Nonreactivity, and the Reappraisal constructs of Approach Positive and Change Efficacy were identified as positive predictors, while Meta-Awareness remained as a negative predictor. The opposite pattern emerged for negative Wellbeing, where all the mentioned patterns held except Disidentification, which was not a significant predictor (Supplementary Table S19; Figure 3).

Figure 3. This path diagram illustrates the relations among Decentering, Reappraisal, and WB (Wellbeing). Significant paths are denoted in bold, while insignificant paths are represented in gray.

MMT with wellbeing as flourishing domains (method 3)

Modeling Wellbeing in terms of flourishing domains replicated many of the contributions of the MMT construct contributions above with acceptable model fit, RMSEA = 0.07 [0.07, 0.07], CFI = 0.86 (Supplementary Table S20).

MMT with wellbeing as SWLS, discrete emotions, and flourishing (method 4)

When combining all three Wellbeing measurement approaches, the regression results were the same as in Method 2. For positive Wellbeing, the Decentering constructs of Disidentification and Nonreactivity, alongside the Reappraisal constructs of Approach Positive and Change Efficacy, consistently emerged as positive predictors, while Meta-Awareness continued to be a negative predictor. For negative Wellbeing, a contrasting pattern was observed, with the exception that Disidentification did not significantly predict outcomes (RMSEA = 0.07 [0.06, 0.07], CFI = 0.85; Supplementary Table S21).

Exploratory commonality analyses

To explore the correlations between Decentering, Reappraisal, and Wellbeing, we applied commonality analysis, which assesses the accounted variance by respective predictor variables (Nimon et al., 2008). The results were largely consistent with the SEM results, indicating that among the three Decentering factors, only Disidentification and Nonreactivity were significant in predicting the Wellbeing composite score across methods 1, 2, and 3, with minimal overlap in their contributions. Among the four Reappraisal factors, only ERQ and SRI-Increase Positive emerged as significant predictors of the Wellbeing composite score across all three methods, with low overlapping scores (Supplementary Figure S1).

Discussion

CFA was employed to examine the factor structure of constructs related to emotion regulation and Wellbeing. All models derived from Study 1 were confirmed to represent the latent factor structure for these constructs, with no violations of measurement invariance.

Significant associations along the MMT pathway were observed. All three components from the Decentering questionnaire emerged as significant predictors of Reappraisal Change Efficacy and Approach Positive. However, Decentering Disidentification did correlate with Reappraisal Perspective Taking or Decrease Negative, and Decentering Nonreactivity showed no relationship with Reappraisal Decrease Negative. In analyzing the connections between Reappraisal and Wellbeing, only Change Efficacy and Approach Positive significantly correlated with Wellbeing, while Perspective Taking and Decrease Negative did not show significant associations with either positive or negative subfactors of Wellbeing. Perspective Taking and Avoiding Negative emotion may therefore be less relevant for Wellbeing compared to Change Efficacy beliefs and the ability to Approach Positive aspects of experience. This finding is consistent with research that suggest avoidance processes generally contribute to negative information processing biases linked to depression vulnerability (Trew, 2011), and avoidance goals ironically increase negative emotion and mental health symptoms (Lench, 2011).

The Meta-Awareness subcomponent of Decentering also revealed a nuanced relationship to Wellbeing: the direct relationship suggested that higher levels of Meta-Awareness were directly associated with lower levels of Wellbeing; however, Meta-Awareness was indirectly associated with greater Wellbeing as it enhanced the Reappraisal facets of Change Efficacy and Perspective Taking. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that awareness may not by itself be a sign of adaptive emotion regulation, but awareness requires being combined with appropriate attitudes such as nonjudgment and/or positive engagement to be constructive (Rudkin et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2021).

Finally, it should be noted that slope variances were significant for Decentering but not Reappraisal factors. This aligns with prior research in which online, student-focused interventions most reliably impacted Decentering to improve Wellbeing, whereas change in Reappraisal was more difficult to achieve within a limited intervention timeframe (Wang et al., 2023).

Together, these analyses provide insights into the efficient measurement of, and relationships between, Wellbeing and the related constructs of Decentering and Reappraisal. Nonetheless, the lack of an emergent tripartite structure of Wellbeing is still concerning given the large research literature suggesting consistent identification of a tripartite model for Wellbeing. It is possible that Wellbeing factor structure is more item-dependent than expected, and that the current investigation may have overlooked some critical assessment feature that could distinguish variance in positive affect and life satisfaction.

Study 3

While studies 1 and 2 validated single and two-factor models of wellbeing, none of the models tested supported the expected three-factor structure, despite exploring diverse appraisal (Life Satisfaction/Flourishing) and negative emotion items. However, these studies only minimally sampling positive affect with the items “Happy” and “Cheerful,” and furthermore featured only modest sample sizes, both of which could have contributed to the failure to identify a three-factor model. This primary aim of Study 3 was to determine under what conditions the expected three-factor model of Wellbeing could be recovered by expanding both sample size and the number of positive affect items included in the assessment.

Methods

Participants

A total of 552 students completed a one-time assessment, with the median age being 19.0 years (age range: 16–42) and 76% identified as women. The sample was representative of the ethnically-diverse population at a research intensive major Canadian university (28% White, 17% listed as Other, 16% East Asian, 14% prefer not to answer, 13% South Asian, 6% Middle Eastern/North African, 4% Black, and 2% Bi-racial).

Measures

Study 3 expanded on previous study assessments to integrate a broader array of emotion items. Specifically, it incorporated seven terms reflecting positive emotions—joy, contentment, compassion, pride, love, amusement, and awe—and an equal number of terms for negative emotions (i.e., anger, shame, worry, sadness, jealousy, guilt, and selfishness). This comprehensive set of emotions was chosen to cover both self-referential emotions and those that are inherently social in nature. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they experienced each emotion over the past few days.

Data analysis

We conducted a CFA to validate the tripartite model of Wellbeing with the expanded item set. We also explored whether the tripartite model would be available with smaller sample sizes to rule out the possibility that it was sample size rather than assessment content that drove measurement issues in studies 1 and 2. To evaluate the effect of sample size, we randomly divided the large dataset into three equal subgroups (N = 184 each).

Results

Aim 3.1: validating the proposed wellbeing factor structures

To maintain consistency with the emotion terms used in Studies 1 and 2, our approach in Study 3 included our original assessment of basic positive and negative emotions (specifically, anger, worry, joy, and sadness), in addition to incorporating three items from the SWLS to evaluate Wellbeing structure. The results confirmed a two-factor structure (Supplementary Table S22) with acceptable model fit (RMSEA = 0.07 [0.05, 0.09], CFI = 0.97).

To then ascertain if the incorporation of a broader range of emotions would yield a more traditional three-factor structure of Wellbeing, our analysis expanded to include all seven positive and seven negative emotions within our model. With these expanded items, the two-factor model exhibited poor model fit (RMSEA = 0.11 [0.10, 0.12], CFI = 0.76), with lower factor loadings of the life satisfaction items in this model compared to others (Supplementary Table S23). However, CFA on a revised three-factor model distinguished positive emotions from life satisfaction measures and demonstrated a significant improvement in model fit (RMSEA = 0.08 [0.07, 0.09], CFI = 0.88), along with robust factor loadings for each of the three factors (Supplementary Table S24).

Dividing the dataset into three equal subgroups, replicated the results of the full sample analysis. When including all emotion terms, a consistent improvement in model fit for the three-factor structure compared to the two-factor structure was observed across all three subgroups (Supplementary Tables S25–S30).

General discussion

The present study suggested that reports of subjective Wellbeing (Wellbeing) in our sample of post-secondary are supported by a two-factor structure, representing positive and negative affect, emotions, and appraisals. Initially, analyses restricted to basic emotions (Studies 1 and 2) did not delineate a clear separation among generalized affect, discrete emotional experiences, comprehensive life satisfaction, and evaluations of specific life domains. This finding deviates from a larger literature in which subjective Wellbeing is often described via a three-factor structure that includes broader appraisals of life satisfaction (Diener, 1984), or through an additional five factors describing specific life flourishing domains (VanderWeele, 2017).

However, upon integrating a wider array of positive emotions, including social emotions, into our analysis, a distinct separation emerged between positive emotions and life satisfaction appraisals (Study 3). This nuanced finding suggests that the inclusion of a broader spectrum of positive emotions allows for the differentiation of positive emotions as a separate factor from cognitive appraisals of life satisfaction. This distinction aligns more closely with theoretical expectations and highlights the importance of considering a diverse range of emotional experiences in understanding the multifaceted nature of Wellbeing. It underscores the dynamic interplay between the breadth of positive emotional experiences and the cognitive evaluation of life satisfaction, offering a refined perspective on the structural composition of subjective Wellbeing.

The two-factor model supported here does not negate the relevance of more complex models where appraisals add depth and context to an individual’s sense of Wellbeing. Keyes’s (2002) distinction between flourishing and languishing represents the integration of affective responses across a variety of personal, social, and vocational domains. Canvassing specific domains is likely of great importance for understanding ways to enhance Wellbeing or why a person might be caught in a state of languishing. However, when conducting longitudinal assessment of Wellbeing in a post-secondary student sample, the present evidence suggests it is not essential to assess specific flourishing domains or discrete emotions; evaluations sampled from these diverse domains largely overlapped with more general probing of affect and life satisfaction.

It should be noted that our findings, based on a post-secondary student sample, might not extend to broader community or cross-cultural contexts. Our findings are reminiscent of VanDerWeele et al.’s (2020) surprising finding that financial hardship failed to show sufficient variance to be recommended as a retained flourishing domain. Focusing solely on post-secondary students could be construed as focusing on a population whose most basic life domains are largely and consistently met. Perhaps distinct flourishing factors would be supported in populations with more significant disruptions to life domains, such as clinical populations or those living under socioeconomically deprived conditions. Yet many postsecondary students face considerable uncertainty around relationships, finances, role in society, and academic performance. An alternative interpretation is therefore warranted, which suggests that in assessing Wellbeing, general questions about mood and life satisfaction are efficient and already-present integrations of functions across life domains.

From a psychometric perspective, probing these domains is not necessary to understand how a student is faring—they have already synthesized this complex analysis in a reportable and reliable manner. In assessing student Wellbeing, the onus is on the researcher to justify asking extra questions given the priority of retaining participants in any research project. We propose that the exploration of life domains be reserved for understanding mechanisms of change in Wellbeing, rather than as a routine component of Wellbeing assessment.

Refining measurement of the MMT pathway

Contrary to the appraisal of life satisfaction and discrete emotions, there exist concurrently measured mechanistic variables that are related yet distinct from the construct of Wellbeing itself. For example, the MMT pathway was developed to empirically assess the contributions of cognitive capacities such as Decentering and Reappraisal to Wellbeing (Wang et al., 2023). Once again, these measures show only modest correlations with Wellbeing, addressing concerns about the redundancy of assessing such capacities alongside Wellbeing.

Conversely, mechanistic variables should show at least some relationship to the construct they are intended to explain, and to this end, the present study was fruitful for refining the MMT pathway. Only specific aspects of Decentering and Reappraisal were consistently associated with Wellbeing. All three Decentering subfactors (Meta-Awareness, Disidentification, Nonreactivity) but only two of the four Reappraisal subfactors (Change Efficacy and Approach Positive) were found to significantly predict Wellbeing across the three measurement models. The retention of these indicators reinforces the theory that mindfulness can be beneficial by mitigating overidentification and reactivity to stress, thereby enabling individuals to perceive life events in positive and meaningful ways (Linehan et al., 2007).

Meta-Awareness emerged as the only predictor negatively related to Wellbeing, indicating that awareness alone is not enough to enhance Wellbeing. In fact, constant awareness of negative aspects could worsen Wellbeing (Kuyken et al., 2010). Being aware of negative thoughts without strategies to manage or reframe them might inadvertently increase distress and negatively affect overall Wellbeing.

Furthermore, the Reappraisal subfactors of Avoiding Negative experience and Perspective Taking were not consistently associated with Wellbeing. While adopting various perspectives or reducing negative thoughts may aid in coping with acute stressors (Bonanno and Burton, 2013), these tendencies do not necessarily reflect the effectiveness of these coping strategies on subsequent wellness.

Replicating findings from prior research (Wang et al., 2023), our analysis reaffirmed that the MMT pathway is only a partial explanation for Decentering’s benefits. Although Decentering predicted Wellbeing through its influence on Reappraisal, it also directly affected flourishing. Decentering’s direct impact on Wellbeing might be attributed to its role in reducing maladaptive behaviors like rumination and cognitive patterns associated with overidentification with experiences (Mori and Tanno, 2015). Additional unspecified mechanisms associated with a decentered state, such as physiological relaxation and a reduction of allostatic load (Rodriquez et al., 2019), warrant further exploration to better ascertain how Decentering enhances Wellbeing.

Recommendations for measurement

Based on the discussion above, we recommend the following for the longitudinal assessment of post-secondary student Wellbeing. To maintain parsimony without neglecting the tripartite factor structure of Wellbeing, we suggest using a diverse set of indicators for positive and negative emotions alongside the first three items from the Satisfaction with Life Scale, as indicated in Supplementary Table S24. This approach is particularly suited for repeated measurement contexts where extensive measurement techniques, such as ecological momentary assessment (Shiffman et al., 2008) or the daily reconstruction method (Kahneman et al., 2004), are impractical.

For longitudinal assessment of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory pathway (MMT; Decentering → Reappraisal → Wellbeing) in a student population, we propose the following recommendations. For Decentering, we recommend using the three-factor Metacognitive Processes of Decentering Scale-Trait (MPoD-T; Hanley et al., 2020). This scale showed a reliable and replicable factor structure, and use of all items are recommended when assessing direct changes from Decentering to Wellbeing, with Nonreactivity being the most significant predictor across various Wellbeing measurement methods. However, it should be noted that the Awareness factor is suggested to be a negative indicator of Wellbeing, which should be considered in scoring these subfactors- averaging Meta-Awareness items together with the other subfactors would be expected to weaken Wellbeing prediction. Meta-Awareness only positively indicated Wellbeing when its indirect path through Reappraisal was modeled. When predicting Reappraisal, only two of the three Decentering factors (i.e., Nonreactivity and Disidentification) reliably contributed to changes in Reappraisal factors (except for Factor Decrease Negative) while Meta-Awareness did not. Therefore, for examining changes in Reappraisal, we recommend that researchers focus on Nonreactivity and Disidentification factors rather than Meta-Awareness, unless research is being performed in a context where Awareness is being directed to specifically enhance positive appraisal tendencies, such as in meditation or clinical contexts (c.f., Choi et al., 2021).

For Reappraisal assessment, we recommend using two of the four factors: Change Efficacy from the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)-Reappraisal subscale (Gross and John, 2003) and the Approach Positive from the State Reappraisal Inventory (SRI)-Increase Positive subscale (Ganor et al., 2018). The ERQ Reappraisal subscale, encompassing six items, is central to evaluating confidence in employing cognitive emotion regulation strategies. This scale aligns well with the cognitive transformation process central to MMT, highlighting how individuals can cultivate efficacy in modifying their emotional experiences. In contrast, the SRI Increase Positive subscale targets the outcomes of Reappraisal in the aftermath of emotional events, focusing on the augmentation of positive emotional responses. Integrating these scales facilitates efficient assessment of cognitive strategies and their affective targets, offering a focused and empirically grounded analysis of Reappraisal’s mediating role between Decentering and Wellbeing. Other facets of reappraisal, such as Perspective Taking and Avoidance of Negative emotions, may still hold important theoretical relevance, and may be especially important in populations with elevated negative affect and symptom burden.

A further distinction emerged between the seemingly similar factors of Disidentification (Decentering), which was linked to Wellbeing, and Decrease Negative (Reappraisal), which was not. While both factors involve a form of distancing from experiences, they differ in their internal/external focus. Disidentification emphasizes an internal focus, concerning the individual’s relationship with their thoughts and emotions. It reflects an understanding of the self as distinct from transient mental states, as seen in items like “My sense of self is larger than my thoughts and feelings.” This internal distancing is indicative of a broader, more sense of self that remains constant amidst a fluctuating landscape of thoughts and emotions. Critically, this perspective is not akin to avoidance, as no relationship between Disidentification and Decrease Negative was observed. By contrast, Decrease Negative is externally oriented. It focuses on minimizing the impact of negative events, with items such as “The consequences of this week are not as significant as I thought they would be.” This suggests that the ability to disidentify with internal experiences might play a more pivotal role in enhancing Wellbeing compared to the ability to downplay the significance of external events, an important consideration in the continuing development of Wellbeing interventions.

Limitations and future directions

Range of emotions assessed

The current set of Wellbeing measures predominantly investigated a limited range of primary affective experiences, omitting emotions tied to social status or those reflecting deeper meanings and connections. For instance, incorporating a greater diversity of positive emotions related to “happy” into the assessment could potentially alter the emotion rating structure. However, when employing the type of brief repeatable measurement found in many longitudinal research and experience sampling paradigms, the distinction between emotion/mood ratings, subjective appraisals of life satisfaction, and life domains such as a meaning and relationships, were not psychometrically distinct. Future research should aim to encompass a broader spectrum of emotions, including a greater variety of positive emotions (e.g., awe, contentment), self-conscious or social emotions (e.g., embarrassment, guilt, pride, shame), and self-transcendent emotions (e.g., compassion, gratitude). These emotions are crucial indicators of introspection and self-assessment (Stellar et al., 2017; Tracy et al., 2007) and could unveil a more intricate set of Wellbeing factors, enhancing the scope of longitudinal Wellbeing assessments.

Inclusion of diverse wellbeing measures

Our study did not extend beyond momentary (sometimes referred to as hedonic) aspects Wellbeing, such as eudaimonic and social appraisals that seem to be empirically distinguishable from hedonic aspects (Joshanloo et al., 2016). This limitation may have constrained our exploration of the multifaceted nature of Wellbeing, particularly in the post-secondary context. Future studies should incorporate a diverse array of eudaimonic measures, such as the Ryff’s Personal Wellbeing Scale (Ryff, 1989), which could potentially support a more intricate factor model rather than the two-factor model described herein. This expansion would provide a more comprehensive view of students’ mental health and Wellbeing, encompassing aspects such as personal fulfillment, societal contribution, and interpersonal relationships. It is also possible that the five flourishing domain items could evoke a distinct factor structure if presented in a context emphasizing one’s sense of meaning or purpose. Finally, the potential of non-psychometric measures, including physiological and neural responses, in understanding Wellbeing more broadly also merits consideration, highlighting Wellbeing’s complexity as a construct and the necessity of a multifaceted approach in its measurement and analysis.

Generalizability of findings

The participants in our study were drawn from introductory psychology courses at the University of Toronto Mississauga. While the findings offer valuable insights into the Wellbeing of this specific group, the generalizability of the results to other contexts or populations requires careful consideration. To enhance external validity, replicating the study with a diverse participant pool from other Canadian universities, particularly those enrolled in comparable introductory psychology courses, is recommended. This replication effort would confirm whether the observed patterns are representative of broader first-year student populations across different academic environments in Canada.

Unexplored participant characteristics

Our study did not extensively explore the impact of various demographic or psychosocial factors on the results. Future research could benefit from examining how variables such as socioeconomic status, cultural background, or previous mental health history might influence Wellbeing and the effectiveness of coping strategies like Decentering and Reappraisal. Understanding these nuances could lead to more tailored and effective interventions for different student groups. We have no reason to believe that the results depend on other characteristics of the participants, materials, or context.

Concluding remarks

In summary, this research makes a significant contribution to the understanding of Wellbeing among post-secondary students, emphasizing the need for diverse emotion indicators rather than a concentration on appraisal items. Furthermore, the study affirms the mechanistic importance of Decentering and Reappraisal, with suggestions for their efficient operationalization. As both constructs are often the target of Wellbeing interventions, a better understanding of the elements most associated with Wellbeing could help tailor future interventions to address the unique challenges faced by post-secondary students. Overall, the advancement of Wellbeing assessment and intervention hinges on rigorous and efficient investigations. By applying evidence-based approaches to inform assessment in applied interventions, we can better support the mental health and Wellbeing of post-secondary students in an increasingly complex and challenging educational landscape.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (Approval number: #41481). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. NF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada - Insight Grant #435-20222-0146.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1472125/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Adler, M. G., and Fagley, N. S. (2005). Appreciation: individual differences in finding value and meaning as a unique predictor of subjective well-being. J. Pers. 73, 79–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00305.x

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Asselmann, E., and Specht, J. (2023). Changes in happiness, sadness, anxiety, and anger around romantic relationship events. Emotion 23, 986–996. doi: 10.1037/emo0001153

Bennett, M. P., Knight, R., Patel, S., So, T., Dunning, D., Barnhofer, T., et al. (2021). Decentering as a core component in the psychological treatment and prevention of youth anxiety and depression: a narrative review and insight report. Transl. Psychiatry 11:288. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01397-5

Berger-Schmitt, R., and Noll, H. H. (2000). Conceptual framework and structure of a European system of Socialindicators. San Clemente, CA: ZUMA.

Bernstein, A., Hadash, Y., Lichtash, Y., Tanay, G., Shepherd, K., and Fresco, D. M. (2015). Decentering and related constructs: a critical review and metacognitive processes model. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 599–617. doi: 10.1177/1745691615594577

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 11, 230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Bonanno, G. A., and Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: an individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Bryant, F. B., Yarnold, P. R., and Michelson, E. A. (1999). Statistical methodology: VIII. Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in emergency medicine research. Acad. Emerg. Med. 6, 54–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00096.x

Burnett, P. C., and Dart, B. C. (1997). Conventional versus confirmatory factor analysis: methods for validating the structure of existing scales. J. Res. Dev. Educ. 30, 126–131.

Burns, G. W. (2005). “Naturally happy, naturally healthy: the role of the natural environment in well-being” in The science of well-being. eds. F. A. Huppert, N. Baylis, and B. Keverne (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 404–432.

Busseri, M. A., and Newman, D. B. (2022). Happy days: resolving the structure of daily subjective well-being, between and within individuals. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Serv. 15, 80–92. doi: 10.1177/19485506221125416

Busseri, M. A., and Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 15, 290–314. doi: 10.1177/1088868310391271

Campbell, A. (1976). Subjective measures of well-being. Am. Psychol. 31, 117–124. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.31.2.117

Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-being in America: Recent patterns and trends. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Cattell, R. B., and Tsujioka, B. (1964). The importance of factor-trueness and validity, versus homogeneity and orthogonality, in test Scales1. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 24, 3–30. doi: 10.1177/001316446402400101

Chipperfield, J. G., Perry, R. P., and Weiner, B. (2003). Discrete emotions in later life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 58, P23–P34. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.1.P23

Choi, E., Farb, N., Pogrebtsova, E., Gruman, J., and Grossmann, I. (2021). What do people mean when they talk about mindfulness? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 89:102085. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102085

Chung, J. M., Harari, G. M., and Denissen, J. J. A. (2022). Investigating the within-person structure and correlates of emotional experiences in everyday life using an emotion family approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122, 1146–1189. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000419

Conley, C. S., Travers, L. V., and Bryant, F. B. (2013). Promoting psychosocial adjustment and stress Management in First-Year College Students: the benefits of engagement in a psychosocial wellness seminar. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 61, 75–86. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.754757

Costa, P. T., and McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: happy and unhappy people. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 38, 668–678. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., Van Vugt, J., and Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: the Australian Unity wellbeing index. Soc. Indic. Res. 64, 159–190. doi: 10.1023/A:1024704320683

Davis, R. C., Arce, M. A., Tobin, K. E., Palumbo, I. M., Chmielewski, M., Megreya, A. M., et al. (2022). Testing measurement invariance of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in American and Arab university students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict, 20, 874–887. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00411-z

De Oliveira, P., Juneau, C., Stinus, C., Corman, M., Michelli, N., Pellerin, N., et al. (2024). Cultivating self-transcendence through meditation practice: a test of the role of Meta-awareness,(dis) identification and non-reactivity. Psychol. Rep. 22:00332941241246469. doi: 10.1177/00332941241246469

De Vries, L. P., Baselmans, B. M., and Bartels, M. (2021). Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment of well-being: a systematic review and recommendations for future studies. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 2361–2408. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00324-7

Demir, M., Özdemir, M., and Weitekamp, L. A. (2007). Looking to happy tomorrows with friends: best and close friendships as they predict happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 8, 243–271. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9025-2

DeNeve, K. M., and Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: a meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 124, 197–229. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197

Dennis, J. P., and Vander Wal, J. S. (2010). The cognitive flexibility inventory: instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cogn. Ther. Res. 34, 241–253. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9276-4

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., and Oishi, S. (2018a). Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra. Psychology 4:115. doi: 10.1525/collabra.115

Diener, E., Oishi, S., and Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 54, 403–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056

Diener, E., Oishi, S., and Lucas, R. E. (2009a). “Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and life satisfaction” in The Oxford handbook of positive psychology. eds. S. J. Lopez and C. R. Snyder (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 186–194.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., and Tay, L. (2018b). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

Diener, E., Smith, H., and Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69, 130–141. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.130

Diener, E., and Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: economic, social, and subjective indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 40, 189–216. doi: 10.1023/A:1006859511756

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Biswas-Diener, R., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., et al. (2009b). “New measures of well-being” in Assessing Well-Being. ed. E. Diener (Cham: Springer), 247–266.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 97, 143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Dinno, A. (2012). Paran: Horn’s test of principal components/factors. R package version 1.5.1. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at:https://www.R-project.org/

Dodd, R. H., Dadaczynski, K., Okan, O., McCaffery, K. J., and Pickles, K. (2021). Psychological wellbeing and academic experience of university students in Australia during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:866. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030866

Ekman, P. (2007). Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. Thiruvananthapuram: Owl Books.

Ekman, P., and Davidson, R. J. (Eds.) (1994). The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emmons, R. A., and Diener, E. (1985). Personality correlates of subjective well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 11, 89–97. doi: 10.1177/0146167285111008

Fischer, A. H., and Van Kleef, G. A. (2010). Where have all the people gone? A Plea for including social interaction in emotion research. Emot. Rev. 2, 208–211. doi: 10.1177/1754073910361980

Ford, B. Q., and Troy, A. S. (2019). Reappraisal reconsidered: a closer look at the costs of an acclaimed emotion-regulation strategy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28, 195–203. doi: 10.1177/0963721419827526

Funder, D. C., and Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168. doi: 10.1177/2515245919847202

Ganor, T., Mor, N., and Huppert, J. D. (2018). Development and validation of a state-reappraisal inventory (SRI). Psychol. Assess. 30, 1663–1677. doi: 10.1037/pas0000621

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2015a). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds Eudaimonic meaning: a process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychol. Inq. 26, 293–314. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294